Abstract

This article tests the hypothesis that children’s learning environment will improve through a social and emotional learning (SEL) intervention that provides preschool teachers with new skills to manage children’s disruptive behavior by reporting results from the Foundations of Learning (FOL) Demonstration, a place-randomized, experimental evaluation conducted by MDRC. Research Findings: Findings demonstrate that the FOL intervention improved teachers’ ability to address children’s behavior problems and to provide a positive emotional climate in their classrooms. Importantly, the FOL intervention also improved the number of minutes of instructional time, although the quality of teachers’ instruction was not improved. Finally, FOL benefited children’s observed behavior in classrooms, with lower levels of conflictual interactions and, at the trend level, higher levels of engagement in classrooms activities, relative to similar students randomly assigned to control classrooms. Practice or Policy: This study is one of an emerging body of research on the efficacy of SEL programs for preschool children living in poverty. Understanding the value-added of these programs (e.g., in increased instructional time and increased classroom engagement) as well as their limitations (e.g., in teachers’ instructional quality and children’s academic skills) will help us design the next set of more effective interventions for low-income children.

Recent research on the early emergence of an achievement gap between economically disadvantaged preschoolers and their affluent counterparts has led many policy professionals and scholars to call for investment in academically oriented instruction prior to children’s entry into elementary school (Lee & Burkam, 2002; Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998). In addition, clear evidence from developmental science and early childhood education practice underscores the importance of environmental input (e.g., shared book reading and teachers’ introduction of phonemes) in increasing young children’s reading skills (Hindson et al., 2005; Wasik & Hindman, 2011). But is the solution to the early emerging achievement gap that preschool teachers simply need to devote more time to language and literacy instruction?

In this article, we examine an alternative hypothesis: that one rarely targeted but potentially critical barrier to increasing the amount and quality of teachers’ instruction may be teachers’ capacity to effectively manage the behavior of children in their classrooms. This study tests this premise for a sample of very low-income children attending preschools in Newark, New Jersey, a community that struggles with a host of poverty-related stressors that influence agencies and teachers as well as the children they serve. In this article, we test the hypothesis that children’s learning environment will improve through a preschool social and emotional learning (SEL) intervention that provides teachers with new skills to manage children’s disruptive behavior by reporting results from the Foundations of Learning (FOL) demonstration conducted by MDRC.

BACKGROUND

Data from national surveys show that there is an achievement gap as early as preschool between low-income children and their more affluent peers and that this gap grows over time (Lee & Burkam, 2002). Faced with these concerns, policymakers and researchers have become increasingly focused on strategies for increasing school readiness among children at risk (Bulotsky-Shearer, Wen, Faria, Hahs-Vaughn, & Korfmacher, 2012; National Education Goals Panel, 1996; Zhai, Brooks-Gunn, & Waldfogel, 2011).

Large-scale studies of early intervention models indicate that the language and preliteracy gains made in early educational programs are relatively modest at best (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2005) and that they tend to fade once the preschool year ends. One reason for this may be that, with a few exceptions, many early childhood programs provide relatively low levels of instructional support for teachers and, by extension, may generate a limited set of opportunities for children to develop language and preliteracy skills. On a related note, in a sample of preschools in half a dozen states, very low levels of instructional support were observed, with scores averaging 2 on a scale ranging from 1 to 7 (La Paro, Pianta, & Stuhlman, 2004; Pianta et al., 2005). Research on early elementary school classrooms shows considerable heterogeneity, with academic instruction taking place in as few as 8% of observed intervals in some classrooms but as many as 70% in others during a typical school day morning (LoCasale-Crouch et al., 2007; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, 2002).

Undoubtedly, there are many reasons why instructional quality in preschool classrooms may be low. Evidence from the literature on young children’s social-emotional development suggests that children’s disruptive behavior may be a root cause of lower instructional quality rather than solely a consequence of it. That is, children who have not learned to regulate their behavior in preschool are more likely to disrupt instructional time for teachers who are trying to support school readiness (Arnold, McWilliams, & Arnold, 1998). Children with problem behaviors impede their peers’ chances for academic success by distracting teachers away from instructional activities and toward managing problem behavior (Raver, 2002). Conversely, both nonexperimental and a handful of small experimental studies have yielded preliminary evidence that teachers who are able to structure emotionally positive, supportive classroom environments have students who go on to perform better over time in both academic and behavioral outcomes (Jones, Brown, & Aber, 2011; Raver et al., 2011; Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Stoolmiller, 2008).

What are the classroom and developmental mechanisms that might explain this important payoff of emotionally positive, supportive classroom environments? At the classroom level, one reason teachers may not provide high levels of instruction is that they are struggling to handle children’s emotional and behavioral problems (for a review, see Li-Grining et al., 2010; Rimm-Kaufman, La Paro, Downer, & Pianta, 2005; Webster-Stratton et al., 2008). Teachers’ management of children’s disruptive behavior is argued to play a central role in the amount of instruction teachers can provide. Previous research suggests that classroom instructional time is significantly reduced when teachers are unable to control negative child behaviors, such as teasing, name calling, and aggression (Arnold et al., 1999). In addition, high levels of teacher criticism and low levels of warmth not only compromise teachers’ capacity to provide more and higher quality instruction but also limit children’s opportunities to learn. For example, a more negative classroom climate is associated with lower levels of motivation and interest among young children (Daley, Renyard, & Sonuga-Barke, 2005). And child engagement in classroom activities is higher in classrooms in which management of behavior problems is well implemented (La Paro et al., 2004). It is important to note that children at risk for problem behavior do better academically when in classrooms that are emotionally positive and well managed compared to children in classrooms that are chaotic, disorganized, and emotionally negative (Hamre & Pianta, 2005).

Children’s behavioral difficulties may be an obstacle to their own learning. Children who are persistently sad, withdrawn, or disruptive receive less instruction, are less engaged and less positive about their role as learners, and have fewer opportunities for learning from peers (Arnold et al., 2006; Raver, Garner, & Smith-Donald, 2007). Children who become easily upset, angered, and disruptive are also likely to have greater difficulty learning and retrieving new information (Blair, Granger, & Razza, 2005; Lench & Levine, 2005; Quas, Bauer, & Boyce, 2004). In contrast, children’s positive emotions may facilitate children’s work effort and their persistence in completing academic-related tasks (Lazarus, 1991; Schutz & Davis, 2000).

In sum, the emotional climate of the classroom and children’s behavioral difficulty may be two pivotal points on which the quantity and quality of instruction and student learning may depend. Our hypothesis is that a substantial reason for the low levels of instructional time in low-income, preschool settings is that teachers are having trouble managing their classrooms and are spending too much time trying to obtain compliance from disruptive children. This study tests this hypothesis with a randomized efficacy trial of the FOL program.

OVERVIEW OF FOL

This article draws from the FOL demonstration in Newark, New Jersey, a place-randomized, experimental evaluation conducted by MDRC of an intervention designed to target children’s behavioral and emotional adjustment through the training of preschool teachers. Based on an earlier smaller efficacy trial of the same multicomponent model titled CSRP (formerly known as the Chicago School Readiness Project; Raver et al., 2008; Raver, Jones, Li-Grining, Zhai, Bub, et al., 2009; Raver, Jones, Li-Grining, Zhai, Metzger, et al., 2009), the FOL model combined teacher training in effective classroom management with weekly classroom consultation. CSRP was a smaller scale intervention with mental health consultants hired and overseen by a university-based researcher, whereas FOL was a larger scale demonstration with clinical consultants hired by a local social service organization. MDRC staff were involved in the oversight of the model, making the study something between an efficacy and effectiveness trial.

The intervention tested in FOL specifically targets the negative and coercive cycles of teacher–child interactions that have been observed in dyadic interactions with disruptive children, focusing on the proximal processes between teachers and students (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). This work builds from research on parent–child interactions, recognizing that the same issues may be at play in exchanges between teachers and children. Both adults and children can become caught in coercive cycles of negative behavior (Dishion, French, & Patterson, 1995; Patterson, 1982), with adults inadvertently exacerbating children’s aggressive behavior through harsh and ineffective limit-setting techniques. Children respond with increasingly aversive behavior, and adults, exasperated, stop their own attempts at controlling behavior, thus reinforcing the children’s negative behavior (Dishion et al., 1995). This coercive interactional pattern may result in disruptive behavior through children’s lower emotion recognition and understanding, poor affect regulation and control, and more limited repertoire of emotional and behavioral responses (Dodge, 1986; Patterson, 1982; Thompson, 1994).

A number of efficacy studies using randomized designs have demonstrated the value of addressing these coercive interactions by relying on building simple, concrete, behavioral skills of teachers and children using the Incredible Years suite of curricula (Webster-Stratton, 1998). Comprehensive training in this model provided to Head Start parents, teachers, and children over 12 weeks led to significant improvements in teachers’ use of more positive, less harsh classroom management practices; improved classroom climate; and less disruptive behavior on the part of children (with effect sizes [ESs] averaging 0.4 to 0.6). It is important to note that the intervention also yielded improvements in skills important to children’s school readiness, such as greater engagement and self-reliance (Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Hammond, 2001).

The FOL intervention pairs the professional development of the Incredible Years program with mental health consultation. Following Madison-Boyd et al. (2006) and Donohue, Falk, and Provet (2000), the consultation model includes the placement of a master’s-level clinically trained mental health consultant (referred to here as a Clinical Classroom Consultant [CCC]) with expertise in early childhood and cultural competence in each classroom to work with teachers and children for approximately 1 day per week. Consultants have two roles: (a) to provide ongoing support and coaching to teachers in using the skills learned in the training of the Incredible Years program as well as to provide stress management support to teachers and (b) to provide individualized services for the children at greatest risk. Unlike professional development that is provided as a one-shot session, professional development that is embedded in teachers’ daily practice is thought to support active learning (Garet, Porter, Desimone, Birman, & Yoon, 2001).

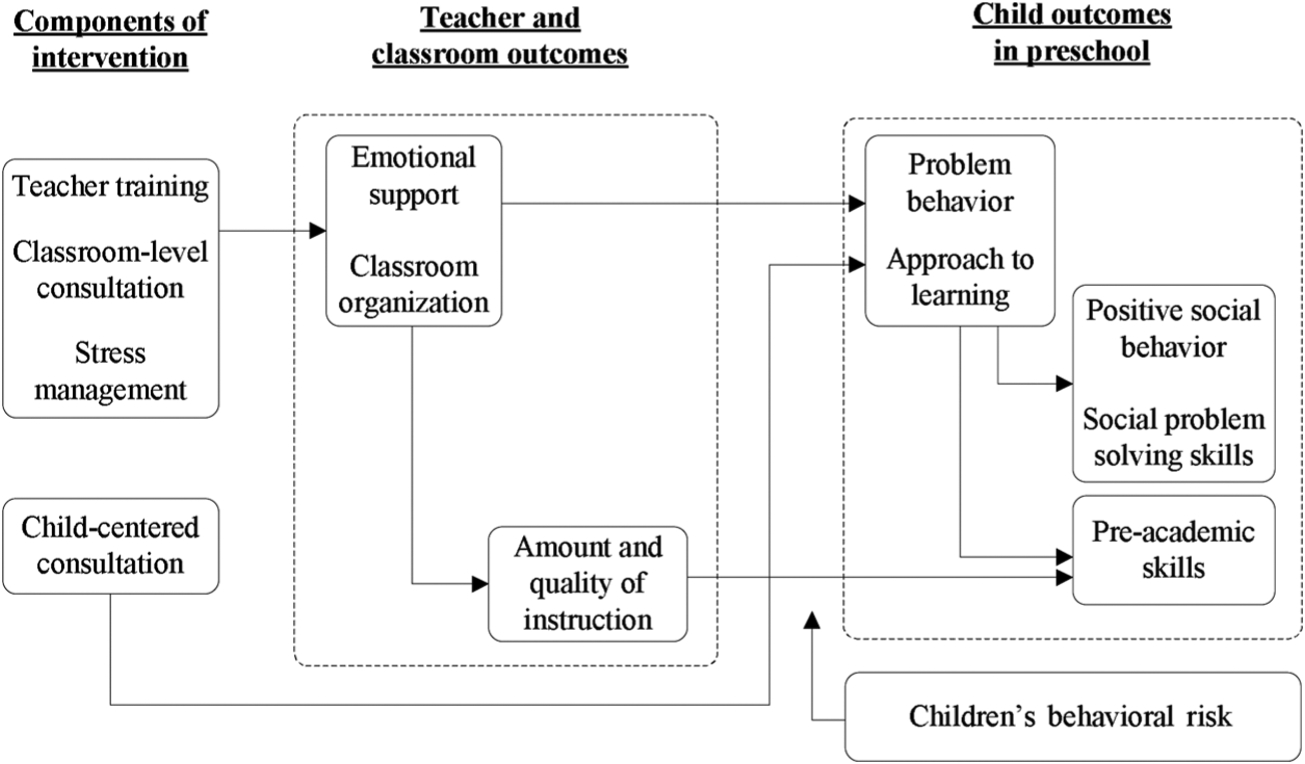

The heuristic model underlying the pathways by which the FOL intervention components are thought to affect teachers, classrooms, and children is presented in Figure 1. As shown in the figure, the primary targets of the FOL model are teachers’ emotional support and classroom organization (or management). These skills were the core components of the Incredible Years training the teachers received and were the basis of the content of CCCs’ modeling and coaching sessions with teachers. Given that stress in teachers’ personal and professional lives can reduce teachers’ effectiveness, CCCs worked with the teachers on minimizing stress through ongoing interactions as well as a formal midyear workshop on managing stress. As discussed previously, FOL was developed on the premise that managing children’s problem behavior was diverting teachers’ attention from providing instruction to children in preschool classrooms. Therefore, it was thought that changing the way in which teachers managed children’s behavior would make lesson time more productive and reduce downtime or transition time in classrooms, thus increasing the amount and quality of instruction in classrooms (as secondary outcomes to the primary classroom targets of emotional support and classroom organization). These changes in classroom-level interactions between teachers and children were expected to reduce first and foremost children’s problem behavior (acting-out and withdrawn behaviors) and increase their approach to learning (their behavior and engagement in the learning tasks of preschool), making both direct child targets of the intervention. The provision of individualized child-centered consultation provided by the CCCs was thought to benefit the children at greatest risk directly in these domains as well. Although less centrally a formal target of the intervention, there was the expectation that the program would also benefit children’s positive social behavior with teachers and peers. And finally, there was the hope that changes in children’s emotional and behavioral skills might lead to benefits to their social problem-solving skills and preacademic skills, although these were not thought to be a direct target of this SEL program.

FIGURE 1.

Heuristic model of intervention effects.

In addition, the expectation was that FOL may have a different pattern of effects for children with higher versus lower levels of behavior problems at the beginning of the year. Specifically, FOL was expected to result in stronger reductions in problematic behavior for children with high levels of behavior problems and stronger improvements in children’s approach to learning (i.e., task engagement) for children with lower levels of problems.

In short, our study was designed to test the causal effects, due to random assignment, of the multicomponent SEL model tested in FOL on (a) the classroom climate (those aspects of the classroom climate directly targeted by the training [emotional support and classroom organization] and those that were thought to occur as a result of those changes [amount and quality of instruction]) and (b) outcomes for children. Note that we did not test the mediational model implied by this thinking and Figure 1. We did this intentionally, as the data were far better suited to addressing the causal effects of the program on outcomes for classrooms and children than addressing the mediating pathway between those effects (see Gennetian, Magnuson, & Morris, 2008, for a discussion of estimating the causal effects of multiple mediators in randomized experiments).

METHODS

The study included 51 preschools that were selected from a larger number of Newark Abbott-funded preschools1 (see below). FOL operated in each of the three primary preschool venues in Newark—Head Start centers, community-based child care centers, and public schools—and was conducted in collaboration with the Newark Public Schools, Newark Preschool Council, and Family Connections (a community-based counseling and family services agency). In each preschool, one classroom with primarily 4-year-old children was selected for participation in the study to maximize the power of the analysis at the center level. In sites that had two or more preschool classrooms serving primarily 4-year-olds, directors or principals nominated a teacher/classroom for inclusion prior to random assignment.

These preschools were subject to the requirements of a series of New Jersey Supreme Court decisions known as Abbott v. Burke. These rulings required the state to increase education funding for disadvantaged districts, such as Newark. Abbott mandates included smaller class sizes (limited to 15 students), lower teacher–student ratios (two teachers per classroom), higher teacher salaries, and stricter teacher credentialing, among other features. In this context, it is important to note that the bar in Newark was set relatively high for improvements in center quality in comparison to more typical urban districts.

For the purposes of randomization, the 51 participating preschool centers were grouped first by venue and then, within venue, by child racial/ethnic composition and city ward—for a total of 12 groups of sites.2 These groups, or blocks, varied in size from two to nine centers. Random assignment was conducted within each block to ensure representation of sites across blocking characteristics in both the program group and the control group: 26 centers were randomly assigned to the FOL intervention for the 2007–2008 academic year; 25 centers were alternatively assigned to the control group, and they experienced their school year like any other preschool in Newark. In short, with this design the study was able to reliably assess the added value of FOL over and above standard practice in preschool classrooms.

All children in the 51 participating classrooms were eligible to be part of the study sample, and their parents were approached for participation in the study. Among registered children in all classrooms, 77% of parents agreed to participate in the project. The treatment classrooms had a slightly higher average consent rate (81%) compared with the control classrooms (73%). The rates differed largely because it was difficult to gather consent in two of the 25 control group classrooms. This resulted in few, if any, parental consent forms being gathered in these two classrooms. Note, however, that classroom observations and observations of individual children did not require parental consent based on the site’s agreement to participate in the demonstration, and these data were collected from all classrooms.

The Intervention

The intervention trained preschool teachers to proactively support children’s positive behavior while more effectively limiting their aggressive and disruptive behavior. The model was initially developed in the context of an earlier trial (Raver et al., 2008; Raver, Jones, Li-Grining, Zhai, Bub, et al., 2009; Raver, Jones, Li-Grining, Zhai, Metzger, et al., 2009). The intervention was composed of four components delivered across the school year:

Teacher training. Lead and assistant teachers were invited to attend five 6-hr Saturday training sessions. The workshops were adapted slightly from the Incredible Years curriculum (Webster-Stratton et al., 2001) and provided instruction on how to develop positive relationships with children; how to better manage classrooms through strategies such as setting clear rules; and how to develop children’s social skills, anger management, and problem-solving ability. Attendance at the workshops was high: 84% of lead teachers attended four to five sessions.

Classroom-level consultation. To complement the training, the intervention assigned teachers a master’s-level CCC to work with them in the classroom 1 day per week. The CCCs modeled and reinforced the content of the training sessions.

Stress management. In winter, teachers participated in a 90-min stress management workshop at their programs. A total of 94% of teachers attended this workshop. CCCs also helped support the teachers’ use of stress management skills and techniques throughout the year.

Individualized child-centered consultation. Beginning in the spring, the CCCs provided one-on-one clinical services for a small number of children who had not responded sufficiently to the teachers’ improved classroom management. By design, the individualized clinical consultation was delivered only after children had ample time to react to the new teaching strategies.

Participants

As shown in Table 1, participating teachers were, on average, about 37 years of age (SD = 9.25), and about half had taught preschool for 6 or more years at baseline. Consistent with Abbott requirements, all lead teachers had a bachelor’s degree or higher.3 The sample was predominantly female.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Teachers, Classrooms, and Students

| Adjusted meana | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Program group | Control group | Difference | SE |

| Lead teachersb | ||||

| Female (%) | 88.50 | 88.00 | 0.50 | 9.20 |

| Age (years) | 36.96 | 38.23 | −1.27 | 2.77 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||

| Black/African Americanc | 52.00 | 66.70 | −14.70 | 14.70 |

| Hispanic | 23.10 | 17.40 | 5.70 | 11.80 |

| White | 24.00 | 14.30 | 9.70 | 11.90 |

| Taught preschool for 6 or more years (%) | 53.80 | 56.50 | −2.70 | 14.50 |

| Holds bachelor’s degree or higher (%) | 96.20 | 100.00 | −3.80 | 4.10 |

| Classrooms | ||||

| Emotional support | 5.44 | 5.69 | −0.25† | −0.51 |

| Classroom organization | 4.93 | 5.07 | −0.14 | −0.23 |

| Instructional support | 3.26 | 3.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Students | ||||

| Female (%) | 48.60 | 48.00 | 0.60 | 4.00 |

| Age (years)d | 4.40 | 4.30 | 0.10† | 0.00 |

| Race/ethnicity (%)e | ||||

| Black, not Hispanic | 42.20 | 43.70 | −1.50 | 3.90 |

| White, not Hispanic | 9.50 | 9.10 | 0.40 | 2.30 |

| Hispanic | 35.80 | 34.40 | 1.50 | 4.10 |

| Other | 0.40 | 1.20 | −0.80 | 0.80 |

| Number of household government benefits received | 1.37 | 1.45 | −0.08 | 0.13 |

| 3 or more children in household (%) | 33.10 | 30.40 | 2.80 | 3.70 |

| Parent is 22 years old or younger (%) | 7.10 | 6.40 | 0.70 | 2.20 |

| Single-parent household (%) | 47.80 | 50.00 | −2.20 | 4.40 |

| Primary language spoken at home is Spanish (%) | 18.20 | 17.50 | 0.70 | 3.20 |

| Sample size (students) | 319 | 304 | ||

| Sample size (teachers/classrooms) | 26 | 25 | ||

Note. Tested using ordinary least square regression models with treatment as the key predictor, adjusting for random assignment block.

Means are adjusted for random assignment block but not for the nesting of students within one classroom.

In one instance, the assistant teacher acted as the lead teacher because of an illness of the lead teacher.

This group includes only teachers not also reporting Hispanic.

Age at the start of the school year, September 2007, calculated from date of birth.

Race/ethnicity is not available for all students.

p < .10.

The child sample was roughly split between boys and girls who averaged just over age 4 (SD = 0.37 years) at the start of the preschool year. Their racial/ethnic composition, as reported by parents, depicted the diversity of Newark’s population: more than 40% Black, nearly 10% White, and approximately 35% identifying as Hispanic. About half of the children lived in single-parent households, and about one third lived with two or more other children. On average, the children’s households were receiving more than one government benefit, such as housing assistance, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, food stamps, Medicaid, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program, or Social Security benefits.

Data Collection Procedures

Data from participating classrooms, teachers, and children were collected via a number of sources: a parent survey and teacher self-survey, a teacher survey, classroom observations, and observations of individual child behavior. A parent survey and teacher self-survey conducted at baseline provided key baseline information on families and classrooms. Surveys were completed by 92% of parents who had agreed to their child’s participation in the demonstration and 96% of all teachers. A teacher survey of about 20 min in length on child characteristics and behaviors was collected at both baseline and preschool follow-up for each child in the classroom. Completion rates for these reports were high at both time points (93% and 92% of consented children at baseline and follow-up, respectively). The baseline data were collected in mid-September 2007, so the teachers were asked to provide their initial impressions of each child following the first few weeks of school (but before being trained in the intervention model). The follow-up data were collected in the spring (April–May). If a child attended another preschool at follow-up, he or she was tracked to the new environment, and new teachers were asked to complete the spring preschool follow-up report.4 Classroom observations were collected on all classrooms at two time points, fall (September, pretraining) and spring (April–May), by observers blind to treatment group status. Observers watched classrooms for four consecutive 30-min segments (20 min of observation and 10 min of recording). Observations in treatment classrooms were scheduled on days when CCCs were not in the classrooms so that observers’ ratings remained blind and were not influenced by the presence of the CCC. Commensurate with standard practice, observations were double-coded to reduce the risk of rater drift and to ensure coder reliability (Hamre et al., 2013); in our case, 20% of these observations were double-coded for this reason. Observations of individual child behavior were collected during the preschool spring follow-up period for five preselected children in each classroom. Child observations occurred on different days and were made by different observers than the classroom observations. Selected children were stratified by gender and by teacher-reported baseline behavior (or those identified as in need of services when baseline behavior scores were missing), representing boys and girls with low, moderate, and high levels of behavior problems.5 A total of 20% of the observations were double-coded.

Measures

Baseline Measures

Teachers’ perception of their job demand was measured using a 6-item scale adapted from the Child Care Worker Job Stress Inventory (Curbow, Spratt, Ungaretti, McDonnell, & Breckler, 2000) assessing how often certain stressful situations occur in the classroom (, SD = 2.76). Classroom management skills (adapted from CSRP; Raver et al., 2008) were measured using an 8-item 5-point scale assessing teachers’ feeling of control over the classroom (, SD = 4.20). The Kessler-6 asked how often a teacher had experienced six symptoms of psychological distress in the previous 30 days on a 5-point scale (, SD = 2.13; Kessler et al., 2003). Other baseline covariates included in our analyses were child age (representing age at the beginning of the school year), child gender (male/female), and race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, White). Also, baseline Behavior Problems Index scores were collected from baseline surveys conducted with teachers and used to define subgroups of children with low and high levels of behavioral problems (see “Teacher-Reported Measures” for a description of this measure).

Measures of Classroom Climate

The Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) was used to assess the impact of FOL on classroom climate and the quality of interactions between teachers and children in the classrooms (La Paro et al., 2004; Pianta, La Paro, & Hamre, 2006). Coders were trained by the University of Virginia’s Center for Advanced Study of Teaching and Learning to achieve at least a .8 threshold of reliability on this measure. Classrooms were assessed on a 7-point Likert scale on 11 dimensions of classroom climate (positive climate, negative climate, teacher sensitivity, regard for student perspectives, behavior management, instructional learning formats, productivity, concept development, quality of feedback, language modeling, and student engagement). All ratings were calculated as average scores of independent observers across four 20-min periods of observations on a single day, beginning first thing in the morning (typically with breakfast). The interrater reliability for the CLASS in the double-coded classrooms averaged 0.89 across the two time points, ranging from 0.8 to 1.0 () in the fall and 0.8 to 1.0 in the spring (). Three composite scores were created based on prior published work on the measure: Emotional Support (consisting of the average of positive climate, negative climate, teacher sensitivity, and regard for student perspectives; , SD = 0.63), Classroom Organization (consisting of behavior management, instructional learning formats, and productivity; , SD = 0.70), and Instructional Support (consisting of concept development, quality of feedback, and language modeling; , SD = 0.90). Student engagement was considered separately.

Amount of instructional time.

CLASS observers also recorded the amount of time (in minutes and seconds) each time teachers led small- and large-group instruction (e.g., circle time or story time) during the 120-min observation period. Observers were told to begin a stopwatch at the start of any teacher-directed activity that involved at least three children and end the stopwatch when the activity was completed (, SD = 11.79).

Child-Level Measures

Teacher-reported measures.6

The Behavior Problems Index (Zill & Peterson, 1986) was used to assess children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Teachers were asked to rate each of 30 items on a 3-point scale according to how characteristic it was of the child. Based on a principal components analysis using varimax rotation (results available from the authors), we identified two factors: a 14-item Externalizing Problems subscale (α = .9) and a 14-item Internalizing Problems subscale (α = .9). The total score (collected at baseline) was utilized as a measure of behavioral risk in the subgroup analysis discussed here, whereas the subscales collected in the spring follow-up were used as outcomes in the impact analysis (, SD = 9.50).

The Attention Problems subscale of the Caregiver-Teacher Report Form (Achenbach, 1997) asked teachers to answer a series of questions about the child’s attention challenges. The 3-point scale allowed teachers to report how often behaviors occurred. The scores are presented as a sum and for this sample ranged from 0 to 18 (α = .94, SD = 4.61).

Teachers reported on the prevalence of challenging behaviors over the past month in their classroom using a set of 28 problem behaviors developed specifically for this study through consultation with the CCCs and field notes from classroom observations. Teachers reported on how often each of these behaviors (e.g., “crying in isolation,” “hitting,” and “throwing tantrums”) occurred on a 4-point scale (, SD = 0.42).

A child’s positive behavior in the classroom was measured using the Compliance With Teachers’ Directives (α = .95, , SD = 0.7) and Social Competence (α = .93, , SD = 0.69) subscales of Positive Behavior Scale (Quint, Bos, & Polit, 1997). The teacher responded on a 5-point scale for the 11-item Social Competence subscale and the 8-item Compliance With Teachers’ Directives subscale. Scores are reported as an average across items.

Teachers assessed children’s task engagement using the 16-item Work-Related Skills subscale of the Cooper-Farran Behavioral Rating Scales (D. H. Cooper & Farran, 1991). For this measure, which has been used extensively with preschool and kindergarten children, teachers were asked to report on children’s behavior during such classroom activities as “designated work time.” Showing good predictive validity for children’s later academic outcomes (McClelland, Morrison, & Holmes, 2000), the 7-point scale has descriptive phrases, which differ by item, to anchor responses to points. The scores shown for the subscale used in this report are an average, not standardized, score of items (α = .94, , SD = 1.10).

Academic skills were assessed using the 21-item Academic Rating Scale (National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.). The scale was designed to indirectly assess the process and products of children’s learning in school and is divided into three subscales representing the sum of items assessed on a 5-point scale: General Knowledge (five items; α = .93, , SD = 4.70), Language and Literacy (nine items; α = .95, , SD = 9.07), and Mathematical Knowledge (seven items; α = .96, , SD = 7.34), Teachers compared the target child with peers, reflecting the degree to which the child demonstrated skills, knowledge, and behaviors.

Observations of children.

Observations utilizing the Individualized Classroom Assessment Scoring System (inCLASS; Downer et al., 2008) tool were collected by raters blind to intervention group status. Ratings across 10 dimensions were collected during the preschool spring follow-up period for five preselected children in each classroom: Two dimensions tapped children’s conflictual interactions with teachers and peers (teacher conflict [, SD = 0.50] and peer conflict [, SD = 0.60]), five tapped children’s positive interactions with teachers and peers (teacher communication [, SD = 0.76], teacher positive engagement [, SD = 0.79], peer communication [, SD = 0.80], peer sociability [, SD = 0.78], and peer assertiveness [, SD = 0.87]), and three tapped children’s engagement with classroom activities (task engagement [, SD = 0.78], task self-reliance [, SD = 0.92], and task behavior control [, SD = 0.94]). All ratings presented here were calculated as an average score for each dimension based on four 10-min observations per child. These observations occurred mainly in the morning across a combination of activities such as circle time and individual play time. The interrater reliability for the double-coded children averaged 0.88 (range = 0.81–0.95).

Analysis Strategy

The impact of the FOL project on classroom and child outcomes was assessed using regression-adjusted means of outcomes for FOL and control classrooms and children. Controls for block assignment were included in all regression models, consistent with the way in which the classrooms were randomized. Case deletion was used for missing data on the outcome variables for which we were assessing program impact, whereas a grand mean imputation strategy was used for missing teacher and student baseline covariates (as suggested by Puma, Olsen, Bell, & Price, 2009, under conditions of missing data for whole centers).

Conducting random assignment at the center level and including only one classroom per participating center allowed us to use a single-level model for the classroom-level outcomes. The classroom-level regression included controls for baseline characteristics, including random assignment block and baseline scores on CLASS dimensions. The model was Yj = a + β0Tj+ Σk>0βkXj + ej, where Yj is the outcome for classroom j at a given time, α is the regression-adjusted mean outcome for classrooms in the control group, β0 is the impact of the intervention on the outcome, Tj represents the treatment/control assignment, Σk>0βkXi, is the sum of k classroom characteristics (including block), and ej is the random error term for classroom j.

For the child outcomes, a two-level model was utilized to account for the nesting of children within classrooms (and centers). At the classroom level, the model controlled for baseline characteristics, including random assignment block and baseline CLASS composite scores. At the child level, the model controlled for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and baseline teacher-reported behavior problems score. For teacher-reported outcomes, the following baseline characteristics were included as well: years teaching preschool and teacher perceptions of job demand, classroom management skills, and stress. The model was Yj = a + β0Tj + Σk>0βkXkij + ej + εij, where Yij represents the outcome for student i from classroom j at a given time, Tj represents the treatment/control assignment, α is the regression-adjusted mean outcome for classroom in the control group, β0 is the impact of the intervention on the outcome, Σk>0βkXkij is the sum of i child and j classroom or teacher characteristics and random assignment block, ej is the random error term for classroom j, and εij represents the random error term for student i from classroom j.

For all outcomes, the effect size was calculated as the difference between the treatment and control group means divided by the control group standard deviation, consistent with standard practice in random assignment evaluation studies (i.e., given potential effects of treatment on the standard deviation; Morris, Duncan, & Clark-Kauffman, 2005; Zaslow et al., 2010).

RESULTS

Treatment/Control Differences at Baseline

First treatment and control group differences were tested using ordinary least squares regression models with treatment as the key predictor, adjusting for random assignment block, to determine whether any statistically significant differences may have occurred by chance (see Table 1). Few if any statistically significant differences were found between classrooms, teachers, and students that were assigned to the program group and those that were assigned to the control group. Only two of the 21 contrasts approached statistical significance (p < .10): Emotional Support showed a trend-level difference between treatment- and control-assigned classrooms (with the bias for lower levels of emotional support in treatment-assigned classrooms), and child’s age showed a trend-level difference between groups.

Classroom-Level Impacts

The first question was whether teachers who were randomly assigned to receive the FOL intervention would be better able to structure emotionally positive, behaviorally well-managed classroom environments than teachers who were randomly assigned to the control group. The results are shown in Table 2. The FOL program group classrooms were rated better than the control group classrooms on a measure of Emotional Support (at a trend level of significance; p < .10) and on Classroom Organization (at p < .05), with ESs of .65 and .75, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Program Impacts on Observed Ratings of Classroom Climate and Instructional Time

| Adjusted meana | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Program group | Control group | Difference | SE | Effect sizeb |

| Emotional Supportc | 5.70 | 5.24 | 0.47† | 0.26 | 0.65 |

| Positive climate | 5.61 | 5.03 | 0.58 | 0.36 | 0.60 |

| Negative climate | 1.12 | 1.75 | −0.64** | 0.20 | −0.90 |

| Teacher sensitivity | 5.18 | 4.78 | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.46 |

| Regard for student perspectives | 5.13 | 4.89 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.28 |

| Classroom Organization | 5.00 | 4.36 | 0.64* | 0.27 | 0.75 |

| Behavior management | 5.42 | 4.66 | 0.76* | 0.35 | 0.72 |

| Productivity | 5.43 | 4.90 | 0.53† | 0.26 | 0.63 |

| Instructional learning formats | 4.16 | 3.54 | 0.62† | 0.35 | 0.61 |

| Instructional Support | 3.42 | 2.94 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.53 |

| Quality of feedback | 3.47 | 3.02 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.44 |

| Language modeling | 4.27 | 3.61 | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.54 |

| Concept development | 2.51 | 2.18 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.44 |

| Amount of instructional time (min) | 35.60 | 25.10 | 10.60* | 4.40 | 0.96 |

| Sample size | 26 | 25 | |||

The table presents adjusted means that control for random assignment blocks and baseline Classroom Assessment Scoring System dimension scores.

Negative climate is reverse-coded for the composite score.

The effect size was calculated as the difference between the treatment and control group means divided by the control group standard deviation.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

To better understand these findings, we examined effects on the separate dimensions of the CLASS that made up the composite measures. The dimension of Emotional Support that showed the strongest impact was observers’ ratings of negative climate (p < .01), with an ES of −.90. All of the dimensions of Classroom Organization showed improvements, with statistically significant positive impacts on behavior management (p < .05) and those on productivity and instructional learning formats at a trend level of significance (p < .10). Additional analyses (not shown) indicated that the program group level of classroom organization stayed relatively flat from fall to spring, while the control group level declined over this same period, indicating that FOL was primarily effective at helping teachers maintain their classroom organization over the course of the year rather than substantially increase it.

The second question was whether these changes would lead to more productive lesson time and less downtime in classrooms. This could increase the amount and quality of instruction in classrooms. Table 2 shows no differences on observations of Instructional Support or any of the individual dimensions of this CLASS domain. However, in addition to making these standardized ratings of quality, observers also assessed the amount of time that teachers actually spent in leading small- and large-group instruction during a 120-min observation period. Consistent with the higher ratings for teachers’ classroom organization, instructional time was significantly higher in the FOL classrooms, by an average of 10 min (p < .05, ES = .96).

Impacts on Outcomes for Children

Observations of Children’s Behavior

We then assessed whether FOL had an impact on the behavior of the preschool children based on the in CLASS measures (see Table 3). Ratings of problem behavior were in the low range for all classrooms—with scores, on average, just above 1. Yet even with these overall low ratings, FOL intervention classrooms were observed to have statistically lower levels of child–peer and child–teacher conflict on average (which reflects differing interactions of children with those around them). For example, ratings on conflict with teachers were nearly 1.5 in control group classrooms, whereas FOL classrooms had ratings about a quarter point lower (p < .01, ES = .40). Effects on conflict with peers were similar and approached significance (p < .10, ES = .27). By contrast, no differences were found between program and control classrooms on ratings of children’s sociability with peers and positive engagement with teachers.

TABLE 3.

Program Impacts on Observed Ratings of Child Behavior

| Adjusted meana | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Program group | Control group | Difference | SE | Effect sizeb |

| Observed rating of child behaviorc | |||||

| Problem behavior | |||||

| Teacher conflict | 1.25 | 1.46 | −0.22** | 0.07 | −0.40 |

| Peer conflict | 1.40 | 1.57 | −0.18† | 0.09 | −0.27 |

| Positive social behavior | |||||

| Teacher communication | 2.20 | 2.36 | −0.16 | 0.12 | −0.20 |

| Teacher positive engagement | 3.21 | 3.42 | −0.21 | 0.16 | −0.27 |

| Peer communication | 2.46 | 2.57 | −0.11 | 0.16 | −0.14 |

| Peer sociability | 3.44 | 3.53 | −0.09 | 0.15 | −0.11 |

| Peer assertiveness | 2.08 | 2.27 | −0.19 | 0.17 | −0.21 |

| Approach to learning | |||||

| Task engagement | 4.87 | 4.62 | 0.25† | 0.14 | 0.31 |

| Task self-reliance | 3.08 | 3.14 | −0.06 | 0.20 | −0.07 |

| Task behavior control | 5.40 | 5.08 | 0.32† | 0.19 | 0.34 |

| Overall classroom student engagement | 5.75 | 5.19 | 0.55† | 0.28 | 0.60 |

| Teacher-reported child outcomes | |||||

| Problem behavior | |||||

| BPI internalizing | 2.66 | 2.30 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 0.11 |

| BPI externalizing | 4.12 | 3.70 | 0.43 | 0.68 | 0.08 |

| C-TRF attention problems | 3.58 | 3.47 | 0.11 | 0.64 | 0.02 |

| Prevalence of challenging behaviors | 1.90 | 2.29 | −0.39* | 0.17 | −0.92 |

| Positive social behavior | |||||

| PBS compliance | 4.03 | 3.97 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| PBS competence | 4.04 | 4.00 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.06 |

| Approach to learning | |||||

| CFBRS work-related skills | 4.84 | 4.76 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| Preacademic skills | |||||

| ARS language and literacy skills | 35.07 | 32.61 | 2.46 | 1.71 | 0.27 |

| ARS math knowledge | 25.77 | 25.40 | 0.37 | 1.68 | 0.05 |

| ARS general knowledge | 19.72 | 18.46 | 1.25 | 0.95 | 0.28 |

| Sample size (students) | 283 | 248 | |||

| Sample size (classrooms) | 26 | 23 | |||

Note. BPI = Behavior Problems Index; C-TRF = Caregiver-Teacher Report Form; PBS = Positive Behavior Scale; CFBRS = Cooper-Farran Behavioral Rating Scales; ARS = Academic Rating Scale.

Regression-adjusted means control for random assignment status and blocking, baseline Classroom Assessment Scoring System measures, and baseline child characteristics.

The observed child outcomes were drawn from a subsample. The program group had 130 children in 26 classrooms, and the control group had 121 children in 25 classrooms.

The effect size was calculated as the difference between the treatment and control group means divided by the control group standard deviation.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

As shown at the bottom of the first half of Table 3, children in FOL classrooms were rated higher on measures of their approach to learning than children in control classrooms, with differences between children in FOL and children in control classrooms approaching significance. Children in FOL classrooms were scored about a quarter of a point higher both on their engagement in activities and on their ability to control their behavior during those activities (p < .10, ES = .3). Moreover, trend-level differences were observed in the overall classroom level of engagement observed by the CLASS coders on a different day, as well, indicating a higher level of focus and participation among all children during classroom activities (p < .10, ES = .6).

Teacher Reports

In addition to having independent observers rate children’s behavior, we also asked teachers to report on children’s behaviors and preacademic skills (see Table 3). Despite differences in observed ratings of children’s behavior reported by blind observers, teachers did not report differences in children’s behavior between the program and control groups. Whether we examined behavioral outcomes or approach to learning, no statistically significant differences emerged between the two groups of classrooms. There was one exception: When teachers rated the prevalence of challenging behaviors across all children in their classrooms, there was a statistically significant difference between FOL and control classrooms, with scores of 2.3 in the control classrooms compared with 1.9 in the program classrooms (p < .05, ES = .92).

Sensitivity Analyses

In comparing impacts on child outcomes from the two data sources (teacher reports and observations), one concern was that the divergent findings may be due to the fact that the independent observations were collected on a subset of children in each classroom whether or not parental consent was gathered, whereas teacher-reported data were collected on children whose parents consented to their participation in the demonstration. This was especially problematic given differences across treatment groups in response rates. Therefore, additional analyses were conducted to confirm whether these differences in impacts were due to the different samples or whether they reflected differences in findings across sources (results available from the authors). Results strongly paralleled those in Table 3, indicating that the findings were not due to differences in the samples of children who were assessed by the two types of reporters.

Subgroup Analyses

To address our final question, we examined impacts separately for groups of children defined by their baseline levels of problem behaviors (using a median split of baseline teacher-reported total Behavior Problems Index scores).7 Differences in subgroup impacts were tested by conducting split sample regression analyses (that allow for heterogeneity of the effect of the covariates across subgroups) and estimating differences using an HT statistic (i.e., the weighted sum of squares of the impact estimates for the subgroups with a chi-square distribution; H. M. Cooper & Hedges, 1994; Greenberg, Meyer, & Wiseman, 1993; see Table 4).8 As shown in the far right column, labeled “H Stars,” no statistically significant differences between subgroups were found. That said, one finding is worth noting: The FOL intervention decreased the observed conflict for higher risk children, although there were no differences between program and control group children for the lower risk subgroup. No differences emerged for this subgroup for other observed or teacher-reported outcomes, however, including observations of children’s approach to learning.

TABLE 4.

Program Impacts on Observed and Teacher Ratings of Child Outcomes, by Level of Behavior Problems

| Low | High | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted mean | Adjusted mean | ||||||||||

| Outcome | Program group | Control group | Difference | SE | Effect size | Program group | Control group | Difference | SE | Effect sizea | H stars |

| Observationsb | |||||||||||

| Problem behavior | |||||||||||

| Teacher conflict | 1.31 | 1.29 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 1.36 | 1.55 | −0.19 | 0.12 | −0.40 | |

| Peer conflict | 1.45 | 1.50 | −0.05 | 0.19 | −0.06 | 1.47 | 1.77 | −0.31* | 0.13 | −0.51 | |

| Positive social behavior | |||||||||||

| Teacher communication | 2.08 | 2.48 | −0.40† | 0.21 | −0.47 | 2.30 | 2.30 | 0.00 | 0.17 | −0.01 | |

| Teacher positive engagement | 3.08 | 3.47 | −0.39 | 0.25 | −0.46 | 3.21 | 3.31 | −0.10 | 0.25 | −0.13 | |

| Peer communication | 2.59 | 2.64 | −0.04 | 0.27 | −0.05 | 2.47 | 2.60 | −0.13 | 0.18 | −0.18 | |

| Peer sociability | 3.49 | 3.68 | −0.19 | 0.24 | −0.24 | 3.43 | 3.60 | −0.16 | 0.18 | −0.23 | |

| Peer assertiveness | 2.03 | 2.33 | −0.30 | 0.38 | −0.29 | 2.15 | 2.23 | −0.08 | 0.19 | −0.09 | |

| Approach to learning | |||||||||||

| Task engagement | 4.91 | 4.76 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 4.80 | 4.61 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.27 | |

| Task self-reliance | 2.95 | 3.05 | −0.11 | 0.39 | −0.09 | 3.11 | 3.19 | −0.08 | 0.25 | −0.08 | |

| Task behavior control | 5.58 | 5.24 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 5.12 | 4.81 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.35 | |

| Teacher reportsc | |||||||||||

| Problem behavior | |||||||||||

| BPI internalizing | 1.55 | 1.15 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.18 | 4.04 | 2.63 | 1.42 | 1.07 | 0.39 | |

| BPI externalizing | 1.68 | 1.70 | −0.02 | 0.56 | −0.01 | 6.93 | 5.24 | 1.69 | 1.27 | 0.28 | |

| C-TRF attention problems | 1.97 | 1.49 | 0.48 | 0.58 | 0.14 | 5.46 | 4.70 | 0.76 | 1.24 | 0.15 | |

| Positive social behavior | |||||||||||

| PBS competence | 4.28 | 4.22 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 3.75 | 3.79 | −0.04 | 0.13 | −0.06 | |

| PBS compliance | 4.38 | 4.16 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 3.69 | 3.72 | −0.03 | 0.15 | −0.04 | |

| Approach to learning | |||||||||||

| CFBRS work-related skills | 5.10 | 5.18 | −0.09 | 0.19 | −0.09 | 4.48 | 4.57 | −0.09 | 0.17 | −0.08 | |

| Preacademic skills | |||||||||||

| ARS language and literacy skills | 36.14 | 34.91 | 1.22 | 1.71 | 0.13 | 32.78 | 32.50 | 0.28 | 1.98 | 0.03 | |

| ARS math knowledge | 26.67 | 27.31 | −0.64 | 1.82 | −0.08 | 23.80 | 25.33 | −1.52 | 1.85 | −0.21 | |

| Sample size (observations of students)d | 50 | 40 | 58 | 38 | |||||||

| Sample size (teacher reports on students)d | 125 | 94 | 128 | 100 | |||||||

| Sample size (classrooms)e | 26 | 25 | 26 | 25 | |||||||

Note. Subgroups were created by calculating a median split of baseline teacher-reported BPI scores across the entire sample. BPI scores higher than 7 fell into the “high” category. Regression-adjusted means control for random assignment status and blocking, baseline Classroom Assessment Scoring System measures, and baseline child characteristics. BPI = Behavior Problems Index; C-TRF = Caregiver-Teacher Report Form; PBS = Positive Behavior Scale; CFBRS = Cooper-Farran Behavioral Rating Scales; ARS = Academic Rating Scale.

The effect size was calculated as the difference between the treatment and control group means divided by the control group standard deviation.

For each dimension, observers rated children on a scale from 1 to 7, with 1 representing low and 7 representing high. All observations used the Individualized Classroom Assessment Scoring System measure.

Teacher-reported outcomes control for students’ baseline scores on a given measure, when available.

Baseline BPI scores were not available for all children.

For teacher-reported outcomes, the sample size is 23 for the control group classrooms.

p < .10.

p < .05.

DISCUSSION

Preschool has garnered increasing policy attention as a means of closing the achievement gap between socioeconomically disadvantaged children and their affluent counterparts. Yet programs may not be able to make much of a difference in young children’s school readiness if they do not provide ample learning opportunities that are emotionally positive, well structured, and engaging. Accordingly, our first question was whether a comprehensive SEL intervention led to measurable and substantial improvement in classroom instruction on dimensions of classroom climate and teachers’ management of children’s challenging behaviors.

The FOL intervention improved teachers’ ability to address children’s behavior and to provide a positive emotional climate in the classroom and, especially, increased teachers’ ability to manage their classrooms. Teachers in the program group showed significantly better skills in managing children’s behavior problems and in providing an emotionally positive and supportive classroom climate than did their counterparts in the control group. That is, program group teachers used less sarcasm and anger and showed a greater ability to manage children’s behavior in the classroom. Effect sizes on classroom processes were sizeable (.65 and .75 for Emotional Support and Classroom Organization, respectively). In short, the first hurdle for the intervention was cleared—showing benefits in those aspects of classroom management in which teachers were trained during the training sessions and on which the coaches were explicitly supporting teachers.

To put these CLASS effects in perspective, it is helpful to consider new findings on the points on the 1-to-7 continuum at which classroom quality is associated with improved outcomes for young children. The question is whether an improvement in the 5-to-6 range on the scale might matter in terms of classroom quality and outcomes for children. Fortunately, research studies have found that it does indeed make a difference (in terms of associations with both social-emotional and academic outcomes for children) whether classrooms score a 5, a 6, or a 7 (Burchinal, Vandergrift, Pianta, & Mashburn, 2010). Thus, raising the level of classroom quality at this range of the scale may indeed be important for outcomes for children.

Our next question was whether improvements in emotional climate were paralleled by an increase in teachers’ ability to provide more instruction. Simply put, a new curriculum implemented in preschool classrooms may have less value if it does not translate into teachers increasing the amount of class time spent on cognitively demanding and enriching activities and lessons. Regarding this question, the FOL intervention also improved the number of minutes of instructional time. In a 120-min observation period, an average of 35 min was spent in teacher-led instruction in FOL classrooms, compared with 25 min in control group classrooms. If such gains were representative of gains achieved every weekday, this would translate to 50 min more instruction a week, or a week’s more instruction over a school year. This may be a result of fewer disruptions by children during large-group activities and a reduction in the amount of transition downtime between activities, although this was not explicitly tested in these analyses. When teachers focus proactively on managing their students’ more challenging behaviors more effectively, opportunities for learning (as indicated by instructional time) may be increased.

A major issue in the quality debate has been the recognition that there is a great deal of time lost in preschool classrooms to tedious, off-task activities, such as getting children organized to complete small- and large-group projects, getting children to line up, and so on (Early et al., 2010; Pianta et al., 2005). These findings of an increase in the number of minutes spent in teacher-led instruction suggest that there are clear, concrete steps that centers can take to address this facet of classroom quality.

Although these findings are promising, it is important to highlight that FOL is not a panacea: FOL improved the amount of classroom instructional time, but it did not otherwise increase or decrease the quality of instruction children received. One might argue that it is unlikely that a program like FOL would enable teachers to engage in higher quality language interactions with children, given that teachers’ language complexity was not directly targeted or discussed in teacher trainings, consultations, and the like. However, it is possible that focusing on emotional and behavioral adjustment could potentially have interfered with instructional support for children (which would have resulted in reductions in the quality of instruction in FOL classrooms). Our analyses suggest that neither of these scenarios appears to be true.

Finally, FOL benefited children’s interactions with teachers and peers relative to those of similar students randomly assigned to the control group. Specifically, our results suggest that children in FOL classrooms scored lower on conflictual interactions with both teachers and peers based on observations by trained coders. Moreover, there was some suggestion, at the trend level, of higher levels of self-control, greater levels of focus, and higher levels of participation in classroom activities for children in FOL classrooms. Teachers’ reports did not reflect these same observed differences when looking at individual children, although treatment teachers did rate the prevalence of challenging behaviors across the classroom as significantly lower than those teachers in control group classrooms did.

The lack of findings on the teacher-reported outcomes is somewhat surprising, in that other studies of social-emotional enhancements in preschool have shown that successful interventions typically change teachers’ perceptions as well as observed aspects of behavior. One hypothesis is that the training that teachers in FOL received primed them more to see challenging behaviors, even as it increased their capacity to effectively manage these behaviors when they occurred. The fact that teachers did report that their classrooms as a whole were less behaviorally problematic but that individual children were not lends support to this hypothesis.

It is worth noting that teachers also did not report academic gains for children due to FOL. Although stronger measurement of child outcomes through direct assessments is critical to be certain that no gains in academic skills occurred, these findings imply that a program like FOL may be important but not sufficient to build children’s cognitive school readiness skills. Improved classroom management and the resulting changes in children’s behavior may have freed up more time for instruction in FOL classrooms; in this way, FOL may have set the preconditions for improved learning. However, children may not have benefitted academically from the intervention because the teachers were not trained sufficiently in the kinds of instructional approaches that would have enabled them to take advantage of that greater instructional time. This suggests that a next critical step in this research would be to pair an SEL model with an academically oriented one to best address the skills gaps of low-income children.

Limitations, Strengths, and Future Directions

Although this study relied on a strong clustered randomized controlled trial design, the findings must be placed in the context of several of our study’s limitations. First, this study was implemented in a single city in the northeastern United States, within a specific policy context that limits the generalizations that can be drawn from our results. Teachers in the Newark preschool programs enrolled in our study met higher levels of credentialing and taught a smaller number of students, on average, than many other preschool teachers serving similarly poor communities nationwide. Second, we recognize that this study yielded relatively little evidence of differences between treatment and control groups as reported by teachers. The bulk of significant differences between treatment- and control-assigned programs were found using observational tools at the classroom and child levels. This highlights the challenges and the opportunities of using multiple methods in evaluations of educational intervention and remains an intriguing area for future research. Third, the FOL intervention was implemented through multiple components, including training, classroom-based consultation, and stress-management for teachers, as well as more child-focused services for students. Because of the bundled nature of the package of services provided, we were unable to detect which components of the service delivery model were most effective in promoting benefits to teachers and students, suggesting key avenues for future research. Similarly, given the single (spring) timing of data collection, we could not tease out how the timing of components of the model played out in terms of effects on classrooms and children.

In conclusion, public support for early childhood education programs is growing, and researchers and policymakers alike are looking to such programs to close the pernicious achievement gap facing low-income children before they enter school. This study is part of an emerging body of research on the efficacy of SEL programs for preschool children living in the context of poverty. Understanding the value added by these programs (e.g., in increased instructional time and increased classroom engagement) as well as their limitations (e.g., in teachers’ instructional quality and children’s academic skills) will help experts design the next set of more effective interventions for low-income children.

Footnotes

Preschools were contacted by phone to gauge their interest in the study and then visited in person. Once the process reached the in-person visit stage of recruitment, no sites declined to participate in the demonstration.

The city of Newark is divided into five wards: North, South, Central, West, and the Ironbound (East). The Newark population consists mainly of African Americans and Hispanics, largely divided by race/ethnicity in specific wards. Also, the city has a large Portuguese or Portuguese-speaking population that is located in the Ironbound district.

Because the lead teacher in one intervention site was chronically ill, the assistant teacher completed the self-survey and reports on children.

Approximately 9% of consented children were no longer enrolled in their FOL classrooms by the spring follow-up period. If children had moved from the FOL site in the past 30 days, the FOL teacher completed the report.

Substitute children were preselected for coders so that five children could be observed even if a preselected child was not in attendance on the day of the observations.

For all of the measures described in this section, average scores were computed for the scales as long as more than 70% of the items were nonmissing.

Note that using a three-group split instead of a median split yielded very similar results.

This approach is analogous to using the more typical interaction term but allows for variation in the effect of baseline covariates across groups (rather than constraining them to be equal).

Contributor Information

Pamela Morris, Applied Psychology, New York University; MDRC.

Megan Millenky, MDRC.

C. Cybele Raver, Applied Psychology, New York University.

Stephanie M. Jones, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Harvard University

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM (1997). Caregiver-Teacher Report Form (C-TRF) Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA). Burlington, VT: University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DH, Brown SA, Meagher S, Baker CN, Dobbs J, & Doctoroff GL (2006). Preschool-based programs for externalizing problems. Education & Treatment of Children, 29, 311–339. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DH, McWilliams L, & Arnold EH (1998). Teacher discipline and child misbehavior in day care: Untangling causality with correlation data. Developmental Psychology, 34, 276–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DH, Ortiz C, Curry JC, Stowe RM, Goldstein NE, Fisher PH, … Yershova K (1999). Promoting academic success and preventing disruptive behavior disorders through community partnership. Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 589–598. [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Granger D, & Razza RP (2005). Cortisol reactivity is positively related to executive function in preschool children attending Head Start. Child Development, 76, 554–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, & Morris P (2006). The bioecological model of human development In Lerner RM & Damon W (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., pp. 793–828). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bulotsky-Shearer RJ, Wen X, Faria A, Hahs-Vaughn DL, & Korfmacher J (2012). National profiles of classroom quality and family involvement: A multilevel examination of proximal influences on Head Start children’s school readiness. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27, 627–639. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal M, Vandergrift N, Pianta RC, & Mashburn A (2010). Threshold analysis of association between child care quality and child outcomes for low-income children in pre-kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25(2), 166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DH, & Farran DC (1991). Behavioral risk factors in kindergarten. Early Childhood Research Quarterly,3, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM, & Hedges LV (1994). The handbook of research synthesis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Curbow B, Spratt K, Ungaretti A, McDonnell K, & Breckler S (2000). Development of the Child Care Worker Job Stress Inventory. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15, 515–536. [Google Scholar]

- Daley D, Renyard L, & Sonuga-Barke EJ (2005). Teachers’ emotional expression about disruptive boys. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(1), 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, French DC, & Patterson GR (1995). The development and ecology of antisocial behavior In Cicchetti D & Cohen D (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (Vol. 2, pp. 421–471). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA (1986). A social information processing model of social competence in children In Perlmutter M (Ed.), Minnesota symposium on child psychology (Vol. 18, pp. 77–125). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue P, Falk B, & Provet AG (2000). Mental health consultation in early childhood. Baltimore, MD: Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Downer JT, Hamre BK, Pianta RC, Lima O, Yoder B, & Booren L (2008). Classroom Assessment Scoring System––Child Version (CLASS-C). Unpublished measure, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

- Early DM, Iruka IU, Ritchie S, Barbarin OA, Winn D-M, Crawford GM, … Pianta RC (2010). How do pre-kindergarteners spend their time? Gender, ethnicity, and income as predictors of experiences in pre-kindergarten classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 177–193. [Google Scholar]

- Garet M, Porter A, Desimone L, Birman B, & Yoon K (2001). What makes professional development effective?Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 38, 915–945. [Google Scholar]

- Gennetian L, Magnuson K, & Morris PA (2008). From statistical association to causation: What developmentalists can learn from instrumental variables techniques coupled with experimental data. Developmental Psychology, 44, 381–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D, Meyer RH, & Wiseman M (1993). Prying the lid from the black box: Plotting evaluation strategy for welfare employment and training programs. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, Institute for Research on Poverty. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, & Pianta RC (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76, 949–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC, Downer JT, DeCoster J, Mashburn AJ, Jones SM, … Hamagami A (2013). Teaching through interactions: Testing a developmental framework of teacher effectiveness in over 4,000 classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 113, 461–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindson B, Byrne B, Fielding-Barnsley R, Newman C, Hine DW, & Shankweiler D (2005). Assessment and early instruction of preschool children at risk for reading disability. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 687–704. [Google Scholar]

- Jones SM, Brown JL, & Aber JL (2011). Two year impacts of a universal school-based social-emotional and literacy intervention: An experiment in translational developmental research. Child Development, 82, 533–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Barker P, Colpe L, Epstein J, Gfroerer J, Hiripi E, … Zaslavsky A (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Paro KM, Pianta RC, & Stuhlman M (2004). The Classroom Assessment Scoring System: Findings from the prekindergarten year. Elementary School Journal, 104, 409–426. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee VE, & Burkam DT (2002). Inequality at the starting gate: Social background differences in achievement as children begin school. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Lench HC, & Levine LJ (2005). Effects of fear on risk and control judgments and memory: Implications for health promotion messages. Cognition & Emotion, 19, 1049–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Li-Grining CL, Raver CC, Champion K, Sardin L, Metzger M, & Jones SM (2010). Understanding and improving classroom emotional climate and behavior management in the “real world”: The role of Head Start teachers’ psychosocial stressors. Early Education & Development, 21, 65–94. [Google Scholar]

- LoCasale-Crouch J, Konold T, Pianta R, Howes C, Burchinal M, Bryant D, … Barbarin O (2007). Observed classroom quality profiles in state-funded pre-kindergarten programs and associations with teacher, program, and classroom characteristics. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Madison-Boyd S, Raver CC, Aufmuth E, Barden K, Jones-Lewis D, & Williams M (2006). The Chicago School Readiness Project mental health consultation manual. Unpublished manual.

- McClelland MM, Morrison FJ, & Holmes DL (2000). Children at risk for early academic problems: The role of learning-related social skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(3), 307–329. [Google Scholar]

- Morris P, Duncan GJ, & Clark-Kauffman E (2005). Child well-being in an era of welfare reform: The sensitivity of transitions in development to policy change. Developmental Psychology, 41, 919–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). Academic Rating Scale. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- National Education Goals Panel. (1996). The national education goals report: Building a nation of learners. Washington,DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network. (2002). The relation of global first grade classroom environment to structural classroom features, teacher, and student behaviors. The Elementary School Journal, 102(5), 367–387. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR (1982). Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta R, Howes C, Burchinal M, Bryant D, Clifford R, Early D, & Barbarin O (2005). Features of pre-kindergarten programs, classrooms, and teachers: Do they predict observed classroom quality and child-teacher interactions? Applied Developmental Science, 9(3), 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, La Paro KM, & Hamre BK (2006). Classroom Assessment Scoring System manual, preschool (Pre-K) version. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia, Center for Advanced Study of Teaching and Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Puma MJ, Olsen RB, Bell SH, & Price C (2009). What to do when data are missing in group randomized controlled trials (NCEE Publication No. 2009–0049). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. [Google Scholar]

- Quas JA, Bauer A, & Boyce WT (2004). Physiological reactivity, social support, a memory in early childhood. Child Development, 75, 797–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quint JC, Bos JM, & Polit DF (1997). New chance: Final report on a comprehensive program for young mothers in poverty and their children. New York, NY: MDRC. [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC (2002). Emotions matter: Making the case for the role of young children’s emotional development for early school readiness. Social Policy Reports, 16(3), 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC, Garner P, & Smith-Donald R (2007). The roles of emotion regulation and emotion knowledge for children’s academic readiness: Are the links causal? In Pianta B, Snow K, & Cox M (Eds.), Kindergarten transition and early school success (pp. 121–147). Towson, MD: Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC, Jones SM, Li-Grining CP, Metzger M, Smallwood K, & Sardin L (2008). Improving preschool classroom processes: Preliminary findings from a randomized trial implemented in Head Start settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 63(3), 253–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC, Jones SM, Li-Grining CP, Zhai F, Bub K, & Pressler E (2009). CSRP’s impact on low-income preschoolers’ pre-academic skills: Self-regulation as a mediating mechanism. Unpublished paper. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Raver CC, Jones SM, Li-Grining CP, Zhai F, Bub K, & Pressler E (2011). CSRP’s impact on low-income preschoolers’ pre-academic skills: Self-regulation and teacher-student relationships as two mediating mechanisms. Child Development, 82, 362–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC, Jones SM, Li-Grining CP, Zhai F, Metzger M, & Solomon B (2009). Targeting children’s behavior problems in preschool classrooms: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 302–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman SE, La Paro KM, Downer JT, & Pianta RC (2005). The contribution of classroom setting and quality of instruction to children’s behavior in kindergarten classrooms. Elementary School Journal, 105(4), 377–394. [Google Scholar]

- Schutz PA, & Davis HA (2000). Emotions and self-regulation during test taking. Educational Psychologist, 35, 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2/3), 25–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. (2005, May). Head Start impact study: First year findings. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Wasik BA, & Hindman AH (2011). Improving vocabulary and pre-literacy skills of at-risk preschoolers through teacher professional development. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103, 455–469. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C (1998). Preventing conduct problems in Head Start children: Strengthening parenting competencies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 6, 715–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Reid JM, & Hammond M (2001). Preventing conduct problems, promoting social competence: A parent and teacher training partnership in Head Start. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(3), 238–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Reid JM, & Stoolmiller M (2008). Preventing conduct problems and improving school readiness: Evaluation of the Incredible Years teacher and child training programs in high-risk schools. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 471–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst GJ, & Lonigan CJ (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Development, 69, 848–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]