Abstract

We investigated the strongly red-shifted singlet oxygen (1O2) phosphorescence spectra in an aqueous preparation of C60 buckminsterfullerene. The ~10 nm red shift was associated with H2O dispersions of C60 nanoaggregates (C60)n that can photosensitize 1O2 in their polarizable cores. In contrast to 1O2 produced by the water-soluble C60-(γ-cyclodextrin)2 complex, 1O2 trapped inside (C60)n was short-lived (~2–3 μs), insensitive to solvent and 1O2 quenchers, and did not induce photocytotoxicity. To our knowledge, 1O2 spectrum from (C60)n is the most red-shifted 1O2 spectrum recorded to date and it may be used to probe the inner polarizability of carbon (nano)aggregates.

Introduction

Buckminsterfullerene C60 is a known photosensitizer of singlet oxygen (1O2) in nonpolar solvents (1,2). Much effort has been expended to solubilize C60 in H2O. One successful strategy is to disperse C60 by different means (3,4) to form nano-aggregates (C60)n. Solubilization of C60 in aqueous media is driven by biological applications that may involve photosensitization of 1O2. The latter is best studied spectrally by its IR phosphorescence. However, we did not observe any correlation between the spectrally determined 1O2 production by different aqueous preparations of C60 and their in vitro phototoxicities. Interestingly, we noticed that the spectra of 1O2 were often red-shifted in aqueous (C60)n dispersions which prompted us to examine 1O2 production by aggregated C60 in more detail.

Experimental Section

Singlet oxygen lifetimes were measured using a laser pulse spectrometer described in detail elsewhere (6). Briefly, the apparatus utilized a Surelite II laser (Continuum, Santa Clara, CA) for excitation. A germanium diode (Model 403 HS, Applied Detector Corporation, Fresno, California) in conjunction with an efficient optical system was used for signal detection. Data were acquired on a HP 54111D Digitizing Oscilloscope (Hewlett Packard Colorado Springs, CO) interfaced to a PC computer. Singlet oxygen was produced by single pulse excitation of C60 preparations at 355 nm (5 ns duration and ca. 35 mJ energy). The 1O2 lifetime was calculated from the monoexponential decay of its phosphorescence observed through an interference filter at 1270 nm.

The steady-state 1O2 phosphorescence spectra were recorded on a steady-state 1O2 spectrophotometer featuring an optimized optical system as in our pulse 1O2 spectrophotometer. Samples were excited from a 500 Watts Hg lamp operating at 300 Watts through a 366 nm interference filter in combination with KG3 heat-removing glass filter. The 1O2 phosphorescence spectra were recorded over the range of 1200–1350nm during one ca. 30 s scan and were normalized to the same number of absorbed photons at the excitation wavelength. Perinaphthenone was used as a standard for the 1O2 quantum yield calculations.

Absorption spectra were measured using a HP Diode Array Spectrophotometer model 8452A (Hewlett Packard Co., Palo Alto, CA). The relative number of absorbed photons at the excitation wavelength was calculated using the Beer-Lambert law. The samples were prepared in a suprasil fluorescence cuvette (0.5 cm pathlength), and were air-equilibrated or purged with either oxygen or nitrogen gasses, as required.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were taken on a Tecnai-12 Bio-Twin transmission electron microscope (FEI, The Netherlands.) operating at 80 kV. TEM grids were prepared by evaporating approximately 20 μL of aqueous fullerenes solution/dispersion onto a 300 mesh carbon-coated copper grid.

Results and Discussion

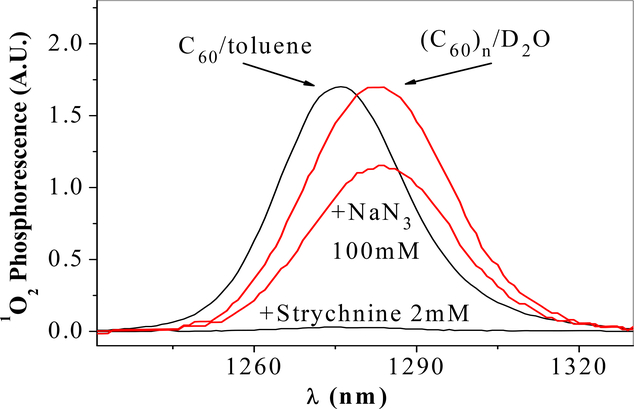

The steady-state spectrum of 1O2 phosphorescence measured from (C60)n in O2-saturated D2O is shown in Fig. 1, while Fig. 2 shows the corresponding absorption spectrum; the transmission electron microscope (TEM) image of (C60)n nanoparticles is shown in the insert. Fig.1 also shows 1O2 emission spectrum generated by C60 in toluene. The peak position of this spectrum is 1273 nm, while the 1O2 spectrum from (C60)n in D2O is red-shifted by ca. 10 nm. A similar red shift was consistently observed for (C60)n dispersed without any additives in H2O. The red-shifted spectrum in D2O or H2O is due to 1O2, because it was totally dependent on the concentration of oxygen (5) (Fig.3). Results from time-resolved technique (6) support this conclusion.

Figure 1.

1O2 emission spectra from C60 in toluene and (C60)n in D2O in the absence and presence of strychnine (toluene) and NaN3 (D2O). While NaN3 at 2 mM did not show any 1O2 quenching (not shown), the 1O2 quenching by NaN3 at 100 mM may also involve C60 excited state(s). Spectra in toluene were reduced ca. 4 times; λex=366 nm.

Figure 2.

Absorption spectra of C60 in toluene and C60-(γ-CD)2 and (C60)n in D2O. Insert shows TEM image of (C60)n.

Figure 3.

1O2 emission spectra from (C60)n in D2O saturated with oxygen, air and nitrogen.

Surprisingly, the 1O2 lifetime (τso) photosensitized by the (C60)n dispersion in D2O was the same as that in H2O, even though τso is ca. 50 μs in our D2O sample (7), compared to 3.1 μs in water (8). Fig. 4 shows the decays of 1O2 produced by (C60)n and C60-(γ-CD)2 in D2O, and by C60 in toluene. The 1O2 transient decay of (C60)n dispersed in H2O then extracted into toluene is also presented. The decay of 1O2 produced by C60-(γ-CD)2 confirms that τso in our D2O sample is ~50 μs. A lack of τso increase in (C60)n/D2O suggests that 1O2 emission was not from bulk D2O, but rather from the (C60)n core (9). To test this assumption we applied two efficient physical 1O2 quenchers: NaN3 in H2O/D2O (10), and strychnine (11) in toluene. We also used a chemical quencher 2,5-dimethylfuran, which was effective in solution but not in the nanoaggregates (not shown).

Figure 4.

Decays of 1O2 emission photosensitized by (C60)n and C60-(γ-CD)2 in D2O and by C60 in toluene. Back extraction of (C60)n from D2O to toluene (adjacent curve) produced the same τso=28.7μs. Decays were produced by single laser pulses 355 nm.

Quenchers provide information on 1O2 fate in solution. However, if the quenchers are too large to penetrate the aggregates, they will not quench 1O2 there. The cavities in (C60)n seem to be small and penetrable only by dissolved O2, which facilitates 1O2 production. We found that, indeed, whenever 1O2 spectrum was red-shifted, it was largely unaffected by quenchers present at concentrations that totally abolish the usual 1O2 emission. These observations support our notion that 1O2 must be photoproduced and then deactivated mostly inside the (C60)n aggregates and not in solution. The τso of 1O2 inside the (C60)n is solvent-independent; its estimated value, ca. 3 μs, is close to the τso in H2O. It seems that the conjugated double bond system of C60 quenches 1O2, thus controlling its lifetime in the (C60)n microenvironment. The π electrons are also responsible for the high polarizability of the C60 aggregates (vide infra). These results show that two milieus must be considered for proper analysis of 1O2 photosensitization by aggregated C60 in aqueous solutions. We modeled this by using C60 and γ-cyclodextrin (γ-CD).

We prepared non-aggregated water-soluble C60 by complexation with γ-CD (12,13). The 1O2 spectrum photogenerated by the C60-(γ-CD)2 complex in D2O does not appear to be red shifted and is sensitive to 1O2 quenchers (Fig. 5). However, upon total quenching of the emission from D2O, there was a small contribution from the red-shifted 1O2 spectrum, revealing the presence of (C60)n (Fig. 5). Relative contribution from the (C60)n emission was even higher for H2O/γ-CD (Fig.5) due to the shorter τso(H2O) diminishing the usual 1O2 emission more in H2O than in D2O. C60-(γ-CD)2 is not stable in H2O forming yellow colored (C60)n over time, a process that is accelerated by heat. Thus, both soluble monomeric C60 and dispersed (C60)n nanoparticles can be present simultaneously in aqueous solutions containing γ-CD.

Figure 5.

1O2 emission spectra from C60-(γ-CD)2 in D2O and H2O in the absence and presence of NaN3 (D2O). As expected, the spectrum photosensitized by perinaphthenone (P) was completely quenchable by azide; NaN3 (2 mM) also totally quenched “the usual” 1O2 emission from C60-(γ-CD)2 (not shown). λex=366 nm.

The existence of two clearly different milieus may affect calculation of 1O2 quantum yield (Φso) based on spectral data. Φso is usually measured against a known standard applied in the same solvent, which ensures the same nonradiative (1/τso) and radiative (kr) rate constants for 1O2 decay. While both constants are solvent-dependent (14–17), kr is more difficult to measure and compensation between different environments is more complicated due to lack of reliable values. Obviously, simple comparison of 1O2 spectra may yield incorrect Φso, if more than a single milieu is involved in 1O2 processes. We measured Φso by different C60 preparations (Table 1) considering two milieus, when pertinent.

Table 1.

The quantum yield of 1O2 photosensitization (Φso) by different C60 preparations.

| C60 Preparation | Φso | Φsosolution | Phototoxicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| C60/toluene | 1 | 1 | N/A |

| (C60)n/D2O/H2O | ~1* | 0 | No |

| C60-(γ-CD)2/D2O | 1 | 1 | Yes |

Measurements used perinaphthenone as a 1O2 photosensitization standard (24).

For calculations in (C60)n/D2O, kr was estimated from an extrapolation based on the α dependence (16), while 1/τso was measured inside (C60)n and in solutions. The following values were used: kr, 0.21, τso 54 μs in D2O, and kr, 3.8, τso 2.9 μs in (C60)n. All solutions were saturated with oxygen, and λ=366 nm was used for excitation. It is obvious that Φso calculations for different (C60)n preparations could produce a range of nonsense values (not shown), if a single milieu would had been considered. N/A, not applicable.

Our measurements for C60 in solution are in general agreement with the published Φso values compiled by Prat et al. (18) who also investigated the inclusion complexes of C60 with γ-cyclodextrin. These complexes featured close to unity triplet quantum yields and high Φso values (18). For C60 nanoaggregates, the accuracy of our φ estimation in the aggregates is determined primarily by the unknown radiative rate constant. This constant cannot be eliminated (reduced) from the equation by the usual application of 1O2 standard, as there is no 1O2 reference standard small enough to be placed into the cavity of C60 aggregates. Therefore, our φ estimate (Table 1) is based on extrapolation from the published polarizability dependence (16). While this arbitrary procedure can produce φ values larger than unity, it does suggest that φ is close to unity in oxygen purged solutions when the aggregate cavities are saturated with oxygen molecules.

Notice that physicochemically correct Φso values may not always correlate with 1O2-induced photocytotoxicity. A simple correlation is expected only for 1O2 production in solution, but not inside the (C60)n particles that deactivate 1O2 prior to diffusion out. Thus, only C60-(γ-CD)2, which is a perfect 1O2 generator (Table 1), was phototoxic to cell cultures, while (C60)n was not (to be published later). A correct understanding of 1O2 generation by aqueous C60 preparations allows us to reliably predict phototoxicity by considering 1O2 sensitivity to solvent and quenchers, which concurs with the spectral shift of 1O2 emission.

What is the origin of this red shift? Unlike kr and τso, 1O2 emission energy is less affected by solvents. Nonetheless, red shifts have been observed (19–21) and linked to increasing solvent polarizability (α) (16). The most red-shifted 1O2 spectra were in iodinated solvents (16), reaching a maximum at around 7824 cm−1 (1278 nm). The 1O2 spectrum that we measured in methylene iodide (n=1.74) shows similarly red-shifted (~9 nm) peak position (not shown). The spectrum in (C60)n is even more red-shifted (7798 cm−1), extrapolating (16) to α.≈0.46 that would match solvent refractive index n=1.887 (in diamond n=2.417 (22)). Moreover, the red shifts were empirically associated with the increasing kr values (16), hence, kr should also be enhanced in (C60)n. We used this association to estimate kr inside (C60)n for 1O2 quantum yield calculation shown in Table 1.

The above α estimate reveals a very polarizable (C60)n core probed by 1O2. This core is hydrophobic and not accessible to solvent but to O2 that slowly diffuses in and out with a dwelling time longer than 3 μs (1O2 cannot diffuse out in its lifetime). While at least four C60 must aggregate to create a protective cavity for O2, the average (C60)n size in our preparation estimated from the TEM images was n=30–60 molecules. (C60)n seems to be a dynamic formation showing Brownian motion that creates cavities large enough (23) to host O2 that, upon excitation, can convert to 1O2 (Fig. 5).

In summary, to our knowledge, we found the most red-shifted 1O2 phosphorescence spectrum recorded to date generated in aqueous preparations of (C60)n. The 1O2 spectral shift concurs with 1O2 sensitivity to solvent and quenchers, which may be used to reliably predict phototoxicity exerted by 1O2 in different preparations of carbon nanoaggregates. Moreover, since the 1O2 spectral red shift correlates well with polarizability, 1O2 acts as a probe providing a unique insight into the inner polarizability of (C60)n aggregates.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIEHS.

We thank Ms. D. Sutton and Mr. J. Horton, NIEHS, for providing the TEM images.

REFERENCES

- (1).Terazima M, Hirota N, Shinohara H, Saito Y: Photothermal Investigation of the Triplet-State of C60. Journal of Physical Chemistry 95 (1991) 9080–85. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Nagano T, Arakane K, Ryu A, Masunaga T, Shinmoto K, Mashiko S, Hirobe M: Comparison of Singlet Oxygen Production Efficiency of C-60 with Other Photosensitizers, Based on 1268-Nm Emission. Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 42 (1994) 2291–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Andrievsky GV, Kosevich MV, Vovk OM, Shelkovsky VS, Vashchenko LA: On the Production of an Aqueous Colloidal Solution of Fullerenes. Journal of the Chemical Society-Chemical Communications (1995) 1281–82. [Google Scholar]

- (4).S Deguchi Alargova RG, Tsujii K: Stable dispersions of fullerenes, C-60 and C-70, in water. Preparation and characterization. Langmuir 17 (2001) 6013–17. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Notice a stronger than expected dependence of signal intensity on oxygen concentration between air and oxygen saturated solutions. This is due to the preloading of the nanoaggregate cavities with gasses during purging with limited subsequent gas exchange on the time scale of photochemical excitation and emission processes.

- (6).P Bilski Chignell CF: Optimization of a pulse laser spectrometer for the measurement of the kinetics of singlet oxygen O-2(Delta(1)(g)) decay in solution. Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods 33 (1996) 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).The actual measured singlet oxygen lifetime depends on the purity and water content in a given solvent batch. Handling and storage of deuterium oxide may introduce water which shortens singlet oxygen lifetime. The lifetimes presented in the manuscript are actual measured values in the solvents we used, and not the values that can be observed in “dry” solvents.

- (8).C Schweitzer R Schmidt: Physical mechanisms of generation and deactivation of singlet oxygen. Chemical Reviews 103 (2003) 1685–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).It should be also mentioned here that the lifetime of singlet of oxygen generated from the aggregate interior could have theoretically been dictated by the kinetics of a long-lived photosensitizer triplet rather than the actual singlet oxygen decay. However, such a possibility can be ruled out owing to the very strong steady-state phosphorescence that requires a long lifetime. Otherwise, to satisfy the intense singlet oxygen phosphorescence, k radiative would be too high to agree with the kr-polarizability dependence reported by Wessels and Rodgers

- (10).MY Li Cline CS, Koker EB, Carmichael HH, Chignell CF, Bilski P: Quenching of singlet molecular oxygen (O-1(2)) by azide anion in solvent mixtures. Photochemistry and Photobiology 74 (2001) 760–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).AA Gorman I Hamblett, K Smith, MC Standen: Strychnine - a Fast Physical Quencher of Singlet Oxygen (1-Delta-G). Tetrahedron Letters 25 (1984) 581–84. [Google Scholar]

- (12).ZI Yoshida Takekuma H, Takekuma SI, Matsubara Y: Molecular Recognition of C-60 with Gamma-Cyclodextrin. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition in English 33 (1994) 1597–99. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Y Nishibayashi Saito M, Uemura S, Takekuma S, Takekuma H, Yoshida Z: Buckminsterfullerenes - A non-metal system for nitrogen fixation. Nature 428 (2004) 279–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ogilby PR: Solvent effects on the radiative transitions of singlet oxygen. Accounts of Chemical Research 32 (1999) 512–19. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Scurlock RD Nonell S, Braslavsky SE, Ogilby PR: Effect of Solvent on the Radiative Decay of Singlet Molecular-Oxygen (a(1)Delta(G)). Journal of Physical Chemistry 99 (1995) 3521–26. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wessels JM, Rodgers MAJ: Effect of Solvent Polarizability on the Forbidden (1)Delta-G- (3)Sigma-G(−) Transition in Molecular-Oxygen - a Fourier-Transform near-Infrared Luminescence Study. Journal of Physical Chemistry 99 (1995) 17586–92. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bilski P Holt RN, Chignell CF: Properties of singlet molecular oxygen O-2((1)Delta(g)) in binary solvent mixtures of different polarity and proticity. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology a-Chemistry 109 (1997) 243–49. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Prat F Marti C, Nonell S, Zhang XJ, Foote CS, Moreno RG, Bourdelande JL, Font J: C-60 Fullerene-based materials as singlet oxygen O-2((1)Delta(g)) photosensitizers: a time-resolved near-IR luminescence and optoacoustic study. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 3 (2001) 1638–43. [Google Scholar]

- (19).A Bromberg Foote CS: Solvent Shift of Singlet Oxygen Emission Wavelength. Journal of Physical Chemistry 93 (1989) 3968–69. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Byteva IM Gurinovich GP, Losev AP, Mudryi AV: Spectral Shifts of Singlet-Molecular-Oxygen Luminescence Bands in Different Solvents. Optika I Spektroskopiya 68 (1990) 545–48. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Poulsen TD Ogilby PR, Mikkelsen KV: The a(1)Delta(g) -> X-3 Sigma(−)(g) transition in molecular oxygen: Interpretation of solvent effects on spectral shifts. Journal of Physical Chemistry A 103 (1999) 3418–22. [Google Scholar]

- (22).For oxygen trapped andpa excited inside diamond, singlet oxygen emission spectrum would be expected to be even more red-shifted than that in C60 nanoaggregates.

- (23).Molecular dynamic modeling confirms that the cavity created by four C60 molecules can indeed accommodate an oxygen molecule.

- (24).Schmidt R Tanielian C, Dunsbach R, Wolff C: Phenalenone, a universal reference compound for the determination of quantum yields of singlet oxygen O2(1-Delta-G) sensitization. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology a-Chemistry 79 (1994) 11–17. [Google Scholar]