Dirac-like electrons in Bi-Sb alloys are extremely effective in generating spin current and have large spin current mobility.

Abstract

We have studied the charge to spin conversion in Bi1−xSbx/CoFeB heterostructures. The spin Hall conductivity (SHC) of the sputter-deposited heterostructures exhibits a high plateau at Bi-rich compositions, corresponding to the topological insulator phase, followed by a decrease of SHC for Sb-richer alloys, in agreement with the calculated intrinsic spin Hall effect of Bi1−xSbx. The SHC increases with increasing Bi1−xSbx thickness before it saturates, indicating that it is the bulk of the alloy that predominantly contributes to the generation of spin current; the topological surface states, if present, play little role. Unexpectedly, the SHC is found to increase with increasing temperature, following the trend of carrier density. These results suggest that the large SHC at room temperature, with a spin Hall efficiency exceeding 1 and an extremely large spin current mobility, is due to increased number of thermally excited Dirac-like electrons in the L valley of the narrow gap Bi1−xSbx alloy.

INTRODUCTION

Generation of spin current or flow of spin angular momentum lies at the heart of modern spintronics. The power consumption of a spintronic device is directly related to its efficiency for converting a charge current that dissipates energy to a dissipative spin-polarized current or a dissipationless spin current (1, 2). A conventional means for creating a flow of spin angular momentum is by passing a charge current across a ferromagnetic metal (FM) that converts to a spin-polarized current. The efficacy of this process is proportional to the spin polarization of the FM. More recently, generation of spin current from a charge current passed along a nonmagnetic metal (NM) (3–5) or interface of materials with strong spin-orbit coupling (6–8) has emerged as an attractive alternative. In particular, the discovery (9) of the giant spin Hall effect (SHE) in 5d transition heavy metals (HMs) has triggered substantial effort in exploiting the spin current to electrically control magnetization of ferromagnets placed nearby. In HM/FM bilayer systems, the magnetization of the FM layer can absorb the orthogonal component of the nonequilibrium spin density originating from the SHE, giving rise to current-induced spin-orbit torque (SOT) at the HM/FM interface (10–12). The SOT in these bilayers enabled current-induced magnetization switching (9, 13), current-driven motion of chiral domain walls and skyrmions (14–16), and magnetoresistance (MR) effect that depends on the SHE, often referred to as the spin Hall MR (17, 18). The figure of merit of the charge to spin conversion in SHE is known as the damping-like spin Hall efficiency ξDL that includes nonideal spin transmission across the interface (19, 20). Using ξDL, the spin current js generated from a charge current jc passed to an NM layer and entering the FM layer can be expressed as js = ξDL(ℏ/2e)jc, where ℏ is the reduced Planck constant and e is the electrical charge. As ξDL may depend on the longitudinal conductivity σxx of the NM layer, which varies with extrinsic factors such as impurity concentration and film texture, it is customary to use the spin Hall conductivity (SHC) σSH, defined through the relation σSH = ξDL ⋅ σxx, to provide a measure of the anomalous transverse velocity the carriers obtain via the SHE (5).

Recent advances in the understanding of topological insulators (21) and Weyl semimetals (22) have attracted great interest in exploiting their unique electronic states for spintronic applications. Giant charge to spin conversion efficiencies were found in heterostructures that consist of a topological insulator and a ferromagnetic/ferrimagnetic layer (23–32). The large charge to spin conversion efficiency observed in these systems was attributed to the current-induced generation of spin density enabled by the spin momentum locked surface states of topological insulators. Ideally, the bulk of a topological insulator should be insulating. In practice, however, it remains as a great challenge to limit the current flow within the bulk of this material class. This is particularly the case for thin-film heterostructures in which imperfect crystal structures and interdiffusion with the adjacent layers may reduce or eliminate the bandgap of the bulk state. To take advantage of the topological surface states in generating spin accumulation, it has been considered detrimental to have current paths in the bulk. In terms of bulk conduction of carriers, the charge to spin conversion efficiency of Bi, a small gap semimetal with large spin-orbit coupling (33, 34) and one of the most used elements in forming topological insulators, has been reported to be extremely small (35, 36) compared to the 5d transition metals. Theoretically, Bi and Bi-Sb alloys have been predicted (37–39) to exhibit considerable SHC due to its unique electronic state.

Here, we show that the charge to spin conversion efficiency that originates from the bulk of Bi1−xSbx alloys is significantly larger than that of the 5d transition metals. The SHC of the alloy increases with increasing thickness before it saturates. This thickness dependence of the SHC, together with its facet independence, suggests that a significant amount of spin current is generated from the bulk of the alloy. We find little evidence of spin current generation from the topological surface states, if they were to exist in the sputtered films used here. The damping-like spin Hall efficiency exceeds 1 for the Bi-rich Bi1−xSbx alloy and decreases with increasing Sb concentration. The alloy composition dependence of the SHC indicates that the SHE of the alloy has considerable contribution from the so-called intrinsic SHE. Unexpectedly, we find that the SHC and the spin Hall efficiency increase with increasing measurement temperature. We find up to threefold (twofold) enhancement of σSH (ξDL) upon increasing the temperature from 10 to 300 K. Although thermal fluctuation is typically detrimental for many key parameters of spintronic devices, the SHC of the Bi1−xSbx alloy is enhanced at higher temperature due to the increased number of carriers at the valleys with large Berry curvature. Our results suggest that these carriers in Bi1−xSbx alloys, particularly in the Bi-rich compositions, have large spin current generation efficiency and equivalent spin current mobility.

RESULTS

Structural characterizations

Thin-film heterostructures with base structure of Sub./seed/[tBi Bi∣ tSb Sb]N/tBi Bi/tCoFeB CoFeB/2 MgO/1 Ta (thicknesses in nanometers) were grown by magnetron sputtering at ambient temperature on thermally oxidized Si substrates. N represents the number of repeats of the Bi∣Sb bilayers. The thicknesses of the Bi (tBi) and Sb (tSb) layers in the repeated structure are set to meet the condition tBi + tSb ∼ 0.7 nm. The nominal composition of CoFeB is Co:Fe:B = 20:60:20 atomic %. Unless noted otherwise, we use 0.5 nm Ta as the seed layer for Bi|Sb multilayers. The capping layer is always fixed to 2 MgO/1 Ta. We assume that the top 1-nm Ta layer is fully oxidized and does not contribute to the transport properties of the films.

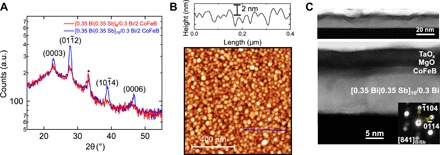

θ − 2θ x-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra of representative films with tBi ∼ tSb ∼ 0.35 nm, N = 8, 16 are shown in Fig. 1A. The films are polycrystalline, and the peaks are indexed on the basis of the hexagonal representation of the rhombohedral Bi1−xSbx (space group ; no. 166) that forms solid solution throughout the composition. Bragg diffraction peaks corresponding to (0003), (), and () crystallographic directions are found. The peak intensities increase with increasing N, reflecting improved crystallinity of the film. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) image of the N = 8 film is shown in Fig. 1B. The root mean square roughness is of the order of 1 nm. Representative cross sectional high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images of the N = 16 film are shown in Fig. 1C. The lower-magnification STEM image at the top panel confirms that the Bi|Sb multilayer is granular and continuous. We find that the average grain size is ∼35 nm. The 2-nm CoFeB and the subsequent capping layers are also continuous and follow the morphology of the multilayer. The bottom panel shows the high-resolution STEM image of the film. The lattice fringes clearly seen in the image reveals the good crystallinity of the Bi∣Sb multilayer. A typical nanobeam diffraction pattern of the Bi|Sb multilayer is shown in the inset of Fig. 1C. The diffraction patterns suggest that the grains are consisted of Bi1−xSbx nanocrystallites with random orientations within the film plane. Although alternating Bi and Sb layers were sputtered to form Bi|Sb multilayers, energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping (see the Supplementary Materials) shows that the two elements intermix to form an alloy rather than a layer-by-layer superlattice.

Fig. 1. Structural characterization of Bi|Sb multilayers.

(A) X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra of 0.5 Ta/[0.35 Bi|0.35 Sb]N/0.3 Bi/2 CoFeB/2 MgO/1 Ta with N = 8 (blue line) and N = 16 (red line). a.u., arbitrary units. (B) AFM image of the N = 8 film. A line profile along the blue solid line drawn in the bottom image is shown at the top. (C) Cross-sectional HAADF-STEM images of the N = 16 structure. Selected nanobeam diffraction pattern of the Bi|Sb multilayer is shown in the inset.

Experimental setup

Because structural characterization show that the two elements intermix and form an alloy, we denote, hereafter, the Bi|Sb multilayers (i.e., [tBi Bi∣tSb Sb]N/tBi Bi) as tBiSb Bi1−xSbx using the total thickness of the multilayer (tBiSb) and the corresponding composition x defined by the relative thickness of the Bi and Sb layers, i.e., . To evaluate the SOT, we pattern Hall bar devices using optical lithography. The nominal channel width w and length L are set to 10 and 25 μm, respectively. Illustration of the Hall bar device and the coordinate system adapted in this work are schematically illustrated in the inset of Fig. 2A. The longitudinal resistance Rxx and the transverse resistance Rxy of the devices were obtained using direct current (DC) transport measurements. Linear fitting to the sheet conductance L/(wRxx) versus the thickness of one of the layers is used to estimate the conductivity σX (X = BiSb, CoFeB, seed layer). The current distribution within the heterostructures is calculated using the thicknesses and conductivities of the conducting layers.

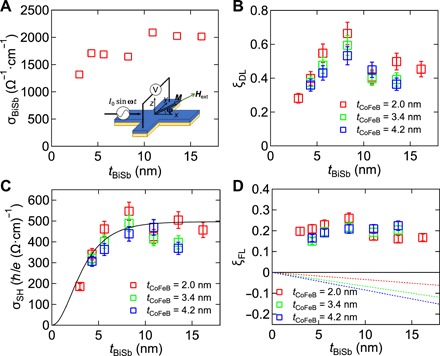

Fig. 2. Bi0.53Sb0.47 thickness dependence of SOT and σSH.

(A) Conductivity σBiSb of Bi0.53Sb0.47 plotted as a function of its thickness tBiSb. Inset: Schematic illustration of a Hall bar device and the coordinate system. (B to D) tBiSb dependence of the damping-like spin Hall efficiency ξDL (B), the SHC σSH (C), and the field-like spin Hall efficiency ξFL (D) of tBiSb Bi0.53Sb0.47/tCoFeB CoFeB. Dotted lines represent contributions from the Oersted field. All data were obtained at 300 K.

We use the harmonic Hall technique (11, 12, 40–42) to quantify the SOT of in-plane magnetized Bi1−xSbx/CoFeB heterostructures. Upon application of an alternating current (AC) I0 sin ωt with frequency ω/2π and amplitude I0 along x, an external magnetic field Hext is applied in the xy plane, while the in-phase first harmonic (V1ω) and the out-of-phase second harmonic (V2ω) Hall voltages along y are simultaneously measured. The Hall resistance is obtained by dividing the harmonic voltages with I0, i.e., . R1ω is dominated by the planar Hall and anomalous Hall resistances, whereas R2ω contains contributions from the current-induced damping-like spin-orbit effective field (HDL), the field-like spin-orbit effective field (HFL), the Oersted field (HOe), and thermoelectric effects [anomalous Nernst effect (ANE) of CoFeB, the ordinary Nernst effect (ONE) of Bi1−xSbx (43), and the collective action of the spin Seebeck effect (SSE) in CoFeB followed by the inverse SHE (ISHE) in Bi1−xSbx (41)]. The magnetic field amplitude dependence of R2ω allows one to differentiate contributions from each effect (see Materials and Methods for the details). HDL (HFL) is related to the damping-like (field-like) spin Hall efficiency via , where jBiSb is the current density in Bi1−xSbx, and Ms and teff ≡ tCoFeB − tD denote the saturation magnetization and the effective thickness of the CoFeB layer, respectively. tD is the thickness of the magnetic dead layer (see the Supplementary Materials for details of magnetic properties of the films). From here, we discuss the values of ξDL and ξFL. To estimate the SHC of Bi1−xSbx, we use the relation σSH = ξDLσBiSb, where the spin transmission across the Bi1−xSbx/CoFeB interface is assumed transparent (19, 20, 44). Taking into account a nontransparent interface will result in larger ξDL (and likely ξFL) and therefore results in larger σSH.

Bi1−xSbx thickness dependence of σSH

We first study the layer thickness dependence of the transport properties of heterostructures with nearly equiatomic Bi0.53Sb0.47 (tBi ∼ tSb ∼ 0.35 nm). The conductivity of Bi0.53Sb0.47 is plotted against tBiSb in Fig. 2A. The slight increase of σBiSb with tBiSb may be related to the larger grain size of thicker films that reduces the scattering at grain boundaries. Note that σCoFeB takes an average value of ∼5.5 × 103 Ω−1 cm−1 and shows little dependence on tBiSb. The tBiSb dependence of ξDL and ξFL for Bi0.53Sb0.47/CoFeB heterostructures measured at 300 K is shown in Fig. 2, B and D, respectively. For a given tBiSb, we studied devices with three different tCoFeB (∼2, 3.4, and 4.3 nm). We find that ξDL of Bi0.53Sb0.47 has the same sign with that of Pt (45) and is consistent with previous reports on molecular beam epitaxy (MBE)–grown Bi0.9Sb0.1 (31) and stoichiometric Bi2Se3 (23, 29) topological insulators. At tBiSb ∼ 8 nm, ξDL reaches a maximum of ∼0.65. This value is significantly larger than those found in HMs but lower than some recent reports on Bi-based topological insulators (23, 28, 30, 31). ξDL shows little dependence on tCoFeB, indicating that the CoFeB layer plays little role in setting the SOT of the heterostructures. To take into account the change of σBiSb with tBiSb, we plot the SHC σSH = ξDLσBiSb against tBiSb in Fig. 2C. σSH increases with increasing tBiSb and tends to saturate beyond tBiSb of ∼8 nm. This thickness dependence resembles that expected for the bulk SHE in Bi0.53Sb0.47 and is inconsistent with the surface state–dominant scenario (23, 46) or with the quantum confinement picture (30). We fit all data using the relation with the bulk SHC and the spin diffusion length λ as the fitting parameters (47). We find and λ = 2.3 ± 0.4 nm for Bi0.53Sb0.47.

Figure 2D illustrates the tBiSb dependence of ξFL for heterostructures with different CoFeB thicknesses. The contribution from HOe, which takes the form of HOe/jBiSb = 2πtBiSb [10−1 Oe/(A · cm−2)] according to Ampère’s law, is shown by the dotted lines in Fig. 2D. Note that HOe, which is negative in our convention, is subtracted from the total field-like SOT to calculate ξFL. We find that HFL is opposite to the Oersted field and ξFL takes a constant value of ~0.2 throughout the range of tBiSb studied. The sign of ξFL for Bi0.53Sb0.47/CoFeB agrees with that of metallic Pt/Co/AlOx (12), but is opposite to that found in Bi2Se3/NiFe (23) and MoS2/CoFeB (48). The nearly constant ξFL against tBiSb is observed for all structures with different tCoFeB. The distinct tBiSb dependence of ξFL and ξDL suggests that the two orthogonal components of SOT originate from phenomena of different characteristic length scales (11, 49).

Bi1−xSbx composition and facet dependence of σSH

The bulk Bi1−xSbx alloy is known to be a semiconductor with a small bandgap hosting topological surface states for 0.09 ≤ x ≤ 0.22 and is semimetallic for the other compositions (33, 34, 50, 51). In an effort to shed light on the origin of the SOT, we investigate the Sb concentration (x) dependence of σSH and related parameters in 10 Bi1−xSbx/2 CoFeB heterostructures. To characterize the basic transport properties of the Bi1−xSbx alloy, we also deposited and measured stacks without the CoFeB layer (i.e., tCoFeB = 0). We have excluded pure Bi (x = 0) from this study due to its large sheet resistance (considerably larger than those of the x ≠ 0 alloys) and island-like morphology, which may result in highly nonuniform current flow within the CoFeB layer. For alloys with x > 0, the surface roughness notably improves, as shown in Fig. 1B. Figure 3A shows the x dependence of σBiSb: σBiSb increases monotonically with increasing Sb concentration. This is consistent with previous report on the transport properties of the bulk Bi1−xSbx alloy (50), where it was shown that Bi1−xSbx gradually changes from being a semiconductor to a semimetal with increasing Sb concentration. As shown in Fig. 3B, the ordinary Hall coefficient RH ≡ RxytBiSb/Hz (Hz is the external field along z) also varies monotonically with increasing x. In our convention, RH > 0 (RH < 0) corresponds to carrier transport being dominated by electrons (holes). We find that the carriers of Bi-rich alloys are electron dominant, whereas the Sb-rich structures are hole dominant, accompanied by a smooth sign change of RH at x ∼ 0.55. This reflects the multicarrier nature of the polycrystalline Bi1−xSbx films, which have at least one hole and one electron pockets at the Fermi level. We note that this differs from the ternary (Bi1−xSbx)2Te3 topological insulator for which RH diverges and abruptly changes sign when traversing the Dirac point (26).

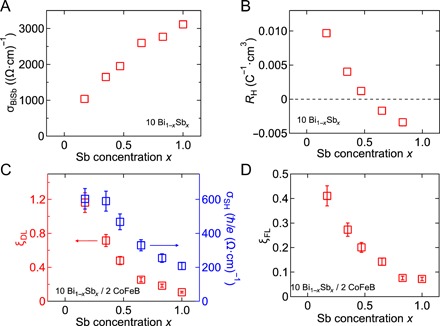

Fig. 3. Bi1−xSbx composition dependence of carrier transport and σSH.

(A and B) Sb concentration x dependence of the conductivity σBiSb (A) and the Hall coefficient RH (B) of Bi1−xSbx with tBiSb = 10 nm. For these studies, heterostructures without the CoFeB layer were used. (C and D) Sb concentration (x) dependence of the damping-like spin Hall efficiency ξDL (left axis), the SHC σSH (right axis) (C), and the field-like spin Hall efficiency ξFL (D) for 10 Bi1−xSbx/2 CoFeB heterostructures. All data were collected at 300 K.

ξDL, σSH, and ξFL as a function of x for Bi1−xSbx/2 CoFeB heterostructures are presented in Fig. 3 (C and D). ξDL and ξFL increase with increasing Bi concentration, reaching a maximum of ξDL ∼ 1.2 and ξFL ∼ 0.41 for structures with x ∼ 0.17, a composition for which bulk Bi1−xSbx is commonly classified as a topological insulator. However, we emphasize that the Bi1−xSbx thickness dependence in the previous section and the facet dependence of SHE in the next paragraph both suggest the bulk origin of the SHE. The x dependence of σSH exhibits similar trend with that of ξDL: We find a plateau of for x < 0.35. This x dependence of σSH is in very good agreement with that obtained from tight binding calculations (38), suggesting the dominance of the intrinsic contribution over that of the extrinsic skew scattering and side-jump contributions for the observed SHE in Bi1−xSbx.

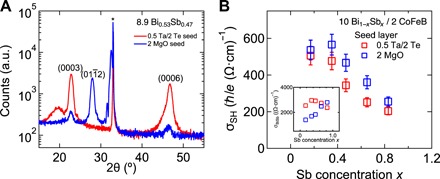

We have also varied the seed layer of the Bi1−xSbx layer to study the facet-dependent SHE. Figure 4A shows the XRD spectra of 8.9-nm-thick Bi0.53Sb0.47 films grown on different seed layers, showing that the orientation of Bi0.53Sb0.47 nanocrystallites can be tuned from being practically random (Bi0.53Sb0.47 on 0.5 Ta seed; see Fig. 1A) to strongly (0003) oriented (0.5 Ta/2 Te seed) or strongly () oriented (2 MgO seed). The Sb concentration (x) dependence of the longitudinal conductivity σBiSb and the SHC of Bi1−xSbx are shown in Fig. 4B. As evident from the inset of Fig. 4B, the difference in the texture causes large changes in σBiSb, particularly at smaller x. However, the x dependence of SHC hardly changes upon varying the Bi1−xSbx texture and σBiSb. We thus infer that topological surface states, which are intimately related to the Bi1−xSbx facets (34), are therefore unlikely to be the primary source of the observed SHE. The robustness of SHC against σBiSb further consolidates our suggestion that the intrinsic mechanism can account for the observed SHE.

Fig. 4. Facet dependence of σSH.

(A) XRD spectra for 8.9 Bi0.53Sb0.47 grown on 0.5 Ta/2 Te (red) and 2 MgO (blue) seed layers. Heterostructures without the CoFeB layer were used. (B) Sb concentration (x) dependence of SHC σSH for 10 Bi1−xSbx/2 CoFeB heterostructures with the two seed layers described in (A). The inset shows the x dependence of σBiSb. The measurement temperature is 300 K.

Temperature dependence of σSH

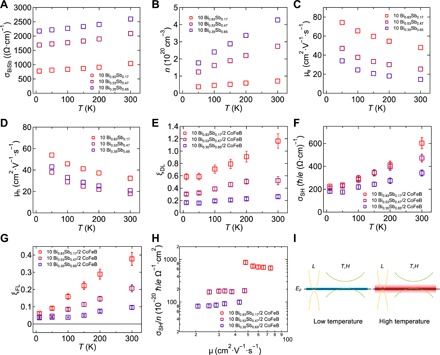

Last, we examine the temperature dependence of the transport properties for Bi1−xSbx/CoFeB heterostructures with selected x (x ∼ 0.17, 0.47, and 0.65). Here, the seed layer of Bi1−xSbx is 0.5 nm Ta. Figure 5A shows σBiSb as a function of the measurement temperature. We find that Bi1−xSbx has weak and positive temperature coefficient of the conductance, which is typical for a semiconductor. To obtain the variation of the carrier concentration and mobility of Bi1−xSbx, we measured temperature dependence of the longitudinal MR ratio ((Rxx(Hz) − Rxx(Hz = 0))/Rxx(Hz = 0)) and Rxy against Hz. Within the framework of a two-band model (52), we define nh (ne) as the effective hole (electron) concentration of Bi1−xSbx, with an effective mobility μh (μe). Assuming equal population of the two carriers (nh = ne = n) (51), we evaluate these parameters for temperatures ranging from 50 to 300 K, where the MR ratio and Rxy are quadratic and linear, respectively, with Hz up to 8 T (see the Supplementary Materials for details of two-band model analysis). The temperature dependence of the carrier concentration and the mobility are summarized in Fig. 5 (B to D). The carrier concentration increases with increasing temperature, which we infer is caused by the thermal broadening of the Fermi-Dirac distribution. In contrast, μh and μe both decrease with increasing temperature, obeying a power law that scales with ∼T−0.5. These results indicate a competition between the impurity-mediated scattering (∝T1.5) and electron-phonon scattering (∝T−1.5), with the latter being more dominant. Compared to the carrier concentration and mobility of the majority carrier for bulk single-crystal Bi (n ∼ 4.6 × 1017 cm−3; μe ∼ 6 × 105 cm2 V−1 s−1) (53) and Sb (n ∼ 3.9 × 1019 cm−3; μh ∼ 2 × 104 cm2 V−1 s−1) (54) at 77 K, n values of the Bi1−xSbx films studied here are one to two orders of magnitude higher, while μ values are orders of magnitude lower. These are expected for sputtered polycrystalline thin films that contain significantly higher defect density compared to that of the bulk samples (36).

Fig. 5. Temperature dependence of carrier transport and σSH.

(A to D) Temperature dependence of the conductivity σBiSb (A), the effective carrier concentration n (B), the electron mobility μe (C), and the hole mobility μd (D) for 10 Bi1−xSbx. Heterostructures without the CoFeB layer were used. (E to G) Temperature dependence of the damping-like spin Hall efficiency ξDL (E), the SHC σSH (F), and the field-like spin Hall efficiency ξFL (G) for 10 Bi1−xSbx/2 CoFeB heterostructures. (H) σSH/n as a function of the majority carrier mobility (μe for x = 0.17 and 0.47, and μh for x = 0.65) for 10 Bi1−xSbx/2 CoFeB heterostructures. (I) Schematic illustration of the band structures of the Bi-rich Bi1−xSbx alloy with thermal broadening at low and high temperatures.

The temperature dependence of ξDL, σSH, and ξFL for 10 Bi1−xSbx/2 CoFeB heterostructures is plotted in Fig. 5, E to G, respectively. Unexpectedly, all these quantities strongly enhance upon increasing the temperature from 10 K to room temperature (300 K), suggesting that this enhancement is a rather generic feature for the Bi1−xSbx alloy. Notably, for Bi0.83Sb0.17, up to a threefold (twofold) enhancement is observed for σSH (ξDL) over the investigated temperature interval. While similar increase of ξFL with increasing temperature was previously reported in HM/FM heterostructures (49, 55), this strong enhancement of technologically important ξDL and σSH with increasing temperature has not been observed in metallic systems. We have also studied the temperature dependence of σSH for thinner Bi1−xSbx films (5.6 Bi0.53Sb0.47/2 CoFeB). We find similar temperature dependence of σSH compared to that shown in Fig. 5E, which suggests that the temperature dependence of ξDL, σSH, and ξFL is not due to a temperature-dependent spin diffusion length of Bi1−xSbx. We have also verified that the CoFeB saturation magnetization hardly changes within this temperature range (see the Supplementary Materials), reassuring that the change of ξDL and ξFL with temperature is caused by the modulation of the injected spin current.

DISCUSSION

Within the Drude model, the longitudinal conductivity σBiSb is proportional to the carrier concentration n and the mobility μ. μ is proportional to the relaxation time τ because μ = eτ/m*, where m* is the effective mass. On varying the temperature, contribution from n surpasses that of μ in Bi1−xSbx, resulting in a positive temperature coefficient of the conductance, as shown in Fig. 5A. For the SHC, by definition, the relaxation time dependence of σSH provides a measure of the mechanism of the SHE: σSH ∼ τ1 for the extrinsic skew scattering and σSH ∼ τ0 when the intrinsic or side-jump mechanism dominates (5). With regard to the relation between σSH and n, the intrinsic contribution should scale with n if the analogy with the anomalous Hall conductivity applies (2). Calculations suggest that similar scaling between σSH and n holds for the extrinsic mechanisms (56). We may thus take the ratio σSH/n to eliminate the effect of n on the temperature dependence of σSH . We expect σSH/n is proportional to μ1 for the extrinsic skew scattering mechanism and is a constant for the intrinsic/side-jump mechanism. Figure 5H shows σSH/n as a function of the mobility μ (here, the mobility of the majority carrier is used, i.e., μe for x = 0.17 and 0.47, and μh for x = 0.65). We find a relatively weak mobility dependence of σSH/n for all alloy compositions studied. The slope of σSH/n versus μ tends to increase as the Sb concentration increases. These results indicate that the extrinsic skew scattering contribution is relatively weak for Bi-rich alloys with large intrinsic SHE, but this contribution becomes non-negligible (but still smaller than the intrinsic one) with increasing x (and σBiSb). Although this is reminiscent of the crossover from intrinsic to extrinsic SHE for metallic Pt upon tuning the resistivity of the metal (57), we note that σBiSb at the crossover is one to two orders of magnitude lower than that of Pt. Alternatively, we consider that this crossover is a consequence of the band structure modification induced by Sb doping. As shown in the schematic band structure of Fig. 5I, the transport in the Bi-rich Bi1−xSbx alloy is dominated by the Dirac-like electrons at the L point in the momentum space (33, 34, 37, 50, 51). Upon substituting Bi with Sb, holes from the T and H points with quadratic-like dispersion become increasingly important for the conduction, as shown by the x dependence of RH in Fig. 3B. Our experimental results indicate that Dirac-like L electrons, in contrast to holes in T and H pockets with quadratic dispersion, are key for achieving large intrinsic SHE in Bi1−xSbx. We thus consider that the large enhancement of SHC with temperature is caused by the increased number of L electrons due to thermal broadening of the Fermi-Dirac distribution.

Referring to the relation between the carrier density, mobility, and conductivity that derives from the Drude model, σSH/n can be regarded as the equivalent carrier mobility of transverse spin current. To provide reference of the equivalent mobility, we estimate σSH/n of a typical transition metal, Pt, which has the highest intrinsic SHC reported thus far [ at 0 K (58)]. Assuming the carrier density n of Pt is of the order of 1022 cm−3, we obtain . This is more than an order of magnitude smaller than that of Bi0.83SB0.17 evaluated at room temperature . The difference is also remarkable within the Bi1−xSbx alloy. If we compare Bi0.83Sb0.17 with Bi0.35Sb0.65, although the SHC σSH differs by a factor of 2, the equivalent mobility σSH/n is larger for the former by nearly one order of magnitude. These results demonstrate the exceptionally high spin current generation efficiency and mobility of the Dirac-like L electrons in Bi-rich Bi1−xSbx alloys compared to the majority holes in Sb-rich Bi1−xSbx and the predominantly s-like conduction electrons in Pt.

In summary, we have studied the SOT in sputter-deposited Bi1−xSbx/CoFeB heterostructures. The SHC of Bi1−xSbx increases with increasing thickness until saturation and is facet independent. These results suggest a dominant contribution from the bulk of the alloy: The effect of the topological surface states, if any, is not evident. The SHC is the largest with Bi-rich composition and decreases with increasing Sb concentration. This trend is in accordance with the intrinsic SHE of Bi1−xSbx predicted using tight binding calculations. The SHC and the damping-like spin Hall efficiency increase with increasing temperature. For example, the damping-like spin Hall efficiency of Bi0.83Sb0.17 exhibits a twofold enhancement from 5 K to room temperature, reaching ξDL ∼ 1.2. We infer that the thermally excited population of the Dirac-like electrons in the L valley of the narrow gap Bi1−xSbx is responsible for the temperature-dependent SOT. These results show that the Dirac-like electrons in Bi-rich Bi1−xSbx alloys are extremely effective in generating spin current, and their equivalent spin current mobility is more than an order of magnitude larger than that of typical transition metals with strong spin-orbit coupling. The very high spin Hall efficiency of Bi-rich Bi1−xSbx makes this material an outstanding candidate for applications involving spin current generation and detection at elevated temperatures. In addition, the lower carrier concentration and therefore a smaller electric field screening length in Bi1−xSbx compared to the common HMs allow efficient electric field control of SOT, thus paving a route to multifunctional spin-orbitronic devices that are sensitive to external stimuli such as heat and electric field.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation and characterization

All samples were grown at ambient temperature by magnetron sputtering on Si substrates (10 × 10 mm2) coated with 100-nm-thick thermally oxidized Si layer. AFM was used to characterize the roughness of the surface. θ − 2θ XRD spectra were obtained using a Cu Kα source in parallel beam configuration and with a graphite monochromator on the detector side. The saturation magnetization and the magnetic dead layer thickness of the CoFeB layer in the heterostructures were determined by hysteresis loop measurements using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM). AFM, XRD, and VSM studies were performed using unpatterned constant thickness films. HAADF-STEM analysis of cross-sectioned samples was performed using a FEI Titan G2 80-200 TEM with a probe-forming spherical aberration corrector operated at 200 kV. The samples were cross-sectioned from a plain film into thin lamellae by focused ion beam lift-out technique using FEI Helios G4 UX. Hall bars for the transport measurements were pattered from the films using optical lithography and Ar ion etching. The width w and the distance between the two longitudinal voltage probes L are 10 and 25 μm, respectively. Contact pads to the Hall bars, 10 Ta/100 Au (thickness in nanometers), were formed using a standard lift-off process.

SOT measurements

We treat the CoFeB magnetization as a single domain magnet with a magnetization vector M lying in the film plane (xy plane) at equilibrium. The external magnetic field Hext is applied along the film plane with an angle φH with respect to the x axis. We assume that the in-plane magnetic anisotropy of the CoFeB layer is negligible compared to the magnitude of Hext. Thus, the angle φ between M and the x axis is assumed be equal to φH.

When current is passed along x, electrons with their spin direction parallel to y diffuses into the CoFeB layer via the SHE. The impinging spin current exerts spin-transfer torque (or often referred to as the SOT) on the CoFeB magnetization. The torque can be decomposed into two components, the damping-like and field-like torques: The equivalent effective fields are defined as HDL and HFL, respectively. Together with the Oersted field HOe, HDL and HFL cause tilting of the CoFeB layer magnetization. When an AC (amplitude I0, frequency ω/2π) is applied to the heterostructure, current-induced oscillation of M leads to Hall voltage oscillation via anomalous Hall effect (AHE) and planar Hall effect (PHE). The first harmonic (fundamental) voltage V1ω represents the magnetization direction at equilibrium, and the out-of-phase second harmonic voltage V2ω provides information on the current-induced effective fields acting on the magnetization. We define (i = 1, 2) to represent the harmonic signals.

Contributions to R2ω include five terms. RDL, RFL, and ROe, which reflect changes in R2ω caused by HDL, HFL, and HOe, respectively, decay with increasing Hext. RDL is proportional to the x component of the magnetization (cos φ), whereas RFL + ROe scales with cos 2 φ cos φ due to the combined influences of AHE and PHE (40, 41). Current-induced Joule heating and the different thermal conductivity of the substrate and air can lead to an out-of-plane temperature gradient (41) across the heterostructure. With the temperature gradient, the ANE of CoFeB and the collective action of the SSE (59) in CoFeB followed by the ISHE in Bi1−xSbx result in a contribution (Rconst) that does not depend on the size of Hext. Applying a field orthogonal to the out-of-plane temperature gradient produces the last term, RONE, due to ONE (43). RONE scales linearly with Hext. ONE of CoFeB is negligible compared to that of Bi1−xSbx due to the difference in the carrier density. Both Rconst and RONE scale with cos φ.

Putting together these contributions (and assuming φ ∼ φH), R2ω reads

| (1) |

where RAHE is the anomalous Hall resistance, RPHE is the planar Hall resistance, HK is the out-of-plane anisotropy field, is the ONE coefficient of Bi1−xSbx, and α is a coefficient that reflects the size of ANE and the combined action of SSE and ISHE. The distinct Hext and φH dependence of R2ω for these contributions allows unambiguous separation of each term from the raw R2ω signal. We first decompose R2ω into two contributions of different φH dependence, i.e., cos φH and cos 2φH cos φH, and define the prefactors of these two parts as A and B, respectively

| (2) |

| (3) |

Two parameters VONE ≡ wΔT and Vconst ≡ αwΔT are defined to describe the thermoelectric contributions. The Hext dependence of A and B is then fitted based on Eqs. 2 and 3, respectively.

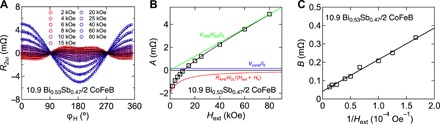

Representative R2ω as a function of φH obtained using different Hext for the 10.9 Bi0.53Sb0.47/2 CoFeB heterostructure is shown in Fig. 6A. Solid lines in the figure are fits to the data using Eq. 1. See the Supplementary Materials for the φH dependence of R1ω. All data shown in this article are collected using ω/2π = 17.5 Hz. The current amplitude is typically set to ∼1.5 mArms, which corresponds to a current density in the Bi1−xSbx layer of ∼1 × 1010 A/m2. We find that R2ω scales linearly with current. The Hext dependence of one of the fitting parameters A is shown in Fig. 6B. The best fit to A against Hext is shown by the solid black line. The colored lines represent decomposition of each contribution following Eq. 2 (see the Supplementary Materials for determination of RAHE and HK). In the small Hext range, RDL term (red line) dominates, whereas at larger field, A changes sign and is eventually dominated by RONE (green line). B is plotted against 1/Hext in Fig. 6C, with the black solid line showing the best linear fit to the data using Eq. 3. We extract HDL, HFL + HOe, VONE, and Vconst from the two fits. We find Vconst and VONE to be proportional to the square of the current flowing within the CoFeB and Bi1−xSbx layer, respectively. These results confirm the thermoelectric origin of these contributions and the validity of the interpretation of R2ω.

Fig. 6. Representative second harmonic Hall resistances.

(A) Field angle φH dependence of the second harmonic Hall resistance R2ω for the 10.9 Bi0.53Sb0.47/2 CoFeB heterostructure obtained using different Hext measured at 300 K. (B) Hext dependence of the fitting parameter A. (C) 1/Hext dependence of the fitting parameter B. In (B) and (C), the colored lines show contributions from each component described in Eqs. 2 and 3; the black solid line shows the sum of all contributions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Fuseya, H. Kohno, and G. Qu for helpful discussions. Funding: This work was partly supported by JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (grant no. 15H05702), JST CREST (grant no. JPMJCR19T3), the Casio Science Foundation, and the Center for Spintronics Research Network (CSRN). Z.C. acknowledges financial support from Materials Education program for the future leaders in Research, Industry, and Technology (MERIT). Y.-C.L. is supported by JSPS International Fellowship for Research in Japan (grant no. JP17F17064). Author contributions: Y.-C.L., Z.C., and M.H. planned the study. Z.C. and Y.-C.L. grew the samples, designed the experimental setup, performed electrical measurements, and carried out data analysis. Y.-C.L. performed structural characterization (AFM and XRD), fabricated Hall bar devices, and modeled the system transport properties. X.X., T.O., and K.H. carried out TEM imaging. Z.C. and Y.-C.L. wrote the manuscript with input from M.H. All authors contributed to the discussion of results and commented on the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/10/eaay2324/DC1

Section S1. STEM results of films

Section S2. Magnetic properties of BiSb/CoFeB

Section S3. Anomalous Hall resistance and anisotropy field

Section S4. First harmonic Hall resistance of BiSb/CoFeB

Section S5. Two-band model analysis of BiSb

Section S6. Evaluation of the SOT analysis protocol

Section S7. The efficiency of BiSb SOT

Fig. S1. HAADF-STEM and EDS mapping.

Fig. S2. Saturation magnetization and magnetic dead layer thickness.

Fig. S3. Anomalous Hall resistance and anisotropy field.

Fig. S4. First harmonic Hall resistance.

Fig. S5. Temperature dependence of magnetotransport properties of Bi1−xSbx.

Fig. S6. SOT measurements of a standard sample: Pt/CoFeB.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Murakami S., Nagaosa N., Zhang S.-C., Dissipationless quantum spin current at room temperature. Science 301, 1348–1351 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee W.-L., Watauchi S., Miller V. L., Cava R. J., Ong N. P., Dissipationless anomalous Hall current in the ferromagnetic spinel CuCr2Se4−xBrx. Science 303, 1647–1649 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyakonov M. I., Perel V. I., Possibility of orienting electron spins with current. JETP Lett. USSR 13, 467 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsch J. E., Spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1834–1837 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinova J., Valenzuela S. O., Wunderlich J., Back C. H., Jungwirth T., Spin Hall effects. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1213–1260 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bychkov Y. A., Rashba E. I., Properties of a 2d electron-gas with lifted spectral degeneracy. JETP Lett. 39, 78–81 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edelstein V. M., Spin polarization of conduction electrons induced by electric current in two-dimensional asymmetric electron systems. Solid State Commun. 73, 233–235 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manchon A., Koo H. C., Nitta J., Frolov S. M., Duine R. A., New perspectives for Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Nat. Mater. 14, 871–882 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu L., Pai C.-F., Li Y., Tseng H. W., Ralph D. C., Buhrman R. A., Spin-torque switching with the giant spin Hall effect of tantalum. Science 336, 555–558 (2012a). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miron I. M., Gaudin G., Auffret S., Rodmacq B., Schuhl A., Pizzini S., Vogel J., Gambardella P., Current-driven spin torque induced by the Rashba effect in a ferromagnetic metal layer. Nat. Mater. 9, 230–234 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J., Sinha J., Hayashi M., Yamanouchi M., Fukami S., Suzuki T., Mitani S., Ohno H., Layer thickness dependence of the current induced effective field vector in Ta∣CoFeB∣MgO. Nat. Mater. 12, 240–245 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garello K., Miron I. M., Avci C. O., Freimuth F., Mokrousov Y., Blugel S., Auffret S., Boulle O., Gaudin G., Gambardella P., Symmetry and magnitude of spin-orbit torques in ferromagnetic heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 587–593 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miron I. M., Garello K., Gaudin G., Zermatten P.-J., Costache M. V., Auffret S., Bandiera S., Rodmacq B., Schuhl A., Gambardella P., Perpendicular switching of a single ferromagnetic layer induced by in-plane current injection. Nature 476, 189–193 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emori S., Bauer U., Ahn S.-M., Martinez E., Beach G. S. D., Current-driven dynamics of chiral ferromagnetic domain walls. Nat. Mater. 12, 611–616 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryu K.-S., Thomas L., Yang S.-H., Parkin S., Chiral spin torque at magnetic domain walls. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 527–533 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo S., Litzius K., Kruger B., Im M.-Y., Caretta L., Richter K., Mann M., Krone A., Reeve R. M., Weigand M., Agrawal P., Lemesh I., Mawass M.-A., Fischer P., Kläui M., Beach G. S. D., Observation of room-temperature magnetic skyrmions and their current-driven dynamics in ultrathin metallic ferromagnets. Nat. Mater. 15, 501–506 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakayama H., Althammer M., Chen Y.-T., Uchida K., Kajiwara Y., Kikuchi D., Ohtani T., Geprags S., Opel M., Takahashi S., Gross R., Bauer G. E. W., Goennenwein S. T. B., Saitoh E., Spin Hall magnetoresistance induced by a nonequilibrium proximity effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 206601 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y.-T., Takahashi S., Nakayama H., Althammer M., Goennenwein S. T. B., Saitoh E., Bauer G. E. W., Theory of spin Hall magnetoresistance. Phys. Rev. B 87, 144411 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rojas-Sanchez J.-C., Reyren N., Laczkowski P., Savero W., Attane J. P., Deranlot C., Jamet M., George J. M., Vila L., Jaffres H., Spin pumping and inverse spin Hall effect in platinum: The essential role of spin-memory loss at metallic interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 106602 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang W., Han W., Jiang X., Yang S.-H., Parkin S. S. P., Role of transparency of platinum-ferromagnet interfaces in determining the intrinsic magnitude of the spin Hall effect. Nat. Phys. 11, 496–502 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasan M. Z., Kane C. L., Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Y., Zhang Y., Felser C., Yan B., Strong intrinsic spin Hall effect in the TaAs family of Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 146403 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mellnik A. R., Lee J. S., Richardella A., Grab J. L., Mintun P. J., Fischer M. H., Vaezi A., Manchon A., Kim E. A., Samarth N., Ralph D. C., Spin-transfer torque generated by a topological insulator. Nature 511, 449–451 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan Y. B., Upadhyaya P., Kou X. F., Lang M. R., Takei S., Wang Z., Tang J., He L., Chang L.-T., Montazeri M., Yu G. Q., Jiang W. J., Nie T. X., Schwartz R. N., Tserkovnyak Y., Wang K. L., Magnetization switching through giant spin-orbit torque in a magnetically doped topological insulator heterostructure. Nat. Mater. 13, 699–704 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jamali M., Lee J. S., Jeong J. S., Mahfouzi F., Lv Y., Zhao Z. Y., Nikolic B. K., Mkhoyan K. A., Samarth N., Wang J.-P., Giant spin pumping and inverse spin Hall effect in the presence of surface and bulk spin-orbit coupling of topological insulator Bi2se3. Nano Lett. 15, 7126–7132 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kondou K., Yoshimi R., Tsukazaki A., Fukuma Y., Matsuno J., Takahashi K. S., Kawasaki M., Tokura Y., Otani Y., Fermi-level-dependent charge-to-spin current conversion by Dirac surface states of topological insulators. Nat. Phys. 12, 1027–1031 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yasuda K., Tsukazaki A., Yoshimi R., Kondou K., Takahashi K. S., Otani Y., Kawasaki M., Tokura Y., Current-nonlinear Hall effect and spin-orbit torque magnetization switching in a magnetic topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 137204 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y., Zhu D. P., Wu Y., Yang Y. M., Yu J. W., Ramaswamy R., Mishra R., Shi S. Y., Elyasi M., Teo K. L., Wu Y. H., Yang H., Room temperature magnetization switching in topological insulator-ferromagnet heterostructures by spin-orbit torques. Nat. Commun. 8, 1364 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han J. H., Richardella A., Siddiqui S. A., Finley J., Samarth N., Liu L. Q., Room-temperature spin-orbit torque switching induced by a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 077702 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahendra D. C., Grassi R., Chen J. Y., Jamali M., Hickey D. R., Zhang D. L., Zhao Z. Y., Li H. S., Quarterman P., Lv Y., Li M., Manchon A., Mkhoyan K. A., Low T., Wang J. P., Room-temperature high spin-orbit torque due to quantum confinement in sputtered BixSe(1-x) films. Nat. Mater. 17, 800–807 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khang N. H. D., Ueda Y., Hai P. N., A conductive topological insulator with large spin Hall effect for ultralow power spin-orbit torque switching. Nat. Mater. 17, 808–813 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y. F., Ma Q. L., Huang S. X., Chien C. L., Thin films of topological kondo insulator candidate smb6: Strong spin-orbit torque without exclusive surface conduction. Sci. Adv. 4, eaap8294 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y., Allen R. E., Electronic-structure of the semimetals Bi and Sb. Phy. Rev. B 52, 1566–1577 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teo J. C. Y., Fu L., Kane C. L., Surface states and topological invariants in three-dimensional topological insulators: Application to Bi1–xSbx. Phys. Rev. B 78, 045426 (2008a). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou D. Z., Qiu Z., Harii K., Kajiwara Y., Uchida K., Fujikawa Y., Nakayama H., Yoshino T., An T., Ando K., Jin X. F., Saitoh E., Interface induced inverse spin Hall effect in bismuth/permalloy bilayer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 042403 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emoto H., Ando Y., Eguchi G., Ohshima R., Shikoh E., Fuseya Y., Shinjo T., Shiraishi M., Transport and spin conversion of multicarriers in semimetal bismuth. Phys. Rev. B 93, 174428 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuseya Y., Ogata M., Fukuyama H., Spin-Hall effect and diamagnetism of Dirac electrons. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 81, 093704 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sahin C., Flatté M. E., Tunable giant spin Hall conductivities in a strong spin-orbit semimetal: Bi(1-x)Sb(x). Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 107201 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukazawa T., Kohno H., Fujimoto J., Intrinsic and extrinsic spin Hall effects of Dirac electrons. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 86, 094704 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawaguchi M., Shimamura K., Fukami S., Matsukura F., Ohno H., Moriyama T., Chiba D., Ono T., Current-induced effective fields detected by magnetotrasport measurements. Appl. Phys. Express 6, 113002 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Avci C. O., Garello K., Gabureac M., Ghosh A., Fuhrer A., Alvarado S. F., Gambardella P., Interplay of spin-orbit torque and thermoelectric effects in ferromagnet/normal-metal bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 90, 224427 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lau Y.-C., Hayashi M., Spin torque efficiency of Ta, W, and Pt in metallic bilayers evaluated by harmonic Hall and spin Hall magnetoresistance measurements. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 56, 0802b5 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roschewsky N., Walker E. S., Gowtham P., Muschinske S., Hellman F., Bank S. R., Salahuddin S., Spin-orbit torque and nernst effect in Bi-Sb/Co heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 99, 195103 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiler M., Althammer M., Schreier M., Lotze J., Pernpeintner M., Meyer S., Huebl H., Gross R., Kamra A., Xiao J., Chen Y.-T., Jiao H., Bauer G. E. W., Goennenwein S. T. B., Experimental test of the spin mixing interface conductivity concept. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 176601 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffmann A., Spin Hall effects in metals. IEEE Trans. Magn. 49, 5172–5193 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shiomi Y., Nomura K., Kajiwara Y., Eto K., Novak M., Segawa K., Ando Y., Saitoh E., Spin-electricity conversion induced by spin injection into topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 196601 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu L. Q., Pai C.-F., Ralph D. C., Buhrman R. A., Magnetic oscillations driven by the spin Hall effect in 3-terminal magnetic tunnel junction devices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 186602 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shao Q. M., Yu G. Q., Lan Y.-W., Shi Y. M., Li M. Y., Zheng C., Zhu X. D., Li L. J., Amiri P. K., Wang K. L., Strong Rashba-Edelstein effect-induced spin-orbit torques in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenide/ferromagnet bilayers. Nano Lett. 16, 7514–7520 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ou Y., Pai C.-F., Shi S., Ralph D. C., Buhrman R. A., Origin of fieldlike spin-orbit torques in heavy metal/ferromagnet/oxide thin film heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 94, 140414 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yim W. M., Amith A., Bi-Sb alloys for magneto-thermoelectric and thermomagnetic cooling. Solid-State Electron. 15, 1141–1165 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lenoir B., Scherrer H., Caillat T., An overview of recent developments for BiSb alloys. Semiconduc. Semimet. 69, 101–137 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu Z. W., Fauque B., Behnia K., Fuseya Y., Magnetoresistance and valley degree of freedom in bulk bismuth. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 30, 313001 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Michenaud J.-P., Issi J.-P., Electron and hole transport in bismuth. J. Phys. Part C Solid State Phys. 5, 3061–3072 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oktu O., Saunders G. A., Galvanomagnetic properties of single-crystal antimony between 77 °K and 273 °K. Proc. Phys. Soc. London 91, 156–168 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim J., Sinha J., Mitani S., Hayashi M., Takahashi S., Maekawa S., Yamanouchi M., Ohno H., Anomalous temperature dependence of current-induced torques in CoFeB/MgO heterostructures with ta-based underlayers. Phys. Rev. B 89, 174424 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tse W. K., Das Sarma S., Spin Hall effect in doped semiconductor structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 056601 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sagasta E., Omori Y., Isasa M., Gradhand M., Hueso L. E., Niimi Y., Otani Y., Casanova F., Tuning the spin Hall effect of Pt from the moderately dirty to the superclean regime. Phys. Rev. B 94, 060412 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo G. Y., Murakami S., Chen T.-W., Nagaosa N., Intrinsic spin Hall effect in platinum: First-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096401 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Uchida K., Takahashi S., Harii K., Ieda J., Koshibae W., Ando K., Maekawa S., Saitoh E., Observation of the spin seebeck effect. Nature 455, 778–781 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu X. D., Mukaiyama K., Kasai S., Ohkubo T., Hono K., Impact of boron diffusion at MgO grain boundaries on magneto transport properties of MgO/CoFeB/W magnetic tunnel junctions. Acta Mater. 161, 360–366 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ikeda S., Miura K., Yamamoto H., Mizunuma K., Gan H. D., Endo M., Kanai S., Hayakawa J., Matsukura F., Ohno H., A perpendicular-anisotropy cofeb-mgo magnetic tunnel junction. Nat. Mater. 9, 721–724 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sinha J., Hayashi M., Kellock A. J., Fukami S., Yamanouchi M., Sato M., Ikeda S., Mitani S., Yang S. H., Parkin S. S. P., Ohno H., Enhanced interface perpendicular magnetic anisotropy in Ta∣CoFeB∣MgO using nitrogen doped Ta underlayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 242405 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim J., Sheng P., Takahashi S., Mitani S., Hayashi M., Spin Hall magnetoresistance in metallic bilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 097201 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cho S., Baek S.-H. C., Lee K. D., Jo Y., Park B. G., Large spin Hall magnetoresistance and its correlation to the spin-orbit torque in W/CoFeB/MgO structures. Sci. Rep. 5, 14668 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ali M. N., Xiong J., Flynn S., Tao J., Gibson Q. D., Schoop L. M., Liang T., Haldolaarachchige N., Hirschberger M., Ong N. P., Cava R. J., Large, non-saturating magnetoresistance in WTe2. Nature 514, 205–208 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang Y., Deorani P., Qiu X. P., Kwon J. H., Yang H. S., Determination of intrinsic spin Hall angle in pt. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 152412 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee K.-S., Lee S.-W., Min B.-C., Lee K.-J., Thermally activated switching of perpendicular magnet by spin-orbit spin torque. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 072413 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pai C.-F., Liu L. Q., Li Y., Tseng H. W., Ralph D. C., Buhrman R. A., Spin transfer torque devices utilizing the giant spin Hall effect of tungsten. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 122404 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 69.K. Garello, F. Yasin, S. Couet, L. Souriau, J. Swerts, S. Rao, S. Van Beek, W. Kim, E. Liu, S. Kundu, D. Tsvetanova, K. Croes, N. Jossart, E. Grimaldi, M. Baumgartner, D. Crotti, A. Fumemont, P. Gambardella, G. S. Kar, SOT-MRAM 300mm integration for low power and ultrafast embedded memories, in 2018 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Circuits (IEEE, 2018), pp. 81–82. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/10/eaay2324/DC1

Section S1. STEM results of films

Section S2. Magnetic properties of BiSb/CoFeB

Section S3. Anomalous Hall resistance and anisotropy field

Section S4. First harmonic Hall resistance of BiSb/CoFeB

Section S5. Two-band model analysis of BiSb

Section S6. Evaluation of the SOT analysis protocol

Section S7. The efficiency of BiSb SOT

Fig. S1. HAADF-STEM and EDS mapping.

Fig. S2. Saturation magnetization and magnetic dead layer thickness.

Fig. S3. Anomalous Hall resistance and anisotropy field.

Fig. S4. First harmonic Hall resistance.

Fig. S5. Temperature dependence of magnetotransport properties of Bi1−xSbx.

Fig. S6. SOT measurements of a standard sample: Pt/CoFeB.