Key Points

Question

What are the clinical characteristics and vaping exposures among patients hospitalized with e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) in California?

Findings

Of 160 patients included in this case series, 74% were younger than 35 years, 46% required admission to intensive care units, and 29% required mechanical ventilation. Of 86 patients interviewed, 83% reported using tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing products, most of which were acquired from informal sources; vitamin E or vitamin E acetate was present in 84% of THC-containing products tested from 24 patients.

Meaning

Use of THC-containing products and vitamin E acetate appear to be associated with the EVALI outbreak, but additional investigation is needed to determine the cause(s).

Abstract

Importance

Since August 2019, more than 2700 patients have been hospitalized with e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) across the United States. This report describes the outbreak in California, a state with one of the highest case counts and with a legal adult-use (recreational) cannabis market.

Objective

To present clinical characteristics and vaping product exposures of patients with EVALI in California.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Case series describing epidemiologic and laboratory data from 160 hospitalized patients with EVALI reported to the California Department of Public Health by local health departments, who received reports from treating clinicians, from August 7 through November 8, 2019.

Exposures

Standardized patient interviews were conducted to assess vaping products used, frequency of use, and method of product acquisition. Vaping products provided by a subset of patients were tested for active ingredients and other substances.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics, level of care, and outcomes of hospitalization were obtained from medical record review.

Results

Among 160 patients with EVALI, 99 (62%) were male, and the median age was 27 years (range, 14-70 years). Of 156 patients with data available, 71 (46%) were admitted to an intensive care unit, and 46 (29%) required mechanical ventilation. Four in-hospital deaths occurred. Of 86 patients interviewed, 71 (83%) reported vaping tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing products, 36 (43%) cannabidiol (CBD)-containing products, and 39 (47%) nicotine-containing products. Sixty-five of 87 (75%) THC-containing products were reported as obtained from informal sources, such as friends, acquaintances, or unlicensed retailers. Of 87 vaping products tested from 24 patients, 49 (56%) contained THC. Vitamin E or vitamin E acetate was found in 41 (84%) of the THC-containing products and no nicotine products.

Conclusions and Relevance

Patients’ clinical outcomes and vaping behaviors, including predominant use of THC-containing products from informal sources, are similar to those reported by other states, despite California’s legal recreational cannabis market. While most THC products tested contained vitamin E or vitamin E acetate, other underlying cause(s) of injury remain possible. The California Department of Public Health recommends that individuals refrain from using any vaping or e-cigarette products, particularly THC-containing products from informal sources, while this investigation is ongoing.

This case series presents the clinical characteristics and vaping product exposures of 160 patients with e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury in California.

Introduction

Vaping, or electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use, has grown substantially in the United States in recent years, particularly among youth.1,2 Vaping devices heat liquids to generate an aerosol that is inhaled into the lungs, and liquids can contain active ingredients such as nicotine; cannabis-derived compounds including tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive component of cannabis, and cannabidiol (CBD); as well as flavorings and other chemicals.3 Despite increases in vaping among youth, the contents of vaping products are largely unregulated nationally. Recreational cannabis use, including the sale of cannabis-containing vaping products, is legal in California for adults 21 years and older under the Adult Use of Marijuana Act (Proposition 64), though local jurisdictions can prohibit or regulate cannabis sales.

On August 7, 2019, a local health department notified the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) of a cluster of 7 previously healthy individuals who were hospitalized with severe lung injury without evidence of infection. All reported a history of vaping. These reported cases closely resembled those described in a Wisconsin alert issued on July 25, 2019.4 On August 9, 2019, CDPH issued a statewide health alert to clinicians and local health departments requesting reports of any suspected cases of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI).

As of January 2020, more than 2700 EVALI cases have been reported in all 50 states.5 Investigations in other states and nationally have described EVALI and highlighted the role of THC-containing products from informal sources6,7,8; however, findings from a state with a legal adult-use cannabis market have not previously been reported. This report describes demographics, clinical characteristics, and vaping exposures of 160 patients reported to CDPH from August 7 through November 8, 2019, and initial results of laboratory testing of vaping products used by case patients to help direct the public health response to the outbreak and guide clinicians caring for patients with EVALI.

Methods

Case Investigation

Clinicians or hospitals reported suspected cases of EVALI to local health departments, who then reported them to CDPH. CDPH clinicians classified cases using a case definition based on the one established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which requires vaping in the past 90 days, findings of infiltrates or opacities on chest imaging, and absence of other plausible clinical explanations for illness, including infectious causes,6 with the additional requirement in California of hospitalization (see eFigure in the Supplement for full case definition). The California EVALI case definition was restricted to hospitalized patients in order to improve specificity while capturing the most severe cases. Although CDC’s case definition does not include this requirement, 95% of case patients reported nationally have been hospitalized, and since November 2019, CDC has only accepted reports of hospitalized cases.5

From August 7 through November 8, 2019, 160 cases of EVALI were reported to CDPH. At the time of initial case report, CDPH collected patient age, sex, and basic clinical information, including intensive care unit (ICU) admission and mechanical ventilation. CDPH clinicians reviewed and abstracted medical records for 106 patients (66%) with complete records available to gather data on additional clinical variables.

Local health department staff interviewed 86 patients (54%) or their family members in person or by telephone using a standardized questionnaire developed by CDPH in consultation with other states and the CDC. Patients were asked to report each type of product used, including different brands, flavors, and active ingredients, as a unique product. For each unique vaping product used, interviewed patients were asked to report product information such as active ingredient, frequency of use, and method of product acquisition. Specific locations of product acquisition named in patient interviews were compared with the California Bureau of Cannabis Control (BCC) License Search database.9

We calculated P values for categorical variables using Pearson χ2 tests, or 2-sided Fisher exact tests for cells with small values, and t tests for continuous variables. Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). We considered P values less than .05 to be statistically significant.

Laboratory Analysis of Recovered Vaping Materials

Vaping materials, including cartridges, pods, oils, and devices, were collected from patients voluntarily by local health jurisdictions; some patients declined to provide products or no longer had products available. Samples with sufficient residual liquid were tested by CDPH, and a subset tested by a partner state public health laboratory, in the order received by CDPH. Gas- and liquid-chromatography with mass spectrometry were performed to screen for THC, CBD and other cannabinoids, nicotine, vitamin E (alpha tocopherol; VE) and vitamin E acetate (alpha tocopheryl acetate, an esterified form of vitamin E; VEA), pesticides, synthetic cannabinoids, opioids, and other nontargeted compounds. Total reflection x-ray fluorescence was used to screen for metals (see eMethods in the Supplement for methodological details).

Ethical Considerations

The California Health and Human Services Agency’s Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects determined that this investigation was exempt from review, as well as waived the need for patient informed consent, because the content involved public health practice, not research.

Results

Case Demographics

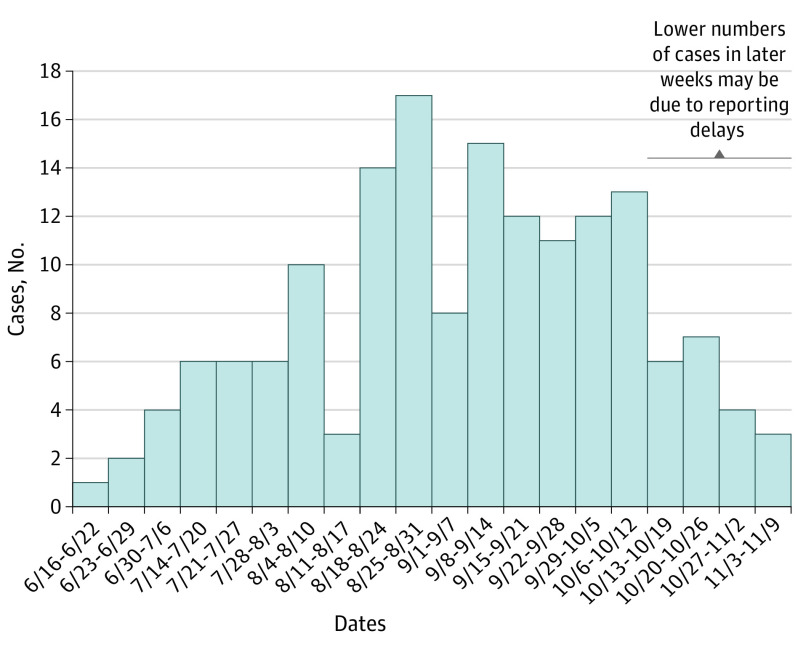

Among 160 patients with EVALI, the median age was 27 years (range, 14-70 years), and 99 (62%) were male (Table 1). Patients were admitted to the hospital between June 18 and November 6, 2019 (Figure). Among 86 patients interviewed, 38 (46%) were non-Hispanic white, and 39 (47%) were Hispanic. Race and ethnicity were only available for interviewed patients and based on their self-report, with categories selected by the investigators with the options of other and declines response available. There were no statistically significant differences in age or sex among interviewed and noninterviewed patients.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics and Self-reported Vaping Behaviors of Patients With EVALI.

| Characteristic or behavior (No. with data available) | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Sex (159) | |

| Male | 99 (62) |

| Female | 60 (38) |

| Age group, y (160) | |

| <18 | 25 (16) |

| 18-34 | 92 (58) |

| ≥35 | 43 (27) |

| Race/ethnicity (83)a | |

| White | 38 (46) |

| Black | 3 (4) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 (2) |

| Hispanic | 39 (47) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Patient vaping behaviors (86) | |

| Tetrahydrocannabinol product use | |

| Any use | 71 (83) |

| Exclusive use | 27 (31) |

| Nicotine product use | |

| Any use | 39 (47) |

| Exclusive use | 8 (9) |

| Cannabidiol product use | |

| Any use | 36 (43) |

| Exclusive use | 4 (5) |

| Frequency of vaping product use | |

| ≥1 time daily | 63 (73) |

| ≥5 times daily | 30 (35) |

Abbreviation: EVALI, e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury.

Persons with race reported as white, black, Asian/Pacific Islander, or other were non-Hispanic; Hispanic persons could be of any race.

Figure. Weekly Hospital Admissions for 160 Patients With EVALI in California, June to November 2019.

There were no cases reported during the week of July 7 through 13, 2020. EVALI indicates e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury.

Vaping Product Use

Among 86 patients interviewed, 71 (83%) reported vaping THC-containing products, and 27 (31%) reported exclusive use of THC products (Table 1). Nearly half (39 [47%]) reported using nicotine-containing vaping or e-cigarette products, and 8 (9%) reported exclusive use. Some (36 [43%]) reported using a CBD-containing product, and 4 (5%) reported exclusive use. One patient reported exclusive use of a flavor-only vaping product that did not contain THC, CBD, or nicotine. Most (63 [73%]) reported vaping at least daily, and 30 (35%) reported vaping 5 or more times daily.

The 86 interviewed patients reported using 130 (range, 1-5 per individual) unique vaping products in the 90 days prior to EVALI symptom onset (Table 2). Among 87 products reported to contain only THC, 79 (91%) were prefilled cartridges, while among 25 nicotine-only products, only 12 (48%) were prefilled cartridges. Forty-five of the 87 (56%) THC-containing products and 19 of the 25 (76%) nicotine-containing products reportedly contained flavoring.

Table 2. Reported Characteristics of 130 Vaping Products Used by 86 Patients With EVALI in the 3 Months Before Symptom Onset.

| Characteristic | Reported active ingredienta | |

|---|---|---|

| THC-only products (n = 87) | Nicotine-only products (n = 25) | |

| Product form | ||

| Prefilled cartridge | 79 (91) | 12 (48) |

| Fillable liquid or oil | 4 (5) | 13 (52) |

| Solid (plant, wax, etc) | 4 (5) | 0 |

| Contains flavoring | 45 (56) | 19 (76) |

| Method of acquisition | ||

| Bought at a vape shop or dispensary | 28 (33) | 11 (44) |

| Bought at a different type of storeb | 0 | 3 (12) |

| Bought online | 1 (1) | 2 (8) |

| Bought at a pop-up shop | 12 (14) | 0 |

| Ordered from a delivery service | 7 (8) | 0 |

| Bought or received from another person | 38 (44) | 7 (28) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 2 (8) |

Abbreviations: CBD, cannabidiol; EVALI, e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

Smaller values of reported active ingredients include cannabidiol only (n = 5 [4%]), THC and CBD (n = 5 [4%]), nicotine and CBD or THC (n = 3 [2%]), and unknown (n = 5 [4%]).

Such as convenience store, gas station, or supermarket.

Nicotine-containing products were most commonly reported as purchased at vape shops or dispensaries (11 of 25 [44%]) or bought or received from another person (7 of 25 [28%]); THC-containing products were most commonly bought or received from another person (38 of 87 [44%]) or purchased at a vape shop or dispensary (28 of 87 [33%]). When asked specifically whether THC-containing products had been acquired at a licensed dispensary, patients answered affirmatively for only 22 of 87 (25%) THC-containing products, which represent a subset of the 28 products reported as purchased at vape shops or dispensaries (Table 2). Of the 22 products, only 4 products, belonging to 1 patient, had a named purchase location verified as a licensed dispensary in the BCC database. The remaining 18 (82%) products were either reported as acquired from a pop-up shop or from another individual (5 products), acquired from a named establishment that was not listed as licensed in the BCC database (4 products), or did not have a named purchase location that could be searched in the BCC database (9 products).

Among the 86 interviewed patients, median time from last vaping product use to EVALI symptom onset and to hospital admission was 3 days (range, 0-73 days) and 5 days (range, 0-87 days), respectively. Thirty-four of 79 patients (43%) reported continued vaping after symptom onset; 6 (8%) reported continued vaping after hospital admission.

Clinical Findings

Among all 160 patients, median time from symptom onset to hospital admission was 5 days (range, 0-30 days). Among 106 patients with complete medical records available, 69 (65%) sought outpatient or emergency medical care at least once prior to hospital admission, and 44 (42%) had been prescribed antibiotics or antivirals as an outpatient (Table 3). Additionally, 41 (39%) patients had a documented diagnosis of anxiety or depression, and 15 (14%) had a history of asthma. A total of 45 (42%) patients reported either current or former combustible tobacco smoking.

Table 3. Clinical Characteristics of Case Patients With EVALI.

| Characteristic | No./No. with data available (%) |

|---|---|

| Preexisting medical conditions | |

| Anxiety or depression | 41/106 (39) |

| Asthma | 15/106 (14) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2/106 (2) |

| Combustible tobacco use | |

| Current | 19/106 (18) |

| Former | 26/106 (25) |

| Never | 45/106 (42) |

| Not documented | 16/106 (15) |

| Symptoms at presentation | |

| Days from symptom onset to admission, median (range) | 5 (0-30) |

| Respiratory symptoms, any | 100/106 (94) |

| Cough | 89/106 (84) |

| Shortness of breath | 87/106 (82) |

| Chest pain | 48/106 (45) |

| Hemoptysis | 9/106 (9) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms, any | 84/106 (79) |

| Nausea | 65/106 (61) |

| Vomiting | 59/106 (56) |

| Abdominal pain | 33/106 (31) |

| Diarrhea | 36/106 (34) |

| Constitutional symptoms, any | 94/106 (89) |

| Subjective fever or chills | 80/106 (76) |

| Fatigue or malaise | 43/106 (41) |

| Myalgia or body aches | 24/106 (23) |

| Headache | 27/106 (26) |

| Weight loss | 18/106 (17) |

| Sweating or diaphoresis | 16/106 (15) |

| Medical care prior to episode of hospitalization | |

| Seen in outpatient clinic, urgent care, or emergency department | 69/106 (65) |

| Prescribed antibiotics or antivirals | 44/106 (42) |

| Initial diagnosis of pneumonia | 28/106 (26) |

| Vital signs at admission | |

| Temperature >38 °C | 41/106 (39) |

| Heart rate >90 bpm | 94/106 (89) |

| Respiratory rate >20 breaths/min | 69/106 (65) |

| Oxygen saturation <93% or required supplemental oxygen | 73/106 (69) |

| Met ≥2 systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria at admissiona | 98/106 (93) |

| Laboratory values | |

| White blood cell count >12 000/mm3 | 86/106 (81) |

| White blood cell count with >80% neutrophils | 86/106 (81) |

| Sodium <135 mmol/L | 44/106 (42) |

| Potassium <3.5 mmol/L | 38/106 (36) |

| Bicarbonate <21 mmol/L | 11/106 (10) |

| ALT and/or AST >35 U/L | 54/106 (51) |

| Lipase >60 U/L | 10/45 (22) |

| Procalcitonin | |

| <0.5 ng/mL | 37/70 (53) |

| 0.5-2.0 ng/mL | 17/70 (24) |

| >2.0 ng/mL | 16/70 (23) |

| Lactic acid >2 mmol/L | 17/85 (20) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate >30 mm/h | 35/37 (95) |

| Chest imaging findings | |

| Bilateral infiltrates or opacities | 100/106 (94) |

| Ground glass opacities | 52/106 (49) |

| Pulmonary edema | 13/106 (12) |

| Subpleural sparing | 7/106 (7) |

| Diagnostics performed | |

| Bronchoscopyb | 36/106 (34) |

| Normal bronchoscopy findings | 17/31 (55) |

| Inflammatory changes | 6/31 (19) |

| Lung biopsy | 7/106 (7) |

| Care received during hospitalization | |

| Length of hospitalization, median (range), d | 6 (1-37) |

| ICU admission | 71/156 (46) |

| Length of ICU admission, median (range), d | 5 (1-13) |

| Intubation and mechanical ventilation | 46/154 (29) |

| Maximum respiratory support among nonintubated patients | |

| CPAP or BiPAP | 13/106 (12) |

| High-flow oxygen | 15/106 (14) |

| Nasal cannula | 29/106 (29) |

| Treated with antibiotics | 104/106 (98) |

| Treated with vasopressors | 11/106 (10) |

| Treated with steroids | 85/106 (80) |

| Clinical improvement with steroids documented | 58/85 (68) |

| Clinical outcomes | |

| Discharged on supplemental oxygen | 15/106 (14) |

| Died | 4/160 (3) |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BiPAP, bilevel positive airway pressure; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; EVALI, e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury; ICU, intensive care unit; bpm, beats per minute.

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome criteria include temperature greater than 38 °C or lower than 36 °C, heart rate greater than 90, respiratory rate greater than 20, and white blood cell count greater than 12 000 or less than 4000 mm3.

Bronchoscopy procedure notes were only available for 31 of 36 patients with bronchoscopies performed.

Of the 106 patients with complete medical records available, the most commonly reported symptoms were cough (89 [84%]), shortness of breath (87 [82%]), and subjective fever or chills (80 [76%]). Eighty-four (79%) patients reported at least 1 gastrointestinal symptom (Table 3). At admission, 98 (93%) patients met at least 2 systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria. Of 85 patients tested, 17 (20%) had lactic acid greater than 2 mmol/L, and of 70 patients tested, 33 (47%) had procalcitonin greater than 0.5 ng/mL. Bilateral findings of infiltrates or opacities were observed on chest imaging in 100 of 106 (94%) patients.

Nearly all patients (104 of 106 [98%]) were treated with antibiotics during their hospital admission. Eighty-five of 106 (80%) patients received systemic steroids; of those who received steroids, 58 (68%) had documented clinical improvement. Fifteen of 106 (14%) patients were discharged from the hospital on supplemental oxygen. Four of 160 patients (3%), who were between the ages of 40 and 65 years, died in the hospital.

Among 156 patients with available data, 71 (46%) required admission to an ICU during their hospitalization, including 34 of 60 (57%) females and 37 of 95 (38%) males (P = .03). Of 154 patients with available data, 46 (29%) required mechanical ventilation. Among the 106 patients with complete medical records, 78 (74%) required some form of respiratory support (mechanical ventilation, positive airway pressure, high-flow oxygen, and/or oxygen via nasal cannula), and median length of hospitalization was 6 days (range, 1-37 days). There were no other statistically significant associations among ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, or length of hospitalization and age, reported substances vaped, or vaping frequency (Table 4). There were no statistically significant differences in mechanical ventilation or ICU admission between interviewed and noninterviewed patients.

Table 4. Severity of Illness by Demographic Characteristics and Vaping Behaviors of Patients With EVALI.

| Characteristic | No./No. with data available (%)a,b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | Mechanical ventilation | Hospitalization length >1 wk | |

| Sex | 155 | 153 | 95 |

| Male | 37/95 (38)c | 24/94 (25) | 17/59 (29) |

| Female | 34/60 (57)c | 22/59 (39) | 17/36 (47) |

| Age group, y | 156 | 154 | 96 |

| <18 | 11/24 (45) | 6/24 (25) | 3/12 (20) |

| 18-34 | 38/90 (42) | 25/88 (28) | 18/52 (37) |

| ≥35 | 22/42 (52) | 15/42 (36) | 12/29 (41) |

| Reported substances vapedd | 81 | 81 | 53 |

| THC only | 8/26 (31) | 4/27 (15) | 3/16 (19) |

| Nicotine only | 3/8 (38) | 3/8 (38) | 3/5 (60) |

| Both THC and nicotine | 26/47 (55) | 14/46 (30) | 16/32 (50) |

| Reported vaping frequency | 85 | 85 | 57 |

| ≥1 times daily | 29/62 (47) | 17/63 (27) | 18/39 (46) |

| Less than daily | 10/23 (44) | 6/22 (27) | 6/18 (33) |

| ≥5 times daily | 16/29 (55) | 9/30 (30) | 9/16 (56) |

| <5 times daily | 23/56 (41) | 14/55 (25) | 15/26 (41) |

Abbreviations: CBD, cannabidiol; ICU, intensive care unit; EVALI, e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

Denominators differ across columns owing to missing data for these variables as well as for individual characteristic variables.

Percentages are horizontal (ie, percent of patients admitted to the ICU, mechanically ventilated, or hospitalized for >1 week for each specified characteristic).

Indicates statistically significant difference between groups (P < .05).

Cannabidiol-only users (n = 5) excluded from analysis.

Product Analyses

Chemical analyses were performed on a total of 87 vaping products from 24 patients. Forty-nine products (56%) contained cannabis-derived compounds and 38 (44%) contained nicotine. All cannabis-containing products contained THC; 24 also contained CBD. No products contained both THC and nicotine, and no products contained CBD exclusively. Of the 24 patients with tested products, 20 submitted at least 1 product containing THC, 8 submitted at least 1 product containing nicotine, and 4 submitted both (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

In the 49 THC-containing products, VE and/or VEA was found in 41 (84%), which corresponds to 16 patients with VE and/or VEA products in the 20 (80%) patients who submitted THC-containing products. Of 41 products with either VE or VEA, 32 contained both substances, 2 contained VEA only, and 7 contained VE only. VEA concentrations measured in 13 samples by the partner state laboratory ranged from 37% to 64%. No nicotine-containing products were found to contain VE or VEA. Propylene glycol was found in 34 of 38 (89%) nicotine-containing products and no THC-containing products (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Ten vaping product liquids were screened for metals. Levels of arsenic, cadmium, chromium, mercury, manganese, and lead were below 100 parts per billion. Nickel was detected in 1 product.

Low levels of pesticides were found in 12 of 18 (67%) THC-containing products tested by a partner state laboratory for these substances. Detected pesticides included myclobutanil, bifenthrin, bifenazate, tebuconazole, metalaxyl, propiconazole, imidacloprid-urea, piperonyl butoxide, and trifloxystrobin. No synthetic cannabinoids or opioids were found in 27 products tested for these substances.

Discussion

This report—the first to our knowledge to describe cases in a state with a legal adult-use (recreational) cannabis market—appears to confirm patterns of clinical findings and vaping practices previously reported in other states and nationally.6,10,11 Although California has a legal adult-use cannabis market, the majority of affected patients reported using THC-containing products obtained from informal sources, such as friends or acquaintances or unlicensed retailers. In addition, most THC-containing products tested contained VEA, which has recently been identified in both clinical and product samples from patients with EVALI.

Clinical Significance

Consistent with previous reports,6,10,11 in California, EVALI affected predominantly young, otherwise healthy patients, many of whom presented with both respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms, and ultimately developed severe illness requiring ICU admission and mechanical ventilation. In addition, many patients sought care from outpatient or other health care providers at least once prior to hospitalization. The findings of this case series suggest that many patients with EVALI present with a severe inflammatory response, including signs, symptoms, and laboratory findings often presumed to be infectious by both outpatient and inpatient health care providers. These findings underscore the importance for all clinicians, including outpatient health care providers, to consider EVALI in patients with a history of vaping who present with typical findings of infection, as well as monitor their clinical course and respiratory status closely for decompensation, in accordance with CDC guidance.12 Clinicians should also continue to report suspected cases to local health departments to allow for ongoing public health surveillance and intervention. The high proportion of patients who improved clinically with systemic steroids suggests that steroid therapy may be beneficial, though additional research is needed to determine which patients may benefit most and which therapeutic regimens may be appropriate.12,13

Although the majority of patients with EVALI were male, we found that a higher proportion of female patients required ICU admission compared with male patients. Although this comparison was not adjusted for other potentially confounding variables, studies of other lung diseases have also suggested that women may be more susceptible to the effects of certain environmental insults, such as tobacco smoke.14

The most common preexisting comorbidities among California patients with EVALI were depression and anxiety, which is consistent with reports from other states.6,10,15 These findings may indicate higher vaping rates in patients with these conditions and/or increased risk of EVALI in these individuals. Although it has been suggested that use of nicotine e-cigarettes may be associated with certain mental health diagnoses,16 further research is needed to understand the link between depression and anxiety and EVALI.

In addition to the respiratory support required during hospitalization, 14% of patients required supplemental oxygen at time of hospital discharge. While limited short-term follow-up of patients with EVALI has shown persistent postdischarge symptoms and pulmonary function abnormalities,10,17 little is known about the potential long-term consequences of EVALI, such as sustained deficits in pulmonary function. Continued follow-up and investigation of clinical outcomes in affected patients is needed to answer these questions.

Patient Demographics and Vaping Product Use

Overall, patient demographic and product-use patterns reported here are similar to those reported among patients in other states where cannabis use is illegal.15,18 The proportion of Hispanic patients in California (47%) is higher than nationally (16%); though this may reflect demographic differences in the overall population, it also highlights the need for additional investigation regarding vaping practices among different demographic groups.

Most patients interviewed (73%) reported vaping at least daily, and 35% reported vaping 5 or more times daily. Prior reports have suggested that higher frequency of vaping THC products may be associated with increased risk of EVALI.7 However, among affected patients in California there was no statistically significant association between vaping frequency and ICU admission or mechanical ventilation.

While most California patients reported vaping THC-containing products obtained from informal sources, some denied use of THC-containing vaping products. Recent findings from Illinois suggest that patients with EVALI who only vaped nicotine may differ in their demographics and clinical presentations from patients using THC-containing products, which potentially suggests a different contributing cause of injury.19 This subgroup of patients merits additional investigation, both in California and nationally.

Although cannabis products can be obtained from licensed dispensaries in some California municipalities, most patients with EVALI reported obtaining products from informal sources, which may not have performed state-mandated product testing. Among all adults in California who report vaping cannabis products, 76% reported stores or dispensaries as their usual product sources20; by comparison, patients with EVALI reported purchasing only 34% of THC products from vape shops or dispensaries. In addition, even among patients with EVALI who reported obtaining products from licensed dispensaries, most did not, in fact, name licensed purchase locations. More research about the factors influencing consumers’ choice of THC products, and education about where to safely obtain legal cannabis products, are needed to limit the use of potentially hazardous products from informal sources.

Underlying Cause of Lung Injury

Although histopathologic findings from patients with EVALI have suggested airway-centered chemical pneumonitis,21,22 this pattern can represent a nonspecific response to a wide variety of toxicants. Recently, attention has focused on VEA, an esterified form of VE that is typically ingested as a dietary supplement or applied to the skin in cosmetic products. VEA was identified in the majority of patients’ THC-containing products tested by CDPH, other states, and the US Food and Drug Administration.8,15,23,24 In addition, CDC detected VEA in 94% of bronchoalveolar lavage specimens from patients with EVALI that were tested from multiple states, including California.25 Furthermore, in Minnesota, none of 7 tested THC-containing vaping products seized by law enforcement in 2018 were found to contain VEA, whereas all 20 seized in September 2019 did contain VEA, which supports a temporal association between the introduction of VEA into the market and the EVALI outbreak.8

Beyond VEA, a wide range of possible etiologic agents has been proposed, including other diluents, metals, pesticides, flavorings, and microbial products, though none has been identified consistently in laboratory testing to date. CDPH identified a subset of THC-containing products with VE but not VEA; neither VE nor VEA were found in any nicotine-containing products. Although propylene glycol, a common diluent for nicotine-based e-cigarettes, was found in most nicotine-containing products in California, it was not found in any THC-containing products. Furthermore, levels of metals, pesticides, synthetic cannabinoids, and opioids in patient products tested by CDPH were low or below detection limits.

Before the EVALI outbreak, VEA was not a recognized nor suspected inhalational toxicant. Indeed, 1 animal study using aerosolized VEA did not report any toxic effects to the lungs at the dose used.26 However, lung injuries from inhalation of compounds thought to be safe via other routes, such as butter flavorings, textile dye, and humidifier biocide, have been described.27,28 Surfactant disruption and generation of ketene, a highly reactive respiratory toxicant, have been invoked as biologically plausible mechanisms of VEA lung toxic effects.25 It is also possible that other known or novel toxicants could be generated during VEA vaporization, perhaps because of reactions with other fluid constituents or vaping device components.

Limitations

This report is subject to several limitations. First, self-reporting of vaping practices may result in exposure misclassification because individuals may be unsure of the contents of their vaping products or may be hesitant to report use of products from informal sources. Second, only 54% of patients were interviewed; although age, sex, and disease severity of interviewed and noninterviewed patients were similar, the 2 groups may differ in other important ways. Product testing results were only available for a small sample of patients, and those patients may not have submitted all of their vaping products.

Conclusions

EVALI is a severe illness that continues to affect mostly young, otherwise healthy patients, with as yet undetermined long-term health effects. In this report, most patients in California reported using THC-containing products from informal sources, which suggests that individuals may continue to use unregulated products even in jurisdictions with licensed markets. Outreach by clinicians and public health departments is needed to educate patients and the public about the health risks associated with vaping, particularly vaping of unregulated cannabis products.

In addition, most THC-containing products tested in California contained VEA, which reinforces the potential association between this chemical and EVALI that has been suggested by prior studies of patient and product samples. However, additional research is needed to address the many unknowns still associated with this outbreak. Although most patients reported using THC-containing products, other potential causes of illness cannot be excluded at this time, particularly given the subset of patients in California and nationally who do not report use of THC-containing products. Therefore, while this investigation is ongoing, CDPH urges that individuals refrain from e-cigarette use and vaping of all substances, particularly THC-containing products from unregulated sources.29

eFigure 1. California Department of Public Health case definition for e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI)

eMethods. Detailed laboratory methods for analysis of case-patient vaping materials

eTable 1. Number of patients with product types identified by laboratory testing

eTable 2. Patient product types and diluents identified by laboratory testing.

References

- 1.Gentzke AS, Creamer M, Cullen KA, et al. . Vital signs: tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(6):157-164. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, et al. . e-Cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2095-2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.18387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.e-Cigarette use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services Accessed February 20, 2020. https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/2016_SGR_Full_Report_non-508.pdf.

- 4.Meiman J. Severe pulmonary disease among adolescents who reported vaping. Wisconsin Department of Health Services July 25, 2019. Accessed November 11, 2019. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/dph/memos/beoh/2019-02.pdf.

- 5.Outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Updated February 11, 2020. Accessed February 20, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html.

- 6.Layden JE, Ghinai I, Pray I, et al. . Pulmonary illness related to e-cigarette use in Illinois and Wisconsin—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. Published online September 6, 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navon L, Jones CM, Ghinai I, et al. . Risk factors for e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) among adults who use e-cigarette, or vaping, products—Illinois, July-October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(45):1034-1039. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor J, Wiens T, Peterson J, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Task Force . Characteristics of e-cigarette, or vaping, products used by patients with associated lung injury and products seized by law enforcement—Minnesota, 2018 and 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(47):1096-1100. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6847e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.California Bureau of Cannabis Control License Search. Bureau of Cannabis Control California Accessed November 11, 2019. https://online.bcc.ca.gov/bcc/customization/bcc/cap/licenseSearch.aspx.

- 10.Blagev DP, Harris D, Dunn AC, Guidry DW, Grissom CK, Lanspa MJ. Clinical presentation, treatment, and short-term outcomes of lung injury associated with e-cigarettes or vaping: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394(10214):2073-2083. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32679-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moritz ED, Zapata LB, Lekiachvili A, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Task Force . Update: characteristics of patients in a national outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injuries—United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(43):985-989. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6843e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jatlaoui TC, Wiltz JL, Kabbani S, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Clinical Working Group . Update: interim guidance for health care providers for managing patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury—United States, November 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(46):1081-1086. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6846e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel DA, Jatlaoui TC, Koumans EH, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Clinical Working Group; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group . Update: interim guidance for health care providers evaluating and caring for patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury—United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(41):919-927. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6841e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han MKA-SE, Arteaga-Solis E, Blenis J, et al. . Female sex and gender in lung/sleep health and disease: increased understanding of basic biological, pathophysiological, and behavioral mechanisms leading to better health for female patients with lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(7):850-858. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201801-0168WS [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis N, McCaffrey K, Sage K, et al. . E-cigarette use, or vaping, practices and characteristics among persons with associated lung injury—Utah, April-October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(42):953-956. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6842e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spears CA, Jones DM, Weaver SR, Pechacek TF, Eriksen MP. Use of electronic nicotine delivery systems among adults with mental health conditions, 2015. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;14(1):E10. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14010010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou RH, Tiberio PJ, Triantafyllou GA, et al. . Clinical characterization of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury in 36 patients in Pittsburgh, PA. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Published online February 5, 2020. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202001-0079LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghinai I, Pray IW, Navon L, et al. . E-cigarette product use, or vaping, among persons with associated lung injury—Illinois and Wisconsin, April-September 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(39):865-869. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6839e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghinai I, Navon L, Gunn JKL, et al. . Characteristics of persons who report using only nicotine-containing products among interviewed patients with e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury—Illinois, August-December 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(3):84-89. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6903e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.California Department of Public Health Online California Adult Tobacco Survey. 2018.

- 21.Butt YM, Smith ML, Tazelaar HD, et al. . Pathology of vaping-associated lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1780-1781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1913069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukhopadhyay S, Mehrad M, Dammert P, et al. . Lung biopsy findings in severe pulmonary illness associated with e-cigarette use (vaping). Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153(1):30-39. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqz182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.New York State Department of Health announces update on investigation into vaping-associated pulmonary illnesses. News release. New York State Department of Health September 5, 2019. Accessed October 28, 2019. https://www.health.ny.gov/press/releases/2019/2019-09-05_vaping.htm.

- 24.Lung injuries associated with use of vaping products: information for the public, FDA actions, and recommendations. US Food and Drug Administration. Accessed November 11, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/lung-injuries-associated-use-vaping-products.

- 25.Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Laboratory Working Group . Vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):697-705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hybertson BM, Chung JH, Fini MA, et al. . Aerosol-administered alpha-tocopherol attenuates lung inflammation in rats given lipopolysaccharide intratracheally. Exp Lung Res. 2005;31(3):283-294. doi: 10.1080/01902140590918560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cummings KJ, Kreiss K. Occupational and environmental bronchiolar disorders. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(3):366-378. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1549452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nemery B, Hoet PH. Humidifier disinfectant-associated interstitial lung disease and the Ardystil syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(1):116-117. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1726LE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Another death in California and investigation into e-cigarette and vaping-associated illnesses continues as potential chemical of concern is identified. News release. California Department of Public Health November 13, 2019. Accessed December 2, 2019. https://cdph.ca.gov/Programs/OPA/Pages/NR19-031.aspx.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. California Department of Public Health case definition for e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI)

eMethods. Detailed laboratory methods for analysis of case-patient vaping materials

eTable 1. Number of patients with product types identified by laboratory testing

eTable 2. Patient product types and diluents identified by laboratory testing.