Abstract

Purpose of review:

The majority of pediatric antibiotic use occurs in outpatients. However, the optimal strategies for antimicrobial stewardship in this setting are unknown. We sought to identify studies relevant to pediatric outpatient stewardship that have been published in the past decade. The details of this systemic review are presented along with targets for future stewardship efforts and discussion regarding effective outpatient stewardship strategies.

Recent findings:

In 2016 the CDC released the “Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship,” that serve as practical guidelines to develop impactful and sustainable ASP interventions: commitment, action for policy and practice, tracking and reporting, and education and expertise. However, there has not been a recent review of the primary medical literature on pediatric outpatient stewardship. A systematic review of pediatric antibiotic control strategies published in 2007 identified 28 studies overall, 8 of which focused on outpatients. Two subsequent systematic reviews published in 2015 and 2018 intentionally excluded outpatients.

Summary:

Outpatient settings are a crucial component of pediatric antimicrobial stewardship in the United States. Establishing effective stewardship interventions can protect children and optimize clinical outcomes in outpatient health care settings. Based on our review of the literature it is clear that the optimal outpatient stewardship strategies remain to be elucidated. However, there is robust literature describing variability in outpatient antibioitic prescribing that can be used to target interventions.

Keywords: Antimicrobial stewardship, outpatient antibiotic use, pediatrics

Introduction:

Antimicrobial resistance is a significant public health risk with overuse and misuse of antibiotics as the primary drivers. Increasing emphasis on intervention at the local, national, and international levels have led to such efforts as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) 12-Step Program to Prevent Antimicrobial Resistance, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Principles and Strategies to Limit the Spread of Antimicrobial Resistance, and the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance. At the hospital level, a growing number of antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) have demonstrated success in reducing inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing including errors in guideline-based antimicrobial selection, dose, and duration, while also reducing cost burden and patient morbidity. To date, most studies have focused on inpatient prescribing. Although the majority of pediatric antibiotic prescribing occurs in outpatient arenas, there is a limited evidence base to guide stewardship interventions in this patient setting.

In 2016 the CDC released the “Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship,” that serve as pillars of impactful and sustainable ASP interventions: commitment, action for policy and practice, tracking and reporting, and education and expertise.1 However, there has not been a recent review of the primary medical literature on pediatric outpatient stewardship. A systematic review of pediatric antibiotic control strategies published in 2007 identified 28 studies overall, 8 of which focused on outpatients. Two subsequent systematic reviews published in 20152 and 20183 intentionally excluded outpatients. We sought to identify additional studies relevant to pediatric outpatient stewardship that have been published in the past decade.

Methods:

We used PubMed to identify articles that focused on outpatient pediatric antibiotic use and potential outpatient stewardship strategies. The search was limited to articles published in the United States from January 2006 to December 31, 2018. We used the same search strategy as Smith et al.2 Specifically, articles were selected for initial review if any of the following terms were included in the title or abstract: “antimicrobial stewardship,” “antimicrobial control,” “antibiotic control,” or “antibiotic stewardship.” Selection was further limited to those studies that contained the terms: “child,” “children,” “pediatric*” (“*” includes all terms with the same stem), “paediatric*,” “newborn,” “infant,” or “neonat*” in the title or abstract.

Study Review and Selection

Both authors reviewed titles of all studies meeting initial search criteria. Titles that were suggestive of outpatient antibiotic use were selected for abstract review. Our primary aim was to identify studies that described specific outpatient stewardship interventions. However, we also included articles that included data relevant to any of the CDC core outpatient elements. We excluded studies about outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy and antibiotic use in the emergency department setting.

Results

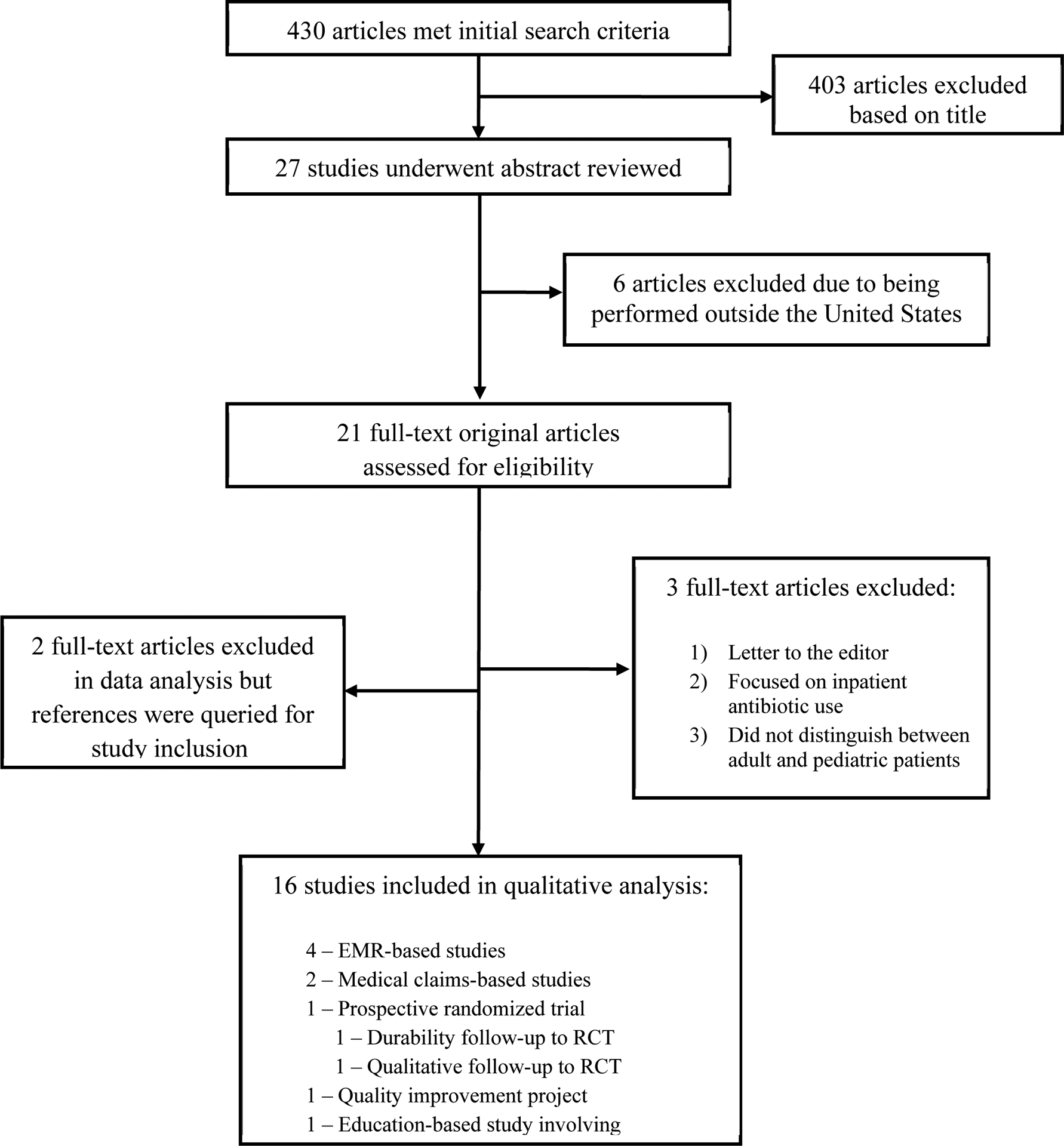

430 articles met our initial search criteria (Figure 1). Of these, 26 titles appeared to be relevant to pediatric outpatient antibiotic use and underwent abstract review. 6 were excluded because they described studies performed outside the United States. Of the remaining 20 studies, one was a letter to the editor, one focused on inpatient antibiotic use, one did not distinguish between adult and pediatric patients, and two did not provide patient-level information. The search also identified two review articles; these were not included in data analysis, but their references were queried for study inclusion. The remaining 13 articles were reviewed in depth.

Figure 1.

Study selection.

Seven articles identified variations in clinical practice and/or antibiotic prescribing that could be used to identify targets for outpatient stewardship interventions. Only one study involved a randomized trial of a systematic antimicrobial outpatient stewardship intervention. This study accounted for 3 publications reporting on the original trial, a follow-up study performed after the trial had concluded and the results of qualitative interviews with study participants.

The remaining studies included a study based on nationally representative survey data (1) a urine culture follow-up program at an urgent care center (1) and a study of provider education (1).

Targets for Stewardship Interventions

EMR-based studies

Our search identified 5 articles that examined outpatient antibiotic use across outpatient networks using data from electronic medical records.

Gerber and colleagues used electronic health records from a network of 29 pediatric practices in Pennsylvania and New Jersey to assess antibiotic use for acute otitis media (AOM), sinusitis, streptococcal pharyngitis, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and urinary tract infection (UTI).4 Data were collected from calendar year 2009. The authors identified significant variability in antibiotic prescribing which ranged from 18–36% across practices overall. Perhaps more concerning was the finding that broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing for these indications ranged from 15–57%, even after excluding children with antibiotic allergies. When stratified by specific diagnosis, and after adjusting for age, sex, race and insurance type, the authors found significant variation in the likelihood of diagnosis for all of the respiratory diagnoses, with less variation for UTI.

A second study performed in this same network focused specifically on CAP from July 2009 to June 2013.5 The outcomes of interest included prescription of narrow-spectrum (penicillin or amoxicillin) as compared to broad-spectrum (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cephalosporin or a fluoroquinolone) antibiotics or macrolides. 16.8% of children with CAP received broad-spectrum antibiotics, mostly amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, with significant variation in proportion of broad-spectrum prescribing across the sites. Factors independently associated with broad-spectrum prescribing in multivariable analysis included care in a suburban practice and previous antibiotic exposure.

A study in a network of practices in western Wisconsin, eastern Minnesota and northeastern Iowa focused on visits for AOM, CAP and skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) from August 2009-July 2010.6 The authors compared prescription rates and prevalence of guideline-concordant therapy by provider type (pediatric clinic, family practice clinic, emergency department). Antibiotic prescriptions for these diagnoses were more common in the emergency room setting. Use of first-line therapy was high for AOM (73%) and SSTI (78%). However, treatment of CAP was less likely to be guideline-concordant, with 22.5% of children receiving therapy that was not consistent with national guidelines. Specifically, nearly half of all children received a macrolide.

The most recent study identified patients less than 18 years who had an outpatient visit for AOM, pharyngitis, viral upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in a network of clinics in Wisconsin from 2011 to 2016.7 The authors sought to identify differences in prescribing patterns between pediatricians and non-pediatrician providers. Indeed, they found that pediatricians were more likely to withhold antibiotics for viral URI (87%) as compared to non-pediatric physicians (81%) and advanced practice providers (77%). There were no significant differences between rate of first-line antibiotic prescribing for AOM, pharyngitis or ABS. However, pediatricians were significantly more likely to treat children with pharyngitis only if they had a positive test for group A strep.

We also identified a single-center study that retrospectively reviewed records of all patients who had streptococcal throat cultures or rapid antigen tests performed from August 2011 to July 2012.8 The authors used data available from medical records to determine the likelihood of group A streptococcal (GAS) infection. Among children who had sufficient documentation in the medical record, the authors concluded that most tests were indicated. However, 28% of antibiotic prescriptions were not indicated. This suggests that treatment of negative cultures may be a more appropriate stewardship target than indiscriminate testing for GAS.

Medical claims-based studies

Two studies report the use of claims data to identify targets for stewardship efforts. Watson and colleagues used healthcare claims data from a Medicaid accountable care organization in central and southeast Ohio to identify targets for outpatient antimicrobial stewardship.9 They examined patterns of pediatric outpatient prescribing for all enteral and parenteral antibiotics. They also assessed variability in treatment rates across all providers for upper respiratory tract infections. Across the network, antibiotic treatment for URTIs was significantly more likely in rural, high-poverty counties. Visits with non-pediatricians (emergency medicine, family medicine, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) were also more likely to result in antibiotic treatment.

Using these same data, Jaggi et al identified factors associated with treatment of SSTIs.10 They specifically assessed risk factors for long duration (> 7 days) and non-first-line therapy. Interestingly, residence in a rural county had lower odds of long duration therapy but living in a high-poverty county had higher odds. Visits with non-pediatricians (same definition as above) were associated with decreased odds of long duration but greater odds of non-first-line therapy.

Nationally representative data

Kronman et al. used data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) to assess rates of prescription for respiratory infections (AOM, ABS, bronchitis, URTI and pharyngitis) from 2000–2010.11 They then performed a systemic review of the literature to determine expected rates of bacterial infection for these diagnoses. Across the entire study period 57% of visits were associated with an antibiotic prescription, whereas the expected rate of prescription was 27%.

Outpatient stewardship interventions

Our search identified one prospective randomized trial.12 This study evaluated outpatient antimicrobial stewardship by comparing prescribing between intervention and control practices using a common EMR. Prescribing rates for targeted acute URTIs were standardized for age, sex, race, and insurance from 20 months before the intervention to 12 months afterward (October 2008 – June 2011). The intervention consisted of a single one-hour, on-site clinical education session with subsequent personalized, quarterly audit and feedback of prescribing for bacterial and viral URTIs. Control practices were aware that they were participating in a trial but received no additional education or feedback. Overall, there was a statistically significant difference in broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing among intervention practices as compared to control practices. However, detailed differences for CAP, ABS, GAS pharyngitis, and viral infections reported indicated that the intervention did not affect antibiotic prescribing for viral infections.

These authors subsequently assessed the durability of these results by documenting antibiotic prescribing across intervention and control sites for 18 months after termination of audit and feedback.13 They found that the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics increased over time, reverting to above-baseline levels. While specific reasons for this reversal in prescribing trends were not assessed, these results highlight the importance of sustained and ongoing stewardship interventions in the outpatient arena.

The same research team subsequently published a qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with 24 providers from 6 primary care practices who participated in the cluster randomized control trial.14 While the majority of respondents recognized antibiotic overuse as an ongoing problem, potential reasons for significant changes in prescribing habits after intervention included social pressures from patient families, perception that antibiotic guidelines contrasted with clinical judgement and experience, ignored or expressed distrust about feedback reports, and perceptions of overuse by pediatricians versus other non-pediatric specific providers with overuse practices being attributed to non-pediatricians. The authors concluded that critical elements of stewardship such as effectiveness and sustainability rely heavily upon establishing credibility of ASPs with providers to help shape prescribing practices over time.

Our search identified one additional study that reported the results of a quality improvement project designed to improve antibiotic prescribing around urinary tract infections (UTIs) in a network of urgent care sites.15 The focus was on urine culture follow-up and appropriate discontinuation of therapy for negative cultures. There was an impressive increase in discontinuation of therapy, from 4% of all negative tests at baseline to 94% of tests at the end of the study. As a result, the authors reported a 40% decrease in days of outpatient therapy. Notably, none of the children included in the analysis had a return visit for UTI.

Education

Weddle et al. reported the impact of educational sessions provided for advanced care providers in a network of urgent care centers affiliated with a free-standing children’s hospital.16 Educational sessions were targeted at common urgent care diagnoses including UTI, SSTI, pharyngitis, URTI, AOM, and ABS. The sessions included review of published evidence-based prescription guidelines and local antibiograms. Chart review was performed at several intervals before and after the sessions with antibiotic appropriateness determined by adherence to guideline recommendations presented at the educational sessions. Results indicated a statistically significant reduction in inappropriate antibiotic choice, and separately, inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among all conditions at the nine-month period after the intervention

Discussion

In 2016, the CDC released the Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship.1 These include commitment, action for policy and practice, tracking and report, and education and expertise. According to the CDC, commitment from facility leaders to implement at least one intervention for improved prescribing practices combined with a tracking/reporting system is integral to outpatient stewardship efforts. Moreover, education resources for patients and families regarding appropriate antibiotic use as well as provider education with access to persons with expertise in antibiotic stewardship are integral to effective ASP efforts and have the most profound effect on both prescribing and clinical outcomes.

Most of the studies in this review focused on identifying targets for outpatient stewardship efforts, rather than demonstrating effectiveness of existing stewardship activities. Given that the bulk of outpatient antibiotic prescribing is for upper respiratory conditions it is not surprising that the vast majority of the studies focus on these diagnoses. Nevertheless, it is possible that our literature review may have missed published studies that were not captured by our search terms. We intentionally used the same terms used in a previous systematic review to be consistent with prior studies.2 Of note, there is now a separate Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) search term for antimicrobial stewardship that was introduced in 2018. As a secondary analysis we did use this MeSH term to identify additional studies. This yielded 507 studies published between 2014 and 2018, but interestingly only 1 of the studies ultimately included in this review was identified. Though beyond the scope of this review, future studies should include this new MeSH term in the search strategies.

Based on our review of the literature and the CDC core elements, we have attempted to define effective outpatient strategies that could be implemented and help encourage sustainable guideline-based prescribing:

Create a working relationship with an outpatient practice leader to direct antibiotic stewardship activities within a facility.

Target evidence-based education efforts at provider level, from nursing staff to mid-level providers, trainees (medical students, residents, fellows), and both pediatric and non-pediatric specific providers with the goal of these sessions to be schedule-accommodating, instructional and conversational rather than lecture-based. This may help prevent a hierarchal relationship that otherwise suggests ASP providers are somehow above the practitioners who are the ones integral in implementing changes in prescribing habits.

Include practices or outpatient networks in suburban and rural areas, since children seeking medical care in the regions have been shown to have higher rates of prescriptions for viral infections and higher rates of off-guideline, broad-spectrum antibiotics for conditions that do warrant antimicrobial therapy.

Encourage delayed prescribing practices or watchful waiting when appropriate including contingency plans for acute worsening of antimicrobial therapy. This engages families with the plan and has the potential to limit the perception that nothing was done for their child’s illness.

Support tracking and reporting systems that are easily accessed, user-friendly, and engage providers by encouraging helpful discourse amongst the practice and with the respective ASP personnel rather than systems that result in isolation and distrust.

Create educational materials for patients and families with relevant statistics and other information to support reduction in antibiotic use. Additionally, encourage office educational materials including posted signage regarding the practice’s goals for evidence-based care, especially in regards to antibiotic use.

Recognize cultural and demographic limitations to care and adjust stewardship efforts to accommodate these potential barriers to intervention. For example, some stewardship efforts may not be as effective as others considering patient population, health literacy, and access to care.

Conclusion

Outpatient settings are a crucial component of pediatric antimicrobial stewardship in the United States. Establishing effective stewardship interventions can protect children and optimize clinical outcomes in outpatient health care settings. Based on our review of the literature it is clear that the optimal outpatient stewardship strategies remain to be elucidated. However, there is robust literature describing variability in outpatient antibioitic prescribing that can be used to target interventions.

Funding

Dr. Kilgore was supported by the Foundation of the National Institute of Health (T32-AI007062-40, JW Sleasman, PI, and JT Kilgore, Fellow Trainee).

Abbreviations

- ABS

acute bacterial sinusitis

- AOM

acute otitis media

- ASP

antimicrobial stewardship program

- AR

antimicrobial resistance

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control

- CAP

community-acquired pneumonia

- EMR

electronic medical record

- GAS

group A streptococcal

- MeSH

pharyngitis; Medical Subject Heading

- NAMCS

National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

- SSTI

skin and soft tissue infection

- URTI

upper respiratory tract infection

- UTI

urinary tract infection

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Jacob T. Kilgore and Michael J. Smith declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1. ●.Sanchez GV, Fleming-Dutra KE, Roberts RM, Hicks LA. Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(6):14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This CDC publication outlines key components of outpatient antimicrobial stewardship activities

- 2.Smith MJ, Gerber JS, Hersh AL. Inpatient Antimicrobial Stewardship in Pediatrics: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2015;4(4):E127–E135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godbout EJ, Pakyz AL, Markley JD, Noda AJ, Stevens MP. Pediatric Antimicrobial Stewardship: State of the Art. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2018;20(10):13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Localio AR, et al. Variation in Antibiotic Prescribing Across a Pediatric Primary Care Network. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2015;4(4):297–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Handy LK, Bryan M, Gerber JS, Zaoutis T, Feemster KA. Variability in Antibiotic Prescribing for Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saleh EA, Schroeder DR, Hanson AC, Banerjee R. Guideline-concordant antibiotic prescribing for pediatric outpatients with otitis media, community-acquired pneumonia, and skin and soft tissue infections in a large multispecialty healthcare system. Clin Res Infect Dis. 2015;2(1). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frost HM, McLean HQ, Chow BDW. Variability in Antibiotic Prescribing for Upper Respiratory Illnesses by Provider Specialty. J Pediatr. 2018;203:76–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan-Krohn T, Ozonoff A, Sandora TJ. Adherence to guidelines for testing and treatment of children with pharyngitis: a retrospective study. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson JR, Wang L, Klima J, et al. Healthcare Claims Data: An Underutilized Tool for Pediatric Outpatient Antimicrobial Stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(11):1479–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaggi P, Wang L, Gleeson S, Moore-Clingenpeel M, Watson JR. Outpatient antimicrobial stewardship targets for treatment of skin and soft-tissue infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(8):936–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kronman MP, Zhou C, Mangione-Smith R. Bacterial prevalence and antimicrobial prescribing trends for acute respiratory tract infections. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e956–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. ●.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Effect of an Outpatient Antimicrobial Stewardship Intervention on Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Prescribing by Primary Care Pediatricians A Randomized Trial. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 2013;309(22):2345–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the only randomized trial of a pediatric outpatient stewardship intervention to date

- 13.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Durability of Benefits of an Outpatient Antimicrobial Stewardship Intervention After Discontinuation of Audit and Feedback. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 2014;312(23):2569–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szymczak JE, Feemster KA, Zaoutis TE, Gerber JS. Pediatrician Perceptions of an Outpatient Antimicrobial Stewardship Intervention. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:S69–S78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saha D, Patel J, Buckingham D, Thornton D, Barber T, Watson JR. Urine Culture Follow-up and Antimicrobial Stewardship in a Pediatric Urgent Care Network. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weddle G, Goldman J, Myers A, Newland J. Impact of an Educational Intervention to Improve Antibiotic Prescribing for Nurse Practitioners in a Pediatric Urgent Care Center. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31(2):184–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]