There are significant disparities in rates of cervical cancer screening for Sub-Saharan African immigrant (SSAI) women in the United States (U.S.) when compared to U.S. native-born women’s cervical cancer screening rates (Forney-Gorman & Kozhimannil, 2015, Hurtado-de-Mendoza, Song, Kigen, 2014, Tsui, Saraiya, Thompson, Dey, & Richardson, 2007), with SSAI women being much less likely to complete screening. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (2016) recommends screening for cervical cancer in women ages 21 to 65 with cytology every 3 years or with a combination of cytology and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) testing every five years for women age 30 to 65 years (Comparetto & Borruto, 2015). Research indicates that SSAI women in the U.S. have inadequate cervical cancer screening uptake (Forney-Gorman & Kozhimannil, 2015; Harcourt et al., 2013, Ndukwe, Williams, & Sheppard, 2013).

Inadequate cervical cancer screening uptake among SSAI women has been attributed to a variety of reasons including lack of awareness related to cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening (Adegboyega & Hatcher, 2016; Ndukwe et al., 2013), shorter length of residency in the U.S. (Harcourt et al., 2013; Sewali et al., 2015), and varied cultural beliefs (Ghebre et al., 2014; Raymond et al., 2014). SSAI women report individual, societal, and structural barriers to cervical cancer screening uptake that include language difficulties, distrust of interpreters, fear of cervical cancer screening, negative past cervical cancer screening experiences, and competing priorities (Ghebre et al., 2014; Hurtado-de-Mendoza et al., 2014). Despite opportunities for access to an advanced health care system when SSAI women migrate to the U.S., they encounter the same health care inequalities based on race and social class that are faced by the native U.S born population (Pinder, Nelson, Eckardt, & Goodman, 2016). A better understanding of the unique barriers that may affect SSAI women’s cervical cancer screening uptake may result in improvement in the screening disparity for this population and lead to a decrease in the disparate cervical cancer mortality.

Given the collective nature of African society, one factor that may contribute to inadequate cervical cancer screening for SSAI women may be limited involvement of their male partners in cervical cancer prevention. The World Health Organization [WHO] recommends involving men in the prevention of cervical cancer as with other aspects of women’s reproductive health (WHO, 2006). African men are often the “gatekeepers” of access to health care services for their wives and daughters, so their support (or, in extreme cases, their permission) may be needed if SSAI women are to obtain cervical cancer screening (WHO, 2006). Patriarchal practice is embedded in African culture (Kambarami, 2006, Makama, 2013), and patriarchal culture and social structure may influence use of gynecological services including cervical cancer screening. Thus, involving SSAI men in cervical cancer prevention activities is essential. Although cervical cancer is exclusively a female disease, men can play a key role in cervical cancer prevention and treatment if they have knowledge of cervical cancer risk factors and prevention strategies (WHO, 2006). The sexually transmitted infection HPV causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer; and men can contribute to HPV and cervical cancer prevention via HPV vaccination and safe sexual practices (WHO, 2006) hence, reducing the risk of cervical cancer for their female partners.

Role of spousal support in cervical cancer screening

In populations with cervical cancer screening disparities, empirical evidence supports positive effects associated with male involvement in cervical cancer screening practices. A study among Mexican immigrants in the U.S indicated that men have a role in effective screening programs for cervical cancer. When the male Mexican immigrants understood the risk factors related to cervical cancer and the benefits of cervical cancer screening, they were motivated to be supportive of screening for their female partners (Thiel de Bocanegra, Trinh-Shevrin, Herrera, & Gany, 2008).

Another key factor in a woman’s decision to participate in cervical cancer prevention services can be her husband’s emotional and financial support (Bingham et al., 2003, Isa Modibbo et al., 2016). A study among Nigerian women found that most participants indicated that they require spousal financial and emotional support before completing screening services (Isa Modibbo et al.,2016). Affordability of screening tests is a barrier that has been identified among women; thus, having support to alleviate this may encourage cervical cancer screening. Similarly, Lyimo and Beran (2012) found that husbands’ approval of Pap screening was strongly associated with Tanzanian women Pap screening uptake.

Extant literature identified that African men in Africa have low awareness and inaccurate knowledge related to cervical cancer and its prevention (Rosser, Zakaras, Hamisi, & Huchko, 2014; Williams & Amoateng, 2012). A study conducted among Ghanaian men found inaccurate knowledge related to cervical cancer and misconceptions about the risk factors for cervical cancer. However, several men indicated willingness to learn more about cervical cancer to be able to provide spousal support for cervical cancer screening uptake (Williams & Amoateng, 2012). Similarly, studies conducted in the U.S, among Latino immigrant males indicate that Latino men lack knowledge of cervical cancer screening which may impede their ability to assist their partners’ decisions to adopt screening habits (Treviño, Jandorf, Bursac, & Erwin, 2012). Men with higher cervical cancer knowledge and awareness are more likely to encourage their female partners to reduce their personal cervical cancer risks. Limited cervical cancer knowledge can lead to inaccurate beliefs and misconceptions (Lee, Tripp-Reimer, Miller, Sadler, 2007).

Significance of the study

While numerous studies aimed at improving cervical cancer screening uptake have focused on women, data are sparse regarding men’s knowledge, perceptions, and support related to cervical cancer screening completion; and this data gap extends to SSAI men in the U.S. To address this gap a qualitative descriptive study was conducted among SSAI men to assess knowledge, perceptions, and support related to cervical screening among SSAI men.

This exploratory study focused on (1) exploring SSAI men’s knowledge and awareness related to cervical cancer screening and (2) examining SSAI men’s perceptions and attitudes toward supporting wives/female partners’ uptake of cervical cancer screening.

Methods

Research design and sampling.

We used a qualitative descriptive research approach. A SSAI male community member (interviewer) who had undergone training in human subject protection was employed to recruit eligible males and conduct interviews. SSAI males were identified for study participation via purposive and snowball sampling. Participants introduced the interviewer and study to other eligible men. Participants were recruited primarily through word of mouth from the SSAI community in Lexington, Kentucky. Men were recruited from African organizations and stores. We used a maximum variation sampling method with attention to diversity of age, length of residence in the U.S., and marital status. Eligibility criteria for the study included the following: 1) male gender; 2) ≥ 21 years of age; 3) able to speak and understand English; 4) Sub- Saharan African-born and have a partner who is a SSAI woman; and 5) ability to provide informed consent to participate in the research study. Men meeting eligibility criteria were invited to participate in the study and a mutually agreeable time and venue (usually the participant’s home) was chosen for the interview. Data were obtained during in-depth one-on-one interviews using a socio-demographic questionnaire and a semi-structured interview guide. Interviews were conducted until saturation was reached (Creswell, 2012), which occurred after 21 interviews. All interview sessions were audio-recorded with permission and were conducted in a quiet, private environment that was mutually agreed upon by the participant and the interviewer. The average interview length was 45–60 minutes and participants received a thirty-dollar honorarium at the end of the interview.

Interview guide.

The interview guide was developed by the authors based upon an exhaustive literature review and using the Revised Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations as a framework (Andersen, 1995). This framework is useful for understanding health promotion and preventive service use among minority populations. The interview guide included questions addressing knowledge of cervical cancer screening and risks, decisions about cervical cancer screening, and support for wife/partner to obtain cervical cancer screening. Sample questions included “Can you discuss what you know about cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening?” and “Can you discuss how you will support your wife to complete cervical cancer screening?” After the questions about cervical cancer, cervical cancer screening, and HPV knowledge; men were provided with basic information about cervical cancer, cervical cancer screening, and HPV to provide them with accurate, contemporary, and evidence-based facts on these topics. After being provided this information, the participants were asked questions focused on spousal/partner support and decision-making related to cervical cancer screening. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board prior to study commencement and confidentiality of records and personal information was maintained.

Data management and analysis.

All 21 digitally recorded interview audio files were professionally transcribed for subsequent analysis. One of the authors listened to the digital audio files twice while following each transcription to verify transcription accuracy. Transcripts were corrected as needed when any transcription error was detected. Data was analyzed using qualitative content analysis. Line-by-line coding was used to identify core categories of emerging findings. This coding involved aggregating the data text into small categories of information and assigning a label to the code (Creswell, 2012). Data were read word by word to derive codes by highlighting the exact words from the text that appear to capture key thoughts or concepts. The researchers developed code labels based on the interview guide, previous literature, and an initial review of the transcripts. The codes came directly from the text and then became the initial coding scheme. Next, the primary investigator made notes of first impressions, thoughts, and initial analysis. As this process continued, labels for codes emerged that are reflective of more than one key thought. Examples of individual codes included the following: inaccurate knowledge of cervical cancer screening, agreement to screen, woman’s health is paramount, enthusiasm to support, and individualized preference. Codes then were sorted into categories based on how the different codes were related and linked. The categories that emerged were used to organize and group the identified codes into meaningful data clusters. There were no pre-defined categories for grouping responses, but an inductive process allowed themes to emerge from the data. Two researchers jointly identified themes, resolved differences in coding, and selected quotations to support themes.

The researchers took several steps to insure the rigor and trustworthiness of the data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). First, data collection continued until saturation was reached when participants provided shared similar perspectives on the topic and no new ideas emerged. Second, the research team had prolonged immersion and engagement with the data. Analysis required multiple readings and was conducted by two independent researchers to assure trustworthiness. To establish credibility, member checking was used to verify the accuracy and the interpretation of the data that were provided (Creswell, 2012). Four study participants were contacted and provided with a summary of the preliminary findings and descriptions of themes to determine whether the summary accurately portrayed data interpretation.

Results

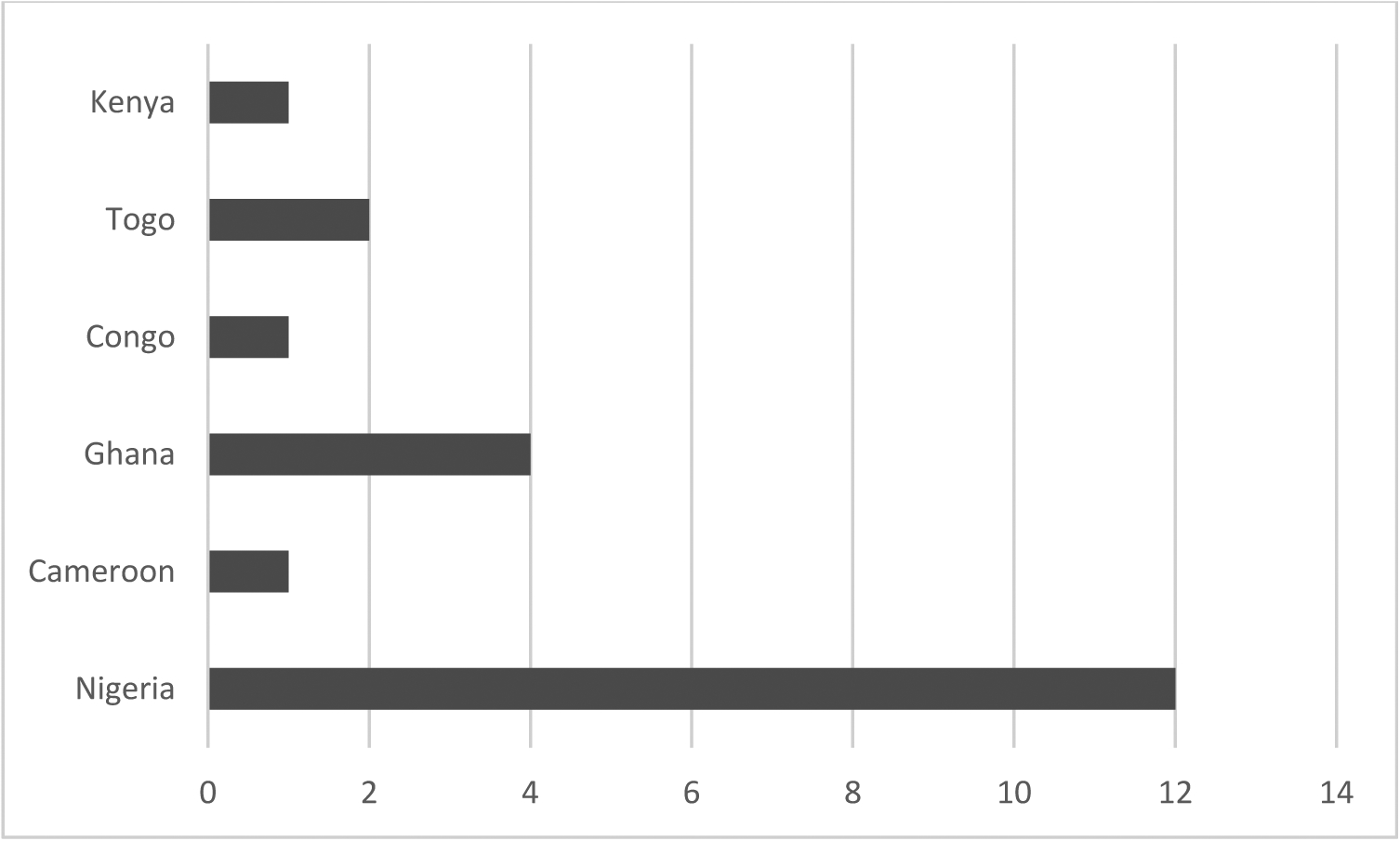

Twenty-one SSAI men participated in this study. Demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 36.2 years (SD= 9.0). Most of the men reported they were married (62%), college educated (88%), had resided in the U.S. for more than 5 years (53%), worked full time (81%), made enough income to “make ends meet” (91%), and had health insurance (86%). The countries of origin of participants are shown in figure 1.

Table 1:

Demographics characteristics of participants (N =21)

| Variable | Mean (SD) or N (%)* |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36.2 (9.0) |

| Year in the US | |

| ≤ 5years | 10 (47%) |

| >5years | 11 (53%) |

| Marital status | |

| Currently married/unmarried living together | 13 (62%) |

| Single (never married) | 5 (24%) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 3 (14%) |

| Education | |

| High school completed | 2 (10%) |

| College degree | 10 (48%) |

| Post graduate degree | 9 (43%) |

| Health insurance | |

| Yes | 18 (86%) |

| No | 3 (14%) |

| Enough income to make ends meet | |

| Yes | 19 (91%) |

| No | 2 (10%) |

| Income | |

| ≤ $24,999 | 5(24%) |

| $25,000–34,999 | 3 (14%) |

| $35,000–49,999 | 3 (14%) |

| >$50,000 | 9 (43%) |

Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding up to whole numbers

Figure 1:

SSAI male participants’ countries of birth

Three primary themes were derived from the analysis of these individual interview discussions: (1) inadequate knowledge and awareness of cervical cancer; (2) strategies for support; (3) shared versus autonomous decision making regarding screening. Each theme is described below and representative quotes are provided.

Theme 1. Inadequate knowledge and awareness of cervical cancer.

SSAI men displayed some knowledge of cervical cancer. Most men were aware of the female cervix as a part of female anatomy and hence could identify cervical cancer as being a female cancer. One participant stated: “I do not really know anything about cervical cancer; maybe it is the cancer of the cervix” (28-year-old, single male).

Some participants had limited knowledge and awareness of cervical cancer screening. Most men in this study were unfamiliar with cervical cancer screening, simply indicating that they had no knowledge when asked about cervical cancer screening. When queried about cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening, one man stated, “I believe is that kind of cancer that is peculiar to women. It is usually found in their private part. I am not very familiar with the screening” (36-year-old divorced male). Another participant stated, “cervical cancer is inflammation in the cervix” (32-year- old married male). Most men were unsure of the purpose of cervical cancer screening and its role in cervical cancer detection.

Overall, participants demonstrated little or no knowledge of HPV. Participants could not identify HPV infection as a primary risk factor for cervical cancer. One man stated: “I have heard about HPV, not really sure what it is and how it relates to cervical cancer, but I think it requires our attention” (41-year-old married male). Overall knowledge of risk factors for cervical cancer was relatively low except for two participants with a background of medical training. Inaccurate cervical cancer risk factors identified by study participants included unhygienic practices and improper cleaning during and after menstruation. One man stated: “I know women when they have their monthly period it depends on how you take care of yourself. I can imagine if you don’t clean up or disinfect yourself properly, it may degenerate into things like that. I know infection could come from it. If infection could come from it, definitely it might go as bad as being cancerous” (48-year-old married man).

Participants had little knowledge of screening recommendations for cervical cancer. Despite low overall knowledge of cervical cancer risks, most men interviewed could speculate that there is a link between having multiple sex partners and cervical cancer. All participants believed that cervical cancer is an important health concern for women.

Theme 2. Strategies for Support.

While the men were largely unaware of cervical cancer screening guidelines, they were supportive of their wives completing the screening. They were generally enthusiastic about supporting their wives to complete cervical cancer screening according to guidelines. Several participants emphasized that preservation of their wives’ health is paramount to the welfare of the family because of the indispensable role women play in the home. Some of this support was informed by men’s need to preserve their own health. One participant noted: “I don’t want to contract anything, if there is any problem down there and she is my wife and we have intercourse without condom, I can contract something, so it is best for her to get checked to make sure everything is fine” (30 year-old married man).

Most men acknowledged that they would need to improve their knowledge about cervical cancer screening to provide necessary support. One man stated: “we have to know what it involves and entails, use that knowledge to let women know that this is a preventable condition” (47-year-old married man). Another man noted: “Awareness is key. Most individuals are not aware. It’s about being involved, knowing what is happening, and to be aware of preventive options and treatment options” (29 year-old single man).

Participants indicated that they will initiate discussions about cervical cancer screening with their wives. Several participants noted that their wives are more knowledgeable and proactive when it comes to health conditions but their wives are often too busy with other things to prioritize their health. SSAI men described different ways to encourage their wives/partners, such as scheduling cervical cancer screening appointments, keeping appointment reminders, and accompanying their wife/partner to her appointment. One man mentioned, “I will make sure she sees the doctor, know when the next appointment is, we keep it on the fridge, we make sure we don’t forget, put the alarm on the phone and make sure that whenever that date is near you know we will be telling each other how to work things out and make sure she has free time to go and do what is necessary because health is very important, people die a lot from not knowing what is supposed to be” (41-year-old married man).

Several men described that despite financial constraints they would not mind spending money on health because it is an investment that pays off. Other men noted that they are willing to provide support in other ways. One man stated: “I will support her by not forcing her to go for screening, try to explain to her the importance of screening, persuade her to get screened and I will also check regularly if there is something I need to do” (34 year-old married man).

Overall SSAI men showed promising attitudes toward supporting their wives’ cervical cancer screening uptake. Most men discussed that they will provide emotional, mental, and moral support as necessary to ensure their wives completion of cervical cancer screening.

Most SSAI men emphasized the importance of traditional gender roles and the need for men to be role models of health in their homes. Participants discussed that men should take the lead on the family’s health and know how to handle female-related health needs. To effectively fulfill this role, participants discussed the need for men to be abreast of information regarding cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening. One of the interviewees stated: “We need to involve men; we don’t need to talk only to the woman that they have to do it. They need their partners. We need to make sure men are educated. Lack of education on their part prevents them from supporting their woman.” (50-year-old married man).

Theme 3. Shared versus autonomous decision making regarding screening.

Several participants discussed that they use a collaborative family-oriented approach based on the best interest of the family when making decisions about preventive screenings. However, the men indicated that wives do not need to seek approval or permission to complete cervical cancer screening or other preventive services. One man stated: “This is something we should discuss. I don’t like that word permission or approval. This test is important for my wife; I don’t want to lose my wife, so why should she seek approval to care of her health” (47-year-old married male). Another man opined: “It is your husband, it is not a permission to ask, it is something you need to tell your husband, I know it may be hard on the woman, but your husband has the right to know just in case there is a problem, he needs to know about it. It is something you need to sit down and talk to him about it” (35-year-old married man).

Several SSAI men suggested that their wives should be proactive about their health by making autonomous decisions related to completing preventive screenings. The men noted that women should have the final say when it comes to issues related to women’s health. One man stated: “It is not for the man to decide because if something happens to woman, God forbids that she dies, the man will get someone else. It is her life; she has to take care of herself” (47-year-old married male).

Several men discussed that they would like their partners to inform them when making cervical cancer screening decisions, but that the onus lies on the woman to decide if she will share this information. One man indicated that “you should be smart enough to decide your own health for yourself, and then carry your partner along” (41-year-old married man). All the participants want to be informed and involved in the cervical cancer screening decision-making process in some way.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the knowledge, perceptions, and support of SSAI men for cervical cancer screening for their female partners. SSAIs are a collective society and the findings from this study can provide researchers and practitioners with important perspective to base interventions and recommendations for SSAI families surrounding cervical cancer screening. Several important findings emerged from this study in this regard. First, while SSAI men have limited knowledge regarding cervical cancer screening guidelines, they expressed willingness to support their partners completion of cervical cancer screening and identified several strategies to do so. This is consistent with results from a study among urban men in Ghana in which African men expressed willingness to provide spousal support for cervical cancer screening if they had more information about cervical cancer and the screening methods (Williams & Amoateng, 2012). Similarly, a study among Hispanic men found that men are interested in learning more about cervical cancer to support their partners’ health care seeking efforts (Fernandez et al., 2009).

The SSAI men in this study discussed three different dimensions of support to assist their partners which included emotional support (provision of empathy, love, trust, and caring), instrumental support (provision of tangible assistance that directly helps a person), and informational support (provision of advice, suggestions, and information that a person can use to address problems) (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2008). Many expressed that their support is important for their partners to maintain good health as individuals and as a family. SSAI men are willing to provide emotional support to help their partners cope with possible discomfort from cervical cancer screening and willing to accompany their partners to cervical cancer screening appointments. Some participants mentioned financial provision for cervical cancer screening indicating willingness to provide instrumental support to their partners. Pain and financial constraints are commonly identified barriers to cervical cancer screening (Adegboyega & Hatcher, 2016, Ghebre et al., 2014, Ndukwe et al., 2013); therefore, support to alleviate or reduce these barriers may improve cervical cancer screening uptake among SSAI women. Given SSAI men’s enthusiasm to support their wives to undergo cervical cancer screening, future interventions should involve male partners. Health education and awareness programs on women’s health needs should include and engage men to reinforce male partners’ roles in cervical cancer screening uptake and prevention. Community engaged research efforts should be family-based rather than individually focused and should leverage the collective culture of the SSAI community to focus on this important strength. The effectiveness of this type of intervention in improving screening was demonstrated in a couples’ intervention conducted to promote breast cancer screening for Korean Americans. The intervention group was twice as likely to get a mammogram at 15 months follow up when compare with the attention control group (Lee et al., 2014)

Specific knowledge about cervical cancer screening and HPV was lacking among the majority of participants. A few of the men in this study were introduced to the term “cervical cancer screening” for the first time during the interview. Our findings showed that SSAI men frequently held some inaccurate beliefs about cervical cancer’s etiology and risk factors. These findings are similar to previous studies among immigrant populations that suggest knowledge deficits related to cervical cancer risk factors and cervical cancer screening and deficits in immigrant males’ knowledge related to female cancers (Corcoran & Crowley, 2014, Kue, Zukoski, Keon, & Thorburn, 2014, Ndukwe et al., 2013, Thiel de Bocanegra et al., 2008; Treviño, Jandorf, Bursac, & Erwin, 2012). While there is a high level of willingness to provide needed support for their partners, the lack of knowledge and awareness about cervical cancer and HPV’s causative role may negatively impact men’s approach in providing support.

One possible reason for the limited knowledge about cervical cancer risk and screening among SSAI men may be related to the fact that most information and campaigns about cervical cancer primarily target women and there is a lack of emphasis on the role that men may play in decreasing cervical cancer incidence. However, studies among SSAI women have demonstrated equally limited knowledge and awareness related to these topics (Brown, Wilson, Boothe, & Harris, 2011, Harcourt et al., 2013, Ndukwe et al., 2013). It is probable that because women’s gynecological health issues were often not discussed openly in sub-Saharan African countries, it was difficult for SSAI women to initiate discussions on sexuality, cancer screening, or reproductive health (Ogunsiji, Wilkes, Peters, & Jackson, 2013) with their partners, contributing to the knowledge deficit among SSAI men. Limited knowledge of HPV and its link with cervical cancer have been reported in studies among native Africans (Assoumou et al., 2015, Francis et al., 2010, Getahun, Mazengia, Abuhay, & Birhanu, 2013). It is plausible that knowledge gaps may be related to the lack of screening emphasis in most sub-Saharan African countries. Until recently, little attention was given to cervical cancer screening programs in sub- Saharan Africa (Lim & Ojo, 2016). Inadequate knowledge and inaccurate beliefs about cervical cancer etiology and HPV may influence how men make informed decision about cervical cancer prevention, including HPV vaccination for their eligible children and safe sex. Without accurate information about women’s gynecological health related to HPV and cervical cancer, SSAI men may put their wives at greater risk for HPV infection and cervical cancer.

In many cultures, husbands serve as the gatekeeper of their wives’ health (WHO, 2006). When this is the case, a lack of knowledge about cervical cancer risk factors and cervical cancer prevention may pose a significant barrier to the men becoming positively involved and supportive. A study among married Nigerian men reported a linear relationship between practices encouraging wives to obtain cervical cancer screening and the husbands’ cervical cancer knowledge (Suzu, Elizabeth & Adejumo, 2014). This underscores the importance of relevant and comprehensive cervical cancer knowledge and awareness (Suzu et al., 2014).

Considering these findings, interventions to increase the SSAI population’s knowledge and awareness of the importance of cervical cancer screening are warranted. Such interventions should target SSAI males and females. Health promotion programs should include culturally relevant educational initiatives and public health awareness campaigns. Cervical cancer screening messages should include information about cervical cancer risk factors, cervical cancer screening guidelines, and the importance of male support in cervical cancer prevention and screening. Such campaigns can help eliminate anecdotal beliefs, inform cervical cancer screening support, and emphasize the significant role that men play in cervical cancer prevention.

Social support is one essential function that social networks including marital relationships provide (Glanz et al., 2008) and may be an integral component of improving cervical cancer screening engagement among SSAI women. Family is a major part of the social support network (Hou, 2006). The presence of strong social networks often facilitates the acquisition of health care (Sheppard, Christopher, Nwabukwu, 2010) and promotes engagement in healthy behaviors such as cervical cancer screening. Studies among SSAI women indicate that family support is a crucial motivator that might encourage SSAI women to participate in cervical cancer screening (Adegboyega & Hatcher, 2016). A study among Chinese women found that women who perceived higher spousal support had more positive beliefs about cervical cancer screening; including perceived higher benefits, lower barriers, and higher norms (Hou, 2006).

Patriarchal attitudes and deep-rooted stereotypes regarding the roles and responsibilities of women and men in the family can limit women’s control over their sexual and reproductive health (Women and Health: United Nations, 1995). SSAI men play a salient role in preventive health care decisions in their families. Decision-making autonomy is an important determinant in the uptake of women’s health services such as cervical cancer screening. Unfortunately, power imbalances within family relationships can interfere with women’s ability to access health care services (Blanc, 2001). Women’s lack of decision-making power can limit their access to health care and negatively affect maternal health outcomes (Women and Health: United Nations, 1995).

A final noteworthy finding from this study is the shared decision-making model that was proposed by most of the males. SSAI men refuted the notion that their partners need to seek their permission for cervical cancer screening. Most men noted that they encourage shared or collaborative decision-making for preventive health care services such as cervical cancer screening while others preferred their partners make such decisions autonomously but keep them informed. Previous studies have shown that shared decision-making between husband and wives may yield better health outcomes than men making decisions alone or women making decisions without partner input or agreement (Rao, Esber, Turner, Chilewani, Banda, & Norris, 2016, Story & Burgard, 2012). It is critical that practitioners and researchers understand this family decision making model when promoting cervical cancer screening in this population. One way to incorporate this family decision making model is by involving men in cervical cancer interventions and counseling. The decision to screen should be made by couples, after couples have been counseled on cervical cancer risk factors, potential benefits and harms of screening and additional follow up that may be needed after screening. By incorporating SSAI men in decision making, men can support their partners’ cervical cancer screening and proper follow-up.

Limitations

Findings from this study should be interpreted taking the research limitations into consideration. The findings are not generalizable to all SSAI men due to the study design and use of a purposeful sampling. It is plausible that social desirability and response bias might have played a role in the responses from the men interviewed.

Conclusions

This is one of the few studies among SSAI men focusing on their knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes related to cervical cancer screening. Findings suggest that gaining men’s support through education, advocacy, and involvement in cervical cancer screening within their socio-cultural norms would enable men to make informed decisions regarding partners’ cervical cancer screening. In African cultures, men still play a dominant role in the family. This social structure with emphasis on male leadership could be leveraged in health promotion interventions designed to improve cervical cancer screening engagement for SSAI women.

The findings of this study should prompt researchers to consider male involvement as an integral part of family-based culturally tailored interventions to improve cervical cancer screening rates among SSAI population. Such interventions might include navigation assistance for SSAI families to explore barriers to cervical cancer screening, engagement with women to gain spousal support, and connecting women with preferred providers offering cervical cancer screening services.

Acknowlegdements

We would like to thank all SSAI men who volunteered to participate in this study for their insight and time. We would like to thank Mr. Femi Ajayi for conducting the interviews. This work was supported by Geographical Management of Cancer Health Disparities Program (GMaP) region 1North (National Cancer Institute Grant # 3P30CA177558-04S3) and in part by Disparities Researchers Equalizing Access for Minorities (DREAM) center, College of Nursing, University of Kentucky. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the GMAP or University of Kentcuky.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Adegboyega A, & Hatcher J (2016). Factors influencing Pap screening use among African immigrant women. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 28(5), 479–487. 10.1177/1043659616661612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assoumou SZ, Mabika BM, Mbiguino AN, Mouallif M, Khattabi A, & Ennaji MM (2015). Awareness and knowledge regarding of cervical cancer, Pap smear screening and human papillomavirus infection in Gabonese Women. BMC Women’s Health, 15(1), 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham A, Bishop A, Coffey P, Winkler J, Bradley J, Dzuba I, & Agurto I (2003). Factors affecting utilization of cervical cancer prevention services in low-resource settings. Salud Publica de Mexico, 45, 408–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc AK (2001). The effect of power in sexual relationships on sexual and reproductive health: an examination of the evidence. Studies in Family Planning, 32(3), 189–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR, Wilson RM, Boothe MA, & Harris CE (2011). Cervical cancer screening among ethnically diverse black women: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices. J National Medical Association, 103(8), 719–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparetto C, & Borruto F (2015). Cervical cancer screening: A never-ending developing program. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 3(7), 614–624. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i7.614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran J, & Crowley M (2014). Latinas’attitudes About Cervical Cancer Prevention: A Meta-Synthesis. Journal Of Cultural Diversity, 21(1), 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez ME, McCurdy SA, Arvey SR, Tyson SK, Morales-Campos D, Flores B, Useche B, Mitchell-Bennett L, Sanderson M (2009). HPV knowledge, attitudes, and cultural beliefs among Hispanic men and women living on the Texas-Mexico Border. Ethnicity and Health, 14(6), 607–624. doi: 10.1080/13557850903248621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forney-Gorman A, & Kozhimannil K (2015). Differences in cervical cancer screening between African-American versus African-born Black women in the United States. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0267-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis SA, Nelson J, Liverpool J, Soogun S, Mofammere N, & Thorpe RJ (2010). Examining attitudes and knowledge about HPV and cervical cancer risk among female clinic attendees in Johannesburg, South Africa. Vaccine, 28(50), 8026–8032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getahun F, Mazengia F, Abuhay M, & Birhanu Z (2013). Comprehensive knowledge about cervical cancer is low among women in Northwest Ethiopia. BioMed Central cancer, 13(1), 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebre RG, Sewali B, Osman S, Adawe A, Nguyen HT, Okuyemi KS, & Joseph A (2014). Cervical Cancer: Barriers to screening in the Somali community in Minnesota. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0080-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Viswanath K (2008). Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt N, Ghebre RG, Whembolua GL, Zhang Y, Warfa Osman S, & Okuyemi KS (2013). Factors associated with breast and cervical cancer screening behavior among African immigrant women in Minnesota. Journal of Immigrant Minority Health. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9766-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou SI (2006). Perceived spousal support and beliefs toward cervical smear screening among Chinese women. Californian Journal of Health Promotion, 4(3), 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Song M, Kigen O, Jennings Y, Nwabukwu I, & Sheppard VB (2014). Addressing cancer control needs of African-born immigrants in the US: A systematic literature review. Preventive Medicine, 67c, 89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isa Modibbo F, Dareng E, Bamisaye P, Jedy-Agba E, Adewole A, Oyeneyin L, … Adebamowo C (2016). Qualitative study of barriers to cervical cancer screening among Nigerian women. British Medical Journal Open, 6(1). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambarami M (2006). Femininity, sexuality and culture: Patriarchy and female subordination in Zimbabwe. South Africa: Africa Regional Sexuality Resource Center. [Google Scholar]

- Kue J, Zukoski A, Keon KL, & Thorburn S (2014). Breast and cervical cancer screening: Exploring perceptions and barriers with Hmong women and men in Oregon. Ethnincity and Health, 19(3), 311–327. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2013.776013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Menon U, Nandy K, Szalacha L, Kviz F, Cho Y,Miller A, & Park H (2014). The effect of couples intervention to increase breast cancer screening among Korean Americans. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(3), E185–E193. 10.1188/14.ONF.E185-E193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EE, Tripp-Reimer T, Miller AM, Sadler GR, & Lee S-Y (2007). Korean American women’s beliefs about breast and cervical cancer and associated symbolic meanings. Oncology Nursing Forum, 34(3), 713–720. 10.1188/07.ONF.713-720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, & Ojo A (2016). Barriers to utilisation of cervical cancer screening in Sub Sahara Africa: a systematic review. European Journal of Cancer Care, 26 (1), e12444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyimo FS, Beran TN. Demographic, knowledge, attitudinal, and accessibility factors associated with uptake of cervical cancer screening among women in a rural district of Tanzania: Three public policy implications. BioMed Central Public Health. 2012;12:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makama GA (2013). Patriarchy and gender inequality in Nigeria: the way forward. European Scientific Journal, 9(17). [Google Scholar]

- Ndukwe E, Williams K, & Sheppard V (2013). Knowledge and perspectives of breast and cervical cancer screening among female African immigrants in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area. Journal of Cancer Education, 1–7. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0521-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunsiji O, Wilkes L, Peters K, & Jackson D (2013). Knowledge, attitudes and usage of cancer screening among West African migrant women. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(7–8), 1026–1033. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder LF, Nelson BD, Eckardt M, & Goodman A (2016). A public health priority: Disparities in gynecologic cancer research for African-born omen in the United States. Clinical Medicine Insights. Women’s Health, 9, 21–26. doi: 10.4137/CMWH.S39867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao N, Esber A, Turner A, Chilewani J, Banda V, & Norris A (2016). The impact of joint partner decision making on obstetric choices and outcomes among Malawian women. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 135(1), 61–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond NC, Osman W, O’Brien JM, Ali N, Kia F, Mohamed F, Mohamed A, Goldade K, Pratt R,& Okuyemi K (2014). Culturally informed views on cancer screening: a qualitative research study of the differences between older and younger Somali immigrant women. BioMed Central Public Health, 14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser JI, Zakaras JM, Hamisi S, & Huchko MJ (2014). Men’s knowledge and attitudes about cervical cancer screening in Kenya. BioMed Central women’s health, 14(1), 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewali B, Okuyemi KS, Askhir A, Belinson J, Vogel RI, Joseph A, & Ghebre RG (2015). Cervical cancer screening with clinic-based Pap test versus home HPV test among Somali immigrant women in Minnesota: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Cancer Medicine, 4(4), 620–631. doi: 10.1002/cam4.429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story WT, & Burgard SA (2012). Couples’ reports of household decision-making and the utilization of maternal health services in Bangladesh. Social Science & Medicine, 75(12), 2403–2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzu CA, Elizabeth A-O, & Adejumo A (2014). Husbands’knowledge, attitude and behavioural disposition to wives screening for cervical cancer In Ibadan. African Journal for The Psychological Studies of Social Issues, 17(2), 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor VM, Yasui Y, Nguyen TT, Woodall E, Do HH, Acorda E, … Jackson JC (2009). Pap smear receipt among Vietnamese immigrants: the importance of health care factors. Ethinicty and Health, 14(6), 575–589. doi: 10.1080/13557850903111589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel de Bocanegra H, Trinh-Shevrin C, Herrera AP, & Gany F (2008). Mexican immigrant male knowledge and support toward breast and cervical cancer screening. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 11(4), 326–333. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9161-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treviño M, Jandorf L, Bursac Z, & Erwin DO (2012). Cancer screening behaviors among Latina women: the role of the Latino male. Journal of Community Health, 37(3), 694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui J, Saraiya M, Thompson T, Dey A, & Richardson L (2007). Cervical cancer screening among foreign-born women by birthplace and duration in the United States. Journal Womens Health (Larchmt), 16(10), 1447–1457. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States.Preventive Services Task Force. September 2016. Final update summary: cervicalcancer:Screening.https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening. [Google Scholar]

- Williams M, & Amoateng P (2012). Knowledge and beliefs about cervical cancer screening among men in Kumasi, Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal, 46(3), 147–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2006). Comprehensive cervical cancer control: a guide to essential practice: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Women and Health: United Nations. Sozial- und Praventivmedizin (1995) http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/beijingat10/C.%20Women%20and%20health.pdf. [Google Scholar]