Summary

Spinal long-term potentiation (LTP) at C-fiber synapses is hypothesized to underlie chronic pain. However, the causal link between spinal LTP and chronic pain is still lacking. Here we report that high frequency stimulation (HFS, 100 Hz, 10 V) of the mouse sciatic nerve reliably induces spinal LTP without causing nerve injury. LTP-inducible stimulation triggers chronic pain lasting for > 35 d and increases the number of calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) terminals in spinal dorsal horn. The behavioral and morphological changes can be prevented by blocking NMDA receptors, ablating spinal microglia, or conditionally deleting microglial BDNF. HFS-induced spinal LTP, microglial activation, and upregulation of BDNF are inhibited by antibodies against colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1). Together, our results show that microglial CSF1 and BDNF signaling is indispensable for spinal LTP and chronic pain. The microglia dependent transition of synaptic potentiation to structural alterations in pain pathways may underlie pain chronicity.

Keywords: Long-term potentiation, Chronic pain, Calcitonin gene-related peptide, Microglia, High frequency stimulation, Colony stimulating factor 1, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

Introduction

Chronic pain manifests as allodynia (decreased pain threshold), hyperalgesia (increased pain response) and spontaneous pain. Chronic pain affects about 20% of the population and results in a significant expenditure of healthcare resources (Yekkirala et al., 2017). The main mechanisms underlying pathological pain include hypersensitivity of nociceptors and persistent increases in synaptic transmission within pain pathways (Liu and Zhou, 2015). However, as the conditions that induce chronic pain are often associated with peripheral nerve degeneration and local inflammation, it is not clear whether persistent synaptic potentiation alone is sufficient to result in chronic pain.

Long-term potentiation (LTP) at C-fiber synapses in the spinal dorsal horn (SDH) induced by high frequency stimulation (HFS) of the peripheral nerve is considered a synaptic model of pathological pain (Liu and Zhou, 2015). Indeed, spinal LTP and nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain share many common mechanisms (Sandkuhler and Gruber-Schoffnegger, 2012). In particular, both depend on N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors (Liu and Sandkuhler, 1995; Seltzer et al., 1991). In human volunteers, HFS at skin nociceptors is shown to produce mechanical allodynia and secondary hyperalgesia lasting for hours or even days in some cases (Pfau et al., 2011). In rats, HFS (0.5 ms, 40 V, 10 trains of 2-sec at 100 Hz with 10-sec intervals) at the sciatic nerve produces mechanical allodynia persisting for at least 35 days, but also damages the stimulated nerve (Liang et al., 2010). To date, evidence of a causal link between spinal LTP and chronic pain is still lacking.

In response to peripheral nerve injury or inflammation, microglia, the principal immune cell, transform from a ramified to a reactive state and release a repertoire of proinflammatory factors that lead to pain hypersensitivity (Gu et al., 2016; Inoue and Tsuda, 2018; Peng et al., 2016; Zhuo et al., 2011). Several studies have shown that microglial activation is involved in HFS-induced LTP and can even regulate synaptic strength independent of neuronal activity (Clark et al., 2015; Gruber-Schoffnegger et al., 2013; Kronschlager et al., 2016; Zhong et al., 2010). However, it is still unclear whether microglia participate in spinal plasticity and pain hypersensitivity in the absence of nerve injury.

In the present study, we report that induction of spinal LTP at C-fiber synapses by HFS that does not injure the stimulated nerve and leads to long-lasting mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in mice. Using transgenic mice to either genetically ablate microglia or specifically knock out microglial BDNF, we determined that HFS at the sciatic nerve activates spinal microglia via colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1,namely, macrophage colony stimulating factor) signaling, which in turn releases BDNF from microglia to increase calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) terminals in SDH. Increases in CGRP terminals underlie long-lasting pain hypersensitivity. These findings may explain how chronic pain occurs in the absence of injury or disease, a state recently classified as chronic primary pain by the World Health Organization (Treede et al., 2015).

Results

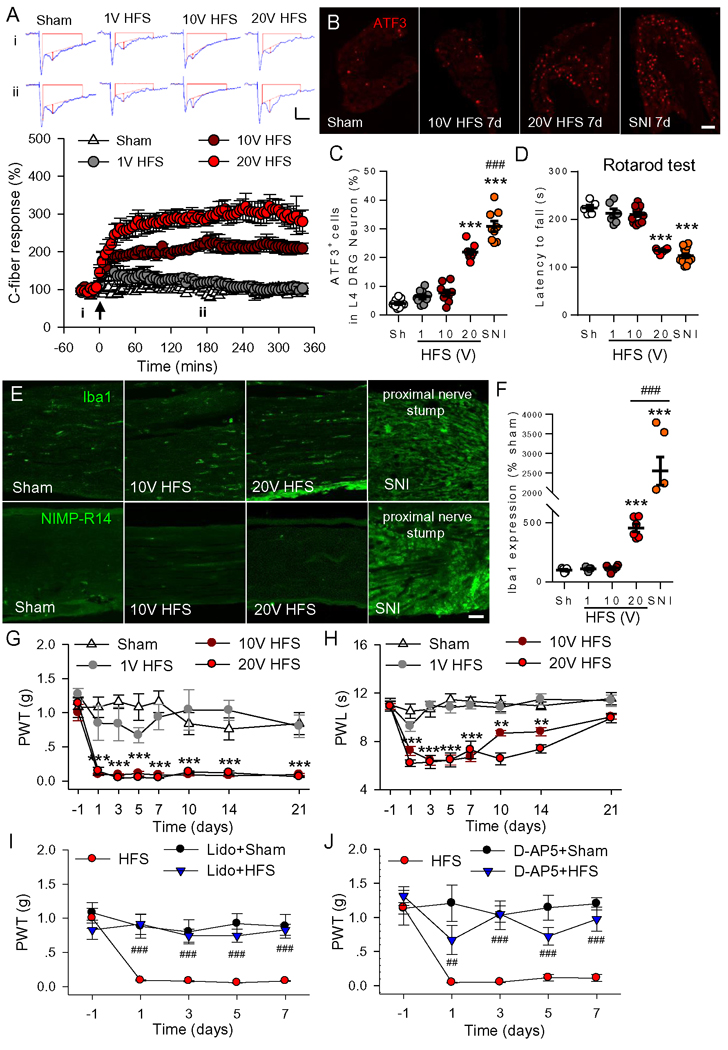

High frequency stimulation induces chronic pain without detectable injury of stimulated nerve

It has been proposed that spinal LTP at C-fiber synapses, induced by HFS, may underlie chronic pain (Liu and Zhou, 2015). However, HFS may also induce chronic pain through injury of the stimulated nerve (Liang et al., 2010). To explore the causal relationship between spinal LTP and chronic pain, a certain stimulation protocol that reliably induces LTP but does not damage the stimulated nerve was first characterized. To this end, we modulated the intensity of HFS and examined the corresponding changes in spinal LTP induction and potential nerve damage in mice. We found that HFS (100 pulses of 0.5 ms at 100 Hz, repeated 4 times at a 10 s interval) of the sciatic nerve at both 10V and 20V but not at 1V induced LTP of C-fiber-evoked field postsynaptic excitatory potentials (fEPSPs) (Figure 1A). To determine whether the stimulation protocols may damage sensory neurons, we performed immunofluorescent analysis to detect ATF3-positive nuclei, a well-established injury marker, in L4 dorsal root ganglion (DRG) after electrical stimulation. ATF3 was significantly increased in the mice receiving 20V HFS or spared nerve injury (SNI) surgery. However, neither 10V nor 1V of HFS caused ATF3 upregulation (Figure 1B and 1C). Compared to the sham group, the latencies to fall in rotarod test, which evaluates motor function, was significantly decreased in the 20V HFS and SNI groups at 7 days after surgery, but not in the 10V HFS group (Figure 1D). Since subtle damage to the nerve may attract pronociceptive immune cells, we examined resident macrophages (stained by Iba1) and neutrophils (by NIMP-R14) in 10V HFS-stimulated sciatic nerve at 7 days after HFS. Compared with the sham group, there was no significant change in Iba1 in stimulated sciatic nerves (Figure 1E and 1F). NIMP-R14 neutrophils were not detected in sham and HFS groups. In contrast, these immune cells were activated or infiltrated in the proximal sciatic nerve stump or the connective tissue in SNI mice. Together, these results indicate that 10V HFS induces spinal LTP but does not result in injury or inflammation in the stimulated nerve.

Figure 1. HFS that does not injury the stimulated sciatic nerve induces spinal LTP and chronic pain hypersensitivity in mice.

(A) Spinal LTP at C-fiber synapses was induced by HFS at 10 and 20 V but not at 1V. The representative traces of C-fiber evoked fEPSPs were recorded before (i) and 3 h (ii) after high frequency stimulation (HFS) of the sciatic nerve at different intensities. Amplitude of C-fiber evoked fEPSPs (red vertical line) was determined automatically by parameter extraction software of WinLTP. Scale bars: x =100 ms, y = 0.2 mV. Summary data of the C-fiber responses expressed as mean ± SEM plotted vs. time were shown below (n = 6 mice/group). The arrow indicates the time point at which HFS was delivered. (B, C) Representative images and summary data show the expression of ATF3 in L4 DRG neurons 7 days after HFS at different intensities and 7 days after spared nerve injury (SNI). Scale bar, 100 μm. n = 3–4 mice/group, 3 slices/mouse, ***P < 0.001, compared with sham group, ###P < 0.001 vs. 20V HFS, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test. (D) The latencies to fall in rotarod test in different groups at 7 days after HFS at different intensities or SNI are shown. n = 5–12 mice for each group, ***P < 0.001, compared with sham group, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test. (E) Immunofluorescence of Iba1 (a marker for resident macrophage) and NIMP-R14 (a marker for neutrophil) in the stimulated sciatic nerve from different groups at 7days after HFS or SNI are shown (n = 3 mice/group, 2–3 sections/mouse). Scale bar: 50 μm. (F) Quantification of Iba1 expression in the sciatic nerve. ***P < 0.001, compared with sham group, ###P < 0.001 vs. 20V HFS, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test. (G, H) HFS at 10V and 20V significantly decreased 50% paw withdrawal threshold (PWT, G) to von Frey filaments and paw withdrawal latency (PWL, H) to radiant thermal stimuli, compared with the sham group or 1V HFS (n = 12 mice for 10V HFS group, n = 5–6 mice for other groups, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. sham group, two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test). (I) The decrease in mechanical thresholds induced by 10 V HFS was prevented by local application of 2% lidocaine (50 μl) at the stimulated sciatic nerve 15 min before HFS (n = 5–7 mice/group). ###P < 0.001 vs. HFS group, two-way ANOVA with Fisher LSD’s test. (J) Intrathecal injection of NMDA receptor antagonist D-AP5 (50 μg/ml, 5 μl) but not vehicle (Vehi, PBS) 30 min before HFS abolished HFS-induced mechanical hypersensitivity (n = 6–8 mice/group). ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. vehicle group, two-way ANOVA with Fisher LSD’s test.

To determine if HFS is capable of inducing chronic pain, behavioral tests were performed in mice receiving HFS at different intensities. Compared with sham control, HFS at 20 V and 10V but not at 1V led to a reduction in paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) with mechanical stimuli (mechanical allodynia) (Figure 1G) and in paw withdrawal latency (PWL) with thermal stimuli (thermal hyperalgesia) (Figure 1H). The mechanical allodynia and the thermal hyperalgesia induced by 10V HFS lasted for > 21 days and around 14 days, respectively.

HFS may induce numerous changes in the stimulated nerve. To rule out other changes that may contribute to chronic pain hypersensitivity, we blocked action potential conduction in the sciatic nerve with lidocaine (a sodium channel blocker, 2%, 50 μl) 15 min before HFS, and found that mechanical allodynia was completely blocked (Figure 1I). Spinal LTP is NMDA receptor-dependent (Liu and Sandkuhler, 1995). We found that intrathecal injection of the NMDA receptor antagonist D-AP5 (50 μg/ml, 5 μl, 253 nM) blocked spinal LTP without affecting the C-fiber evoked fEPSP baseline (Figure S1).This in turn prevented the HFS-induced allodynia (antagonist applied 30 min before 10V HFS; Figure 1J). These results indicate that spinal LTP is responsible for the chronic pain hypersensitivity.

We repeated the above HFS experiments in rats, a species also commonly used to test chronic pain. Interestingly, we found that 20V HFS at the rat sciatic nerve did not induce nerve injury (no ATF3 upregulation), but was able to induce spinal LTP, as well as chronic pain hypersensitivity (Figure S2A–D). Histological analyses using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) indicated that, unlike SNI, electrical stimulation of rat sciatic nerve at 20 V HFS did not induce Wallerian degeneration of myelinated nerve fibers and the atrophy of axons in myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibers (Figure S2E and S2F). Taken together, HFS-induced spinal LTP alone without nerve damage is sufficient to trigger chronic pain hypersensitivity in mice and rats. In further experiments, we investigated the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which spinal LTP underlie chronic allodynia using pharmacological and genetic tools and the 10 V HFS stimulation protocol.

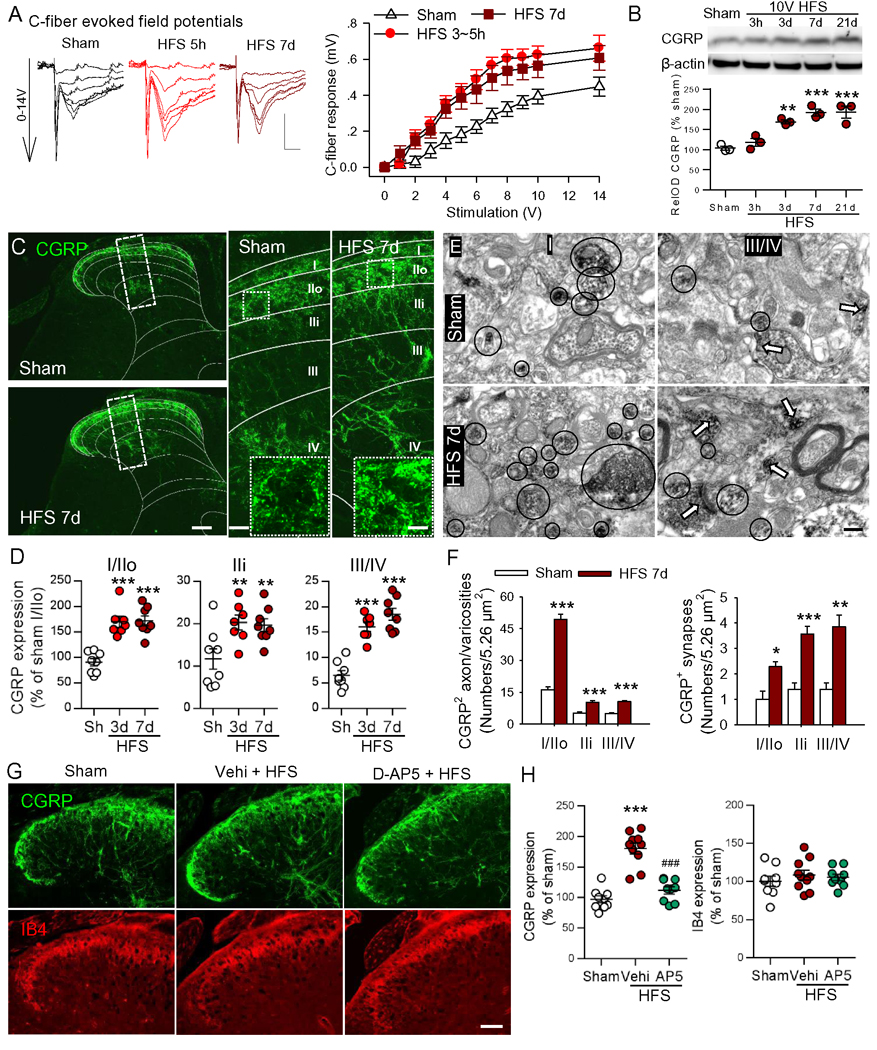

10 V HFS induces long-lasting functional and structural plasticity in the spinal dorsal horn

To address the cellular mechanism underlying the long lasting allodynia induced by short (4 s) electrical stimulation, we investigated the possibility of functional and structural plasticity in SDH after 10V HFS. To determine if the 10V HFS induces longlasing LTP, we investigated the input-output curves of C-fiber fEPSPs in the mice receiving HFS 3–5 h or 7–14 d before recordings, and found the curves shifted left in both groups compared to sham mice (Figure 2A). The data indicate that the spinal LTP induced by 10V HFS in mice can persist for more than 2 weeks.

Figure 2. HFS induces long-lasting synaptic potentiation and enhances CGRP terminals in SDH in a NMDA receptor-dependent manner.

(A) Original representative traces of fEPSP and the input/output curves (stimulation intensity/C-fiber response) demonstrated that synaptic efficacy was enhanced at 3–5 h or 7–14 days after 10 V HFS (n = 12 mice in sham and in HFS 3–5 h groups, n = 8 mice in HFS 7–14d group, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test). Scale bars: x = 50 ms, y = 0.2 mV. (B) Western blot assay illustrates the time course of changes in CGRP levels in the ipsilateral SDH following 10V HFS (n = 3–4 mice/group). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. sham group, one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test. (C) Representative confocal images of whole ipsilateral SDH (left) and magnified images (right) show the distributions of CGRP+ terminals 7 days after 10V HFS or sham operation. The laminae of SDH were shown by white lines. Representative higher-magnification images from dotted boxed regions in larger images show CGRP positive varicosities. Scale bars: 100 μm (left), 20 μm (right), 5 μm (right insert). (D) The histograms show the increased expression of CGRP+ terminals in different laminae of the ipsilateral SDH at 3 or 7 days after HFS (n = 3–4 mice/group, 2–3 sections/mouse). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with sham group, one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test. (E-F) Electron micrographs and the histograms show the CGRP-immunoreactive varicosities and synapses in the different laminae of the ipsilateral SDH in sham (n = 2 mice, 2–3 micrographs/laminae/mouse) and HFS groups (n = 3 mice, 2–3 micrographs/laminae/mouse). The black circles indicate CGRP+ varicosities and the white arrows CGRP+ synapses pointing from presynaptic to postsynaptic membrane. Scale bar: 200 nm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with sham group, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. (G, H) Double fluorescent images and the scatter diagrams show the expression of CGRP and IB4 in SDH at 7 days after 10V HFS with or without NMDA antagonist D-AP5 (AP5). Scale bar: 50 μm (left). n = 3 mice/group, n = 3–4 images/mouse. ***P < 0.001 compared with sham group, ###P < 0.001 vs. vehicle HFS group, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test.

To investigate the structural bases of the long-lasting synaptic potentiation initiated by 10 V HFS, the CGRP+ peptidergic and IB4+ nonpeptidergic C-fiber terminals in the dorsal horn were examined following 10V HFS. Western blots showed that CGRP was significantly upregulated at 3 d after HFS and the change persisted for > 21 d (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemical experiments showed that CGRP+ terminals in SDH were mainly located in lamina I and outer lamina II (IIo) in sham control mice. However, in mice treated with HFS the CGRP+ terminals were dramatically increased in both superficial and deep laminae of SDH (Figures 2C and 2D). Serial spinal coronal sections showed that at 7 d after HFS, CGRP expression was markedly upregulated in the ipsilateral L4–6 spinal dorsal horn, where sciatic nerve roots carry sensory input. Furthermore, the upregulation of CGRP was also extended to the ipsilateral L3 and S1 spinal dorsal horn (Figure S3).

As the peptidergic terminals communicate with dorsal horn neurons by both volume transmission (via release of bioactive substances from varicosities) and by classical synaptic transmission (Borroto-Escuela et al., 2015), we employed pre-embedding immunoelectron microscopy (IEM) to test for changes in CGRP+ varicosities and synapse numbers in SDH. We found that both of synapse number and varicosities were increased in lamina I-IV at 7 d after HFS, compared to the sham group (Figures 2E and 2F). Importantly, we found that like LTP and chronic pain hypersensitivity, the increase in CGRP afferents induced by HFS was also prevented by intrathecal injection of the NMDA receptor antagonist D-AP5 (Figure 2G and 2H). In contrast, no change in IB4 expression was observed at 7 days after HFS (Figures 2G and 2H).

Furthermore, the immunostaining of ipsilateral SDH showed that fluorescence intensities of synaptophysin, a marker of presynaptic termini, GAP43, a protein crucial for nerve fiber growth and sprouting (Benowitz and Routtenberg, 1997), and substance P (SP) were significantly increased at 7 d after HFS, compared to the sham group. Their colocalization with CGRP was also increased (Figure S4A–E). Therefore, presynaptic synaptophysin, SP and GAP43 levels are increased in the CGRP+ terminals after 10V HFS. In addition, we found that the fluorescence intensity of CGRP in the cell bodies of the ipsilateral L4 DRG neurons increases gradually from day 1 d to day 7 after HFS (Figure S4F and G). Together, HFS induces a long-lasting increase in CGRP terminals in SDH, which may serve as a structural basis for chronic pain hypersensitivity induced by HFS.

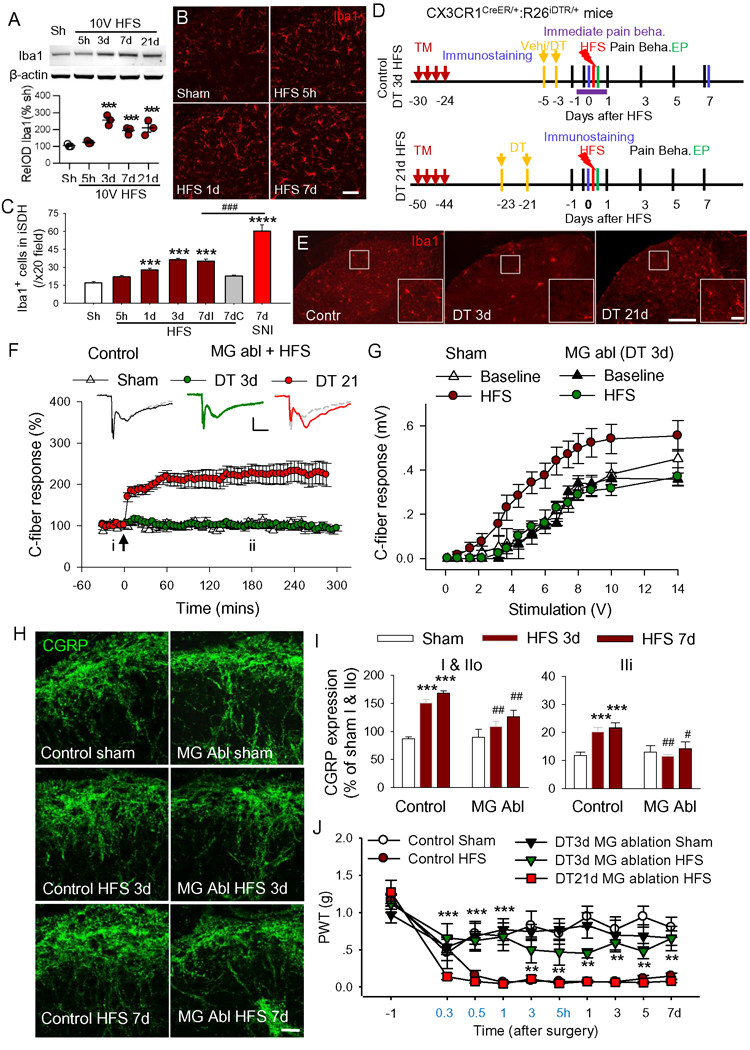

Microglia are required for HFS-induced LTP and chronic pain

Activation of microglia is important for both neuropathic pain induced by nerve injury (Inoue and Tsuda, 2018) and for LTP at C-fiber synapses (Clark et al., 2015). To determine the roles of microglia in 10 V HFS-induced synaptic plasticity and pain hypersensitivity, we first examined if our stimulation protocol is able to activate spinal microglia. The expression of Iba1 (a marker of microglia) in SDH was significantly upregulated at 3, 7 and 21 days but not acutely (5 h after HFS; Figure 3A). However, Iba1 staining also suggests that microglial somas become enlarged between 5 h and 7 d after HFS (Figure 3B). Further, the number of Iba1+ spinal microglia was markedly increased 1 day after HFS (Figures 3B and 3C). In contrast to SNI, which activated microglia in both dorsal and ventral horn, 10V HFS did so only in the dorsal horn (Figure S5A).

Figure 3. Microglia ablation blocks the spinal LTP, the increase in CGRP terminals and mechanical allodynia in induced by HFS.

(A) Western blots show the time course of Iba1 expression level after 10V HFS (n = 3 mice/ group). ***P< 0.001 vs. sham group, one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test. (B, C) Representative images of Iba1 immunostaining and the histogram show that the number of Iba1+ microglia were increased in the ipsilateral SDH at 1, 3 and 7 days after 10V HFS, and 7 days after SNI. Iba1+ cells were increased only in ipsilateral but not in contralateral SDH 7 days after HFS (7dI and 7dC). Scale bar: 50 μm. n = 3 mice/group, 2–3 sections/mouse. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001vs. sham group, ###P < 0.001 vs. HFS 7d group, one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test. (D) Experiment designs for control or microglial ablation (MG abl) at 3 or 21 days after vehicle (vehi, corn oil) diphtheria toxin treatment in CX3CR1CreER/+: R26iDTR/+mice. DT: diphtheria toxin, TM: Tamoxifen, Pain Beha: pain behavior test, EP: electrophysiology. In DT 3d HFS or DT 21d HFS group, DT was injected 3 weeks after TM and HFS was delivered at 3 or 21 days after last application of DT. In control group, vehicle (Vehi) but not DT was injected following TM injection. (E) The immunofluorescent staining showed that microglia were largely depleted at 3 days after DT treatment (DT 3d), and then fully repopulated within 21 days after DT treatment (DT 21d) in CX3CR1CreER/+: R26iDTR/+ mice. Boxed areas are magnified in the right panel. Scale bars: 100 μm (left) and 25 μm (right). (F) HFS was able to induce LTP at 21 days but not at 3 days after DT injection (n = 12 mice for DT 3 d group, n = 6–7 mice for other groups, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test). Representative traces of evoked C-fiber fEPSP are shown above before (i, grey line) and 3 h after 10V HFS (ii, colored line). Scale bars: x = 100 ms, y = 0.15 mV. The arrow indicates the time point at which HFS was delivered. (G) The input-output curves of fEPSP measured 7 d after HFS in mice treated with DT (for microglial ablation) and with vehicles are shown (n = 5 mice for sham group, n = 5 or 7 mice for MG ablation groups). (H, I) The increase in CGRP+ terminals induced by HFS was substantially attenuated in microglia ablation mice (n = 3 mice/group, 2–3 sections/mouse). Scale bar: 20 μm. ***P < 0.001 vs. control sham group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. control HFS 3d or 7d group, one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test. (J) HFS induced mechanical allodynia in mice with microglia full repopulation (DT 21d), but not in mice with microglia ablation (DT 3d). n = 12 mice in MG ablation DT 3d group, n = 8 mice for other groups. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Control HFS, two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test.

To determine the causal link between microglial activation, spinal plasticity, and chronic pain hypersensitivity, we performed experiments with CX3CR1CreER/+:R26iDTR/+ mice, in which CX3CR1 cells express the diphtheria toxin (DT) receptor (Parkhurst et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2016). DT was applied 3 weeks after the last injection of Tamoxifen (TM) to selectively ablate microglia in the CNS but not peripheral macrophages due to their fast turnover. We found that microglia were largely ablated at 3 days after DT injection in CX3CR1CreER/+:R26iDTR/+ mice. Afterwards, microglia fully repopulated within 3 weeks (Figure 3D and 3E). Interestingly, HFS at 10V was unable to induce spinal LTP 3d after DT injection, whereas LTP could be induced when microglia were repopulated at 21 days after DT treatment (Figure 3F). These results strongly indicate that spinal microglia are required for HFS-induced LTP.

If microglial depletion abolishes LTP, we expected that HFS-induced, long-lasting functional and structural plasticity would be reduced. Indeed, in the mice receiving HFS at 3 d after DT injection, fEPSP input-output curves, measured 7–14 days after HFS, were not different from sham mice. In non-DT control mice, HFS induced a leftward shift of the curve (Figure 3G). Consistently, the increase in CGRP terminals induced by HFS was also substantially attenuated in microglia-depleted mice compared to control mice (Figure 3H and 3I). Finally, we found that the HFS-induced mechanical allodynia was significantly reduced in the mice receiving DT injection 3 d before HFS, compared to either control mice or mice receiving a DT injection 21 d before HFS (Figure 4J). These results indicate that the development of mechanical allodynia is dependent upon spinal microglia. Spinal LTP in mice was induced within 20 min after HFS and stabilized at around one hour (Figure 1A and 3F). We observed that mechanical hypersensitivity was swiftly and fully developed at 30 min after HFS (Figure 4J). To test if microglia are also involved in the maintenance of mechanical allodynia, DT was injected 7 d and 9 d after HFS. We found that deletion of microglia was unable to reverse HFS-induced mechanical allodynia (Figure S5B and S5C).Together, these results suggest that microglia are indispensable for induction but not for maintenance of HFS-induced chronic pain hypersensitivity.

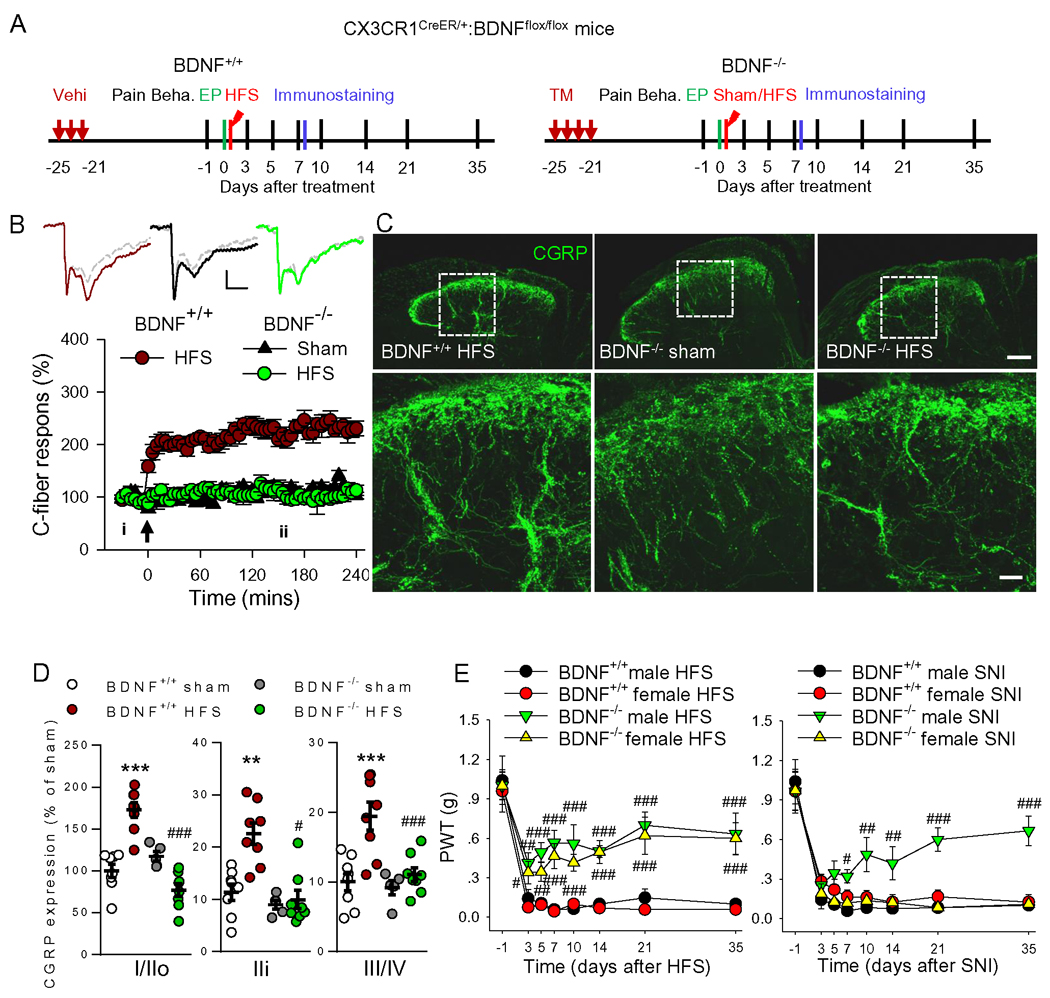

Figure 4. Ablation of microglial BDNF prevented LTP induction, the increase in CGRP terminals and mechanical allodynia induced by HFS.

(A) Schematic overview of experiments with BDNF−/−, CX3CR1CreER/+: BDNFflox/flox mice, in which BDNF can be specifically deleted from microglia by TM injection. (B) 10V HFS induced spinal LTP in BDNF+/+ mice but not in mice with microglial BDNF deletion (BDNF−/−). n = 6–7 mice/group. Examples of C-fiber field potentials are shown above (i, grey lines) and 3 h after 10V HFS (ii, color lines). Scale bars: x = 100 ms, y = 0.2 mV. The arrow indicates the time point at which conditional stimulation was delivered. (C, D) Representative images and summary data show that HFS-induced CGRP upregulation was inhibited by microglial BDNF ablation (n = 3–4 mice/group, 3–4 sections/mouse). ***P < 0.001 vs BDNF+/+ sham group, ###P < 0.001 vs. BDNF+/+ HFS group, one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test. Scale bars: 100 μm (top), 20 μm (bottom). (E) Unlike SNI model, HFS induced mechanical allodynia was significantly reversed in male and female mice deficient of microglial BDNF compared with control mice. ***P < 0.001 vs. female BDNF+/+ HFS or SNI group, two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test.

Microglial BDNF is essential for HFS-induced LTP and chronic pain

BDNF has been implicated in spinal LTP and neuropathic pain (Coull et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2011). Therefore, we examined the role of microglial BDNF in the synaptic plasticity and chronic pain induced by HFS using CX3CR1CreER/+:BDNFflox/flox male mice, in which BDNF can be specifically deleted from microglia by TM injection. To ensure the deletion of microglial BDNF, the experiments were performed around 3 weeks after TM injection (Figure 4A). We found that HFS induced LTP and increased CGRP+ terminals in SDH in control mice (BDNF+/+) but not in mice with microglial BDNF deletion (BDNF−/−, Figure 4A–D). Deletion of BDNF from microglia attenuated HFS-induced mechanical allodynia in both male and female mice, while the same manipulation prevented SNIinduced pain hypersensitivity only in male mice (Figure 4E), which is consistent with a previous work (Sorge et al., 2015). These results indicate that microglial BDNF is required for HFS-induced functional and structural synaptic plasticity in SDH, thereby contributing to chronic pain.

To confirm the roles of BDNF for HFS-induced cellular and behavioral changes, BDNF (20 ng/μl, 5 μl) was injected intrathecally into wild-type mice. We found that BDNF directly caused mechanical allodynia that lasted for > 10 d (Figure S6A). Consistent with the role of BDNF in promoting the sprouting of CGRP primary afferents (Orita et al., 2011; Song et al., 2008), immunostaining and Western blot revealed that CGRP expression in SDH was significantly increased at 3 days after BDNF injection (Figures S6B and S6C), while CGRP in DRG neurons was not changed (data not shown). To further investigate the effect of BDNF on CGRP terminals and to explore the underlying mechanisms, we performed experiments in cultured DRG neurons. Compared with the control cultures, application of BDNF (50 ng/ml) for 1 day markedly increased CGRP neurite length. This effect of BDNF was abolished by both the TrkB antagonist ANA-12 (10 μM) and the CREB inhibitor 666–15 (0.5 μM) (Figure S6D and S6E). These results suggest that BDNF promotes the increase in CGRP terminals via the BDNF/TrkB/CREB signaling pathway.

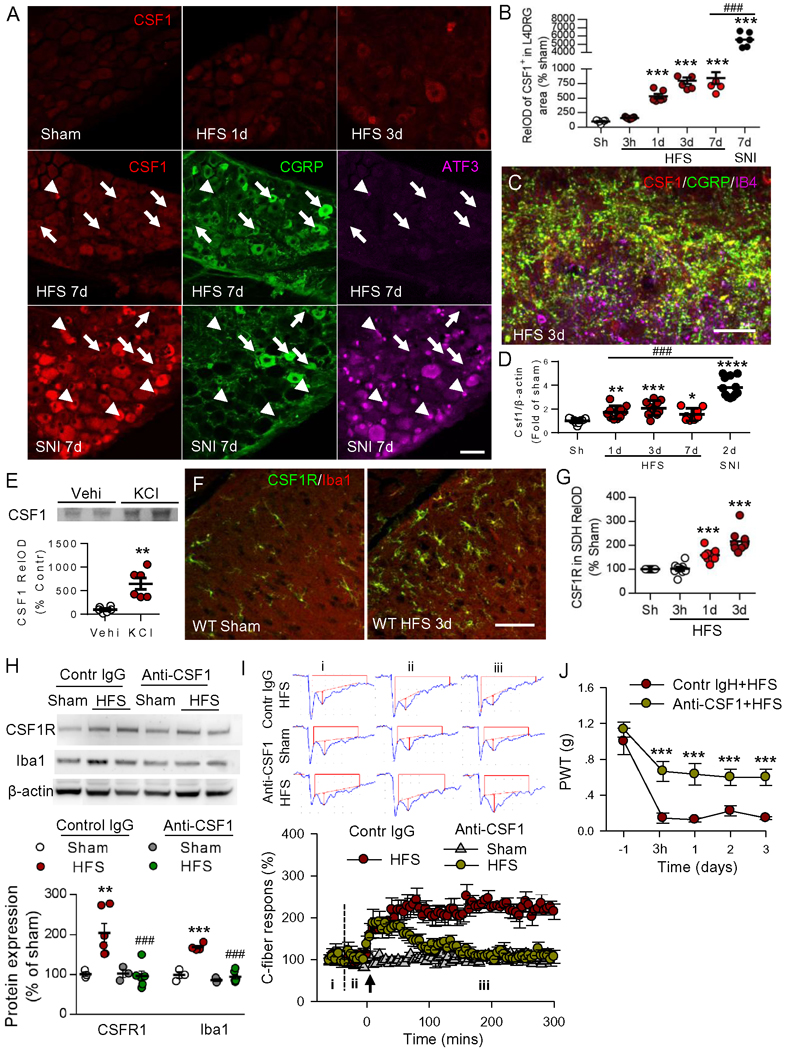

CSF1 signaling in microglial activation, LTP induction, and chronic pain

It is unclear how HFS could activate spinal microglia in the sciatic nerve. A recent study shows that peripheral nerve injury induces de novo expression of colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) in the injured dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons. CSF1 activates microglia by binding to CSF1 receptors (CSF1R) that are exclusively expressed in microglia in SDH (Guan et al., 2016). Therefore, we tested whether CSF1 signaling might also participate in 10 V HFS-induced microglial activation, spinal LTP, and chronic pain. To do this, we first examined the expression of CSF1 in DRG and dorsal horn after HFS. In DRG neurons, we found that CSF1 was expressed at a very low level in sham mice, and was upregulated gradually from 1 d to 7d after 10V HFS (Figure 5A and 5B). The CSF1 expression induced by HFS was lower than that of SNI (Figure 5B). In SNI rats, CSF1 was expressed not only in injured DRG neurons (Figure 5A, ATF3+, arrowheads) but also in uninjured neurons (ATF3−, arrows), which is consistent with a previous work (Guan et al., 2016). Interestingly, we found that in SDH, CSF1 was only colocalized with CGRP but not with IB4 (Figure 5C). These results indicate that HFS upregulates CSF1 in DRG neurons and in CGRP+ terminals in the SDH. Similarly, CSF1 mRNA was progressively increased in ipsilateral L4–5 DRGs from 1 d to 7 d after HFS (Figure 5D). When compared to HFS, SNI resulted in more significant enhancement in CSF1 mRNA at 2 d after nerve injury. Moreover, in cultured DRG neurons 40 mM KCl, which causes dramatic DRG neuron depolarization, significantly increased CSF1 in culture media (Figure 5E), indicating DRG neurons release CSF1 upon activation. Furthermore, immunofluorescence showed that HFS also significantly upregulated CSF1R in Iba1+ microglia, from 1 to 3 d after HFS (Figure 5F and 5G). Western blots revealed that both CSF1R and Iba1 were upregulated by HFS, and the changes were prevented by a single intrathecal injection of anti-CSF1 (40 ng/μl, 5 μl) 30 min before HFS (Figure 5H). This result indicates that CSF1 signaling is necessary for HFS-induced microglial activation. To determine the role of CSF1 signaling in spinal LTP, anti-CSF1 (40 ng/μl, 20 μl) was applied to the dorsal surface of the spinal cord 30 min before HFS. We found that anti-CSF1 did not affect basal transmission, but blocked late-phase spinal LTP. Specifically, HFS-induced potentiation only lasted for approximately one hour and then gradually returned to baseline, while application of IgG affected neither basal transmission nor LTP induction (Figure 5I). Consistently, we found a single intrathecal injection of CSF1 (6 ng/μl, 5 μl, daily for three days) induces mechanical allodynia lasting for around a week (Figure S7A) and upregulates CSF1R in activated spinal microglia (Figure S7B–E). This indicates that CSF1 is also sufficient to activate spinal microglia. Additionally, we found that the single intrathecal anti-CSF1 injection also substantially attenuated HFS-induced chronic allodynia (Figure 5J). These results suggest that HFS-induced CSF1 upregulation in DRGs and CGRP afferent terminals is important for chronic pain.

Figure 5. HFS upregulates CSF1 in CGRP terminals and CSF1 receptors in microglia, leading to spinal LTP and pain hypersensitivity.

(A, B) The representative images and statistical analysis show the expression of CSF1 in the ipsilateral L4 DRG from 1 to 7 days after HFS and 7 days after SNI. The triple staining images showed the colocalization of CSF1, CGRP and ATF3. The arrowheads indicate that the injured DRG neurons (ATF3+) that strongly express CSF1 does not express CGRP. The arrows indicate the uninjured neurons (ATF3−) that weakly express CSF1 express CGRP following HFS or SNI. Scale bar: 50 μm. n = 3 mice/group, n = 2–3 images/mouse, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs sham group; ###P < 0.001, compared with HFS 7d group, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. (C) Triple staining show CSF1 in SDH was co-localized with CGRP but not with IB4 at 3 days after HFS. Scale bar: 20 μm. (D) qRT-PCR analysis for CSF1 mRNA in the ipsilateral L4–5 DRGs from different groups (n = 7–12 mice/group). Values are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.00001 vs. sham group; ###P < 0.001, compared with HFS 7d group, one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test. (E) Western blot and statistical analysis show that treatment of cultured DRG neurons with 40 mM KCl for 24 h increased CSF1 in culture media. n = 6 samples/group, **P < 0.01 vs Vehi group, unpaired Student’s t-test. (F, G) Immunostaining shows CSF1R in microglia was upregulated in the ipsilateral dorsal horn at 1 and 3 days after HFS (n = 3 mice/group, 2–3 sections/mouse). Scale bar: 50 μm. ***P < 0.001, compared with sham group, ###P < 0.001, compared with HFS 7d, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. (H) Western blots illustrate the increased expression of CSF1R and Iba1 protein levels at 3 days after 10V HFS, and the changes were blocked by intrathecal injection of CSF1 neutralizing antibody (anti-CSF1, 40 ng/μl, 5 μl) 30 min before HFS (n = 3–4 mice/group). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. sham group. ###P < 0.001 vs. control HFS group, one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test. (I) Local application of anti-CSF1 (40 ng/μl, 20 μl) onto the dorsal surface of spinal cord at recording segments 30 min before HFS did not affect baseline of C-fiber responses, but blocked late-phase of the spinal LTP (n = 5–6 mice/group). Original traces of C-fiber fEPSPs from different groups, recorded at the baseline (i), 30 min before (ii) and 3 h (iii) after HFS, are shown on the top. Scale bars: x = 100 ms, y = 0.2 mV. The arrow indicates the time point at which conditional stimulation was delivered. (J) Intrathecal injection of anti-CSF1 antibody 30 min before HFS prevented the development of mechanical hypersensitivity (n = 6 mice/group, ***P < 0.001 vs. vehicle group (Vehi), two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test.

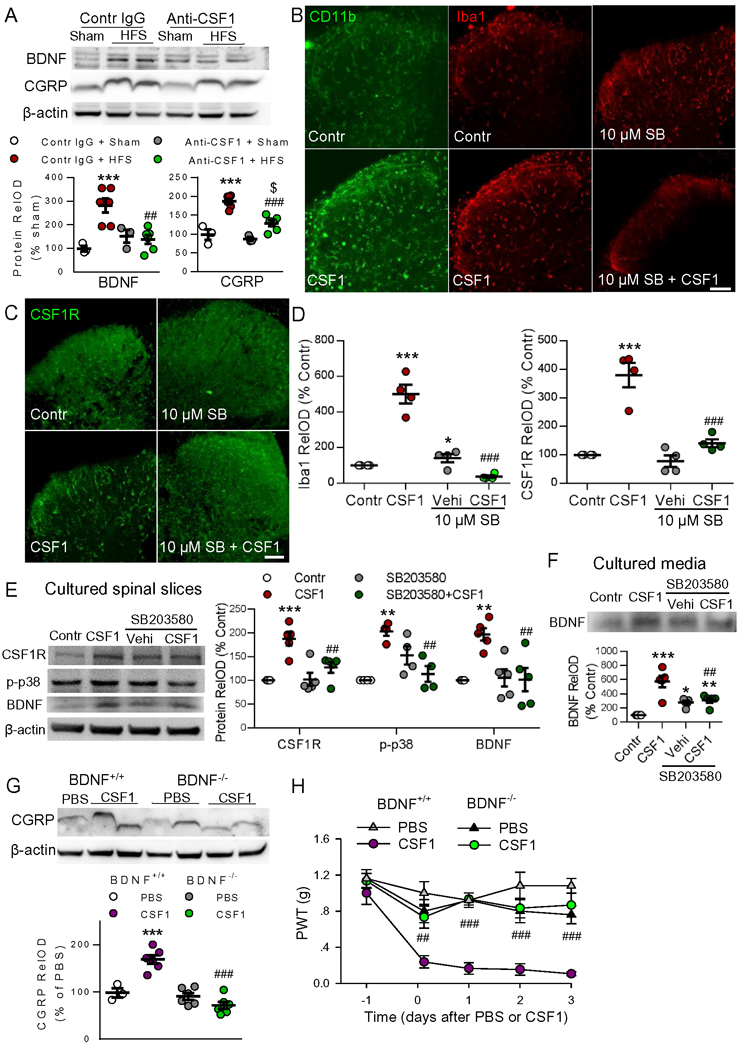

CSF1 signaling-dependent microglial BDNF in HFS-induced chronic pain

We have demonstrated that both CSF1 signaling and microglial BDNF are required for HFS-induced functional and structural synaptic plasticity as well as pain hypersensitivity. However, it is still unknown whether CSF1 signaling and microglial BDNF are independently engaged in HFS-induced chronic pain. To determine if there is a relationship between increased CSF1 signaling and upregulation of BDNF and CGRP, we applied anti-CSF1 antibody (40 ng/μl, 5 μl) intrathecally 30 min before HFS. We then examined BDNF and CGRP expression 3 days later. We found that anti-CSF1 treatment reduced both BDNF and CGRP upregulation otherwise induced by HFS (Figure 6A). To verify the effects of CSF1 on microglial activation and to investigate the underlying mechanisms, we performed experiments with cultured spinal cord slices. Treatment with CSF1 (1 μg/ml) for 6 h markedly upregulated microglial markers (CD11b and Iba1) as well as CSF1R expression. These effects were dose-dependently suppressed by the selective p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (1 μM or 10 μM, added 1 h prior to CSF1) (Figure 6B–D). Western blots showed that CSF1 application upregulated CSF1R, p-p38 MAPK and BDNF. These increases were significantly blocked by SB203580 (Figure 6E). CSF1 also increased BDNF in culture media, which could also be attenuated by SB203580 (Figure 6F). As p38 is exclusively expressed in microglia in SDH and its activation is critical for microglial activation (Ji and Suter, 2007), these in vitro experiments indicate that CSF1 is sufficient for microglial activation and BDNF release, while BDNF release depends on microglial activation.

Figure 6. Microglial BDNF is required for CSF1-induced increase in CGRP terminals and pain hypersensitivity.

(A) HFS upregulated BDNF and CGRP levels in SDH, and the effects were prevented by intrathecal injection of anti-CSF1 (40.0 ng/μl) 30 min before HFS (n = 3–6 mice/group). ***P < 0.001 vs. control sham group. ##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001 vs. control HFS group; $P < 0.05 vs. anti-CSF1 sham group, one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test. (B-D) In cultured spinal cord slices, CSF1 (1 μg/ml) markedly upregulated microglial markers (CD11b and Iba1) and CSF1R, and the effects were dose-dependently suppressed by p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (10 μM) applied 1 hour prior to CSF1. Scale bar: 100 μm. n = 4–5 samples/group,* P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs control group; ###P < 0.001 vs CSF1 group, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. (E-F) In culture spinal cord slices, treatment with CSF1 for 6 hours upregulated CSF1R, the phospho-p38 MAPK (p-p38) and BDNF, as well as increased BDNF in culture media. Pretreatment with p38 inhibitor SB203580 (10 μM) abolished the effects of CSF1. n = 3–5 samples/group, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs control group; ##P < 0.01 vs CSF1 group, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. (G) Intrathecal CSF1 upregulated CGRP expression in BDNF+/+ mice but not in mice deficient of microglial BDNF (BDNF−/−), as measured 3 days after injection (n = 3–6 mice/group). ***P < 0.001 vs. BDNF+/+PBS group, ###P < 0.001 vs. BDNF+/+ CSF1 group, one-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test. (H) The mechanical allodynia induced by intrathecal CSF1 was significantly attenuated in microglial BDNF deletion mice compared with control mice (n = 5–6 mice/group, ###P < 0.001 vs. BDNF+/+ CSF1 group), two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test.

Based on above results, we hypothesized that the activation of CSF1 signaling by HFS leads to microglial activation, and subsequent microglial BDNF release is critical for the increase in CGRP terminals and associated chronic pain behaviors. To directly test this hypothesis, we examined the effect of CSF1 on CGRP expression in the presence or absence of microglial BDNF. We found that intrathecal injection of CSF1 (20 ng/μl, 5 μl) increased CGRP expression only in control mice (BDNF+/+) but not in CX3CR1CreER/+:BDNFflox/flox mice 21 days after TM injection (BDNF−/−), when BDNF was selectively deleted in microglia (Figure 6G). CSF1-induced mechanical allodynia was largely attenuated in mice deficient of microglial BDNF compared with control mice (Figure 6H). Therefore, microglial-specific BDNF is required for CSF1-induced CGRP upregulation and chronic pain.

Discussion

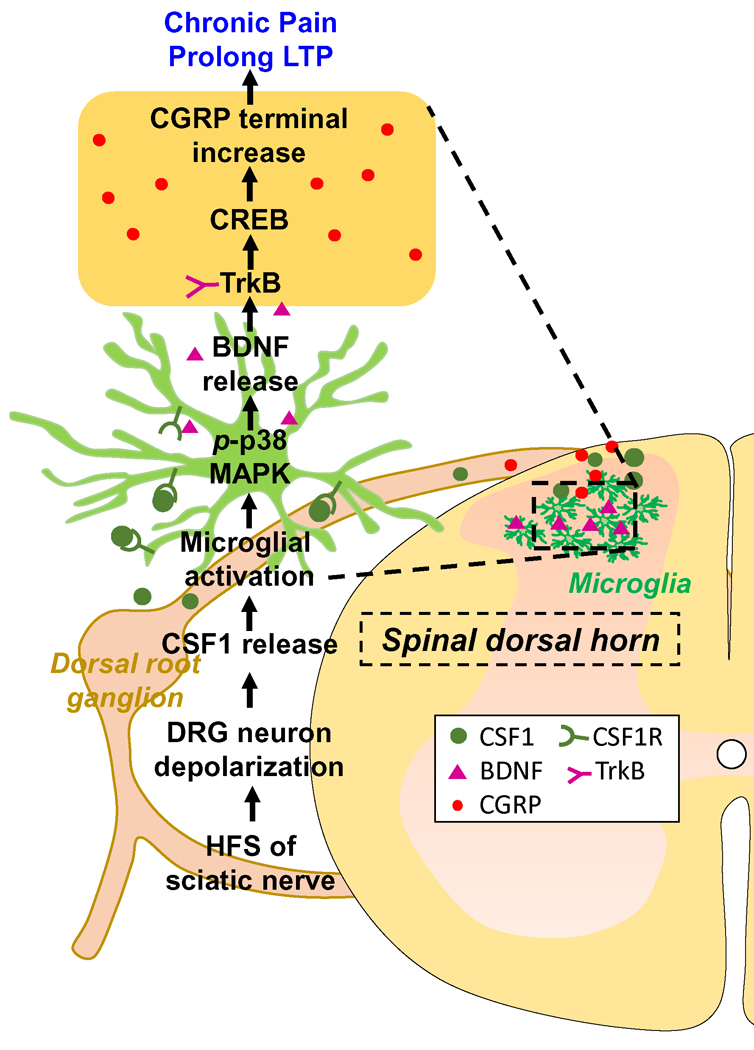

LTP in hippocampus is considered as a biological substrate for some forms of memory (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993). Up to date, however, a definitive demonstration indicating that memory and LTP share the same cellular and molecular mechanisms and that induction of LTP will result in some form of memory is still lacking (Lynch, 2004). This is difficult to achieve, largely due to complexity in synaptic connections and functions of hippocampus. On the other hand, spinal LTP at C-fiber (pain fiber) synapses (Liu and Sandkuhler, 1995) is believed to be a pain memory that may underlie some forms of chronic pain (Liu and Zhou, 2015). The present work provides evidence supporting the hypothesis that induction of LTP at synapses between afferent C-fibers and dorsal horn neurons by 10 V HFS is associated with mechanical allodynia lasting for 50 d in rats (Figure S2B) and >35 d in mice (Figure 4E), as well as thermal hyperalgesia for around 14 d (Figure 1H). A microglial BDNF-dependent increase in (or sprouting of) CGRP terminals, which is found in a variety of chronic pain conditions (Christensen and Hulsebosch, 1997; Xu et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2008), serves as a structural basis of the chronic pain. Our finding is also clinically important, as chronic pain, unlike acute pain, rarely has an identifiable temporal and causal relationship to injury or disease in the body. Chronic pain with unknown etiology was recently classified as chronic primary pain (Treede et al., 2015), with the underlying mechanism still poorly understood. Spinal LTP at C-fiber synapses can be induced in many ways, including peripheral nerve injury (Zhang et al., 2004), activation of presynaptic terminals by electrical stimulation of afferent C-fibers (Liu and Sandkuhler, 1995), or direct activation of glial cells by local application of BDNF (Zhou et al., 2008), fractalkine (Clark et al., 2015) or ATP receptor agonists (Kronschlager et al., 2016) without direct activation of presynaptic component. At present, it is generally believed that chronic pain is produced by nerve injury (neuropathic pain) and/or inflammation (inflammatory pain) (Yekkirala et al., 2017). Here we show that HFS-induced chronic pain in naïve mice is neither associated with nerve injury nor inflammation near the stimulated nerve (Figure 1 B–F). Therefore, we exposed a form of chronic pain that is produced by activation of spinal microglia through intensive peripheral nerve stimuli (Figure 7). This mechanism may be an important insight into explaining chronic pain without a clinically obvious cause.

Figure 7. Schematic diagram depicting the mechanism of HFS of sciatic nerve induced chronic pain without the stimulated sciatic nerve injury.

HFS of sciatic nerve (1) depolarizes DRG neuron (2) to release CSF1 from the central terminals (3); CSF1 activates microglial CSF1R/p38 MAPK to release BDNF (4); BDNF causes the increase of CGRP terminal via TrkB/CREB signaling (5) Microglia activation and CGRP terminal increase underlie prolonged LTP (6) and chronic pain (7).

Action potential discharge in nociceptive afferents evoked by HFS underlie chronic pain

As early as 1883, W. A. Sturge demonstrated that peripheral injury triggers a change in CNS excitability such that normal inputs evoke exaggerated responses as part of pain hypersensitivity (Sturge, 1883). Consistent with this notion, nerve injury has been shown to induce a transient action potential discharge in afferent A- and C-fibers within the first seconds following injury (Liu et al., 2000). This phenomenon, called injury discharge, is believed to trigger chronic pain. To date, however, whether the injury discharge alone is sufficient to generate chronic pain is still unknown, as peripheral nerve injury also causes hypersensitivity of the afferent neurons.

Our previous work shows that injury of the sciatic nerve induces LTP at C-fiber synapses within minutes, and the effect is completely prevented by blocking action potential conduction with lidocaine (Zhang et al., 2004), indicating that the injury discharge is sufficient to induce spinal LTP. In the current study, we showed that HFS at the sciatic nerve triggered long-lasting pain hypersensitivity in mice by inducing spinal LTP without any observable nerve injury. Temporally, HFS induced spinal LTP within a few minutes and pain hypersensitivity in about 30 minutes. Inhibition of LTP by local application of lidocaine to sciatic nerve or by intrathecal injection of an NMDA receptor antagonist prevented the chronic pain (Figures 1I, 1J and Figure S1). However, HFS at A-fibers neither induced LTP nor chronic pain. Together, activation of spinal NMDA receptors through HFS of nociceptive afferents is sufficient to induce chronic pain hypersensitivity. These effects are not associated with any other changes in the periphery that might be produced by HFS. Interestingly, we have shown that action potential discharges in primary afferent C-fibers by HFS are sufficient to activate spinal microglia. Consequently, HFS may potentially induce neurogenic neuroinflammation in the spinal cord as the root cause for chronic pain.

The roles of peptidergic C-fiber terminals in initiation and maintenance of HFSinduced chronic pain hypersensitivity

Peptidergic C-fiber terminals express and release bioactive substances including glutamate, CGRP, SP, BDNF (Lever et al., 2001), ATP (Kronschlager et al., 2016), fractalkine (Clark et al., 2015), and CASP6 (Berta et al., 2014). These released signaling molecules play a role in spinal LTP and pain hypersensitivity by volume transmission as well as by classical synaptic transmission (Borroto-Escuela et al., 2015). For example, both NK1 and NK2 SP receptors are required for spinal LTP induction (Liu and Sandkuhler, 1997). Spinal application of BDNF directly induces a late-phase spinal LTP and mechanical allodynia by activation of microglia (Zhou et al., 2011). Human studies suggest that activation of peptidergic cutaneous afferents is responsible for HFS-induced mechanical allodynia (Pfau et al., 2011). Together, activation of the peptidergic C-fibers is critical for induction of spinal LTP at C-fiber synapses.

CGRP has been identified as an important molecule in spinal nociceptive processing and in migraine headache (Edvinsson et al., 2018). Increases in CGRP afferents in SDH is reported in a variety of chronic pain conditions, such as vincristine-induced neuropathy (Xu et al., 2017), sciatic nerve crush or transection (Zheng et al., 2008), and spinal cord hemisection (Christensen and Hulsebosch, 1997). In the present work, we showed that CGRP terminals, the number of CGRP+ varicosities, and the number of CGRP+ synapses increased significantly in dorsal horn following HFS (Figure 2C–F). Importantly, in the CGRP+ terminals, synaptophysin, SP and GAP43 were significantly increased after HFS (Figure S4). These data suggest that the increase in CGRP+ terminals results from axon sprouting. Therefore, we presumed that the increase of CGRP terminals may be critical for the transition from acute pain to chronic pain.

NMDA receptors are critical for the induction of spinal LTP (Liu and Sandkuhler, 1995). In the present work, we demonstrated that blocking NMDA receptors by D-AP5 suppressed HFS-induced CGRP increases (Figure 2G and 2H), which is consistent with previous studies (Csati et al., 2015; Wong et al., 2014). As synaptic functional plasticity leads to structural plasticity, the effect of the NMDA receptor antagonist D-AP5 on CGRP terminals may result from the inhibition of spinal LTP. As NMDA receptors are also expressed in the presynaptic terminal and facilitate glutamate release from primary afferents (Chen et al., 2014; Liu et al., 1994), it is also possible that the activation of NMDA receptors directly upregulates CGRP expression and release in the dorsal horn. Further studies are needed to clarify this issue.

The roles of microglia and BDNF in HFS-induced LTP and chronic pain

Previous work shows that activation of microglia by fractalkine (CX3CL1), ATP, IL-1β, and TNF-α is critical for the induction of spinal LTP (Clark et al., 2015; Gruber-Schoffnegger et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2018). In the present study, we further tested the role of microglia in spinal LTP by depleting resident microglia but not peripheral monocytes/macrophages using CX3CR1CreER/+:R26iDTR/+ transgenic mice. Our results showed that the selective deletion of spinal microglia blocked HFS-induced LTP, the increase in CGRP+ terminals, and chronic pain hypersensitivity (Figure 3).

How can HFS activate spinal microglia? A previous study shows that electrical stimuli (5 Hz, 0.5 ms 0.1–10 mA, total 3000 pulses for 10 min) activate spinal glial cell and also induce nerve degeneration in rats (Shortland et al., 1997). Our previous study demonstrated that 400 pulses of electrical stimulation at 2 Hz, 20 Hz or 100 Hz at 30–40 Volts but not 3 Volts could induce spinal LTP in rats (Liu and Sandkuhler, 1997). In the present study, we found that 400 pulse HFS at 10 V (100 Hz, 0.5 ms, 4 trains of 1-s duration at 10-s intervals) was an effective electrical stimulation paradigm in mice for LTP that also leads to spinal microglia activation and long-lasting mechanical hypersensitivity without stimulated nerve injury. Collectively, different electrical stimulating parameters (such as the intensity, frequency and duration) have different influences on microglial activation. In addition, previous studies show that microglial activation induced by electrical stimulation of the sciatic nerve at C-fiber intensities can be blocked by the NK1 receptor antagonist LY303870 (Li et al., 2015). Direct activation of glial cells by local application of BDNF (Zhou et al., 2011), CASP6 (Berta et al., 2014), fractalkine (Clark et al., 2015), TNF, or ATP receptor agonists (Kronschlager et al., 2016) is sufficient to induce spinal LTP and pain hypersensitivity through microglia without causing axonal degeneration. Therefore, spinal microglia are able to sense nociceptive signals, and the neuromodulators (such as SP, ATP, BDNF, CASP6 or CSF1) released from peptidergic C-fibers is essential for rapid microglial activation.

Previous work (Guan et al., 2016) shows that CSF1 is upregulated in injured DRG neurons 1 d but not 12 h after peripheral nerve injury. CSF1Rs, which are exclusively expressed in microglia in SDH, are upregulated 2–3 d after nerve injury. CSF1 in injured DRG neurons is suggested to transport to SDH, where, it activates microglia by binding to CSF1R. In the present work, we found that 10 V HFS also upregulated CSF1 mRNA and protein in DRG neurons, although the magnitude of the upregulation was weaker than that induced by SNI (Figure 5A, 5B and 5D). Importantly, HFS upregulates CSF1 only in CGRP+ terminals in SDH (Figure 5C). HFS also upregulated CSF1R in spinal microglia. Our results showed that HFS-induced LTP and pain hypersensitivity happened swiftly (within hours), while CGRP was upregulated days after HFS (Figure 2). These results suggest that HFS-induced LTP might be the trigger for later biochemical changes in the spinal dorsal horn. In terms of Iba1 upregulation 3 days after HFS (Figure 3), this may reflect late activation of microglia. HFS may acutely activate microglia through CSF1 signaling within hours, at which time Iba1 upregulation did not yet happen. Together, we propose that spinal microglia are activated by neurotransmitters released from CGRP+ C-terminals immediately after HFS, and later by CSF1, which is increased in CGRP+ terminals. Therefore, CGRP+ C-terminals are critically involved in the initiation and maintenance of microglial activation in SDH.

It is well established that activation of the BDNF/TrkB pathway is essential for both spinal LTP induction (Zhou et al., 2008) and the development of neuropathic pain (Coull et al., 2005). BDNF expressed in peptidergic DRG neurons is released from central terminals in SDH in response to short bursts of HFS at C-fiber strength (300 pulses in 75 trains, 100 Hz) along with SP and glutamate (Lever et al., 2001). Selective deletion of BDNF in nociceptive DRG neurons impairs the inflammatory pain induced by formalin or carrageenan injection; however, it does not affect neuropathic pain (Zhao et al., 2006). Consistent with previous work (Sorge et al., 2015), we found that genetic depletion of BDNF from microglia attenuates nerve injury-induced mechanical allodynia in male but not in female mice (Figure 4E). However, microglial BDNF deletion prevents HFS-induced LTP, CGRP upregulation, and mechanical allodynia in both male and female mice (Figure 4E). Our data confirmed that BDNF was sufficient to enhance CGRP+ terminals in vivo and in vitro. A previous work shows that TrkB expression in CGRP peptidergic C-fiber terminals (Merighi et al., 2008). We further uncovered that BDNF/TrkB/CREB signaling pathway are involved in CGRP terminal increase.

Although our results indicate an important role of microglial BDNF in chronic pain induced by nerve injury and HFS, recent studies show BDNF gene expression is at very low levels in microglia of the adult brain (Bennett et al., 2016) and spinal cord (Denk et al., 2016). Therefore, BDNF released from microglia might be limited. How the small amount of BDNF is so important for chronic pain remains elusive. In addition, it is still unknown how BDNF from diverse sources (nociceptive afferents vs microglia) differentially affects inflammatory pain and neuropathic pain, and why deletion of microglial BDNF attenuates neuropathic pain only in male but suppresses HFS-induced chronic pain in both male and female mice. We believe that the discrepancy could be due to the different pain models, i.e. HFS-induced chronic pain vs. nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain. Further studies are needed to clarify these issues. Interestingly, our previous study showed that inhibition of BDNF signaling did not affect LTP induced by 40V HFS in rats (Zhou et al., 2008). The discrepancy could be due to the potential damage to the stimulated nerve by 40V HFS as reported previously (Liang et al., 2010). Therefore, both nerve injury and activation of afferent fibers contribute to HFS-induced LTP, likely using different signaling pathways.

In summary, we report that the electrical HFS that induces spinal LTP at C-fiber synapses without causing the stimulated nerve injury leads to long-lasting mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in mice. Our findings may explain chronic primary pain that occurs in the absence of injury or disease.

STAR★METHODS

Detailed methods are provided in the online version of this paper and include the following:

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for reagents may be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact author, Long-Jun Wu (wu.longjun@mayo.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animals and husbandry

Young adult (8–12 weeks old) C57BL/6 (Charles River) mice were used as wild type controls. In some experiments, Sprague–Dawley rats (210–280 g, Laboratory animal center, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou) were used. CX3CR1CreER/+ mice (gifted from Dr. Wen-Biao Gan at New York University) were crossed with R26iDTR/+ (Jackson Laboratory) to obtain CX3CR1CreER/+:R26iDTR/+ mice. CX3CR1CreER/+ mice were crossed with BDNFflox/flox (BDNFTM3JAE/J, Jackson Laboratory) to obtain CX3CR1CreER/+:BDNFflox/flox mice. Most experiments were performed with adult male mice, and only in one special experiment of sex differences, male and female mice was used, which was specially indicated. The rodents were housed in a standard 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on 06:00) and temperature (23 ± 2 °C) controlled room with access to food and water ad libitum. All experimental protocols and animal handling procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at Rutgers University (USA) or Sun Yat-sen University (China).

Electrical stimulation-induced chronic pain model

Rodent were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane anesthesia and the left sciatic nerves were dissected free for electrical stimulation with bipolar platinum hook electrodes. HFS at different intensities (1, 10, 20 V) was delivered to the left sciatic nerve. In the sham group, the sciatic nerve was exposed and the electrode was laid aside without electrical stimulation. At the end, the muscle and skin were closed in two layers. Following surgery, mice were allowed to awake from anesthesia and were fully mobile before being returned to their home cage. The surgery was always performed in littermates and housed together until further experimentation.

Spared nerve injury

Spared nerve injury (SNI) surgery was performed as previously described (Decosterd and Woolf, 2000). Under 2% isoflurane anesthesia, incision was made along the midline of the left hind limb. The common peroneal and the tibial nerves were then ligated and cut (2 mm sections removed), but the sural nerve was left intact. At the end, the wound was sutured in two layers.

METHOD DETAILS

Microglia ablation and repopulation

According to the method described in our recent study (Peng et al., 2016), CX3CR1CreER/+ (Control) mice or CX3CR1CreER/+:R26iDTR/+ mice (over 6 weeks old) were intraperitoneally (i.p.) given tamoxifen (TM, Sigma, T5648, 0.15 g/kg, 20 mg/ml in corn oil with ultrasound) every other day for 4 times. Then two doses of diphtheria toxin (DT, Sigma, C8286, 50 μg/kg, 2.5 μg/ml in PBS) or vehicle (corn oil) were i.p. injected 3 weeks later to induce microglial ablation. To test the role of microglial ablation or repopulation or the effect of TM only, HFS-induced synaptic plasticity and chronic pain, HFS was delivered to the sciatic nerve on the 3rd or 21st day after the first DT injection, or the 7th day before the first DT injection, respectively. The effectiveness of microglial ablation or repopulation was tested at these time points by performing immunostaining of Iba1 in the spinal cord tissue.

Microglial BDNF deletion

CX3CR1CreER/+:BDNFflox/flox mice were i.p. treated with TM (0.15 g/kg, 20 mg/ml) or vehicle (corn oil) 3 times every other day and then kept for more than 3 weeks to be used as microglial BDNF ablation (BDNF−/−) mice. The mice without injection of TM served as control group (BDNF+/+).

In vivo extracellular recordings in the dorsal horn

Protocols for surgical preparation and in vivo extracellular recordings of the C-fiber induced field potential have been described in our previous studies (Liu and Sandkuhler, 1995; Zhong et al., 2010). Briefly, animals were anesthetized with urethane (Sigma, 1.5 g/kg, i.p.). A laminectomy was performed to expose the lumbar enlargement of the spinal cord. The left sciatic nerve was gently dissected free for electrical stimulation with a bipolar platinum hook electrode. Then the animal were placed in a stereotaxic frame and a small well with gel seal was formed on the cord dorsum at the recording segments for drug application or warm paraffin oil. The dura mater was incised longitudinally. Then, test stimuli (0.5 ms duration, every 1 min, at C-fiber intensity) was delivered to the sciatic nerve. C-fiber evoked fEPSP was recorded from the dorsal horn of mouse spinal cord with a glass microelectrode (filled with 0.5 M sodium acetate, impedance 0.5–1 MΩ). The optimal recording position for C-fiber fEPSP was at a depth of around 200–350 μm from the surface of the L4 lumbar enlargement of the spinal cord for mice. An A/D converter card (National Instruments M-Series PCI express) was used to digitize and store data at a sampling rate of 10 kHz in a computer. The amplitudes of C-fiber evoked fEPSP was determined on-line by LTP program (http://www.winltp.com/). In each experiment, amplitudes of five consecutive fEPSP recorded at 1 min intervals was averaged. The mean amplitudes of the responses before 0.1 M PBS/saline or drug application served as baseline. Different intensities (1, 10, 20 V) of high-frequency stimulation (HFS: 100 Hz, 0.5 ms, 100 pulses given in 4 trains of 1-s duration at 10-s intervals) were used as conditional stimulation in left sciatic nerve to induce LTP of C-fiber evoked fEPSP. In some experiments to observe the effects of the drugs on C-fiber evoked field potentials, goat anti-CSF1 antibody (AF416, 40.0 ng/μl, 20 μl, R&D Systerms, USA) or normal goat IgG control (AB-108-C, 40.0 ng/μl, R&D Systerms, USA) was directly administered onto the spinal dorsal surface at the recording segments 30 min after stable recording of C-fiber evoked field potentials. Only one experiment was performed in each animal. At the end of the experiment, the animals were decapitated under anesthesia.

Behavioral tests

Mechanical Test

Each mouse/rat was acclimated to the test environment and the experimenter 3 days prior to HFS and sham operation and was again allowed to acclimate for about 30 min before the behavioral test. All the tests were performed by two experimenters, one blinded to drug and/or surgery treatments. To test mechanical allodynia, animals were placed on an elevated wire grid and the plantar surface of the paw was stimulated with a set of Von Frey filaments (0.04 – 2 g for mice and 0.4 – 25 g for rats; North Coast medical). Each filament was applied from underneath the metal mesh floor to the lateral and medial plantar surface of the paw. The positive response of mechanical allodynia was considered to be a brisk filament evoked withdrawal response for up to 3 s to at least one of five repetitive stimuli. 50% paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) was determined using the up-down method. Mice with pre- surgery/treatment basal mechanical response threshold equal to or less than 0.16 g were excluded for use.

Thermal Test

Thermal hypersensitivity was measured using a plantar test (7370, UgoBasile, Comeria, Italy) according to the method described by Hargreaves et al(Hargreaves et al., 1988). The center plantar surface of the hind paw was exposed to a beam of radiant heat through a transparent Perspex surface. The paw withdrawal latency (PWL) was recorded when a withdrawal response to the radiant heat was observed. The basal PWL of normal adult C57BL/6J mice was 9–12 s, with a cutoff of 20 s to prevent tissue damage. The heat stimulation was repeated 4 times at an interval of 5–6 min for each paw and the mean calculated.

Rotarod test

The rotarod tests were performed as an index of injury-induced motor deficits by a five lane Rotarod apparatus (Med Associates Inc). The rotarod speed started from 4 rounds per minute (RPM) and uniformly accelerated to 40 RPM in 5 minutes. Only the latency to fall off the rotating rod was recorded. Each mouse was tested for 3 trials with 15 min interval. There is no training prior to the test phase.

Local application of lidocaine around the sciatic nerve

Two percent lidocaine (L7757, 50 μl, Sigma) was administered around the stimulated sciatic nerve 15 min before HFS to block nociceptive nerve transmission via inhibition of sodium channels.

Intrathecal injection of drugs

Adult male mice (20–30 g) were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane and injected intrathecally with different drugs in a volume of 5.0 μl with a luer-tipped Hamilton syringe at the level of the pelvic girdle. The drugs included goat anti-CSF1 antibody (AF416, 40.0 ng/μl, R&D Systerms, USA), normal goat IgG control (AB-108-C, 40.0 ng/μl, R&D Systerms, USA), recombinant mouse CSF1 (576402, 6 ng/μl, Biolegend), recombinant mouse BDNF (248-BD, 20 ng/μl, R&D systems), D-AP5 (0106, 50 μg/ml, Tocris) or vehicle (0.1 M PBS).

Fluorescent immunohistochemical staining

After mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% in O2), they were perfused intracardially with 20 ml PBS followed by 20 ml of cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 1.5% picric acid. The electrical stimulated site of the ipsilateral sciatic nerve in HFS group or the proximal stump of sciatic nerve in SNI group before entering the popliteal fossa were used for studying nerve damage. L4 dorsal root ganglion (L4 DRG) and L3–L5 segments of spinal cord were harvested and post-fixed in the same fixative for 4–6 hours, then replaced with 30% sucrose in PBS overnight at 4°C. All the tissues were sliced into 15 μm sections using a cryotome (Leica CM1250, Germany) and transferred on to Superfrost Plus Microscope slides (Fisherbrand®).

For cultured spinal slice immunostaining, the slices were fixed with 4% PFA (Sigma) for 30 mins and then washed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 7.3) for 3 times with 5-min interval. The tissue sections/cultured DRG neurons were first blocked with 5% donkey serum in 0.3% Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 60/30 min at room temperature (RT), and then incubated overnight at 4°C with a mixture of rabbit anti-ATF3 (1:500, sc-188, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), mouse anti-CGRP antibody [4901] (1:2000, ab81887, Abcam, USA), isolectin B4-FITC (1:100, L2895, Sigma, USA), rabbit anti-GAP43 antibody (1:500, ab128005, Abcam, USA), rabbit anti-Substance P receptor antibody (1:500, AB5060, Millipore, USA.), rabbit anti-Iba1 (1:2000, 019–19741, Wako), goat anti-M-CSF antibody (1:500, AF416, R&D Systems, USA); rat anti-CD11b (1:500, 101202, Biolegend, USA); goat anti-Iba1 (1:500, ab5076, Abcam, USA) or rabbit anti-CSF1R (1:500, sc-692, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA). Subsequently, the sections were then incubated with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor® 488, 555, 647; Life Technologies) for 60–90 min at RT. The coverslips were mounted with Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech) and fluorescent images were obtained with a normal microscope (EVOS FL) (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and confocal microscopes (LSM510, 780, 800, Zeiss, C2, Nikon). For cultured spinal cord slice, the confocal images were taken 50 μm thick at depth up ~50 μm from the slice surface.

Western blot

Under isoflurane anesthesia, ipsilateral L4–5 spinal dorsal horn tissue was isolated and homogenized with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and phosphatase inhibitor. Equal concentration of protein samples were resolved on 4–12% NuPAGE® Bis-Tris Precast Gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and then transferred to PVDF membranes (iBlot® 2 Transfer Stacks, PVDF, regular size (Novex™) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Membranes were blocked and then probed with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-Iba1 (1:2000, 016–20001, Wako); mouse anti-CGRP antibody [4901] (1:5000, ab81887, Abcam, USA), rabbit anti-CSF1R (1:1000, sc-692, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), rabbit anti-BDNF (1:1000, AB1534, Millipore, USA), goat anti-M-CSF antibody (1:1000, AF416, R&D Systems, USA); rabbit anti-p-p38 (1:2000, #4511, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), mouse anti-β-actin (1:5000, #3700, Cell Signaling Technology, USA) overnight at 4°C. After washed, membranes were then incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000~8000, Jackson Immune Laboratory) at RT for 90 min. Protein bands were detected by ECL detection reagent (34095, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and captured on ImageQuant™LAS4000 (Fujifilm Life Science). Integrated optical density was determined using ImageJ 1.48 (NIH). Standard curves were constructed to establish that we operated within the linear range of the detection method.

Ultrastructure of rat sciatic nerves

After pain behavioral tests at the 7 days after sham, HFS or SNI, the left sciatic nerves of rats (n=2–3 rats/group, 2 mm distal to the stimulated or injury point) were obtained and fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide solution at 4 °C. These samples were then dehydrated in graded ethanol series and embedded in Spurr’s resin between two slides coated with dimethyldichlorosilane (Sigma) in a 37 °C degree oven for 2 hours and then placed in 60 °C for 48 hours. The sciatic nerve sections (70 nm) were prepared, then observed and imaged with Tecnai G2 Spirit Twin electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR).

Pre-embedding immunoelectron microscopy (IEM)

A total of 5 male C57BL/6J mice (sham: n = 2 mice, HFS 7d: n =3 mice) at 8-week-old were used. Animals were anesthetized with 7.5% chloral hydrate (1.0 g/kg, i.p.) and perfused with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) for 1–2 min and then followed by 150 ml fixative solution for about 30 min. The fixative solution was consisted of 0.1% glutaraldehyde, 4% paraformaldehyde and 15% saturated picric acid in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.2). The lumbar enlargement of spinal cord was harvested and post-fixed in the same fixative solution but without glutaraldehyde for 3 h at 4°C. Spinal transverse sections were cut at a thickness of 50 μm on a vibratome and then stained using DAB immunohistochemistry method. After washed in PB and rinsed in 25% sucrose PB solution for 30 min, the sections were dipped in liquid nitrogen for 2 seconds and quickly rinsed in 0.05M Tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 7.2) for 5 min then incubated in 20% donkey serum in TBS for 30 min. After overnight incubation at 4 °C with goat anti-CGRP antibodies (Abcam, 1:150) in 2% donkey serum TBS solution, the spinal sections were then incubated at 4°C with biotin labeled donkey anti-goat antibodies diluted 1:100 in 2% donkey serum TBS solution overnight. Slices were incubated with HRP-Streptavidin (PK-6101, Vectorlabs) for 4 hours at room temperature and then treated with diaminobenzidine (DAB, SK-4100, Vectorlabs) and H2O2. After being rinsed in PB for 5 min three times, the slices were treated with 1% osmic acid in PB, dehydrated in 50% alcohol and dipped in 1% saturated uranyl acetate (70% alcohol solution) for 40 min. Then the sections were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol and embedded in Spurr’s resin between two slides coated with dimethyldichlorosilane (Sigma) in a 37 °C degree oven for 2 hours and then placed in 60 °C for 48 hours. Selected sections were cut and reconstructed with a blade and recut into serial ultrathin sections. To avoid the effect of densely stained myelinated axons on CGRP immunoreactivity, the sections were not incubated in lead citrate. These ultrathin sections (70 nm) were collected on 200-mesh copper grids for examination with a Tecnai G2 Spirit Twin electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR).

qRT-PCR

L4–5 DRGs were excised from each mouse and homogenized in TriZol. RNA was isolated using TriZol/chloroform extraction and cDNA was prepared from total RNA by reverse transcription reaction with PrimeScript RT Master Mix (RR036A, Takara). qRT-PCR was performed with CFX 96 touch3 (Bio-rad) using TB Green premix Ex Taq (RR820A, Takara). The conditions for fast qRT-PCR were as follows: 1 cycle of 95°C for 30s, 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, and 60°C for 30 s. At the end of the PCR, the samples were subjected to melting analysis to confirm amplicon specificity. Primers sequences are listed as follow: CSF1 Forward (5’-GTGTCAGAACACTGTAGCCAC-3’), CSF1 Reverse (5’-TCAAAGGCAATCTGGCATGAAG-3’); β-actin forward (5’-CCACACCCGCCACCAGTTCG-3’), β-actin reverse (5’-TACAGCCCGGGGAGCATCGT-3’). The relative CSF1 mRNA expression was were normalized to β-actin in the same group. The ratio of protein/β-actin from sham group were set as 1 baseline. The data from other groups show the fold with sham baseline.

Culture of DRG neurons

C57BL/6 mice (4~6wold) were made unconscious by CO2 and then decapitated immediately. After that, the DRGs were bilaterally dissected out and transferred to DMEM/F12 (Gibco). After DRGs were digested with 5 mL collagenase (3 mg, C9891 sigma) and trypsin (2 mg, T9201, sigma) mixture solution for 25 min, and the same volume of complete medium (DMED/F12 + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin and streptomycin 100×, Gibco) was added to stop the digestion. Single DRG cells were obtained. These cells were cultured in 0.01% PLL-coated (Poly-L-Lysine, P4832, sigma) 48well plates in cell culture medium: DMEM/F12 + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin and streptomycin + 1% glutamine (200 mM, G7513, sigma). Four hours later, the supernatant was carefully discarded, and new culture medium was added. Culture for 4 days and the cell can be treated for following experience: BDNF group contained 50 μg/ml recombinant mouse BDNF (248-BD, R&D systems); ANA-12 group contained 10 or 50 μM ANA-12 (a low molecular weight TrkB antagonist, Tocris), ANA-12 + CSF1 group was cultured with 10 or 50 μM ANA-12 1 h prior to BDNF, 0.5 μM 666–15 (a potent and selective CREB inhibitor, Tocris), 666–15 + CSF1 group was cultured with 0.5 μM 666–15) 1 h prior to BDNF; KCl group contained 40 mM KCl. Then DRG neurons were cultured in humid conditions and 5% CO2 at 37°C. At 24 hours after BDNF, KCl or vehicle (0.02% DMSO), the culture media were harvested for Western blot (WB) to show CSF1 release and the DRG neurons were fixed for CGRP immunofluorescence.

Acute spinal cord slice culture

The acute spinal cord slice culture was performed following the procedures described previously (Liu et al., 2017). Briefly, normal 4~6-week-old C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized with 10% urethane (1.5 g/kg, Sigma), then were plunged into 75% alcohol solution for 30 s. The spines were isolated quickly and put into 4°C precooled slice cutting buffer (2.5% 1 M HEPES in EBSS, Sigma). Under aseptic conditions, the transverse lumbar spinal cord slices were cut at 400 μm thickness with a vibratome (MA752, Campden) and then transferred onto 0.4 μm culture inserts (PIHP03050, Millipore) which were pre-equilibrated with 1 ml of culture medium. All culture media contained 50% MEM (Gibco), 25% EBSS (Sigma), 25% horse serum (Gibco), 6.5 mg/ml glucose (Sigma), 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 0.05% DMSO (Sigma). CSF1 group contained 1 μg/ml CSF1 (576406, BioLegend); SB203580 (Sigma) group contained 1 or 10 μM SB203580 (a selective inhibitor of p38 MAPK, Tocris), SB203580 + CSF1 group was cultured with 1 or 10 μM SB203580 1 h prior to CSF1. The spinal cord slices were cultured in humid conditions and 5% CO2 at 37°C. At 6 hours after CSF1 or vehicle (0.02% DMSO), the spinal cord slices were collected for immunofluorescence or WB, and the culture media were harvested for WB to show BDNF release.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean ± S.E.M. Unpaired Student’s t-test (2 tailed) were performed after confirming that the groups were normally distributed with equal variances. Pain behavior tests and electrophysiological data were analyzed by two-way repeated ANOVA, followed by individual post-hoc comparisons (post-hoc Tukey’s test or Fisher’s) to establish significance. Other changes of values of each experimental group were tested using one-way ANOVA, followed by individual post hoc comparisons (posthoc Tukey’s or Fisher’s test). Statistical significance was calculated using software OriginPro8.0 (OriginLab, USA). Level of significance is indicated with *or #P < 0.05, ** or ##P < 0.01, *** or ###P < 0.001.

Quantification of immunofluorescence staining

For the analysis of ATF3 or CGRP-positive cells in the DRGs, the DRG neurons was identified by adjusting brightness/contrast and all neuronal cells with a clear nuclear profile were counted using the ImageJ image processing and analysis program. 2–4 sections of L4 DRG from each animal were chosen at random with the group blinded. The percentage of ATF3 or CGRP-positive neurons in the DRG neurons was then calculated (Flatters and Bennett, 2006; Matsuura et al., 2013).

Fluorescent signal intensity was also quantified using relative optical density (RelOD) by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Images used for quantification represent serial optical sections obtained along the z-axis (z-stacks), using 25X, 40X, 63X plan-apochromatic water-immersion objective. For an unbiased representation of the images taken, all the parameters of laser power, pinhole size and image detection were kept constant for all samples. Based on Rexed laminae of the spinal cord, the analysis criteria of CGRP-immunoreactivity (IR) fibers density in the superficial layer is shown in Fig. 2c.The criteria of identification and quantification of the density of CGRP-positive boutons per lamina have been described in previous publications(Saeed and Ribeiro-da-Silva, 2012). Briefly, the fluorescent CGRP intensity in layer I and IIo, IIi and III & IV was respectively calculated and the intensity in layer I and IIo from WT sham tissues or control group was set as the 100% baseline. The RelOD of other protein expression was also measured by the same method. The intensity in L4 DRG from sham tissues or control group was set as the 100% baseline. The data from each of the other groups were normalized and compared with baseline. Three to five sections per mouse from 3–4 mice were randomly selected for each group.

TEM analysis

According to the Erlanger-Gasser Classification, peripheral nerve fibers are grouped based on the diameter of an axon: Aα (13–20 μm); Aβ (6–12 μm); Aδ (1–5 μm); C (< 1.5 μm). The diameters of myelinated axons were calculated on the total surface of the semithin sections of sciatic nerves using the g-ratio calculator plug-in developed for ImageJ software. Axons and nerve fibers were grouped into increasing size categories separated by 1 μm to calculate their distribution. The G ratios were measured as ratios of the axon diameter to the fiber diameter in equivalent 26 × 17 μm areas from each nerves previously described (!!! INVALID CITATION !!! (Bangratz et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2015)). Data for this study were collected from total of 4–6 micrographs of sciatic nerve fiber TEM cross-sections from 2–3 rats/group.

IEM analysis

Lamina II was identified by the paucity of myelinated fibers within the neuropil, which facilitated the determination of the laminae I/II, IIi and III/IV borders of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord when sections were observed in electron microscopes. Data for this study were collected from a total of 36 micrographs (2–3 micrographs/layer/mouse) of cross-sections of well-preserved CGRP+ immunoreactive elements from five animals. Measurements of labeled structures were made on electron micrograph negatives at 13,500–37,000 × magnification using a measuring magnifier calibrated in 0.2 mm gradations. Measurements of the number of CGRP positive (CGRP+) varicosities (Fig. 2e, in black circles) or synapses (arrows) in the different layers between sham and HFS 7d groups were made by two experimenters who were blinded to the treatment.

Analysis of CGRP Neurite length

The analyses of CGRP neurite lengths of cultured DRG neurons were determined on ImageJ software following the procedures described by Jun BK (Jun et al., 2015). The largely overlapped CGRP -positive (CGRP+) neurons were excluded to estimate. Using the NeuronJ plug-in, all the neurite length of CGRP+ DRG was measured, the average value calculated for 3–4 neurons of each image (20 X), and the mean neurite length derived from the 4–8 images average values per group (> 15 neurons/group). Neurites were traced manually from the soma outward, excluding those < 5 μm. All quantitative data were obtained by a blinded experimenter and normalized to the WT control.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-ATF3 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-188 RRID:AB_2258513 |

| Goat anti-Iba1 | Abcam | Cat# ab5076 RRID:AB_2224402 |

| Rat anti-NIMP-R14 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-59338 RRID: AB_2167795 |

| Goat anti-CGRP | Abcam | Cat# 36001 RRID: AB_725807 |

| Mouse anti-CGRP | Abcam | Cat# ab81887 RRID: AB_1658411 |

| Isolectin B4-FITC | Sigma | Cat# L2895 |

| Rabbit anti-Synaptophysin | Abcam | Cat# ab16659 RRID: AB_443419 |

| Rabbit anti-GAP43 | Abcam | Cat# ab128005 RRID:AB_11141048 |

| Rabbit anti-Substance P receptor | EMD Millipore | Cat# AB5060 RRID:AB_2200636 |

| Goat anti-CSF1 | R&D Systems | Cat# AF416 RRID:AB_355351 |

| Goat IgG | R&D Systerms | Cat# AB-108-C RRID:AB_ |

| Rabbit anti-CSF1R | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-692 RRID:AB_631025 |

| Rat anti-CD11b | Biolegend | Cat# 101202 RRID:AB_312785 |

| Rabbit anti-BDNF | Millipore | Cat# AB1534 RRID:AB_90746 |

| Rabbit anti- phospho-p38 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4511 RRID:AB_2139682 |

| Mouse anti-β-actin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3700 RRID:AB_2242334 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| D-AP5 | Tocris | Cat# 0106 |

| Lidocaine | Sigma | Cat# L7757 |

| Collagenase | Sigma | Cat# C9891 |

| Trypsin | Sigma | Cat# T9201 |

| Poly-L-Lysine | Sigma | Cat# P4832 |

| Glutamine | Sigma | Cat# G7513 |

| ANA-12 | Tocris | Cat# 4781 |

| 666-15 | Tocris | Cat# 5661 |

| SB203580 | Tocris | Cat# 1202 |

| CSF1 | Biolegend | Cat# 576402 |

| BDNF | R&D Systems | Cat# 248-BD |

| Tamoxifen | Sigma | Cat# T5648 |

| Diphtheria toxin | Sigma | Cat# C8286 |

| Urethane | Sigma | Cat# U2500 |

| Lidocaine | Sigma | Cat# L7757 |

| Fluoromount-G | Southern Biotech | Cat# 0100-01 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C57BL/6J | Jackson Laboratories | Cat# JAX:000664 RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664 |

| CX3CR1CreER/+ mice | Parkhurst et al., 2013 | Cat# JAX:021160, RRID:IMSR_JAX:021160 |

| BDNFflox/flox(BDNFTM3JAE/J) | Jackson Laboratories | Cat# JAX:004339, RRID:IMSR_JAX:004339 |

| R26iDTR/+ mice | Jackson Laboratories | Cat# JAX:007900, RRID:IMSR_JAX:007900 |

| Sprague–Dawley rats | Charles River Laboratory | Cat# 10395233, RRID:RGD_10395233 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Csf1 Forward: GTGTCAGAACACTGTAGCCAC |

Thermo Fisher Scientific | N/A |

| Csf1 Reverse: TCAAAGGCAATCTGGCATGAAG |

Thermo Fisher Scientific | N/A |

| β-actin Forward: CCACACCCGCCACCAGTTCG |

Thermo Fisher Scientific | N/A |

| β-actin Reverse: TACAGCCCGGGGAGCATCGT |

Thermo Fisher Scientific | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | National Inst. Of Health | http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/index.html, RRID:SCR_003070 |

| GraphPad Prism 7 | GraphPad | http://www.graphpad.com/RRID:SCR_002798 |

| OriginPro 8.0 | OriginLab, | http://www.originlab.com/index.aspx?go=Products/Origin, RRID:SCR_015636 |

| LTP program | WinLTP Ltd. and The University of Bristol, |

http://www.winltp.com,RRID:SCR_008590 |