Summary

The AAA ATPase katanin severs microtubules. It is critical in cell division, centriole biogenesis and neuronal morphogenesis. Its mutation causes microcephaly. The microtubule templates katanin hexamerization and activates its ATPase. The structural basis for these activities and how they lead to severing is unknown. Here, we show that β-tubulin tails are necessary and sufficient for severing. Cryo-EM structures reveal the essential tubulin tail glutamates gripped by a double spiral of electropositive loops lining the katanin central pore. Each spiral couples allosterically to the ATPase and binds alternating, successive substrate residues, with consecutive residues coordinated by adjacent protomers. This tightly couples tail binding, hexamerization and ATPase activation. Hexamer structures in different states suggest an ATPase-driven, ratchet-like translocation of the tubulin tail through the pore. A disordered region outside the AAA core anchors katanin to the microtubule while the AAA motor exerts the forces that extract tubulin dimers and sever the microtubule.

eTOC

Microtubule severing enzymes manage to break a polymer 25 nm in diameter, with stiffness comparable to Plexiglas®. Cryo-EM structures by Zehr et al. reveal that the severing enzyme katanin uses a double spiral in its central pore to grip the β-tubulin tail and pull the tubulin from the microtubule.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Microtubule arrays are sculpted by the action of effectors that regulate their constant polymerization and disassembly to execute diverse and essential cellular functions ranging from intracellular transport to cell division and differentiation. Microtubule-severing enzymes break microtubules in the middle and remodel the microtubule lattice by promoting the exchange of tubulin subunits with the soluble tubulin pool (reviewed in (McNally and Roll-Mecak, 2018)). Katanin was the first microtubule-severing enzyme discovered (McNally and Vale, 1993; Vale, 1991). Its activity is critical for the assembly and disassembly of cilia and flagella (Casanova et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2007), spindle formation, maintenance and size regulation (Loughlin et al., 2011; McNally et al., 2006; McNally et al., 2014; Mishra-Gorur et al., 2014), chromosome dynamics (Zhang et al., 2007), neuronal morphogenesis (Ahmad et al., 1999; Karabay et al., 2004; Mishra-Gorur et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2008) and plant phototropism (Lindeboom et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013). Katanin mutations lead to a spectrum of malformations of cerebral cortical development in humans, including microcephaly and lissencephaly (Bartholdi et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2014; Mishra-Gorur et al., 2014; Yigit et al., 2016).

Katanin is a AAA (ATPases associated with various cellular activities) ATPase. It consists of a catalytic p60 and regulatory p80 subunit. The catalytic subunit contains a single AAA ATPase cassette and has microtubule-stimulated ATPase and severing activities (Hartman et al., 1998; Hartman and Vale, 1999; McNally and Vale, 1993; McNally et al., 2000). ATP hydrolysis is required for severing (McNally and Vale, 1993). The regulatory subunit p80 enhances microtubule binding (McNally et al., 2000) and targets katanin to the centrosome (Hartman et al., 1998; Jiang et al., 2017; McNally et al., 1996; McNally et al., 2000; Mishra-Gorur et al., 2014) and microtubule crossovers (McNally et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017). The AAA ATPase domain is connected through a poorly conserved disordered linker to a microtubule interacting and trafficking (MIT) domain (Zehr et al., 2017) with weak microtubule-binding affinity (Iwaya et al., 2010).

Severing requires katanin hexamerization and the tubulin C-terminal tails (Hartman and Vale, 1999; Johjima et al., 2015; McNally and Vale, 1993). The latter are intrinsically disordered electronegative elements that project from the microtubule surface and regulate the recruitment of molecular motors and microtubule associated proteins (MAPs; (Roll-Mecak, 2019)). Katanin is monomeric at cellular concentrations in the absence of the microtubule substrate. The microtubule templates its hexamerization in the presence of ATP (Hartman and Vale, 1999). Katanin severs the microtubule by the progressive removal of tubulin subunits (Vemu et al., 2018). It was proposed that katanin extracts the tubulin subunits from the microtubule by repeated pulling on the α or β-tubulin tails (Roll-Mecak and Vale, 2008).

How katanin binds the microtubule and grips the tubulin tails, and how this in turn promotes katanin hexamerization and microtubule severing is not understood. Here, we demonstrate that the β-tail alone is sufficient to activate katanin, that long glutamate stretches in the C-terminal tail are critical for katanin ATPase activation, and present cryo-EM structures of the katanin hexamer in complex with a polyglutamate peptide in two different conformations at ~3.5 Å and 4.2 Å resolution, respectively. These reveal two electropositive pore loops that form a double spiral around the electronegative peptide substrate, with each spiral binding alternating residues. Functional studies indicate that the first spiral is critical for substrate-induced oligomerization and ATPase activation, and the second spiral for force generation. Whereas in other AAA ATPases the first pore loop coordinates only alternating substrate residues, our katanin structure shows that this pore loop contacts all substrate residues in the pore, hinting at increased processivity or force generation. Substrate residues bind pore loops contributed from adjacent protomers in the hexamer, ensuring tight coordination between substrate binding, oligomerization and ATPase activation. The substrate-binding pore loops are allosterically coupled to the ATP-binding site and structural elements involved in oligomerization. Thus, our structure lays bare how the tubulin tail promotes hexamer formation and activates katanin. Transition between two conformations with different ATP occupancies changes the hexamer from a right-handed open spiral into a closed ring and decouples one of the boundary protomers from the tubulin tail, providing insight into the ATPase-driven substrate movement that deforms and destabilizes the tubulin subunit and leads to its extraction, and ultimately, microtubule disassembly. Moreover, we show that a region in the disordered linker connecting the AAA core and MIT domains is essential for microtubule severing. Phosphorylation of Xenopus laevis katanin by Aurora B at a site nestled in this region inhibits katanin and regulates interspecies spindle length scaling (Loughlin et al., 2011). Thus, our structural and functional work reveals how tubulin tails template the assembly and ATPase activation of the katanin hexamer, and shows how katanin uses complex multivalent interactions with the microtubule through flexible and intrinsically disordered elements to generate the forces needed to extract tubulin subunits out of the microtubule.

Results

The β-tail preferentially activates katanin ATPase and is required for severing

ATP hydrolysis by katanin is activated by Arg fingers supplied in trans (Wendler et al., 2012; Zehr et al., 2017) and thus requires oligomerization. The microtubule promotes katanin hexamerization and stimulates ATPase (Hartman and Vale, 1999). The intrinsically disordered tubulin C-terminal tails are required for microtubule severing by katanin (Johjima et al., 2015; McNally and Vale, 1993) and they inhibit microtubule severing in trans (Bailey et al., 2015). We thus investigated whether tubulin tails in isolation can stimulate katanin ATPase. We find that katanin ATPase is stimulated preferentially by the β-tubulin tail (either βI or βIVb isoform): 3.5 versus 2.2-fold maximal stimulation by the β- versus α-tubulin tail (Figure1A). The critical role of the β-tail is supported by experiments with engineered recombinant human tubulin. We used total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy and analyzed the severing and binding of Atto488-labeled katanin with recombinant human α1A/βIII microtubules (Valenstein and Roll-Mecak, 2016; Vemu et al., 2016) missing either the α- or the β-tubulin tails. Loss of β-tails reduces severing close to background levels, while complete α-tail loss still supports robust severing (Figure 1B). Both tails however contribute to binding, with the β-tail having a larger contribution (Figure 1C). Severing reactions at 5x higher enzyme concentrations with microtubules missing β-tails do not rescue severing, indicating that defects in microtubule binding alone are not responsible for loss of severing activity. The low levels of severing still detected with α1A/βΙΙΙΔtail microtubules are due to the presence of residual uncleaved β-tails (~15% of tails, STAR Methods). The essential function of the β-tail for severing is also supported by experiments performed with unmodified microtubules (STAR Methods) where β-tails were removed by partial proteolysis: partial removal of β-tails while most of α-tails are intact reduces severing by 93%, while complete β-tail removal abolishes severing (Figure 1D and Figure S1A). Thus, while both tails contribute to microtubule binding and severing, the β-tail is necessary and sufficient for severing. The critical role of the β-tail in microtubule severing and binding was also observed for spastin (Valenstein and Roll-Mecak, 2016), indicating that it is a common substrate recognition strategy for microtubule severing enzymes. A previous study using S. cerevisiae microtubules missing either the α-or β- tails reported that both tails are required for severing and that neither contributed significantly to microtubule binding (Johjima et al., 2015). We do not have a clear explanation for this discrepancy, but it could be due to the lower katanin activity with the S. cerevisiae microtubules used in that study.

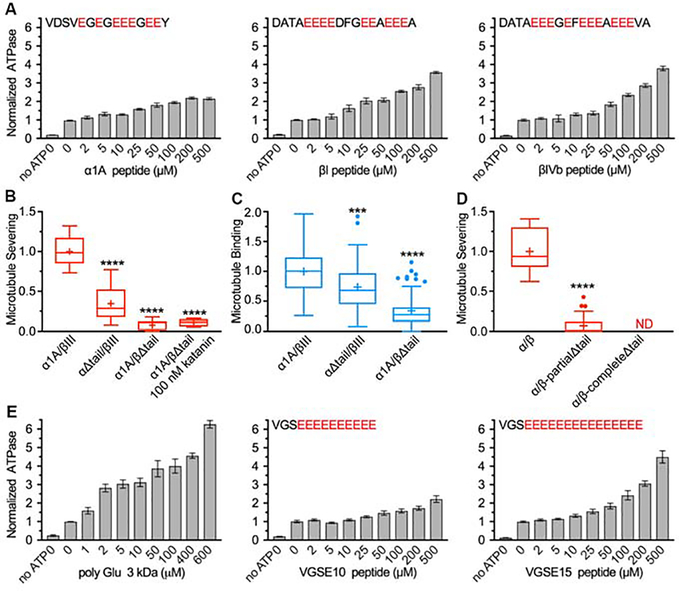

Figure 1. The β-tubulin tail preferentially activates katanin ATPase and is necessary and sufficient for microtubule severing.

(A) Katanin ATPase stimulation by tubulin tails and polyglutamate peptides. Peptide sequences indicated on top; n=4 independent experiments for each condition. Bars, mean and S.E.M. (B, C) Tukey plots of normalized microtubule severing (B) and binding (C) with recombinant α1A/βIII microtubules and α1A/βIII microtubules missing the α- or β-tails. Line indicates median, plus, average and whiskers, 1.5x interquartile distance; n=10, 11, 9 and 4 chambers for α1A/βIII, αΔtail/βIII, α1A/βΔtail and α1A/βΔtail at 100 nM katanin, respectively for severing; n=58, 55 and 63 microtubules for α1A/βIII, αΔtail/βIII and α1A/βΔtail, respectively for binding. (D) Tukey plots of normalized severing rates for subtilisin-digested unmodified microtubules whose mass spectra are shown in Figure S1A; n=14 and 48 microtubules for undigested and partially digested microtubules, respectively. ***, p-value ≤ 0.001; ****, p-value ≤ 0.0001 by two-tailed t-test (B) or Mann-Whitney test (C, D). See also Figure S1. (E) ATPase stimulation by polyglutamate peptides; n=4. Peptides sequences indicated on top. Bars, mean and S.E.M.

Given the high density of glutamates in the β-tails, we investigated whether polyglutamate itself can activate katanin ATPase, since microtubules polyglutamylated on their C-terminal tails are better katanin substrates in vivo (Sharma et al., 2007). Indeed, we find that polyglutamate chains with a mean molecular weight of 3kDa (~23 glutamates) robustly stimulate ATPase (Figure 1E). Interestingly, a thirteen-residue peptide with a ten-glutamate stretch offers modest stimulation, while an eighteen-residue peptide with a fifteen-glutamate stretch stimulates as strongly as either the βI− or βIVb-tail, indicating that substrate peptide length and electronegative charge are critical in activating katanin ATPase.

The tubulin tail is threaded through the katanin central pore

To investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying katanin activation by the tubulin tails, we determined the cryo-EM structure of the katanin catalytic subunit in complex with a polyglutamate peptide using single-particle cryo-EM (Figure 2). The use of the polyglutamate peptide solves the issue of degenerate sequence register of tubulin tails which are glutamate-rich but also comprise other residues (Roll-Mecak, 2015). To stabilize the katanin hexamers for structural studies, we used full-length C. elegans katanin p60 with a commonly-used mutation in the Walker B element that prevents ATP hydrolysis, but retains nucleotide binding (Hartman and Vale, 1999; Zehr et al., 2017). The cryo-EM data were refined and classified without imposing symmetry, yielding two reconstructions of distinct conformations: spiral and ring at 3.5 Å and 4.2 Å resolution (FSC = 0.143 criterion), respectively, with the best regions resolved at 3.0 Å (Figures 2, S2 and S3, Table S1, and STAR Methods). In the spiral conformation, the six protomers follow a right-handed spiral with a ~60° twist and ~ 5 Å translation per protomer such that the boundary protomers P1 and P6 are separated by a 40 Å gate, as seen in the katanin structure without substrate (Zehr et al., 2017) and similar to other AAA ATPases (Gates et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2016; Su et al., 2017; White et al., 2018). In the ring conformation, the boundary protomer P1 is loosely coupled to protomer P2 and interacts with the boundary protomer P6 closing the AAA ring. Both structures display prominent density for the polyglutamate peptide in the central pore. The 3.5 Å map was of sufficient quality to model ~98 % of the katanin AAA domain, the C-terminal region of the linker and the polyglutamate peptide. No density was visible for the rest of the linker and the MIT domain, consistent with their flexibility as previously shown (Zehr et al., 2017).

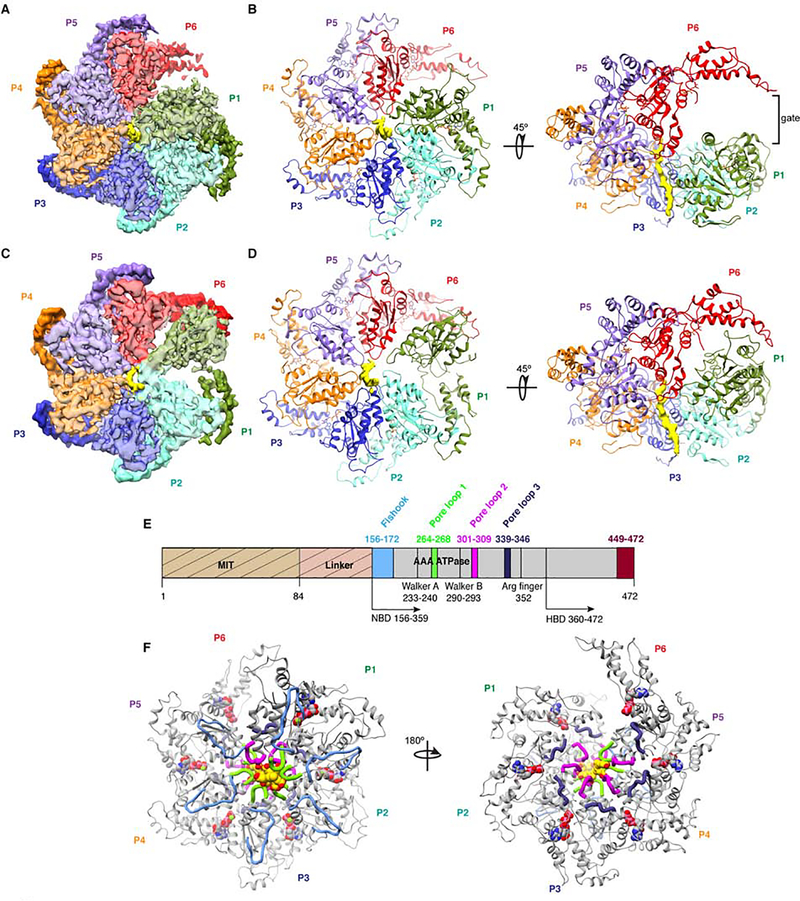

Figure 2. Cryo-EM structures of the katanin hexamer with substrate peptide bound in its central pore in two conformations.

(A) Cryo-EM map of the katanin hexamer in the spiral conformation with protomers arranged in a right-handed spiral around the substrate peptide. Protomer P1, green; P2, cyan; P3, blue; P4, orange; P5, purple; P6, red; substrate peptide, yellow. NBD and HBD shown in light and dark hue, respectively. (B) Atomic model of the katanin hexamer, protomers colored as in (A). Density for the polyglutamate peptide in yellow. (C) Cryo-EM map of the katanin hexamer in the closed ring conformation with the P1 and P6 gate closed. Colors as in (A). (D) Atomic model of the katanin hexamer, colored as in (A). Arrows indicate rotation angles between views. (E) Domain diagram of katanin p60; MIT domain, beige; linker, pink; fishhook linker element, light blue; AAA domain, gray; pore loop 1, green; pore loop 2, magenta; pore loop 3, purple; α11-α12, helix 12 and the C-terminus, dark red. Disordered segments not visible in reconstruction marked with hatches. Residue numbers for C. elegans katanin. (F) Atomic model of the katanin hexamer with structural elements colored as in (E). See also Figures S2 and S3 and Table S1.

Each AAA domain consists of a nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and a helix-bundle domain (HBD) arranged like two lobes of a crescent. Oligomerization interfaces between successive protomers are formed via canonical AAA ATPase contacts (Lenzen et al., 1998) and are enhanced by additional contacts between elements unique to katanin. These are an essential fishhook-shaped element in the linker immediately preceding the AAA ATPase cassette, and the C-terminal helix α12 and the α11-α12 linker which form a stabilizing belt around the hexamer (Figure 2E,F). The quality of our map allowed de novo atomic building of the fishhook element which comprises the C-terminal part of the linker connecting the AAA and MIT domains. For a given protomer, the convex face of its NBD interacts with both the NBD and HBD of one neighboring protomer, while its concave face interacts with the NBD of the other neighbor (Figure 2A). Each of the protomers in the spiral conformation is bound to ATP (Figures S4A,B) and are superimposable upon each other with a Cα RMSD of 0.6 Å (Figure S4A). The Arg finger 352 that activates the ATPase in trans is in a catalytically competent conformation (within ~2.6 Å from the ATP γ-phosphate) in all nucleotide binding sites with the exception of that in P6 which is incomplete and open to solvent (Figures 2B and S4B). The polarity of the substrate peptide in the cryo-EM map could not be determined with certainty at this resolution (Figure S5A,B) and was assigned based on functional studies and analogy with other AAA ATPases (VPS4 (Han et al., 2017), HSP104 (Gates et al., 2017), the proteasome (de la Pena et al., 2018)) with the fishhook encountering the peptide substrate from the C- to the N-terminus (Figures 2 and S5A). The polarity of the peptide through the central pore might not be dictated by pore residues alone but by additional contacts with the microtubule (see Discussion). Even though the mean length of the glutamate chain used in the reconstruction is 23, only 14 glutamates are visible in the pore. The footprint of 14 glutamates in the pore explains the poor ATPase stimulation by a shorter thirteen-residue peptide with ten glutamates (Figure 1E).

Two conserved pore loops form an interconnected double spiral around the tubulin tail

The polyglutamate chain, spanning ~43 Å, is threaded in an extended conformation in the ~20 Å-wide central pore of the hexamer and coordinated by two electropositive conserved pore loops (pore loop 1 and 2; Figure 2E,F). Pore loop 1 runs perpendicular and pore loop 2 parallel to the substrate peptide axis. Together they form a double-helical spiral around the substrate and utilize two different modes of interaction with the extended polyglutamate chain (Figures 3A and S5C,D). Neither loop is ordered in the crystal structure of monomeric katanin (Nithianantham et al., 2018; Zehr et al., 2017). Pore loop 2 is also unresolved in the katanin hexamer without substrate (Zehr et al., 2017), indicating a disorder-to-order transition upon substrate binding. Pore loop 1, coordinates the i-th and (i+1)-th residues (Figure 3B,C,D,E), while pore loop 2 coordinates only (i+1)-th glutamates in the substrate (Figure 3C,D,E). The involvement of pore loop 1 for coordination of successive residues has not been observed in other AAA ATPase structures.

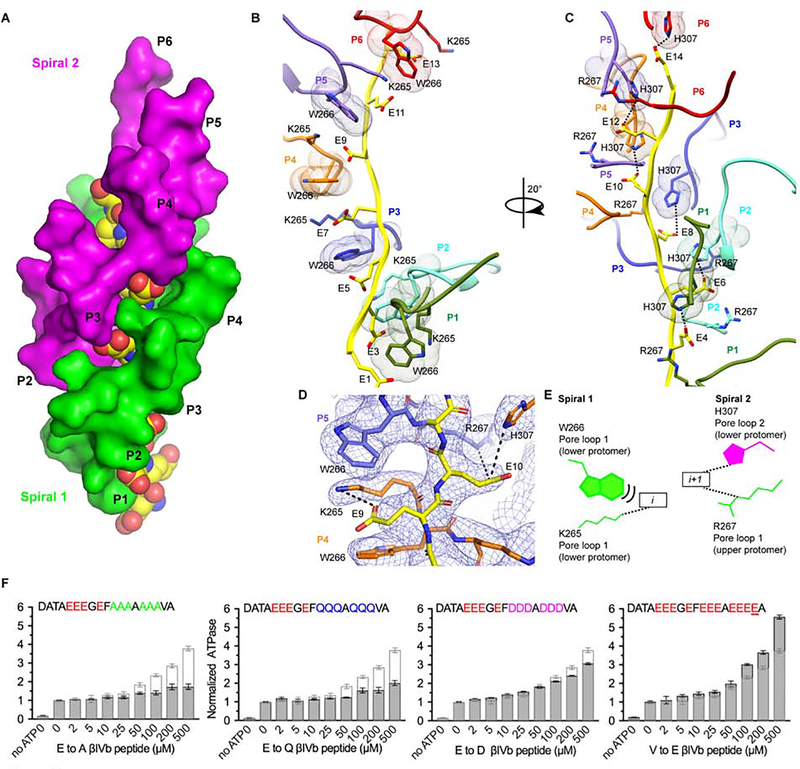

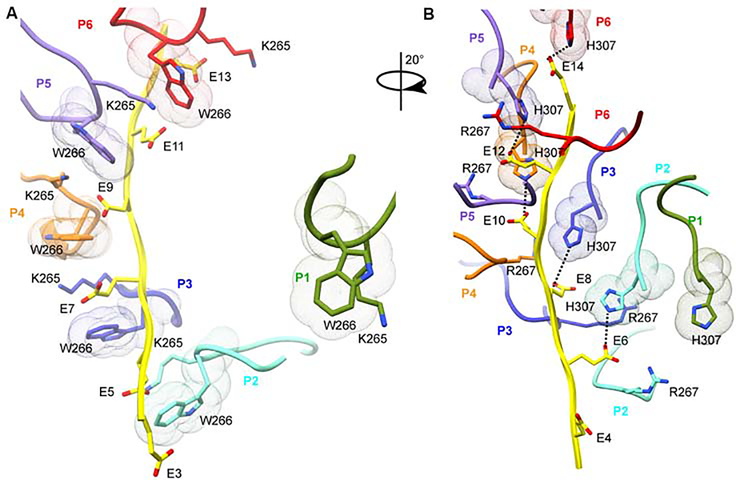

Figure 3. Two conserved pore loops form an electropositive double spiral around the negatively-charged substrate.

(A) Two pore loops form a right-handed double-spiral around the substrate. The two spirals are shown as molecular surfaces colored green and magenta for spiral 1 and 2, respectively. Substrate peptide colored in yellow and shown as spheres colored by heteroatom. (B) Pore loop 1 residues W266 and K265 in P1 through P6 are arranged in a spiral and coordinate i-th residues in the substrate. Pore loops are colored as the protomer they belong to as in Figure 2. Dots represent van der Waals surfaces. View is 90˚ rotated from that in (A). (C) Pore loop 2 residues H307 in P1 through P6 form a second spiral and coordinate (i+1)-th residues in the substrate. (D) Enlarged view of the pore loop-substrate interactions. Cryo-EM map shown as blue mesh. Dashed lines indicate H-bonds. (E) Schematic illustrating pore loop-substrate interactions. Pore loop 1 and 2 residues shown in green and magenta, respectively; the two boxes denote alternating substrate residues. Van der Waals interactions and H-bonds indicated by stacked and dashed lines, respectively. All H-bonds denote distances less than 4.5 Å. (F) ATPase stimulation by βIVb-tubulin tail mutant peptides. Peptides sequences indicated on top. Light grey outline shows ATPase stimulation by the wild-type βIVb-tail peptide for comparison; n=4 replicates. Bars, mean and S.E.M. See also Figures S4, S5 and S8.

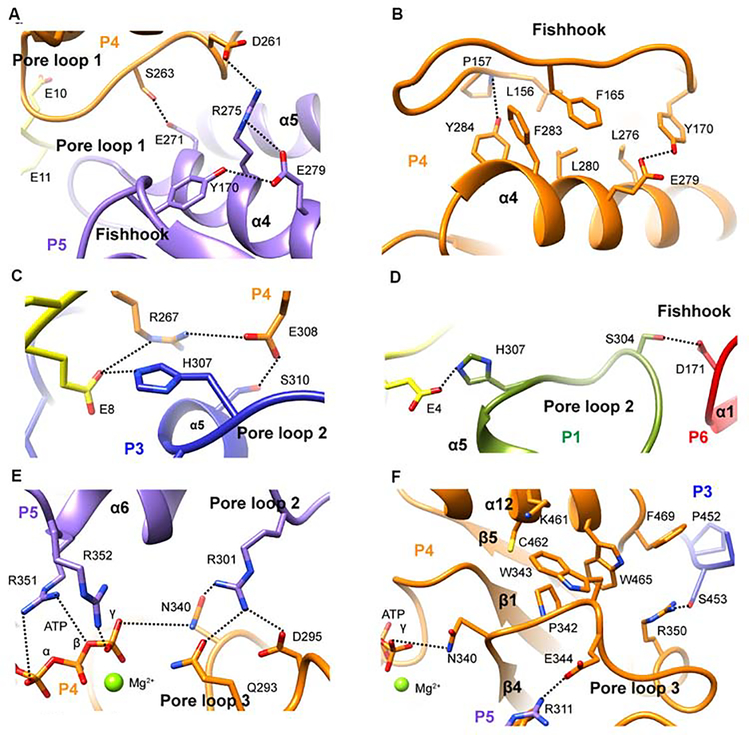

The i-th glutamates are sandwiched between the aromatic paddles of conserved Trp266 in pore loop 1, within H-bonding distance of invariant Lys265 (Figure 3B). The use of an aromatic residue in pore loop 1 to bind substrate is a common feature of AAA ATPases (Olivares et al., 2016; Schlieker et al., 2004) and can support sequence independent substrate translocation through the pore. Trp266 intercalates between Lys265 from the same protomer and the lower adjacent protomer and makes CH-π and cation-π interactions that facilitate oligomerization interactions throughout the entire spiral 1, serving as a conduit for substrate driven oligomerization. Furthermore, both the helical turn leading into pore loop 1 and helix α4 which immediately follows pore loop 1 are involved in interprotomer interactions. For example, conserved Asp261 and Ser263 immediately preceding pore loop1 are both within H-bonding distance from invariant Arg275 and Glu271 in the upper protomer, respectively (Figures 4A and S6). Fishhook residues 156–172 and helix α4 pack against each other through a ridge of intercalating aromatic residues and also engage in H-bonds (Figure 4B). Invariant Tyr170 which packs against Leu276 in α4, H-bonds with conserved Glu279 and interacts with Arg275 which in turn is within H-bonding distance to Asp261 in the adjacent lower protomer (Figure 4A,B).

Figure 4. Katanin hexamer assembly is allosterically coupled to substrate engagement and nucleotide sensing.

(A) Interprotomer contacts mediated by pore loop 1 proximal elements. (B) Hydrophobic interface between fishhook and helix α4. (C) H-bonding network coupling substrate binding to interprotomer interactions. (D) Substrate driven non-canonical interactions between gate protomers P1 and P6. (E) Pore loop 3 N340 couples ATP sensing with substrate binding pore loop 2 through R301. (F) Pore loop 3 residues pack against helix α12 and couple nucleotide sensing to hexamerization. H-bonds indicated by dashed lines. Protomers colored as in Figure 2.

The (i+1)-th glutamates are coordinated by invariant Arg267 in pore loop 1 and His307 in pore loop 2, contributed by adjacent protomers (upper and lower protomer, respectively), thus mediating substrate driven interprotomer coordination (Figure 3C,D and E). Arg267 also forms a salt bridge with invariant Glu308 in pore loop 2 in the same protomer (Figure 4C) which in turn H-bonds to invariant Ser310 in the adjacent lower protomer. Ser310 is part of α5 and immediately follows pore loop 2. Thus, Arg267 and Glu308 likely participate in substrate driven coordination between the two pore loops. Pore loop 2 also mediates non-canonical interactions between boundary protomers P1 and P6 due to the spiral arrangement of the hexamer. Specifically, pore loop 2 Ser304 in protomer P1 is H-bonds with Asp171 in the P6 fishhook (Figure 4D). Thus, P1 and P6 are engaged in substrate driven communication, but not through the canonical NBD-HBD interface.

Consistent with its dual role in oligomerization and substrate recognition, mutation of Trp266 or Lys265 in pore loop1 reduces basal and microtubule stimulated ATPase (59% and 42%, respectively, for basal ATPase and 64% and 58% for microtubule stimulated ATPase) while completely inactivating severing (Figure 5A,B). The more dramatic effect on severing also indicates its key function in force generation and substrate translocation. Moreover, mutation of either Trp266 or Lys265 results in almost complete impairment of ATPase stimulation by an isolated β-tubulin peptide (Figure 5C). Mutation of Tyr170 involved in the interaction network between the fishhook and pore loop 1 adjacent elements reduces ATPase to background levels and abolishes severing (Figure 5A,B). Consistent with its role in stabilizing the hexamer as well as promoting substrate driven oligomerization, mutation of Arg267 to alanine leads to 51% reduction in basal ATPase (Figure 5A), but complete impairment of ATPase stimulation by the β-tubulin tail in isolation (Figure 5C) and ~ 60% reduction in microtubule stimulated ATPase (Figure 5A). The R267A mutant is inactive in microtubule severing (Figure 5B; (Shin et al., 2019)). Interestingly, mutation of Arg267 to glutamate also inactivates β-tail peptide stimulated ATPase and severing (Figure 5A,B,C), but has a minimal effect on basal ATPase indicating that the van der Waals interactions supplied by the aliphatic portion of the arginine side chain are sufficient for katanin oligomerization, but that the H-bond network of this residue is important for ATPase stimulation and force production. All katanin sequences have an arginine at this position (Figure S6). This difference could reflect a higher affinity of katanin for the glutamate rich tubulin tails. Spastin has a valine at this position, while VPS4 which is closely related to spastin and katanin but acts on ESCRTIII polymers has a methionine (Han et al., 2017).

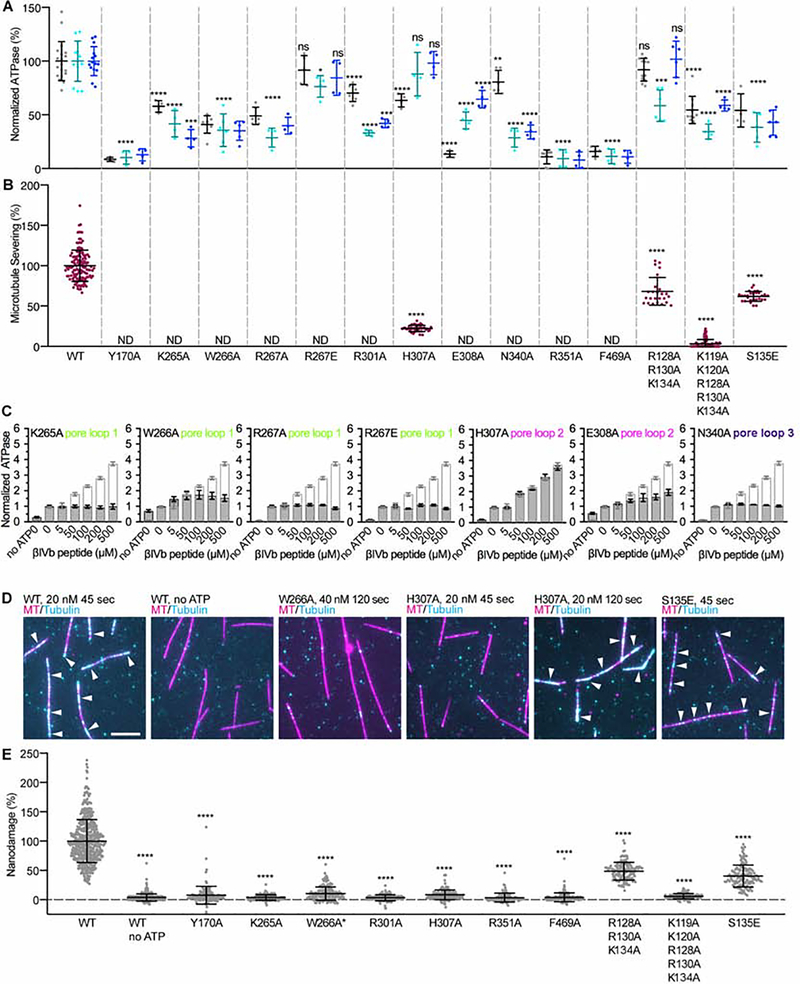

Figure 5. Microtubule severing, ATPase and tubulin extraction activity of structure-guided katanin mutants reveal molecular determinants for tubulin tail and microtubule recognition.

(A) Basal ATPase of katanin mutants (grey) and microtubule stimulated ATPase with 2 μM (cyan) or 4 μM microtubules (blue), normalized to wild-type katanin. n≥4 independent experiments for each condition. Bars, mean and S.D. (B) Severing activity of katanin mutants normalized to wild-type; n=132, 43, 25, 109, 28 microtubules for wild-type, H307A, R128R130K134AAA, K119K120R128R130K134AAAAA and S135E, respectively. n≥3 chambers for each mutant. ND, no severing activity detected. (C) ATPase stimulation of structure-based katanin mutants by βIVb-tail peptide; n=4 independent measurements. Light grey outline shows ATPase stimulation by wild-type katanin for comparison. Bars, mean and S.E.M. (D) Microtubules (magenta) were immobilized in the chamber and incubated with 20 nM katanin wild-type or mutants, followed by incubation with 1 μM HiLyte488-tubulin (cyan) (STAR Methods). White arrows indicate incorporation of HiLyte488-tubulin into nanodamage sites. Scale bar, 5 μm. (E) Average fluorescence intensity of incorporated tubulin normalized to wild-type. W266A was tested in conditions different from wild-type and all other mutants at 40 nM katanin 120 sec; n=477, 448, 123, 155, 157, 151, 148, 93, 160, 125, 118, 122 microtubules for wild-type, wild-type without ATP, Y170A, K265A, W266A, R301A, H307A, R351A, F469A, R128R130K134AAA, K119K120R128R130K134AAAAA and S135E, respectively. Bars in A, B, E, mean and S.D. Bars in C, mean and S.E.M; ns, p-value > 0.05; **, p-value ≤ 0.01, ***, p-value ≤ 0.001; ****, p-value ≤ 0.0001 by two-tailed t-test in (A), or Mann-Whitney test (B,E). See also Figures S6 and S7.

The Arg267 H-bonds both with the substrate and invariant Glu308 in pore loop 2 (Figure 4C). Mutation of Glu308 to alanine reduces basal ATPase by 87%, indicating an oligomerization defect (Figure 5A). This mutant also shows impaired microtubule stimulated ATPase (Figure 5A) and very poor ATPase stimulation by a β-tail peptide (Figure 5C), consistent with defects in tubulin-tail-driven oligomerization and ATPase activation. Mutation of Glu308 to Ala inactivates severing (Figure 5B). Its mutation to Lys inactivates katanin in C. elegans (Clark-Maguire and Mains, 1994).

The elemental step in microtubule severing is the extraction of tubulin dimers out of the microtubule (Vemu et al., 2018). Previously we showed that the nanodamage introduced by severing enzymes spastin and katanin can be repaired through the incorporation of fresh tubulin subunits into the microtubule. These healing sites increased in intensity and density with enzyme incubation time or enzyme concentration (Vemu et al., 2018). Thus, we tested whether our mutants are able to remove tubulin dimers out of the microtubule in the eventuality that they are too impaired to progress to a mesoscale severing event in our assays. We incubated microtubules with katanin in the presence or absence of ATP, then removed the enzyme and perfused in fluorescent tubulin of a different color to initiate microtubule healing (Figure 5D). These assays showed that both the Trp266A and Lys265 mutants are also inactive in generating microtubule nanodamage (Figure 5D,E). Mutation of Tyr170 in the fishhook also reduces tubulin extraction to background levels (Figure 5E).

Mutation of invariant His307 in pore loop 2 to alanine has a modest effect on basal ATPase and no effect on substrate stimulated ATPase activity (Figure 5A,C), but reduces severing by 78% (Figure 5B) indicating a dominant role in translocating the substrate and not oligomerization and ATPase activation. Nanodamage activity is also severely impaired for this mutant (Figure 5D,E) and can be observed only at longer incubation times (Figures 5D and S7B). The unimpaired microtubule stimulated ATPase, in contrast to the strong effect of pore loop 1 mutations, suggests that pore loop 1 is dominant in the initial substrate driven hexamerization and ATPase activation.

Tubulin tail features important for katanin recognition

Glutamate recognition is mediated by both, van der Waals interactions with Trp266 and Lys265, and H-bonds with the carboxylate through Lys265. Consistent with this, mutation of six glutamates in a βIVb-tail peptide to alanine or glutamine significantly decreases substrate-stimulated ATPase, while mutation of a single residue from valine to glutamate increases stimulated ATPase ~1.5 fold compared to wild-type (Figure 3F). A shorter polyglutamate peptide (ten versus fifteen glutamates) is less effective stimulating ATPase, consistent with the 14-residue substrate footprint in the pore (Figures 1E and 3A,B,C). Mutation of glutamates to aspartates leads to a modest decrease in substrate activated ATPase (Figure 3F), consistent with the fact that the Asp sidechain can still accommodate, albeit weaker, van der Waals interactions with Trp266 and H-bonds with pore loop residues Lys265 and His307. The strong negative effect of mutating to glutamines indicates the importance of electrostatic interactions for the specific recognition of the tubulin tail by katanin (Figure 3F), consistent with the strong dependence of severing on ionic strength (Figure S1B). Moreover, we also find that the C-terminal tails of βII and βIII-tubulin isoforms stimulate ATPase similarly to those of βI and IVb, but the βV-tail, which has one fewer glutamate, shows ~30% weaker stimulation (Figures S8A and 1A). The positively charged lysine at the βIII C-terminus has no negative effect on ATPase stimulation, likely because the 14-residue footprint in the pore is N-terminal to this lysine, and the βIII tail is long enough to accommodate katanin binding. Thus, taken together, these functional data indicate that the negative charge density in the tubulin tail is critical for katanin recognition.

We then used our katanin-polyglutamate peptide complex structure to model the binding of the β-tail in the katanin pore. Briefly, we used our experimentally derived map and modeled the side chains of either the βI or βIVb-tubulin tails. We then subjected these models to energy minimization (STAR Methods). The resulting models show the recognition of the β-tails by pore loop spirals 1 and 2 (Figure S8B,C and Data S1) with good geometry and no steric clashes (STAR Methods). The β-tail sidechains are sandwiched between the Trp266 paddles of pore loop 1 and the His307 sidechains of pore loop 2. However, for non-glutamate residues, stabilizing H-bonds with the carboxylates are lost and the smaller sidechains have fewer packing interactions (Figure 3E), consistent with the positive correlation between the extent of ATPase activation and glutamate number within a 14-residue span that interacts with the katanin pore. We then analyzed the resulting intermolecular contacts between the βIVb-tail and katanin (STAR Methods) using an algorithm that takes into account the number of interatomic contacts at the peptide-protein interface, classifies them into polar/apolar/charged interactions, and combines this information with the properties of the non-interacting surface, i.e. the surface not in direct contact with the peptide, which also influences the energetics of the bimolecular interaction (Vangone and Bonvin, 2015; Xue et al., 2016). We extended this analysis to mutational perturbation of modeled βIVb-tail-katanin complexes, employing the mutant peptides used in our ATPase assays. This algorithm indicates that mutation of the six glutamates to alanine in the βIVb-tail results in an unfavorable ΔΔGcalc of 2 kcal/mol, while mutation to glutamine results in an unfavorable ΔΔGcalc of 1.2 kcal/mol (Table S2), consistent with the negative effects on katanin ATPase stimulation (Figure 3F). Moreover, a polyglutamate peptide shows a favorable ΔΔGcalc of −1.3 kcal/mol, consistent with the stronger ATPase stimulation by this peptide compared to the βIVb-tail (Figure 1E). Lastly, the ΔΔGcalc of the aspartate mutant βIVb peptide compared to the wild-type is 0.5 kcal/mol, consistent with the small deficit in ATPase activation (Figure 3F). Lastly, the ΔΔGcalc between the βI and βIVb-tubulin tails is only 0.3 kcal/mol (Table S2), consistent with the comparable ATPase stimulation by these peptides (Figure 1A). Thus, our structure-based modeling indicate that the same recognition principles evident in our katanin-polyglutamate complex structure apply for the native β-tubulin tails.

Tubulin tail activated allosteric assembly of the katanin hexamer

The ATP binds at the hinge between the NBD and HBD in a composite binding site formed by residues from adjacent protomers (Figures 2 and S4A). Similar to other AAA ATPases, the base is coordinated in cis while the phosphates are coordinated in trans by the adjacent upper protomer: Arg351 coordinates the α and β-phosphates, Arg352 (the Arg finger) coordinates the γ-phosphate (Figures 4E and S4B,D). Mutation of Arg351 inactivates both basal and microtubule stimulated ATPase and abolishes severing (Figures 5A,B and S7A) as well as nanodamage activity (Figure 5E). The substrate is directly coupled to the γ-phosphate through the catalytic glutamate Glu293 (Gln293 in our structure) which is within H-bonding distance to invariant Arg301 in pore loop 2 of the adjacent upper protomer (Figure 4E).

A third solvent exposed loop (pore loop 3, residues 339–346) is positioned perpendicular to pore loop 2. It does not interact with substrate directly but couples ATP binding with pore loop 2 and elements involved in oligomerization. Specifically, conserved Glu344 in loop 3 forms a salt bridge with invariant residue Arg311 from the adjacent upper protomer and located immediately C-terminal to pore loop 2 (Figure 4F). Invariant Asn340 which H-bonds with invariant Arg301 in pore loop 2 of the adjacent upper protomer, is also within H-bonding distance to the γ-phosphate, and thus well-positioned to sense nucleotide state and couple it to substrate binding (Figure 4E,F). Consistent with this role, the βIVb-tail peptide does not stimulate the ATPase of a Asn340 to alanine mutant, while the basal ATPase is minimally perturbed (Figure 5C,A). This mutant also has severely impaired microtubule stimulated ATPase (Figure 5A) and is inactive in severing (Figure 5B). Likewise, mutation of Arg301 reduces basal ATPase by only 30%, but has a more dramatic effect on microtubule stimulated ATPase (67% reduction) and abolishes microtubule severing and tubulin extraction activity (Figures 5A,B,E and S7B). The complete impairment in tubulin extraction suggests that in addition to substrate mediated oligomerization interactions this residue is critical for force generation.

Pore loop 3 is also coupled to helix α12 engaged in oligomerization (Figure 4F). Notably, invariant Trp343 from pore loop 3 packs against conserved Lys461 in α12 and makes CH-π interactions with the aromatic ring of invariant Trp465 also in α12. Trp465 packs against invariant Phe469 in α12 which mediates contacts with the α11-α12 linker from the adjacent protomer. Mutation of Phe469 to alanine reduces basal and stimulated ATPase, tubulin extraction and microtubule severing activity to background levels (Figures 5A,B,E and S7A). Arg350 immediately preceding Arg351 and Arg352 involved in phosphate binding, packs against Trp465 and Phe469, and H-bonds to Ser453 in the adjacent lower protomer (Figure 4F), thus connecting the C-terminal helix with the phosphate binding pocket. Invariant Pro342 in pore loop 3 restricts the position of Trp343 and at the same time makes van der Waals interactions with Cys462 in helix α12. Thus, our structure reveals how stimulation of katanin hexamer assembly by the tubulin tail is mediated by a conserved allosteric network of residues that couple the ATP binding site with substrate binding loops and oligomerization elements.

Nucleotide state decouples the boundary protomer from substrate

In addition to the spiral conformation, our 3D classification revealed two particle classes in which the hexamer is in a ring conformation with the P1 and P6 gate closed. Combining these two classes (class 3 and class 9, Figure S2) yielded a 3.6 Å reconstruction in which protomers P2-P6 are well-defined and at high-resolution and the P1 protomer is poorly resolved. Refinement of only class 3 yielded a reconstruction with an overall lower resolution of 4.2 Å, but with a better resolved P1 protomer (Figures 2C,D and S3). In the ring conformation, P2 through P6 retain the helical arrangement observed in the spiral conformation (~5 Å rise and ~60° twist per protomer as for P1 through P6 in the spiral conformation), but P1 deviates from this spiral symmetry (Figure 2C,D) and shows a high degree of flexibility (Figure S4E). P1 is connected to P2 through interactions mediated mostly by the HBD. Its NBD is disengaged from P2 except for minimal contacts through pore loop 2. Consistent with this, P2 through P6 contain well-defined densities for ATP (both in the ~3.6 Å and 4.2 Å reconstructions) with the arginine fingers contacting phosphates directly (Figure S4C,D) while the P1 NDB is nucleotide-free (Figure S4D). Multi-body refinement of P1 or the P1 NBD as a separate body from the other protomers in the AAA ring did not reveal a dominant eigenvector and did not significantly improve the density for this protomer, indicating its overall flexibility (STAR Methods; Figures S2 and S4E). This protomer is also more mobile and is nucleotide free in other AAA ATPases structures bound to substrate (Han et al., 2017; Puchades et al., 2017; White et al., 2018).

The P1 NBD moves around the hinge with the HBD which is loosened by the lack of nucleotide. As a result, the P2 arginine fingers are positioned ~11 Å away from the P1 nucleotide binding site (Figure S4G). The P6-P1 interface is in a near canonical configuration with a more relaxed interface between the NBDs and also in an ATPase inactive configuration with the arginine fingers positioned ~11 Å away from the γ-phosphate in P6 (Figure S4F). As a result, P2 through P6 which are bound to ATP contact the substrate with their two pore loops forming a double-helical spiral around the peptide substrate (Figure 6A,B). In contrast, both pore loops 1 and 2 in P1 are disengaged from the substrate peptide and more than ~ 20 Å away from it. Thus, our structures of the substrate bound katanin hexamer in a spiral and ring conformation reveal that the transition between these two states uncouples the substrate from the boundary lower protomer P1. We speculate that the movement of the P1 boundary protomer pulls the tubulin tail away from the microtubule surface and destabilizes lattice contacts made by the tubulin subunit.

Figure 6. Pore loops 1 and 2 in boundary protomer P1 are disengaged from the substrate in the ring conformation.

(A) W266 and K265 (pore loop 1) in protomers P2 through P6 are arranged in a right-handed spiral and coordinate every other residue in the peptide. Pore loop 1 in P1 is disengaged from the substrate. (B) H307 (pore loop 2) and R267 (pore loop 1) from protomers P2 through P6 form a second spiral that coordinates the substrate. Pore loop 2 in P1 is disengaged from the substrate. Pore loops colored as the protomer they belong to as in Figure 2. H-bonds indicated by dashed lines. Arrow indicates rotation angle between views. See also Figure S4.

A positively-charged disordered linker region is critical for severing

Our previous small angle X-ray scattering data (Zehr et al., 2017) showed that the katanin AAA core is connected to the MIT domains through a flexible linker ~80 Å long. As many microtubule-associated proteins are unstructured but characterized by positively charged residue clusters (Amos and Schlieper, 2005), we analyzed the katanin linker and found a stretch of lysine and arginine residues (Figure S6). While the exact location and sequence of these residues is not strictly conserved, all katanin sequences contain clusters of positively charged residues at similar locations in their linkers (Figure S6). A triple mutation of Arg128Arg130Lys134 to alanine did not affect basal ATP activity, but impaired microtubule stimulated ATPase at lower microtubule concentrations. The ATPase was restored to wild-type levels at higher microtubule concentrations, indicating a defect in microtubule binding (Figure 5A). Consistent with this, the Arg128Arg130Lys134Ala triple mutant shows a 32% and 51% reduction in severing and tubulin extraction activity, respectively (Figure 5B,E). These data explain results from earlier genetic studies in C. elegans that showed that mutation of either Gly126 or Arg128 decrease katanin activity (Clark-Maguire and Mains, 1994). The effect of the Gly126 mutation suggests that the local conformation in this region is also important. Mutation of two additional positively charged residues further to the N-terminus, Lys119 and Lys120, reduces both basal and microtubule stimulated ATPase by ~50% (Figure 5A) and reduces severing by 97% (Figure 5B). Tubulin extraction activity is at background levels (Figure 5E), but is detected with longer incubation times or higher enzyme concentrations (Figure S7B), concentration and time regimes in which wild-type katanin disintegrates the microtubule even before the perfusion into the microscopy chamber is finished. The disproportionate effect on severing over ATPase indicates that these linker contacts with the microtubule are needed for efficient force generation, likely providing the resistance against which the AAA motor pulls the tubulin tail.

Our results indicate that both microtubule binding and mechanochemical coupling are impaired when positively-charged residues are mutated in the linker, with K119 and K120 having the most drastic effect. Thus, elements outside the structured AAA and MIT domains are critical for severing. Interestingly, Ser135 which was identified as an Aurora B kinase phosphorylation site and a negative regulator of severing activity of Xenopus laevis katanin (Loughlin et al., 2011; Whitehead et al., 2013) is within the second cluster of positively charged residues. Ser residues are present in equivalent positions in other katanin homologs (Figure S6). Mutation of the equivalent Ser to a phosphomimetic residue (Ser135Glu) in C. elegans katanin causes a ~50% decrease in ATPase (Figure 5A) as well as microtubule severing and nanodamage activity (Figures 5B,D,E and S7A). Thus, the introduction of negative charges in this linker region inhibits katanin.

We wanted to see whether the importance of linker residues for katanin activity extends to the closely related microtubule-severing enzyme spastin. The spastin linker also contains clusters of positively-charged residues (Figures S7C,D). Mutations of the N-terminal positively-charged cluster Arg110Lys111Lys117Arg118 reduces spastin severing activity by ~50% (Figure S7E). Mutagenesis of a second cluster of positive residues in the middle of the linker Arg159Arg160Arg166Arg172Arg174 to alanine reduces spastin severing by ~70%. A spastin mutant containing all the above-mentioned mutations shows no detectable severing activity (Figure S7E). Severing activity at higher concentrations (200 nM versus 20 nM) is detectable, consistent with a defect in microtubule binding. At these concentrations the wild-type protein obliterates the microtubules before the perfusion into the microscopy chamber is even finished. Thus, the use of multivalent interactions between flexible disordered elements to engage the microtubule is a common feature of microtubule severing enzymes.

Discussion

Recent advances in cryo-EM have led to unprecedented progress in our understanding of the general architecture of AAA ATPases. The common emerging theme has been their asymmetric spiral assemblies and substrate engagement through their central pores. However, understanding their diverse biological functions that require them to remodel all three biological polymers, DNA, RNA and protein, requires understanding the differences between them, not only their overall similarities. Our structural and functional work shows that katanin, unlike other AAA ATPases characterized so far, uses a double-spiral system to coordinate the tubulin tail through the central pore and multivalent contacts through a low complexity disordered region outside the ordered AAA core to anchor the enzyme to the microtubule.

Our cryo-EM structures show that the double-spiral pore loop system is allosterically coupled to the ATP-binding site and oligomerization interfaces. We identify tubulin tail features critical for katanin recognition and activation, and demonstrate that the β-tail is necessary and sufficient for microtubule severing. The double spiral is formed by two conserved pore loops that coordinate the substrate through a mixture of electrostatic and aliphatic interactions. The two spirals coordinate alternating, successive residues in the extended substrate polypeptide. Pore loop 1 residues form the first spiral that binds i-th residues. Pore loop 2 residues together with a katanin specific arginine in pore loop 1 form the second spiral that binds (i+1)-th residues (Figure 3). A third solvent exposed pore loop acts as a rigid coupling element between the ATP binding site, pore loop 2 and oligomerization elements (Figure 4F). While in most other AAA ATPase structures only pore loop 1 has been reported to interact directly with substrate (de la Pena et al., 2018; Deville et al., 2017; Gates et al., 2017; Han et al., 2017; White et al., 2018), in katanin two pore loops coordinate alternating, successive substrate residues (Figures 3 and 7). An involvement of a second pore loop in substrate binding has been also found for spastin (Sandate et al., 2019) and YME1 (Puchades et al., 2017). However, YME1 uses a tyrosine in the second pore loop instead of the histidine in katanin. Furthermore, in katanin (i+1)-th residues are coordinated by sidechains contributed not only by pore loop 2 (His307), but also pore loop 1 (Arg267) from the adjacent protomer, ensuring seamless communication within the hexamer for substrate binding and translocation. This substrate binding strategy provides specificity for the electronegative tubulin tails and is different from that observed for other AAA ATPases characterized so far. This includes the microtubule-severing enzyme spastin (Sandate et al., 2019) and the closely related AAA ATPase VPS4 (Han et al., 2017) which disassembles ESCRTIII polymers. We speculate that this interconnected double-spiral system in katanin is able to support higher processivity and the generation of stronger forces to pull tubulin subunits out of microtubules. Thus, our structure coupled with functional assays identifies key elements for specific tubulin tail sequence recognition by katanin and reveals how they have diverged even in closely related AAA ATPases.

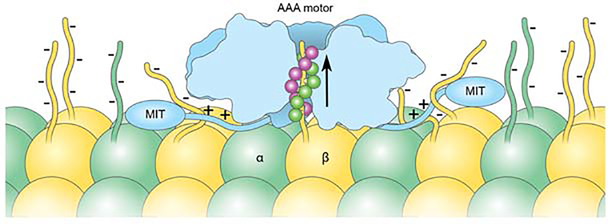

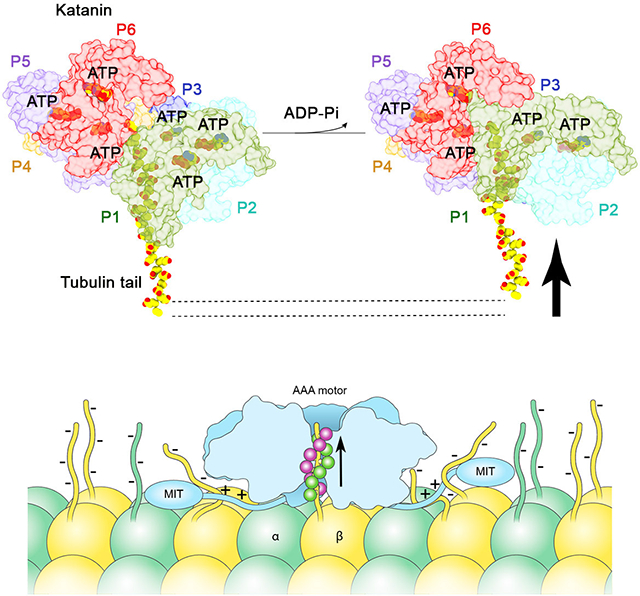

Figure 7. Model for katanin microtubule recognition and severing.

Schematic of microtubule recognition by katanin using multivalent interactions through the electropositive pore loop double spiral (green and magenta for spirals 1 and 2, respectively) and positively-charged residues in the flexible linker connecting the MIT and AAA domains.

Our functional work reveals that clusters of positively charged residues in the disordered linker connecting the AAA and MIT domains are required for katanin microtubule binding and severing. Thus, each protomer in the katanin hexamer has at least three contact points with the microtubule: through the AAA core which binds the tubulin tail in the central pore, the three-helix bundle MIT domain (Iwaya et al., 2010) as well as the flexible linker (Figure 7). The MIT domain binds microtubules with low affinity (Iwaya et al., 2010). It also forms a stable complex with the C-terminal domain of the p80 regulatory subunit (Rezabkova et al., 2017). High affinity microtubule binding requires the disordered linker (Eckert et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2017), consistent with our finding that positively-charged linker residues are critical for katanin severing. We note that the involvement of these linker regions in microtubule binding constrains the orientation of the katanin hexamer on the microtubule such that the face decorated with the fishhook is proximal to the microtubule surface, with the peptide threaded from its N to the C-terminus through the pore. The opposite orientation on the microtubule is less likely because the disordered region of the linker is not long enough to exit the fishhook at the top of the hexamer and span the length needed to make microtubule contacts through the positively charged clusters (Figure 7). Positively charged residues in the disordered linker of spastin are also important for severing, indicating that the multivalent engagement of the microtubule through disordered elements is a general strategy used by microtubule severing enzymes. However, spastin lacks the fishhook linker element important for severing in katanin. Interestingly, the closely related meiotic subfamily member VPS4 can dispense with its entire linker but three residues and still retain robust activity (Shestakova et al., 2013), indicating that it uses a different strategy to bind ESCRTIII polymers.

Our structures in two distinct conformations, spiral and ring, suggest a mechanism for tubulin extraction out of the microtubule. This involves the translocation of the tubulin tail through the central pore through the movement of a boundary protomer that cycles between engagement and disengagement of the tubulin substrate during the ATPase cycle. In the initial spiral state all six protomers are ATP-bound and bind the substrate through their pore loops. Upon ATP hydrolysis and product release we propose that the gate protomer P1 pulls on the substrate and then disengages and binds at the top of the spiral such that P2 can bind where P1 used to bind, initiating a ratchet-like movement of the substrate peptide through the pore. This mechanism in which five of the six subunits of the AAA ATPase motor, in the ATP or ADP-Pi state, directly bind the substrate while a boundary protomer in the apo or ADP state is dissociated from the substrate and makes non-canonical interfaces with the neighboring protomers, is analogous to that recently described for VPS4 (Han et al., 2017), HSP104 (Gates et al., 2017), YME1 (Puchades et al., 2017), NSF (White et al., 2018) and VAT (Ripstein et al., 2017). However, unlike VPS4, YME1 and VAT, but analogous to HSP104 (Gates et al., 2017) we also capture katanin in a pre-hydrolysis spiral conformation where all six protomers are evenly spaced and bind substrate. When enough of the tail is unfolded, lattice interactions are compromised, and tubulin dissociates from the microtubule. Alternatively, the translocating force exerted by P1 dislocates the entire dimer out of the lattice without extensive unfolding of the tubulin polypeptide. We favor a hybrid model with limited tubulin unfolding because denatured unfolded tubulin does not refold and would have to be cleared by the cell.

The importance of positively charged clusters in the disordered linker for severing raises the intriguing possibility that multiple tubulin subunits could be dislodged out of the microtubule during the power stroke: one tubulin subunit through the tail interactions in the pore and additional tubulins bound to the linker which is pulled away from the microtubule by the movement of the boundary protomer. Such a mechanism depends on the nature of the coupling between the linker and the AAA core. Alternatively, the interaction with the flexible linker could just stably anchor the hexamer on the microtubule while the AAA ring remodels with the ATPase cycle and repeatedly tugs on the tubulin tail until it successfully extracts the dimer out of the lattice. Since intrinsically disordered regions are found in many AAA ATPases linkers, it is possible that they are used more broadly for multivalent substrate engagement.

STAR METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIAL AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Antonina Roll-Mecak (Antonina@mail.nih.gov). All plasmids and cell lines used in this study are available upon request from the authors.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

All katanin constructs were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells. Unmodified tubulin was purified from tSA201 cells.

METHOD DETAILS

Protein expression and purification

The plasmid expressing maltose binding (MBP)-tagged C. elegans katanin p60 (MEI-1) was generated by Gateway cloning protocol, using the pDEST566 expression vector. Plasmids for the co-expression of untagged MEI-1 and MEI-2 (p80) with MBP N-terminal fusion protein, followed by a Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease cleavage site were a gift from Prof. F.J. McNally (McNally et al., 2014). Expression of MEI-1 or MEI-1/MEI-2 was carried out in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells cultures were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of ~ 1.0 and expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG at 16°C for fourteen hours. Harvested cells were resuspended in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, and lysed with a microfluidizer in the presence of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 31,000 x g for 40 min and loaded onto amylose resin (New England Biolabs), equilibrated in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DTT. MEI-1 or MEI-1/MEI-2 were released from the resin by one-hour cleavage with TEV protease at 50:1 mass ratio. Proteins were further purified by ion exchange chromatography, using a HiTrapQ column for MEI-1 and HiTrapQ (GE Healthcare) and MonoS Sepharose (GE Healthcare) for MEI-1 / MEI-2. Proteins were concentrated to 5 mg/ml and exchanged into buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP, 15 % glycerol and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage at −80°C. MEI-1 was further purified by size exclusion chromatography on a Superose 6 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare). For enzymatic assays, single use aliquots of proteins at 100 μM concentration in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP, 15 % glycerol were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. All mutants were generated using Quickchange and purified the same as the wild-type.

Drosophila melanogaster spastin (Roll-Mecak and Vale, 2008) (sequence ID NP_001303437.1) was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21DE3 as a N-terminal glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion and purified by affinity chromatography as described previously (Ziolkowska and Roll-Mecak, 2013). Single-use aliquots were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. All point mutants were generated using Quickchange mutagenesis and purified as the wild-type protein.

Peptide synthesis

C-terminal tubulin peptides used in ATPase assays (VDSVEGEGEEEGEEY, DATAEEEEDFGEEAEEEA,DATAEEEGEFEEEAEEEVA,VGSEEEEEEEEEE,VGSEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE,DATAEEEGEFAAAAAAAVA,DATAEEEGEFDDDADDDVA,DATAEEEGEFQQQAQQQVA) were synthetized and RP-HPLC purified to obtain >95% purity by Biosynthesis with the exception of the DATAEEEGEFEEEAEEEEA peptide synthesized by David King (University of California, Berkeley). 5 mM Stock solutions of peptides were made in water and adjusted to pH 7.5 with potassium hydroxide. Serial 10-fold dilutions of peptides were made in water to assay peptides at the concentration range of 2 to 600 μM.

Cryo-EM specimen preparation and data acquisition

C. elegans katanin p60 (MEI-1) with a Walker B mutation (E293Q) at ~1mg/ml (18 μM) in 20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 2 mM TCEP was mixed on ice with excess of poly(E) molecular weight 3 kDa (30 μM) (Alamanda Polymers, CAS#26247–79-0) just before cryo-EM grid preparation. 5 μl of sample were applied to a glow-discharged C-flat holey carbon on gold grids with 2 μm hole, 1 μm space (CF-2/1–4Au). The grids were blotted for 5 seconds at 90% humidity and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen using Leica EM GP (Leica Microsystems, Germany). A dataset of 5,911 movie stacks was collected on a Titan Krios microscope (FEI) operated at 300 kV, equipped with a K2 Summit direct electron detector camera, operated in super-resolution mode, energy filter slid width of 20 eV, C2 aperture 70 μm and 100 μm objective aperture. The movies were recorded at a nominal magnification of 130,000X, corresponding to a physical pixel size of 1.08 Å/pixel at a defocus range from −1.2 μm to −2.5 μm. The dose rate was 8.5 e−/pix/s. 50-frame movie stacks were recorded for 10 s with a cumulative electron dose of 73 e−/Å2 (Table S1). Data collection was automated with Leginon (Suloway et al., 2005).

Cryo-EM data processing

Image processing was performed in Relion 3.0 (Nakane et al., 2018; Scheres, 2012) and the Scipion pipelines (de la Rosa-Trevin et al., 2016). All image frames (73 e−/Å2 total dose) were aligned, dose weighted and summed using MotionCor2 (Zheng et al., 2017), defocus parameters were estimated using Gctf (Zhang, 2016). Power spectrum of each micrograph was analyzed and images showing strong and isotropic Thon rings were selected. 1,876,223 particles were automatically picked using Gautomatch (url: http://www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/kzhang/) (Figure S2). Particles were extracted into 224 pixels box size, binned 4x (pixel size 4.32 Å/pix) and then subjected to 4 rounds of reference-free 2D classification. 2D class averages showed fine molecular features, suggestive of katanin structural order, and presented the complex in different orientations (Figure S3A). 1,221,369 particles were selected for analyses in 3D. The previous 4.4 Å reconstruction of katanin p60 (Zehr et al., 2017) in the spiral conformation was low-pass filtered to 35 Å and used as an initial reference map for 3D classification of images into 10 classes. The 3D classification (pixel size 4.32 Å/pix) followed by 3D refinement (pixel size 2.16 Å/pix) of each class revealed the AAA ATPase ring in the two conformations: the spiral conformation (26% of the dataset) and the ring conformation (22% of the dataset). These two conformations of the katanin AAA ATPase hexamer have been described before (Zehr et al., 2017). Particles in classes 3 and 9 in the ring conformation (111,285 and 163,573 particles, respectively) or classes 6 and 10 in the spiral conformation (160,046 and 163,170 particles, respectively) were combined and further classified in 3D without angular or translational searches (tau fudge=20–30, k=3), followed by 3D refinement of the classes with the highest nominal FSC-reported resolution (cut-off 0.143) with a custom mask enclosing all protomers and extending 3 pixels in all directions from the AAA ATPase hexameric core to mask out flexible protein parts around the core (Zehr et al., 2017), followed by the per-particle CTF refinement with fitting per-micrograph astigmatism (Figure S2). The final maps for the ring conformation at 3.6 Å contain 108,700 particles and for the spiral conformation at 3.5 Å resolution contains 40,102 particles. Classes 3 and 9 for the ring conformation showed a variable definition of protomer P1, with class 3 having a better definition to it. Therefore, class 3 was refined in 3D separately from class 9 and was resolved to 4.2 Å. The final map contains 111,285 particles. The reconstructions were sharpened using phenix.autosharpen (Terwilliger et al., 2018) applying negative B-factors of −70 Å2, −140 Å2 and −200 Å2 for the spiral and the ring structures, respectively. Data collection statistics and image-processing summary can be found in Table S1.

To analyze the molecular motions of P1 katanin ring conformation, we performed multi-body refinement, using particles that contributed to 4.2 Å map with assigning NBD of P1 as one body and the rest of the AAA ATPase ring as the second body (Figure S2) (Nakane et al., 2018). Multi-body refinement did not improve the resolution or the quality of either body. Histograms of the amplitudes along all eigenvectors are monomodal and suggestive that the NBD P1 exhibits a continuous motion with respect to the rest of the hexameric ring. The local resolution was estimated using program MonoRes (Vilas et al., 2018).

Model building and refinement

The model for the katanin hexamer in the spiral conformation without substrate (ID: 5wc0) (Zehr et al., 2017) was used as a starting model for the katanin:peptide complex in the spiral conformation. The nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and the helix-bundle domain (HBD) of each protomer were rigid-body fitted into the cryo-EM map in the spiral conformation using Phenix (Afonine et al., 2018). Additional adjustments to the backbone and side chains were performed manually in COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004), residue by residue. Nucleotide densities were clearly visible in protomers one through six (P1-P6). The superior quality of the map in this study compared to that of the apo katanin (EMD-8794) (Zehr et al., 2017) allowed us to build de novo the fishhook element residues 156–172 and pore loop 2. Good quality of the map also permitted de-novo modelling of the polyglutamate substrate peptide. 14 glutamates were clearly defined and modelled. Some of the side chains of the substrate were not resolved, which is typical of the negatively-charged side-chains being sensitive to radiation damage (Bartesaghi et al., 2014; Glaeser, 1971). The model was subjected to real space refinement for 3 macro cycles with one round of annealing in PHENIX (Afonine et al., 2018), followed by mannual adjustments in Coot and final real space refinement with 1 macro cycle in Phenix. The final atomic model has an overall correlation to the map 0.867 calculated in UCSF Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004). Model statistics for both conformations are listed in the Table S1.

The atomic model for the spiral conformation was used as a starting model to build an atomic model for the ring conformation. The reconstruction of katanin in the ring conformation at 3.6 Å (with poorly resolved protomer P1) was used to rigid-body fit the NBD and HBD domains of P2 through P6. An initial model missing the polyglutamate peptide, pore loop 1 and 2 and protomer P1 was subjected to three rounds of refinement followed by an additional round with the complete model. The final atomic model has an overall correlation to the map 0.836 calculated in UCSF Chimera. Model statistics for both conformations are listed in the Table S1.

The atomic model derived from the 3.6 Å cryo-EM map was used as an initial model for fitting in the reconstruction of katanin in the ring conformation at 4.2 Å (with better resolved protomer P1). NBD and HBD domains of P1 through P6 were rigidly fit in the map. Three rounds of global minimization with one round of simulated annealing were carried on in Phenix, omitting from refinement pore loop 1 residues of protomer P1 followed by one round of minimization including all residues and using the spiral conformation model as a reference. The final atomic model has an overall correlation to the map 0.881 calculated in UCSF Chimera. Model statistics are listed in Table S1. Figures were prepared with UCSF Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004) and Pymol (Schrodinger, 2015).

Modeling of β-tubulin tail peptides bound to katanin

β-tubulin tail peptide substrates were modelled using the final atomic model of katanin in the spiral conformation. Glutamate residues in the polyglutamate peptide were mutated to residues of the βIVb wild-type or mutant substrates or βI tails and manually adjusted in COOT. The resulting models were subjected to one macro-cycle of refinement in real space using Phenix. Model statistics for katanin-βIVb tail complex (Figure S8B): MolProbity score 1.70; clash score 3.67; Ramachandran outliers 0.05, allowed 9.62, favored 90.32; rotamer outliers 0.90. Model statistics for the katanin-βI tail complex (Figure S8C): MolProbity score 1.70; clash score 3.74; Ramachandran outliers 0.05, allowed 9.51, favored 90.43; rotamer outliers 0.90. We also modeled the βIVb-tail in a second register where the Phe in the β-tail is recognized by residues in pore loop 2 (Figure S8D) as opposed to pore loop 1 (Figure S8B). The peptide also fits well in this register with similar model statistics (MolProbity score 1.64; clash score 3.26; Ramachandran outliers 0.05, allowed 8.96, favored 90.98; rotamer outliers 0.83), indicating that the binding is not very sensitive to register.

ATPase assays

Steady-state ATP hydrolysis was measured using the EnzCheck Phosphate Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Initial rates were calculated from the linear portion of the reaction curve. ATPase rates were corrected by subtraction of the measured release of phosphate in the absence of ATP. Basal ATPase assays were performed in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DTT at 1 μM MEI-1/MEI-2. Reactions were carried out at room temperature and started by addition of 1 mM ATP.

ATPase assays in the presence of tubulin tail peptides or poly-glutamate (polyE) with different mass distributions were performed at room temperature in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 50 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DTT at 1 μM MEI-1/MEI-2. Stock solutions of poly-E polymers (100 mM – poly-E 3.0 kDa, Alamanda Polymers, catalog number 26247–79-0) were made in water and adjusted to pH 7.5 with potassium hydroxide. ATPase activities were assayed in the range of poly-E concentrations 0–600 μM after addition of 2 mM ATP. Microtubule stimulated ATPase activity assays were performed at 100 nM MEI-1/MEI-2 concentration with taxol-stabilized brain microtubules at 2 and 4 μM concentration in BRB80 buffer (80 mM PIPES pH 6.9, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA) supplemented with 20 μM taxol, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DTT. Reactions were carried out at room temperature and started by addition of 1 mM ATP.

Generation of recombinant tailless and subtilisin treated microtubule substrates

Engineered tubulin constructs were expressed and purified as described previously (Valenstein and Roll-Mecak, 2016; Vemu et al., 2016). Since a β-tubulin tailless construct is not soluble, we expressed an engineered construct with a Prescission protease site introduced at the end of helix α12 in tubulin as described previously (Valenstein and Roll-Mecak, 2016). The β-tail was subsequently removed through protease digestion after the engineered tubulin construct was purified and assembled into microtubules. Analysis by western blot using a rabbit anti-FLAG antibody (GenScript # A00170) revealed that ~15% of the β-tubulin tails were not cleaved.

Unmodified tubulin was obtained as previously described (Vemu et al., 2014; Widlund et al., 2012). Taxol-stabilized unmodified human microtubules were prepared as described previously (Valenstein and Roll-Mecak, 2016). Microtubules missing β-tubulin tails to various extents were obtained by digesting microtubules at 3 mg/ml with subtilisin at a 1:200 subtilisin:tubulin mass ratio for 60 min to partially remove β-tubulin tail and 90 min to completely remove the tail. Reactions were performed at 37°C and quenched with 5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Microtubules were recovered through a glycerol cushion. Digests were subjected to mass spectrometric analysis as previously described (Valenstein and Roll-Mecak, 2016) and are shown in Figure S1A.

Microscopy based microtubule severing and binding assays

Flow chambers were constructed from silanized glass as described previously (Ziolkowska and Roll-Mecak, 2013). Microtubule severing assays were performed as previously described (Ziolkowska and Roll-Mecak, 2013). For severing assays with katanin double-cycled, GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules (Gell, 2010) containing 79% unlabeled porcine brain tubulin, 20% Alexa647-labeled tubulin (PurSolutions) or HiLyte647-labeled tubulin (Cytoskeleton) and 1% biotinylated tubulin (Cytoskeleton) were used. For severing assays with spastin double-cycled, GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules (Gell, 2010) containing 84% unlabeled porcine brain tubulin (Cytoskeleton), 5% HiLyte647-labeled tubulin (Cytoskeleton) and 1% biotinylated tubulin (Cytoskeleton) were used. Microtubules were immobilized in the chamber using NeutrAvidin (Life Technologies). Microtubule severing buffer (47 mM PIPES pH 6.8, 3.3 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 50 mM KCl, 2.2 mM MgCl2, 1.3 mg/ml casein, 0.6 mM EGTA, 2.5% glycerol, 9.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.8 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 1% Pluronic F127, 20 mM glucose, glucose oxidase and catalase) was then perfused into the chamber. Severing reactions were started by perfusing 20 nM MEI-1/MEI-2 or Drosophila melanogaster spastin in severing buffer into the chamber while continuously acquiring data. The 20 nM enzyme concentration was chosen as it gave a good dynamic range for assaying various mutants. Images were acquired at 1 frame per second or every 2 seconds for the less active mutants with 100 ms exposure on an inverted total internal reflection fluorescence microscope (Nikon Ti-E with TIRF attachment). The excitation light was provided by a 640 nm laser. Microtubule severing progress was monitored by counting the number of observed microtubule severing sites after perfusion of katanin. Microtubule severing rates were determined as the time required to observe one severing event per 10 μm of microtubule (Valenstein and Roll-Mecak, 2016).

For the experiments with engineered recombinant microtubules, recombinant α1A/βIII, αΔtail/βIII or α1A/βΔtail tubulin was polymerized together with 1.5% biotinylated brain tubulin and stabilized with taxol. Microscopy chambers were prepared as described above and severing assays were performed with 20 nM MEI-1/MEI-2 in microtubule severing buffer supplemented with 8.7 μM taxol. Images were acquired by differential interference contrast microscopy at 1 frame per second. Microtubule severing progress was monitored by counting the number of observed microtubule severing events. Severing rate was obtained from the slope of the curve of number of severing events as a function of time (Valenstein and Roll-Mecak, 2016). Microtubule severing events were extremely sparse in the α1A/βΔtail condition. Binding to recombinant microtubules was measured by perfusing 4 nM Atto488-labeled MEI-1/MEI-2 in microtubule severing buffer into the chamber. Images were acquired with a TIRF microscope continuously at 100 ms exposure. The excitation light was provided by a 488 nm laser. Microtubules were unlabeled and visualized by differential interference contrast microscopy. Binding was quantified as the background subtracted average fluorescence of microtubules on a sum of all images between 25 and 60 sec after perfusion.

Katanin was labeled with Atto488 fluorophore using Sortase (Antos et al., 2017). Specifically, a small peptide tag (GGGGSLPETGG) was added to the C-terminus of katanin p80 (MEI-2) for the Sortase A-mediated reaction with the fluorescently labeled peptide H2N-GGGGSSC(Atto488)-COOH. The labeled protein was purified on a Superose 6 10/300 GL size exclusion column (GE Healthcare) to remove the unreacted peptide. The labeling efficiency was 64% and the labeled enzyme had activity comparable to that of the unlabeled wild-type protein.

Assay for katanin-mediated microtubule nanodamage

Alexa647- or HiLyte647-labeled microtubules were prepared and immobilized in flow chambers as described above. In order to measure the extent of microtubule nanodamage, which is too small to visualize directly by light-microscopy because of resolution limitations (Vemu et al., 2018), katanin MEI-1/MEI-2 in microtubule severing buffer was perfused into the chamber with microtubules and incubated for 30–120 sec. Then, the enzyme solution was replaced by perfusing 1 μM HiLyte488-labeled tubulin (Cytoskeleton) in BRB80 supplemented with 1 mM ADP, 0.5 mM GTP, 1% Pluronic F127, 2.5 mg/ml casein. Microtubules were incubated with the HiLyte488-tubulin for 5 min. Soluble tubulin was washed out with 45μl of BRB80 buffer supplemented with 1.5 mg/ml casein, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1% Pluronic F127 and oxygen scavengers. Images in the microtubule and tubulin channel were acquired with a TIRF microscope as described in (Vemu et al., 2018). To quantify the extent of microtubule nanodamage, the 488 and 640 channels were aligned using a Nanogrid (Miraloma Tech) and the GridAligner plugin in Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012). Microtubules were selected with a 7-px-wide line. Mean intensity in 488 channel was measured, background-corrected and normalized for average intensity along microtubules treated with wild-type katanin.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical data analysis was performed in Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012) and plots generated via GraphPad Prism. Statistical details of experiments and tests used are indicated in the METHOD DETAIL section and figure legends. The two-tailed t-test for normally distributed data and Mann-Whitney test for non-normally distributed data were used for statistical analysis as indicated in figure legends. Data are shown as mean and S.E.M. or S.D. or Tukey plots. n values for each experiment are indicated in the figure legends and the METHOD DETAIL section.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

Electron microscopy maps and atomic models have been deposited at the Electron Microscopy Data Bank and Protein Data Bank under accession numbers EMDB: 20761 and PDB: 6UGD for the spiral conformation; EMDB: 20763 and PDB: 6UGF for the ring conformation, resolved P1; EMDB: 20762 and PDB: 6UGE for the ring conformation.

Supplementary Material

Data S1. Coordinate file for the katanin: βIV C-terminal tail peptide model (related to Figure 3 and S8).

Video S1. Movie illustrating the structure of katanin bound to substrate. Related to Figures 2 and 3. Katanin subunits colored as in Figure 2 with the substrate peptide colored in yellow and shown as spheres colored by heteroatom.

Highlights.

Katanin grips the tubulin tail through a double spiral in its central pore

Charge density in the β-tubulin tail is critical for katanin activation

ATP hydrolysis and release uncouples the tubulin tail from the pore loops

Katanin uses multivalent interactions to disrupt the microtubule lattice

Acknowledgements

We thank Huaibin Wang at the Multi-Institute cryo-EM Facility at the National Institute of Health (NIH) for assistance with data collection, Duck-Yeon Lee (Biochemistry Core of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute) for help with mass spectrometry and Ethan Tyler (NIH Medical Arts) for help with illustrations. Images processing was performed on the Biowulf cluster maintained by the High Performing Computation group at the National Institutes of Health. We thank Frank McNally (University of California, Davis) for the gift of the wild-type katanin plasmid. A.R.M is supported by the intramural programs of the National Institute of Neurological Disorder and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Afonine PV, Poon BK, Read RJ, Sobolev OV, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, and Adams PD (2018). Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 531–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad FJ, Yu W, McNally FJ, and Baas PW (1999). An essential role for katanin in severing microtubules in the neuron. The Journal of cell biology 145, 305–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos LA, and Schlieper D (2005). Microtubules and maps. Adv Protein Chem 71, 257–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antos JM, Ingram J, Fang T, Pishesha N, Truttmann MC, and Ploegh HL (2017). Site-Specific Protein Labeling via Sortase-Mediated Transpeptidation. Curr Protoc Protein Sci 89, 15 13 11–15 13 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey ME, Sackett DL, and Ross JL (2015). Katanin Severing and Binding Microtubules Are Inhibited by Tubulin Carboxy Tails. Biophysical journal 109, 2546–2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartesaghi A, Matthies D, Banerjee S, Merk A, and Subramaniam S (2014). Structure of beta-galactosidase at 3.2-A resolution obtained by cryo-electron microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 11709–11714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholdi D, Stray-Pedersen A, Azzarello-Burri S, Kibaek M, Kirchhoff M, Oneda B, Rodningen O, Schmitt-Mechelke T, Rauch A, and Kjaergaard S (2014). A newly recognized 13q12.3 microdeletion syndrome characterized by intellectual disability, microcephaly, and eczema/atopic dermatitis encompassing the HMGB1 and KATNAL1 genes. Am J Med Genet A 164A, 1277–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova M, Crobu L, Blaineau C, Bourgeois N, Bastien P, and Pages M (2009). Microtubule-severing proteins are involved in flagellar length control and mitosis in Trypanosomatids. Molecular microbiology 71, 1353–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Maguire S, and Mains PE (1994). mei-1, a gene required for meiotic spindle formation in Caenorhabditis elegans, is a member of a family of ATPases. Genetics 136, 533–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Pena AH, Goodall EA, Gates SN, Lander GC, and Martin A (2018). Substrate-engaged 26S proteasome structures reveal mechanisms for ATP-hydrolysis-driven translocation. Science 362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Rosa-Trevin JM, Quintana A, Del Cano L, Zaldivar A, Foche I, Gutierrez J, Gomez-Blanco J, Burguet-Castell J, Cuenca-Alba J, Abrishami V, et al. (2016). Scipion: A software framework toward integration, reproducibility and validation in 3D electron microscopy. J Struct Biol 195, 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]