Abstract

The scaling of Option B+ services, whereby all pregnant women who test HIV positive are started on lifelong antiretroviral therapy upon diagnosis regardless of CD4 T-cell count, is ongoing in many high HIV burden, low-resource countries. We developed and evaluated a tablet-based mobile learning (mLearning) training approach to build Option B+ competencies in frontline nurses in central Mozambique. Its acceptability and impact on clinical skills were assessed in maternal child health nurses and managers at 20 intervention and 10 control clinics. Results show that skill and knowledge of nurses at intervention clinics improved threefold compared with control clinics (p = .04), nurse managers at intervention clinics demonstrated a 9- to 10-fold improvement, and nurses reported strong acceptance of this approach. “mLearning” is one viable modality to enhance nurses’ clinical competencies in areas with limited health workforce and training budgets. This study’s findings may guide future scaling and investments in commercially viable mLearning solutions.

Keywords: central Mozambique, mLearning, mobile health education, on-the-job training, Option B+, PMTCT

Mother-to-child transmission of HIV remains a major public health challenge despite the availability of effective antiretroviral therapy. In 2017, approximately 160,000 newborns were infected globally, and most transmissions occurred among populations in sub-Saharan Africa (UNICEF, 2018). The World Health Organization’s Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT) of HIV Guidelines were updated in 2016 to recommend the Option B+ strategy, whereby all pregnant and postpartum women who test HIV positive are placed on lifelong combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) for life regardless of CD4+ T-cell count or clinical stage (Centers for Disease Prevention and Control [CDC], 2013; World Health Organization [WHO], 2016). Recommendations for countries scaling Option B+ initially prioritized country-level readiness at the expense of guidance and concrete tools to build essential frontline clinical competencies among nurses, who were newly responsible for cART care and management of perinatal women and their newborns (WHO, 2016). In many high HIV burden countries, health care workforce training modalities to address the influx of newly eligible patients and rapidly evolving treatment recommendations are inadequate for effective Option B+ implementation.

Option B+ was adopted as a policy in Mozambique in 2013. Like many other high HIV burden countries, maternal and child health (MCH) nurses in Mozambique were tasked with scaling Option B+ in primary care settings and managing cART throughout the perinatal and postpartum periods (Habte, Dussault, & Dovlo, 2004; Kober & Van Damme, 2014; Narasimhan et al., 2004). Nurses tasked with implementing Option B+ were predominantly trained using a physician-focused curriculum without substantial modifications (Ferrinho, Sidat, Goma, & Dussault, 2012). There were no additional financial resources provided through the Ministry of Health (MOH) to conduct the training and, in some cases, nongovernmental organizations provided support. This resulted in a variation of training duration, proportion of nurses covered in each facility (or region), training content, and on-the-job support across the country. This variability threatened service quality because it is essential that training modalities be acceptable, consistent, and scalable to achieve improved maternal health and elimination of HIV transmission to children (World Bank, 2016).

Mobile-learning (mLearning), defined as “learning across multiple contexts, through social and content interactions, using personal electronic devices” (Crompton, 2013, p. 7), is an educational modality that has shown promise as an effective, adjunctive strategy to educate and train health workers in resource-constrained settings where on-the-job training is often sporadically carried out (O’Donovan et al., 2018). “mLearning” is a newer application of mobile health strategies, which have primarily focused on using mobile technologies to provide cost-effective solutions for provider diagnosis and treatment support, supply chain management, medication adherence regimens, data collection, and emergency management (WHO, 2011). In settings with limited human resources for health, mLearning approaches can reinforce service quality, particularly as new guidelines such as Option B+ are updated and implemented. A hybrid approach incorporating clinical images and video assessment to computerized learning has shown potential to improve clinical reasoning, diagnosis, and clinical decision-making (Dunleavy et al., 2019; O’Donovan et al., 2018).

Remote, computerized training approaches can be integrated into routine supervision and tailored to build on nurses’ baseline knowledge, which limits provider time outside of health facilities and results in training that maximizes available resources and minimizes disruption to PMTCT services (Fernandez-Lao et al., 2016). Mobile data collection systems, such as Open Data Kit (ODK; Brunette et al., 2017) and RedCAP (Harris et al., 2009), can be built into tablet-based modules to collect and upload real-time information from competency assessments to a central server. This approach provides data to subnational and local nurse managers to prioritize challenging topics and target facilities with skill gaps for in-person supervision and other quality improvement activities—promoting sustainable improvements in frontline service delivery. The purpose of this study was to develop and evaluate a tablet-based training approach, coupled with supervision, as an acceptable and viable strategy to strengthen on-the-job clinical training for nurses providing Option B+ in low-resource settings.

Methods

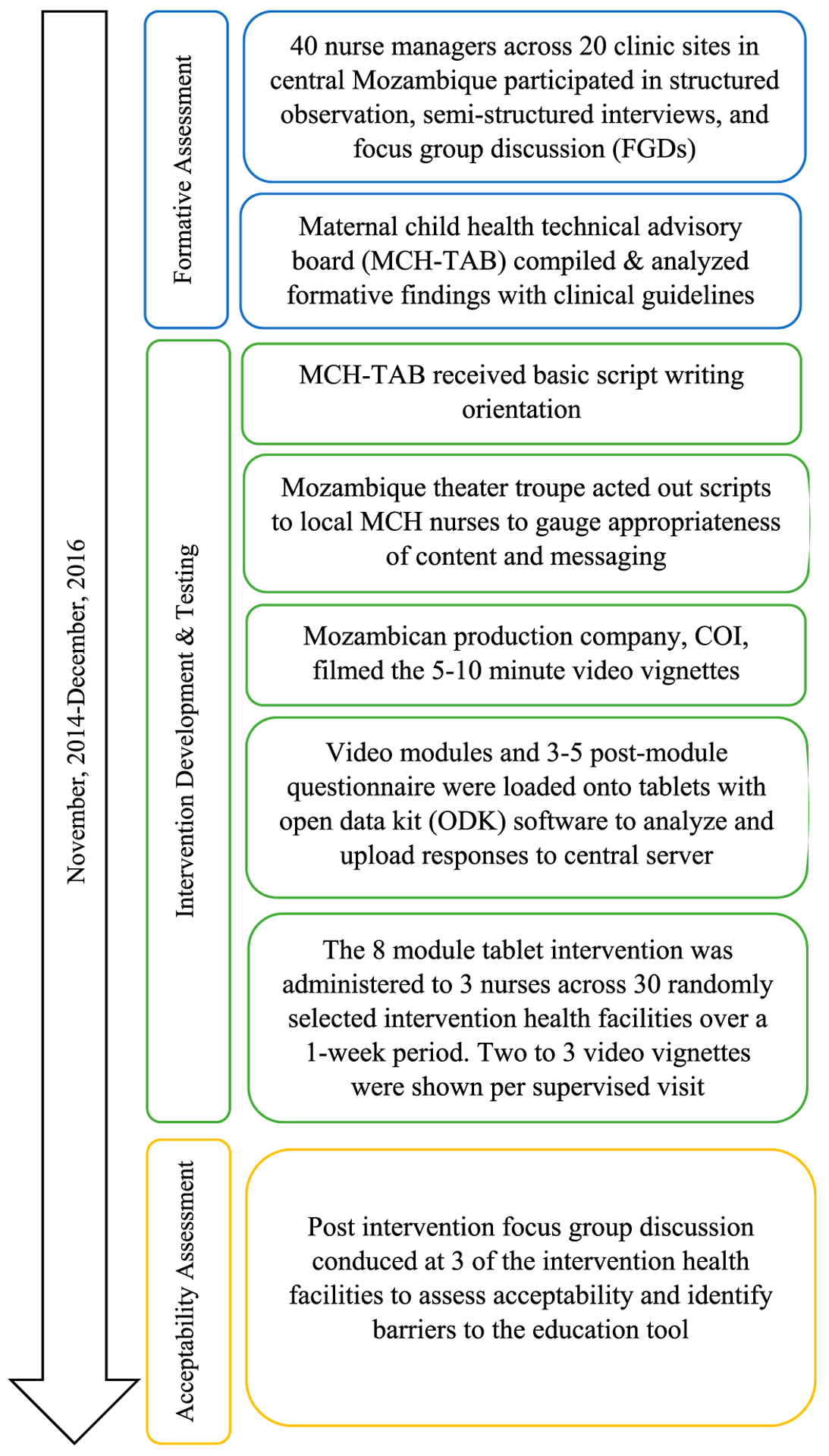

To address our study objectives, we carried out a prospective, mixed-method study between November 2014 and December 2016. The study included: (a) a formative assessment to design the content and organization of the training modules and overall implementation strategy, (b) an intervention development and testing with Option B+ providers and other stakeholders, and (c) acceptability testing with nurses and facility managers (Figure 1). Sofala and Manica provinces of central Mozambique were selected as the study settings to leverage the long-standing collaboration with the study investigators in HIV and health systems research. The qualitative aspects of this study were conducted in the native Portuguese language and led by native-speaking staff and a fluent investigator with substantial experience in country. MCH managers and MCH nurses were eligible to participate regardless of sex or race/ethnicity. All study participants were recruited individually and confidentially at the end of the workday at the facility to minimize any risks to confidentiality.

Figure 1.

Summary of intervention development and testing activities.

Formative Assessment

Study participants and design.

A total of 30 clinics were purposively selected to represent a range of size (high, medium, and low antenatal care and institutional birth utilization), staffing patterns, and geographic location type (urban and rural) across districts in the central Mozambican provinces of Sofala and Manica. Sites were specifically selected to exploit the heterogeneity of settings and service flow in the total sample to explore how acceptable the intervention would be across a range of facilities, to identify shared patterns across implementation sites and to maximize generalizability of the findings (Palinkas et al., 2015). Within the sample, the 30 clinics were stratified by size and then randomly allocated in 2:1 proportion to the intervention or control group.

Half-day structured observation and semi-structured interviews were carried out with 40 health care workers (nurses and nurse managers) across 20 clinics—10 within and 10 outside of Beira city (the capital of Sofala province). Vignette approach was used to assess baseline knowledge of MOH protocols and skills related to the clinical management of HIV across the perinatal period. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were also held in each study facility to identify factors such as practices, attitudes, and beliefs related to Option B+ care provision. A 5-point Likert scale was used to measure nurse self-perception of their own competency needs, abilities, and confidence to manage HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women under current protocols or self-efficacy in providing Option B+ services. These questions were developed based on clinical management standards from Mozambican Ministry of Health guidelines and the WHO (Mozambique MOH, 2014; Interagency Task Team [IATT], 2014).

Data collection and analysis.

In-depth interviews (IDIs) and FGDs were recorded and subsequently transcribed. Notes from structured observations and FGDs were taken on summary forms designed by the study researchers.

An MCH technical advisory board (MCH-TAB) was formed during the study to review, independently analyze, and provide feedback on all formative research findings. The MCH-TAB comprised study staff, researchers from Mozambican National Institute of Health’s Beira Operational Research Center (CIOB), and MCH managers at the provincial, district, and city levels of the Ministry of Health. Qualitative data were analyzed using a constant comparison process and iterative approach to identify themes that arose from FGDs and IDIs with nurses and nurse managers and compared with subsequent interviews rather than any preexisting theories (Charmaz, 2006). ATLAS.ti was used to manage, code, and analyze qualitative data (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2017).

Intervention Development and Testing

The MCH-TAB members matched findings with clinical guidelines to ensure that the most salient components of successful nurse-initiated HIV care were included in the development of a modular tablet-based training intervention. Content for the modules were developed based on MCH-TAB input, and collated from several, established core competency recommendations, including those from the WHO, UNICEF, the Malawi MOH’s Clinical Guidelines for Management of HIV in Children and Adults, and the Mozambican MOH’s PMTCT protocols (IATT, 2014; Malawai MOH, 2014; República de Moçambique Ministério da Saúde Direcção Nacional de Assistência Médica, 2014).

The MCH-TAB received an orientation in script writing from the study manager with input from both the PI and a professional screenwriter who provided ad hoc support to the study, before developing each video vignette module. Vignette script drafts were shared and reviewed by the national PMTCT working group; comments and recommended improvements were incorporated. After adaptation, but before filming, a Mozambican theater group acted out the scripts for a group of local MCH nurses to gauge appropriateness of content and messaging. A Mozambican film production company was recruited to film a total of eight, 5- to 10-minute video vignettes.

Study participants and design.

A controlled before and after study design was used to assess the impact of the intervention on nurse competency in the provision of Option B+ care. The eight-module tablet intervention was administered to nurses across the 20 intervention health facilities over a 1-week period, with two to three video vignettes shown per daily supervision visit by a team composed of study team members and district nurse managers. Each video was followed by three to five questions to assess nurse knowledge and skills pertaining to Option B+ care. Questions were developed based on skill gaps identified in the formative research phase and required to meet the standards of care from the Mozambican MOH guidelines. Postmodule questions were pulled randomly from a bank and answers were not released until the end of the study. Subsequently, ODK software was programmed onto tablets to collect knowledge and skill assessment data, and results were uploaded onto a central server to facilitate manager identification of training gaps across facilities.

Data collection.

Nurse participants were surveyed on their previous Option B+ training, nurse training, and exposure to electronics (tablet, computer, and mobile phone). Nurse competency in the module topics areas was assessed at baseline and after the final training sessions to gauge acquisition of these competencies. Nurse managers were reassessed at 1- and 3-month intervals.

Analysis.

A priori power calculations indicated that 60 participants in the intervention and 30 in the control group would provide >95% power to detect a 20% increase in overall score from the baseline to postintervention competency assessment (compared with 5% among controls) assuming an alpha of 0.05 and a SD of 0.015.

Pretest and posttest changes in module mean scores were compared between nurses who received the intervention and control nurses using paired t-tests. Paired t-tests were also used to compare the differences between nurse managers’ mean preintervention competency scores and the three postintervention time points. Cohen’s d was calculated to approximate within-subject effect sizes (Neath, 2018).

Acceptability Testing

FGDs with nurses and nurse managers from each of three intervention clinics were carried out by study staff. Three nurses (one manager and two frontline nurses) per facility were randomly selected to participate in a group. The total sample of nurses was randomly subdivided into three groups of equal size. Each small group was given 15 minutes to discuss and prepare a presentation that addressed acceptability of the content, barriers to using the educational tool, and the components of the intervention they thought could be feasibly implemented in the future. These questions were derived from the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989). The small FDG groups prepared short notes that were displayed on a wall for the large group discussion.

FGDs were recorded, transcribed, and independently analyzed using the constant comparison process mentioned above, focusing on acceptability of the intervention content and delivery strategy. All data collection was conducted in Portuguese.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of the University of Washington, by the Bioethics Committee for Health (CNBS), and by the MOH of Mozambique. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. On completion of this study, nurses with specific learning gaps received timely support from nursing supervisors and study team members.

Results

Characteristics of Participants

A total of 82 nurses were recruited, 62 in the intervention group and 20 in the control group. Overall, 57% of participants staffed rural clinics. Few participants owned a computer or tablet, although many owned a smartphone. Sixty-five percent of nurses in the control group had mid-level (3 years) training compared with 57% in the intervention group. The remaining nurses reported receiving basic (2 years) or elementary (1 year) level nursing education. Twenty percent of the control group and 27% of the intervention group nurses reported prior Option B+ training (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Nurse Participants (N = 82)

| Category | Control Participants (n = 20) | Intervention Participants (n = 62) |

|---|---|---|

| Location | ||

| Rural | 9 (45.0%) | 38 (61.3%) |

| Urban | 11 (55.0%) | 24 (38.7%) |

| Personal electronic ownership | ||

| Computer | 6 (30.0%) | 16(27.6%) |

| Tablet | 4 (20.0%) | 16(27.6%) |

| Smartphone | 13(65.0%) | 40 (72.3%) |

| Training | ||

| Mid-level | 13(65.0%) | 35 (56.5%) |

| Basic/elementary level | 7 (35.0%) | 27 (43.6%) |

| Prior Option B+ training | 4 (20.0%) | 17(27.4%) |

Formative Assessment and Intervention Development

The intervention comprised eight video vignette modules representing clinical cases related to a topic that was prioritized by nurses in the formative assessment, related to a skill or practice domain, and was essential to Option B+ delivery guidelines. The core topics were identified during the script writing retreat, whereby the MCH-TAB members came together to compile their analyses. The topics were crafted into vignettes that were filmed using common characters and locations to facilitate understanding and retention. The eight core clinical competency domains for nurses managing cART in HIV-infected pregnant women were selected, including group HIV counseling for Option B+, individual counseling and HIV testing, partner testing, initiation of cART and initial treatment side effects, care 7 and 30 days after starting cART, family planning, clinical analyses, and monitoring and evaluation of Option B+ services (Table 2).

Table 2.

Option B+ Vignette Module Topics

| Module Number | Topic Title |

|---|---|

| 1 | Group counseling for Option B+ |

| 2 | Individual counseling and HIV testing |

| 3 | Partner testing, starting ART: initial side effects |

| 4 | Seven days after starting ART: treatment confidante, continued side effects |

| 5 | Thirty days after starting ART: community stigma, mother support groups |

| 6 | Family planning and postpartum care |

| 7 | Clinical analysis |

| 8 | Monitoring forms for Option B+ |

Impact and Acceptability Findings

Baseline Option B+ knowledge scores in the control and intervention groups were 82.8 and 83.1%, respectively. After the mLearning activity, the intervention group’s change score increased by 4.7%, a threefold higher and statistically significant improvement when compared with the 1.6% change reported in the control group (p = .04; Table 3).

Table 3.

Change Scores From Baseline to Postintervention

| Control Participants Scores (n = 20) | Intervention Participant Scores (n = 60) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Scores | Mean Scores | ||||||

| Module Topic | Premodule (%) | Standard Training (%) | Premodule (%) | Postmodule (%) | p- Value | ||

| Group counseling | 92.0 | 93.1 | 1.7 | 89.1 | 97.7 | 8.3 | <.001 |

| Individual counseling | 84.6 | 88.8 | 4.1 | 90.2 | 95.3 | 5.0 | <.001 |

| Partner testing | 88.3 | 93.1 | 5.1 | 88.9 | 92.3 | 3.2 | .097 |

| 7 days after start | 82.4 | 85.5 | 3.5 | 82.3 | 87.0 | 3.9 | .031 |

| 30 days after start | 83.7 | 87.1 | 2.5 | 84.3 | 88.5 | 4.3 | .006 |

| Family planning | 87.3 | 87.2 | −0.3 | 85.5 | 88.0 | 2.6 | .024 |

| Clinical analyses | 74.7 | 73.3 | −1.3 | 75.0 | 80.9 | 5.7 | <.001 |

| M&E | 75.4 | 76.0 | 0.3 | 74.8 | 76.8 | 1.9 | .298 |

| Overall scores | 82.8 | 84.3 | 1.6 | 83.1 | 87.9 | 4.7 | .044 |

Note. M&E = monitoring and evaluation.

The greatest postintervention improvements were found in the modules that related to group counseling (8.3%), clinical analyses (5.7%), and individual counseling (5.0%). These changes were statistically significant (p < .001) when compared with changes at control sites. Significant improvements were also found for the modules that related to 30 days after start (4.3%, p = .01), 7 days after start (3.9%, p = .03), and family planning (2.6%, p = .02). No statistically significant improvements were found between the groups on the partner testing (3.2%, p = .10) and monitoring and evaluation (1.9%, p = .30) modules (Table 3).

Nurse managers at intervention sites demonstrated a 9- to 10-fold greater knowledge improvement over nurse managers at control sites. Improvements from baseline scores at 1- and 3-month follow-up were 10 and 13%, respectively, and remained statistically significant (p < .0001). Strong effects were noted at all timepoints, with Cohen’s d ranging from 0.79 to 0.89 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup Analysis of Nurse Managers

| Mean Scores | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prescore (95% CI) | Postscore (95% CI) | ||||

| Pretest vs. postmodule assessment | 56 | 0.47(0.44–0.51) | 0.56 (0.53–0.58) | 0.09a | 0.79 |

| Pretest vs. 1-month follow-up | 48 | 0.48(0.440–0.515) | 0.61 (0.57–0.65) | 0.13a | 0.85 |

| Pretest vs. 3-month follow-up | 55 | 0.48 (0.44–0.52) | 0.58(0.55–0.61) | 0.10a | 0.89 |

p < .0001.

A total of 32 nurses were recruited from the intervention clinics across Sofala and Manica provinces for FGD to assess acceptability. Generally, nurses strongly accepted tablet-based clinical training for Option B+. In all three FGDs, nurses reported that, after initial training, the tablets were easy to use because they worked similarly to their personal touch screen smartphones. Content covered was deemed appropriate and valuable, covering new material or an area where refresher training was needed as illustrated by the following statement:

Useful to us because we learned more and had the opportunity to refresh our knowledge of cART management in pregnant women and family planning, how to counsel women, how to interpret the laboratory results, and what to do when the results change.

Nurses reported the tablets as an effective and engaging learning platform, especially when coupled with traditional supportive supervision; one nurse stated, “The materials used were clear and easy to understand. The questions asked were easy to understand because the trainers first lectured on the topic and then asked questions about it.” Everyone unanimously agreed that tablet training should continue with some improvements. Specific improvement areas included slowing down the video vignettes and offering an option to pause the videos so that viewers could read any written content that arose on the screen, adding additional videos to cover other aspects of the HIV care cascade (such as retention in care), and improving software to facilitate high speed uploads to the central server and production of real-time evaluation results.

Discussion

The nurses who received the tablet-based training for Option B+ improved their assessment scores threefold compared with the control group nurses (p = .04). In a subgroup analysis among nurse managers, those at intervention sites demonstrated a 9- to 10-fold greater improvement than those at control sites. The greatest improvement was found between the baseline and 1-month follow-up, with slight attenuation of scores noted at the 3-month postintervention assessment. Staff turnover at several health facilities and nurse scheduling may have contributed to this decrease in mean scores between the 1- and 3-month follow-up assessments. However, there did not seem to be a weakening impact over time, with strong effect sizes improving from 1 to 3 months postintervention (Cohen’s d = 0.85 and d = 0.89, respectively). Previous Option B+ training among health workers at control (20%) and intervention (27%) sites differed, but not enough to influence postintervention outcomes.

With the advancement of online technologies, training clinical competency skills by using computerized or blended learning strategies is expanding globally (Gimbel, Kawakyu, Dau, & Unger, 2018). Previous mobile technology research in Mozambique has targeted clinical decision making, health counseling, data collection, and patient care coordination of community health care workers (Batavia & Kaonga, 2014; Nhavoto, Gronlund, & Klein, 2017). This is the first study in Mozambique to demonstrate that mLearning through tablets is an engaging, acceptable, and effective platform for frontline health worker training, especially when coupled with traditional face-to-face supportive supervision.

Innovative training tools adapt to workplace realities that build on the idea that baseline clinical competencies for mid-level nurses are urgently needed to maximize investments in Option B+ expansion, including effective PMTCT and improved long-term survival for HIV-infected women (Terry, Terry, Moloney, & Bowtell, 2018). Unlike previous training models geared toward physicians in Mozambique, the materials in this study were appropriate and effective for mid-level nurses, as evidenced by the statistically significant improvements between intervention and control groups in six of the eight modules. In three of those six modules, the improvements were highly significant (p < .001). In the remaining two modules, there were positive improvements in scores after the intervention, although these were not statistically significant. The findings are consistent with previous studies, where training modules with both video and didactic assessment components have been shown to be powerful, and potentially better than traditional in-service pedagogic approaches, for strengthening comprehension and information retention (McCutcheon, Lohan, Traynor, & Martin, 2015). This suggests that mLearning, which supplements on-site mentorship, has the potential to enhance nurses’ clinical competency skills and can be adapted by PMTCT programs that introduce Option B+ in contexts with a limited health workforce. Real-time data from competency assessments that are collected on a centralized data system can be used by district nurse supervisors to identify and develop targeted improvement efforts.

Stakeholder involvement has been hypothesized to significantly influence the successful implementation of a novel intervention (WHO, 2013). The formative assessment phase was an essential component of this study because it relied on engaging stakeholders and participatory approaches to help identify and address unique gaps in core competencies across MCH nurses in central Mozambique. This process, in conjunction with previous formative findings (Napua et al., 2016), guided the development of a tailored HIV clinical training program.

The MCH-TAB assembled for this project included University of Washington faculty, as well as scientists from CIOB, and MCH managers at provincial, district, and city levels. The MCH-TAB worked on content and script development, and the national level PMTCT workgroup reviewed all materials before production. The intervention was carried out by MCH supervisors with support from a nongovernmental partner organization, facilitating the intervention to be viewed as MOH led. The use of a local theater troupe, before filming, created a more authentic viewing environment for district and facility level nurses and nurse managers. This helped to ensure engagement across various MOH administrative levels (facility, subnational, and national). The involvement from provincial and district health departments, particularly in the initial development process, fostered strong buy-in and ownership. This broad engagement and leadership, in particular from host government entities, also facilitated the acceptance and perceived value of the tablet-based clinical training modality for Option B+ care.

Despite the fact that some software strategies have been shown to be effective in improving clinical knowledge, they may not always be used by the end users (Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989). If end users perceive the software to be useful, and if it is easy to use, then actual system use may be increased (Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989). In this study, the content was described as being useful and helped nurses to either refresh previously learned topics or to learn entirely new material. The observed and significant change in mean scores for most of the module topics are consistent with the nurses’ qualitative feedback. Acceptability of the intervention may have also been bolstered by culturally appropriate video vignettes, although that was not directly assessed.

Our approach for small break-out groups in our FDGs to assess end-user acceptability served to give all participants an opportunity to speak, particularly those who felt shy about speaking in a larger forum. The allotted time in small FGD allowed all participants time for reflection and an overall better discussion and opportunity to elicit honest feedback and suggestions for improvement.

Conclusions

Overall, tablet-based training has the potential to be an effective and sustainable training method for areas with limited resources and high training needs. This study demonstrates tablet-based mLearning as a feasible and acceptable tool to facilitate the introduction and scaling of Option B+ service delivery.

Limitations

Some limitations of this study should be considered. The contextually tailored development of the training vignettes diminishes the transferability of the modules to countries outside of Mozambique. Norms are periodically updated within Mozambique, potentially limiting the currency of the training vignettes. Ongoing updates can be expensive and time intensive when filming is involved. The mixed-method design relied on a multidisciplinary team of researchers that may be cost-prohibitive and not feasible; however, in many settings, Ministries of Health can leverage global partnerships with research universities, private and public organizations, and local artists and film makers to enhance capacity building strategies (Anderson et al., 2014; Collins, Glass, White-scarver, Wakefield, & Goosby, 2010).

The questions used to assess nurses’ knowledge and acceptability did not come from a validated psychometric tool but were developed by the MCH-TAB and study’s researchers, respectively, and were evidence-informed. Additionally, because of a limited number of rotating assessment questions, there was the possibility that questions may have been repeated, and thus test–retest bias may have influenced scores over time. This acceptability and feasibility study was insufficiently powered to determine intervention impact on PMTCT process or patient outcomes because of the lower than expected recruitment of participants at control facilities; however, the intervention did have a strong effect on nurse managers’ knowledge.

Key Considerations.

In settings where guidelines and protocols are updated frequently, mLearning is appropriate and feasible for rapidly training nurses in resource-limited settings.

Investment in collation of open access training libraries of video vignettes and accompanying assessments in high disease burden countries should be a priority.

The development of mLearning tools should involve key stakeholders, including end users, managers, policy makers, and donors, to ensure that they are tailored to the intended setting and scalable.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported through the University of Washington/Fred Hutch Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program under award number AI027757 (PI: S. Gimbel), which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NIA, NIGMS, and NIDDK.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson F, Donkor P, de Vries R, Appiah-Denkyira E, Dakpallah GF, Rominski S,… Ayettey S (2014). Creating a charter of collaboration for international university partnerships: The Elmina Declaration for human resources for health. Academic Medicine, 89(8), 1125–1132. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATLAS.ti Scientific Development GmbH [Computer software]. (2014).

- Batavia H, & Kaonga N (2014) mHealth support tools for improving the performance of frontline health workers: An inventory and analytical review. New York, NY: mHealth Alliance. [Google Scholar]

- Brunette W, Sudar S, Sundt M, Larson C, Beorse J & Anderson R (2017). Open data kit 2.0: A services-based application framework for disconnected data management. MobiSys, 440–452. doi: 10.1145/3081333.3081365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. (2013). Impact of an innovative approach to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV—Malawi, July 2011-September 2012. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62,148–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2006) Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Collins FS, Glass RI, Whitescarver J, Wakefield M, & Goosby EP (2010). Developing health workforce capacity in Africa. Science, 330(6009), 1324–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton H (2013). A historical overview of mobile learning: Toward learner-centered education Handbook of mobile learning (pp 3–14). Florence, KY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Davis F, Bagozzi RP, & Warshaw PR (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Dunleavy G, Nikolaou CK, Nifakos S, Atun R, Law GC, & Car LR (2019). Mobile digital education for health professions: Systematic review and meta-analysis by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. Journal of Medical Internet Research Electronic Resource, 21 (2), e12937. doi: 10.2196/12937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lao C, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Galiano-Castillo N, Caro-Morgan E, Diaz-Rodriguez L, & Arroyo-Morales M (2016). The effectiveness of a mobile application for the development of palpation and ultrasound imaging skills to supplement the traditional learning of physiotherapy students. BMC Medical Education, 16(1), 274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrinho P, Sidat M, Goma F, & Dussault G (2012). Task-shifting: experiences and opinions of health workers in Mozambique and Zambia. Human Resources for Health, 10(34), 34. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-10-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimbel S, Kawakyu N, Dau H, & Unger J (2018). A missing link: HIV-/AIDS-related mHealth interventions for health workers in low- and middle-income countries. Current HIV/AIDS Report, 15, 414–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habte D, Dussault G,& Dovlo D(2004).Challenges confronting the health workforce in sub-Saharan Africa. World Hospitals and Health Services, 40(2), 40–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDcap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interagency Task Team. (2014). Toolkit 2.0: expanding and simplifying treatment for pregnant women living with HIV: Managing transition to Option B/B+. Retrieved from https://www.childrenandaids.org/sites/default/files/2017-05/IATT-Toolkit-Dec-2014_JR-1-28-15-Web1.pdf

- Kober K & Van Damme W (2014). Scaling up access to antiretroviral treatment in southern Africa: who will do the job? Lancet, 364(9428), 103–107. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16597-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malawi Ministry of Health. (2014). Clinical management of HIV in children and adults. Retrieved from https://aidsfree.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/tx_malawi_2014.pdf

- McCutcheon K, Lohan M, Traynor M, & Martin D (2015). A systematic review evaluating the impact of online or blended learning vs. face-to-face learning of clinical skills in undergraduate nurse education. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(2), 255–270. doi: 10.1111/jan.12509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napua M, Pfeiffer JT, Chale F, Hoek R, Manuel J, Michel C,… Chapman PR (2016). Option B+ in Mozambique: Formative research findings for the design of a facility level clustered randomized controlled trial to improve ART retention in antenatal care. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 72(S2), S181–S188. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan V, Brown H, Pablos-Mendez A, Adams O, Dussalt G, Elzinga G,… Chen L (2004). Responding to the global human resources crisis. Lancet, 363(9419), 1469–1472. doi: 0.1016/S0140-6736(04)16108-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neath I (2018). Effect size calculator [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://memory.psych.mun.ca/models/stats/effect_size.shtml

- Nhavoto JA, Gronlund A, & Klein GO (2017). Mobile health treatment support intervention for HIV and tuberculosis in Mozambique: Perspectives of patients and healthcare workers. Plos One, 12(4), e0176051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donovan J, Kabali K, Taylor C, Chukhina M, Kading JC, Fuld J, & O’Neil E (2018). The use of low-cost Android tablets to train community health works in Mukono, Uganda, in the recognition, treatment and prevention of pneumonia in children under a five: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Human Resources for Health, 16(1), 49. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0315-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas L, Horwitz SM, Green C, Wisdom JP, Duah N, & Hoagwood K (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed-method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42(5), 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters DH, Tran NT,& Adam T (2013). Implementation research in health: A practical guide. Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- República de Moçambique Ministério da Saúde Direcçâo Nacional de Assistência Médica (Mozambique Ministry of Health). (2014). Guia de tratamento antiretroviral e infecções, oportunistas no adulto, adolescente, gravida e criança. Retrieved from https://aidsfree.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/4.25.16_mozambique_art_2014_rktagged.pdf

- Terry VR, Terry PC, Moloney C, & Bowtell L (2018).Face-to-face instruction combined with online resources improves retention of clinical skills among undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 61,15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. (2018). Children, HIV, and AIDS: The world today and in 2030. Retrieved from https://data.unicef.org/resources/children-hiv-and-aids-2030/#West%20and%20Central%20Africa

- World Bank. (2016). The human resources for health situation in Mozambique. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1007.2681&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- World Health Organization. (2011). mHealth: New horizons for health through mobile technologies. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_mhealth_web.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2016). Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: Recommendations for a public health approach. 2nd ed Retrieved from https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/arv-2016/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]