Abstract

Purpose

Despite advances in biologic therapy, approximately 10–15% of ulcerative colitis (UC) patients require surgery. We aimed to (1) examine the rates of emergent colectomy and elective ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) over time among UC patients in the USA and (2) investigate disparities in surgery rates by patient demographics.

Methods

Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2000 to 2014were analyzed. Inclusion criteria were admissions with a primary UC ICD-9-CM diagnosis code and age > 18. Emergent cases were defined as those admitted through the emergency room with an outcome ICD-9-CM code for subtotal colectomy. Elective IPAA cases were defined with an outcome ICD-9-CM code for IPAA, used as a surrogate measure of colectomy. Patient and hospital-level demographics were analyzed. Temporal trends of colectomy were analyzed utilizing joinpoint-regression analysis with calculation of annual percentage change (APC).

Results

A total of 470,708 admissions were included over the 14-year period. Emergent colectomy rate significantly declined (APC − 7.35%, p = 0.0002), while the rate of elective IPAA remained stable (APC − 0.21%, p = 0.8). Emergent colectomy rates declined similarly across all demographics, though not as marked among patients age 50 and older and Medicare patients. Elective IPAA rates were significantly lower among blacks and patients with public insurance.

Conclusions

There has been a significant decline in emergent UC colectomy rates in the USA; however, the overall need for surgery appears unchanged given stable IPAA rates. This suggests a limited impact on overall surgery rates with a shift from emergent to elective procedures.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, Colectomy, Ileal pouch anal anastomosis, Minority, Disparities

Introduction

Approximately 10–15% of ulcerative colitis (UC) patients will require surgery during their disease course [1]. The most common surgery for UC is the staged total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA), the first stage of which includes emergent or elective colectomy. Emergent colectomy is performed for UC patients with severe or fulminant colitis refractory to inpatient medical therapy. Colectomy is typically followed by completion proctectomy and elective IPAA construction 3 to 6 months after initial surgery [2].

Colectomy risk among patients with UC has decreased since the approval of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy in 2005 [3–6]. Multiple population-based studies in Canada and Europe have noted a decrease in colectomy rates secondary to the improved efficacy of medical management with immunomodulators and biologics [7–10]. Kaplan et al. reported an average annual percent change of − 4.3% in elective colectomy rates in Calgary between 1997 and 2009, and Reich et al. reported decreasing colectomy rates with increasing biologic use in Edmonton between 1998 and 2011 [7, 8]. Similar trends have been observed in Europe with reports from the prospective Swiss Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Cohort indicating a significant decline in annual colectomy rates after 2005 [10].

Data on colectomy rates since the advent of anti-TNF therapy in the USA has conflicted with that from Canada and Europe. In a retrospective review of a private insurance claims database between 2002 and 2013, Kin et al. noted an increase in the rates of colectomy or total proctocolectomy in patients diagnosed in the post-infliximab period [11]. Similarly, in a review of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) between 1991 and 2011, Geltzeiler et al. reported a 44% increase in the number of patients who required total abdominal colectomy and a shift towards staged restorative proctocolectomy [12]. Both studies suggest that biologic therapy has not decreased the risk of surgery for UC patients in the USA and has potentially resulted in patients that are more acutely ill by the time colectomy is pursued.

Given the presence of conflicting data, we aimed to [1] examine the rates of emergent colectomy and elective IPAA over time among UC patients in the USA, and [2] investigate disparities in surgery rates by patient demographics.

Methods

Study data and population

The study cohort was extracted from the NIS of Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The NIS database is a 20% stratified random sample of all hospital inpatient discharges from approximately 1000 hospitals from 40 states, capturing approximately 7 million hospitalizations through the USA. Geographic region, urban or rural location, teaching status, ownership, and bed size of hospitals were used as stratification variables. It contains in-depth information on patient demographics, payment source, total charges, length of stay, hospital characteristics, and outcomes. The consistency of coding and variables in the dataset is maintained by AHRQ using extensive preprocessing to reconcile variations in coding by individual states and definitions across them. The NIS database provides discharge weights, which can be used to derive national estimates from the representative sample of patients.

We analyzed data from the year 2000 to 2014 [13]. Institutional Review Board approval was not needed because of the de-identified nature of the data. The NIS was queried using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes to identify all admissions for UC patients [14]. The Clinical Classification Software (CCS) codes were used to define the primary diagnoses on admission. Patients less than 18 years of age were excluded.

Covariates

The following data were extracted from the NIS: patient-level characteristics including age, gender, race, quartile classification of median household income (extrapolated from zip code), primary payer status (Medicare/Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, or no charge), and hospital-level characteristics including geographical region, hospital bed size, and teaching status. The validated All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Group (APRDRG) score was used to account for severity of illness [15, 16].

Outcomes

The main outcome measure was the proportion of hospitalizations that resulted in surgery, stratified as either emergent colectomy or elective IPAA. Emergent colectomy cases were defined as those admitted through the emergency room with an outcome variable of ICD-9-CM code for subtotal colectomy (45.8). Elective IPAA cases were defined as elective admissions with an outcome variable of ICD-9-CM code for IPAA (35.05, 35.06). We used elective IPAA as a surrogate measure of the total surgery burden in UC since this is the definitive, final stage procedure for UC patients requiring colectomy. Elective colectomy cases were not included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

To obtain descriptive statistics, we followed recommended methodological standards for the NIS database as well as specific statements, such as SURVEYFREQ [13]. The Wald χ2 test was utilized for examining baseline characteristics for categorical variables (expressed in percentages), unpaired, two-tailed t test for normally distributed continuous variables reported as mean (± standard deviation), and the Wilcoxon signed rank test if continuous variables were not normally distributed. Temporal colectomy trends were evaluated with joinpoint regression analysis to identify statistically significant changes over time using the linear slope of the trend [17]. In joinpoint analysis, the best-fitted points where the rates changed significantly were chosen and added to the model. The best-fitted model was computed by permutation test, and annual percentage change (APC) was calculated by generalized linear models with a Poisson distribution. We then conducted subgroup analyses of emergent colectomy and IPAA rates over time stratified by race and insurance type. We used SURVEY procedures in SAS (v.9.4, Cary, N.C.) to account for stratification, clustering, and unequal weighting of the NIS survey design. Discharge weights provided in the NIS were used to generate nationally representative estimates for the U.S. population. For all statistical analyses, a two-sided p value of 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 470,708 hospitalizations with a primary admission ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for UC were identified between 2000 and 2014. Of these, 313,477 (66.6%) admissions were emergent while 157,243 (33.4%) admissions were elective (Table 1). Among patients admitted emergently, 10,160 (3.24%) required colectomy during admission. Among elective admissions, 16,953 patients (10.8%) underwent IPAA.

Table 1.

Total NIS Ulcerative Colitis (UC) Hospitalizations 2000–2014

| Type of UC hospitalization | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Emergent hospitalization | 313,477 |

| Colectomy | 10,160 (3.24%) |

| No colectomy | 303,317 (96.8%) |

| Elective hospitalization | 157,243 |

| IPAA | 16,953 (10.8%) |

NIS nationwide inpatient sample, IPAA ileal pouch anal anastomosis

We observed disparities in outcomes by patient demographics when conducting a pooled analysis of all UC admissions from 2000 to 2014. Compared to patients who only had medical management during their hospitalization (elective or emergent), patients who underwent emergent subtotal colectomy or elective IPAA were significantly older and more likely to be white, privately insured, or have a median household income greater than the 75th percentile for their zip code (Table 2). Patients who underwent emergent subtotal colectomy or elective IPAA also had significantly higher rates of co-morbid disease including depression and congestive heart failure compared to patients admitted for medical management (Table 2). Further, patients who underwent emergent colectomy or elective IPAA had higher levels of illness severity and mortality risk per the APR-DRGs scale as compared to those who underwent medical management (Table 3). The largest percentage of emergent subtotal colectomy and elective IPAA occurred in large hospitals, urban non-teaching hospitals, and in the South (Table 4). Mean length of stay was longest among patients who underwent emergent colectomy or elective IPAA and shortest among patients who received medical management (Table 3).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Patient characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total = 470,708 | No surgery (n = 443,595) | Emergent colectomy (n = 10,160) | Elective IPAA (n = 16,953) |

| Age in years, n (%) | |||

| Mean (± SE) | 49 ± (0.13) | 50 ± (0.39) | 40± (0.15) |

| Gender, n (%)a | |||

| Male | 205,460 (46.3) | 5391 (52.9) | 9573 (56.4) |

| Female | 237,518 (53.5) | 4782 (47) | 7375 (43.5) |

| Race, n (%)a | |||

| White | 271,770 (61.2) | 6542 (64.3) | 10,992 (64.8) |

| Black | 39,649 (8.9) | 539 (5.3) | 519 (3.1) |

| Hispanic | 35,734 (8.0) | 511 (5) | 603 (3.5) |

| Other | 18,363 (4.1) | 241 (2.3) | 723 (4.3) |

| Comorbidities, n (%)b | |||

| Depression | 39,770 (8.9) | 962 (9.4) | 1121 (6.6) |

| Congestive heart failure | 13,858 (3.1) | 497 (4.8) | 38 (0.2) |

| Coronary artery disease | 32,604 (7.3) | 618 (6.1) | 343 (2) |

| Hypertension | 110,935 (25.0) | 1915 (18.8) | 2057 (12.1) |

| Malnutrition | 26,153 (5.8) | 2370 (23.3) | 409 (2.4) |

| Coagulation disorder | 9575 (2.2) | 720 (7.1) | 173 (1) |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorder | 154,912 (34.9) | 4438 (43.6) | 1668 (9.8) |

| Median income per zip code, n (%)a | |||

| 0–25th percentile | 81,889 (18.4) | 1525 (14.9) | 2277 (13.4) |

| 26–50th percentile | 89,829 (20.2) | 1762 (17.3) | 3130 (18.4) |

| 51–75th percentile | 91,791 (20.6) | 1825 (17.9) | 3779 (22.2) |

| 76–100th percentile | 96,893 (21.8) | 2228 (21.8) | 4340 (25.6) |

IPAA ileal pouch anal anastomosis

Covariates did not add up to 100% due to missing data

Covariates did not add up to 100% in the table due to omitted “other” data

Table 3.

Index Admission Characteristics

| Index Admission Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total = 470,708 | No surgery (n = 443,595) | Emergent colectomy (n = 10,160) | Elective IPAA (n = 16,953) |

| APRDRG Risk Mortality Scale, n (%)a | |||

| Minor | 281,131 (63.3) | 3591 (35.3) | 12,875 (75.9) |

| Moderate | 73,595 (16.5) | 1797 (17.6) | 1388 (8.2) |

| Major | 27,562 (6.2) | 1530 (15.0) | 360 (2.1) |

| Extreme | 8264 (1.8) | 1389 (13.6) | 138 (0.8) |

| Length of stay, days n (%) | |||

| Mean (±SE) | 5.9 ± (0.02) | 19 ± (0.2) | 7.5 ± (0.05) |

| Primary payer type, n (%)a | |||

| Medicare | 121,641 (27.4) | 2857 (28.0) | 1038 (6.1) |

| Medicaid | 43,802 (9.8) | 921 (9.0) | 976 (5.8) |

| Private | 225,437 (50.8) | 5528 (54.3) | 13,890 (81.9) |

| Discharge disposition, n (%)b | |||

| Died | 3595 (0.8) | 632 (6.2) | 23.8 (0.1) |

IPAA ileal pouch anal anastomosis, APRDRG all patient refined diagnosis-related group

Covariates did not add up to 100% due to missing data

Covariates did not add up to 100% in the table due to omitted “other” data

Table 4.

Hospital level characteristics

| Hospital characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total = 470,708 | No surgery (n = 443,595) | Emergent colectomy (n = 10,160) | Elective IPAA (n = 16,953) |

| Hospital bed size, n (%)a | |||

| Small | 52,091 (11.7) | 716 (7) | 969 (5.7) |

| Medium | 111,461 (25.1) | 1888 (18.5) | 2633 (15.5) |

| Large | 278,806 (62.8) | 7560 (74.3) | 13,340 (78.7) |

| Hospital type, n (%)a | |||

| Rural | 47,663 (10.7) | 593 (5.8) | 184 (1.1) |

| Urban teaching | 182,145 (41.0) | 3091 (30.3) | 2314 (13.6) |

| Urban non-teaching | 212,551 (47.9) | 6479 (63.7) | 14,444 (85.2) |

| Hospital region, n (%)a | |||

| Northeast | 104,984 (23.6) | 2452 (24.1) | 4112 (24.2) |

| Midwest | 97,940 (22.0) | 2587 (25.4) | 4710 (27.7) |

| South | 154,224 (32.7) | 3527 (34.7) | 5881 (34.6) |

| West | 86,446 (19.4) | 1607 (15.8) | 2251 (13.2) |

IPAA ileal pouch anal anastomosis

Covariates did not add up to 100% due to missing data

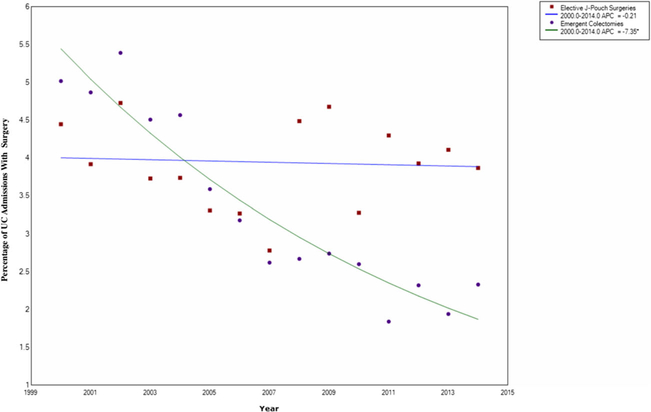

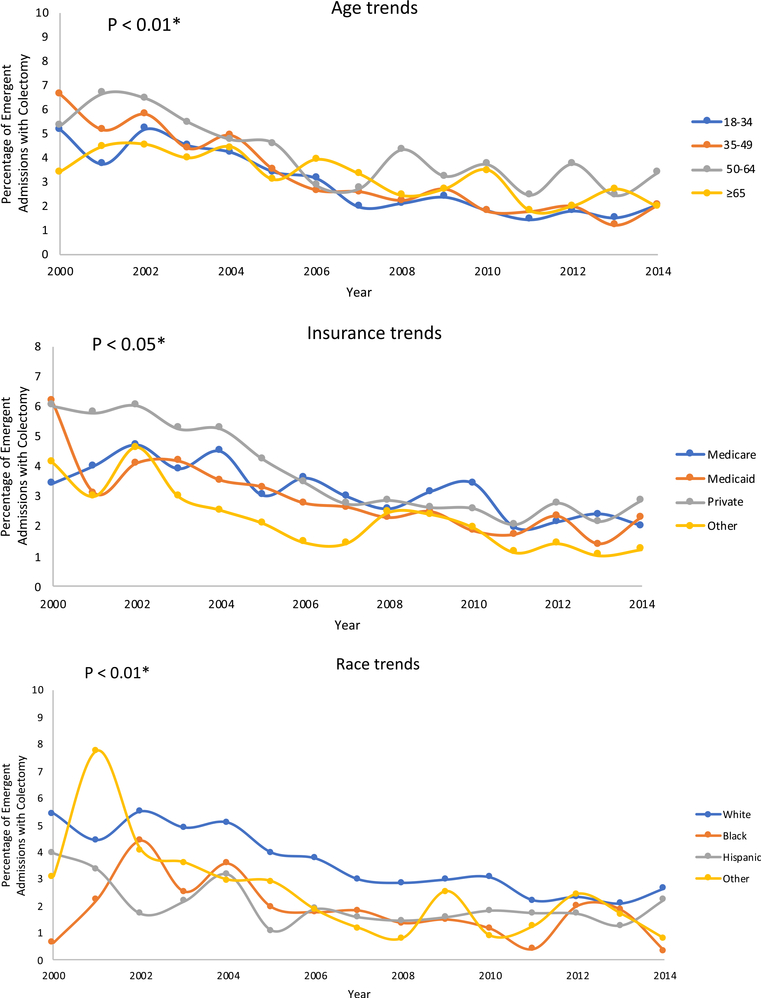

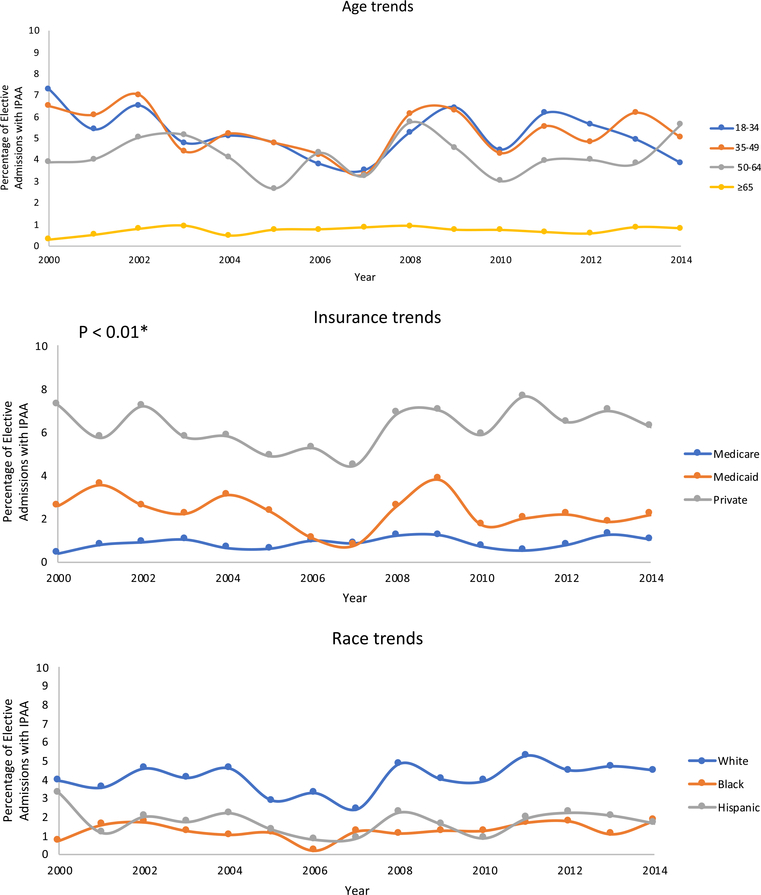

Between 2000 and 2014, the rate of emergent colectomy significantly declined (APC – 7.35%, p = 0.0002), while the rate of elective IPAA remained stable nationwide (APC – 0.21%, p = 0.8) (Fig. 1). Emergent colectomy rates declined similarly across all demographics, though not as marked among patients age 50 and older and among Medicare patients (Fig. 2a). There were no significant differences in emergent colectomy rates by race (Fig. 2a). IPAA rates remained consistently and significantly higher in white patients and those with private insurance over time (Fig. 2b). IPAA rates were consistently and significantly lower among patients age 65 and older (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 1.

Emergent colectomy and elective IPAA rates during UC admissions. Emergent colectomy rate significantly declined (APC – 7.35%, p = 0.0002), while the rate of elective IPAA remained stable (APC – 0.21%, p = 0.8). UC ulcerative colitis, APC annual percent change

Fig. 2.

a Differences in emergent colectomy rates based on age, insurance status, and race. Rates of emergent colectomy declined similarly over time across demographics, though not as marked among patients aged 50 and older and among Medicare patients. There were no significant differences in emergent colectomy rates by race. n.s. not significant. b Differences in elective IPAA rates based on age, insurance status, and race. Ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) rates were consistently and significantly lower among patients age 65 and older. IPAA were similarly stable over time across demographics but were consistently higher among whites and private insurance patients

Discussion

We observed that over a 14-year time period, the rates of emergent colectomy significantly declined, while the rates of elective IPAA remained stable in the US NIS cohort. There were significant disparities in IPAA rates based on race and insurance. Patients who were black, Hispanic, or had public insurance were less likely to undergo IPAA. IPAA rates were highest in white patients and those with private insurance consistently over time.

The noted decline in emergent colectomy rates in our study is likely due to the increased use of biologics in the outpatient and inpatient setting. According to prescription and infusion medication data compiled in the Truven MarketScan Database, the proportion of UC patients in the USA using biologics between 2007 and 2015 significantly increased from 5.1 to 16.2%, while the proportion using immunomodulators and aminosalicylates remained relatively stable [18]. The decrease in emergent colectomy rates noted in the NIS cohort coupled with the aforementioned increase in biologic availability and use likely reflects an improvement in inpatient management of acute severe and fulminant UC as well as outpatient management leading to fewer severe cases requiring admission. Our results conflict with the previously published NIS review by Geltzeiler et al. likely because we considered emergent and elective procedures separately, as opposed to reporting all UC admissions and total colectomy procedures together [12].

The decrease in emergent colectomy rates, however, does not appear to be resulting in a decrease in overall surgery rates for UC patients in the USA. IPAA rates remained stable during the studied time period suggesting that the overall need for surgical UC management has remained unchanged. Rather, it is possible that more effective inpatient UC management with biologics has delayed surgery, shifting its acuity from emergent to elective. This has been noted in multiple single-center studies [6, 19]. Gibson et al. observed a significantly lower rate of emergent colectomy during infliximab induction among patients who received accelerated dosing as compared to those who received standard dosing. Long-term colectomy rates, however, were similar in the two groups at 2-year follow-up, indicating an unchanged overall need for colectomy and a shift from emergent to elective surgery. Our data suggest a similar phenomenon on a population level. In this context, our results differ from European and Canadian studies which reported an overall decrease in colectomy rates, likely because they studied slightly different time intervals and used geographically limited insurance databases unlikely to be as representative as the NIS [7, 8, 10].

We report significant disparities in IPAA rates among black and Hispanic patients and those with public insurance. It is not clear how much of these disparities are due to underlying disease biology, healthcare access, and/or cultural preferences. There is little published data on disease biology and severity among minorities; however, previous studies have reported a decreased colectomy risk in black patients compared to whites and an increased colectomy risk in Hispanic patients compared to whites [20–23]. The association of public insurance with minorities has been well established in multiple studies and likely contributes to the disparities observed in this cohort [24, 25]. Utilizing the NIS database, Nguyen et al. reported that black and Hispanic inflammatory bowel disease patients were more likely to receive public insurance compared to white patients and separately reported unchanged colectomy rates among black patients despite declining rates in white patients [24, 25]. The observed disparity in IPAA rates in our study among minorities with public insurance may be a result of differential access to health services and specialists, specifically gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons [26]. Furthermore, inadequate outpatient UC management may result in an increase in elective hospitalizations that would decrease overall IPAA rates. Finally, individual and cultural preferences among minorities may lead to less utilization of elective surgery, in this case IPAA [27, 28].

The NIS database has a number of strengths and limitations. The NIS database is a large, national, all-payer hospitalization database with geographic diversity and regional representation. It includes information on patient demographics and insurance, and spans a long timeframe. Limitations include that the NIS database relies on administrative codes, which increases the risk of misclassification bias. Furthermore, there is no clinical data such as colonoscopy or laboratory reports that would allow for assessment of disease extent or severity. In addition, NIS does not have information on medications and we are not able to directly assess impact of biologic use on colectomy and IPAA rates. Finally, it is impossible to link hospitalizations, track individual patients across time, or assess individual patient outcomes.

Due to the limitations of the NIS database, we utilized elective IPAA rates as a surrogate for total surgical burden in UC. However, not all patients who undergo subtotal colectomy will proceed to IPAA within the same year, or even at all. As such, we acknowledge possible alternative explanations for our results. First, early recognition of medically refractory UC patients and more expeditious elective admissions for subtotal colectomy may have resulted in the noted decline of emergent surgery rates. Second, it is possible that an increased proportion of patients who underwent emergent colectomy proceeded to IPAA over time and thus resulted in stable IPAA rates. However, given the marked negative APC in the emergent colectomy group, we would have expected an equivalent positive APC in the elective IPAA group.

We observed that rates of emergent colectomy significantly declined, while rates of elective IPAA remained unchanged in the USA between 2000 and 2014. Colectomies appear to be shifting from emergent to elective procedures likely reflecting improved medical management with the use of biologics. This study noted significant disparities in surgery rates based on race and insurance, with minorities and patients on Medicaid less likely to undergo elective IPAA. Given the emergence of UC as a global disease and its increasing incidence among minorities, further studies are needed to validate these noted disparities and investigate their etiology [29, 30].

Acknowledgments

Funding information RCU is supported by a Career Development Award from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation and an NIH K23 Career Development Award (K23KD111995-01A1). RH is supported by a Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Career Development Award. This research did not receive grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethical standards

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fumery M, Singh S, Dulai PS et al. (2018) Natural history of adult ulcerative colitis in population-based cohorts: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 16(3):343–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF (2017) Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 389(10080):1756–1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarnerot G, Hertervig E, Friis-liby I et al. (2005) Infliximab as rescue therapy in severe to moderately severe ulcerative colitis: a randomized, placebo controlled study. Gastroenterology. 128:1805–1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gustavsson A, Jarnerot G, Hertervig E et al. (2010) Clinical trial: colectomy after rescue therapy in ulcerative colitis - 3-year follow-up of the Swedish-Danish controlled infliximab study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 32:984–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Lu J, Horgan K, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, de Villiers WJS, Present D, Sands BE, Colombel JF (2009) Colectomy rate comparison after treatment of ulcerative colitis with placebo or infliximab. Gastroenterology. 137: 1250–1260 quiz 1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aratari A, Papi C, Clemente V, Moretti A, Luchetti R, Koch M, Capurso L, Caprilli R (2008) Colectomy rate in acute severe ulcerative colitis in the infliximab era. Dig Liver Dis 40(10):821–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan GG, Seow CH, Ghosh S, Molodecky N, Rezaie A, Moran GW, Proulx MC, Hubbard J, MacLean A, Buie D, Panaccione R (2012) Decreasing colectomy rates for ulcerative colitis: a population-based time trend study. Am J Gastroenterol 107(12): 1879–1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reich KM, Chang HJ, Rezaie A, Wang H, Goodman KJ, Kaplan GG, Svenson LW, Lees G, Fedorak RN, Kroeker KI (2014) The incidence rate of colectomy for medically refractory ulcerative colitis has declined in parallel with increasing anti-TNF use: a time-trend study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 40(6):629–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore Se MGKM, Peterson S et al. (2014) Infliximab in ulcerative colitis: the impact of preoperative treatment on rates of colectomy and prescribing practices in the province of British Columbia, Canada. Dis Colon Rectum 57:83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parragi L, Fournier N, Zeitz J, Scharl M, Greuter T, Schreiner P, Misselwitz B, Safroneeva E, Schoepfer AM, Vavricka SR, Rogler G, Biedermann L, Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group, Anderegg C, Bauerfeind P, Beglinger C, Begré S, Belli D, Bengoa JM, Biedermann L, Bigler B, Binek J, Blattmann M, Boehm S, Borovicka J, Braegger CP, Brunner N, Bühr P, Burnand B, Burri E, Buyse S, Cremer M, Criblez DH, de Saussure P, Degen L, Delarive J, Doerig C, Dora B, Dorta G, Egger M, Ehmann T, el-Wafa A, Engelmann M, Ezri J, Felley C, Fliegner M, Fournier N, Fraga M, Frei P, Frei R, Fried M, Froehlich F, Funk C, Ivano Furlano R, Gallot-Lavallée S, Geyer M, Girardin M, Golay D, Grandinetti T, Gysi B, Haack H, Haarer J, Helbling B, Hengstler P, Herzog D, Hess C, Heyland K, Hinterleitner T, Hiroz P, Hirschi C, Hruz P, Iwata R, Jost R, Juillerat P, Brondolo VK, Knellwolf C, Knoblauch C, Köhler H, Koller R, Krieger-Grübel C, Kullak-Ublick G, Künzler P, Landolt M, Lange R, Serge Lehmann F, Macpherson A, Maerten P, Maillard MH, Manser C, Manz M, Marbet U, Marx G, Matter C, McLin V, Meier R, Mendanova M, Meyenberger C, Michetti P, Misselwitz B, Moradpour D, Morell B, Mosler P, Mottet C, Müller C, Müller P, Müllhaupt B, Münger Beyeler C, Musso L, Nagy A, Neagu M, Nichita C, Niess J, Noël N, Nydegger A, Obialo N, Oneta C, Oropesa C, Peter U, Peternac D, Petit LM, Piccoli-Gfeller F, Pilz JB, Pittet V, Raschle N, Rentsch R, Restellini S, Richterich JP, Rihs S, Ritz MA, Roduit J, Rogler D, Rogler G, Rossel JB, Sagmeister M, Saner G, Sauter B, Sawatzki M, Schäppi M, Scharl M, Schelling M, Schibli S, Schlauri H, Uebelhart SS, Schnegg JF, Schoepfer A, Seibold F, Seirafi M, Semadeni GM, Semela D, Senning A, Sidler M, Sokollik C, Spalinger J, Spangenberger H, Stadler P, Steuerwald M, Straumann A, Straumann-Funk B, Sulz M, Thorens J, Tiedemann S, Tutuian R, Vavricka S, Viani F, Vögtlin J, von Känel R, Vonlaufen A, Vouillamoz D, Vulliamy R, Wermuth J, Werner H, Wiesel P, Wiest R, Wylie T, Zeitz J, Zimmermann D (2018) Colectomy rates in ulcerative colitis are low and decreasing: 10year follow-up data from the Swiss IBD cohort study. J Crohns Colitis 12(7):811–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kin C (2017) Bundorf M. as infliximab use for ulcerative colitis has increased, so has the rate of surgical resection. J Gastrointest Surg 21(7):1159–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geltzeiler CB, Lu KC, Diggs BS, Deveney KE, Keyashian K, Herzig DO, Tsikitis VL (2014) Initial surgical management of ulcerative colitis in the biologic era. Dis Colon Rectum 57(12):1358–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (2018) Introduction to the HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS). HCUP Central Distributor [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poojary P, Saha A, Chauhan K et al. (2017) Predictors of hospital readmissions for ulcerative colitis in the United States: a National Database Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 23(3):347–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baram D, Daroowalla F, Garcia R et al. (2008) Use of the all patient refined-diagnosis related group (APR-DRG) risk of mortality score as a severity adjustor in the medical ICU. Clin Med Circ Respir Pulm Med 2:19–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sedman AB, Bahl V, Bunting E et al. (2004) Clinical redesign using all patient refined diagnosis related groups. Pediatrics. 114(4):965–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim H-J, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN (2000) Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 19(3):335–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu H, Maclasaac D, Wong JJ et al. (2018) Market share and costs of biologic therapies for inflammatory bowel disease in the USA. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 47(3):364–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson DJ, Heetun ZS, Redmond CE, Nanda KS, Keegan D, Byrne K, Mulcahy HE, Cullen G, Doherty GA (2015) An accelerated infliximab induction regimen reduces the need for early colectomy in patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 13(2):330–335.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen GC, Torres EA, Regueiro M, Bromfield G, Bitton A, Stempak J, Dassopoulos T, Schumm P, Gregory FJ, Griffiths AM, Hanauer SB, Hanson J, Harris ML, Kane SV, Orkwis HK, Lahaie R, Oliva-Hemker M, Pare P, Wild GE, Rioux JD, Yang H, Duerr RH, Cho JH, Steinhart AH, Brant SR, Silverberg MS (2006) Inflammatory bowel disease characteristics among African Americans, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic whites: characterization of a large north American cohort. Am J Gastroenterol 101:1012–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flasar MH, Quezada S, Bijpuria P, Cross RK (2008) Racial differences in disease extent and severity in patients with ulcerative colitis: a retrospective cohort study. Dig Dis Sci 53:2754–2760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sofia MA, Rubin DT, Hou N, Pekow J (2014) Clinical presentation and disease course of inflammatory bowel disease differs by race in a large tertiary care hospital. Dig Dis Sci 59:2228–2235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li D, Collins B, Velayos FS, Liu L, Lewis JD, Allison JE, Flowers NT, Hutfless S, Abramson O, Herrinton LJ (2014) Racial and ethnic differences in health care utilization and outcomes among ulcerative colitis patients in an integrated health-care organization. Dig Dis Sci 59:287–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen G, Laveist T, Gearhart S et al. (2006) Racial and geographic variations in colectomy rates among hospitalized ulcerative colitis patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 4:1507–1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen GC, Bayless TM, Powe NR, LaVeist TA, Brant SR (2007) Race and health insurance are predictors of hospitalized Crohn’s disease patients undergoing bowel resection. Inflamm Bowel Dis 13:1408–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins KS, Hall A, Neuhaus CU (1999) S. Minority health: a chartbook. Commonwealth Fund, New York [Google Scholar]

- 27.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O II (2003) Defining culture competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparitis in health and health care. Public Health Rep 118(4):293–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, Epstein AM (1999) The effect of patients’ preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 341(22):1661–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW, Kaplan GG (2012) Increasing incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 142:46–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Afzali A, Cross RK (2016) Racial and ethnic minorities with inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: a systematic review of disease characteristics and differences. Inflamm Bowel Dis 22(8):2023–2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]