Abstract

Diverse patterns of life-course marijuana use may have differential health impacts for the children of users. Data are drawn from an intergenerational study of 426 families that included a parent, their oldest biological child, and (where appropriate) another caregiver who were interviewed ten times from 2002 to 2018; the current study used data from 380 families in waves 6-10. Analyses linked parent marijuana use trajectories estimated in a previous publication (Epstein et al., 2015) to child marijuana, alcohol, and nicotine use; pro-marijuana norms; internalizing; externalizing; attention problems; and grades using multilevel modeling among children ages 6 to 21. Four trajectories had been found in the previous study: nonuser, chronic, adolescent-limited, and late-onset. Results indicate that children of parents in the groups that initiated marijuana use in adolescents (chronic and adolescent-limited) were most likely to use substances. Children of parents in the late-onset group, where parents initiated use in young adulthood, were not at increased risk for substance use but were more likely to have attention problems and lower grades. Results held when parent current marijuana use was added to the models. Implications of this work highlight the importance of considering both current use and use history in intergenerational transmission of marijuana use, and the need to address parent use history in family based prevention. Prevention of adolescent marijuana use remains a priority.

Keywords: intergenerational transmission of substance use, marijuana use, marijuana norms, adolescent substance use, adolescent metal health

With the recent wave of legalization of marijuana use for adults, the percentage of U.S. adults currently using marijuana has doubled from 7% in 2013 to 13% in 2016 (McCarthy, 2016). The legalization of marijuana use in ten states and the District of Columbia is reflected in public perception that adult use is not harmful and does not need to be curtailed (Wills, Sandy, Yaeger, & Shinar, 2001). Indeed, unlike the documented negative consequences of marijuana use among adolescents (Volkow, Baler, Compton, & Weiss, 2014), the consequences of infrequent adult marijuana use to adults are relatively few (Cranford, Zucker, Jester, Puttier, & Fitzgerald, 2010; Henry, 2017; Wills et al., 2001). However, many adults are parents, and recent studies showed that marijuana use among parents has also increased (Henry & Augustyn, 2017; Kosterman et al., 2016). Parent marijuana use is particularly concerning because studies show that parent current substance use may be linked to adverse effects on child well-being, including a higher likelihood of child substance use (Andrews, Hops, Ary, Tildesley, & Harris, 1993; Bailey et al., 2016; Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Knight, Menard, & Simmons, 2014). What is unknown is whether marijuana use prior to parenthood is associated with the same negative child outcomes as current use; and if there are patterns of parent marijuana use, perhaps characterized by low frequency, that are less harmful for children. The current study uses an intergenerational design to examine the link between longitudinal patterns of parent marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood and their children’s well-being.

The Social Development Model

The current research questions are driven by the social development model (SDM), a theory that organizes risk and protective factors for problem behaviors, such as marijuana use, into an overall etiological model based on social control (Hasin, 2018), social learning (Hirschi, 1969), and differential association theories (Bandura, 1977). The SDM posits that individuals’ behavior, whether prosocial or antisocial (e.g., substance-using) is driven by socialization experiences in key domains, including the family, peers, school, work, and neighborhood. Individuals encounter opportunities to interact with others, and to the extent that interactions are rewarded, individuals develop social bonds, which motivate them to adopt the beliefs and to conform to the norms and values of the socializing context. External constraints, such as individual difference characteristics, position in the social structure, and policies and laws all determine the availability of opportunities for prosocial or antisocial encounters. Whether this process leads to healthy, prosocial, or unhealthy, antisocial behavior depends on the predominant behaviors and values of the socializing contexts (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Sutherland, 1973). According to the SDM, family, school, and peers are the most important socialization units in childhood (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins et al., 1992); the present study focuses on family, specifically on parental marijuana use.

Intergenerational Effects of Parental Marijuana Use

Parental substance use may lead to problems among children in a number of different ways, including via increased availability and access to substances in the home, modeling, and the message that drug use is acceptable or normative (Bailey, Hill, Oesterle, & Hawkins, 2006; Hawkins et al., 1992; Vakalahi, 2001). In models of alcohol use, parent use and abuse of alcohol have been theorized to negatively affect children by interfering with parenting, resulting in problem behaviors including alcohol use, internalizing or externalizing problems, and poor school performance (Chaffin, Kelleher, & Hollenberg, 1996; Hawkins et al., 1992; Lieb et al., 2002). Parents who use alcohol are less likely to employ effective parenting strategies and are less likely to engage with their children in loving and positive ways (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Catalano, Kosterman, Hawkins, Newcomb, & Abbott, 1996; Jackson & Dickinson, 2003), which is likely to have implications for a variety of child behaviors. Applying a similar framework to parent marijuana use, a number of studies have shown that postnatal parent marijuana use, both current and past, is associated with a higher likelihood of children initiating and continuing to use marijuana and other substances, as well as developing more positive marijuana norms (Bailey et al., 2016; Duncan, Duncan, Hops, & Stoolmiller, 1995; Jackson & Dickinson, 2006; Merikangas, Stolar, Stevens, & et al., 1998). Parental use of marijuana may also increase the risk of child use of other drugs, including cigarettes and alcohol (Bailey et al., 2016; Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2007; Merikangas et al., 1998), potentially via analogous mechanisms. For example, one study found that parents who met criteria for marijuana use disorder (but not use) were less likely to employ positive parenting strategies, which in turn predicted greater likelihood of child marijuana use (Hill, Sternberg, Suk, Meier, & Chassin, 2018).

Parent Marijuana Use: Current use and Past History

While research suggests that parental marijuana use is indeed harmful to children, our current understanding is limited by how parental marijuana use is typically operationalized and analyzed. First, some studies have combined parental marijuana use with the use of other illicit drugs (e.g., Brook et al., 2007; Thornberry, Krohn, & Freeman-Gallant, 2006), making it difficult to isolate the unique effect of parental marijuana use. Second, while the effect of parent current marijuana use has been explored (Bailey et al., 2016), the evidence for the effect of parents’ prior history of marijuana use on child substance use and other behavioral problems is mixed (see discussion by Knight et al., 2014). Whereas some studies have found that parents’ marijuana use during adolescence and young adulthood significantly predicted child marijuana use (Henry & Augustyn, 2017; Knight et al., 2014), others find that parents’ history of use did not predict child behavior (Bailey et al., 2016). Third, whether parent marijuana use may be associated with other child behaviors beyond substance use has been underexplored. One recent investigation showed that parental marijuana use was related to increased child impulsivity (Riggs, Chou, & Pentz, 2009), suggesting that parent marijuana use may be related to other areas of child health, such as other behavioral problems and mental health. Fourth, little is known about the risks of parent marijuana use among parents with a lifetime pattern of heavy use versus those who used infrequently and only in the past. In a recent discussion of intergenerational continuity and discontinuity, Loughran (2018) cautions against narrow definition of behavior when investigating intergenerational transmission and encourages using longitudinal data to better measure heterogeneity of behavior over time. Collectively, these gaps in knowledge limit our understanding of whether parent use history poses a risk factor for youth marijuana, beyond their current use. The current study offers a unique opportunity to compare longitudinal patterns of parent marijuana use to a wide range of child outcomes using prospectively collected data on both parents and children.

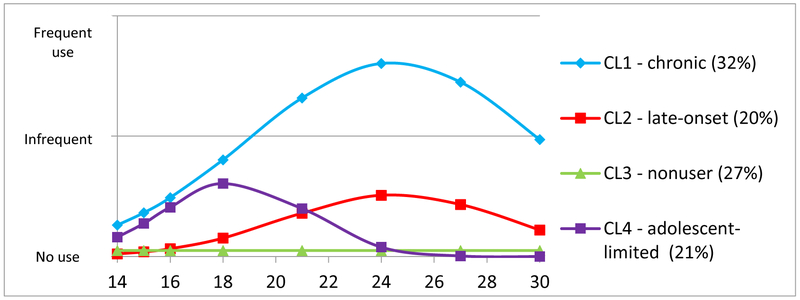

A number of studies have documented patterns or trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood, including variability in the timing of initiation, escalation, and desistence (Arria, Caldeira, Bugbee, Vincent, & O’Grady, 2016; Brook, Zhang, Leukefeld, & Brook, 2016; Epstein et al., 2015; Kosty, Seeley, Farmer, Stevens, & Lewinsohn, 2017; Suerken et al., 2016; White, Bechtold, Loeber, & Pardini, 2015). The current study follows the work of Epstein and colleagues (2015) who found four life-course patterns of marijuana use in a longitudinal community sample followed prospectively from ages 14 to 30 (n = 808). The first pattern was composed of nonusers (27% of the sample)—those who never or almost never used marijuana in their lifetime. Those who fell into the adolescent-limited pattern (21%) initiated marijuana use in adolescence, experienced moderate use at the peak use in the early 20s, and reduced use by age 27. The chronic use pattern (32%) was characterized by early initiation and escalation, and by frequent use, followed by consistent moderate use into the 30s. Finally, individuals in the late-onset pattern (20%) initiated use in late adolescence or their early 20s and continued infrequent but consistent use into adulthood.

Different patterns of marijuana use have been differentially linked to adult outcomes (Brook, Lee, Brown, Finch, & Brook, 2011; Ellickson, Martino, & Collins, 2004; Epstein et al., 2015; Juon, Fothergill, Green, Doherty, & Ensminger, 2011; Kosty et al., 2017; Zhang, Brook, Leukefeld, & Brook, 2016), including differences in substance use, mental health, criminal behavior, and economic outcomes. Consistent with other studies, Epstein et al. found that the chronic users reported the worst outcomes: by age 30, they were more likely to report substance abuse or dependence; be involved in crime; or report fewer close bonds with family, friends, or a significant other compared to nonusers. Those who used in adolescence (adolescent-limited and chronic users) were less likely to graduate from high school, complete a college degree, or be employed (or otherwise constructively engaged, such as volunteering or childcare) compared to nonusers. Late-onset users who initiated later and used infrequently were the least differentiated from nonusers, although they were more likely to be using substances in adulthood. Many marijuana-using adults do not quit marijuana use with the transition to parenthood (Chassin, Pillow, Curran, Molina, & Barrera, 1993), raising concerns about the unique risks that that past and current use may have on their child well-being. Little is currently known about whether different histories of marijuana use are associated with differential levels of risk for child outcomes, over and above current use.

The Current Study

About half of the adults in the Epstein et al. (2015) study have been followed as part of an intergenerational study, which collected data on both parents and their children. The current study builds on previous work and is driven by two research questions:

To what extent are parents' life-course patterns of parent marijuana use associated with children’s substance use and norms, functioning, and academic outcomes? and

Are these associations explained by parents’ current marijuana use, which is more likely to be present for some patterns compared to others?

We expect that children of parents in the chronic group will have the worst outcomes compared to other classes. We also expect that parents' class membership will be most associated with child marijuana use and norms, though associations with mental and behavioral health are also hypothesized.

Method

Participants

The study uses data from two linked longitudinal studies, the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP) and The Intergenerational Study (TIP). SSDP began in 1985 when 808 fifth-grade students from 18 Seattle elementary schools were enrolled in the study (Hawkins, Kosterman, Catalano, Hill, & Abbott, 2005). Participants were followed annually from ages 10 to 16, then again at ages 18, 21 24, 27, 30, 33, and 39 (in 2014). When the participants were age 27 (2002), the TIP study recruited those SSDP participants who had become parents. Parents were eligible to participate in the TIP study if they had regular face-to-face contact with their oldest biological child; another caregiver (usually the other biological parent) was recruited, where available. In Wave 1, 271 parents participated; their children ranged in age from 2 to 13 (mean age = 8). Parents and children were then followed for ten waves of data in an accelerated longitudinal design. New TIP families were added on a rolling basis as more SSDP participants became parents. A total of 426 families participated in the TIP study between 2002 and 2018; across waves 1-10, children ranged in age from 1 to 29 years (mean age = 15); parents were age 27 in wave 1, age 34 in Wave 5, and age 43 in wave 10. The current study uses data from waves 5 to 10 where child outcomes were collected between ages 6 and 21 (N = 380 families).

The TIP parent sample is 60% female; 41% identified as White, 23% as African American, 19% as Asian/Pacific Islander, 4% as Native American, and 13% were multiracial. The sample of children in TIP is gender balanced (48% female) and ethnically diverse; about a third identified as White (36%), 14% identified as Black, 34% identified as multiracial, 12% as Asian/Pacific Islander, and 4% as Native American. About 12% of parents and 11% of children identified as Hispanic.

Interviews with SSDP parents, children, and caregivers in the TIP study were timed around the child’s birthday, so that assessments were no more than 6 weeks before or after a birthday in order to obtain more precise developmental measurements, particularly for young children. Child surveys were tiered so that they progressed in length and depth with development; parent surveys similarly differentiated between younger and older children. Families completed surveys in person, on the web, or over the phone. Study measures and procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

SSDP participants were more likely to meet recruitment criteria for TIP if they were married and if they were mothers. Once eligible, participants were slightly less likely to participate if the parents identified as Asian American or had come from families with lower socioeconomic status. Recruitment of eligible participants into TIP averaged 82% over the ten waves; retention from wave to wave averaged 90%.

Measures

SSDP parent marijuana use from ages 14 to 30 was measured prospectively at each wave of SSDP; both past-month and past-year use was assessed. In the previous work, we used a 3-level coding of use employed by Schulenberg and colleagues (Epstein et al., 2015; Schulenberg et al., 2005) where no use was coded as 0, using fewer than three times in the past month and fewer than 20 times in the past year was coded as 1 “infrequent use,” and using three times or more in the past month or more than 20 times in the past year was coded as 2 “frequent use.” The four resulting trajectory groups were included in the current analyses: chronic, adolescent-limited, late-onset, and nonuser. The trajectories were included as time-fixed predictors with either the nonuser or the chronic use as referent groups (see Analysis). Parent current use in waves 5-10 of the TIP study was coded using self-reports of past-year use: any use (1) versus no use (0), and was considered a time-varying covariate.

Child substance use was reported by the child prospectively starting from age 6 for alcohol and tobacco use (N = 380) and age 10 for marijuana use (N = 338). In each wave, children were asked whether they have used marijuana, drunk alcohol “other than a sip or two,” or smoked cigarettes in the past year. For each substance, any past-year use was coded as 1, no use was coded as 0.

Child marijuana norms were reported by the child in each wave of the study starting from age 10 (N = 338). Children reported on whether they thought it was “okay for someone your age to use marijuana,” whether “using marijuana is a way to make friends with other people,” whether “using marijuana makes people worry less,” and whether “it hurts people if they use marijuana regularly.” Response options were 1 "NO!" 2 "no" 3 "yes" 4 "YES!" The items were averaged in each wave, with the last item reverse coded to reflect more pro-drug attitudes (at waves 6—7 with maximum sample size, alpha = .77).

Child internalizing, externalizing, and attention problems were all reported by parents as part of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL, Achenbach, 1991) between ages 6 and 18 (N = 368). Internalizing problems included anxiety and depression symptoms. Parents were asked whether each of the symptoms was 0 "not true," 1 "sometimes true," and 2 "often true" for their child.

Child grades were reported by parents at each wave from age 6 until age 18 (N = 368). Grades were reported as (1 = “mostly Ds” to 4 = “mostly As”).

Control variables included parent education, parent gender, parent ethnicity, child gender, and child birth cohort.

Analysis

The current analyses are based on the growth mixture model solution reported by Epstein et al. (2015) using the SSDP sample that identified four trajectories of parental use: chronic, adolescent-limited, late-onset, and nonuser. Trajectories were modeled when parents were 14-30 years old. The child outcomes examined here begin 4 years later, starting when parents were 34 years old, ensuring temporal order. We used the most likely class membership to place individuals in classes and limited the sample only to TIP participants. We chose to use the existing trajectories instead of re-estimating with a smaller TIP-only sample because a) the original trajectory solution was based on a universal community-based sample, rather than an indicated (parents only) sample, making the solution more generalizable, and b) limiting new trajectory estimation to only those participants in the TIP study would likely bias the new solution due to lower statistical power. Additionally, we are currently unaware of a statistical solution that would be able to have both predictors (parent marijuana use) and outcomes (child health) in the model such that the original solution was not altered or conditioned by the outcomes. Saving out class membership can sometimes lead to bias; however, in the current study, class memberships correlated with posterior probabilities at .89-.96, leaving us confident that bias was minimal.

We used multilevel modeling in HLM (Grekin, Brennan, & Hammen, 2005) to model change in child outcomes over time. Data were analyzed by child age, ranging from age 6 (for tobacco and alcohol use, CBCL scales, and grades) or age 10 (for marijuana use and norms) until age 21. Child age was used as the "time" variable in the analyses, with age centered at 18 years to capture maximum variation across all outcomes. We included both linear and quadratic slopes to follow age-grade curves. Marijuana, alcohol, and cigarette use were treated as binary (Bernoulli distribution in HLM), whereas the rest of the outcomes were treated as continuous. Missing data at level 1 (outcomes and time-varying covariates) was handled with Empirical Bayes estimation (Goodwin et al., 2018; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Missingness due to omitted responses was low across the eight models (range: 7-11%, average: 8.3%).

A set of models for each of the eight outcomes included age and age squared as time-varying predictors (see top half of Table 1). Demographic controls, and dummy-coded parent marijuana trajectories (e.g., chronic, nonuser) were treated as time-fixed covariates regressed onto the intercept. (Effects of the demographics on the slope were also tested but were largely nonsignificant; there were no effects on slope of parent trajectory groups.) The chronic, adolescent-limited, and late-onset classes were compared to nonuser class.

Table 1.

Associations Between Parent Marijuana Use Trajectory Class Membership and Child Outcomes

| Child outcomes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marijuana use |

Alcohol use |

Cigarette use |

Marijuana norms |

Internalizing | Attention problems |

Externalizing | Low grades |

|

| Parent use group | ||||||||

| Parent trajectory group (nonuser ref) | Odds ratio (OR) | Beta (β) | ||||||

| Chronic | 4.40*** | 2.75** | 2.28+ | 0.20* | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.07* | 0.20* |

| Adolescent-limited | 2.58* | 1.82+ | 1.96 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 |

| Late-onset | 1.05 | 1.68 | 0.56 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.11+ | 0.05 | 0.26* |

| Nonuser (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Age trend | ||||||||

| Age | 1.41*** | 1.47*** | 1.32** | 0.21*** | 0.04*** | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08*** |

| Age2 | 0.91** | 0.96* | 0.96 | 0.01** | 0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01** |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Parent gender (male) | 0.57 | 0.86 | 0.77 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.06 |

| Parent Black | 0.44* | 0.28 | 0.33** | −0.04 | −0.06+ | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.23** |

| Parent Asian | 0.49 | 0.68*** | 0.17* | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.11* | −0.06+ | −0.33*** |

| Parent Native | 1.28 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| Parent education | 1.08 | 1.27* | 1.19 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.03+ | −0.01 | −0.09** |

| Child birth cohort | 0.95 | 0.92+ | 0.83** | 0.03** | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02* |

| Child gender (male) | 0.97 | 0.68 | 0.53+ | 0.07 | −0.06* | 0.08* | 0.02 | 0.28*** |

| Parent trajectory group (nonuser ref) | Odds ratio (OR) | Beta (β) | ||||||

| Chronic | 1.80 | 2.07 | 1.57 | 0.17+ | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Adolescent-limited | 2.90* | 2.03+ | 2.00 | 0.16+ | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Late-onset | 1.06 | 1.67 | 0.58 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.26* |

| Nonuser (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Age trend | ||||||||

| Age | 1.52*** | 1.53*** | 1.41** | 0.21*** | 0.04*** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08*** |

| Age2 | 0.93* | 0.97+ | 0.97 | 0.01** | 0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01* |

| Parent marijuana use (current) | ||||||||

| Parent use | 3.99** | 2.23* | 2.47+ | 0.14+ | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.17** |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Parent gender (male) | 0.54 | 0.82 | 0.60 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.021 | −0.01 | −0.08 |

| Parent Black | 0.43* | 0.23*** | 0.27** | −0.04 | −0.07+ | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.18* |

| Parent Asian | 0.41 | 0.70 | 0.19* | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.11* | −0.07* | −0.34*** |

| Parent Native | 1.05 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Parent education | 1.14 | 1.25* | 1.17 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.03+ | −0.01 | −0.09*** |

| Child birth cohort | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.86* | 0.03*** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.02* |

| Child gender (male) | 0.97 |

0.70 | 0.54 | 0.07 | −0.07** | 0.07+ | 0.02 | 0.29*** |

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10

The bottom half of Table 1 presents similar analyses that also include parent current marijuana use as a time-varying covariate. Parent current use is an important predictor of child outcomes and is also likely to be correlated with marijuana use class membership because parents in some groups (e.g., chronic users) were more likely to be currently using marijuana than others (e.g., nonuser). Thus, this control shows the degree to which current parent marijuana use mediated the relation between life-course pattern of use and child outcomes. However, we also expected that controlling for parent current marijuana use will dampen the overall pattern of findings for those classes with higher rates of continuing marijuana use because it will confound trajectory and current use.

Results

Descriptive Findings

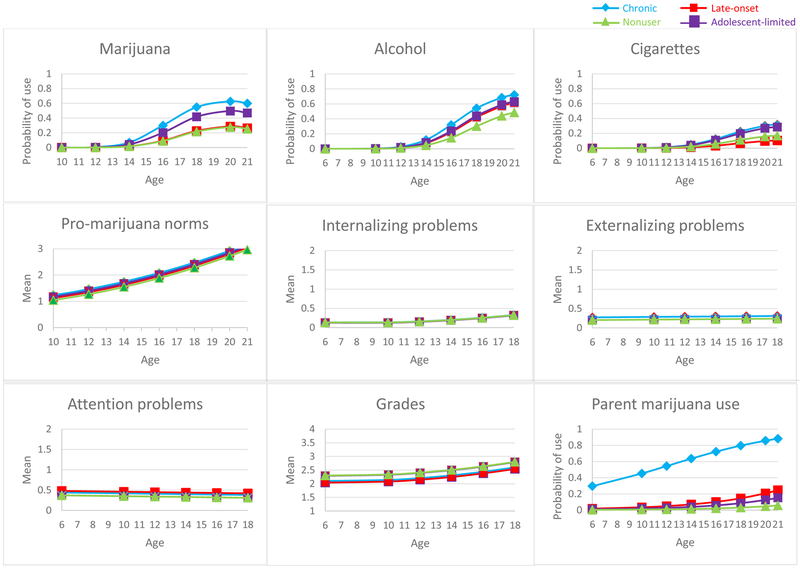

Parents from each of the four life-course marijuana use classes were well represented in the TIP study. About half of chronic users (46%; N = 115), nonusers (48%; N = 132), and late-onset users (42%; N = 52) were enrolled in the TIP study. Adolescent-limited users were slightly more likely to be enrolled in TIP (55%, p = .02; N = 84) than the other three types of users. About a third of the parents (N = 141, 36%) reported any use of marijuana during the any of the examined six waves of TIP. Parents in the chronic group were most likely to report current use at any of the waves (80%) compared to late-onset users (32%), adolescent-limited users (22%), and nonusers (10%). Parents in the chronic group also reported greater average frequency of use across the six waves (between weekly and several times a month) than any of the other groups (p < .001). Parents in the late-onset and adolescent-limited groups reported an average of less than monthly use, with parents in the late-onset reporting slightly more frequent use than adolescent-limited parents (p = .058). Among children, 32% reported ever using marijuana, 35% reported lifetime alcohol use, and 17% reported ever using cigarettes before age 21. On average, children reported low pro-marijuana norms (M = 1.87, between "1 = NO!" and "2 = "no"), low levels of internalizing (M = 0.22), externalizing (M = 0.23), and attention problems (M = 0.26), all between "0 = not true" and "1 = sometimes true" on the Child Behavior Checklist scale; and good grades (M = 3.21, B average). Figure 2 shows predicted probabilities of each of the eight child outcomes, as well as current parent marijuana use, stratified by parent marijuana trajectory class.

Figure 2.

Predicted probabilities of child outcomes and parent current marijuana use by parent trajectory.

Child Outcomes by Parent Marijuana Trajectory

Table 1 shows the predicted probability of child outcomes at age 18 as predicted by the parent marijuana trajectory groups, age and age squared trends, and the demographic correlates. Most outcomes followed a quadratic curve with the exception of cigarette use, internalizing, and attention problems (Table 1, top half). Compared to children of nonusers, children of adolescent-limited users and chronic users had a 2.5 to 4.4 times greater odds of using marijuana and 1.8 to 2.75 times the odds of using alcohol. Children of chronic users also had (marginally) greater odds than children of nonusers to use cigarettes; and reported more pro-marijuana norms, externalizing behaviors, and lower grades. Children of late-onset users did not differ from children of nonusers in their likelihood of substance use, marijuana norms, or externalizing behavior; but they did report more lower grades and (marginally) more attention problems. There was no difference between children of different types of users in internalizing behaviors.

Class Differentiation Accounting for Current Parent Marijuana Use

Next, we added parent current marijuana use to the set of models described above. Parent marijuana use was associated with greater likelihood of child use of marijuana, alcohol, and (marginally) cigarette use (Table 1, lower half). Parent use was also associated with lower grades and (marginally) more pro-marijuana norms. After accounting for current parent use, most differentiation between children of parents in the chronic and nonuser was lost, with the exception of marginal findings of more pro-marijuana norms and more externalizing symptoms. This is unsurprising since the vast majority of chronic use parents were current marijuana uses, and thus the effect of trajectory was confounded with current use. What remained constant, however, is the elevated risk of child marijuana and alcohol use and more pro-marijuana norms for children of adolescent-limited parents compared to children of nonusers. Children of late-onset parents continued to report lower grades.

As sensitivity analyses, we entered class membership probability instead of assigned class to the same set of regression models. There were no differences in the pattern of results, likely because most probabilities were > .90. We also examined interactions between trajectory group and current use to test whether current use was differentially associated with child outcomes for some parents compared to others. None of the interactions were significant.

Discussion

The current study extends findings from an earlier investigation into the course of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood (Epstein et al., 2015), which found that patterns characterized by adolescent marijuana use (adolescent-limited and chronic) were associated with poorer functioning in the 30s (compared to late-onset and nonuser patterns). This was true even for users in the adolescent-limited group who largely desisted from use in their early 20s. The current analyses examined health outcomes of the children of participants in the previous study. Over the course of six waves of child outcome data, children of parents in the chronic and adolescent-limited use groups had greater odds of marijuana and alcohol use compared to children of parents in the nonuser group. Children of late-onset users did not report more, substance use risk, but did report lower grades compared to nonusers. These findings held for adolescent-limited and late-onset groups after parent concurrent marijuana use was included in the models, suggesting that although parent current use is an important risk factor for child health, parents' history of marijuana use poses additional risk, particularly for marijuana use and norms. The current findings reinforce the importance of parents abstaining from marijuana use as current use was associated with child substance use and academic achievement. Results also underscore the need to prevent adolescent marijuana use or delay onset until adulthood.

It is important that the message regarding the degree of harm conferred by parent marijuana use history is communicated to parents so that they can make informed parenting decisions. Parent history marijuana use may also be an important indicator of risk factors to gauge for children's primary care practitioners. Because legalization of marijuana sends a message that marijuana use is safe, it is especially important to remind parents that regular marijuana use among adolescents is related to a number of negative consequences, including mental health problems, school underachievement, and substance use problems (Hall, 2015; Silins et al., 2014; Volkow et al., 2014). It is not yet clear why children of parents with adolescent-limited history of marijuana use were at higher risk of marijuana use and more promarijuana norms. One likely mediator is parent norms about adolescent substance use more generally, since parents in the adolescent-limited group reported higher rates of alcohol and tobacco use during their teens; it is possible that parents who themselves used as adolescents send a message to their children that it is ok to use substances.

Strengths and Limitations

Findings from the current study should be considered in light of the study’s strengths and limitations. The current study is the first step to identifying the associations between parents' lifetime patterns of marijuana use and their children's health. However, it is important to recognize that patterns of marijuana use are associated with different outcomes for parents as well (Epstein et al., 2015), possibly mediating the relation between parent marijuana use trajectories and child health. While the scope of the current study is limited to establishing the link between trajectories and child outcomes, future studies need to examine which parent behavior mediates which child outcomes to better inform preventive interventions with families of current or former marijuana users.

Second, findings from this study add mixed findings to the question of whether parent marijuana use poses risk to children beyond substance use outcomes. There were few significant associations between either current or historic marijuana use and internalizing, externalizing, or attention problems. Previous studies have not found consistent evidence that use of marijuana was related to generally poor parenting practices (Hill et al., 2018; but see Kerr, Tiberio, & Capaldi, 2015), which may explain lack of effects on general child functioning. On the other hand, current use and late-onset pattern of use were both associated with lower grades, which points to a dispersion of risk for children beyond substance use. More examinations of the potential links between parent marijuana use history and child outcomes are needed.

Third, although the sample of parents and youth is ethnically and socioeconomically diverse, it is drawn primary from Washington State. Fourth, the current analyses were based on a previous study that found four patterns of marijuana use among 14- to 30-year-olds from a community sample. Because not all participants in the SSDP study had children and participated in the TIP study, some of the resulting parent groups are rather small. Further, other investigations have reported different patterns of use, including increasing and decreasing (Ellickson et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2016), which are not examined here. Future investigations of marijuana use within a legal environment may also find other patterns of use that were not evident while marijuana use was not legal. Finally, the role of prenatal marijuana use in child development also needs to be examined. Future work should considers the role that frequency and quantity of parent marijuana use, both currently and historically, play in predicting child health in order to offer parents concrete guidelines for “safer” use.

Taken together, the strengths of the current study outweigh these weaknesses. It is the first study of its kind to link longitudinal patterns of parent marijuana use to child outcomes. Analyses take advantage of the two linked longitudinal studies that allowed both prospective differentiating of marijuana trajectories as well as prospective reports of child outcomes. The high sample retention and well-validated measures also strengthen the findings considerably and introduce new avenues for investigation in the future.

Implications

Researchers and public health advocates need to establish a body of research to modify existing prevention messages targeting parents to reflect a new context within which marijuana use may be considered from a harm reduction perspective. Such perspectives should consider parent marijuana use history and frequency, as well as any current use and establish a threshold of safe use. Factors that explain the relationship between history of marijuana use and child health risks need to be examined in order to appropriately intervene with parents who use marijuana or have a history of marijuana use. Prevention programs that are specifically targeted toward marijuana-using parents need to be developed to include messages regarding how parents can discuss marijuana (and other substance) use when they are users themselves. All prevention programs need to address parents" history of marijuana use and how it may shape parenting strategies around adolescent marijuana use. Previous studies have shown that parenting practices, including messages regarding abstinence from substances, can still be effective even if parents themselves use (Jackson & Dickinson, 2003, 2006), suggesting that parents who legally use marijuana can still be effective at reducing the likelihood that their children initiate drug use in adolescence.

Figure 1.

Parent life course marijuana use trajectories.

Epstein, M., Hill, K. G., Nevell, A. M., Guttmannova, K., Bailey, J. A., Abbott, R. D., Kosterman, R., & Hawkins, J. D, Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence into adulthood: Environmental and individual correlates, Developmental Psychology, 51, 1650-1663, 2015, American Psychological Association, reprinted with permission.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) [grant numbers R01DA023089, R01DA012138, R01DA033956, R01DA009679]. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency. NIDA played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of this report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research held in Washington, DC in June 2017.

Contributor Information

Marina Epstein, University of Washington.

Jennifer A. Bailey, University of Washington

Madeline Furlong, University of Washington.

Christine M. Steeger, University of Colorado Boulder

Karl G. Hill, University of Colorado Boulder

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Ary D, Tildesley E, & Harris J (1993). Parental influence on early adolescent substance use: Specific and nonspecific effects. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 13(3), 285–310. [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Bugbee BA, Vincent KB, & O’Grady KE (2016). Marijuana use trajectories during college predict health outcomes nine years post-matriculation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 159, 158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Hill KG, Guttmannova K, Epstein M, Abbott RD, Steeger CM, & Skinner ML (2016). Associations between parental and grandparental marijuana use and child substance use norms in a prospective, three-generation study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(3), 262–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Hill KG, Oesterle S, & Hawkins JD (2006). Linking substance use and problem behavior across three generations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34(3), 263–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Lee JY, Brown EN, Finch SJ, & Brook DW (2011). Developmental trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: Personality and social role outcomes. Psychological Reports, 108(2), 339–357. doi: doi: 10.2466/10.18.PR0.108.2.339-357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Ning Y, Balka EB, Brook DW, Lubliner EH, & Rosenberg G (2007).Grandmother and parent influences on child self-esteem. Pediatrics, 119(2), e444–e451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Zhang C, Leukefeld CG, & Brook DW (2016). Marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: Developmental trajectories and their outcomes. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(10), 1405–1415. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1229-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, & Hawkins JD (1996). The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior In Hawkins JD (Ed.), Delinquency and crime: Current theories (pp. 149–197). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Newcomb MD, & Abbott RD (1996). Modeling the etiology of adolescent substance use: A test of the social development model. Journal of Drug Issues, 26(2), 429–455. doi: 10.1177/002204269602600207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Kelleher K, & Hollenberg J (1996). Onset of physical abuse and neglect: Psychiatric, substance abuse, and social risk factors from prospective community data. Child abuse & neglect, 20(3), 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pillow DR, Curran PJ, Molina BS, & Barrera M Jr. (1993). Relation of parental alcoholism to early adolescent substance use: A test of three mediating mechanisms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102(1), 3–19. doi: doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.102.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA, Zucker RA, Jester JM, Puttler LI, & Fitzgerald HE (2010). Parental alcohol involvement and adolescent alcohol expectancies predict alcohol involvement in male adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(3), 386–396. doi: 10.1037/a0019801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Hops H, & Stoolmiller M (1995). An analysis of the relationship between parent and adolescent marijuana use via generalized estimating equation methodology. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 30(3), 317–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, & Leonard KE (2007). A conceptual model for the development of externalizing behavior problems among kindergarten children of alcoholic families: Role of parenting and children"s self-regulation. Developmental Psychology, 43(5), 1187–1201. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Martino SC, & Collins RL (2004). Marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: Multiple developmental trajectories and their associated outcomes. Health Psychology, 23(3), 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Hill KG, Nevell AM, Guttmannova K, Bailey JA, Abbott RD, … Hawkins JD(2015). Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence into adulthood: Environmental and individual correlates. Developmental Psychology, 57(11), 1650–1663. doi: 10.1037/dev0000054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Cheslack-Postava K, Santoscoy S, Bakoyiannis N, Hasin DS, Collins BN, … Wall MM (2018). Trends in cannabis and cigarette use among parents with children at home: 2002 to 2015. Pediatrics, 747(6), e20173506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grekin ER, Brennan PA, & Hammen C (2005). Parental alcohol use disorders and child delinquency: The mediating effects of executive functioning and chronic family stress. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66(1), 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall WD (2015). What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use? Addiction, 770(1), 19–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS (2018). US epidemiology of cannabis use and associated problems. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(1), 195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, & Miller JY (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 64–105. doi: doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hill KG, & Abbott RD (2005). Promoting positive adult functioning through social development intervention in childhood: Long-term effects from the Seattle Social Development Project. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 759(1), 25–31. doi: doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry K (2017). Fathers’ alcohol and cannabis use disorder and early onset of drug use by their children. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(3), 458–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry K, & Augustyn MB (2017). Intergenerational continuity in cannabis use: The role of parent"s early onset and lifetime disorder on child’s rarly onset. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(1), 87–92. doi: 10.1016/jjadohealth.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill M, Sternberg A, Suk HW, Meier MH, & Chassin L (2018). The intergenerational transmission of cannabis use: Associations between parental history of cannabis use and cannabis use disorder, low positive parenting, and offspring cannabis use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 32(1), 93–103. doi: 10.1037/adb0000333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T (1969). Causes of delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, & Dickinson D (2003). Can parents who smoke socialise their children against smoking? Results from the Smoke-free Kids intervention trial. Tobacco Control, 12(1),52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, & Dickinson D (2006). Enabling parents who smoke to prevent their children from initiating smoking: Results from a 3-year intervention evaluation. Archives Of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160(1), 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juon HS, Fothergill KE, Green KM, Doherty EE, & Ensminger ME (2011). Antecedents and consequences of marijuana use trajectories over the life course in an African American population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118, 216–223. doi: doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DCR, Tiberio SS, & Capaldi DM (2015). Contextual risks linking parents" adolescent marijuana use to offspring onset. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 154, 222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight KE, Menard S, & Simmons SB (2014). Intergenerational continuity of substance use. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(3), 221–233. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.824478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman R, Bailey JA, Guttmannova K, Jones TM, Eisenberg N, Hill KG, & Hawkins JD (2016). Marijuana legalization and parents" attitudes, use, and parenting in Washington State. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(4), 450–456. doi: 10.1016/i.iadohealth.2016.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosty DB, Seeley JR, Farmer RF, Stevens JJ, & Lewinsohn PM (2017). Trajectories of cannabis use disorder: Risk factors, clinical characteristics and outcomes. Addiction, 112(2), 279–287. doi: 10.1111/add.13557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb R, Merikangas KR, Hofler M, Pfister H, Isensee B, & Wittchen HU (2002). Parental alcohol use disorders and alcohol use and disorders in offspring: A community study. Psychological Medicine, 32(1), 63–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughran TA, Larroulet P, & Thornberry TP (2018). Definitional Elasticity in the Measurement of Intergenerational Continuity in Substance Use. Child Development, 89(5), 1625–1641. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J (2016, August 8). One in eight U.S. adults say they smoke marijuana. (Well-being series). Well-being, from http://www.gallup.com/poll/194195/adults-sav-smoke-mariiuana.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Stolar M, Stevens DE, & et al. (1998). Familial transmission of substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55(11), 973–979. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, & Bryk AS (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs NR, Chou C-P, & Pentz MA (2009). Protecting against intergenerational problem behavior: Mediational effects of prevented marijuana use on second-generation parent–child relationships and child impulsivity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 100(1), 153–160. doi: 10.1016/i.drugalcdep.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Merline AC, Johnston LD, O"Malley PM, Bachman JG, & Laetz VB (2005). Trajectories of marijuana use during the transition to adulthood: The big picture based on national panel data. Journal of Drug Issues, 35(2), 255–280. doi: doi: 10.1177/002204260503500203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silins E, Horwood LJ, Patton GC, Fergusson DM, Olsson CA, Hutchinson DM, … Mattick RP (2014). Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: An integrative analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), 286–293. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70307-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suerken CK, Reboussin BA, Egan KL, Sutfin EL, Wagoner KG, Spangler J, & Wolfson M (2016). Marijuana use trajectories and academic outcomes among college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 162, 137–145. doi: 10.1016/i.drugalcdep.2016.02.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland EH (1973). Development of the theory [Private paper published posthumously] In Schuessler K (Ed.), Edwin Sutherland on analyzing crime (pp. 13–29). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry T, Krohn MD, & Freeman-Gallant A (2006). Intergenerational roots of early onset substance use. Journal of Drug Issues, 36(1), 1–28. doi: 10.1177/002204260603600101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vakalahi HF (2001). Adolescent substance use and family-based risk and protective factors: A literature review. Journal of Drug Education, 31(1), 29–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, & Weiss SR (2014). Adverse health effects of marijuana use. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(23), 2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Bechtold J, Loeber R, & Pardini D (2015). Divergent marijuana trajectories among men: Socioeconomic, relationship, and life satisfaction outcomes in the mid-30s. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 156, 62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger A, & Shinar O (2001). Family risk factors and adolescent substance use: Moderation effects for temperament dimensions. Developmental Psychology, 37(3), 283–297. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.3.283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Brook JS, Leukefeld CG, & Brook DW (2016). Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood as predictors of unemployment status in the early forties. The American Journal on Addictions, 25(3), 203–209. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]