Abstract

Evidence on cash transfer interventions for HIV prevention in adolescent girls and young women is unclear and indicates that they may not work uniformly in all settings. Qualitative interviews were conducted with 22 girls and young women post-intervention to determine how a cash transfer study (HPTN 068) in South Africa was perceived to influence sexual behaviours and to explore mechanisms for these changes. Participants described how the intervention motivated them to increase condom use, have fewer partners, end risky relationships and access HIV testing services at local primary health clinics. Changes were attributed to receipt of the cash transfer, in addition to HIV testing and sexual health information. Processes of change included improved communication with partners and increased negotiation power in sexual-decision making. Economic empowerment interventions increase confidence in negotiating behaviours with sexual partners and are complementary to sexual health information and health services that provide young women with a foundation on which to make informed decisions about how to protect themselves.

Keywords: cash transfer intervention, HIV prevention, adolescent girls and young women, empowerment, sexual behaviour

Introduction

Adolescent girls and young women (hereafter referred to as young women) face a disproportionate risk of HIV due to economic and gender inequalities. In rural South Africa, the prevalence of HIV among young women aged 15–24 is 15% compared to 3% in young men of the same age (Gómez-Olivé et al. 2013). Young women are more vulnerable to HIV than men due to gender discrimination, unequal gender norms and lack of access to resources like health services and financial assets (Wojcicki 2005; Levine et al. 2009; Pillay, Manderson and Mkhwanazi 2019). Additionally, social and economic pressures can result in a desire to seek out partnerships with older men and/or transactional sex, and can create power imbalances within relationships that reduce negotiation power in sexual-decision making (Luke 2005; Luke 2003; Evans et al. 2016; Wamoyi et al. 2016; Jennings et al. 2017). Lack of negotiation power can increase young women’s vulnerability to HIV by inhibiting their ability to refuse sex, negotiate safe sex or leave an abusive relationship (Kim et al. 2008; Krishnan et al. 2008; Willan et al. 2019).

Interventions to economically empower young women by giving them control over their own financial resources have been used as a novel way to prevent HIV in this population. In particular, the use of cash transfers to address upstream structural risk factors, such as poverty and access to education, have emerged as one promising economic intervention to prevent HIV (Heise et al. 2013; Pettifor et al. 2012). Cash transfer interventions for HIV prevention are interventions in which young women or their household members receive small transfers of money, either unconditional or conditional on school attendance or other specific behaviors (Pettifor, MacPhail Hughes, et al. 2016; Baird et al. 2012; Heise et al. 2013). The rationale behind these interventions is that increasing economic resources will economically empower young women by giving them independence and control in decision-making, including sexual decision-making, resulting in safer sexual behavior (Ashburn and Warner 2010; Kim et al. 2008; Heise et al. 2013; Pettifor et al. 2012). In addition to direct economic empowerment, conditional cash transfer programmes have been used to incentivise protective behaviors such as school enrollment and attendance, to further reduce the risk of HIV infection (Pettifor et al. 2008; Baird et al. 2010; Pettifor et al. 2012).

The results of observational and randomised studies on the effects of cash transfers on sexual health outcomes in young women have been mixed (Pettifor et al. 2012). A cluster-randomised trial in Malawi found that a cash transfer intervention, both unconditional and conditional on school attendance, reduced the prevalence of HIV in young women of school age (Baird et al. 2012). Young women who received the monthly cash transfer were less likely to have an older partner and were less likely to engage in weekly sex (Baird et al. 2010). Observational data from an unconditional cash transfer programme implemented by the Government of South Africa similarly showed that young women whose families received a cash transfer were less likely to engage in transactional sex or to have an older partner (Cluver et al. 2013). The South African HPTN 068 study, from which our data come, found no effect on incidence of HIV infection of a monthly cash transfer, conditional on school attendance Pettifor, MacPhail, Selin et al. 2016; Pettifor, MacPhail, Hughes et al. 2016).The study did find that young women who received the cash were less likely to have experienced physical violence from a partner, to have had a sex partner in the last 12 months or to have had unprotected sex in the past 3 months. Qualitative data from the study showed access to money was an important factor in developing autonomy and building identity in the young women (MacPhail et al. 2018).

Overall, the evidence on the effect of cash transfers for HIV prevention behaviours in young women is unclear and indicates that cash transfers may not work in the same way in all settings. Additionally, there is increasing evidence from initiatives like DREAMS1 for multi-pronged approaches that combine cash transfers with other interventions to increase effectiveness (Fleischman and Peck 2015). In-depth, qualitative research can help us to understand the mechanisms by which cash transfers work to influence sexual behaviors and may help to explain the differential effects of these programmes across populations. In this article, we use semi-structured interview data from the HPTN 068 study collected post-intervention to determine how the cash transfer intervention, and components of the study participation process - HIV testing and sexual health information - operated to influence sexual behavior. Specifically, we seek to determine how young women perceived that the study intervention components and related activities affected their relationship choices and sexual behaviours including condom use, partner type, transactional sex, number of partners, intimate partner violence and concurrent relationships. We then explore mechanisms through which the program operated to change these behaviours.

Materials and Methods

Study Context

The Swa Koteka study, or HPTN 068, was a phase 3, randomised controlled trial conducted in the Bushbuckridge subdistrict of the Mpumalanga province of South Africa (2011–2015). The study was conducted within the Agincourt Health and Socio-Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) run by the South African Medical Research Council and University of the Witwatersrand Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit.(Kahn et al. 2012) The area is rural with poor infrastructure and is characterised by high levels of unemployment, poverty, migration for work and financial reliance on social grants from the government (80% receiving the Child Support Grant) (Kahn et al. 2007; Kahn et al. 2012; MacPhail et al. 2018; Pettifor, MacPhail, Selin et al. 2016). In 2011, the prevalence of HIV in young women aged 15–19 years was 5.5%, rising to 27% in young women age 20–24 and peaking at age 35–39 (46.1%) (Gómez-Olivé et al. 2013).

Description of Intervention

The Swa Koteka intervention provided a monthly cash transfer to young women and their households, conditional on attending 80% or more of school days (Pettifor, MacPhail, Selin et al. 2016; Pettifor, MacPhail, Hughes et al. 2016). Participants were selected from a sample of young women aged 13–20 years enrolled in schools within the Agincourt HDSS and randomised 1 to 1 to the cash transfer intervention arm or to the control arm, which did not receive any payment. Participants in the intervention arm received a total monthly payment of 300 South African Rand (ZAR100 to young women themselves and ZAR200 to their parent or guardian – approximately US $10 and US $20, respectively) if they met the attendance requirement.

As part of the study participation process, all young women also attended an annual weekend “camp” with other study participants where they completed annual survey procedures, regardless of study arm. The camps lasted 4–5 hours while the young women visited different stations to complete each study procedure. Study procedures included: a self-reported interview, group pre-test counseling for HIV and Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 (HSV-2), a venous blood draw for HIV and HSV-2, and individual post-test counselling. The study participants did not receive any formal educational sessions but did receive the pre- and post-test counselling sessions, which we later describe as an “informational component.” In addition, they received written materials on HSV-2, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), violence, and HIV prevention. A total of 2,533 young women were enrolled in the HPTN 068 trial. The descriptions of the young women vary in the Results section below because they are based on key characteristics that the girls chose to report about their relationships, which varied by interview.

Qualitative sample

Twenty-two young women from the intervention arm who received the cash transfer and participated in a quantitative post-intervention visit two years after study completion were selected for an individual in-depth interview. We only included young women in the intervention group because we were interested in how the intervention operated to change behaviour. Young women were purposively selected to capture different numbers of partners (at least one, or 2 or more) and the timing of the reported partnerships relative to the intervention. The cash transfer did decrease the risk of reporting any sex partner in the last 12 months (Pettifor, MacPhail, Hughes et al. 2016).. This sampling strategy was conceived to ensure variation in participants’ experiences in their relationships and sexual behavior change. The categories were not constructed for the purpose of making comparisons within or between groups but to have a representative sample to discuss sexual behaviors within previous relationships. The interviewers were blind to all groups and first called to screen if each participant was willing to talk about her sexual relationships in relation to the cash transfer intervention. Interviews were then conducted at the participant’s home. No participants refused an interview.

Data Collection

We sought to understand the impact of the cash transfers on romantic relationships and sexual decision-making in the qualitative interviews. All interviews were conducted by trained female research staff who were from the research communities and native xiTsonga speakers. Interviews were digitally recorded and were translated and transcribed simultaneously to English. Individual written informed consent was completed prior to the interviews. Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide covering a range of questions about the cash transfer and young women’s romantic relationships. Information about other study activities was unprompted. The participants were first asked to describe each of the relationships they had during the intervention period. Questions about each partner included general questions about the nature of that partnership including sexual behaviours and how these behaviours were affected by the SK cash transfer intervention. Specific questions about Swa Koteka included how the intervention affected 1) financial support, 2) decisions around sex and selection of partners, 3) trust, 4) communication, 5) partner type, 6) HIV prevention and 7) pregnancy prevention. Participants were asked directly about their experiences with and perceived effects of the cash transfer but not about other study procedures including (HIV testing and counseling. If study procedures were mentioned, they were brought up by the participants while talking about how Swa Koteka affected their lives.

Qualitative analysis

The goal of our analysis was to determine how young women perceived that the study and its associated activities affected their relationship choices and sexual behaviour including condom use, partner type, transactional sex, number of partners, experience of intimate partner violence and concurrent relationships. Second, we explored mechanisms through which the programme operated to change these behaviors. All transcripts were coded by a single coder in Atlas.ti version 8 (Scientific Softward Development GmbH 2019) using a coding frame with codes reflecting both a priori topics and research questions guiding the study aims, and codes within these topics that emerged from interviews over the course of the analysis (Tolley et al. 2016). A priori codes included the following topics: 1) components of the intervention that were mentioned in relation to behaviour (e.g. cash transfer, HIV testing, sexual behavior and camps); 2) characteristics of each romantic relationship; 3) the effect of the intervention on sexual behaviour; and 4) other effects of the intervention not specific to sexual behaviour (e.g. trust, communication, financial).

Participants were only asked about the cash transfer, although we did include other components of the intervention as a priori codes. We coded discussion of sexual behaviours including condom use, change in partner type, transactional sex, older partner, abuse, casual partner, concurrency and pregnancy prevention. We later added a code for partner migration since during the process of analysis we realised the importance of partner mobility on the behaviours of interest. We examined all codes related to sexual behaviour and then looked at co-occurrence of these codes with codes for components of Swa Koteka (Tolley et al. 2016). We investigated codes that co-occurred at least 3 times. Using these observations of co-occurrence to identify potentially salient relationships between the influence of the intervention and women’s sexual decision-making, we reviewed the relevant narratives and used a by-participant matrix to document the way in which each participant described the connection between each intervention component and sexual decision making. Reviewing these matrices, we summarised the perceived impact of each component of the programme on sexual behaviour and relationship choices across participants. We assigned pseudonyms to all participants to protect confidentiality.

Results

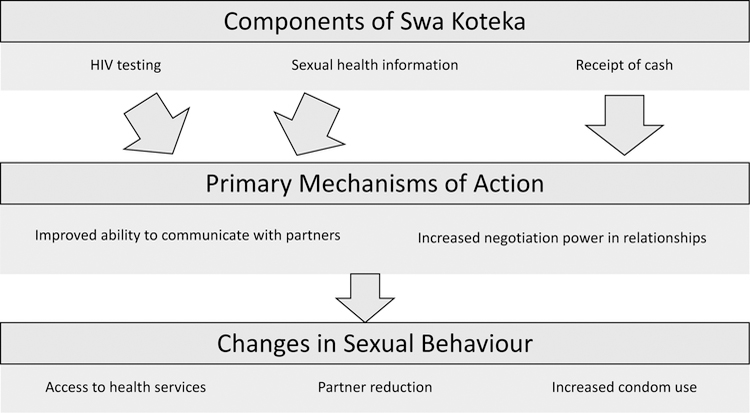

Participants were aged 13–20 years at enrollment in the original trial and their mean age at the post intervention visit for the quantitative survey (when the qualitative interview was also conducted) was 20 (range 17–26). During the qualitative interview, the majority of girls reported one to three partners with a maximum of five. While participants were only asked directly about receipt of the cash transfer intervention, many young women also discussed the impact of the study participation process - HIV testing and information- on sexual behaviour (Figure 1). We begin by presenting women’s’ perceptions of the effect of each of these components of Swa Koteka on their sexual behaviors and relationship choices. Women believed that participating in Swa Koteka had affected their ability to end relationships, desire to access health services, engagement in transactional sex, condom use, partner concurrency and number of partners.

Figure 1:

Intervention processes of influence emerging from participants’ narratives.

Perceived impact of each component of the intervention on sexual behaviour

Receipt of Cash

Most participants in the qualitative interviews mentioned that the cash transfer intervention was the primary benefit of study participation which had an impact on their relationship choices and sexual behaviors. The other participants stated that the cash alone did not have a substantial effect on their behaviour. While almost all of the participants said they received some form of gifts or financial support from their partners during the study (not necessarily in relation to sex, n=20), many participants stated that the cash made them feel less reliant on their partners to provide for them. This was exemplified by Constance (22 years) who had two previous relationships that both ended with the partner cheating said: “I was no longer demanding a lot from them [male partners] because I knew that I have my own money when I need something I was able to do it.” Zanele (19 year) who had a current, long-term partner described how she used the cash from the intervention to pay for transportation to go to the clinic: “I can say it has helped me because I was using it to take ride for taxi when I go for pregnancy prevention in the clinic and to introduce condoms to my boyfriend.” Overall, the cash increased girls’ resources by allowing them to be less dependent on their partners.

The cash was commonly mentioned around decision-making about ending relationships that were not desirable and being able to demand condom use from partners. For example, one 20-year old participant described how the cash influenced her condom use by saying “now I’m able to approach him [her partner] when it comes to HIV prevention.” Sana (19 years) described how she broke up with her abusive boyfriend during the study: “I was scared of him because I was unable to say anything to him but since I was having my own money I have started saying that I don’t like what you are doing.” Similarly, Enelo (22 years) who had one prior relationship and one current relationship decided to break up her most first partner after he refused to use a condom:

It has changed because I decided to breakup with my boyfriend since he refuses to use the condom neh… and I cannot beg him for nothing. I cannot beg him to give me something by having sex without a condom no… jaa, the cash has changed me on that.

Two young women specifically mentioned that the cash transfer reduced their likelihood of having sex with a partner. Enelo (22 years) described how she also stopped having sex with her first partner for money saying:

Like maybe I don’t get Swa Koteka money I would push myself to have sex with him even when he refused to use the condom because he gave me money. So, I didn’t see any use of pushing myself to have sex with him because the Swa Koteka money was helping me.

More commonly, the young women mentioned that cash made them less dependent on partners but that it did not directly change their desire to have sex with a partner. For example, Blessing (19 years) with a long-term partner with whom she has a child said, “I was not demanding money to braid my hair from him, because I was getting money from the study.” But when asked if the cash affected her sexual behaviors she said “money didn’t change me, or cannot influence me to have sex with a man… I have sex with my boyfriend because I love him.”

Sexual Health Information

Almost all participants mentioned learning more about HIV and HSV-2 infection as a key piece of information they obtained from pre- and post-test counseling in the study. The young women stated that this information was comprehensive and often the first time they had learned about prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). This was exemplified by Nkosi (22) who had one steady, long-term partner and a child who said, “the information on how to get infected by diseases, like STI and HIV, it was helpful for me because it was the first time to get this information.” The participants described how they often received incomplete or vague information at school and the information from Swa Koteka was more detailed. Specifically, several participants said that they were happy to learn about HSV-2 infection and would otherwise never have known about this STI.

The behaviours most commonly mentioned as having been affected by the sexual health information were number of sexual partners, concurrent relationships and condom use. Young women were more knowledgeable about how to prevent STIs and therefore better able to incorporate safer behaviours into their own lives. This was exemplified by Violet (21 years) who broke up with a concurrent partner and stated that in relation to information in the study: “there was a great change in my life because I started to know about condoms and even to change my sexual behavior so that I must stick to one sexual partner.” Several participants said they had started using condoms because they were more educated about sexual risk. For example, Tengisa (22) said “I started practising what I learned in the study… like to use condoms when I have sex with my partner.” Mbhuri (22 years) describes the change she saw in the study participants as a whole:

I can say most of the youth that were part of the study previously were not caring about condom use when they are with their boyfriend, but after we started to get information about that, that’s where the study has opened our eyes. I was interested in the information that the study was giving us because even myself I have started to know that I have to follow what they taught us.

HIV Testing

HIV testing was another component of Swa Koketa mentioned by 18 participants in relation to changes in sexual behavior. Many young women shared that without the study, they would not have felt comfortable with the HIV testing process. Zanele (19 years) said, “As youth we grow up with fearfulness of going to the clinic for HIV testing because people will talk about me if I tested positive but Swa Koteka has removed that fearfulness.” HIV testing was primarily mentioned as decreasing fear of HIV testing and increasing motivation to visit a local health clinic once the study had ended.

In addition to increased comfort with HIV testing, the young women described how HIV testing made them feel less fearful about having a positive result and more educated about what it means to be HIV positive. Khensani (20 years) said

… if they find you with HIV, they were giving counseling until you accept it, it’s not the end of the world, you can still live life like other people without HIV. The only difference can be a virus which is living in your body which needs you to take treatment.

The HIV testing component of study participation was mentioned almost exclusively in connection to an increased desire and confidence to access testing services at local public health clinics in the future, including venues that were not associated with the study. Women attributed this change to familiarity with testing gained during the study. As said Enelo (22 years) : “I was no longer scared to go to the clinic to test for HIV and not relying on Swa Koteka only, they were encouraging us to go and test in the clinic after each and every month.” Familiarity with HIV testing made young women feel more comfortable, allowing them to take the initiative to get tested on their own in spite of other barriers they might still face in receiving HIV testing at local clinics.

Perceived mechanisms of change in program impact on sexual relationships and behaviour

There were a number of mechanisms by which women explained that each component of Swa Koteka had affected their behaviour and relationship decisions. Broadly, women spoke of empowerment by the programme, with specific empowering mechanisms of change including: 1) improved communication with partners, and 2) enhanced ability to exercise power in decision-making about sexual behaviour.

Improved ability to communicate to partners

Several young women said that they shared information with their partners about HIV testing in the study and encouraged their partners to also get tested. For example, Blessing (19 years)with a current long-term partner said, “He went to the clinic and did HIV testing because I shared the information that I learned in the study with him.” HIV testing in the study acted as leverage for young women to encourage their partners to test. Several girls said that HIV testing improved trust within their relationships once their partners were tested. HIV testing improved young women’s confidence about communicating with partners by sharing HIV prevention information and suggesting their partners get tested themselves.

The informational component of the intervention was also mentioned in relation to improved communication with partners. Solani (21 years) stated that she and her long-term partner began to communicate more about HIV prevention because “I have learned to talk about it because Wits [who ran the Swa Koteka intervention] also provides you with the pamphlets that you can get more information.” In relation to the study as a whole, Zanele (19-years) had two long-terms partners said, “I would not be able to talk about HIV [with my boyfriend] if I had not participated in the study.” The sexual health information and HIV testing allowed participants to feel more able and comfortable talking about HIV and HSV-2 risk and how to prevent infection with their partners.

Increased negotiation power in relationships

Power in relationships was repeatedly mentioned in relation to the receipt of cash and changes in behaviour. Having their own cash made the young women feel less reliant on their partners and more likely to assert their own opinions in the relationship. Enelo (22 years), who stood behind her beliefs about condom use and eventually ended her relationship, attributed these changes to power dynamics within the relationship. She said that the cash transfer changed her sexual relationship by increasing her power, stating:

The money has changed my decisions since I said I told my boyfriend that we must use protection and he refused maybe he will push me to have sex with him because he knew that he is giving me money. You see something like that he will oppress me because of his money but since I was having my own money, it made me say f**k off you can stay with your money I have my own money to carry at school.

Several other participants also mentioned that having cash increased their power to negotiate within relationships and to feel more confident overall. Zanele (19 years) who had a prior relationship that was abusive said “I can say the money has helped me because I have started to think that I must not date someone who will have a say in my life more than me or who will control me without me saying anything.” A common phrase was feeling better ‘able to take care of myself’ or ‘to stand for myself as a young woman.’ Solani (21 years) summarised her experience in the study by saying:

I have to do my own things or to be independent not depending on other people because to follow other people leads you somewhere you don’t expect yourself to be. I think maybe if I did not enroll at Wits [with the Swa Koteka study] maybe I will be having children, so it has helped me.

Participants commonly mentioned that sexual health information and HIV testing made them feel able to “take care of themselves” and their health and that financial support made them be able to” stand on their own” with their partners. The cash transfer and other studies activities were complementary to one another where the cash transfer gave young women more control over their ability to negotiate with partners and the other study activities allowed them to understand which specific changes to implement in their relationships.

Discussion

We found that young women participating in Swa Koteka perceived that the intervention had encouraged them to increase condom use, have fewer partners, enabled them to end risky relationships, and motivated them to access HIV testing services at the local public health clinics. Young women attributed these changes to the improved communication with partners supported by all components of the intervention (testing, information, cash) and increased negotiation power in sexual-decision making that was supported by the financial independence afforded to them by the cash transfers.

Participants in the qualitative interviews commonly mentioned changes in sexual behaviors within relationships but rarely discussed effects on partner selection (e.g. partner age or transactional nature of relationship). These findings are consistent with findings from another qualitative investigation undertaken as part of the HPTN 068 cash transfer study showing that transactional sex was often motivated by love or social status, rather than basic needs (Ranganathan et al. 2018). Quantitative findings from the HPTN 068 main trial found similar results with impacts on having a sex partner in the last 12 months and unprotected sex in the past 3 months, but not transactional sex or age-disparate partnerships ( Stoner et al. 2017; Stoner et al. 2018; Pettifor, MacPhail, Hughes et al. 2016). A qualitative study exploring men’s perceptions of the impact of the HPTN 068 cash transfer intervention on male-female relationships found that younger peers were concerned that the cash diminished their power and status in relationships because they provided smaller amounts of money that were offset by the cash (Khoza et al. 2018). In contrast, the cash did not change young women’s financial power in relationships with older, intimate partners because these partners provided larger amounts of money. Older partners perceived that gendered roles could have changed if the amount of the cash transfer was larger.

HIV testing and sexual health information were complementary to the cash transfer intervention. Young women perceived the HIV testing and sexual health information to have improved their knowledge of STI prevention allowing them to better able to take care of themselves and their health. These sentiments were complementary to perceptions that the cash gave young women the freedom from depending on others and to “stand on their own.” These two factors interacted with one another where young women felt more confident about asserting their opinions but also more knowledgeable about how they wanted to incorporate STI prevention into their own lives. For example, several participants said they changed their behaviour within sexual relationships including by using a condom, encouraging a partner to test, or remaining monogamous. Young women who were not able to enact change in relationships talked about leaving those relationships. Results show that each component of the intervention influenced behaviour and illustrate how they were working together to affect behaviour whether or not they were intended to do so. Economic empowerment increased agency and ability to negotiate behaviors but a strong foundation about sexual health also allowed young women to feel confident about which behaviour to adopt to protect themselves in the context of their own relationships. The study was not intended to be an educational or skills buildings information but by the time of the post- intervention interview, young women had been in the study for 3–4 years and tested each year. Our results are similar to another structural cash intervention in Tanzania which showed that cash incentives and the testing component worked synergistically to assist men and women with opportunities to better enact behavioural change in their relationships (Packel et al. 2012).

Our findings align with that theory that economic empowerment through cash transfers can lead to behavior change (Kim et al. 2008; Ashburn and Warner 2010; Heise et al. 2013; Pettifor et al. 2012). Kabeer (1999) states that empowerment can be thought of as a process “by which those who have been denied the ability to make strategic life choices acquire such an ability” Kabeer proposes that an individual’s ability to exercise choice is determined by three interconnected dimensions: resources, agency and outcomes. Resources include material, human and social resources that enhance one’s ability to exercise choice. In the case of our study, resources could refer to the three components of the intervention (receipt of cash, HIV testing and sexual health information) that young women believed had improved their communication and negotiation power in relationships (agency) to influence outcomes.

Although the study visit activities included testing and counselling components, the cash payments were the main resource provided by the intervention, allocated monthly, compared to yearly for the other study activities. Jennings et al. (2017) demonstrated even before receiving the transfers that young women with greater economic resources were more likely to engage in safer sexual behaviour that could protect against HIV such as periodic sexual abstinence and condom use (Jennings et al. 2017). Studies in other comparable resource-poor settings have also demonstrated that economic factors play a crucial role in sexual decision-making of young people (Ssewamala et al. 2010; Jennings et al. 2017; Luke 2005). It is therefore not surprising that we find that the cash and the economic security it provided was described by young women as having an influence on some of their sexual behaviors. Although, we did not see a direct impact on transactional sex.

Similar to our results here, findings from previous studies have shown that interventions that improve the economic opportunities available to poor young women can result in positive impacts on protective behaviors and the sense of empowerment of participants. For instance, qualitative and quantitative findings from a cash transfer programme for young women in Malawi found improvements in sexual and relationship empowerment of the participants (Baird, Chirwa and Mcintosh 2010; Baird et al. 2013; Baird et al. 2012.) In particular, the intervention led to increased schooling and reduced HIV prevalence when combining the unconditional and conditional arms, (Baird, Chirwa and Mcintosh 2010; Baird et al. 2012). However, these effects were not sustained after the study ended (Baird, Mcintosh and Ozler 2016).

In addition to the cash transfer intervention, young women perceived sexual health information and HIV testing through study participation to be an important resource. Although, counselling sessions only occurred in the study camps once a year, HIV testing and sexual health information were overwhelmingly mentioned as influencing behaviour. HIV testing and sexual health information were perceived as otherwise inaccessible or not as comprehensive without participation in Swa Koteka, highlighting the need for more programmes focused on these areas. In a qualitative study of the partners of young women who were participants in the main HPTN 068 study, men also mentioned improved communication about sex and HIV in intimate relationships, with some women encouraging their partners to go for an HIV test. Additionally, services were provided by staff that were trained in youth friendly health services and these staff continued to see the participants and build relationships over the course of the study. The training and experience of staff may have contributed to perceptions about STI testing and pre and post-test counselling.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we relied on self-reported information which may be subject to social desirability bias. In particular, all the young women were enrolled in the cash transfer arm and may have been felt pressure to report positive changes through the intervention. Second, interviews were translated and transcribed by trained interviewers. It is possible that the content of the interviews changed or lost meaning during the transcription and the translation process. However, most interviewers were fluent in both languages and rechecked transcripts. Lastly, we had only one coder due to resource constraints.

Conclusion

There is a growing acknowledgement that programmes and interventions for HIV prevention in young women should combine structural, behavioural and biomedical components and should be tailored to context (Pettifor et al. 2013; Coates, Richter and Caceres 2008). Our findings support cash transfer interventions currently in the field that are pairing cash transfers with sexual health information and economic empowerment training. In our study population, most young women mentioned financial support from partners but also that they were seeking love in these relationships. In such situations, a comprehensive programme might be beneficial to give young women the information needed to negotiate and implement changes in behaviour. Overall, economic empowerment interventions could benefit from the addition of information on sexual health and health services that provide young women with a foundation on which to make informed decisions about how to best protect themselves, in addition to increased confidence negotiating behaviours with sexual partners.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the participants in these qualitative interviews as well as all the HPTN 068 participants and the study team.

Funding

This study was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (R01 MH110186, R01MH087118) and by award numbers UM1 AI068619 (HPTN Leadership and Operations Center), UM1AI068617 (HPTN Statistical and Data Management Center), and UM1AI068613 (HPTN Laboratory Center) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the US National Institutes of Health. The work was also supported by the Carolina Population Center and its US NIH Center grant (P2C HD050924). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Lauren Hill’s salary was supported by a National Research Service Award Post-Doctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality sponsored by The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Grant No. T32-HS0.

Footnotes

DREAMS is a large scale programme funded by the US government to reduce HIV incidence in adolescent girls and young women in 10 countries worldwide. More information can be access here: https://www.pepfar.gov/partnerships/ppp/dreams/

Declaration of Interest Statement

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Ashburn Kim, and Warner Ann. 2010. “Can Economic Empowerment Reduce Vulnerability of Girls and Young Women to HIV?” Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women. [Google Scholar]

- Baird Sarah, Chirwa Ephraim, McIntosh Craig, and Ozler Berk. 2010. “The Short-Term Impacts of a Schooling Conditional Cash Transfer Program on the Sexual Behavior of Young Women.” Health Economics 19 Suppl: 55–68. 10.1002/hec.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird Sarah J., Garfein Richard S., McIntosh Craig T., and Özler Berk. 2012. “Effect of a Cash Transfer Programme for Schooling on Prevalence of HIV and Herpes Simplex Type 2 in Malawi: A Cluster Randomised Trial.” The Lancet 379 (9823): 1320–29. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird Sarah J., Chirwa Ephraim, De Hopp Jacobus, and Özler Berk. 2013. “Girl Power: Cash Transfers and Adolescent Welfare. Evidence from a Cluster-Randomied Experience in Malawi.” 19479 NBER Working Paper; Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Baird Sarah Jane, Mcintosh Craig, and Ozler Berk. 2016. “When the Money Runs out : Do Cash Transfers Have Sustained Effects on Human Capital Accumulation?” The World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper Series: 7901. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/495551480602000373/pdf/WPS7 901.pdf.

- Cluver Lucie, Boyes Mark, Orkin Mark, Pantelic Marija, Molwena Thembela, and Sherr Lorraine. 2013. “Child-Focused State Cash Transfers and Adolescent Risk of HIV Infection in South Africa: A Propensity-Score-Matched Case-Control Study.” The Lancet Global Health 1 (6): 362–370. 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates Thomas J, Richter Linda, and Caceres Carlos. 2008. “Behavioural Strategies to Reduce HIV Transmission: How to Make Them Work Better.” Lancet 372 (9639): 669–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans Meredith, Risher Kathryn, Zungu Nompumelelo, Shisana Olive, Moyo Sizulu, Celentano David D., Maughan-Brown Brendan, and Rehle Thomas M.. 2016. “Age-Disparate Sex and HIV Risk for Young Women from 2002 to 2012 in South Africa” Journal of the International AIDS Society 19 (1): 21310 10.7448/IAS.19.1.21310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischman Janet, and Peck Katherine. 2015. “Addressing HIV Risk in Adolescent Girls and Young Women.” Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Olivé Francesc Xavier, Angotti Nicole, Houle Brian, Kerstin Klipstein-Grobusch Chodziwadziwa Kabudula, Menken Jane, Williams Jill, Tollman Stephen, and Clark Samuel J. 2013. “Prevalence of HIV among Those 15 and Older in Rural South Africa.” AIDS Care 25 (9): 1122–28. 10.1080/09540121.2012.750710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise Lori, Lutz Brian, Ranganathan Meghna, and Watts Charlotte. 2013. “Cash Transfers for HIV Prevention: Considering Their Potential.” Journal of the International AIDS Society (16): 18615 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings Larissa, Pettifor Audrey, Hamilton Erica, Ritchwood Tiarney D., Gómez-olivé F. Xavier, MacPhail Catherine, Hughes James, Selin Amanda, Kahn Kathleen, and The HPTN 068 Study Team. 2017. “Economic Resources and HIV Preventive Behaviors Among School-Enrolled Young Women in Rural South Africa (HPTN 068).” AIDS & Behavior 21 (3): 665–77. 10.1007/s10461-016-1435-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer Naila. 1999. “Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment.” Development and Change. 10.1111/1467-7660.00125. [DOI]

- Kahn Kathleen, Collinson Mark A., Gómez-olivé F. Xavier, Mokoena Obed, Twine Rhian, Mee Paul, Afolabi Sulaimon A., et al. 2012. “Profile: Agincourt Health and Socio-Demographic Surveillance System.” International Journal of Epidemiology 41 (4): 988–1001. 10.1093/ije/dys115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn Kathleen, Tollman Stephen M., Collinson Mark A., Clark Samuel J., Twine Rhian, Clark Benjamin D., Shabangu Mildred, Gómez-Olivé Francesc Xavier, Mokoena Obed, and Garenne Michel L.. 2007. “Research into Health, Population and Social Transitions in Rural South Africa: Data and Methods of the Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance System1.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 35 (69 suppl): 8–20. 10.1080/14034950701505031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoza Makhosazane Nomhle, Sinead Delany-Moretlwe, Scorgie Fiona, Hove Jennifer, Selin Amanda, Imrie John, Twine Rhian, Kahn Kathleen, Pettifor Audrey, and Catherine MacPhail. 2018. “Men’s Perspectives on the Impact of Female-Directed Cash Transfers on Gender Relations: Findings from the HPTN 068 Qualitative Study.” PloS One 13 (11): e0207654 10.1371/journal.pone.0207654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Julia, Pronyk Paul, Barnett Tony, and Watts Charlotte. 2008. “Exploring the Role of Economic Empowerment in HIV Prevention.” AIDS 22 (suppl 4): S57–S71 10.1097/01.aids.0000341777.78876.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan Suneeta, Dunbar Megan S., Minnis Alexandra M., Medlin Carol A., Gerdts Caitlin E., and Padian Nancy S.. 2008. “Poverty, Gender Inequities, and Women’s Risk of Human Immunodeficiency Virus/AIDS.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1136: 101–110. 10.1196/annals.1425.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine Ruth, Lloyd Cynthia, Greene Margaret, and Grown Caren. 2009. “Girls Count a Global Investment & Action Agenda.” Center for Global Development.” Washington, D.C: The Center for Global Development. [Google Scholar]

- Luke Nancy. 2003. “Age and Economic Asymmetries in the Sexual Relationships of Adolescent Girls in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Studies in Family Planning 34 (2): 67–86. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke Nancy. 2005. “Confronting the ‘sugar Daddy’ Stereotype: Age and Economic Asymmetries and Risky Sexual Behavior in Urban Kenya.” International Family Planning Perspectives 31 (1): 6–14. 10.1363/3100605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhail Catherine, Khoza Nomhle, Selin Amanda, Julien Aimée, Twine Rhian, Wagner Ryan G., Goméz-Olivé Xavier, Kahn Kathy, Wang Jing, and Pettifor Audrey. 2018. “Cash Transfers for HIV Prevention: What Do Young Women Spend It on? Mixed Methods Findings from HPTN 068.” BMC Public Health 18 (1): 10 10.1186/s12889-017-4513-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packel Laura, Keller Ann, Dow William H., de Walque Damien, Nathan Rose, and Mtenga Sally. 2012. “Evolving Strategies, Opportunistic Implementation: HIV Risk Reduction in Tanzania in the Context of an Incentive-Based HIV Prevention Intervention.” PLoS ONE. 7(8): e44058 10.1371/journal.pone.0044058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor Audrey, Bekker Linda-Gail, Hosek Sybil, DiClemente Ralph, Rosenberg Molly, Bull Sheana S., Allison Susannah, Delany-Moretlwe Sinead, Kapogiannis Bill G., and Cowan Frances. 2013. “Preventing HIV among Young People: Research Priorities for the Future.” Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 63 (Suppl 2): S155–60. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829871fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor Audrey E., Levandowski Brooke A., Macphail Catherine, Padian Nancy S., Cohen Myron S., and Rees Helen V.. 2008. “Keep Them in School: The Importance of Education as a Protective Factor against HIV Infection among Young South African Women.” International Journal of Epidemiology 37 (6): 1266–73. 10.1093/ije/dyn131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor Audrey, MacPhail Catherine, Hughes James P, Selin Amanda, Wang Jing, Gómez-Olivé F Xavier, Eshleman Susan H, et al. 2016. “The Effect of a Conditional Cash Transfer on HIV Incidence in Young Women in Rural South Africa (HPTN 068): A Phase 3, Randomised Controlled Trial.” The Lancet Global Health 4 (12): e978– e988 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor Audrey, MacPhail Catherine, Nguyen Nadia, and Rosenberg Molly. 2012. “Can Money Prevent the Spread of HIV? A Review of Cash Payments for HIV Prevention.” AIDS & Behavior 16 (7): 1729–38 10.1007/s10461-012-0240-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor Audrey, Catherine MacPhail Amanda Selin, Gómez-Olivé F. Xavier, Rosenberg Molly, Wagner Ryan G., Mabuza Wonderful, et al. 2016. “HPTN 068: A Randomized Control Trial of a Conditional Cash Transfer to Reduce HIV Infection in Young Women in South Africa: Study Design and Baseline Results.” AIDS & Behavior 20 (9): 1863–82. 10.1007/s10461-015-1270-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay Nirvana, Manderson Lenore, and Mkhwanazi Nolwazi. 2019. “Conflict and Care in Sexual and Reproductive Health Services for Young Mothers in Urban South Africa.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 1–15. 10.1080/13691058.2019.1606282 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ranganathan Meghna, Heise Lori, MacPhail Catherine, Stöckl Heidi, Silverwood Richard J., Kahn Kathleen, Selin Amanda, Gómez-Olivé F. Xavier, Watts Charlotte, and Pettifor Audrey. 2018. “‘It’s Because i like Things... It’s a Status and He Buys Me Airtime’: Exploring the Role of Transactional Sex in Young Women’s Consumption Patterns in Rural South Africa (Secondary Findings from HPTN 068).” Reproductive Health 15:102 10.1186/s12978-018-0539-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Softward Development GmbH. 2019. “Atlas.ti 8 Windows User Manual.” Berlin, Germany: Retrived from: http://downloads.atlasti.com/docs/manual/atlasti_v8_manual_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala Fred, Ismayilova Leyla, McKay Mary, Sperber Elizabeth, Bannon William Jr, and Alicea Stacey. 2010. “Gender and the Effects of an Economic Empowerment Program on Attitudes Toward Sexual Risk-Taking Among AIDS-Orphaned Adolescent Youth in Uganda.” Journal of Adolescent Health 46 (4): 372–78. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner MCD, Pettifor A, Edwards JK, Aiello AE, Halpern CT, Julien A, Selin A, et al. 2017. “The Effect of School Attendance and School Dropout on Incident HIV and HSV-2 among Young Women in Rural South Africa Enrolled in HPTN 068.” AIDS 31 (15): 2127–2134. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner Marie CD, Pettifor Audrey, Eduwards Jessie K., Miller William C., Aiello Allison E., Halpern Carolyn T., Julien Aimée J, et al. 2018. “Does Partner Selection Mediate the Relationship between School Attendance and HIV/HSV-2 among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in South Africa: An Analysis of HPTN 068 Data.” JAIDS 79 (10): 20–27. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolley Elizabeth E., Ulin Priscilla R., Mack Natasha, Robinson Elizabeth T., and Succop Stacey M.. 2016. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. San Fransisco, CA: : Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Wamoyi Joyce, Stobeanau Kirsten, Bobrova Natalia, Abramsky Tanya, and Watts Charlotte. 2016. “Transactional Sex and Risk for HIV Infection in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of the International AIDS Society 19 (1): 20992 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willan Samantha, Ntini Nolwazi, Gibbs Andrew, and Jewkes Rachel. 2019. “Exploring Young Women’s Constructions of Love and Strategies to Navigate Violent Relationships in South African Informal Settlements.” Culture, Health & Sexuality, 10.1080/13691058.2018.1554189. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wojcicki Janet Maia. 2005. “Socioeconomic Status as a Risk Factor for HIV Infection in Women in East, Central and Southern Africa: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Biosocial Science 37 (1): 1–36. 10.1017/S0021932004006534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]