Abstract

BACKGROUND

Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN) is a rare entity with multifactorial etiology, usually presenting with signs of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

AIM

To systematically review all available data on demographics, clinical features, outcomes and management of this medical condition.

METHODS

A systematic literature search was performed with respect to the PRISMA statement (end-of-search date: October 24, 2018). Data on the study design, interventions, participants and outcomes were extracted by two independent reviewers.

RESULTS

Seventy-nine studies were included in this review. Overall, 114 patients with AEN were identified, of whom 83 were males and 31 females. Mean patient age was 62.1 ± 16.1. The most common presenting symptoms were melena, hematemesis or other manifestations of gastric bleeding (85%). The lower esophagus was most commonly involved (92.9%). The most widely implemented treatment modality was conservative treatment (75.4%), while surgical or endoscopic intervention was required in 24.6% of the cases. Mean overall follow-up was 66.2 ± 101.8 d. Overall 29.9% of patients died either during the initial hospital stay or during the follow-up period. Gastrointestinal symptoms on presentation [Odds ratio 3.50 (1.09-11.30), P = 0.03] and need for surgical or endoscopic treatment [surgical: Odds ratio 1.25 (1.03-1.51), P = 0.02; endoscopic: Odds ratio 1.4 (1.17-1.66), P < 0.01] were associated with increased odds of complications. A sub-analysis separating early versus late cases (after 2006) revealed a significantly increased frequency of surgical or endoscopic intervention (9.7 % vs 30.1% respectively, P = 0.04)

CONCLUSION

AEN is a rare condition with controversial pathogenesis and unclear optimal management. Although the frequency of surgical and endoscopic intervention has increased in recent years, outcomes have remained the same. Therefore, further research work is needed to better understand how to best treat this potentially lethal disease.

Keywords: Acute esophageal necrosis, Black esophagus, Acute necrotizing esophagitis

Core tip: This manuscript’s aim was to systematically review and synthesize all available data on demographics, clinical features, outcomes and the management of acute esophageal necrosis. According to our results, acute esophageal necrosis is a rare condition with controversial pathogenesis and unclear optimal management. Although the frequency of surgical and endoscopic intervention has increased in recent years, outcomes have remained the same. Therefore, further investigations are needed to better understand how to best treat this potentially lethal disease.

INTRODUCTION

Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN), also known as acute necrotizing esophagitis (ANE) or black esophagus is a rare and potentially devastating medical condition. Diagnosis is typically made with upper endoscopy. The most common endoscopic finding is a striking diffuse circumferential black discoloration of the esophageal mucosa which is associated with histologic evidence of extensive mucosal necrosis. The pathogenesis of AEN appears to be multifactorial. That said, ischemia has been reported as the most common etiology[1,2]. Gastric outlet obstruction with massive reflux of gastric secretions, viral infection, hypersensitivity to antibiotics, hypothermia, and corrosive trauma can also lead to AEN[1,3]. Typically, patients present at the emergency room with signs of upper gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage such as coffee-ground emesis, melena or hematemesis[4]. Conservative management with adequate hydration, proton pump inhibitors, antibiotics, acid suppression or sucralfate suspension administration is employed either as definitive or first-line treatment depending on disease severity[4]. Emergency surgical intervention followed by patient support until clinical stabilization can also be considered in case of necrosis and perforation[5].

Given the rarity of AEN, our experience with this condition is primarily based on case reports and small case series. To better understand the demographics, clinical features, and outcomes of this uncommon esophageal disease, we performed a systematic review of literature published within the period 1990 to 2018. Our study includes 160 cases of AEN and constitutes the largest to date review of “black esophagus”[6]. Overall, the present work may serve as a useful guide to clinicians contemplating how to best treat this rare condition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy and data extraction

We performed a PubMed/Medline search for English-language case reports and case series, using the keywords "acute esophageal necrosis" OR "black esophagus" OR "acute necrotizing esophagitis". Articles were screened by 2 independent reviewers (Theochari NA, Schizas D) and conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer (Kanavidis P). The reference lists of systematically reviewed articles were hand-searched for potentially eligible, missed studies. Data extraction of the articles included in our review was performed by Theochari NA and Schizas D.

Eligibility criteria for inclusion and exclusion

Eligible articles were identified on the basis of the following inclusion criteria: (1) Papers published in English; (2) Primary research papers; (3) Papers that included patients older than 18 years old; and (4) Papers that included patients who were treated for AEN. Exclusion criteria were the following: (1) Papers that are not published in English; (2) Reviews, letters to the editor; and (3) Papers with inadequate data.

Statistical analysis

Variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation when continuous, or frequencies and percentages when categorical. Continuous variables were analyzed with independent samples student’s t-test, for normally distributed variables, or Mann-Whitney U-test otherwise (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality was used). For categorical variables Pearson’s Chi-Square test was used, with Yates’ continuity correction when appropriate, whereas for ordinal variables we used Wilcoxon rank sum test. Univariate logistic regression was performed with logit transformation of data. Exploratorily, the outcome “death” was dichotomized and logistic regression was utilized since performing valid time-to-event analyses was not deemed feasible due to missing data and inadequate follow-up data. The level of statistical significance was set at 5%. Statistical analysis was performed with R-project environment for statistical computing (https://www.r-project.org/).

Protocol registration

This study is registered with the PROSPERO registry and its unique identifying number is: CRD42018112571.

RESULTS

Literature search results

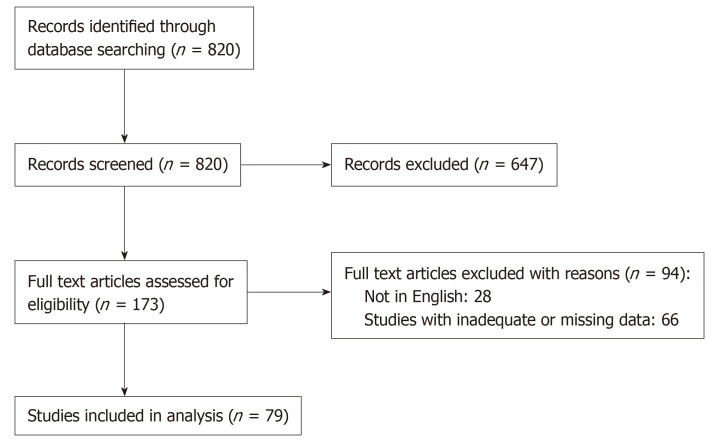

The search produced 820 PubMed results (October 24, 2018). The publications matching our selection criteria were 81. Ultimately, 79 studies satisfied our inclusion criteria and were selected for data collection (Figure 1). Of those, 69 were case reports[3,5,7-64] and 10 were cases series[2,65-73] including 69 and 45 patients respectively. A total of 114 of 160 patients were selected for the pooled analysis, as some case series did not publish individual patient data.

Figure 1.

Prisma flow chart.

Demographics and clinicopathological features

There were 114 patients who were diagnosed with AEN included in our study, of which 83 male and 31 female (M:F ratio of 2.7:1). Mean age was 62.1 ± 16.1. The most common presenting symptom was melena, hematemesis or other manifestation of gastric bleeding (85%), followed by epigastric or chest pain (29.2%) and other peptic symptoms (25.7%), including nausea, vomiting and dysphagia. Other symptoms such as fever, weakness, dyspnea, hypotension were less common (23.9%).

Patients had a diverse medical history, including diabetes mellitus or diabetic ketoacidosis, cardiopulmonary disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarct, angina), alcohol abuse, chronic kidney disease or other kidney-related disease (i.e., nephrectomy), liver-related disease (cirrhosis, liver transplantation) and others (stroke, gastroesophageal reflux disease, GI ulcers, chronic pancreatitis, prostate hypertrophy). Relative frequencies are displayed in Table 1, grouped by affected system.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological features

| Clinicopathological features | |||

| Gender | Σ = 114 | ||

| Male | 83 | 72.8% | |

| Female | 31 | 27.2% | |

| Age (yr) | 62.1 ± 16.1 | 114 | |

| Admission symptoms | Σ = 113 | ||

| Bleeding | 96 | 85.0% | |

| Peptic | 29 | 25.7% | |

| Pain | 33 | 29.2% | |

| Other symptom | 27 | 23.9% | |

| Medical history | Σ = 110 | ||

| Cardiopulmonary | 52 | 47.3% | |

| Diabetes | 40 | 36.4% | |

| Alcohol | 31 | 28.2% | |

| Kidney | 17 | 15.5% | |

| Liver | 19 | 17.3% | |

| Other | 61 | 55.5% | |

| Clinical findings | Σ = 38 | ||

| Shock | 11 | 28,9% | |

| Malnutrition | 1 | 2.6% | |

| AKI | 3 | 7.9% | |

| Other | 24 | 63.2% | |

| Involvement of esophagus (relative to GEJ) | Σ = 98 | ||

| Upper | 33 | 33.7% | |

| Middle | 63 | 64.3% | |

| Lower | 91 | 92.9% | |

AKI: Acute kidney injury; GEJ: Gastroesophageal junction.

Clinical findings on admission were not always reported, but the most severe among them were signs of hypovolemic or septic shock/multiple organ dysfunction/sepsis (73%), acute kidney injury (20%) and malnutrition (7%). Lower esophageal involvement was almost always present (92.9%), with extension to the middle esophagus in many cases (64.3%). Upper esophagus was involved in only 33.7% of the cases.

Treatment

Surgical or endoscopic intervention was required in 24.6% of the cases, whereas 75.4% were treated conservatively. Data available for the cases where intervention was required reveals that endoscopic treatment was preferred in 15 cases (14%), 2 of which later required surgical re-intervention, while surgical-first approach was used in 11 cases (10%). Most survivors received a follow-up endoscopy (89%), with a complication rate of 18.7%. A total of 32 patients died (29.9%), either during the initial hospital stay or during the follow-up period. Follow-up data was available for 78.9% of the patients. Mean overall follow-up was 66.2 ± 101.8 d, (or 82.9 ± 113.2 d among survivors) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Treatment modalities, follow-up

| Treatment modalities | |||

| Intervention | Σ = 114 | ||

| Yes | 28 | 24.6% | |

| No | 86 | 75.4% | |

| Management | Σ = 105 | ||

| Conservative | 79 | 75.2% | |

| Surgical | 11 | 10.5% | |

| Endoscopic | 13 | 12.4% | |

| Endoscopic + surgical | 2 | 1.9% | |

| Follow-up endoscopy | Yes | 67 | 58.8% |

| Complications | Yes | 14 | 12.3% |

| Death | Yes | 32 | 29.9% |

| FUP (overall; mean; SD) | 66.2 ± 101.8 | 90 | 90/114 |

| FUP (dead; mean; SD) | 16.6 ± 21.8 | 23 | 23/32 |

| FUP (alive; mean; SD) | 82.9 ± 113.2 | 65 | 65/75 |

FUP: Follow up; SD: Standard deviation.

Table 3.

Endoscopic intervention

| Endoscopic intervention | |

| Modalities | n (%) |

| Stenting | 1 (7.5) |

| Savary dilatations | 1 (7.5) |

| Balloοn dilatations | 11 (85) |

| Total | 13 |

Outcomes

On univariate logistic regression, GI symptoms on presentation [Odds ratio (OR) 3.50 (1.09-11.30), P = 0.03] and need for surgical or endoscopic treatment [surgical: OR 1.25 (1.03-1.51), P = 0.02; endoscopic: OR 1.4 (1.17-1.66), P < 0.01] were associated with increased odds of complications (Table 4). Patients that underwent both endoscopic and surgical intervention had even higher complication rate; OR 2.58 (1.7-3.93), P < 0.01. Exploratory logistic regression for the dichotomized “death” endpoint (Table 5) did not reveal any statistically significant prognostic factors.

Table 4.

Univariate logistic regression for complications

| OR | LCI | HCI | P value | ||

| Gender | Male | 0.95 | 0.83 | 1.09 | 0.45 |

| Female | (ref) | ||||

| Age | +1 yr | 0.990 | 0.957 | 1.025 | 0.553 |

| Admission symptoms | Bleeding | 0.60 | 0.16 | 2.91 | 0.48 |

| Peptic | 3.50 | 1.09 | 11.30 | 0.03 | |

| Pain | 2.00 | 0.61 | 6.29 | 0.24 | |

| Other symptom | 0.86 | 0.18 | 3.04 | 0.83 | |

| None | (ref) | ||||

| Medical history | Cardiac | 0.63 | 0.18 | 1.95 | 0.43 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.46 | 0.45 | 4.53 | 0.52 | |

| Alcohol abuse | 1.08 | 0.28 | 3.54 | 0.90 | |

| Kidney diseases | 0.94 | 0.14 | 3.94 | 0.94 | |

| Liver diseases | 3.41 | 0.94 | 11.49 | 0.05 | |

| Other | 0.85 | 0.27 | 2.66 | 0.78 | |

| Clinical findings | Malnutrition | 0.87 | 0.44 | 1.74 | 0.70 |

| AKI | 0.87 | 0.58 | 1.30 | 0.50 | |

| Other | 1.15 | 0.77 | 1.73 | 0.50 | |

| Involvement of esophagus (to GEJ) | Upper | 2.67 | 0.74 | 9.99 | 0.13 |

| Middle | 0.97 | 0.27 | 3.94 | 0.96 | |

| Lower | 1.13 | 0.88 | 1.44 | 0.33 | |

| Intervention | Yes | 11.39 | 3.41 | 45.44 | < 0.01 |

| No | (ref) | ||||

| Management | Conservative | (ref) | |||

| Surgical | 1.25 | 1.03 | 1.51 | 0.02 | |

| Endoscopic | 1.4 | 1.17 | 1.66 | < 0.01 | |

| Endoscopic + surgical | 2.58 | 1.7 | 3.93 | < 0.01 | |

OR: Odds ratio; LCI: Lower confidence interval; HCI: Higher confidence interval; AKI: Acute kidney injury; GEJ: Gastroesophageal junction.

Table 5.

Univariate logistic regression for death

| OR | LCI | HCI | P value | ||

| Gender | Male | 0.99 | 0.40 | 2.58 | 0.99 |

| Female | (ref) | ||||

| Age | +1 yr | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 0.30 |

| Admission symptoms | Bleeding | 1.33 | 0.42 | 5.09 | 0.64 |

| Peptic | 0.72 | 0.26 | 1.85 | 0.51 | |

| Pain | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.84 | 0.03 | |

| Other symptom | 0.83 | 0.29 | 2.15 | 0.70 | |

| None | (ref) | ||||

| Medical history | Cardiac | 1.06 | 0.46 | 2.44 | 0.88 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.81 | 0.32 | 1.92 | 0.64 | |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.80 | 0.30 | 2.01 | 0.65 | |

| Kidney diseases | 2.34 | 0.75 | 7.21 | 0.13 | |

| Liver diseases | 1.47 | 0.50 | 4.10 | 0.47 | |

| Other | 0.55 | 0.23 | 1.26 | 0.16 | |

| Clinical findings | malnutrition | 0.75 | 0.30 | 1.87 | 0.54 |

| AKI | 1.05 | 0.61 | 1.83 | 0.85 | |

| Other | 0.95 | 0.55 | 1.65 | 0.85 | |

| Involvement of esophagus (to GEJ) | Upper | 0.57 | 0.20 | 1.49 | 0.27 |

| Middle | 0.59 | 0.24 | 1.49 | 0.26 | |

| Lower | 1.37 | 0.91 | 2.08 | 0.13 | |

| Intervention | Yes | 0.63 | 0.21 | 1.69 | 0.38 |

| No | (ref) | ||||

| Management | Conservative | (ref) | |||

| Surgical | 0.96 | 0.71 | 1.30 | 0.79 | |

| Endoscopic | 0.77 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 0.06 | |

| Endoscopic + surgical | 0.71 | 0.29 | 1.75 | 0.46 | |

OR: Odds ratio; LCI: Lower confidence interval; HCI: Higher confidence interval; AKI: Acute kidney injury; GEJ: Gastroesophageal junction.

Publication year

A sub-analysis separating early versus late cases (after 2006) revealed a significantly increased frequency of surgical or endoscopic intervention of 30.1% for the late cases, compared to 9.7% for the early cases (P = 0.04). Mortality rate, however, was similar, for the late (30.3%) and the early cases (29%) (P = 1.00).

DISCUSSION

ANE was first described by Goldenberg et al[1] in 1990 . The largest case series of AEN published to date included 29 and 16 cases respectively[74,75]. In 2007, Gurvits et al[6] attempted for the first time to present a review of the literature and described 88 patients with black esophagus. Since then, no systematic or broad review of the published literature has been performed. To guide clinicians treating patients with AEN using up-to-date information we systematically reviewed relevant literature from 1990 until 2018. Our analysis includes 114 patients and provides a comprehensive overview of the demographics, clinical features, treatment options, and outcomes of patients with AEN.

Several theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of AEN. The most popular is ischemia due to low flow rates or shock. Reichart et al[3] reported that ischemic AEN is typically secondary to cardiac dysfunction, prolonged hypotension or sepsis. Our findings support this statement with 47.3% of the patients described in this review having a cardiopulmonary medical history. Another factor that argues in favor of an ischemic etiology in the present study is the predominance of esophageal necrosis in the middle and lower thirds of esophagus (64.3% and 92.9% respectively) which are usually less vascularized and thus more prone to ischemic injury. Other causes of AEN include gastric outlet obstruction with massive reflux of gastric secretions, viral infection, hypersensitivity to antibiotics, hypothermia and corrosive trauma[3].

According to our analysis, AEN affects predominately men (72%) at a mean age of 62 years. Nevertheless, AEN can develop at virtually any age. In our review AEN, was seen in 6 patients in the third decade of life and in male patient at the age of 10 year[17]. The majority (85%) of patients presented at the ER with symptoms of upper GI bleeding i.e., melena, hematemesis or other manifestations of gastric bleeding. Associated clinical findings were not always reported, but the most commonly reported ones were hypovolemic or septic shock[74]. Patients’ medical history may also be a serious risk factor for ANE[76]. Most patients included in this systematic review had history of a significant cardiopulmonary disease (47.3%) while others suffered from diabetes mellitus (36.4%), alcohol abuse (28.2%), as well as liver (17.3%) and kidney related disease (15.5%).

The diagnosis of AEN is made endoscopically by identifying diffuse circumferential progressive black discoloration of the esophagus with abrupt demarcation at the Z-line. In six cases reported in this review, the mucosa of the esophagus was also covered by yellow or white exudates at the time of initial scoping[8,73]. Histologically, AEN specimens shows necrotic debris, mucosal and submucosal necrosis with a local inflammatory response[8,73].

Given the rarity of the condition, there are no clear guidelines regarding how to best manage patients with AEN. Most authors recommend a conservative treatment approach which includes correction of underlying disorders, total parenteral nutrition, adequate intravenous hydration, broad spectrum antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors and sucralfate suspension[4]. Blood cell transfusion is also recommended when necessary. In case of necrosis or perforation, early surgical or endoscopic intervention is required[5]. In this systematic review, surgery was performed as first line treatment in 11 cases whereas endoscopic treatment was used in 15 patients, 2 of which later required surgical re -intervention. Surprisingly, a sub- analysis that we conducted, separating cases before and after 2006 (i.e., when the last systematic review was published) showed that the frequency of surgical or endoscopic intervention was significantly increased from 9.7% (before 2006) to 30.1% (after 2006) (P = 0.04). That said, the increased rate of operative intervention did not seem to affect overall patient outcomes.

The most commonly reported complication is stricture while others can be stenosis, abscesses, tracheoesophageal fistula and perforation of the esophagus[1]. In this systematic review only 14 (12.3% of the patients) developed complications. Of them, 10 (70%) developed an esophageal stricture and four (30%) a tracheoesophageal fistula. Interestingly, univariate logistic regression revealed an association between the presence of GI symptoms on admission [OR 3.50 (1.09-11.30), P = 0.03] with increased odds of post-AEN complications. Patients that required surgical or endoscopic treatment [surgical: OR 1.25 (1.03-1.51), P = 0.02; endoscopic: OR 1.4 (1.17-1.66), P < 0.01] were also more likely to develop complications. This is not surprising since patients with more severe disease at presentation are more likely to receive surgical intervention. Moreover, patients that underwent both endoscopic and surgical intervention had an even higher complication rate [OR 2.58 (1.7-3.93), P < 0.01].

A total of 32 patients included in our study died (29.9%), either during the initial hospital stay or subsequently at follow-up. The high mortality rate that is seen in AEN may be potentially related to patient characteristics such as serious medical history, older age and higher incidence of malignancy[1].

Methodological strengths of the present paper include: (1) Comprehensive literature search using rigorous and systematic methodology; and (2) Detailed data extraction. We also performed a sub-analysis separating early versus late cases[6] (after 2006 when the last systematic review was published) which showed that the implementation of surgical/endoscopic interventions have increased threefold.

This analysis has certain limitations. As with any systematic review, certain studies did not report on all outcomes of interest and therefore all cumulative results were estimated based on available data. Only papers published in English were eligible and all included studies were retrospective case reports or small case series. Lastly, due to missing data, performing strong survival modeling was not possible and therefore we treated “death” as a binary outcome and performed logistic regression to provide an approximation of mortality predictors.

In conclusions, AEN is a rare condition with high mortality. Although, the etiology of this disease is likely multi-factorial, ischemia seems to play a pivotal role in pathogenesis. The diagnosis of AEN is mainly based on upper GI endoscopy revealing a black-appearing esophageal mucosa circumferentially. Although the rate of operative interventions has increased in recent years, conservative treatment still seems to be the most commonly used treatment approach. Black esophagus is anticipated to become a more commonly recognized and described entity. To that end, a staging system that classifies the patients with AEN according to their symptoms on admission, their medical history and the endoscopic findings would be meaningful. Overall, further investigations are needed to better understand the risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnostic challenges and optimum treatment approach for this rare but potentially lethal condition.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN) is a severe medical condition with multifactorial etiology. Our experience is mainly based on case reports and small case series.

Research motivation

Given the rarity of this entity, further investigations are needed to better understand the risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnostic challenges and how to best treat this potentially lethal disease.

Research objectives

Our objective was to investigate all available data on demographics, clinical features, outcomes of this condition and to suggest the best management.

Research methods

We performed a systematic literature search with respect to the PRISMA statement. Univariate logistic regression was performed with logit transformation of data.

Research results

Overall, 114 patients with AEN were included in this study. The most common symptoms on admission were melena, hematemesis or other manifestations of gastric bleeding. With regards to treatment modalities, conservative treatment was the most widely implemented choice followed by surgical or/and endoscopic intervention. A sub-analysis separating early versus late cases (after 2006) revealed a significantly increased frequency of surgical or endoscopic intervention. Nevertheless, further research work is needed to better understand how to best treat this potentially deadly disease.

Research conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the most up to date and comprehensive systematic review regarding AEN. This rare entity seems to have multi-factorial etiology, but ischemia seems to play the most significant role in pathogenesis. Diagnosis is made by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, while conservative treatment seems to be still the most popular modality. Nevertheless, our study revealed that operative interventions have increased the last years. Black esophagus is a medical condition that is still difficult recognized. To that end, a staging system that classifies the patients with AEN according to their symptoms on admission, their medical history and the endoscopic findings would be meaningful.

Research perspectives

Further investigations are needed to better understand the risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnostic challenges and optimum treatment approach for this rare but potentially lethal condition.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: There is no conflict of interest associated with any of the senior author or other coauthors contributed their efforts in this manuscript. All the Authors have no conflict of interest related to the manuscript.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: October 19, 2019

First decision: November 19, 2019

Article in press: December 23, 2019

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Aktekin A, Cremers I, Dogan U, Isik A, Mercado MA, Okamoto H, Yeh HZ S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Dimitrios Schizas, First Department of Surgery, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Laikon General Hospital, Athens 11527, Greece; Department of Medicine, Surgery Working Group, Society of Junior Doctors, Athens 15122, Greece.

Nikoletta A Theochari, Department of Medicine, Surgery Working Group, Society of Junior Doctors, Athens 15122, Greece. nickyth12@gmail.com.

Konstantinos S Mylonas, First Department of Surgery, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Laikon General Hospital, Athens 11527, Greece; Department of Medicine, Surgery Working Group, Society of Junior Doctors, Athens 15122, Greece; Laboratory of Experimental Surgery and Surgical Research N.S. Christeas, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens 11527, Greece.

Prodromos Kanavidis, First Department of Surgery, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Laikon General Hospital, Athens 11527, Greece.

Eleftherios Spartalis, Laboratory of Experimental Surgery and Surgical Research N.S. Christeas, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens 11527, Greece.

Stamatina Triantafyllou, First Propedeutic Department of Surgery, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Hippocration General Hospital, Athens 11527, Greece.

Konstantinos P Economopoulos, Department of Medicine, Surgery Working Group, Society of Junior Doctors, Athens 15122, Greece; Department of Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27708, United States.

Dimitrios Theodorou, First Propedeutic Department of Surgery, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Hippocration General Hospital, Athens 11527, Greece.

Theodore Liakakos, First Department of Surgery, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Laikon General Hospital, Athens 11527, Greece.

References

- 1.Goldenberg SP, Wain SL, Marignani P. Acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:493–496. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90844-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurvits GE, Cherian K, Shami MN, Korabathina R, El-Nader EM, Rayapudi K, Gandolfo FJ, Alshumrany M, Patel H, Chowdhury DN, Tsiakos A. Black esophagus: new insights and multicenter international experience in 2014. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:444–453. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3382-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reichart M, Busch OR, Bruno MJ, Van Lanschot JJ. Black esophagus: a view in the dark. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13:311–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2000.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3219–3225. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i26.3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang J, Weigel TL. Acute esophageal necrosis: "black esophagus". JSLS. 2007;11:165–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1974-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trappe R, Pohl H, Forberger A, Schindler R, Reinke P. Acute esophageal necrosis (black esophagus) in the renal transplant recipient: manifestation of primary cytomegalovirus infection. Transpl Infect Dis. 2007;9:42–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2006.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagri S, Hwang R, Anand S, Kurz J. Herpes simplex esophagitis presenting as acute necrotizing esophagitis ("black esophagus") in an immunocompetent patient. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E169. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YH, Choi SY. Black esophagus with concomitant candidiasis developed after diabetic ketoacidosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5662–5663. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i42.5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka K, Toyoda H, Hamada Y, Aoki M, Kosaka R, Noda T, Katsurahara M, Nakamura M, Ninomiya K, Inoue H, Imoto I, Takei Y. A relapse case of acute necrotizing esophagitis. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E305. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong JW, Kim SU, Park HN, Seo JH, Lee YC, Kim H. Black esophagus associated with alcohol abuse. Gut Liver. 2008;2:133–135. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2008.2.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maher MM, Nassar MI. Black esophagus: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:367. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumann DA 2nd, Francis DL, Baron TH. Proximal black esophagus: a case report and review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:180–181. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katsuhara K, Takano S, Yamamoto Y, Ueda S, Nobuhara K, Kiyasu Y. Acute esophageal necrosis after lung cancer surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;57:437–439. doi: 10.1007/s11748-009-0423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JK, Bhargava V, Mittal RK, Ghosh P. Achalasia, alcohol-stasis, and acute necrotizing esophagitis: connecting the dots. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:612–614. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1297-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garas G, Wou C, Sawyer J, Amygdalos I, Gould S. Acute oesophageal necrosis syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2011:2011. doi: 10.1136/bcr.10.2010.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaissert HA, Breuer CK, Weissburg A, Mermel L. Surgical management of necrotizing Candida esophagitis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:231–233. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)01144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calabrese C, Liguori G. Acute esophageal necrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:A30. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Wal-Visscher E, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, van Sambeek MR, Haanschoten M, Botman KJ, de Hingh IH. Type B aortic dissection resulting in acute esophageal necrosis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25:837.e1–837.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albuquerque A, Ramalho R, Rios E, Lopes JM, Macedo G. Black esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:333. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrera VG, Rodriguez SV, Gonzalez de la Ballina Gonzalez E, Luis Ulla Rocha J. Acute esophageal necrosis in a patient with multiple comorbidity. Ann Gastroenterol. 2012;25:162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kabaçam G, Yakut M, Soykan I. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:283. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2011.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira O, Figueira-Coelho J, Picado B, Costa JN. Black oesophagus. BMJ Case Rep. 2013:2013. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-008188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maroy B. Black esophagus complicating variceal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2013;45 Suppl 2 UCTN:E237. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Román Fernández A, López Álvarez A, Fossati Puertas S, Areán González I, Varela García O, Viaño López PM. Black esophagus (acute esophageal necrosis) after spinal anesthesia. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2014;61:401–403. doi: 10.1016/j.redar.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abed J, Mankal P, Judeh H, Kim S. Acute Esophageal Necrosis: A Case of Black Esophagus Associated with Bismuth Subsalicylate Ingestion. ACG Case Rep J. 2014;1:131–133. doi: 10.14309/crj.2014.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tse A, Basu S, Ali H, Hamouda A. Black necrotic oesophagus following the use of biodegradable stent for benign oesophageal stricture. J Surg Case Rep. 2015:2015. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjv072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barjas E, Pires S, Lopes J, Valente A, Oliveira E, Palma R, Raimundo M, Alexandrino P, Moura MC. Cytomegalovirus acute necrotizing esophagitis. Endoscopy. 2001;33:735. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gómez V, Propst JA, Francis DL, Canabal JM, Franco PM. Black esophagus: an unexpected complication in an orthotopic liver transplant patient with hemorrhagic shock. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2597–2599. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimura Y, Seno H, Yamashita Y. A case of acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:525–526. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnes T, Yan S, Kaakeh Y. Necrotizing Esophagitis and Bleeding Associated With Cefazolin. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1214–1218. doi: 10.1177/1060028014537038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zacharia GS, Sandesh K, Ramachandran T. Acute esophageal necrosis: an uncommon cause of hematemesis. Oman Med J. 2014;29:302–304. doi: 10.5001/omj.2014.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimamura Y, Nakamura K, Ego M, Omata F. Advanced endoscopic imaging in black esophagus. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:471–472. doi: 10.1155/2014/620709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caravaca-Fontán F, Jimenez S, Fernández-Rodríguez A, Marcén R, Quereda C. Black esophagus in the early kidney post-transplant period. Clin Kidney J. 2014;7:613–614. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfu094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talebi-Bakhshayesh M, Samiee-Rad F, Zohrenia H, Zargar A. Acute Esophageal Necrosis: A Case of Black Esophagus with DKA. Arch Iran Med. 2015;18:384–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abu-Zaid A, Solimanie S, Abudan Z, Al-Hussaini H, Azzam A, Amin T. Acute esophageal necrosis (black esophagus) in a 40-year-old man. Ann Saudi Med. 2015;35:80–81. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2015.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salem GA, Ahluwalia S, Guild RT. A case of acute oesophageal necrosis (AEN) in a hypothermic patient. The grave prognosis of the black oesophagus. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2015;16:136–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iorio N, Bernstein GR, Malik Z, Schey R. Acute Esophageal Necrosis Presenting With Henoch-Schönlein Purpura. ACG Case Rep J. 2015;3:17–19. doi: 10.14309/crj.2015.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katsinelos P, Christodoulou K, Pilpilidis I, Papagiannis A, Xiarchos P, Tsolkas P, Vasiliadis I, Eugenidis N. Black esophagus: an unusual finding during routine endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2001;33:904. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galanopoulos M, Anastasiadis S, Archavlis E, Mantzaris GJ. Black esophagus: an uncommon cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Intern Emerg Med. 2016;11:1019–1020. doi: 10.1007/s11739-015-1360-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rigolon R, Fossà I, Rodella L, Targher G. Black esophagus syndrome associated with diabetic ketoacidosis. World J Clin Cases. 2016;4:56–59. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i2.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galtés I, Gallego MÁ, Esgueva R, Martin-Fumadó C. Acute oesophageal necrosis (black oesophagus) Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016;108:154–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma V, De A, Ahuja A, Lamoria S, Lamba BM. Acute Esophageal Necrosis Caused by Candidiasis in a Patient with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Emerg Med. 2016;51:77–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pautola L, Hakala T. Medication-induced acute esophageal necrosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10:267. doi: 10.1186/s13256-016-1043-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodrigues BD, Dos Santos R, da Luz MM, Chaves E Silva F, Reis IG. Acute esophageal necrosis. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9:341–344. doi: 10.1007/s12328-016-0692-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joubert KD, Betzold RD, Steliga MA. Successful Treatment of Esophageal Necrosis Secondary to Acute Type B Aortic Dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:e547–e549. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.04.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakatoku Y, Fukaya M, Miyata K, Nagino M. Successful bypass operation for esophageal obstruction after acute esophageal necrosis: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2017;3:4. doi: 10.1186/s40792-016-0277-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alcaide N, Fernández Salazar L, Ruiz Rebollo L, González Obeso E. Acute esophageal necrosis resolved in 72 hours. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2017;109:217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bonaldi M, Sala C, Mariani P, Fratus G, Novellino L. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis, clinical case and review of literature. J Surg Case Rep. 2017;2017:rjx037. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjx037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Odelowo OO, Hassan M, Nidiry JJ, Marshalleck JJ. Acute necrotizing esophagitis: a case report. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94:735–737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manno V, Lentini N, Chirico A, Perticone M, Anastasio L. Acute esophageal necrosis (black esophagus): a case report and literature review. Acta Diabetol. 2017;54:1061–1063. doi: 10.1007/s00592-017-1028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim DB, Bowers S, Thomas M. Black and White Esophagus: Rare Presentations of Severe Esophageal Ischemia. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:256–259. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsuo T, Ishii N. Acute Esophageal Necrosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1378. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1703305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khan AM, Hundal R, Ramaswamy V, Korsten M, Dhuper S. Acute esophageal necrosis and liver pathology, a rare combination. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2457–2458. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i16.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rejchrt S, Douda T, Kopácová M, Siroký M, Repák R, Nozicka J, Spacek J, Bures J. Acute esophageal necrosis (black esophagus): endoscopic and histopathologic appearance. Endoscopy. 2004;36:1133. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamauchi J, Mitsufuji S, Taniguchi J, Sakai M, Tatsumi N, Yasuda Y, Konishi H, Wakabayashi N, Kataoka K, Okanoue T. Acute esophageal necrosis followed by upper endoscopy and esophageal manometry/pH test. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1718–1721. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2924-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Endo T, Sakamoto J, Sato K, Takimoto M, Shimaya K, Mikami T, Munakata A, Shimoyama T, Fukuda S. Acute esophageal necrosis caused by alcohol abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5568–5570. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i35.5568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Del Hierro PM. Acute Necrotizing Esophagitis Followed by Duodenal Necrosis. Gastroenterology Res. 2011;4:286–288. doi: 10.4021/gr361w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Geller A, Aguilar H, Burgart L, Gostout CJ. The black esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2210–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Obermeyer R, Kasirajan K, Erzurum V, Chung D. Necrotizing esophagitis presenting as a black esophagus. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1430–1433. doi: 10.1007/s004649900875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katsinelos P, Pilpilidis I, Dimiropoulos S, Paroutoglou G, Kamperis E, Tsolkas P, Kapelidis P, Limenopoulos B, Papagiannis A, Pitarokilis M, Trakateli C. Black esophagus induced by severe vomiting in a healthy young man. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:521. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-4248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carter RR, Coughenour JP, Van Way CW, 3rd, Goldstrich J. Acute esophageal necrosis with pneumomediastinum: a case report. Mo Med. 2007;104:276–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Le K, Ahmed A. Acute necrotizing esophagitis: case report and review of the literature. J La State Med Soc. 2007;159:330, 333–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Usmani A, Samarany S, Nardino R, Shaib W. Black esophagus in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis. Conn Med. 2011;75:467–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grudell AB, Mueller PS, Viggiano TR. Black esophagus: report of six cases and review of the literature, 1963-2003. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19:105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Singh D, Singh R, Laya AS. Acute esophageal necrosis: a case series of five patients presenting with "Black esophagus". Indian J Gastroenterol. 2011;30:41–45. doi: 10.1007/s12664-011-0082-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu MH, Wu HY. Incremental change in acute esophageal necrosis: report of two cases. Surg Today. 2014;44:363–365. doi: 10.1007/s00595-013-0526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Worrell SG, Oh DS, Greene CL, DeMeester SR, Hagen JA. Acute esophageal necrosis: a case series and long-term follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:341–342. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shafa S, Sharma N, Keshishian J, Dellon ES. The Black Esophagus: A Rare But Deadly Disease. ACG Case Rep J. 2016;3:88–91. doi: 10.14309/crj.2016.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koop A, Bartel MJ, Francis D. A Case of Acute Esophageal Necrosis and Duodenal Disease in a Patient With Adrenal Insufficiency. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:A17–A18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kalva NR, Tokala MR, Dhillon S, Pisoh WN, Walayat S, Vanar V, Puli SR. An Unusual Cause of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Acute Esophageal Necrosis. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2016;2016:6584363. doi: 10.1155/2016/6584363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Averbukh LD, Mavilia MG, Gurvits GE. Acute Esophageal Necrosis: A Case Series. Cureus. 2018;10:e2391. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ben Soussan E, Savoye G, Hochain P, Hervé S, Antonietti M, Lemoine F, Ducrotté P. Acute esophageal necrosis: a 1-year prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:213–217. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Augusto F, Fernandes V, Cremers MI, Oliveira AP, Lobato C, Alves AL, Pinho C, de Freitas J. Acute necrotizing esophagitis: a large retrospective case series. Endoscopy. 2004;36:411–415. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yasuda H, Yamada M, Endo Y, Inoue K, Yoshiba M. Acute necrotizing esophagitis: role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1741-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moretó M, Ojembarrena E, Zaballa M, Tánago JG, Ibánez S. Idiopathic acute esophageal necrosis: not necessarily a terminal event. Endoscopy. 1993;25:534–538. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1009121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]