Abstract

Background

Raised intracranial pressure (ICP) is an important complication of severe brain injury, and is associated with high mortality. Barbiturates are believed to reduce ICP by suppressing cerebral metabolism, thus reducing cerebral metabolic demands and cerebral blood volume. However, barbiturates also reduce blood pressure and may, therefore, adversely effect cerebral perfusion pressure.

Objectives

To assess the effects of barbiturates in reducing mortality, disability and raised ICP in people with acute traumatic brain injury. To quantify any side effects resulting from the use of barbiturates.

Search methods

The following electronic databases were searched on 26 September 2012: CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE (Ovid SP), PubMed, EMBASE (Ovid SP), PsycINFO (Ovid SP), PsycEXTRA (Ovid SP), ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science. Searching was not restricted by date, language or publication status. We also searched the reference lists of the included trials and review articles. We contacted researchers for information on ongoing studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of one or more of the barbiturate class of drugs, where study participants had clinically diagnosed acute traumatic brain injury of any severity.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors screened the search results, extracted data and assessed the risk of bias in the trials.

Main results

Data from seven trials involving 341 people are included in this review.

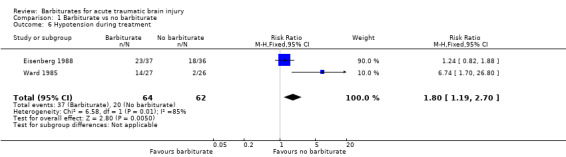

For barbiturates versus no barbiturate, the pooled risk ratio (RR) of death from three trials was 1.09 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 1.47). Death or disability, measured using the Glasgow Outcome Scale was assessed in two trials, the RR with barbiturates was 1.15 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.64). Two trials examined the effect of barbiturate therapy on ICP. In one, a smaller proportion of patients in the barbiturate group had uncontrolled ICP (68% versus 83%); the RR for uncontrolled ICP was 0.81 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.06). In the other, mean ICP was also lower in the barbiturate group. Barbiturate therapy results in an increased occurrence of hypotension (RR 1.80; 95% CI 1.19 to 2.70). For every four patients treated, one developed clinically significant hypotension. Mean body temperature was significantly lower in the barbiturate group.

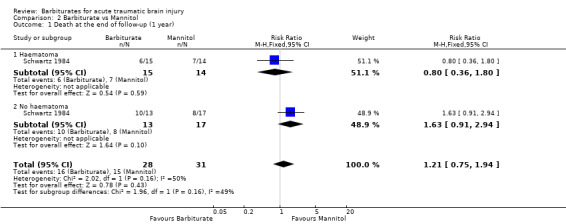

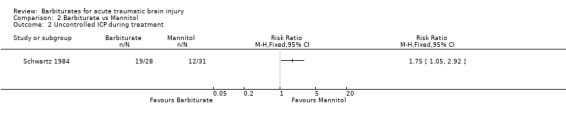

In one study of pentobarbital versus mannitol there was no difference in death between the two study groups (RR 1.21; 95% CI 0.75 to 1.94). Pentobarbital was less effective than mannitol for control of raised ICP (RR 1.75; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.92).

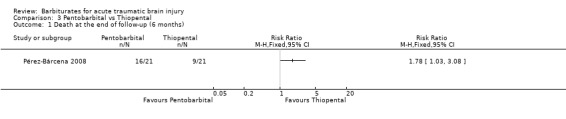

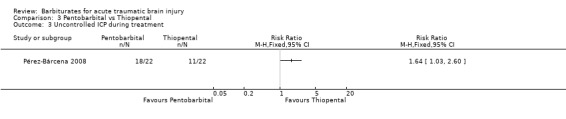

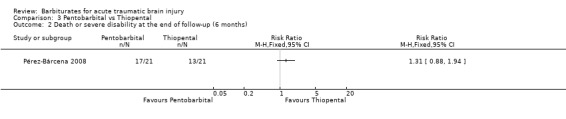

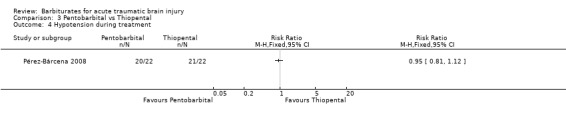

In one study the RR of death with pentobarbital versus thiopental was 1.78 (95% CI 1.03 to 3.08) in favour of thiopental. Fewer people had uncontrollable ICP with thiopental (RR 1.64; 95% CI 1.03 to 2.60). There was no significant difference in the effects of pentobarbital versus thiopental for death or disability, measured using the Glasgow Outcome Scale (RR 1.31; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.94), or hypotension (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.81 to 1.12).

Authors' conclusions

There is no evidence that barbiturate therapy in patients with acute severe head injury improves outcome. Barbiturate therapy results in a fall in blood pressure in one in four patients. This hypotensive effect will offset any ICP lowering effect on cerebral perfusion pressure.

Keywords: Humans, Barbiturates, Barbiturates/adverse effects, Barbiturates/therapeutic use, Brain Injuries, Brain Injuries/complications, Brain Injuries/drug therapy, Brain Injuries/mortality, Central Nervous System Agents, Central Nervous System Agents/adverse effects, Central Nervous System Agents/therapeutic use, Cerebrovascular Circulation, Cerebrovascular Circulation/drug effects, Hypotension, Hypotension/chemically induced, Intracranial Hypertension, Intracranial Hypertension/etiology, Intracranial Hypertension/prevention & control, Intracranial Pressure, Intracranial Pressure/drug effects, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Risk

Plain language summary

Barbiturate drugs for people with traumatic brain injury

An injury to the head can lead to the brain swelling from leaking blood or from clotting, or an imbalance in fluid around the brain. As space inside the skull is limited, this can cause dangerous levels of pressure on the brain (raised intracranial pressure − ICP). Barbiturates are sedatives that are commonly used to treat ICP. They slow down brain action and this can reduce the production of fluid.

Data from seven trials involving 341 people with brain injury are included in this review. There is no evidence that barbiturates reduce death, and although they reduce intracranial pressure, one in four people have problems because barbiturates also cause low blood pressure.

Background

Description of the condition

An injury to the head can lead to the brain swelling from leaking blood or from clotting, or an imbalance in fluid around the brain. As space inside the skull is limited, this can cause dangerous levels of pressure on the brain (raised intracranial pressure − ICP). ICP is an important complication of severe brain injury, and is associated with high mortality (Pickard 1993).

Description of the intervention

Barbiturate drugs have been shown to reduce ICP following brain injury, and are often used when raised ICP is refractory to other medical and surgical approaches (Shapiro 1979).

How the intervention might work

The ICP lowering effect of barbiturates is believed to be due to the coupling of cerebral blood flow to regional metabolic demands. By suppressing cerebral metabolism, barbiturates reduce cerebral metabolic demands, thus reducing cerebral blood volume and ICP.

Why it is important to do this review

At the time this review was first published in 1997 there was evidence of considerable clinical variation in the use of barbiturate drugs following acute severe brain injury. A survey of UK intensive care units found that barbiturates were used in 56% of units (Jeevaratnam 1996). A similar study in the US found that barbiturates were used in 33% of units as a treatment for raised ICP (Ghajar 1995). The review authors keep the review's findings up to date by adding data whenever new studies are published.

Objectives

To assess the effects of barbiturates in reducing death, disability and raised intracranial pressure in people with acute traumatic brain injury. To quantify any side effects resulting from the use of barbiturates.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We sought to identify all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of barbiturate drugs in the management of acute brain injury.

Types of participants

People with a clinically diagnosed acute traumatic brain injury of any severity.

Types of interventions

The experimental intervention comprised one or more of the barbiturate class of drugs (amobarbital, barbital, hexobarbital, mephobarbital, methohexital, murexide, pentobarbital, phenobarbital, secobarbital, thiobarbiturate).

The comparison could be standard care, placebo, or another barbiturate drug.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Death at final follow‐up

Secondary outcomes

Death or disability at final follow‐up (measured by the Glasgow Outcome Scale)

Intracranial pressure during treatment

Hypotension during treatment

Body temperature during treatment

Search methods for identification of studies

The searches were not restricted by date, language or publication status.

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Injuries Group's Trials Search Coordinator searched the following electronic databases;

CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 9);

MEDLINE (Ovid SP) 1950 to September Week 2 2012;

PubMed [www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez/] (last searched 26 September 2012: added to PubMed in the last 60 days);

EMBASE (Ovid SP) 1980 to 2012 Week 38;

PsycINFO (Ovid SP) 1806 to September Week 3 2012;

PsycEXTRA (Ovid SP) 1908 to September 10, 2012;

ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index (SCI) 1970 to Sept 26, 2012;

ISI Web of Science: Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science (CPCI‐S) 1990 to Sept 26, 2012.

The search strategy used for the first version of the review which was published in 1997 can be found in Appendix 1. The search strategy used for this update can be found in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

New trials were sought by checking the reference lists of the included trials, and review articles found through the literature search. We contacted authors of the included trials (both in 1996 during preparation of the original manuscript and again in November 2012) and asked if they were aware of any ongoing studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The two review authors independently screened the search results, and then met to discuss the trials eligible for inclusion. There were no disagreements on the inclusion of trials.

Data extraction and management

The two review authors independently extracted the following information for each trial: the city and country in which the trial took place, its registration number, the years participants were recruited, the source of funding, the number of people randomised, and drop outs. We extracted information on the intervention provided, the timing of administration, dose, route of administration and whether people received the treatment to which they were allocated. We extracted all outcome data, including side effects, the time the outcome measurements were taken, and the number of participants available to provide outcome data. Information on the risk of bias were recorded including the method of randomisation, generation of the randomisation sequence and concealment of the sequence, blinding of patients, physicians and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data and mention of a study protocol.

The Glasgow Outcomes Scale score (Jennet 1975) was converted into a dichotomous outcome according to the following standard grouping: 'Death or disability' included death, persistent vegetative state and severe disability, a 'good outcome' included moderate disability and good recovery.

The two review authors independently extracted study data and checked the data included in the analyses to ensure there were no errors. There were no disagreements during data extraction or 'Risk of bias' assessment.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Both review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using The Cochrane Collaboration's 'Risk of bias' tool (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011 Chapter 8.5)). We contacted the study authors for clarification of study methods and to ask for the study protocol.

Measures of treatment effect

The risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals was calculated for dichotomous outcomes. The mean difference with 95% confidence intervals was calculated for continuous outcomes which used the same scale. The difference between study groups at final follow‐up was calculated.

Unit of analysis issues

A person with brain injury was the unit of analysis. There were no unit of analysis issues.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the study authors in order to obtain missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Trials testing barbiturate therapy against a control group were pooled separately from studies testing barbiturate therapy against another treatment. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed through the Chi2 test, with a P value less than 0.10 indicating differences between study results which warrant further investigation. An I2 test value over 50% also indicated considerable statistical heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In 2012 we contacted the study authors to ask for their study protocol. We received replies but did not receive any original protocols due to the fact the studies were conducted 20‐30 years ago. There are too few studies to include in a funnel plot to assess publication bias. The review has been regularly updated since it was first published in 1997 and we believe all RCTs on the topic are included in the review.

Data synthesis

A Mantel‐Haenzel fixed‐effect model was used for the analysis in order to find the average effect of barbiturate drugs in the included trials.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

No subgroup analyses were conducted.

Sensitivity analysis

No sensitivity analyses were conducted.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

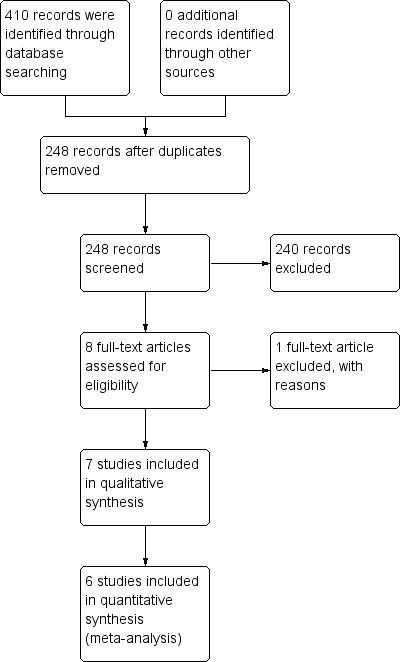

The search strategy identified 410 potentially relevant search results, and seven trial reports met the inclusion criteria. The study identification process is outlined in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Of the seven trials eligible for inclusion, four trials compared barbiturate therapy with no barbiturate, one trial compared barbiturates with mannitol, one trial compared barbiturates with etomidate, and one trial compared pentobarbital with thiopental.

Pérez‐Bárcena 2008: Forty‐four people with severe traumatic brain injury (post resuscitation Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) ≤ 8) and raised ICP (> 20 mmHg) refractory to first level measures were allocated to pentobarbital or thiopental.

Levy 1995: People with severe head injury or ischaemic injury were allocated to receive either pentobarbital or etomidate. The study was stopped after seven patients were randomised, because of adverse effects of etomidate (renal impairment). It is not possible to include data in this review from the four people with brain injury because the trial results are reported by treatment group.

Bohn 1989: Eighty‐two children with severe head injury (GCS ≤ 7) were allocated to receive high‐dose phenobarbitone or no phenobarbitone.

Eisenberg 1988: Seventy‐three people with severe head injury (GCS ≤ 7) with elevated ICP refractory to conventional management were allocated to receive pentobarbital or no pentobarbital.

Ward 1985: Fifty‐three people with head injury over the age of 12 years who had either an acute intradural haematoma or no mass lesion whose best motor response was abnormal flexion or extension. Treatment was started regardless of ICP. People were allocated to pentobarbital or no pentobarbital.

Schwartz 1984: Fifty‐nine people with severe head injury (GCS ≤ 7) with raised ICP (25 torr for more than 125 minutes) were allocated to pentobarbital or mannitol.

Saul 1982: Twenty‐six people with severe head injury (GCS ≤ 7), aged 14 to 81 years, all of whom had ICP monitoring. People were eligible for trial inclusion if ICP reached 25 mmHg for 10 minutes at rest. Patients were allocated to pentobarbital or no pentobarbital. The data were never published. The author was contacted in 1997 but the data are no longer available for inclusion.

Each study is described in more detail in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Excluded studies

One study was excluded (Yano 1981) as the authors explained it was a retrospective case series rather than a randomised controlled trial.

Risk of bias in included studies

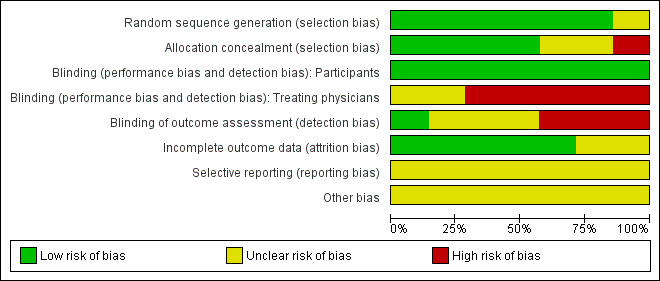

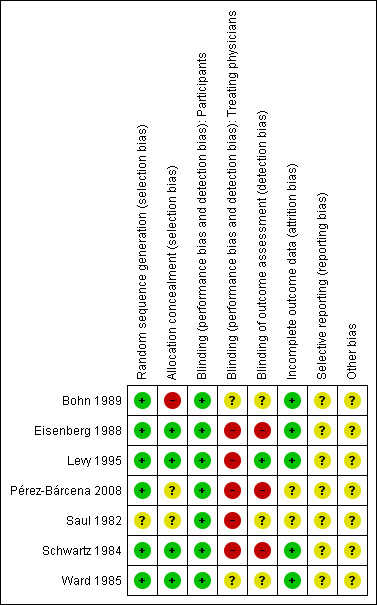

Two figures show our assessment of the risk of bias of the included studies (Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. Seven studies are included in this review.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Six trials had an acceptable randomisation sequence and are judged to be at low risk of bias; the randomisation process was not described in Saul 1982.

Allocation

In the trials by Eisenberg 1988 and Schwartz 1984 allocation was concealed by using sealed opaque envelopes. In the trial by Bohn 1989 allocation was according to ICU physician on duty and is therefore at high risk of bias. In the trials by Ward 1985 and Levy 1995 the review authors judged allocation to be at low risk of bias based on the description of allocation concealment given by the trial authors. In Pérez‐Bárcena 2008 and Saul 1982 the method of allocation concealment was not described.

Blinding

People randomised: In all seven studies the people had a brain injury severe enough to have a Glasgow Coma Scale score of ≤ 8, and so were unaware of the treatment they were receiving.

Treating physicians: In Eisenberg 1988, Levy 1995 and Schwartz 1984 the treating physicians were aware of the treatments they were giving to the people in their care as the treatment dose depended on the injured person's health status and there was no mention of blinding. Blinding was not described in Bohn 1989, Saul 1982 or Ward 1985. The Pérez‐Bárcena 2008 authors specify that treating physicians were not blinded.

Outcome assessors: Blinding was not described in Bohn 1989, Eisenberg 1988, Saul 1982 and Ward 1985. In Levy 1995 the outcome assessors were physicians from another department. There was no blinding in Pérez‐Bárcena 2008. Schwartz 1984 explained through correspondence in 2012 that the outcome assessors were not blinded.

Incomplete outcome data

Complete outcome data were available for Bohn 1989, Eisenberg 1988, Levy 1995, Schwartz 1984 and Ward 1985. In Pérez‐Bárcena 2008 one person was missing from the analysis from each study group at six month follow‐up. In Saul 1982 the study outcomes are not specified, though there is information on deaths.

Selective reporting

The reports by Bohn 1989, Levy 1995, Saul 1982 and Ward 1985 mention a study protocol, but we were unable to obtain a copy of them. (We sought the protocols decades after the trials were conducted.) Schwartz 1984 told us through correspondence in 2012 that there was a study protocol but it was discarded years ago. In correspondence with the authors during 2012 Eisenberg 1988 told us there was a study protocol but it is no longer available. Pérez‐Bárcena 2008 do not mention a study protocol but the manner in which the methods are described implies there was one.

Other potential sources of bias

We were unable to assess potential sources of bias in Saul 1982 as too little information about the study was available. For the other studies there were no particular sources of bias that should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results of this review.

Effects of interventions

1. Barbiturate versus no barbiturate

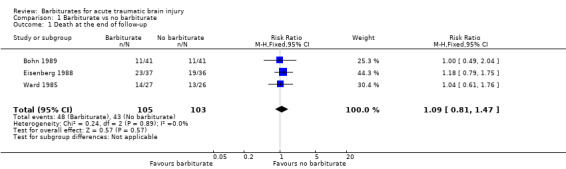

Three trials (Bohn 1989; Eisenberg 1988; Ward 1985) compared barbiturates with no barbiturates and followed people for six months or one year following their injury. The pooled risk ratio (RR) for death was 1.09 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 1.47); there was no statistical heterogeneity. Analysis 1.1

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Barbiturate vs no barbiturate, Outcome 1 Death at the end of follow‐up.

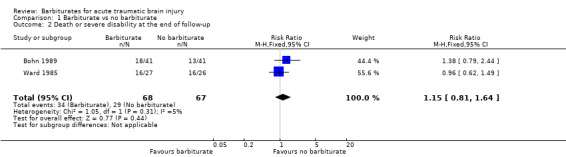

The effect of barbiturates on death or disability, measured using the Glasgow Outcome Scale, was available in two trials (Bohn 1989; Ward 1985). The pooled RR for death or disability was 1.15 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.64); there was no statistical heterogeneity. Analysis 1.2

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Barbiturate vs no barbiturate, Outcome 2 Death or severe disability at the end of follow‐up.

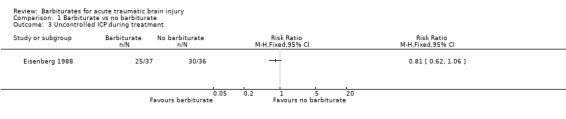

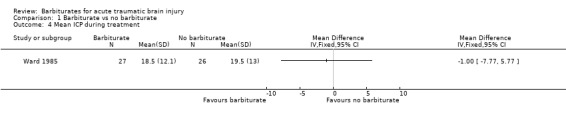

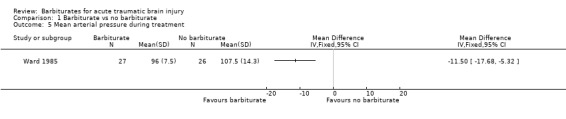

Two trials examined the effect of barbiturates on intracranial pressure (ICP). In the study by Eisenberg 1988 a smaller proportion of patients in the barbiturate group had uncontrolled ICP (68% versus 83%); the RR for uncontrolled ICP was 0.81 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.06) Analysis 1.3. Similarly, in the study by Ward 1985 mean ICP was lower in the barbiturate treated group Analysis 1.4, as was mean arterial pressure Analysis 1.5.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Barbiturate vs no barbiturate, Outcome 3 Uncontrolled ICP during treatment.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Barbiturate vs no barbiturate, Outcome 4 Mean ICP during treatment.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Barbiturate vs no barbiturate, Outcome 5 Mean arterial pressure during treatment.

Two trials (Eisenberg 1988; Ward 1985) examined the effect of barbiturates on the occurrence of hypotension. There was a substantial increase in the occurrence of hypotension in the barbiturate treated group (RR 1.80; 95% CI 1.19 to 2.70), with considerable statistical heterogeneity Analysis 1.6.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Barbiturate vs no barbiturate, Outcome 6 Hypotension during treatment.

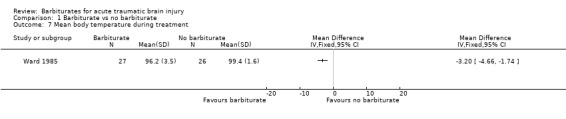

The trial by Ward 1985 examined the effect of barbiturate administration on mean body temperature. Mean body temperature was significantly lower in the barbiturate treated group Analysis 1.7.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Barbiturate vs no barbiturate, Outcome 7 Mean body temperature during treatment.

2. Barbiturate versus mannitol

Schwartz 1984 compared pentobarbital with mannitol for the control of ICP. At the end of follow‐up at one year following injury, there was no substantial difference in death between the two study groups (RR 1.21; 95% CI 0.75 to 1.94) Analysis 2.1. Pentobarbital was less effective than mannitol for control of raised ICP (RR 1.75; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.92) Analysis 2.2. Sixty‐eight per cent of patients in the pentobarbital treated group required a second drug for the treatment of raised intracranial pressure compared with 39% in the mannitol treated group.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Barbiturate vs Mannitol, Outcome 1 Death at the end of follow‐up (1 year).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Barbiturate vs Mannitol, Outcome 2 Uncontrolled ICP during treatment.

3. Pentobarbital versus thiopental

Pérez‐Bárcena 2008 compared the effect of pentobarbital or thiopental versus control ICP. At final follow‐up at six months following injury, the RR for death was 1.78 (95% CI 1.03 to 3.08) in favour of thiopental Analysis 3.1. Fewer patients had uncontrollable ICP with thiopental (RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.60) Analysis 3.3. There was no significant difference in the effects of pentobarbital versus thiopental for death or disability, as measured using the Glasgow Outcome Scale (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.94) Analysis 3.2, or hypotension (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.12) Analysis 3.4.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Pentobarbital vs Thiopental, Outcome 1 Death at the end of follow‐up (6 months).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Pentobarbital vs Thiopental, Outcome 3 Uncontrolled ICP during treatment.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Pentobarbital vs Thiopental, Outcome 2 Death or severe disability at the end of follow‐up (6 months).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Pentobarbital vs Thiopental, Outcome 4 Hypotension during treatment.

4. Pentobarbital versus etomidate

Levy 1995 compared the effect of pentobarbital with etomidate in the control of ICP, and on cardiac performance following head injury. The study was stopped after seven people were randomised, because all three people in the etomidate treated group developed renal compromise. The results of this study were not considered further.

Discussion

Barbiturates may reduce raised intracranial pressure (ICP) but there is no evidence that this is associated with a reduction in death or disability.

Barbiturates result in a substantial increase in the occurrence of hypotension in patients with severe brain injury. For every four patients treated with barbiturates, one will develop hypotension. Barbiturates also resulted in a significant fall in body temperature.

The correlation between raised ICP and disability is well established from clinical studies. However, cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) depends on both ICP and mean arterial blood pressure (CPP = mean arterial blood pressure ‐ mean ICP). The hypotensive effect of barbiturates is likely to offset the effect on cerebral perfusion pressure of any barbiturate‐related reduction in ICP.

Summary of main results

There is no evidence that barbiturates improve outcomes in people with acute brain injury. Barbiturate therapy results in a fall in blood pressure in one in four treated patients. The hypotensive effect of barbiturate therapy will offset any intracranial pressure lowering effect on cerebral perfusion pressure.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review was first published in 1997 and included six trials, one new trial was included in 2009. No new or ongoing studies were identified in the latest search in 2012. The review is based on a thorough search of medical literature and we believe the review is a complete compilation of the randomised controlled trials on this topic.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is no evidence that barbiturates improve outcomes in people with acute brain injury. Barbiturate therapy results in a fall in blood pressure in one in four treated patients. The hypotensive effect of barbiturate therapy will offset any intracranial pressure lowering effect on cerebral perfusion pressure.

Implications for research.

Further randomised controlled trials are required to assess the effect of barbiturates on death and quality of survival after acute brain injury.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 October 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The search has been updated to September 2012. We found no new studies. We substantively updated the manuscript to comply with new Cochrane reporting guidelines. We have included a full 'Risk of bias' assessment for the included studies according to Cochrane methods. As no ongoing studies were identified in 2012 the review will be updated again in 2015. |

| 26 October 2012 | New search has been performed | The search for studies has been updated to 26 September 2012. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1997 Review first published: Issue 3, 1997

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 July 2009 | New search has been performed | The report of one trial previously in 'ongoing studies' is now available (Pérez‐Bárcena 2008). The results of the trial have been included in the review. The results and discussion sections have been updated accordingly. |

| 5 May 2009 | New search has been performed | The search was updated to January 2008. No new trials were identified. The conclusions remain the same. |

| 17 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 15 March 2006 | New search has been performed | An updated search for new trials was conducted in March 2006. One ongoing trial (Pérez‐Bárcena 2005) was identified, the findings from which will be incorporated into the review when available. |

Acknowledgements

The Cochrane Injuries Group's Trials Search Co‐ordinators for developing the search strategy and running the searches.

The trial authors for replying to our requests for additional information (in some cases over 30 years following completion of the trial).

Appendices

Appendix 1. Original search strategy

This MEDLINE search strategy was used and was also adapted, as appropriate, for each of the other databases: CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library), EMBASE, National Research Register and Web of Science.

#1 explode Barbiturates / all subheadings #2 pentobarb* or phenobarb* or methohexital* or thiamyl* or thiopental* or amobarb* or mephobarb* or barbital* or hexobarb* or murexide* or primidone* or secobarb* or thiobarb* #3 #1 or #2 #4 explode Craniocerebral Trauma/ all subheadings #5 ((injur* or trauma* or lesion* or damage* or wound* or destruction* oedema* or edema* or fracture* or contusion* or concus* or commotion* or pressur*) and (head or crani* or capitis or brain* or forebrain* or skull* or hemisphere or intracran* or orbit* or cerebr*)) #6 #4 or #5 #7 RCT filter #8 #6 and #7

Appendix 2. Search strategy: latest update

CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 9)

#1MeSH descriptor Craniocerebral Trauma explode all trees #2MeSH descriptor Cerebrovascular Trauma explode all trees #3MeSH descriptor Brain Edema explode all trees #4(brain or cerebral or intracranial) near3 (oedema or edema or swell*) #5MeSH descriptor Glasgow Coma Scale explode all trees #6MeSH descriptor Glasgow Outcome Scale explode all trees #7MeSH descriptor Unconsciousness explode all trees #8glasgow near3 (coma or outcome) near3 (score or scale) #9(Unconscious* or coma* or concuss* or 'persistent vegetative state') near 3 (injur* or trauma* or damag* or wound* or fracture*) #10"Rancho Los Amigos Scale" #11(head or crani* or cerebr* or capitis or brain* or forebrain* or skull* or hemispher* or intra‐cran* or inter‐cran*) near3 (injur* or trauma* or damag* or wound* or fracture* or contusion*) #12Diffuse near3 axonal near3 injur* #13(head or crani* or cerebr* or brain* or intra‐cran* or inter‐cran*) near3 (haematoma* or hematoma* or haemorrhag* or hemorrhag* or bleed* or pressure) #14(#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13)

Cochrane Injuries Group Specialised Register (26 Sept 2012)

Barbiturate* or pentobarb* or phenobarb* or methohexital* or thiamyl* or thiopent* or amobarb* or mephobarb* or barbital* or hexobarb* or murexide* or primidone* or secobarb* or thiobarb* or amobarbital or barbital or hexobarbital or mephobarbital or methohexital or murexide or pentobarbital or Phenobarbital or secobarbital or thiobarbiturate* or phenytoin* or amylobarb*

PubMed (26 Sept 2012)

((((((pentobarb* OR phenobarb* OR methohexital* OR thiamyl* OR thiopental* OR amobarb* OR mephobarb* OR barbital* OR hexobarb* OR murexide* OR primidone* OR secobarb* OR thiobarb*)) OR (((((((((((((pentobarb*[Title/Abstract]) OR phenobarb*[Title/Abstract]) OR methohexital*[Title/Abstract]) OR thiamyl*[Title/Abstract]) OR thiopental*[Title/Abstract]) OR amobarb*[Title/Abstract]) OR mephobarb*[Title/Abstract]) OR barbital*[Title/Abstract]) OR hexobarb*[Title/Abstract]) OR murexide*[Title/Abstract]) OR primidone*[Title/Abstract]) OR secobarb*[Title/Abstract]) OR thiobarb*[Title/Abstract]))) OR ("Barbiturates"[Mesh]))) AND ((((((((((((("Craniocerebral Trauma"[Mesh])) OR "Brain Edema"[Mesh]) OR "Glasgow Coma Scale"[Mesh]) OR "Glasgow Outcome Scale"[Mesh]) OR "Unconsciousness"[Mesh]) OR "Cerebrovascular Trauma"[Mesh])) OR ((((((((haematoma*[Title/Abstract]) OR hematoma*[Title/Abstract]) OR haemorrhag*[Title/Abstract]) OR hemorrhage*[Title/Abstract]) OR bleed*[Title/Abstract]) OR pressure[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((((head[Title/Abstract]) OR cranial[Title/Abstract]) OR cerebral[Title/Abstract]) OR brain*[Title/Abstract]) OR intra‐cranial[Title/Abstract]) OR inter‐cranial[Title/Abstract]))) OR (((((diffuse axonal injury[Title/Abstract]) OR diffuse axonal injuries[Title/Abstract]) OR persistent vegetative state[Title/Abstract]) OR glasgow outcome scale[Title/Abstract]) OR glasgow coma scale[Title/Abstract])) OR ((((((((((((((((injury*[Title/Abstract]) OR injuries[Title/Abstract]) OR trauma[Title/Abstract]) OR damage[Title/Abstract]) OR damaged[Title/Abstract]) OR wound*[Title/Abstract]) OR fracture*[Title/Abstract]) OR contusion*[Title/Abstract]) OR haematoma*[Title/Abstract]) OR hematoma*[Title/Abstract]) OR Haemorrhag*[Title/Abstract]) OR hemorrhag*[Title/Abstract]) OR bleed*[Title/Abstract]) OR pressure[Title/Abstract])) AND (((unconscious*[Title/Abstract]) OR coma*[Title/Abstract]) OR concuss*[Title/Abstract])))) AND ((placebo[Title/Abstract]) OR drug therapy[MeSH Subheading] OR randomly[Title/Abstract] OR trials[Title/Abstract] OR group[Title/Abstract] OR randomized[Title/Abstract] OR randomised[Title/Abstract] OR controlled clinical trial[Publication Type] OR randomized controlled trial[Publication Type] NOT ((animals[MeSH Terms]) NOT humans[MeSH Terms]))) MEDLINE (Ovid SP) September Week 2 2012 1. exp Craniocerebral Trauma/ 2. exp Brain Edema/ 3. exp Glasgow Coma Scale/ 4. exp Glasgow Outcome Scale/ 5. exp Unconsciousness/ 6. exp Cerebrovascular Trauma/ 7. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or capitis or brain$ or forebrain$ or skull$ or hemispher$ or intra‐cran$ or inter‐cran$) adj3 (injur$ or trauma$ or damag$ or wound$ or fracture$ or contusion$)).ab,ti. 8. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or brain$ or intra‐cran$ or inter‐cran$) adj3 (haematoma$ or hematoma$ or haemorrhag$ or hemorrhag$ or bleed$ or pressure)).ti,ab. 9. (Glasgow adj3 (coma or outcome) adj3 (scale$ or score$)).ab,ti. 10. "rancho los amigos scale".ti,ab. 11. ("diffuse axonal injury" or "diffuse axonal injuries").ti,ab. 12. ((brain or cerebral or intracranial) adj3 (oedema or edema or swell$)).ab,ti. 13. ((unconscious$ or coma$ or concuss$ or 'persistent vegetative state') adj3 (injur$ or trauma$ or damag$ or wound$ or fracture$)).ti,ab. 14. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 15. Barbiturates/ 16. barbiturates/ or amobarbital/ or barbital/ or hexobarbital/ or mephobarbital/ or methohexital/ or murexide/ or pentobarbital/ or phenobarbital/ or secobarbital/ or thiobarbiturates/ 17. (pentobarb* or phenobarb* or methohexital* or thiamyl* or thiopental* or amobarb* or mephobarb* or barbital* or hexobarb* or murexide* or primidone* or secobarb* or thiobarb*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, protocol supplementary concept, rare disease supplementary concept, unique identifier] 18. 15 or 16 or 17 19. 14 and 18 20. randomi?ed.ab,ti. 21. randomized controlled trial.pt. 22. controlled clinical trial.pt. 23. placebo.ab. 24. clinical trials as topic.sh. 25. randomly.ab. 26. trial.ti. 27. 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 28. (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 29. 27 not 28 30. 19 and 29

EMBASE (Ovid SP) to 2012 Week 38

1. exp brain injury/ 2. exp brain edema/ 3. exp Glasgow coma scale/ 4. exp Glasgow outcome scale/ 5. exp Rancho Los Amigos scale/ 6. exp unconsciousness/ 7. ((brain or cerebral or intracranial) adj3 (oedema or edema or swell$)).ab,ti. 8. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or capitis or brain$ or forebrain$ or skull$ or hemispher$ or intra‐cran$ or inter‐cran$) adj3 (injur$ or trauma$ or damag$ or wound$ or fracture$ or contusion$)).ab,ti. 9. (Glasgow adj3 (coma or outcome) adj3 (scale$ or score$)).ab,ti. 10. Rancho Los Amigos Scale.ab,ti. 11. ((unconscious$ or coma$ or concuss$ or 'persistent vegetative state') adj3 (injur$ or trauma$ or damag$ or wound$ or fracture$)).ti,ab. 12. Diffuse axonal injur$.ab,ti. 13. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or brain$ or intra‐cran$ or inter‐cran$) adj3 (haematoma$ or hematoma$ or haemorrhag$ or hemorrhag$ or bleed$ or pressure)).ab,ti. 14. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 15. (pentobarb* or phenobarb* or methohexital* or thiamyl* or thiopental* or amobarb* or mephobarb* or barbital* or hexobarb* or murexide* or primidone* or secobarb* or thiobarb*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] 16. barbituates.mp. 17. 15 or 16 18. 14 and 17 19. exp Randomized Controlled Trial/ 20. exp controlled clinical trial/ 21. exp controlled study/ 22. randomi?ed.ab,ti. 23. placebo.ab. 24. *Clinical Trial/ 25. exp major clinical study/ 26. randomly.ab. 27. (trial or study).ti. 28. 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 29. exp animal/ not (exp human/ and exp animal/) 30. 28 not 29 31. 18 and 30 32. limit 31 to exclude medline journals PsycINFO (Ovid SP) to September Week 3 2012 and PsycEXTRA (Ovid SP) to September 10, 2012 1. exp Head Injuries/ 2. exp Brain Damage/ 3. exp Traumatic Brain Injury/ 4. exp Brain Concussion/ 5. (Unconscious* or coma* or concuss* or "persistent vegetative state").mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures] 6. ((head or crani* or cerebr* or capitis or brain* or forebrain* or skull* or hemispher* or intra‐cran* or inter‐cran*) adj3 (injur* or trauma* or damag* or wound* or fracture* or contusion*)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures] 7. ((head or crani* or cerebr* or brain* or intra‐cran* or inter‐cran*) adj3 (haematoma* or hematoma* or haemorrhag* or hemorrhag* or bleed* or pressure)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures] 8. exp Coma/ 9. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 10. barbiturates/ or amobarbital/ or barbital/ or hexobarbital/ or mephobarbital/ or methohexital/ or murexide/ or pentobarbital/ or phenobarbital/ or secobarbital/ or thiobarbiturates/ 11. (pentobarb* or phenobarb* or methohexital* or thiamyl* or thiopental* or amobarb* or mephobarb* or barbital* or hexobarb* or murexide* or primidone* or secobarb* or thiobarb*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures] 12. 10 or 11 13. 9 and 12 ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index (SCI) to Sept 26, 2012 ISI Web of Science: Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science (CPCI‐S) to Sept 26, 2012

#1 TS=((head OR brain OR cranial OR cerebral OR brain OR intra‐cranial OR inter‐cranial) SAME (haematoma* OR hematoma* OR haemorrhag* OR hemorrhage* OR bleed* OR pressure OR unconscious* OR coma* OR concuss* OR injury* OR injuries OR trauma OR damage OR damaged OR wound* OR fracture* OR contusion* OR bleed*)) #2 TS=((clinical OR control* OR placebo OR random OR randomised OR randomized OR randomly OR random order OR random sequence OR random allocation OR randomly allocated OR at random) SAME (trial* or group* or study or studies or placebo or controlled)) NOT TS=(Rat* or rodent* or animal* or mice or murin* or dog* or canine* or cat* or feline* or rabbit* or guinea pig*) #3 #1 AND #2 #4 TS=Barbiturate* or pentobarb* or phenobarb* or methohexital* or thiamyl* or thiopent* or amobarb* or mephobarb* or barbital* or hexobarb* or murexide* or primidone* or secobarb* or thiobarb* or amobarbital or barbital or hexobarbital or mephobarbital or methohexital or murexide or pentobarbital or Phenobarbital or secobarbital or thiobarbiturate* or phenytoin* or amylobarb*

#5 #3 AND #4

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Barbiturate vs no barbiturate.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death at the end of follow‐up | 3 | 208 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.81, 1.47] |

| 2 Death or severe disability at the end of follow‐up | 2 | 135 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.81, 1.64] |

| 3 Uncontrolled ICP during treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Mean ICP during treatment | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Mean arterial pressure during treatment | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 Hypotension during treatment | 2 | 126 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.80 [1.19, 2.70] |

| 7 Mean body temperature during treatment | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 2. Barbiturate vs Mannitol.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death at the end of follow‐up (1 year) | 1 | 59 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.75, 1.94] |

| 1.1 Haematoma | 1 | 29 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.8 [0.36, 1.80] |

| 1.2 No haematoma | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.63 [0.91, 2.94] |

| 2 Uncontrolled ICP during treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 3. Pentobarbital vs Thiopental.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death at the end of follow‐up (6 months) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Death or severe disability at the end of follow‐up (6 months) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Uncontrolled ICP during treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Hypotension during treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bohn 1989.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | Children (age 1‐18 years) with severe head injury (GCS ≤ 7). 82 people were included in the trial, 41 in each study group. |

|

| Interventions | High‐dose phenobarbitone (loading dose 50 mg/kg followed by 20 mg/kg/day) or no phenobarbitone. | |

| Outcomes | Death and GOS were measured at the time of hospital discharge and at 6 months, ICP, sepsis. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Review authors' judgement: Experiencing a head injury occurs randomly. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Correspondence with author in 1997. Quote: "Patients allocated to treatment group according to which ICU physician was on duty." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Participants | Low risk | Review authors' judgement: Low risk as people had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 7 or less and therefore had reduced cognitive function. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Treating physicians | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcome data on mortality and disability are reported in full. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Review authors' judgement: Not assessed as we were unable to obtain the study protocol. The authors report there was a study protocol. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Review authors' judgement: None known. |

Eisenberg 1988.

| Methods | Multi‐centre randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | People with severe head injury (GCS 4 to 7). Aged 15‐50 years. Elevated ICP refractory to conventional management. 73 people took part in the study: 37 received barbiturate treatment in addition to standard care and 36 received standard care only. |

|

| Interventions | Pentobarbital: Loading dose 10 mg/kg over 30 minutes, 5 mg/kg every 1hr for three hours. Maintenance dose 1 mg/kg/hr with serum level monitoring. Control: standard care. |

|

| Outcomes | Control of raised intracranial pressure. With regard to the primary outcome criteria, there were only two possibilities: (1) Treatment success ‐ declared when a person's ICP fell below 20 mmHg (or 15 mmHg for those classified as "skull opened"); (2) Treatment failure ‐ declared when ICP became uncontrollable, or the patient developed a unilateral dilated pupil, cardiovascular collapse, or died. Mortality and morbidity according to GOS score at 30 days and 6 months. |

|

| Notes | The study took place at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York; Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; University of California at San Diego; University of Texas Health Sciences Center, Houston; and the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. People were recruited between December 1982 and December 1985. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Patients were randomised (fixed block size) by centre, according to the last available GCS score (4 to 7) using sealed opaque envelopes." pp.16‐17 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...using sealed opaque envelopes." p.17 |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Participants | Low risk | Review authors' judgement: Low risk as people had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of less than 7 and therefore had reduced cognitive function. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Treating physicians | High risk | Review authors' judgement: There is no mention of blinding of the treating physicians. Figure 1 (p.17) The barbiturate group received the additional intervention at regular intervals, so the treating physicians were aware of the treatment. Correspondence with the author in 2012. Quote: "It was a blinded study." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Review authors' judgement: High risk of bias as no details provided as to who was blinded in the original report or through correspondence. Correspondence with the author in 2012. Quote: "It was a blinded study." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Complete outcome data were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Review authors' judgement: It was a multi‐centre study and the authors wrote it was "coordinated and monitored by investigators from the University of Texas School of Public Health, Houston, and from the NINCDS Division of Stroke and Trauma" (p.16) so there must have been a protocol. Correspondence with the author in 2012 clarified there was a study protocol but the university's data storage policy is to destroy records after seven years and so the protocol is no longer available. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | None known. |

Levy 1995.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Trial stopped prematurely because of serious adverse effects of propylene glycol carrier agent. Seven people were randomised in total: pentobarbital 4, etomidate 3. Of the four traumatic brain injury participants, three received pentobarbital and one received etomidate. |

|

| Participants | People with manifest raised ICP refractory to standard medical therapy, as the result of isolated head injury or ischaemic injury. | |

| Interventions | Pentobarbital: 2.5 mg/kg i.v. every 15 minutes for one hour, followed by 10 mg/kg every hour for four hours as a load. Maintenance by continuous infusion of 1.5 mg/kg/hr. Etomidate: 0.30 mg/kg i.v. load followed by a continuous infusion rate of 0.02 mg/kg/min. | |

| Outcomes | ICP and mortality during the trial. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...able to randomize seven patients in a blinded fashion to receive either etomidate or pentobarbital." p.364 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...able to randomize seven patients in a blinded fashion to receive either etomidate or pentobarbital." p.364 |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Participants | Low risk | Quote: "All patients had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of less than seven and were free of systemic disease." p.364 Review authors' judgement: Low risk as people had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of less than 7 and therefore had reduced cognitive function. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Treating physicians | High risk | Quote: "All records were kept by the neurosurgical trauma team...." p.364 Review authors' judgement: There is no indication that the treating physicians were blind to the treatments given as the time of treatment and doses given were different between study groups. The treating physicians were also recording information about the people receiving treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "All records were kept by the neurosurgical trauma team and were evaluated by the anesthesia team who were blinded to the treatment group." p.364 |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Complete outcome data were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Review authors' judgement: The study report mentions a study protocol. We were unable to obtain a copy of the study protocol in order to assess selective reporting. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | None known. |

Pérez‐Bárcena 2008.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | People with severe traumatic brain injury (post resuscitation GCS less than or equal to 8) and raised ICP (> 20 mmHg) refractory to first level measures. Exclusion criteria were age < 15 or > 76 years, pregnancy, a GCS score of 3 and neurological signs of brain death, barbiturate allergy or history of severe cardiac ventricular dysfunction. 44 people were included in the study, 22 to each treatment group. |

|

| Interventions | Pentobarbital versus thiopental. Quote: "Pentobarbital was administered in accordance with the protocol established by Eisenberg and coworkers (Eisenberg 1988), using a loading dose of 10 mg/kg over 30 minutes followed by a continuous perfusion of 5 mg/kg per hour for 3 hours. This was followed by a maintenance dosage of 1 mg/kg per hour." Quote: "Thiopental was administered in the form of a 2 mg/kg bolus administered over 20 seconds. If the ICP was not lowered to below 20 mmHg, then the protocol permitted a second bolus of 3 mg/kg, which could be readministered at 5 mg/kg if necessary to reduce persistently elevated ICP. The maintenance dosage was an infusion of thiopental at a rate of 3 mg/kg per hour." Quote: "In both treatment groups, for cases in which the maintenance dosage did not achieve the reduction in ICP to below the 20 mmHg threshold, the maintenance dosage for both drugs could be increased by 1 mg/Kg per hour, while looking for electroencephalographic burst suppression or even the flat pattern, in order to ensure that different doses of the two barbiturates were equipotent." |

|

| Outcomes | Mortality and disability at 6 months following the injury, and uncontrolled ICP and hypotension during treatment. | |

| Notes | The study was conducted at Son Dureta University Hospital in Palma de Mallorca, Spain. People were recruited between May 2002 and July 2007. The study was funded by a public grant from the Spanish government's Fondo de Investigacion Sanitaria (FIS PI020642). |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was based on a computer‐generated list that intercollated the two drugs." p.3/10 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Allocation was done by the intensive care unit physician who was on duty, once the patient had been found to meet the inclusion criteria..." p.3/10 |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Participants | Low risk | Review authors' judgement: The participants were blind to their treatment allocation because they were unconscious. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Treating physicians | High risk | Quote: "The study was not blinded because it was difficult for us to mask treatment; thiopental is liophylized for administration and pentobarbital is not." p.3/10 |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Quote: "Data collection and patient follow up were conducted by the same investigator (JPB)." p.3/10 |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: "In both groups one case was missing from the 6‐month follow up analysis." p.6/10 |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Review authors' judgement: There is no specific mention of a study protocol but the text is written in a manner which implies that there was one. We were unable to obtain a copy of the study protocol to assess selective reporting. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Review authors' judgement: None known. |

Saul 1982.

| Methods | The study is described as a randomised controlled trial, but details of the randomisation are not presented. The study authors were contacted in 1997 but no study data are available. 26 people participated in the trial. |

|

| Participants | People with severe head injury (GCS ≤ 7). Aged 14‐81 years. All had ICP monitoring. Patients were randomised if ICP reached 25 mmHg for 10 minutes at rest. | |

| Interventions | Pentobarbital: Loading dose 10 mg/kg/hr for 4 hours. Maintenance 1.6 mg/kg/hr. | |

| Outcomes | Not specified. | |

| Notes | The study was performed during 1979‐80. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "...the patients were randomized into a controlled barbiturate therapy study." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Participants | Low risk | Not stated. Review authors' judgement: Low risk as people had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of less than 7 and therefore had reduced cognitive function. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Treating physicians | High risk | Not stated. Review authors' judgement: There is no indication that the treating physicians were blind to the treatments given as the time of treatment and doses given were different between study groups. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Review authors' judgement: The study outcomes are not stated. The number of deaths is reported, but no information is available for people who survived. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Review authors' judgement: The study report mentions a study protocol. We were unable to obtain a copy of the study protocol in order to assess selective reporting. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | ‐ |

Schwartz 1984.

| Methods | Multi‐centre randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | People with severe head injury (GCS ≤ 7). Raised ICP (25 torr for more than 15 minutes). 59 people were randomised, stratification was by presence of haematoma. No haematoma (30 people): Pentobarbital 13, Mannitol 17 Haematoma (29 people): Pentobarbital 15, Mannitol 14 |

|

| Interventions | Pentobarbital versus mannitol. Quote: "Prior to randomisation, people thought to have (but not yet proven to have) raised ICP were given a rapid infusion of 20% mannitol solution." Quote: "All patients were given dexamethasone in an initial dose of 10 mg IV followed by 4 mg q6h." Pentobarbital: Quote: "Loading dose up to 10mg/kg. Maintenance 0.5‐3 mg/kg/hr with serum level monitoring, provided that cerebral perfusion pressure remained above 50 torr. Additional increments of pentobarbital were given to maintain the intracranial pressure at less than 20 torr. The maximum suggested barbiturate level was 45 mg/L. When necessary, dopamine plus volume infusions were administered to raise the systemic arterial blood pressure and hence the cerebral perfusion to at least 50 torr." Mannitol: Quote: "20% solution initial dose 1 g/kg with serum osmolality monitoring. Additional increments of mannitol, usually less than 350cc. were given as required for continued intracranial hypertension to maintain the intracranial pressure at less than 20 torr, provided that serum osmolality did not exceed 320 m0s/L." |

|

| Outcomes | Mortality at 3 and 12 months following injury, and uncontrolled ICP and mean of the worst CPP during treatment. | |

| Notes | Four of the major teaching hospitals at the University of Toronto, Canada recruited people with TBI. The study recruited from April 1980 through October 1982. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...determined by a random number generator." p.436 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Mechanism of randomisation was the opening of a serially numbered, sealed envelope taken from one of two packages of envelopes, one for patients who had had intracranial hematomas removed and one for those who developed raised intracranial pressure from brain injury alone." p.436 Quote: "The physician caring for the patient could not predict which drug was to be prescribed as initial treatment prior to opening the envelope." p.436 |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Participants | Low risk | Review authors' judgement: Low risk as people had a severe head injury with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of less than 7 and therefore had reduced cognitive function. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Treating physicians | High risk | Correspondence with the author in 2012. Quote: "... the treating physicians were aware of the patients' allocations...." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Correspondence with the author in 2012. Quote: "The treatment records were reviewed which resulted in the reviewers knowing the allocation of the patient. Because the intracranial pressure measurements were numerical they were not subject to much debate." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Complete outcome data were reported for all outcomes used in this review. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Correspondence with the author in 2012. Quote: "The study protocol is long gone, but the experiment is described in the publication." |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | None known. |

Ward 1985.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | Consecutive patients with head injuries over the age of 12 years who had either an acute intradural haematoma or no mass lesion whose best motor response was abnormal flexion or extension.

Treatment started after head injury regardless of ICP. 53 people were included in this study; 27 in the barbiturate group and 26 in the control group. |

|

| Interventions | Pentobarbital: Loading dose 5‐10 mg/kg until burst‐suppression on EEG. Maintenance 1‐3 mg/kg with serum level monitoring. | |

| Outcomes | ICP and body temperature during the first four days of treatment, and morbidity and mortality one year following injury. | |

| Notes | The study took place between January 1979 and April 1983 in Virginia, USA. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...a randomised, controlled trial of prophylactic pentobarbital therapy..." p.383, abstract |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...the cases were randomly drawn for placement into a control group and a barbiturate‐treated group." p.384 |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Participants | Low risk | Quote: "head‐injured patients over the age of 12 years who had either an acute intradural hematoma (subdural and/or intracerebral, large enough to warrant surgical decompression) or no mass lesion but whose best motor response was abnormal flexion or extension." p.384 Review authors' judgement: The patients were unaware of their treatment allocation |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) Treating physicians | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Complete outcome data were reported for all outcomes used in this review. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Review authors' judgement: The study report mentions a study protocol. We were unable to obtain a copy of the study protocol in order to assess selective reporting. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | None known. |

CPP: cerebral perfusion pressure GOS = Glasgow outcome score GCS = Glasgow coma score ICP= Intracranial pressure ICU = Intensive care unit EEG = Electroencephalograph TBI: traumatic brain injury

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Yano 1981 | Published report states that "The 128 patients were divided into two groups randomly." However, authors when contacted could not confirm random allocation ‐ and the study design was a retrospective case series. |

Differences between protocol and review

There was no protocol for the original version of this review, which was published in 1997. According to IR, the review was conducted according to the methods described in version 3 of the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook that was published in 1996.

The original review used the scale developed by Schultz 1995 to assess allocation concealment only. As the methods of The Cochrane Collaboration have been updated, the review is now reported according to MECIR 2012 guidelines and the 'Risk of bias' tool has been used instead.

In the first version of the review "The major outcome data sought were numbers of deaths, and numbers of people disabled at the end of the study period. Disability was assessed using the Glasgow Outcome Scale." We have selected death at final follow‐up as the primary outcome for this and all future updates.

Contributions of authors

IR wrote all versions of the review through to May 2009. Data extraction was checked by the Cochrane Injuries Group editorial team prior to publication.

ES and IR updated the review in July 2009. Both authors approved the final version of the update.

For the 2012 update both ES and IR screened the search results. ES re‐screened all previous search results (248 citations). ES updated the 'Risk of bias' tables, checked the data (they were correct) and edited the manuscript according to the Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews guidelines. IR and ES agreed on the final version of the manuscript.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

NHS Research & Development Programme: Maternal and Child Health, UK.

1997 version

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Bohn 1989 {unpublished data only}

- Bohn DJ, Swan P, Sides C, Hoffman H. High‐dose barbiturate therapy in the management of severe paediatric head injury: a randomised controlled trial. Critical Care Medicine 1989;S118:17. [Google Scholar]

Eisenberg 1988 {published data only}

- Eisenberg HM. Protocol request [personal communication]. Email to: E Sydenham 12 November 2012.

- Eisenberg HM, Frankowski RF, Contant CF, Marshall LF, Walker MD. High dose barbiturate control of elevated intracranial pressure in patients with severe head injury. Journal of Neurosurgery 1988;69:15‐23. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Levy 1995 {published data only}

- Levy ML, Aranda M, Zelman V, Giannotta SL. Propylene glycol toxicity following continuous etomidate infusion for the control of refractory cerebral edema. Neurosurgery 1995;37:363‐71. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pérez‐Bárcena 2008 {published data only}

- Perez‐Barcena J, Llompart‐Pou JA, Homar J, Abadal JM, Raurich JM, Frontera G, et al. Pentobarbital versus thiopental in the treatment of refractory intracranial hypertension in patients with traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Critical Care 2008;12(4):R112. [DOI: 10.1186/cc6999; http://ccforum.com/content/12/4/R112] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez‐Bárcena J, Barceló B, Homar J, Abadal JM, Molina FJ, Pena A, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of pentobarbital and thiopental in patients with refractory intracranial hypertension. Preliminary report of 20 patients. Neurocirugia (Astur) 2005;16(1):5‐12. [DOI: 10.1186/cc6999] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Saul 1982 {unpublished data only}

- Saul TG, Ducker TB. Effects of intracranial pressure monitoring and aggressive treatment on mortality in severe head injury. Journal of Neurosurgery 1982;56:498‐503. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schwartz 1984 {published data only}

- Schwartz ML. Protocol request [personal communication]. Email to: E Sydenham 11 November 2012.

- Schwartz ML, Tator CH, Rowed DW, Reid SR, Meguro K, Andrews DF. The University of Toronto Head Injury Treatment Study: A prospective randomized comparison of pentobarbital and mannitol. Canadian Journal of Neurological Science 1984;11:434‐40. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ward 1985 {published data only}

- Ward JD, Becker DP, Miller JD, Choi SC, Marmarou A, Wood C, et al. Failure of prophylactic barbiturate coma in the treatment of severe head injury. Journal of Neurosurgery 1985;62:383‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JD, Miller JD, Choi SC, Marmarou A, Lutz, HA, Newlon PG, et al. Failure of prophylactic barbiturate coma in the prevention of death due to uncontrolled intracranial hypertension in patients with severe head injury. In: Miller JD, Teasdale GM, Rowan JO, Galbraith SL, Mendelow AD editor(s). Intracranial Pressure. Vol. VI, Springer‐Verlag, 1986:766‐8. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Yano 1981 {published data only}

- Yano M, Kobayashi S, Aruga T, Yamamoto Y, Ohtsuka T, Nishimura N. Barbiturate overloading in 85 cases of severe head injury. Neurologia Medico‐Chirurgica 1981;21:163‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Ghajar 1995

- Ghajar J, Hariri RJ, Narayan RK, Iacono LA, Firlik K, Patterson RH. Survey of critical care management of comatose, head‐injured patients in the United States. Critical Care Medicine 1995;23(3):560‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Jeevaratnam 1996

- Jeevaratnam DR, Menon DK. Survey of intensive care of severely head injured patients in the United Kingdom. BMJ 1996;312:944‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jennet 1975

- Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. A practical scale. Lancet 1975;1:480‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MECIR 2012

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR): Standards for the reporting of new Cochrane Intervention Reviews. Cochrane Editorial Unit 2012. [www.editorial‐unit.cochrane.org/mecir]

Pickard 1993

- Pickard JD, Czosnyka M. Management of raised intracranial pressure. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 1993;56:845‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schultz 1995

- Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical Evidence of Bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273:408‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shapiro 1979

- Shapiro MH, Wyte SR, Loeser J. Barbiturate augmented hypothermia for reduction of persistent intracranial hypertension. Journal of Neurosurgery 1979;40:90‐100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Roberts 1997

- Roberts I. Barbiturates in the management of severe brain injury. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1997, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000033] [DOI] [Google Scholar]