Abstract

Background

Misoprostol (Cytotec, Searle) is a prostaglandin E1 analogue widely used for off‐label indications such as induction of abortion and of labour. This is one of a series of reviews of methods of cervical ripening and labour induction using standardised methodology.

Objectives

To determine the effects of vaginal misoprostol for third trimester cervical ripening or induction of labour.

Search methods

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (November 2008) and bibliographies of relevant papers. We updated this search on 15 February 2012 and added the results to the awaiting classification section.

Selection criteria

Clinical trials comparing vaginal misoprostol used for third trimester cervical ripening or labour induction with placebo/no treatment or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of labour induction methods.

Data collection and analysis

We developed a strategy to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. This involved a two‐stage method of data extraction.

We used fixed‐effect Mantel‐Haenszel meta‐analysis for combining dichotomous data.

If we identified substantial heterogeneity (I² greater than 50%), we used a random‐effects method.

Main results

We included 121 trials. The risk of bias must be kept in mind as only 13 trials were double blind.

Compared to placebo, misoprostol was associated with reduced failure to achieve vaginal delivery within 24 hours (average relative risk (RR) 0.51, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.37 to 0.71). Uterine hyperstimulation, without fetal heart rate (FHR) changes, was increased (RR 3.52 95% CI 1.78 to 6.99).

Compared with vaginal prostaglandin E2, intracervical prostaglandin E2 and oxytocin, vaginal misoprostol was associated with less epidural analgesia use, fewer failures to achieve vaginal delivery within 24 hours and more uterine hyperstimulation. Compared with vaginal or intracervical prostaglandin E2, oxytocin augmentation was less common with misoprostol and meconium‐stained liquor more common.

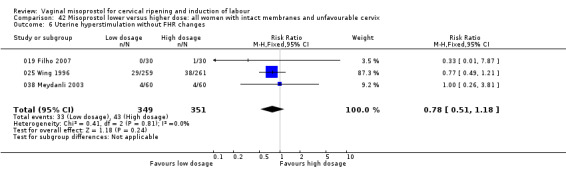

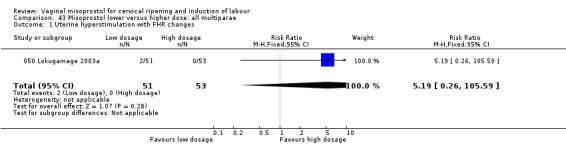

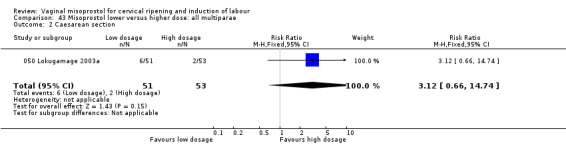

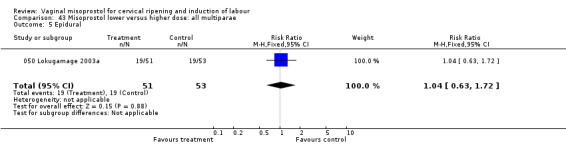

Lower doses of misoprostol compared to higher doses were associated with more need for oxytocin augmentation and less uterine hyperstimulation, with and without FHR changes.

We found no information on women's views.

Authors' conclusions

Vaginal misoprostol in doses above 25 mcg four‐hourly was more effective than conventional methods of labour induction, but with more uterine hyperstimulation. Lower doses (25 mcg four‐hourly or less) were similar to conventional methods in effectiveness and risks. The authors request information on cases of uterine rupture known to readers. The vaginal route should not be researched further as another Cochrane review has shown that the oral route of administration is preferable to the vaginal route. Professional and governmental bodies should agree guidelines for the use of misoprostol, based on the best available evidence and local circumstances.

[Note: The 27 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Cervical Ripening; Labor, Induced; Administration, Intravaginal; Misoprostol; Misoprostol/administration & dosage; Oxytocics; Oxytocics/administration & dosage; Pregnancy Trimester, Third; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Vaginal misoprostol is effective in inducing labour but more research is needed on safety

Sometimes it is necessary to bring on labour artificially because of safety concerns for the mother or baby. Misoprostol is a hormone given by insertion through the vagina or rectum, or by mouth to ripen the cervix and bring on labour. The review of 121 trials found that larger doses of misoprostol are more effective than prostaglandin and that oxytocin is used in addition less often. However, misoprostol also increases hyperstimulation of the uterus. With smaller doses, the results are similar to other methods. The trials reviewed are too small to determine whether the risk of rupture of the uterus is increased. More research is needed into the safety and best dosages of misoprostol. Another Cochrane review has shown that the oral route of administration is preferable to the vaginal route.

Background

Sometimes it is necessary to bring on labour artificially because of safety concerns for the mother or baby. This review is one of a series of reviews of methods of labour induction using a standardised protocol. For more detailed information on the rationale for this methodological approach, please refer to the currently published 'generic' protocol (Hofmeyr 2009). The generic protocol describes how a number of standardised reviews will be combined to compare various methods of preparing the cervix of the uterus and inducing labour.

The main problems experienced during induction of labour are ineffective labour, and excessive uterine activity which may cause fetal distress. Both problems may lead to an increased risk of caesarean section. Methods of induction of labour include administration of oxytocin, prostaglandins, prostaglandin analogues and smooth muscle stimulants such as herbs or castor oil (Mitri 1987), or mechanical methods such as digital stretching of the cervix and sweeping of the membranes, hygroscopic cervical dilators, extra‐amniotic balloon catheters, artificial rupture of the membranes, and nipple stimulation.

Standardised 'scoring' of the cervix prior to labour induction has been recommended (Bishop 1964). Oxytocin has the disadvantage of a high failure rate when the cervix is unfavourable (low cervical score), and requiring monitored continuous intravenous infusion.

Artificial rupture of membranes is also less effective or may not be possible when the cervix is unfavourable. It may increase the risk of infection if labour does not proceed promptly. Rupture of membranes may also increase the vertical transmission of specific maternal infections such as HIV.

Unsuccessful labour induction is most likely when the cervix is unfavourable and, in this circumstance, prostaglandin preparations have proved to be beneficial (Keirse 1993; MacKenzie 1997). Those prostaglandins that have been registered for cervical ripening and labour induction are expensive and unstable, requiring refrigerated storage. Uterine hyperstimulation has been identified as a particular problem during labour induction with prostaglandins, and has been treated with tocolysis (Egarter 1990).

Misoprostol (Cytotec, Searle) is a methyl ester of prostaglandin E1 additionally methylated at C‐16 and is marketed for use in the prevention and treatment of peptic ulcer disease caused by prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors. It is inexpensive, easily stored at room temperature and has few systemic side effects. It is rapidly absorbed orally and vaginally. The reported mean peak serum misoprostol acid following oral administration was 227 pg/ml versus vaginal route 165 pg/ml; the times to peak levels were 34 versus 80 minutes. Vaginally absorbed serum levels are more prolonged (Zieman 1997). Irrespective of serum levels, vaginal misoprostol may have locally mediated effects.

Misoprostol has been shown in several studies to be an effective myometrial stimulant of the pregnant uterus, selectively binding to EP‐2/EP‐3 prostanoid receptors (Senior 1993).

Misoprostol has been used widely for obstetric and gynaecological indications despite the fact that it has not been registered for such use. It has therefore not undergone the systematic testing for appropriate dosage and safety required for registration.

Misoprostol is an effective abortifacient, both alone and following pretreatment with mifepristone (Norman 1991). Its widespread use in Brazil (Costa 1993) resulted in the identification of teratogenic effects (Fonseca 1991).

Use of misoprostol for second trimester termination of pregnancy has been associated with uterine rupture, particularly when combined with oxytocin infusion. In a report of 803 women admitted with abortion complications in Rio de Janeiro, 458 reported using misoprostol (Costa 1993). There was one maternal death from uterine rupture at 16 weeks' gestation following self‐medication with misoprostol.

Third trimester cervical ripening and labour induction with misoprostol have been reported using the oral, vaginal, rectal and buccal/sublingual routes. Clinical experience with misoprostol for labour induction has been reviewed by Wing (Wing 1999b).

Mariani Neto et al (Mariani Neto 1987) first reported using oral misoprostol 400 micrograms (mcg) four hourly for induction of labour following intrauterine death.

In a subsequent paper (Mariani Neto 1988), they described 'uterine tachysystole' with misoprostol use at term, which appeared unrelated to dosage. Since that time, several small studies have confirmed an increased incidence of uterine tachysystole (greater than five contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes), uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction of two minutes or more) and/or uterine hyperstimulation syndrome (uterine tachysystole or hypersystole with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes such as persistent decelerations, tachycardia or reduced short term variability). The conclusion from a meta‐analysis was that published data confirmed the safety of intravaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening and labour induction. The data showed an increased incidence of uterine tachysystole (odds ratio 2.70, 95% confidence intervals 1.80 to 4.04), but there was no statistically significant increase in adverse fetal outcome (Sanchez‐Ramos 1997). Wing et al (088 Wing 1995a; 044 Wing 1995b; 025 Wing 1996; 038 Wing 1997) have suggested that uterine hyperstimulation and meconium passage with vaginal misoprostol may be less frequent using a 25 microgram dose, six hourly.

Merrell and co‐workers (Merrell 1995) reported a series of 62 inductions of labour with vaginal misoprostol. There were two stillbirths, one apparently due to a tight nuchal cord, and one unexplained. They commented on rapid onset of contractions and described one woman with induction to delivery interval of only two hours. In a subsequent abstract (Merrell 1996), they described labour inductions with vaginal misoprostol in 345 women with live fetuses and 86 with intrauterine deaths. There was one unexplained maternal death; two uterine ruptures, one of which followed a previous caesarean section; eight caesarean sections for fetal distress and one for uterine hyperstimulation; and 10 perinatal deaths.

There have been several reports of uterine rupture following misoprostol labour induction with and without previous caesarean section (Bennett 1997; Sciscione 1998; Blanchette 1999; Matthews 1999; Khosla 2002). One unpublished case of uterine rupture occurred in a nulliparous woman following misoprostol use (EM Smith, personal communication). At term plus 12 days she received misoprostol 100 mcg vaginally. After six hours her cervix was found to be 7 cm dilated, and she progressed to full dilatation within a further 70 minutes. Fetal distress was suspected. Ventouse application produced no descent, so delivery was effected by caesarean section. The infant showed no signs of life at birth. After resuscitation, life was sustained for a few hours only. A posterior uterine tear arising from the cervix and spiraling up the posterior aspect of the uterus was discovered and repaired. Because such uterine tears are rare in nulliparous women without prolonged labour or syntocinon use, a causal relationship with the use of misoprostol must be considered.

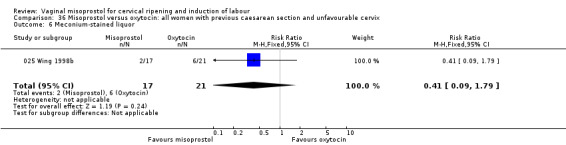

One trial of misoprostol for labour induction in women with prior caesarean section has been terminated prematurely because of disruption of the uterine incision in two of the first 17 misoprostol‐treated women (025 Wing 1998a). The dosage of misoprostol used was conservative (25 µg six hourly to a maximum of four doses). Two and three doses were used respectively in the two cases of ruptured uterus.

In a retrospective review, uterine rupture occurred in 5/89 (5.6%) of women with previous caesarean delivery who had labour induced with misoprostol, compared with 1/423 (0.2%) of those who did not (Plaut 1999). In another retrospective review of labour induction in 575 women with previous caesarean section, the rate of uterine rupture was 5/172 (2.9%) for prostaglandin E2 gel; 1/129 (0.76%) for intracervical Foley catheter; and 3/474 (0.74%) for induction not requiring cervical ripening; compared with 7/1544 (0.45%) for spontaneous trial of labour (Ravasia 2000). In a third retrospective review, no uterine ruptures were detected among 48 women with previous caesarean section whose labour was induced with misoprostol 50 mcg vaginally four hourly (Choy‐Hee 2001).

Personal discussion with colleagues has revealed several cases of rupture of an unscarred uterus following misoprostol usage, possibly related to higher dosages than have been used in the trials reviewed. These cases are usually not reported. We call on readers to send us details of any such cases known to them, including if possible age, parity, any previous uterine surgery, dosage of misoprostol and details of the uterine rupture. This will enable us to compile a register of such problems.

This review will focus on the effectiveness and safety of misoprostol administered vaginally for cervical ripening and labour induction in the third trimester of pregnancy.

The use of oral (Alfirevic 2006) and buccal/sublingual (Muzonzini 2004) misoprostol for cervical priming and labour induction, compared with other methods including misoprostol administered vaginally, are reviewed separately.

Objectives

To determine, from the best available evidence, the effectiveness and safety of misoprostol administered vaginally for third trimester cervical ripening and induction of labour.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials comparing misoprostol administered vaginally for cervical ripening or labour induction, with placebo/no treatment or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction (seeMethods); the trials included some form of random allocation to either group; they reported one or more of the pre‐stated outcomes; reasonable measures were taken to ensure allocation concealment; and violations of allocated management were not sufficient to materially affect outcomes. We have not included quasi‐randomised trials.

Types of participants

Pregnant women due for third trimester induction of labour. We have not excluded multiple pregnancies. Predefined sub‐group analyses (see list below): previous caesarean section or not; nulliparity or multiparity; membranes intact or ruptured, and cervix unfavourable, favourable or undefined. Only those outcomes with data appear in the analysis tables.

Types of interventions

Vaginal administration of misoprostol compared with placebo/no treatment or any other method above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction.

Primary comparisons

Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment Misoprostol versus oxytocin Misoprostol versus vaginal prostaglandins Misoprostol versus intracervical prostaglandins Low dosage misoprostol regimens versus higher dosage regimens Misoprostol gel versus tablets

In all the studies of misoprostol versus prostaglandins, the prostaglandin used was dinoprostone intravaginally as a gel, tablet or slow‐release pessary, or intracervically as a gel. In most of the studies, oxytocin was used with similar protocols for both the misoprostol and the prostaglandin group, except that in one study (175 Kadanali 1996) oxytocin was started if indicated after six hours in the dinoprostone group and only after 24 hours in the misoprostol group. The effective comparison in this trial is therefore misoprostol versus dinoprostone plus early oxytocin. The results are in keeping with those of other studies.

Types of outcome measures

Two authors of labour induction reviews (Justus Hofmeyr and Zarko Alfirevic) have prespecified clinically relevant outcomes for trials of methods of cervical ripening/labour induction. We have settled differences by discussion.

We chose five primary outcomes as being most representative of the clinically important measures of effectiveness and complications. We limited sub‐group analyses to the primary outcomes: (1) vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours; (2) uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes; (3) caesarean section; (4) serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (e.g. seizures, birth asphyxia defined by trialists, neonatal encephalopathy, disability in childhood); (5) serious maternal morbidity or death (e.g. uterine rupture, admission to intensive care unit, septicaemia).

Perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality are composite outcomes. This is not an ideal solution because some components are clearly less severe than others. It is possible for one intervention to cause more deaths but less severe morbidity. However, in the context of labour induction at term this is unlikely. All these events will be rare, and a modest change in their incidence will be easier to detect if composite outcomes are presented. We have explored the incidence of individual components as secondary outcomes (see below).

Secondary outcomes relate to measures of effectiveness, complications and satisfaction.

Measures of effectiveness

(6) Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 to 24 hours; (7) oxytocin augmentation.

Complications

(8) Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes; (9) uterine rupture; (10) epidural analgesia; (11) instrumental vaginal delivery; (12) meconium‐stained liquor; (13) Apgar score less than seven at five minutes; (14) neonatal intensive care unit admission; (15) neonatal encephalopathy; (16) perinatal death; (17) disability in childhood; (18) maternal side effects (all); (19) maternal nausea; (20) maternal vomiting; (21) maternal diarrhoea; (22) other maternal side effects; (23) postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by the trial authors); (24) serious maternal complications (e.g. intensive care unit admission, septicaemia but excluding uterine rupture); (25) maternal death.

Measures of satisfaction

(26) Woman not satisfied; (27) caregiver not satisfied.

'Uterine rupture' will include all clinically significant ruptures of unscarred or scarred uteri. We will exclude trivial scar dehiscence noted incidentally at the time of surgery.

While we sought all the above outcomes, we have included only those with data in the analysis tables.

The terminology of uterine hyperstimulation is problematic (Curtis 1987). In this review we have used the term 'uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes' to include uterine tachysystole (greater than five contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes) and uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction lasting at least two minutes) and 'uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes' to denote uterine hyperstimulation syndrome (tachysystole or hypersystole with FHR changes such as persistent decelerations, tachycardia or decreased short‐term variability). However, due to varied reporting there is the possibility of subjective bias in interpretation of these outcomes. Also, it is not always clear from trials if these outcomes are reported in a mutually exclusive manner.

We included outcomes in the analysis if reasonable measures were taken to minimise observer bias; missing data were insufficient to materially influence conclusions; and data were available for analysis according to original allocation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (November 2008). We updated this search on 15 February 2012 and added the results to Studies awaiting classification.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We hand searched the reference lists of trial reports and reviews.

We screened and assessed all Chinese papers according to the review protocol by a first‐language Chinese speaker (Linan Cheng) and excluded all due to serious methodological limitations.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

To avoid duplication of data, the authors of induction of labour reviews agreed a specific order for labour induction methods, from one to 27. Each primary review included comparisons between one of the methods (from two to 27) with only those methods above it on the list. Thus, this review of intravenous oxytocin (4) included only comparisons with intracervical prostaglandins (3), vaginal prostaglandins (2) or placebo/no treatment (1). The current list is as follows:

(1) placebo/no treatment; (2) vaginal prostaglandins (Kelly 2003); (3) intracervical prostaglandins (Boulvain 2008); (4) intravenous oxytocin (Kelly 2001a); (5) amniotomy (Bricker 2000); (6) intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy (Howarth 2001); (7) vaginal misoprostol; (8) oral misoprostol (Alfirevic 2006); (9) mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter (Boulvain 2001); (10) membrane sweeping (Boulvain 2005); (11) extra‐amniotic prostaglandins (Hutton 2001); (12) intravenous prostaglandins (Luckas 2000); (13) oral prostaglandins (French 2001); (14) mifepristone (Hapangama 2009); (15) oestrogens with or without amniotomy (Thomas 2001); (16) corticosteroids (Kavanagh 2006a); (17) relaxin (Kelly 2001b); (18) hyaluronidase (Kavanagh 2006b); (19) castor oil, bath, and/or enema (Kelly 2001c); (20) acupuncture (Smith 2004); (21) breast stimulation (Kavanagh 2005); (22) sexual intercourse (Kavanagh 2001); (23) homoeopathic methods (Smith 2003); (24) nitric oxide donors (Kelly 2008); (25) buccal or sublingual misoprostol (Muzonzini 2004); (26) hypnosis; (27) other methods for induction of labour.

The reviews were analysed by the following clinical categories of participants:

previous caesarean section or not;

nulliparity or multiparity;

membranes intact or ruptured;

cervix favourable, unfavourable or undefined.

For most reviews, the initial data extraction process was conducted centrally. This was co‐ordinated from the Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit (CESU) at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, UK, in co‐operation with the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group of The Cochrane Collaboration. This process allowed the data extraction process to be standardised across all the reviews. From 2001, the data extraction was no longer conducted centrally.

The trials were initially reviewed on eligibility criteria, using a standardised form and the basic selection criteria specified above. Following this, a standardised data extraction form was developed and then piloted for consistency and completeness. This pilot process involved the researchers at the CESU and previous review authors in the area of induction of labour. For a description of the methods used to carry out the initial reviews, seeAppendix 1.

Due to the large number of trials, double data extraction was not feasible and agreement between the three data extractors was therefore assessed on a random sample of trials to update in 2003. For the same reason, in the 2009 update, the data extraction was checked on around 50% of the trials in a random sample selection.

In 2008, the methods and software for carrying out reviews were updated, as a result of which new reviews and updates, where appropriate, use these new methods (Higgins 2008a; RevMan 2008), which are described in the Methods section of all the individual new and updated reviews.

For this update, we used the following methods when assessing the new trials identified by the updated search.

Selection of studies

One review author (Cynthia Pileggi (CP)) assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We discussed studies for which there was any uncertainty with a second author (Justus Hofmeyr (GJH)).

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, one review author (CP) extracted the data using the agreed form. GJH independently repeated selection of studies and data extraction on a random sample of studies. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we would have consulted the third author. We entered the data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) and checked them for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

One review author (CP) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008a).

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determined whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We judged studies at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias, high risk of bias or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low risk of bias, high risk of bias or unclear risk of bias for personnel;

low risk of bias, high risk of bias or unclear risk of bias for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we would re‐include missing data in the analyses. We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (less than 5% loss to follow up);

high risk of bias;

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other sources of bias

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

yes;

no;

unclear.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2008a). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it is likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we present results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

This systematic review did not include continuous data.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We would include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials. We would adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook (Higgins 2008b) using an estimate of the intra cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), or from another source. If ICCs from other sources are used,we planned to report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify cluster‐randomised trials in addition to the individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We would consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We also planned to acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a separate meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we have noted levels of attrition. We explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we have carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial is the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (I² greater than 50%), we explored it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspected reporting bias (see ‘Selective reporting bias’ above), we attempted to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we explored the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by a sensitivity analysis.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We used fixed‐effect Mantel‐Haenszel meta‐analysis for combining dichotomous data where trials were examining the same intervention, and we judged the trials’ populations and methods sufficiently similar. Where we suspected clinical or methodological heterogeneity between studies sufficient to suggest that treatment effects may differ between trials, we used a random‐effects meta‐analysis.

If we identified substantial heterogeneity, we noted this and performed the analysis using a random‐effects method.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We carried out the following subgroup analyses:

previous caesarean section or not;

nulliparity or multiparity;

membranes intact or ruptured;

cervix favourable, unfavourable or undefined.

We used primary outcomes only in subgroup analysis.

For fixed‐effect meta‐analyses we conducted planned subgroup analyses classifying whole trials by interaction tests as described by Deeks 2001. For random‐effects meta‐analyses we assessed differences between subgroups by inspection of the subgroups’ confidence intervals; non‐overlapping confidence intervals indicate a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We plan to carry out sensitivity analysis by excluding trials with greater risk of bias, particularly with respect to allocation concealment, in a future update of this review.

Results

Description of studies

Included studies

We have included 121 studies in this review. See table of Characteristics of included studies for details. (Twenty‐seven reports from an updated search in February 2012 have been added toStudies awaiting classification.) Because a wide range of misoprostol dosages has been used, we have coded the included studies with a prefix to reflect roughly the dosage of vaginal misoprostol received in the first six hours, calculated as follows: initial dose + (s x (6 ‐ i)/4), where 's' is a subsequent dose within six hours, and 'i' is the interval in hours. This is based on the approximation that vaginal misoprostol is absorbed uniformly over a four‐hour period. Where a subsequent oral dose was used, the oral dose value was halved. Use of a gel preparation is indicated by the letter 'G'. This coding allows approximate ranking of the trials by misoprostol dosage, and enables readers to assess the effect of dosage on results. We detected no discrepancies in the sample of data extraction performed in duplicate.

Excluded studies

For details of excluded studies, see table of Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

With the exception of 13 double‐blind trials (100G Fletcher 1993; 050 El‐Azeem 1997; 043 Farah 1997; 050 Surbek 1997; 050 Gotschall 1998; 025G Srisomboon 1998; 043 Diro 1999; 100 Montealegre 1999; 025 Stitely 2000; 048 Khoury 2001; 058 Ferguson 2002; 038 Meydanli 2003; 050 Ramsey 2003 ‐ blinded low versus high dose misoprostol comparison only), allocation was by means of sealed envelopes or unspecified, and treatment was not blinded. There is therefore a real possibility of bias affecting both the clinical management of the women (e.g. decisions to undertake caesarean section) and the assessment of outcomes. Such biases might operate in either direction (for example, a clinician enthusiastic about the potential of misoprostol might be less likely to perform caesarean section in the misoprostol group, while one anxious about the experimental nature of misoprostol might be more likely to perform caesarean section in this group).

We performed limited sensitivity analysis excluding non‐blinded studies for primary outcomes with significant heterogeneity and 10 or more trials included. For the comparison misoprostol versus vaginal prostaglandins, all women: the outcome vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours was unchanged; the outcome uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes was no longer statistically significant (small numbers). For the comparison misoprostol versus oxytocin: the outcomes vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours and caesarean section were no longer statistically significant (small numbers remaining in the analysis).

The possibility of bias must be kept in mind in the interpretation of the results.

In the study of 050 Le Roux 2002, 93 of 573 enrolled women were excluded for 'protocol violations'. There did not appear to be a selective loss from any group, and the baseline data were similar between groups.

In 050 Pandis 2001, 235/670 were excluded after randomisation, mainly for spontaneous delivery before induction or induction by amniotomy for cervical score seven or more.

In 075 Ghidini 2001, seven of 65 enrolled women were excluded due to emergence of exclusion criteria. The groups were somewhat unbalanced (32 received 50 mcg and 26 received 100 mcg)

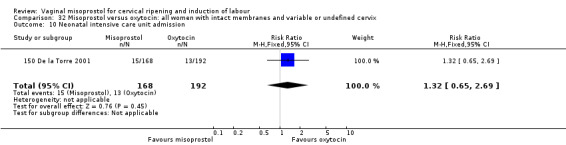

In 150 De la Torre 2001, 50 of 410 enrolled were withdrawn for protocol deviation (16), patient withdrawal (7), or missing data (27). The final groups differed in numbers (misoprostol 168, oxytocin 192). This raises the possibility of selective withdrawal from the misoprostol group.

In 088 Garry 2003, 14 women of 200 enrolled were withdrawn for physician request(10), used wrong medication (2), patient request (1) and unknown breech presentation (1). It suggests deviation from the intention to treat analysis.

The 2009 update used the new methodology of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008a) regarding the evaluation of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors, report of incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting bias and other sources. We have presented the quality evaluation of each included study in the corresponding risk of bias table.

This update includes 54 comparisons with more than 10 study results in the pooled analyses, 19 of them in primary outcomes. Five out of these 19 comparisons present asymmetrical funnel plots suggesting potential publication bias.

Effects of interventions

We have included 121 studies in this review. We sought all the outcomes listed under 'Types of outcome measures', and sub‐groups defined in 'Types of participants'. Only those with data appear in the analysis tables.

Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo

Primary outcomes

The 10 studies (1141 women) included in this part of the review (100G Fletcher 1993; 100G Srisomboon 1996; 025 Stitely 2000; 050 Thomas 2000; 025 Incerpi 2001; 050 Ortiz 2002; 025 McKenna 2004; 050 Gelisen 2005; 025 Krupa 2005; 025 Oboro 2005) showed a trend towards failure to deliver within 24 hours (five trials, 735 women, average relative risk (RR) 0.56, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.03).

Secondary outcomes

We found a clear effect of misoprostol on cervical ripening (two trials, average RR of unchanged cervix at 12 to 24 hours 0.09, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.03 to 0.24).

Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes was increased (six trials, 794 women RR 3.52, 95% CI 1.78 to 6.99). Six trials (100G Fletcher 1993;025 Stitely 2000; 050 Thomas 2000; 050 Ortiz 2002; 050 Gelisen 2005; 025 Krupa 2005) with 814 women showed an unexpected reduction of meconium‐stained liquor with the use of misoprostol for labour induction.The numbers studied were too small to assess the impact on obstetric management and maternal and neonatal complications.

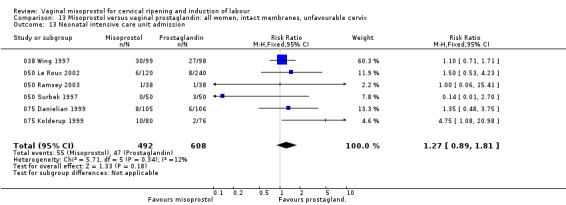

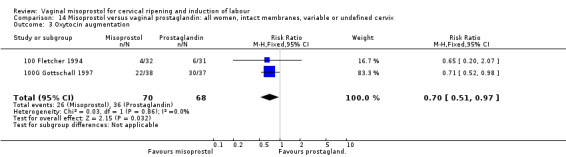

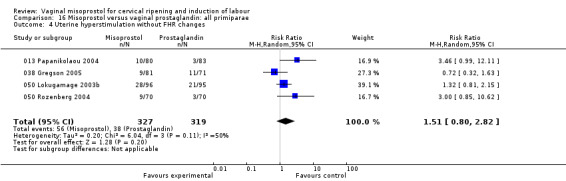

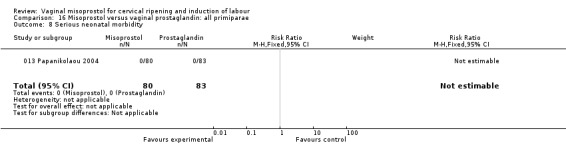

Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal prostaglandins

There were 38 included trials with 7022 participants.

Primary outcomes

Failure to achieve vaginal delivery within 24 hours (22 trials, average RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.89) was reduced overall, but not in the two trials using less than 50 mcg misoprostol in the first six hours (038 Wing 1997; 048 Khoury 2001).

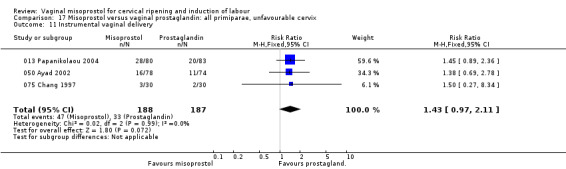

Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes was variable between trials, but overall tended to be more common with misoprostol (31 trials, average RR 1.43, 95% CI 0.97 to 2.09).

Caesarean sections were variable between trials, with a trend to be reduced with vaginal misoprostol (34 trials RR 0.95, 95%CI 0.87 to 1.03).

Secondary outcomes

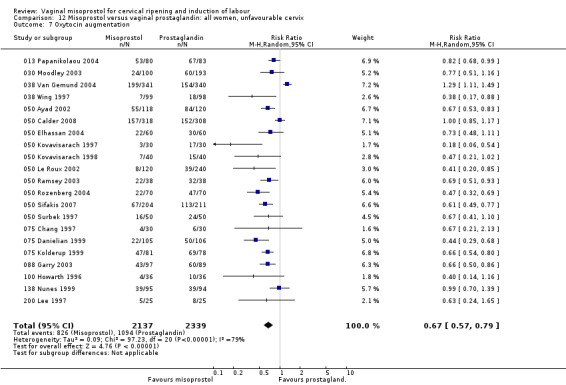

Oxytocin augmentation was reduced with misoprostol (36 trials, average RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.76).

Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes was more common with misoprostol (26 trials, average RR1.99, 95% CI 1.41 to 2.79).

Epidural analgesia was used less frequently with misoprostol (eight trials, RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.99).

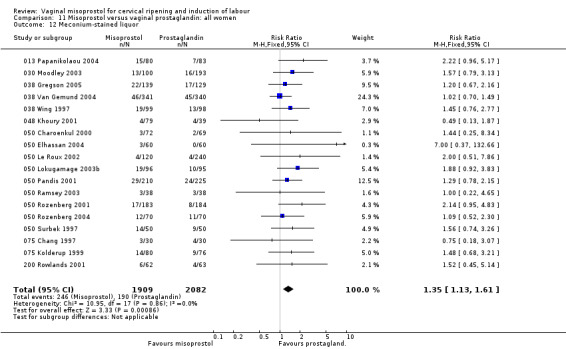

Meconium‐stained liquor was more common with misoprostol (18 trials, RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.61). There were no statistically significant differences in perinatal or maternal outcomes.

Results were similar for the sub‐groups of women with unfavourable cervices and those with intact membranes and unfavourable cervices.

There were similar trends for women with intact membranes and variable or undefined cervices, but the numbers were too small for clear outcomes.

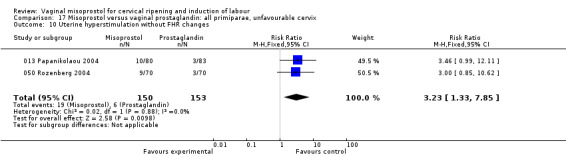

For subgroups of primiparous or multiparous women, the numbers were small and no differences in any outcomes were shown, except that for all primiparous women, misoprostol shows reduced caesarean section (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.99), and a trend to reduced vaginal delivery not achieved in 24h (average RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.05).

The results of 048 Khoury 2001 differed somewhat from other studies. This may be because a gel preparation of misoprostol was used, and it is possible that some activity is lost in the preparation or administration (see results of misoprostol gel versus tablets below).

Vaginal misoprostol versus intracervical prostaglandins

There were 27 included trials with 3311 participants.

Primary outcomes

Failure to achieve vaginal delivery within 24 hours was consistently reduced with misoprostol (13 trials, RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.71).

Uterine hyperstimulation with associated FHR changes was variable between trials, but all were consistent with the pooled result showing an increase with misoprostol (20 trials, RR 2.32, 95% CI 1.64 to 3.28). The latter result was similar for the sub‐group of trials studying women with intact membranes and unfavourable cervices.

Caesarean sections were variable between trials, with no significant differences overall.

Secondary outcomes

Only one trial reported the outcome 'failure to achieve cervical ripening within 12 hours' (075 Buser 1997); this was reduced with misoprostol (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.88).

Oxytocin augmentation was used less often with misoprostol (20 trials, average RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.64).

Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes was more common with misoprostol (17 trials, RR 1.95, 95% CI 1.57 to 2.42).

The rates of vaginal instrumental delivery were variable between trials. Epidural analgesia was used less frequently with misoprostol (two trials, RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.86). Meconium‐stained liquor was increased with misoprostol (14 trials, RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.59). There were no statistically significant differences in perinatal or maternal outcomes.

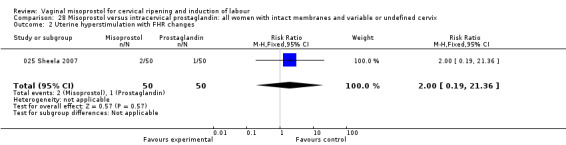

Most of the trials studied women with unfavourable cervices, for whom the results were similar to the overall results. Results were also similar for women with intact membranes and unfavourable cervices. The two trials with intact membranes and variable or undefined cervix also showed a similar pattern of results.

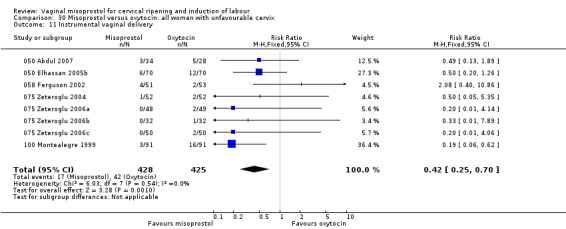

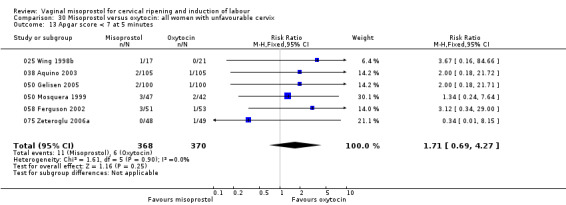

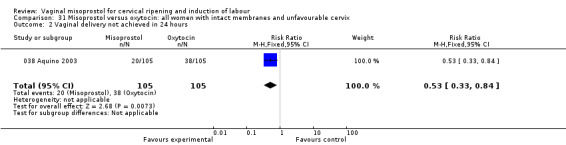

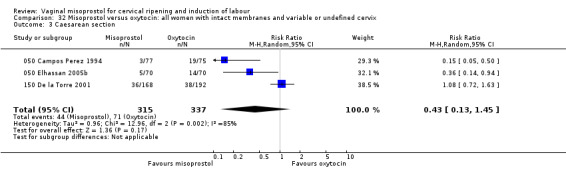

Vaginal misoprostol versus oxytocin

There were 25 trials with 3074 participants.

Primary outcomes

Misoprostol, in the doses used in these trials, was more effective than oxytocin for labour induction (10 trials, average RR of failure to achieve vaginal delivery within 24 hours 0.65, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.90). Two trials using less than 50 mcg misoprostol showed no reduction (025 Wing 1998b; 025 Haghighi 2006).

Twenty‐five studies showed a reduction in caesarean section risk with the use of misoprostol (average RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.96).

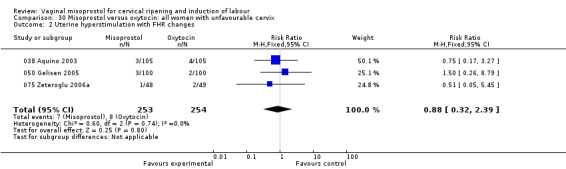

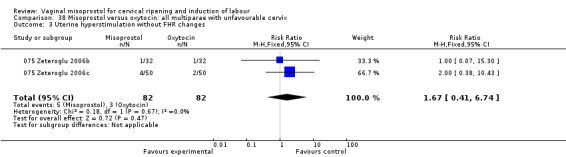

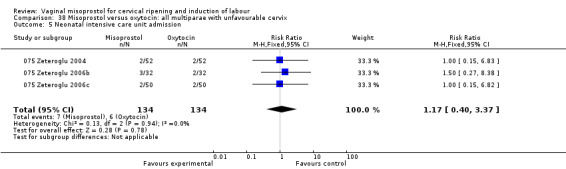

Secondary outcomes

Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes was more common with misoprostol (15 trials, RR 2.24 95% CI 1.82 to 2.77 respectively). There was a trend to reduced epidural analgesia with misoprostol (three trials, RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.00). Vaginal instrumental delivery was reduced in the misoprostol group (13 trials, RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.99).

Apgar score less than 7 at five minutes, with 13 studies and 1906 participants in the general group, was substantially reduced with misoprostol use (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.92). Four studies with 334 participants showed increased risk of maternal side effects (RR 5.04, 95% CI 1.51 to 16.86). There were no differences in other perinatal or maternal outcomes.

One trial in women with previous caesarean section was stopped when uterine rupture occurred in two of the first 17 women who received misoprostol (025 Wing 1998b) and in another study one uterine rupture occurred in 34 women in the misoprostol group (all women with unfavourable cervix, 050 Abdul 2007).

Misoprostol lower dosage regimen versus higher dose

There were 21 trials with 2913 participants. The dosages compared are as follows.

| Number of studies | Misoprostol low dosage | Misoprostol high dosage | Interval of use |

| 2 | 12.5 mcg | 25 mcg | 4 to 6 hours |

| 11 | 25 mcg | 50 mcg | 3 to 6 hours |

| 1 | 35 mcg | 50 mcg | 4.5 hours |

| 6 | 50 mcg | 100 mcg | 4 to 6 hours |

| Note: 006 Ewert 2006 was not included because of the mode of misoprostol administration. | |||

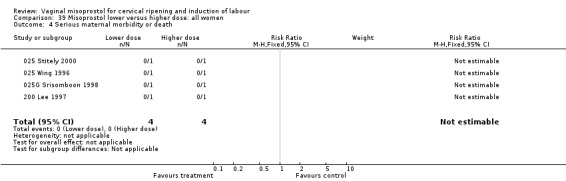

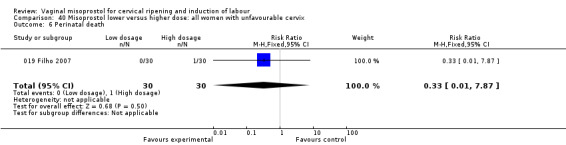

Primary outcomes

There was no significant difference in the risk of failures to achieve delivery within 24 hours. There was less uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes in the lower dose groups (16 trials, RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.69).

Serious maternal complications were reported in one study (025 Wing 1996): one maternal death occurred in a primiparous woman, nine hours after a single misoprostol dose and shortly after amnioinfusion and epidural analgesia, from amniotic fluid embolisation. Two caesarean hysterectomies were performed for atonic uterine haemorrhage, 13 and 30 hours after single doses of misoprostol, in one primiparous woman with uncomplicated labour, and in one nulliparous woman who developed chorioamnionitis following prolonged labour induction attempts by oxytocin augmentation. It is not clear whether these three women were allocated to the low (25 mcg) or the higher (50 mcg) dosage regimen misoprostol group.

Secondary outcomes

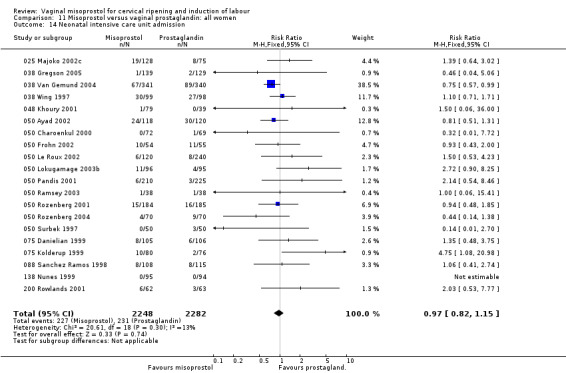

There was significantly more use of oxytocin (18 trials, average RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.49). This effect was due to the trials with a lower range of doses, and was not seen in the trials in which the lower dosage was 50 mcg. There were no differences in mode of delivery, meconium‐stained liquor or maternal side effects. There was less uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes (14 trials, RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.69). There was a trend to fewer babies being admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (9 trials, RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.05), particularly in the higher dose ranges.

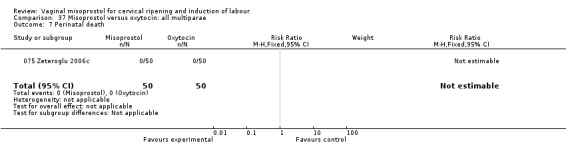

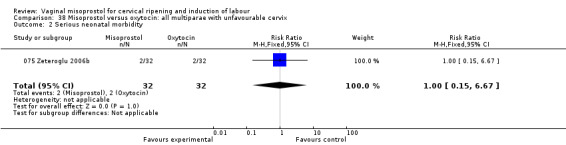

Five perinatal deaths were reported (019 Filho 2007; 050 Majoko 2002a). There was one uterine rupture (038 Has 2002) with the use of low dose of misoprostol and two with the use of higher dose of misoprostol (050 Majoko 2002a; 075 Reyna‐Villasmil 2005). However, most studies have not specifically reported these outcomes. We have included only those specified in the reports in the data tables.

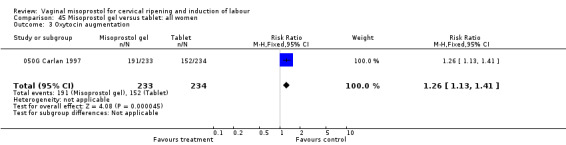

Misoprostol gel versus tablets

Primary outcomes

In one trial with 467 participants reviewed (050G Carlan 1997), uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes was reduced with the gel preparation (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.83).

Secondary outcomes

The use of oxytocin (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.41) and epidural analgesia (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.38) were increased. It is possible that in the process of gel preparation some potency is lost or that absorption is reduced.

One study showed no benefit from moistening misoprostol prior to insertion with 11 ml 3% acetic acid, versus dry tablets (Sanchez Ramos 2002).

A cost analysis in a high‐income country showed that the reduced cost in the misoprostol group (Sterling mean 2134, SD 574 versus 2202, SD 595 per case) was insignificant in relation to the overall cost of labour induction (050 Rozenberg 2001).

Discussion

Overall, this systematic review found that vaginal misoprostol is the more effective option for induction of labour and cervical ripening compared with oxytocin, dinoprostone and placebo. It also found that higher doses of vaginal misoprostol have no comparative advantages to the lower doses. There is, in general, considerable consistency between trials, except with respect to caesarean section rates and to the low misoprostol dosage regimens. The trials show that vaginal misoprostol in dosages ranging from 25 mcg two to three hourly, to 50 mcg four hourly (most studies), to 100 mcg six to 12 hourly, appear to be more effective than oxytocin or dinoprostone in the usual recommended doses for induction of labour, but with increased rates of uterine hyperstimulation both without and with associated FHR changes. The rates of caesarean section were inconsistent, tending to be reduced with misoprostol. The indication for caesarean section was not a prespecified outcome in this review. However, there was a consistent pattern of more operations for fetal distress and fewer for poor labour progress in the misoprostol groups (see 'Characteristics of included studies' table under 'Outcomes').

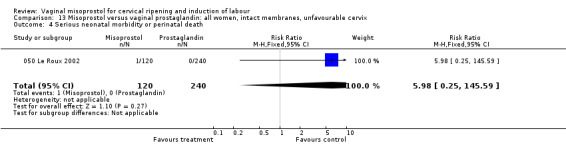

No differences in perinatal or maternal outcome were shown. However, the trials were not sufficiently large to assess the likelihood of uncommon, serious adverse perinatal and maternal complications. Of particular concern are several reports of uterine rupture following misoprostol use in women with and without previous caesarean section. One maternal death from amniotic fluid embolism following misoprostol induction was reported.

The possibility of inadvertent bias because of the unblinded nature of these studies should be kept in mind.

Lower dosage regimens of misoprostol were not less effective than higher doses in terms of failure to achieve vaginal birth within 24 hours. Adverse effects were reduced, with lower rates of uterine hyperstimulation and a trend to fewer admissions to neonatal intensive care unit.

The finding of a significantly more meconium‐stained liquor with misoprostol versus vaginal or intracervical prostaglandins is of interest. Wing et al (088 Wing 1995a) suggested the possibility of meconium passage in response to uterine hyperstimulation or a direct effect of absorbed misoprostol metabolites on the fetal gastrointestinal tract. We have previously observed an increased rate of meconium‐stained liquor in women who have ingested castor oil, though causality was not proven, and suggested a possible direct effect of the castor oil metabolites on fetal bowel (Mitri 1987). It is unlikely that the small amount of hydrogenated castor oil found in misoprostol tablets (075 Chuck 1995) would have any pharmacological effect, but the possibility that misoprostol metabolites may directly stimulate fetal bowel is of interest. We have shown an in vitro effect of misoprostol on isolated rat ileum (as well as myometrium) (Matonhodze 2002).

In countries in which misoprostol is being used for non‐registered obstetric indications, there is a need for health authorities and professional organisations to clarify the medicolegal implications. Particularly in countries in which conventional prostaglandins are unaffordable, health authorities need to decide whether misoprostol should be used in specific circumstances and, if so, take steps to legalise and regulate such use.

The trials reviewed lacked information on women's views with respect to this method of labour induction.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The comparison between oral and vaginal misoprostol is dealt with in a separate Cochrane review (Alfirevic 2006). That review suggests that the optimal route for administration of misoprostol for labour induction is oral, not vaginal. The reasons for this are as follows.

Safety. The oral route is associated with a reduction in Apgar score of less than seven at five minutes (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.97); and uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes (RR 0.58, 95%CI 0.35 to 0.96, significant heterogeneity).

Convenience and comfort for the woman.

Because of a short half‐life, the oral dose can be titrated against the uterine response, commencing with a low dose such as 25 mcg two‐hourly, and increasing if necessary in nulliparous women to a maximum dose of 50 mcg two‐hourly.

Accuracy of dosage. In many countries, misoprostol is available only as 200 mcg or 100 mcg tablets. Breaking these tablets into small fragments for vaginal administration carries the risk of inappropriate dosage. Accurate oral dosage can be achieved by dissolving misoprostol in tap water, shaking well and administering as a solution. Left over solution should be discarded 24 hours after preparation.

The relative disadvantages of oral versus vaginal misoprostol are greater need for oxytocin augmentation (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.34, significant heterogeneity).

The results of this review are therefore of limited practical importance: in dosages of 25 mcg three hourly or more, vaginal misoprostol is more effective than conventional methods of cervical ripening and labour induction. However, uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes are increased. Although no differences in perinatal outcome were shown, the studies were not sufficiently large to exclude the possibility of uncommon serious adverse effects. The increase in meconium‐stained liquor is also of concern. Anecdotal reports of uterine rupture following labour induction with misoprostol are cause for concern (Gherman 1999; Daisley 2000; Hill 2000; Majoko 2002b).

The limited information on lower dosage regimens (25 mcg four hourly or less) suggests that they may be as effective as other prostaglandins, without increased uterine hyperstimulation.

Though misoprostol shows promise as a highly effective, inexpensive and convenient agent for labour induction, the lack of registration for this purpose, and thus of well‐established regimens, is problematic.

In most countries misoprostol is not registered for use for labour induction. In countries in which its use is considered advantageous, it is important that health authorities provide guidelines for practitioners to ensure the greatest possible level of safety in its use.

Implications for research.

While this review assessed the efficacy and safety of vaginal misoprostol (including its different regimens) based on data from its comparison to oral misoprostol, the vaginal route should not be researched further.

Because of the potential economic and clinical advantages of misoprostol, there is the need for further trials to establish its safety, particularly the relative safety of various dosages of oral administration. On the basis of this review, such trials should have the following features.

(1) Randomised, double blind.

(2) Oral or sublingual route of administration.

(3) Sample size sufficient to detect moderate differences in important uncommon complications such as serious perinatal morbidity/mortality.

(4) Meconium‐stained liquor included as an outcome measure.

(5) Women's views included as an outcome.

Randomised trials sufficiently large to assess rare events such as uterine rupture are not feasible. Alternative research methods are necessary such as case‐control studies and prospective audits of complications in services in which misoprostol is used routinely for labour induction.

We would be grateful to receive reports of rare serious complications such as uterine rupture in order to compile a register of such incidents.

[Note: The 27 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Feedback

Mwanza, July 2002

Summary

From my experience of induction of labour I agree that the risk of failure is far less with misoprostol than with prostaglandin E2. If women are carefully selected and started with the lower dose (we used 50 micrograms in one hospital in Zambia) the complications of hyperstimulation and occasional excessive vomiting would be significantly reduced.

The low cost of misoprostol and its effectiveness support its use in low‐middle income countries.

[Summary of comment from Moses Mabimba Mwanza, July 2002]

Reply

We agree with Dr Mwanza that if misoprostol is used for labour induction, the dosage should be kept to a minimum. Our findings suggest that the vaginal dosage should not exceed 25 mcg 4‐hourly.

[Reply from Justus Hofmeyr, August 2002]

Contributors

Moses Mabimba Mwanza

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 February 2012 | Amended | Search updated. Twenty‐seven reports added to Studies awaiting classification (Ayaz 2010; Balci 2010; Balci 2011; Begum 2009; Brennan 2011; Chaudhuri 2011; Chen 2000a; Ezechi 2008; Girija 2009; Girija 2011; Gupta 2010; Hosli 2008; Joo 2000; Kim 2000; Mahendru 2011; Norzilawati 2010; Pevzner 2011; Pezvner 2011; Powers 2011; Rolland 2011; Saeed 2011; Shakya 2010; Shanmugham 2011; Stephenson 2011; Tan 2010; Wing 2011; Yang 2000a). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1998 Review first published: Issue 1, 1998

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 September 2009 | New search has been performed | We included 51 additional studies from an updated search in November 2008. We updated the search in April 2010 and added the results to Studies awaiting classification for consideration in the next update. |

| 10 September 2009 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New author updated review with an additional 51 studies, which have provided more precise and robust conclusions. |

| 1 October 2002 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (Tony Kelly, Josephine Kavanagh, Jane Thomas), for primary data extraction. Zarko Alfirevic, Jim Neilson and Sonja Henderson, Tony Kelly and Josephine Kavanagh for contributions to development of the generic protocol for reviews of labour induction. Edwin S‐Y Chan and Ken Gu of the NMRC Clinical Trials and Epidemiology Unit, Ministry of Health, Singapore for translating two Chinese papers. Linan Cheng for retrieving, translating and assessing 28 Chinese papers.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methods used to assess trials included in previous versions of this review

A strategy has been developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. Many methods have been studied, in many different categories of women undergoing labour induction. Most trials are intervention‐driven, comparing two or more methods in various categories of women. Clinicians and parents need the data arranged by category of woman, to be able to choose which method is best for a particular clinical scenario. To extract these data from several hundred trial reports in a single step would be very difficult. We have therefore developed a two‐stage method of data extraction. The initial data extraction is done in a series of primary reviews arranged by methods of induction of labour, following a standardised methodology. The data will then be extracted from the primary reviews into a series of secondary reviews, arranged by category of woman.

To avoid duplication of data in the primary reviews, the labour induction methods have been listed in a specific order, from one to 25. Each primary review includes comparisons between one of the methods (from two to 25) with only those methods above it on the list. Thus, the review of intravenous oxytocin (4) will include only comparisons with intracervical prostaglandins (3), vaginal prostaglandins (2) or placebo (1). Methods identified in the future will be added to the end of the list. The current list is as follows:

(1) placebo/no treatment; (2) vaginal prostaglandins; (3) intracervical prostaglandins; (4) intravenous oxytocin; (5) amniotomy; (6) intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy; (7) vaginal misoprostol; (8) oral misoprostol; (9) mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter; (10) membrane sweeping; (11) extra‐amniotic prostaglandins; (12) intravenous prostaglandins; (13) oral prostaglandins; (14) mifepristone; (15) estrogens; (16) corticosteroids; (17) relaxin; (18) hyaluronidase; (19) castor oil, bath, and/or enema; (20) acupuncture; (21) breast stimulation; (22) sexual intercourse; (23) homoeopathic methods; (24) nitric oxide; (25) buccal or sublingual misoprostol.

The primary reviews are analysed by the following subgroups: (1) previous caesarean section or not; (2) nulliparity or multiparity; (3) membranes intact or ruptured; (4) cervix favourable, unfavourable or undefined.

The secondary reviews will include all methods of labour induction for each of the categories of women for which subgroup analysis has been done in the primary reviews, and will include only five primary outcome measures. There will thus be six secondary reviews of methods of labour induction in the following groups of women:

(1) nulliparous, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (2) nulliparous, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (3) multiparous, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (4) multiparous, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (5) previous caesarean section, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined); (6) previous caesarean section, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined).

Each time a primary review is updated with new data, those secondary reviews which include data which have changed, will also be updated.

The trials included in the primary reviews were extracted from an initial set of trials covering all interventions used in induction of labour (see above for details of search strategy). The data extraction process was conducted centrally. This was co‐ordinated from the Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit (CESU) at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, UK, in co‐operation with The Pregnancy and Childbirth Group of The Cochrane Collaboration in 2000. This process has allowed the data extraction process to be standardised across all the reviews.

The trials are initially reviewed on eligibility criteria, using a standardised form and the basic selection criteria specified above. Following this, data are extracted to a standardised data extraction form which was piloted for consistency and completeness. The pilot process involved the researchers at the CESU and previous reviewers in the area of induction of labour.

Information is extracted regarding the methodological quality of trials on a number of levels. This process is completed without consideration of trial results. Assessment of selection bias examines the process involved in the generation of the random sequence and the method of allocation concealment separately. These are then judged as adequate or inadequate using the criteria described in Table 01 for the purpose of the reviews.

Performance bias is examined with regards to whom was blinded in the trials i.e. patient, caregiver, outcome assessor or analyst. In many trials the caregiver, assessor and analyst were the same party. Details of the feasibility and appropriateness of blinding at all levels is sought.

Individual outcome data are included in the analysis if they meet the pre stated criteria in 'Types of outcome measures'. Included trial data are processed as described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Clarke 2000). Data extracted from the trials are analysed on an intention to treat basis (when this was not done in the original report, re‐analysis is performed if possible). Where data are missing, clarification is sought from the original authors. If the attrition was such that it might significantly affect the results, these data are excluded from the analysis. This decision rests with the reviewers of primary reviews and is clearly documented. Once missing data become available, they will be included in the analyses.

Data are extracted from all eligible trials to examine how issues of quality influence effect size in a sensitivity analysis. In trials where reporting is poor, methodological issues are reported as unclear or clarification sought.

Due to the large number of trials, double data extraction was not feasible and agreement between the three data extractors was therefore assessed on a random sample of trials.

Once the data had been extracted, they were distributed to individual reviewers for entry onto the Review Manager computer software (RevMan 1999), checked for accuracy, and analysed as above using the RevMan software. For dichotomous data, relative risks and 95% confidence intervals are calculated, and in the absence of heterogeneity, results are pooled using a fixed effects model.

The predefined criteria for sensitivity analysis include all aspects of quality assessment as mentioned above, including aspects of selection, performance and attrition bias.

Primary analysis is limited to the prespecified outcomes and sub‐group analyses. In the event of differences in unspecified outcomes or sub‐groups being found, these are analysed post hoc, but clearly identified as such to avoid drawing unjustified conclusions.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours | 5 | 769 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.31, 1.03] |

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 5 | 777 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.38 [0.95, 5.99] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 10 | 1141 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.63, 1.05] |

| 4 Neonatal encephalopathy | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours | 2 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [0.01, 0.64] |

| 6 Oxytocin augmentation | 5 | 429 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.38, 1.02] |

| 7 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 6 | 794 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.52 [1.78, 6.99] |

| 8 Uterine rupture | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 3 | 184 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.65, 1.77] |

| 10 Meconium‐stained liquor | 6 | 814 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.35, 0.87] |

| 11 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 4 | 717 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.34, 11.80] |

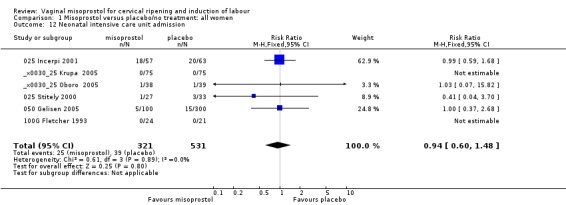

| 12 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 6 | 852 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.60, 1.48] |

| 13 Perinatal death | 2 | 122 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.01, 8.14] |

| 14 Maternal side effects | 1 | 62 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.82 [0.12, 66.62] |

| 15 Postpartum haemorrhage | 3 | 184 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.19, 4.62] |

| 16 Serious maternal complication | 3 | 272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.12, 3.87] |

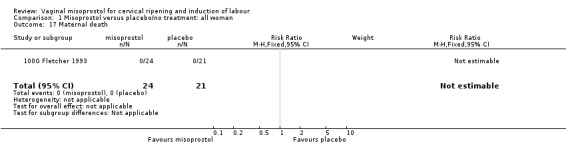

| 17 Maternal death | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 4 Neonatal encephalopathy.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 5 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 6 Oxytocin augmentation.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 7 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 8 Uterine rupture.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 9 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 10 Meconium‐stained liquor.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 11 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 12 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 13 Perinatal death.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 14 Maternal side effects.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 15 Postpartum haemorrhage.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 16 Serious maternal complication.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, Outcome 17 Maternal death.

Comparison 2. Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

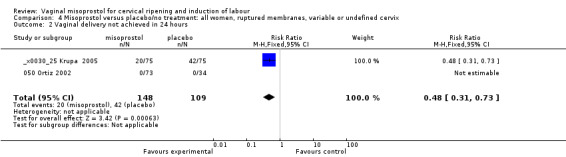

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours | 4 | 619 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.23, 2.15] |

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 4 | 627 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.05 [0.73, 5.71] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 7 | 862 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.69, 1.30] |

| 4 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours | 2 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [0.01, 0.64] |

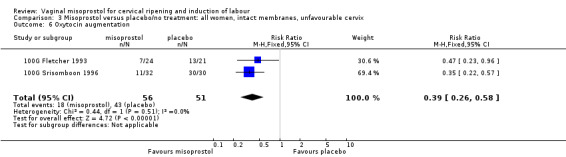

| 5 Oxytocin augmentation | 2 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.26, 0.58] |

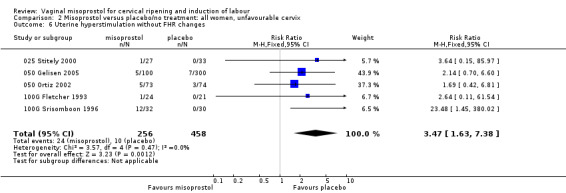

| 6 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 5 | 714 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.47 [1.63, 7.38] |

| 7 Uterine rupture | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

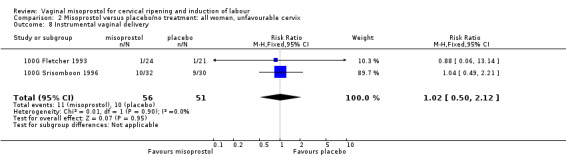

| 8 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.50, 2.12] |

| 9 Meconium‐stained liquor | 4 | 612 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.31, 0.89] |

| 10 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 3 | 567 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.34, 11.80] |

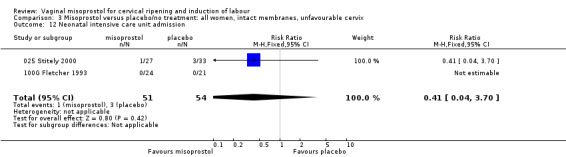

| 11 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 3 | 505 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.35, 2.05] |

| 12 Perinatal death | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13 Maternal side effects | 1 | 62 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.82 [0.12, 66.62] |

| 14 Postpartum haemorrhage | 2 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.13, 6.37] |

| 15 Serious maternal complication | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16 Maternal death | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 4 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 5 Oxytocin augmentation.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 6 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 7 Uterine rupture.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 8 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 9 Meconium‐stained liquor.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 10 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 12 Perinatal death.

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 13 Maternal side effects.

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 14 Postpartum haemorrhage.

2.15. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 15 Serious maternal complication.

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 16 Maternal death.

Comparison 3. Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours | 2 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.22, 0.70] |

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes | 3 | 227 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.31 [0.52, 10.16] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 5 | 355 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.75, 1.79] |

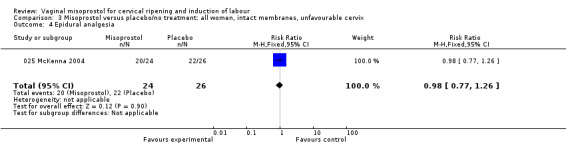

| 4 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.77, 1.26] |

| 5 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours | 2 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [0.01, 0.64] |

| 6 Oxytocin augmentation | 2 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.26, 0.58] |

| 7 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes | 3 | 167 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 10.11 [1.91, 53.60] |

| 8 Uterine rupture | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.50, 2.12] |

| 10 Meconium‐stained liquor | 2 | 105 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.28, 1.77] |

| 11 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 2 | 105 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.04, 3.70] |

| 13 Perinatal death | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14 Maternal side effects | 1 | 62 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.82 [0.12, 66.62] |

| 15 Postpartum haemorrhage | 2 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.13, 6.37] |

| 16 Serious maternal complication | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17 Maternal death | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 4 Epidural analgesia.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 5 Cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12‐24 hours.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 6 Oxytocin augmentation.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 7 Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine rupture.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Misoprostol versus placebo/no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 9 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

3.10. Analysis.