Abstract

Background

Bed rest in hospital or at home is widely advised for many complications of pregnancy. The increased clinical supervision needs to be balanced with the risk of thrombosis, the stress on the pregnant women, as well as the costs to families and health services.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effects of bed rest in hospital for women with suspected impaired fetal growth.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (March 2010).

Selection criteria

Randomised trials comparing a policy of bed rest in hospital with ambulatory management for women with suspected impaired fetal growth.

Data collection and analysis

Trial quality was assessed.

Main results

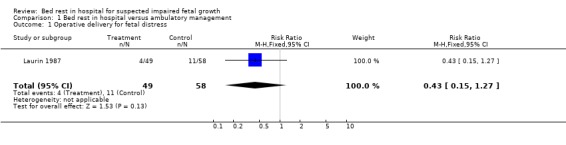

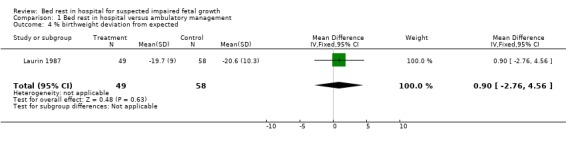

One study involving 107 women was included. Allocation of treatment was by odd or even birth date. There were differences in baseline fetal weights and birthweights, but these were not statistically significant (mean estimated fetal weight deviation at enrolment was ‐21.7% for the bed rest group and ‐20.7% for the ambulatory group; mean birthweight was ‐19.7% for the bed rest group and ‐20.6% for the ambulatory group). No differences were detected between bed rest and ambulatory management for fetal growth parameters (risk ratio 0.43, 95% confidence interval: 0.15 to 1.27) and neonatal outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

There is not enough evidence to evaluate the use of a bed rest in hospital policy for women with suspected impaired fetal growth.

Plain language summary

Bed rest in hospital for suspected impaired fetal growth

Too little evidence from trials to show whether hospital bed rest for pregnant women has a beneficial effect on the unborn baby's growth.

An unborn baby receiving too few nutrients can grow more slowly than expected in the womb (impaired fetal growth). Bed rest is sometimes suggested to mothers of these babies with the view that less maternal physical activity could result in more nutrients for the baby. However, bed rest can be disruptive and there are concerns about an increased risk of maternal blood clotting. This review of one study, involving 107 women, found too little evidence to show whether hospital bed rest for pregnant women is beneficial to the unborn baby. More research is needed into the effects on women and their babies.

Background

Bed rest in hospital or at home is widely advised and prescribed for various pregnancy complications including threatened miscarriage, preterm labour, multiple pregnancy, antepartum haemorrhage, pregnancy hypertension and impaired fetal growth.

Impaired fetal growth is the failure of a newborn to achieve its genetically determined growth potential, which may cause death as well as short or long‐term childhood morbidity. It has been reported that 3% to 10% of neonates are small for corresponding gestational age and an estimated 30% of this is due to impaired fetal growth. The remaining 70% is due to constitutional factors such as maternal ethnicity, parity, weight and height (Lin 1998). The condition occurs with limited flow of nutrients or oxygen, or both, from mother to fetus as a result of fetal (e.g. chromosomal abnormalities, congenital malformations), placental factors (e.g. small placenta), or maternal factors (e.g. malnutrition, vascular/renal disease, drugs or other metabolic conditions) (Resnik 2002).

Ultrasound evaluation of the fetus by measuring the abdominal circumference, head circumference, length of upper leg and interpreting these using standardised formulae allows the clinician to estimate the fetal weight, to relate this to the gestational age and to follow the growth progress. Ultrasound evaluation also allows to some extent to estimate the timing and the cause of the impairment. Symmetrical growth of the fetus is generally due to early problems such as chromosomal abnormalities, drugs, chemical agents or infection. Asymmetric growth usually results from inadequacy of substrates the fetus needs particularly later in pregnancy (Resnik 2002). In low‐income settings where early pregnancy ultrasound is not available fetal growth can be monitored by serial symphysis fundus measurements. However, there is no proven effective treatment that can be applied once growth impairment is diagnosed. In general, when no apparent congenital abnormality exists, management is conservative by frequent growth measurements, smoking cessation if the mother smokes and early delivery when the fetus is thought be mature enough to survive outside the womb.

The outcomes of impaired growth are variable and usually related to the specific cause. For example, if the growth impairment is due to chromosomal anomalies or congenital abnormalities, the fetus is more at risk of a perinatal death. Other short‐term outcomes may be moderate to mild metabolic problems (hypoglycemia, polycythemia, meconium aspiration, etc.) due to the chronic oxygen and nutrient deprivation. Depending on the severity and the duration of the condition, long‐term outcomes may differ from normal to small decreases in IQ to an increased risk of cerebral palsy (Bernstein 2000).

Bed rest during pregnancy is one of the numerous approaches (nutritional supplementation, oxygen therapy, plasma volume expansion, betamimetic drugs) suggested to treat impaired fetal growth. In most cases the main rationale is close clinical supervision to assist early detection of adverse events such as untimely labour, severe bleeding or fetal distress that necessitates intervention. Some clinicians also believe that uteroplacental perfusion may improve with bed rest due to increased venous return and cardiac output. On the other hand, bed rest may increase the likelihood of thrombosis and, in practice, it may be stressful for women with other children at home and costly for the health services. It is also unclear whether good compliance can be achieved (Crowther 1995). It is therefore important to evaluate the effectiveness of bed rest by reviewing the evidence from randomised trials.

Objectives

To assess the effects on fetal growth and perinatal outcome of bed rest for suspected impaired fetal growth.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All acceptably controlled trials comparing bed rest with ambulatory management for suspected impaired fetal growth.

Types of participants

Women with suspected impaired fetal growth.

Types of interventions

Bed rest compared to ambulatory management.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Neonatal outcome as evaluated by size of the babies, Apgar scores, cord blood gases, and the need for operative delivery for fetal distress, maternal experiences with the treatment, thrombovascular complications.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (March 2010).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Trials under consideration were evaluated for methodological quality and appropriateness for inclusion, without consideration of their results. A quality score for concealment of allocation was assigned to each trial using the criteria described in Clarke 2000: (A) adequate concealment of the allocation; (B) unclear whether adequate concealment of the allocation; (C) inadequate concealment of allocation; (D) no concealment of allocation.

Whether or not an 'intention‐to‐treat' analysis was done in the primary study was examined. There were no language preferences in the review.

Included trial data were extracted and processed as described in Clarke 2000.

Results

Description of studies

Risk of bias in included studies

Women with ultrasound‐estimated fetal weight 20% below mean population values at 32 weeks' gestation or 15% at 34 weeks, were allocated according to odd or even birth date (Laurin J ‐ personal communication (Laurin 1987)) to a bed rest in hospital (group A) or ambulant (off work) (group B) group; such a method of allocation is recognised as running risks of biased selection. In other respects the methodology was sound: compliance with allocated management was reasonable (79%) and evaluation was according to original allocation.

Effects of interventions

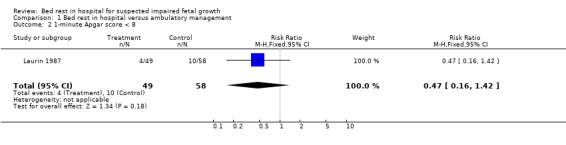

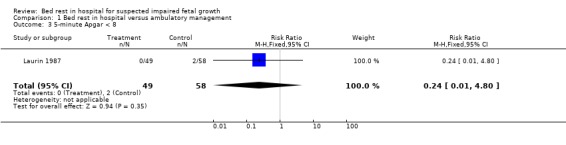

Reporting of the results are based on the deviations from the standard curve of the total population. Mean estimated fetal weight deviations at enrolment were ‐21.7% and ‐20.7% for groups A and B respectively. Mean birthweight deviations were ‐19.7% and ‐20.6%. These differences were not statistically significant, but given the small numbers studied, the possibility of a type two error needs to be entertained. Mean gestational ages and sizes at delivery were similar in both groups. There was a trend towards fewer operative deliveries for fetal distress and low one minute Apgar scores in the bed rest group but these differences could reflect the play of chance.

Discussion

Hospitalisation for bed rest is widely practiced without any scientific evidence of its benefit. It is expensive and inconvenient for the couples. The trial of Laurin et al (Laurin 1987) is too small to address this question adequately.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is at present no well‐controlled evidence that bed rest in hospital promotes fetal growth, but the numbers studied to date are too small to exclude that possibility with any degree of certainty. It is imperative that hospitalisation for bed rest is used only in the context of controlled trials.

Implications for research.

Because of the enormous financial and personal costs of prolonged hospitalisation, this form of management should only be used in the context of well‐designed controlled trials to test its effectiveness.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 23 April 2010 | New search has been performed | Search updated. No new trials identified. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1995 Review first published: Issue 1, 1995

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 February 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 28 October 2007 | New search has been performed | Search updated but no new trials identified. |

| 24 November 2006 | New search has been performed | Search updated but no new trials identified. |

| 30 June 2004 | New search has been performed | Search updated but no new trials identified. |

| 29 December 1994 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

None.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Bed rest in hospital versus ambulatory management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Operative delivery for fetal distress | 1 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.15, 1.27] |

| 2 1‐minute Apgar score < 8 | 1 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.47 [0.16, 1.42] |

| 3 5‐minute Apgar < 8 | 1 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.01, 4.80] |

| 4 % birthweight deviation from expected | 1 | 107 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [‐2.76, 4.56] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bed rest in hospital versus ambulatory management, Outcome 1 Operative delivery for fetal distress.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bed rest in hospital versus ambulatory management, Outcome 2 1‐minute Apgar score < 8.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bed rest in hospital versus ambulatory management, Outcome 3 5‐minute Apgar < 8.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bed rest in hospital versus ambulatory management, Outcome 4 % birthweight deviation from expected.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Laurin 1987.

| Methods | Quasi‐random. Odd and even birthdates. | |

| Participants | 101 women with ultrasound‐estimated fetal weight 20% below mean population values at 32 weeks' gestation or 15% at 34 weeks. 49 women were assigned to the intervention and 58 were assigned to the control arm. | |

| Interventions | Bed rest in the hospital (group A) was compared to ambulatory (off‐work) management (group B). | |

| Outcomes | Size at birth, Apgar scores, cord pH and operative delivery for fetal distress. | |

| Notes | 15 women in group A refused hospitalisation and 8 women in group B had to be hospitalised for other medical reasons (79% compliance rate). Non‐compliers are included in the results. | |

Contributions of authors

Justus Hofmeyr wrote the original review for the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database. Metin Gülmezoglu updated the review, and has been responsible for maintaining the review since 1995. Both review authors did the data extraction and contributed to the text of the review. Lale Say contributed to the recent update by checking the data entries and revising the text of the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa.

UK Cochrane Centre, NHS R&D Programme, Oxford, UK.

HRP ‐ UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme in Human Reproduction, Geneva, Switzerland.

External sources

National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, Oxford, UK.

The Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, London, UK.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Laurin 1987 {published data only}

- Laurin J, Persson PH. The effect of bedrest in hospital on fetal outcome in pregnancies complicated by intra‐uterine growth retardation. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1987;66:407‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Bernstein 2000

- Bernstein IM, Horbar JD, Badger GJ, Ohlsson A, Golan A. Morbidity and mortality among very low birth weight infants with intrauterine growth restriction. The Vermont Oxford Network. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;182:198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clarke 2000

- Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane Reviewers’ Handbook 4.1 [updated June 2000]. In: Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 4.1. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Crowther 1995

- Crowther CA. Commentary: Bedrest for women with pregnancy problems: evidence for efficacy is lacking. Birth 1995;22:13‐4. [Google Scholar]

Lin 1998

- Lin C, Santolaya‐Forgas J. Current concepts of fetal growth restriction: Part 1. Causes, classification, and pathophysiology. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1998;92(6):1044‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Resnik 2002

- Resnik R. Intrauterine growth restriction. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2002;99(3):490‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]