Abstract

Background

Acupuncture has traditionally been used to treat asthma in China and is used increasingly for this purpose internationally.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effects of acupuncture for the treatment of asthma or asthma‐like symptoms.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register (last searched August 2008), the Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field trials register, AMED, and reference lists of articles. We also contacted trialists and researchers in the field of complementary and alternative medical research.

Selection criteria

Randomised and possibly randomised trials using needle acupuncture or other forms of stimulation of acupuncture. Any form of control treatment was considered (no treatment in addition to conventional asthma treatment, sham or placebo interventions, active comparator interventions). Studies were included provided outcome was assessed at one week or more.

Data collection and analysis

At least two reviewers independently assessed trial quality. A reviewer experienced in acupuncture assessed the adequacy of the active and sham acupuncture used in the studies. Study authors were contacted for missing information.

Main results

Twelve studies met the inclusion criteria recruiting 350 participants. Trial reporting was poor and trial quality was deemed inadequate to generalise findings. There was variation in the type of active and sham acupuncture, the outcomes measured and time‐points presented. The points used in the sham arm of some studies are used for the treatment of asthma according to traditional Chinese medicine. Two studies used individualised treatment strategies and one study used a combination strategy of formula acupuncture with the addition of individualised points. No statistically significant or clinically relevant effects were found for acupuncture compared to sham acupuncture. Data from two small studies were pooled for lung function (post‐treatment FEV1): Standardised Mean Difference 0.12, 95% confidence interval ‐0.31 to 0.55).

Authors' conclusions

There is not enough evidence to make recommendations about the value of acupuncture in asthma treatment. Further research needs to consider the complexities and different types of acupuncture.

Plain language summary

Acupuncture for chronic asthma

Acupuncture is a treatment originating from traditional Chinese medicine. It consists of the stimulation of defined points on the skin (mostly by insertion of needles). The objective of this review was to assess whether there is evidence from randomised controlled trials that asthma patients benefit from acupuncture. The studies included in the review were of variable quality and had inconsistent results. Future research should concentrate on establishing whether there is a non‐specific component of acupuncture which benefits recipients of treatment. There should be an assessment not merely of placebo treatment, but also of 'no treatment' as well. There is insufficient evidence to make recommendations about the value of acupuncture as a treatment for asthma based on current evidence.

Background

Bronchial asthma is a major health problem and has a significant mortality. Data on the prevalence of asthma vary between 3% and 6% for adults and between 8% and 12% in children and suggest an increasing incidence within recent years. Although the symptoms can be controlled by drug treatment in most patients, effective low‐risk, non‐drug strategies could constitute a significant advance in asthma management.

Acupuncture is a form of therapy derived from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) involving the stimulation of points on the body with the use of needles, for therapeutic or preventative purposes. The points are derived from TCM theory and relate to the meridians, a system that purportedly allows the flow of 'Qi' through the body, blockages of which are thought to cause health problems. As the use of acupuncture has become more prevalent in the West these theories have been developed to fit in with a Western understanding of bodily function: for example needling is thought to reduce local muscle tension or release pain‐killing endorphins (Green 2002). Other methods of stimulation are traditionally used, such as the use of pressure (acupressure), and others have been developed (e.g. laser), and for the purposes of this review they have been included. One important but under‐researched aspect of treatment is the subjective element of this complex therapy. This is shared with a number of other therapies involving one‐to‐one session work, such as pulmonary rehabilitation. It is very difficult to remove acupuncture treatment from its context and this has not been addressed in existing research.

Acupuncture has traditionally been used in asthma treatment in China and is increasingly applied for this purpose in Western countries. In 1991 Kleijnen et al. (Kleijnen 1991) published a systematic review of the controlled clinical trials in asthma. They concluded that claims for the effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of asthma are not based on the results of well performed clinical trials. Unfortunately, this review was limited mainly to an assessment of methodological quality and gave little information on what was investigated in the primary studies. Results of primary studies were categorized only as positive or negative (vote count), a method which may have low validity.

Two overviews have been published (Jobst 1995; Linde 1996), which formed the initial version of this Cochrane review. A recent meta‐analysis examined acute effects of acupuncture as well as longer term efficacy (Martin 2002).

Objectives

The objective of the review was to evaluate the effectiveness of acupuncture for the treatment of bronchial asthma from the reported literature.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

Patients of any age with asthma.

Types of interventions

All interventions adjunctive to a conventional asthma treatment: (1) in which needles were inserted at acupuncture points or other defined points for therapeutic purposes; or (2) in which defined acupuncture points were stimulated in another way (pressure, laser etc.).

For the update of the review we have excluded non‐placebo controlled trials due to the likely bias associated with studies where no attempt to blind study participants to treatment group has been undertaken. This may be of particular concern in acupuncture studies where non‐specific effects of treatment need to be controlled for (Higgins 2006).

The duration of treatment had to be > 1 week. This was to exclude patients with acute asthma, or studies which assessed short‐term effects of the treatment in chronic asthma.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome

Lung function (peak expiratory flow rates (PEFR), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC))

Secondary outcomes

Medication use

Quality of life

Exacerbations

Global assessment.

Symptoms

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Trials were identified using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials, which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL, and handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts. All records in the Specialised Register coded as 'asthma' were searched using the following terms:

Acupunctur* or acupressur* or acupoint

The most recent search was carried out in August 2008.

Searching other resources

The Alternative Medicine Electronic Database (AMED) was also searched. Additionally, we checked the trial database of the Cochrane Field for Complementary Medicine and reference lists of published reviews. Additional handsearching was carried out. We established automated citation alerts and contacted trialists and researchers in the field of complementary and alternative medical research.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

At least two of the four reviewers independently assessed search results, eligibility and selected studies for inclusion in the review. Initial disagreements occurred for two papers but could be resolved by discussion.

We considered each active intervention to determine whether the acupuncture being administered consisted of stimulation by needle or by laser of indicated acupuncture points. We also determined the extent to which the sham acupuncture could be construed as an active stimulation of non‐acupuncture points or whether it involved non‐stimulation of any points. Studies where active was compared with non‐stimulation of active points (potentially a double‐blind study) were analysed separately from studies where active was compared with stimulation of non‐active points. Attempts to achieve de qi sensation were noted. Please see Characteristics of Included Studies for further details.

Data extraction and management

We extracted descriptive characteristics and study results using a standard form. We also sent letters asking for additional information to all first authors in August 1996. Only two responded and only one could provide additional information. For the update of the review in 2003, we contacted study authors of three newly identified trials. All three responded with information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

At least two reviewers assessed concealment of randomisation, blinding of patients and evaluators, and likelihood of selection bias after randomisation, (whether intention to treat analysis was carried out), and disagreements were resolved by discussion. In addition one reviewer assessed quality of reporting using the score by Jadad et al (Jadad 1996).

Data synthesis

For continuous variables reported as means and standard deviations (SDs), we extracted data in order to calculate either a weighted mean difference (WMD) or standardised mean difference (SMD), depending upon whether studies measured outcome on the same or different metrics. Where the difference between the means for treatment and control groups was reported, we calculated a treatment effect estimate based upon the generic inverse variance (GIV). For dichotomous variables, we extracted data in order to calculate a relative risk (RR).

Fixed‐effect modelling was used in the calculation of the pooled treatment effect estimates unless significant heterogeneity was observed (P ≤ 0.1), in which case a random‐effects model was also used to calculate the effect estimate.

Data from parallel and crossover studies were analysed separately.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was not undertaken in the first version of this review. For the update, the reviewers chose to stratify the data on the basis of age (Adults versus children).

For future versions of this review, we will attempt to allow for the complexity of the intervention by performing sensitivity analyses based upon attempt to achieve 'de qi' sensation, trial quality and duration of treatment (one session versus greater than one session), where possible.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

For details of search history, see Table 1. An update search in August 2008 identified 36 references. One study was identified from the references which met the eligibility criteria of the review (Najafizadeh 2006).

1. Search history.

| Date | References |

| All years | From a large number of papers on acupuncture and asthma screened we identified 21 controlled clinical trials. At least two of the three original reviewers independently assessed eligibility and selected seven studies for inclusion in the review. The main reasons for exclusion were short observation periods (i.e. studies on induced/spontaneous asthma attacks) and non‐random allocation (see reasons for exclusions in the table of excluded studies). Trials with short observation periods do not seem relevant for the primary objective of this review as acupuncture is primarily used as an adjuvant therapy in the long‐term treatment of asthma. These trials have been summarized in the reviews by Jobst (Jobst 1995) and Linde et al. (Linde 1996). |

| August 2003 | We identified sixty‐four references from electronic searches and alerts, of which ten studies were retrieved. Five met the inclusion criteria (Biernacki 1998; Joos 2000; Malmström 2002; Medici 2002; Shapira 2002) and four were excluded from the review (Choudhury 1989; Maa 1997; Eber 2001; Gruber 2002; Karst 2002 ‐ please see "Table of characteristics of excluded studies"). One study is awaiting assessment due to inadequate reporting (Abdel Khalek 1999). One study was excluded that had previously been included (Jobst 1986) as the study recruited people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). |

| August 2004‐5 | 23 references identified, 2 retrieved. Both were excluded (Ailioaie 1999 and Ailioaie 2000) |

| August 05‐06 | 0 references identified |

| August 2006‐2007 | 3 references identified 3 references retrieved Excluded: 3 (methods not sufficient to determine quality (N = 1); addition of therapy to acupuncture not given to control group (N = 1); no sham intervention in control group (N = 1) |

Included studies

In total 12 studies (22 references) are now included in this review. For full description of each included study see Characteristics of included studies.

Study design

All studies were described as randomised, except for the Hirsch 1994 study (in which randomisation was not specifically described but likely). Tashkin 1985; Tandon 1991; Hirsch 1994; Biernacki 1998; Shapira 2002 were crossover studies, and the remaining studies were of a parallel group design. Blinding of participants and evaluators was described in Dias 1982; Christensen 1984; Tashkin 1985; Mitchell 1989; Tandon 1991; Hirsch 1994; Biernacki 1998; Medici 2002; Shapira 2002.

Sample sizes

A total of 350 participants were recruited to the studies in the review. The sample sizes varied between 17 and 66.

Participant characteristics

Asthma was defined as reversible airways obstruction. Criteria varied between trials with four trials using guidelines for the definition of asthma: either ATS 1985 criteria (Tandon 1991; Hirsch 1994); GINA 2002 (Medici 2002); or Deutsche Atemwegsliga criteria (Joos 2000). Other trialists used lung function (Christensen 1984; Tashkin 1985; Biernacki 1998; Malmström 2002; Shapira 2002) or poor response to Western drugs (Dias 1982). All studies recruited adult participants with the exception of Hirsch 1994 who recruited children only. Tashkin 1985 recruited a mixed population. We could not ascertain how asthma was defined in Najafizadeh 2006.

Samples were comprised of patients of varying characteristics. Although it was not clear in all cases, we have assumed that all participants were outpatients drawn from a variety of hospital settings.

Severity of asthma was mild to moderate in all studies except Tashkin 1985, who recruited moderate to severe asthmatic participants, controlled with oral steroids, theophylline and beta‐agonists.

Intervention characteristics ‐ experimental group

The acupuncture strategies used differed considerably between trials. We analysed laser and needle acupuncture separately. In nine trials needle acupuncture was used (Dias 1982; Christensen 1984; Tashkin 1985; Mitchell 1989; Biernacki 1998; Joos 2000; Malmström 2002; Medici 2002; Shapira 2002). In three trials stimulation was carried out using lasers (Tandon 1991; Hirsch 1994; Najafizadeh 2006). Eight trials used formula acupuncture (identical points for all patients ‐ Dias 1982; Christensen 1984; Tashkin 1985; Mitchell 1989; Tandon 1991; Hirsch 1994; Biernacki 1998; Medici 2002), but formulas differed strongly between trials. In two trials individualised acupuncture points were used according to the theory of traditional Chinese medicine (Joos 2000; Shapira 2002). One study used a mixture of individualised and formula (Malmström 2002).

Of the nine studies using needle acupuncture, six stated that they sought the de qi sensation (Christensen 1984; Tashkin 1985; Mitchell 1989; Joos 2000; Malmström 2002; Shapira 2002).

Intervention characteristics ‐ sham acupuncture group

All trials included a sham comparison group. Of the needle acupuncture studies two used points not indicated for asthma as controls (Mitchell 1989; Joos 2000). Six stimulated points on the body not considered active acupuncture points (Dias 1982; Christensen 1984; Tashkin 1985; Biernacki 1998; Medici 2002; Shapira 2002). One used a pseudo‐intervention (Malmström 2002 ‐ inactive TENS machine). One study included a non‐treatment control group in addition to a sham acupuncture group (Medici 2002).

However according to Chinese medicine, some of these points might have some treatment effect, so they might not be considered to be fully inert placebo strategies.

The three laser acupuncture studies (Tandon 1991; Hirsch 1994; Najafizadeh 2006) utilised pseudo‐interventions as sham acupuncture (switched off lasers).

Two studies attempted to attain the de qi sensation in the control group (Tashkin 1985; Mitchell 1989).

Outcome assessment

All the studies reported data on lung function with the exception of Joos 2000. Outcomes were not reported uniformly and pooling results was possible for only two outcomes. Secondary outcomes reported included medication usage and symptom scores. Five authors replied to requests for data, and four provided additional relevant information.

Risk of bias in included studies

No study explicitly described the method of randomizations concealment, although contact with one author provided a description of adequate concealment. All trials attempted to blind patients and evaluators except for Joos 2000; Malmström 2002 in which only patients were blinded. Although description of drop‐outs and withdrawals was adequate in six studies (Hirsch 1994; Biernacki 1998; Joos 2000; Malmström 2002; Medici 2002; Shapira 2002), no study reported the results of an intention‐to‐treat population, which, given the small sample size of the trials poses a threat to the validity of the results. Experience and training of the acupuncture therapist was unclear in most studies.

Clinical outcomes were measured in all the studies although only one study attempted to measure quality of life with a validated questionnaire (Biernacki 1998) Two studies assessed improvement with a global rating of well being (Dias 1982; Joos 2000).

There was considerable variation in the strategies of acupuncture (in particular type and frequency).

Effects of interventions

Data have been stratified by age (adults and children). Insufficient data were presented for subgroup analysis.

NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE

Dias 1982; Christensen 1984; Tashkin 1985 ; Mitchell 1989; Biernacki 1998; Joos 2000; Medici 2002; Shapira 2002.

Lung Function

(Dias 1982; Christensen 1984; Tashkin 1985; Mitchell 1989; Biernacki 1998; Joos 2000; Medici 2002; Shapira 2002)

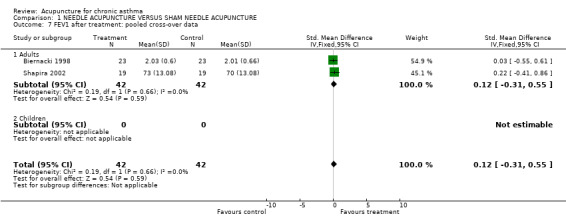

Studies measured lung function at varying points in time, however data were pooled for FEV1 after treatment with acupuncture or sham. No significant difference was observed (SMD 0.12, 95% CI ‐0.31 to 0.55) (Biernacki 1998; Shapira 2002).

No other data could be combined on any other lung function variable. All the remaining studies reported non‐significant findings.

Medication use

Dias 1982; Christensen 1984; Tashkin 1985; Mitchell 1989; Biernacki 1998; Joos 2000; Medici 2002; Shapira 2002

Drug use was monitored in different ways (as absolute values and as change from baseline scores). Seven of the eight needle acupuncture studies attempted to monitor drug use. However, actual data were presented in seven studies (Dias 1982; Christensen 1984; Tashkin 1985; Biernacki 1998; Malmström 2002; Shapira 2002), and monitoring and assessment methods differed fundamentally, precluding meta‐analysis. Two trials (Christensen 1984; Joos 2000) found statistically significant decreases in medication usage versus sham treatment (Christensen 1984 p = 0.001; Joos 2000 values not reported).

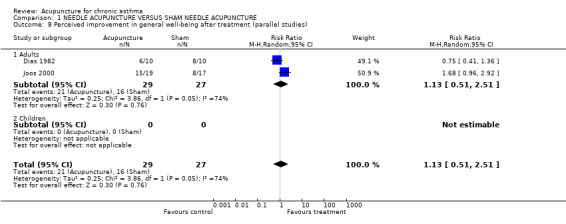

Subjective measurements

All trials attempted to monitor subjective symptoms in some way. Again, differing methods and data presentation meant only limited meta‐analysis was possible. Two trials measured perceived improvement in overall well‐being (Dias 1982; Joos 2000), with no significant difference between sham and active acupuncture observed on the likelihood of improvement (RR: 1.13, 95% CI 0.51 to 2.51]). Significant heterogeneity was present (I2 74.1%). However, both studies crossed the line of no difference and neither fixed effect nor random effect modelling gave a significant result.

Biernacki 1998 measured AQLQ (asthma quality of life questionnaire) scores and detected a significant improvement after treatment in both groups (active treatment: P = 0.003; sham treatment: P = 0.005). As this was a crossover study, a carry‐over effect should not be ruled out.

Symptoms were measured separately in four studies (Christensen 1984; Tashkin 1985; Mitchell 1989; Shapira 2002). No significant differences between treatment and sham acupuncture were observed in Tashkin 1985; Mitchell 1989; Shapira 2002. Christensen 1984 reported a significant decrease in daily symptom score versus placebo (P < 0.05), but baseline values were higher in the active treatment group. However, weekly scores were significantly higher in the active treatment group compared with placebo at week four (P < 0.05) after which no difference was observed. No significant differences were observed between baseline values and measurements taken throughout the study in the sham acupuncture group on either daily or weekly symptom scores.

LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE

Tandon 1991; Hirsch 1994; Najafizadeh 2006

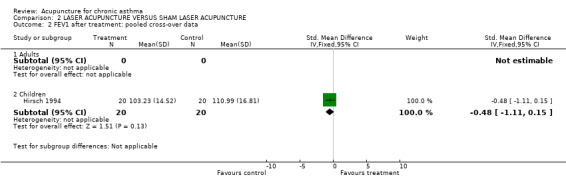

Lung function

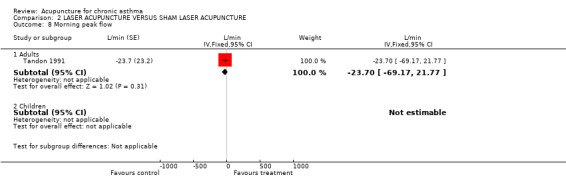

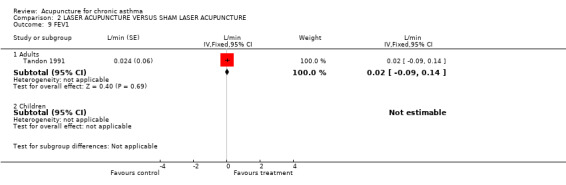

Tandon 1991 did not detect a significant difference in change scores for morning or evening peak flow, nor for FEV1.

Hirsch 1994 did not detect a significant difference in change scores in active versus baseline scores on morning or evening peak flow, or PC20. A significant decrease in FEV1% predicted was detected (113.6% versus 103.23%). No significant differences were detected between sham treatment and baseline for morning or evening peak flow, FEV1% predicted and PC20.

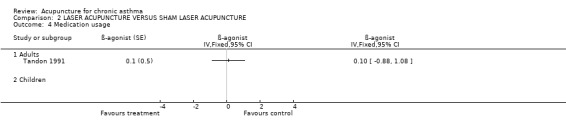

Medication usage

Tandon 1991 presented data as mean difference change from baseline scores (treatment versus run‐in; sham versus run‐in), as such these could not be used as either WMD or GIV variables. Non‐significant differences were observed for ß‐agonist use

Hirsch 1994 did not measure medication usage.

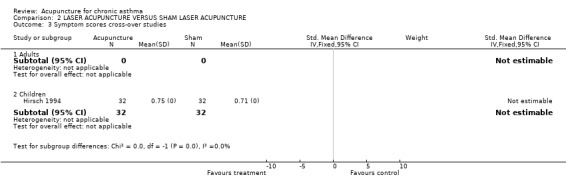

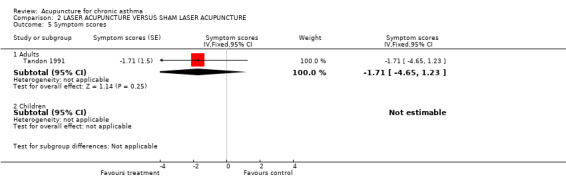

Subjective measurements

Tandon 1991 did not detect a significant difference on symptom scores.

Hirsch 1994 did not detect a significant difference on symptom scores compared with baseline for both treatments (active: 0.75 versus 0.75, P = 1; sham: 0.71 versus 0.71, P = 1).

NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE

Lung function

No significant difference was observed between treatment and control groups on morning peak flow at 90 days.

Medication usage

No significant difference was observed between treatment and control groups medication usage at 90 days.

Discussion

Twelve randomised clinical trials with a total of 350 patients, comparing needle or laser acupuncture with some form of dummy acupuncture in addition to standard maintenance medication, met the inclusion criteria of this review. Differences in study design, outcome and intervention meant that data could be pooled for only two outcomes comparing needle acupuncture with sham needle acupuncture (PEFR and global assessment of well being). Both outcomes did not show a statistically and clinically difference between active treatment and control. Although we did pool data for two outcomes which involved two small studies, there were insufficient data available to facilitate extrapolation of the effects of acupuncture to the general population level.

The validity of real and sham acupuncture used in the studies merits comment. It could be questioned whether the acupuncture used in the studies is representative of that used in practice. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and Western formula acupuncture were used in the studies for this review. A major issue complicating the evaluation and integration of acupuncture in the western world is the model of treatment. If applied according to the principles of traditional Chinese medicine, acupuncture often comes as part of a package of care that includes diet and herbal medicines. The acupuncturist may modify the sites in different patients with asthma, as according to the traditional Chinese nosology these patients may have different disorders. From a western perspective such a treatment seems "individualized". Outside China, "standardized" treatment strategies are frequently used. These strategies are more compatible with western thinking. However, as a growing number of western acupuncturists also apply traditional Chinese strategies, a deliberate restriction to evaluating only the "standardized" model might not be adequate.

Although the focus of this review differs slightly from that of Martin 2002, the conclusions, and in particular the implications for research, largely echo the findings of that review. This review highlights the fact that any trial or investigation of acupuncture is a complex challenge and that many different parameters need to be controlled for and investigated. For example, needle depth, type of needle manipulation (manual, electrical stimulation, moxibustion etc), siting of needles, induction of de qi (an irradiating sensation after needling thought to indicate effective needling), duration of insertion, duration of stimulation, use of standardised formulae versus individualised prescribing, to cite but a few. Researchers would therefore be well advised to consult widely and in particular to take advice from those who have knowledge of the different styles of acupuncture practice and of trial design and methodology. Adherence to the STandards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA) guidelines could help to elucidate the validity of future clinical trials (MacPherson 2001).

Furthermore the included studies utilised different sham strategies as control treatments, including needling at non‐points (i.e. points on the body where acupuncture is not considered to be effective) and needling at non‐indicated points (i.e. a true acupuncture point not indicated for asthma). Some would argue that needling of non‐points may produce a therapeutic effect (White 2001). However, testing whether there is genuinely different response across these potentially different forms of control is undermined by different interventions, study designs, patient samples and outcomes measured. Birch 2002; Martin 2002; Dincer 2003 argue that pooling trials with different controls as described in the included studies of this review would be methodologically unsound. Further research into what constitutes an acceptable control procedure, and whether there are non‐specific benefits associated with an acupuncture treatment 'package' (e.g. holistic consultation, and different approach to patients' disease) should help to elucidate this issue further.

None of the included studies reported data on side‐effects and tolerability. Few trials specifically evaluated the side‐effect and morbidity profile of acupuncture treatments, but some have drawn attention to the complications which may follow acupuncture treatment (Jobst 1995; Ernst 1996; Jobst 1996; Norheim 1996).

There is inconclusive evidence to indicate that short term (1 to 12 weeks) acupuncture treatment has a significant effect on the course of asthma when used in conjunction with drug maintenance treatment. Furthermore, the severity of participants included in this review was mild to moderate, and so extrapolating the findings to the general population is not possible. The subgroup analysis performed in this review was inadequately powered to detect a difference between adults and children. Therefore more research is required before the response to treatment according to both age and severity can be assessed adequately. Some studies did report significant positive changes in subjective parameters, and medication use, which suggest that some patients with asthma may benefit from acupuncture. However, due to fundamental differences between trials and inadequate data presentation little of the data were suitable for meta‐analysis.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

On the basis of this review, no recommendations could be made for the practice of acupuncture.

Implications for research.

There is an urgent need for information on the different ways in which acupuncture is practiced and might be evaluated in order that appropriate trials can be designed. The methodological inconsistencies and problems encountered in all the trials reported to date indicate that more pilot data should be acquired before proceeding to any large scale randomised trials. In particular, researchers should pay attention to the nature of sham/control points selected since in a number of the studies the control points selected can be used for the treatment of asthma according to Traditional Chinese Acupuncture practice. Future trials should attempt to include a no‐treatment control arm, in addition to active and sham groups.

Acupuncture should also be assessed in the context of more severe asthma, in order to be able to generalise the findings of more rigorously conducted and reported clinical research.

Attention needs to be paid to the nature or style of acupuncture used (for a introduction to acupuncture see Stux 1997; Helms 1998). The available evidence does not allow objective comparison between different acupuncture types. Therefore, it is not possible to comment on claims by proponents of any technique or style that any one is better than any other.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 April 2009 | Amended | Technical problem identified with software; amended by external programmer. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1996 Review first published: Issue 2, 1997

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 August 2008 | New search has been performed | New literature search run. One new study identified: this did not change the conclusions of the review. |

| 26 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 11 March 2003 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Five new studies were identified for the 2003 update of this review (Biernacki 1998; Joos 2000; Malmstrom 2002; Medici 2002; Shapira 2002). One study previously included was deemed not to have met the inclusion criteria for the review as it was carried out in COPD patients. The Description of studies, Methodological Quality of Included Studies, Results and Discussion sections were substantially revised, to reflect the need for more focused clinical trials. Following the inclusion of these studies data could be pooled for two outcomes (lung function and improvement in well‐being). These did not alter the conclusions of the review. |

Acknowledgements

The reviewers would like to thank the following authors from the following studies for corresponding with them in their attempts to gain additional data/information: Malmström 2002 (Christer Carlsson); Medici 2002 (Tullio Medici) and Shapira 2002 (Raphael Breuer). We would also like to thank Karen Blackhall, Jo Picot and Sarah Tracy for logistical/technical support for the review from the Cochrane Airways Group Editorial Base. We would like to thank Sylvia Beamon from the Cochrane Airways Group Consumer Panel for assessing the consumer synopsis and suggesting changes. Thanks to Kirsty Olsen for copyediting the review.

The Donald Lane Trust and the Oxfordshire Health Authority supported the initial version of this review.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

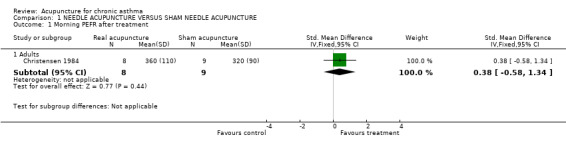

| 1 Morning PEFR after treatment | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Adults | 1 | 17 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [‐0.58, 1.34] |

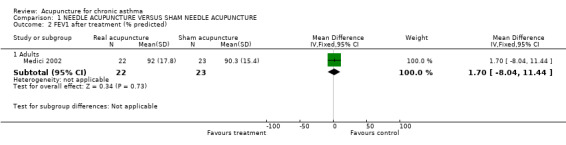

| 2 FEV1 after treatment (% predicted) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Adults | 1 | 45 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.70 [‐8.04, 11.44] |

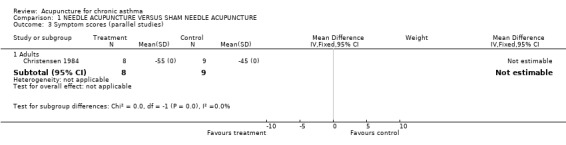

| 3 Symptom scores (parallel studies) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Adults | 1 | 17 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

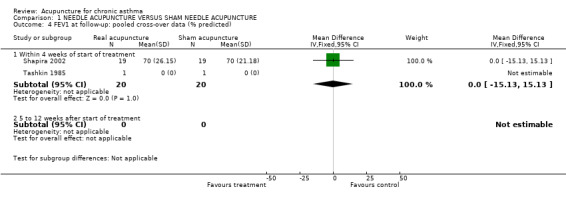

| 4 FEV1 at follow‐up: pooled cross‐over data (% predicted) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Within 4 weeks of start of treatment | 2 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐15.13, 15.13] |

| 4.2 5 to 12 weeks after start of treatment | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

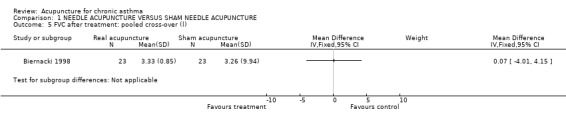

| 5 FVC after treatment: pooled cross‐over (l) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

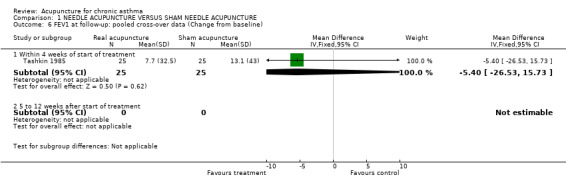

| 6 FEV1 at follow‐up: pooled cross‐over data (Change from baseline) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Within 4 weeks of start of treatment | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.40 [‐26.53, 15.73] |

| 6.2 5 to 12 weeks after start of treatment | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 FEV1 after treatment: pooled cross‐over data | 2 | 84 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.12 [‐0.31, 0.55] |

| 7.1 Adults | 2 | 84 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.12 [‐0.31, 0.55] |

| 7.2 Children | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Perceived improvement in general well‐being after treatment (parallel studies) | 2 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.51, 2.51] |

| 8.1 Adults | 2 | 56 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.51, 2.51] |

| 8.2 Children | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

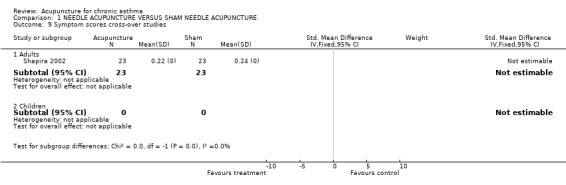

| 9 Symptom scores cross‐over studies | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Adults | 1 | 46 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.2 Children | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

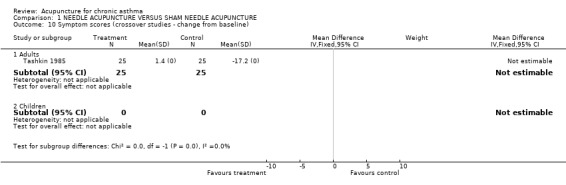

| 10 Symptom scores (crossover studies ‐ change from baseline) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 Adults | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.2 Children | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

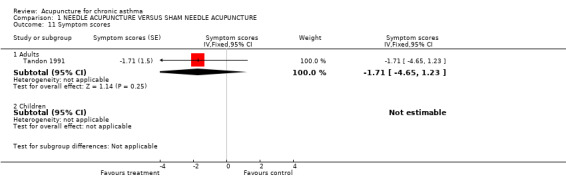

| 11 Symptom scores | 1 | Symptom scores (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 11.1 Adults | 1 | Symptom scores (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.71 [‐4.65, 1.23] | |

| 11.2 Children | 0 | Symptom scores (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

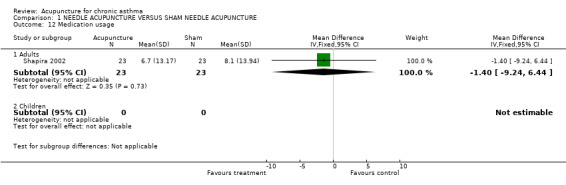

| 12 Medication usage | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 12.1 Adults | 1 | 46 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.40 [‐9.24, 6.44] |

| 12.2 Children | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

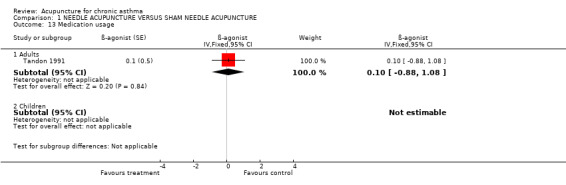

| 13 Medication usage | 1 | ß‐agonist (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 13.1 Adults | 1 | ß‐agonist (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.1 [‐0.88, 1.08] | |

| 13.2 Children | 0 | ß‐agonist (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

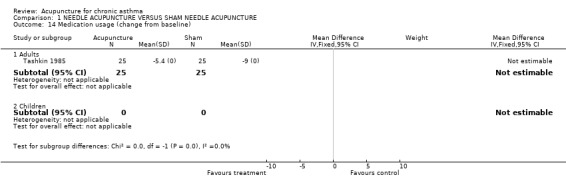

| 14 Medication usage (change from baseline) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 14.1 Adults | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14.2 Children | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

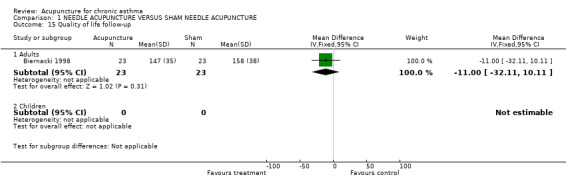

| 15 Quality of life follow‐up | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 15.1 Adults | 1 | 46 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐11.0 [‐32.11, 10.11] |

| 15.2 Children | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 1 Morning PEFR after treatment.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 2 FEV1 after treatment (% predicted).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 3 Symptom scores (parallel studies).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 4 FEV1 at follow‐up: pooled cross‐over data (% predicted).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 5 FVC after treatment: pooled cross‐over (l).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 6 FEV1 at follow‐up: pooled cross‐over data (Change from baseline).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 7 FEV1 after treatment: pooled cross‐over data.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 8 Perceived improvement in general well‐being after treatment (parallel studies).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 9 Symptom scores cross‐over studies.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 10 Symptom scores (crossover studies ‐ change from baseline).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 11 Symptom scores.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 12 Medication usage.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 13 Medication usage.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 14 Medication usage (change from baseline).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 15 Quality of life follow‐up.

Comparison 2. LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

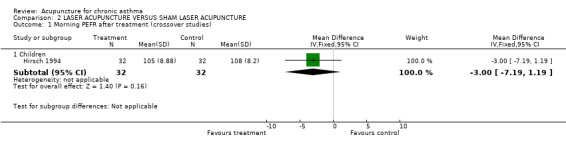

| 1 Morning PEFR after treatment (crossover studies) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Children | 1 | 64 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.0 [‐7.19, 1.19] |

| 2 FEV1 after treatment: pooled cross‐over data | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Adults | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 Children | 1 | 40 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.48 [‐1.11, 0.15] |

| 3 Symptom scores cross‐over studies | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Adults | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.2 Children | 1 | 64 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Medication usage | 1 | ß‐agonist (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Adults | 1 | ß‐agonist (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Children | 0 | ß‐agonist (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Symptom scores | 1 | Symptom scores (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Adults | 1 | Symptom scores (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.71 [‐4.65, 1.23] | |

| 5.2 Children | 0 | Symptom scores (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

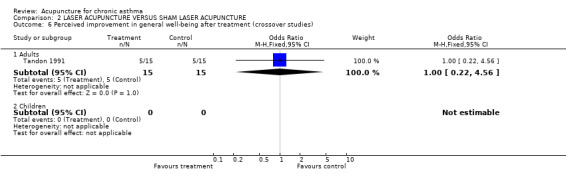

| 6 Perceived improvement in general well‐being after treatment (crossover studies) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Adults | 1 | 30 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.22, 4.56] |

| 6.2 Children | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

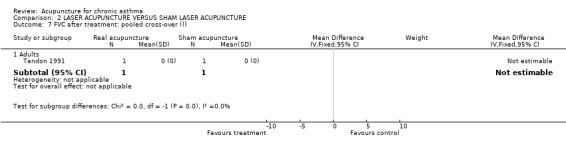

| 7 FVC after treatment: pooled cross‐over (l) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Adults | 1 | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Morning peak flow | 1 | L/min (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 Adults | 1 | L/min (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐23.7 [‐69.17, 21.77] | |

| 8.2 Children | 0 | L/min (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 9 FEV1 | 1 | L/min (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Adults | 1 | L/min (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.09, 0.14] | |

| 9.2 Children | 0 | L/min (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

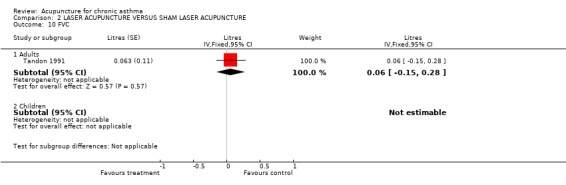

| 10 FVC | 1 | Litres (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 Adults | 1 | Litres (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.15, 0.28] | |

| 10.2 Children | 0 | Litres (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

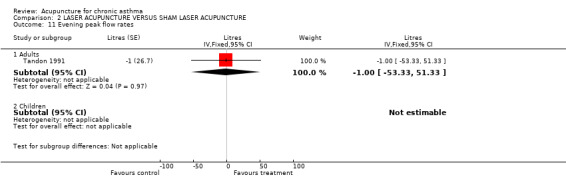

| 11 Evening peak flow rates | 1 | Litres (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 11.1 Adults | 1 | Litres (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.0 [‐53.33, 51.33] | |

| 11.2 Children | 0 | Litres (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 1 Morning PEFR after treatment (crossover studies).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 2 FEV1 after treatment: pooled cross‐over data.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 3 Symptom scores cross‐over studies.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 4 Medication usage.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 5 Symptom scores.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 6 Perceived improvement in general well‐being after treatment (crossover studies).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 7 FVC after treatment: pooled cross‐over (l).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 8 Morning peak flow.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 9 FEV1.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 10 FVC.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 LASER ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 11 Evening peak flow rates.

Comparison 3. NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

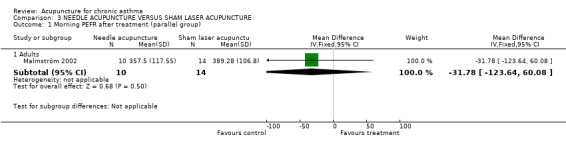

| 1 Morning PEFR after treatment (parallel group) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Adults | 1 | 24 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐31.78 [‐123.64, 60.08] |

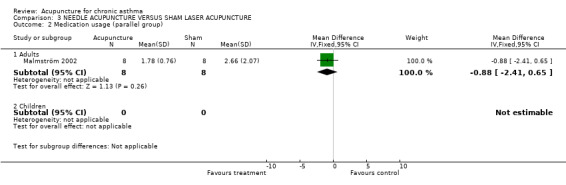

| 2 Medication usage (parallel group) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Adults | 1 | 16 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.88 [‐2.41, 0.65] |

| 2.2 Children | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 1 Morning PEFR after treatment (parallel group).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NEEDLE ACUPUNCTURE VERSUS SHAM LASER ACUPUNCTURE, Outcome 2 Medication usage (parallel group).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Biernacki 1998.

| Methods | Design: cross‐over Drop‐outs/withdrawals: 1 for exacerbation Jadad score: 1‐1‐1 Study schedule: 2 months run‐in, treatment on one day, follow‐up 2 weeks, then crossed over | |

| Participants | Number of patients randomized/analyzed: 23/22 Diagnosis: mild to moderate asthma, >15% improvement in lung function after inhaled bronchodilator Demographics: 13 female, mean age 43+/‐15 Setting: secondary care, one chest unit in UK FEV1 59+/‐16% predicted. All receiving inhaled beta2‐agonist, 21/23 on inhaled steroids. Other therapies include inhaled ipratropium bromide 7/23, 5/23 on long‐term inhaled steroids. Inclusion criteria: non‐smokers, reversible airways obstruction, stable during 2 months prior to trial entry. Exclusion criteria inadequately described. | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture group: Standardized "real" acupuncture (n = 23) using the single point REN‐17. Disposable 0,5inch, 30 gauge needle at an oblique angle to a depth of 10 mm. Control group: Sham acupuncture (n = 23), single non‐acupuncture point on the chest (not defined exact), needling technic as "real" acupuncture. Treatment duration: 1 session of 20 min. Acupuncturist: No information. TCM‐Diagnosis Done/Applied to intervention: (‐/‐) |

|

| Outcomes | Pulmonary function (30 minutes, 60 minutes and 2 weeks following treatment), quality of life (2 weeks after treatment) and rescue medication usage (average of daily use for 2 weeks post treatment). | |

| Notes | No overall significant difference between real and sham on objective outcome measures. Improvement in quality of life observed after both treatments; rescue medication use reduced after both treatments. Sham acupuncture may have had an effect on asthma symptoms. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No information was available |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Participants and outcome assessors unaware as to whether acupuncture was active or sham; point of acupuncture was different between treatment and sham |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Hig completion rate |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | No information available on the level of training of the therapist |

Christensen 1984.

| Methods | Design: parallel group Drop‐outs/withdrawals: not described Jadad score: 1‐2‐0 Duration 11 weeks (2 weeks baseline period) | |

| Participants | N = 18 (11 female, 7 male), age range 19‐48. Outpatients from Danish hospital. Diagnosis ‐ stable bronchial asthma, FEV1 < 70% predicted. At least 4 puffs daily of a beta2‐agonist required. No previous steroids, cromoglycate or acupuncture. | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture group: Standardized acupuncture formulae (n=8) with 4 points (LI‐4 bilateral, EX‐BW1 bilateral, BL‐13 bilateral, REN‐17), manual insertion with electro stimulation (using chain frequencies of 4 Hz and 100 Hz). Needles were 10 mm, 30 gauge solid stainless steel needles. Depth of insertion varied. It was aimed to reach the De qi.

Needles were stimulated at each session. Control group: Sham acupuncture (n=9) at 3 non‐acupuncture points with placebo electro acupuncture (with no impulse) bilaterally in the middle of the hand and two above the scapula. Needle insertion to a depth of 1‐3 mm. De qi was avoided. Treatment duration: 10 sessions (20 min each) during a 5 week period. Acupuncturist: No Information. TCM‐Diagnosis done/applied to intervention: (‐/‐) |

|

| Outcomes | Pulmonary function, subjective symptoms, drug use at ‐2, 0, 2, 5 and 9 weeks. IgE levels at 0, 5 and 9 weeks. | |

| Notes | All results seem to favour acupuncture but due to the small sample size definite conclusions cannot be drawn. Results for data analysis were extrapolated from figures presenting the mean and standard error of the mean. Therefore extreme caution is required when interpreting the results. A significant proportion of results presented were unsuited to entry into Revman. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Participants and therapists unaware as to which treatment was active; presentation of treatment was identical in the two groups |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Withdrawal data are not described |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | No information available on the level of training of the therapist |

Dias 1982.

| Methods | Design: parallel group Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: patients and evaluators Jadad score: 1‐2‐0 Duration: varying observation periods for different patients (2‐12 weeks) | |

| Participants | N = 20 (10 female, 10 male), age range 18‐73. Outpatients of a general hospital in Sri Lanka. Diagnosis ‐ chronic bronchial asthma. Poor response to Western drugs. All patients on 'some form of medication' (no clear in‐/exclusion criteria given), duration of symptoms 1 to 41 years | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture group: Standardized acupuncture formulae (n = 10) with 3 points REN‐22, EX‐BW1, LU‐7. Each Treatment sessions takes 30 minutes).

Laterality not stated. Control group: Sham acupuncture (n = 10) at 2 non‐specific (not indicated for asthma) acupuncture points: GB‐5, GB‐6. Laterality not stated. Treatment duration: Session(s) number vary from 2 to 8 in control and 4 to 12 in experimental group. Acupuncturist: Physician Diploma from Beijing. TCM‐Diagnosis done/applied to intervention: (‐/‐) |

|

| Outcomes | Pulmonary function, drug use, subjective assessment (before and after acupuncture treatment) | |

| Notes | Results seem to favour sham acupuncture but due to small sample size and methodological flaws definite conclusion cannot be drawn.

Problems:

(1) variable observation period for individual patients

(2) extremely heterogeneous population

(3) GB5,6 used for sham control can be indicated in some asthma patients according to traditional Chinese medicine

(4) Insufficient information on breathing exercises (type, compliance, education, length of practice etc) INSUFFICIENT REPORTING |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Sham acupuncture administered in different locations on the body to active. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Last observation carried forward |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Therapist had received training in China |

Hirsch 1994.

| Methods | Design: cross‐over (randomization not explicitly described but likely) Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: patients and evaluators Jadad score: 0‐2‐1 Duration: 5 weeks each phase, no washout | |

| Participants | N = 39 randomised (15 female, 24 male), age range 5‐17 years, 32 analysed. Outpatients of an academic teaching hospital in Germany. Diagnosis ‐ children with mild to moderately severe asthma, according to ATS (American Thorarcic Society) criteria. 28 used inhaled beta‐agonist, 4 cromoglycate. Children taking oral or inhaled steroids excluded. | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture group: Standardized laser acupuncture formula (N = 32) with 10 points (EX‐BW1, LU‐1, LU‐5, LU‐7, LI‐4, REN‐17, BL‐13, BL‐17, KID‐3, SP‐6), 20 sec per acupuncture point. Treatment with soft‐laser (50 mw output, 820 mm wave length produced by Reimer und Janssen, Herbolzheim, Germany). Control group: Sham laser acupuncture (N=32) at the same acupuncture points as experimental group, laser switched off. Treatment Duration 15 sessions, twice weekly. Acupuncturist: Therapist trained by a German acupuncture association. TCM‐Diagnosis done/applied to intervention: (‐/‐) |

|

| Outcomes | Peak flow, subjective symptoms and drug use recorded daily by the patient. Spiromety and provocation test before and after each treatment phase. | |

| Notes | Overall no significant differences between the groups. Insufficient data presentation. Assertions that significant improvement was seen in placebo group unsupported by data reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | No information provided; randomisation not explicitly described, but likely |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Acupuncture administered at the same site as sham |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not clear if data from participants who withdrew included in data analysis |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Therapist trained by national association in Germany |

Joos 2000.

| Methods | Design: parallel group Blinding: patients only Drop‐outs/withdrawals: 1 in each group Jadad score: 1‐0‐1 Duration: 4 weeks baseline, 4 weeks treatment and 12 weeks follow‐up. | |

| Participants | N = 38 (27 female, 11 male), age range 16‐65, outpatients, recruited by advertisements, treated at the university department for anesthesiology in Heidelberg. Diagnosis mild to moderately severe allergic asthma (mean FEV1 73% of expected value). 31 patients on beta‐agonists, 20 on inhaled steroids, 11 on theophylline, duration of asthma 1‐20 years | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture group: Semi‐standardized acupuncture (n=19)with 4 basic points bilateral (BL‐13, REN‐17, LI‐4, LU 7) and up to 4 additional flexible points bilateral based on TCM diagnosis.

Depth of insertion varied from 0,3 to 30 mm. It was aimed to reach the De qi.

Needles were stimulated at each session. Control group: Sham acupuncture (n=17) at 4 non‐specific bilateral (not indicated for asthma) acupuncture points (GB‐8, GB‐34, SJ‐3, SJ‐7) and up to 4 additional flexible bilateral non‐specific acupuncture points. Treatment duration: 12 sessions (each 30 min.) in 4‐5 weeks. Acupuncturist: Acupuncturist quality: 6 medical students trained and supervised by an experienced Chinese acupuncturist. TCM‐Diagnosis done/applied to intervention: (+/+) |

|

| Outcomes | Pulmonary function, drug use, subjective assessment, immunologic parameters | |

| Notes | No significant changes in lung function, significant reduction of drug use in both groups (more in correct acupuncture group). Subjective patient assessment of improvement: 15/20 in correct acupuncture group vs. 8/18 control group. Comment: rigorous study, part of 2 theses (one focusing on immunological aspects and one ‐ only available as thesis ‐ focusing on clinical aspects) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Numbered envelopes |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Only participants were unaware as to treatment group assignment |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Low attrition rate |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Treatment given under supervision of trained specialist |

Malmström 2002.

| Methods | Design: parallel group Drop‐outs/withdrawals: 3 drop‐outs in treatment group Jadad score: 2‐0‐1 Duration: Run‐in up to 12 weeks, 15 weeks treatment, followed‐up 2 weeks after final treatment. | |

| Participants | N = 27 (15 female, 12 male), age range 33‐48, primary care, assumed treatment in primary care setting. Diagnosis of mild asthma as defined by history of wheezing attacks, variable airways constriction and bronchial response to IHCA. Excluded if > 800 micrograms per day of ICS, no OCS, recent use of complementary medicine (in last 3 months), URTI in 3 weeks before any test day. Patients had FEV1 (% pred.) of 83‐101 and R5 (kPa/l/s) 0.39‐0.60. | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture group: Individualised acupuncture from LU5, LU6, LU7, PC6, CV17, BL13, GV20, ST36, ST40, KI3 (n = 13). Number of needles gradually increased from 5 to 16. De qi sought twice per session. Needles 0.30‐0.32mm. Control group: mock TENS on upper chest. Same frequency and duration as controls. Treatment duration: 30 min sessions: 2/week for 5 weeks then 1/week for 10 weeks. Acupuncturist quality: one experienced nurse. TCM‐Diagnosis done/applied to intervention: (+/‐) |

|

| Outcomes | Published: pulmonary function (induced attack) Unpublished: pulmonary function (at set points) and drug use. | |

| Notes | Study included as one of the authors provided relevant data. No significant effect of treatment reported in bronchial responsiveness to induced attack. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Third party determined order allocation |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Acupuncture and sham treatment were not identical |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Experienced nurse administered treatment |

Medici 2002.

| Methods | Design: parallel group Drop‐outs/withdrawals: 1 in treatment group and 1 in sham group. Jadad score: 1‐1‐1 Duration: 8 weeks treatment., 8 week break, 8 weeks treatment, then follow‐up at 40 weeks. | |

| Participants | N = 66 (32 female, 34 male) with 23 in acupuncture group, 23 in sham acupuncture group and 20 in no treatment control). Mean age in acupuncture group 39.3+/‐11.4; sham group 38.4+/‐11.8; no treatment group 40.6+/‐13.5. Mean and range of nocturnal attacks per week in acupuncture group/sham group/no treatment control were 1.2(0‐6) / 2.1(0‐11) / 2.0(0‐8) and for diurnal attacks per week 4.1(0‐14) / 5.5(0‐38) / 2.1(0‐12). Mean and SD FEV1%predicted in acupuncture group/sham group/no treatment control were 91.1(+/‐17.2) / 87.0(+/‐16.1) / 85.7(+/‐18.4). Median and range of eosinophils in blood (cells*10E6/L) in acupuncture group/sham group/no treatment control were 365 (120‐1390) / 383 (50‐950) / 405 (105‐1075) and in sputum (%) were 21.6 (2.0‐76.1) / 15.3(3.6‐65.6) / 18.7(1.4‐60.3). Source of patients not reported. Diagnosis according to GINA guidelines, mild‐moderate asthma. Inclusion criteria: this asthma severity < 10 years; daily use of asthma drugs; excess type asthma according to TCM diagnosis; PEF > 60% predicted; eosinophils present in induced sputum>= 5%. Exclusion criteria: acupuncture treatment in proceeding 5 months; immunotherapy in last year; oral steroids at any time>=8 weeks in a year; high dose inhaled steroids > 1000µg BDP or > 800µg BUD; blood‐clotting disorder; >= 10 cigarettes/day; poor compliance. | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture group: Standardized acupuncture formula (n=23) with 11 points in total, chosen for

antiasthmatic effect

(DU‐14, EX‐BW1, BL‐13, KID‐3, LU‐10, SP‐6),

anti‐inflammatory effect

(LI‐4, LI‐11, DU‐14, St‐36),

and anti‐allergic as well as anti‐histaminic effect

(St‐36, LIV‐13, P‐6).

Using 1,5 inch, 30 gauge stainless steel needles.

Insertion depth 13‐40 mm at angle of 45‐90 degrees. Manually manipulated 30 times every 5 min for each session.

Laterality not stated. Control group: Sham acupuncture (n = 23) at 11 non‐acupuncture points close to real acupuncture points (not defined exact). Same needles, depth of maximal 10 mm at an angle of 10 degrees, same manipulation. Laterality not stated. Non treatment control group (n = 20). Treatment duration: 16 treatments (each 20 min) altogether. Twice weekly for 4 weeks, followed by 8 weeks without treatment and then ongoing twice weekly for 4 weeks. Acupuncturist: Well trained, experienced physician. TCM‐Diagnosis done/applied to intervention: (+/‐) Patients had to have symptoms of excess (Shi)‐type asthma. |

|

| Outcomes | Pulmonary function, subjective symptoms, drug use, immunologic parameters. | |

| Notes | Significant results in favour of acupuncture in PEF variability; by 10 months the differences between the groups had disappeared. Asthma attacks decreased slightly in all three groups (not significant between groups). Use of inhaled beta‐agonists not statistically significant between all three groups. Quality of life not effected by real or placebo acupuncture. Eosiniphils: statistical results observed sporadically. No serious adverse events reported, no reporting on non‐serious adverse events. Sham acupuncture may have effected asthma symptoms. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Therapist was aware as to the treatment given |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Low attrition rate |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | Experienced, qualified therapist |

Mitchell 1989.

| Methods | Design: parallel group Drop‐outs/withdrawals: not given. Jadad score: 1‐0‐0 Duration: 38 weeks (plus 4 weeks baseline). | |

| Participants | N = 31, 29 analysed (17 female, 12 male). Age range 15‐43. Outpatients of a hospital in New Zealand. Diagnosis ‐ chronic asthma;> 20% variation in PEFR on >7/14 days. No oral steroids, but low dose aerosol steroids. | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture group: Standardized acupuncture formula (n = 16) with 4 points bilateral (BL‐13, REN‐17, EX‐17, LIV‐3). Manual stimulation were allowed.

De qi being observed in deep tissues at each point. Control group: Sham acupuncture (n = 13) at 3 non‐specific bilateral (not indicated for asthma) acupuncture points (SP‐8, KID‐9, GB 37). Manual stimulation were allowed. De qi being observed in deep tissues at each point. Treatment duration: 8 sessions (each 15 min) in 12 weeks Once per week for the fist month, then once per fortnight. Acupuncturist: No information TCM‐Diagnosis done/applied to intervention: (‐/‐) |

|

| Outcomes | Pulmonary function, drug use and subjective symptoms. | |

| Notes | Insufficient data presented. No significant differences between groups reported. Both showed significant improvements in lung function and symptom scores and decline in medication use. Relevant loss to follow up. Sham points may have had an effect on asthma symptoms. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Acupuncture given in different locations |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | No information available |

Najafizadeh 2006.

| Methods | Design: Parallel group Drop‐outs/withdrawals: Not stated Jadad score: 1‐1‐1 Study schedule: 2 years |

|

| Participants | N = 26. Age not specified. Participants described as suffering from asthma. | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture group: Electro‐acupuncture (5 Hz, stimulation intensity not in excess of tolerability) in addition to their usual asthma medications Control group: Sham electro‐acupuncture, not described. Usual medication given as background therapy. 10 sessions over one month; follow‐up over 2 years. |

|

| Outcomes | FEV1, rescue medication use, symptoms, exacerbations | |

| Notes | Conference abstract | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | No information available |

Shapira 2002.

| Methods | Design: cross‐over Drop‐outs/withdrawals: 3 dropouts Jadad score: 1‐0‐1 Study schedule: 1 week treatment, three week washout/follow‐up, then crossed over, three week follow‐up. | |

| Participants | N = 23 (gender not given), age range 18‐58 (unpublished). Outpatient clinic in Israel. Diagnosis ‐ moderate persistent asthma. Over 18 years, beta‐2 agonists if needed, FEV1 70‐85% predicted, >= 12% improvement of FEV1 after beta‐agonists. Excluded if treated in emergency because of asthma within month prior to study or hospitalized within 3 months prior. FEV1 was 75%+‐4% before acupuncture, 70%+‐3% before sham. | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture group: Individualized acupuncture (n = 20).

Sessions 1 and 4 were designed to treat acute attacks of asthma, while sessions 2 and 3 were designed to treat the root of asthma, as diagnosed by TCM and were personalized for each patient.

Sterile, single‐use acupuncture needles were used. Depth and angle of needle insertion varies on the selected point. De qi was archived in all points.

The needles were manipulated once or twice in each session. Control group: Sham acupuncture (n = 20) was performed at non‐acupuncture points on the back, shoulders and extremities (not defined exact) at an angle of 10 to 30 degrees, insertion depth on the subcutaneous tissue. Treatment duration: 4 sessions (each 20‐30 min) in 2 weeks. Acupuncturist: Performed by a certified and experienced acupuncture therapist. TCM‐Diagnosis done/applied to intervention: (+/+) |

|

| Outcomes | Pulmonary function, drug use and subjective symptoms. | |

| Notes | No significant change in lung functions, bronchial hyperreactivity or patient symptoms. Data from a number of patients lacking for various outcomes. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Acupuncture and sham acupuncture given in different locations |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Low attrition rate |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Qualified therapist |

Tandon 1991.

| Methods | Design: cross‐over Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: patients and evaluators Drop‐outs/withdrawals: not given Jadad score: 1‐0‐0 Study schedule: 3 weeks baseline, 5 weeks treatment 1, 3 weeks washout, 5 weeks treatment 2. | |

| Participants | N = 15, (6 female, 9 male). Age range 19‐57 years. Diagnosis ‐ Chronic stable asthma according to American Thoracic Society (ATS) criteria. All on inhaled steroids, all except 1 on theophylline. No oral steroids or cromoglycate. | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture group: Standardized laser acupuncture formulae (n = 15) with 8 body points (SP‐6, ST‐36, LIV‐9, LI‐11, REN‐17, REN‐22, BL‐13, EX‐BW1) and 3 ear points ( asthma, lung, internal secretions).

Treatment with helium‐neon‐laser had a wavelength of 632,8 nm and emitted beam of 5.6 mw at the tip of the probe.

Power density delivered at each point was 0.56 J/cm2 per second. Control group: Sham laser acupuncture (n = 15) at 7 non‐specific (not indicated for asthma) acupuncture points (GB‐34, LIV‐8, LIV‐14, SI‐3, SI‐6, BL‐18, BL‐25) and 2 ear points (uterus and bladder). Treatment duration: 10 sessions (each 20 seconds for body and 10 sec for ear acupuncture) in 5 weeks. Acupuncturist: Physician, training not stated. TCM‐Diagnosis done/applied to intervention: (‐/‐) |

|

| Outcomes | Pulmonary function, drug use, symptom score and treatment preference. | |

| Notes | Crossover design and data presentation unsuited for meta‐analysis. No significant effects between or within groups. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Active and sham acupuncture not administered at identical sites |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Not enough information as to level of training |

Tashkin 1985.

| Methods | Design: cross‐over Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: patients and evaluators Drop‐outs/withdrawals: not given Jadad score: 1‐0‐0 Study schedule: 4 weeks baseline, 4 weeks treatment 1, 3 weeks wash‐out, 4 weeks treatment 2, 3 weeks follow‐up | |

| Participants | N = 25 (15 female, 10 male) Age range 8 ‐ 70. Diagnosis ‐ Moderate to severe stable chronic asthma. FEV1< 60% predicted. Most on oral and inhaled beta‐agonists and theophylline. Most also on oral steroids. 11 on cromoglycate. | |

| Interventions | Acupuncture group: Standardized acupuncture formula (n = 25) with 6 points bilateral (LI‐4, DU‐14, ST‐36, LU‐7, Ex‐W1, Ex Waitingchuan (???)). Acupuncture needles were 1,5 inch, 30 gauge, solid stainless needles manufactured in China that were sterilized by autoclave before use. Depth of insertion varied ranging from 4 to 20mm. Needles manipulation every 3 to 4 min. Control group: Sham acupuncture (n = 25) was performed at non‐acupuncture points. Needles manipulation every 3 to 4 min. Treatment duration: 8 sessions (each 15 min) within 4 weeks. Acupuncturist: Well‐ trained experienced practitioner. TCM‐Diagnosis done/applied to intervention: (‐/‐) |

|

| Outcomes | Pulmonary function, subjective measurements, drug use, number of attacks. | |

| Notes | Data presentation and crossover design unsuited for meta‐analysis. No significant differences were found between or within groups. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No information available |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Active and sham acupuncture not presented identically |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | Qualified therapist |

Jadad scores reflect the points awarded for the three component domains in the order of: randomisation (0,1 or 2), blinding (0, 1 or 2) and withdrawals (0 or 1).

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Ailioaie 1999 | No inactive control group |

| Aillioaie 2000 | Not acupuncture |

| Berger 1975 | Non‐randomised controlled trial. |

| Choudhury 1989 | Before and after study of acupuncture in extrinsic asthma |

| Chow 1983 | RCT on induced asthma attacks (not covered by this review) |

| Eber 2001 | RCT on exercise‐induced asthma (not covered by this review) |

| Fung 1986 | RCT on induced asthma attacks (not covered by this review) |

| Gruber 2002 | RCT on induced asthma attacks (not covered by this review) |

| Jobst 1986 | RCT of acupuncture in COPD. |

| Karst 2002 | RCT of acupuncture in healthy participants |

| Luu 1985 | RCT of thoracic trigger points with evaluation of lung function 2hs after treatment |

| Maa 1997 | RCT of acupressure in COPD. |

| Mehl‐Madrona 2007 | No sham control group |

| Morton 1993 | RCT on induced asthma attacks (not covered by this review) |

| Sovijarvi 1977 | Not randomized, short‐term observation |

| Stockert 2007 | Addition of therapy to acupuncture not given to control group |

| Takishima 1982 | Not randomized, short term observation |

| Tandon 1989 | RCT on induced asthma (not covered by this review) |

| Tashkin 1977 | RCT on induced asthma attacks (not covered by this review) |

| Virsik 1980 | Not randomized, short time observation |

| Yu 1976 | Randomization not reported, treatment on an acute attack |

| Zhang 2006 | Methods not sufficient to determine quality |

Contributions of authors

INITIAL VERSION (1997): All authors participated in protocol development, extraction and analysis of the primary studies and writing of the manuscript.

UPDATE (MAY 2003) Rob McCarney ‐ paper selection; eligibility and quality assessment, data extraction, data entry, analysis and interpretation

Klaus Linde ‐ paper selection; eligibility and quality assessment; data extraction; data entry; analysis and interpretation

Benno Brinkhaus ‐ assessment of interventions across the studies; interpretation

Toby Lasserson ‐ quality assessment; data extraction; data entry; analysis and interpretation

Sources of support

Internal sources

Oxfordshire Health Authority Trust Fund, UK.

External sources

Donald Lane Trust, Oxford, UK.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Biernacki 1998 {published data only}

- Biernacki W, Peake MD. Acupuncture in the treatment of stable asthma. Respiratory Medicine 1998;92:1142‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Christensen 1984 {published data only}

- Christensen PA, Laursen LC, Taudorf E, Störensen SC, Weeke B. Acupuncture and bronchial asthma. Allergy 1984;39:379‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen PA, Laursen LC, Taudorf E, Störensen SC, Weeke B. Acupuncture for asthma patients. Ugeskrift for Laeger 1986;148:241‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dias 1982 {published data only}

- Dias PLR, Subramaniam S, Lionel ND. Effects of acupuncture in bronchial asthma: Preliminary communication. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 1982;75:245‐8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hirsch 1994 {published data only}

- Hirsch D, Leupold W. Placebo‐controlled study on the effect of laser acupuncture in childhood asthma [Plazebo‐kontrollierte Doppelblindstudie zur Wirkung der Laserakupunktur beim kindlichen Asthma bronchiale]. Atemwegs‐Lungenkr 1994;20(12):701‐5. [Google Scholar]

Joos 2000 {published and unpublished data}

- Joos S. Immunmodulierende Wirkung der Akupunktur als erganzende Therapie bei allergischem Asthma [Immunomodulatory effect of acupuncture as an alternative therapy in allergic asthma]. Erfahrungsheilkunde 1996;45:10‐4. [Google Scholar]

- Joos S. Immunological effects of acupuncture as a suuplementary therapy for allergic asthma [Immunologische Effekte der Akupunktur als ergänzende Therapie bei allergischem Asthma bronchiale]. Thesis, University of Heidelberg 1997.

- Joos S, Schott C, Zou H, Daniel V, Martin E. Acupuncture ‐ immunological effects in the treatment of allergic asthma [Akupunktur ‐ immunologische Effekte bei der Behandlung des allergischen Asthma bronchiale]. Allergologie 1997;20(2):63‐8. [Google Scholar]

- Joos S, Schott C, Zou H, Daniel V, Martin E. Immunomodulatory effects of acupuncture in the treatment of allergic asthma: a randomized controlled study. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2000;6:519‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joos S, Schott C, Zou H, Daniel V, Martin E, Brinkhaus B. Immunomodulatory effects of acupuncture in the treatment of allergic asthma. Chinesische Medizin 1999;14(4):143‐54. [Google Scholar]

- Joos S, Schott C, Zou H. Acupuncture as an supplementary therapy in allergic bronchial asthma [Akupunktur als Erganzungstherapie bei allergischem Asthma bronchiale]. Akupunktur als Erganzungstherapie bei allergischem Asthma bronchiale 1996;19(3):153‐4. [Google Scholar]

- Schott C. Can conventional medicine be reduced through the use of needle acupuncture as a tretament option in allergic asthma? [Läßt sich die konventionelle Medikation durch ergänzende Nadelakupunktur als Therapeutikum bei allergischem Bronchialasthma einschränken?]. Thesis, University of Heidelberg 1997.

- Schott CR, Martin E. Controlled trial of acupuncture in the treatment of bronchial asthma. FACT 2001;6(1):91‐2. [Google Scholar]

Malmström 2002 {published and unpublished data}

- Malmstrom M, Ahlner J, Carlsson C, Schmekel B. No effect of chinese acupuncture on isocapnic hyperventilation with cold air in asthmatics, measured with impulse oscillometry. Acupuncture in Medicine 2002;20(2):80‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Medici 2002 {published data only}

- Grebski E, Wu J, Wuthrich B, Hinz G, Medici TC. Long‐term effects on real and sham acupuncture on lung function and eosinophilic inflammation in chronic allergic asthma: randomised, prospective study. European Respiratory Journal 1999;18(Suppl 33):124. [Google Scholar]

- Medici TC. Acupuncture and bronchial asthma [Akupunktur und Bronchial asthma]. Forsch Komplementärmed 1999;6(Suppl 1):26‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medici TC, Grebski E, Wu J, Hinz G, Wuthrich B. Acupuncture and broncial asthma: a long‐term randomized study of the effects of real versus sham acupuncture compared to controls in patients with bronchial asthma. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2002;8(6):737‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mitchell 1989 {published data only}

- Mitchell P, Wells JE. Acupuncture for chronic asthma: A controlled trial with six months follow‐up. American Journal of Acupuncture 1989;17:5‐13. [Google Scholar]

Najafizadeh 2006 {published data only}

- Najafizadeh K, Vosughian M, Rasaian N, Sohrabpour H, Deilami MD, Ghadiani M, et al. A randomized double blind placebo controlled trial on the short and long term effects of electro acupuncture on moderate to severe asthma. European Respiratory Journal 2006;28(Suppl 50):502s. [Google Scholar]

Shapira 2002 {published and unpublished data}

- Shapira MY, Berkman N, Ben‐David G, Avital A, Bardach E, Breuer R. Short‐term acupuncture therapy is of no benefit in patients with moderate persistent asthma. Chest 2002;121:1396‐400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tandon 1991 {published data only}