Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The gathered archeopathological evidence has confirmed that Schistosomiasis has been endemic in Ancient Egypt for over 500 decades. The association between Schistosoma hematobium and increase bladder cancer risk is also well acknowledged. However, over the years, there is a proved changing pattern of bladder cancer that needs to be investigated.

AIM:

We aim to discuss the truths and myths about bladder cancer and its association with Schistosomiasis in Egypt.

METHODS:

A cross-sectional, case-control study was performed to collect recent data on the topic.

RESULTS:

Of the reported cancer cases, 79.3% were transitional cell carcinoma (TCC), an additional 6% showed associated squamous features. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) constituted only 13.8% of cancer cases. Schistosomiasis was histologically confirmed in 19 cancer cases, only one was SCC. The relative frequency of TCC is increasing, while SCC is decreasing. There is no evidence that this pattern is related to smoking or environmental factors, as the incidence of lung cancer, is not proportionately increasing.

CONCLUSION:

The old concept that Schistosomiasis is associated with SCC should be revaluated as most cases are associated with TCC. Relying on the histopathology for confirmation of Schistosomiasis in our research studies appears to be non-accurate and leads to irrelevant results.

Keywords: Schistosomiasis, Bladder cancer, Molecular basis, Urothelial carcinoma, Squamous cell carcinoma, Transitional cell carcinoma

Introduction

Schistosomiasis is an ancient disease, depicted in papyri from Pharaonic Egypt, not less than 50 times, including Ebers: 28, Berlin: 12, Hearst: 9, and London: 1. The classic symptom of blood in the urine has been described in the Ebers papyrus as the āāā disease and has been mentioned in various other medical papyri that contained prescriptions against hematuria [1], [2]. Later evidence of Schistosomiasis in medieval Egypt was detected in 15 mummies from 35 to 550 AD in the Wadi Halfa near the Egypt-Sudan border [3].

Nowadays, Schistosomiasis is the second most common parasite affecting humans. In 2015, WHO reported Schistosomiasis as endemic in 78 countries; with Africa being the most affected as it has been reported in 42 African countries [4].

Ferguson (1911) had first linked S. hematobium to urinary bladder cancer in Egypt [5]. In 1994 and 2012, IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) confirmed that chronic infestation by S. hematobium is associated with cancer of the urinary bladder [6], [7]. Since then, the association between S. hematobium and cancer bladder has become well established [8], [15]. Urinary bladder cancer is the second common cancer among males (≈ 12.7%) following HCC as reported by results of the National Population-Based Cancer Registry Program in Egypt, 2014 as well as GLOBOCAN, 2018 [16], [17]. In his report, Ghoneim et al. (1997) declared that squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) constituted 59% of 1026 cystectomy specimens at the Mansoura Urology and Nephrology Centre [18].

Most of the research studies in this field have confirmed the epidemiological association between SCC of the bladder with S. hematobia. SCC was documented as prevalent in areas with high worm burdens whereas TCC was more commonly reported in areas associated with lower degrees of infestation. TCC risk was attributed to the continuous exposure to the carcinogens, e.g., N-nitroso compounds [19], [20].

However, these compounds were presumably detected in larger quantities in the urine of patients with S. hematobium than in patients without this infection [21], [22].

Nowadays, there is a growing belief that the control of Schistosomiasis in Egypt has led to a change in the type of bladder cancers with a continual decrease of SCC and subsequent increase of Urothelial tumours [22], [23]. Felix et al., (2008) reviewed the reports of 2,778 patients through 26 years and concluded that there is a decline in the rate of SCC associated with an increasing rate of TCC [24]. Other studies claimed a drop in the frequency rate of bladder cancer related to the successful control of Schistosomiasis [25], [28]. Worth mentioning, some research studies have omitted S. hematobium from epidemiology and bladder cancer prevention [29].

More research is needed to investigate this changing pattern of bladder cancer in Egypt and to find out an answer to the following questions: “Why is the rate of bladder cancer still high in Egypt in spite of the claim of Schistosomiasis control?”, “Is the S. hematobium related to SCC rather than TCC?”, “Do we have an accurate reporting of the actual Schistosomiasis burden in Egypt?”, and “What are the possible national measures that could be implemented to control such preventable cancer?” [30], [31].

We aim to investigate and to refute the beliefs about urinary bladder cancer in Egypt. There are questions to be answered and claims to be judged.

Material and Methods

Case Selection & histopathological study

Design: In this case-control, observational study, 116 consecutive samples from bladder masses-from the authors’ practice in six-month duration-were compiled and reviewed. The samples included neoplastic and non-neoplastic cases. It was noted that five of which were referred twice (i.e. 111 patients). A detailed evaluation of the available data was presented and analysed. Data including age, sex, type of specimen, type of lesion, grade and stage of carcinoma and associated S. hematobium infestation was examined, reported, evaluated and discussed.

Statistical analysis

Data were coded and entered using the statistical package SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 25. Data were summarised using mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum in quantitative data and using frequency/count and relative frequency/percentage for categorical data. Chi-square (χ2) test was performed for comparing categorical data. The exact test was used when the frequency is less than 5. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant [32].

Results

The results are summarised in the Tables (1, 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Frequency and percentage table of bladder cancer cases

| Count | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Total | 116 | 100.0% |

| Group | Cancer either by biopsy or cystectomy | 87 | 75.0% |

| sex | Male | 77 | 85.5% |

| Female | 10 | 14.5% | |

| Specimen | TURBT | 98 | 84.5% |

| Cystectomy | 18 | 15.5% | |

| Positive | 28 | 24.1% | |

| Schistosomiasis | Features suggestive | 19 | 16.4% |

| Not documented | 69 | 59.5% | |

| I | 11 | 12.6% | |

| I-II | 14 | 16.1% | |

| II | 24 | 27.6% | |

| II-III | 15 | 17.2% | |

| III | 23 | 26.4% | |

| Signet ring carcinoma | 1 | 1% | |

| Grade | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | 2% |

| Papillary TCC | 28 | 32% | |

| Recurrent TCC/adenocarcinoma | 1 | 1% | |

| Recurrent TCC | 2 | 2% | |

| TCC | 36 | 41.4% | |

| TCC/SCC | 5 | 5.7% | |

| SCC | 12 | 13.8% | |

| Ta | 21 | 24.1% | |

| T1 | 17 | 19.5% | |

| T2a | 4 | 4.6% | |

| T2b | 32 | 36.8% | |

| T3a | 1 | 1.1% | |

| Stage | T3b | 7 | 8.0% |

| T4a | 2 | 2.3% | |

| T4 (enteric invasion) | 1 | 1.1% | |

| T4 (prostatic invasion) | 1 | 1.1% | |

| Tx | 1 | 1.1% | |

| N0 | 13 | 14.9% | |

| N2 | 3 | 3.4% | |

| LN | |||

| No nodes | 71 | 81.6% |

Table 2.

Frequency and percentage table of cystitis

| Count | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-specific cystitis | 9 | 31% | |

| With Suspected But Not Definitely Diagnosed Schistosomiasis | 11 | 38% | |

| Schisosomial cystitis cases | 9 | 31% | |

| Total | Total | 29 | 100.0% |

| Sex | M | 22 | 74.9% |

| F | 7 | 24.1% | |

| Active Schistosomiasis | 5 | 4.5% | |

| Old Schistosomiasis | 4 | 1.8% | |

| Giant cell cystitis | 1 | 0.9% | |

| Non-specific cystitis | 2 | 3.6% | |

| Type | |||

| Proliferative cystitis | 5 | 4.5% | |

| Proliferative cystitis/dysplsia | 1 | 0.9% | |

| Proliferative cystitis/squamous metaplasia | 3 | 2.7% | |

| ulcer | 3 | 2.7% | |

Table 3.

Differential Frequency and percentage of bladder cancer types

| Cancer Type | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma | SCC | TCC | TCC/SCC | P value | ||||||

| Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | |||

| Schistosomiasis | Positive | 1 | 33.3% | 3 | 25.0% | 12 | 17.9% | 3 | 60.0% | 0.149 |

| Features | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 10.4% | 1 | 20.0% | ||

| Negative | 2 | 66.7% | 9 | 75.0% | 48 | 71.6% | 1 | 20.0% | ||

| Total | 3 | 100.00% | 12 | 100.00% | 67 | 100.00% | 5 | 100.00% | ||

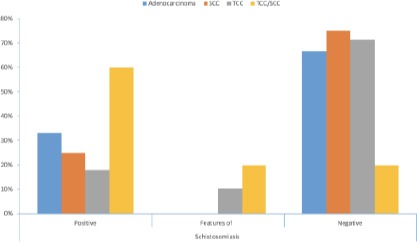

Figure 1.

Relation between cancer type and Schistosoma infestation (Positive for S. Hematobium; Features of Schistosomiasis = Proliferative cystitis with Brunn’s nests, cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis; Negative = no identifiable ova or proliferative lesions)

Out of the 116 samples, 93 belonged to males (81%). Eighty-seven (75%) specimens were diagnosed as cancer bladder.

Twenty-nine had inflammatory mass lesions; one of which presented by a few months later by cancer. A wide age range (20-78 years)-mean 61.56-was noted in the neoplastic lesions, and (13-76 years)-mean 47-in inflammatory lesions (Table 2).

Regarding the cancer cases, 77 samples from 74 patients (85.5%) were males, and only 10 were females. Sixty-nine samples were TURBT while 18 were radical cystectomy specimens. A total of 69 cases (79.3%) were transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). Thirty-eight cases (43.7%) were invasive TCC (two of which were recurrent), 22 cases (25%) were superficial non-invasive low- grade papillary TCC, 6 cases (7%) were invasive papillary TCC, Five cases (6%) showed associated squamous features, and only one case (< 1%) showed associated adenocarcinoma features. Only 12 cases (13.8%) were pure squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Three cases (3.5%) were pure adenocarcinoma. No neuroendocrine features were reported in any lesion [33] (Table 1).

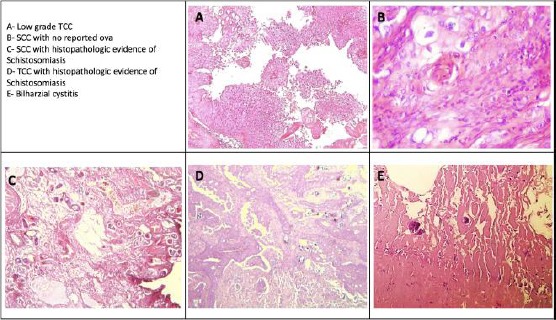

Worth mentioning, one case-diagnosed as superficial non-invasive low-grade papillary TCC- presented 9 months later by invasive squamous cell carcinoma grade 2 associated with positive lamina propria invasion (Figure 2A and 2B).

Figure 2.

Microscopic picture of frequently reported bladder cancers

Regarding the stage, 21 cases were Ta, 17 cases were T1, 36 cases were T2, and 8 cases were T3, and 4 cases were T4. As regards nodal status, 13 cases were N0, and 3 cases were N2.

Schistosomiasis was histologically confirmed in 19 cases (Figure 2C and 2D), only three were SCC. Features suggestive for schistosomiasis were noted in 8 cases (proliferative cystitis with/without squamous metaplasia). Hematobia ova were not detected histologically in 60 cases (Table 3).

In inflammatory mass lesions, Schistosoma ova were histologically detected in only 9 cases (Figure 2E].

Discussion

Although the sample size is small, it reflects the current condition in Egypt.

The male to female prevalence worldwide is reported to be 3: 1 [17], [31]. The ratio is slightly higher in our reports, as males represent 85.5% of the reported cancer samples. Several molecular studies suggested a role of loss of Y-chromosome [34], [35].

The mean age for cancer is reported to be 61.56, following the inflammatory lesions by about 15 years-mean age being 47 years. This suggests a chronic inflammatory process preceding the cancer.

As regards the type of cancer and its relation to Schistosomiasis the following issues are to be discussed:

Myth 1: Schistosomiasis is associated with SCC

SCC is thought to be associated with S. Hematobum and is very rare in individuals/areas free of the parasite. The reported SCC incidence rate is 10: 1,000 in infected adults, but only in 0-3: 1,000 schistosome-free individuals [20], [36].

Truth: On applying similar research methodology that depends on the histologic confirmation of the parasitic infestation; S. Hematobium was histologically confirmed in only three SCC cases, representing a non-significant correlation.

Only 3 cases of pure SCC carcinoma showed S. Hematobium ova, nine showed no histologic proof of infestation. Cases of mixed TCC/SCC showed ova in three out of five. One case showed associated Brunn’s nests and one did not even show any associated proliferative lesion.

The association of Schistosoma associated SCC as compared to other types of bladder cancer represents a non-significant relation (p-value is 0.355). The correlation is also non-significant in comparing SCC with TCC (p-value is 0.8).

We do not deny the construct that SCC is strongly associated with S. Hematobium. However, we predict that nowadays, Schistosomiasis is more consistently related to TCC.

In our records, a case that was diagnosed as bilharzial cystitis has presented nine months later by muscle-invasive high-grade TCC (Figure 2D and 2E).

We conjointly believe that in all the reported research studies; including our present study; we have a major flaw within the scientific methodology. That is relying on the histopathologic assessment for the diagnosis of Schistosomiasis [22].

In our records, a case with submitted recurrent lesion showed S. Hematobia ova in the latter specimen that was not detected within the former biopsy.

We need more accurate laboratory methods of confirmation of the parasitic infestation. However, the firm belief of the oncologists that the lines of management are similar whether there is associated infestation or not hinders conducting such laboratory investigations and also limits their use in the research field [22].

Myth 2: SCC is prevalent in rural Africa as the parasite is prevalent

The epidemiological association between SCC of the bladder with S. Hematobia is based both on case-control studies and on the correlation of bladder cancer incidence with the prevalence of S. Hematobium infection within the diverse geographic areas [10], [32].

Truth: In Egypt, bladder cancer is the second common cancer in males. However, the predominating type is TCC (86%), not SCC. 86% of our collected cases were TCC, 18% showed histopathologic evidence of S. Hematobium infestation. This is also confirmed by studies done on larger cohorts [20], [23].

Myth 3: Schistosomiasis is associated with poorly differentiated SCC

Schistosoma-associated cancer usually present as poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma [11], [37].

Truth: In our study, only two of the twelve collected cases were poorly differentiated; the others were grades I and II. Cases of TCC/SCC were high-grade tumours.

In our records, one case with superficial non-invasive papillary TCC presented eight months later by muscle-invasive SCC, grade 2. Schistosomiasis was not detected in either lesion.

Myth 4: Schistosomiasis associated bladder SCC presents relatively early

Schistosomiasis -associated bladder SCC appears relatively early, especially due to re-infection. It often presents at the mid-decades of life. TCC usually presents in the latter decades of life [37].

Truth: According to our collected data, the mean age for SCC presentation was 60.58 (36-78 years), and for TCC was 61.5 (20-78 years). The mean age of presentation is nearly similar.

Myth 5: Successful control of Schistosomiasis has led to changing the pattern of bladder cancer

The decline in the incidence of SCC in Egypt is attributed to the successful control of Schistosomiasis [28]. Thus the pattern is changing in Egypt approaching that of the regions not endemic for urogenital schistosomiasis is TCC [11], [37].

Truth: In our reported cases the ova were histologically detected in 12 cases of the TCC and only 3 of the SCC. The correlation is insignificant for both. However, it is more associated with TCC. Twenty-two cases (25%) were superficial non-invasive low-grade papillary TCC, all of which showed no S. hematobium ova in tissue sections.

Here we should confess that the histological evaluation of Schistosomial infestation is not precise. Unfortunately, most of the research work in this field does not depend on the modern techniques for evaluation of Schistosomal infestation and depends on the histopathologic findings, which proved to be inaccurate.

For accurate assessment of the condition, we should depend on urine examination and/or serological methods [36].

Myth 6: Increased smoking and exposure to pesticides has led to an increased incidence of TCC

It is claimed that smoking, including passive smoking as well as exposure to environmental hazards, has contributed to the increased incidence of TCC [28]. Recent research studies suggest that tobacco smoking increases the risk of bladder carcinoma in Egyptian men [39], [40].

Truth: This postulation is not supported by the results of the national registry, as there is no associated increased incidence of lung cancer, especially in males. According to the registry in 2014, the bladder is the second common cancer in men while the lung is the fourth malignancy, after liver, bladder, and Hodgkin lymphoma, representing only (8.2%) of the reported malignancies. If smoking is a major risk factor for the increasing TCC in Egypt, a proportionate increase in lung cancer should have been expected. Moreover, the Schistosomiasis in bladder cancer patients should be confirmed or excluded by using the hemagglutinin and/or urine tests before postulating that the increased rate of TCC is attributed to smoking.

More research is needed in the field of the molecular basis of bladder cancer in Egypt as the available knowledge is deficient in this field [41], [42].

Myth 7: Treatment strategies have similar end-results regardless of etiologic factor(s) implicated in bladder carcinogenesis [22]

There is a solid belief that the management of Schistosoma-associated bladder cancer should follow the recommendations for the Schistosoma non-associated urothelial cancers. This belief is one of the main reasons for intentionally or non-intentionally omitting the reporting of associated infestation in our cancer cases. Subsequently, no treatment strategy is directed towards eliminating the infestation in cancer patients.

Truth: It is well known for decades that nodal metastasis is rare in our bladder cancer patients; even with the advanced stage at presentation. In our study, only three cases were reported with nodal metastasis (none has shown associated ova). This was previously attributed to the high frequency of low-grade tumours and/or the limiting effect of local Schistosomal tissue reactions [43].

However, we need more molecular studies to validate these beliefs, as we have an increased rate of higher grade tumours (> 50% of our reported cases were high-grade TCC), with no associated increased rate of nodal metastasis. Such studies will surely have a great impact on treatment strategies to avoid overtreatment.

Limitations of previous research studies in Egypt

- Felix et al. in their records of cancer bladder in the period from 1980 through 2005 at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) from 1980 through 2005 admitted that reporting of Schistosomiasis was missing in some of the records due to the assumption that it would not affect the course of treatment [25].

- Bladder cancers were classified as Schistosoma associated and non-Schistosoma associated based on the history of Schistosomal infection, ever receiving anti-Schistosomal therapy, presence of periportal fibrosis on ultrasound liver examination, or presence of Schistosome ova in the tumour specimen [21], [22], [23]. None of these is considered to be accurate in confirmation or ruling out of the infestation.

- No antecedently published work has investigated the possibility of underestimation of Schistosomal infestation.

- The studies on the molecular basis of bladder cancer in Egypt and its changing patterns are limited [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50].

- We need more research work on non-invasive techniques for the early detection of the parasitic infestation and early cancer detection of susceptible individuals [51].

- Adoptive immunotherapy offers promise in cancer treatment. Further research is necessary to bring immunotherapy further to the forefront of treating bladder cancer [53].

We can conclude that:

Bladder cancer is the 2nd common cancer among males in Egypt, the 6th worldwide. The 4th cumulatively in Egypt and the 10th globally.

Bladder cancer remains a major health problem in Egypt in spite of the evidence of Schistosomiasis control.

There is evidence that the types and patterns of bladder cancer are changing in Egypt.

The increased rate of TCC could not be attributed to smoking only. As there is no associated increase in lung cancers among Egyptian men.

Preventing Schistosomiasis (successful eradication programs) is the best treatment and least expensive way of fighting bladder cancer in endemic areas.

Unfortunately, most of the research work in the field does not depend on sensitive techniques for the detection of Schistosoma infestation and depends on the histopathologic findings which have proved to be inaccurate. The worse is that the recently published articles declare that, upon applying the same treatment protocol and management care, stage by stage comparison of the treatment end-results was found to be similar in bladder cancer patients with a different aetiology.

More research study on the molecular basis of Schistosomiasis-TCC associated cancer in urine, serology and mouse bladder wall injection model is needed to understand the changing pattern of bladder cancer.

Leading policymakers should be acquainted with this data to be able to adopt a national screening program for Schistosomiasis, similar to the successful model of HCV control. The implementation of evidence-based measures in bladder cancer control may decrease the burden of this cancer in Egypt.

The availability of a large number of patients will allow the review of old concepts and better evaluation of the present condition.

Footnotes

Funding: This research did not receive any financial support

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist

References

- 1.Ebeid NI. Egyptian Medicine in the Days of the Pharaohs. General Egyptian Book Organization. 1999:218–224. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Othman AA, Soliman RH. Schistosomiasis in Egypt: A never-ending story? Acta tropica. 2015;148:179–90. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.04.016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.04.016 PMid:25959770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An interview with Dr Magda Azab. Trop Parasitol .v.3 (2);Jul-Dec 2013PMC3889100 Trop Parasitol. 2013;3(2):170–174. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.122153. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5070.122153 PMid:24471008 PMCid:PMC3889100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inobaya MT, Olveda RM, Chau TN, Olveda DU, Ross AG. Prevention and control of schistosomiasis:a current perspective. Research and reports in tropical medicine. 2014;2014(5):65–75. doi: 10.2147/RRTM.S44274. https://doi.org/10.2147/RRTM.S44274 PMid:25400499 PMCid:PMC4231879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferguson AR. Associated bilharziasis and primary malignant disease of the urinary bladder with observations on a series of forty cases. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1911;16:76–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1700160107. [Google Scholar]

- 6.IARC. Monograph on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans:schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. WHO:International Agency for Research on Cancer. 1994;61:9–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biological agents. Volume 100 B. A review of human carcinogens. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100(Pt B):1–441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palumbo E. Association between schistosomiasis and cancer:A review. Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice. 2007;15(3):145–148. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.idc.0000269904.90155.ce. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mostafa MH, Helmi S, Badawi AF, Tricker AR, Spiegelhalder B, Preussmann R. Nitrate, nitrite and volatile N-nitroso compounds in the urine of Schistosoma Hematobum and Schistosoma mansoni infected patients. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15(4):619–25. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.4.619. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/15.4.619 PMid:8149471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badawi A, Mostafa M, Probert A, O'Connor P. Role of schistosomiasis in human bladder cancer:Evidence of association, aetiological factors, and basic mechanisms of carcinogenesis. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 1995;4:45–59. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199502000-00004. https://doi.org/10.1097/00008469-199502000-00004 PMid:7728097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mostafa MH, Sheweita SA, O'Connor PJ. Relationship between schistosomiasis and bladder cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(1):97–111. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.97. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.12.1.97 PMid:9880476 PMCid:PMC88908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abol-Enein H. Infection: Is it a cause of bladder cancer? Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 2008:79–84. doi: 10.1080/03008880802325309. https://doi.org/10.1080/03008880802325309 PMid:18815920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Martel C, Franceschi S. Infections and cancer: Established associations and new hypotheses. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2009;70(3):83–194. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.07.021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.07.021 PMid:18805702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Botelho M, Machado J, da Costa J. Schistosoma Hematobum and bladder cancer:What lies beneath? Virulence. 2010;1(2):84–7. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.2.10487. https://doi.org/10.4161/viru.1.2.10487 PMid:21178421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishida K, Hsieh MH. Understanding Urogenital Schistosomiasis-Related Bladder Cancer: An Update. Front. Med. 2018;5:223. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00223. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00223 PMid:30159314 PMCid:PMC6104441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibrahim AS, Khaled HM, Mikhail NN, Baraka H, Kamel H. Cancer incidence in Egypt:results of the national population-based cancer registry program. Journal of cancer epidemiology 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/437971. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/437971 PMid:25328522 PMCid:PMC4189936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics. 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492 PMid:30207593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghoneim MA, El-Mekresh MH, El-Baz MA, El-Attar IA, Ashamallah A. Radical cystectomy for carcinoma of the bladder:Critical evaluation of the results in 1026 cases. J Urol. 1997;158:393–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64487-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marbjerg LH, Øvrehus AL, Johansen IS. Schistosomiasis-induced squamous cell bladder carcinoma in an HIV-infected patient. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2015;40:113–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.10.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2015.10.004 PMid:26474894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Botelho M, Alves H, Richter J. Halting Schistosoma Hematobum - associated bladder cancer. Int J Cancer Manag. 2017;10(9):e9430. doi: 10.5812/ijcm.9430. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijcm.9430 PMCid:PMC5771257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yosry A. Schistosomiasis and neoplasia. Contributions to microbiology. 2006;13:81–100. doi: 10.1159/000092967. https://doi.org/10.1159/000092967 PMid:16627960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohamed S. Zaghloul. Bladder cancer and schistosomiasis. Journal of the Egyptian National Cancer Institute. 2012;24:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jnci.2012.08.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnci.2012.08.002 PMid:23159285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaghloul MS, Nouh A, Moneer M, El-Baradie M, Nazmy M, Younis A. Time-trend in epidemiological and pathological features of schistosoma-associated bladder cancer. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2008;20(2):168–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaghloul MS, Gouda I. Bladder cancer and schistosomiasis:Is there a difference for the association. In: Canda AE, editor. Bladder cancer- from basic science to robotic surgery. Croatia: In Tech open publisher, Rajeko; 2012. pp. 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felix AS, Soliman AS, Khaled H, Zaghloul MS, Banerjee M, El-Baradie M, El-Kalawy M, Abd-Elsayed AA, Ismail K, Hablas A, Seifeldin IA. The changing patterns of bladder cancer in Egypt over the past 26 years. Cancer Causes & Control. 2008;19(4):421–9. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9104-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-007-9104-7 PMid:18188671 PMCid:PMC4274945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salem S, Mitchell RE, El-Alim El-Dorey A, Smith JA, Barocas DA. Successful control of schistosomiasis and the changing epidemiology of bladder cancer in Egypt. BJU Int. 2011;107(2):206–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09622.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09622.x PMid:21208365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salem H, Mahfouz S. Changing Patterns (Age, Incidence, and Pathologic Types) of Schistosoma-associated Bladder Cancer in Egypt in the Past Decade. Urology. 2012;79(2):379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.08.072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2011.08.072 PMid:22112287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barakat RMR. Epidemiology of Schistosomiasis in Egypt:Travel through Time:Review. J Adv Res. 2013;4(5):425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2012.07.003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2012.07.003 PMid:25685449 PMCid:PMC4293883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Długosz A, Królik E. Bladder cancer prevention. Nowotwory. Journal of Oncology. 2017;67(4):251–6. https://doi.org/10.5603/NJO.2017.0040. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daniel A, Bhatt A. Schistosomiasis and Bladder Cancer in Egypt:A Historical Analysis. Journal of Global Oncolog. 2016 https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.2016.004580. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khaled H. Schistosomiasis and Cancer in Egypt:Review. J Adv Res. 2013;4(5):461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2013.06.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2013.06.007 PMid:25685453 PMCid:PMC4293882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan YH. Biostatistics 103:Qualitative Data -Tests of Independence. Singapore Med J. 2003;44(10):498–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi S, Chen S, Zhou X, Huang S. Clinicopathologic observation of 6 cases with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Clinical Oncology and Cancer Research. 2009;6(4):277–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11805-009-0277-6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McBeth L, Grabnar M, Selman S, Hinds TD. Involvement of the Androgen and Glucocorticoid Receptors in Bladder Cancer. Int J Endocrinol. 2015:384860. doi: 10.1155/2015/384860. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/384860 PMid:26347776 PMCid:PMC4546983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khaled HM, Aly MS, Magrath IT. Loss of Y Chromosome in Bilharzial Bladder Cancer. Cancer Genetics and cytogenetics. 2000;117(1):32–36. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(99)00126-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4608(99)00126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeremy W Martin, a Estrella M, Carballido b, Ahmed Ahmed, a,c, Bilal Farhan A, Rahul Dutta A, Cody Smith A, Ramy F. Yearsussefa. Squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: Systematic review of clinical characteristics and therapeutic approaches. Arab J Urol. 2016;14(3):183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2016.07.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aju.2016.07.001 PMid:27547458 PMCid:PMC4983161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bedwani R, Renganathan E, El Kwhsky F, Braga C, Seif HA, Azm TA, et al. Schistosomiasis and the risk of bladder cancer in Alexandria, Egypt. Br J Cancer. 1998;77(7):1186–1189. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.197. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.1998.197 PMid:9569060 PMCid:PMC2150141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhong X, Isharwal S, Naples JM, Shiff C, Veltri RW, Shao C, et al. Hypermethylation of Genes Detected in Urine from Ghanaian Adults with Bladder Pathology Associated with Schistosoma Hematobum Infection. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059089. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059089 PMid:23527093 PMCid:PMC3601097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le L, Hsieh M. Diagnosing Urogenital Schistosomiasis:Dealing with Diminishing Returns. Trends in parasitology. 2017;33(5):378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2016.12.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2016.12.009 PMid:28094201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bedwani R, El-Khwsky F, Renganathan E, Braga C, Abu Seif H, Azm T, et al. Epidemiology of bladder cancer in Alexandria, Egypt:Tobacco smoking. Int J Cancer. 1997;73(1):64–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970926)73:1<64::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)-1097-0215(19970926)73:1<64::AID-IJC11>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang H, Su YL, Yu H, Qian BY. Meta-analysis of the association between Mir-196a-2 polymorphism and cancer susceptibility. Cancer Biol Med. 2012;9:63–72. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-3941.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu R, Xu Y, Chang J. The expression and significance of KAI1 and Ki67 in bladder transitional cell carcinoma. Chinese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;2(6):888–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02789660. [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Bolkainy MN, Mokhtar NM, Ghoneim MA, Hussein MH. The impact of schistosomiasis on the pathology of bladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;48:2643–2648. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19811215)48:12<2643::aid-cncr2820481216>3.0.co;2-c. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19811215)48:12<2643::AID-CNCR2820481216>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng Y, Amr S, Saleh D, Dash C, Ezzat S, Mikhail N, et al. Urinary bladder cancer risk factors in Egypt:A multicenter case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(3):537–46. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0589. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0589 PMid:22147365 PMCid:PMC3297723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wishahi M, Zakarya A, Hamamm O, Abdel-Rasol M, Badawy H, Elganzoury H, et al. Impact of density of schistosomal antigen expression in urinary bladder tissue on the stratification, cell type, and staging, and prognosis of carcinoma of the bladder in Egyptian patients. Infectious Agents and Cancer 2014. 2014;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-9-21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-9378-9-21 PMid:25018779 PMCid:PMC4094454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eissa S, Habib H, Ali E, Kotb Y. Evaluation of urinary miRNA-96 as a potential biomarker for bladder cancer diagnosis. Medical Oncology. 2015;32:413. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0413-x. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-014-0413-x PMid:25511320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eissa S, Matboli M, Shawky S, Essawy N. Urine biomarkers of schistosomiais and its associated bladder cancer. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 2015;13(8):1–9. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1051032. https://doi.org/10.1586/14787210.2015.1051032 PMid:26105083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conti S, Honeycutt J, Odegaard J, Gonzalgo M, Hsieh M. Alterations in DNA methylation may be the key to early detection and treatment of schistosomal bladder cancer. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2015;9:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003696. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003696 PMid:26042665 PMCid:PMC4456143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Honeycutt J, Hammam O, Fu C, Hsieh M. Controversies and challenges in research on urogenital schistosomiasis-associated bladder cancer. Trends in Parasitology. 2014;30(7):324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2014.05.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2014.05.004 PMid:24913983 PMCid:PMC4085545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McConkey DJ, Lee S, Choi W, Tran M, Majewski T, Lee S, Siefker-Radtke A, Dinney C, Czerniak B. Molecular genetics of bladder cancer:Emerging mechanisms of tumor initiation and progression. Urol Oncol. 2010;28(4):429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.04.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.04.008 PMid:20610280 PMCid:PMC2901550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Metwally NS, Ali SA, Mohamed AM, Khaled HM, Ahmed SA. Levels of certain tumor markers as differential factors between bilharzial and non-biharzial bladder cancer among Egyptian patients. Cancer cell international. 2011;11(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-11-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2867-11-8 PMid:21473769 PMCid:PMC3097143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maruf M, Brancato SJ, Agarwal PK. Nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer:a primer on immunotherapy. Cancer Biol Med. 2016;13(2):194. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2016.0020. https://doi.org/10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2016.0020 PMid:27458527 PMCid:PMC4944546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]