Abstract

Background

The functioning of the family of origin seems to be one of the key variables that contribute to life satisfaction. Since relationships with one’s parents are associated with well-being throughout life, the purpose of our study was to examine the association between family functioning and life satisfaction among Polish adults. Moreover, because some researchers postulate that family functioning affects quality of life directly as well as indirectly through some other variables, we focused on investigating how emotional intelligence might affect the link between family functioning and life satisfaction, as the character of this relationship has received surprisingly little attention.

Patients, Methods and Data Collection

The sample consisted of 204 participants (86% women). We measured family functioning, satisfaction with life, and emotional intelligence. The data were collected using online forums through convenience sampling on the basis of availability and the willingness of the participants to respond.

Results

The results showed that both life satisfaction and emotional intelligence correlated positively and significantly with cohesion, flexibility, communication, and family satisfaction. Life satisfaction correlated negatively and significantly with enmeshed, disengaged, and chaotic functioning. In contrast, emotional intelligence correlated negatively and significantly only with chaotic and disengaged functioning. Moreover, emotional intelligence partially mediated the relationship between six dimensions of family functioning (cohesion, flexibility, communication, family satisfaction, disengagement, and chaos) and life satisfaction.

Conclusion

Our findings provide evidence of an indirect association between family functioning and life satisfaction through the mediating role of emotional intelligence. They indicate that individuals who evaluate their family functioning as cohesive, flexible, communicative, and fulfilled, are more likely to process their own emotions and enjoy higher life satisfaction. Conversely, assessment of family of origin as disengaged and chaotic may diminish the ability to manage one’s own emotions, which, in turn, can lead to lower life satisfaction.

Keywords: family functioning, life satisfaction, emotional intelligence, adults

Introduction

Life satisfaction commonly denotes a judgmental process in which individuals holistically evaluate the condition of their lives based on their own distinct and unique set of criteria.1 A global assessment of life satisfaction refers to subjective happiness2,3 and can be considered, along with subjective well-being and quality of life, a facets of global well-being. In the literature, these terms are often treated as convergent variables, although not all researchers accept this perspective.4 However, since the latest studies provide empirical support for a large overlap5 and interchangeable use of these constructs,6,7 the term “life satisfaction” can be reasonably claimed as an indicator of a person’s overall well-being.8

Currently, there is much debate with respect to the importance of different factors in subjective well-being.9 The “bottom-up” approach suggests that people’s overall life satisfaction depends, to a great extent, on different events or many concrete domains such as family, work, and leisure time.10 Among all these factors, family of origin seems to be one of the key variables that contribute to life satisfaction. More specifically, the Circumplex Model of Marital and Family System proposes a compelling theoretical and empirical framework for understanding the relationship between parental bonds and individual well-being.11,12 According to this model, family functioning is evaluated in three crucial dimensions: cohesion, flexibility, and communication.11 Cohesion refers to the emotional connection that family members have towards one another. Flexibility implies the amount of change in family leadership, control, discipline, negotiation styles, and relationship rules. Communication stands for a parameter that helps the family modify both cohesion and flexibility. It consists of the ability to listen to other members with respect and understanding, and share with them one’s own feelings and experiences. Olson lists two levels of cohesion (disengaged and enmeshed) and two levels of flexibility (rigid and chaotic). Families characterized by extreme or unbalanced behaviors, where there is low interaction (disengagement) or too much consensus within the family and/or too little independence (enmeshment), are at risk for disfunction. In the long term, separatedness and symbiosis in the family are not good markers of its functionality.13 Similarly, when the structure of the family is inflexible, with parents imposing the rules and decisions (stiffness) or when the family is characterized by permissiveness and frequent change of rules (chaos), the family displays traits of a rigid system.

The findings in the empirical literature support the links between specific family-related factors and several well-being indices. For example, Suldo and Huebner14 show that the attainment of life satisfaction is strongly associated with family functioning. More precisely, Manzi and colleagues15 observe that cohesive family relationships among young Italians are associated positively with life satisfaction. Kagitçibasi16 finds in her study conducted in the UK that family enmeshment correlates negatively with well-being. Manzi15 and Vandeleur17 report that togetherness within the family is linked to personal well-being and satisfaction in adults. Olson et al12 stress that emotional bonds between family members and the capacity of adaptation to different changes influence positively their latter life satisfaction. Caron et al18 also point out that overall participant–parent relationship quality serves as one of the most significant predictors of psychological well-being. According to these results, a secure relationship with their parents contributes positively to quality of life across generations.19 In this context, the first goal of our study was to verify whether having a balanced relationship with one’s own family of origin would be positively associated with life satisfaction and, conversely, whether experiencing an unbalanced relationship would be linked negatively to life satisfaction.

Emotional intelligence can be another important aspect of life satisfaction. In fact, it is widely acknowledged that individuals with high levels of emotional intelligence, measured as a trait and as an ability, report higher life satisfaction.20–25 Some other studies confirm that emotional intelligence is a significant predictor of hedonic and eudemonic well-being.26,27 The meta-analysis conducted by Sánchez-Álvarez and colleagues28 on a total of 25 studies and on a combined sample of more than 8000 participants provides evidence of a significant positive relationship between emotional intelligence and life satisfaction (r = 0.32). These positive associations between emotional intelligence and life satisfaction might be due to the essence of emotional intelligence, considered as a set of abilities that consist of perceiving, understanding, harnessing, and managing the complexity and nuances of emotional experience in the self and others.29,30 In this context, the second goal of our research was to assess if emotional intelligence would show positive association with life satisfaction.

Finally, besides studies showing a direct relationship between family functioning and life satisfaction, there is some evidence that there can also be an indirect effect of family functioning on life satisfaction through health-promoting behaviors,19 personal growth,31 romantic attachment,32 stress resistance,31 savoring positive experiences,33 positive coping styles, and perceived social support.34 Although there are no studies specifically targeting emotional intelligence and its role in the relationship between family functioning and life satisfaction, the existing literature suggests that such an effect is plausible. Since relationships with one’s parents are associated with well-being throughout life into and beyond the offspring’s middle years,35 the purpose of our study was to examine the association between family functioning and life satisfaction among Polish adults. The rationale for undertaking this type of analysis results from the fact that most of the research on this subject comes from Anglo-Saxon and Western European samples15 and there is a lack of similar studies in Poland. Moreover, because some researchers postulate that family functioning affects quality of life directly as well as indirectly through some other variables,19,31 we focused on investigating how emotional intelligence might affect the link between family functioning and life satisfaction, as the character of this relationship has received surprisingly little attention.36 More precisely, we wanted to test whether there would be a contrast in the mediatory role of emotional intelligence on the effects of positive and negative aspects of family functioning on life satisfaction. A mediation analysis could help to bridge the gap in the research on the process through which family functioning may impact life satisfaction in the context of Polish adults.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 204 Polish adults (86% women) between the ages of 18 and 70. The average age was 31 (M = 31.00; SD = 9.49). The biggest group was formed by highly educated persons (61%), followed by those with secondary education (38%), and primary education (1%). In terms of the role-played in the family, 57% of participants declared being a mother, 29% a daughter, 11% a son, and 3% a father. Almost 28% of respondents reported having 1 child, 22% – 2 children, 10% – 3 children, and 40% – no children. With respect to current marital status, 47% of participants were married, 27% – never married, 22% – living in an informal relationship, 3% – divorced, and 1% – widowed.

Data Collection

The data were collected using online forums through convenience sampling on the basis of the availability and willingness of participants to respond. All the respondents were primed with the goal of the research and the privacy protection policy. Those who decided to take part in the study were given broad information about its purpose and were prompted with a web-based informed consent. Only after presenting their agreement, the participants were invited to complete the questionnaires. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology at the University of Szczecin and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measurement

The Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Package (FACES IV; Olson, 2011), in the Polish version adapted by Margasiński,37 is a self-report questionnaire that evaluates family functioning through the primary dimensions of the Circumplex Model of Marital and Family Systems.38 FACES IV contains 62 items to assess eight scales: two balanced scales (cohesion and flexibility), four unbalanced scales (enmeshed, disengaged, chaotic, and rigid), communication, and family life satisfaction. The balanced scales reflect harmony, assessing a positive and well-functioning family environment. More specifically, cohesion and flexibility denote a family emotional bond, power, leadership, and rules (“In our family, we like to spend some of our free time together”). In contrast, unbalanced scales refer to a problematic family system. For example, an enmeshed relationship refers to an intense amount of emotional closeness, loyalty, dependence on each other, a lack of personal separateness and private space (“Family members feel pressured to spend most of their free time together”). A disengaged relationship implies an extreme emotional disconnectedness, little involvement within the family, and independence (“Family members feel closer to people outside the family than to other family members”). Rigidity (“There are strict consequences for breaking the rules in our family”) and chaos (“There is no leadership in our family”) mean, respectively, either strict or lax family power, leadership, and rules.39 Communication refers to positive interactions, and satisfaction assesses the quality of life in the current family system.40 Respondents used 5-point Likert scales: from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree for the cohesion, flexibility, enmeshed, disengaged, chaotic, rigid, and satisfaction, communication, and life satisfaction scales, and from 1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = extremely satisfied for the communication scale. In the present study, the Cronbach alpha coefficients were as follows: cohesion (α = 0.84), flexibility (α = 0.73), enmeshed (α = 0.72), disengaged (α = 0.85), chaotic (α = 0.66), rigid (α = 0.68), communication (α = 0.91), and family satisfaction (α = 0.93). The internal consistency was higher than in the Italian39,41 and Polish validations.37

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS),42 in the Polish version adapted by Juczyński,43 measures satisfaction with the participant’s life embraced as a whole. The questionnaire is narrowly focused to assess the global aspects of satisfaction. Respondents declare how much they agree or disagree with each of the 5 items, using a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). In the current study, the SWLS demonstrated a good internal consistency with Cronbach’s α = 0.83.

The Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (INTE),25 in the Polish version adapted by Jaworowska and Matczak,44 is a well-known 33-item self-report measure of emotional intelligence. It is based on the Salovey and Mayer model: the appraisal and expression of emotion, the regulation of emotion, and the use of emotions in thinking and acting.45 Respondents use a 5-point scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree to designate to what extent each item illustrates their agreement. The scores are from 33 to 165. The higher the score, the higher the emotional intelligence. The internal consistency in the original studies showed an alpha of 0.90. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient also was 0.90.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 23. Since the data were gathered through an Internet platform that did not allow respondents to proceed unless they answered all questions, we had a complete dataset with no missing values. Descriptive statistics of means, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis were checked, with the normality assumption met in the case of all the variables considered in the study. In fact, indices of all the variables were less than the ±2 which are commonly considered the acceptable limits of a normal distribution.46,47

The internal reliability (Cronbach’s α) was used for all subscales applied. The correlation analysis was done using Pearson’s r coefficient. A linear regression analysis was adopted to diagnose multicollinearity and to test if and how much age and sex would act as potential confounders in the model and distort the relationship between the exposure and outcome variables.

We used a linear regression model to check the data for outliers. We computed Mahalanobis’ distance and Cook’s distance. Moreover, the participants’ sex and age were included to control for their potential influence on the relationship between the independent variable of interest (family functioning) and with the outcome variable (life satisfaction). In fact, according to some results,48 family functioning is more important for the level of satisfaction among women than among men. Moreover, in other studies,49 the personal, subjective level of life satisfaction increased with age, even after controlling for the effects of other variables. The potential confounders were entered at Step 1. All variables hypothesized as predictors of life satisfaction were entered at Step 2.

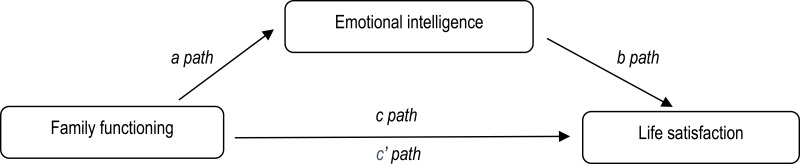

The PROCESS macro for SPSS (version 3.2) was run to establish the extent to which family functioning influences life satisfaction through emotional intelligence. Family functioning was the independent variable and satisfaction with life was the dependent variable. Emotional intelligence was included as a mediating variable. Thus, there were eight single-level mediation models no. 4,50 involving three-variable systems (Figure 1). It was assumed that the occurrence of full mediation would take place if the c’ path was no longer significant after introducing the mediator variable. Instead, partial mediation would occur if the path c’ was smaller in magnitude than the c path, but still significant.51 For the present analysis, the 95% confidence interval of the indirect effects was calculated using 5000 bootstrapped resamples. This method appears to be superior to traditional mediation analyses because it does not require the data to adhere to assumptions of normality.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of the role of EI in the relationship between dimensions of family functioning and life satisfaction.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The cohesion and flexibility, enmeshed, disengaged, chaotic and rigid, and communication and family satisfaction scales of FACES IV, global emotional intelligence, and life satisfaction were screened for skewness and kurtosis to evaluate the normality of the scales’ distributions. We assumed indices less than the ±2 commonly considered acceptable limits of a normal distribution.46,47 No variables exceeded the cutoffs of ±2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for FACES IV, SWLS, and INTE (N = 204)

| Scales | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. COH | 27.65 | 4.78 | −0.756 | −0.004 |

| 2. FLX | 23.94 | 4.74 | −0.638 | −0.024 |

| 3. ENM | 14.34 | 5.71 | 0.793 | −0.341 |

| 4. DIS | 13.56 | 4.38 | 0.657 | 0.252 |

| 5. CHA | 16.46 | 4.65 | 0.255 | −0.242 |

| 6. RIG | 16.97 | 4.26 | 0.227 | −0.018 |

| 7. COM | 37.35 | 7.75 | −0.710 | 0.372 |

| 8. FSA | 41.56 | 8.92 | −0.751 | −0.076 |

| 9. LS | 22.99 | 5.54 | −0.533 | −0.038 |

| 10. EI | 127.64 | 14.58 | −0.167 | −0.315 |

Abbreviations: COH, cohesion; FLX, flexibility; ENM, enmeshed; DIS, disengaged; CHA, chaotic; RIG, rigid; COM, communication; FSA, family satisfaction; LS, life satisfaction; EI, emotional intelligence.

Correlations

With respect to the first and second goal of the present study, both life satisfaction and emotional intelligence correlated positively and significantly with cohesion, flexibility, communication, and family satisfaction (Table 2). The correlations between emotional intelligence and dimensions of family functioning were lower than those of life satisfaction. Moreover, life satisfaction correlated negatively and significantly with enmeshed, disengaged, and chaotic functioning. Instead, emotional intelligence correlated negatively and significantly with disengaged and chaotic functioning.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Dimensions of FACES IV, SWLS, and INTE (N = 204)

| COH | FLX | ENM | DIS | CHA | RIG | COM | FSA | LS | EI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. COH | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. FLX | 0.73*** | 1 | ||||||||

| 3. ENM | −0.76*** | −0.58*** | 1 | |||||||

| 4. DIS | −0.41*** | −0.26*** | 0.50*** | 1 | ||||||

| 5. CHA | −0.54*** | −0.56*** | 0.63*** | 0.40*** | 1 | |||||

| 6. RIG | −0.03 | 0.24*** | 0.17* | 0.41*** | −0.01 | 1 | ||||

| 7. COM | 0.75*** | 0.66*** | −0.69*** | −0.39*** | −0.54*** | −0.11 | 1 | |||

| 8. FSA | 0.77*** | 0.68*** | −0.70*** | −0.34*** | −0.53*** | −0.06 | 0.87*** | 1 | ||

| 9. LS | 0.50*** | 0.50*** | −0.38*** | −0.21** | −0.38*** | 0.01 | 0.49*** | 0.50*** | 1 | |

| 10. EI | 0.19** | 0.23** | −0.10 | −0.20** | −0.19** | −0.04 | 0.15* | 0.21** | 0.35*** | 1 |

Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Abbreviations: COH, cohesion; FLX, flexibility; ENM, enmeshed; DIS, disengaged; CHA, chaotic; RIG, rigid; COM, communication; FSA, family satisfaction; LS, life satisfaction; EI, emotional intelligence.

Multicollinearity and Confounding

In order to identify multicollinearity,52 the regression model was tested because of correlations among all input variables (dimensions of family functioning and emotional intelligence). In the whole sample, the tolerance values ranged from 0.266 to 0.888, above the critical value of 0.1 suggested by Menard53 as a considerable collinearity problem. The variance inflation factor (VIF) values ranged from 1.126 to 3.766, respectively, not exceeding the commonly assumed threshold of 10.0.45,54 Both results suggest that multicollinearity was unlikely to be an issue in our study. Mahalanobis’ distance procedure was conducted, using the chi-square distribution with a very conservative probability estimate for a case being an outlier (p < 0.001).55 Only 2 of 204 cases were identified as probable multivariate outliers, which seems to be a very low number since multivariate normality is seldom satisfied in real-life data.56 However, because a reanalysis with the outliers removed showed that there were minimal changes in the correlations, we decided not to drop them from the sample. Moreover, Cook’s value (between 0.000 and 0.093) was under the point at which the researcher should be concerned (less than 1),55 suggesting that the cases were not likely problematic in terms of having an excessive effect on the model. Hierarchical regression analyses also showed that neither sex nor age made a significant unique contribution to the model, explaining only 1% of the variance (R2 = 0.001): sex (β = −0.026, t = −0.370, p = 0.712) and age (β = 0.094, t = 1.330, p = 0.185). The predictors explained an additional 32% of the variance, even after controlling for the effects of potential confounders (sex and age).

Mediation Analysis

In the following part of the analyses, emotional intelligence was introduced as a potential mediator which could weaken, strengthen or have no influence on the existing correlation between the independent variable (dimensions of family functioning) and the dependent variable (life satisfaction) (Figure 1).

The PROCESS macro for SPSS (Table 3) showed that the c path (the direct effect) reduced in magnitude after the introduction of emotional intelligence in 6 models out of 8 (c’ path).

Table 3.

The Role of Emotional Intelligence in the Relationship Between Dimensions of Family Functioning and Life Satisfaction

| a Path | b Path | c Path | c’ Path | Indirect Effect | B(SE) | Lower CI | Upper CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. COH – EI – LS | 0.59*** | 0.10*** | 0.58*** | 0.52*** | 0.0602 | 0.0274 | 0.0136 | 0.1208 |

| 2. FLX – EI – LS | 0.73*** | 0.09*** | 0.59*** | 0.52*** | 0.0691 | 0.0276 | 0.0216 | 0.1284 |

| 3. ENM – EI – LS | −0.25(ni) | 0.12*** | −0.37*** | −0.34*** | −0.0309 | 0.0240 | −0.0818 | 0.0137 |

| 4. DIS – EI – LS | −0.66** | 0.12*** | −0.27** | −0.19* | −0.0826 | 0.0356 | −0.1596 | −0.0214 |

| 5. CHA – EI – LS | −0.61** | 0.11*** | −0.45*** | −0.39*** | −0.0683 | 0.0299 | −0.1332 | −0.0171 |

| 6. RIG – EI – LS | −0.14(ni) | 0.13*** | 0.01(ni) | −0.03(ni) | −0.0192 | 0.0356 | −0.0971 | 0.0455 |

| 7. COM – EI – LS | 0.28** | 0.10*** | 0.35*** | 0.32*** | 0.0313 | 0.0168 | 0.0027 | 0.0678 |

| 8. FSA– EI – LS | 0.34** | 0.09*** | 0.31*** | 0.28*** | 0.0342 | 0.0146 | 0.0095 | 0.0664 |

Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Abbreviations: ni, nonsignificant; COH, cohesion; FLX, flexibility; ENM, enmeshed; DIS, disengaged; CHA, chaotic; RIG, rigid; COM, communication; FSA, family satisfaction; LS, life satisfaction; EI, emotional Intelligence.

On the basis of the outcomes found, it can be stated that emotional intelligence partially mediates the relationship between four balanced dimensions of family functioning (cohesion; flexibility; communication; family satisfaction) and life satisfaction. More specifically, all of these dimensions directly and indirectly influence life satisfaction through emotional intelligence. Moreover, emotional intelligence partially mediates the relationship between two unbalanced components of family functioning (disengagement and chaos) and life satisfaction, suggesting that both forms also affect life satisfaction directly and indirectly through emotional intelligence. The other two unbalanced dimensions of family functioning (enmeshment and rigidity) and life satisfaction were not mediated by emotional intelligence, as evidenced by a confidence interval (LOWER CI and UPPER CI) for the indirect effect containing zero.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was triple. The first objective was to determine whether there was an association between the dimensions of family functioning, and life satisfaction. The second goal was to examine the association between emotional intelligence and life satisfaction. The third aim was to assess the mediatory role of emotional intelligence on the relationship between family functioning and life satisfaction.

With respect to the first aim, our outcomes are in line with other studies. For example, Manzi et al15 found that cohesion, understood as the family bond, was associated with higher life satisfaction both among Italian and English adolescents. Accordingly, Vandeleur and colleagues17 showed that experiencing a higher familial sense of togetherness, closeness, and satisfaction with family ties contributed to emotional well-being in all family members. Other researchers57 pointed out that the stronger the cohesion the participants perceived in their families of the origin, and the higher they evaluated their communication and satisfaction with family life, the more positively they viewed their adults' roles and responsibilities. In another study,58 the retrospective perception of adults’ own families in aspects of clarity of expression, responsibility, respect and openness to others, acceptance of separation and loss, range of feelings, mood and tone, conflict resolution, empathy, and trust demonstrated strong-to-moderate associations with their life satisfaction. Finally, healthy functioning, affective involvement,41 and recalled parental care from both parents were related to higher well-being at several points in the course of life.59 Such findings confirm the Olson Circumplex Model38 according to which the experience of a balanced family helps in better regulation of emotional tensions related to daily life. Conversely, the pattern of inverse relationships reduces the sense of satisfaction with life. In some studies,15 enmeshment, reflecting blurred and weak boundaries were connected to anxiety and depressive symptoms. Heaven58 observed that irrational beliefs about the family were associated with participants who exhibited lower empathy and sensitivity to others. Moreover, a perception of both parents as controlling was positively associated with anxiety41,59 and negatively with global life satisfaction at all ages.60

With regard to the second goal, a pattern of positive correlation between emotional intelligence and life satisfaction also confirms the previous literature. Although, in a study by Augusto Landa et al,61 different components of emotional intelligence (emotions clarity and emotional repair) explained a small percentage of the variance (1%) of life satisfaction, there is a growing range of empirical evidence which suggests that individuals with higher emotional intelligence tend to manage their emotions better, which translates into higher life satisfaction.62,63 Moreover, emotional intelligence was found to be connected with a range of outcomes that in a wide sense can be considered as relating to quality of life.64 For example, emotional intelligence contributed to life and work satisfaction among teachers65 and was a significant predictor of life satisfaction in students.66

The third goal and the central finding of our study were related to the mediatory role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between family functioning and life satisfaction. On the one hand, the outcomes indicate that individuals who evaluate their family functioning as cohesive, flexible, communicative, and fulfilled are more likely to process their own emotions to distinguish among them, and to use this information to guide their thinking and actions. Such an ability may lead to experiencing greater life satisfaction. In fact, according to Blechman,67 adaptive family functioning expresses itself in the open exchange, regulation, and expression of emotions. Parental emotional intelligence was found to be one of the strongest predictors of offspring emotional intelligence,41 and to play a crucial role in the development of one’s emotional and social competences.68 Moreover, family flexibility and cohesion were valuable factors in better emotional intelligence among emerging adults.69 In other studies, Alavi and colleagues69 found that higher family functioning correlated with higher emotional intelligence considered as a trait. Therefore, the way individuals regulate their emotions on the basis of their personal experience of family functioning can have a great influence on their well-being,70 personal achievement, and psychosocial functioning.71

On the other hand, the results show that people who assess the functioning of their family of origin as disengaged and chaotic can present less adaptive forms of emotion regulation that, in turn, can lead to lower life satisfaction. The perception of one’s own family as poor in parental bonding because of a lack of care, or because of high overprotection can hamper emotional development and result in less functional ways of regulating personal emotions.72,73 Some studies showed that parental behaviors, such as psychological control, restrict the development of emotional intelligence, which can result in internalization or externalization of problems. Thus, the experience of unbalanced family functioning might make it more problematic to develop a positive model of the self and to manage one’s own emotions. Consequently, lower emotional intelligence can lead to poorer well-being.

Implications

The effects of both positive and negative aspects of family functioning on life satisfaction are mediated by emotional intelligence, and have important developmental implications. Family of origin appears to be an important antecedent of emotional intelligence and it has significant impact on the ability to understand and manage one’s own emotions throughout life. In turn, the ability to self-regulate one’s own emotions is crucial in the promotion of optimal psychological functioning and life satisfaction. Based on the present study, it can be seen that, while recalling balanced forms of family functioning is associated with higher emotional intelligence and life satisfaction, emotional disconnectedness, little involvement within the family, permissiveness, and frequent change of rules are linked to experiencing lower emotional intelligence, and consequently, to a significant reduction of life satisfaction. Therefore, it seems essential for adult growth to encourage the development of emotional intelligence skills (recognizing, understanding, and expressing one’s own emotions) in order to experience greater life satisfaction despite undergoing unpleasant emotions related to one’s own family history.

Limitations

Despite the relevance of these outcomes, we should address several limitations. First, although the results partially supported the proposed mediatory model, the cross-sectional nature of the data, with no temporal analysis, does not allow any deductions on causal and predictive influence. Longitudinal and experimental designs would provide a more precise illustration of the relationships examined. Second, the data were collected through the use of self-report measures that might increase desirability bias and affect the validity of the results. Therefore, a cautious interpretation is suggested when applying the outcomes. In future studies, it would be valuable to use a social desirability scale in order to prevent or reduce such a bias. Third, we assumed that better family functioning leads to the development of emotional intelligence. However, the relationship between both concepts might be bidirectional. Therefore, there is a need for future research to examine the potential mediatory character of family functioning within the relationship between emotional intelligence and life satisfaction. In spite of these limitations, the current research extends our understanding of the interplay among family functioning, emotional intelligence, and life satisfaction. Moreover, it offers significant support for the mediatory role of emotional intelligence between some balanced and unbalanced dimensions of family functioning and life satisfaction.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the study participants.

Data Sharing Statement

The data sets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Pavot W, Diener E. The satisfaction with life scale and emerging construct of life satisfaction. J Posit Psychol. 2008;3(2):137–152. doi: 10.1080/17439760701756946 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diener E. Guidelines for national indicators of subjective well-being and well-being. J Happiness Stud. 2006;7(4):397–404. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9000-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diener E, Pressman SD, Hunter J, Delgadillo-Chase D. If, why, and when subjective well-being influences health, and future needed research. Appl Psychol Health Wellbeing. 2017;9(2):133–167. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lachmann B, Sariyska R, Kannen C, et al. Contributing to overall life satisfaction: personality traits versus life satisfaction variable revisited – is replication impossible? Behav Sci. 2018;8(1):1. doi: 10.3390/bs8010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nave CS, Sherman RA, Funder DC. Beyond self-report in the study of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being: correlations with acquaintance reports, clinician judgments and directly observed social behavior. J Res Pers. 2008;42(3):643–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veenhoven R. Happiness: also known as “life satisfaction” and “subjective well-being” In: Land KC, Michalos AC, Joseph Sirgy M, editors. Handbook of Social Indicators and Quality of Life Research. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2012:63–77. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medvedev ON, Landhuis CE. Exploring constructs of well-being, happiness and quality of life. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4903. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joshanloo M, Jovanović V, Taylor T. A multidimensional understanding of prosperity and well-being at country level: data-driven explorations. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schnettler B, Miranda-Zapata E, Grunert KG, et al. Life satisfaction of university students in relation to family and food Country. Front Psychol. 2017;8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loewe N, Bagherzadeh M, Araya-Castillo L, Thieme C, Batista-Foguet JM. Life domain satisfactions as predictors of overall life satisfaction among workers: evidence from Chile. Soc Indic Res. 2014;118(1):71–86. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0408-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson DH. Circumplex model of marital and family systems. J Fam Ther. 2000;22(2):144–167. doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.00144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olson DH, Lavee Y. Family systems and family stress: a family life cycle perspective In: Kreppner K, Lerner RM, editors. Family Systems and Lifespan Development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1989:165–195. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rada C, Olson DH. Circumplex model of marital and family systems (FACES III) in Romania. Annuaire Roumain d’Anthropologie. 2016;53:11–29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suldo SM, Huebner ES. The role of life satisfaction in the relationship between authoritative parenting dimensions and adolescent problem behavior. Soc Indic Res. 2004;66(1):165–195. doi: 10.1023/B:SOCI.0000007498.62080.1e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manzi C, Vignoles VL, Regalia C, Scabini E. Cohesion and enmeshment revisited: differentiation, identity, and well-being in two European cultures. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68(3):673–689. doi: 10.1111/jomf.2006.68.issue-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kagitçibasi C. The autonomous-relational self: a new synthesis. Eur Psychol. 1996;1(3):180–186. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.1.3.180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandeleur CL, Jeanpretre N, Perrez M, Schoebi D. Cohesion, satisfaction with family bonds, and emotional well-being in families with adolescents. J Marriage Fam. 2009;71(5):1205–1219. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00664.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caron A, Lafontaine MF, Bureau JF, Levesque C, Johnson SM. Comparisons of close relationships: an evaluation of relationship quality and patterns of attachment to parents, friends, and romantic partners in young adults. Can J Behav Sci. 2012;44(4):245–256. doi: 10.1037/a0028013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali S, Malik JA. Consistency of prediction across generation: explaining quality of life by family functioning and health-promoting behaviors. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(9):2105–2112. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0942-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Extremera N, Fernándes-Berrocal P. Perceived emotional intelligence and life satisfaction: predictive and incremental validity using the trait meta-mood scale. Pers Individ Differ. 2005;39(5):937–948. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.03.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kong F, Zhao J. Affective mediators of the relationship between trait emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in young adults. Pers Individ Differ. 2013;54(2):197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.08.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong F, Zhao J. Social support mediates the impact of emotional intelligence on mental distress and life satisfaction in Chinese young adults. Pers Individ Differ. 2012;53(4):513–517. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong F, Zhao J. Emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in Chinese university students: the mediating role of self-esteem and social support. Pers Individ Differ. 2012;53(8):1039–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-Zafra E, Ramos-Álvarez MM, El Ghoudani K, et al. Social support and emotional intelligence as protective resources for well-being in Moroccan adolescents. Front Psychol. 2019;10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schutte NS, Malouff JM. Emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between mindfulness and subjective well-being. Pers Individ Differ. 2011;50(7):1116–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayer J, Roberts R, Barsade SG. Human abilities: emotional intelligence. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:507–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Extremera N, Ruiz-Aranda D, Pineda-Galán C, Salguero JM. Emotional intelligence and its relation with hedonic and eudaimonic well-being: a prospective study. Pers Individ Differ. 2011;51(1):11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.02.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sánchez-Álvarez N, Extremera N, Fernández-Berrocal P. The relation between emotional intelligence and subjective well-being: a meta-analytic investigation. J Posit Psychol. 2016;11(3):276–285. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1058968 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR, Sitarenios G. Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion. 2003;3(1):97–105. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brackett MA, Salovey P. Measuring emotional intelligence with the Mayer-Salovery-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT). Psicothema. 2006;18(1):34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robitschek C, Kashubeck S. A structural model of parental alcoholism, family functioning, and psychological health: the mediating effects of hardiness and personal growth orientation. J Couns Psychol. 1999;46(2):159–172. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.46.2.159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guarnieri S, Smorti M, Tani F. Attachment relationships and life satisfaction during emerging adulthood. Soc Indic Res. 2015;121(3):833–847. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0655-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheung YMR, Leung MC, Chiu HT, Kwan LYJ, Yee TSL, Hou WK. Family functioning and psychological outcomes in emerging adulthood: savoring positive experiences as a mediating mechanism. J Soc Pers Relat. 2019;36(9):2693–2713. doi: 10.1177/0265407518798499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu S, Zheng X. The effect of family adaptation and cohesion on the well-being of married women: a multiple mediation effect. J Gen Psychol. 2019. doi: 10.1080/00221309.2019.1635075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polenick CA, Fredman SJ, Birditt KS, Zarit SH. Relationship quality with parents: implications for own and partner well-being in middle-aged couples. Fam Process. 2018;57(1):253–268. doi: 10.1111/famp.12275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Botha F, Booysen F. Family functioning and life satisfaction and happiness in South African households. Soc Indic Res. 2014;119(1):163–182. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0485-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margasiński A. The polish adaptation of FACES IV-SOR. Pol J App Psychol. 2015;13(1):43–66. doi: 10.1515/pjap-2015-0025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olson DH. FACES IV and the circumplex model: validation study. J Marital Fam Ther. 2011;3(1):64–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00175.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Everri M, Mancini T, Fruggeri L. The role of rigidity in adaptive and maladaptive families assessed by FACES IV: the points of view of adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(10):2987–2997. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0460-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koutra K, Triliva S, Roumeliotaki T, Lionis CH, Vgontzas AN. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Greek version of the family adaptability and cohesion evaluation scales IV package (FACES IV package). J Fam Issues. 2012;34(12):1647–1672. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12462818 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baiocco R, Cacioppo M, Laghi F, Tafà M. Factorial and construct validity of FACES IV among Italian adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2013;22(7):962–970. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9658-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Juczyński Z. Narzędzia pomiaru w promocji i psychologii zdrowia [Measurement tools in health promotion and psychology]. Psychological Test Laboratory Polish Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jaworowska A, Matczak A. Kwestionariusz Inteligencji Emocjonalnej Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire]. Psychological Test Laboratory Polish Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Brien RM. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant. 2007;41(5):673–690. doi: 10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.George D, Mallery M. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. Pearson; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gravetter F, Wallnau L. Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. Wadsworth; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nordenmark M. The importance of job and family satisfaction for happiness among women and men in different gender regimes. Societies. 2018;8(1). doi: 10.3390/soc8010001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Angelini V, Cavapozzi D, Paccagnella O. Age, health and life satisfaction among older Europeans. Soc Indic Res. 2012;105(2):293–308. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9882-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Proces Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rucker DD, Preacher KJ, Tormala ZL, Petty RE. Mediation analysis in social psychology: current practices and new recommendations. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2011;5/6:359–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim HW, Chan HC, Gupta S. Value-based adoption of mobile internet: an empirical investigation. Decis Support Syst. 2007;43(1):111–126. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2005.05.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Menard S. Applied Logistic Regression Analysis. SAGE; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dattalo P. Analysis of Multiple Dependent Variables. Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fidell LS, Tabachnick BG. Preparatory data analysis In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Handbook of Psychology: Research Methods in Psychology. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2003:115–141. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Min M, Bambacas M, Zhu Y. Strategic Human Resource Management in China: A Multiple Perspective. Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Borchet J, Lewandowska-Walter A, Rostowska T. Parentification in late adolescence and selected features of the family system. Health Psychol Rep. 2016;4(2):116–127. doi: 10.5114/hpr.2016.55921 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heaven P, Searight HR, Chastain J, Skitka LJ. The Relationship between perceived family health and personality functioning among Australian adolescents. Am J Fam Ther. 1996;24(4):358–366. doi: 10.1080/01926189608251047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seibel FL, Johnson WB. Parental control, trait anxiety, and satisfaction with life in college students. Psychol Rep. 2001;88(2):473–480. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.2.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stafford M, Kuh DL, Gale CR, Mishra G, Richards M. Parent-child relationships and offspring’s positive mental wellbeing from adolescence to early older age. J Posit Psychol. 2016;11(3):326–337. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1081971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Augusto Landa JM, López-Zafra E, de Antoñana M, Pulido M. Perceived emotional intelligence and life satisfaction among university teachers. Psicothema. 2006;18:152–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun P, Wang S, Kong F. Core self-evaluation as mediator and moderator of the relationship between emotional intelligence and life satisfaction. Soc Indic Res. 2014;118(1):173–180. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0413-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Urquijo I, Extremera N, Villa A. Emotional intelligence, life satisfaction, and psychological well-being in graduates: the mediating effect of perceived stress. Appl Res Qual Life. 2016;11(4):1241–1252. doi: 10.1007/s11482-015-9432-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Austin EJ, Saklofske DH, Egan V. Personality, well-being and health correlates of trait emotional intelligence. Pers Individ Differ. 2005;38(3):547–558. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ignat AA, Clipa O. Teachers’ satisfaction with life, job satisfaction and their emotional intelligence. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;33:498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Petrides KV, Pita R, Kokkinaki F. The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. Br J Psychol. 2007;98:273–289. doi: 10.1348/000712606X120618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blechman EA. A new look at emotions and the family: A model of effective family communication In: Blechman EA, editor. Emotions and the Family: For Better or Worse. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1990:201–224. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chandran A, Nair BP. Family climate as a predictor of emotional intelligence in adolescence. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol. 2015;41(1):167–173. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alavi M, Mehrinezhad SA, Amini M, Parthaman Singh MKA. Family functioning and trait emotional intelligence among youth. Health Psychol Open. 2017;4(2):1–5. doi: 10.1177/2055102917748461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Quoidbach J, Berry EV, Hansenne M, Mikolajczak M. Positive emotion regulation and well-being: comparing the impact of eight savoring and dampening strategies. Pers Individ Differ. 2010;49(5):368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.pajd.2010.03.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blandon AY, Calkins SD, Keane SP, O’Brien M. Individual differences in trajectories of emotion regulation process. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(4):1110–1123. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lindblad-Goldberg M, Northey WF. Ecosystemic structural family therapy: theoretical and clinical foundations. Contemp Fam Ther. 2013;35:147–160. doi: 10.1007/s10591-012-9224-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mannarini S, Balottin L, Palmieri A, Carotenuto F. Emotion regulation and parental bonding in families of adolescents with internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1493. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]