Abstract

Background

Acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection progresses to chronicity in the majority of patients. In order to prevent the progression to chronic disease, several studies have assessed interferon in patients with acute hepatitis C.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to assess the efficacy of interferon in acute HCV infection.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, and the abstracts of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (June 2001). We also contacted pharmaceutical companies to obtain unpublished trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised clinical trials comparing interferon with placebo or no treatment, and published as an article, abstract, or letter were selected. No language limitations were used.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. The following endpoints were analysed: normalization of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity at the end of treatment (biochemical ETR); sustained ALT normalization at the end follow‐up (biochemical SR); disappearance of serum HCV RNA by polymerase chain reaction assay at the end of treatment (virologic ETR) and at the end of follow‐up (virologic SR). Histologic data and adverse events were also recorded. Assessment of drug efficacy used the methods of Peto and Der Simonian and Laird.

Main results

Six randomised trials involving 206 patients with acute hepatitis C met the inclusion criteria. Four trials assessing interferon alfa‐2b in 141 patients, all with transfusion‐acquired acute hepatitis C, were included. They demonstrated no significant heterogeneity in the outcomes assessed. When compared with no treatment, interferon alfa‐2b was associated with an increase in the rates of virologic ETR and SR by 45% (95% CI 31‐59%, P < 0.00001) and 29% (95% CI 14‐44%, P = 0.0002), respectively. The virologic ETR was 42% (95% CI: 30‐56%) in the interferon alfa‐2b group versus 4% (95% CI 0‐13%, P < 0.00001) in the control group. At the end of follow‐up, a virologic SR was seen in 32% (95% CI 21‐46%) of interferon‐treated patients versus only 4% (95% CI 0‐13%, P = 0.00007) of controls. Interferon also improved liver biochemistry to a similar extent. The tolerability of therapy, or the impact of interferon alfa‐2b on hepatic histology, was not reported. Two trials assessed interferon beta in a total 65 patients. The efficacy of interferon beta could not be assessed, however, due to heterogeneity of these trials.

Authors' conclusions

Interferon alfa is effective in improving biochemical outcomes and achieving sustained virologic clearance in patients with transfusion‐acquired acute hepatitis C. The effect on long‐term clinical outcomes could not be assessed due to limitations in the current data.

Plain language summary

Interferon alfa improves liver biochemistry and viral clearance in transfusion‐acquired acute hepatitis C

Acute hepatitis C is rarely diagnosed because in most cases it is asymptomatic. Treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C with interferon can achieve viral clearance and improve liver biochemistry and histology. In this review, treatment with interferon alfa in the acute stage of transfusion‐acquired hepatitis C infection improved liver biochemistry and enhanced viral clearance compared to the natural history of the disease. We cannot ascertain, however, the effect of interferon on clinical outcomes due to a lack of data. Because of the effect of therapy on biochemical and virologic outcomes, we recommend the treatment of acute hepatitis C with at least interferon alfa at a dosage of three million units thrice weekly for three months. Future trials should focus on the efficacy of combination therapy with ribavirin and pegylated interferons, which have shown superiority to interferon alfa in chronic hepatitis C.

Background

Acute HCV infection progresses to chronicity in the majority of patients (Alter 1992; Seeff 2000). In a minority, adverse consequences including hepatocellular carcinoma, the need for liver transplantation, and liver‐related mortality occur (Orland 2001; Lauer 2001). Interferon therapy in patients with chronic HCV infection has proven effective in normalizing liver biochemistry, achieving sustained virologic clearance (Poynard 1996), and improving hepatic histology (Camma 1997), as well as health‐related quality of life (Ware 1999). Multivariate analysis has shown that a sustained response to interferon is independently predicted by a short duration of infection and the absence of cirrhosis (Pagliaro 1994); both are characteristic of acute HCV infection. In order to prevent the progression of acute HCV infection to chronic hepatitis, several studies have assessed interferon in the acute stage. Although results have generally favoured interferon treatment, a statistically significant effect has been difficult to demonstrate potentially due to small sample sizes. The aim of this Review was to assess the impact of interferon in a large sample of patients with acute HCV infection using pooled data from these studies in a meta‐analysis.

Objectives

The objective of this Review was to assess the efficacy of interferon versus placebo or no treatment in patients with acute HCV infection. The main outcome measure was the sustained disappearance of HCV RNA from the serum.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) comparing interferon with placebo or no treatment, and published as an article, abstract, or letter were included. There were no language limitations.

Types of participants

Only RCTs including patients with acute hepatitis C were included. Acute hepatitis C was defined as: 1) serum aminotransferase levels above twice the upper normal value; 2) seroconversion of antibodies to HCV, or the appearance of HCV RNA in serum between two and 24 weeks after blood inoculation; and 3) exclusion of other causes of liver disease. RCTs involving patients post‐liver transplantation, or co‐infected with the hepatitis B virus or human immunodeficiency virus were excluded.

Types of interventions

There was no exclusion for type, dose, or duration of interferon therapy. Only RCTs including placebo or no treatment in a control group were included.

Types of outcome measures

In order to be included, at least one of the following outcome measures had to be reported: normalization of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity at the end of treatment (biochemical ETR); sustained ALT normalization at the end follow‐up (biochemical SR); and disappearance of serum HCV‐RNA by polymerase chain reaction assay (PCR) at the end of treatment (virologic ETR), and at the end of follow‐up (virologic SR). Histologic data and adverse events were also recorded.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched MEDLINE (January 1966 to June 2001), the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, and did manual searches of reference lists, since we have previously demonstrated that the sensitivity of the MEDLINE search alone is inadequate (Poynard 1985). All publications describing (or which might describe) RCTs of interferon treatment versus placebo or no intervention in acute HCV were obtained using the search strategy developed by the Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group (see Review Group details for more information). The following terms were included in the electronic search strategy of MEDLINE and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register: 'acute hepatitis non‐A non‐B, ‐C, clinical trials'. Furthermore, we searched the references of published reviews, hand searched the abstracts of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (1995‐2000), and contacted pharmaceutical companies to obtain unpublished RCTs.

Data collection and analysis

Meta‐analysis was conducted according to a predetermined protocol following the recommendations of Sacks et al. (Sacks 1987). Methodological quality assessment of the trials was performed by two observers independently using a previously validated questionnaire (Poynard 1988). In this questionnaire, 14 items were analysed: description of the primary outcome measure; criteria of inclusion; number of subjects seen and excluded; number of subjects randomised in each group; number of subjects excluded during the follow‐up period; blinding of the doctors, patients, and those responsible for the assessment criteria; a priori sample size calculation; method of randomisation and its concealment; analysis and discussion of covariables; statistical tests used; the number of drop outs; and the power of trials with non‐significant results. The concealment of allocation, important in reducing bias, was also analysed according to the following scale (Kjaergard 2001): adequate (A), unclear (B), inadequate (C), and not used (D) (see the table 'Characteristics of included studies').

Range of patient characteristics, diagnoses, and treatments The following items were recorded as potentially useful in assessing clinical heterogeneity between RCTs: mean age, gender ratio, mean duration of hepatitis, mode of infection, HCV genotype, and type of interferon administered (alfa‐2a, alfa‐2b, beta, etc).

Criteria of combinability RCTs were combined only if the same type of interferon was investigated, and if at least one of the given outcomes was assessed. For each RCT, the exact drug dosage was given, as well as the duration of treatment.

Selection and data‐extraction bias All RCTs considered for inclusion were analysed independently by two observers (TP, TT, RM, or VL), who conferred with one another in case of disagreement. The decision as to inclusion or exclusion of studies was independent of the study results.

Statistical methods RevMan 4.1 (Cochrane Collaboration) and NCSS 2000 (Number Cruncher Statistical Systems, Kaysville, Utah) statistical software were used for all analyses. For the biochemical and virologic outcome measures, all analyses were performed according to the intention‐to‐treat method, that is, they included all randomised patients and patients without the outcome measure were considered treatment failures. When not explicitly reported in the publication, the response rate according to the intention‐to‐treat method was recalculated. Because of a high percentage of patients without a post‐treatment liver biopsy, the percentage of patients with histological improvement was estimated according to a per‐protocol method, that is, after exclusion of missing data which were not considered treatment failures. For each outcome measure, heterogeneity of results between the control groups was assessed using the Peto et al. method (DeMets 1987). Depending on the presence or absence of significant heterogeneity (P < 0.1), drug efficacy was assessed using a random effects model (Der Simonian 1986) or a fixed effects model (DeMets 1987). A significance level of 5% was taken as the alpha risk. Each estimate was reported with its 95% confidence interval (CI). Comparisons between strata were performed using weighted risk differences (WRD). Peto odds ratios are reported in Forrest plots 01.01 to 01.05.

Results

Description of studies

SEARCH RESULTS Eighteen references of interferon therapy in patients with acute hepatitis C were identified. Twelve of these studies were excluded because the trials were uncontrolled (n = 6), non‐randomised (n = 3), or duplicate publications (n = 3). The remaining six trials comprised the core group of our meta‐analysis, compared with four in our previous review (Poynard 1996).

TRIALS ASSESSING INTERFERON ALFA‐2B A total of four trials, published between 1992 and 1994, were analysed (Viladomiu 1992; Li 1993; Hwang 1994; Lampertico 1994). All of the trials assessed interferon alfa‐2b versus an untreated control arm. One of the trials randomised patients to two arms of different interferon doses versus a control arm (Li 1993); the patients receiving interferon in this trial were analysed together. The dose of interferon was three MU in all studies; the frequency of administration ranged from daily (for one week in a single trial) to every other day. The duration of therapy was 12 weeks in all studies. The median duration of follow‐up after the end of treatment was 12 months (range nine to 15 months). The mean age of the included patients was reported in three trials (mean 51 years; standard deviation four years). The proportion of males was reported in all of the trials (mean 62%; range 44 to 75%). All of the patients in these trials acquired their HCV infection via contaminated blood products. The duration of infection was specifically reported in three trials (median eight weeks; range seven to 10 weeks). Two trials reported on virologic parameters at study entry; 74% of the patients in these trials were HCV RNA positive. HCV genotype was reported in only one trial; 54% of patients in this trial were genotype 1.

TRIALS ASSESSING INTERFERON BETA Two trials, published in 1991 and 1998, were analysed (Calleri 1998; Omata 1991). Both of these trials assessed interferon beta at a dosage of three MU daily for five days followed by thrice weekly for three weeks versus an untreated control arm. Follow‐up was for 12 months after the end of treatment in both trials. The mean age of the included patients (mean 34 years; standard deviation six years) and the proportion of males (mean 65%; range 44 to 85%) was reported in both trials. A history of blood transfusion was reported in 5% of patients in one trial versus 80% in the other. In the former trial, 65% of patients gave a history of injection drug use; this was not reported in the other trial. The mean duration of infection was available from neither of the trials, nor was the proportion of HCV genotype 1 infection. HCV RNA positivity at study entry was reported in only one trial; 88% of patients in this trial were HCV RNA positive on entry into the study.

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of the six included trials was graded according to a previously validated method which generates a score ranging from ‐2 to 28 (Poynard 1988). The median scored of the trials assessing interferon alfa‐2b was 11 (range, seven to 13) and the mean +/‐ standard deviation was 10.5 +/‐ 3.0. The median scored of the trials assessing interferon beta was 10 (range, eight to 12) and the mean +/‐ standard deviation was 10.0 +/‐ 2.8. Allocation concealment (Table 2) was not described in any of the trials and none of the trials used blinded reviewers in the assessment of outcomes. In all of the trials, data was analysed according to the intention‐to‐treat method.

1. Grading of the quality of allocation concealment.

| GRADE | ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT |

| A | Adequate: central randomisation, sealed envelopes, or similar. |

| B | Unclear: not described. |

| C | Inadequate: open table of random numbers or similar. |

| D | Not performed: no attempt was made to conceal allocation. |

Effects of interventions

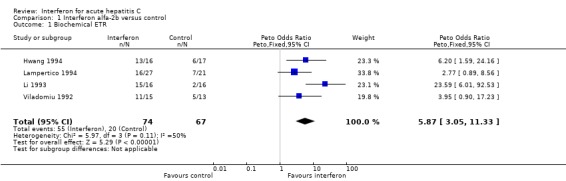

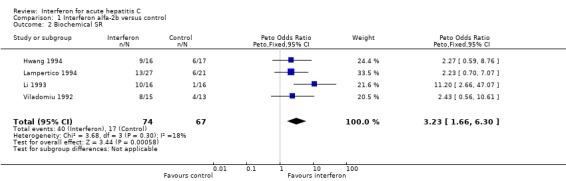

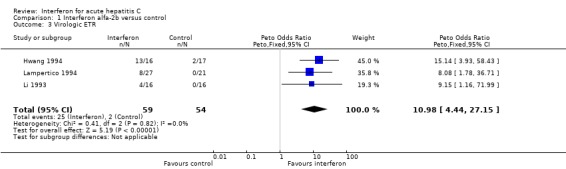

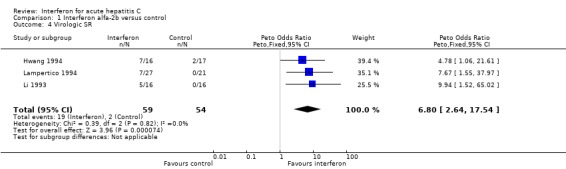

INTERFERON ALFA‐2B (Forrest plots 01.01‐01.04)

‐ Biochemical response Four trials of interferon alfa‐2b in 141 patients with acute HCV infection met the inclusion criteria (Viladomiu 1992; Li 1993; Hwang 1994; Lampertico 1994). There was no significant heterogeneity in any of the outcome measures assessed. Treatment with interferon alfa‐2b was associated with an increase of the biochemical ETR and SR rates by 45% (95% CI 31‐59%, P < 0.00001) and 29% (95% CI 14‐44%, P = 0.0002), respectively, versus no therapy. The rate of biochemical ETR was 74% (95% CI 63‐84%) in the interferon group versus 30% (95% CI 19‐42%, P < 0.00001) in the control group. At the end of follow‐up, a biochemical SR was seen in 54% (95% CI 42‐66%) of interferon‐treated patients versus only 25% (95% CI 15‐37%, P = 0.0006) of controls.

‐ Virological response Interferon alfa‐2b was also associated with an increase in the rates of virologic response, by 40% (95% CI 27‐53%, P < 0.00001) at the end of treatment and 29% (95% CI 16‐43%, P = 0.00002) at the end of follow‐up, when compared with controls. The rate of virologic ETR was 42% (95% CI 30‐56%) in the interferon group versus 4% (95% CI 0‐13%, P < 0.00001) in the control group. At the end of follow‐up, a virologic SR was seen in 32% (95% CI 21‐46%) of interferon‐treated patients versus only 4% (95% CI 0‐13%, P = 0.00007) of controls.

Only one trial assessed the impact of pretreatment patient characteristics on the response to interferon treatment. Using a logistic regression model, Hwang et al. (Hwang 1994) found that only the pretreatment serum HCV RNA level independently influenced the response to treatment (P = 0.035). Patients with a virologic SR had significantly lower levels of HCV RNA than those patients who did not respond to therapy (median 0.44 molecular equivalents/ml versus 13 molecular equivalents/ml, P = 0.02).

‐ Histological response The impact of interferon alfa‐2b on hepatic histology was assessed in only one trial (Viladomiu 1992). Out of 28 patients enrolled in this trial, liver biopsies at 12 months of follow‐up were available in 11 interferon‐treated patients and 10 controls. In general, histologic lesions were more severe in control than treated patients, but differences did not reach statistical significance. In particular, chronic active hepatitis was more frequent in the control group (80% versus 46%, not significant [NS]), whereas minimal histologic changes were more frequent in the interferon group (37% versus 20%, NS). The Knodell score, a validated assessment of the degree of necroinflammatory activity in chronic hepatitis (Knodell 1981), was lower in interferon‐treated patients than controls (5.0 versus 9.2), but the difference did not reach statistical significance.

‐ Clinical response We were unable to identify any data on clinical response in patients randomised to interferon alpha versus placebo/no intervention.

INTERFERON BETA Two RCTs assessing interferon beta in a total of 65 patients with acute hepatitis C met the inclusion criteria (Omata 1991; Calleri 1998). The results of these studies were heterogeneous and thus, could not be submitted to meta‐analysis. Omata et al. (Omata 1991) compared interferon beta three MU intravenously daily for five days followed by three MU thrice weekly for three weeks versus no treatment. Among 11 treated patients, a biochemical ETR was observed in 7 patients (64%, 95% CI 31‐89%) versus only 1/14 controls (7%, 95% CI 0‐34%, P = 0.007). The four patients in the treatment group who failed to normalize their ALT were given a second course of interferon for four weeks (mean total dose 122 MU), and all but one patient achieved a biochemical SR at the end of three years of follow‐up. Including these retreated patients, HCV RNA was undetectable during follow‐up in ten treated patients (91%, 95% CI 59‐100%) versus only one control patient (7%, 95% CI 0‐34% , P = 0.00004), suggesting a benefit of interferon beta in acute hepatitis C. Calleri et al. (Calleri 1998), on the other hand, found no benefit of interferon beta in patients treated with three MU thrice weekly for four weeks. At the end of a median follow‐up of 23 months, 5/20 of the treatment group (25%, 95% CI 9‐49%) had normalized their ALT versus 4/18 controls (22%, 95% CI 6‐48%, NS). There was also no difference in the rate of virologic response between treated and control patients. At the end of follow‐up, HCV RNA remained detectable in 5/8 treated patients (63%, 95% CI 24‐91%) and 11/13 untreated patients (85%, 95% CI 55‐98%, NS) in whom serum samples were available for HCV RNA testing.

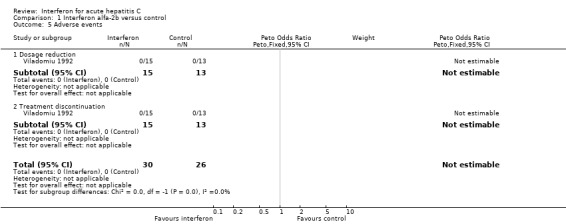

ADVERSE EVENTS (Forrest plot 01.05) None of the interferon alfa‐2b or interferon beta trials reported a comparison of adverse events between interferon‐treated patients and controls. The Viladomiu et al. trial (Viladomiu 1992) did report the frequency of dosage reduction and treatment discontinuation; none of the patients in this study required a reduction in interferon dosage or discontinuation of therapy.

Discussion

This overview identified six published RCTs (Omata 1991; Viladomiu 1992; Li 1993; Hwang 1994; Lampertico 1994; Calleri 1998) compared to only four trials in the previous analysis from our group (Poynard 1996). In acute, transfusion‐acquired hepatitis C, a three month course of interferon alfa had a favourable effect upon the biochemical response at the end of treatment which was sustained during 12 to 15 months of follow‐up. More importantly, there was a major difference in favour of interferon alfa over no treatment for the sustained clearance of HCV RNA from serum, an outcome measure which has proven durable in chronic HCV infection (Marcellin 1997). Results of studies with interferon beta were heterogeneous; thus, we cannot recommend this treatment for acute HCV infection. Data regarding adverse events of treatment was poorly reported. Thus, no conclusions regarding the tolerability of interferon therapy in acute hepatitis C can be made based on these trials.

The impact of pretreatment characteristics such as age, gender, and genotype, factors known to affect the response to interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C (Poynard 2000), could not be assessed due to limitations in the available data. A single study suggested, however, that lower pretreatment levels of HCV RNA predicted a favourable response to interferon alfa‐2b treatment (Hwang 1994). Similar findings have been reported in untreated patients with acute HCV infection, in whom spontaneous viral clearance is more likely in patients with lower peak viral titers (Villano 1999), and may relate to the evolution of HCV quasi‐species (Farci 2000). An important question to address in assessing the efficacy of interferon in acute hepatitis C is whether or not this treatment improves the long‐term outcome of the disease. We have limited information on the impact of treatment on hepatic histology, and no data regarding its effect on long‐term clinical outcomes. In a disease which sequelae generally require decades to manifest (Seeff 1997; Seeff 2000), we cannot assume that an earlier clearance of the virus will translate into less end stage liver disease since 'successfully‐treated' patients may have spontaneously cleared the virus in the absence of treatment had they been followed for a longer period. Indeed, some evidence suggests that patients with clinically overt acute HCV infection, the minority (< 25%), but those most likely to seek medical attention and thereby receive treatment, are more likely to spontaneously clear their infection (Giuberti 1994; Villano 1999). Alternatively, in the event of viral persistence, these patients may have proven to be 'slow‐progressors', and failed to manifest any adverse sequelae of chronic HCV infection, including the requirement for liver transplantation or liver‐related death.

Recognizing these unanswered questions, if the goal of the patient with acute hepatitis C and his/her physician is a greater chance of clearance of HCV RNA from the serum during the short‐term, we recommend treatment with at least interferon alfa at a dosage of three MU thrice weekly for three months. In view of the durability of virologic response observed in the included trials, as well as those of interferon treatment in chronic hepatitis C (Marcellin 1997), we expect this benefit to be long‐lasting in the absence of reinfection. Several practical questions remain, however, which must be studied in future trials. First, the optimal timing for institution of therapy is unclear. In general, the patients in this Review were treated very early in the course of their infection, usually within three months of transfusion once symptoms had arisen. It may be preferable to institute therapy immediately after exposure, for example in healthcare workers with percutaneous injuries, in order to abort potential HCV infection. Although case studies have claimed benefit from post‐exposure prophylaxis, large scale studies have not been completed (Orland 2001). Alternatively, later treatment may be preferable in order to avoid unnecessary treatment with expensive and potentially harmful therapy in the group who would have spontaneously cleared the virus (see below). This expectant approach risks, however, missing a window of opportunity in which the response to treatment appears enhanced. In our meta‐analysis, the response to only 12 weeks of interferon monotherapy in patients with acute hepatitis C was similar to that previously observed with 24 weeks of interferon and ribavirin combination therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C (McHutchison 1998; Poynard 1998). Currently, there is no compelling evidence supporting other doses or durations of interferon monotherapy in acute hepatitis C. Similarly, combination therapy with ribavirin or the use of pegylated interferons has not been studied in acute hepatitis C. However, the major benefit of these medications in achieving a sustained virologic response in chronic hepatitis C in comparison to the 'old' non‐pegylated interferon monotherapy regimen (McHutchison 1998; Poynard 1998; Zeuzem 2001) warrants their assessment in the acute setting. Finally, the cost‐effectiveness of interferon therapy in acute hepatitis C should be formally evaluated.

We observed a four per cent rate of viral clearance at the end of follow‐up in the untreated control group. This is relatively low in comparison with the 25 per cent rate of ALT normalization at this time, as well as existing literature which suggests that 15‐25 per cent of patients spontaneously clear the virus (Alter 1992, Seeff 2000). It is possible that prior studies have overestimated the rate of virologic clearance in untreated patients. Alternatively, and perhaps more likely, spontaneous clearance of HCV may occur later in the course of infection, and would be more likely seen on longer follow‐up. Indeed, in a study of 43 injection drug users, who seroconverted to HCV‐positivity during extended follow‐up, Villano et al. reported spontaneous viral clearance in six patients (14%) at a median of 19 months (range 14 to 45 months) after seroconversion (Villano 1999).

Our Review has several weaknesses, particularly the small number of trials and patients included. RCTs are very difficult to perform in acute HCV infection because this condition is rarely clinically identified (Alter 1992). Furthermore, the incidence of post‐transfusion hepatitis has declined dramatically since the widespread application of highly sensitive serologic screening tests for HCV (Donahue 1992; Armstrong 2000). Another potential weakness of this Review is the heterogeneity of the included RCTs for such variables as race, timing and method of diagnosis of acute hepatitis C, and type and dosage of interferon studied. When trials assessing interferon alfa‐2b were analysed separately, however, all studies individually showed at least a trend towards improved outcomes in the treated patients. Pooling of the data using meta‐analysis, these differences became statistically significant. Another possible weakness of this Review is the potential inclusion of patients with chronic hepatitis C in the absence of pre‐transfusion HCV RNA testing in all patients. This possibility is effectively ruled out, however, by the 25 per cent rate of sustained biochemical response observed in the control group, a rate which has not been duplicated in previous trials in chronic hepatitis C patients (Davis 1989; Thevenot 2001).

Finally, our Review has a substantial overrepresentation of transfusion‐acquired acute hepatitis C which potentially limits its generalizability. In fact, in the trials assessing interferon alfa‐2b, all of the patients acquired HCV infection via contaminated blood products. As mentioned previously, the incidence of post‐transfusion hepatitis C has fallen markedly such that the majority of cases seen in current clinical practice are acquired via injection drug use, occupationally, or sporadically. These patients, particularly intravenous drug abusers, may be less likely than those with transfusion‐acquired acute hepatitis C to seek medical attention and receive treatment in the event of an acute icteric illness. Furthermore, the natural history of HCV infection may be different in these patients (Seeff 1997; Poynard 2001), and they may respond differently to interferon treatment in the setting of acute infection. These questions can only be answered by future trials.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In conclusion, this Review confirms the efficacy of interferon alfa on biochemical and virologic outcomes in transfusion‐acquired acute hepatitis C. No data are available on the long‐term efficacy of interferon alfa on the outcomes of this disease, nor the response in patients with acute hepatitis C acquired via other means.

Implications for research.

In the future, the combination of ribavirin with interferon, including the newer pegylated formulations, as well as the optimal timing, doses, and duration of therapy, should be tested in the setting of acute hepatitis C. Response rates in patients with acute hepatitis C acquired via means other than transfusion should also be assessed.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD000369 'Interferon for acute hepatitis C'.

Erratum regarding listing of authors in MEDLINE. In stead of: Poynard T, Regimbeau C, Myers RP, Thevenot T, Leroy V, Mathurin P, Opolon P, Zarski JP it should be: Myers RP, Regimbeau C, Thevenot T, Leroy V, Mathurin P, Opolon P, Zarski JP, Poynard T.

Acknowledgements

R.P. Myers is supported by the Dr. V. Feinman Hepatology Fellowship from the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver and the Detweiler Traveling Fellowship from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. T. Thevenot had a grant from Recherche et Partage, and C. Regimbeau from Association Française pour l'Etude du Foie and Club Francophone de l'Hypertension Portale. The authors would like to acknowledge Drs. Christian Gluud and Ronald Koretz for their helpful editorial suggestions regarding the manuscript.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Interferon alfa‐2b versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Biochemical ETR | 4 | 141 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.87 [3.05, 11.33] |

| 2 Biochemical SR | 4 | 141 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.23 [1.66, 6.30] |

| 3 Virologic ETR | 3 | 113 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 10.98 [4.44, 27.15] |

| 4 Virologic SR | 3 | 113 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.80 [2.64, 17.54] |

| 5 Adverse events | 1 | 56 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.1 Dosage reduction | 1 | 28 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.2 Treatment discontinuation | 1 | 28 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Interferon alfa‐2b versus control, Outcome 1 Biochemical ETR.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Interferon alfa‐2b versus control, Outcome 2 Biochemical SR.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Interferon alfa‐2b versus control, Outcome 3 Virologic ETR.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Interferon alfa‐2b versus control, Outcome 4 Virologic SR.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Interferon alfa‐2b versus control, Outcome 5 Adverse events.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Calleri 1998.

| Methods | Randomisation: yes Blinding: no Intention to treat: yes Methodological score: 8 | |

| Participants | ‐ Patients with acute hepatitis C ‐ n = 40 ‐ Arms (IFN/C): 20/20 ‐ RNA + at entry: no data available (NDA) ‐ Excluded: 0/0 ‐ Mean age (y): 29/29 ‐ Male (%): 85/85 ‐ Transfusion (%): 5/5 ‐ Drug abuse (%): 65/65 ‐ Genotype: NDA ‐ Mean disease duration (wk): NDA | |

| Interventions | ‐ Schedule: Control: no intervention Experimental: IFN beta 3 MU/day x 5 d; 3 MU tiw x 3 wk ‐Follow‐up (F/U): 22 mo | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Biochemical ETR and SR | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hwang 1994.

| Methods | Randomisation: yes Blinding: no Intention to treat: yes Methodological score: 13 | |

| Participants | ‐ Patients with acute hepatitis C ‐ n = 33 ‐ Arms (IFN/C): 16/17 ‐ RNA + at entry: 16/17 ‐ Excluded: 0/1 ‐ Mean age (y): 53/55 ‐ Male (%): 75/71 ‐ Transfusion (%): 100/100 ‐ Drug abuse (%): 0/0 ‐ Genotype: G1 54%, G2 30%, Other 15% ‐ Mean disease duration (wk): 9/10 | |

| Interventions | ‐ Schedule: Control: no intervention Experimental: IFN alpha‐2b 3 MU tiw x 3 mo ‐F/U: 12 mo | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Biochemical ETR and SR ‐ Virologic ETR and SR | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lampertico 1994.

| Methods | Randomisation: yes Blinding: no Intention to treat: no Methodological score: 13 | |

| Participants | ‐ Patients with acute hepatitis C ‐ n = 48 ‐ Arms (IFN/C): 27/21 ‐ RNA + at entry: 18/9 ‐ Excluded: 1/2 ‐ Mean age (y): 49/44 ‐ Male (%): 65/47 ‐ Transfusion (%): 100/100 ‐ Drug abuse (%): 0/0 ‐ Genotype: NDA ‐ Mean disease duration (wk): 7/9 | |

| Interventions | ‐ Schedule: Control: no intervention Experimental: IFN alpha‐2b 3 MU tiw x 3 mo ‐ F/U: 15 mo | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Biochemical ETR and SR ‐ Virologic ETR and SR | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Li 1993.

| Methods | Randomisation: yes Blinding: no Intention to treat: yes Methodological score: 9 | |

| Participants | ‐ Patients with acute hepatitis C ‐ n = 32 ‐ Arms (IFN/IFN/C) : 8/8/16 ‐ RNA + at entry: NDA ‐ Excluded: 5 (IFN/IFN) / 2 ‐ Mean age (y): NDA ‐ Male (%): 44 (IFN/IFN) / 60 ‐ Transfusion (%): 100/100/100 ‐ Drug abuse (%): 0/0/0 ‐ Genotype: NDA ‐ Mean disease duration (mo): 3‐6 | |

| Interventions | ‐ Schedule: Control: no intervention Experimental: ‐ Group A: IFN alpha‐2b 3 MU/d x 1 wk; 3 MU/2d x 11 wk ‐ Group B: IFN alpha‐2b 3 MU/2d x 12 wk ‐ F/U: 12 mo | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Biochemical ETR and SR ‐ Virologic ETR and SR | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Omata 1991.

| Methods | Randomisation: yes Blinding: no Intention to treat: yes Methodological score: 12 | |

| Participants | ‐ Patients with acute hepatitis C ‐ n = 25 ‐ Arms (IFN/C): 11/14 ‐ RNA + at entry: 10/12 ‐ Excluded: 0/0 ‐ Mean age (y): 40/38 ‐ Male (%): 44/50 ‐ Transfusion (%): 88/71 ‐ Drug abuse (%): NDA ‐ Genotype: NDA ‐ Mean disease duration: NDA | |

| Interventions | ‐ Schedule: Control: no intervention Experimental: IFN beta 3 MU/d x 5 days; 3 MU tiw x 3 wk ‐ F/U: 12 mo | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Biochemical ETR ‐ Virologic ETR | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Viladomiu 1992.

| Methods | Randomisation: yes Blinding: no Intention to treat: yes Methodological score: 7 | |

| Participants | ‐ Patients with acute hepatitis C ‐ n = 28 ‐ Arms (IFN/C): 15/13 ‐ RNA + at entry: NDA ‐ Excluded: 0/0 ‐ Mean age (y): 54/51 ‐ Male (%): 60/70 ‐ Transfusion (%): 100/100 ‐ Drug abuse (%) : 0/0 ‐ Genotype: NDA ‐ Mean disease duration (wk): 7/7 | |

| Interventions | ‐ Schedule: Control: no intervention Experimental: IFN alpha‐2b 3 MU tiw x 3 mo ‐ F/U: 9 mo | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Biochemical ETR and SR ‐ Liver histology ‐ Adverse events | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

C: control IFN: interferon NDA: no data available. ETR: end of treatment response. SR: sustained response. wk: weeks mo: months y: years MU: million units tiw: three times weekly

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Alberti 1994 | Controlled, but non‐randomised trial. |

| Colombo 1993 | Duplicate publication (Lampertico 1994). |

| Fukui 1994 | No untreated control group. |

| Genesca 1992 | Duplicate publication (Viladomiu 1992). |

| Lee 1996 | No untreated control group. |

| Ohnishi 1989 | No untreated control group. |

| Ohnishi 1991 | Controlled, but non‐randomised trial. |

| Omata 1994 | Duplicate publication (Omata 1991). |

| Palmovic 1994 | No untreated control group. |

| Takano 1994 | No untreated control group. |

| Tassopoulos 1993 | Controlled, but non‐randomised trial. |

| Vogel 1996 | No untreated control group. |

Contributions of authors

TP, TT, CR, PM, VL, PO, JPZ wrote the first draft of the protocol and the review. TP, TT, and VL performed the literature searches, and participated in the selection of trials and data extraction. TP and TT performed the statistical analyses. RM performed an updated literature search; verified the data extraction and statistical analyses; and rewrote the review in light of the suggestions of the reviewers. TP and CR approved the final version of the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver, Canada.

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, Canada.

Association Francaise pour l'Etude du Foie, France.

Club Francophone de l'Hypertension Portale, France.

Recherche et Partage, France.

Declarations of interest

The authors have no permanent financial contracts with companies producing interferon. T. Poynard, P. Opolon, and J.P. Zarski have been involved in prospective studies sponsored by Schering Plough, Roche, Glaxo Welcome, and AMGEN.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Calleri 1998 {published data only}

- Calleri G, Colombatto P, Gozzelino M, Chieppa F, Romano P, Delmastro B, et al. Natural beta interferon in acute type‐C hepatitis patients: a randomized controlled trial. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998;30(2):181‐4. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hwang 1994 {published data only}

- Hwang SJ, Lee SD, Chan CY, Lu RH, Lo KJ. A randomized controlled trial of recombinant interferon alpha‐2b in the treatment of Chinese patients with acute post‐transfusion hepatitis C. J Hepatol 1994;21(5):831‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lampertico 1994 {published data only}

- Lampertico P, Rumi M, Romeo R, Craxi A, Soffredini R, Biassoni D, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of recombinant interferon‐alpha 2b in patients with acute transfusion‐associated hepatitis C. Hepatology 1994;19(1):19‐22. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Li 1993 {published data only}

- Li XW, Zhu ZY, Dao WP, Liu FH, Die GS. A report on therapy of interferon alfa 2b in patients with acute hepatitis C. Chung Hua Nei Ko Tsa Chih 1993;32(6):409‐11. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Omata 1991 {published data only}

- Omata M, Yokosuka O, Takano S, Kato N, Hosoda K, Imazeki F, et al. Resolution of acute hepatitis C after therapy with natural beta interferon. Lancet 1991;338(8772):914‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Viladomiu 1992 {published data only}

- Viladomiu L, Genesca J, Esteban JI, Allende H, Gonzalez A, Lopez‐Talavera JC, et al. Interferon‐alpha in acute posttransfusion hepatitis C: a randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology 1992;15(5):767‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Alberti 1994 {published data only}

- Alberti A, Chemello L, Belussi F, Pontisso P, Tisminetzky S, Gerotto M, et al. Outcome of acute hepatitis C and role of alpha interferon therapy. In: Nishioka KSH, Oda T editor(s). Viral Hepatitis and Liver Disease. Tokyo, Japan: Springer‐Verlag, 1994:604‐6. [Google Scholar]

Colombo 1993 {published data only}

- Colombo M, Lampertico P, Rumi M. Multicentre randomised controlled trial of recombinant interferon alfa‐2b in patients with acute non‐A, non‐B/type C hepatitis after transfusion. Gut 1993;34(2 Suppl):S141. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fukui 1994 {published data only}

- Fukui S, Tohyama H, Iwabuchi S. Interferon therapy for acute hepatitis C; changes in serum markers associated with HCV and clinical effects. Nippon Rinsho 1994;52(7):1847‐51. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Genesca 1992 {published data only}

- Genesca J. Interferon alfa in acute posttransfusion hepatitis C: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastroenterology 1992;103(5):1702‐3. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 1996 {published data only}

- Lee WM, Shiffman ML, Gnann Jr. JW, Samanta A, Alam J. A trial of interferon therapy beta 1a for 4 weeks for therapy of acute hepatitis C (Abstract). Hepatology 1996;24(4 Pt. 2):275A. [Google Scholar]

Ohnishi 1989 {published data only}

- Ohnishi K, Nomura F, Iida S. Treatment of posttransfusion non‐A, non‐B acute and chronic hepatitis with human fibroblast beta‐interferon: a preliminary report. Am J Gastroenterol 1989;84(6):596‐600. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ohnishi 1991 {published data only}

- Ohnishi K, Nomura F, Nakano M. Interferon therapy for acute posttransfusion non‐A, non‐B hepatitis: response with respect to anti‐hepatitis C virus antibody status. Am J Gastroenterol 1991;86(8):1041‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Omata 1994 {published data only}

- Omata M, Takano S. A randomized, controlled trial of interferon‐beta treatment for acute hepatitis C. Viral Hepatitis and Liver Disease 1994:601‐3. [Google Scholar]

Palmovic 1994 {published data only}

- Palmovic D, Kurelac I, Crnjakovic‐Palmovic J. The treatment of acute post‐transfusion hepatitis C with recombinant interferon‐alpha. Infection 1994;22(3):222‐3. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Takano 1994 {published data only}

- Takano S, Satomura Y, Omata M. Effects of interferon beta on non‐A, non‐B acute hepatitis: a prospective, randomized, controlled‐dose study. Japan Acute Hepatitis Cooperative Study Group. Gastroenterology 1994;107(3):805‐11. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tassopoulos 1993 {published data only}

- Tassopoulos NC, Koutelou MG, Papatheodoridis G, Polychronaki H, Delladetsima I, Giannikakis T, et al. Recombinant human interferon alfa‐2b treatment for acute non‐A, non‐B hepatitis. Gut 1993;34(2):S130‐2. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vogel 1996 {published data only}

- Vogel W, Graziadei I, Umlauft F, Datz C, Hackl F, Allinger S, Grunewald K, Patsch J. High dose interferon alpha 2b treatment prevents chronicity in acute hepatitis C. A pilot study. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41(12 Suppl):81S‐85S. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Alter 1992

- Alter MJ, Margolis HS, Krawczynski K, Judson FN, Mares A, Alexander WJ, et al. The natural history of community‐acquired hepatitis C in the United States. The Sentinel Counties Chronic non‐A, non‐B Hepatitis Study Team. N Engl J Med 1992;327(27):1899‐1905. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Armstrong 2000

- Armstrong GL, Alter MJ, McQuillan GM, Margolis HS. The past incidence of hepatitis C virus infection: implications for the future burden of chronic liver disease in the United States. Hepatology 2000;31(3):777‐82. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Camma 1996

- Camma C, Almasio P, Craxi A. Interferon as treatment for acute hepatitis C. A meta‐analysis. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41(6):1248‐55. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Camma 1997

- Camma C, Giunta M, Linea C, Pagliaro L. The effect of interferon on the liver in chronic hepatitis C: a quantitative evaluation of histology by meta‐analysis. J Hepatol 1997;26(6):1187‐99. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Davis 1989

- Davis GL, Balart LA, Schiff ER, Lindsay K, Bodenheimer HC Jr, Perrillo RP, et al. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C with recombinant interferon alfa. A multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med 1989;321(22):1501‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DeMets 1987

- DeMets DL. Methods of combining randomized clinical trials: strengths and limitations. Stat Med 1987;6(3):341‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Der Simonian 1986

- Simonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clin Trials 1986;7:177‐88. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Donahue 1992

- Donahue JG, Munoz A, Ness PM, Brown DE Jr, Yawn DH, McAllister HA Jr, et al. The declining risk of post‐transfusion hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 1992;327(6):369‐73. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Farci 2000

- Farci P, Shimoda A, Coiana A, Diaz G, Peddis G, Melpolder JC, et al. The outcome of acute hepatitis C predicted by the evolution of the viral quasispecies. Science 2000;288(5464):339‐44. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Giuberti 1994

- Giuberti T, Marin MG, Ferrari C, Marchelli S, Schianchi C, Degli Antoni AM, et al. Hepatitis C viremia following clinical resolution of acute hepatitis C. J Hepatol 1994;20(5):666‐71. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kjaergard 2001

- Kjaergard LL, Villumsen J, Gluud C. Reported methodological quality and discrepancies between small and large randomized trials in meta‐analyses. Ann Intern Med 2001;135(11):982‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Knodell 1981

- Knodell RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, Chen TS, Craig R, Kaplowitz N, Kiernan TW, Wollman J. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology 1981;1(5):431‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lauer 2001

- Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2001;345(1):41‐52. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marcellin 1997

- Marcellin P, Boyer N, Gervais A, Martinot M, Pouteau M, Castelnau C, et al. Long‐term histologic improvement and loss of detectable intrahepatic HCV RNA in patients with chronic hepatitis C and sustained response to interferon‐alpha therapy. Ann Intern Med 1997;127(10):875‐81. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McHutchison 1998

- McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, Rustgi VK, et al. Interferon alfa‐2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med 1998;339(21):1485‐92. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Orland 2001

- Orland JR, Wright TL, Cooper S. Acute hepatitis C. Hepatology 2001;33(2):321‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pagliaro 1994

- Pagliaro L, Craxi A, Camma C, Tine F, Marco V, Lo Iacono O, et al. Interferon‐alpha for chronic hepatitis C: an analysis of pretreatment clinical predictors of response. Hepatology 1994;19(4):820‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Poynard 1985

- Poynard T, Conn HO. The retrieval of randomized clinical trials in liver disease from the medical literature. A comparison of MEDLARS and manual methods. Controlled Clin Trial 1985;6(4):271‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Poynard 1988

- Poynard T. Evaluation of the methodological quality of randomized therapeutic trials [Evaluation de la qualité méthodologique des essais thérapeutiques randomisés]. Presse Med 1988;17:315‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Poynard 1996

- Poynard T, Leroy V, Cohard M, Thevenot T, Mathurin P, Opolon P, et al. Meta‐analysis of interferon randomized trials in the treatment of viral hepatitis C: effect of dose and duration. Hepatology 1996;24(4):778‐89. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Poynard 1998

- Poynard T, Marcellin P, Lee SS, Niederau C, Minuk GS, Ideo G, et al. Randomised trial of interferon alpha2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon alpha2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group (IHIT). Lancet 1998;352(9138):1426‐32. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Poynard 2000

- Poynard T, McHutchison J, Goodman Z, Ling MH, Albrecht J. Is an "a la carte" combination interferon alfa‐2b plus ribavirin regimen possible for the first line treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C? The ALGOVIRC Project Group. Hepatology 2000;31(1):211‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Poynard 2001

- Poynard T, Ratziu V, Charlotte F, Goodman Z, McHutchison J, Albrecht J. Rates and risk factors of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2001;34(5):730‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Quin 1997

- Quin JW. Interferon therapy for aute hepatitis C viral infection ‐ a review by meta‐analysis. Aust NZ J Med 1997;27(5):611‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sacks 1987

- Sacks HS, Berrier J, Reitman D, Ancona‐Berk VA, Chalmers TC. Meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. N Engl J Med 1987;316(8):450‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seeff 1997

- Seeff LB. Natural history of hepatitis C. Hepatology 1997;26(3 Suppl 1):21S‐8S. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seeff 2000

- Seeff LB, Miller RN, Rabkin CS, Buskell‐Bales Z, Straley‐Eason KD, Smoak BL, et al. 45‐year follow‐up of hepatitis C virus infection in healthy young adults. Ann Intern Med 2000;132(2):105‐11. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thevenot 2001

- Thevenot T, Regimbeau C, Ratziu V, Leroy V, Opolon P, Poynard T. Meta‐analysis of interferon randomized trials in the treatment of viral hepatitis C in naive patients: 1999 update. J Viral Hepat 2001;8(1):48‐62. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tine 1991

- Tine F, Magrin S, Craxi A, Pagliaro L. Interferon for non‐A, non‐B chronic hepatitis. A meta‐analysis of randomised clinical trials. J Hepatol 1991;13(2):192‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Villano 1999

- Vilano SA, Vlahov D, Nelson KE, Cohn S, Thomas DL. Persistence of viremia and the importance of long‐term follow‐up after acute hepatitis C infection. Hepatology 1999;29(3):908‐14. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vogel 1999

- Vogel W. Treatment of acute hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 1999;31(Suppl 1):189‐92. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ware 1999

- Ware JE Jr, Bayliss MS, Mannocchia M, Davis GL. Health‐related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C: impact of disease and treatment response. The Interventional Therapy Group. Hepatology 1999;30(2):550‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zeuzem 2001

- Zeuzem S, Feinman SV, Rasenack J, Heathcote EJ, Lai MY, Gane E, et al. Peginterferon alfa‐2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 2001;343(23):1666‐72. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Thevenot 2001a

- Thevenot T, Regimbeau C, Ratziu V, Leroy V, Opolon P, Poynard T. Meta‐analysis of interferon randomized trials in the treatment of viral hepatitis C in naive patients: 1999 update. J Viral Hepat 2001;8(1):48‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]