Abstract

Background

Breast reconstruction is achieved through a series of surgical procedures often concluded with nipple-areolar reconstruction tattoo. The purpose of the tattoo is to increase the patients' satisfaction with the appearance of the breast, however, no published studies quantitatively compare patient satisfaction before vs. after tattoo. In recent times nurse practitioners are increasingly performing this specialised procedure previously undertaken by the plastic surgeon, but there is no evidence to compare patient satisfaction according to clinician.

Purpose

The objectives of this study are to examine patient satisfaction pre- and post-nipple-areolar tattooing utilising a validated patient-reported outcome measure the BREAST-Q, and to identify any differences in patient satisfaction between the nurse practitioner and plastic surgeon.

Methods

Data was collected from all breast reconstruction patients who underwent nipple-areolar reconstruction tattooing over a six-year period in a dedicated Breast Reconstruction Unit and had completed a pre- and post-tattoo BREAST- Q questionnaire. Analysis of data included paired t-test of pre- and post-tattoo scores and ANCOVA to compare clinicians and tattoo laterality.

Results

93 patients with completed pre- and post-tattoo questionnaires within the date criteria were included from the 204 patientswho had a nipple-areolar tattoo. There was a significant improvement in patient satisfaction with nipple reconstruction from pre-tattoo (m = 74.4) to post-tattoo (m = 81.0), p = 0.013 (2-tailed), with no significant difference between clinicians.

Conclusion

Patients reported through completion of the BREAST-Q, that nipple-areolar tattooing significantly improves satisfaction with their nipple reconstruction.

Keywords: BREAST-Q, Patient-reported outcomes measure, Breast reconstruction, Nipple-areolar reconstruction tattooing

Introduction

Breast reconstruction is important for physical and psychosocial well-being in women undergoing mastectomy and treatment for breast cancer.1 This is generally achieved through a series of multiple surgical procedures, commencing with creation of a breast mound, followed by additional procedures to refine the mound shape, correct contralateral breast asymmetry and reconstruct the nipple-areolar complex.

The final stage of breast reconstruction is often micropigmentation or tattooing of the reconstructed nipple-areolar complex, a procedure initially described by Rees (1975)2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and traditionally performed by the plastic surgeon. A number of qualitative studies suggest that tattooing of the nipple-areolar reconstruction (NAR) enhances patient satisfaction with their breast reconstruction1, 5, 6, 7, 8 but there are no quantitative studies using a validated patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) in this area.

In the Flinders Medical Centre (FMC) Breast Reconstructive Service in Adelaide, South Australia, a breast reconstruction nurse practitioner established a nurse-led NAR tattoo service in 2012. Prior to the introduction of this role, this procedure was undertaken by a single consultant plastic surgeon. There are some published studies on the introduction of specialist nurse-led tattoo services,5, 9, 10, 11 however, there has been no quantitative study comparing patient-reported outcomes of tattooing between specialist nurses and surgeons. Ongoing monitoring and recording of patient-reported outcomes can provide evidence to evaluate standards of practice and be utilised as a ‘key performance indicator’ for professional efficacy. This is relevant in an era where nurse practitioners are increasingly performing procedures traditionally within the surgeons' domain.

The purpose of the study was to quantitatively assess differences in patient-reported outcomes pre- and post-NAR tattooing, and to identify whether outcomes were consistent between the nurse practitioner and plastic surgeon.

Methods

Population

All patients who attended the FMC Breast Reconstruction Service were asked to complete the BREAST-Q (Reconstruction Module) Patient Reported Outcome Measure (PROM)12 at various points throughout their treatment and consented to storage of their data into a Microsoft Access (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) database. All patients identified from the database as having completed their breast reconstruction with a NAR tattoo between August 2010 and August 2016 were considered for inclusion into this study. Data was gathered prospectively from patients who had completed a questionnaire ≤ six weeks pre-tattoo and ≥ two weeks post-tattoo between July 2011 and August 2016.

These timeframes were established to provide the most accurate score of patient satisfaction related to this procedure and reduce the possibility of bias that may have related to previous stages of the breast reconstruction and the post-tattoo healing phase (see Figure 1). The mean pre-tattoo scores of patients who completed the questionnaires outside of the key time points were also compared to those within the study criteria. Ethics Approval was obtained for this study (Southern Adelaide Clinical Human Research Ethics Committee approval number 354.13) and the Access database was stored securely with password protection on the hospital server.

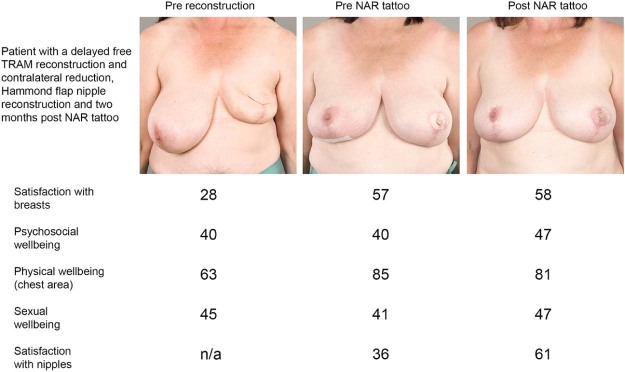

Figure 1.

Example of patient progressive breast reconstruction clinical photographs and BREAST-Q scores aligned to the pre-operative; post-Stage 1; pre- and post-nipple-areolar tattoo stages of reconstruction.

Outcomes measure

The BREAST-Q module specific to breast reconstruction consists of two distinct domains related to patient satisfaction and health related quality-of-life outcomes. These domains contain six sub-domains in physical, psychosocial and sexual well-being and patient satisfaction with breasts, surgical outcomes and the process of care. These sub-domains consist of one or more questions (or scales) and the patient responses to these were analysed with Q-Score software program (New York, N.Y.) to generate a domain score ranging from 0 to 100 (where 0 is the minimum score and 100 is the maximum possible score). All domain scores were analysed at the pre- and post-NAR tattoo time points.

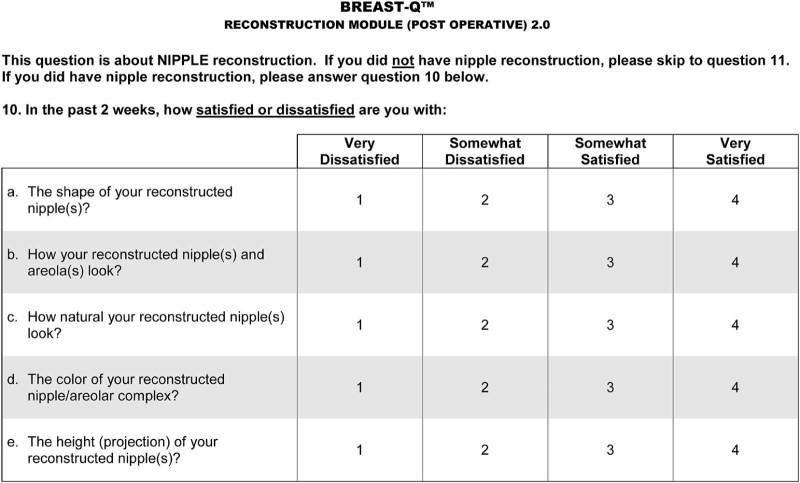

The BREAST-Q “Satisfaction with Nipple” scale questions12 assess patient satisfaction with the shape, natural appearance and projection of the reconstructed nipple and the colour and appearance of the nipple-areolar complex (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Excerpt from the BREAST-Q “Satisfaction with Nipple” scale.

Tattoo method

The tattoo procedure was conducted in the outpatient clinic or, on occasion, in the operating theatre in conjunction with a reconstructive surgical procedure. Each patient was involved in decision-making regarding colour match, size and shape of areolar.

The breast reconstruction nurse practitioner received training and accreditation in nipple-areolar tattooing from the plastic surgeon who established the service, and who had previously conducted the procedure prior to introduction of the role.

A Universal 2000 Rotary Machine (manufacturer So Kit Ching, Taiwan) and 3-point needle was used to implant Academy C Breast Series (manufacturer Cleo Colours, USA) pigment into the skin. All patients were given standardised instructions for post-tattoo care and were reviewed in the Breast Reconstruction Clinic at ≥ two weeks post-tattoo to assess outcome.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics including mean and standard deviation were calculated for demographic characteristics of participants in the study and for continuous BREAST-Q scores.

A paired-sample t-test was conducted to compare means between two dependent groups. A one-way ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) was conducted to determine whether there was any significant difference between two independent groups controlling for baseline BREAST-Q scores as a covariate. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare pre- and post-NAR tattoo question responses. The McNemar test was used to evaluate differences on a dichotomous dependent variable between two related groups. Statistical significance was determined at the p < 0.05 level.

Results

A total of 204 participants had a NAR tattoo within the study time-frame and were included in the study. Of these, 76 were bilateral and 128 were unilateral NAR tattoos, making a total of 280 individual NAR tattoos performed, n = 169 tattoos by the nurse practitioner and n = 111 tattoos by the surgeon. The median patient age was 51 years (range 30–76) and the patients included were 180 who underwent all the stages of a post-mastectomy breast reconstruction in the unit, 15 who were referred only for a NAR tattoo, three revision tattoo patients and six who were having tattoos in the context of other breast surgery (e.g. after complications of bilateral breast reduction). The mean time from first consultation to completion of reconstruction was 18 months (range 5–60 months). A total of 98 of the 204 (48%) patients completed the BREAST-Q within the study time-frames. The remaining 106 patients were excluded from the study for a variety of reasons shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reasons for exclusion from tattoo study.

| Reason for exclusion | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Periodicity of BREAST-Q not yet established | 65 |

| External referral for tattoo only (not followed up at unit) | 17 |

| Developed metastatic cancer | 3 |

| Failed to attend follow-up | 8 |

| No questionnaires completed at all (unknown reason) | 2 |

| Refused to complete questionnaires | 2 |

| Administrative error | 9 |

There were no significant differences between those NAR tattoo patients who were included in the BREAST-Q analysis and those who were not when comparing age, time in months taken to completion of breast reconstruction and pre-NAR tattoo BREAST-Q domain scores.

A total of 98 patients had completed pre- and post-tattoo questionnaires within the study time-frames before and after the NAR tattoo, and, of these, 76 had NAR tattoos performed by the nurse practitioner and 22 had NAR tattoos performed by the surgeon. A paired sample t-test (2-tailed) was used for the comparison between pre-NAR tattoo and post-NAR tattoo BREAST-Q scores. In comparison to scores prior to the NAR tattoo (m = 74.1, SD = 25.4), there was a statistically significant increase in mean BREAST-Q scores following NAR tattoo for “Satisfaction with Nipple” (m = 80.9, SD = 21.0), p = 0.008.

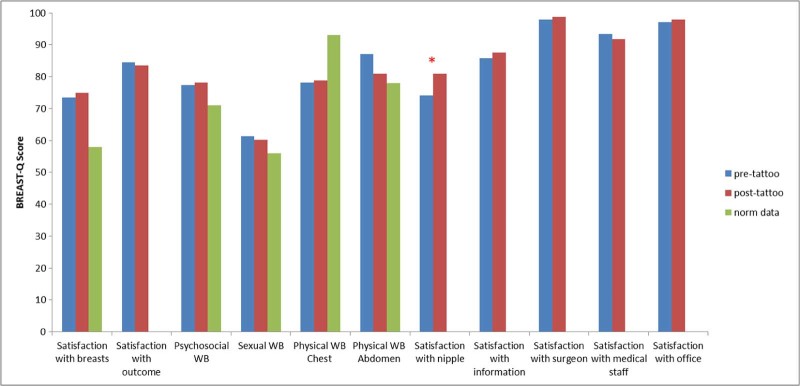

There was no statistically significant improvement in any other BREAST-Q domain between the pre- and post-NAR tattoo, however, when compared to published normative scores in all domains13 the mean post-tattoo scores exceeded published normative mean scores in “Satisfaction with Breast”, “Psychosocial Well-being” and “Sexual Well-being”(Figure 3 and Table 2).

Figure 3.

Mean BREAST-Q Reconstruction Scores: pre- vs. post-NAR Tattoo vs. normative data, n = 98.

Table 2.

BREAST-Q reconstruction module scores (mean ± SD): NAR tattoo participants vs. normative data.12

| Domains | Pre-tattoo | Post-tattoo | Normative data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with breasts | 74 ± 17 | 75 ± 18 | 58 ± 18 |

| Psychosocial well-being | 77 ± 20 | 78 ± 21 | 71 ± 18 |

| Sexual well-being | 61 ± 23 | 60 ± 23 | 56 ± 18 |

| Physical well-being—chest | 78 ± 15 | 79 ± 16 | 93 ± 11 |

| Physical well-being—abdomen | 87 ± 17 | 82 ± 22 | 78 ± 20 |

Using the one-way ANCOVA to compare bilateral and unilateral NAR tattoo patients showed there was a significant effect of laterality on post-tattoo BREAST-Q “Satisfaction with Nipple” scores after controlling for the effect of pre-tattoo BREAST-Q scores, F (1, 77) = 4.17, p = 0.04. Patients who required a unilateral NAR tattoo had a higher adjusted mean “Satisfaction with nipple” score (m = 83.6) when compared to bilateral NAR tattoo patients (m = 75.0).

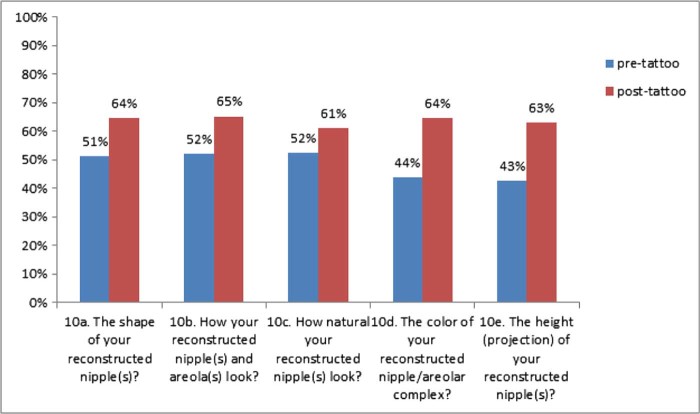

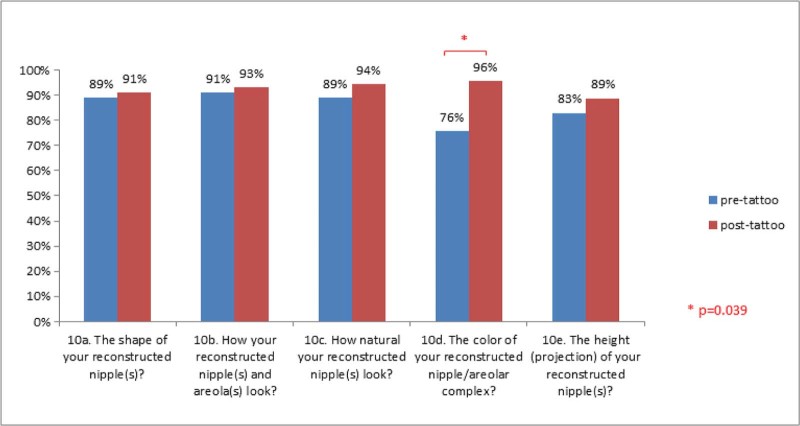

When comparing pre- vs. post-NAR tattoo raw BREAST-Q scores for “Satisfaction with Nipple”, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test looking at the proportion of patients reporting that they were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” showed that the NAR tattoo procedure did not cause a statistically significant change in questions 10a, 10b and 10c, regarding the shape and appearance of the nipple. However, there was an increase in the proportion of patients reporting that they were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with 10d and 10e, regarding the colour and height of the nipple, that were rated significantly higher than pre-NAR tattoo scores, 10d (44% vs. 64%) (Z = −2.27, p = 0.023) and 10e (43% vs. 63%) (Z = −2.292, p = 0.022) (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

“Satisfaction with Nipple” BREAST-Q survey responses: proportion of patients who answered “satisfied” or “very satisfied” pre- and post-tattoo.

When using an exact McNemar test, it was determined that there was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of participants who were “satisfied/very satisfied” with the colour of their reconstructed nipple areolar complex pre- and post-NAR tattoo procedure, p = 0.039, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Comparison of pre-tattoo and post-tattoo responses to nipple sub-domain of BREAST-Q (proportion satisfied/very satisfied).

There was no significant effect of tattooist, nurse (m = 81.5) or surgeon (m = 78.9), on post-tattoo BREAST-Q “Satisfaction with Nipple” scores after controlling for the effect of pre-tattoo BREAST-Q scores, F (1, 77) = 0.084, p = 0.77.

Discussion

In this study, a validated patient-reported outcome measure, the BREAST-Q12 provided quantitative data to illustrate a statistically significant improvement in patient satisfaction following NAR tattoo. Although previous studies using study-specific questionnaires indicated that the NAR tattoo did promote patient satisfaction, none assessed patient satisfaction pre-tattoo and were therefore able to compare results.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 14, 15, 16 The introduction of the BREAST-Q provides greater assurance that this is a genuine finding due to its proven validity and reliability.

An interesting finding from data analysis was that the unilateral NAR tattoo group have a far greater average change in scores post-tattoo vs. the bilateral NAR group. One could hypothesize that this could be explained by the unilateral group having a contralateral breast with a nipple for comparison and may feel more balanced once the tattoo is completed to “match” the other side. This is an area which may warrant further study.

The BREAST-Q has allowed concurrent assessment of patient satisfaction in quality-of-life outcomes in physical, psychosocial and sexual well-being in this study, as illustrated in Figure 3. Whilst Harcourt et al.14 measured levels of anxiety and depression post-nipple reconstruction, these scores were not compared to pre-reconstruction scores to indicate improvement. Other published studies did not review the impact of the NAR tattoo on quality-of-life outcomes,3, 5, 6, 9, 11 with a greater focus placed on satisfaction with aesthetic outcome.

Previous papers describing nurse-led NAR tattoo services, including Potter et al.,4 Clarkson et al.11 and Murray,15 all report high patient satisfaction with NAR outcomes, but have not directly compared the results aligned to the nurse practitioner to those of the surgeon tattooist.4, 11, 15 The results of this quantitative study illustrate equal patient satisfaction with their NAR tattoo performed by either clinician.

This result is similar to conclusions from larger studies that compare nurse practitioners with medical officers in a range of health specialties,17 however, these studies had a greater focus on comparing occasions and financial cost of care, length-of-stay and functionality of services and there was scant quantitative data comparing clinicians in a surgical setting. In addition, there was no reported use of validated PROMS in the collection of data. With the increasing availability of PROMs in many specialties there may be scope for routine use of PROMs to assess service outcomes for quality of care provided by all clinicians.

A limitation of this study is that, although BREAST-Q data was collected prospectively, because the initial purpose of data collection was not to measure the impact of tattooing, more than half of the patient group did not meet the inclusion criteria for this study (mainly due to BREAST-Q administration not meeting appropriate time points). However, analysis of excluded patients did not suggest systematic bias and it is unlikely that the patients in the study were not representatives of the total patient group.

The strength of the study is that it is the first quantitative study of nipple-areolar tattooing with a validated patient-reported outcome measure.

Conclusion

Tattooing of the reconstructed nipple-areolar complex is effective and matters to women undergoing breast reconstruction in terms of improving their satisfaction. This increase in patient satisfaction with their NAR tattoo was shown to be comparable between clinicians, the nurse practitioner and the surgeon, in the provision of this specialised service.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank David Summerhayes, Clinical Photographer, Dept. of Medical Illustration and Media, Flinders Medical Centre.

The authors did not receive any writing assistance.

Footnotes

Parts of this article have been presented at the Leura International Breast Conference, 25–28th October 2016 in the Blue Mountains, New South Wales, Australia.

References

- 1.Wellisch D.K., Schain W.S., Noone R.B., Little J.W., 3rd. The psychological contribution of nipple addition in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:699–704. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198711000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rees T.D. Reconstruction of the breast areola by intradermal tattooing and transfer. Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;55:620–621. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197505000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Ali K., Dalal M., Kat C.C. Tattooing of the nipple-areola complex: review of outcome in 40 patients. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg : JPRAS. 2006;59:1052–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potter S., Barker J., Willoughby L., Perrott E., Cawthorn S.J., Sahu A.K. Patient satisfaction and time-saving implications of a nurse-led nipple and areola reconstitution service following breast reconstruction. Breast. 2007;16:293–296. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy A.D.C.F., Potter S.M., Solan J., Kelly J.L., Regan P.J. Patient satisfaction following nipple-areola complex reconstruction and dermal tattooing as an adjunct to autogenous breast reconstruction. Eur J Surg. 2010;33:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean N.R., Neild T., Haynes J., Goddard C., Cooter R.D. Fading of nipple-areolar reconstructions: the last hurdle in breast reconstruction? Br J Plast Surg. 2002;55:574–581. doi: 10.1054/bjps.2002.3920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jabor M.A., Shayani P., Collins D.R., Jr, Karas T., Cohen B.E. Nipple-areola reconstruction: satisfaction and clinical determinants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:457–463. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200208000-00013. discussion 64-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aslam R., Page F., Francis H., Prinsloo D. Does radiotherapy affect tattoo fading in breast reconstruction patients? JPRAS Open. 2015;6:53–55. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goh S.C., Martin N.A., Pandya A.N., Cutress R.I. Patient satisfaction following nipple-areolar complex reconstruction and tattooing. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg : JPRAS. 2011;64:360–363. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann M.D., Mikell A. Nipple-areola tattooing as part of breast reconstruction. Plast Surg Nurs. 2004;24:155–157. doi: 10.1097/00006527-200410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarkson J.H., Tracey A., Eltigani E., Park A. The patient's experience of a nurse-led nipple tattoo service: a successful program in Warwickshire. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg : JPRAS. 2006;59:1058–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pusic A.L., Klassen A.F., Scott A.M., Klok J.A., Cordeiro P.G., Cano S.J. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:345–353. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mundy L.H.K., Klassen A., Pusic A., Kerrigan C. Breast cancer and reconstruction: normative data for interpreting the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;139:1046e–1055e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harcourt D., Russell C., Hughes J., White P., Nduka C., Smith R. Patient satisfaction in relation to nipple reconstruction: the importance of information provision. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray M. Breast care - focus, the shape of things to come. https://www.inmo.ie/tempDocs/BreastReconstruction%20PAGE28-29.pdf

- 16.Stephens M., Hourigan L.F., Appleyard M. Non-physician endoscopists: a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5056. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.5056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horrocks S., Anderson E., Salisbury C. Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. BMJ. 2002;324:819–823. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]