Summary

We describe two cases where autologous amnion grafts were used to cover the neurosurgical repair of myelomeningocele (MMC) and the reconstructive flaps used for the skin defects.

MMC is a severe fetal defect that evolves during embryonic development as a result of the neural tubes failure to close. In postnatal MMC closure, early timing of surgical repair is essential.

We found that a free amnion graft is a viable choice in reconstructive surgery for myelomeningocele and that a multidisciplinary surgical team involving obstetrician, neurosurgeon and plastic surgeon is essential.

Keywords: Myelomeningocele, Amnion, Reconstructive surgical procedures, Surgical flaps, Neurosurgery

Introduction

Myelomeningocele (MMC) is a severe fetal defect that evolves during embryonic development as a result of the neural tubes failure to close.1 When deciding on postnatal MMC closure, timing of the surgical repair is essential in preventing infection and further trauma to the exposed neurological components.2

This case report describes the post-natal surgical treatment of two MMC using amnion grafts to cover the neurosurgical repair. A number of metabolic properties have been demonstrated in amnion grafts after transplantation including growth factor promoting epithelialization and inhibiting fibrosis and scaring as well as anti-inflammatory and anti-bacterial effects.3, 4 Reviewing the current literature, this technique has only been described twice before in the literature.

Case 1

A girl was diagnosed prenatally by ultrasonography at 20 weeks of gestation with a lumbosacral MMC and hydrocephalus.

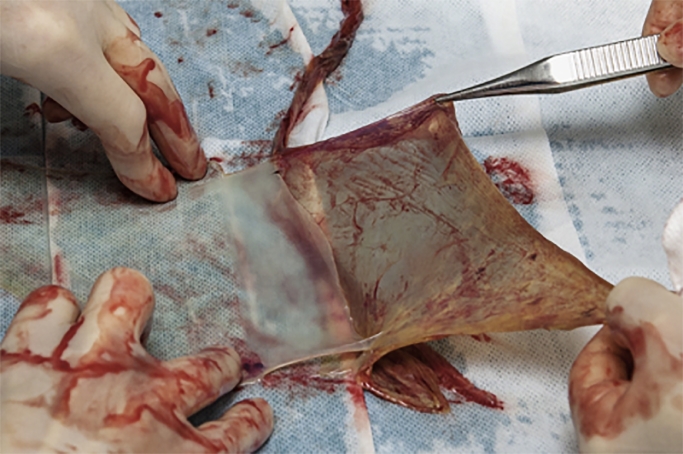

Elective cesarean section was performed at 38+1 weeks of gestation. At delivery, the cele had ruptured, leaking spinal fluid. The placenta and membranes were subsequently removed from the uterus as gentle and sterile as possible, and placed in a sterile environment. The amnion was gently separated from the chorion, wrapped in sterile gauzes and stored in a bicarbonate-buffered culture medium, designed for use in vitro fertilization procedures for culture of embryos at +4 degrees Celsius until surgery, Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The separation of amnion and chorion.

The following morning, the repair of the MMC was performed under general anesthesia in a multidisciplinary setting, with neuro- and plastic surgeons. Initially, a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt was inserted, then a layered closure was performed of the MMC. Under microscopic magnification the neural placode was carefully dissected and sutured; after this, dural remnants were released and sutured together and dysplastic meninges were excised.

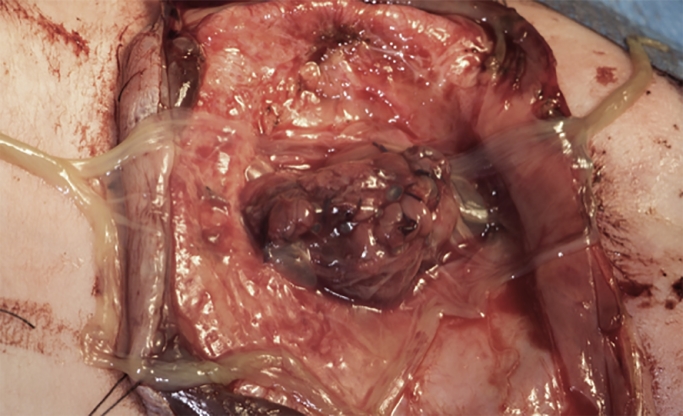

The autologous amniotic membrane graft was draped over the sutured dura defect and fastened with resorbable sutures, Figure 2. A thoracolumbar fascial flap from each side was positioned over the repair. Next, a fasciocutaneous local flap, designed as a Limberg flap, was harvested and transposed into the defect. The wound edges were closed at fascial and skin levels, Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Amniotic membrane graft draped over the sutured dura.

Figure 3.

Limberg flap for closure of skin defect.

Intravenous antibiotics were administered for 2 days postoperative. Wound closure was uneventful and sufficient recovery ensured. No leakage of cerebrospinal fluid was observed.

The latest follow-up visit was at 12-months of age where the girl was doing well. A small skin correction was performed on the standing cutaneous deformity at the pivot point of the fascio-cutaneous flap at 13-months of age.

Case 2

A boy was delivered by elective cesarean section at 38+1 weeks of gestation. The baby was prenatally diagnosed, by ultrasound, at 20 weeks of gestation and a subsequent MRI scan at 35 gestational weeks, with a long MMC from the thoracolumbar junction to the sacral bone as well as hydrocephalus. At delivery, the MMC was partially intact measuring 7.5 cm by 10 cm, with a small amount of fluid leakage when manipulated. The amnion graft was harvested and stored as described above. Within the first 24 h after delivery, the surgery was carried-out under general anesthesia by a multidisciplinary setting with neuro- and plastic surgeons. A ventriculo-peritoneal shunt insertion initiated the staged procedure. A layered closure was then performed of the MMC similar to case 1. Microscopic magnification was used to dissect the neural placode and dura, which was closed separately. Again, dysplastic meninges were removed. The autologous amniotic membrane graft was draped over the sutured dura defect and fastened with resorbable sutures. A resection of the skin edges closest to the MCC was performed followed by a wide undermining from the edges of the MMC at a level immediately above the lumbodorsal aponeurosis. The dissection of these fasciocutaneous flaps extended cranially under the latissimus dorsi muscles, laterally subcutaneously to the anterior axillary fold towards the abdomen and caudally down over the iliac crest; lifting the upper portion of fibers of the gluteus maximus muscles on both sides. To obtain tension free closure over the MMC a relaxing incision was made on the right side in the midaxillary line and extended caudally with a backcut parallel to the fibres of the gluteus maximus muscle. The flaps were advanced medially to allow a longitudinal midline closure. A Z-plasty was performed in the gluteal area of the relaxing incision allowing an almost complete direct closure. A small defect of 1 cm by 1.2 cm in the relaxing incision cranially was left to heal by secondary intention. The wound edges were closed at fascial and skin levels with 5-0 resorbable sutures, Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Fasciocutaneous flaps with relaxing incision in midaxillary line.

Prophylactic intravenous antibiotics were administered from the beginning of surgery till 7 days postoperatively. Immediate postoperative recovery was uneventful but a defect in the midline closure occurred 14 days postoperatively. The defect measuring 3 cm by 3 cm involved all skin layers, leaving the amnion graft exposed. The child was also treated for an infection and the ventriculo-peritoneal shunt had to be replaced as a consequence. There were no signs of local infection in the defect in the midline closure and it healed by secondary intent within 30 days with good coverage. No surgical revision was found necessary. No leaking of spinal fluid was reported at any time in the recovery period.

At the 12-month follow-up visit the reconstruction was completely healed and the boy was doing well.

Discussion

Human amniotic membrane may be used in a number of clinical and surgical settings, predominantly in plastic surgery. These include biological wound dressing, reconstructive surgery (dura, oral cavity, mucosal lining) and as a lining for flap and tendon or nerve surgery.5

In this case report, similar to that described in previous reports, the amnion grafts provided a well-suited, easily managed, cost-free autologous material for cover of the neurosurgical repair.6, 7 Beyond being an apt graft, the amnion is furthermore ascribed antibacterial properties in a situation with partial-wound rupture in a case report by Hasegawa et al.6 In the two cases presented here, the amnion grafts provided a water-tight closure with no leakage of spinal fluid reported at any time during recovery.

Two approaches to covering the skin defect are described in this report. For the smaller defect in case 1 a local flap was designed and transposed into place. This provided a tension-free, well vascularized repair with minimal donor site morbidity and speedy recovery. A small corrective operation was necessary to redress skin excess at the pivotal point of the flap. For the larger defect, described in case 2, closure was achieved with bilateral, wide undermining, raising fasciocutaneous flaps as described by Iacobucci et al. in 1996.8 In this case, similar to the one described by Hasegawa, excessive skin tension resulted in small defects in the midline closure at skin level, healing by secondary intent.

Several alternative local and regional, fasciocutaneous and musculocutaneus flaps have been described in the literature depicting good, viable solutions for defect closure of varying sizes.9, 10 In each MMC case presented, the surgeon must therefore evaluate the individual circumstances regarding defect size, skin tension, donor site morbidity etcetera when deciding on the method for optimal skin repair.

In conclusion, a free amnion graft is a viable choice in reconstructive surgery for MCC in comparison to acellular dermal matrix as it is autologous and cost free. A multidisciplinary team involving obstetrician, neurosurgeon and plastic surgeon is essential in planning harvesting, storing and repair of the myelomeningocele with an amnion graft.

Disclosure

Conflict of interest and funding: none

This manuscript adheres to the STROBE guidelines.

Footnotes

Portions of this work were presented in poster form at 1st Annual Research Meeting at the Department of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University Hospital, Skejby, Denmark, 14 November, 2017 as well as an oral presentation at The Annual Spring Meeting of the Danish Society for Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Panum Institute, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, 3 June, 2016.

References

- 1.Greene NDE, Copp AJ. Neural tube defects. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2014;37:221–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062012-170354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radcliff E, Cassell CH, Laditka SB, Thibadeau JK, Correia J, Grosse SD. Factors associated with the timeliness of postnatal surgical repair of spina bifida. Childs Nerv Syst. 2016;32(8):1479–1487. doi: 10.1007/s00381-016-3105-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hao Y, Ma DH, Hwang DG, Kim WS, Zhang F. Identification of antiangiogenic and antiinflammatory proteins in human amniotic membrane. Cornea. 2000;19(3):348–352. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200005000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koizumi NJ, Inatomi TJ, Sotozono CJ, Fullwood NJ, Quantock AJ, Kinoshita S. Growth factor mRNA and protein in preserved human amniotic membrane. Curr Eye Res. 2000;20(3):173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairbairn NG, Randolph MA, Redmond RW. The clinical applications of human amnion in plastic surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67(5):662–675. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasegawa M, Fujisawa H, Hayashi Y, Yamashita J. Autologous amnion graft for repair of myelomeningocele: technical note and clinical implication. J Clin Neurosci Off J Neurosurg Soc Australas. 2004;11(4):408–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Weerd L WeumS, Sjavik K, Acharya G, Hennig RO. A new approach in the repair of a myelomeningocele using amnion and a sensate perforator flap. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66(6):860–863. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iacobucci JJ, Marks MW, Argenta LC. Anatomic studies and clinical experience with fasciocutaneous flap closure of large myelomeningoceles. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97(7):1400–1410. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199606000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lien SC, Maher CO, Garton HJL, Kasten SJ, Muraszko KM, Buchman SR. Local and regional flap closure in myelomeningocele repair: a 15-year review. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26(8):1091–1095. doi: 10.1007/s00381-010-1099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kesan K, Kothari P, Gupta R, Gupta A, Karkera P, Ranjan R. Closure of large meningomyelocele wound defects with subcutaneous based pedicle flap with bilateral V-Y advancement: our experience and review of literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2015;25(2):189–194. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1368796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]