Abstract

Patient: Male, 72-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Fournier gangrene

Symptoms: Infection • pain • swelling

Medication: Canagliflozin

Clinical Procedure: Debriment

Specialty: Dermatology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are a class of antihyperglycemic medications associated with an increased risk of urinary and genital infections due to their glycosuric effects. In 2018, the FDA issued a safety alert warning that multiple cases of Fournier’s Gangrene (FG), a severe genital infection, had been reported in patients taking SGLT2 inhibitors.

Case Report:

We present a case of 72-year-old male with type II diabetes mellitus who developed FG while taking the SGLT2 inhibitor canagliflozin. Besides diabetes and canagliflozin use, his other risk factors were his age, gender, and remote history of radiotherapy for prostate cancer. He presented to the Emergency Department (ED) multiple times complaining of rectal pain and was admitted for a possible diagnosis of prostatitis. During his stay, he developed leukocytosis, his pain worsened, and examination of the perianal area was consistent with FG. He was treated with multiple surgical debridement procedures and broad-spectrum antibiotics; the source of infection was determined to be a perianal abscess. He stayed in the hospital for 1 month and was discharged home with outpatient wound care and vacuum dressing changes. Canagliflozin was discontinued during the hospital stay.

Conclusions:

Due to the possible association of FG with SGLT2 inhibitors, patients who present with signs and symptoms consistent with FG should be examined for possible FG and treated promptly.

MeSH Keywords: Fasciitis, Necrotizing; Fournier Gangrene; Sodium-Glucose Transporter 2

Background

Fournier’s gangrene (FG), also known as necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum, is a rare, rapidly progressing urological emergency [1]. A recent epidemiological study conducted in the United States determined that FG accounted for <0.02% of hospital admissions and had a case fatality of 7.5% [2]. Risk factors for FG include being male, older age, diabetes mellitus, obesity, alcohol misuse, immunosuppression, local trauma and poor hygiene [2–4]. Most cases of FG are polymicrobial and generally require multiple surgical debridement procedures and treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics [2].

Canagliflozin belongs to the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor family, a class of oral medications used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). This class of medications lowers plasma glucose levels by increasing the amount of glucose excreted in the urine and they are well known to increase the risk of minor genital and urinary tract infections [5].

In 2018, the FDA issued a black-box warning that several cases of FG had been reported in patients being treated with SGLT2 inhibitors [6]. Previous case reports have been published on patients who developed FG while taking dapagliflozin [7] and empagliflozin [8]. We present herein, a case report of FG occurring in a patient taking canagliflozin that was successfully managed with multiple surgical procedures and appropriate antimicrobial therapy at a small, rural hospital.

Case Report

A 72-year-old male presented to the Emergency Department (ED) multiple times complaining of rectal pain. His medical history is significant for T2DM with a most recent hemoglobin A1C of 7.5% and prostate cancer successfully treated with radiation 5 years previously with no further intervention. He did not have a significant smoking or alcohol history. He was diagnosed with hemorrhoids at the first visit and sent home with a prescription hemorrhoids cream. At his second visit, he was diagnosed with presumed prostatitis and started on ciprofloxacin. Upon rectal examination, there were no signs of FG in the perianal area at that time.

The patient presented to the ED a third time 2 days after his previous visit with abdominal pain rated 8/10 and significant nausea. He was admitted with a diagnosis of prostatitis and abdominal pain not yet diagnosed. He reported explosive diarrhea which persisted throughout the first 5 days of his admission. Clostridioides difficile tests were negative and the diarrhea was attributed to his antibiotic use. A computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen/pelvis was ordered which indicated some distention of the bladder but was otherwise unremarkable. On the same CT, given that the patient had a history of bladder cancer, the CT scan showed markedly enlarged prostate, stable thickening of the urinary bladder wall of likely related to its suboptimal distension, and stable lipoma between the right gluteus medius and minimus. No residual gas found in the bladder lumen.

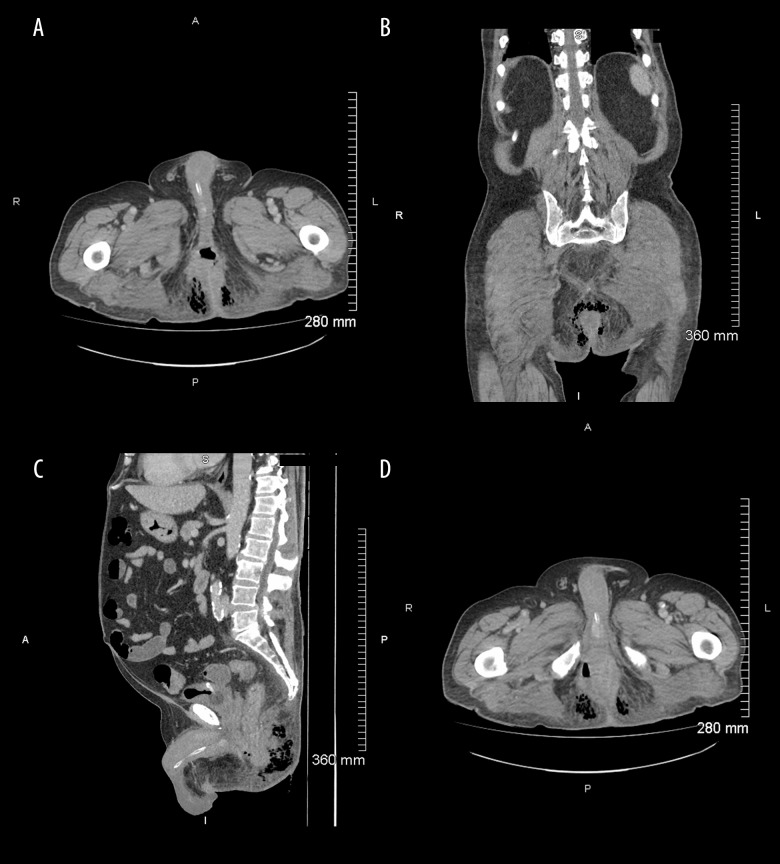

On the 5th day of admission, the patient was unable to mobilize. A rectal and genital examination was conducted for the first time since his admission, and he was found to have an incredibly tender, red scrotum with skin was peeling in small amounts. The area from the base of the penis towards the perineum was quite painful and the perineum was indurated in an area of at least 10×15 cm. The patient was afebrile but had an elevated white count of 17.8×109 cells/L, which was increased from 11×109 cells/L at admission. An urgent CT scan was conducted due to concerns of skin necrosis near the anal verge. The CT scan (Figure 1) was positive for gas-forming infection mainly centered in the ischioanal fossa and was suspicious for a perianal fistula.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan. (A) Standard transverse images, in the portal venous phases, demonstrates gas within the ischioanal fossa bilaterally. There is extensive soft tissue stranding. (B) Axial and coronal planes: The gas vacuoles within the soft tissue and around the anal canal consistent with gas due to gangrene. (C) Sagittal images demonstrate this associated gas and fluid-filled tract extending up to the elevator musculature. The changes across the midline are in close proximity to the posterior aspect of the anal canal. (D) Lower slices of transverse images demonstrate that the changes cross the midline and are in close proximity to the posterior aspect of the anal canal, in keeping with an ischiorectal abscess with horseshoe extension.

Emergency surgery with aggressive debridement down to healthy tissue was promptly performed. Figures 2–4 show the patient’s perianal area. There was a high suspicion for polymicrobial infection because the patient was diabetic. Intravenous meropenem, vancomycin, and clindamycin were started before the surgery and continued for 8 days. During surgery, extensive necrotizing infection of ischiorectal soft tissue with horseshoe abscess and posterior communication of bilateral ischiorectal fossa, anterior extension of the perineal body, and fistulization to the right posterolateral anoderm was observed. A loop sigmoid colostomy was also done to divert stool from the area. Two additional procedures under anesthesia were performed involving surgical debridement, placement of a negative pressure dressing and a rectal tube. A fourth procedure under anesthesia was done to examine the wound healing, replace the rectal tube and negative pressure dressing. Further dressing changes were done under sedation at the bedside every 2 to 3 days throughout the patient’s hospital stay.

Figure 2.

Picture of the patient’s perianal area.

Figure 3.

Picture of the patient’s perianal area with a drainage tube during operation.

Figure 4.

Picture of the patient’s perianal area with a drainage tube during operation.

Microbiology results confirmed polymicrobial FG with the growth of Bacteroides ovatus (fragilis group), Prevotella denticola and Actinomyces species. After 8 days of intravenous antibiotics, the patient’s wounds were much improved, and his leukocytes had returned to normal range. He was stepped down to oral sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, ciprofloxacin, and metronidazole. Oral antibiotics were continued for an additional 6 days for a total of 14 days of antimicrobial therapy.

Canagliflozin was discontinued during the hospital stay and the patient was instructed not to take any SGLT2 inhibitors in the future. The patient had been on canagliflozin for 6 years prior to hospital admission. No additional anti-hyperglycemic medications were needed because the patient lost a significant amount of weight and his blood glucose levels were controlled on his remaining home medications: metformin, sitagliptin, and insulin glargine.

Discussion

We have presented a case of the successful management of FG at a small rural institution. Successful management was due to prompt diagnosis, multiple surgical debridement procedures, and appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

There is no consensus in the literature on the optimum antimicrobial treatment for FG. The Infectious Disease Society of America recommends a broad-spectrum carbapenem, cephalosporin, or beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor plus an agent to cover methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and clindamycin for its antitoxin effects against toxin-producing streptococci or staphylococci strains [9]. This patient received meropenem, vancomycin for MRSA coverage, and clindamycin for its antitoxin activity. He was stepped down to appropriate oral antibiotics when he was clinically stable, and the results of his wound cultures were available.

As described, FG is a life-threatening and rapidly progressing infection. In 2018, the FDA released a warning stating multiple cases of FG had been reported in patients taking SGLT2 inhibitors. Between March 2013 and January 2019, 55 unique cases of FG occurring in patients being treated with SGLT2 inhibitors were reported to the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System, of which 21 were linked to canagliflozin [6]. Previous reports of patients developing FG while taking dapagliflozin [7] and empagliflozin [8] have been described. We have described the first case report of a patient developing FG while taking canagliflozin. There is insufficient evidence at this point to suggest a causal relationship between the development of FG and the use of SGLT2 inhibitors [10]. Diabetes, especially uncontrolled diabetes, is a well-known risk factor for FG. However, the patient described herein was relatively well-controlled with an A1C of 7.5%. Other risk factors present in our patient include his gender, age and possibly his history of radiotherapy.

FG has been described as a rare complication of radiotherapy, although FG generally occurs during radiotherapy or shortly after radiotherapy was completed [11]. Klement et al. [11] described a case of a patient who developed FG and passed away 6 days after completing radiotherapy for rectal cancer, and Czymek et al. [12] identified three patients that developed FG during radiotherapy. One case report describes a case of FG occurring 2 years following radiotherapy, although chronic use of steroid enemas for post-radiation proctitis may have also contributed to this case [13]. Our patient was treated with radiation for prostate cancer 5 years before his hospital admission and did not have any signs or symptoms of post-radiation proctitis in that time period. Although unlikely to have contributed significantly, we are unable to rule out the patient’s history of radiation as a contributory factor in this case.

Due to the high morbidity and mortality associated with FG and the need for prompt identification, diagnosis, and treatment, it is important that clinicians are aware of this association and have a high-level suspicion when patients present with signs and symptoms of FG.

Many clinicians favor the use of SGTL2 inhibitors due to their documented cardiovascular and renal benefits which are out of proportion to their glucose, blood pressure, and body weight lowering properties [14–16]. Prescribers must weigh these benefits against known adverse effects such as the increased risk of minor genital and urological infections as well as the possible association with more severe events including diabetic ketoacidosis [16], lower limb amputation [15] and FG [6]. It has recently been proposed that the cardio-renal benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors and these more rare and serious adverse events may be due to the same off-target effects on sodium-proton antiporter proteins [17].

Conclusions

We present a case of a patient who developed FG while taking canagliflozin. A causal link between SGLT2 inhibitors and FG has not been established. However, due to the rapidly progressing nature of FG and severe complications including death, it is important for clinicians to have a high degree of suspicion when a patient who is taking an SGLT2 inhibitor presents with symptoms consistent with FG.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Stephanie Lee and WDMH staff and physicians for their cooperation and hard work.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

None.

References:

- 1.Yanar H, Taviloglu K, Ertekin C, et al. Fournier’s gangrene: Risk factors and strategies for management. World J Surg. 2006;30(9):1750–54. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0777-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorensen MD, Krieger JN. Fournier’s gangrene: Epidemiology and outcomes in the general US population. Urol Int. 2016;97(3):249–59. doi: 10.1159/000445695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thwaini A, Khan A, Malik A, et al. Fournier’s gangrene and its emergency management. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(970):516–19. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.042069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh A, Ahmed K, Aydin A, et al. Fournier’s gangrene. A clinical review. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2016;88(3):157–64. doi: 10.4081/aiua.2016.3.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cefalu WT, Riddle MC. SGLT2 inhibitors: The latest “new kids on the block”! Diabetes Care. 2015;8(3):352–54. doi: 10.2337/dc14-3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bersoff-Matcha SJ, Chamberlain C, Cao C, et al. Fournier gangrene associated with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors: A review of spontaneous postmarketing cases. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):764–69. doi: 10.7326/M19-0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onder CE, Gursoy K, Kuskonmaz SM, et al. Fournier’s gangrene in a patient on dapagliflozin treatment for type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2019;11(5):348–50. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar S, Costello AJ, Colman PG. Fournier’s gangrene in a man on empagliflozin for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2017;34(11):1646–48. doi: 10.1111/dme.13508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10–52. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloomgarden Z, Einhorn D, Grunberger G, Handelsman Y. Fournier’s gangrene and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: Is there a causal association? J Diabetes. 2019;11(5):340–41. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klement RJ, Schäfer G, Sweeney RA. A fatal case of Fournier’s gangrene during neoadjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2019;195(5):441–46. doi: 10.1007/s00066-018-1401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czymek R, Hildebrand P, Kleemann M, et al. New insights into the epidemiology and etiology of fournier’s gangrene: A review of 33 patients. Infection. 2009;37(4):306–12. doi: 10.1007/s15010-008-8169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nabha KS, Badwan K, Kerfoot BP. Fournier’s gangrene as a complication of steroid enema use for treatment of radiation proctitis. Urology. 2004;64(3):587–88. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2117–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neal B, Perkovic V, Zeeuw D, et al. Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of the Canagliflozin cardiovascular assessment study(CANVAS) – a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am Heart J. 2013;166:217–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. DECLARE–TIMI 58 Investigators: Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2018;380:347–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCullough PA, Kluger AY, Tecson KM, et al. Inhibition of the sodium-proton antiporter (exchanger) is a plausible mechanism of potential benefit and harm for drugs designed to block sodium glucose co-transporter 2. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2018;19(2):51–63. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm.2018.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]