Abstract

Organic semiconductors are an important class of optoelectronic material that are widely studied because of the scope for tuning their properties by tuning their chemical structure, and simple fabrication to make flexible films and devices. Although most effort has focused on developing displays and lighting from these materials, their distinctive properties also make them of interest for visible light communications (VLCs). This article explains how their properties make them suitable for VLC and reviews the main uses that have been explored. On the transmitter side, record white VLC communication has been achieved by using organic semiconductors as colour converters, while direct modulation of organic light-emitting diodes is also possible and could be of interest for display-to-display communication. On the receiver side, organic solar cells can be used to harvest power and data simultaneously, and fluorescent antennas enable fast and sensitive receivers with large field of view.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Optical wireless communication’.

Keywords: Li-Fi, colour converters, organic light-emitting diode, organic photovoltaic, fluorescent antennas

1. Introduction

Organic semiconductors are a special type of plastic materials with unique electronic and optical properties. They are particularly interesting because they combine novel semiconducting optical and electrical properties with simple fabrication and tuning of properties associated with organic materials. The electrical and optical properties of organic semiconductors are mainly due to their chemical structure, so they do not need to be highly ordered crystals, in contrast with inorganic semiconductors. This makes their device fabrication simple—for example, by deposition from solution—and is expected to translate into reduced cost of the final devices. In addition, it enables side-by-side fabrication of different devices, such as red, green and blue organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) in a mobile phone display or television.

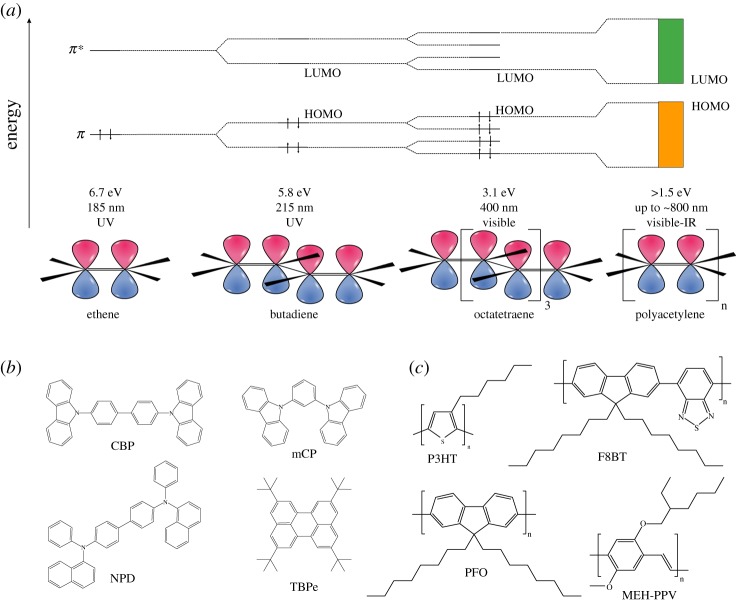

The optical and electrical properties of organic semiconductors derive from their chemical structure, which consists of alternating single and double bonds between adjacent carbon atoms, known as conjugation. This leads to the overlap of electronic orbitals and electron delocalization (figure 1a). In conjugated molecules, the carbon atoms are sp2-hybridized. Three of the four valence electrons are in orbitals in the plane of the molecule which form σ-bonds which hold the molecule together. The fourth valence electron is located in a p orbital extending above and below the plane of the molecule. The overlap between the 2pz orbitals results in the formation of π-bonds and (when there are many atoms) π and π* bands. Electrons are delocalized along the molecule, and it turns out that there are two such electrons per repeat unit, leading to a filled band and semiconducting electrical and optical properties. This means that they can be used to make a range of semiconducting devices including light-emitting diodes, solar cells, transistor and lasers. The commonly used organic semiconductor materials come from three groups: small molecules, polymers and dendrimers [1,2]. Many are soluble and so enable very simple deposition from solution; others are deposited by evaporation to make thin films for devices.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of energy levels in alkenes as a function of conjugation length. With increasing conjugation length, the energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO decreases, resulting in absorption and emission at longer wavelengths. (b) Chemical structures of several commonly used small molecule organic semiconductors for OLEDs. (c) Chemical structures of several commonly used organic semiconductor polymers. (Online version in colour.)

A new field in which organic semiconductors are finding multiple applications is visible light communications (VLCs). Although light has been used for communication since ancient times, it is over the past 30 years that optical fibres have come to dominate communications, and much more recently that strong interest in free space VLC has developed [3]. Also known as Li-Fi (short for light fidelity) [4], light has many attractive features for data communications, including (i) hundreds of terahertz licence-free bandwidth, (ii) simple front-end devices, (iii) no interference with sensitive electronic equipment, and (iv) possibility for integration into the existing lighting infrastructure [5–7].

There are four main categories of devices based on organic semiconductors in VLC applications: colour converters, OLEDs, photo detectors (including both organic photovoltaics (OPVs) and organic photodiodes (OPDs)) and optical antennas. These devices use the distinctive properties of organic semiconductors in various ways. For example, the extensive electron delocalization leads to very strong absorption and consequently a high radiative rate for emission. This leads to a fast on–off response when used for colour converters and optical antennas. Meanwhile, the scope to tune the energy gap by adjusting the chemical structure is useful for optimizing the absorption of OPVs and OPDs, and the emission of OLEDs.

Throughout this article, results in terms of achievable bandwidth and data rates are presented. The bandwidth, in this review is defined, as the frequency at which the electrical output power of the detector falls to −3 dB, i.e. 50% of its value at DC. Data rates are also reported though are affected by a range of factors such as encoding scheme used and achievable SNR. Where possible, we provide the essential experimental details associated with reported data rates.

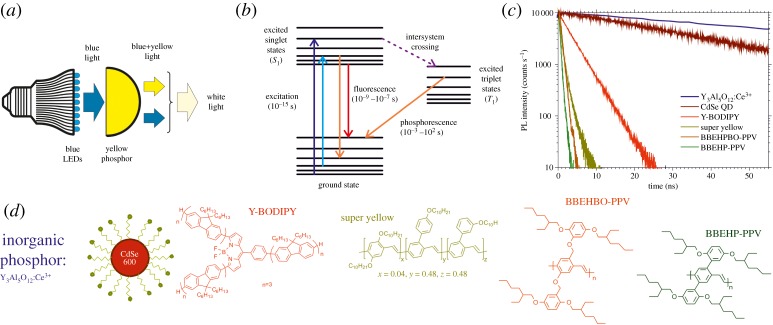

2. Organic semiconductors as colour converters in visible light communication applications

One of the visions of VLC is to use light fittings both for illumination and communication simultaneously [8,9]. Solid-state lighting technology is already an established approach to provide good quality and cheap lighting. Blue-emitting GaN/InGaN LEDs coated with wavelength-converting phosphors are used as white-light sources [10–12]. The role of the phosphor is to absorb part of the blue emission of the LED and convert it into yellow emission, resulting in white light (figure 2a). To achieve high quality of illumination, which is measured by the colour rendering index (CRI), a broad emitter covering the green to red part of the spectrum is chosen, while even higher CRI can be achieved by multiple emitters (green and red phosphors) [13]. Although phosphors are very suitable for generating white light from LEDs [14–17], their long luminescence lifetime (∼ microseconds) (figure 2b,c) leads to a slow response that is a well-known bottle-neck for VLC applications [6,18]. Some early publications in white-light VLC used a yellow filter to filter out the slow phosphor emission to speed up the data transmission [19]. The disadvantage of this approach is that only a portion of the illumination power is used for the data communication, thus limiting the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and the achievable data rate.

Figure 2.

(a) Basic principle of a white LED based on a phosphor colour converter. The electroluminescence from a blue LED is partially absorbed by a phosphor colour converter. The phosphor emits the absorbed energy as yellow light. The mixture of blue and yellow light results in white light. (b) Energy diagram of fluorescence and phosphorescence processes in an organic molecule. A photon excites an electron to a higher energy level, leading to the formation of a bound electron–hole pair, or exciton, on the molecule. The exciton is formed in a singlet spin configuration (S1). The exciton can relax from S1 to the ground state with the emission of a photon (fluorescence) which is a fast process (10−9–10−7 s). The singlet can also relax non-radiatively to the ground state, or intersystem cross to an excited triplet states (T1). The transition from T1 to ground state (known as phosphorescence) has low probability, resulting in a much slower decay time (10−3–102 s). (c) A comparison plot of the time response for various colour converter materials: a commercial YAG yellow phosphor (CL-827), a CdSe quantum dot, a custom-synthesized BODIPY molecule with oligofluorene arms (Y-BODIPY) [35], the commercial fluorescent polymer ‘super yellow’ (SY) and two custom-synthesized fluorescent polymers (BBEHP-PPV [34] and BBEHBO-PPV [38]). (d) Chemical structure of the various materials presented in (c). (Online version in colour.)

Relatively recently, a new field has developed to identify alternatives to rare-earth phosphor colour converters. The motivation for these materials is the shortage and lack of recycling ability of rare-earth phosphors [20]. These alternative materials include families such as metal-organic frameworks [21,22], nanoparticles [23–28] and light-emitting polymers [29–33]. To be an effective colour converter for VLC, though, there are several criteria which a candidate material should satisfy. Firstly, the material should be suitable for illumination: (i) it should absorb in the region of 450 nm to match the nitride LEDs used for lighting; (ii) it should have high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), which is the number of photons emitted per photon absorbed; (iii) the emission should be in the yellow region of the visible spectrum so that the combination of its emission with residual blue light from the LED results in white light; (iv) the emission spectrum should be sufficiently broad to achieve good quality of illumination (high CRI). In addition, specifically for the VLC application, (v) the time response of the materials should be fast (less than 10 ns, preferably less than 1 ns) and comparable to the response of the other components of the data link. Simultaneously satisfying all of the above criteria is rather complex and demanding. Thus, the search for an appropriate material is also challenging. We note that for wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM) VLC scenarios, where multiple light sources of different colours are used, criteria (iii) and (iv) would be adapted to the combination of emitters used giving good colour rendering.

Taking account of the above considerations, in 2014, Chun et al. [18] demonstrated an approach for white-light VLC in which the phosphor was replaced by an organic semiconductor colour converter. The simultaneous requirement for short emission lifetime and high PLQY means that high radiative rate is needed, which as mentioned earlier is a distinctive property of highly conjugated materials. Accordingly, the authors used the commercially available conjugated polymer ‘super yellow’ (SY) to generate white light from an inorganic µ-LED. The fast time response of SY (figure 2c) enabled a bandwidth of more than 200 MHz to be achieved. This bandwidth was limited by the other components of the system (the excitation source and the detector) and importantly was achieved without spectral filtering at the receiver. Even though, an illumination level of only 240 lx was achieved, partially due to low output power of the micro-LED used, they reported a 1.68 Gbps data rate. This was a record for white-light VLC link at the time of publication, and demonstrated the feasibility of using fast fluorescent colour converters to enhance data rate.

The above work has been followed by further reports exploring organic semiconductors as colour converters for VLC applications. Sajjad et al. [34,35] showed that blends of two organic molecules can be used as fast colour converters. This provides a convenient way of tuning colour by controlling the proportion of two polymers and the thickness of the film. Any CIE coordinate in the InGaN LED/polymer 1/polymer 2 is achievable, while the quality of the white light is high (i.e. high value of CRI), due to combined emission of the polymers. In this work, one polymer is excited and partially transfers its energy to another, by a process known as Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) which takes place on a picosecond time scale. This is interesting because the energy transfer process is an additional decay pathway for excitations, and so speeds up the fluorescence of the initially excited polymer. For example, in publication [34], it was demonstrated that the lifetime of the BBEHP-PPV (τ = 0.83 ns), when blended with MEH-PPV (τ = 0.38 ns), can be reduced to 0.27 ns. This allowed the team to achieve high bandwidth (greater than 200 MHz), good CRI and data rates (greater than 350 Mbps).

Other publications have explored specially synthesized organic and polymer materials as colour converters for VLC. Vithanage et al. [36] studied star-shaped molecules that have a BODIPY core with different lengths of side arm. They demonstrated that Y-BODIPY molecules (figure 2d) with 3 fluorene units per arm (Y-B3) achieve the highest bandwidth of 73 MHz and also the best data rates of 370 Mbps. The time-resolved fluorescence of this material is shown in figure 2c. The fluorescence decay of Y-B3 is much faster than a typical phosphor (CL-827) or a II-VI quantum dots [37], but the conjugated polymers are faster still, making them more attractive. BBEHP-PPV has an exceptionally fast fluorescence decay, but is a green emitting material. A new conjugated polymer, BBEHBO-PPV, was therefore developed to have red-shifted emission. It retained the poly(2,5-dialkoxy-p-phenylene vinylene) backbone with bulky substituents of BBEHP-PPV, but attached the side groups via an alkoxy bridge (as applied in MEH-PPV) [38]. Owing to its extremely short fluorescence lifetime (0.37 ns), the material showed a high bandwidth of 470 MHz, while achieving a data rate of 550 Mbps [38] with on–off keying. Zhang et al. [39] have reported the application of aggregation-induced emission luminogens (AIEgens) as colour converters. The authors have investigated various AIEgens covering the whole visible spectrum from blue to red. These materials show high bandwidths, up to 279 MHz −6 dB electrical (approx. 110 MHz of −3 dB electrical), allowing them to achieve data rates of almost 500 Mbps. Interestingly, the authors also verified experimentally the theoretical relation [40] between the modulation bandwidth and the photoluminescence lifetime decay:

Other VLC colour converter research has included routes to enhance the behaviour of organic semiconductors with metamaterials [41] and the use of perovskite nanoparticles [42]. In [41], Yang et al. took advantage of the Purcell effect by using nanopatterned hyperbolic metamaterials to enhance the radiative rate of an organic semiconductor colour converter. Specifically, the authors achieved an increase in bandwidth of the super yellow polymer by 67% without compromising the strength of the emission. Practically, this allowed an increase in the transmitted data rate from 150 Mbps, with bandwidth of 75 MHz, for planar super yellow films, to 250 Mbps, with bandwidth of 125 MHz, for the nanopatterned system. Mei et al. [42] have studied perovskite quantum dots, as colour converters. They used yellow-emitting CsPbBr1.8I1.2 quantum dots and demonstrated a bandwidth of 73 MHz and data rate of 300 Mbps.

Organic semiconductors are an attractive alternative to inorganic phosphors as colour converters for blue-emitting LEDs. Their advantage is primarily due to their fast time response, with the additional benefit of being able to tune the light emission for bespoke lighting solutions. Their short emission lifetime (sub-nanosecond to few nanosecond) overcomes the bottle-neck due to the slow response (microsecond range) of traditional phosphors. Organic semiconductors have considerable potential as colour converters in lighting, not only because they can implement more efficient white-light VLC links, but also because they can provide high-quality light cheaply, and without dependence on the rare-earth elements in inorganic phosphors.

3. Organic light-emitting diodes as light sources for visible light communications

Organic semiconductors can be used to make a range of semiconducting devices including organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), solar cells and transistors. An OLED consists of one or more organic semiconductor layers sandwiched between suitable contacts. When a voltage is applied, it emits light. While electroluminescence in a single crystal of anthracene was reported by Pope and co-workers as early as 1963, practical thin film OLEDs are generally attributed to Tang & VanSlyke [43] and Burroughes et al. [44]. OLEDs were initially developed for display applications and are now used in many commercial mobile phone displays and some televisions. Owing to their unique fabrication and emission characteristics, they are now also being developed for lighting, smart devices and wearables [45–48]. The progress made means that it is now possible to apply OLEDs as transmitters for VLC and this has become an active area of research in recent years [49,50].

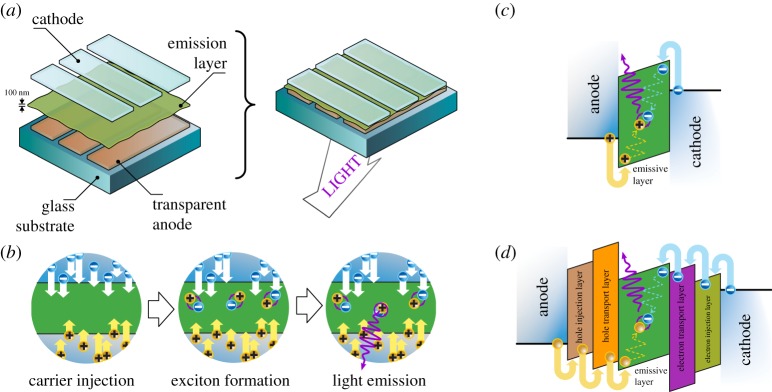

The working principle of an OLED with the simplest structure is shown in figure 3a–c: an organic semiconductor light-emitting layer is placed between two contacts. One of the contacts needs to be transparent, so indium tin oxide (ITO) is commonly used, and its high work function makes it suitable to be the anode, i.e. to inject holes into the organic layer. The other electrode (cathode) is a metal and injects electrons into the organic layer. The injected holes and electrons move across the organic layer under the applied electric field, and charge pairs bind to form excitons (figure 3b). The exciton can then decay radiatively, and some of the light escapes from the device through the transparent contact. The efficiency of this simple structure is usually low due to unbalanced injection and transport of electrons and holes. Modern OLEDs therefore usually include additional layers to control charge injection, transport and recombination and so obtain much higher efficiency (figure 3d). The introduction of additional layers for injection of holes and electrons solves the problem of imbalanced carriers, by lowering the energy gap for injection from the electrodes [43,44,51]. Additionally, hole and electron transport layers can prevent the carriers from escaping the emissive layer without recombination. A more complete description of the principles of OLED operation can be found in [31,51,52].

Figure 3.

Basic principle of OLED operation. (a) Structure of a single-layer-OLED. (b) Mechanism of OLED operation: carrier injection from contacts, formation of exciton by holes and electrons, and light emission from an exciton. (c) Energy diagram of the single-layer-OLED. (d) Energy diagram of modern multi-layered-OLED. (Online version in colour.)

As mentioned earlier, the interest in OLEDs lies in their simple fabrication, emission characteristics, and the scope to be flexible and integrated into other objects. Many OLED materials can be deposited from solution, while others are thermally evaporated. This eliminates the need for high-temperature epitaxial growth, and makes possible simple patterning of different colours side by side, and reductions in the overall cost of fabrication [53,54]. The fabrication process of OLEDs enables the use of flexible substrates and so curved monitors and wearable electronics can be realized [45–48,55]. Finally, there is a nearly unlimited number of chemical compounds which can be used as the emissive layer in OLEDs, making it possible to design and tune properties such as emission colour and colour quality [51].

Interest in the possible use of OLEDs as transmitters for VLC has only recently emerged. They are not obvious candidates for communication because the low mobility of organic semiconductors, and the high capacitance of these very thin devices normally leads to a very low bandwidth. Typical charge mobilities reported for OLEDs are many orders of magnitude lower (10−3–10−5 cm2 (V s)−1) than for the inorganic materials used in LEDs (approx. 1000 cm2 (V s)−1) [56,57]. This is partially mitigated in OLEDs by devices being much thinner (tens to hundreds nanometre). However, this thin device architecture leads to high values of capacitance especially for large OLED pixels (greater than mm2) and consequently drastically limits their bandwidth [49,57].

One of the first reports where an OLED was used as a VLC transmitter is by Minh et al. [58]. They reported a data rate of 2.15 Mbps and a bandwidth of 150 kHz. One strategy followed by the authors was to apply an effective equalization to minimize the effect of the high capacitance of the OLED. This enabled a VLC link to operate at several Mbps despite the large OLED surface area (3 × 4 cm2, Lumiblade OLED by Philips) and resulting high capacitance of the device (approx. 0.3 µF). As a result, the authors improved the achievable bandwidth of the device size and demonstrated a bandwidth of 1 MHz. The same group also reported VLC using another commercial OLED (Osram ORBEOS CMW-031) [59]. They followed the same strategy of using equalization to improve the performance, and reported a data rate reaching 550 kbps, nine times higher than without equalization.

In 2013, the same group published a number of papers, setting a new record for VLC data transfer using OLEDs, investigating different modulation schemes. In [60], Haigh et al. used a spectrally efficient modulation scheme (discrete multiton—DMT) and achieved a data rate of 1.4 Mbps, 14 times the bandwidth of the system used. In [61], they achieved a data rate of 2.7 Mbps and demonstrated online filtering for the first time. This early progress established OLEDs as feasible transmitters for VLC, and this has become an active area of research [49,50].

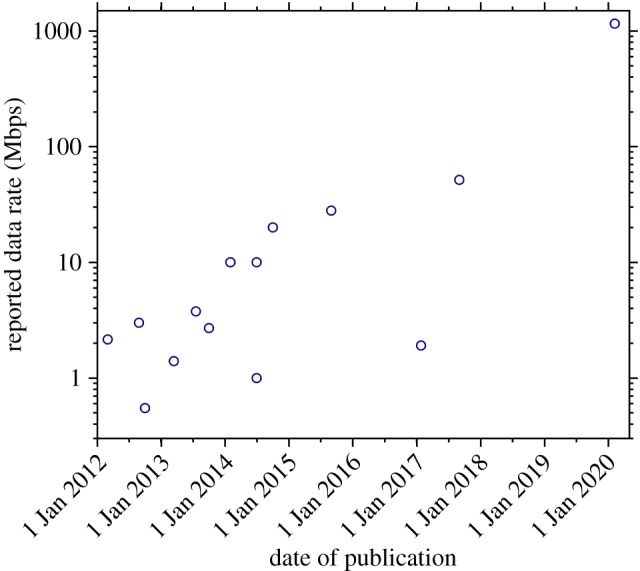

The growth of the reported data rates is shown in figure 4. A new landmark was reached in 2014 [62,63], when a data rate of 10 Mbps was reached. In the same year, the data rate record was further doubled [64] by using a custom-made OLED. The fastest reported data rates were 27.9 Mbps in 2015 [65] and reached 51.6 Mbps in 2017 [66]. A breakthrough was reached in 2020 when Yoshida et al. [67] reported OLED devices which could achieve data rates beyond 1 Gbps in a link 2 m long. They managed to achieve a 20 times leap in data rate by an appropriate choice of emitting materials, small device sizes, carefully designed contacts with low resistance and good heat management by fabricating the devices on oxidized silicon wafers. The good heat management allowed them to operate the devices under high voltage and achieve high bandwidths, reaching 245 MHz.

Figure 4.

Reported VLC data rates using OLED devices as a function of publication date. Note that the vertical scale is logarithmic. (Online version in colour.)

VLC using OLEDs is a fast-growing field. The interest in OLEDs is due to their distinctive characteristics compared to inorganic LEDs, including flexible devices, scalable fabrication of different emitting colours side-by-side, tunability and low cost of production. Despite the limited bandwidth of OLEDs, researchers have demonstrated rapid improvement in the data rates obtained.

4. Organic photodiodes and photovoltaics as receivers for visible light communications

A frequently occurring VLC scenario is where the receiver or the transmitter is a stand-alone device, with no direct access to the power grid. Examples of this scenario include monitoring sensors, mobile home appliances and devices, such as mobile virtual assistants, domestic robots and smartphones. One interesting approach to address the problem of powering these devices is to use photovoltaics as the powering source and as receivers for VLC signal. The idea is that the solar cell will have a dual functionality transforming the ambient and the light for communication into electrical power for powering the stand-alone device.

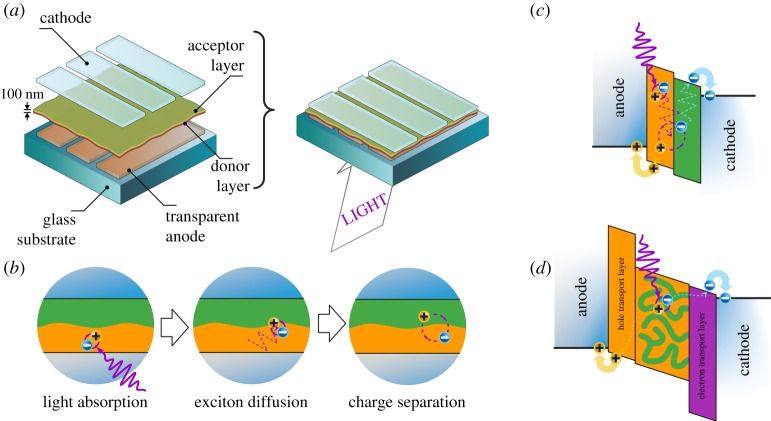

The principle of OPVs is illustrated in figure 5. The basic structure of an OPV is similar to that of OLEDs—with organic semiconductor layer(s) between conductive contacts, one of which is transparent (figure 5a). Light is absorbed by the organic materials, and as a result, a bound electron–hole pair, i.e. an exciton is created (figure 5b). The excitons diffuse to an interface between donor and acceptor materials (or regions of the sample), and the charges are separated by the difference in energy levels between the materials (figure 5c). Finally, the separated charges are extracted at the contacts. In many modern OPVs, the donor and acceptor materials are mixed together to form a so-called bulk heterojunction, while additional layers allow the transport of the desired charges but block the opposite charges from reaching the ‘wrong’ contact (figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Basic principle of operation of an OPV cell. (a) Structure of a bilayer OPV device. (b) Mechanism of OPV operation: photons are absorbed by the donor layer and create excitons. The excitons diffuse to the heterojunction interface with the acceptor and are dissociated into holes and electors. (c) Energy diagram of the dual-layer OPVs. (d) Energy diagram of modern multilayer bulk heterojunction OPV. (Online version in colour.)

The first reports of using OPDs as VLC detectors were published in 2013. Arredondo et al. [68] investigated whether organic bulk heterojunction OPVs based on P3HT : PCBM can be used as photodetectors in VLC. They reverse biased the OPV and demonstrated a modulation bandwidth of 790 kHz. We note that ‘reverse biased’ means that the OPV acts as a photodiode and does not generate power. In [69], Vega-Colado et al. demonstrated an all-organic flexible VLC system. In this study, flexible OPVs were manufactured in a roll-to-roll process and used as a receiver for VLC. They also operated the OPV in reverse bias to improve the bandwidth up to 200 kHz. The aim of the report was to show the possibility of a VLC link made entirely from organic components, and the authors demonstrated audio data transmission. There are further reports where the OPDs were not used as detectors in VLC data links, yet demonstrate that they can be used as fast receivers of modulated light. We highlight some of the reports which have achieved significant bandwidths. Peumans et al. [70] have reported an interesting work, where they used alternating multilayer photodetectors to achieve a −3 dB bandwidth of 430 MHz. They could achieve such fast response due to shorter average exciton lifetime in the presence of many donor–acceptor interfaces at the thin multilayers device. A group led by Ohmori have several publications where they reported OPDs operating in the region of 50–80 MHz [71–73]. In their work, they explored both evaporated and solution processed structures, where CuPc or F8T2 were used as donors and BPPC or PCBM, respectively, as acceptors. Finally, Tsai et al. [74] reported photodiodes achieving 30 MHz bandwidth, taking advantage of the high vertical carrier mobility. They used C60 as the acceptor material and pentacene as the donor material.

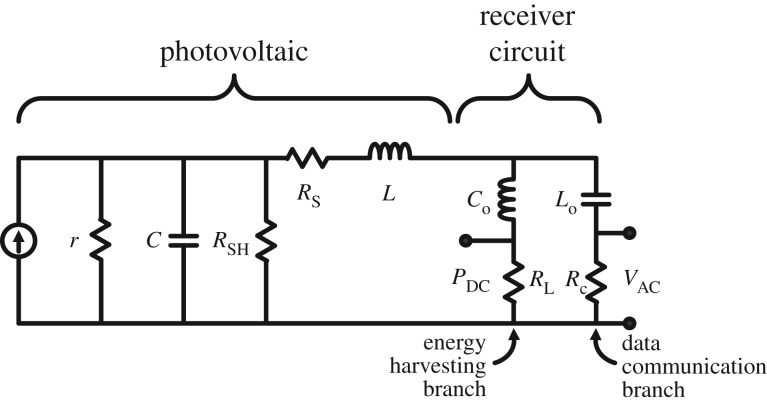

A more innovative way to use the OPV came in 2015 by Zhang et al. [75]. In this report, the authors did not reverse bias the OPV but adapted a receiver circuit (figure 6) to harvest the energy from lighting while simultaneously receiving communication data. The energy harvesting and data communication branches of the receiver circuit were low- and high-frequency filters, allowing the simultaneous dual functionality of the OPV. The authors found that this configuration could simultaneously harvest 0.43 mW of power (5.4 mW cm−2) and receive data at a rate of 34.2 Mbps. When the receiver was optimized for data transmission, the data rate reached 42.3 Mbps.

Figure 6.

Equivalent electric circuit of a solar cell (left part) and receiver circuit (right part) from [75]. The receiver circuit has two branches, which separates the received current into DC and AC components. The DC component is used for energy harvesting, while the AC component for data communication.

The field of OPVs as detectors for VLC is rather new with few reports to date. Despite the relatively low bandwidths and data rates reported so far, they offer the exciting possibility of cheap and self-powered solutions for VLC receivers, and so have great potential for future VLC implementations.

5. Fluorescent antennas for visible light communications

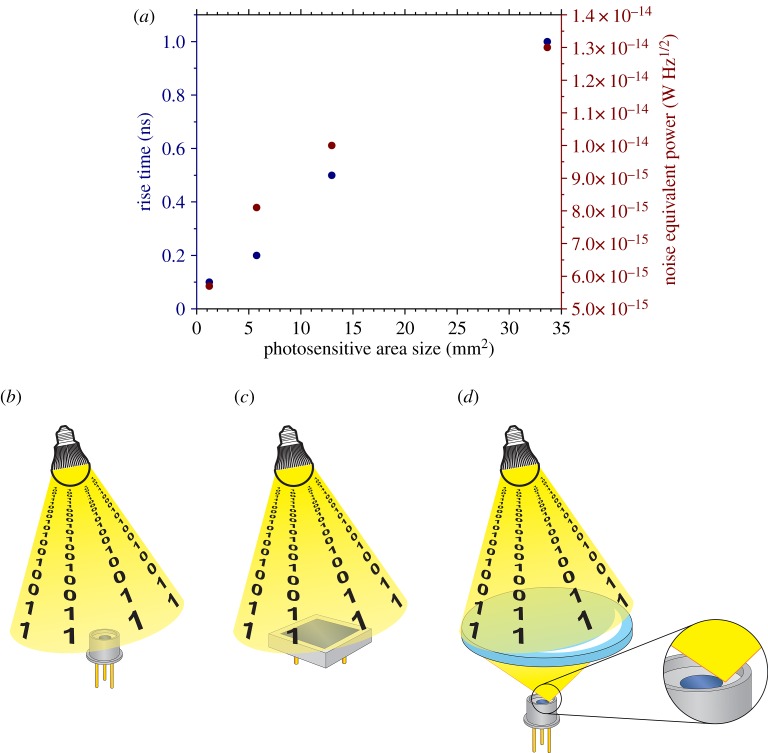

One challenge for VLC is to have receivers that are both sensitive (high SNR) and fast (high bandwidth) (figure 7a). A small photodetector is fast but not sensitive, i.e. has a high bandwidth but provides low SNR (figure 7b). A large photodiode is sensitive, but slow, i.e. has high SNR but low bandwidth (figure 7c). A lens, or another optical element such as a compound parabolic concentrator, can mitigate this by collecting the light over a large area and concentrating it onto a smaller area. Thus, it can increase the SNR of a small photodetector (figure 7d). For these reasons, most VLC systems rely on short focal length optics to focus the light onto fast photodiode receivers to achieve the required SNR and bandwidth for high-speed communications. However, this configuration leads to a need for careful alignment to the source (figure 7d), which is not practical for applications where the receivers are mobile (e.g. a laptop or a smartphone). A recent series of publications has demonstrated an alternative approach, using photonic devices based on fluorescence and total internal reflection, can overcome this limitation and achieve a significant gain with a wide field-of-view.

Figure 7.

(a) Plot of rise time and noise equivalent power as a function of photosensitive area of silicon photodiodes. The plot is based on values provided by the Hamamatsu [99]. (b) If a small photodiode is used in a VLC link, it can provide high bandwidth but low SNR. (c) If a large photodiode is used in the VLC link, it can provide high SNR but low bandwidth. (d) A lens can combine a large collection area with small photodiode and achieve high SNR with high bandwidth, but precise alignment to the source light is crucial. (Online version in colour.)

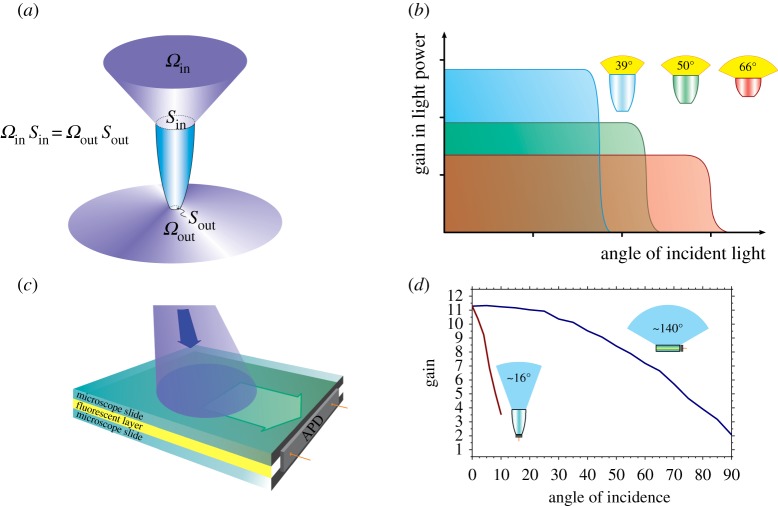

Owing to a fundamental principle in optics, the conservation of étendue [76,77], for any optical system based on refraction and reflection, there will be a trade-off between the optical gain (the output power density, Sout, divided by the input power density, Sin) and the field of view of the system (Ωin) (figure 8a) [78–80]. In practical terms, this means that the more gain an optical system can provide, the more limited is its field of view (figure 8b). As a result, while VLC systems based on optical elements can achieve high SNR due to the high optical gain, they usually have a very limited field of view.

Figure 8.

(a) Conservation of étendue. (b) Graphical comparison of gain and field of view for three compound parabolic concentrators. (c) Basic principle of a fluorescent antenna. (d) Experimental comparison between gain versus angle for a florescent antenna and a concentrating lens. The fluorescent antenna has a field of view (full width at half maximum) of approximately 2 × 70°, while a lens of similar gain has a field of view of about 2 × 8°. (Online version in colour.)

In 2014, Collins et al. [81] theoretically showed that a fluorescent antenna, a device similar to a luminescent solar concentrator [82,83], could be used in VLC to overcome the limitations for optical systems set by the conservation of étendue [84]. Such devices could provide similar gain to conventional optical systems, while maintaining a wide field-of-view. In 2016, the experimental demonstration of this concept was made by two independent groups [36,85]. The principle of these devices is illustrated in figure 8c: the incident light is absorbed in a layer of fluorescent material, and then re-emitted as fluorescence. Most of the emitted light is trapped in the layer by total internal reflection and propagates within the device to the edge of the antenna. Owing to the much smaller cross-section of the edge of the device than the absorbing area, significant optical gain can be achieved, while the field of view follows the cosine law. The experimental result shown in figure 8d demonstrates that these devices can provide much wider field-of-view when compared with lenses with similar optical gains (figure 8d). This is a consequence of the fact that the angle of emitted light is independent from the angle of incident light, and the conservation of étendue between the incident and the emitted light does not apply.

The two experimental publications [84,85] followed rather different approaches for the implementation of the fluorescent antennas. Manousiadis et al. [36] demonstrated devices with a slab geometry, while Peyronel et al. [85] used optical fibres to construct fluorescent antennas. In [36], the device was fabricated by sandwiching a mixture of epoxy with a fluorescent dye between two microscope slides. The authors demonstrated an optical gain of 12, with full width at half maximum field of view of 120°, while the bandwidth of the devices was 40 MHz, significantly higher than that of most commercially available LEDs designed for illumination, which typically are in the range of 5–20 MHz [86,87], and achieved a data rate of 190 Mbps, limited by the receiver used. In [85], the authors used a bundle of commercial fluorescent fibres aligned in a planar array. They demonstrated an optical gain of 12.3, with a bandwidth of 91 MHz, achieving a data rate of 2.36 Gbps. Interestingly, the authors demonstrated a concept of an omnidirectional antenna made out of fluorescent fibres. The importance of this is that it solves one of the bottlenecks in the practical mobile detector VLC application, since the signal can be detected at any incident angle.

Other authors have looked into whether nanostructures can be used to enhance the performance of fluorescent antennas. Dong et al. [88] used a nanopatterned fluorescent antenna to influence the direction of light propagation. They used a parabolic shaped fluorescent antenna with a specifically designed bottom layer with a nano-patterned diffraction grating. They showed experimentally that this nano-patterned approach improved the optical gain of the antenna from 2.2 to 3.2. Wang et al. [89] reported that arrays of metallic nanoparticles can act as étendue reducers. They have shown that an aluminium nanoparticle array can interact with dye molecules suspended in a polymer and change the angle distribution of the emission. Specifically, the emission is mostly confined into an 8° cone at the back side of the nanoparticle array. As a result, the emission can be more readily focused onto a detector. Their key reported finding was that the étendue of the emission is smaller than that of the incident light.

Other functionalities to the fluorescent antennas have recently been reported. Mulyawan et al. [90] have shown that fluorescent antennas can be used to implement a multiple-input and multiple-output (MIMO) scheme for VLC. A Fresnel lens was used to project two light sources transmitting data onto a very optically dense (high concentration of absorbing material) fluorescent antenna. Owing to attenuation of the fluorescence propagating through the device, the authors could reconstruct the initial information sent by the two channels from detectors attached to two different edges of the antenna. In a recent publication [91], Rae et al. demonstrated a VLC transceiver which has both receiving and transmitting capabilities. Their device was based on a fluorescent antenna with a transfer-printed micro-LED attached. As a result, this device not only could receive (downlink) VLC signals via the fluorescent antenna, but could also simultaneously transmit (uplink) through the micro-LED. Besides this dual functionality, this device could also operate in an optical relay mode, with the interesting possibility to establish a VLC connection between a transmitter and receiver which are not in direct line-of-sight. In a recent publication, Manousiadis et al. [92] have demonstrated that the fluorescent antennas could be used to implement wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) VLC scenarios. They have combined two fluorescent antennas, each of which was absorbing a different part of the visible spectrum. Their results show that successful WDM was possible by separating blue and green channels, with low interference. This a particularly interesting concept since it does not require the use of optical filters and thus allows to utilize the whole power of the incident light results in higher SNRs, along with the other benefits of fluorescent antennas: optical gain with wide field-of-view.

Fluorescent antennas constitute a new and a very promising approach to overcome the key limitation of link alignment in VLC applications. The motivation for their initial introduction was to provide an optical antenna which could provide usable gain, without limiting the field of view of the receiver to few degrees. Since their theoretical introduction, there have been a number of publications achieving impressive results in terms of both data rate and novel functionality.

6. Conclusion and future perspectives

This article has reviewed recent developments of various organic semiconductor devices for application in VLC. In the future, we can expect to see continued performance improvements in each type of device. We can also anticipate further advances that make full use of the distinctive properties of organic semiconductors, notably including their scope for flexibility and the opportunity to integrate many devices side by side. This is particularly relevant to future implementations supporting the Internet-of-things (IoT).

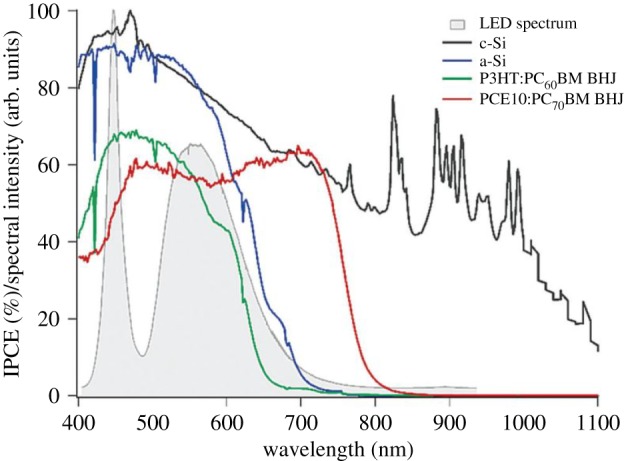

The concept of IoT is the extension of Internet connectivity into everyday objects. This will allow things to communicate with each other for automation, and be remotely monitored and controlled [93–96]. VLC can provide solutions for fast, interference-free and secure communication for IoT, leading to a world of interconnected devices, smart homes, environmental monitoring and display-to-display or even car-to-car communications. However, to realize the full potential of IoT with stand-alone objects, there remains a major obstacle. In many IoT scenarios, numerous sensors are required which cannot be connected to the electrical grid, but must have power autonomy. These sensors must be powered both to undertake their sensing function and for transmitting and receiving data. The exciting development by Yoshida et al. [67] to demonstrate simultaneous power and data harvesting in inorganic solar cells may help solve this challenge. As mentioned above, this approach is also possible with organic solar cells, which would be particularly suitable for integration into smart sensors. The spectral response of OPVs is better matched to indoor lighting than silicon (figure 9) [97], making OPV a highly compelling technology for indoor energy harvesting.

Figure 9.

Incident photon to collected electron conversion efficiency for the following devices: crystalline silicon (c-Si), amorphous silicon (a-Si), P3HT:PC60BM bulk heterojunction (P3HT:PC60BM BHJ) and PCE10:PC70BM bulk heterojunction (PCE10:PC70BM BHJ) devices. Also shown is the emission spectrum of a commercial white LED light. Adapted from [97] Copyright © 2016, The Royal Society of Chemistry. (Online version in colour.)

The tremendous recent developments in manufacturing OLED televisions and smartphone mean it should be possible to make complex arrays of OLEDs or OPVs dedicated to VLC. These could provide a platform for spatial and wavelength multiplexing, multiplying currently achievable data rates. Another development associated with the production process of organic devices is the integration of different devices either side-by-side [91] or devices that have dual functionality [75]. This could lead to a new generation of low-cost, purpose-built devices for VLC applications [98]. Overall, we see a bright future for organic devices in VLC application, and Gbps communication may not be too far away.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

P.P.M. wrote the first draft of the paper which was then revised and extended by the other authors.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the EPSRC for financial support for the programme/project from grants EP/R00689X/1, EP/R005281/1 EP/K00042X/I and EP/R0035164/1.

References

- 1.Godumala M, Choi S, Cho MJ, Choi DH. 2019. Recent breakthroughs in thermally activated delayed fluorescence organic light emitting diodes containing non-doped emitting layers. J. Mater. Chem. C 7, 2172–2198. ( 10.1039/C8TC06293E) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin Y, Li Y, Zhan X. 2012. Small molecule semiconductors for high-efficiency organic photovoltaics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 4245–4272. ( 10.1039/C2CS15313K) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka Y, Komine T, Haruyama S, Nakagawa M. 2003. Indoor visible light data transmission system utilizing white LED lights. IEICE Trans. Commun. 86, 2440–2454. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas H. 2011. Harald Haas: wireless data from every light bulb, TED.

- 5.Tsonev D, et al. 2014. A 3-Gb/s single-LED OFDM-based wireless VLC link using a gallium nitride μLED. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 26, 637–640. ( 10.1109/LPT.2013.2297621) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brien DCO, Zeng L, Le-Minh H, Faulkner G, Walewski JW, Randel S. 2008. Visible light communications: challenges and possibilities. In 2008 IEEE 19th Int. Symp. on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications, Cannes, France, 15–18 September, pp. 1–5. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE. ( 10.1109/PIMRC.2008.4699964) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanzo L, Haas H, Imre S, Brien DO, Rupp M, Gyongyosi L. 2012. Wireless myths, realities, and futures: from 3G/4G to optical and quantum wireless. Proc. IEEE 100, 1853–1888. ( 10.1109/JPROC.2012.2189788) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka Y, Haruyama S, Nakagawa M. 2000. Wireless optical transmissions with white colored LED for wireless home links. In 11th IEEE Int. Symp. on Personal Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications. PIMRC 2000. Proc. (Cat. No.00TH8525), London, UK, 18–21 September, pp. 1325–1329, vol. 1322 Piscataway, NJ: IEEE. ( 10.1109/PIMRC2000.881634) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haas H, Yin L, Wang Y, Chen C. 2016. What is LiFi? J. Lightwave Technol. 34, 1533–1544. ( 10.1109/JLT.2015.2510021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie R-J, Mitomo M, Uheda K, Xu F.-F, Akimune Y. 2002. Preparation and luminescence spectra of calcium- and rare-earth (R=Eu, Tb, and Pr)-codoped α-SiAlON ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 85, 1229–1234. ( 10.1111/j.1151-2916.2002.tb00250.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheu JK, et al. 2003. White-light emission from near UV InGaN-GaN LED chip precoated with blue/green/red phosphors. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 15, 18–20. ( 10.1109/LPT.2002.805852) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krames MR, Shchekin OB, Mueller-Mach R, Mueller GO, Zhou L, Harbers G, Craford MG. 2007. Status and future of high-power light-emitting diodes for solid-state lighting. J. Display Technol. 3, 160–175. ( 10.1109/JDT.2007.895339) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahn YN, Kim KD, Anoop G, Kim GS, Yoo JS. 2019. Design of highly efficient phosphor-converted white light-emitting diodes with color rendering indices (R1−R15) ≥95 for artificial lighting. Sci. Rep. 9, 16848 ( 10.1038/s41598-019-53269-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie R.-J, Hirosaki N. 2007. Silicon-based oxynitride and nitride phosphors for white LEDs—a review. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 8, 588–600. ( 10.1016/j.stam.2007.08.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smet PF, Parmentier AB, Poelman D. 2011. Selecting conversion phosphors for white light-emitting diodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 158, R37–R54. ( 10.1149/1.3568524) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pust P, et al. 2014. Narrow-band red-emitting SrLiAl3N4]:Eu2+ as a next-generation LED-phosphor material. Nat. Mater. 13, 891–896. ( 10.1038/nmat4012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin CC, Liu R-S. 2011. Advances in phosphors for light-emitting diodes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2, 1268–1277. ( 10.1021/jz2002452) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chun H, et al. 2014. Visible light communication using a blue GaN μLED and fluorescent polymer color converter. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 26, 2035–2038. ( 10.1109/LPT.2014.2345256) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalid AM, Cossu G, Corsini R, Choudhury P, Ciaramella E. 2012. 1-Gb/s transmission over a phosphorescent white LED by using rate-adaptive discrete multitone modulation. IEEE Photon. J. 4, 1465–1473. ( 10.1109/JPHOT.2012.2210397) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z, Chen B, Rogach AL. 2017. Synthesis, optical properties and applications of light-emitting copper nanoclusters. Nanoscale Horiz. 2, 135–146. ( 10.1039/C7NH00013H) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun C-Y, et al. 2013. Efficient and tunable white-light emission of metal–organic frameworks by iridium-complex encapsulation. Nat. Commun. 4, 2717 ( 10.1038/ncomms3717) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui Y, Song T, Yu J, Yang Y, Wang Z, Qian G. 2015. Dye encapsulated metal-organic framework for warm-white LED with high color-rendering index. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 4796–4802. ( 10.1002/adfm.201501756) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim O-H, Ha S-W, Kim JI, Lee J-K. 2010. Excellent photostability of phosphorescent nanoparticles and their application as a color converter in light emitting diodes. ACS Nano 4, 3397–3405. ( 10.1021/nn100139e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stupca M, Nayfeh OM, Hoang T, Nayfeh MH, Alhreish B, Boparai J, AlDwayyan A, AlSalhi M. 2012. Silicon nanoparticle-ZnS nanophosphors for ultraviolet-based white light emitting diode. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 074313 ( 10.1063/1.4754449) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song W-S, Yang H. 2012. Efficient white-light-emitting diodes fabricated from highly fluorescent copper indium sulfide core/shell quantum dots. Chem. Mater. 24, 1961–1967. ( 10.1021/cm300837z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jang E-P, Song W-S, Lee K-H, Yang H. 2013. Preparation of a photo-degradation-resistant quantum dot–polymer composite plate for use in the fabrication of a high-stability white-light-emitting diode. Nanotechnology 24, 045607 ( 10.1088/0957-4484/24/4/045607) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J, Liu W, Mao L-H, Yin Y-J, Wang C-F, Chen S. 2014. Synthesis of silica-based carbon dot/nanocrystal hybrids toward white LEDs. J. Mater. Sci. 49, 7391–7398. ( 10.1007/s10853-014-8413-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou D, Zou H, Liu M, Zhang K, Sheng Y, Cui J, Zhang H, Yang B. 2015. Surface ligand dynamics-guided preparation of quantum dots–cellulose composites for light-emitting diodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 15 830–15 839. ( 10.1021/acsami.5b03004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heliotis G, Stavrinou PN, Bradley DDC, Gu E, Griffin C, Jeon CW, Dawson MD. 2005. Spectral conversion of InGaN ultraviolet microarray light-emitting diodes using fluorene-based red-, green-, blue-, and white-light-emitting polymer overlayer films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 103505 ( 10.1063/1.2039991) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heliotis G, Itskos G, Murray R, Dawson MD, Watson IM, Bradley DDC. 2006. Hybrid inorganic/organic semiconductor heterostructures with efficient non-radiative energy transfer. Adv. Mater. 18, 334–338. ( 10.1002/adma.200501949) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geffroy B, le Roy P, Prat C. 2006. Organic light-emitting diode (OLED) technology: materials, devices and display technologies. Polym. Int. 55, 572–582. ( 10.1002/pi.1974) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu E, Zhang HX, Sun HD, Dawson MD, Mackintosh AR, Kuehne AJC, Pethrick RA, Belton C, Bradley DDC. 2007. Hybrid inorganic/organic microstructured light-emitting diodes produced using photocurable polymer blends. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 031116 ( 10.1063/1.2431772) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Findlay NJ, Bruckbauer J, Inigo AR, Breig B, Arumugam S, Wallis DJ, Martin RW, Skabara PJ. 2014. An organic down-converting material for white-light emission from hybrid LEDs. Adv. Mater. 26, 7290–7294. ( 10.1002/adma.201402661) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sajjad MT, et al. 2015. Novel fast color-converter for visible light communication using a blend of conjugated polymers. ACS Photonics 2, 194–199. ( 10.1021/ph500451y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sajjad MT, et al. 2017. A saturated red color converter for visible light communication using a blend of star-shaped organic semiconductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 013302 ( 10.1063/1.4971823) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vithanage AD, et al. 2016. BODIPY star-shaped molecules as solid state colour converters for visible light communications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 013302 ( 10.1063/1.4953789) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leitao MF, Santos JMM, Guilhabert B, Watson S, Kelly AE, Islim MS, Haas H, Dawson MD, Laurand N. 2017. Gb/s visible light communications with colloidal quantum dot color converters. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 23, 1–10. ( 10.1109/JSTQE.2017.2690833) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vithanage DA, et al. 2017. Polymer colour converter with very high modulation bandwidth for visible light communications. J. Mater. Chem. C 5, 8916–8920. ( 10.1039/C7TC03787B) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, et al. 2018. Aggregation-induced emission luminogens as color converters for visible-light communication. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 34 418–34 426. ( 10.1021/acsami.8b05950) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laurand N, et al. 2012. Colloidal quantum dot nanocomposites for visible wavelength conversion of modulated optical signals. Opt. Mater. Express 2, 250–260. ( 10.1364/OME.2.000250) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang X, Shi M, Yu Y, Xie Y, Liang R, Ou Q, Chi N, Zhang S. 2018. Enhancing communication bandwidths of organic color converters using nanopatterned hyperbolic metamaterials. J. Light. Technol. 36, 1862–1867. ( 10.1109/JLT.2018.2793217) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mei S, Liu X, Zhang W, Liu R, Zheng L, Guo R, Tian P. 2018. High-bandwidth white-light system combining a micro-LED with Perovskite quantum dots for visible light communication. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 5641–5648. ( 10.1021/acsami.7b17810) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang CW, VanSlyke SA. 1987. Organic electroluminescent diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 51, 913–915. ( 10.1063/1.98799) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burroughes JH, Bradley DDC, Brown AR, Marks RN, Mackay K, Friend RH, Burns PL, Holmes AB. 1990. Light-emitting diodes based on conjugated polymers. Nature 347, 539–541. ( 10.1038/347539a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi S, Kwon S, Kim H, Kim W, Kwon JH, Lim MS, Lee HS, Choi KC. 2017. Highly flexible and efficient fabric-based organic light-emitting devices for clothing-shaped wearable displays. Sci. Rep. 7, 6424 ( 10.1038/s41598-017-06733-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carey T, et al. 2017. Fully inkjet-printed two-dimensional material field-effect heterojunctions for wearable and textile electronics. Nat. Commun. 8, 1202 ( 10.1038/s41467-017-01210-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park S, et al. 2018. Self-powered ultra-flexible electronics via nano-grating-patterned organic photovoltaics. Nature 561, 516–521. ( 10.1038/s41586-018-0536-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bansal AK, Hou S, Kulyk O, Bowman EM, Samuel ID. W. 2015. Wearable organic optoelectronic sensors for medicine. Adv. Mater. 27, 7638–7644. ( 10.1002/adma.201403560) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chaleshtori ZN, Chvojka P, Zvanovec S, Ghassemlooy Z, Haigh PA. 2018. A survey on recent advances in organic visible light communications. In 2018 11th Int. Symp. on Communication Systems, Networks & Digital Signal Processing (CSNDSP), Budapest, Hungary, 18–20 July, pp. 1–6. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE. (( 10.1109/CSNDSP.2018.8471788) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haigh PA, Ghassemlooy Z, Rajbhandari S, Papakonstantinou I. 2013. Visible light communications using organic light emitting diodes. IEEE Commun. Mag. 51, 148–154. ( 10.1109/MCOM.2013.6576353) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walzer K, Maennig B, Pfeiffer M, Leo K. 2007. Highly efficient organic devices based on electrically doped transport layers. Chem. Rev. 107, 1233–1271. ( 10.1021/cr050156n) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Friend RH, et al. 1999. Electroluminescence in conjugated polymers. Nature 397, 121–128. ( 10.1038/16393) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lochner CM, Khan Y, Pierre A, Arias AC. 2014. All-organic optoelectronic sensor for pulse oximetry. Nat. Commun. 5, 5745 ( 10.1038/ncomms6745) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee H, Kim E, Lee Y, Kim H, Lee J, Kim M, Yoo H-J, Yoo S. 2018. Toward all-day wearable health monitoring: an ultralow-power, reflective organic pulse oximetry sensing patch. Sci. Adv. 4, eaas9530 ( 10.1126/sciadv.aas9530) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park J.-S., Chae H, Chung HK, Lee SI. 2011. Thin film encapsulation for flexible AM-OLED: a review. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 26, 034001 ( 10.1088/0268-1242/26/3/034001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park J. 2010. Speedup of dynamic response of organic light-emitting diodes. J. Lightwave Technol. 28, 2873–2880. ( 10.1109/JLT.2010.2069552) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zvanovec S, Chvojka P, Haigh PA, Ghassemlooy Z. 2015. Visible light communications towards 5G. Radioengineering 24, 1–9. ( 10.13164/re.2015.0001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Minh HL, Ghassemlooy Z, Burton A, Haigh PA. 2011. Equalization for organic light emitting diodes in visible light communications. In 2011 IEEE GLOBECOM Workshops (GC Wkshps), pp. 828–832. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haigh PA, Ghassemlooy Z, Le Minh H, Rajbhandari S, Arca F, Tedde SF, Hayden O, Papakonstantinou I.. 2012. Exploiting equalization techniques for improving data rates in organic optoelectronic devices for visible light communications. J. Lightwave Technol. 30, 3081–3088. ( 10.1109/JLT.2012.2210028) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haigh PA, Ghassemlooy Z, Papakonstantinou I. 2013. 1.4-Mb/s white organic LED transmission system using discrete multitone modulation. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 25, 615–618. ( 10.1109/LPT.2013.2244879) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haigh PA, Ghassemlooy Z, Papakonstantinou I, Minh HL. 2013. 2.7 Mb/s with a 93-kHz white organic light emitting diode and real time ANN equalizer. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 25, 1687–1690. ( 10.1109/LPT.2013.2273850) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Le ST, et al. 2014. 10 Mb/s visible light transmission system using a polymer light-emitting diode with orthogonal frequency division multiplexing. Opt. Lett. 39, 3876–3879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haigh PA, Bausi F, Ghassemlooy Z, Papakonstantinou I, Le Minh H, Fléchon C, Cacialli F.. 2014. Visible light communications: real time 10 Mb/s link with a low bandwidth polymer light-emitting diode. Opt. Express 22, 2830–2838. ( 10.1364/OE.22.002830) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Haigh PA, et al. 2014. A 20-Mb/s VLC link with a polymer LED and a multilayer perceptron equalizer. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 26, 1975–1978. ( 10.1109/LPT.2014.2343692) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haigh PA, Bausi F, Minh HL, Papakonstantinou I, Popoola WO, Burton A, Cacialli F. 2015. Wavelength-multiplexed polymer LEDs: towards 55 Mb/s organic visible light communications. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 33, 1819–1828. ( 10.1109/JSAC.2015.2432491) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen H, Xu Z, Gao Q, Li S. 2018. A 51.6 Mb/s experimental VLC system using a monochromic organic LED. IEEE Photonics J. 10, 1–12. ( 10.1109/JPHOT.2017.2748152) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoshida K, et al. In press 245 MHz bandwidth organic light-emitting diodes used in a gigabit optical wireless data link. Nature Comm. ( 10.1038/s41467-020-14880-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arredondo B, Romero B, Pena JM. S., Fernández-Pacheco A, Alonso E, Vergaz R, De Dios C.. 2013. Visible light communication system using an organic bulk heterojunction photodetector. Sensors 13, 12 266–12 276. ( 10.3390/s130912266) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vega-Colado C, et al. 2018. An all-organic flexible visible light communication system. Sensors 18, 3045 ( 10.3390/s18093045) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peumans P, Bulović V, Forrest SR. 2000. Efficient, high-bandwidth organic multilayer photodetectors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 3855–3857. ( 10.1063/1.126800) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morimune T, Kajii H, Ohmori Y. 2006. Photoresponse properties of a high-speed organic photodetector based on copper–phthalocyanine under red light illumination. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 18, 2662–2664. ( 10.1109/LPT.2006.887786) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ohmori Y, Hamasaki T, Kajii H, Morimune T. 2009. Organic photo sensors operating at high speed utilizing poly(9,9-dioctylfluorene) derivative and fullerene derivative fabricated by solution process. In SPIE. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hamasaki T, Morimune T, Kajii H, Minakata S, Tsuruoka R, Nagamachi T, Ohmori Y. 2009. Fabrication and characteristics of polyfluorene based organic photodetectors using fullerene derivatives. Thin Solid Films 518, 548–550. ( 10.1016/j.tsf.2009.07.123) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tsai W-W, Chao Y-C, Chen E-C, Zan H-W, Meng H-F, Hsu C-S. 2009. Increasing organic vertical carrier mobility for the application of high speed bilayered organic photodetector. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 213308 ( 10.1063/1.3263144) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang S, Tsonev D, Videv S, Ghosh S, Turnbull GA, Samuel IDW, Haas H. 2015. Organic solar cells as high-speed data detectors for visible light communication. Optica 2, 607–610. ( 10.1364/OPTICA.2.000607) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Winston R, Miñano JC, Benitez PG. 2005. Nonimaging optics. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Winston R. 1970. Light collection within the framework of geometrical optics. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 60, 245–247. ( 10.1364/JOSA.60.000245) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Welford WT, Winston R.. 1978. Optics of nonimaging concentrators. Light and solar energy.

- 79.Ries H. 1982. Thermodynamic limitations of the concentration of electromagnetic radiation. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 72, 380–385. ( 10.1364/JOSA.72.000380) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smestad G, Ries H, Winston R, Yablonovitch E. 1990. The thermodynamic limits of light concentrators. Sol. Energy Mater. 21, 99–111. ( 10.1016/0165-1633(90)90047-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Collins S, O'Brien DC, Watt A. 2014. High gain, wide field of view concentrator for optical communications. Opt. Lett. 39, 1756–1759. ( 10.1364/OL.39.001756) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Batchelder JS, Zewai AH, Cole T. 1979. Luminescent solar concentrators. 1: Theory of operation and techniques for performance evaluation. Appl. Opt. 18, 3090–3110. ( 10.1364/AO.18.003090) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Batchelder JS, Zewail AH, Cole T. 1981. Luminescent solar concentrators. 2: Experimental and theoretical analysis of their possible efficiencies. Appl. Opt. 20, 3733–3754. ( 10.1364/AO.20.003733) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Manousiadis PP, et al. 2016. Wide field-of-view fluorescent antenna for visible light communications beyond the étendue limit. Optica. 3, 702–706. ( 10.1364/OPTICA.3.000702) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Peyronel T, Quirk KJ, Wang SC, Tiecke TG. 2016. Luminescent detector for free-space optical communication. Optica 3, 787–792. ( 10.1364/OPTICA.3.000787) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Grubor J, Lee SCJ, Langer KD, Koonen T, Walewski JW. 2007. Wireless high-speed data transmission with phosphorescent white-light LEDs. In 33rd European Conf. and Exhibition of Optical Communication—Post-Deadline Papers (published 2008), pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chun H, Rajbhandari S, Faulkner G, Brien DO. 2014. Effectiveness of blue-filtering in WLED based indoor visible light communication. In 2014 3rd Int. Workshop in Optical Wireless Communications (IWOW), pp. 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dong Y, et al. 2017. Nanopatterned luminescent concentrators for visible light communications. Opt. Express 25, 21 926–21 934. ( 10.1364/OE.25.021926) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang S, Le-Van Q, Peyronel T, Ramezani M, Van Hoof N, Tiecke TG, Gómez Rivas J.. 2018. Plasmonic nanoantenna arrays as efficient Etendue reducers for optical detection. ACS Photonics 5, 2478–2485. ( 10.1021/acsphotonics.8b00298) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mulyawan R, et al. 2017. MIMO visible light communications using a wide field-of-view fluorescent concentrator. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 29, 306–309. ( 10.1109/LPT.2016.2647717) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rae K, et al. 2018. Transfer-printed micro-LED and polymer-based transceiver for visible light communications. Opt. Express 26, 31 474–31 483. ( 10.1364/OE.26.031474) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Manousiadis PP, et al. 2019. Optical antennas for wavelength division multiplexing in visible light communications beyond the étendue limit. Adv. Opt. Mater. 1901139 ( 10.1002/adom.201901139) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kopetz H. 2011. Internet of things. In Real-time systems: design principles for distributed embedded applications, pp. 307–323. Boston, MA: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gubbi J, Buyya R, Marusic S, Palaniswami M. 2013. Internet of Things (IoT): a vision, architectural elements, and future directions. Future Gener. Comp. Syst. 29, 1645–1660. ( 10.1016/j.future.2013.01.010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zanella A, Bui N, Castellani A, Vangelista L, Zorzi M. 2014. Internet of Things for smart cities. IEEE Internet of Things J. 1, 22–32. ( 10.1109/JIOT.2014.2306328) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wortmann F, Flüchter K. 2015. Internet of things. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 57, 221–224. ( 10.1007/s12599-015-0383-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cutting CL, Bag M, Venkataraman D. 2016. Indoor light recycling: a new home for organic photovoltaics. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 10 367–10 370. ( 10.1039/C6TC03344J) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tippenhauer NO, Giustiniano D, Mangold S. 2012. Toys communicating with LEDs: enabling toy cars interaction. In 2012 IEEE Consumer Communications and Networking Conference (CCNC), pp. 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hamamatsu photonics K.K., s. s. d. 2015. Si photodiodes. S1336 series.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.