Abstract

This article reviews the anatomy and physiology of the uterine circulation, with emphasis on the remodeling of spiral arteries during normal pregnancy, and the timing and anatomical pathways of trophoblast invasion of the spiral arteries. We review the definitions of the placental bed and basal plate of the placenta, their relevance to the study of the physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries, as well as the methods to obtain and examine placental bed biopsy specimens. We also examine the role of the extravillous trophoblast in normal and abnormal pregnancies, and the criteria used to diagnose failure of physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries. Finally, we comment on the use of uterine artery Doppler velocimetry as a surrogate marker of chronic uteroplacental ischemia.

Keywords: atherosis, immunohistochemistry, impedance to blood flow, integrin, physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries, placental bed

1. Anatomy and physiology of the uterine circulation:

The blood supply of the uterus is provided by the uterine and ovarian arteries [102]. After entering the myometrium, the uterine arteries give rise to the “arcuate arteries,” which branch into the “radial arteries” [102]. The radial arteries divide into the “basal arteries,” which supply the basal portion of the endometrium (critical for endometrial regeneration after menstruation) and the “spiral arteries,” which continue toward the endometrial surface [95]. The term “spiral arteries” reflects the coiled appearance of these vessels, whose role is to supply blood to the upper functional layer of the endometrium, thought to be shed during menstruation [95]. The spiral arteries branch into a subepithelial capillary plexus [95]. Markee reported that each spiral artery supplies approximately 4–9 mm2 of endometrial surface [71]. Blood from the intervillous space is drained through the utero-placental veins, whose openings are on the floor of the intervillous space. The venous endothelium lines part of the floor of the intervillous space floor [62]. The uteroplacental veins undergo less dramatic changes than the arteries. Trophoblast may or may not invade the venous wall, even though free-floating endoluminal trophoblast have been found in these vessels [36].

Endometrial bleeding during menstruation and hemostasis:

The endometrium has evolved to meet the needs of menstruation, implantation, placentation, as well as post-partum hemostasis. The specific mechanisms responsible for endometrial bleeding (during menstruation) and hemostasis (after menstruation) are relevant to the study of pregnancy, since uterine bleeding during pregnancy (i.e., hemostatic failure) is a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcome [75, 101].

The current understanding of the vascular changes that occur during menstruation is based upon classic physiologic studies conducted by Markee, who examined the behavior of the endometrium from rhesus monkeys implanted into the anterior chamber of the eye of non-human primates [71]. The explants underwent a reduction in size of 25–75%, 2–6 days before the onset of bleeding. The spiral arteries became more coiled, and blood flow either slowed down or came to a complete stop. Red blood cells were reported not to move for 60–90 seconds [71]. Menstrual bleeding was considered to occur when vessel vasodilated after a period of intense vasoconstriction. Five mechanisms were proposed to account for the bleeding: 1) blood could pass through a damaged arteriole and form a hematoma, which would then rupture into the uterine cavity; 2) blood would pass directly from a ruptured arteriole into the uterine cavity; 3) red blood cells would extravasate by crossing the wall of the arterioles; 4) venous bleeding, which may occur either through the damaged venous wall or drainage following extravasation from arterioles; and 5) secondary bleeding may happen following violent movement. Markee proposed that 75% of bleeding derived from arterioles, and 25% from the venules. Cessation of bleeding is thought to be due to vasoconstriction [71].

The fact that menstrual fluid generally does not clot [94] should not be taken as an indication that coagulation is not important for uterine hemostasis. For instance, patients with Von Willebrand disease have excessive menstrual blood loss [29]. During normal menstruation, platelets and fibrin plugs are formed within the lumen of the spiral vessels [23]. Consumption of platelets and fibrinogen is thought to result in decreased concentrations of platelets and fibrinogen in menstrual fluid [28]. Lockwood et al. proposed that tissue factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) are implicated in both decidual hemostasis during implantation and bleeding during menstruation [67]. Tissue factor would induce coagulation and prevent hemorrhage during implantation, while PAI-1 would prevent extracellular matrix degradation and fibrinolysis. At the end of the menstrual cycle, progesterone withdrawal would reduce tissue factor and PAI-1 production and facilitate menstruation [67].

2. Changes in the uterine circulation during pregnancy:

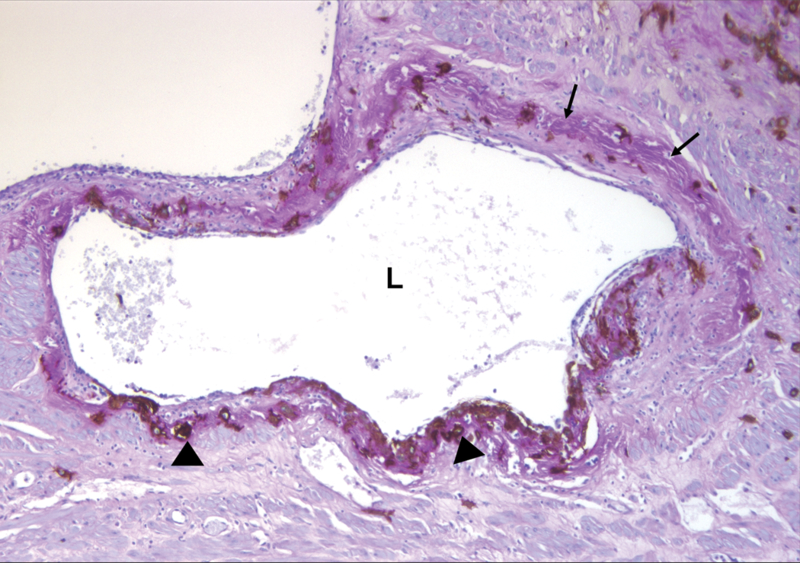

The spiral arteries in the placental bed are normally transformed into large dilated vessels undergoing dramatic structural changes in their vessel wall. The spiral arteries are also known as the utero-placental arteries [16]. The terms “physiologic changes” or “physiologic transformation” of the spiral arteries were first introduced by Brosens, Robertson and Dixon in 1967 to emphasize that these changes were part of normal pregnancy. The key findings of physiologic transformation are: 1) dilatation of the lumen; 2) trophoblast invasion of the vessel wall, which includes both the media and endothelium; and 3) replacement of the muscular and elastic tissue of the arterial wall by a thick layer of fibrinoid material that generally stains positive on Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) staining [16] (Figure 1). Brosens et al. proposed that these structural changes, particularly the destruction of muscle in the media, would lead to loss in vasomotor control [16]. Collectively, these changes are thought to maximize the delivery of maternal blood to the intervillous space by making the arterial lumen wider as well as reducing the responsiveness of these vessels to vasoconstrictor agents. Invasion of the utero-placental veins has been implicated as a mechanism responsible for the lateral placental growth [25]. Much less is known, however, about changes in the morphology of the utero-placental veins [36].

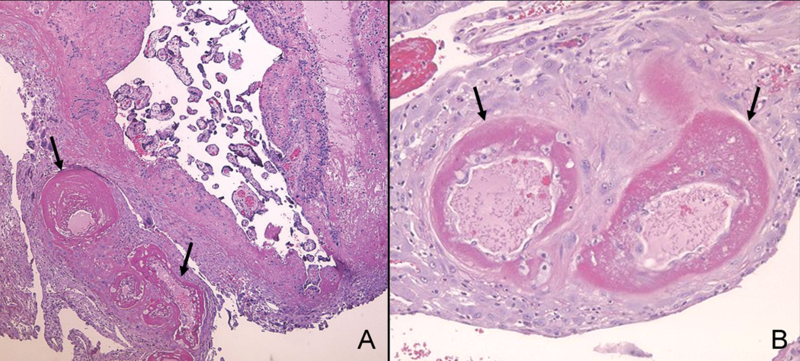

Figure 1. Microscopic demonstration of physiologic transformation of myometrial segement of the spiral artery in normal pregnancy at term.

Placental bed biopsy specimen was immunostained for cytokeratin-7 to locate trophoblasts (arrowheads) infiltrating the arterial wall, and additional Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) staining was performed to identify fibrinoid (arrows). Spiral arterial lumen is dilated, and fibrinoid replaces the media and intima. L: spiral arterial lumen (Cytokeratin 7-PAS staining, X100).

3. Timing and anatomical pathways of trophoblast invasion of the spiral arteries:

Robertson et al. [86] and Pijnenborg et al. [82] proposed that trophoblast invasion occurs in two stages: 1) the transformation of the decidual segment of the spiral arteries by a “wave” of endovascular trophoblast migration in the first trimester; and 2) the transformation of the myometrial segments of the spiral arteries in the second trimester [82, 86]. In 1972, Brosens and colleagues [17] reported that in patients with preeclampsia and SGA, the physiologic transformation of spiral arteries is limited to the decidual segment of the uteroplacental arteries, and Robertson proposed that this process is due to inhibition of the second “wave” of endovascular trophoblast migration that occurs from about 16 weeks onwards [51]. However, Lyall et al. have concluded that morphological evidence of this proposal is unclear and that the molecular mechanisms to control such a process would be very complex [68]. Moreover, recent studies have suggested that trophoblast invasion of the spiral arteries is a continuous process [68, 69].

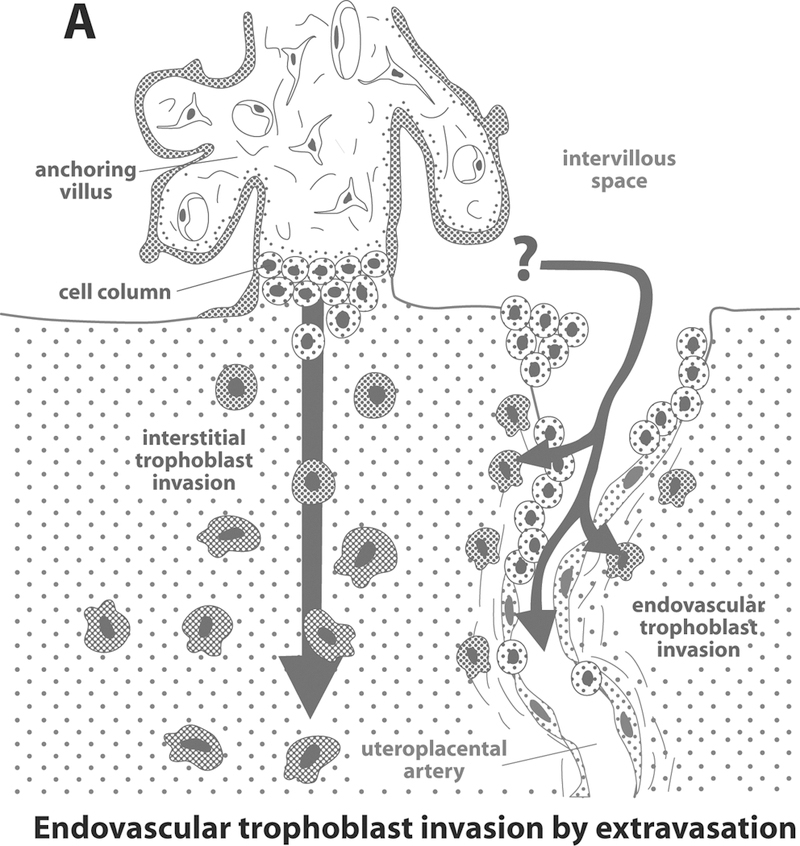

The anatomic pathways taken by the endovascular trophoblast (either the extravasation or intravasation model) have also been a matter of controversy [48]. The extravasation model, which is based on animal studies, proposes that trophoblast cells gain access to the uteroplacental arterial lumen via the point of entrance to the intervillous space, or close to it [48]. Thereafter, the cells migrate along the arterial lumen retrograde to the blood flow by adhering to and replacing the endothelium, forming intraluminal trophoblastic plugs. Some of these cells were thought to leave the arterial lumen and invade the media as well as adventitia (Figure 2A) [8, 48, 82, 83]. In contrast, the intravasation model is based on studies in human tissues and proposes that endovascular trophoblast represents differentiated interstitial trophoblast (Figure 2B) [27, 34, 48]. According to this model, the trophoblast invades the arterial wall from the surrounding junctional zone and migrates inside the arterial lumen [27, 34, 48]. More recently, a combination of both hypotheses was proposed by Kam et al. [47].

Figure 2. Intravasation (Figure 2A) and extravasation (Figure 2B) routes trophoblast invasion.

Reproduced with permission from Kaufmann P et al. Biology of Reproduction 2003; 69: 1–7.

4. Number and location of spiral arteries supplying the placental bed:

A comprehensive assessment of the vascular supply to the placental bed can only be determined by examination of cesarean section hysterectomy specimens. Indeed, Ivo Brosens studied 15 cesarean section hysterectomy specimens, including 3 cases in which the placenta had been left in situ. He estimated that there were 120 arterial openings in the placental bed, with each artery containing only one opening into the intravillous space [15]. However, the estimates have ranged widely in studies reported during the past century [36]. The number of arteries and openings in the placental bed has been the subject of disagreement. Some investigators report more openings than arteries, while others propose that the number of openings equals that of utero-placental arteries. Moreover, other investigators have emphasized the difficulty in distinguishing arterial from venous openings [36]. The density of the spiral artery opening at term varies from 0.5 to 1 per centimeter square [36]. Brosens et al. reported that spiral artery openings are topographically adjacent to the placental septae, and 96% of spiral arteries from normal pregnancies have findings of physiologic transformation. Spiral arteries in the center of the placenta are more likely to have physiologic transformation than those located on the periphery [16].

5. Definition of placental bed and basal plate

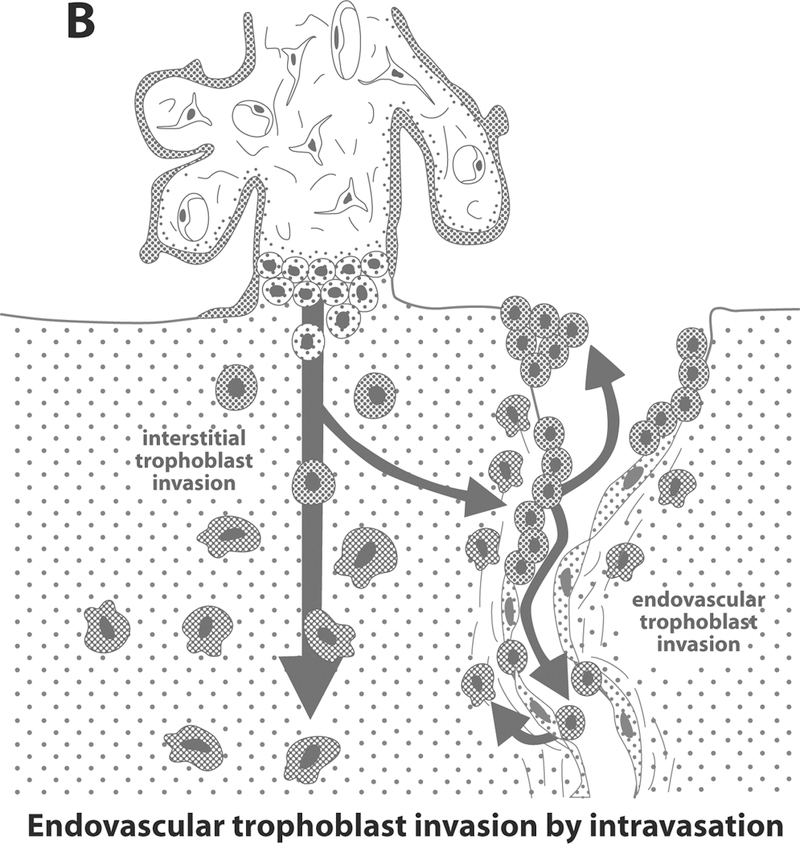

The term “placental bed” refers to part of the uterus (decidua and myometrium) lying underneath the placental insertion site [36]. The maternal-fetal junction comprises the basal plate of the placenta, which is composed of the tissues normally detached with the placenta and the placental bed, which is what is left in the uterus (Figure 3) [36]. The term “placental bed” should not be confused with the “basal plate of the placenta,” which is the floor of the intervillous space. Its surface is visible with the naked eye on the maternal surface of the placenta, and it is composed of the part of the maternal-fetal junction adhering to the delivered placenta [7].

Figure 3. Microscopic feature of fetomaternal junction (basal plate and placental bed) showing the distal end of the spiral artery (arrows) emptying into the intervillous space (IVS).

Inset shows a longitudinally running spiral arterial segment at a lower magnification. BP: basal plate, CV: chorionic villi, M: myometrium (Cytokeratin 7-PAS, X40 and X100).

6. Methodologies to obtain placental bed biopsy specimens:

A comprehensive and accurate study of the placental bed requires access to the post-partum uterus, knowledge of the site of placental implantation, and systematic sectioning of the specimen. Cesarean section hysterectomy specimens were used several decades ago to gain understanding about the microscopic morphology of the placental bed. However, these operations, once performed as a method of sterilization, are no longer in use, as the morbidity associated with the procedure is higher than that of other sterilization techniques (e.g., tubal ligation). Thus, uteri for these types of studies become available generally in the instance of post-partum hemorrhage refractory to medical and surgical maneuvers (e.g., uterine artery ligation), or when hysterectomy is clinically indicated (such as early cervical or ovarian cancer diagnosed during pregnancy or after maternal death). The underlying pathology, which was the indication for hysterectomy, introduces potential biases in these studies. For example, some patients with intractable post-partum hemorrhage to conventional treatment may have placenta accreta, and to consider them representative of a physiologic state may not be appropriate.

Dixon and Robertson introduced in 1958 a new technique for obtaining tissue in order to study the placental bed at the time of cesarean section. They called this technique a “placental bed biopsy” [31]. The authors were clear in understanding that the biopsy specimen had to include not only the decidua but also the myometrium [31], since the pathology observed in preeclampsia consisted of failure of physiologic transformation of the myometrial segment of the spiral arteries. This technique has been used extensively to study the placental bed in patients with complications of pregnancy [37, 87]. Robertson et al. published a review of the experience of placental bed biopsies from three European centers and concluded that the technique was safe, and contributed to the understanding of the biology of this interface [87]. An important limitation of placental bed biopsies is the potential for sampling problems. The number of vessels present in one biopsy is limited and the biopsy may not be representative of the lesions present in the entire uterus. Obtaining a placental bed biopsy can be carried out either at the time of cesarean section or by using a transvaginal method under ultrasound guidance.

6.1. Transabdominal placental bed biopsies:

The transabdominal approach is used at the time of cesarean section. It is of the utmost importance that the placental location be determined by ultrasound examination immediately before the procedure and then recorded. Robertson et al. recommended that the surgeon identifies the true center of the placenta, which may not be underneath the umbilical cord insertion [87]. One approach is to deliver the uterus during the cesarean section after delivery of the fetus, identify the placental center, and place the digit of one of the operators on the serosal surface of the uterus. The placenta is then delivered and the biopsy taken from this place. Robertson et al. recommended taking biopsies of 1.5 cm in diameter [87]. The specimen needs to contain myometrium; this is easily achieved, as only a few millimeters of depth (5mm) would include this tissue [87]. When the placenta is implanted in the fundus, biopsies are difficult to obtain. In this case, after uterine contraction, reaching the proper site for the biopsy may not be possible

The instruments used for the biopsy could be a curved scissors and a scalpel. It is recommended that non-toothed forceps be employed in order to avoid crushing the specimen [87]. Another alternative is to use dermatologic punch biopsies, as they provide an easy method to standardize the procedure. Robertson et al. indicated that an experienced individual using this technique can sample the true placental bed in 70% of cases [87]. Hemostasis may sometimes be required, and this can be accomplished by placing absorbable sutures.

6.2. Transvaginal approach:

The first transvaginal approach, reported in 1981, consisted of introducing forceps through the cervix after delivery of the placenta to obtain placental bed biopsies [37]. This procedure was subsequently modified by Michel et al., who performed ultrasound examinations to determine the location of the placenta, The authors used cervical biopsy forceps under ultrasound guidance to sample the placental bed in women who were diagnosed with a blighted ovum (or anembryonic pregnancies) and underwent first trimester termination of pregnancy [72]. Khong et al. were successful in retrieving placental bed biopsies using curettage under ultrasound guidance in patients with spontaneous abortions [52]. Robson et al. modified this technique and reported that placental bed biopsies (containing a spiral artery in 50% of cases) could be obtained using a transvaginal approach. The forceps they employed were 310 mm long, with a 5mm-wide moveable jaw with a cutting adage. The goal was to take four biopsy specimens from each case. This procedure was attempted in first trimester terminations of pregnancy (n=201), missed abortions (n=104), cesarean sections at term (n=95), and after a vaginal delivery (n=13) [88]. Overall, in 67% (281/417) of the cases, the placental bed was sampled, and in 55% at least one spiral artery was present. The authors did not encounter any significant complications attributable to the procedure [88].

7. Immunohistochemical evaluation of a placental bed biopsy:

The four key questions when examining a biopsy are: 1) Does the specimen come from the placental bed? 2) Does it contain more than one myometrial spiral artery? 3) Is there a physiologic transformation of the myometrial segment of the spiral arteries? and 4) Is there atherosis? Placental bed biopsies are generally fixed in formaline and then stained with cytokeratin 7 and PAS to answer these questions.

7.1. Does the specimen come from the placental bed?

Evidence that the biopsy derives from the placental bed (rather than the non-placental bed or decidua parietalis) requires identification of interstitial trophoblast. Interstitial trophoblast may be difficult to distinguish from maternal cells in the decidua and basal plate [83]. Immunohistochemistry is therefore used to detect trophoblast. The most widely used antibody to accomplish this procedure is anti-human cytokeratin 7. This type of antibody recognizes epithelial cells (trophoblast has epithelial characteristics). In placental bed biopsy material, this antibody would identify both trophoblast cells and glandular epithelium of the endometrium. We have used anti-cytokeratin 7 (DAKO, OV-TL 12/30), which reacts with the 54kDA cytokeratin intermediate filament protein [26]. Cytokeratins are types of “intermediate filament proteins” belonging to a supergene family that includes tubulin polymers and actin microfilaments, and are part of the cytoskeleton and karyoskeleton of eukaryotic cells [40]. The term “intermediate” is used because their diameter (7–22 nm) is between that of actin (5–7 nm) and tubulin (22–25 nm) [40]. The anti-cytokeratin 7-specific antibody OV-TL 12/30 has been reported to be the only one that binds all trophoblast populations (and uterine glands) without any reactivity to mesenchymal stromal cells [11]. Thus, anti-cytokeratin 7 is considered to be the most useful antibody to identify trophoblast cells [56]. While the choice of marker to purify trophoblast in vitro is the subject of debate, there is general acceptance of the value of anti-cytokeratin 7 for histologic studies [11, 56].

7.2. Does the specimen contain one myometrial spiral artery?

Spiral arteries in the myometrium have a luminal diameter of approximately 200 μm (Boyd and Hamilton, 1970, cited in Frank et al. [36]). However, as the arteries travel through the decidua to the intervillous space, they widen and can attain a diameter of 500–1000 μm [91, 92]. Close to the ostia or the opening of the artery in the intervillous space, the diameter may reach 2000 μm [36]. Arteries with a lumen of <120 μm within the myometrium generally represent “basal” or straight arteries, and should not be confused with spiral arteries. Several decades ago, some authors proposed that the spiral arteries have a sphincteric mechanism close to the ostia to regulate the entry of blood into the intervillous space (Spanner 1935, Debiasi 1963, cited in Frank et al. [36]). Subsequent investigations [36] have disproved this concept. Biopsy specimens that have segments of a spiral artery within the decidua, but not the myometrium, are of limited value for the diagnosis of failure of physiologic transformation.

7.3. Is there physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries?

The characteristics of physiologic transformation include: 1) a dilated myometrial segment with a luminal diameter of greater than 120 μm; 2) infiltration of the vessel wall by trophoblast; 3) destruction of the media (i.e., smooth muscle and elastic tissue); and 4) fibrinoid deposition in the media, recognized as PAS positive material [16]. Therefore, physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries can be documented by staining the placental bed biopsy specimens with PAS and an anti-cytokeratin antibody (Figure 1).

7.4. Identification of fibrinoid:

The term “fibrinoid” has been used to refer to an acellular, homogeneous material, which binds to acid stains such as eosin and PAS. Two types of fibrinoid material have been identified: fibrin-type and matrix-type [49]. These subtypes cannot be distinguished with hematoxylin and eosin stain. However, matrix-type fibrinoid contains trophoblast cells, while fibrin-type does not [49]. With trichrome staining, fibrin-type fibrinoid stains red to orange, whereas the matrix-type has a blue to light-green appearance. Lang has also called attention to the usefulness of a modified paraldehyde fuchsin stain in differentiating two types of fibrinoids [61]. Fibrin-type stains green/orange, while matrix-type stains blue, violet, or green [49]. The type of fibrinoid found in the vessel wall is fibrin-type (Figure 1). Thought to be derived from the deposition of fibrin, the fibrin-type is therefore generated by activation of the coagulation cascade [49]. This observation is based upon immunohistochemistry studies demonstrating that the material stains with antibodies against fibrin, which do not cross-react with fibrinogen [42].

Physiological transformation of the spiral arteries is not an “all or none” phenomenon, as it may vary among spiral arteries in the same patient as well as within the same artery. In some of them, even the decidual segment is not transformed [51, 60], while in others the myometrial segments may be only partially transformed [51]. Thus, a more objective assessment of the degree of physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries may be achieved by referring to the proportion of the artery that is transformed in the placental bed biopsy specimens [53, 54]. Physiologic transformation is more likely at the center of the placental bed than on the periphery [15, 68, 87]. Therefore, the determination of the true center of the placenta, by ultrasound or during the cesarean section before the biopsy, may reduce sampling bias [87].

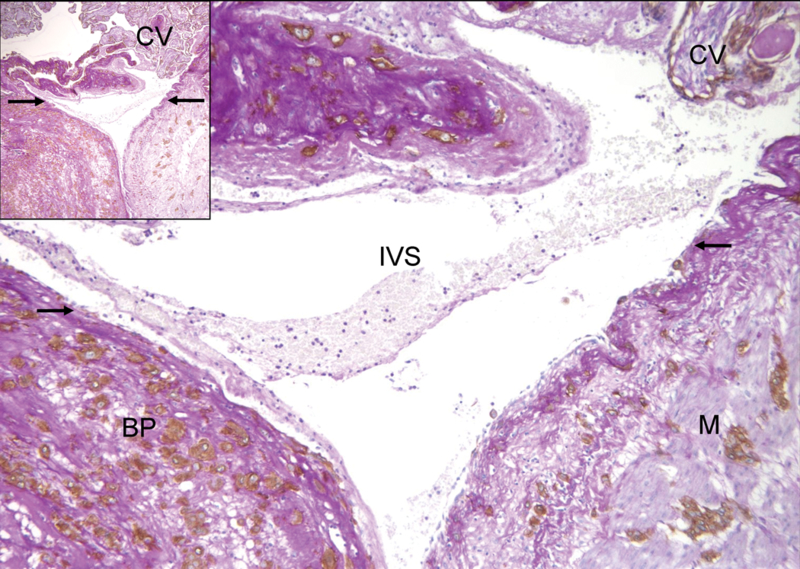

8. Is there atherosis?

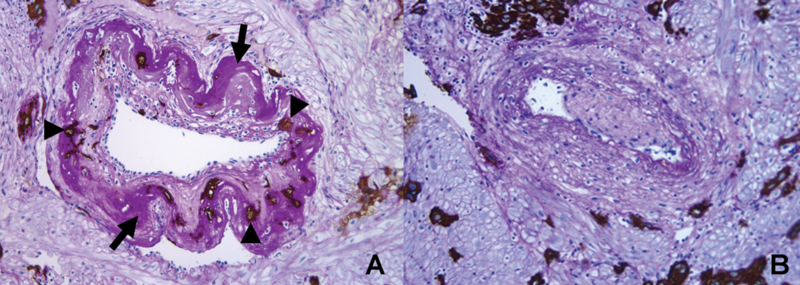

“Acute atherosis” of the spiral arteries was first described in 1945 by Herting in patients with preeclampsia [41]. The typical findings are: 1) fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall; 2) accumulation of lipid-laden macrophages in the vessel wall; and 3) a mononuclear perivascular infiltrate [85] (Figure 4). Sexton et al. coined the term “atherosis” [90] and reported that it could be observed in patients with chronic glomerulonephritis with super-imposed preeclampsia. However, Zeek and Assali subsequently proposed that the lesion was confined to preeclampsia [104]. Acute atherosis may be seen in the myometrial or decidual segments of the spiral arteries, and it is believed to occur only in vessels that have failed to undergo physiologic transformation (i.e., trophoblast invasion of the arterial wall). The lesion resembles those observed in atherosclerosis [100], and has been reported in other complications of pregnancy (such as growth restriction [50, 93], intrauterine fetal demise [52], diabetes mellitus [6, 57, 58], systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), discoid lupus erythematosus [2, 59], and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome [64, 76, 97]). The frequency of this lesion in the “great obstetrical syndromes” was recently described by Kim et al [55].

Figure 4. Atherosis of spiral arteries and decidual arterioles in the basal plate (A) and decidua of the fetal membrane (B), respectively.

Arrows indicate vessels affected by atherosis. The hallmark of atherosis is fibrinoid necrosis of the wall (arrows) and the presence of lipid-laden macrophages. (H&E, A: X40, B: X100)

9. The role of extravillous trophoblast invasion

9.1. Does decidual spiral artery remodeling begin before or after trophoblast invasion?

Several authors have proposed that maternal vessels may undergo changes before interstitial trophoblast invasion [14] (Harris and Ramsey 1966, Boyd and Hamilton 1970, as cited in Craven et al [24]). Craven et al. provided evidence that vasodilatation and some degree of vascular remodeling (expression of VCAM-1 by endothelial cells) could be detected in very early intrauterine pregnancies, in the endometrium of patients with ectopic gestations, as well as in the decidua parietalis of two patients who underwent hysterectomy at 5 and 11 weeks of gestation. The control group consisted of endometrial samples from patients in the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle. The authors suggested that the arterial changes observed in early pregnancy may be maternal responses associated with early endometrial decidualization [24].

Following these initial changes, further structural modifications have been described, such as reduction of the smooth muscle in the vascular media and deposition of fibrinoid material before infiltration of the media by trophoblast [48]. The trophoblast invasion of the arterial wall induces further dilation of the spiral arteries [48].

9.2. Invasion of extravillous trophoblast:

According to Kaufmann and Huppertz, the invasion of the extravillous trophoblast requires: 1) a source of proliferating cells; 2) expression of extracellular matrix receptors, which will facilitate adhesion of invasive cells to the extracellular matrix of the uterus; 3) the presence of invasive cells, which produce extracellular matrix; 4) matrix degrading enzymes to form channels in the uterine matrix for migration; 5) cellular motion; and 6) arrest of invasion.

9.2.1. Proliferation:

The stem cell for extravillous trophoblast invasion is considered to be attached to the basement membrane of anchoring villi. These cells stain positive for proliferation markers such as H thymidine, Ki67 (MIB-1), and antibodies against proliferating cell nuclear antigens (PCNA) and, thus, have a proliferative phenotype [9, 18] (Muhlhauser, 1993, Konsake, 1994, in Frank et al [36]). Upon departure from this location, cells abandon the cell cycle and acquire an invasive or migratory phenotype [36]. However, in pathologic conditions such as choriocarcinoma [103], ectopic pregnancy (Ketschanska, 1998, Kemp 1999 in Frank et al. [36]), and placenta accreta/percreta [36], invasive trophoblast retains its proliferative capacity. While this is easy to understand in the case of a neoplasia, the dissociation in ectopic pregnancy and placenta accreta suggests that factors intrinsic to the decidua play a role in altering the proliferative/migratory switch [36].

9.2.2. Integrin switch:

Cells interact with extracellular matrix components through a set of transmembrane proteins linking the cytoskeleton of the cell to the extracellular matrix components such as fibronectin, laminin, and collagen [4]. Integrins are a family of proteins that bind to their ligands with lower affinity (Ka 106-109 liter/mol) and are present in higher concentrations (10- to 100-fold) than receptors for hormones and other soluble signaling molecules [4]. These properties allow a cell to explore its environment without becoming irreversibly attached to it [4]. Integrins are important as they are the main molecules allowing cells to bind and respond to extracellular matrix. Integrins are formed by two non-covalently associated transmembrane glycoprotein subunits called alpha and beta. The matrix binding domain projects more than 2 0nm from the plasma membrane [4]. The intracellular end of the dimmers binds to the actin cytoskeleton (via proteins such as talin and alpha actininin) [12]. The functional importance of integrin bindings in trophoblast migration has been demonstrated through in vitro experiments in which blocking antibodies against integrins results in loss of trophoblast cell adhesion to extracellular matrix [45].

The following integrins have been detected in extravillous trophoblast [12]:

α3β1, which is the receptor for laminin;

α6β4, which binds to laminin and through it to collagen IV;

α5β1, a fibronectin receptor;

α1β1, a receptor for laminin and collagens I and IV;

αvβ3 and αvβ5, which are the receptors for vitronectin, as well as fibronectin and osteopontin.

The extravillous trophoblast in normal pregnancy undergoes a gradual switch from the proliferative to the invasive phenotype. This phenotypic change is also associated with a switch in integrin expression [36]. The extravillous trophoblast with proliferative phenotype, located on or close to the basal lamina of the anchoring villi, expresses predominantly α6β4 and, in part, α3β1 [36]. The integrin α6β4 is a laminin receptor that functions to anchor epithelial cells to the basal membrane [19]. This function may be aided by the long intracytoplasmatic tail of the subunit β4 [19]. Cells that express this integrin type also express proliferative markers, exhibit polar secretion of extracellular matrix or absence of visible matrix secretion, and do not have an invasive behavior [36]. In contrast, invasive trophoblast in the deciduas expresses interstitial integrins (such as α5β1, α1β1, αvβ3, and αvβ5), which bind to fibronectin, show apolar secretion of the extracellular matrix, and upregulate certain metalloproteinases (e.g., MMP-2, MMP-11) [36].

Inadequate trophoblast migration and shallow trophoblast invasion of the decidua and spiral arteries, as seen in preeclampsia, have been associated with failure to down-regulate the β4 integrin subunit and upregulate the α1 integrin [105]. This suggests that changes in the α6β4 and α1β1 integrins may be important in the trophoblast migration and invasion during pregnancy [19]. These findings, however, have not been confirmed by other studies [30].

9.2.3. The role of matrix degrading enzymes in trophoblast invasion:

Trophoblast invasion requires the degradation of extracellular matrix in the decidua and spiral arteries and the proximal third of the myometrium [38]. Proteolytic enzymes involved in the extracellular matrix degradation include serine proteases of the plasmin system [43, 74] and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [43, 98]. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that MMP-1 [43, 65], MMP-2 [10, 43], MMP-3 [43, 98], MMP-9 [43, 65], and its inhibitors TIMP-1 [43, 44] and TIMP-2 [43, 44] are present in the extravillous trophoblast.

9.2.4. Control of invasion:

Huppertz et al. have proposed that trophoblast invasion can be controlled by several mechanisms, including: 1) a change from a proliferative to an invasive phenotype. Unlike neoplastic cells, which proliferate and invade tissue, invasive trophoblast is not proliferative except under special circumstances (e.g., ectopic pregnancy and placenta accreta); 2) programmed cell death or apoptosis; 3) endoreduplication; and 4) syncytial fusion (personal communication). After delivery, trophoblast cells in the uterine wall undergo apoptosis generally within weeks. However, some trophoblast cells have been identified in hysterectomy specimens several years after pregnancy (personal communication). It is uncertain whether some trophoblast cells may persist for months or even years.

10. Failure of the physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries

10.1. Is interstitial trophoblast invasion “shallow” in preeclampsia?

Kadyrov et al. [46] reported a study in which the depth of trophoblast invasion was examined in hysterectomy specimens from patients with normal pregnancies, early-onset preeclampsia, and anemia. The depth of invasion was determined by identifying the endometrial-myometrial junction by actin staining (smooth muscle). Compared to normal pregnancies, trophoblast invasion was shallower in patients with preeclampsia and deeper in patients with anemia. In contrast, apoptosis was decreased in both anemia and preeclampsia [46]. Redline et al. proposed the diverging view that preeclampsia is associated with an excess in proliferative immature intermediate trophoblast [84].

10.2. Failure of physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries and pregnancy complications

Brosens and Robertson, using specimens from placental bed biopsies and cesarean hysterectomies, described that while physiological changes of the spiral arteries extended both to the decidual segment and 1/3 of the myometrial segment in normal pregnancy, the key feature of “failure of physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries” in preeclampsia was the lack of invasion of the trophoblasts into the spiral arteries of the myometrial segment [17] (Figure 5). Subsequent studies using specimens from cesarean hysterectomy from patients with preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction demonstrated that physiological transformation of the spiral arteries is not an “all or none” phenomenon and varies among spiral arteries in the same patient. In some spiral arteries from these patients, even the decidual segment was not transformed [51]. More recently, failure of physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries has also been reported in spontaneous abortion [52], placental abruption [32], preterm labor and intact membranes [53], as well as preterm PROM [54].

Figure 5. Comparison of transformed and non-transformed spiral arteries in the myometrium.

Contours of the two arteries are in stark contrast. (A) A transformed spiral artery is characterized by the presence of intramural trophoblasts (arrowheads) and fibrinoid degeneration (arrows) of the wall. (B) Absence of intramural trophoblasts, fibrinoid degeneration, and intact arterial contour mark spiral artery with failure of physiologic transformation (Cytokeratin 7-PAS, X200).

11. The relationship between Doppler of the uterine artery and “failure of physiologic transformation”

Failure of physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries in placental bed biopsies has been associated with high impedance to blood flow in the uterine arteries, as measured by Doppler velocimetry in patients with preeclampsia [1, 66, 79, 99], intrauterine growth restriction [1, 66, 70, 79], preterm labor with intact membranes, and preterm PROM [33].

Pulsed Doppler ultrasound has been utilized since its introduction by Campbell et al. [21] for the non-invasive assessment of impedance to blood flow in the uterine arteries [3, 5, 13, 22, 39, 63, 80, 81]. High impedance to blood flow in the uterine arteries between 20 and 24 weeks, defined as bilateral uterine artery notches and a pulsatility index or resistance index above the 95th percentile [3, 13, 39], has been associated with high risks of developing early-onset preeclampsia, delivering an SGA neonate, and perinatal death [3, 39, 63, 80]. Indeed, 80% of patients developing preeclampsia before 34 weeks [3, 39] (as opposed to only 27% of those who develop the disease after 34 weeks [3]) have a high impedance to blood flow in the uterine arteries between 22 and 24 weeks.

Bilateral diastolic notches in the uterine arteries represent very high impedance to blood flow.

Patients with bilateral notches in the Doppler waveform of the uterine arteries at 23–24 weeks are at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcome (preeclampsia, SGA, and perinatal death) [20]. Studies in which gelfoam has been used to embolize the uterine circulation in pregnant animals showed that the development of uterine artery notches are associated with high impedance to blood flow [77, 78]. Indeed, progressive embolization of the spiral arteries in pregnant animals produces a diastolic notch only when the uterine blood flow has been reduced to approximately one third, and the vascular resistance has been increased three to four times compared to its normal values [77, 78].

Longitudinal studies in uncomplicated pregnancies indicate that diastolic notches in uterine arteries disappear at 24 weeks of gestation [35, 89]. Therefore, persistence of uterine artery notches in the third trimester may indicate that high impedance to flow and the consequent uteroplacental ischemia are chronic in nature. The pathophysiology of the uterine artery diastolic notch is not completely understood. However, two theoretical computer models have been used to explain the physiopathology of uterine artery diastolic notches. Mo et al. proposed that the notch is the result of a wave reflection due to a high placental bed resistance [73]. In contrast, Talbert et al. put forward the idea that the uterine artery diastolic notch is due to increased arterial wall compliance [96]. During labor, there is a high impedance to blood flow in the uterine arteries. However, labor is not generally associated with uterine artery notches [96].

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the substantial contributions of Professor Peter Kaufmann of the University of Aachen, Germany, Professor John Kingdom of the University of Toronto, Professor Robert Pijnenborg of the University Leuven, Belgium, Professor Judith N. Bulmer of the University of Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom, and Professor Susan Fisher of University of California, San Francisco. Each of these distinguished scientists contributed to our interest in the study of the placental bed, visited the Perinatology Research Branch of NICHD and were generous with their ideas, talent and expertise. This review and other scientific work of our Branch would not have been possible without their guidance and the inspiration they provided to us.

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS.

Reference List

- 1.Aardema MW, Oosterhof H, Timmer A, van R, I, Aarnoudse JG: Uterine artery Doppler flow and uteroplacental vascular pathology in normal pregnancies and pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia and small for gestational age fetuses. Placenta 22 (2001) 405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramowsky CR, Vegas ME, Swinehart G, Gyves MT: Decidual vasculopathy of the placenta in lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 303 (1980) 668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albaiges G, Missfelder-Lobos H, Lees C, Parra M, Nicolaides KH: One-stage screening for pregnancy complications by color Doppler assessment of the uterine arteries at 23 weeks’ gestation. Obstet Gynecol 96 (2000) 559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Watson JD: Cell junctions, cell adhesion, and the extracellular matrix. In: Molecular biology of the cell. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arduini D, Rizzo G, Romanini C, Mancuso S: Utero-placental blood flow velocity waveforms as predictors of pregnancy-induced hypertension. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 26 (1987) 335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barth WH Jr., Genest DR, Riley LE, Frigoletto FD Jr., Benacerraf BR, Greene MF: Uterine arcuate artery Doppler and decidual microvascular pathology in pregnancies complicated by type I diabetes mellitus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 8 (1996) 98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benirschke K, Kaufmann P: Microscopic Survey In: Benirschke K and Kaufmann P: Pathology of the Human Placenta. Springer, Springer 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blankenship TN, Enders AC, King BF: Trophoblastic invasion and the development of uteroplacental arteries in the macaque: immunohistochemical localization of cytokeratins, desmin, type IV collagen, laminin, and fibronectin. Cell Tissue Res 272 (1993) 227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blankenship TN, King BF: Developmental expression of Ki-67 antigen and proliferating cell nuclear antigen in macaque placentas. Dev Dyn 201 (1994) 324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blankenship TN, King BF: Identification of 72-Kilodalton Type-Iv Collagenase at Sites of Trophoblastic Invasion of Macaque Spiral Arteries. Placenta 15 (1994) 177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blaschitz A, Weiss U, Dohr G, Desoye G: Antibody reaction patterns in first trimester placenta: implications for trophoblast isolation and purity screening. Placenta 21 (2000) 733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowen JA, Hunt JS: The role of integrins in reproduction. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine 223 (2000) 331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bower S, Schuchter K, Campbell S: Doppler ultrasound screening as part of routine antenatal scanning: prediction of pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth retardation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 100 (1993) 989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brettner A: On the behavior of the secondary wall of uteroplacental blood vessels during decidual reactions. Acta Anat (Basel) 57 (1964) 366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brosens IA: The Uteroplacental Vessels at Term - The Distribution and Extend of Physiological Changes. Trophoblast Research 3 (1988) 61 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brosens I, Robertson WB, Dixon HG: The physiological response of the vessels of the placental bed to normal pregnancy. J Pathol Bacteriol 93 (1967) 569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brosens IA, Robertson WB, Dixon HG: The role of the spiral arteries in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Annu 1 (1972) 177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulmer JN, Wells M, Bhabra K, Johnson PM: Immunohistological characterization of endometrial gland epithelium and extravillous fetal trophoblast in third trimester human placental bed tissues. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 93 (1986) 823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burrows TD, King A, Loke YW: Trophoblast migration during human placental implantation. Human Reproduction Update 2 (1996) 307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell S: The uteroplacental circulation--why computer modelling makes sense. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 6 (1995) 237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell S, Griffin DR, Pearce JM, Diazrecasens J, TE Cohenoverbeek, Willson K, Teague MJ: New Doppler Technique for Assessing Uteroplacental Blood-Flow. Lancet 1 (1983) 675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell S, Pearce JM, Hackett G, Cohen-Overbeek T, Hernandez C: Qualitative assessment of uteroplacental blood flow: early screening test for high-risk pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 68 (1986) 649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christiaens GC, Sixma JJ, Haspels AA: Morphology of haemostasis in menstrual endometrium. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 87 (1980) 425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craven CM, Morgan T, Ward K: Decidual spiral artery remodelling begins before cellular interaction with cytotrophoblasts. Placenta 19 (1998) 241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craven CM, Zhao L, Ward K: Lateral placental growth occurs by trophoblast cell invasion of decidual veins. Placenta 21 (2000) 160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DAKO: Specification sheet: monoclonal mouse, anti-human cytokeratin 7, clone OV-TL 12/30. (2000) (Pamphlet) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damsky CH, Fitzgerald ML, Fisher SJ: Distribution patterns of extracellular matrix components and adhesion receptors are intricately modulated during first trimester cytotrophoblast differentiation along the invasive pathway, in vivo. J Clin Invest 89 (1992) 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Merre LJ, Moss JD, Pattison DS: The hematologic study of menstrual discharge. Obstet Gynecol 30 (1967) 830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dilley A, Drews C, Miller C, Lally C, Austin H, Ramaswamy D, Lurye D, Evatt B: von Willebrand disease and other inherited bleeding disorders in women with diagnosed menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol 97 (2001) 630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Divers MJ, Bulmer JN, Miller D, Lilford RJ: Beta-1 Integrins in 3Rd-Trimester Human Placentae - No Differential Expression in Pathological Pregnancy. Placenta 16 (1995) 245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dixon HG, Robertson WB: A study of the vessels of the placental bed in normotensive and hypertensive women. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 65 (1958) 803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dommisse J, Tiltman AJ: Placental Bed Biopsies in Placental Abruption. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 99 (1992) 651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Espinoza J, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim YM, Goncalves LF, Bujold E, Camacho N, Romero R: Patients with preterm labor with intact membranes and preterm prom with failure of “physiologic transformation” of the spiral arteries have a higher impedance to flow in the uterine arteries. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 22 (2003) 145 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher SJ, Damsky CH: Human cytotrophoblast invasion. Semin Cell Biol 4 (1993) 183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleischer A, Schulman H, Farmakides G, Bracero L, Grunfeld L, Rochelson B, Koenigsberg M: Uterine artery Doppler velocimetry in pregnant women with hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol 154 (1986) 806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frank HG, Markee JE: Nonvillous Parts and Trophoblast Invasion In: Benirschke K and Kaufmann P: Pathology of the Human Placenta. Springer, Springer 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerretsen G, Huisjes HJ, Elema JD: Morphological changes of the spiral arteries in the placental bed in relation to pre-eclampsia and fetal growth retardation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 88 (1981) 876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham CH, Lala PK: Mechanism of control of trophoblast invasion in situ. J Cell Physiol 148 (1991) 228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrington K, Cooper D, Lees C, Hecher K, Campbell S: Doppler ultrasound of the uterine arteries: the importance of bilateral notching in the prediction of pre-eclampsia, placental abruption or delivery of a small-for-gestational-age baby. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 7 (1996) 182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heatley MK: Cytokeratins and cytokeratin staining in diagnostic histopathology. Histopathology 28 (1996) 479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herting A: Vascular pathology in hypertensive albuminuric toxemias of pregnancy. Clinics 4 (1945) 602 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hui KY, Haber E, Matsueda GR: Monoclonal-Antibodies to A Synthetic Fibrin-Like Peptide Bind to Human Fibrin But Not Fibrinogen. Science 222 (1983) 1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huppertz B, Kertschanska S, Demir AY, Frank HG, Kaufmann P: Immunohistochemistry of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), their substrates, and their inhibitors (TIMP) during trophoblast invasion in the human placenta. Cell Tissue Res 291 (1998) 133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hurskainen T, Hoyhtya M, Tuuttila A, Oikarinen A, AutioHarmainen H: mRNA expressions of TIMP-1, −2, and −3 and 92-KD type IV collagenase in early human placenta and decidual membrane as studied by in situ hybridization. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 44 (1996) 1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Irving JA, Lala PK: Functional role of cell surface integrins on human trophoblast cell migration: regulation by TGF-beta, IGF-II, and IGFBP-1. Exp Cell Res 217 (1995) 419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kadyrov M, Schmitz C, Black S, Kaufmann P, Huppertz B: Pre-eclampsia and maternal anaemia display reduced apoptosis and opposite invasive phenotypes of extravillous trophoblast. Placenta 24 (2003) 540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kam EPY, Gardner L, Loke YW, King A: The role of trophoblast in the physiological change in decidual spiral arteries. Human Reproduction 14 (1999) 2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaufmann P, Black S, Huppertz B: Endovascular trophoblast invasion: Implications for the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth retardation and preeclampsia. Biology of Reproduction 69 (2003) 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaufmann P, Huppertz B, Frank HG: The fibrinoids of the human placenta: origin, composition and functional relevance. Anat Anz 178 (1996) 485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khong TY: Acute atherosis in pregnancies complicated by hypertension, small-for-gestational-age infants, and diabetes mellitus. Arch Pathol Lab Med 115 (1991) 722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khong TY, De Wolf F, Robertson WB, Brosens I: Inadequate maternal vascular response to placentation in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia and by small-for-gestational age infants. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 93 (1986) 1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khong TY, Liddell HS, Robertson WB: Defective haemochorial placentation as a cause of miscarriage: a preliminary study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 94 (1987) 649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim YM, Bujold E, Chaiworapongsa T, Gomez R, Yoon BH, Thaler HT, Rotmensch S, Romero R: Failure of physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189 (2003) 1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim YM, Chaiworapongsa T, Gomez R, Bujold E, Yoon BH, Rotmensch S, Thaler HT, Romero R: Failure of physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries in the placental bed in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187 (2002) 1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim YM, Espinoza J, Kim MR, Chaiworapongsa T, Bujold E, Berman S, Romero R: The frequency of acute atherosis of the spiral arteries in the “great obstetrical syndromes”. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187 (2002) S238 [Google Scholar]

- 56.King A, Thomas L, Bischof P: Cell culture models of trophoblast II: trophoblast cell lines--a workshop report. Placenta 21 Suppl A (2000) S113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kitzmiller JL, Aiello LM, Kaldany A, Younger MD: Diabetic vascular disease complicating pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 24 (1981) 107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kitzmiller JL, Watt N, Driscoll SG: Decidual arteriopathy in hypertension and diabetes in pregnancy: immunofluorescent studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 141 (1981) 773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Labarrere CA, Catoggio LJ, Mullen EG, Althabe OH: Placental lesions in maternal autoimmune diseases. Am J Reprod Immunol Microbiol 12 (1986) 78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Labarrere CA, Faulk WP: Antigenic Identification of Cells in Spiral Artery Trophoblastic Invasion - Validation of Histologic-Studies by Triple-Antibody Immunocytochemistry. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 171 (1994) 165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lang I, Hartmann M, Blaschitz A, Dohr G, Kaufmann P, Frank HG, Hahn T, Skofitsch G, Desoye G: Differential Lectin-Binding to the Fibrinoid of Human Full-Term Placenta - Correlation with A Fibrin Antibody and the Paf-Halmi Method. Acta Anatomica 150 (1994) 170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lang I, Hartmann M, Blaschitz A, Dohr G, Skofitsch G, Desoye G: Immunohistochemical Evidence for the Heterogeneity of Maternal and Fetal Vascular Endothelial-Cells in Human Full-Term Placenta. Cell and Tissue Research 274 (1993) 211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lees C, Parra M, Missfelder-Lobos H, Morgans A, Fletcher O, Nicolaides KH: Individualized risk assessment for adverse pregnancy outcome by uterine artery Doppler at 23 weeks. Obstet Gynecol 98 (2001) 369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levy RA, Avvad E, Oliveira J, Porto LC: Placental pathology in antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus 7 Suppl 2 (1998) S81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Librach CL, Werb Z, Fitzgerald ML, Chiu K, Corwin NM, Esteves RA, Grobelny D, Galardy R, Damsky CH, Fisher SJ: 92-Kd Type-Iv Collagenase Mediates Invasion of Human Cytotrophoblasts. Journal of Cell Biology 113 (1991) 437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin S, Shimizu I, Suehara N, Nakayama M, Aono T: Uterine artery Doppler velocimetry in relation to trophoblast migration into the myometrium of the placental bed. Obstet Gynecol 85 (1995) 760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lockwood CJ, Krikun G, Schatz F: The decidua regulates hemostasis in human endometrium. Semin Reprod Endocrinol 17 (1999) 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lyall F: Development of the utero-placental circulation: the role of carbon monoxide and nitric oxide in trophoblast invasion and spiral artery transformation. Microsc Res Tech 60 (2003) 402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lyall F: The placental bed: Control of trophoblast invasion in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia.VIIth International Conference on the Extracelullar Matrix of the Female Reproductive Tract and Simpson Symposia (2004) [Google Scholar]

- 70.Madazli R, Somunkiran A, Calay Z, Ilvan S, Aksu MF: Histomorphology of the placenta and the placental bed of growth restricted foetuses and correlation with the Doppler velocimetries of the uterine and umbilical arteries. Placenta 24 (2003) 510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Markee JE: Menstruation in Intraocular Endometrial Transplant in the Rhesus Monkey. Contribution to Embryology Carnegie Institution of Washington 518 (1940) 219 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Michel M, Underwood J, Clark DA, Mowbray JF, Beard RW: Histologic and immunologic study of uterine biopsy tissue of women with incipient abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol 161 (1989) 409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mo LYL, Bascom PAJ, Ritchie K, Mccowan LME: A Transmission-Line Modeling Approach to the Interpretation of Uterine Doppler Waveforms. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology 14 (1988) 365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Multhaupt HAB, Mazar A, Cines DB, Warhol MJ, Mccrae KR: Expression of Urokinase Receptors by Human Trophoblast - A Histochemical and Ultrastructural Analysis. Laboratory Investigation 71 (1994) 392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nagy S, Bush M, Stone J, Lapinski RH, Gardo S: Clinical significance of subchorionic and retroplacental hematomas detected in the first trimester of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 102 (2003) 94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nayar R, Lage JM: Placental changes in a first trimester missed abortion in maternal systemic lupus erythematosus with antiphospholipid syndrome; a case report and review of the literature. Hum Pathol 27 (1996) 201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ochi H, Matsubara K, Kusanagi Y, Taniguchi H, Ito M: Significance of a diastolic notch in the uterine artery flow velocity waveform induced by uterine embolisation in the pregnant ewe. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 105 (1998) 1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ochi H, Suginami H, Matsubara K, Taniguchi H, Yano J, Matsuura S: Micro-Bead Embolization of Uterine Spiral Arteries and Changes in Uterine Arterial Flow Velocity Wave-Forms in the Pregnant Ewe. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 6 (1995) 272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Olofsson P, Laurini RN, Marsal K: A high uterine artery pulsatility index reflects a defective development of placental bed spiral arteries in pregnancies complicated by hypertension and fetal growth retardation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 49 (1993) 161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Papageorghiou AT, Yu CK, Bindra R, Pandis G, Nicolaides KH: Multicenter screening for pre-eclampsia and fetal growth restriction by transvaginal uterine artery Doppler at 23 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 18 (2001) 441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Papageorghiou AT, Yu CK, Cicero S, Bower S, Nicolaides KH: Second-trimester uterine artery Doppler screening in unselected populations: a review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 12 (2002) 78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pijnenborg R, Bland JM, Robertson WB, Brosens I: Uteroplacental arterial changes related to interstitial trophoblast migration in early human pregnancy. Placenta 4 (1983) 397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pijnenborg R, Dixon G, Robertson WB, Brosens I: Trophoblastic invasion of human decidua from 8 to 18 weeks of pregnancy. Placenta 1 (1980) 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Redline RW, Patterson P: Pre-eclampsia is associated with an excess of proliferative immature intermediate trophoblast. Hum Pathol 26 (1995) 594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Robertson WB, Brosens I, Dixon G: Uteroplacental vascular pathology. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 5 (1975) 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Robertson WB, Brosens I, Dixon HG: The pathological response of the vessels of the placental bed to hypertensive pregnancy. J Pathol Bacteriol 93 (1967) 581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Robertson WB, Khong TY, Brosens I, De Wolf F, Sheppard BL, Bonnar J: The placental bed biopsy: review from three European centers. Am J Obstet Gynecol 155 (1986) 401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Robson SC, Simpson H, Ball E, Lyall F, Bulmer JN: Punch biopsy of the human placental bed. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187 (2002) 1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schulman H, Fleischer A, Farmakides G, Bracero L, Rochelson B, Grunfeld L: Development of uterine artery compliance in pregnancy as detected by Doppler ultrasound. Am J Obstet Gynecol 155 (1986) 1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sexton LI, Herting AT, Reid DE: Premature separation of the normally implanted placenta. A clinicopathological study of 476 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol 59 (1950) 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sheppard BL, Bonnar J: Scanning electron microscopy of the human placenta and decidual spiral arteries in normal pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 81 (1974) 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sheppard BL, Bonnar J: The ultrastructure of the arterial supply of the human placenta in early and late pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 81 (1974) 497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sheppard BL, Bonnar J: The ultrastructure of the arterial supply of the human placenta in pregnancy complicated by fetal growth retardation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 83 (1976) 948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sixma JJ, Wester J: The hemostatic plug. Semin Hematol 14 (1977) 265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Smith SK: The physiology of menstruation In: D’Arcangues IS, Fraser JR, Newton JR, Odlind V: Contraception and mechanisms of endometrial bleeding. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 96.Talbert DG: Uterine Flow Velocity Wave-Form Shape As An Indicator of Maternal and Placental Development Failure Mechanisms - A Model-Based Synthesizing Approach. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 6 (1995) 261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Taylor RN: Review: immunobiology of preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 37 (1997) 79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vettraino IM, Roby J, Tolley T, Parka WC: Collagenase-1, stromelysin-1, and matrilysin are expressed within the placenta during multiple stages of human pregnancy. Placenta 17 (1996) 557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Voigt HJ, Becker V: Doppler flow measurements and histomorphology of the placental bed in uteroplacental insufficiency. J Perinat Med 20 (1992) 139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.von Dadelszen P, Magee LA: Could an infectious trigger explain the differential maternal response to the shared placental pathology of preeclampsia and normotensive intrauterine growth restriction? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 81 (2002) 642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Weiss JL, Malone FD, Vidaver J, Ball RH, Nyberg DA, Comstock CH, Hankins GD, Berkowitz RL, Gross SJ, Dugoff L, Timor-Tritsch IE, D’Alton ME: Threatened abortion: A risk factor for poor pregnancy outcome, a population-based screening study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 190 (2004) 745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Williams P, Warwick R: Angiology In: Williams P, Warwick R: Gray’s Anatomy. W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia: 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 103.Winterhager E, Kaufmann P, Gruemmer R: Cell-cell-communication during placental development and possible implications for trophoblast proliferation and differentiation Placenta 21 (2000) S61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zeek PM, Assali NS: Vascular changes in the decidua associated with eclamptogenic toxemia of pregnancy. Am J of Clin Pathol 20 (1950) 1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhou Y, Damsky CH, Chiu K, Roberts JM, Fisher SJ: Preeclampsia is associated with abnormal expression of adhesion molecules by invasive cytotrophoblasts. J Clin Inv 91 (1993) 950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]