Abstract

Objective:

Preeclampsia is considered an anti-angiogenic state. A role for the anti-angiogenic factors soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (sVEGFR-1) and soluble endoglin in preeclampsia has been proposed. Soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (sVEGFR-2) has been detected in human plasma, and the recombinant form of this protein has anti-angiogenic activity. There is a paucity of information about maternal plasma sVEGFR-2 concentrations in patients with preeclampsia and those without preeclampsia with small for gestational age (SGA) fetuses. This study was conducted to determine whether: 1) plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration changes throughout pregnancy; and 2) preeclampsia and SGA are associated with abnormalities in the maternal plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2.

Study Design:

This cross-sectional study included non-pregnant women (n=40), women with normal pregnancies (n=135), women with an SGA fetus (n=53), and women with preeclampsia (n=112). SGA was defined as an ultrasound-estimated fetal weight below the 10th percentile for gestational age that was confirmed by neonatal birth weight. Plasma concentrations of sVEGFR-2 were determined by ELISA.

Results:

(1) There was no significant difference in the mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 between non-pregnant women and those with normal pregnancies (p=0.8); (2) patients with preeclampsia and those without preeclampsia with SGA fetuses had a lower mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 than that of women with normal pregnancies (p < 0.001 for both); and (3) there was no significant difference in the mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 between patients with preeclampsia and those without preeclampsia with SGA (p = 0.9).

Conclusion:

Preeclampsia and SGA are associated with lower plasma concentrations of sVEGFR-2. One interpretation of the findings is that plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration could reflect endothelial cell function.

Keywords: Small for gestational age, intrauterine growth restriction, preeclampsia, sVEGF-R2, KDR, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION:

Preeclampsia is a syndrome characterized by hypertension and proteinuria. Mechanisms of disease implicated in this syndrome [1–4] include uteroplacental ischemia [5–11], increased trophoblast deportation [12–14] with apoptosis/necrosis [15–17], oxidative stress [18–27], and an exaggerated systemic inflammatory response [28–30]. The abnormalities observed in patients with preeclampsia include increased insulin resistance [31–34], hyperlipidemia [35–37], excess thrombin generation [38–43], and widespread endothelial damage/dysfunction [44–46] resulting in multiple organ damage. Of interest, neonates delivered from mothers with preeclampsia are at higher risk to be small for gestational age (SGA) than those delivered from women with normal pregnancies [47,48].

SGA, one of the “great obstetrical syndromes” [49], is generally diagnosed when the birthweight is below a given threshold for gestational age, often the 10th percentile [50]. SGA is considered a syndrome because smallness at birth can be caused by many factors, including defective placentation [8,51], infection [52,53], chromosomal anomalies [54,55], genetic disorders [56–58], and environmental factors [59] such as smoking [60,61], alcohol exposure [62], and cocaine use [63]. Moreover, in a subset of patients without preeclampsia with SGA fetuses, there is also evidence of leukocyte activation [64] as well as endothelial cell dysfunction [65–67].

Recent evidence suggests that both patients with preeclampsia and those with SGA neonates have a greater risk of short- and long-term complications—especially future cardiovascular disease—than women with normal pregnancies [68–73]. Anti-angiogenic and/or insulin-resistant states may independently represent baseline factors predisposing to the development of future cardiovascular disease [33,74].

The regulation of vascular growth and remodeling (angiogenesis) is considered to be central to normal placental and fetal growth/development [75–80]. Angiogenesis is regulated by several growth factors and their receptors, such as fibroblast growth factors, transforming growth factors, hepatocyte growth factors, angiogenins, angiopoietins, ephrins, and vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) [75,81]. However, VEGF signaling represents a critical step in physiologic and pathologic angiogenesis [75]. There is emerging evidence that VEGF is necessary to maintain normal endothelial health in the adult vasculature, which is a role that extends beyond angiogenesis [82].

VEGF, an endothelial cell-specific growth factor, is a glycoprotein with potent angiogenic properties. Its function is to promote endothelial cell proliferation, migration [75], and survival [83]. VEGF exerts biologic effects through two high-affinity tyrosine kinase receptors: VEGFR-1 (VEGF receptor-1 or flt-1 or fms-like tyrosine kinase-1) and VEGFR-2 (KDR or kinase insert domain-containing receptor or Flk-1 or fetal liver kinase-1). While VEGFR-1 is considered a “decoy” receptor, VEGFR-2 is the major mediator of the mitogenic, angiogenic, permeability-enhancing [75], and endothelial survival effects of VEGF. Both VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 have two isoforms: a membranous isoform, and a soluble isoform.

The soluble form of VEGFR-1 (sVEGFR-1) has been proposed to be released from the placenta, leading to endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia [84,85]. sVEGFR-1 binds VEGF and/or placental growth factor (PlGF) and inhibits their biological activities. Though exerting its functions through VEGFR-2, VEGF binds VEGFR-1 and its soluble form (sVEGFR-1) with an affinity that is ten times greater than its affinity for VEGFR-2 [75]. The contribution of sVEGFR-1 to the maternal syndrome of preeclampsia is thought to be, at least in part, related to its inhibition of VEGF stimulation of the endothelium-dependent nitric oxide system (through VEGFR-2) [86]. Plasma sVEGFR-1 concentration has been found to be elevated in preeclampsia both prior to [87–94] and after clinical diagnosis [84,87,95–99]. In contrast, studies of plasma sVEGFR-1 concentration in women with SGA fetuses have yielded conflicting results—either no change [100] or an increase [99].

Recently, sVEGFR-2 has been detected in human plasma [101]. The recombinant form of this protein has anti-angiogenic activity [102]. Plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration is lower in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus disease [103] and higher in those with acute leukemia, compared to healthy controls [104]. There is a paucity of information on plasma sVEGFR-2 concentrations in preeclampsia and SGA [105]. This study was conducted to determine whether: 1) plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration changes during pregnancy; and 2) pregnancies with preeclampsia and those without preeclampsia with SGA fetuses are associated with changes in the maternal plasma concentrations of sVEGFR-2.

Patients and Methods

Study Design:

This cross-sectional study was conducted by searching the clinical database and bank of biologic samples of the Perinatology Research Branch. The following groups were examined: 1) non-pregnant women (n=40); 2) women with normal pregnancies (n=135); 3) patients who delivered an SGA neonate without preeclampsia (n=53); and 4) women with preeclampsia (n=112). Patients with chronic hypertension, renal disease, multiple pregnancy, and major fetal congenital anomalies were excluded.

SGA pregnancies included only patients who underwent ultrasound examination for dating before 24 weeks of gestation. The diagnosis of SGA was based on a neonatal birthweight below the 10th percentile for gestational age [50], using the reference range proposed by Alexander et al [106]. Preeclampsia was defined as hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg on at least two occasions, four hours to one week apart) and proteinuria (≥ 300 milligrams in a 24-hour urine collection or one dipstick measurement ≥2+) [107]. Severe preeclampsia was defined as either severe hypertension (diastolic blood pressure ≥ 110 mm Hg) and mild-to-severe proteinuria or mild hypertension plus severe proteinuria (a 24-hour urine sample containing 3.5 grams protein or urine specimen ≥ 3+ protein by dipstick measurement) [107]. Patients with abnormal liver function tests (aspartate aminotransferase >70 IU/L) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000 /μL), as well as those with eclampsia, were also classified as having severe preeclampsia. The non-pregnant group consisted of women who had no history of acute or chronic inflammatory conditions. Women with normal pregnancies were enrolled from either the labor-delivery unit (in cases of scheduled cesarean section) or the antenatal clinic, and followed until delivery. A patient was considered to have a normal pregnancy if she met the following criteria: 1) no medical, obstetrical, or surgical complications; 2) absence of labor at the time of venipuncture; and 3) delivery of a normal term (≥ 37 weeks) infant whose birthweight was between the 10th and 90th percentile for gestational age.

All patients were enrolled at Hutzel Women’s Hospital, Detroit, MI, and provided written informed consent prior to the collection of plasma samples. The collection of samples and their utilization for research purposes was approved by the institutional review boards of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and Wayne State University. Many of these samples were used previously in studies of intravascular inflammation, soluble adhesion molecules, and cytokine biology in normal and complicated pregnancies [28,46].

Doppler velocimetry:

Pulse-wave and color Doppler ultrasound examinations of the uterine arteries were performed in a subset of patients with SGA (Acuson, Sequoia, Mountain View, CA USA). Patients with SGA fetuses were classified according to the results of the uterine artery Doppler velocimetry. An abnormal uterine artery Doppler velocimetry [108] was defined as a mean resistance index above the 95th percentile for gestational age (average of right and left) [109] or the presence of bilateral diastolic notches [110].

Sample collection and human sVEGFR-2 immunoassay:

Venipuncture was performed and the blood was collected into tubes containing EDTA. Samples were centrifuged and stored at –70° C. A specific and sensitive enzyme-linked immunoassay was used to determine the plasma concentration of human sVEGFR-2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN USA). This assay employs a quantitative sandwich immunoassay technique. Briefly, recombinant human VEGFR-2 standards and maternal plasma specimens were incubated in duplicate wells of the microtiter plates pre-coated with monoclonal antibodies specific for VEGFR-2. After an incubation period, the assay plates were subjected to a wash step to remove unbound antibody-enzyme reagent. Upon addition of a substrate solution (tetramethylbenzidine), color developed in the assay plates proportionally to the amount of VEGFR-2 bound in the initial step. The inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation for human sVEGFR-2 immunoassay were 2% and 4%, respectively. The sensitivity of the assay was 19.07 pg/mL.

Statistical analysis:

Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were used to test for normal distribution of the data. After logarithmic transformation [log(sVEGFR-2+1)], analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc tests (Dunnett’s T3) or Kruskal-Wallis with post-hoc Mann-Whitney U tests were utilized to determine the differences in the mean and/or median among groups according to the distribution of the data. Contingency tables and Chi-square tests were employed for comparisons of proportions. Regression analysis and Pearson correlation were used to assess the relationship between two continuous variables. Analysis was conducted with SPSS V.12 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL USA). A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The median maternal age of non-pregnant women was slightly higher than that of women with normal pregnancies (non-pregnant, median 26 years: range 18–40 years vs. normal pregnancy, median 25 years: range 17–40 years; p=0.03). The demographic and clinical characteristics of normal pregnant women, patients with an SGA neonate, and those with preeclampsia are displayed in Tables I and II. There were no significant differences in maternal age and ethnicity distribution among the three groups (see Table I). Among patients with SGA, 79% (42/53) delivered neonates whose birthweights were below the 5th percentile for gestational age. Among patients with preeclampsia, 40% (45/112) had early-onset preeclampsia (before 34 weeks of gestation), 79% (89/112) had severe preeclampsia, and 48% (54/112) delivered SGA neonates. The clinical characteristics of patients with preeclampsia are displayed in Table II. There was no significant difference in the median gestational age at blood sampling among the three groups (p=0.4; see Table I).

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of normal pregnant women, patients with an SGA fetus, and those with preeclampsia

| Normal pregnancy n = 135 |

p | SGA n=53 |

p | Preeclampsia n = 112 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) δ | 25 (17–40) | 0.5 | 24 (15–43) | 0.6 | 23 (13–43) | 0.2 |

| Race: African American | 107 (79.3%) | 0.3 | 46 (86.8%) | 0.8 | 91 (81.3%) | 0.6 |

| Caucasian | 15 (11.1%) | 4 (7.5%) | 13 (11.6%) | |||

| Hispanic | 7 (5.2%) | 1 (1.9%) | 5 (4.5%) | |||

| Asian | 0 | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (0.9%) | |||

| Other | 6 (4.4%) | 1 (1.9%) | 2 (1.8%) | |||

| Nulliparity | 37 (27.4%) | 0.005* | 26 (49.1%) | 0.1 | 69 (61.6%) | <0.001* |

| GA at blood sampling (weeks) δ | 37.6 (20–41.7) | 0.3 | 36.9 (25–39.7) | 0.5 | 35.6 (23.4–42.4) | 0.3 |

| GA at delivery (weeks) δ | 39.3 (37–42.4) | <0.001* | 37.1 (25–39.7) | 0.3 | 35.7 (23.7–42.4) | <0.001* |

| Birthweight (grams) δ | 3345 (2610–4080) | <0.001* | 2050 (300–2880) | 0.03* | 2195 (530–4460) | <0.001* |

| Birthweight <5th percentile | 0 | <0.001* | 42 (79.2%) | <0.001* | 32 (28.6%) | <0.001* |

Value expressed as median (range) or number (percent)

GA: gestational age

p < 0.05

= Kruskal-Wallis with post hoc Mann-Whitney U tests

Table II.

Clinical characteristics of patients with preeclampsia

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | |

| Systolic | 172 ± 19 |

| Diastolic | 104 ± 11 |

| Mean arterial pressure | 127 ± 12 |

| Aspartate aminotransferaseα (SGOT) (U/L) | 64 ± 115 |

| Platelet count (× 103) (μ/L) | 176 ± 54 |

| Birthweight <10th percentile | 54 (48%) |

| Severe preeclampsia | 89 (79%) |

Value expressed as mean ± SD or number (percent)

(n=132)

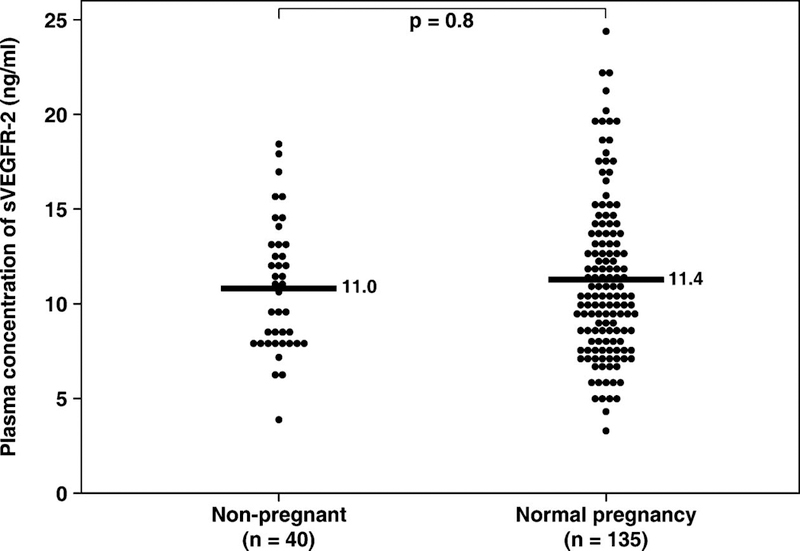

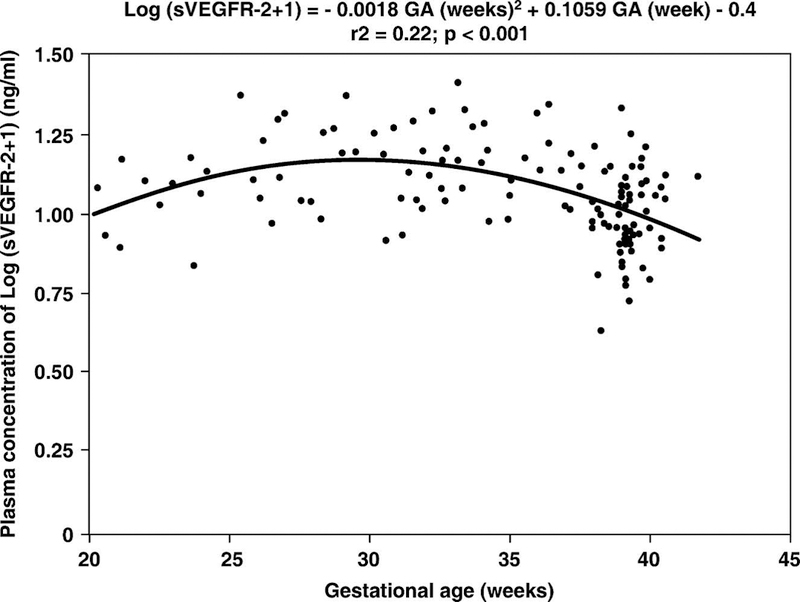

There was no significant difference in the mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 between non-pregnant women and women with normal pregnancies (non-pregnant, mean ± SD: 11.04±3.4 ng/mL vs. normal pregnancy, mean ± SD: 11.4±4.2 ng/mL; p=0.8; see Figure 1). In women with normal pregnancies, the plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 increased from 20–24 week of gestation (mean ± SD: 10.3±2.7 ng/mL), peaked at approximately 28–36 weeks (mean ± SD: 14.3±4.2 ng/mL), and declined as term approached (mean ± SD: 9.5±3.1 ng/mL). Plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration in women with normal pregnancies changed as a function of gestational age according to the equation log(sVEGFR-2+1) = −0.0018 (gestational age in weeks)2 + 0.1059 (gestational age in weeks) − 0.4 (r2=0.22; p< 0.001; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Mean plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration in non-pregnant women and women with normal pregnancies. There was no significant difference in the mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 between non-pregnant women and women with normal pregnancies (non-pregnant, mean ± SD: 11.04±3.4 ng/mL vs. normal pregnancy, mean ± SD: 11.4±4.2 ng/mL; p=0.8). The comparison was performed after logarithmic transformation (log+1) of the data. The statistical test used was unpaired t-test. *p<0.05.

Figure 2.

Plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration in women with normal pregnancies increased as a function of gestational age according to the following regression equation: log(sVEGFR-2+1) = −0.0018 (gestational age in weeks)2 + 0.1059 (gestational age in weeks) − 0.4 (r2=0.22; p< 0.001). *p<0.05.

Patients with preeclampsia and those with SGA had a lower mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 than women with normal pregnancies (normal pregnancy mean ± SD: 11.4±4.2 ng/mL, preeclampsia mean ± SD: 8.3±3.3 ng/mL, and SGA mean ± SD: 7.7±1.7 ng/mL; p<0.001 for both comparisons; see Figure 3). There was no significant difference in the mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 between patients with preeclampsia and those with SGA (p=0.9; Figure 3). Similar findings were observed after adjusting for parity, gestational age at blood sampling, and duration of sample storage; p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Mean plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration in women with normal pregnancies, patients with SGA, and patients with preeclampsia. Patients with preeclampsia and those without preeclampsia with SGA had a mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 lower than women with normal pregnancies (normal pregnancy mean ± SD: 11.4±4.2 ng/mL, preeclampsia mean ± SD: 8.3±3.3 ng/mL, SGA mean ± SD: 7.7±1.7 ng/mL; p<0.001 for both). There was no significant difference in the mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 between patients with preeclampsia and those with SGA (p=0.9). The comparisons were performed after logarithmic transformation (log+1) of the data. The statistical test used was ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett’s T3 test. *p < 0.05.

When patients without preeclampsia with SGA fetuses were classified according to the results of uterine artery Doppler velocimetry, there was no significant difference in the mean plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration between the two groups (normal uterine artery Doppler velocimetry mean ± SD: 7.9±1.6 ng/mL vs. abnormal uterine artery Doppler velocimetry mean ± SD: 7.6±2.1 ng/mL p=0.9). Both groups had a lower mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 than women with normal pregnancies (ANOVA p<0.001 for both).

Among patients with preeclampsia, there was no significant difference in the mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 both between patients with severe and those with mild preeclampsia (severe preeclampsia, mean±SD: 8.1±3.2 ng/ml vs. mild preeclampsia, mean±SD: 8.8±3.7 ng/mL; p = 0.5; t-test), and between those with and without SGA (preeclampsia with SGA, mean±SD: 7.8±3.2 ng/mL vs. preeclampsia without SGA, mean±SD: 8.7±3.4 ng/mL; p = 0.2; t-test).

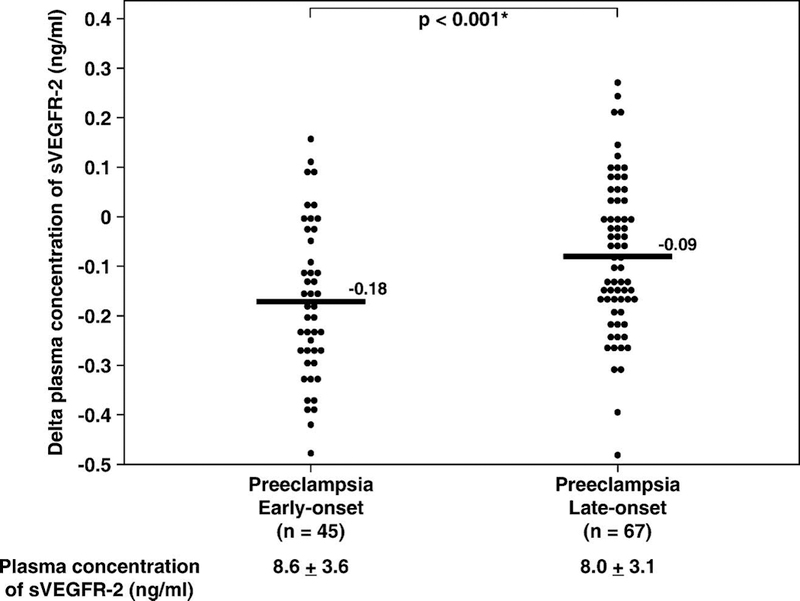

Because maternal plasma sVEGFR-1 concentration varies as a function of gestational age, the difference between the observed and the expected plasma sVEGFR-1 concentration (derived from the regression equation of plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration of normal pregnancy) in each patient (delta value) was calculated and used to examine the differences of plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration between patients with early-onset (<34 weeks) and late-onset (≥34 weeks) preeclampsia. Women with early-onset preeclampsia had a lower mean delta plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 than those with late-onset disease (p<0.001; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mean plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration in patients with preeclampsia classified according to the onset of the diagnosis. Women with early-onset (≤ 34 weeks) preeclampsia had a mean delta plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 lower than those with the late-onset (> 34 weeks) disease (early-onset, mean±SD: −0.18±0.15 ng/mL vs. late-onset, mean±SD: −0.09±0.15 ng/mL; p<0.001). The statistical test used was unpaired t-test. The means ± SD of plasma sVEGFR-2 concentrations in each group are displayed in the figure. * p < 0.05.

Among patients without preeclampsia with SGA, there was no significant difference in the mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 between those with severe SGA (birthweight <5th percentile) and those whose neonates weighed between the 5th and 10th percentiles at birth (severe SGA, n=42; mean±SD: 7.7±1.6 ng/mL vs. mild SGA, n=11; mean±SD: 7.9±2.2 ng/mL; p = 0.9; t-test). There was no significant correlation between plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 and neonatal birthweight (Pearson correlation; p=0.4).

Discussion

Principal findings of this study:

1) The mean plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration in women with normal pregnancies was not different from that of non-pregnant women; 2) the maternal plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration changed as a function of gestational age; 3) patients with preeclampsia and those with SGA fetuses had lower plasma sVEGFR-2 concentrations than women with normal pregnancies; 4) there was no significant difference in the mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 between patients with preeclampsia and those with SGA fetuses; 5) among patients without preeclampsia with SGA fetuses, there was no significant difference in plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration whether or not they had normal or abnormal uterine artery Doppler velocimetry results; 6) women with early-onset preeclampsia had a mean delta plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration higher than those with the late-onset disease; 7) the changes in plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 in patients with preeclampsia and those with SGA fetuses, in contrast to sVEGFR-1 [87,96], are not related to the severity of the disease.

Previous studies of sVEGFR-2 in normal pregnancy and pregnancy complications:

The finding that the mean plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration in women with normal pregnancies was not different from that of non-pregnant women is consistent with a previous study conducted by Masuyama et al [105]. In the current study, we observed a change in plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration as a function of gestational age. During pregnancy, plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 mirrored that of PlGF [87,111–113]. It increased from 20–24 weeks of gestation, peaked in the third trimester, and declined as term approached.

Similarly, the finding that plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration decreased in patients with preeclampsia and in those with SGA neonates without preeclampsia are consistent with studies conducted by both Schlembach et al [114] and Kim et al [115]. Both groups reported a lower serum/plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 in patients with preeclampsia than in women with normal pregnancies. In contrast, Masuyama et al [105] reported that there was no significant difference in the mean serum concentration of sVEGFR-2 between patients with preeclampsia and women with normal pregnancies [105]. However, only 15 patients with preeclampsia were enrolled in the study. Recently, Wallner et al [116] also reported a lower mean serum concentration of sVEGFR-2 in patients with intrauterine growth retardation, defined as abdominal circumference below the 5th percentile (diagnosed by ultrasound examination) and confirmed with a neonatal birthweight below the 10th percentile for gestational age. Although previous studies have used either plasma or serum samples to determine sVEGFR-2 concentration, Ebos et al [101] demonstrated that the concentration of sVEGFR-2 in plasma (EDTA, citrate, or heparin) was not significantly different from that in serum.

What are the potential sources of sVEGFR-2?

The soluble form of VEGFR-2 could be detected in conditioned media obtained from human endothelial cells, suggesting that endothelial cells are one of the sources of plasma sVEGFR-2 [101]. Although the membranous isoform of VEGFR-2 is expressed mainly on endothelial cells, a fraction of hematopoietic cells, also known as circulating endothelial progenitor cells, express VEGFR-2 [81,117]. A low level of expression for the membranous form of VEGFR-2 is also observed in neurons, osteoblasts, pancreatic duct cells, retinal progenitor cells, and megakaryocytes [81]. There is evidence that VEGFR-2 is expressed on cytotrophoblast stem cells and cells in the proximal columns of chorionic villi during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy [118]. However, VEGFR-2 mRNA and protein are, at term, localized almost exclusively to vascular endothelial cells of the placenta (in contrast to VEGFR-1, which is expressed mainly on trophoblasts) [119,120]. There is no significant difference in the expression of VEGFR-2 mRNA [99] and protein [120] in the placenta of patients with preeclampsia and that of women with normal pregnancies. In contrast, a study using Western blot analysis of protein extracted from placentas reported a lower expression of sVEGFR-2 in patients with preeclampsia than in women with normal pregnancies [121]. The mean serum concentration of sVEGFR-2 in the umbilical vein was in the same range as in maternal blood and was reported to be lower in both patients with preeclampsia and those with SGA than in women with normal pregnancies [116].

The soluble form of VEGFR-1 can be secreted from endothelial cells, monocytes, and placenta through alternative splicing of the VEGFR-1 gene [122]. Whether the soluble form of VEGFR-2 is a result of alternative mRNA splicing, proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-bound receptor, or another mechanism, is unknown [101]. While it is unclear what biological agents could stimulate sVEGFR-2 expression, the expression of the membranous isoform of VEGFR-2 is stimulated by VEGF and TNF-alpha [123,124]. Conflicting results have been reported regarding the effect of hypoxia on VEGFR-2 expression: either none or decreased or increased change, depending on the cell type (for example: either no change [125], or increased [126] in the human umbilical vein, or increased [127–129] in the lung and brain, or decreased [130] in the skin). The finding that there was no significant difference in the mean plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration among patients with SGA whether or not they had an increased impedance to blood flow in the uterine artery (as measured by uterine artery Doppler velocimetry) indicates that utero-placental ischemia may not be a major determinant of plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration.

What are the functions of sVEGFR-2?

The natural soluble form of VEGFR-2 was recently detected in both the mouse and human plasma [101]. Whether this natural sVEGFR-2 plays a significant role in VEGF signaling, as has been described for sVEGFR-1, remains to be determined. However, a previous study suggests that the soluble form of VEGFR-2 has anti-angiogenic properties. The administration of adenovirus encoding murine sVEGFR-2 to non-pregnant rats induces hypertension and proteinuria [84]. This biological effect, however, was not observed in pregnant rats, possibly owing to high levels of unopposed PlGF (which does not bind to sVEGFR-2) secreted by the placenta in the pregnant state. Another study supports the role of sVEGFR-2 as an anti-angiogenic factor derived from the observation that a local injection of recombinant sVEGFR-2 inhibited retinal neovascularization [102].

The finding that pregnant women with SGA and preeclampsia have lower plasma sVEGFR-2 concentrations than women with normal pregnancies is unexpected given that preeclampsia is considered an anti-angiogenic state [84]. On the other hand, one could speculate that the lower concentration of sVEGFR-2 in patients with preeclampsia may result from the low availability of free VEGF [84,131] to stimulate VEGFR-2 in endothelial cells. Thus, plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration could be a surrogate marker of endothelial cell function in the maternal circulation, since VEGF signaling through the membranous isoform of this protein is essential for endothelial cell function and survival [83].

Alternatively, plasma concentrations of sVEGFR-2 in patients with preeclampsia and those with SGA might reflect low endothelial cell regenerative capacity. This hypothesis is supported by two observations: 1) there is a lower number of circulating endothelial progenitor cells (as measured by the colony-forming unit method), and 2) patients with preeclampsia have lower plasma concentrations of sVEGFR-2 than women with normal pregnancies [115,132]. The circulating endothelial progenitor cells, phenotypically defined by flow cytometry as cells that express CD34 and VEGFR-2 [133], are capable of mobilizing to the sites of tissue or endothelial cell injuries for repair purposes, and correlate inversely with the risk of future death in patients with coronary artery disease [134]. The numbers of these cells have been proposed to reflect endothelial cell regenerative capacity [134]. Endothelial cells play a critical role in the regulation of vascular tone, platelet activity, leukocyte adhesion, and thrombosis, and are involved in the development of atherosclerosis [116,135]. Consistent with this hypothesis, several lines of evidence suggest that patients with preeclampsia, especially in the early-onset group, or women who delivered a low birthweight neonate have an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease [68–73].

Future studies are required to determine when plasma sVEGFR-2 concentration in patients with preeclampsia or in those with SGA fetuses becomes lower than that of women with normal pregnancies. If plasma sVEGFR-2 concentrations in patients with preeclampsia or SGA fetuses are low in early gestation or persist in the postpartum period, it is possible that these women, with low regenerative capacity of endothelial cells, would be more susceptible to pregnancy complications and, thus, be at greater risks for cardiovascular disease. The finding that there was no correlation between the severity of preeclampsia or SGA and plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 at the time of diagnosis suggests that other factors, (such as PlGF, sVEGFR-1, and soluble endoglin) [84,86,112] may be more directly involved in the clinical manifestations of these syndromes than sVEGFR-2.

It is possible that therapy focusing on angiogenic and anti-angiogenic processes in preeclampsia will be developed in the future [136]. Despite lower affinity to VEGF than sVEGFR-1 [81], the mean plasma concentration of sVEGFR-2 is almost ten times higher than that of sVEGFR-1 in women with normal pregnancies [114,116]. sVEGFR-2 may be important in the future development of angiogenic therapy in preeclampsia and SGA.

Reference List

- 1.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science 2005; 308:1592–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension 2005; 46:1243–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romero R, Lockwood C, Oyarzun E, Hobbins JC. Toxemia: new concepts in an old disease. Semin.Perinatol. 1988; 12:302–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2005; 365:785–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson WB, Brosens I, Dixon G. Maternal uterine vascular lesions in the hypertensive complications of pregnancy. Perspect.Nephrol.Hypertens. 1976; 5:115–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brosens IA. Morphological changes in the utero-placental bed in pregnancy hypertension. Clin.Obstet Gynaecol. 1977; 4:573–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheppard BL, Bonnar J. An ultrastructural study of utero-placental spiral arteries in hypertensive and normotensive pregnancy and fetal growth retardation. Br.J.Obstet.Gynaecol. 1981; 88:695–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khong TY, De Wolf F, Robertson WB, Brosens I. Inadequate maternal vascular response to placentation in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia and by small-for-gestational age infants. Br.J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986; 93:1049–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pijnenborg R, Anthony J, Davey DA, Rees A, Tiltman A, Vercruysse L, van Assche A. Placental bed spiral arteries in the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1991; 98:648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufmann P, Black S, Huppertz B. Endovascular trophoblast invasion: implications for the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth retardation and preeclampsia. Biol.Reprod. 2003; 69:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher SJ. The placental problem: linking abnormal cytotrophoblast differentiation to the maternal symptoms of preeclampsia. Reprod.Biol.Endocrinol. 2004; 2:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansen M, Redman CW, Wilkins T, Sargent IL. Trophoblast deportation in human pregnancy--its relevance for pre-eclampsia15. Placenta 1999; 20:531–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Placental debris, oxidative stress and pre-eclampsia. Placenta 2000; 21:597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sargent IL, Germain SJ, Sacks GP, Kumar S, Redman CW. Trophoblast deportation and the maternal inflammatory response in pre-eclampsia. J.Reprod.Immunol. 2003; 59:153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huppertz B, Kingdom J, Caniggia I, Desoye G, Black S, Korr H, Kaufmann P. Hypoxia favours necrotic versus apoptotic shedding of placental syncytiotrophoblast into the maternal circulation. Placenta 2003; 24:181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mor G, Gutierrez LS, Eliza M, Kahyaoglu F, Arici A. Fas-fas ligand system-induced apoptosis in human placenta and gestational trophoblastic disease. Am J Reprod.Immunol. 1998; 40:89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neale D, Demasio K, Illuzi J, Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Mor G. Maternal serum of women with pre-eclampsia reduces trophoblast cell viability: evidence for an increased sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis. J.Matern.Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003; 13:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chappell LC, Seed PT, Briley A, Kelly FJ, Hunt BJ, Charnock-Jones DS, Mallet AI, Poston L. A longitudinal study of biochemical variables in women at risk of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 187:127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hubel CA. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Proc.Soc Exp.Biol.Med 1999; 222:222–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowen RS, Moodley J, Dutton MF, Theron AJ. Oxidative stress in pre-eclampsia. Acta Obstet.Gynecol.Scand. 2001; 80:719–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh SW. Maternal-placental interactions of oxidative stress and antioxidants in preeclampsia. Semin.Reprod.Endocrinol. 1998; 16:93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers MS, Wang CC, Tam WH, Li CY, Chu KO, Chu CY. Oxidative stress in midpregnancy as a predictor of gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia. BJOG. 2006; 113:1053–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chamy VM, Lepe J, Catalan A, Retamal D, Escobar JA, Madrid EM. Oxidative stress is closely related to clinical severity of pre-eclampsia. Biol.Res. 2006; 39:229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma JB, Sharma A, Bahadur A, Vimala N, Satyam A, Mittal S. Oxidative stress markers and antioxidant levels in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Int.J Gynaecol.Obstet. 2006; 94:23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton GJ, Jauniaux E. Placental oxidative stress: from miscarriage to preeclampsia. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2004; 11:342–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts JM, Hubel CA. Oxidative stress in preeclampsia. Am.J Obstet.Gynecol 2004; 190:1177–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiktor H, Kankofer M, Schmerold I, Dadak A, Lopucki M, Niedermuller H. Oxidative DNA damage in placentas from normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies. Virchows Arch. 2004; 445:74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gervasi MT, Chaiworapongsa T, Pacora P, Naccasha N, Yoon BH, Maymon E, Romero R. Phenotypic and metabolic characteristics of monocytes and granulocytes in preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001; 185:792–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Redman CW, Sacks GP, Sargent IL. Preeclampsia: an excessive maternal inflammatory response to pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999; 180:499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sacks GP, Studena K, Sargent K, Redman CW. Normal pregnancy and preeclampsia both produce inflammatory changes in peripheral blood leukocytes akin to those of sepsis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998; 179:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seely EW, Solomon CG. Insulin resistance and its potential role in pregnancy-induced hypertension. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab 2003; 88:2393–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf M, Sandler L, Munoz K, Hsu K, Ecker JL, Thadhani R. First trimester insulin resistance and subsequent preeclampsia: a prospective study. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab 2002; 87:1563–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thadhani R, Ecker JL, Mutter WP, Wolf M, Smirnakis KV, Sukhatme VP, Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Insulin resistance and alterations in angiogenesis: additive insults that may lead to preeclampsia. Hypertension 2004; 43:988–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Innes KE, Weitzel L, Laudenslager M. Altered metabolic profiles among older mothers with a history of preeclampsia. Gynecol.Obstet.Invest 2005; 59:192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enquobahrie DA, Williams MA, Butler CL, Frederick IO, Miller RS, Luthy DA. Maternal plasma lipid concentrations in early pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia. Am.J.Hypertens. 2004; 17:574–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clausen T, Djurovic S, Henriksen T. Dyslipidemia in early second trimester is mainly a feature of women with early onset pre-eclampsia. BJOG. 2001; 108:1081–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hubel CA, Lyall F, Weissfeld L, Gandley RE, Roberts JM. Small low-density lipoproteins and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 are increased in association with hyperlipidemia in preeclampsia. Metabolism 1998; 47:1281–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiner CP, Kwaan HC, Xu C, Paul M, Burmeister L, Hauck W. Antithrombin III activity in women with hypertension during pregnancy. Obstet.Gynecol. 1985; 65:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaiworapongsa T, Yoshimatsu J, Espinoza J, Kim YM, Berman S, Edwin S, Yoon BH, Romero R. Evidence of in vivo generation of thrombin in patients with small-for-gestational-age fetuses and pre-eclampsia. J.Matern.Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002; 11:362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cadroy Y, Grandjean H, Pichon J, Desprats R, Berrebi A, Fournie A, Boneu B. Evaluation of six markers of haemostatic system in normal pregnancy and pregnancy complicated by hypertension or pre-eclampsia. Br.J.Obstet.Gynaecol. 1993; 100:416–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayashi M, Inoue T, Hoshimoto K, Negishi H, Ohkura T, Inaba N. Characterization of five marker levels of the hemostatic system and endothelial status in normotensive pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Eur.J.Haematol. 2002; 69:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de BK, ten Cate JW, Sturk A, Borm JJ, Treffers PE. Enhanced thrombin generation in normal and hypertensive pregnancy. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1989; 160:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Higgins JR, Walshe JJ, Darling MR, Norris L, Bonnar J. Hemostasis in the uteroplacental and peripheral circulations in normotensive and pre-eclamptic pregnancies. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1998; 179:520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friedman SA, Schiff E, Emeis JJ, Dekker GA, Sibai BM. Biochemical corroboration of endothelial involvement in severe preeclampsia. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1995; 172:202–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts JM, Taylor RN, Goldfien A. Endothelial cell activation as a pathogenetic factor in preeclampsia. Semin.Perinatol. 1991; 15:86–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Yoshimatsu J, Espinoza J, Kim YM, Park K, Kalache K, Edwin S, Bujold E, Gomez R. Soluble adhesion molecule profile in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. J Matern.Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002; 12:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Odegard RA, Vatten LJ, Nilsen ST, Salvesen KA, Austgulen R. Preeclampsia and fetal growth. Obstet.Gynecol. 2000; 96:950–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao R, Sorensen TK, Williams MA, Luthy DA. Influence of pre-eclampsia on fetal growth. J.Matern.Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003; 13:157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romero R Prenatal medicine: the child is the father of the man. Prenatal and Neonatal Medicine 1996; 1:8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seeds JW. Impaired fetal growth: definition and clinical diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol 1984; 64:303–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wulff C, Wilson H, Dickson SE, Wiegand SJ, Fraser HM. Hemochorial placentation in the primate: expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, angiopoietins, and their receptors throughout pregnancy. Biol.Reprod. 2002; 66:802–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fisher S, Genbacev O, Maidji E, Pereira L. Human cytomegalovirus infection of placental cytotrophoblasts in vitro and in utero: implications for transmission and pathogenesis. J Virol. 2000; 74:6808–6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arechavaleta-Velasco F, Koi H, Strauss JF III, Parry S. Viral infection of the trophoblast: time to take a serious look at its role in abnormal implantation and placentation? J Reprod.Immunol. 2002; 55:113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Snijders RJ, Sherrod C, Gosden CM, Nicolaides KH. Fetal growth retardation: associated malformations and chromosomal abnormalities. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993; 168:547–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.den Hollander NS, Cohen-Overbeek TE, Heydanus R, Stewart PA, Brandenburg H, Los FL, Jahoda MG, Wladimiroff JW. Cordocentesis for rapid karyotyping in fetuses with congenital anomalies or severe IUGR. Eur.J Obstet Gynecol Reprod.Biol. 1994; 53:183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kupferminc MJ, Many A, Bar-Am A, Lessing JB, Ascher-Landsberg J. Mid-trimester severe intrauterine growth restriction is associated with a high prevalence of thrombophilia. BJOG. 2002; 109:1373–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Constancia M, Hemberger M, Hughes J, Dean W, Ferguson-Smith A, Fundele R, Stewart F, Kelsey G, Fowden A, Sibley C, et al. Placental-specific IGF-II is a major modulator of placental and fetal growth. Nature 2002; 417:945–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ghezzi F, Tibiletti MG, Raio L, Di Naro E, Lischetti B, Taborelli M, Franchi M. Idiopathic fetal intrauterine growth restriction: a possible inheritance pattern. Prenat.Diagn. 2003; 23:259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prada JA, Tsang RC. Biological mechanisms of environmentally induced causes of IUGR. Eur.J Clin.Nutr. 1998; 52 Suppl 1:S21–S27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andres RL, Day MC. Perinatal complications associated with maternal tobacco use. Semin.Neonatol. 2000; 5:231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Misra DP, Nguyen RH. Environmental tobacco smoke and low birth weight: a hazard in the workplace? Environ.Health Perspect. 1999; 107 Suppl 6:897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuzma JW, Sokol RJ. Maternal drinking behavior and decreased intrauterine growth. Alcohol Clin.Exp.Res. 1982; 6:396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bada HS, Das A, Bauer CR, Shankaran S, Lester B, Wright LL, Verter J, Smeriglio VL, Finnegan LP, Maza PL. Gestational cocaine exposure and intrauterine growth: maternal lifestyle study. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 100:916–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sabatier F, Bretelle F, D’Ercole C, Boubli L, Sampol J, Dignat-George F. Neutrophil activation in preeclampsia and isolated intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000; 183:1558–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Friedman SA, de Groot CJ, Taylor RN, Golditch BD, Roberts JM. Plasma cellular fibronectin as a measure of endothelial involvement in preeclampsia and intrauterine growth retardation. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1994; 170:838–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bretelle F, Sabatier F, Blann A, D’Ercole C, Boutiere B, Mutin M, Boubli L, Sampol J, Dignat-George F. Maternal endothelial soluble cell adhesion molecules with isolated small for gestational age fetuses: comparison with pre-eclampsia. BJOG. 2001; 108:1277–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johnson MR, Anim-Nyame N, Johnson P, Sooranna SR, Steer PJ. Does endothelial cell activation occur with intrauterine growth restriction? BJOG. 2002; 109:836–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Cardiovascular health after maternal placental syndromes (CHAMPS): population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2005; 366:1797–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sattar N Do pregnancy complications and CVD share common antecedents? Atheroscler.Suppl 2004; 5:3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jonsdottir LS, Arngrimsson R, Geirsson RT, Sigvaldason H, Sigfusson N. Death rates from ischemic heart disease in women with a history of hypertension in pregnancy. Acta Obstet.Gynecol.Scand. 1995; 74:772–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davey SG, Hart C, Ferrell C, Upton M, Hole D, Hawthorne V, Watt G. Birth weight of offspring and mortality in the Renfrew and Paisley study: prospective observational study. BMJ 1997; 315:1189–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith GD, Sterne J, Tynelius P, Lawlor DA, Rasmussen F. Birth weight of offspring and subsequent cardiovascular mortality of the parents. Epidemiology 2005; 16:563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lawlor DA, Davey SG, Whincup P, Wannamethee G, Papacosta O, Dhanjil S, Griffin M, Nicolaides AN, Ebrahim S. Association between offspring birth weight and atherosclerosis in middle aged men and women: British Regional Heart Study. J.Epidemiol.Community Health 2003; 57:462–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wolf M, Hubel CA, Lam C, Sampson M, Ecker JL, Ness RB, Rajakumar A, Daftary A, Shakir AS, Seely EW, et al. Preeclampsia and future cardiovascular disease: potential role of altered angiogenesis and insulin resistance. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab 2004; 89:6239–6243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat.Med 2003; 9:669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wulff C, Weigand M, Kreienberg R, Fraser HM. Angiogenesis during primate placentation in health and disease. Reproduction. 2003; 126:569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith SK, He Y, Clark DE, Charnock-Jones DS. Angiogenic growth factor expression in placenta. Semin.Perinatol. 2000; 24:82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G, Pollefeyt S, Kieckens L, Gertsenstein M, Fahrig M, Vandenhoeck A, Harpal K, Eberhardt C, et al. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature 1996; 380:435–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fong GH, Rossant J, Gertsenstein M, Breitman ML. Role of the Flt-1 receptor tyrosine kinase in regulating the assembly of vascular endothelium. Nature 1995; 376:66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O’Shea KS, Powell-Braxton L, Hillan KJ, Moore MW. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature 1996; 380:439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shibuya M Differential roles of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 and receptor-2 in angiogenesis. J.Biochem.Mol.Biol. 2006; 39:469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sane DC, Anton L, Brosnihan KB. Angiogenic growth factors and hypertension. Angiogenesis. 2004; 7:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gerber HP, McMurtrey A, Kowalski J, Yan M, Keyt BA, Dixit V, Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. Requirement for Flk-1/KDR activation. J Biol.Chem. 1998; 273:30336–30343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, Libermann TA, Morgan JP, Sellke FW, Stillman IE, et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin.Invest 2003; 111:649–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Luttun A, Carmeliet P. Soluble VEGF receptor Flt1: the elusive preeclampsia factor discovered? J Clin.Invest 2003; 111:600–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, Hanai J, Mammoto T, Kim YM, Bdolah Y, Lim KH, Yuan HT, Libermann TA, et al. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nat.Med. 2006; 12:642–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N.Engl.J Med 2004; 350:672–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hertig A, Berkane N, Lefevre G, Toumi K, Marti HP, Capeau J, Uzan S, Rondeau E. Maternal serum sFlt1 concentration is an early and reliable predictive marker of preeclampsia. Clin.Chem. 2004; 50:1702–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McKeeman GC, Ardill JE, Caldwell CM, Hunter AJ, McClure N. Soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (sFlt-1) is increased throughout gestation in patients who have preeclampsia develop. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2004; 191:1240–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Kim YM, Kim GJ, Kim MR, Espinoza J, Bujold E, Goncalves L, Gomez R, Edwin S, et al. Plasma soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 concentration is elevated prior to the clinical diagnosis of pre-eclampsia. J Matern.Fetal Neonatal Med 2005; 17:3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Park CW, Park JS, Shim SS, Jun JK, Yoon BH, Romero R. An elevated maternal plasma, but not amniotic fluid, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) at the time of mid-trimester genetic amniocentesis is a risk factor for preeclampsia. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2005; 193:984–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Powers RW, Roberts JM, Cooper KM, Gallaher MJ, Frank MP, Harger GF, Ness RB. Maternal serum soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 concentrations are not increased in early pregnancy and decrease more slowly postpartum in women who develop preeclampsia. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2005; 193:185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wathen KA, Tuutti E, Stenman UH, Alfthan H, Halmesmaki E, Finne P, Ylikorkala O, Vuorela P. Maternal serum soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 in early pregnancy ending in pre-eclampsia or intrauterine growth retardation. J Clin.Endocrinol.Metab 2005; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Parra M, Rodrigo R, Barja P, Bosco C, Fernandez V, Munoz H, Soto-Chacon E. Screening test for preeclampsia through assessment of uteroplacental blood flow and biochemical markers of oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2005; 193:1486–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Koga K, Osuga Y, Yoshino O, Hirota Y, Ruimeng X, Hirata T, Takeda S, Yano T, Tsutsumi O, Taketani Y. Elevated serum soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (sVEGFR-1) levels in women with preeclampsia. J Clin.Endocrinol.Metab 2003; 88:2348–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Espinoza J, Bujold E, Mee KY, Goncalves LF, Gomez R, Edwin S. Evidence supporting a role for blockade of the vascular endothelial growth factor system in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Young Investigator Award. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 190:1541–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Stepan H, Geide A, Faber R. Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1. N.Engl.J.Med. 2004; 351:2241–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Staff AC, Braekke K, Harsem NK, Lyberg T, Holthe MR. Circulating concentrations of sFlt1 (soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1) in fetal and maternal serum during pre-eclampsia. Eur.J Obstet Gynecol Reprod.Biol. 2005; 122:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tsatsaris V, Goffin F, Munaut C, Brichant JF, Pignon MR, Noel A, Schaaps JP, Cabrol D, Frankenne F, Foidart JM. Overexpression of the soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor in preeclamptic patients: pathophysiological consequences. J Clin.Endocrinol.Metab 2003; 88:5555–5563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shibata E, Rajakumar A, Powers RW, Larkin RW, Gilmour C, Bodnar LM, Crombleholme WR, Ness RB, Roberts JM, Hubel CA. Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 is increased in preeclampsia but not in normotensive pregnancies with small-for-gestational-age neonates: relationship to circulating placental growth factor. J Clin.Endocrinol.Metab 2005; 90:4895–4903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ebos JM, Bocci G, Man S, Thorpe PE, Hicklin DJ, Zhou D, Jia X, Kerbel RS. A naturally occurring soluble form of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 detected in mouse and human plasma. Mol.Cancer Res. 2004; 2:315–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Agostini H, Boden K, Unsold A, Martin G, Hansen L, Fiedler U, Esser N, Marme D. A single local injection of recombinant VEGF receptor 2 but not of Tie2 inhibits retinal neovascularization in the mouse. Curr.Eye Res. 2005; 30:249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Robak E, Sysa-Jedrzejewska A, Robak T. Vascular endothelial growth factor and its soluble receptors VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 in the serum of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Mediators.Inflamm. 2003; 12:293–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wierzbowska A, Robak T, Wrzesien-Kus A, Krawczynska A, Lech-Maranda E, Urbanska-Rys H. Circulating VEGF and its soluble receptors sVEGFR-1 and sVEGFR-2 in patients with acute leukemia. Eur.Cytokine Netw. 2003; 14:149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Masuyama H, Suwaki N, Nakatsukasa H, Masumoto A, Tateishi Y, Hiramatrsu Y. Circulating angiogenic factors in preeclampsia, gestational proteinuria, and preeclampsia superimposed on chronic glomerulonephritis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 194:551–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol 1996; 87:163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sibai BM, Ewell M, Levine RJ, Klebanoff MA, Esterlitz J, Catalano PM, Goldenberg RL, Joffe G. Risk factors associated with preeclampsia in healthy nulliparous women. The Calcium for Preeclampsia Prevention (CPEP) Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997; 177:1003–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Harrington KF, Campbell S, Bewley S, Bower S. Doppler velocimetry studies of the uterine artery in the early prediction of pre-eclampsia and intra-uterine growth retardation. Eur.J Obstet Gynecol Reprod.Biol. 1991; 42 Suppl:S14–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kurmanavicius J, Florio I, Wisser J, Hebisch G, Zimmermann R, Muller R, Huch R, Huch A. Reference resistance indices of the umbilical, fetal middle cerebral and uterine arteries at 24–42 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1997; 10:112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bower S, Schuchter K, Campbell S. Doppler ultrasound screening as part of routine antenatal scanning: prediction of pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth retardation. Br.J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993; 100:989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Taylor RN, Grimwood J, Taylor RS, McMaster MT, Fisher SJ, North RA. Longitudinal serum concentrations of placental growth factor: evidence for abnormal placental angiogenesis in pathologic pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 188:177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tidwell SC, Ho HN, Chiu WH, Torry RJ, Torry DS. Low maternal serum levels of placenta growth factor as an antecedent of clinical preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001; 184:1267–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Krauss T, Pauer HU, Augustin HG. Prospective analysis of placenta growth factor (PlGF) concentrations in the plasma of women with normal pregnancy and pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. Hypertens.Pregnancy. 2004; 23:101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schlembach D, Beinder E. Angiogenic factors in preeclampsia. J Soc.Gynecol Investig. 2003; 10:316A. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kim SY, Park SY, Kim JW, Kim YM, Yang JH, Kim MY, Ahn HK, Shin JS, KIm JO, Ryu HM. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, plasma VEGF, VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 levels in preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 193:S74. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wallner W, Sengenberger R, Strick R, Strissel PL, Meurer B, Beckmann MW, Schlembach D. Angiogenic growth factors in maternal and fetal serum in pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth restriction. Clin.Sci.(Lond) 2007; 112:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Peichev M, Naiyer AJ, Pereira D, Zhu Z, Lane WJ, Williams M, Oz MC, Hicklin DJ, Witte L, Moore MA, et al. Expression of VEGFR-2 and AC133 by circulating human CD34(+) cells identifies a population of functional endothelial precursors. Blood 2000; 95:952–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhou Y, McMaster M, Woo K, Janatpour M, Perry J, Karpanen T, Alitalo K, Damsky C, Fisher SJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor ligands and receptors that regulate human cytotrophoblast survival are dysregulated in severe preeclampsia and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2002; 160:1405–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Clark DE, Smith SK, Sharkey AM, Charnock-Jones DS. Localization of VEGF and expression of its receptors flt and KDR in human placenta throughout pregnancy. Hum.Reprod. 1996; 11:1090–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Helske S, Vuorela P, Carpen O, Hornig C, Weich H, Halmesmaki E. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1, 2 and 3 in placentas from normal and complicated pregnancies. Mol.Hum.Reprod. 2001; 7:205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rajakumar A, Brandon HM, Daftary A, Ness R, Conrad KP. Evidence for the functional activity of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors overexpressed in preeclamptic placentae. Placenta 2004; 25:763–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Shibuya M Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (VEGFR-1/Flt-1): a dual regulator for angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2006; 9:225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Giraudo E, Primo L, Audero E, Gerber HP, Koolwijk P, Soker S, Klagsbrun M, Ferrara N, Bussolino F. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha regulates expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and of its co-receptor neuropilin-1 in human vascular endothelial cells. J Biol.Chem. 1998; 273:22128–22135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shen BQ, Lee DY, Gerber HP, Keyt BA, Ferrara N, Zioncheck TF. Homologous up-regulation of KDR/Flk-1 receptor expression by vascular endothelial growth factor in vitro. J Biol.Chem. 1998; 273:29979–29985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gerber HP, Condorelli F, Park J, Ferrara N. Differential transcriptional regulation of the two vascular endothelial growth factor receptor genes. Flt-1, but not Flk-1/KDR, is up-regulated by hypoxia. J Biol.Chem. 1997; 272:23659–23667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Waltenberger J, Mayr U, Pentz S, Hombach V. Functional upregulation of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor KDR by hypoxia. Circulation 1996; 94:1647–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kremer C, Breier G, Risau W, Plate KH. Up-regulation of flk-1/vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 by its ligand in a cerebral slice culture system. Cancer Res. 1997; 57:3852–3859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tuder RM, Flook BE, Voelkel NF. Increased gene expression for VEGF and the VEGF receptors KDR/Flk and Flt in lungs exposed to acute or to chronic hypoxia. Modulation of gene expression by nitric oxide. J Clin.Invest 1995; 95:1798–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Elvert G, Kappel A, Heidenreich R, Englmeier U, Lanz S, Acker T, Rauter M, Plate K, Sieweke M, Breier G, et al. Cooperative interaction of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha (HIF-2alpha ) and Ets-1 in the transcriptional activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (Flk-1). J.Biol.Chem. 2003; 278:7520–7530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Detmar M, Brown LF, Berse B, Jackman RW, Elicker BM, Dvorak HF, Claffey KP. Hypoxia regulates the expression of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor (VPF/VEGF) and its receptors in human skin. J.Invest Dermatol. 1997; 108:263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Reuvekamp A, Velsing-Aarts FV, Poulina IE, Capello JJ, Duits AJ. Selective deficit of angiogenic growth factors characterises pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1999; 106:1019–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sugawara J, Mitsui-Saito M, Hayashi C, Hoshiai T, Senoo M, Chisaka H, Yaegashi N, Okamura K. Decrease and senescence of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with preeclampsia. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab 2005; 90:5329–5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Khan SS, Solomon MA, McCoy JP Jr. Detection of circulating endothelial cells and endothelial progenitor cells by flow cytometry. Cytometry B Clin.Cytom. 2005; 64:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Werner N, Kosiol S, Schiegl T, Ahlers P, Walenta K, Link A, Bohm M, Nickenig G. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and cardiovascular outcomes. N.Engl.J Med 2005; 353:999–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Heitzer T, Schlinzig T, Krohn K, Meinertz T, Munzel T. Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 2001; 104:2673–2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zhang Y, Jing-Ying M, Almirez R, de Forest N, Schellenberger U, Pollit S, Karumanchi SA, Schreiner G, Protter AA, Li Z. Over expression of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFLT-1) induced experimental preeclampsia in rats and attenuation of preeclamptic phenotype by recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor 121 (VEGF 121). J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006; 2:287A. [Google Scholar]