Abstract

HIV is prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa, and depression frequently co-occurs. Depression is one of the most important predictors of poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART). Little has been done to develop integrated interventions that are feasible and appropriate for task-shifting to nonspecialists that seek to address both depression and barriers to ART adherence in Sub-Saharan Africa.

This case series describes an integrated intervention for depression and ART adherence delivered by a lay adherence counselor and supervised by a local psychologist. The 6-session intervention was based on problem-solving therapy for depression and for barriers to adherence (PST-AD), with stepped care for those whose depression did not recover with PST-AD. Primary outcomes were acceptability and depression. Acceptability was measured by participant attendance to the 6 sessions. Three case studies illustrate the structured intervention, solutions identified to adherence barriers and to problems underlying low mood, and changes seen in the clients’ psychological symptoms. Acceptability of the intervention was high and common mental disorder symptoms scores measured using the SRQ-8 decreased overall.

An integrated intervention for depression and adherence to ART appeared feasible in this low-income setting. An RCT of the intervention versus an appropriate comparison condition is needed to evaluate clinical and cost-effectiveness.

Keywords: integrated intervention, depression, task-shifting, adherence, HIV

In Sub-Saharan Africa the prevalence of depression is twice as high in people living with HIV compared to those without HIV, as is the case globally (Brandt, 2009; Chibanda, Benjamin, Weiss, & Abas, 2014; Ciesla & Roberts, 2001). Zimbabwe has a prevalence of HIV of 14.6% and the prevalence of depression among adults with HIV is estimated to be 68.5% (Chibanda, Cowan, Gibson, Weiss, & Lund, 2016). As shown in systematic reviews and a meta-analysis, depression is one of the most important individual-level factors that adversely affects adherence to antiretroviral therapy (Gonzalez, Batchelder, Psaros, & Safren, 2011; Langebeek et al., 2014). Antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence is the key driver to viral suppression, delaying progression to AIDS and reducing the likelihood of transmitting HIV to others (Chi et al., 2009; Cohen et al., 2011). Good adherence is critical for survival and for achieving the goal set by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS of 90% of people receiving ART having viral suppression by 2020 (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2015). Depression may affect adherence because it interferes with critical factors like information processing and problem solving (Fisher, Amico, Fisher, & Harman, 2008; Safren et al., 2012).

A systematic review suggested that the treatment of depression can improve adherence to ART (Sin & DiMatteo, 2014). A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) in the United States showed that antidepressants alone did not improve adherence (Pence et al., 2015), but other RCTs in high-income countries (HICs) have shown that psychological interventions that integrate cognitive behavioral therapy for depression with adherence counseling can improve depression and ART adherence (Safren et al., 2015; Safren et al., 2012; Simoni et al., 2013). While these interventions have been developed and tested in HIC settings, they may have similar results in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) and be able to be taken to scale. There is preliminary evidence to suggest the acceptability and feasibility of this approach in South Africa (Andersen et al., 2016). However, especially in low-income countries such as Zimbabwe, it is important that interventions are feasible for nonspecialists to deliver. A task-shifting approach has been recommended, by which nonspecialists take on tasks that in high-income settings are normally provided by mental health specialists. Task-shifting for depression can be delivered through a stepped-care model by which clients are all offered a low-intensity treatment in the first instance, only “stepping up” to intensive or specialist services as clinically required (Haaga, 2000).

In prior work, we described the initial phases of culturally and linguistically adapting a problem-solving therapy-based intervention for ART adherence among people living with HIV (PLWH) in Zimbabwe (Nzira Itsva or “New Map”; Bere et al., 2016), based on the original Life-Steps intervention (Safren et al., 2004). As a subsequent phase of this work, we sought to integrate Nzira Itsva with therapy for depression to address depression and ART adherence simultaneously. To integrate with Nzira Itsva, we picked a culturally adapted problem-solving therapy (PST) for depression and behavioral activation, known locally as “Opening up the Mind” or Kuvhura Pfungwa (Abas et al., 2016). PST is a brief evidence-based therapy for depression in which patients are taught a structured approach to identifying problems and finding workable solutions (D’Zurilla & Nezu, 2007; Mynors-Wallis, 1996). Depression may affect adherence because it interferes with critical cognitive and emotional correlates like information processing and problem solving (Fisher et al., 2008; Safren et al., 2012). The World Health Organization (WHO) is currently developing PST as part of its task-shifting toolkit for dealing with depression in LMIC (Lima et al., 2009). This forms part of the stepped-care guideline: The Mental Health Gap Action Plan (mhGAP; WHO, 2016).

The aim of this study is to assess the feasibility and acceptability of a culturally adapted, integrated 6-session psychological intervention based on PST and delivered by adherence counselors to address ART adherence and depression among PLWH receiving care in a general clinic setting in Harare, Zimbabwe and to examine preliminary changes in depression following the adapted intervention. Three cases will be presented in this paper to show how this intervention can be implemented in routine HIV care.

Methods

Setting

All participants were recruited from Parirenyatwa General Hospital, which has a large ART clinic in central Harare that provides ART to approximately 3,000 patients and is a referral center for complicated HIV management. When we initiated the intervention, there was no specific care at the clinic for depression. Only patients with suspected severe mental disorder could be referred to the psychiatrists.

Recruitment

We recruited participants with adherence problems for an open-label pilot trial through a number of methods that included referral from doctors, announcements in the waiting hall and in appointment queues. During the announcements, the research assistant gave a brief synopsis of the research study and asked that people with adherence problems who were willing to be screened come to the study room. An information sheet on the study was given to the participants and then informed consent was sought from the interested participants. Participants who met eligibility criteria and provided informed consent were given a baseline assessment and received the intervention.

Participants

Participants were included if they were aged 18 or over; had been on ART for at least 4 months as confirmed by pharmacy records and medical records; had adherence problems as assessed by one or more of the following: (a) one or more missed HIV clinic appointments in past 3 months, (b) referral from doctors due to falling CD4 count or detectable viral load, or (c) self-reported adherence problems; and had probable depression as assessed by scoring 5 or above on the short version of the Shona Self-Report Questionnaire (SRQ-8; Patel & Todd, 1996) and through interview by a Shona-speaking clinical psychologist.

Participants were excluded if they had severe cognitive impairment defined as a score of ≤ 6 on the International HIV-Dementia Scale (IHDS; Sacktor et al., 2005); hazardous alcohol use defined as a score of ≥ 5 on the short AUDIT-C screen for alcohol dependence (Bohn, Babor, & Kranzler, 1995); suicidal intent as determined by the P4 screener (Dube, Kurt, Bair, Theobald, & Williams, 2010); or were too unwell/agitated to take part.

Assessments

Acceptability

This was defined as participant therapy session attendance.

Depression Symptoms

These were assessed using the SRQ-8, which assesses common mental disorders that include depression. The SRQ-8 is a questionnaire consisting of 8 questions that was developed and validated in Zimbabwe with a cut-point of 5 and above indicating probable depression (Patel & Todd, 1996).

The supervising psychologist went through the scores to confirm the diagnosis. The SRQ-8 was administered by the research assistant at baseline and after 6 months. At Session 4 and Session 6 the SRQ-8 was administered by the adherence counselor.

ART Adherence

This was measured using a real-time electronic adherence monitor called Wisepill (Wisepill Technologies, Cape Town, South Africa). Wisepill was used for 14 days at baseline and at 6-month follow-up. Wisepill is a pill case that looks like a cell phone and contains an SMS microchip that sends a signal to the Wisepill server of the date and time of each opening. The score is the percentage of pills taken on time (+/− 1 hour) over the past 14 days. To supplement Wisepill, self-reported ART adherence was also assessed using the AIDS Clinical Trials Group questionnaire (Chesney et al., 2000), which assessed any missed ART doses in the last 30 days.

HIV care-related outcomes were extracted from clinic records, including viral load and CD4 count, which were measured by routine clinic blood test monitoring. Undetectable viral load was defined as less than or equal to 200.

A trained research assistant collected the study data, which was entered using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Zimbabwe, College of Health Sciences. The dataset was exported to Stata v14.0 for analysis. Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ/A/1936), the Joint Parirenyatwa Hospital Ethics Committee (JREC 18/13), and King’s College London College Research Ethics Committee (PNM/13/14–158). Participants were reimbursed ($3) for travel and provided with a snack.

The Intervention

The intervention was delivered by one adherence counselor. Her educational qualifications were 5 subject passes in 11th grade. She had worked as a nurse aide and then did 6 months training in adherence counseling. She had 5 years of experience working as an adherence counselor. She had received 5-day training in the culturally adapted, integrated behavioral intervention (Nzira Itsva). A local psychologist (TB) provided her with weekly face-to-face supervision.

The culturally adapted intervention was based on PST for depression and adherence. The underlying assumption of this approach is that mental distress can be understood as the negative consequences of ineffectual or maladaptive coping strategies. PST assists individuals to adopt a more realistically positive perspective of coping, recognize the role of emotions more effectively, and develop action plans geared towards reducing distress and enhancing well-being (D’Zurilla & Nezu, 2007; Lima et al., 2007; Nezu, 2004). PST does not require extensive training for delivery or complex skills from the therapist, and can therefore be delivered by lay counselors using a task-sharing approach. The 6-session intervention consisted of one session for PST for adherence barriers and then five sessions for PST for depression with some time spent at each session also reviewing adherence (Table 1). The first two sessions each take up to 50 minutes; Sessions 3 to 6 last up to 30 minutes.

Table 1.

Description of Integrated Intervention for Adherence and Depression

| Name | Components | |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Nzira Itsva (New Direction) Adherence Intervention | ● Psycho-education |

| ● Identification of barriers to adherence | ||

| ● Motivation to take medication | ||

| Session 2 | Problem Solving Therapy | ● Explanation of depression scores and psych-psychoeducation about depression |

| ● Identification of the problem | ||

| ● Brainstorming and evaluation of solutions | ||

| ● Identify one solution to work on | ||

| Session 3 | Problem Solving Review | ● Review of progress on the implementation of solution from previous session |

| ● Identify barriers faced and discuss solutions | ||

| ● Possible identification of another problem to work on | ||

| Session 4 | Positive Activity Scheduling | ● Identification of positive activities that the participant can engage in |

| Session 5 and 6 | Review and Relapse Prevention | ● Support application of problem solving |

| ● Encourage continuation of positive activities | ||

| ● Depression relapse prevention |

Session 1: Nzira Itsva (“New Direction” or “New Map”)

The first session is Nzira Itsva (Bere et al., 2016), the culturally and linguistically adapted Life-Steps adherence intervention (Safren, Otto, & Worth, 1999; Safren et al., 2001), a detailed description of which can be found elsewhere (Bere et al.). Life-Steps is an adherence intervention based on cognitive behavioral principles and uses a checklist to identify barriers to ART medication. The primary components include psychoeducation, enhancing motivation for adherence, and teaching problem-solving skills to address culturally relevant barriers to adherence.

The subsequent five sessions follow the culturally adapted PST intervention for depression (Abas et al., 2016; Chibanda et al., 2011). This approach includes psychoeducation about depression (information, advice and support) combined with problem solving, positive activity scheduling, stress management, and a 10- to 15-minute discussion of adherence during each session, checking progress and assisting the participant to find solutions for additional barriers to adherence.

Session 2: Problem Solving for Depression

Session 2 includes the following components:

Stage 1.

The counselor explains to the participant the meaning of their SRQ-8 scores.

Stage 2.

The counselor explains depression as a mental health condition, normalizing depression and providing information about evidence-based interventions including psychological therapy and antidepressants.

Stage 3 (Kuvhura pfungwa/”Opening up the Mind”).

The counselor helps the participant understand what is happening in their lives, encouraging them to share what is going on and how they feel about it. The aim is to identify and formulate the nature of problems being experienced that could be contributing to the depressed mood. The adherence counselor elicits, listens to, and reflects back the problem list. The participant is then encouraged to categorize and rate each problem in terms of its importance and potential solvability, which supports their ability to take control of their problems and determine what is important to them. Next, patient and counselor brainstorm a list of possible solutions.

Stage 4 (Kusimudzira/”Encouraging”).

The participant is encouraged to consider the pros and cons of potential solutions. The counselor helps the individual recognize potentially dysfunctional problem-solving style activities and helps them develop a SMART (Specific; Measurable; Achievable; Realistic; Timely) plan for the successful resolution of specific problems.

Stage 5 (Kusimbisa/”Strengthening”).

The participant is reassured and encouraged that the goals set can be achieved. The counselor discourages certain attitudes or beliefs that may inhibit or interfere with implementing the action plan. The participant is encouraged to see how depression and their problems might also have been contributing to nonadherence.

Session 3: Problem-Solving Review

The counselor reviews progress with problem-solving solutions. If the participant reports that the plan went well, the counselor praises, reinforces, and reaffirms the plan. The counselor also explores whether the participant wishes to work on identifying and generating solutions for additional problems. If the implementation plan did not go well, the counselor explores the possible reasons for this, unpacks potential obstacles that may have arisen, and repeats the various problem-solving tasks in order to determine where renewed efforts should be directed in order to solve the problem successfully.

Session 4: Positive Activity Scheduling and Deep Breathing

This session introduces use of positive activities (Kusimudzira) and social support networks to increase positivity and help improve mood and functionality. Here participants are encouraged to identify and schedule pleasant activities and task-oriented activities, particularly tasks that they have stopped or been avoiding because of depression. They are also urged to identify particular resources (individuals, agencies, etc.) that may be able to offer potential practical or emotional support.

Sessions 5–6: Review and Relapse Prevention

These sessions continue to support clients’ application of problem solving, activity scheduling, relaxation exercises, and addressing barriers to ART adherence following roughly the same format as Session 3. The final session incorporates a depression relapse-prevention component, which involves identifying personal warning signs of relapse, assessing participants’ knowledge of strategies to prevent relapse, and identifying future goals.

For patients failing to make progress after Session 3 or who remain depressed at Session 6, the counselor could refer to the supervising psychologist for assessment and further treatment. The psychologist then provides extra support to the counselor, or delivers the session together with the adherence counselor, or refers the patient to receive an antidepressant from the clinic — this is the stepped-care part of the intervention.

Results

We present detailed case histories for three participants to illustrate the application of the intervention. The supervising psychologist reviewed the cases to confirm the diagnosis.

Case 1

Herbert* was a 49-year-old male, married with six children. He did not complete the final year of secondary school and had worked as a security guard for over 20 years, but became unemployed after the firm closed down. He was taking first-line HIV medication and had been on ART for 3 years. He self-reported missing ART doses in the past 3 months.

He suffered from minor depression. Symptoms included sadness, thinking too much, poor appetite, fatigue, loss of interest, and thoughts that he was a failure. Only some of his symptoms were present more than half the days in the previous month. His main stressors were financial problems and worry about a blood test advised by his doctor that would cost USD 10, which he could not afford. His fear was that the advice to have this test (which was actually just a routine test to monitor urea and electrolytes) meant that the doctor thought his liver was failing, because his HIV medication was “working against him.” During Session 1, the main adherence barrier he identified was forgetting to take medication. He stored his medication in a bag that he sometimes forgot to open, and his phone alarm reminder often failed due to lack of battery power. A second barrier was medication side effects, especially nausea. He made a plan to put stickers on his drug storage bag, to remind him to take his ART, charge his phone, and to write down questions for his doctor about side effects.

During Session 2, he prioritized working on the problem of finding USD 10 for the blood test. He generated three solutions: finding a job as a security guard, buying goods in Lesotho to set up small-scale trading in Zimbabwe, or requesting the money from his eldest son. He decided to find a job as a security guard by visiting security firms to show his CV and request work. His actions were reviewed in Sessions 3 and 4. He had visited several firms and was offered an interview by one. He had also been offered a one-off piece of manual work which would earn enough for the blood test. He was remembering to take his ART with use of the stickers and phone alarm. During Session 5 it emerged that he had surrendered the money he had earned to cover a relative’s funeral expenses. Further, he had not been called back after his job interview. Because Herbert was unable to generate a feasible new solution, the counselor referred him for Step 2 care of review by a clinical psychologist. After the psychologist encouraged him to think of more solutions, he decided to try employment agencies and also to ask his son for the blood test money. At Session 6 he reported that his son had given him funds for the blood test, and that he had an appointment at an employment agency.

Case 4

Gift* was a 45-year-old male, unemployed and married with one child, who had been on ART for 9 years and was currently taking second-line HIV medication. He suffered from major depression. Symptoms included loss of interest, isolating himself from other men, feelings of being a failure, poor sleep, weight loss, repetitive worries about physical health, and loss of hope.

He had suffered from tuberculosis in the past and had been told that he needed an operation. He had given up all hope in life because he could not afford the operation. He was also worried that he could not financially take care of his wife and child. He had stopped taking his ART medication a few weeks before recruitment into the study. He said he knew the consequences of not taking medication and felt his behavior was like “knitting a jersey and then undoing the stitches.”

In Session 1, the counselor reviewed his stressors and helped him understand that taking ART was a step he could take to improve his health, even if he could not afford the operation. He opted to restart his ART and planned to set an alarm and ask his wife to remind him to take ART.

By the second session, his self-reported adherence had improved to 100%. He identified financial problems as his priority. He selected becoming an agent in mobile banking for a local telecommunication company as his solution. To do this he had to go to the telecommunications company to sign up. In the third session, the counselor reviewed the solution, which had not worked because he did not have enough capital required by the telecommunications company. The client then tried a different solution: to cook and sell traditional food for lunches at a local business centre. During Sessions 4–6, reviews showed that he was making good progress with this solution. He was less worried about physical health and his adherence improved based on his self-report.

Case 7

Sarah* was a 41-year-old widowed female with primary school education and two children. Self-employed, she reared and sold chickens. Sarah was taking first-line HIV medication and had been on ART for 8 years. She suffered from major depression. The symptoms, including poor sleep, sadness, loss of interest, irritability, and poor concentration, had lasted for several months. The main stressors were family conflict and desire to find a partner. She self-reported missing some ART doses in the last week.

During Session 1 the primary adherence barrier she identified was coping with side effects. She was on a tenofovir, lamuvidine, and efavirenz regimen and thought it was causing some of her anger towards her children. Sarah came up with the solution to talk to doctors and use a future session to learn about anger management. The second adherence barrier was forgetting to take her medication in the evening because she would be busy and tired. She came up with a solution to set an alarm for her evening medication. The third barrier was fear of taking medication after missing a dose, and as a solution to this, she talked to the doctors. She also identified missing appointments due to financial constraints and she decided to continue working on her small business that she was giving up on. During Session 2 she and the counselor discussed anger management techniques, including taking a step back, thinking about what she would say, and counting to 10 before reacting.

During Session 3 she reported still feeling depressed. She generated a solution to ask the doctors about the possibility of her mood being affected by her medication since her regimen had been changed that month.

During Session 4, Sarah identified attending church as her positive activity. She made a plan to start going to church again.

During Session 5, Sarah reported that church had gone well and she planned to continue attending and try to participate in more social and church-related activities. The counselor continued with psychoeducation about depression and anger management.

During Session 6, Sarah reported some improvement in mood and anger. She was doing relatively well, but at the 6-month follow-up visit her depression scores had risen slightly. The participant did not attribute the depression symptoms to any life event, but indicated that this could have been because of her medication regimen.

Discussion

This study provides one of the first examples of a combined intervention to treat depression and address barriers to ART adherence in a resource-limited, Sub-Saharan African setting. We used a stepped-care intervention for depression, integrated with a culturally adapted version of an adherence intervention shown to be feasible, acceptable, and effective in the U.S. (Safren et al., 2009).

The intervention was acceptable to participants as evidenced by their attendance in all 6 sessions, and this is representative of the participants who received this intervention. Considering that the participants were given minimum incentives—only travel to the clinic was reimbursed—this attendance was exceptional. A possible reason for this high attendance could be that the participants viewed the intervention as helpful to them and attending the session would be an opportunity to review their progress from the previous problem-solving session. The sessions were also scheduled at an agreed-upon time that was convenient for the participant—another factor that could have played a role in high attendance. The intervention was also feasible. An adherence counselor with a basic 6-month certificate in adherence counseling was able to deliver the intervention after being trained. The certificate in adherence counseling is a qualification that consists of basic training in HIV adherence counseling.

For all the cases presented here, the participant and the counselor were able to work collaboratively to brainstorm and identify barriers and generate solutions to those barriers. This is because the intervention is delivered in a collaborative approach with the participant actively involved. The goal is for participants to apply the skills learned in the sessions even after they have completed the intervention sessions.

Another reason why the collaborative approach worked well is because both the Nzira Itsva intervention and the PST were culturally and lingusitically adapted and are appropriate to be used in this setting (Bere et al., 2016). Therefore, these two combined provide an intervention that adherence counselors can deliver and that participants can learn and implement in their day-to-day lives. One challenge in implementing this type of intervention is in emphasizing the collaborative approach that the counselors must use. Generally, in this setting the adherence counselor is trained to “instruct” the patients so that they adhere to medication. Training the adherence counselor as well as checking fidelity of the counselling sessions ensured that this collaborative appraoch was maintained.

Strengths of this study include the cultural adaptation of evidence-based interventions that can be delivered by lay counselors in this resource-limited setting; a focus on missed visits in addition to adherence to promote engagement in care; integration of problem-solving strategies for both adherence and depression and a stepped-care model, which provides a parsimonious approach to treatment. This study has also indicated some promising outcomes regarding a change in depression symptoms for people living with HIV. This intervention is of public health relevance because in order to achieve the 90% target of those with HIV virally suppressed (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2015), depression has to be addressed in order to improve adherence. Areas that could use this model include other chronic illnesses in which adherence to medication is an important part of treatment (e.g., diabetes). Future studies can be conducted to determine whether the intervention is effective for clinical levels of depression, including major depressive disorder, as well as distress. Since depression is highly prevalent in people living with HIV, clinicians should incorporate depression screening and implement subsequent interventions for patients who are depressed.

In summary, this pilot study suggests that interventions that integrate depression treatment with collaborative problem-solving around barriers to adherence can be associated with improved outcomes in both depression and adherence. Though this was not an effectiveness study, we can say with caution that the findings are consistent with the evidence from high-income countries that depression can be treated in PLWH (Sherr, Clucas, Harding, Sibley, & Catalan, 2011). This is consistent with the most recent WHO guidelines that recommend an integration of depression screening and management in routine care for people living with HIV (WHO, 2016). In light of these findings a larger randomized effectiveness-implementation trial is warranted.

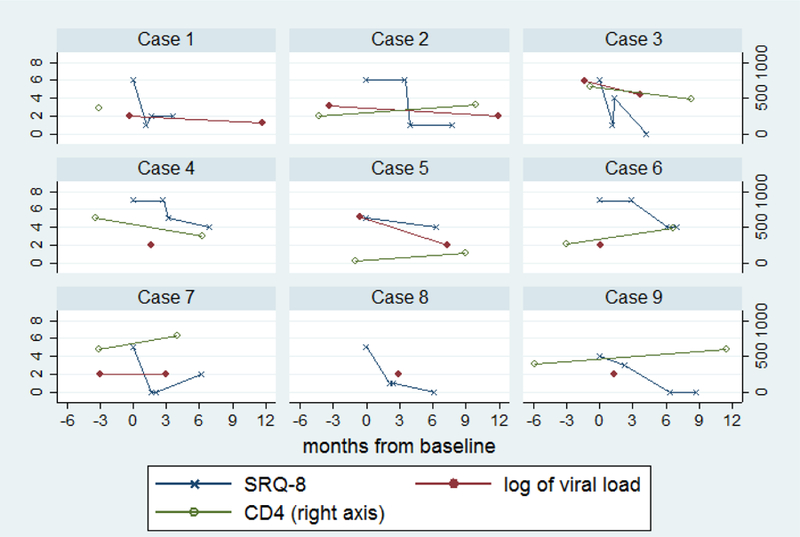

Figure 1:

SRQ-8, log of viral load and CD4 over time by individual

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics and Outcomes

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | Case 9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | Female | Female | Male | Male | Female | Female | Male | Female | |

| Age | 49 | 41 | 40 | 45 | 43 | 65 | 41 | 20 | 35 | |

| Marital status | Married | Widowed | Single | Married | Married | Widowed | Widowed | Single | Married | |

| Years on ART | 1.9 | 3.9 | 7.0 | 9.1 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 7.8 | 10.1 | 0.5 | |

| Regimen | Baseline | First line | First line | First line | Second line | First line | First line | First line | Second line | First line |

| Regimen | Follow-up | First Line | First line | First line | Second line | Second line | First line | First line | Second line | First line |

| Number of sessions attended | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| Self-report % | Baseline | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 71.4 | 85.7 | 100 | 100 |

| Pills taken | Follow-up | 81.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | - | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Wisepill adherence | Baseline | 100 | 100 | 96.7 | 93 | 100 | - | - | - | 100 |

| Follow-up | 100 | 100 | 100 | 93 | - | 100 | 100 | - | - | |

| Self-report last | Baseline | 1–3 months ago | In past week | Never | Never | Never | In past week | In past week | 1–3 months ago | 1–3 months ago |

| Missed medicate on dose | Follow-up | In past week | Never | Never | >3 months ago | > 3 months ago | Never | Never | Never | Never |

| CD4 | Baseline | 354 | 243 | 657 | 633 | 28 | 273 | 604 | - | 398 |

| Follow-up | - | 415 | 490 | 382 | 136 | 485 | 784 | - | 604 | |

| Viralload | Baseline | <200 | 1300 | 750000 | <200 | 150000 | <200 | <200 | - | - |

| Follow-up | <200 | <200 | 27000 | <200 | <200 | <200 | <200 | <200 | <200 | |

| SRQ-8 | Baseline | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Session 4 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 7 | - | 7 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| Session 6 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 | - | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Follow-up | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Highlights.

An integrated intervention for depression and ART adherence delivered by a lay adherence counselor in a low-income country is described

Acceptability of the intervention as measured by patient’s attendance was high

The integrated intervention was feasible as indicated by the counsellor’s ability to deliver the intervention

The intervention was associated with a reduction in depression symptoms

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported in part by an NIMH R21 Grant, reference 5R21MH094156-02, to Melanie Abas and Dixon Chibanda.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Not the patient’s real name.

References

- Abas M, Bowers T, Manda E, Cooper S, Machando D, Verhey R, … Chibanda D (2016). ‘Opening up the mind’: problem-solving therapy delivered by female lay health workers to improve access to evidence-based care for depression and other common mental disorders through the Friendship Bench Project in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 10(1), 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13033-016-0071-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen LS, Magidson JF, O’Cleirigh C, Remmert JE, Kagee A, Leaver M, … Joska J (2016). A pilot study of a nurse-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy intervention (Ziphamandla) for adherence and depression in HIV in South Africa. Journal of Health Psychology doi: 10.1177/1359105316643375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bere T, Nyamayaro P, Magidson J, Chibanda D, Chingono A, O’Cleirgh C, … Abas M (2016). Cultural adaptation of a cognitive-behavioural intervention to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe: Nzira Itsva. Journal of Health Psychology, 1–12. doi:doi: 10.1177/1359105315626783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bohn MJ, Babor TF, & Kranzler HR (1995). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 56(4), 423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R (2009). The mental health of people living with HIV/AIDS in Africa: a systematic review. African Journal of AIDS Research, 8(2), 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, … Adherence Working Group Of The Outcomes Committee Of The Adult Aids Clinical Trials, G. (2000). Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG Adherence Instruments. AIDS Care, 12(3), 255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi BH, Cantrell RA, Zulu I, Mulenga LB, Levy JW, Tambatamba BC, … Bulterys M (2009). Adherence to first-line antiretroviral therapy affects non-virologic outcomes among patients on treatment for more than 12 months in Lusaka, Zambia. International Journal of Epidemiology, 38(3), 746–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibanda D, Benjamin L, Weiss H, & Abas M (2014). Mental, neurological and substance use disorders in people living with HIV/AIDS in low and middle income countries. JAIDS, 67(Suppl 1), S54–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibanda D, Cowan F, Gibson L, Weiss HA, & Lund C (2016). Prevalence and correlates of probable common mental disorders in a population with high prevalence of HIV in Zimbabwe. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1). 10.1186/s12888-016-0764-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibanda D, Mesu P, Kajawu L, Cowan F, Araya R, & Abas M (2011). Problem-solving therapy for depression and common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: piloting a task-shifting primary mental health care intervention in a population with a high prevalence of people living with HIV. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, & Roberts JE (2001). Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(5), 725–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, … Fleming TR (2011). Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(6), 493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla T, & Nezu A (2007). Problem-solving therapy: A positive approach to clinical Intervention (3rd ed.). New York: Spring Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dube P, Kurt K, Bair MJ, Theobald D, & Williams LS (2010). The p4 screener: evaluation of a brief measure for assessing potential suicide risk in 2 randomized effectiveness trials of primary care and oncology patients. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 12(6), 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Amico KR, Fisher WA, & Harman JJ (2008). The information-motivation-behavioral skills model of antiretroviral adherence and its applications. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 5(4), 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Batchelder AW, Psaros C, & Safren SA (2011). Depression and HIV/AIDS Treatment Nonadherence: A Review and Meta-analysis. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 58(2), 181–187 110.1097/QAI.1090B1013E31822D31490A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaga DA (2000). Introduction to the special section on stepped care models in psychotherapy. J Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 547–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. (2015). An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Langebeek N, Gisolf EH, Reiss P, Vervoort SC, Hafsteinsdottir TB, Richter C, … Nieuwkerk PT (2014). Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: a meta-analysis. BMC Medicine, 12, 142. doi: 10.1186/preaccept-1453408941291432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima VD, Geller J, Bangsberg DR, Patterson TL, Daniel M, Kerr T, … Hogg RS (2007). The effect of adherence on the association between depressive symptoms and mortality among HIV-infected individuals first initiating HAART. AIDS, 21(9), 1175–1183. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32811ebf57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima VD, Harrigan R, Bangsberg DR, Hogg RS, Gross R, Yip B, & Montaner JS (2009). The combined effect of modern highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens and adherence on mortality over time. JAIDS, 50(5), 529–536. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819675e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mynors-Wallis L (1996). Problem-solving treatment: Evidence for effectiveness and feasibility in primary care. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 26(3), 249–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezu AM (2004). Problem solving and behavior therapy revisited. Behavior Therapy, 35(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, & Todd C (1996). The validity of the Shona version of the self report questionnaire (SRQ) and the development of the SRQ8. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 6, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, Gaynes BN, Adams JL, Thielman NM, Heine AD, Mugavero MJ, … Quinlivan EB (2015). The effect of antidepressant treatment on HIV and depression outcomes: the SLAM DUNC randomized trial. AIDS, 29(15), 1975–1986. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000000797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacktor NC, Wong M, Nakasujja N, Skolasky RL, Selnes OA, Musisi S, … Katabira E (2005). The International HIV Dementia Scale: a new rapid screening test for HIV dementia. AIDS, 19(13), 1367–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Hendriksen ES, Mayer KH, Mimiaga MJ, Pickard R, & Otto MW (2004). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for HIV Medication Adherence and Depression. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 11(4), 415–424. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Mayer K, Ou S-S, McCauley M, Grinsztejn B, Hosseinipour M, … Cohen M (2015). Adherence to Early Antiretroviral Therapy: Results from HPTN 052, A Phase III, Multinational Randomized Trial of ART to Prevent HIV-1 Sexual Transmission in Serodiscordant Couples. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 69(2), 234–240. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Bullis JR, Otto MW, Stein MD, & Pollack MH (2012). Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected injection drug users: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 404–415. doi: 10.1037/a0028208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Judy T, Raminani S, Reilly LC, Otto MW, & Mayer KH (2009). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychology, 28, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Otto MW, & Worth JL (1999). Life-steps: Applying cognitive behavioral therapy to HIV medication adherence. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 6(4), 332–341. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL, Salomon E, Johnson W, Mayer K, & Boswell S (2001). Two strategies to increase adherence to HIV antiretroviral medication: Life-Steps and medication monitoring. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39(10), 1151–1162. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00091-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr L, Clucas C, Harding R, Sibley E, & Catalan J (2011). HIV and depression - a systematic review of interventions. Psychology Health & Medicine, 16(5), 493–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni J, Wiebe J, Sauceda J, Huh D, Sanchez G, Longoria V, … Safren S (2013). A preliminary RCT of CBT-AD for adherence and depression among HIV Positive Latinos on the U.S.-Mexico Border: The Nuevo Día Study. AIDS Behavior, 17(8), 2816–2829. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0538-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin NL, & DiMatteo MR (2014). Depression treatment enhances adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 47(3), 259–269. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9559-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2016). mhGAP Intervention Guide. Mental Health Gap Action Programme. Version 2.0 Retrieved from www.who.int [PubMed]