Abstract

Introduction

Telerehabilitation programmes have been attracting increasing attention as a potential alternative to conventional rehabilitation. Video conferencing can facilitate communication between healthcare professionals and patients. However, in certain cases, video conferencing may face practical limitations. As an alternative to real-time conferencing, sensor-based technologies can transmit the acquired data to healthcare providers. This study aimed to design and develop a sensor-based telerehabilitation programme and to outline the corresponding requirements for such a system.

Development

The development of the sensor-based telerehabilitation programme was carried out based on user needs. The programme includes a portable platform for the patient as well as a web-based platform for the healthcare professional, thus allowing for an individualised rehabilitation programme. Communication, training, reporting, and information services were provided for the patients. Moreover, the portability and usability of the programme were enhanced by utilising the system in offline mode as well.

Application

The programme is currently being tested in the North Denmark Region to assess the feasibility and acceptance of a telerehabilitation programme as an alternative solution to the self-training programme for patients who have been discharged from knee surgery. The preliminary results of our assessment showed a high level of acceptance among the users.

Discussion

In this study, a semi-online sensor-based telerehabilitation programme was tested. It is argued that a similar sensor-based telerehabilitation programme can be utilised as an alternative solution for self-training rehabilitation in the future; however; further studies and development are required to ensure the quality and reliability of sensor-based services.

Keywords: telerehabilitation, knee rehabilitation, motion sensor, semi-online telemonitoring

Summary.

What is already known?

Video conferencing system are widely being used to deliver telerehabilitation services over a distance.

Although, real-time video communication overcomes the limitations on providing services remotely; several limitations such as portability and flexibility are unresolved.

What does this paper add?

Requirements for providing communication, training, reporting, and information services were discussed.

Sensor-based telerehabilitation programs can be considered as an alternative solution introducing telerehabilitation programs for the patients.

Dependency on continuous and stable internet connection can be resolved by employing a semi-online telerehabilitation program. Biometric authentication methods can be used to improve users’ experience.

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty is considered the most successful and efficient surgical treatment for patients with degenerative knee arthritis.1 Studies have shown that post-surgical physical rehabilitation improves the physical function over the short-term.2 Moreover, an individualised exercise programme has been shown to improve patients’ adherence as well as facilitate health recovery.3 Hall et al 4 have shown that a therapist–patient relationship may have a positive influence on the observed clinical outcomes. Baker et al 5 also showed that an in-home training programme accelerates the rehabilitation process and generates significant improvements in patients’ quality of life.

More comprehensive healthcare services, as well as higher accessibility, can be introduced using a comprehensive telerehabilitation programme (TRP).6–8 It has been shown that patients will experience a higher level of satisfaction along with the practical convenience of a home-based TeleHomeCare solution.9 10

Russell11 has categorised TRP solutions into image-based (audio/video-based communication), sensor-based, and virtual environment-based TRP. Real-time video-conference communication was frequently employed to establish live video communication between patients and healthcare professionals (HPs). The effectiveness of the solution on the functional performance of patients,12–14 degree of user satisfaction,15 16 and cost-effectiveness of the system17–19 have been evaluated. It is reported that in-home telerehabilitation using video-conferencing equipment may improve the accessibility of supervised rehabilitation14 and can also be considered effective as conventional treatment.13 Bini et al 20 demonstrated the advantages of employing asynchronous (semi-offline) video rehabilitation compared with real-time video conferencing. Asynchronous telecommunication can be more practical in comparison with real-time video conferencing and requires fewer resources. Piqueras et al 21 introduced a sensor-based TRP by employing two wearable sensors to monitor the patients’ exercises and send data as an alternative solution for a video conference.

Hence, it is hypothesised that a hybrid (online/offline) TRP using sensor technologies can facilitate in-home rehabilitation as well as enhance the human resource management in the healthcare sector and overcome the difficulties of accessing services at a distance. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to develop and test a semi-offline TRP using telecommunication and wireless motion sensors.

Development

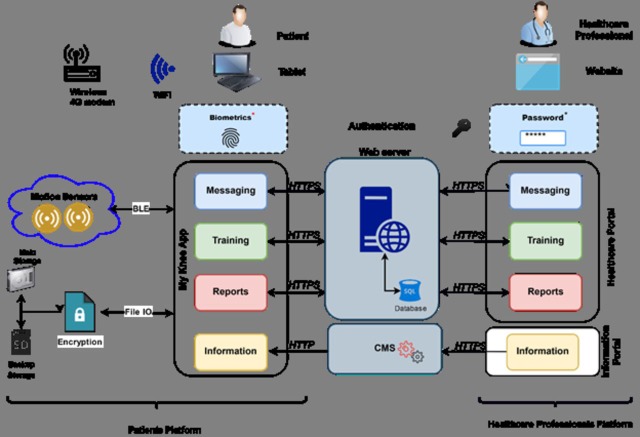

The TRP was developed by the research and development team at the Laboratory for Welfare Technology, Aalborg University, with close collaboration with the university-affiliated Farsø Hospital using a participatory design method.22 The TRP benefitted from two different environments, one for patients and one for HPs, and could thus provide various services for each side. The communication between the two platforms (introduced below) was provided using the internet. Figure 1 shows an overview of the developed TRP.

Figure 1.

An overview of the developed telerehabilitation programme. Patients used a tablet to access the programme. MyKnee application (running on the tablet) was responsible for providing the telerehabilitation services using a user-friendly graphical interface. Healthcare professionals could communicate with patients and individualise the rehabilitation programme using an online web service. A content management system (CMS) interconnects the two platforms. BLE, Bluetooth low energy; HTTPS, hypertext transfer protocol secure.

Telerehabilitation services

The TRP establishes electronic communication between patients and HPs by providing four main services:

Asynchronous messaging service.

Training management and HP intervention service

Patient report management.

A dynamic web portal is providing information and multimedia for the patient.

Table 1 shows the detailed sub-services introduced in each of these four main services in the patient and HP platform of the TRP.

Table 1.

Providing services and corresponding system task for (a) patient and (b) healthcare professional sides of the telerehabilitation programme

| Service | Patient platform | HP platform |

| Messaging | Send and receive text messages Notify new/unread messages Notify if receiver read the message Send and receive text messages |

Send and receive text messages Notify new/unread messages Notify if receiver read the message Send and receive text messages |

| Training | Provide a daily virtual training programme (number of repetitions and sets) Provide video instruction for each exercise Organise performed and remaining exercises and notify the patient Count the repetitions using sensors Send adherence report (exercise, repetitions, sets, overall adherence) |

Personalise training programme Show patients’ adherence |

| Reports | Collect and send PRO reports (pain, OKS,33 knee swollen) Instruct how to report Notify the patient to send a report Show a history of reports |

Show report |

| Information | Provide project relevant multimedia/information | Modify the information |

HP, healthcare professional; OKS, Oxford Knee Score; PRO, patient reported outcome.

Platforms and hardware

Two different platforms were provided for the HPs and patients (figure 1). HPs may have access to the TRP using a customised web service; this web service can use any web browser (supporting JavaScript v1.6). The HP web service (HP portal) was developed using PHP server-side scripting language and MySQL database management system. Hence, the HP portal introduced the minimum dependency to specific hardware; however; the HP was required to have internet access in order to be able to use the HP portal.

An information portal (Info Portal) was developed using a customised Couch CMS (content management system) v2.0, which was hosted by a web server independent of the HP portal. Info Portal provided the relevant information containing educational text and multimedia for the patients. The portal contents could be modified or updated using the administration tools provided by the CMS.

The patients had access to the TRP using an 11.6 inch Microsoft Windows 10 compatible tablet. A custom Microsoft Store App (MyKnee) was developed under the Universal Windows Platform API (Application Programming Interface) using Microsoft Visual Studio 2017 (version 15.8). The application was responsible for providing the patient’s platform services in table 1 through a user-friendly graphical user interface and managing the hardware and communication resources.

The training management service tracked patients’ exercises by monitoring the knee angle23 using two SimpleLink Bluetooth low energy/Multi-standard SensorTag (CC2650STK) low-power sensors from Texas Instruments (Dallas, Texas). The patients wore the sensors on the operated leg—one on the thigh and one on the shin—while performing the exercises. When patients exercised, MyKnee tracked their progress by running real-time processing on the acquired motion data from the sensors via Bluetooth low-energy (BLE) with the 20 Hz sampling frequency. It should be mentioned that the programme was able to track those exercises involving a noticeable range of motion. Therefore, the patients could report the adherence manually for non-tracking exercises. The manual and the automatic-sensor-based report were available for the tracking exercise.

Semi-online compatibility and synchronisation

MyKnee App was capable of operating with or without an internet connection. In the absence of an internet connection (offline mode), the system was capable of using locally stored data and stored the requests in the corresponding outbox (sent reports, messages and exercise adherence). When an internet connection was operating, that is, while online, the app continuously updated the outboxes, sent reports and locally stored data.

This flexibility allowed patients to use the TRP regardless of internet connectivity, with the system operating using the latest locally stored update. The semi-online compatibility considerably enhances portability and user-friendliness of the application.

In offline mode, the application continuously monitors the internet connection and synchronises the data with the web server as soon as a stable internet connection is found. During online operation, full data synchronisation is performed within predefined intervals as well as in the process of launching and closing the application.

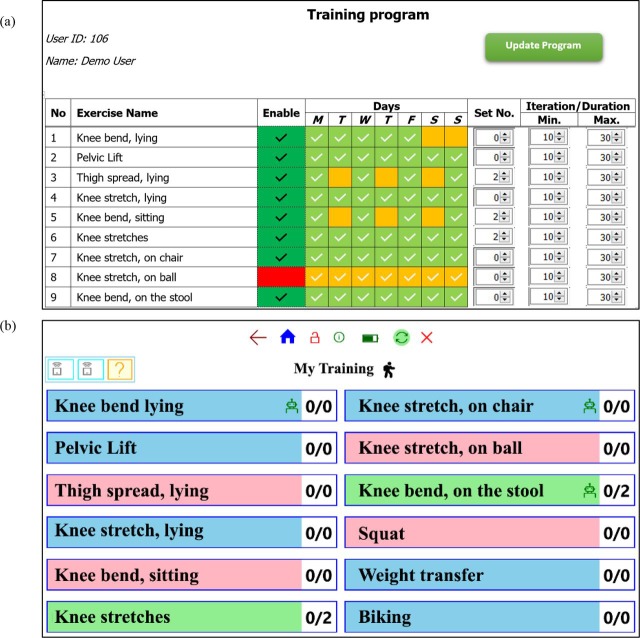

Individualisation

A very high level of flexibility and individualisation for the training programme was realised during the development process. Hence, the HPs were able to recommend, require or exclude each exercise for each patient, directing the patient as to whether they could, should or should not perform the exercise. The responsible HPs could also define the number of sets, minimum and maximum repetitions for each exercise, as well as specifying which days of the week the exercise should be included in the exercise programme. Accordingly, the training manager service in MyKnee app provided the user-friendly view of the individualised training programme by limiting the patient to the recommended and mandatory exercises. The patient was allowed to perform more exercises than the defined set numbers (among enabled exercises); however, the training managers stopped the patients from exceeding the maximum number of repetitions for each set in order to avoid over-training. Figure 2 shows the graphical user interface of the training programme in the HP’s and patient’s platforms for a demo patient.

Figure 2.

The graphical user interface of the individualised training programme. (A) Healthcare professional side. Each exercise can be recommended, mandatory or excluded. The number of sets for the recommended exercises is set to zero, while the excluded exercises are disabled and shown in red. The minimum and maximum number of repetitions could also be set for each exercise individually. The healthcare professionals could also enable the exercise for the specific days of the week. (B) The corresponding training programme is shown for the same demo patient on Thursday. The recommended, mandatory and excluded exercises are shown in blue, green and red. The number of the sets are shown with digits in front of the exercise name.

Furthermore, a high-degree of flexibility was provided for the patients using the reporting service. The patients were notified by the service to report the patient reported outcome (PRO) data within the predefined interval (but were also able to report PRO data at will).

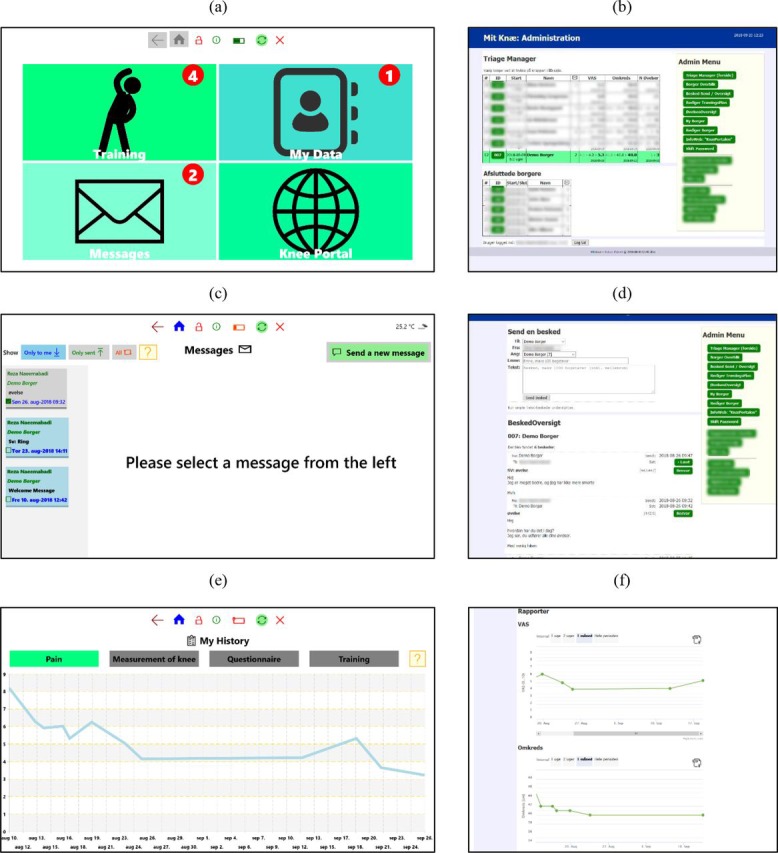

Graphical user interface

The graphical user interface (GUI) of the HP portal and the MyKnee app were designed and developed with users’ participation. The GUI of the MyKnee app followed the principle of using symbols, icons, and visual notification, and it was customised for both touchscreens and mouse/keyboard as user inputs. The HP portal was optimised for mouse and keyboard inputs and employed fewer graphical visualisations. Figure 3 compares the graphical user interface of the TRP for the patient’s and the HP’s platforms (left and right sides, respectively).

Figure 3.

Graphical user-interface of the telerehabilitation programme. The patient’s interface is shown on the left side, and the healthcare professional’s interface is shown on the right side. (A) The home page of a demo patient showing the available services. (B) The home page of the healthcare professional’s portal showing the list of the active and finished patients including a quick overview of each patient’s activities. The navigation bar is shown on the top, and red circles with numbers show the number of daily tasks to be completed. (C) The messaging environment of MyKnee app. The patient can switch between the received and sent messages as well as replaying or sending a new message. (D) Messaging platform of the healthcare professional. (E) Report history of the corresponding patient. Patients are able to zoom-in, zoom-out and scroll the report using the multitouch screen or mouse scroll. (F) Healthcare professional’s report presentation environment. The healthcare professional can see the report for the previous week, 2 weeks, 1 month and the entire period intervals. They are also able to export and download the report in PDF format.

Security, privacy and data protection

Each HP had his/her personalised authentication with a two-step log-in to the HP’s portal. All the processing was carried out on the server site, and the processed data were transformed to the HPs using HTTPS (hypertext transfer protocol secure) access. No personal or sensitive patient data were stored on the web server (healthcare portal).

The patient’s authentication was verified by Windows Hello biometrics, which is compatible with fingerprint and facial recognition sensors. In this study, a PQI My Lockey USB fingerprint sensor was mounted on the tablet. The fingerprint sensor is CE marked and has received a FIDO Alliance security certificate.24 The Windows 10 Hello authentication control uses artificial intelligence (AI), which ensures a false accept rate (FAR) below 0.002%.25 Furthermore, all locally stored data (messages, reports, settings, configurations) were encrypted by advanced encryption standard (AES).26 27 Webcam and microphone permissions were not granted to MyKnee application in order to ensure the patient's privacy. A daily encrypted backup of the application was also automatically generated on an external removable (microSD) memory mounted on the tablet in order to enable rapid backup of data in case of hardware and software damages.

Application

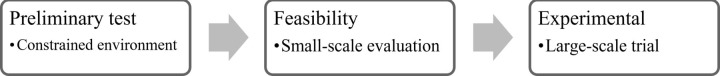

The TRP was designed and developed by engaging the user’s participation in the development process. The implementation and testing of the system are being evaluated in three phases (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Evaluation and testing phase of the sensor-based telerehabilitation programme.

A preliminary GUI and system stability test was carried out in the constrained environment in order to identify the practical issues of the TRP and patients’ experience.

A preliminary test and evaluation of the system were carried out by inviting users who had undergone a knee operation and were in an 8 week self-rehabilitation. The initial implementation of the TRP showed a high level of satisfaction among the users.

At present, the first experimental test of the TRP is taking place among a small group of patients by identifying and recruiting patients at Farsø Hospital, Aalborg University Hospital. The reliability and user-friendliness of the programme are being monitored. Further information about the protocol of the study is available in ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT03731208). Preliminary findings indicate a high level of user satisfaction.

Having examined the achieved results for the feasibility study, a large-scale randomised control trial can be carried out to investigate the short-term impact of telerehabilitation on postoperative rehabilitation compared with conventional rehabilitation.

Discussion

In this study, the requirements and specifications of a semi-online TRP for patients recovering from knee surgery was introduced and tested. In the design and development process, the goal was to overcome the identified barriers and limitations of conventional rehabilitation and to improve resource management using a TRP. It has been shown that asynchronous telerehabilitation and telehealth solutions can tackle the practical limitation of real-time video conference rehabilitations.28 29 Bini et al 20 reported non-inferiority outcomes achieved by an asynchronous video rehabilitation in comparison with traditional rehabilitation using 29 patients who had undergone total knee arthroplasty.

The introduced TRP has benefitted from a sensor-based telerehabilitation and exercise tracking approach. A few studies employed sensor technologies to track the patient’s performance during rehabilitation. Anton et al 30 introduced a telerehabilitation system using the Microsoft Kinect v1 sensor for monitoring the exercises. They have evaluated the feasibility of using the programme for patients who have undergone total hip replacement.31 Naeemabadi et al 23 have shown that Microsoft Kinect sensors have a practical limitation in tracking some of the exercises in the knee rehabilitation programme. Fung et al 32 reported Nintendo Wii Fit (Kyoto, Japan) could be used for rehabilitation of patients after total knee replacement. Piqueras et al 21 evaluated the effectiveness of employing two wearable motion sensors for 5 days after total knee arthroplasty.

In the developed TRP, establishing a two-way communication along with the HP’s intervention and an individualised training programme were highly emphasised. Hall et al 4 remarked that the therapist–patient relationship has a positive impact on the rehabilitation and treatment procedure. Lee et al 3 also noted that a tailor-made rehabilitation programme could improve exercise adherence.

Further studies are required to investigate the user satisfaction and usability of the TRP as well as potential improvements in accessibility and patients’ adherence using an interactive rehabilitation programme.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Knud Larsen for his valuable contribution in developing the healthcare professional platform on the telerehabilitation program. This study was supported by the Aage and Johanne Louis-Hansen Foundation, Aalborg University and Orthopedic Surgery Research Unit, Research and Innovation Center, Aalborg University Hospital, Aalborg, Denmark.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by Aage and Johanne Louis - Hansen Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Jüni P, Reichenbach S, Dieppe P. Osteoarthritis: rational approach to treating the individual. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2006;20:721–40. 10.1016/j.berh.2006.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Artz N, Elvers KT, Lowe CM, et al. Effectiveness of physiotherapy exercise following total knee replacement: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015;16 10.1186/s12891-015-0469-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee F-KI, Lee T-FD, So WK-W. Effects of a tailor-made exercise program on exercise adherence and health outcomes in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a mixed-methods pilot study. Clin Interv Aging 2016;11:1391–402. 10.2147/CIA.S111002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, et al. The influence of the therapist-patient relationship on treatment outcome in physical rehabilitation: a systematic review. Phys Ther 2010;90:1099–110. 10.2522/ptj.20090245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baker KR, Nelson ME, Felson DT, et al. The efficacy of home based progressive strength training in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1655–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kingston GA, Judd J, Gray MA. The experience of medical and rehabilitation intervention for traumatic hand injuries in rural and remote North Queensland: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 2015;37:423–9. 10.3109/09638288.2014.923526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saywell N, Taylor D. Focus group insights assist trial design for stroke telerehabilitation: a qualitative study. Physiother Theory Pract 2015;31:160–5. 10.3109/09593985.2014.982234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lemaire ED, Boudrias Y, Greene G. Low-bandwidth, Internet-based videoconferencing for physical rehabilitation consultations. J Telemed Telecare 2001;7:82–9. 10.1258/1357633011936200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Demiris G, Speedie SM, Finkelstein S. Change of patients' perceptions of TeleHomeCare. Telemed J E Health 2001;7:241–8. 10.1089/153056201316970948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Finkelstein SM, Speedie SM, Demiris G, et al. Telehomecare: quality, perception, satisfaction. Telemed J E Health 2004;10:122–8. 10.1089/tmj.2004.10.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Russell TG. Physical rehabilitation using telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:217–20. 10.1258/135763307781458886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Russell TG, Buttrum P, Wootton R, et al. Internet-based outpatient telerehabilitation for patients following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93:113–20. 10.2106/JBJS.I.01375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moffet H, Tousignant M, Nadeau S, et al. In-home telerehabilitation compared with face-to-face rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97:1129–41. 10.2106/JBJS.N.01066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tousignant M, Moffet H, Boissy P, et al. A randomized controlled trial of home telerehabilitation for post-knee arthroplasty. J Telemed Telecare 2011;17:195–8. 10.1258/jtt.2010.100602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tousignant M, Boissy P, Moffet H, et al. Patients' satisfaction of healthcare services and perception with in-home telerehabilitation and physiotherapists' satisfaction toward technology for post-knee arthroplasty: an embedded study in a randomized trial. Telemed J E Health 2011;17:376–82. 10.1089/tmj.2010.0198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moffet H, Tousignant M, Nadeau S, et al. Patient satisfaction with in-home telerehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: results from a randomized controlled trial. Telemed J E Health 2017;23:80–7. 10.1089/tmj.2016.0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boissy P, Tousignant M, Moffet H, et al. Conditions of use, reliability, and quality of audio/video-mediated communications during in-home rehabilitation teletreatment for postknee arthroplasty. Telemed J E Health 2016;22:637–49. 10.1089/tmj.2015.0157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tousignant M, Moffet H, Nadeau S, et al. Cost analysis of in-home telerehabilitation for post-knee arthroplasty. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e83–12. 10.2196/jmir.3844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tousignant M, Boissy P, Corriveau H, et al. In home telerehabilitation for older adults after discharge from an acute hospital or rehabilitation unit: a proof-of-concept study and costs estimation. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2006;1:209–16. 10.1080/17483100600776965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bini SA, Mahajan J. Clinical outcomes of remote asynchronous telerehabilitation are equivalent to traditional therapy following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized control study. J Telemed Telecare 2017;23:239–47. 10.1177/1357633X16634518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Piqueras M, Marco E, Coll M, et al. Effectiveness of an interactive virtual telerehabilitation system in patients after total knee arthoplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med 2013;45:392–6. 10.2340/16501977-1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Clemensen J, Rothmann MJ, Smith AC, et al. Participatory design methods in telemedicine research. J Telemed Telecare 2017;23:780–5. 10.1177/1357633X16686747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mr N, Dinesen B, Andersen OK, et al. Evaluating accuracy and usability of Microsoft Kinect sensors and wearable sensor for tele knee rehabilitation after knee operation In: Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies, 2018: 128–35. [Google Scholar]

- 24. FIDO Alliance FIDO certified solutions [Internet], 2017. Available: https://fidoalliance.org/certification/fido-certified-products/ [Accessed 3 Jan 2018].

- 25. Microsoft Corporation Windows Hello biometrics in the enterprise [Internet], 2017. Available: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/access-protection/hello-for-business/hello-biometrics-in-enterprise [Accessed 3 Jan 2018].

- 26. Fips N. 197: Announcing the advanced encryption standard (AES). Technol Lab Natl Inst Stand 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Daemen J, Rijmen V, Leuven KU. AES Proposal: Rijndael. Complexity 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baruffaldi F, Gualdrini G, Toni A. Comparison of asynchronous and realtime teleconsulting for orthopaedic second opinions. J Telemed Telecare 2002;8:297–301. 10.1177/1357633X0200800509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deshpande A, Khoja S, Lorca J, et al. Asynchronous Telehealth: a scoping review of analytic studies. Open Med 2009;3:39–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Anton D, Berges I, Bermúdez J, et al. A telerehabilitation system for the selection, evaluation and remote management of therapies. Sensors 2018;18. doi: 10.3390/s18051459. [Epub ahead of print: 08 May 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Antón D, Nelson M, Russell T, et al. Validation of a Kinect-based telerehabilitation system with total hip replacement patients. J Telemed Telecare 2016;22:192–7. 10.1177/1357633X15590019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fung V, Ho A, Shaffer J, et al. Use of Nintendo Wii Fit™ in the rehabilitation of outpatients following total knee replacement: a preliminary randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy 2012;98:183–8. 10.1016/j.physio.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Williams DP, Blakey CM, Hadfield SG, et al. Long-term trends in the Oxford knee score following total knee replacement. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:45–51. 10.1302/0301-620X.95B1.28573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]