Abstract

Introduction

Electronic health records (EHRs) can improve the quality and safety of care. However, the adoption and use of the EHR is influenced by several factors, including users’ perception.

Objectives

To undertake a systematic review of the literature to understand healthcare professionals’ perceptions about the adoption and use of EHRs in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries in order to influence the implementation strategies, training programme and policy development in the GCC region.

Method

A systematic literature search was undertaken on seven online databases to identify articles published between January 2006 and December 2017 examining healthcare professionals’ perception towards the adoption and use of EHR in the Gulf context.

Results

The fourteen articles included in this review identified both positive and negative perceptions of the role of EHR in healthcare. The positive perceptions included EHR benefits, such as improvements to work efficiency, quality of care, communication and access to patient data. Conversely, the negative perceptions were associated with challenges or risks of adopting an EHR, such as disruption of provider–patient communication, privacy and security concerns and high initial costs. The perceptions were influenced by personal factors (eg, age, occupation and computer literacy) and system factors (perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use).

Conclusion

Positive perceptions of EHRs by the healthcare professionals could facilitate the adoption of this technology in the Gulf region, particularly when barriers are addressed early. Negative perceptions may inform change management strategies during adoption and implementation. The perceptions should be further evaluated from a technology acceptance perspective.

Keywords: BMJ Health Informatics, health care, information management

Key messages.

Electronic health records (EHRs) are crucial for the provision of quality healthcare.

The adoption of EHRs is influenced by healthcare professionals’ perceptions of the systems.

The positive perceptions were related to the system’s benefits, including improvements to work efficiency, quality of care, patient safety, communication and access to patient data. Other benefits included reduced medical errors and reduced costs.

Barriers were associated with challenges or risks of using an EHR, disruption with workflow and provider–patient communication, privacy and security concerns, high initial costs and inadequate training.

The healthcare professionals’ perceptions of the EHR were influenced by personal factors (age, occupation, computer literacy and training in EHR), system factors (perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use) but not an organisational factor (management support).

Healthcare organisations should engage EHR system designers and users to ensure that the implemented systems meet the specific needs of healthcare professionals in terms of usefulness, usability and accessibility to improve acceptance and adoption levels.

Introduction

The traditional paper-based medical record is rapidly being replaced by modern health information technologies (HITs) to better manage patient information.1 2 Electronic health records (EHRs) can assist healthcare providers in generating, storing and retrieving vital patient information, ranging from medical histories to lab diagnostics, for the provision of high-quality care at different levels.3–5 EHRs are crucial for improving patient safety, quality of care and the efficiency of patient care delivery, as well as reducing medical errors and healthcare costs.6 7 Menachemi and Collum further note that the system assists healthcare providers to easily share and access patient data at any point of care, resulting in enhanced delivery of care.8 These benefits have been associated with positive perceptions of the EHRs by healthcare professionals.9 10 Similarly, patients have largely reported positive perceptions and high satisfaction with the use of EHRs mainly due to benefits related to access to personal health records and acting as an educational resource despite having few concerns, such as disruption of doctor–patient interaction and privacy issues11 12 Thus, the EHR has emerged as an important tool for enhancing efficiency in healthcare processes, facilitating information sharing between healthcare providers themselves and between healthcare providers and their patients, and improving the quality of care as well as patient safety.

Due to these perceived benefits of EHRs in health service provision, the systems are increasingly adopted in various healthcare settings across the world. The countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), namely Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain have also increased their investments in various forms of HITs to improve efficiency and delivery of healthcare services in hospitals and primary care centres.13 For example, the UAE launched a health information system (HIS), known as Wareed in 2011 to link electronic medical records in all public hospitals and clinics across Dubai and the Northern Emirates to improve efficiency in the public healthcare system.14 15 By the end of 2010, Oman had implemented the national repository of EHRs15 while Saudi Arabia committed $1.1 billion between 2008 and 2011 for the development of E-health programme and implementation of various health information tools, including EHRs to improve health and care services as part of its E-health strategy in Saudi Vision 2030.16 Despite these tremendous efforts in EHR adoption, there have also been notable challenges and barriers, such as increased costs during the implementation,17 18 privacy concerns19 and user acceptance.1 20 21 Khoja and colleagues13 noted that although cost/benefit analysis needs to be determined, the increasing demand and misuse of health technologies will most likely increase the overall costs. These challenges are more noticeable in the GCC nations and other developing countries compared with those with advanced economies because they still have less developed infrastructure and governance.22

Several other factors, such as the lack of adequate implementation policies, inadequate staff capabilities and capacity and distrust in the system have also been cited to contribute to the low adoption rates of EHRs and related HITs in the GCC countries.22 23 In relation to healthcare professionals who are the primary users of EHR systems in healthcare settings, their capabilities, including lack of the requisite skills and knowledge to use the systems due to lack of or inadequate training in health applications that discourage their use have been shown to have negative impacts on EHR adoption and use.13 23 Furthermore, healthcare professionals’ perception appears to play a significant role in EHR adoption and use with several theories and models predicting technology acceptance, such as the Technology Acceptance Model postulating that users’ attitude is a significant determinant of acceptance and use of new technology. However, little is known about the perceptions of healthcare professionals on the adoption and use of EHRs in healthcare settings in the GCC context. The objective of this paper is to report the findings from a systematic review of the literature examining the perceptions of healthcare professionals towards the adoption and use of EHRs in order to influence the implementation strategies, training programme and policy development in the GCC region. Although implementation and adoption are often used interchangeably, Murphy24 asserted that these terms differ in that the former is a short-term process of introducing an EHR system while adoption focuses on the long-term success through various strategies, such as providing adequate staff training. Conversely, the concept of use refers to actual utilisation of the EHR systems by the individual users to perform various functions during the process of care provision.25

Methods

Search strategy

Seven electronic databases (Scopus, PubMed, Proquest, Science Direct, Informit Health Collection, CINAHL and Medline via OvidSP) were systematically searched to identify articles published between January 2006 and December 2017 examining the healthcare professionals’ perceptions about the adoption and use of EHR in healthcare settings in the GCC. The search string was: (perception OR attitude OR perspective OR beliefs) AND (electronic health record OR EHR OR electronic medical record OR EMR OR electronic record OR digital record OR digital medical record OR digital health record OR digitised record OR digitized record OR electronic health information system OR health information system OR HIS OR ehealth OR digital health) AND (GCC OR gulf cooperation council OR gulf countr* OR Bahrain OR Kuwait OR Oman OR Qatar OR Saudi Arabia OR United Arab Emirates OR UAE OR middle east). Online supplementary table 1 shows the complete search strategy using an example of PubMed database.

bmjhci-2019-100099supp001.pdf (39.8KB, pdf)

Article selection

A priori inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to guide article selection for inclusion. Specifically, an article was included if it meets all of the following criteria: (1) examined the perceptions of healthcare providers towards the adoption or use of EHR in healthcare prior to, during and after implementation; (2) reported factors influencing users’ perceptions; (3) was conducted in any of the GCC countries listed in the search terms; (4) was a peer-reviewed, empirical research paper; (5) was published between January 2006 and December 2017; (6) the full-text of the article was available for review and (7) was published in English or Arabic language. Review articles, opinions and commentaries were excluded from this review.

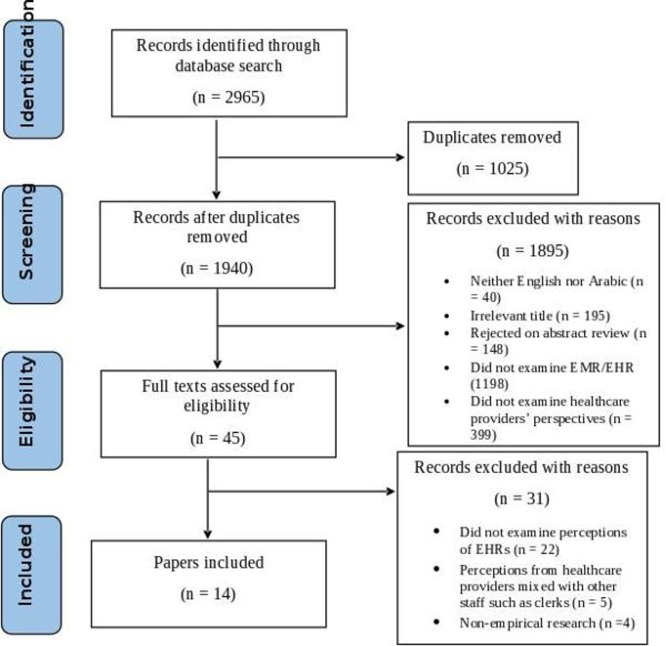

Applying the PRISMA approach26 for article selection, the online software Covidence was used to facilitate article selection. After removing duplicate articles, two reviewers (BA and KB-H) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the identified articles against the eligibility criteria. The full-text of selected articles were then examined independently by the two reviewers, followed by process of concordance. The reviewers then extracted relevant titles from the reference lists of the selected articles, and the above screening process was repeated until saturation was reached, and there was an agreement between the two reviewers. Figure 1 summarises this process.

Figure 1.

Study selection process. EHRs, electronic health records; EMR, electronic medical records.

Data quality, analysis and presentation

Each article was reviewed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)27 to assess the quality and the risk of bias. The article quality was evaluated based on five criteria for each category of study design. A scoring system of 0, 1 and 2 for ‘No’, ‘Can’t tell’ and ‘Yes’ for each criterion was used. Since MMAT also has two screening questions that were scored in the same manner, the total quality score in this systematic review was 14. Bibliometric information was then extracted from the selected articles, including the author/s names, the purpose of the paper and key findings of the study. They were then thematically analysed using an inductive approach by author BA, then reviewed by KB-H and MA, to identify the common themes using the approach described by Braun and Clarke.28

Results

Applying the article selection process detailed above, 14 articles were selected for inclusion in this review. The selection process and the number of records excluded at each stage is presented in figure 1.

Selected articles varied across a number of areas, as shown in table 1. More than half of the articles8 were conducted in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia29–36 and the remaining in other four countries of the GCC: Oman,37 38 Kuwait,39 40 UAE41 and Bahrain.42 Nine papers were published within the last 5 years, that is, between 2014 and 2019.29 30 32–36 41 42 A variety of settings are represented, with ten articles examining the hospital setting,29–38 three in primary health centres,39–41 and one examining both hospitals and primary health.42 Furthermore, the articles varied in their participant cohorts, including physicians,29 34 35 37 38 40 41 nurses,30 33 or a combination of occupations.31 32 36 39 42 Study designs included cross-sectional using surveys,29–40 42 or a focus group interviews of physicians.41 All articles had a high quality score of at least 12 except one31 which had a score of 9.

Table 1.

Selected articles description

| Article # | Author/s | Year of publication | Country | Study design | Study setting | Types of participants | Number of participants |

| 29 | Shaker et al | 2015 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional survey | Hospital | Physicians | 317 |

| 30 | El Mahalli | 2015 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | Hospital | Nurses | 185 |

| 31 | Khalifa | 2013 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | Hospital | Healthcare professionals | 158 |

| 32 | Hasanain et al | 2015 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | Hospital | Physicians, nurses, pharmacists, laboratory staff, receptionists, administrators and others | 333 |

| 33 | Asiri et al | 2014 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | Hospital | Nurses | 333 |

| 34 | Alzobaidi et al | 2016 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | Hospital | Physicians | 129 |

| 35 | Alharthi et al | 2014 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | Hospital | Physicians | 115 |

| 36 | Alasmary et al | 2014 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | Hospital | Physicians and nurses | 112 |

| 37 | Al-Mujaini et al | 2011 | Oman | Cross-sectional survey | Hospital | Physicians | 141 |

| 38 | Al Farsi and West | 2006 | Oman | Survey | Hospital | Physicians | 66 |

| 39 | Alsaleh and Al-Azmi | 2008 | Kuwait | Cross-sectional | Primary care | Physicians, pharmacists and receptionists | 839 |

| 40 | Al-Azmi et al | 2008 | Kuwait | Cross-sectional | Primary care | Physicians | 321 |

| 41 | Al Alawi et al | 2014 | UAE | Cross-sectional | Primary care | Physicians | 23 |

| 42 | Abdulla et al | 2016 | Bahrain | Cross-sectional | Hospital and primary care | Doctors, nurses, lab specialists, clerk and others | 152 |

Article purpose and key findings

Five articles examined healthcare professionals’ perceptions of EHRs in their practice settings.29 32 34 37 40 Users’ satisfaction with these systems was evaluated in four articles.35 38 39 41 Barriers of adopting HITs were also explored from the providers’ perspectives in two articles.30 31 Lastly, three articles evaluated users’ satisfaction with an EHR in relation to what they perceived to be influencing factors.33 36 42

Many of the articles reported findings related to healthcare professionals’ perceptions of the benefits and barriers to implementing EHRs, and factors affecting the perceptions of healthcare professionals towards EHR. This is explored in greater detail in the next section. In five papers, positive perception and high overall satisfaction with the EHRs among healthcare professionals were reported.29 33 34 40 41 Conversely, two articles reported a negative perception and low satisfaction with the EHRs.35 37 For instance, Alharthi and colleagues35 reported less than half (48.7%) of respondents stated they were satisfied with the EHR. Table 2 presents the purpose and key findings of the articles.

Table 2.

Selected articles purpose and key findings

| Article # | Paper author and year | Purpose | Key findings |

| 29 | Shaker et al, 2015 | To determine the physicians’ perception about electronic medical record system (EMRs) in the context of its productivity in order to improve its functionality and advantages. | The majority of the respondents perceived EMRs to have positive impacts. |

| 30 | El Mahalli, 2015 | To assess the adoption and barriers to the use of an EHR by nurses at three governmental hospitals implementing the same EHR software and functionalities in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. | The respondents reported several barriers to the adoption of EHRs in hospitals. The most frequently cited include loss of access to medical records due to computer or power failure, lack of continuous training/support from IT staff, additional time for data entry, system hanging up, the complexity of technology and lack of system customisability. |

| 31 | Khalifa, 2013 | To identify, categorise and analyse barriers perceived by different healthcare professionals to the adoption of EMRs in order to provide suggestions on beneficial actions and options. | Human and financial barriers are the main challenges to the successful implementation and adoption of EMRs. |

| 32 | Hasanain et al, 2015 | To examine both the knowledge and preferences of current or potential EMR users, at seven hospitals in three cities, within the western region of Saudi Arabia. | Lack of knowledge or experience using EMRs and staff resistance were the main barriers to EMR implementation in Saudi Arabia. |

| 33 | Asiri et al, 2014 | To explore the direct and indirect effects of the organisational factors (ie, organisational support, adequate training and user involvement) and the professional factors (ie, nurse autonomy, organisational citizenship behaviour, and nurse–client relationship) on nurses’ attitude and acceptance of the EMR using the proposed model in King Abdul Aziz Medical City (KAMC). | Nurses had varied attitudes towards EMR/EHR, but the majority, including those of KAMC had a positive attitude. |

| 34 | Alzobaidi et al, 2016 | To assess the readiness of the physicians in Al-Hada Military Hospital in Taif city toward implementing EMR. | Physicians had positive attitudes that favour the adoption of EMRs. |

| 35 | Alharthi et al, 2014 | To measure physician satisfaction with a recently introduced electronic medical record (EMR) and to determine which of the individual attributes of EMR were related to physician satisfaction. | Majority of the physicians had low overall satisfaction with the system. |

| 36 | Alasmary et al, 2014 | To explore the association between age, occupation and computer literacy and clinical productivity and users’ satisfaction of the newly implemented EMR at PSMMC as well as the association of user satisfaction with age and position | EMR users with high computer literacy skills were more satisfied with using EMR than users with low computer literacy skills. |

| 37 | Al-Mujaini et al, 2011 | To evaluate the knowledge, attitude and practice of physicians towards the EMR system. | Majority of the respondents had a negative perception towards EMR. |

| 38 | Al Farsi and West, 2006 | To assess physician satisfaction through the identification of positive and negative impacts of EMR after introduction in Oman | EMR implementation had positive and negative impacts, and the physicians were satisfied with the system. |

| 39 | Alsaleh and Al-Azmi | To evaluate the user interaction satisfaction with the newly implemented EMRs in the primary healthcare centres in Kuwait and to compare the pattern of reactions to the implemented EMRs among the PHC providers in Kuwait. | The healthcare providers had an overall positive attitude of the EHRs regarding the system’s benefits and ease of use; however, these attitudes were influenced by various factors, including computer experience, education and training, age and length of experience. |

| 40 | Al-Azmi et al, 2008 | To elicit the opinion of the physician working in the primary healthcare facilities in Kuwait to the newly introduced EMRs in the government clinics of Kuwait as well as their appreciation of its utilities and advantages | Respondents were positive and satisfied with the EHR/EMR. |

| 41 | Al Alawi et al, 2014 | To explore physician satisfaction with an EMR system, to identify and explore the main limitations of the system and finally to submit recommendations to address these limitations | Physicians are satisfied with the EMR and have a positive perception regarding its application. |

| 42 | Abdulla et al, 2016 | To examine the factors that affect users’ satisfaction with the current Health Record System in the Kingdom of Bahrain | Information quality and system quality had an indirect effect on user satisfaction through trust. |

Themes

From the reviewed articles, three main themes related to the healthcare professionals’ perceptions of EHRs emerged. These included: (1) perceived benefits of EHRs, (2) perceived barriers to EHR adoption and use, and (3) perceived influencing factors of EHR perceptions. The detailed themes are presented in table 3 with the different shades of blue colour, representing how much the themes were discussed. The most commonly reported theme is represented by the darkest shade.

Table 3.

Summary of themes

| Reference | Perceived benefits of using EHR/EMR | Perceived barriers to adopting EHR/EMR | ||||||||||||||

| Improved access to clinical data | Improved quality of care | More efficient workflow | Improved patient safety | Improves communication | Good source of education | Reduces error | Reduces costs | Security and privacy issues | Workflow disruption | Communication disruption | Complicated and not user-friendly | Inadequate training | High initial cost | EHR/ EMR literacy | Poor English language | |

| Shaker et al, 201529 | ||||||||||||||||

| El Mahalli, 201530 | ||||||||||||||||

| Khalifa, 201331 | ||||||||||||||||

| Hasanain et al., 201532 | ||||||||||||||||

| Asiri et al, 201433 | ||||||||||||||||

| Alzobaidi et al\, 201634 | ||||||||||||||||

| Alsaleh and Al-Azmi, 200839 | ||||||||||||||||

| Al-Mujaini et al, 201137 | ||||||||||||||||

| Alharthi et al, 201435 | ||||||||||||||||

| Al-Azmi et al, 200840 | ||||||||||||||||

| Alasmary et al, 201436 | ||||||||||||||||

| Al Farsi and West, 200638 | ||||||||||||||||

| Al Alawi et al, 201441 | ||||||||||||||||

| Abdulla et al, 201642 | ||||||||||||||||

Perceived benefits of EHRs

The articles reported that healthcare professionals perceived the use of EHRs to have several benefits. These included using EHRs to make workflow more efficient,29–31 33 36–38 40–42 improved access to clinical data,29 36 38 40–42 positive impact on patient safety,29 33–35 38 39 42 and improved communication between providers or between provider and patient.29 38–40 For instance, 92% of the respondents in a study by Al-Azmi et al40 reported that they could more easily access a patient’s medical history in an EHR compared with a paper record. Al Farsi and West38 reported 95% of physicians stated that the EHR improves communication between hospital departments. Moreover, EHRs were reported to reduce both medical errors29 30 33 34 36 38 39 42 and long-term healthcare costs.29 33 Alzobaidi et al 34 reported 84% of responders had a high level of agreement that the EHR has a role in reducing medical errors, with Al Farsi and West38 reporting 67% agreement level with the role. Overall, the majority of healthcare professionals perceived EHRs to have numerous benefits that enhance healthcare delivery.

Perceived barriers to EHR/EMR adoption and use

The review of the selected literature also identified several perceived barriers to adopting and using EHRs. This included the complexity of the system and an interface that is not user friendly,30 32 35 37 38 40–42 where design disrupted as opposed to enhanced workflow,29–31 35 37 38 or where it negatively impacted as opposed to supporting communication between the healthcare providers and their patients.30 31 35 37 41 El Mahalli30 reported the majority (81.6%) of the respondents agreed that EHRs are complex and difficult to use. Shaker et al 29 reported only 35.1% of the respondents agreed that EHR enhances workflow. Security and privacy of the patient data was also a concern to healthcare professionals.38 41 At an individual level, inadequate training in how to use the EHR,30 31 33 34 36 37 lack of EHR literacy,32 39–41 and limited English language32 posed significant barriers. Hasanain et al 32 reported 12.6% of respondents had poor English language that limited their ability to use EHR. El Mahalli30 also found that the lack of continuous training from the IT department was a significant barrier to implementing EHR in Saudi hospitals, with 85.9% of healthcare professionals citing the barrier. Lastly, the systems were also perceived to be costly during the implementation phase.31

Perceived influencing factors of EHRs

The perceptions of the healthcare professionals were found to be influenced by various factors across the three levels of the individual, the organisation and the system. Individual factors, including age, occupation and level of computer literacy, were found to have a significant positive association with users’ satisfaction with EHRs.36 40 Alasmary et al 36 reported a significant correlation between EHR satisfaction and age (r=0.263, p=0.011) and level of computer literacy (r=0.343, p<0.01). Although the authors did not report whether higher satisfaction with the EHR was observed among the younger or older professionals, they noted that satisfaction was higher with higher computer literacy skills. Al-Azmi et al 40 also reported EHR satisfaction was significantly correlated with age (F=0.033, p<0.001) with younger professionals more satisfied than older ones. There was also a significant difference in perception of the EHR benefit that EHR results in better communications between younger and older healthcare professionals with the former group having a higher agreement level (F=3.659, p=0.0269). However, the older and younger professionals did not significantly differ in perception that EHR enhances efficiency (F=0.966, p=0.405) and improves performance (F=1.612, p=0.201). Computer literacy was also found to have a highly significant positive relationship with EHR literacy (r=0.44, p<0.001).32 Lastly, the level of English proficiency was also highly significantly correlated with computer literacy (r=0.44, p<0.001) and electronic medical record (EMR) literacy (r=0.31, p<0.001).32

With regards to professional and organisational factors, Asiri et al 33 reported a weak but positive significant relationship between nurses’ attitude towards EHR and nurse involvement (β=0.1176, p<0.05), nurse-client relationship (Beta=0.0044, p<0.05) and adequate training (β=0.1645, p<0.05). Conversely, there was no association between nurses’ attitude towards EHR and management support (β=0.0003, p>0.05), nurse autonomy (β=0.0016, p>0.05), or organisational citizenship behaviour that includes identifying with the organisation of work (β=0.0045, p>0.05).

Lastly, the system factors that had a significant influence on attitude towards EHRs included perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. The two system attributes were found to have a positive moderate significant relationship with the attitude towards EMR usage and acceptance perceived usefulness (β=0.51, p<0.05) and perceived ease of use (β=0.19, p<0.05).33 Another study examined these aspects in terms of system quality, which include efficiency, reliability, service quality, ease of use and responsiveness as well as information quality based on content and accuracy.42 However, a positive significant relationship was found only between service quality and user satisfaction (t=3.210, p<0.05).

Discussion

The findings in this systematic review identified that healthcare professionals in GCC countries have varied perceptions of the EHRs regarding the systems’ benefits and challenges or risks of use. However, the perceptions are largely influenced by various factors that can be classified at the individual, organisational or system-level and are likely to affect the successful adoption of the EHR.

The review identified a perception that the adoption of EHRs results in improvements across access to clinical data, communication, work efficiency, quality of care, patient safety including reduced medical errors and costs. These findings are concurrent with other studies.9 43–45 King and colleagues noted that majority of physicians in the USA perceived the EHR to be useful in ambulatory care practice due to its benefits in enhancing overall patient care, enabling access of patient data remotely and reducing medical errors.43 Further, Tharmalingam et al 45 reported that healthcare professionals in Canada perceived the interconnected EHRs to be valuable in improving the quality of care since they enable access to medical data at any point of care. Thus, the positive perception of an EHR by healthcare professionals in GCC countries identified in this review could be attributed to the perceived benefits of EHR. Krousel-Wood et al 9 similarly found a positive association between EHR benefits and perceptions of the EHR. These findings suggest that healthcare providers in the GCC countries have positive perceptions of EHRs due to their potential benefits; thus, they are more likely to adopt the system which would increase the adoption and use in healthcare.

The negative perceptions identified in this review are largely related to the challenges and risks of using an EHR. This includes complex and non-user-friendly systems, workflow and communication disruptions, increased workload, security and privacy issues, high initial costs, inadequate training and lack of EHR literary as well as language challenges. A previous study in the USA46 reported similar challenges, including complexity and lack of adequate technical support. Moreover, an international survey involving 45 countries from different settings found a negative perception and low satisfaction with EHR in 67% of respondents, citing issues such as poor usability, limited functionality and lack of user training.47 Negative perceptions have been found to be negatively associated with user satisfaction and acceptance of technology.45 48 Thus, the identified negative perceptions towards EHR among the healthcare professionals in the GCC countries could act as a potential barrier to the successful adoption of EHRs in these settings as opposed to positive perceptions that are perceived as facilitators for EHR adoption.49 50

This systematic review also identified that healthcare professionals’ attitude towards EHR is influenced by various factors. Specifically, they included personal, organisation or system factors such as age, perceived usefulness and organisational support. Previous studies have also shown the influence of these factors on healthcare professionals’ perception of EHR.21 50–52 At the individual level, Duarte and Azevedo51 showed that younger professionals in Brazil were more satisfied with EHRs than older counterparts which is similar to the findings of this systematic review. Moreover, computer literacy and training have been found to be positively associated with increased users’ satisfaction and acceptance of technology.21 50 52 The system factors including perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use were found to be positively associated with healthcare professionals’ perceptions of EHRs. Previous studies have similarly reported that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of a system could increase acceptance and use of a technology that facilitate adoption.48 53 Tubaishat52 also found that these system attributes were associated with positive perceptions of EHRs among Jordanian nurses. Although this systematic review did not find a significant association between management support and nurses’ attitudes towards an EHR, previous studies have shown that organisational factors such as organisational culture and IT support have a significant influence on users’ perceptions that affect the adoption and implementation of the EHRs.54 55 In the view of these findings, it is important for healthcare organisations in the GCC countries to take into account these factors that are likely to influence users’ perceptions of EHRs and ultimate adoption. Consideration of the influencing factors will also help in early identification of barriers to EHR adoption and adequately addressing for better adoption results.

The findings in this review identified perceptions that are unique to the GCC considering that the member states have similar social, economic and political characteristics.22 The countries are in a crucial stage of adopting EHR and other HISs with their healthcare systems undergoing a gradual change in infrastructural developments fuelled by the growing economy. They have also experienced increased diversity in the health workforce. Thus, this review identifies healthcare professionals’ perceptions as a key area of improving adoption and implementation of EHR in GCC healthcare settings. Furthermore, the review underscores the importance of deploying effective training programme targeting all the healthcare professionals irrespective of age or occupation to improve their skills and knowledge of the health information management systems that in turns improves adoption. This systematic review also highlights the need for the GCC nations to adopt EHRs that meet the specific needs and preferences of their users, such as those designed in Arabic, which is the most spoken language in these settings, rather than English-based systems that create language challenges. This would require the involvement of the healthcare providers, who are the end-users of the EHR systems, the system developers and healthcare organisations in the GCC in all stages of the design process to address the implementation challenges related to usability and customisability of the system. Lastly, governments of the GCC countries should develop appropriate and favourable policies for EHR implementation in all government and private facilities to improve overall adoption rates at the national levels as part of a strategy for providing high-quality care to the citizens.

Conclusion

This systematic review evaluated the current literature reporting healthcare professionals’ perceptions of EHR adoption in the GCC countries and the factors influencing these perceptions. Professionals in these countries perceived EHR to be beneficial in healthcare service provision by improving patient safety and quality of care, access to patient health information, workflow and communication between healthcare providers and patients as well as reducing healthcare costs in the long run. The perception of these benefits could facilitate the adoption of EHRs in these settings. Conversely, the impact on workflow and communication disruptions, inadequate training, high initial costs and privacy and security issues may hinder the successful adoption of an EHR. The healthcare professionals’ perceptions of the EHRs are, however, influenced by various factors at the individual, organisational or system levels. Therefore, the governments and policymakers in GCC countries should adequately understand the factors that are likely to affect the successful adoption and use of EHRs. Significant emphasis should be placed on human factors with healthcare professionals targeted as the end-users of the systems.

Footnotes

Contributors: BA conceived and planned the study. BA and KB-H conducted the review. BA drafted the manuscript. KB-H and MA provided guidance and critical review of the manuscript, and finalised it for submission. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository.

References

- 1. Buntin MB, Burke MF, Hoaglin MC, et al. The benefits of health information technology: a review of the recent literature shows predominantly positive results. Health Aff 2011;30:464–71. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hillestad R, Bigelow J, Bower A, et al. Can electronic medical record systems transform health care? potential health benefits, savings, and costs. Health Aff 2005;24:1103–17. 10.1377/hlthaff.24.5.1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alotaibi YK, Federico F. The impact of health information technology on patient safety. Saudi Med J 2017;38:1173–80. 10.15537/smj.2017.12.20631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sweeney J. Healthcare informatics. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics 2017;21:4–1. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reid PP, Compton WD, Grossman JH, et al. Information and communications systems: the backbone of the health care delivery system. building a better delivery system: a new Engineering/Health care partnership. National Academies Press (US), 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Garets D, Davis M. Electronic medical records vs. electronic health records: Yes, there is a difference. Policy white paper Chicago, HIMSS Analytics 2006:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoover R. Benefits of using an electronic health record. Nursing 2016;46:21–2. 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000484036.85939.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Menachemi N, Collum TH. Benefits and drawbacks of electronic health record systems. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2011;4:47 10.2147/RMHP.S12985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krousel-Wood M, McCoy AB, Ahia C, et al. Implementing electronic health records (EHRs): health care provider perceptions before and after transition from a local basic EHR to a commercial comprehensive EHR. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018;25:618–26. 10.1093/jamia/ocx094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Secginli S, Erdogan S, Monsen KA. Attitudes of health professionals towards electronic health records in primary health care settings: a questionnaire survey. Inform Health Soc Care 2014;39:15–32. 10.3109/17538157.2013.834342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee WW, Alkureishi MA, Ukabiala O, et al. Patient perceptions of electronic medical record use by faculty and resident physicians: a mixed methods study. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:1315–22. 10.1007/s11606-016-3774-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Lusignan S, Mold F, Sheikh A, et al. Patients' online access to their electronic health records and linked online services: a systematic interpretative review. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006021 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khoja T, Rawaf S, Qidwai W, et al. Health care in Gulf cooperation Council countries: a review of challenges and opportunities. Cureus 2017;9 10.7759/cureus.1586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Council US-UAEB The U.A.E. healthcare sector, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamid M, Ali M, Hamid B, et al. Hospital information systems: the status and approaches in selected countries of the middle East. Electronic physician 2018;5:6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Noor A. The utilization of e-health in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology 2019;6:1229–39. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Palabindala V, Pamarthy A, Jonnalagadda NR. Adoption of electronic health records and barriers. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2016;6:32643 10.3402/jchimp.v6.32643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ajami S, Bagheri-Tadi T. Barriers for adopting electronic health records (EHRs) by physicians. Acta Inform Med 2013;21:129–34. 10.5455/aim.2013.21.129-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aselton P, Affenito S. Privacy issues with the electronic medical record. Annals of Nursing and Practice 2014;1. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jung S-R. The perceived benefits of healthcare information technology adoption: construct and survey development, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Al-Harbi A. Healthcare Providers’ Perceptions towards Health Information Applications at King Abdul-Aziz Medical City, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2011;2:10–13. 10.14569/IJACSA.2011.021003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alkraiji A, Osama E-H, Fawzi A. Health informatics opportunities and challenges: preliminary study in the cooperation Council for the Arab states of the Gulf. Journal of Health Informatics in Developing Countries 2014;8. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mogli G. Challenges of implementing electronic health records in Gulf cooperation Council countries. Journal of BioMedical Informatics 2011;2:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Murphy K. Moving from EHR implementation to EHR adoption: EHRIntelligence, 2012. Available: https://ehrintelligence.com/news/moving-from-ehr-implementation-to-ehr-adoption [Accessed 11 Nov 2019].

- 25. Huang M, Gibson C, Terry A. Measuring electronic health record use in primary care: a scoping review. Appl Clin Inform 2018;09:015–33. 10.1055/s-0037-1615807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hong QN, Pluye P, Bregues S, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. IC Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shaker HA, Farooq MU, Dhafar KO. Physicians' perception about electronic medical record system in Makkah region, Saudi Arabia. Avicenna J Med 2015;5:1–5. 10.4103/2231-0770.148499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. El Mahalli A. Adoption and barriers to adoption of electronic health records by nurses in three governmental hospitals in eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. Perspect Health Inf Manag 2015;12:1f. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khalifa M. Editor barriers to health information systems and electronic medical records implementation a field study of Saudi Arabian hospitals. Elsevier B.V, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hasanain RA, Vallmuur K, Clark M. Electronic medical record systems in Saudi Arabia: knowledge and preferences of healthcare professionals. Journal of Health Informatics in Developing Countries 2015;9. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Asiri H, AlDosari B, Saddik B. Nurses’ attitude, acceptance and use of electronic medical records (EMR) in King AbdulAziz medical city (KAMC) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Merit Res Journals 2014;2:66–77. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alzobaidi H, Zolaly E, Sadeq B, et al. Attitudes toward implementing electronic medical record among Saudi physicians. Int J Med Sci Public Health 2016;5:1244 10.5455/ijmsph.2016.06032016392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alharthi H, Youssef A, Radwan S, et al. Physician satisfaction with electronic medical records in a major Saudi government Hospital. J Taibah Univ Med Sci 2014;9:213–8. 10.1016/j.jtumed.2014.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Alasmary M, El Metwally A, Househ M. The association between computer literacy and training on clinical productivity and user satisfaction in using the electronic medical record in Saudi Arabia. J Med Syst 2014;38:69 10.1007/s10916-014-0069-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Al-Mujaini A, Al-Farsi Y, Al-Maniri A. Satisfaction and perceived quality of an electronic medical record system in a tertiary hospital in Oman. Oman Med J 2011;26:324–8. 10.5001/omj.2011.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Farsi MA, West DJ. Use of electronic medical records in Oman and physician satisfaction. J Med Syst 2006;30:17–22. 10.1007/s10916-006-7399-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alsaleh KA, Al-Azmi SF. Care providers’ experience with the newly implemented electronic medical record system at the primary health care centers in Kuwait. Bull Alex Fac Med 2008;44. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Al-Azmi SF, Saleh K, Ojayan O. Physicians’ perceptions about the newly implemented electronic medical records systems at the primary health care centers in kuwait. Alex J Med 2008;44:303–12. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Al Alawi S, Al Dhaheri A, Al Baloushi D, et al. Physician user satisfaction with an electronic medical records system in primary healthcare centres in al Ain: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005569 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Abdulla AE, Ahmed SY, Alnoaimi MA, et al. Users' satisfaction with the electronic health record (EHR) in the Kingdom of Bahrain. consumer-driven technologies in healthcare: breakthroughs in research and practice. IGI Global, 2016: 319–44. [Google Scholar]

- 43. King J, Patel V, Jamoom EW, et al. Clinical benefits of electronic health record use: national findings. Health Serv Res 2014;49:392–404. 10.1111/1475-6773.12135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meigs SL, Solomon M. Electronic health record use a bitter pill for many physicians. Perspectives in health information management 2016;13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tharmalingam S, Hagens S, Zelmer J. The value of connected health information: perceptions of electronic health record users in Canada. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2016;16:93 10.1186/s12911-016-0330-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ramdoss S. Investigating the non-adoption of electronic health records in primary care, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Topaz M, Ronquillo C, Sarmiento RF, et al. Nurse informaticians report low satisfaction and multi-level concerns with electronic health records: results from an international survey. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, American Medical Informatics Association, 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gagnon M-P, Ghandour EK, Talla PK, et al. Electronic health record acceptance by physicians: testing an integrated theoretical model. J Biomed Inform 2014;48:17–27. 10.1016/j.jbi.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ancker JS, Singh MP, Thomas R, et al. Predictors of success for electronic health record implementation in small physician practices. Appl Clin Inform 2013;4:12–24. 10.4338/ACI-2012-09-RA-0033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Morton ME, Wiedenbeck S. Ehr acceptance factors in ambulatory care: a survey of physician perceptions. Perspectives in Health Information Management/AHIMA, American Health Information Management Association 2010;7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Duarte JG, Azevedo RS. Electronic health record in the internal medicine clinic of a Brazilian university hospital: expectations and satisfaction of physicians and patients. Int J Med Inform 2017;102:80–6. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tubaishat A. Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of electronic health records among nurses: application of technology acceptance model. Informatics for Health and Social Care 2018;43:379–89. 10.1080/17538157.2017.1363761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Holden RJ, Asan O, Wozniak EM, et al. Nurses’ perceptions, acceptance, and use of a novel in-room pediatric ICU technology: testing an expanded technology acceptance model. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2016;16:145 10.1186/s12911-016-0388-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lambooij MS, Drewes HW, Koster F. Use of electronic medical records and quality of patient data: different reaction patterns of doctors and nurses to the hospital organization. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2017;17:17 10.1186/s12911-017-0412-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sidek YH, Martins JT. Perceived critical success factors of electronic health record system implementation in a dental clinic context: an organisational management perspective. Int J Med Inform 2017;107:88–100. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjhci-2019-100099supp001.pdf (39.8KB, pdf)