ABSTRACT

The RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine will undergo a pilot vaccination study in sub-Saharan Africa beginning in 2019. RTS,S/AS01 Phase III trials reported an efficacy of 28.3% (children 5–17 months) and 18.3% (infants 6–12 weeks), with substantial variability across study sites. We postulated that the relatively low efficacy of the RTS,S vaccine and variability across sites may be due to lack of T-cell epitopes in the vaccine antigen, and due to the HLA distribution of the vaccinated population, and/or due to ‘immune camouflage’, an immune escape mechanism. To examine these hypotheses, we used immunoinformatics tools to compare T helper epitopes contained in RTS,S vaccine antigens with Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein (CSP) variants isolated from infected individuals in Malawi. The prevalence of epitopes restricted by specific HLA-DRB1 alleles was inversely associated with prevalence of the HLA-DRB1 allele in the Malawi study population, suggesting immune escape. In addition, T-cell epitopes in the CSP of strains circulating in Malawi were more often restricted by low-frequency HLA-DRB1 alleles in the population. Furthermore, T-cell epitopes that were highly conserved across CSP variants in Malawi possessed TCR-facing residues that were highly conserved in the human proteome, potentially reducing T-cell help through tolerance. The CSP component of the RTS,S vaccine also exhibited a low degree of T-cell epitope relatedness to circulating variants. These results suggest that RTS,S vaccine efficacy may be impacted by low T-cell epitope content, reduced presentation of T-cell epitopes by prevalent HLA-DRB1, high potential for human-cross-reactivity, and limited conservation with the CSP of circulating malaria strains.

KEYWORDS: Malaria, RTS, S vaccine, T-cell epitopes, circumsporozoite protein (CSP), immune escape, immune camouflage, immunoinformatics, EpiMatrix, EpiCC, JanusMatrix

Introduction

Malaria is a disease that affects nearly half of the world’s population, with the majority of deaths occurring in children under the age of five.1 It is caused by the protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium, of which four species infect humans. Plasmodium falciparum is the species responsible for the most severe form of malaria in humans and the highest rate of childhood mortality.2 Naturally acquired immunity to malaria is slow to develop, is only moderately protective and repeated infections with malaria appear to be required to maintain immunity. Although protective immunogenic antigens have been difficult to identify, both antibody-mediated immunity and cell-mediated immunity to sporozoite stage proteins have been demonstrated to play a critical role in the host’s defense against malaria.3,4

Great effort has been dedicated to development of an effective vaccine that can aid in the elimination of malaria.4 A number of approaches have been taken to target the Plasmodium sporozoite stage, during which the parasite invades hepatocytes and expands prior to invading erythrocytes.5 Evidence for the feasibility of this approach comes from studies demonstrating that irradiated Plasmodium sporozoites confer protective immunity in humans during subsequent sporozoite challenges.6 Despite this success, challenges including the vaccine’s production and route of administration have impeded mass vaccination in endemic areas.4,7 Circumsporozoite protein (CSP), the major surface antigen of the sporozoite, is one of the most greatly studied malaria vaccine candidate antigens and has been recognized to elicit both antibodies and T-cell responses.8,9 The most advanced CSP vaccine, RTS,S, was approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to be used in African children.10 This vaccine contains the last 19 NANP repeats of the central repeat region of CSP including the C-terminal region, without the GPI anchor, from the P. falciparum strain 3D7, fused to Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). The fusion protein is co-formulated with free HBsAg, which spontaneously assembles into a virus-like-particle. The licensed vaccine is formulated with the GlaxoSmithKline AS01 adjuvant, which contains a mixture of liposomes, and adjuvants Monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) and QS21.11 Correlates of immunity associated with the RTS,S/AS01 vaccine have not been fully determined, although vaccination has been shown to induce high titers of IgG antibodies directed against the CSP’s central repeat region in protected individuals and moderate levels of CD4+Th1 responses specific to the CSP C-terminal region.12 The significance of these immune responses is supported by studies showing that CSP-specific CD4+ T-cells play an essential role in protection against Plasmodium infection through the induction of both humoral and cellular immune responses. CD4+ cells may act as direct effectors through the release of cytokines such as interleukin-2 (IL-2), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), or indirectly by assisting antibody production and circulation.13–15

The RTS,S malaria vaccine is expected to begin pilot testing in 2019 in Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi in a World Health Organization (WHO)-coordinated program to assess routine use safety and impact on mortality in children ages 5 to 17 months.16 In multiple clinical trials, the vaccine showed partial protection in adults, children, and infants, while also demonstrating significant variation in efficacy against clinical malaria (12.5–86%).17–25 Pivotal phase 3 trials conducted in seven sub-Saharan countries showed variable vaccine efficacy across 11 sites (40–77%).26 Variation has been attributed to factors including age differences, adjuvant formulation, presence of maternal antibodies, interference by co-administered vaccines, immune system maturity, and immunological history.26,27 We hypothesize that antigen presentation-related issues involving host, pathogen and vaccine genetic and immunological properties may have contributed to variability in RTS,S efficacy. In this study, using immunoinformatic methods, we profiled the human class II MHC epitope landscape of RTS,S and the corresponding sequences in circulating CSP in a Malawian cohort (published by Bailey et al. in 2012)28 to assess the potential for the vaccine to prime CD4+ T-cells that are needed to generate protective antibodies. We found low T-cell epitope content in the 73 amino acids representing the Th2 and Th3 regions of the CSP sequence of RTS,S, reduced association of T-cell epitopes present in this region with prevalent HLA-DRB1 in this malaria-endemic region, poor vaccine coverage (in terms of conserved epitopes) when comparing this region directly to the same sequence in circulating CSP variants, a high degree of cross-conservation between CSP T-cell epitopes (in the vaccine and circulating strains) and the human proteome, and limited vaccine epitope conservation with CSP epitopes in circulating malaria strains. Each of these observations on its own, and when taken altogether, may contribute to variable and suboptimal RTS,S efficacy.

Results

Imbalance in immunogenic potential of RTS,S vaccine components

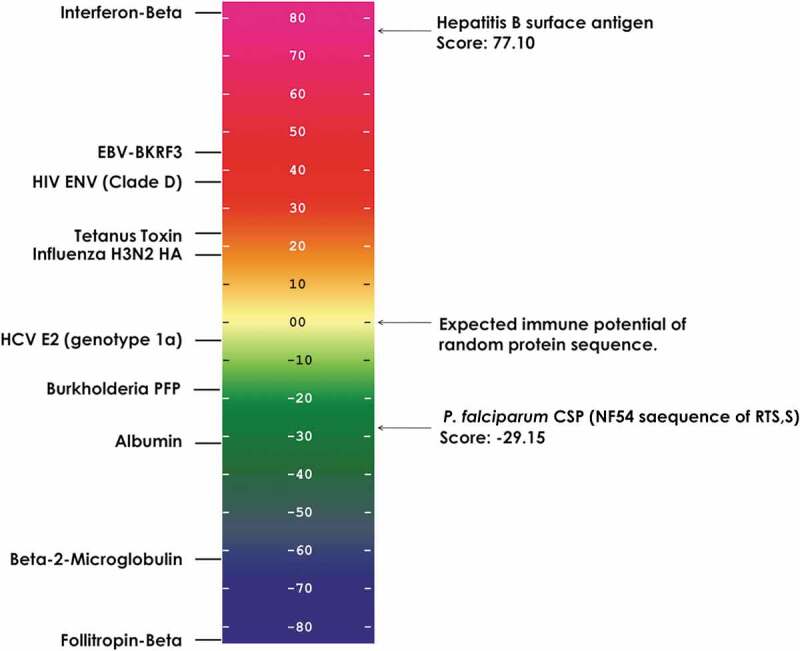

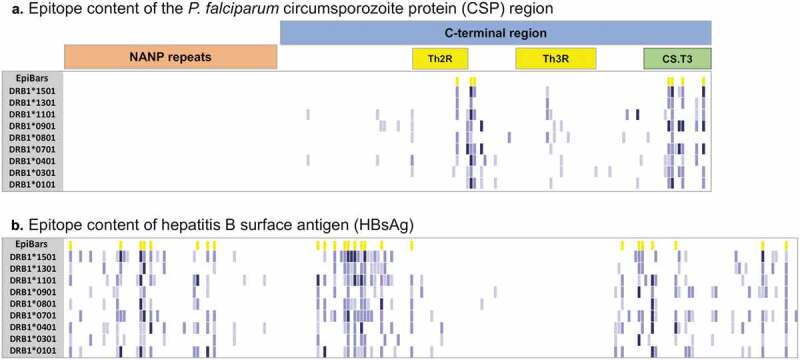

We have developed a method for evaluating the potential immunogenicity of vaccine antigens, which involves estimating HLA class II epitope content per unit length.29 We applied this method to assess the T-cell epitope-related immunogenicity contained in the vaccine sequence and the Hepatitis B surface protein. The overall scores of these sequences were derived by summing the number of sequences containing top 5% EpiMatrix Z-scores (indicating moderate to high probability of HLA binding) for 9 HLA-DRB1 supertype alleles and normalizing for protein length (number of 9-mer ‘hits’ per 1,000 9-mer assessments). In Figure 1, the normalized EpiMatrix scores of the RTS,S vaccine antigens (the truncated CSP and the HBV antigen, in terms of putative class II epitopes per unit length) are plotted on the EpiMatrix protein immunogenicity scale, where a random protein sequence is expected to have a score of zero. Proteins scoring +20 are considered to be potentially immunogenic.29 By comparison to other well-known vaccine antigens, the CSP sequence from amino acid 207 to amino acid 395 of P. falciparum strain NF54 in the RTS,S vaccine, registered a low EpiMatrix Score of −29.15, reflecting the low T-cell epitope density of this sequence. In contrast, the Hepatitis B surface protein used in the vaccine registered an EpiMatrix Score of +77.10, indicating that this antigen has a higher density of predicted class II epitopes overall than CSP (Figure 1). At a higher level of detail, Class II epitope predictions are shown in Figure 2, where the core 9-mers of epitopes are shaded degrees of blue based on their predicted binding likelihood. Notably, the NANP repeat region of CSP, which is known to be a major antibody target,12 has no predicted class II epitope content (Figure 2(a)). High T-cell epitope content is observed in the Th2R and Th3R regions, which are known to be highly variable, and some epitope content is also observed in the conserved CD4+ T-cell epitope region (CS.T3). These observations are confirmed in prior studies that demonstrated CD4+ T-cell activity against the domains present in the C-terminal region of the CSP.30 Thus, as has been confirmed by many other laboratories, malaria-specific T-cell immunogenicity potential in RTS,S is focused in the C-terminal region of the CSP component. In contrast, the Hepatitis B surface antigen is rich in epitope content spanning all common HLA class II alleles (Figure 2(b)). Considering the fusion protein contained in RTS,S, which is made up of truncated CSP linked to HBsAg, HBsAg T helper epitopes outnumber CSP T helper epitopes in the fusion protein, 2.5 to 1 (181 epitopes in HBsAg to 73 in the truncated CSP). Given a stoichiometry of non-linked HBsAg to fusion protein of 3:1,31 the proportion of HBsAg T cell epitopes to CSP T cell epitopes in the vaccine is 9.9:1.

Figure 1.

Relative CD4+ T-cell immunogenicity potential of RTS,S vaccine components. This scale provides a normalized assessment of the potential immunogenicity of the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein (CSP) region (189 aa) and Hepatitis B surface antigen (226 aa) included in the RTS,S vaccine based on the HLA class II epitope content. EpiMatrix scores are normalized and plotted on a standardized scale. The average score of a random protein sequence is expected to be zero. EpiMatrix protein scores above zero have a higher potential for immunogenicity whereas scores below zero have a lower potential for immunogenicity. On the left side of the scale are well known antigens that are included in other vaccines and other reference proteins, for comparison. The P. falciparum CSP protein sequence scored low at −29.15. In contrast, Hepatitis B surface antigen scored 77.10, near the top of the immunogenicity scale.

Figure 2.

MHC class II T-cell epitope content of the RTS,S vaccine components. (a) P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein (CSP) region (UniProt Q7K740) and (b) Hepatitis B surface antigen (UniProt Q4KZP3) were parsed into overlapping 9-mer frames (columns) assessed for binding against a panel of nine class II HLA-DRB1 alleles (rows). Predicted binding potential to a given allele was determined and expressed as a Z-score; 9-mers with Z-scores above 1.28 represent the top 10% of predicted binders and are shown in light blue, 9-mers with Z-scores above 1.64 represent the top 5% shown in medium blue and peptides with Z-scores above 2.32 are in the top 1% shown in dark blue. Frames with four or more hits (first row) are highlighted in yellow (EpiBars). Predicted putative class II T-cell epitopes for the CSP region are clustered in the highly variable CD4+ T-cell region (Th2R). In contrast, the immunodominant B-cell epitope NANP repeat region does not contain any predicted HLA-DR binding, indicated by the visibly clear space in the region analysis.

Inverse relationship between TH2R/TH3R T-cell immunogenicity potential and HLA allele frequency in Malawi

The immunogenicity potential of the malaria-specific component of the vaccine was further characterized by comparing its epitopes with epitopes found in the 73 amino acids representing the Th2 and Th3 regions of CSP that were sequenced from individuals living in a malaria endemic area (Malawi, Bailey et al. 2012). We compared the Th2 and Th3 regions of the vaccine to the amino acid sequences of 57 unique P. falciparum CSP variants obtained from Bailey et al.28 Overall, the Malawian CSP variant sequences displayed a broad range of EpiMatrix HLA DR scores, from −47.21 to 1.12. Of all the CSP variants, only 33.3% (19 variants) scored above 0, and none of these surpassed the threshold of 20 considered to reflect the minimal score for immunogenic sequences of this length. The remaining 66.7% (38 variants) exhibited even lower immunogenicity scores. The vaccine strain (pUID8) sequence scored −8.26 on the immunogenicity scale.

We found an inverse correlation between HLA DR allele prevalence in the population and overall scores for the CSP sequences found in the same population. Allele-specific EpiMatrix scores were defined for the vaccine and for the CSP of circulating strains, and compared to the distribution of HLA-DRB1 alleles reported for this study population.28 Across the CSP variant sequences, putative epitopes within the top 5% of binders were more often restricted by HLA DRB1*0801, DRB1*0401, and DRB1* 0701, all of which are present in less than 20% of the study population (reflected by the red shaded areas in Table 1). Interestingly, T-cell epitopes were less prevalent in the CSP sequences for the HLA DRB1*1501 and DRB1*0301 alleles, which are each present in more than 25% of the study population (reflected by the blue shaded columns in the epitope prevalence heat map shown in Table 1).

Table 1.

Heat map representing the HLA-DR restricted immunological potential of the 57 CSP Malawi variants on an allele-by-allele level.

|

For each Malawian CSP variant, epitope mapping (for the entire CSP variant sequence) was performed separately for each of the nine supertype HLA-DR alleles. The overall protein score for each allele is color-coded (blue for low epitope content, red for high epitope content). The prevalence of epitope hits per allele is clear in the heat map Few sequences had epitopes that were restricted by HLA DRB1*1301, DRB1*1501, and DRB1*0301, which are common HLA alleles in the Malawian population. More EpiMatrix hits were identified HLA DRB1*0801 and DRB1*0401, which rare HLA alleles, not often found in the Malawi population.

CSP T cell epitopes were also predicted to bind with low affinity to prevalent HLA DR alleles. Z-scores are roughly correlated with T-cell epitope affinity for HLA binding. On an allele-by-allele basis, the highest average Z-scores were associated with DRB1*0401 and DRB1*0801, which were present in only 5.1% and 8.5% of the study population, respectively. Conversely, the lowest average Z-scores for the CSP Th2R-Th3R variants were associated with DRB1*1301, DRB1*1501, and DRB1*0301, found in 24.8%, 30.8% and 25.6% of the study population, respectively. The HBsAg sequence had high average Z-scores associated with DRB1*0401, DRB1*1101, DRB1*0701, DRB1*0101, DRB1*1501, DRB1*0901, and DRB1*1301, a pattern that was not associated with either common or rare alleles found within the study population. The lowest average Z-scores of the HBsAg sequence were associated with DRB1*0801 and DRB1*0301 (one low and one high prevalence allele), thus immune escape does not seem to occur in the case of HBsAg. The genetically fused CSP and HBsAg sequence present in the RTS,S vaccine displayed an allele association similar to that of the HBsAg alone (Table 2).

Table 2.

HLA-DRB1 restricted epitope content of the 57 CSP Malawi variants at a population level.

|

*The five sets are sorted based on the average EpiMatrix Z-scores of the circulating CSP Malawian strains from the highest to the lowest scores. Higher Z-scores are shown as red shaded areas and lower Z-scores are shown as blue shaded areas.

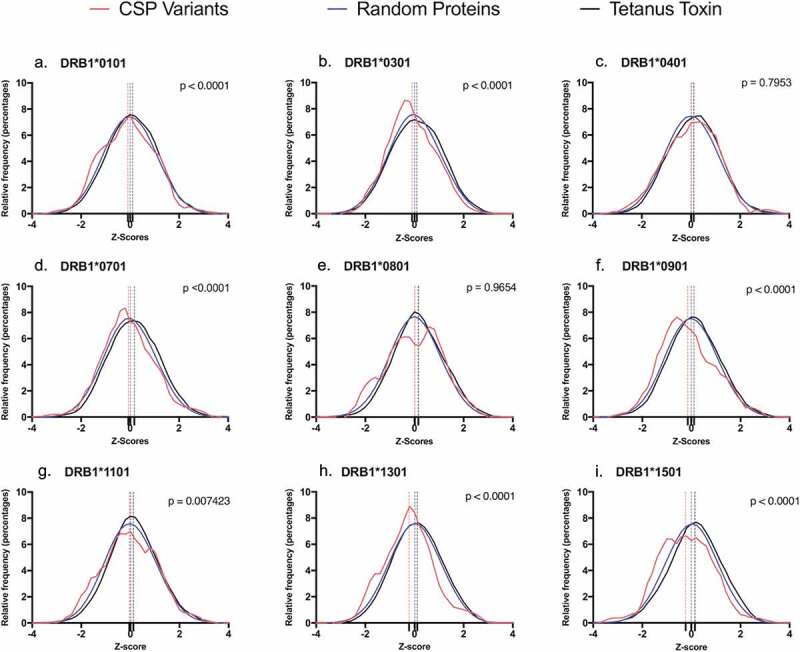

To determine whether the epitope content across the 57 CSP variant sequences was significantly different from random expectation, we performed an unpaired t-test to compare CSP variant epitope content per allele, to the scores for a set of 1,000 random peptides of equal length. As expected, the Z-scores for the set of random proteins passed the D’Agostino-Pearson normality test with a zero mean and a standard deviation of one. Based on their Z-scores, the total putative T helper epitope content restricted by the high prevalence HLA allele families DRB1*0101, DRB1*0301, DRB1*0701, DRB1*0901, DRB1*1301, and DRB1*1501 was significantly skewed below zero for the 57 CSP Th2R/Th3R variants when compared to the scores of the set of random peptides of equal length (p < 0.0001). This was also true for epitopes restricted by DRB1*1101 (p = 0.0074). Additionally, the mean values of the Z-scores of these alleles demonstrated a significant shift to the left (lower average Z-scores) as compared to observed distribution of the random protein sequences of the same length. Scores for the remaining (low prevalence) alleles (DRB1*0401 and DRB1*0801) were not significantly different from random (p = 0.7953 and 0.9654, respectively). In contrast, for tetanus toxin (used here to provide an example of a strong antigen), the mean value of the Z-scores for all the HLA DRB1 alleles exhibited a shift to the right when compared to the set of random peptides, indicating higher average Z-scores, which is expected for a highly immunogenic antigen (Figure 3). These observations suggest that T-cell epitopes restricted by common HLA-DRB1 alleles in malaria-endemic populations may be less common in the CSP variant sequences than epitopes restricted by rare alleles. This finding is unique to CSP and is not observed for tetanus toxin nor for a set of random peptides of equal length.

Figure 3.

T-cell epitope score distribution of the 57 Malawian CSP variants per HLA-DR1 allele. Each graph represents the relative frequency distribution of the EpiMatrix scores of the parsed 9-mers per HLA-DR1 allele for three data sets: The set of CSP variants (red), a set of random proteins (blue) and tetanus toxin (black). Difference in the epitope content of the CSP variants and the set of random proteins was established by performing a t-test. Seven HLA-DRB1 alleles showed significant difference from random proteins (p < 0.05), exhibiting a shift to the left from the normally distributed set of proteins (a,b,d,f,g,h,i). The remaining two alleles (c,e) show no significant difference (p > 0.05).

Direct relationship between frequency of TH2R/TH3R TCR-face patterns and immunosuppressive potential

To characterize the TCR-face conservation of the vaccine and the 57 Malawian CSP strain variants, we performed two types of JanusMatrix analyses. First, the predicted T-cell epitopes among the 57 CSP variants and the vaccine (represented by pUID8 in the dataset) were evaluated for conservation at the TCR face with HLA-DRB1-restricted epitopes contained in the entire dataset of 57 CSP sequence variants (we use the word “JanusMalaria” to describe this analysis). Second, the TCR-facing residues of CSP variant epitopes were screened against HLA-DRB1-restricted T-cell epitopes in the human proteome (“JanusHuman”) as previously described.32

Two types of homology scores were calculated (Table 3). The JanusMalaria homology score represents the degree of conservation of a given sequence to epitopes contained in circulating CSP C-terminal regions of P. falciparum strains in Malawi. Accordingly, the hypothetical maximum possible JanusMalaria score of a given peptide would be 57 (conserved with all the strains), if every EpiMatrix predicted epitope contained in the test sequence has a TCR-matching counterpart in every variant in the dataset. None of the CSP variants were highly conserved based on their JanusMalaria scores: the range across all variants was 6.42 to 18.92, confirming previous reports of the high degree of variability of Th2R/Th3R epitopes in circulating malaria strains.33

Table 3.

JanusMatrix homology analysis.

|

aAverage depth of coverage in the human genome for each EpiMatrix hit of a given CSP variant sequence. JanusHuman scores above two suggest elevated potential for tolerance while scores below 2 suggest elevated immunogenic potential.

bAverage depth of coverage in the set of CSP variants for each EpiMatrix hit of a given CSP variant. JanusMalaria score represents the degree of conservation of a CSP variant to epitopes contained in circulating CSP C-terminal regions of P. falciparum strains in Malawi.

Table is colored by column; high values are shown in red and low values in blue.

T-cell epitopes contained in the CSP Th2R/Th3R region were also evaluated for conservation with the human proteome. In previous studies, we found that epitopes that have high homology with the human proteome may be tolerated or actively regulatory (Treg) epitopes.34,35 The JanusHuman homology score quantifies the degree to which putative T-cell epitopes contained in the CSP variant sequences are cross-conserved with sequences in the human proteome. Scores >2 indicate epitopes that are conserved with the human proteome, and potentially tolerogenic. The JanusHuman scores of the 57 CSP variant strains ranged from 0.64 to 3.92. Of the CSP variants, only 25% (14 variants) had a JanusHuman score below the threshold value of 2 (reflecting elevated potential for immunogenicity). The remaining 75% (43 variants) scored 2 and above (reflecting elevated potential for tolerance due to higher conservation with the human proteome). We note that the vaccine strain registered a JanusHuman score of exactly two.

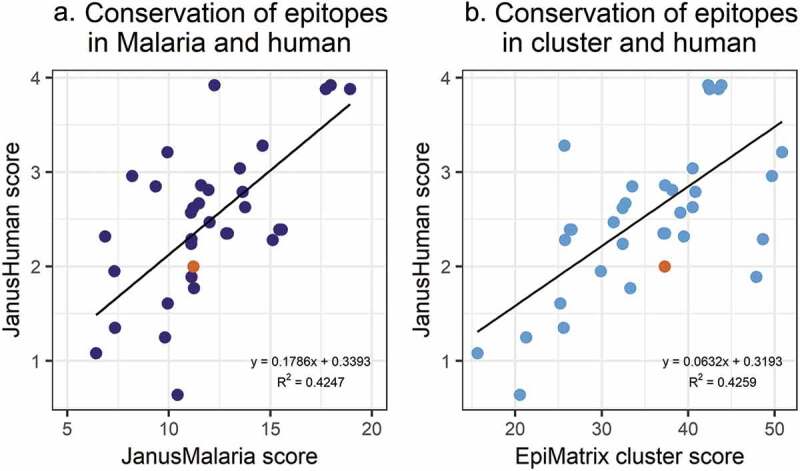

To evaluate the relationship between the level of cross-reactivity with human and the degree of strain conservation within the population, we evaluated the relationship between JanusHuman scores and the JanusMalaria scores. JanusHuman scores of each variant were positively correlated with both their EpiMatrix Cluster scores (R = 0.65) and their JanusMalaria scores (R = 0.65; Figure 4). The more conserved the T-cell epitopes are across the Malawian CSP variant strains, the more their TCR-facing residues were cross-conserved with the human proteome. Thus, epitopes that are more conserved across circulating malaria strains in Malawi were more human-like. Higher scoring T-cell epitope clusters in the CSP sequences are also more human-like.

Figure 4.

Cross-conservation of the 57 Malawi CSP variants with the human genome. JanusMatrix analysis of the predominant T-cell epitope clusters in each CSP Malawian variant identified T-cell epitopes that are more likely to activate regulatory T-cells (cross-conservation with the human genome) and T-cell epitopes that are conserved in the Malawian parasite population (cross-conservation with the CSP Malawi variants). (a) Each point represents JanusMatrix human scores (JanusMatrix conservation in human genome) and JanusMalaria scores (JanusMatrix conservation in Malawi malaria strains) of a Malawian CSP variant. A correlation is established: the more conserved the T-cell epitopes are across the Malawian CSP variant strains, the more their TCR-facing residues are cross-conserved with the human genome. (b) Each point represents JanusMatrix human score and EpiMatrix cluster scores of a Malawian CSP variant. A correlation is also observed between these value sets: higher EpiMatrix cluster scores are correlated with higher JanusMatrix human scores.

Overall T-cell epitope content of RTS,S TH2R/TH3R relative to Malawian CSP is limited

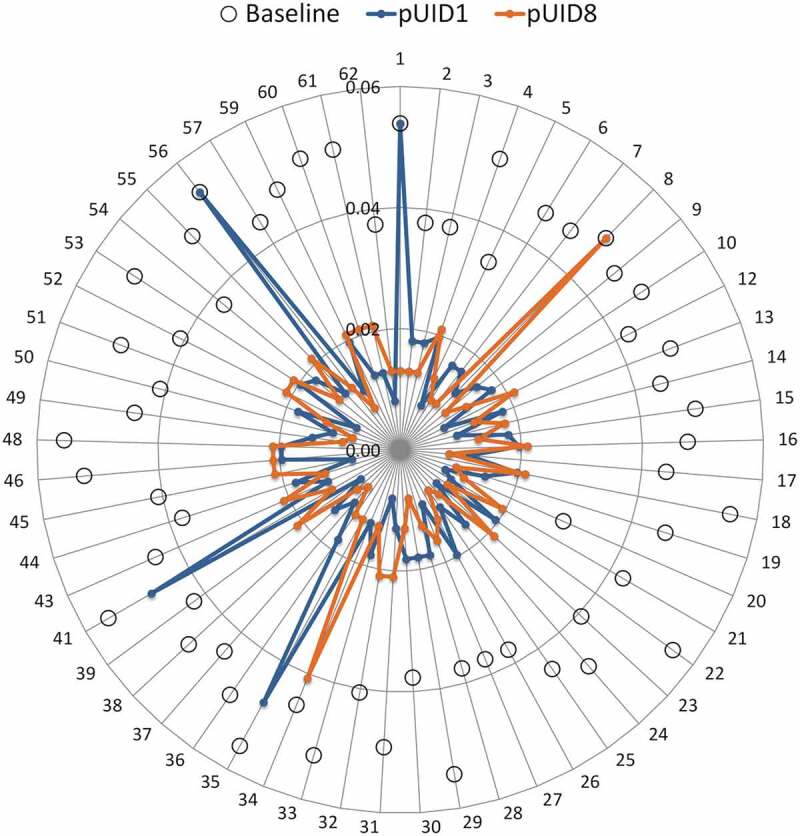

The vaccine strain (pUID8; 11.21, highlighted in orange in Figure 4) had a low JanusMalaria homology score, indicating that the TCR-facing sequences of epitopes contained in the vaccine were not highly conserved with their counterparts in other Malawian CSP sequences. To quantitate the relatedness of the T-cell epitope content between the CSP sequence of the vaccine and the circulating strains, we performed an epitope content comparison using the EpiCC algorithm.36 EpiCC scores were calculated for pairwise comparisons of T helper epitopes contained in the RTS,S vaccine with the homologous epitope found in circulating strains (Table 4). The greater the similarity of the T-cell epitope content between the reference and query strains, the greater the EpiCC score. The maximum EpiCC score for a sequence (baseline EpiCC score) reflects its overall T-cell epitope content and is defined by comparing the sequence against itself. The baseline EpiCC score of the vaccine was 0.0487. Nineteen of the 57 CSP variants had greater T-cell epitope content (baseline EpiCC scores) than the vaccine.

Table 4.

T-cell epitope content comparison (EpiCC) results.

|

aOverall T cell epitope content of each variant. CSP variants with baseline EpiCC scores (comparison to self) greater than that of the vaccine (0.0487) are shown in bold font.

bThe greater the similarity of the T-cell epitope content between the vaccine and query strains, the greater the EpiCC score.

cEpiCC score/variant baseline EpiCC score*100. Prevalent CSP variants (found 10 or more times) with the highest % of the variant baseline EpiCC score are shown in bold font.

dCSP variants with average EpiCC scores greater than that of the vaccine (0.0159) are shown in bold font.

Table is colored by column; high values are shown in red and low values in blue.

The Bailey et al. 201228 publication provided details on the prevalence of 57 unique circulating CSP variants based on the Th2 and Th3 region. Only three of the most prevalent CSP variants (pUID4, pUID12 and pUID8), including the vaccine strain, had EpiCC scores that were more than 40% of the variant’s baseline score (Table 4 and Figure 5). In addition, only one variant (pUID34), which was found in only one sample, had an EpiCC score that represented more than 80% of the variant’s baseline EpiCC score. Overall, the vaccine covered only 34.1% of the T-cell epitope content found in CSP variants. This result showed that the T-cell epitope content shared between the vaccine and the Malawian CSP variants is very limited. The EpiCC score has been used to define a threshold for vaccine efficacy in influenza studies;36 a threshold for malaria vaccines has not been defined.

Figure 5.

EpiCC score of the RTS,S malaria CSP strain sequence against the 57 circulating Malawian CSP variants. EpiCC assesses the relatedness of T-cell epitopes contained in the CSP sequence of the RTS,S vaccine and those in the Malawi CSP variant strains based on a comparison of their epitope sequences and EpiMatrix binding scores. The higher the EpiCC score, the higher the T-cell epitope content, the more related the epitopes of two strains are and more potential of cross-protection. On the radar plot, each axis represents one of the CSP malaria variants circulating in Malawi (number 1 = pUID1, 2 = pUID2, and so on). EpiCC scores of the RTS,S vaccine strain (pUID8) compared to the CSP Malawian variants are shown in orange. EpiCC scores of an alternative candidate strain (pUID1) compared to the CSP Malawian variants are shown in blue. pUID1 shares, on average, slightly more T cell epitope content with the circulating CSP variants compared to the vaccine’s pUID8. Baseline EpiCC scores of each variant strain (comparison to self) are shown as open circles.

The average EpiCC score of the vaccine compared to all the variants was 0.0159. Thirty-four CSP variants (out of 57) had average EpiCC scores higher than that of the vaccine, i.e. there were 34 variants that, on average, share more T-cell epitope content with Malawian variants than the vaccine strain.

Based on these results, the vaccine strain, due to T-cell epitope content, may be a less than optimal selection for a vaccine candidate for use in Malawi. Given the set of CSP sequences circulating in Lilongwe, Malawi at the time of sampling, the best vaccine strain to pick should have a high intrinsic EpiCC score (high T helper epitope content) and a low JanusHuman score (low potential for generating tolerance). For example, pUID1 has a slightly higher average EpiCC score (0.017) than the vaccine’s pUID8 (0.016), and also has a JanusHuman Homology Score below 2 (1.91), while the vaccine’s pUID8 strain Janus score is 2, and pUID1 was the second most prevalent variant in Malawi (found 22 times). We identified strains that share on average more T-cell epitopes with the CSP variants, but their JanusHuman Homology scores were above 2 (e.g. pUID18, pUID46, pUID48, and pUID53). Moreover, the average EpiCC scores of the CSP variants directly correlated with JanusHuman Homology scores (R = 0.79; p < 0.01). Hence, CSP variants that share more T-cell epitope content have epitopes that are more cross-conserved with human proteins and more likely to be tolerated or actively regulatory. This result is consistent with the correlation found between JanusHuman and JanusMalaria homology scores. Finally, CSP variants with higher baseline epitope content also had lower JanusMalaria scores (R = −0.33; p = 0.01), meaning that T cell immunogenicity potential of circulating CSP and their epitope conservation are inversely related.

Discussion

To prevent liver stage malaria infection, the RTS,S malaria vaccine should exhibit a number of desired features that involve CD4+ T-cell induction. First it should generate strong antibody responses against sporozoites.37–40 CD4+ T-cells drive antibody maturation and improve antibody affinity to support protective antibody responses.41 Thus, the CD4+ T-cell response induced by RTS,S and by CSP in the context of natural infection requires further study. In addition, CD8+ T-cells require CD4+ T-cell help in immunization to generate a strong primary response to produce durable memory that is needed for effective recall upon secondary challenge.42 Since CD8+ T-cell responses to sporozoite proteins are also critical for protection against liver stage infection38 and CD8+ T-cell responses induced by RTS,S may contribute to infection control should parasites evade antibody recognition, modulation of CD4+ T cell help may reduce CD8+ T cell efficacy. Finally, the ideal CSP vaccine should be effective across a broad spectrum of P. falciparum strains and across the HLA diverse human population.

Despite initial optimism, the RTS,S vaccine has been shown to have significant heterogeneity in the vaccine’s efficacy among participants and across the clinical trial sites. Factors contributing to the moderate efficacy of the RTS,S vaccine include the participant’s age, immune history, co-administration with other vaccines, dosing and the adjuvant system.26,27 However, there are additional factors that can impact immune responses. One factor is the restriction of the CD4+ T-cell epitope content which may dampen immune response. Although it is well known that the T-cell sequences of CSP are variable, we also found that the concentration of T cell epitope content of the CSP sequence found in circulating strains of malaria in Malawi was variable, with the majority of the variants, including the 3D7 strain used in the RTS,S vaccine, scoring low for overall T-cell epitope content. Also, the impact of HLA-DR restriction with respect to HLA prevalence in malaria endemic regions is worth noting. We found that the HLA-DR restriction of T-cell epitopes contained in the RTS,S vaccine (and many other CSP sequences found in naturally circulating variants) was inversely correlated with the prevalence of those epitopes of HLA-DR alleles in Malawi. Furthermore, circulating P. falciparum strains in Malawi also possess putative T-cell epitopes in Th2/Th3 that are restricted by HLA-DRB1 alleles that are rare in the Malawi population. This suggests that immune escape by P. falciparum may be occurring at the population level, and that the parasite has adapted to the local human population and evolved to escape HLA-DR-restricted immune responses, a mechanism that is exploited by several other pathogens.43–45

Our analysis therefore support studies that implied that T-cell epitope escape may be driven by immune pressure46–49 in endemic populations. The dearth of predicted HLA-DRB1 restricted T-cell epitopes we find in the CSP-derived sequence of RTS,S, together with the poor match to circulating strains, may not support the T-cell help from memory T cells during vaccination that may be needed to reduce disease burden. On the other hand, substantial T-cell epitope content in the HBV surface antigen may counterbalance to provide the T-cell help that may be required for induction of anti-CSP antibodies.

Evading the immune system is key to the survival of P. falciparum. It is not surprising therefore that P. falciparum strains in circulation also utilize immune camouflage, an immune evasion strategy that our group first described in 2013.32 Immune camouflage is exhibited by pathogens that possess T-cell epitopes that have a high degree of cross-conservation with the human proteome at TCR-facing residues. Presentation of such epitopes on HLA may induce regulatory T-cells that in turn suppress productive effector CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses needed to generate sustained levels of protective antibodies and block liver stage infection. In this study, using the JanusMatrix algorithm, we found that HLA-DRB1 restricted T-cell epitopes that are highly conserved across Malawian CSP variants are likely to cross-react with epitopes derived from the human proteome. Several publications from our group have shown a relationship between poorly performing vaccines and the presence of such putative Treg inducing epitopes in HCV,50 HIV,50 and influenza A.35 While it is clear that immune camouflage in circulating strains may have no relevance in the context of a naive individual from a non-endemic region who is vaccinated with RTS,S, the presence of malaria CS-antigen-specific Tregs that have been induced by prior exposure may dampen immune response to RTS,S in previously exposed individuals. Taken together, the overall reduction in T-cell epitope content and the presence of residual epitopes that are cross-conserved with self and potentially tolerated may explain the low levels of CSP specific CD4+ T-cells observed in RTS,S clinical trials, and that vaccine’s moderate efficacy.

Our analysis of circulating CSP sequences using the EpiCC tool also suggest that careful selection of vaccine strains might lead to improved efficacy, a vaccine strain with good T-cell content and low Janus score was identified from the circulating CSP strains in Malawi that would be a better fit for the parasite population in Malawi than the strain present in the RTS,S vaccine. An alternative would be to immune engineer a more immunogenic and representative sequence.

An important caveat to our data interpretation is that the degree of CSP sequence diversity may differ from one population to another. Thus, the findings for the P. falciparum population in Malawi may not represent findings for parasite populations in other endemic areas. We have not examined the contributions of CD8 T-cells in this study as the primary focus was on T-cell help (and regulatory T-cells). The findings of this study would be further supported by ex vivo immunological validation using HLA-typed samples from trial participants and sites. Based on data presented here, when designing a new Malaria vaccine, it may be useful to include a comprehensive analysis of all vaccine components such as: 1) CSP sequence isolates and HLA information from other trial sites, 2) correlation of participant HLA and in silico predictions with vaccine efficacy and titers induced to CSP/HBsAg, 3) evaluation of vaccine potential to induce regulatory vs. effector T-cell responses and to suppress B cell responses based on CSP epitope humanness.

In conclusion, the deployment of the RTS,S malaria vaccine may be impacted by challenges of low immunogenic content, poor coverage of pathogenic variants, and the potential for human-cross-reactivity, all of which may limit the development of an effective immune response. In silico immunoinformatics tools offer powerful mechanisms to select and refine the next generation of malaria vaccine candidate antigens. They may also be applied using the approach described here to understand clinical trial outcomes for other vaccines.

Methods

Sequences

The complete amino acid sequence of the RTS,S vaccine was found in the US20050002958A1 patent (Cohen et al. 2005).51 Beginning from the N-terminus of the CSP-HBsAg fusion, the first 189 amino acids are derived from CSP (from the 3D7 strain of P. falciparum), followed by the fusion protein linker sequence (GPVTN), and finally 226 amino acids derived from Hepatitis B virus pre-S2 protein (adw serotype).

A set of 57 unique CSP variant sequences, each 73 amino acids in length, identified within the falciparum parasite population in Lilongwe, Malawi using massively parallel pyrosequencing on the Plasmodium falciparum CSP Th2R and Th3R T-cell epitope regions, have been used to represent the CSP variant frequency of the Th2R region epitopes within the Malawi population. Each variant was assigned a unique population identifier (pUID) (GenBank JN634586-JN634642).28

For purposes of comparison with Malawian CSP variants, we generated a set of 1,000 random proteins each 73 amino acids long using the SWISSPROT random protein generator at natural amino acid frequencies referenced in SWISSPROT. Also for comparison to a well characterized vaccine antigen, we obtained the sequence of tetanus toxin from Clostridium tetani strain E88, (UniProt P04958).

MHC binding potential analysis

The EpiMatrix T-cell epitope mapping algorithm was used to identify putative class I and class II HLA binding epitopes within a protein sequence.29 Because 9 amino acids are the minimal length an HLA binding groove accepts, input sequences were parsed into overlapping 9-mer frames in which each frame overlaps the last by 8 amino acids. Each 9-mer was assessed for its binding potential against a panel of nine class II HLA-DRB1 alleles, DRB1*0101, DRB1*0301, DRB1*0401, DRB1*0701, DRB1*0801, DRB1*0901, DRB1*1101, DRB1*1301, and DRB1*1501, which are “supertype” alleles representative of HLA class II of over 95% of the global population.52 Each EpiMatrix peptide-to-allele assessment was normalized based on the frequency of T-cell epitopes derived from a set of random protein sequences to arrive at a Z-score. EpiMatrix Z-scores above 1.64 were considered hits and represent the top 5% of predicted binders. EpiMatrix Z-scores above 2.32 represent the top 1%, even more likely to bind HLA alleles. An EpiMatrix Protein Score was calculated to determine the overall epitope content of an input sequence with respect to random expectation, where positive scores indicate an excess of putative epitopes and negative scores indicate a lack of putative epitopes relative to a random sequence of equivalent length. Regions of elevated putative epitope density, called T-cell epitope “clusters” were identified using ClustiMer, an algorithm that identifies sequences that have a promiscuous HLA Class II binding profile.29 The RTS,S vaccine sequence, the set of 57 CSP variant sequences, the 1000 random protein reference set and the tetanus toxin sequence were analyzed using EpiMatrix and ClustiMer, and compared for T-cell epitope content and/or for cross-conservation as described below.

T-cell epitope content by HLA-DRB1 allele

57 Malawian Th2/Th3 CSP variants, each 73 amino acids in length, generated a total of 3,705 9-mer frames. The Z-scores for each 9-mer within each HLA-DRB1 allele were used to create a histogram to evaluate the frequency distribution and generate a mean for the CSP set per HLA-DRB1 allele. Analysis was repeated for the set of 1,000 random protein sequences of the same length, which generated 65,000 9-mer frames. Finally, HLA-specific analysis was performed for the Tetanus Toxin protein, 1,315 amino acids in lengths and comprising 1,307 9-mer frames. Smoothed histograms were generated to visualize the mean difference between the datasets, per HLA-DRB1 allele.

Cross-conservation analysis

The JanusMatrix algorithm was used to predict potential cross-reactivity on the basis of shared T-cell-receptor-interacting residues of putative T-cell epitopes found among the set of 57 unique Th2/Th3 CSP variant sequences and within the human proteome.32 JanusMatrix parsed the amino acid sequences of EpiMatrix clusters into 9-mer frames and then designated TCR-facing residues (positions 2,3,5,7, and 8) and MHC-binding amino acid residues (positions 1, 4, 6, and 9). Next, JanusMatrix searched specified databases (CSP variants and UniProt reviewed human proteome) for 9-mers with identical TCR-facing residues compared to the input sequence, provided they are predicted to bind to the same HLA allele. Two peptides related in such a way were considered “cross-conserved”. A JanusMatrix Homology Score was calculated, representing the average depth of coverage in the search database for each EpiMatrix hit of the input sequence. Based on a comparison with published epitopes in the immune epitope database (IEDB, http://www.iedb.org/), peptides with higher JanusMatrix Human Homology Scores (more human-like) are more likely to induce the release of the cytokine IL-10 than IL-4. These two cytokines are more often associated with a regulatory T-cell response and an effector T-cell response, respectively. Conversely, peptides with lower JanusMatrix Human Homology Scores (less human-like) are more likely to induce the release of the effector cytokine IL-4.50,53 Accounting for the fact that a certain degree of cross conservation is expected for any putative ligand, a JanusMatrix Homology Score greater than two calculated for human proteome was used as a threshold for human cross-conservation. The threshold represents the top 5% of scores for human sequences based on an analysis of large dataset of putative ligands composed of random amino acids. Scores from JanusMatrix analysis using the human proteome database are referred to as JanusHuman and those from analysis of the variant CSP sequence database as JanusMalaria. In this study, JanusMatrix was used to analyze T-cell epitope clusters in each Malawian variant CSP sequence to evaluate the potential of cross-reactivity with two sequence databases – the human proteome (JanusHuman) and the set of 57 Malawian variant CSP sequences (JanusMalaria).

T-cell epitope content comparison (EpiCC)

The epitope content comparison algorithm (EpiCC) was applied to determine the relatedness of the putative class II T-cell epitopes shared between the vaccine and each CSP variant.36 EpiCC evaluates the relatedness of T-cell epitopes contained in the protein sequence of a vaccine and those found in the protein sequence of a variant strain of the same organism, by comparing their epitope sequences and EpiMatrix binding scores. The maximum EpiCC score for a vaccine was defined by comparing the T-cell epitopes contained in the protein sequence to itself (baseline EpiCC score). This score represents the epitope density of the sequence and the binding probabilities (EpiMatrix Z-scores) of its epitopes. When comparing a vaccine to a variant, the EpiCC score would be equal to or lower than the baseline scores of the vaccine and the variant. A vaccine was considered to share more T-cell epitope content with a variant when the EpiCC score was closer to the variant’s baseline score.

To determine T-cell epitope relatedness, the baseline EpiCC score of each variant Malawian sequence and the scores relating variant sequences and the vaccine strain (pUID8) were calculated. Each CSP variant was also compared to all other CSP variants and an average EpiCC score was calculated for each of these comparisons to determine whether another variant strain might be a better candidate for use as a vaccine in Malawi. Variants with higher average EpiCC scores in this comparison would have more shared T-cell epitope content with other circulating CSP variants. The relationship between the baseline and average EpiCC scores of the vaccine and CSP variants and Janus scores were calculated to determine whether the prevalence of a specific strain correlated with the T-cell epitope content of the strain.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 6 and Microsoft Excel version 15.32. Unpaired t-test was used to compare the mean values of the EpiMatrix Z-scores per HLA allele for each 9-mer in the Malawi CSP variants dataset and the set of random proteins. Differences were considered significant for p < 0.05. Also, The D’Agostino-Pearson normality test was used to check for normality of distribution within the datasets. In addition, Pearson correlation analyses were performed to establish the relationship between the JanusHuman scores and the JanusMalaria scores as well as the relationship between JanusHuman scores and ClustiMer scores. Pearson correlation was also applied to evaluate the relationship between EpiCC scores and Janus homology scores.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

ADG and WDM are senior officers and majority shareholders at EpiVax, Inc., a privately owned immunoinformatics and vaccine design company located in Providence, RI, USA. LM, FET and AHG are employees at EpiVax, in which LM holds stock options. ADG, WDM, LM, FET and AHG acknowledge that there is a potential conflict of interest related to their relationship with EpiVax and attest that the work contained in this research report is free of any bias that might be associated with the commercial goals of the company.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation . WHO | malaria. WHO. 2017. [accessed 2017 June 23]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/#.WU1EUDkCfpE.mendeley

- 2.Schumacher R-F, Spinelli E.. Malaria in children. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2012;4(1):e2012073. doi: 10.4084/mjhid.2012.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doolan DL, Dobaño C, Baird JK.. Acquired immunity to malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(1):13–36. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00025-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thera MA, Plowe CV. Vaccines for malaria: how close are we? Annu Rev Med. 2012;63(3):345–357. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-022411-192402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwenk RJ, Richie TL. Protective immunity to pre-erythrocytic stage malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27(7):306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman SL, Goh LML, Luke TC, Schneider I, Le TP, Doolan DL, Sacci J, de la Vega P, Dowler M, Paul C, et al. Protection of humans against malaria by immunization with radiation-attenuated plasmodium falciparum sporozoites. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(8):1155–1164. doi: 10.1086/339409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill AVS. Vaccines against malaria. Philos Trans R Soc Lond, B, Biol Sci. 2011;366(1579):2806–2814. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zavala F, Tam JP, Barr PJ, Romero PJ, Ley V, Nussenzweig RS, Nussenzweig V. Synthetic peptide vaccine confers protection against murine malaria. J Exp Med. 1987;166(5):1591–1596. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.5.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romero P, Maryanski JL, Corradin G, Nussenzweig RS, Nussenzweig V, Zavala F. Cloned cytotoxic T cells recognize an epitope in the circumsporozoite protein and protect against malaria. Nature. 1989;341(6240):323–326. doi: 10.1038/341323a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Medicines Agency . First malaria vaccine receives positive scientific opinion from EMA. European Medicines Agency; 2015. Jul 24 [accessed 2017 Dec 10]. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Press_release/2015/07/WC500190447.pdf

- 11.Kaslow DC, Biernaux S. RTS,S: toward a first landmark on the malaria vaccine technology roadmap. Vaccine. 2015;33(52):7425–7432. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moorthy VS, Ballou WR. Immunological mechanisms underlying protection mediated by RTS,S: a review of the available data. Malar J. 2009;8(1):312. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansong D, Asante KP, Vekemans J, Owusu SK, Owusu R, Brobby NAW, Dosoo D, Osei-Akoto A, Osei-Kwakye K, Asafo-Adjei E, et al. T cell responses to the RTS,S/AS01e and RTS,S/AS02D malaria candidate vaccines administered according to different schedules to Ghanaian children. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun P, Schwenk R, White K, Stoute JA, Cohen J, Ballou WR, Voss G, Kester KE, Heppner DG, Krzych U. Protective immunity induced with malaria vaccine, RTS,S, is linked to plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells producing IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 2003;171(12):6961–6967. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley EM, Stewart VA. Immune mechanisms in malaria: new insights in vaccine development. Nat Med. 2013;19(2):168–178. doi: 10.1038/nm.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organizaation . Weekly epidemiological record. World Health Organ Geneva. 2016;91(4):33–52. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-2-15.Voir. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon DM, Mc Govern TW, Krzych U, Cohen JC, Schneider I, La Chance R, Heppner DG, Yuan G, Hollingdale M, Slaoui M, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of a recombinantly produced plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein-hepatitis b surface antigen subunit vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1995;171(6):1576–1585. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoute JA, Slaoui M, Heppner DG, Momin P, Kester KE, Desmons P, Wellde BT, Garçon N, Krzych U, Marchand M, et al. A preliminary evaluation of a recombinant circumsporozoite protein vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. RTS,S malaria vaccine evaluation group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(2):86–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701093360202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bojang KA, Milligan PJM, Pinder M, Vigneron L, Alloueche A, Kester KE, Ballou WR, Conway DJ, Reece WHH, Gothard P, et al. Efficacy of RTS,S/AS02 malaria vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum infection in semi-immune adult men in the Gambia: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358(9297):1927–1934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06957-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alonso PL, Sacarlal J, Aponte JJ, Leach A, Macete E, Milman J, Mandomando I, Spiessens B, Guinovart C, Espasa M, et al. Efficacy of the RTS,S/AS02A vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum infection and disease in young African children: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9443):1411–1420. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17223-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aponte JJ, Aide P, Renom M, Mandomando I, Bassat Q, Sacarlal J, Manaca MN, Lafuente S, Barbosa A, Leach A, et al. Safety of the RTS,S/AS02D candidate malaria vaccine in infants living in a highly endemic area of Mozambique: a double blind randomised controlled phase I/IIb trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9598):1543–1551. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bejon P, Lusingu J, Olotu A, Leach A, Lievens M, Vekemans J, Mshamu S, Lang T, Gould J, Dubois M-C, et al. Efficacy of RTS,S/AS01E vaccine against malaria in children 5 to 17 months of age. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(24):2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdulla S, Oberholzer R, Juma O, Kubhoja S, Machera F, Membi C, Omari S, Urassa A, Mshinda H, Jumanne A. Safety and immunogenicity of RTS, S/AS02D malaria vaccine in infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(24):2533–2544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agnandji ST, Lell B, Soulanoudjingar SS, Fernandes JF, Abossolo BP, Conzelmann C, Methogo BGNO, Doucka Y, Flamen A, Mordmüller B, et al. First results of phase 3 trial of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in African children. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(20):1863–1875. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agnandji ST, Lell B, Fernandes JF, Abossolo BP, Methogo BGNO, Kabwende AL, Adegnika AA, Mordmüller B, Issifou S, Kremsner PG, et al. A phase 3 trial of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in African infants. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(24):2284–2295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership . Efficacy and safety of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine during 18 months after vaccination: A phase 3 randomized, controlled trial in children and young infants at 11 African sites. PLoS Med. 2014;11(7):e1001685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bejon P, White MT, Olotu A, Bojang K, Lusingu JPA, Salim N, Otsyula NN, Agnandji ST, Asante KP, Owusu-Agyei S, et al. Efficacy of RTS,S malaria vaccines: individual-participant pooled analysis of phase 2 data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(4):319–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70005-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey JA, Mvalo T, Aragam N, Weiser M, Congdon S, Kamwendo D, Martinson F, Hoffman I, Meshnick SR, Juliano JJ. Use of massively parallel pyrosequencing to evaluate the diversity of and selection on plasmodium falciparum csp T-cell epitopes in Lilongwe, Malawi. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(4):580–587. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moise L, Gutierrez A, Kibria F, Martin R, Tassone R, Liu R, Terry F, Martin B, De Groot AS. iVAX: an integrated toolkit for the selection and optimization of antigens and the design of epitope-driven vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(9):2312–2321. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1061159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nardin EH, Nussenzweig RS. T cell responses to pre-erythrocytic stages of malaria: role in protection and vaccine development against pre-erythrocytic stages. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;(11)687–727. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.003351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plotkin S, Orenstein W, Offit P, Edwards K. Plotkin’s vaccines. Seventh. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moise L, Gutierrez AH, Bailey-Kellogg C, Terry F, Leng Q, Abdel Hady KM, VerBerkmoes NC, Sztein MB, Losikoff PT, Martin WD, et al. The two-faced T cell epitope: examining the host-microbe interface with JanusMatrix. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(7):1577–1586. doi: 10.4161/hv.24615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeeshan M, Alam MT, Vinayak S, Bora H, Tyagi RK, Alam MS, Choudhary V, Mittra P, Lumb V, Bharti PK, et al. Genetic variation in the plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein in india and its relevance to RTS,S malaria vaccine. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Losikoff PT, Mishra S, Terry F, Gutierrez A, Ardito MT, Fast L, Nevola M, Martin WD, Bailey-Kellogg C, De Groot AS, et al. HCV epitope, homologous to multiple human protein sequences, induces a regulatory T cell response in infected patients. J Hepatol. 2015;62(1):48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu R, Moise L, Tassone R, Gutierrez AH, Terry FE, Sangare K, Ardito MT, Martin WD, De Groot AS. H7N9 T-cell epitopes that mimic human sequences are less immunogenic and may induce treg-mediated tolerance. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(9):2241–2252. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1052197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gutiérrez AH, Rapp-Gabrielson VJ, Terry FE, Loving CL, Moise L, Martin WD, De Groot AS. T-cell epitope content comparison (EpiCC) of swine H1 influenza A virus hemagglutinin. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2017;11(6):531–542. doi: 10.1111/irv.12513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffman SL, Isenbarger D, Long GW, Sedegah M, Szarfman A, Waters L, Hollingdale MR, van der Meide PH, Finbloom DS, Ballou WR. Sporozoite vaccine induces genetically restricted T cell elimination of malaria from hepatocytes. Science. 1989;244(4908):1078–1081. doi: 10.1126/science.2524877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiss WR, Mellouk S, Houghten RA, Sedegah M, Kumar S, Good MF, Berzofsky JA, Miller LH, Hoffman SL. Cytotoxic T cells recognize a peptide from the circumsporozoite protein on malaria-infected hepatocytes. J Exp Med. 1990;171(3):763–773. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charoenvit Y, Collins WE, Jones TR, Millet P, Yuan L, Campbell GH, Beaudoin RL, Broderson JR, Hoffman SL. Inability of malaria vaccine to induce antibodies to a protective epitope within its sequence. Science. 1991;251(4994):668–671. doi: 10.1126/science.1704150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charoenvit Y, Mellouk S, Cole C, Bechara R, Leef MF, Sedegah M, Yuan LF, Robey FA, Beaudoin RL, Hoffman SL. Monoclonal, but not polyclonal, antibodies protect against Plasmodium yoelii sporozoites. J Immunol. 1991;146:1020–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crotty S. Follicular helper CD4 T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29(1):621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laidlaw BJ, Craft JE, Kaech SM. The multifaceted role of CD4+ T cells in CD8+ T cell memory. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(2):102–111. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bronke C, Almeida CAM, Mckinnon E, Roberts SG, Keane NM, Chopra A, Carlson JM, Heckerman D, Mallal S, John M. HIV escape mutations occur preferentially at HLA-binding sites of CD8 T-cell epitopes. Aids. 2013;27(6):899–905. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835e1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vossen MTM, Westerhout EM, Söderberg-Nauclér C, Wiertz EJHJ. Viral immune evasion: A masterpiece of evolution. Immunogenetics. 2002;54(8):527–542. doi: 10.1007/s00251-002-0493-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.John M, Gaudieri S. Influence of HIV and HCV on T cell antigen presentation and challenges in the development of vaccines. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:514. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Good MF, Pombo D, Maloy WL, de la Cruz VF, Miller LH, Berzofsky JA. Parasite polymorphism present within minimal T cell epitopes of Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein. J Immunol. 1988;140:1645–1650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hill AV, Elvin J, Willis AC, Aidoo M, Allsopp CE, Gotch FM, Gao XM, Takiguchi M, Greenwood BM, Townsend AR, et al. Molecular analysis of the association of HLA-B53 and resistance to severe malaria. Nature. 1992;360(6403):434–439. doi: 10.1038/360434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Good MF, Kumar S, Miller LH. The real difficulties for malaria sporozoite vaccine development: nonresponsiveness and antigenic variation. Immunol Today. 1988;9(11):351–355. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(88)91336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Good MF, Pombo D, Quakyi IA, Riley EM, Houghten RA, Menon A, Alling DW, Berzofsky JA, Miller LH. Human T-cell recognition of the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum: immunodominant T-cell domains map to the polymorphic regions of the molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(4):1199–1203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Groot AS, Moise L, Liu R, Gutierrez AH, Tassone R, Bailey-Kellogg C, Martin W. Immune camouflage: relevance to vaccines and human immunology. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(12):3570–3575. doi: 10.4161/hv.36134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen J, Garcon N, Voss G, inventors; GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA, assignee. Vaccines. United States patent US20050002958A1. 2005. January 6.

- 52.Southwood S, Sidney J, Kondo A, Del Guercio MF, Appella E, Hoffman S, Kubo RT, Chesnut RW, Grey HM, Sette A. Several common HLA-DR types share largely overlapping peptide binding repertoires. J Immunol. 1998;160:3363–3373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moise L, Beseme S, Tassone R, Liu R, Kibria F, Terry F, Martin W, De Groot AS. T cell epitope redundancy: cross-conservation of the TCR face between pathogens and self and its implications for vaccines and autoimmunity. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016;15(5):607–617. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2016.1123098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- World Health Organisation . WHO | malaria. WHO. 2017. [accessed 2017 June 23]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/#.WU1EUDkCfpE.mendeley

- European Medicines Agency . First malaria vaccine receives positive scientific opinion from EMA. European Medicines Agency; 2015. Jul 24 [accessed 2017 Dec 10]. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Press_release/2015/07/WC500190447.pdf