Ghaedi et al. identify IL-18R+IL-33R− ILC progenitors, which differentiate into multiple ILC lineages, in the lung of neonatal and adult RORα lineage tracer mice. ILC2s in neonatal mouse lungs are divided into distinct cytokine and amphiregulin-producing effector ILC2s.

Abstract

Lung group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) drive allergic inflammation and promote tissue repair. ILC2 development is dependent on the transcription factor retinoic acid receptor–related orphan receptor (RORα), which is also expressed in common ILC progenitors. To elucidate the developmental pathways of lung ILC2s, we generated RORα lineage tracer mice and performed single-cell RNA sequencing, flow cytometry, and functional analyses. In adult mouse lungs, we found an IL-18Rα+ST2− population different from conventional IL-18Rα−ST2+ ILC2s. The former was GATA-3intTcf7EGFP+Kit+, produced few cytokines, and differentiated into multiple ILC lineages in vivo and in vitro. In neonatal mouse lungs, three ILC populations were identified, namely an ILC progenitor population similar to that in adult lungs and two distinct effector ILC2 subsets that differentially produced type 2 cytokines and amphiregulin. Lung ILC progenitors might actively contribute to ILC-poiesis in neonatal and inflamed adult lungs. In addition, neonatal lung ILC2s include distinct proinflammatory and tissue-repairing subsets.

Introduction

The family of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) includes cytotoxic natural killer (NK) cells and cytokine-producing ILCs (Eberl et al., 2015; Klose and Artis, 2016; Diefenbach et al., 2014; Artis and Spits, 2015; Spits et al., 2013). Cytokine-producing ILCs are divided into three groups: group 1 (ILC1s), group 2 (ILC2s), and group 3 (ILC3s). ILCs develop from ILC progenitors (ILCPs) in the bone marrow (BM; Yang et al., 2015; Klose et al., 2014; Constantinides et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2019). These BM progenitors differentiate along the ILC lineage as they gradually up-regulate the transcription factors TCF-1 (encoded by Tcf7), TOX (Tox), ID2 (Id2), and PLZF (Zbtb16; Yu et al., 2016; Ishizuka et al., 2016; Harly et al., 2018). ILC2-restricted progenitors termed ILC2 progenitors (ILC2Ps) have also been found in the BM (Halim et al., 2012b; Hoyler et al., 2012). ILC2s actively develop during the neonatal period and become long-lived tissue-resident cells in mucosal tissues, including the lung (Schneider et al., 2019; Ghaedi et al., 2016; Gasteiger et al., 2015). In mouse lungs, ILC2s can be defined as lineage marker negative (Lin−), positive for Thy1, IL-7 receptor α (IL-7Rα; CD127), IL-33R (ST2), and IL-2Rα (CD25). These cytokine receptors are important stimulatory receptors for ILC2s (Martinez-Gonzalez et al., 2015, 2016; Van Dyken et al., 2016). ILC2s express the transcription factors GATA3 and retinoic acid receptor–related orphan receptor (RORα), which are critically required for ILC2 development (Halim et al., 2012b; Wong et al., 2012; Hoyler et al., 2012; Mjösberg et al., 2012; Yagi et al., 2014; Tindemans et al., 2014), and are negative for the expression of the transcription factors Eomes, T-bet, and RORγt.

Lung ILC2s are stimulated by inhaled allergens or IL-33, and they produce large amounts of IL-5 and IL-13, which induce eosinophilic lung inflammation (Halim et al., 2012a). Activated ILC2s also produce amphiregulin (Monticelli et al., 2011, 2015), IL-4 (Pelly et al., 2016), IL-2 (Pelly et al., 2016), IL-9 (Wilhelm et al., 2011), and IL-10 (Seehus et al., 2017). They express KLRG1 (Chiossone and Vivier, 2017; Taylor et al., 2017), GITR/ligand (Nagashima et al., 2018; Rauber et al., 2017), and ICOS/ligand (Maazi et al., 2015; Molofsky et al., 2015; Rauber et al., 2017). These molecules enable ILC2s to interact with a variety of cell types and participate in a broad range of immune responses. However, it is unknown whether a single population of ILC2s produces all these molecules.

Initially, the ILC2 population was thought to be homogeneous. It has been reported that intraperitoneal injection of IL-25, or helminth infection, induces a population of KLRG1hiIL-25R+ ILC2s, termed inflammatory ILC2s, in the lung (Huang et al., 2015, 2018). These cells are not lung-resident at resting state. Instead they migrate from intestinal lamina propria to peripheral sites including the lung. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis of human ILCs in tonsil revealed distinct subpopulations of ILC3s (Björklund et al., 2016), whereas no heterogeneity among ILC2s was found. Moreover, scRNA-seq analysis of mouse ILCs in the small intestine divided intestinal ILC2s into four transcriptional states, designated ILC2a–ILC2d, based on graded expression of Gata3 and Klrg1 (Gury-BenAri et al., 2016). Flow cytometric analysis showed that >90% of intestinal ILC2s are KLRG1+ and included IL-5+IL-4− cells, whereas the small KLRG1− subset included rare IL-5−IL-4+ cells. In a more recent study, scRNA-seq analysis was performed on Il5+ ILC2s from the lung, gut, fat, and skin as well as Arg1+ cells from BM (Ricardo-Gonzalez et al., 2018; Zhu, 2018). All skin and ∼10% lung Il5+ ILC2s, as well as <5% BM Arg1+ cells, expressed IL-18Rα, but not ST2. IL-18 was required for optimal IL-5 and IL-13 production and proliferation of skin ILC2s in a model of atopic dermatitis. In contrast, lung Il5+ ILC2s upon in vitro stimulation with IL-18 produced barely detectable amounts of IL-13. In addition, intradermal injection of IL-18 resulted in minimal Il13 expression by lung Il5+ ILC2s. The biological significance of the IL-18Rα+ST2− ILC2s in the lung is unknown. Another recent analysis of human ILC2s in various tissues by mass cytometry found extensive heterogeneity among individuals and tissue origins (Simoni et al., 2017). Human peripheral blood ILC2s were IL-18Rα+, and they produced IL-5 and IL-13 upon stimulation with IL-18. However, it is unknown whether IL-18Rα is expressed by a subset of human ILC2s or on previously activated ILC2s. Although, these studies have shown that the ILC2 population can be more complex than previously thought, the functional significance and physiological relevance of ILC2 heterogeneity remains largely unknown.

Lung ILC2s are known to play an important role in the development of allergic inflammation, and ILC2 numbers are elevated in the peripheral blood and sputum of asthma patients (Smith et al., 2016; Ying et al., 2016). ILC2s are involved in other lung diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Silver et al., 2016), fibrosis (Hams et al., 2014), and tumors (Trabanelli et al., 2017; Chevalier et al., 2017). It is important to elucidate the complexity of the ILC2 population and the functional properties of stimulated ILC2 subsets, as well as their development, so that proper subsets are targeted in therapeutic interventions. To study lung ILC2 heterogeneity, we generated an ILC(2) lineage tracer mouse model based on the expression of the transcription factor RORα. Rorα is expressed in early ILCPs (Constantinides et al., 2014; Harly et al., 2018; Ishizuka et al., 2016; Lim et al., 2017) and mature ILCs (Robinette et al., 2015; Halim et al., 2012b; Wong et al., 2012; Lo et al., 2016; Hoyler et al., 2012). Therefore, RORα lineage tracer mice enabled us to identify ILCPs and mature ILC2s in the lung without relying on their expression of cell surface markers, specific cytokines, or enzymes. To further adopt an unbiased and comprehensive approach for studying ILC2 heterogeneity, we analyzed all adult and neonatal lung CD45lo/+Linlo cells by scRNA-seq and confirmed the results by flow cytometric and functional analyses. ILC2 development starts soon after birth, and neonatal lung ILC2s are activated by endogenous IL-33 release (Ghaedi et al., 2016; de Kleer et al., 2016; Saluzzo et al., 2017; Steer et al., 2017). Therefore, we analyzed both adult and neonatal lungs to gain insight into ILC2 development and heterogeneity. By this approach, we have identified ILCPs in both adult and neonatal lungs, which might actively contribute to the generation of ILC2s in the neonatal and inflamed adult lungs. We have also identified effector ILC2 subsets that have distinct functions and differentiation requirements in neonatal lungs.

Results

RORα lineage tracing marks lung ILCs, including ILC2s

We generated RORα lineage tracer mice by crossing Rora-IRES-Cre (Chou et al., 2013) and R26R-EYFP mice, which have a loxP-flanked transcription stop sequence followed by the gene encoding YFP in the ROSA26 locus. In these RORα-YFP mice, cells expressing Rorα during their development should be irreversibly labeled by YFP. As expected, most (>80%) ILC2s, defined as Lin−GATA-3+ST2+Thy1+ (Fig. 1 A) or Lin−CD127+Thy1+ST2+CD25+ (Fig. S1 A), were YFP+ in naive adult mice. Intranasal IL-33 treatment resulted in the expansion of the YFP+ ILC2s. Neonatal lung ILC2s were also labeled by YFP. Less than 1% of B (CD19+) and 1.5% T cells (TCRαβ/γδ+) in adult lungs expressed YFP (Fig. S1 B). Approximately 9% of TCRαβ/γδ−NKp46+ lung cells were also YFP+, most of which were NK cells coexpressing Eomes and T-bet (Fig. S1 C). In the BM, ∼10% of ILCPs defined by Lin−Thy1+CD127+PD-1+α4β7+CD25− (Yu et al., 2016) were YFP+ (Fig. S1 D). In contrast, the majority (>70%) of ILC2Ps were YFP+. Small intestine ILC2s and ILC3s were also labeled by YFP (Fig. S1 E).

Figure 1.

ILCs in RORα-YFP mice express YFP. (A) Lung ILC2s from naive and IL-33–treated adult as well as neonatal (12-d-old) mice were sequentially gated by Lin−GATA-3+ST2+Thy1+, and their expression of YFP in RORα-YFP (black line) and B6 control (filled gray) mice is shown. (B) Lin−YFP+ cells from adult and neonatal lungs as well as adult small intestine were gated and analyzed for the expression of GATA-3 and RORγt as well as GATA-3 and Thy1. Lung Lin−YFP+Thy1+ cells were further analyzed for the expression of ST2 and CD25. Data are representative of three or more independent experiments with three or more mice per group in each experiment.

Figure S1.

YFP expression in lymphoid populations of lung, BM, and intestine of RORα-YFP mice. (A) Lung ILC2s from naive and IL-33–treated adult as well as neonatal (12-d-old) mice were sequentially gated by Lin−CD127+Thy1+ST2+CD25+, and their expression of YFP in RORα-YFP (black line) and B6 control (filled gray) mice is shown. (B–E) YFP expression by adult lung CD19+ B cells and TCRαβ/γδ+ T cells (B), TCRαβ/γδ−NKp46+ (YFP+TCRαβ/γδ−NKp46+ are analyzed for Eomes and T-bet expression; C), BM Lin−Thy1+CD127+PD-1+α4β7+CD25− ILCPs and Lin−CD127+Thy1+ST2+ ILC2Ps (D), and intestinal Lin−RORγ−GATA-3+ ILC2s and Lin−RORγt+GATA-3int ILC3s (E) in RORα-YFP (black line) and B6 control (filled gray) mice is shown.

The Lin−YFP+ cells in adult and neonatal lungs were RORγt− and included GATA-3hiThy1+, GATA-3loThy1+, and GATA-3−Thy1− cells (Fig. 1 B). The Thy1+ cells included ST2+CD25+ ILC2s and a small fraction of ST2−CD25− cells. The GATA-3−Thy1− cells were negative for the expression of all lymphoid-associated markers tested (data not shown). The Lin−YFP+ cells in the intestine included GATA-3+RORγt− ILC2s and GATA-3loRORγt+ ILC3s. ILC1s and NK cells were excluded from the Lin−YFP+ population in our analyses, and RORγt+ILC3s were scarce in the lung. Hence, these results suggested that Lin−YFP+GATA-3loThy1+ST2−CD25− cells might belong to the ILC lineage. These cells are further characterized below.

scRNA-seq analysis identifies two ILC2 subsets in adult RORα-YFP mouse lungs

Not all lung ILC2s were YFP+ (Fig. 1 A), and not all lung Lin−YFP+Thy1+ cells expressed ST2 and CD25 (Fig. 1 B) in RORα-YFP mice. To study the ILC2 lineage in the least biased way possible, we decided to purify and analyze all CD45lo/+Linlo cells (Fig. 2 A) from adult (6–9-wk-old) RORα-YFP mouse lungs by droplet-based scRNA-seq. We performed unsupervised clustering of the cells in this dataset using Seurat package (Butler et al., 2018), which identified 16 distinct clusters (Fig. 2, B and C) based on the positive and negative markers of each cellular cluster compared with all other clusters. The ILC2 cluster was identified by the expression of ILC2-associated genes, including Areg, Il7r, Rora, and Gata3 (Fig. 2 C and Table S1), and the lack of expression of stromal, NK/ILC1, B, and T cell genes. The ILC2 cluster was also evident on the t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) plot based on its expression of Rora, Gata3, and Il1rl1 (Fig. S2 A). Stromal, NK, B, and T cell clusters were also identified (Fig. 2, B and C; and Table S1). Yfp was mostly expressed in the ILC2, NK, and stromal cell clusters (Fig. S2 A). Yfp+ NK and stromal cell clusters did not express Rorα, suggesting that these cells developed from Rorα-positive progenitors.

Figure 2.

ScRNA-seq analysis of adult RORα-YFP mouse lungs identifies two distinct ILC2 subsets. (A) Gating strategy for the purification of Linlo cells from adult RORα-YFP mouse lungs for scRNA-seq analysis. (B) t-SNE plot shows distinct clusters within the 4,664 sequenced cells. (C) Heatmap of the differentially expressed genes by the clusters from B. Top 10 differentially expressed transcripts of the lymphoid lineages are shown. (D) The ILC2 cluster from B was subjected to further unsupervised clustering that divided the 371 ILC2s into subset 1 (233 cells) and subset 2 (138 cells). Heatmap shows the top 20 genes that are differentially expressed by the subsets 1 and 2. The arrows point to the genes that are mentioned in the text. (E) Heatmap shows the expression of our selection of ILC(2)-associated genes by subsets 1 and 2. This gene list includes the transcription factors, cell surface receptors, and effector cytokines important for ILC(2) lineage development and function based on the literature. Hence, it includes genes that are equally expressed as well as genes that are differentially expressed by the two subsets. The differentially expressed genes are shown by black (higher expression on subset 1) and green (higher expression on subset 2) boxes. The rest of the genes are similarly expressed by the two subsets.

Figure S2.

Gene expression profiles of adult lung ILC2 cluster and subsets 1 and 2. (A) t-SNE plots showing expression of the indicated individual genes. (B and C) Heatmap shows all the genes that are differentially expressed (P ≤ 0.05) by the adult ILC2 subsets. Genes that have higher expression in subset 1 than subset 2 (B), as well as genes that have higher expression in subset 2 than subset 1 (C), are shown. The arrows point to the genes that are mentioned in the text.

Table S1. Top 20 genes differentially expressed by the 16 clusters in the adult dataset.

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Cluster 7 | Cluster 8 | Cluster 9 | Cluster 10 | Cluster 11 | Cluster 12 | Cluster 13 | Cluster 14 | Cluster 15 | Cluster 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gsn | S100a4 | Gzma | Igkc | Cd3d | Cbr2 | Scgb3a1 | Cox6a2 | Car4 | Ccl21a | Upk3b | 2810417H13Rik | Cd79a | Hhip | S100g | Hbb-bt |

| Dcn | Areg | Fcer1g | Iglc2 | Cd3g | Hp | Bpifa1 | Siglech | Cldn5 | Mmrn1 | Gpm6a | Birc5 | Ly6d | Enpp2 | Slc34a2 | Alas2 |

| Clec3b | Il7r | Tyrobp | Ly6d | Trac | Sftpb | Scgb3a2 | Alox5ap | Ramp2 | Lyve1 | Msln | Ccnb2 | Iglc2 | Tagln | Pla2g1b | Hbb-bh1 |

| Apoe | Rgcc | Nkg7 | Iglc1 | Trbc2 | Scgb1c1 | Reg3g | Ccr9 | Emp2 | Ptprb | Upk1b | Rrm2 | Ms4a1 | Mustn1 | Ager | Hba-a2 |

| Serping1 | Ramp1 | Ccl5 | Cd79a | Cd3e | Sftpa1 | Bpifb1 | Cd300c | Egfl7 | Cldn5 | Cldn15 | Ube2c | Fcer1g | Thbs1 | Lyz1 | Snca |

| Inmt | Rora | Klrd1 | Cd74 | Ms4a6b | Cyp2f2 | Wfdc2 | Lair1 | Ecscr | Egfl7 | Igfbp5 | Hist1h2ap | Cd79b | Aspn | Cxcl15 | Hba-a1 |

| Mgp | Gata3 | Klre1 | Cd79b | Cd28 | Wfdc2 | Tff2 | Mpeg1 | Kdr | Gpihbp1 | Nkain4 | Top2a | Iglc1 | Acta2 | Chil1 | Hbb-bs |

| Serpinf1 | Ccr8 | Klrk1 | Ighm | Ms4a4b | Scgb3a2 | Lypd2 | Sh3bgr | Cyp4b1 | Apold1 | Sbsn | Stmn1 | Ighm | Bmp5 | Lyz2 | Bpgm |

| Cyr61 | Fgl2 | AW112010 | Ms4a1 | Cd8b1 | Sfta2 | Cyp2f2 | Smim5 | Calcrl | Ramp2 | Krt19 | Cks1b | Igkc | Cyp2e1 | Lcn2 | Fam220a |

| Id3 | Thy1 | Klra4 | Iglc3 | Lat | Sftpd | Cxcl17 | Cybb | Tmem100 | Gng11 | Clu | Smc2 | Tyrobp | Grem2 | Sfta2 | Ube2l6 |

| Igfbp4 | Ccdc184 | Klra7 | Vpreb3 | Lef1 | Dcxr | Sult1d1 | Pld4 | Cd36 | Aqp1 | Cav1 | Dut | Cd74 | Serpine2 | Sftpc | Isg20 |

| Col1a2 | Emb | Ctsw | Ebf1 | Gm8369 | Ldhb | Fxyd3 | Rnase6 | Cdh5 | Sdpr | Igfbp6 | Hmgn2 | Ebf1 | Igfbp5 | Sftpd | Cabin1 |

| Fbln1 | Zcchc10 | Klra1 | Cd24a | Hcst | Gsta4 | Gsto1 | Plaur | Ednrb | Tm4sf1 | Slpi | Hmgb2 | Gzma | Adamts1 | Sftpb | Cd3e |

| Timp3 | Itgb7 | Xcl1 | Fcmr | Tcf7 | Selenbp1 | Cbr2 | Bst2 | Kitl | S100a16 | Tm4sf1 | Tuba1b | Dok3 | P2ry14 | Sftpa1 | Mta2 |

| Pcolce2 | Ltb | Ncr1 | Siglecg | Trdc | Gsta3 | Krt18 | Ctsh | Icam2 | Prss23 | Aqp1 | Cenpa | Ccl3 | Myl9 | Bex2 | Ppp1r12a |

| Mfap5 | Furin | Ccl4 | H2-Ab1 | Lck | Scgb1a1 | Gsta4 | Tcf4 | Acvrl1 | Hpgd | Hspb1 | H2afx | Ncr1 | Lum | Fabp5 | 1810058I24Rik |

| Cxcl12 | Gadd45b | Ccl3 | H2-Eb1 | Ikzf2 | Retnla | Hp | Plac8 | Ly6c1 | Fxyd6 | Csrp2 | 2700094K13Rik | Vpreb3 | Egr1 | Wfdc2 | Mkrn1 |

| Sparc | Nfkb1 | Klra9 | H2-Aa | Ccl5 | Mgst1 | Retnla | Irf8 | Crip2 | Ifitm3 | Rarres2 | H2afz | Spib | Ier3 | Napsa | Sdha |

| Pi16 | Tcrg-C4 | Spry2 | Cd72 | Ly6c2 | Lypd2 | Mgst1 | Tyrobp | Tspan13 | Ier3 | Aebp1 | Tubb5 | Ighd | Tppp3 | Elovl1 | |

| Mt1 | Ccl1 | Gzmb | Iglv1 | Trbc1 | Prdx6 | Scgb1a1 | Ccl4 | Ly6a | Sepp1 | Fxyd3 | H2afv | Gm8369 | Atf3 | Npc2 |

The table shows the top 20 genes that are differentially expressed (P ≤ 0.01) by each cluster in Fig. 2, B and C. The genes were selected by the FindMarkers function in the Seurat package.

We first isolated the ILC2 cluster from the dataset (Fig. 2, B and C). Although the ILC2 cluster minimally contained contaminating cells from other lineages, we removed any potential remaining contaminating from this cluster by filtering out any cells expressing Cd79a, Cd79b, Ms4a1, Ebf1, or Pax5 (B cells); cells expressing Gzma, Gzmb, Eomes, Ncr1, or Prf1 (NK/ILC1s); cells expressing Scgb3a1 (stromal cells); cells coexpressing any TCR genes and Cd4, Cd8a, or Cd5 (T cells); and cells coexpressing any TCR genes and Klrk1 (NKT cells). Rorc-expressing cells were rarely found (Fig. S2 A); hence, we did not filter out these cells. We then subjected the remaining cells within ILC2 cluster to further unsupervised clustering, which divided ILC2s into two subsets (1 and 2), each expressing a distinct set of genes. Subset 1 highly expressed the conventional ILC2-associated genes, including Il1rl1 (ST2; Halim et al., 2012a, 2012b), Tnfrsf18 (GITR; Nagashima et al., 2018), Areg (amphiregulin; Monticelli et al., 2015, 2011; Figs. 2 D and S2 B), and Arg1 (arginase-1; Bando et al., 2013; Monticelli et al., 2016; Fig. S2 B). In contrast, subset 2 infrequently expressed Il1rl1 and Tnfrsf18 and instead had high expression of Cd7 (CD7), Runx3 (Runx3; Figs. 2 D and S2 C), Cd2 (CD2), Tcf7 (TCF-1), and Il18r1 (IL-18rα; Fig. S2 C). The two subsets equally expressed Id2, Gata3, Rora, Il7r, Thy1, and YFP (Fig. 2 E). It is notable that both subsets lacked expression of Tbx21 and Rorc, excluding the possibility of them being NK/ILC1s or ILC3s.

Adult lung ILC2s are divided into IL-18Rα+ST2− and IL-18Rα−ST2+ subsets

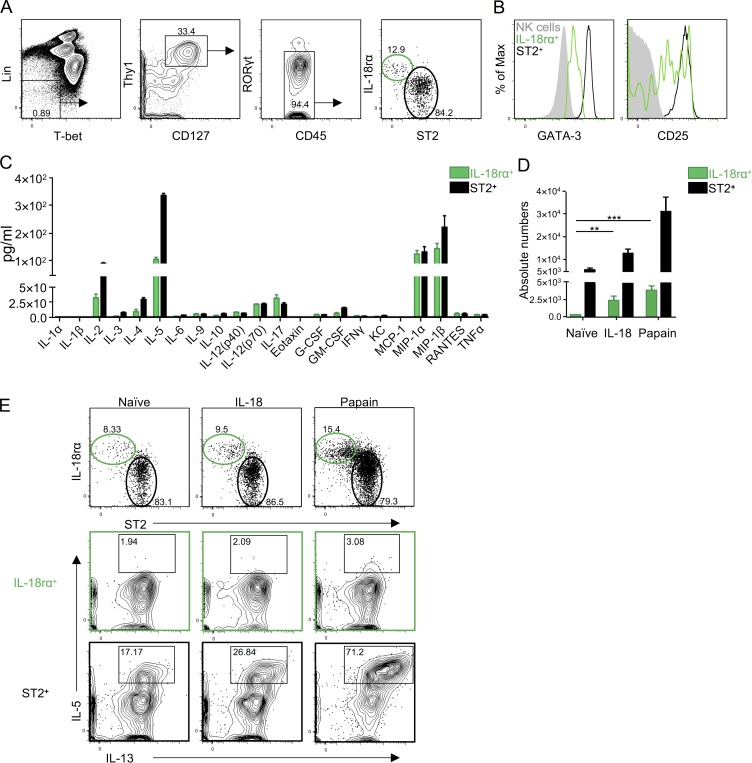

The two ILC2 subsets detected by scRNA-seq analysis lacked expression of Tbx21 and Rorc, expressed Thy1, Il7r, and Yfp, and differentially expressed Il1rl1 and Il18r1. Hence, we analyzed T-bet−Lin−YFP+Thy1+CD127+RORγt− cells in adult Rorα-YFP mouse lungs for IL-18Rα and ST2 expression by flow cytometry (Fig. 3 A). These cells were divided into two subsets, namely the IL-18Rα−ST2+ conventional ILC2s and a small IL-18Rα+ST2− subset. The IL-18Rα+ cells had intermediate expression of GATA-3 and CD25 in comparison with NK cells and ST2+ ILC2s (Fig. 3 B). Both subsets had lower expression of KLRG1 and IL-25R compared with mesenteric lymph node ILC2s. IL-18Rα+ cells had lower expression of GITR compared with ST2+ ILC2s. Lin−YFP+Thy1+CD127+IL-18Rα+ cells and ST2+ ILC2s were first analyzed for RORγt and T-bet expression to assess the potential for ILC1/NK and ILC3 contamination during sort purification (Fig. 3 C). IL-18Rα+ cells included negligible percentages of RORγt/T-bet–expressing cells. IL-18Rα+ cells and ST2+ ILC2s were purified from naive Rorα-YFP mouse lungs and stimulated with PMA and ionomycin to test their capacities to produce cytokines. The culture supernatants were analyzed for multiple cytokines. The IL-18Rα+ cells produced IL-5, albeit in much lower amounts than ST2+ ILC2s (Fig. 3 D). IL-18Rα+ cells also produced small amounts of IL-2, IL-4, and IL-17 and high amounts of MIP-1α and MIP-1β, whereas IFN-γ and TNF-α were undetectable. We also tested whether IL-18Rα+ and ST2+ subsets would respond differentially to intranasal IL-18 and the protease allergen papain treatments. IL-18 treatment increased the numbers of IL-18Rα+ cells, but not ST2+ ILC2s (Fig. 3 E). Papain treatment increased the numbers of both subsets. Neither IL-18 nor papain induced expression of intracellular IL-5/IL-13 by IL-18Rα+ cells (Fig. 3 F). However, ST2+ ILC2s expressed both these cytokines after papain treatment.

Figure 3.

Flow cytometric and functional analyses confirm two distinct adult lung ILC subsets. (A) Tbet−Lin−YFP+Thy1+CD127+RORγt− cells were sequentially gated and divided into IL-18Rα+ST2− (green) and IL-18Rα−ST2+ (black) subsets in adult RORα-YFP mouse lungs. (B) The expression of GATA-3, CD25, KLRG1, IL-25R, and GITR by lung IL-18Rα+ cells (green) and ST2+ ILC2s (black) in A are shown. Lung NK cells (NKp46+Eomes+T-bet+; filled gray) and mesenteric lymph node (MLN) ILC2s (filled red) were used as controls. (C) Lin−YFP+Thy1+CD127+IL-18Rα+ST2− (green) and IL-18Rα−ST2+ (black) were analyzed for the expression of RORγt and T-bet. (D) Lin−YFP+Thy1+CD127+ cells were sorted into IL-18Rα+ cells (green) and ST2+ ILC2s (black) and stimulated for 72 h with PMA and ionomycin. The amounts of cytokines and chemokines in the culture supernatants were determined. (E) Absolute numbers of IL-18Rα+ cells (green) and ST2+ ILC2s (black) gated as in A in naive, IL-18, and papain-treated lungs are shown. (F) Lin−YFP+Thy1+CD127+IL-18Rα+ cells (green) and ST2+ ILC2s (black) were analyzed for intracellular IL-5 and IL-13 in naive, IL-18, and papain-treated lungs. (G) Lin−Thy1+CD127+IL-18Rα+ cells (green) and ST2+ ILC2s (black) were analyzed for Tcf7EGFP and Kit expression in naive and papain-treated Tcf7EGFP adult mouse lungs. (H) Tbet−Lin−Thy1+CD127+RORγt− cells were analyzed for TCF-1 and ST2 expression in naive and papain-treated lungs. Data in A–E are representative of three or more independent experiments with three or more mice per group in each experiment, and data in F and G are representative of two independent experiments with two or more mice per group in each experiment (mean ± SEM). *, P ≤ 0.05 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

As shown above, the IL-18Rα+ subset had lower expression of GATA-3 and CD25 than ST2+ ILC2s and produced very few cytokines, suggesting that they might be immature ILCs. The scRNA-seq analysis showed that IL-18Rα+ cells also expressed Tcf7, which is expressed by BM ILCPs (Yang et al., 2015; Harly et al., 2018). Therefore, we analyzed their expression of Tcf7 using Tcf7EGFP mice. A fraction of lung Lin−Thy1+CD127+IL-18Rα+ cells were Tcf7EGFP+ (Fig. 3 G), whereas the ST2+ ILC2s were negative. These IL-18Rα+Tcf7EGFP+ cells expressed Kit and expanded following papain treatments. We also further confirmed that IL-18Rα+ cells, but not ST2+ ILC2s, expressed the TCF-1 protein in naive and papain-treated lungs (Fig. 3 H). These results indicated that the IL-18Rα+ cells belong to the ILC lineage but are distinct from ST2+ ILC2s and other ILCs in the lung.

Adult lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs can give rise to multiple ILC lineages

We purified Lin−YFP+Thy1+CD127+IL-18Rα+ST2− cells from papain-treated adult Rorα-YFP mouse (CD45.2) lungs. Rorα-YFP mice were pretreated with intranasal papain to expand these cells and allow purification of enough numbers. These cells were then transplanted into lethally irradiated B6.Ly5SJL (Pep3b) mice (CD45.1). As controls, we purified all-lymphoid progenitors (ALPs; Inlay et al., 2009) and ILCPs (Yu et al., 2016) from Rorα-YFP mouse BM. While BM ALPs gave rise to a variety of lymphoid lineages, BM ILCPs and lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs gave rise to ILC2s (Lin−T-bet−Thy1+ST2+CD127+GATA-3+) and Lin+T-bet+Thy1−CD127−cells in the lung of the recipient mice (Fig. 4 A). Because the Lin cocktail in this analysis included NKp46, these cells might be ILC1s/NK cells. Therefore, we analyzed the livers of the recipient mice. BM ALPs gave rise to NKp46+T-bet+Eomes− ILC1s and Eomes+ NK cells (Fig. 4 B). BM ILCPs also gave rise to both ILC1s and a small number of NK cells. Lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs gave rise to ILC1s but a barely detectable number of NK cells. All of the progenitor populations tested also gave rise to Lin−NKp46− cells in the liver, which might include other ILCs. BM ILCPs and lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs generated comparable numbers of ILC2s and ILC1s (Fig. 4 C). However, lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs generated significantly fewer NK cells.

Figure 4.

Adult lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs have similar differentiation properties as BM ILCPs. BM ALPs (Lin−Flt3+CD127+Ly6D−CD25−Thy1−), ILCPs (Lin−Thy1+CD127+PD-1+α4β7+CD25−), or lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs (Lin−YFP+Thy1+CD127+IL-18Rα+ST2−) were purified by from papain-treated RORα-YFP mice (CD45.2+) and injected (2,000 cells per mouse) intravenously into lethally irradiated Pep3b mice (CD45.1+). The tissues of the recipient mice were analyzed 6 wk after transplantation. (A) Donor-derived lung ILC2s were sequentially gated by CD45.1−CD45.2+Lin−T-bet−Thy1+ST2+CD127+GATA-3+ (pink gates). The Lin cocktail in this analysis included anti-CD3e, TCRαβ, TCRγδ, CD19, NKp46, CD11b, CD11c, Gr-1, and Ter119. Donor-derived Lin+T-bet+ cells were also gated and analyzed for Thy1 and CD127 expression. (B) Donor-derived liver cells were gated by CD45.1−CD45.2+Lin−NKp46+ and further divided into T-bet+Eomes− ILC1s and T-bet+Eomes+ NK cells. The Lin cocktail in this analysis included anti-CD3e, TCRαβ, TCRγδ, CD19, Gr-1, and Ter119. (C) Absolute numbers of donor-derived lung ILC2s, liver ILC1s, and NK cells. (D) BM ILCPs or lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs were purified as in A, and 1,000 cells each were cultured on OP9-DL1 with IL-7 and SCF for 1 wk. The progenies were analyzed for Thy1 and NKp46 expression. Thy1+NKp46− cells were further analyzed for ICOS expression. Frequencies of the indicated subsets are shown in pie charts. (E) BM ILCPs or lung Lin−Rorc(γt)-EGFP−Thy1+CD127+IL-18Rα+ST2− cells were purified from papain-treated Rorc(γt)-EGFP+/− mice and cultured on OP9-DL1 with IL-7 and SCF for 1 wk. The progenies were analyzed for Thy1 and NKp46 expression and Thy1+NKp46+ cells were further analyzed for Rorc(γt)-EGFP expression. Data in A–C are representative of four independent experiments with three or more mice per group in each experiment, and data in D and E are representative of ≥10 replicates per experimental group in two independent experiments (mean ± SEM). *, P ≤ 0.05 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

We also cultured lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs purified from papain-treated adult Rorα-YFP mouse lungs on OP9-DL1 (Schmitt and Zúñiga-Pflücker, 2002) with IL-7 and stem cell factor (SCF) to test their differentiation in vitro. BM ILCPs were cultured as control. After 1 wk, both populations generated three distinct subsets based on the expression of Thy1 and NKp46 (Fig. 4 D). The Thy1+NKp46− subset derived from BM ILCPs included ICOS+ and ICOS− cells, and these ICOS− cells constituted a half of the BM ILCP-derived progenies. The Thy1+NKp46− subset derived from lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs were mostly ICOS+, with very few ICOS− cells. The ICOS+ cells likely included ILC2s, whereas the ICOS− cells were likely undifferentiated progenitors. The Thy1+NKp46+ subset possibly included ILC1s and ILC3s, and Thy1−NKp46+ were likely NK cells. To further test the ILC3 potential of lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs, we purified these cells from Rorc(γt)-EGFP+/− mice and performed the same in vitro differentiation cultures. The lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs gave rise to Thy1+NKp46+Rorc(γt)-EGFP+ ILC3s (Fig. 4 E). These results showed that lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs are similar to BM ILCPs and have the capacity to differentiate into multiple ILC lineages. Hence, we will call them lung ILCPs hereafter.

Lung ILCPs are found in Rag1−/− mouse lungs

To further confirm that lung IL-18Rα+ ILCPs described above belong to the ILC lineage, we analyzed Rag1−/− mice. The Lin−T-bet−Thy1+CD127+RORγt−IL-18Rα+ST2− cells with intermediate expression of GATA-3 and CD25 were also found in Rag1−/− mouse lungs (Fig. 5, A and B). Similar to the IL-18Rα+ cells from Rorα-YFP mice, they produced very small amounts of IL-5, IL-2, IL-4, IL-17, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β (Fig. 5 C). They also expanded after intranasal IL-18 and papain treatments (Fig. 5 D) and were negative for intracellular IL-5/IL-13 (Fig. 5 E).

Figure 5.

IL-18Rα+ ILCs with similar properties are found in Rag1−/− mouse lungs. (A) Lin−Tbet−Thy1+CD127+RORγt− cells in adult Rag1−/− mouse lungs were sequentially gated and divided into IL-18Rα+ST2− (green) and IL-18Rα−ST2+ (black) subsets. (B) Expression of GATA-3 and CD25 by lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs (green) and ST2+ ILC2s (black) in A as well as lung NK cells (NKp46+Eomes+Tbet+; filled gray) is shown. (C) Lin−Thy1+CD127+ cells from Rag1−/− mouse lungs were sorted into IL-18Rα+ ILCs (green) and ST2+ ILC2s (black) and stimulated for 72 h with PMA and ionomycin. The amounts of cytokines and chemokines in the culture supernatants were determined. (D) Absolute numbers of IL-18Rα+ ILCs (green) and ST2+ ILC2s (black) gated as in A in naive, IL-18, and papain-treated lungs are shown in bar graphs. (E) Lin−Thy1+CD127+IL-18Rα+ ILCs (green) and ST2+ ILC2s (black) were analyzed for intracellular IL-5 and IL-13 expression in naive, IL-18, and papain-treated lungs. Data are representative of five or more independent experiments with four or more mice per group in each experiment (mean ± SEM). **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

We purified lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs and BM ILCPs from papain-treated Rag1−/− mice (CD45.2) and transplanted into irradiated Pep3b mice. Lin−T-bet−Thy1+CD127+Rorγt− cells in the recipient mouse lungs were gated and analyzed for IL-18Rα and ST2 expression (Fig. 6 A). Donor-derived cells were found among the ST2+ ILC2s. We also analyzed the livers of the recipient mice. Lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs generated T-bet+Eomes− ILC1s and a very small number of Eomes+ NK cells (Fig. 6 B). Lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs and BM ILCPs generated comparable numbers of ILC2s and ILC1s (Fig. 6 C). However, lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs generated significantly fewer NK cells.

Figure 6.

IL-18Rα+ ILCs in adult Rag1−/− mouse lungs have ILCP properties. BM ILCPs or lung Lin−Thy1+CD127+IL-18Rα+ST2− cells were purified from papain-treated Rag1−/− mice (CD45.2) and injected (4,000 cells per mouse) intravenously into lethally irradiated Pep3b mice. The tissues of the recipient mice were analyzed 6 wk after transplantation. (A) Lung Lin−T-bet−Thy1+CD127+Rorγt− cells were sequentially gated, and IL-18Rα+ and ST2+ subsets were analyzed for donor-derived CD45.1−CD45.2+ cells. (B) Liver T-bet+Eomes− and T-bet+Eomes+ cells were gated for donor-derived ILC1s and NK cells. (C) Absolute numbers of donor-derived lung ILC2s, liver ILC1s, and NK cells. (D) BM ILCPs or lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs were purified as in A, and 1,000 cells each were cultured as in Fig. 4 D. The progenies were analyzed for Thy1 and NKp46 expression. Thy1+NKp46− cells were further analyzed for ICOS expression. Frequencies of the indicated subsets are shown in pie charts. (E) Lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs were cultured without or with IL-18 cultured as in Fig. 4 D. The Thy1+NKp46− cells were further analyzed for ST2 expression. The absolute numbers of the indicated subsets in each condition are shown in bar graphs. Data in A–C are representative of four or more independent experiments with four or more mice per group in each experiment, data in D are representative of ≥15 replicates per experimental group in two independent experiments, and data in E are representative of five or more replicates per experimental group in one experiment (mean ± SEM). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01 by two-tailed Student’s t test. ns, not significant.

We also tested in vitro differentiation of BM ILCPs and lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs from papain-treated Rag1−/− mice. In agreement with results obtained with Rorα-YFP mice, the Thy1+NKp46− subset derived from BM ILCPs included ICOS+ and ICOS− cells (Fig. 6 D), and these ICOS− cells constituted >90% of the progenies. The Thy1+NKp46− subset derived from lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs were mostly ICOS+, with some ICOS− cells. More than half of the Thy1+NKp46− cells derived from lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs were ST2+ (Fig. 6 E, top). When IL-18 was added to the culture, it increased the proliferation and differentiation of lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs. These results indicated that the Rag1−/− mouse lung IL-18Rα+ ILCs were comparable to the Rorα-YFP mouse lung ILCPs.

Identification of two activated ILC2 subsets in neonatal RORα-YFP mouse lungs by scRNA-seq analysis

Lung ILC2s vigorously develop in the neonatal period and become activated due to the spontaneous release of IL-33 from epithelium (de Kleer et al., 2016; Saluzzo et al., 2017; Steer et al., 2017). To analyze the development and complexity of neonatal lung ILC2s, we analyzed all CD45lo/+Linlo lung cells (Fig. 7 A) from neonatal (12-d-old) RORα-YFP mice by scRNA-seq. Unsupervised clustering revealed 17 distinct clusters, including B, NK, and T cells and ILC2s (Fig. 7, B and C; and Table S2). The ILC2 clusters were identified by their differential expression of ILC2-associated genes, including Arg1, Il13, Areg, Gata3, and Il1rl1. The ILC2 clusters were also evident on the t-SNE plot based on their expression of Rora, Gata3, Il7r, Il1rl1, Areg, Arg1, Il5, and Il13 (Fig. S3 A). We isolated and combined the ILC2 clusters and removed any potential remaining contaminating cells as indicated previously. We then analyzed differentially expressed genes by neonatal and naive adult ILC2s. Consistent with previous reports (de Kleer et al., 2016; Saluzzo et al., 2017; Steer et al., 2017), our analysis confirmed that neonatal ILC2s have an activated profile with higher expression of Arg1, Il13, Il5, and Klrg1 than adult ILC2s (Fig. S3 B).

Figure 7.

scRNA-seq analysis identifies two distinct ILC2 subsets in neonatal mouse lungs. (A) Gating strategy for purification of Linlo cells from 12-d-old neonatal RORα-YFP mouse lungs for scRNA-seq analysis. (B) t-SNE plot shows distinct clusters within the 21,256 sequenced cells. (C) Heatmap of the differentially expressed genes by the clusters from B. Top 10 differentially expressed transcripts of the lymphoid lineages are shown. (D) The ILC2 clusters from B were combined and subjected to further unsupervised clustering, which divided the 600 ILC2s into subset 1 (293 cells) and subset 2 (307 cells). Heatmap shows top 20 genes that are differentially expressed by the subsets 1 and 2. The arrows point to the genes that are mentioned in the text. (E) Heatmap shows the expression our selection of ILC(2)-associated genes by the subsets 1 and 2. The differentially expressed genes are shown by red (higher expression on subset 1) and purple (higher expression on subset 2) boxes. The rest of the genes are similarly expressed by the two subsets.

Figure S3.

Gene expression analysis of neonatal ILC2s. (A) t-SNE plots showing expression of the indicated individual genes. (B) Heatmap shows the top genes that are differentially expressed (P ≤ 0.05) by adult (combined ILC2 subsets from Fig. 2 D) and neonatal ILC2s (combined ILC2 subsets from Fig. 7 D). The arrows point to the activation-associated genes Arg1, Il13, Il5, and Klrg1.

Table S2. Top 20 genes differentially expressed by the 16 clusters in the neonatal dataset.

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Cluster 6 | Cluster 7 | Cluster 8 | Cluster 9 | Cluster 10 | Cluster 11 | Cluster 12 | Cluster 13 | Cluster 14 | Cluster 15 | Cluster 16 | Cluster 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Igkc | Tyrobp | S100a4 | Spry2 | Gzma | Eln | S100a4 | 2810417H13Rik | Cd3d | Hbb-bs | Ifitm1 | Sftpa1 | Bst2 | Car1 | Cldn5 | Fscn1 | Dcn |

| Cd74 | Nkg7 | Arg1 | Pim1 | Klrd1 | Aspn | Arg1 | Hmgb2 | Cd3e | Hba-a1 | Ccl6 | Lyz2 | Cox6a2 | Vamp5 | Egfl7 | Zmynd15 | Igfbp6 |

| Cd79a | Klrd1 | S100a6 | Actb | Nkg7 | Sparc | Rgcc | Stmn1 | Cd8b1 | Hba-a2 | Ccl3 | Sftpb | Siglech | Gm15915 | Ramp2 | Il12b | Upk3b |

| Ly6d | Ccl5 | Ramp1 | Kdm6b | Tyrobp | Bgn | Samsn1 | Tuba1b | Trac | Hbb-bt | Ccl9 | S100g | Smim5 | Clec4d | Gng11 | Cxcl16 | Aebp1 |

| Ms4a1 | Igkc | Il13 | Notch2 | Fcer1g | Col3a1 | Ltb4r1 | Birc5 | Trbc2 | Alas2 | Alox5ap | Wfdc2 | Ccr9 | Gstm5 | Tmem100 | Cacnb3 | Gpc3 |

| Ebf1 | Gzma | Gata3 | Abhd2 | AW112010 | Mustn1 | Gata3 | Ube2c | Cd3g | Snca | Mcpt8 | Ager | Lair1 | Aqp1 | Sdpr | Basp1 | Nkain4 |

| Cd79b | Fcer1g | Samsn1 | Pdcd4 | Ccl5 | Cyr61 | S100a6 | Tubb5 | Ms4a6b | Ube2l6 | Hdc | Sftpd | Plaur | Tspo2 | Ecscr | Tm4sf5 | Mgp |

| Vpreb3 | Ly6d | Rgcc | Cbx3 | Klrk1 | Tgfbi | Cxcl2 | Cks1b | Lef1 | Bpgm | Il6 | Cxcl15 | Runx2 | Gata2 | Tm4sf1 | Marcks | Rarres2 |

| Iglc1 | AW112010 | Ltb4r1 | Wtap | Cd7 | Serpine2 | Il1rl1 | Top2a | Ifi27l2a | Fam46c | Lilr4b | Cldn18 | Tcf4 | Apoe | Scn7a | Cd83 | Meg3 |

| Ighm | Klrk1 | Rgs1 | Insig1 | Klre1 | Tagln | Ramp1 | Hmgn2 | Ms4a4b | Mkrn1 | Osm | Cbr2 | Alox5ap | Cox6b2 | S100a16 | Ccr7 | Apoe |

| Iglc3 | Ebf1 | Klrg1 | Slc39a1 | Ctsw | Col1a2 | Rora | Rrm2 | Gm8369 | Slc25a37 | Cyp11a1 | Krt18 | Grn | Cdk6 | Cdh5 | Net1 | Col1a1 |

| Iglc2 | Xcl1 | Stab2 | B4galt1 | Il18r1 | Col1a1 | Areg | H2afx | Tcf7 | Gpx1 | Csf2rb | Sfta2 | Ly6c2 | Khk | Hpgd | Cd63 | Sparc |

| H2-Ab1 | Serpinb6b | Areg | Kmt2d | Ms4a4b | Fstl1 | Gadd45b | H2afz | Ikzf2 | Bnip3l | Csrp3 | Chil1 | Rnase6 | Myb | Stmn2 | Traf1 | Igfbp5 |

| Cd24a | Ctsw | Rora | Zc3hav1 | Xcl1 | Serpinh1 | Klrg1 | Cenpa | Lck | Lilrb4a | Cldn3 | Plac8 | Ifitm2 | Cav1 | Gclc | Col3a1 | |

| Cd72 | Klre1 | Cxcl2 | Pan3 | Serpinb6b | Pam | Nfkb1 | Cdca3 | Trbc1 | Cd200r3 | Anxa3 | Irf8 | Mt1 | Calcrl | Epsti1 | Serpinh1 | |

| Spib | Iglc2 | Furin | Alkbh5 | Sh2d1a | Fos | Hilpda | Ccnb2 | Lat | Ier3 | Lmo7 | Pld4 | Atpif1 | Cd36 | Cst3 | Col1a2 | |

| Siglecg | Ifng | Ccl1 | Supt16 | Gimap4 | Mfap4 | Klk8 | Smc2 | Gimap3 | Ccl4 | Bex4 | Ctsh | Gpx1 | Crip2 | Npc2 | Ifitm3 | |

| H2-Eb1 | Cd7 | Ctla2a | Rpgrip1 | Ncr1 | Mfap2 | Fam110a | Cenpf | Gimap4 | Cd63 | Emp2 | Ctsb | Stmn1 | Ifitm3 | Klf6 | Csrp2 | |

| H2-Aa | Gimap4 | Hilpda | Ppp1r16b | Car2 | Id3 | Rgs1 | Mki67 | Rgs10 | Ifitm2 | Sftpc | Tyrobp | Plac8 | Ifitm2 | Serpinb6b | Fabp5 | |

| Mzb1 | Ccl4 | Gadd45b | Furin | Ifng | Thbs1 | Il13 | Dut | Bcl2 | Apoe | Npc2 | Psap | Nop10 | Sepp1 | Ccl5 | Gsn |

The table shows the top 20 genes that are highly expressed (P ≤ 0.01) by each cluster in Fig. 7, B and C. The genes were selected by the FindMarkers function in the Seurat package.

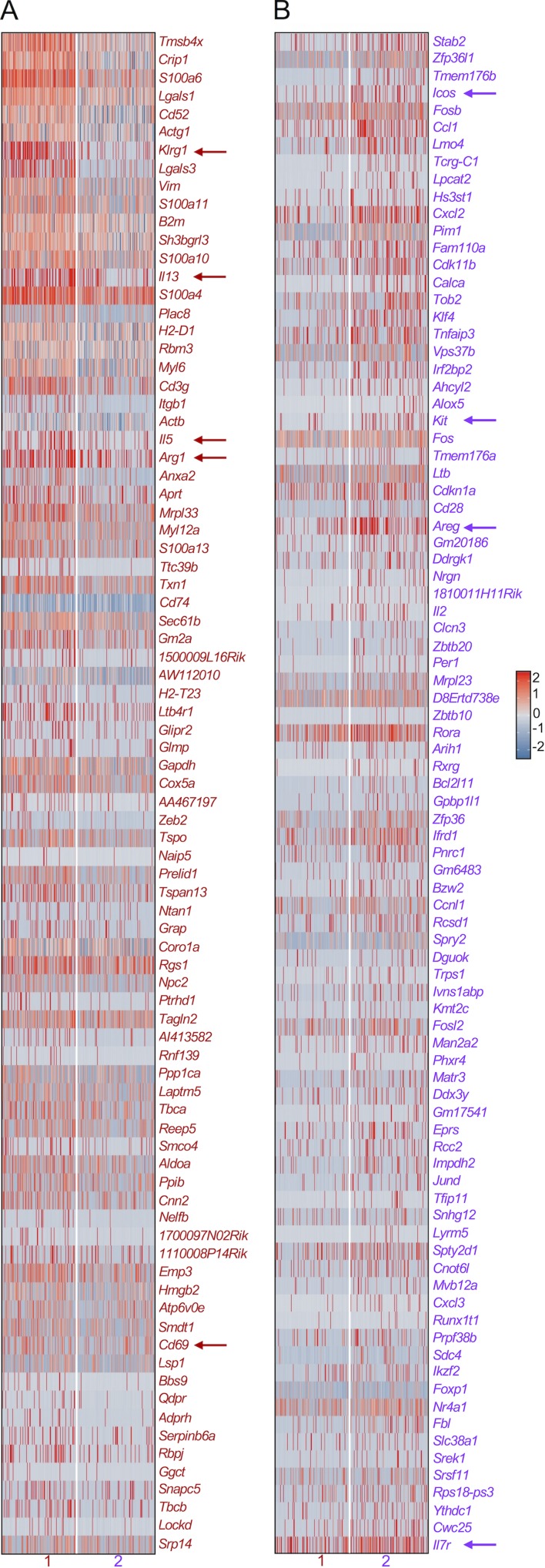

Further unsupervised clustering of the neonatal ILC2s divided them into two subsets (1 and 2), each expressing a distinct set of genes (Fig. 7 D). Subset 1 mainly included ILC2s with high expression of Il5, Il13, Arg1, and Klrg1, whereas subset 2 was highly enriched in Areg- and Icos-expressing ILC2s. A complete analysis of the transcripts that were differentially expressed between these two subsets indicated that the Il5/Il13–expressing subset also had slightly higher expression of the activation marker Cd69 (Fig. S4 A), whereas the Areg/Icos–expressing subset had slightly higher expression of Il7r and Kit (Fig. S4 B). The two subsets equally expressed Id2, Gata3, Thy1, and Il1rl1 (Fig. 7 E).

Figure S4.

Differential gene expression analysis of the neonatal lung ILC2 subsets. (A and B) Heatmap shows all the genes that are differentially expressed (P ≤ 0.05) by neonatal ILC2 subsets. Genes that have higher expression in subset 1 than subset 2 (A), as well as genes that have higher expression in subset 2 than subset 1 (B), are shown. The arrows point to the genes that are mentioned in the text.

Trajectory analysis revealed ILCPs and confirmed two activated ILC2 subsets in neonatal lungs

To examine the developmental relationship between the two activated neonatal ILC2 subsets above, individual neonatal ILC2s were positioned along a differentiation trajectory according to the virtual progression of their transcriptome (Fig. 8 A; Trapnell et al., 2014; Trapnell, 2015). This analysis placed individual ILC2s into five different states. State 1 was enriched for cells expressing ILCP-associated genes, including Il7r, Kit, Tcf7 (Yang et al., 2015; De Obaldia and Bhandoola, 2015), Tox (Seehus et al., 2015), and Zbtb16 (Constantinides et al., 2014), and low expression of the mature ILC2-associated genes, including Il1rl1, Areg, Il5, Il13, Arg1, and Klrg1 (Fig. 8, A and B; and Fig. S5, A and B), suggesting that these cells might be ILCPs in neonatal lungs. Analyses of the genes differentially expressed along cell fate progression from state 1 to states 4 and 5 revealed progressive down-regulation of the ILCP-associated genes Tcf7 (Yang et al., 2015), Tox (Seehus et al., 2015), and Runx3 (Ebihara et al., 2015) as well as Il18r1 (Figs. 8 C and S5 C). Mature ILC2-associated genes Il1rl1, Areg, Arg1, Il5, Il13, and Klrg1 showed up-regulation along their cell fate progression. State 1 progenitor cells appeared to differentiate into two distinct ILC2 effector subsets (states 4 and 5; Fig. 8, A and B; and Fig. S5, A and B). State 4 was enriched for cells expressing Il5, Il13, Arg1, and Klrg1, whereas state 5 was enriched for cells expressing Areg and Icos. State 2 seemed to be a transitional state connecting progenitors to the mature cells in states 4 and 5. State 3 did not have any distinctive features compared with states 4 and 5 (Fig. S5 A). These results suggested that ILCPs exist in the neonatal lung and gradually differentiate into two alternative effector fates, namely Il5/Il13/Klrg1–expressing proinflammatory and Areg/Icos–expressing tissue-repairing ILC2s.

Figure 8.

Trajectory analysis of scRNA-seq neonatal lung ILC2s identifies effector ILC2 subsets and ILC progenitor-like cells in the neonatal lung. (A) A single-cell trajectory was constructed from the neonatal ILC2 dataset in Fig. 4 D using the Monocle package, and neonatal ILC2s were ordered in pseudotime along a tree-like differentiation trajectory. Five distinct segments or states of the trajectory were identified. (B) Heatmap of the expression of ILC2-associated genes in the indicated states in A. (C) Changes in the expression of the indicated ILC2-associated genes along cell fate progression in pseudotime, from state 1 to states 4 and 5 in A. (D) The cells from states 1, 4, and 5 were combined and subjected to further unsupervised clustering using Seurat package, which divided them into three distinct subsets, namely ILCP (95 cells), proinflammatory (175 cells), and tissue-repairing (247 cells) ILC2 subsets. Heatmap shows top 20 genes that are differentially expressed by the subsets. The arrows point to the genes that are mentioned in the text.

Figure S5.

Differential gene expression analysis of the neonatal lung ILC2 states defined by trajectory analysis. (A) Heatmap of the expression of ILC2-associated genes in the indicated states. (B) Heatmap shows the genes that are differentially expressed (P ≤ 0.01) among the indicated states. (C) Changes in the expression of the indicated genes along cell fate progression in pseudotime, from state 1 to states 4 and 5. (D) Heatmap shows the expression our selection of ILC(2)-associated genes by neonatal ILCPs and proinflammatory and tissue-repairing ILC2s in Fig. 8 D. The differentially expressed genes are shown in green (higher expression on ILCPs), red (higher expression on proinflammatory ILC2s), and purple (higher expression on tissue-repairing ILC2s) boxes. The rest of the genes are similarly expressed by the two subsets.

To transcriptionally compare neonatal ILCP and effector ILC2 subsets, we isolated and combined the cells within the specific states 1, 4, and 5 (Fig. 8, A and B; and Fig. S5, A and B). We then subjected these cells to unsupervised clustering using Seurat package. In agreement with our trajectory analysis, the cells were divided into three distinct subsets (Fig. 8 D). The first subset had an ILCP signature with high expression of Tcf7, Il18r1, Kit, and Runx3. The other two subsets included Il5/Il13/Arg1/Klrg1–expressing proinflammatory and Areg/Icos–expressing tissue-repairing ILC2s. It is notable that all three subsets lacked expression of Tbx21 and Rorc, excluding the possibility of them being NK/ILC1s or ILC3s (Fig. S5 D).

ILCPs are found in neonatal mouse lungs

The scRNA-seq analyses above suggested that a population of Tcf7-expressing ILCPs can be found in neonatal lungs. To further study neonatal lung ILCPs, we performed flow cytometric analyses of neonatal (12-d-old) lungs and adult BM as well as neonatal BM of Tcf7EGFP mice (Fig. 9 A). Lin−Thy1+CD127+ cells were divided into two subsets based on the expression of ST2. ST2− cells highly expressed Tcf7EGFP and included IL-18Rα+Kit+ cells. ST2+ ILC2s were Tcf7EGFP negative and mostly IL-18Rα negative. In the adult BM, ILCPs (Lin−Thy1+CD127+Tcf7EGFP+ST2−) were mostly IL-18Rα and Kit positive. In contrast, ST2+ ILC2Ps were Tcf7EGFP−IL-18Rα−Kit−. In the neonatal BM, only very small numbers of Lin−Thy1+CD127+ cells were found. These results showed that neonatal lung ILCPs are similar to BM ILCPs. In addition, neonatal lung ILCPs seemed very similar to the adult lung ILCPs described above in their expression of Tcf7EGFP, IL-18Rα, and Kit. To test the progenitor capacity of these neonatal lung ILCPs, we cultured them on OP9 with IL-7 and SCF. BM ILCPs were used as control. After 1 wk, both populations generated two distinct subsets based on ICOS and NK1.1 expression (Fig. 9 B). ICOS+ cells most likely include ILC2s, whereas NK1.1+ cells might include NK cells/ILC1s/ILC3s. These results indicated that neonatal lung ILCPs have the capacity to differentiate into multiple ILC lineages, similar to adult lung ILCPs.

Figure 9.

ILCPs are found in neonatal mouse lungs. (A) Lin−Thy1+CD127+ cells from neonatal (12-d-old) lung, adult, and neonatal (12-d-old) BM from Tcf7EGFP mice were sequentially gated and divided into Tcf7EGFP+ST2− (green) and Tcf7EGFP−ST2+ (black) subsets and analyzed for the expression of IL-18Rα and Kit. (B) BM ILCPs defined by Lin−Thy1+CD127+Tcf7EGFP+ST2− (IL-18Rα+Kit+) and lung ILCPs defined by Lin−Thy1+CD127+Tcf7EGFP+ST2−IL-18Rα+Kit+ were cultured on OP9 with IL-7 and SCF for 1 wk. The progenies were analyzed for ICOS and NK1.1 expression, and the frequencies of the indicated subsets are shown in pie charts. Data in A are representative of two independent experiments with two or more mice per group in each experiment, and data in B are representative of three replicates per experimental group in one experiment.

Distinct effector ILC2 subsets in neonatal mouse lungs

The scRNA-seq analyses above showed two subsets of activated ILC2s with equal expression of Il1rl1 and Thy1. The two subsets differentially expressed Klrg1 and Icos. Accordingly, we could divide the neonatal B6 lung ILC2s (Lin−ST2+Thy1+CD127+) into two subsets based on the expression of KLRG1 and ICOS by flow cytometry (Fig. 10 A). In agreement with their gene expression profile (Fig. S4 B), the KLRG1−ICOS+ subset had slightly higher expression of CD127. We purified the neonatal KLRG1+ICOS− and KLRG1−ICOS+ subsets as well as KLRG1+ICOS+ and KLRG1−ICOS− cells and stimulated them in vitro using a combination of IL-33 and IL-7 (Fig. 10 B). After the indicated time points, the KLRG1+ICOS− cells produced much higher amounts of IL-5 and IL-13 compared with other subsets and minimally produced amphiregulin. The KLRG1−ICOS+ cells produced the highest amount of amphiregulin and did not produce much IL-5 and IL-13. These findings indicated that KLRG1 and ICOS expression distinguishes two functionally distinct effector subsets of neonatal ILC2s, namely IL-5/IL-13 cytokine-producing and amphiregulin-producing ILC2s. To determine whether IL-33, which is spontaneously released in neonatal mouse lungs (de Kleer et al., 2016; Saluzzo et al., 2017; Steer et al., 2017), is driving the divergence of these two effector subsets, we analyzed Il33−/− mouse lungs. Neonatal mouse lung KLRG1+ ILC2s were substantially reduced in these mice (Fig. 10 C), indicating that this subset is dependent on IL-33 signaling. However, ICOS+ ILC2s were not affected and are presumably driven by other factors. In naive adult mouse lungs, ILC2s had low expression of KLRG1 and ICOS and up-regulated both after papain treatments. Unlike neonatal ILC2s, the divergence between KLRG1 and ICOS was not clear. However, adult papain-induced KLRG1+ ILC2s were also substantially reduced in Il33−/− mice, whereas the ICOS+ ILC2s were unaffected. These results suggested that the two subsets of ILC2s in neonatal lungs are activation-induced effector cells with distinct functions. The KLRG1+ subset is induced by IL-33, whereas the activation signal that induces ICOS+ subset remains to be elucidated.

Figure 10.

Flow cytometric and functional analysis shows distinct effector ILC2 subsets in neonatal mouse lungs. (A) Lin−ST2+Thy1+CD127+ ILC2s from 12-d-old B6 mouse lungs were analyzed for KLRG1 and ICOS expression. The expression of ST2 and CD127 by the KLRG1+ICOS− (red) and KLRG1−ICOS+ (purple) subsets were overlapped in dot plot. (B) Neonatal ILC2s were divided into four subsets based on KLRG1 and ICOS expression, purified, and cultured for the indicated number of hours with IL-33 and IL-7 (1 ng/ml each for cytokine and 10 ng/ml for amphiregulin analysis). The amounts of IL-5, IL-13, and amphiregulin in the culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. (C) ILC2s from neonatal, naive, and papain-treated WT and Il33−/− mouse lungs were analyzed for KLRG1 and ICOS expression. The frequencies of KLRG1+, ICOS+, and KLRG1−ICOS− subsets are shown in bar graphs. Data are representative of three to five independent experiments with ≥12 mice per group (mean ± SEM). *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001 by two-tailed Student’s t test.

Discussion

In this study, we generated a lineage tracer mouse model that marks ILCs with YFP, based on the expression of RORα. By scRNA-seq and flow cytometry, we found Lin−T-bet−YFP+CD127+Thy1+RORγt−IL-18Rα+ST2− cells in adult lungs with intermediate GATA-3 expression. These cells expressed Tcf7 and Kit in Tcf7EGFP mice. The IL-18Rα+ population was also found in Rag1−/− mice, confirming that it belongs to the ILC lineage. Unlike conventional ILC2s, IL-18Rα+ cells were CD25loGITRlo. They were also KLRG1loIL-25Rlo, excluding the possibility of them being inflammatory ILC2s (Huang et al., 2015, 2018). Similar to BM ILCPs (Halim et al., 2012b), lung IL-18Rα+ cells produced small amounts of ILC2-associated cytokines. Interestingly, they proliferated after intranasal administration of IL-18 or papain but did not express IL-5 or IL-13. These cells could differentiate into multiple ILC lineages in transplanted mice and in vitro differentiation cultures. Also, their proliferation in culture was enhanced in the presence of IL-18. Therefore, lung IL-18Rα+ cells are likely IL-18 responsive ILCPs. Our analysis of neonatal mice also revealed Tcf7-expressing ILCPs, which expressed IL-18Rα and Kit similar to adult lung ILCPs. Lung ILCPs are similar to BM ILCPs, as they are Lin−Thy1+CD127+Tcf7EGFP+ST2−IL-18Rα+Kit+. Lung ILCPs were more frequent in neonatal lungs than BM, suggesting that neonatal lung tissue might provide an important niche for the development of lung ILC2s. The lung ILCPs in our study are similar to systemic human ILC precursors, as they both expressed the ILCP-associated transcription factor genes Tcf7 and Runx3 as well as Cd2, Cd7, and Il18r1 (Lim et al., 2017). The expression of IL-18Rα by ILCPs may be functionally important, as it enables them to sense IL-18 induced by tissue inflammation. It has also been reported that hematopoietic stem cells, common lymphoid progenitors, and early thymic progenitors express IL-18Rα (Gandhapudi et al., 2015). IL-18 plus IL-7 promotes the expansion of hematopoietic stem cells and common lymphoid progenitors, and IL-18 alone can promote differentiation of early thymic progenitors into double-negative stage 3 in vitro.

The IL-18Rα+ cells in our study are very similar to the lung ST2−IL-18Rα+Il5+ cells reported previously (Ricardo-Gonzalez et al., 2018), which were considered functionally similar to skin ILC2s. However, lung IL-18Rα+ST2− cells significantly differ from skin IL-18Rα+ST2− ILC2s in their response to IL-18. The former proliferated but did not produce type 2 cytokines upon IL-18 stimulation, whereas the latter produced these cytokines. It should also be noted that the use of the RORα lineage tracer mice in our study, unlike the Il5 reporter mice, enabled us to capture all IL-18Rα+ ILCs in the lung regardless of their basal activation status.

Our analysis of neonatal mice also revealed two distinct ILC2 subsets differing in their gene expression profiles: Klrg1/Il5/Il13– and Icos/Areg–expressing subsets. Accordingly, we could divide neonatal ILC2s into two functionally distinct effector subsets based on the expression of KLRG1 and ICOS. The KLRG1+ subset produced large amounts of IL-5 and IL-13, but not amphiregulin, whereas the ICOS+ subset produced higher amounts of amphiregulin and lower amounts of IL-5 and IL-13 compared with the KLRG1+ subset. Considering that neonatal ILC2s are activated by the spontaneous release of IL-33 during this period (de Kleer et al., 2016; Steer et al., 2017; Saluzzo et al., 2017), these results suggested that activated ILC2s diverge into two distinct effector fates of proinflammatory IL-5/IL-13 producer and tissue-repairing amphiregulin-producer ILC2s. Our analysis of the Il33−/− mice showed that the KLRG1+ cytokine-producing ILC2s are dependent on IL-33 for their differentiation, but not the ICOS+ amphiregulin-producing ILC2s. Intranasal papain treatment of adult mice induced up-regulation of both KLRG1 and ICOS on lung ILC2s, but the divergence between the two subsets was less clear. It has been reported that some degree of heterogeneity exists in adult lung ILC2s with regard to cytokine and amphiregulin production after intraperitoneal IL-33 injections (Monticelli et al., 2015). However, the phenotypic properties of the proinflammatory cytokine-producing ILC2s versus amphiregulin-producing ones in adulthood remain to be elucidated.

The putative proinflammatory KLRG1+ ILC2s have high expression of Arg1 encoding arginase-1 (Arg1), which is required for the cytokine production by ILC2s (Monticelli et al., 2016). KLRG1, an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif–bearing inhibitory receptor for E-cadherin, is a marker for highly activated ILC2s and acts as an immune checkpoint (Chiossone and Vivier, 2017; Taylor et al., 2017). On the other hand, the putative tissue-repairing ILC2s have high expression of ICOS. The ICOS–ligand interaction promotes survival and cytokine production of adult ILC2s after intranasal IL-33 administration (Maazi et al., 2015). In our study, ICOS is specifically expressed by amphiregulin-producing neonatal ILC2s. The tissue-repairing ILC2s have high expression of Tnfaip3, Per1, and Irf2bp2. Tnfaip3 and Per1 encode ubiquitin-modifying enzyme A20 and period circadian regulator 1, respectively, which are known to inhibit NF-κB (Matmati et al., 2011; Sugimoto et al., 2014). Irf2bp2 encodes interferon regulatory factor 2–binding protein 2, which inhibits NFAT signaling and also acts as an activator of vascular endothelial growth factor A expression in muscle cells (Teng et al., 2010; Carneiro et al., 2011). Therefore, the high expression of these genes suggests that NF-κB and NFAT signaling and cytokine production might be actively inhibited in amphiregulin-producing ILC2s. The tissue-repairing ILC2s also had high expression of Stab2 encoding stabilin-2. The scavenger receptor stabilin-2 binds to hyaluronic acid and other glycosaminoglycans (Harris et al., 2007; Schledzewski et al., 2011; Harris and Weigel, 2008), which are up-regulated in the extracellular matrix during inflammation, and has to be taken up and degraded before the original matrix can be restored. The role of stabilin-2 in promoting the tissue-repairing phenotype and function of tissue-repairing ILC2s remains to be elucidated.

ILC2s are mostly generated during the postnatal period and persist into adulthood (Schneider et al., 2019; Ghaedi et al., 2016; Gasteiger et al., 2015). We have identified an ILCP population in the neonatal mouse lungs that has higher frequencies compared with neonatal BM, suggesting that neonatal lung ILCPs might be a major source of lung ILC2s. Our scRNA-seq analysis suggested that neonatal lung ILC2s, derived from lung ILCPs, diverged into distinct proinflammatory and tissue-repairing fates upon activation. We believe that the two effector ILC2 subsets are induced by activation partly due to the spontaneous release of IL-33 in neonatal lungs (de Kleer et al., 2016; Saluzzo et al., 2017; Steer et al., 2017). As naive adult mouse lung ILC2s are not activated and are KLRG1loICOSlo, it is unclear whether a particular subset (e.g., KLRG1+, ICOS+, or KLRG1−ICOS−) of neonatal ILC2s preferentially persists into adulthood. Lung ILCPs also exist in a low frequency in adult mice, and their contribution to ILC-poiesis in steady state is most likely limited. However, under inflammatory conditions, these lung ILCPs likely expand by inflammation-induced IL-18 and might actively contribute to the generation of ILCs.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6), B6.Rag1−/−, and albino B6 breeder mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. B6.Il33+/− mice were purchased from KOMP. RORα-IRES-Cre mice were rederived by in vitro fertilization of albino C57BL6 mouse eggs with sperm from RORα-IRES-Cre mice (Chou et al., 2013) obtained from the Salk Institute for Biological Studies (La Jolla, CA). RORα-YFP mice were generated by crossing RORα-IRES-Cre (Chou et al., 2013) mice with B6.129X1-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(EYFP)Cos/J from Jackson Laboratory. The mice were backcrossed three times to B6 background. All mice were maintained in the British Columbia Cancer Research Centre animal facility under specific pathogen–free conditions. The use of these mice was approved by the animal committee of the University of British Columbia and in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. B6.Tcf7EGFP mice (Yang et al., 2015) were kept in a National Institutes of Health animal facility, and their use was approved by the relevant National Institutes of Health animal care and use committees. For WT controls, the pups from C57BL/6 (B6) breeding colonies were used with the exception of B6.Il33−/− mice, for which WT littermates were used. Adult mice 4–10 wk of age and 12-d-old neonatal mice of both sexes were used.

Primary leukocyte preparation

Lung tissue was minced and fragments were digested in 5 ml DMEM containing collagenase IV (142.5 U/ml; 17104019; Thermo Fisher) and DNase I (118,050 U/ml, 9003–98-9; Sigma-Aldrich) for 25 min at 37°C on a shaker (150 rpm). The single-cell suspension was filtered through a 70-µm cell strainer and washed once with 5 ml DMEM containing 10% FBS, penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml), and 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. Leukocytes were enriched by centrifugation (10 min, 650 ×g) on a 36% Percoll gradient (P4937; Sigma-Aldrich), and RBCs were lysed by ammonium chloride solution. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from small intestine in the same way.

For BM cells, tibia, femur, and pelvic bones were crushed in 10 ml PBS containing 2% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml), and the single-cell suspension was filtered through a 70-µm cell strainer and washed once with 5 ml of the same media. This was followed by RBC lysis by ammonium chloride. Liver tissues were processed as indicated previously (Romera-Hernández et al., 2019).

Antibodies and flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were incubated with anti-mouse CD16/32 antibody (clone 2.4G2). eFluor 450–conjugated Lin-antibody cocktail contained anti-CD3e (145-2C11; RRID: AB_10735092), TCRαβ (H57-597; AB_11039532), TCRγδ (GL3; AB_2574071), NKp46 (29A1.4; AB_10557245), CD19 (1D3; AB_2734905), CD11b (M1/70; AB_1582236), CD11c (N418; AB_1548654), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5; AB_1548788), and Ter119 (TER-119; AB_1518808). For BM, anti-CD45R/B220 (RA3-6B2; AB_1548761) was added to the Lin cocktail. For intestine, anti-NKp46 was removed from the Lin cocktail. For intracellular transcription factor staining, PerCP-eFluor 710-anti-EOMES (Dan11mag; AB_10609215), Pecy7-anti-T-bet (4B10; AB_11042699), eFluor 660- or PE-anti-GATA-3 (TWAJ; AB_10596663 or AB_1963600), PE-anti-ROR gamma (t) (B2D; AB_10805392), and Foxp3/transcription staining buffer set (00–5523-00; Thermo Fisher) were used. The rest of the antibodies used in this study were eFluor 450-anti-NK1.1 (PK136; AB_2043877), V500-anti-CD45 (30-F11; AB_10697046), APC-anti-LPAM-1 (Integrin α4β7; DATK32; AB_10730607), PerCP-eFluor 710- or APC-anti-IL-33R (ST2; RMST2-2; AB_2573883 or AB_2573301), FITC-anti-T1/ST2 (DJ8; AB_947549), PerCP-eFluor 710-anti-CD218a (IL-18Ra; P3TUNYA; AB_2573764), Brilliant Violet 605-anti-CD90.2 (Thy1.2; 53–2.1; AB_11203724), Alexa Fluor 700- or PE or Pecy7-anti-CD127 (A7R34; AB_657611 or AB_465844 or AB_469649), PerCP-eFluor 710-anti-PD-1 (J43; AB_11150055), Brilliant Violet 711-anti-KLRG1 (2F1; AB_2738542), and PE-anti CD278 (ICOS; 7E.17G9; AB_466273).

For the detection of YFP along with intracellular transcription factors from RORα-YFP mouse tissues, single-cell suspensions were stained for cell surface markers and viability dye (65–0865-18; Thermo Fisher), followed by a prefixation step with 0.5% paraformaldehyde, washed with 5 ml PBS containing 2% FBS, and stained for the intranuclear transcription factors per the manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry analysis was performed on a BD Fortessa flow cytometer and FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo 8.7 (Tree Star).

scRNA-seq

Adult and neonatal (12-d-old) RORα-YFP mouse lungs were processed and single cell suspensions were stained with viability dye (65–0865-18; Thermo Fisher), anti-CD45, and Lin-cocktail antibodies as above. Viable CD45lo/+LinloYFP− and YFP+ cells were purified at 2:1 ratio. For the neonatal sample, FITC-anti-CD8 (53–6.7; AB_464915) was added as a Lin antibody. Purified cells were loaded on the Chromium Single Cell Controller (10X Genomics), and libraries were prepared using the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Reagents Kits (v2 chemistry; 10X Genomics), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The obtained libraries were sequenced on a NextSeq 500 (Illumina). Cell Ranger software (v2.0.1; 10X Genomics) was used to perform demultiplexing, alignment, counting as well as initial clustering, and differential gene expression analysis. The reads were aligned to the mm10 genome, with the genome reannotated to include YFP, TCR, and immunoglobulin genes. scRNA-seq analysis was performed using Seurat package (Butler et al., 2018; version 2.1.0) in R (version 3.4.2; R Core Team, 2017). The data were normalized and scaled to remove unwanted sources of variation according to Seurat package criteria. Seurat’s RunPCA function was used to perform linear dimensional reduction, and the first 19 principal components were used for further analysis. For the analysis of only ILC2s, 15 principal components were used for further analysis. Seurat’s FindClusters and RunTSNE functions were used to identify the cell clusters and visualize them. A range of resolutions was tested, and a resolution of 0.6 was used. Before unsupervised clustering of ILC2 barcodes, B cells expressing Cd79a, Cd79b, Ms4a1, Ebf1, or Pax5; NK cells expressing Gzma, Gzmb, Eomes, Ncr1, or Prf1; stromal cells expressing Scgb3a1; T cells coexpressing any TCR genes and Cd4, Cd8a, or Cd5; and NKT cells coexpressing any TCR genes and Klrk1 were filtered out. Seurat’s FindMarkers function was used to find differentially expressed genes among clusters/subsets. The FindMarkers functions were performed two times for adult and neonatal ILC2 subsets, once with only assessing genes that are present in at least 20% of the cells in either of the subsets. The second time, this criterion was removed and all the genes that were differentially expressed between subsets were determined. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to determine the significance of the differential expression. Single-cell trajectory was constructed using the Monocle package (Trapnell et al., 2014; version 2.6.1) in R. State 1 was manually selected as the root of the neonatal ILC2 differentiation trajectory based on the similar gene expression profile of this state to BM ILCPs (Yang et al., 2015; Constantinides et al., 2014; Seehus et al., 2015).

Accession code

The GEO accession number for the scRNA-seq data is GSE122762.

In vivo stimulation

Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation first. Intranasal administrations of recombinant mouse IL-33 (0.25 µg, 580508; BioLegend) or papain (25 µg, 76216; Sigma-Aldrich) in 40 µl PBS were performed on days 0, 1, and 2. Lungs were collected and analyzed on day 5.

Transplantation

B6.Ly5SJL (CD45.1) mice were lethally irradiated with 10 Gy and intravenously transplanted with indicated progenitors. Each irradiated mouse also received ∼5 × 106 helper BM cells from lymphocyte-deficient nonobese diabetic SCID Il2rg−/− (CD45.1) mice. Drinking water was supplemented with ciprofloxacin and hydrochloric acid for the duration of the experiment.

In vitro culture

For each in vitro culture, lung cells were prepared from 12 to 20 mice. ILC2s and other cell populations were sorted by a BD FACSARIA III or FUSION. Purified adult ILC2s (500 cells) were cultured in 200 µl of RPMI1640 containing 10% FBS, penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml), and 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol with PMA (30 ng/ml) and ionomycin (500 ng/ml). Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Cytokine 23-plex Assay (m60009rdpd; Bio-Rad), Bio-Plex 100 instrument, and Bio-Plex Manager 6.0 software (Bio-Rad) were used to determine the respective chemokines and cytokines. Purified neonatal ILC2s (1,000 cells) were cultured in the same way with 1 or 10 ng/ml of IL-33 (580508; BioLegend) and IL-7 (PMC0071; Thermo Fisher) each. IL-5 (AB_2574980), IL-13 (AB_2575028), and amphiregulin (DY989; R&D Systems) ELISA kits were used.

For in vitro culture, 1,000 BM or lung ILCPs were purified and cultured in 24-well plates on confluent OP9-DL1 (Schmitt and Zúñiga-Pflücker, 2002) or OP9 stromal layer in α-MEM containing 20% FBS, penicillin–streptomycin (100 U/ml), 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, SCF (30 ng/ml), and IL-7 (30 ng/ml) ± IL-18 (10 ng/ml) as indicated. CD45+ cells were analyzed after 1 wk.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software). Two-tailed Student’s t or Mann–Whitneyunpaired test was used to determine the statistical significance. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; and ****, P ≤ 0.0001 were considered significant.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows YFP expression in lymphocyte populations in the lung, BM, and intestine from RORα-YFP mice. Fig. S2 shows gene expression profiles of adult lung ILC2 cluster and subsets 1 and 2. Fig. S3 shows gene expression profiles of neonatal ILC2s. Fig. S4 shows differential gene expression analysis of the neonatal lung ILC2s subsets 1 and 2. Fig. S5 shows differential gene expression analysis of the neonatal lung ILC2 states defined by trajectory analysis. Table S1 shows the top 20 highly expressed genes (P ≤ 0.01) by each cluster in the adult dataset in Fig. 2, B and C. Table S2 shows the top 20 highly expressed genes (P ≤ 0.01) by each cluster in the neonatal dataset in Fig. 7, B and C.

Acknowledgments

We thank the BRC-Seq Next Generation Sequencing Core at the Biomedical Research Centre of University of British Columbia, specifically Ryan Vander Werff, for technical support.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grants PJT-153304 and MOP-126194 to F. Takei). M. Ghaedi is a recipient of a University of British Columbia doctoral-affiliated fellowship (Cordula and Gunter Paetzold). I. Martinez-Gonzalez was recipient of Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and Canadian Institutes of Health Research postdoctoral fellowships. X. Lu, A. Das, and A. Bhandoola were supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and Center for Cancer Research.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: M. Ghaedi designed and performed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. Z.Y. Shen designed and performed experiments and bioinformatics analyses of scRNA-seq data. L. Wei and A. Heravi-Moussavi performed bioinformatics analyses of scRNA-seq data. M. Orangi, I. Martinez-Gonzalez, X. Lu, and A. Das designed and performed experiments. M.A. Marra supervised the bioinformatics analysis. A. Bhandoola designed and supervised the research. F. Takei designed and supervised the research and wrote the paper.

References

- Artis D., and Spits H.. 2015. The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 517:293–301. 10.1038/nature14189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando J.K., Nussbaum J.C., Liang H.-E., and Locksley R.M.. 2013. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells constitutively express arginase-I in the naive and inflamed lung. J. Leukoc. Biol. 94:877–884. 10.1189/jlb.0213084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björklund Å.K., Forkel M., Picelli S., Konya V., Theorell J., Friberg D., Sandberg R., and Mjösberg J.. 2016. The heterogeneity of human CD127(+) innate lymphoid cells revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat. Immunol. 17:451–460. 10.1038/ni.3368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A., Hoffman P., Smibert P., Papalexi E., and Satija R.. 2018. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 36:411–420. 10.1038/nbt.4096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro F.R.G., Ramalho-Oliveira R., Mognol G.P., and Viola J.P.B.. 2011. Interferon regulatory factor 2 binding protein 2 is a new NFAT1 partner and represses its transcriptional activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31:2889–2901. 10.1128/MCB.00974-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier M.F., Trabanelli S., Racle J., Salomé B., Cesson V., Gharbi D., Bohner P., Domingos-Pereira S., Dartiguenave F., Fritschi A.S., et al. . 2017. ILC2-modulated T cell-to-MDSC balance is associated with bladder cancer recurrence. J. Clin. Invest. 127:2916–2929. 10.1172/JCI89717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiossone L., and Vivier E.. 2017. Immune Checkpoints on Innate Lymphoid Cells. J. Exp. Med. 214:1561–1563. 10.1084/jem.20170763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou S.-J., Babot Z., Leingärtner A., Studer M., Nakagawa Y., and O’Leary D.D.M.. 2013. Geniculocortical input drives genetic distinctions between primary and higher-order visual areas. Science. 340:1239–1242. 10.1126/science.1232806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinides M.G., McDonald B.D., Verhoef P.A., and Bendelac A.. 2014. A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 508:397–401. 10.1038/nature13047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kleer I.M., Kool M., de Bruijn M.J.W., Willart M., van Moorleghem J., Schuijs M.J., Plantinga M., Beyaert R., Hams E., Fallon P.G., et al. . 2016. Perinatal Activation of the Interleukin-33 Pathway Promotes Type 2 Immunity in the Developing Lung. Immunity. 45:1285–1298. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Obaldia M.E., and Bhandoola A.. 2015. Transcriptional regulation of innate and adaptive lymphocyte lineages. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 33:607–642. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diefenbach A., Colonna M., and Koyasu S.. 2014. Development, differentiation, and diversity of innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 41:354–365. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl G., Colonna M., Di Santo J.P., and McKenzie A.N.J.. 2015. Innate lymphoid cells. Innate lymphoid cells: a new paradigm in immunology. Science. 348:aaa6566 10.1126/science.aaa6566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara T., Song C., Ryu S.H., Plougastel-Douglas B., Yang L., Levanon D., Groner Y., Bern M.D., Stappenbeck T.S., Colonna M., et al. . 2015. Runx3 specifies lineage commitment of innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 16:1124–1133. 10.1038/ni.3272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhapudi S.K., Tan C., Marino J.H., Taylor A.A., Pack C.C., Gaikwad J., Van De Wiele C.J., Wren J.D., and Teague T.K.. 2015. IL-18 acts in synergy with IL-7 to promote ex vivo expansion of T lymphoid progenitor cells. J. Immunol. 194:3820–3828. 10.4049/jimmunol.1301542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger G., Fan X., Dikiy S., Lee S.Y., and Rudensky A.Y.. 2015. Tissue residency of innate lymphoid cells in lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs. Science. 350:981–985. 10.1126/science.aac9593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaedi M., Steer C.A., Martinez-Gonzalez I., Halim T.Y.F., Abraham N., and Takei F.. 2016. Common-Lymphoid-Progenitor-Independent Pathways of Innate and T Lymphocyte Development. Cell Reports. 15:471–480. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gury-BenAri M., Thaiss C.A.A., Serafini N., Winter D.R.R., Giladi A., Lara-Astiaso D., Levy M., Salame T.M.M., Weiner A., David E., et al. . 2016. The Spectrum and Regulatory Landscape of Intestinal Innate Lymphoid Cells Are Shaped by the Microbiome. Cell. 166:1231–1246.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halim T.Y.F., Krauss R.H., Sun A.C., and Takei F.. 2012a Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity. 36:451–463. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halim T.Y.F., MacLaren A., Romanish M.T., Gold M.J., McNagny K.M., and Takei F.. 2012b Retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor alpha is required for natural helper cell development and allergic inflammation. Immunity. 37:463–474. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hams E., Armstrong M.E., Barlow J.L., Saunders S.P., Schwartz C., Cooke G., Fahy R.J., Crotty T.B., Hirani N., Flynn R.J., et al. . 2014. IL-25 and type 2 innate lymphoid cells induce pulmonary fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111:367–372. 10.1073/pnas.1315854111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harly C., Cam M., Kaye J., and Bhandoola A.. 2018. Development and differentiation of early innate lymphoid progenitors. J. Exp. Med. 215:249–262. 10.1084/jem.20170832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris E.N., and Weigel P.H.. 2008. The ligand-binding profile of HARE: hyaluronan and chondroitin sulfates A, C, and D bind to overlapping sites distinct from the sites for heparin, acetylated low-density lipoprotein, dermatan sulfate, and CS-E. Glycobiology. 18:638–648. 10.1093/glycob/cwn045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris E.N., Kyosseva S.V., Weigel J.A., and Weigel P.H.. 2007. Expression, processing, and glycosaminoglycan binding activity of the recombinant human 315-kDa hyaluronic acid receptor for endocytosis (HARE). J. Biol. Chem. 282:2785–2797. 10.1074/jbc.M607787200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyler T., Klose C.S.N.N., Souabni A., Turqueti-Neves A., Pfeifer D., Rawlins E.L., Voehringer D., Busslinger M., and Diefenbach A.. 2012. The transcription factor GATA-3 controls cell fate and maintenance of type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 37:634–648. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Guo L., Qiu J., Chen X., Hu-Li J., Siebenlist U., Williamson P.R., Urban J.F. Jr., and Paul W.E.. 2015. IL-25-responsive, lineage-negative KLRG1(hi) cells are multipotential ‘inflammatory’ type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 16:161–169. 10.1038/ni.3078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Mao K., Chen X., Sun M.A., Kawabe T., Li W., Usher N., Zhu J., Urban J.F. Jr., Paul W.E., and Germain R.N.. 2018. S1P-dependent interorgan trafficking of group 2 innate lymphoid cells supports host defense. Science. 359:114–119. 10.1126/science.aam5809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inlay M.A., Bhattacharya D., Sahoo D., Serwold T., Seita J., Karsunky H., Plevritis S.K., Dill D.L., and Weissman I.L.. 2009. Ly6d marks the earliest stage of B-cell specification and identifies the branchpoint between B-cell and T-cell development. Genes Dev. 23:2376–2381. 10.1101/gad.1836009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka I.E., Chea S., Gudjonson H., Constantinides M.G., Dinner A.R., Bendelac A., and Golub R.. 2016. Single-cell analysis defines the divergence between the innate lymphoid cell lineage and lymphoid tissue-inducer cell lineage. Nat. Immunol. 17:269–276. 10.1038/ni.3344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose C.S.N., and Artis D.. 2016. Innate lymphoid cells as regulators of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 17:765–774. 10.1038/ni.3489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose C.S.N., Flach M., Möhle L., Rogell L., Hoyler T., Ebert K., Fabiunke C., Pfeifer D., Sexl V., Fonseca-Pereira D., et al. . 2014. Differentiation of type 1 ILCs from a common progenitor to all helper-like innate lymphoid cell lineages. Cell. 157:340–356. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim A.I., Li Y., Lopez-Lastra S., Stadhouders R., Paul F., Casrouge A., Serafini N., Puel A., Bustamante J., Surace L., et al. . 2017. Systemic Human ILC Precursors Provide a Substrate for Tissue ILC Differentiation. Cell. 168:1086–1100.e10. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]