Abstract

Background

This systematic review summarises evidence on the HIV testing barriers and intervention strategies among Caribbean populations and provides pertinent implications for future research endeavours designed to increase rates of HIV testing in the region.

Methods

We used a systematic approach to survey all literature published between January 2008 and November 2018 using four electronic databases (MEDLINE/PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Global Health). Only peer-reviewed articles published in English that examined HIV testing uptake and interventions in the Caribbean with men, men who have sex with men, female sex workers, transgender women and incarcerated individuals were included.

Results

Twenty-one studies met the inclusion criteria. Lack of confidentiality, access to testing sites, stigma, discrimination, poverty and low HIV risk perception were identified as key barriers to HIV testing. These barriers often contributed to late HIV testing and were associated with delayed treatment initiation and decreased survival rate. Intervention strategies to address these barriers included offering rapid HIV testing at clinics and HIV testing outreach by trained providers and peers.

Conclusion

HIV testing rates remain unacceptably low across the Caribbean for several reasons, including stigma and discrimination. Future HIV testing interventions should target places where at-risk populations congregate, train laypersons to conduct rapid tests and consider using oral fluid HIV self-testing, which allows individuals to test at home.

INTRODUCTION

The Caribbean is one of the most affected regions by the HIV epidemic.1 Efforts have been made to increase access to HIV testing; however, low rates of testing persist. Men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TGW) are two groups who often face barriers to engaging in HIV testing.2,3 These barriers include unemployment, underemployment and a lack of access to healthcare services.4 For these populations, same-sex practices could provoke violence and legal action. For example, in Jamaica, criminalisation of same-sex practices persists and acts as a barrier to MSM and TGW accessing HIV testing due to fear of legal action against them or their sexual partners, violence, and loss of employment due to the continued observation of the Offences Against the Person Act of 1864.5 Such criminalisation practices place an undue reporting burden on clinicians and further drives mistrust, fear and underutilisation of health services by members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersexed, Asexual, Ally (LGBTQIA+) community. HIV-related stigma may also act as a psychological burden for both incarcerated and once-incarcerated men.6

Stigma has been defined as the disqualification of an individual from being fully accepted socially,7 while discrimination entails the unfair treatment of persons on the basis of their race, age, sex and so on.8 Both stigma and discrimination are barriers to testing for HIV as well as linkage to care.9 Intersecting identities such as being a black MSM and transgender female sex workers (FSWs) further stigmatise certain groups of people and have social and cultural ramifications.10,11 Indeed, MSM, intravenous drug users, transgender persons, incarcerated persons and FSWs often experience stigma and discrimination at disproportionate rates.12–14

Although several systematic reviews have been conducted to examine factors associated with HIV testing and intervention strategies in Sub-Saharan Africa,15–17 there is no published systematic review of HIV testing barriers and intervention strategies for the Caribbean region. In this paper, we address this gap by systematically reviewing the literature for studies that have assessed factors related to HIV testing rates, late HIV testing, HIV testing barriers, as well as HIV testing interventions in order to determine effective strategies to increase HIV testing in the Caribbean.

METHODS

Search strategy

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.18 A literature search was conducted in February 2017 and was updated through April 2019 for papers that met the inclusion criteria. The electronic search included MEDLINE/PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Global Health and a manual search. These databases were selected to cover a wide range of disciplines, from social sciences to interdisciplinary to biomedical research. A combination of controlled vocabulary and Boolean-paired keywords was used, relating to HIV; testing, screening or diagnosis; and countries in the Caribbean. In addition to searching electronic databases, the authors also reviewed the references of selected studies for other relevant citations. The search categories included the terms HIV, testing and Caribbean (see table 1).

Table 1.

Search strategy for MEDLINE/PubMed

| search category | HIV | Testing | Caribbean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Search terms | (HIV infections[tw] OR HIV infections[mesh] OR HIV[tw] OR HIV[mesh] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tw]) | (testing OR tests OR test OR tested OR screening OR diagnosis) | (Caribbean[tw] OR “West Indies”[tw] OR Antigua[tw] OR Barbuda[tw] OR Bahamas[tw] OR Barbados[tw] OR “Virgin Islands”[tw] OR Cuba[tw] OR Dominica[tw] OR “Dominican Republic”[tw] OR Grenada[tw] OR Guadeloupe[tw] OR Haiti[tw] OR Jamaica[tw] OR Martinique[tw] ORAntilles[tw] OR “Puerto Rico”[tw] OR “Saint Kitts”[tw] OR Nevis[tw] OR “Saint Lucia”[tw] OR “Saint Vincent”[tw] OR Grenadines[tw] OR Trinidad[tw] OR Tobago[tw]) |

Inclusion criteria

Research studies that met the following criteria were included: (1) studies were based in the Caribbean; (2) HIV testing or screening was assessed; (3) the study was peer-reviewed; and (4) published in English. Exclusion criteria included unpublished studies (eg, conference abstracts or dissertations), papers published in languages other than English, and studies published before January 2008 or after December 2018. The time range chosen reflects intervention strategies which were deemed by the research team as ‘present’ studies and included articles that had been published no earlier than 10 years prior to the search. The included studies focused on men, MSM, FSWs, TGW and incarcerated individuals who were at least 18 years or older, were at risk for HIV infection and were living in the Caribbean.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using a set of four defined fields which specified that all articles be related to HIV testing in Caribbean countries, the full article was able to be retrieved, and the entire article was written in English. The research team worked together to review 1358 articles after duplicates were removed. Both team members independently reviewed the article search results as well as each article title and abstract to evaluate the relevance of each article; the articles were grouped into ‘Selected for Full-Text Review’ or ‘Does Not Meet Inclusion Criteria’. The research team then extracted the data from articles selected for full-text review; 27 articles were selected for full-text review and were summarised by their methods and findings to gauge their relevance and confirm that they met the inclusion criteria. Both team members independently read through each of the 27 articles in their entirety and summarised the methods, design and results to further assess the relevance of each article to the study. A third team settled any discrepancies and confusion between investigators regarding articles where no consensus had been reached pertaining to their inclusion for consistency purposes. A review protocol was developed for this study and can be accessed through contact with the study team.

Quality assessment

The quality criteria proposed by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP)19 were used to assess the methodological quality of the included articles to research design, sampling techniques, data collection, research strategy and data analysis. While CASP is regularly used to assess qualitative research enquiries, the research team deemed the criteria appropriate for evaluating quantitative papers because of its consideration of rigour, credibility, relevance and evaluation of research methods and data analysis. Ten criteria were used for the evaluation of both types of studies (table 2). Each criterion was marked by a check mark if it met the criteria or by an X on the checklist if the criteria were not met. Studies had to meet 7 out of 10 criteria items in order to be considered for full inclusion. Quality assessment was completed independently by two researchers. If disagreements arose, the article in question was discussed and the issue was resolved. Quality scores ranged from 70% to 100%.

Table 2.

Data quality assesment

| Authors | Clear statement of the aims of the research? |

Isa qualitative or mixed methodology appropriate? |

Was the research strategy appropriate to address the aims of the research? |

Was the recruitment/sampling strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? |

Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? |

Has the relationship between the researcher and participants been adequately considered? |

Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? |

Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? |

Is there a clear statement of findings? |

Is the research valuable? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams et al33 (qualitative) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Alemnji et al37 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Andrinopoulos et al46 (surey) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Andrinopoulos et al46 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Barrow and Barrow21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not applicable |

✓ | ✗ Not applicable |

✗ Not applicable |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Bourne and Charles34 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Chapin-Bardales et al23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Conserve et al22 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not applicable |

✗ Not applicable |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Duke et al40 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not applicable |

✓ | ✗ Not applicable |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Esperance et al42 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not applicable |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Figueroa et al28 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Figueroa et al21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Fleming et al24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Giguereef al47 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hineref al41 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ivers et al26 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Johnson and Cheng25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not applicable |

✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Logie et al30 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Logie et al32 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Logie et al29 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Martin et al39 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mungrue ef al38 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Myers et al*3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Orne-Gliemann et a/36 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Rodriguez-Diaz and Andrinopoulos,44 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not applicable |

✓ | ✗ Not applicable |

✗ Not applicable |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Tossas-Milliganef a/31 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Zackefa/45 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ Not reported |

✗ Not reported |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Chosen methodology

This review uses a narrative synthesis approach, which enables the researchers to synthesise the findings of multiple studies through the use of words and text to elaborate on the findings of the synthesis.20 A narrative synthesis approach allows for the findings of the articles to be explained in depth. Each article was organised by themes, which included HIV testing rates, late testing and barriers to testing. The article findings were matched with their appropriate theme; some articles were included in all multiple themes.

RESULTS

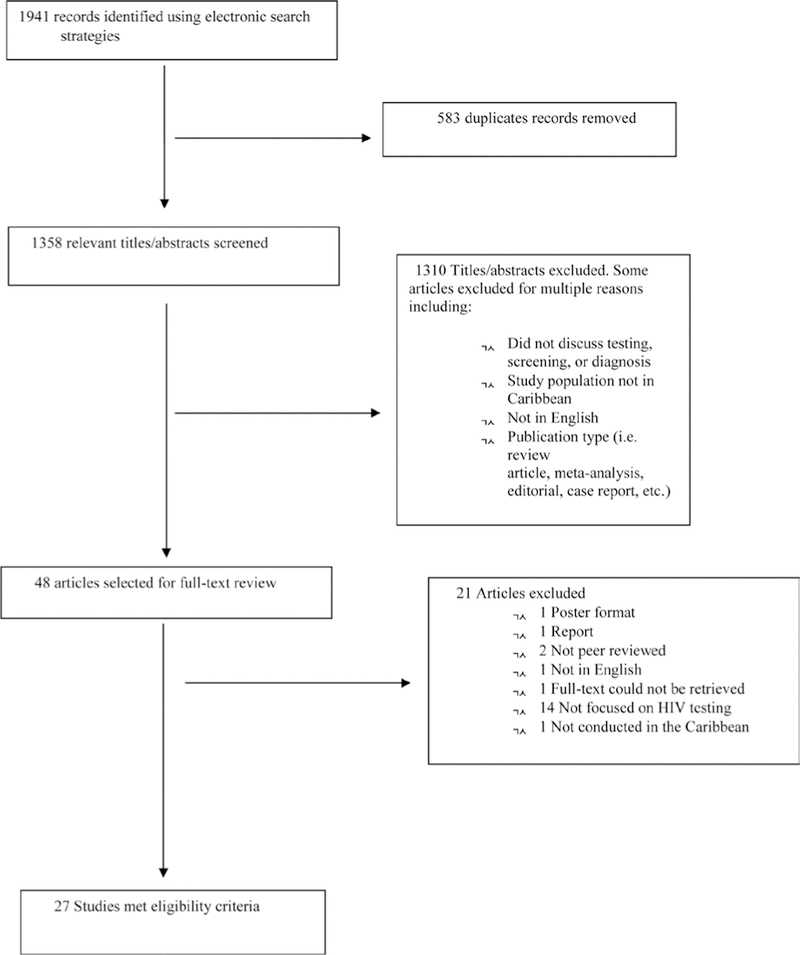

The search strategy (figure 1) yielded 1941 results (PubMed n = 774, Embase n=335, Web of Science n=564, Global Health n=268) prior to the removal of duplicate entries (n=583); 1358 unique results remained. Forty-eight articles were selected for full-text review. Twenty-one articles were excluded due to either their lack of focus on HIV testing or not being a peer-reviewed article. As shown in figure 1, 27 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. The studies were conducted in a variety of Caribbean countries (table 3).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for article inclusion/exclusion. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and MetaAnalyses.

Table 3.

Included articles

| Result | Reference | Included countries | study population | study design | sample size | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV testing | Barrow and Barrow21 | Barbados, Jamaica. | At-risk persons living in Barbados or Jamaica. | HIV surveillance data. | Not reported. | There was an increase in testing of 14 403 tests in 2000 to 26 045 in 2010. |

| Chapin-Bardales et al23 | Puerto Rico. | MSM. | Cross-sectional surveillance data. | 352 men aged 18–40+. | 59% of MSM had received a recent HIV test. | |

| Conserve et al22 | Haiti. | Haitian men. | Cross-sectional surveillance data. | 7354 men aged 18–59. | 65.24% of Haitian men had not been tested for HIV. | |

| Fleming et al24 | Dominican Republic. | Male steady partners of female cis-gender sex workers. | Sociobehavioural survey and indepth interviews. | 64 men aged 18 or older | 76.6% of steady male partners of cis-gender female sex workers living with HIV had been tested. | |

| Figueroa et al28 | Jamaica. | MSM. | Cross-sectional survey. | 201 MSM. | 57.7% of MSM reported having ever completed an HIV test, of whom 93% of men retrieved their results. | |

| Figueroa et al27 | Jamaica. | MSM. | Cross-sectional survey. | 449 MSM. | 74.7% of MSM who had accepted cash for sex in the past 3 months and 79.9% of MSM who had not accepted cash for sex reported having been tested for HIV. | |

| Ivers et al26 | Haiti. | HIV-positive patients. | Retrospective chart review. | 117 patients. | 84.8% of HIV-positive testers had obtained a diagnosis at their first encounter with a health professional. | |

| Johnson and Cheng25 | Dominican Republic, Haiti. | Men and women in 18 countries. | Cross-sectional surveys. | 27 975 men (Dominican Republic) and 4958 men (Haiti). | 11 651 Dominican men and 508 Haitian men reported having been tested. | |

| Logie et al30 | Jamaica. | Transgender women. | Cross-sectional survey. | 137 transgender women. | 103 of 137 transgender women (75.7%) had ever received an HIV test. | |

| Logie et al29 | Jamaica. | MSM. | Cross-sectional survey. | 498 MSM. | No significant differences between HIV-negative and HIV-positive MSM who had tested for HIV with regard to income, education and sex work. | |

| Late testing | Barrow and Barrow21 | Barbados, Jamaica. | At-risk persons living in Barbados or Jamaica. | HIV surveillance data. | Not reported. | Men were more likely than their female counterparts to be immunocompromised at testing. |

| Tossas-Milligan et al31 | Puerto Rico. | Open cohort of patients with HIV/AIDS. | Baseline questionnaire analysis. | 1582 patients aged 18–79. | MSM accounted for 29% of those who were late testers for HIV; older men who injected drugs had increased odds of late testing. | |

| Barriers to testing | Adams et al33 | Barbados. | Professionals and government representatives from various organisations. | Key informant interviews followed by snowball sampling. | 29 participants (16 men, 13 women) aged 30–68. | Same-sex practice stigma, breaches of confidentiality and mistrust of health systems affect testing. |

| Andrinopoulos et al35 | Jamaica. | Incarcerated men in Jamaica. | Cross-sectional quantitative survey. | 298 prison inmates aged 18 years or older. | Prison inmates who reported low experiences of HIV stigma were more likely to have tested than those who reported high experiences of stigma. | |

| Barrow and Barrow21 | Barbados, Jamaica. | At-risk persons living in Barbados or Jamaica. | HIV surveillance data. | Not reported. | Structural barriers impede HIV testing and treatment. | |

| Bourne and Charles34 | Jamaica. | Non-HIV testers in Jamaica. | Detailed questionnaire. | 1192 participants from a 2004 HIV/AIDS/STD National Knowledge, Attitudes, Beliefs, and Practices (KABP) Survey. | 87.9% of non-testers living in Jamaica reported that they were not at risk for HIV and 59.7% had no interest in learning their HIV status. | |

| Fleming et al24 | Dominican Republic. | Male steady partners of cis-gender female sex workers. | Sociobehavioural survey and indepth interviews. | 64 men aged 18 or older. | The anxiety associated with testing and fear of a positive result are barriers to testing. | |

| Logie et al32 | Jamaica. | Transgender women over the age of 18. | Cross-sectional survey. | 197 transgender women over the age of 18. | Transgender women living in Jamaica who engaged in practices that elevate HIV exposure such as substance use and sex while under the influence of drugs were unlikely to report having had an HIV test. | |

| Strategies and interventions: rapid testing and peerled testing | Alemnji et al37 | Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago. |

Laboratory managers and directors. | Surveys and questionnaire distributed throughout 11 countries. | Not reported. | 8 of 11 countries included had policies in place for HIV rapid testing and all countries were using rapid testing at main laboratory in the country. |

| Mungrue et al38 | Trinidad and Tobago. | Men and women. | Retrospective analysis and prospective analysis. | 14 580 participants. | HIV rapid testing had an increase in testing from 1652 in 2008 to 5253 in 2010, of which men tested positive more frequently. | |

| Martin et al39 | Bahamas. | Men and women. | Cross-sectional survey. | 252 participants. | Participants who expressed a test preference preferred oral fluids testing to fingerprick testing (65.8% vs 34.2%). | |

| Myers et al43 | Antigua, Barbuda. | At-risk persons for HIV | Community-based voluntary HIV counselling and testing evaluation. | 9782 testers, of whom 32% were men. | Outreach workers were trained to use a fingerprick rapid testing system that provided test results in 30 min. Of the testers to use the service, 32% were men. | |

| Rodriguez-Diaz and Andrinopoulos44 | Jamaica, Puerto Rico. | Prison inmates. | Comparison of prison programming. | 4709 inmates (Jamaica), 12 130 (Puerto Rico). | The acceptance rate for peer-led HIV testing among inmates was 63%, with a reported HIV prevalence rate of 3.3%. | |

| Zack et al45 | Haiti. | Prison inmates. | Anonymous survey administration. | 400+ inmates. | 64% of inmates who participated in health sessions with the peer health educators were willing to be tested for HIV | |

| Strategies and interventions: service provider strategies | Duke et al40 | Trinidad and Tobago. | Representatives from key national HIV programme services and technical assistance partners. | Technical working group designed same-visit HIV testing programme. | Multiple HIV programme partners identified by the Ministry of Health. | An increase of 22 trained testers in July of 2005 to 2323 testers in 2006 who used the same-visit testing service was reported and included an average of 185 trained testers who used the service per month. |

| Andrinopoulos et al46 | Jamaica. | Incarcerated men in Jamaica. | Implementation of HIV testing and treatment programme for prison inmates. | 1560 prison inmates. | HIV testing uptake targeting incarcerated men was acceptable. | |

| Hiner et al41 | Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, St Lucia, St Kitts and Nevis, St Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Barbados and the Bahamas, Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Turks and Caicos. | Programme-trained VCT providers. | Training of trainers. | 3489 providers. | A training of trainers’ VCT programme trained 3489 individuals in order for them to provide counselling and testing in several Caribbean countries; 80% of the trainers were certified in VCT and were successful in the scaling up of services for VCT. | |

| Orne-Gliemann et al36 | Dominican Republic. | Pregnant women and their male partners. | Couple-oriented post-test HIV counselling. | 1943 pregnant women. | Couples-oriented counselling was successful in increasing partner HIV testing rates. | |

| Strategies and interventions: novel methods | Giguere et al47 | Puerto Rico. | Male and transgender female sex workers. | 12-week substudy of microbicide and HIV prevention trials. | 12 male and transgender sex workers. | Mixed perspectives were found for HIV self-test use. Participant knowledge of PrEP increased and 9 of 12 indicated interest in using it. All participants reported interest in the likelihood of using a microbicide gel before having receptive anal intercourse. |

MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; VCT, voluntary counselling and testing

HIV testing rates

HIV testing rates were examined in 10 studies.21–30 In Barbados, the number of people tested increased significantly from 14 403 tests completed in 2000 to 26 045 in 2010.22 Of 7354 men in Haiti, 65.24% (n=4838) had not been tested for HIV.22 In Puerto Rico, 59% of MSM had received a recent HIV test.23 In the Dominican Republic, of the 64 steady male partners of cis-gender FSWs living with HIV only 76.6% (n=49) had ever received a previous HIV test.24 In another study, 11 651 men in the Dominican Republic and 508 men in Haiti reported to have been tested.25 In Haiti, provider-initiated testing, which included a collaboration between the Haitian Ministry of Health and a non-governmental organisation (Partners in Health), was evaluated; 3787 HIV tests were performed, and it was found that 95 out of 112 (84.8%) were HIV-positive, had prior clinical encounters data available and had obtained a diagnosis at their first encounter with a health professional.26 A majority of MSM in Jamaica (57.7%) reported having ever completed an HIV test, of whom 93% retrieved their results.28 A similar study found that 74.7% of Jamaican MSM who had accepted cash for sex in the past 3 months and 79.9% of MSM who had not accepted cash for sex reported having been tested for HIV28 There were no significant differences between HIV-negative and HlV-positive MSM who had tested for HIV with regard to income, education and sex work.29 Lastly, 75.7% of TGW reported having ever received an HIV test in Jamaica.30

Late testing

Late testing (LT) is defined as being diagnosed with AIDS 1 year after having initially tested positive for HIV; higher HIV transmission is a direct result of LT.31 Two articles reported on LT.21,30 In Barbados, 32% of newly infected persons were critically immunocompromised and men were more likely than their female counterparts to be within this group.21 In Puerto Rico, 1582 patient records from year 2000 until 2011 from a retroviral research centre were screened, and it was found that men accounted for 66% of the population while MSM accounted for 29% of those who were late testers for HIV; older men who injected drugs had increased odds of LT.31

Barriers to testing

Six studies reported on barriers to HIV testing.21,24,32–35 Structural barriers such as stigma, discrimination, gender inequality, gender-based violence, criminalisation of sexual practices associated with HIV transmission (specifically for sexual minorities), poverty and human rights abuses were all impediments to HIV testing and treatment.21 Same-sex practices were found to be heavily stigmatised in Barbados and Jamaica; breaches of confidentiality, violent attacks, testing without consent, mistrust of the health system and refusing to provide services were reported in both countries.21,33 Men conveyed the anxiety associated with testing and fear of a positive result as barriers to testing.24 TGW living in Jamaica who engaged in practices that elevate HIV exposure such as substance use and sex while under the influence of drugs were unlikely to report having had an HIV test.32 The majority (87.9%) of non-testers living in Jamaica reported that they were not at risk for HIV and 59.7% had no interest in learning their HIV status.34 Another study conducted among Jamaican inmates cited that stigma was a barrier to testing, as inmates who reported low experiences of HIV stigma were more likely to have tested than those who reported high experiences of stigma.35

Strategies and interventions

Various strategies and interventions were employed in order to assess and promote HIV testing. The strategies included rapid testing, service provider and peer-led programmes. One study reported on couple-oriented counselling (COC).36 COC was successful in increasing partner HIV testing rates in the Dominican Republic, and a higher proportion of partners used COC to test than did standard testing.36

Rapid testing

In two articles,37,38 HIV rapid testing (RT) was reported as an HIV testing promotion strategy. Eight of the 11 countries included had policies in place for HIV RT, and all countries were using RT at the main laboratory in the country.37 In the same article, three countries in 2014 reported using oral fluid tests for point-of-care testing versus nine countries that used blood-based test kits.37 HIV RT use was evaluated in Trinidad and Tobago, and an increase in testing from 1652 in 2008 to 5253 in 2010 was reported.38 Overall, 27.1% of testers cited the convenience of getting their results on the same day as a reason for testing.38 Another article reported that participants who expressed a test preference preferred oral fluids testing to fingerprick testing (65.8% vs 34.2%).39

Service provider strategies

Two articles40,41 discussed a training of trainers’ model. The development of a protocol for same-visit testing on behalf of the Ministry of Health in Trinidad and Tobago was also described.40 The training of trainers included a 3-day workshop with 14 hours of classroom instruction and 10 hours of applied training. The training was proven to be effective in increasing HIV testing after an increase from 22 clients tested in July of 2005 to 2323 testers in 2006 who used the same-visit testing service was reported and included an average of 185 trained testers who used the service per month.40 A training of trainers’ voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) programme trained 3489 individuals in order for them to provide counselling and testing in several Caribbean countries; 80% of the trainers were certified in VCT and were successful in the scaling up of services for VCT.41 One study engaged social workers to complete a symptoms checklist in order to identify symptomatic patients during HIV testing and link them to care, and in a 6-month period 11 578 adult patients were tested in 2009 and 1398 patients tested positive for HIV.42

Peer-led HIV testing

Community-based voluntary HIV counselling and testing was implemented in Antigua and Barbuda with the goal of increasing access to HIV testing and was the first peer-based programme in the region.43 Peer outreach workers and employees from laboratories and community organisations were trained to provide counselling after RT. Outreach workers were trained to use a fingerprick RT system that provided test results in 30 min. Similarly, peer educators were engaged to promote testing among incarcerated men in three studies.44–46 A sample population of inmates were offered HIV testing through the recruitment of trained peer educators in a Jamaican penitentiary; testing options included a blood sample or fingerprick using the Determine HIV assay.44 The acceptance rate for testing was 63%.44 In Haiti, ‘Health through Walls’, a peer health intervention, was conducted in a men’s prison in which peer health educators were trained to recruit participants, use a video to explain HIV transmission and prevention, and to answer questions regarding the subject matter. Sixty-four per cent of the 156 inmates who participated in the health sessions with the peer health educators were willing to be tested for HIV.45 In a study of incarcerated men in Jamaica, HIV testing and treatment services were found to be salient and acceptable.46

Novel methods

One article reported mixed findings on the perceptions of HIV self-testing and willingness to use among Puerto Rican men and transgender FSWs.47

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this systematic review is the first to focus on HIV testing barriers among multiple populations in the Caribbean. Despite increased HIV surveillance and HIV prevention strategies in the region, MSM, TGW FSWs and incarcerated men are not testing for HIV at a high rate. A number of strategies were implemented and evaluated in different Caribbean countries in an attempt to address the low HIV testing rate. These intervention strategies included but are not limited to RT, same-visit HIV testing programme and provider-initiated testing.40–44

However, stigma, criminalisation of same-sex practices and sex work remain salient barriers to HIV testing uptake; these barriers undermine the efforts of HIV prevention strategies and interventions for groups such as same-sex-loving persons and transgender persons.48 Recent investigation into the reduction of stigma has found six approaches that are of value for interventions: providing information about the manifestations of stigma and its effects on health, skill-building exercises for healthcare providers in regard to reducing stigma, active engagement in interventions alongside members of the stigmatised group(s), provide contact with the stigmatised group(s) in intervention delivery, use of an empowerment approach to improve client coping mechanisms, and including structural or policy changes which redress systems and facility restructuring.49 These strategies are also appropriate for addressing the criminalisation of sex work and same-sex practices in the Caribbean region, specifically the latter approach of included structural and policy strategies. Future research should heed these recommendations to develop interventions which target healthcare professionals and includes the participation of stigmatised and criminalised groups. Because discriminatory laws and gender inequality increase shame, fear and stigmatising attitudes, which discourage HIV testing uptake,50 advocacy for reducing stigma, discrimination and criminalisation of sexual practices for the LGBTQIA+community is imperative to the uptake of HIV testing and safe-sex practices.

This systematic review is subject to limitations that should be considered. This review includes only the full-text reviews of articles that were written in English. Relevant articles that were not in the target language were excluded. Furthermore, this review aimed to evaluate strategies which effectively increase HIV testing among multiple populations in the Caribbean, but not all studies focused solely on HIV testing. Still, all 27 of the included articles explored HIV testing in some capacity. However, commissioned reports which are kept on file with ministries of health were not included. Assessments for risks of bias were not completed for this review and present a potential issue of studies having been included which may have overestimated the true intervention effects to reported results. Lastly, only articles which were published between 2008 and 2018 were included in this review.

CONCLUSION

HIV testing interventions should target places where at-risk populations congregate, train laypersons to conduct rapid tests in these settings if professional staff is unavailable, and promote RT and provider-initiated testing when possible. All interventions should specifically target multiple populations and provide safe and inviting testing settings, especially for men, MSM and TGW, late testers, and incarcerated persons. More health education, promotion and regular testing activities need to focus on these groups in all Caribbean countries. Pre-exposure prophylaxis and HIV self-testing should also be included and evaluated in the public health efforts to reduce HIV transmission in the region.

Key messages.

-

▸

This is the first systematic review to assess HIV testing, barriers and intervention strategies among men, transgender women, female sex workers and incarcerated men in the Caribbean.

-

▸

Future research should consider that structural barriers such as stigma, discrimination, gender inequality, gender-based violence and criminalisation of sexual practices are impediments to HIV testing.

-

▸

Future research should also consider that advocacy for reducing stigma, discrimination and criminalisation of sexual practices for the LGBTQIA+ community is imperative to the uptake of HIV testing and safe-sex practices.

-

▸

Future research should also consider that rapid testing, service provider testing and peer-led testing programmes are acceptable strategies for increasing HIV testing in the region.

Acknowledgments

Funding AH was supported by the Minority Health International Research Training (MHIRT) (grant no T37-MD001448) from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institute of Health (NIH). TT was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship supported by Award Numbers T32MH020031 and P30MH062294 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and a scholar with the HIV/AIDS, Substance Abuse, and Trauma Training Program (HA-STTP), at the University of California, Los Angeles (R25DA035692). DC was supported by a training grant from NIMH (#R00MH1 10343) and NHLBI (#5R25HL105444–07). HB was supported by a training grant from NIH/NIMH (1K01MH1 16737). This work is also partially supported by an ASPIRE grant from the Office of the Vice President for Research at the University of South Carolina. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avert. Hiv and AIDS in Latin America the Caribbean regional overview, 2018. Available: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/latin-america/overview

- 2.Irvin R, Wilton L, Scott H, et al. A study of perceived racial discrimination in black men who have sex with men (MSM) and its association with healthcare utilization and HIV testing. AIDS Behav 2014;18:1272–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magno L, Silva LAVda, Veras MA, et al. Stigma and discrimination related to gender identity and vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among transgender women: a systematic review. Cad Saude Publica 2019;35:e00112718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budhwani H, Hearld KR, Hasbun J, Harchow R, et al. Transgender female sex workers’ HIV knowledge, experienced stigma, and condom use in the Dominican Republic. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendos LR. International Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex association: State-Sponsored homophobia. ILGA; Geneva; 2019: 1–196. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Turner WL. Health impact of incarceration on HIV-positive African American males: a qualitative exploration. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:450–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goffman E Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. London: Penguin, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Link BG, Phelan JC. Stigma and its public health implications. The Lancet 2006;367:528–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herek GM. Confronting sexual stigma and prejudice: theory and practice. J SocIssues 2007;63:905–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogart LM, Dale SK, Christian J, et al. Coping with discrimination among HIV-positive black men who have sex with men. Cult Health Sex 2017;19:723–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Logie C, James L, Tharao W, et al. Hiv, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work: a qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halkitis PN, Wolitski RJ, Millett GA. A holistic approach to addressing HIV infection disparities in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Am Psychol 2013;68:261–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradford J, Reisner SL, Honnold JA, et al. Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: results from the Virginia transgender health Initiative study. Am J Public Health 2013;103:1820–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brinkley-Rubinstein L Understanding the effects of multiple stigmas among formerly incarcerated HIV-positive African American men. AIDS Educ Prev 2015;27:167–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hensen B, Taoka S, Lewis JJ, et al. Systematic review of strategies to increase men’s HIV-testing in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 2014;28:2133–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keane J, Pharr JR, Buttner MP, et al. Interventions to reduce loss to follow-up during all stages of the HIV care continuum in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS Behav 2017;21:1745–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma M, Ying R, Tarr G, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of community and facility-based HIV testing to address linkage to care gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature 2015;528:S77–S85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearce-Smith N Critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) bibliography, 2012. Available: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Bibliography.pdf

- 20.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme; 1, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrow G, Barrow C. Hiv treatment as prevention in Jamaica and Barbados: magic bullet or sustainable response? J IntAssoc ProvidAIDS Care 2015;14:82–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conserve DF, Iwelunmor J, Whembolua G-L, et al. Factors associated with HIV testing among men in Haiti: results from the 2012 demographic and health survey. Am J Mens Health 2017;1 1:1322–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapin-Bardales J, Sanchez T, Paz-Bailey G, et al. Factors associated with recent human immunodeficiency virus testing among men who have sex with men in Puerto Rico, National human immunodeficiency virus behavioral surveillance system, 2011. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43:346–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleming PJ, Barrington C, Perez M, et al. Hiv testing, care, and treatment experiences among the steady male partners of female sex workers living with HIV in the Dominican Republic. AIDS Care 2016;28:699–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson D, Cheng X. The role of private health providers in HIV testing: analysis of data from 18 countries. Int J Equity Health 2014;13:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ivers LC, Freedberg KA, Mukherjee JS. Provider-initiated HIV testing in rural Haiti: low rate of missed opportunities for diagnosis of HIV in a primary care clinic. AIDS Res Ther 2007;4:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Figueroa JP, Cooper CJ, Edwards JK, et al. Understanding the high prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among socio-economically vulnerable men who have sex with men in Jamaica. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Figueroa JP, Weir SS, Jones-Cooper C, et al. High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Jamaica is associated with social vulnerability and other sexually transmitted infections. West Indian Med J 2013;62:286–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Logie CH, Kenny KS, Lacombe-Duncan A, et al. Social-ecological factors associated with HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Jamaica. Int J STD AIDS 2018;29:80–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Wang Y, et al. Prevalence and correlates of HIV infection and HIV testing among transgender women in Jamaica. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016;30:416–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tossas-Milligan KY, Hunter-Mellado RF, Mayor AM, et al. Late HIV testing in a cohort of HIV-infected patients in Puerto Rico. P R Health SciJ 2015;34:148–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Brien N, et al. Barriers and facilitators to HIV testing among young men who have sex with men and transgender women in Kingston, Jamaica: a qualitative study. J Int AIDS Soc 2017;20:21385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams OP, Carter AO, Redwood-Campbell L. Understanding attitudes, barriers and challenges in a small island nation to disease and partner notification for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2015;15:455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bourne P, Charles C. Sexual behavior and attitude towards HIV testing among non-HIV testers in a developing nation: a public health concern. N Am J Med Sci 2010;2:419–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrinopoulos K, Kerrigan D, Figueroa JP, et al. Hiv coping self-efficacy: a key to understanding stigma and HIV test acceptance among incarcerated men in Jamaica. AIDS Care 2010;22:339–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orne-Gliemann J, Balestre E, Tchendjou P, et al. Increasing HIV testing among male partners. AIDS 2013;27:1 167–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alemnji G, Guevara G, Parris K, et al. Improving the quality of and access to HIV rapid testing in the Caribbean region: program implementation, outcomes, and recommendations. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2016;32:879–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mungrue K, Sahadool S, Evans R, et al. Assessing the HIV rapid test in the fight against the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Trinidad. Hiv Aids 2013;5:191–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin IB, Williams V, Ferguson D, et al. Performance of and preference for oral rapid HIV testing in the Bahamas. J Infect Public Health 2018;11:126–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duke V, Samiel S, Musa D, et al. Same-visit HIV testing in Trinidad and Tobago. BMC Public Health 2010;10:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiner CA, Mandel BG, Weaver MR, et al. Effectiveness of a training-of-trainers model in a HIV counseling and testing program in the Caribbean region. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Esperance MC, Koenig SP, Guiteau C, et al. A successful model for rapid triage of symptomatic patients at an HIV testing site in Haiti. IntHealth 2016;8:96–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myers JJ, Maiorana A, Chaturvedi SD, et al. Uptake and outcomes associated with implementation of a community-based voluntary HIV counseling and testing program in Antigua and Barbuda. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2016;15:385–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodríguez-Díaz CE, Andrinopoulos K. Hiv and incarceration in the Caribbean: the experiences of Puerto Rico and Jamaica. P R Health Sci J 2012;31:161–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zack B, Smith C, Andrews MC, et al. Peer health education in Haiti’s National Penitentiary: the ‘Health through Walls’ experience’. J Correct Health Care 2013;19:65–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andrinopoulos K, Kerrigan D, Figueroa JP, et al. Establishment of an HIV/sexually transmitted disease programme and prevalence of infection among incarcerated men in Jamaica. Int J STD AIDS 2010;21:114–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giguere R, Frasca T, Dolezal C, et al. Acceptability of three novel HIV prevention methods among young male and transgender female sex workers in Puerto Rico. AIDS Behav 2016;20:2192–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Golub SA, Gamarel KE. The impact of anticipated HIV stigma on delays in HIV testing behaviors: findings from a community-based sample of men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:621–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nyblade L, Stockton MA, Giger K, et al. Stigma in health facilities: why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Med 2019;17:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thapa S, Hannes K, Cargo M, et al. Stigma reduction in relation to HIV test uptake in low-and middle-income countries: a realist review. BMC Public Health 2018;18:1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]