Abstract

Background

Heart failure (HF) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the elderly. Early recognition, treatment, and elimination of potentially modifiable risk factors for HF are crucial for improving both survival and health-related life quality in those with HF. We aimed to investigate whether or not there is an association between olfactory function and the presence and severity of ischemic HF.

Methods

The study included 40 patients with ischemic HF and 40 controls with coronary artery disease but without HF. All patients and controls underwent detailed physical and echocardiographic examinations. The Sniffin’ Stick test was used to evaluate olfactory function.

Results

Threshold-discrimination-identification (TDI) score was significantly lower in the patients with HF than in the controls (16.4 ± 7.8 vs. 33.3 ± 5.2, p < 0.001). When patients with ischemic HF were categorized according to New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, the TDI scores were significantly higher in the patients with NYHA class 1 HF compared to those with NYHA class 3 HF (23.4 ± 0.9 vs. 8.8 ± 7.0, p < 0.001). We also found a significant negative correlation between the TDI score and NYHA class (r = -0.769, p < 0.001) and a positive correlation between the TDI score and left ventricular ejection fraction (r = 0.902, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Olfactory function was severely impaired in the patients with ischemic HF in this study. In addition, olfactory dysfunction in the patients with ischemic HF was significantly correlated with the severity of HF.

Keywords: Cerebral hypoperfusion, Coronary artery disease, Heart failure, Olfactory dysfunction, Severity

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) is a clinical syndrome accompanied by typical symptoms and signs resulting from reduced cardiac output and elevated intracardiac pressures, mainly caused by a structural or functional cardiac abnormality. The prevalence of HF is ≥ 10 % among people > 70 years of age, and the lifetime risk of HF at 55 years of age has been estimated to be 33% for men and 28% for women.1 Despite modern diagnostic and treatment options, recent studies have reported a 12-month all-cause mortality rate for HF of 17% for hospitalized and 7% for ambulatory patients.2 HF is associated with both high mortality and severe morbidity and increased hospitalizations, which cause a substantial financial burden on patients and healthcare systems. Thus, early recognition and treatment, as well as the elimination of potentially reversible factors which play a role in the worsening of HF are crucial to improve both survival and health-related life quality in those with HF.

The ability to smell is one of the five major sensory abilities in humans. Olfaction is initiated by the binding of odour molecules to the olfactory receptors located in the peripheral olfactory neurons. Signals are then transmitted through the olfactory nerve to the olfactory bulb, and ultimately to the olfactory cortex which includes the anterior olfactory nucleus, olfactory tubercle, piriform cortex, lateral entorhinal cortex and periamygdaloid cortex, allowing for multiple signals to be processed to form a synthesized olfactory perception.3

Various kinds of pathophysiologic processes including head trauma, aging, autoimmunity, and toxic exposure are considered to contribute to olfactory impairment.4 Maintaining adequate blood supply to the brain can be considered to be the most prominent function of the heart; however, in HF, cranial hypoperfusion may occur and the heart may fail to provide sufficient blood supply to the cerebellum, amygdala, hypothalamus, and hippocampus, which may consequently impair olfactory function.5,6

In the present study, we aimed to investigate whether or not there is an association between olfactory function and the presence and severity of ischemic HF.

METHODS

Study population

A total of 40 patients aged between 18-65 years with ischemic HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) presenting to the cardiology department of a tertiary hospital were consecutively included in this case-control study which was performed between December 2017 and February 2018. HF patients with an ischemic etiology were included in this study, while patients with other etiological causes of HF were excluded. To eliminate any confounders that may influence olfactory tests, the patients who had used diuretics within the last 3 days and those taking amiodarone, digitalis, and other medications that may affect odour perception were not included in this study.7,8 In addition, patients with structural nasal pathology including nasal polyps, allergic rhinitis and septal deviation, and those with neurodegenerative diseases, major depression, end-stage renal parenchymal and liver diseases, untreated hypo- and hyperthyroidism, malignancies, acute HF and patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV HF were also excluded. Due to the high prevalence of olfactory dysfunction in individuals over 65 years of age, patients who were older than 65 years were also excluded from this study. Post-hoc power analysis (effect size 0.60, alpha error: 0.05 and 40 patients in each group) performed with G*Power software version 3.1.9.4 provided a 0.8449557 power for the independent samples t-test. We selected 40 age- and sex-matched individuals with coronary artery disease (CAD) but without HF as a control group. The diagnosis of HF was based on the most recent international guidelines.9 HFrEF was defined as a decline in ejection fraction < 40 % in addition to signs and symptoms of HF. The diagnosis of CAD was based on previous coronary angiographies and defined as the presence of > 50% stenosis in at least one coronary artery or experiencing any kind of coronary revascularization. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (decision no: 2011-KAEK-27/2017-E.128097).

Echocardiographic evaluation

All patients underwent echocardiographic examinations using a 2.5-MHz probe with a Vivid 7 Pro (GE Vingmed, Horten, Norway) echocardiography device in accordance with the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography.10 All echocardiographic examinations were performed by one experienced cardiologist blinded to the clinical data of the patients. Conventional echocardiographic images were obtained from the parasternal and apical views according to the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography.11 Left ventricular volumes were obtained from the apical 4-chamber view, and the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was computed using the modified Simpson’s formula. Systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) was calculated using the formula; sPAP = 4 × (peak tricuspid regurgitation velocity)2 + right atrial pressure.

Olfactory assessment

We used the Sniffin’ Stick test (Heinrich Burghart, GmbH, Wedel, Germany) which consists of three subtests that measure odour threshold (OT), odour discrimination (OD) and odour identification (OI) to evaluate olfactory function in the patients with ischemic HF and controls. We summed the scores of the three subtests to obtain the threshold-discrimination-identification (TDI) score. Patients with a score > 30 were defined as normosmic, those with a score between 16 and 30 were defined as hyposmic, and those with a score < 16 were defined as anosmic.12

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows, version 20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine the distribution of variables. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and qualitative variables are presented as count and percentage. Data that were not normally distributed were analysed with Kruskal-Wallis variance analysis followed by Bonferroni-corrected Mann-Whitney U test. Comparisons among groups with respect to demographic data, Sniffin’ Sticks test and echocardiographic parameters were performed using the Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U test, depending on distribution. The chi-square test was used for univariate analysis of the categorical variables. Correlation analyses were performed to investigate the associations between olfactory function and the severity of LVEF and sPAP. A p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

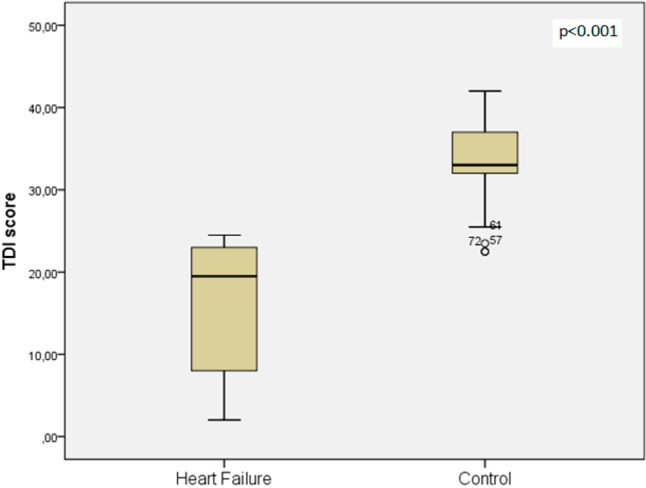

The demographic features, laboratory measurements, olfactory tests and echocardiography results of the patients with and without HF are listed in Table 1. Olfactory subtest scores were significantly lower in the patients with HF compared to the controls (OT; 3.3 ± 1.7 vs. 9.8 ± 2.3, OD; 7.3 ± 3.3 vs. 10.4 ± 2.0, OI; 5.7 ± 3.7 vs. 13.0 ± 2.1, respectively, all p < 0.001). The TDI score was also significantly lower in the patients with ischemic HF than the controls (16.4 ± 7.8 vs. 33.3 ± 5.2, p < 0.001) (Figure 1). The mean LVEF was 33.0 ± 7.2%, and the mean sPAP was 31.7 ± 8.6 mmHg in the patients with ischemic HF.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients and controls.

| Heart failure (n = 40) | Controls (n = 40) | p value | |

| Age (years) | 53.6 ± 9.8 | 52.7 ± 9.5 | 0.463 |

| Gender (male) (n, %) | 22 (55.0) | 23 (57.5) | 0.956 |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 35 (87.5) | 37 (92.5) | 0.712 |

| Diabetes (n, %) | 15 (37.5) | 14 (35) | 0.964 |

| Smoking (n, %) | 6 (15) | 8 (20) | 0.769 |

| Drugs | |||

| ASA | 39 (97.5) | 37 (92.5) | 0.615 |

| RAS blocker | 38 (95) | 39 (97.5) | 0.608 |

| Beta blocker | 36 (90) | 33 (82.5) | 0.516 |

| Statin | 29 (72.5) | 28 (70) | 1.000 |

| Alcohol consumption (n, %) | 4 (10). | 6 (15). | 0.735 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9 ± 2.0 | 26.2 ± 2.0 | 0.373 |

| MBP (mmHg) | 94.6 ± 9.87 | 95.2 ± 9.84 | 0.523 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 136.9 ± 12.80 | 140.7 ± 12.6 | 0.188 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 73.4 ± 9.8 | 73.6 ± 9.7 | 0.946 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dl) | 112 ± 19.2 | 111 ± 18.7 | 0.989 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.89 ± 0.18 | 0.84 ± 0.19 | 0.253 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.3 ± 1.44 | 13.6 ± 1.48 | 0.448 |

| OT score | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 9.8 ± 2.3 | < 0.001 |

| OD score | 7.3 ± 3.3 | 10.4 ± 2.0 | < 0.001 |

| OI score | 5.7 ± 3.7 | 13.0 ± 2.1 | < 0.001 |

| TDI score | 16.4 ± 7.8 | 33.3 ± 5.2 | < 0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 33.0 ± 7.2 | 62.9 ± 4.4 | < 0.001 |

| LVEDV(ml) | 134.3 ± 20.8 | 99.9 ± 11.2 | < 0.001 |

| LVESV (ml) | 80.0 ± 29.1 | 38.5 ± 5.8 | < 0.001 |

| sPAP (mmHg) | 31.7 ± 8.6 | 25.6 ± 5.7 | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as number (percentage), mean ± standard deviation.

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume; MBP, mean blood pressure; OD, odour discrimination; OI, odour identification; OT, odour threshold; SBP, systolic blood pressure; sPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure; TDI, threshold-discrimination-identification.

Figure 1.

Comparison of threshold-discrimination-identification (TDI) score for heart failure and control groups.

According to the NYHA classification, 14 patients were class 1, 13 were class 2, and 13 were class 3 HF. When the patients with ischemic HF were categorized according to NYHA class, the TDI scores were significantly higher in the patients with NYHA class 1 HF compared to those with NYHA class 3 HF (23.4 ± 0.9 vs. 8.8 ± 7.0, p < 0.001) (Table 2). Correlation analysis revealed strong negative correlations between TDI score and NYHA class (r = -0.769, p < 0.001) and sPAP (r = -0.380, p = 0.016), and a positive correlation between TDI score and LVEF (r = 0.902, p < 0.001). The Sniffin’ Sticks subtest scores of OT, OD, and OI were also significantly correlated with NYHA class, sPAP and LVEF (Table 3).

Table 2. Olfactory test scores and functional classes of patients with ischemic heart failure.

| NYHA Class 1 (n = 14) | NYHA Class 2 (n = 13) | NYHA Class 3 (n = 13) | Overall p value | |

| OT score | 4.6 ± 1.2* | 3.1 ± 1.3 | 2.0 ± 1.8† | < 0.001 |

| OD score | 10.0 ± 1.8* | 6.9 ± 2.5 | 4.7 ± 1.8† | < 0.001 |

| OI score | 8.7 ± 1.9* | 6.4 ± 2.3# | 1.9 ± 3.0† | < 0.001 |

| TDI score | 23.4 ± 0.9* | 16.5 ± 5.1# | 8.8 ± 7.0† | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

HF, heart failure; NYHA, New York Heart Association; OD, odour discrimination; OI, odour identification; OT, odour threshold; TDI, threshold-discrimination-identification.

* p < 0.05 between NYHA class 1 and NYHA class 2 HF patients. # p < 0.05 between NYHA class 2 and NYHA class 3 HF patients. † p < 0.05 between NYHA class 1 and NYHA class 3 HF patients.

Table 3. Results of correlation analyses between olfactory scores and HF parameters.

| NYHA | OT | OD | OI | TDI | ||||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| OT | -0.632 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| OD | -0.617 | < 0.001 | 0.583 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| OI | -0.727 | < 0.001 | 0.821 | < 0.001 | 0.621 | < 0.001 | ||||

| TDI | -0.769 | < 0.001 | 0.875 | < 0.001 | 0.737 | < 0.001 | 0.936 | < 0.001 | ||

| LVEF | -0.742 | < 0.001 | 0.734 | < 0.001 | 0.793 | < 0.001 | 0.859 | < 0.001 | 0.902 | < 0.001 |

| sPAP | 0.290 | 0.070 | -0.286 | 0.074 | -0.402 | 0.010 | -0.323 | 0.042 | -0.380 | 0.016 |

HF, heart failure; NYHA, New York Heart Association; OD, odour discrimination; OI, odour identification; OT, odour threshold; sPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure; TDI, threshold-discrimination-identification.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study demonstrated that olfactory function was significantly impaired in the patients with ischemic HF compared to the CAD patients without HF. Additionally, in the patients with ischemic HF, the severity of olfactory dysfunction increased with increasing NYHA functional class. Moreover, there was a significant and strong negative correlation between TDI score and NYHA class, indicating an association between olfactory function and HF severity. Finally, TDI scores were also positively correlated with LVEF.

The overall prevalence of olfactory dysfunction in old age is reported to be as high as 25%. Nevertheless, there are limited data concerning the relationship between olfactory dysfunction and cardiovascular diseases which are also highly prevalent in those with advanced age. Several studies conducted in elderly populations have investigated the relationships between common risk factors for CAD and olfactory dysfunction, and revealed associations between olfactory dysfunction and having diabetes or hypertension for at least 10 years, conditions which are also well-known risk factors for the development of CAD.13 Smoking, which is a significant risk factor for CAD, has also been reported to have an impact on olfactory dysfunction. Although the mechanism of this impairment has not been clearly elucidated, it may be due to either neural ischemia or direct damage to the olfactory epithelium.

Subclinical atherosclerosis determined by increased carotid intima-media thickness and carotid plaque burden has been shown to be associated with olfactory decline, particularly in individuals < 60 years of age, suggesting that atherosclerosis may play a role in early olfactory dysfunction in elderly individuals.14 In patients with diabetes, Weinstock and colleagues showed that the presence of macrovascular complications was related to a decline in olfactory ability. They speculated that macrovascular disease leading to ischemia at the olfactory area was the cause of functional loss. Although none of the aforementioned studies included patients with angiographically proven CAD, the current data indicate that atherosclerosis is associated with olfactory decline, probably due to ischemic damage to the neural structures functioning in the olfaction process.

Although both conditions are rather common in those with advanced age, no previous study has directly investigated the relationships between HF and olfactory dysfunction. In a population-based study performed by Seubert and colleagues, the authors reported that HF was recorded in 15% of patients with olfactory dysfunction.15 In another study that enrolled patients undergoing cardiac surgery, a history of HF was reported in 16% of patients with olfactory dysfunction.16

Heart failure causes systemic hypoperfusion and reduced blood supply to vital organs and tissues, and increasing evidence has shown that it is one of the leading causes of cognitive dysfunction and cerebral hypoperfusion in the elderly. In the advanced stages of HF, cerebral blood flow is reduced by approximately 20% compared to healthy controls, which may lead to cognitive dysfunction.17 Moreover, a cerebral blood flow < 35.4 mL/min/100 g has been reported to be a predictor of death and urgent transplantation in patients with systolic HF. Lee et al. reported increases in the levels of cerebral metabolites including N-acetylaspartate, creatine, myoinositol, and choline after heart transplantation.18 Magnetic resonance imaging studies of patients with HF have revealed the presence of hyperintense areas in white matter and atrophy in grey matter, including the hippocampus and frontal cortex.19 Given the importance of the optimal function of these areas for olfactory perception, direct cerebral injury in these areas caused by cerebral hypoperfusion as a result of HF may lead to central olfactory dysfunction.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to demonstrate a high prevalence of olfactory dysfunction in patients with HF as well as a clear inverse association between olfactory ability and NYHA class, which indicates the severity of HF. To eliminate the impact of CAD as a confounder that may have influenced olfactory function, we included a control group consisting of patients with CAD but without HF. Nevertheless, the impact of both clinical and subclinical atherosclerosis on olfactory dysfunction in patients with ischemic HF cannot be disregarded. However, we believe that the impaired cerebral blood flow in patients with HF is the primary cause of olfactory decline recorded in this study.

Patients with HF have also been reported to have a high rate of depression ranging from 40% to 60%. The reduced cerebral blood flow in HF may also lead to various degrees of cognitive disorders including dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, which have been reported in approximately 23% to 80% of these patients.20 Adamski et al. reported that impairment in cognitive function begins in the early stages of HF, long before the emergence of a decline in LVEF.21 Therefore, the olfactory dysfunction demonstrated in our study may be an indicator of the impaired cognitive function present in patients with HF.

Odour sensation is principally initiated by signals activated through G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) with the activation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Activated cAMP leads to an efflux of K+ and influx of Na+ and Ca+, thus biochemically initiating the odour sensation process at the receptor level.3 Previous studies have shown that circulating levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and interleulin-1 (IL-1) are increased in patients with HF,22 and that the increase in the levels of these cytokines leads to dysfunction in odour-sensitive GPCRs located in the olfactory epithelium.23 High levels of TNFα and IL-1 have also been shown to disrupt the accumulation of cAMP and inhibit Ca+ transportation, effects which may further impair the olfactory process.24 Thus, we suggest that the proinflammatory state in patients with HF should be considered as a potential contributor to olfactory dysfunction.

One-third of patients with HF suffer from thiamine deficiency, which causes cytological changes and is known to be associated with atrophy in the hippocampus and also to lead to massive cell loss in the olfactory bulb.25,26 In patients with HF, the structural and chemical changes occurring in the olfactory bulb and hippocampus due to thiamine deficiency may play a role in the development of olfactory dysfunction.

Taken together, we believe that cerebral hypoperfusion, increased proinflammatory cytokines and thiamine deficiency in patients with HF may combine to cause a series of pathological changes leading to olfactory dysfunction. Hence, early recognition of olfactory dysfunction in patients with HF may prove to be beneficial in predicting the decline in LVEF and increase in NYHA class. Therefore, olfactory evaluation may be instrumental in determining patients with a worse prognosis, and could prompt physicians to adopt an aggressive approach to medical treatment for these patients. However, further research is required on this topic.

The present study has several limitations. First, we did not measure cerebral blood flow or conduct imaging studies to show the structural changes in neural tissue. Second, we did not perform tests to identify cognitive dysfunction or depression, which are frequent problems in patients with HF. In addition, we did not measure levels of thiamine or proinflammatory cytokines. Finally, the lack of a control group consisting of purely healthy controls is another limitation of the present study. However, owing to the high prevalence of CAD in patients with HF, we used a control group consisting of patients with CAD but without HF to address the specific role of HF on olfactory dysfunction.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the olfactory function was severely declined in the patients with ischemic HF in this study. Moreover, olfactory scores were strongly correlated with LVEF and negatively correlated with NYHA class. We speculate that olfactory testing; a valid, simple and low-cost way of identifying cerebral hypoperfusion might be used for the early recognition of functional deterioration in patients with ischemic HF. More aggressive treatment for patients with olfactory dysfunction might prevent further morbidity and mortality in these patients.

Acknowledgments

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bleumink GS, Knetsch AM, Sturkenboom MCJM, et al. Quantifying the heart failure epidemic: prevalence, incidence rate, lifetime risk and prognosis of heart failure The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:706–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maggioni AP, Dahlstrom U, Filippatos G, et al. EURObservational Research Programme: the Heart Failure Pilot Survey (ESC-HF Pilot). Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;10:1076–1084. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadley K, Orlandi RR, Fong KJ. Basic anatomy and physiology of olfaction and taste. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2004;37:1115–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregorio LL, Caparroz F, Nunes LM, et al. Olfaction disorders: retrospective study. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;80:11–17. doi: 10.5935/1808-8694.20140005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woo MA, Palomares JA, Macey PM, et al. Global and regional brain mean diffusivity changes in patients with heart failure. J Neurosci Res. 2015;93:678–685. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim MS, Kim JJ. Heart and brain interconnection - clinical implications of changes in brain function during heart failure. Circ J. 2015;79:942–947. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doty RL, Kamath V. The influence of age on olfaction: a review. Front Psychol. 2014;5:20. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doty RL, Philip S, Reddy K, Kerr KL. Influences of antihypertensive and antihyperlipidemic drugs on the senses of taste and smell: a review. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1805–1813. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200310000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang CC, Wu CK, Tsai ML, et al. 2019 focused update of the guidelines of the Taiwan Society of Cardiology for the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2019;35:244–283. doi: 10.6515/ACS.201905_35(3).20190422A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, et al. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on Quantitation of Two-Dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1989;2:358–367. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(89)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Circulation. 2003;108:1146–1162. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000073597.57414.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hedner M, Larsson M, Arnold N, et al. Cognitive factors in odour detection, odour discrimination, and odour identification tasks. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2010;32:1062–1067. doi: 10.1080/13803391003683070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gouveri E, Katotomichelakis M, Gouveris H, et al. Olfactory dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus: an additional manifestation of microvascular disease? Angiology. 2014;65:869–876. doi: 10.1177/0003319714520956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Fischer ME, et al. Inflammatory and vascular markers and olfactory impairment in older adults. Age Ageing. 2015;44:878–882. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seubert J, Laukka EJ, Rizzuto D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of olfactory dysfunction in old age: a population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:1072–1079. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown CH, Morrissey C, Ono M, et al. Impaired olfaction and risk of delirium or cognitive decline after cardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:16–23. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi BR, Kim JS, Yang YJ, et al. Factors associated with decreased cerebral blood flow in congestive heart failure secondary to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1365–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CW, Lee JH, Yang HS, et al. Effects of heart transplantation on cerebral metabolic abnormalities in patients with congestive heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:353–355. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan A, Kumar R, Macey PM, et al. Visual assessment of brain magnetic resonance imaging detects injury to cognitive regulatory sites in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2013;19:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malik AS, Giamouzis G, Georgiopoulou VV, et al. Patient perception versus medical record entry of health-related conditions among patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:569–572. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adamski MG, Sternak M, Mohaissen T, et al. Vascular cognitive impairment linked to brain endothelium inflammation in early stages of heart failure in mice. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:pii: e007694. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ueland T, Gullestad L, Nymo SH, et al. Inflammatory cytokines as biomarkers in heart failure. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;443:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vasudevan NT, Mohan ML, Gupta MK, et al. G-beta-gamma independent recruitment of g-protein coupled receptor kinase 2 drives tumor necrosis factor alpha induced cardiac beta-adrenergic receptor dysfunction. Circulation. 2013;128:377–387. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bick RJ, Liao JP, King TW, et al. Temporal effects of cytokines on neonatal cardiac myocyte Ca2+ transients and adenylate cyclase activity. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H1937–H1944. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.4.H1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanninen SA, Darling PB, Sole MJ, et al. The prevalence of thiamin deficiency in hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamada S, Hirashima H, Imaeda M, et al. Thiamine deficiency induced massive cell death in the olfactory bulb of mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72:1193–1202. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]