Abstract

Patients with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) frequently manifest comorbid neuropsychiatric symptoms with depression and anxiety being most frequent, and individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) have an increased prevalence of LOAD. This suggests shared etiologies and intersecting pathways between LOAD and MDD. We performed pleiotropy analyses using LOAD and MDD GWAS data sets from the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project (IGAP) and the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC), respectively. We found a moderate enrichment for SNPs associated with LOAD across increasingly stringent levels of significance with the MDD GWAS association (LOAD|MDD), of maximum four and eightfolds, including and excluding the APOE-region, respectively. Association analysis excluding the APOE-region identified numerous SNPs corresponding to 40 genes, 9 of which are known LOAD-risk loci primarily in chromosome 11 regions that contain the SPI1 gene and MS4A genes cluster, and others were novel pleiotropic risk-loci for LOAD conditional with MDD. The most significant associated SNPs on chromosome 11 overlapped with eQTLs found in whole-blood and monocytes, suggesting functional roles in gene regulation. The reverse conditional association analysis (MDD|LOAD) showed a moderate level, ~sevenfold, of polygenic overlap, however, no SNP showed significant association. Pathway analyses replicated previously reported LOAD biological pathways related to immune response and regulation of endocytosis. In conclusion, we provide insights into the overlapping genetic signatures underpinning the common phenotypic manifestations and inter-relationship between LOAD and MDD. This knowledge is crucial to the development of actionable targets for novel therapies to treat depression preceding dementia, in an effort to delay or ultimately prevent the onset of LOAD.

Subject terms: Molecular neuroscience, Depression, Comparative genomics, Clinical genetics

Introduction

Patients with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) frequently manifest comorbid neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), with depression and anxiety being most prevalent1–4. Furthermore, depression has been found to be associated with increased risk to develop LOAD5–9. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a neuropsychiatric condition, and patients with MDD, especially in late life, exhibit cognitive deficits and have an increased incidence of LOAD10. Thus, MDD may be a risk factor for LOAD, and/or part of the heterogeneity of NPS in LOAD11,12. These lines of evidence suggest the possibility of shared etiologies and intersecting pathways between LOAD and MDD.

The pathogenesis of both LOAD and MDD is complex and involves polygenic risk factors. Several studies suggested that risk genes for MDD may be involved in LOAD13–15. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified numerous loci associated with the risk to develop LOAD16–22 and MDD23,24. These large publicly accessible GWAS data sets could be leveraged to facilitate investigations of whether the comorbidity and risk inter-relationship of these disorders can be explained by common genetic variants. Recently, a statistical method to evaluate genetic pleiotropic effects using GWAS summary statistics (P-values and odds ratios) was developed25–28, and has been utilized to examine genetic pleiotropy between multiple diverse diseases and phenotypes25–27,29–35, including LOAD with other conditions. Most prominent, polygenic overlaps were reported for LOAD with modulation of c-reactive protein (CRP) and plasma lipids28,36, and with type 2 diabetes37. Here, we utilize this statistical framework to investigate the genetic overlap between LOAD and MDD.

To date, the underpinning genetics of NPS heterogeneity in LOAD and of depression and LOAD comorbidity are yet to be discovered. While it has been shown that MDD-associated genes may contribute to LOAD13–15, a recent study found no evidence to support a common polygenic structure for LOAD and MDD38. Nonetheless, the genetic pleiotropy between LOAD and neuropsychiatric disorders, including MDD, has been understudied. In this study, we characterized the genetic signatures that are shared between LOAD and MDD. We undertook a robust new statistical strategy that integrates results from large multicenter meta analyses of LOAD and MDD GWAS to identify genetic variants and genes that are associated with LOAD conditional on an association with MDD. Our analysis pipeline progresses from identification of pleiotropic single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) common to the two conditions, through the genomic loci tagged by the SNPs and the candidate genes within the associated region, and ultimately, biological pathways.

Materials and methods

GWAS data sets

GWAS summary statistics were obtained from publicly accessible web sites for the LOAD GWAS and the MDD GWAS (see “Data availability”).

The LOAD GWAS data set consisted of summary statistics of P-values, beta coefficients, and standard errors, effect alleles from the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Disease Project (IGAP)22. IGAP is a large three-stage study based upon GWAS on individuals of European ancestry. Stage 1 IGAP results were used, which included genotyped and imputed data on 11,480,632 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from 21,982 Alzheimer’s disease cases and 41,944 cognitively normal controls from four consortia: The Alzheimer Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC); The European Alzheimer’s disease Initiative (ELOADI); The Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology Consortium (CHARGE); and The Genetic and Environmental Risk in LOAD Consortium Genetic and Environmental Risk in LOAD/Defining Genetic, Polygenic and Environmental Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium (GERAD/PERADES).

The MDD GWAS data set (PGC-MDD2) consisted of summary statistics of P-values, odds ratios and standard errors, reference allele, imputation quality score (INFO), and direction of effect in each cohort from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium39. The results were obtained for five cohorts described by Wray et al.39 (deCODE, Generation Scotland, GERA, iPSYCH, and UK Biobank), excluding the Hyde et al. cohort24 (23and Me, Inc.). These results included genotyped and imputed data on 13,554,550 variants from 59,851 MDD cases and 113,154 controls. Restricting variants to SNPs with high-quality imputation scores (0.6 ≤ INFO < 1.06) resulted in a total of 9,154,389 SNPs in common for the two data sets that were used for further analysis. Details for the genotyping procedure, quality control, and GWAS analysis are provided in the primary papers for the LOAD GWAS22 and the MDD GWAS39. All genomic coordinates are based on NCBI Build 37/UCSC hg19.

Statistical and bioinformatics analysis

Pleiotropy analysis

The pleiotropy analysis strategy, based on conditional false discovery rates, fold-enrichment plots, and conditional quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plots, is described in detail elsewhere28,37. In brief, for two phenotypes A and B, pleiotropic enrichment of phenotype A conditional on phenotype B exists if the proportion of variants (SNPs) statistically significantly associated with phenotype A increases as a function of increased statistically significant SNP associations with phenotype B. The number of SNPs associated with phenotype A was determined for several thresholds of SNP association with phenotype B; the proportions were calculated relative to a baseline of all SNPs statistically significantly associated with phenotype A. For this study the analysis was run in both directions, with primary phenotype A as late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, and conditional phenotype B as MDD, followed by interchange of the primary and conditional phenotypes. Fold-enrichment plots graphically depict pleiotropy by showing fold enrichment in terms of numbers of SNPs on the ordinate and nominal –log10(P) values for association with cognitive impairment on the abscissa. Separate curves were shown for subsets of SNPs that reach specific levels of significance for their association with MDD, respectively. Conditional quantile–quantile plots for the same data shown in the fold-enrichment plots provided additional assessment of genetic pleiotropy for each set of GWAS results. Following the prior analysis strategy28, we focused the analysis for polygenic enrichment on SNPs below the standard GWAS Bonferroni-corrected P-value thresholds. Following the example of Wang et al.37 and Desikan et al.28, the SNP data were pruned to eliminate correlated pairs of SNPs based on linkage disequilibrium (LD) measured in the 1000 Genomes data set (Phase 3, version 5 of the 1000 Genomes Project, European panel). If R2 value for a pair of SNPs was >0.2, the SNP with the lower minor allele frequency (MAF) was removed.

For identification of specific SNPs conditionally associated with LOAD and MDD, a conditional false discovery rate (FDR) statistic (Q value) was calculated as described in the prior implementation of this analysis strategy28,37 and other publications25–27,30–33. This framework was an extension of the standard analysis for FDR calculations and uses information from the secondary phenotype to re-rank the P-values for the primary phenotype. The value of the conditional FDR for each SNP was calculated in the case where LOAD is the principal phenotype conditioned on MDD (LOAD|MDD) as well as the reverse (MDD|LOAD). We used a conditional FDR of Q < 0.05 to show statistical significance. The significance threshold of Q = 0.05 for the conditional FDR40 corresponds to 5 false positives per 100 reported associations. Manhattan plots of the conditional FDRs for were used to summarize the data.

In order to detect common susceptibility loci for LOAD and MDD after calculating the conditional FDRs (Q values) for each SNP under LOAD|MDD and MDD|LOAD, we computed the conjunction conditional FDR, which refers to the probability that a given SNP is null for both phenotypes. The conjunction conditional FDR (ccFDR) is the maximum value of the two conditional FDR (Q) values. A Manhattan plot was produced for the conjunction conditional FDR.

Mendelian randomization analysis

To test for a causal relationship between the set of SNPs identified by the conditional analysis, we performed Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis41 using the LOAD GWAS SNPs as instrumental variables, LOAD as the exposure, and MDD as the outcome. The LOAD GWAS SNPs were used to define the instrumental variables. These SNPs are highly replicated, share rigorous genetic associations with LOAD, and are randomly distributed in the general population with respect to lifestyle and environmental factors. Analysis of horizontal pleiotropy, where the SNPs associate with LOAD but influence MDD through pathways that are not specific to AD (e.g. the exposure) was completed. Two sample MRs42 were used for the statistical analysis using the MR-Base resource43,44. The MR Egger methodology45 was used for all calculations. For the exposure (LOAD), default parameter settings of a P-value threshold of 1 × 10−8, LD R2 of 0.001, clumping distance of 10 kb were used.

Functional genomics bioinformatics analyses

Functional bioinformatics analysis was performed to evaluate the biological significance of the SNPs that were identified in the pleiotropy analysis as showing conditional association between LOAD and MMD. Two bioinformatics analysis tools were used to map the SNPs to genes by proximity, define the genomic context for the variant, annotate effects on phenotypes, and identify relevant literature about the variant. The UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) was used to map each variant to proximate genes and to provide the first level of information about the genes and biological consequences of the genes46. SNPnexus (http://www.snp-nexus.org/) was used to provide additional annotation on gene/protein consequences and phenotype- and disease-association for the variants47,48.

Gene set enrichment and pathway analysis was completed using i-Gsea4Gwas49. This analysis was run on all SNP association results for the IGAP discovery data set and the MDD replication data set using the FDR Q values Q(LOAD|PSTD). The SNP to gene mapping was limited to 500 kb upstream and downstream of the gene. Candidate gene sets included canonical pathways, GO biological processes, and GO molecular function.

Gene expression analysis and clustering was performed using the GENE2FUNC capability of the FUMA GWAS analysis suite50. Gene expression data for the 53 tissue types was from Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) v6, for the whole blood from the GTEx portal v7 data release51,52, and for the monocytes from the Cardiogenics study53.

eQTL analyses were performed on the GTEx portal using whole-blood data from GTEx portal v7 data release, and using a SAS macro for the monocyte data obtained from the Cardiogenics study53. For the latter, we applied a Bonferroni level of 5.4 × 10−7 for significance.

Proxy SNPs (D’ = 1, R2 > 0.9) were found using the NIH LDproxy tool54 in the CEU and GBR populations (https://ldlink.nci.nih.gov/?tab=ldproxy).

Results

Genome-wide association summary results for LOAD and MDD

Prior to assessment of polygenic overlap between LOAD and MDD, the individual GWAS for each phenotype was compared for quality control (QC) and overall genetic association statistics. QC details are reported in the primary publications for IGAP LOAD22 and for the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium MDD GWAS (PGC-MDD2)39. Genomic inflation was well controlled in both of these GWAS, and the minor allele frequencies (MAF) were limited to MAF > 0.01. Genome-wide significance levels were set at P ≤ 5 × 10−8 for both the LOAD GWAS and for the MDD GWAS based on Bonferroni corrections for the number of SNPs.

Inspection of the Manhattan plots (Supplementary Fig. S1) show several regions of the genome with nominal levels of association (P ≤ 1 × 10−5) for the different phenotypes, LOAD and MDD. The Q–Q plots (Supplementary Fig. S2) show that population stratification was accounted for in the association analysis.

Assessment of polygenic overlap between LOAD and MDD

Genome-wide fold enrichment

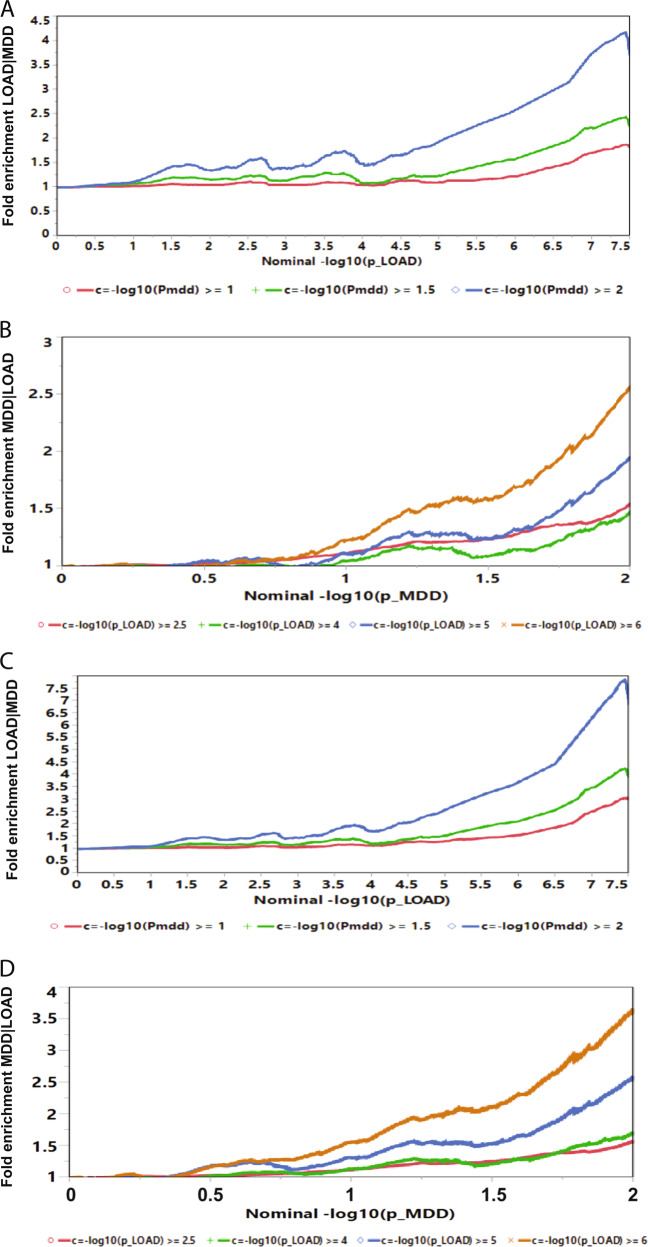

The fold-enrichment plot demonstrated SNP moderate (2.0–4.2-fold) enrichment for LOAD across increasingly stringent levels of significance with the MDD GWAS association (LOAD|MDD) (Fig. 1a). The reverse conditional association (MDD|LOAD) showed enrichment of ~1.8–7.0-fold (Fig. 1b). These results support a moderate level of polygenic overlap between LOAD and MDD.

Fig. 1. Fold-enrichment plots.

Ordinate is fold enrichment. a Abscissa is nominal –log10(P) for SNP association with LOAD, curves are differentiated by the threshold for level of statistical significance for SNP association with the secondary phenotype (MDD). Plot is made for the results from the full genome. b Abscissa is nominal –log10(P) for SNP association with MDD, curves are differentiated by the threshold for level of statistical significance for SNP association with the secondary phenotype (LOAD). Plot is made for the results from the full genome. c Abscissa is nominal –log10(P) for SNP association with LOAD, curves are differentiated by the threshold for level of statistical significance for SNP association with the secondary phenotype (MDD). Plot is made for the results excluding SNPs in the APOE-associated region. d Abscissa is nominal –log10(P) for SNP association with MDD, curves are differentiated by the threshold for level of statistical significance for SNP association with the secondary phenotype (LOAD). Plot is made for the results, excluding SNPs in the APOE-associated region.

Fold enrichment excluding the APOE region on chromosome 19

The chromosome 19 region containing the APOE gene is well-established as a strong genetic risk factor for LOAD, with GWAS association P-values on the order of 10−238 to 10−12 in the IGAP data set. Since the objective of the study was to find pleiotropic variants for LOAD and MDD, and the MDD data sets did not have any variants close to the magnitude of the APOE level of association (strongest association was P = 2.3 × 10−11), a second set of analyses excluding variants in the APOE region were performed. Variants in the APOE region on chromosome 19, defined as ± 300 Kb of the APOE epsilon coding SNPs (chr19:45,111,942–45,711,941) were excluded. The fold-enrichment plot demonstrated moderate (2.4–7.8-fold) SNP enrichment for LOAD across increasingly stringent levels of significance with the MDD GWAS association (LOAD|MDD) (Fig. 1c). The reverse conditional association (MDD|LOAD) showed enrichment of ~2.0–7.2-fold (Fig. 1d). These results support a moderate level of polygenic overlap between LOAD and MDD. Excluding the SNPs in the APOE region clearly identified a stronger polygenic overlap in the direction LOAD|MDD, with maximal fold enrichment increasing from approximately fourfold (including APOE) to eightfold (excluding APOE), while maximal fold enrichment in the reverse direction, (MDD|LOAD) was similar at sevenfold for analyses that included or excluded the SNPs in the APOE region. These results support the conclusion that including the APOE region for the conditional analyses can potentially mask significant results by establishing a set of APOE SNPs with a significant FDR that offsets other SNPs with FDRs that do not reach the level of the APOE SNPs.

Mendelian randomization analysis

The MR analysis estimated a moderate influence of the LOAD-associated SNPs on risk of MDD: OR = 1.4, 95% confidence limits 1.2–1.7. These results support that the genetic risks associated with Alzheimer’s disease may influence the risk of MDD. To test the sensitivity of the results to horizontal pleiotropy, we performed MR regression. The test for directional horizontal intercept was not significant (P = 0.09).

Specific variants and genes identified by conditional false discovery rate analysis

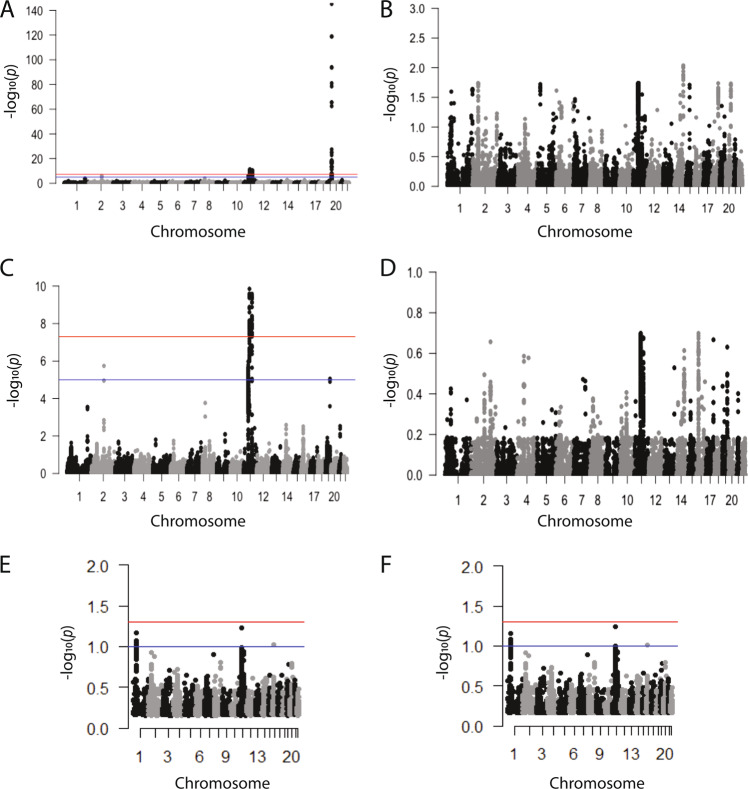

Manhattan plots based on conditional FDR analysis were constructed for data sets including (Fig. 2a, b) and excluding (Fig. 2c, d) the APOE region. The conditional association analysis excluding the APOE region, in which LOAD is conditional on association with MDD, Q(LOAD|MDD), identified a highly significant (FDR Q ≤ 5 × 10−8) cluster of SNPs on chromosome 11. In addition, two SNPs on chromosome 2 and two SNPs on chromosome 19 were identified as significant at a threshold of FDR Q ≤ 1 × 10−5 (Fig. 2c, Table 1). Relaxing the FDR threshold to Q ≤ 0.05 (−log10(Q) = 1.3) resulted in numerous SNPs across the genome (Table 1). The associated SNPs were classified as common characterized by 0.02 ≤ MAF ≤ 0.90. Individual GWAS results for these SNPs were consistent with effect sizes for GWAS studies of complex diseases: LOAD (IGAP): 0.83 ≤ OR ≤ 1.12, 8.67 × 10−5 ≤ P ≤ 3.15 × 10−3; MDD: 0.86 ≤ OR ≤ 1.07, 6.31 × 10−7 ≤ P ≤ 6.14 × 10−4. Mapping the most proximate genes to the associated SNPs defined 40 genes of which 9 have been known as LOAD risk genes via published LOAD-GWAS: BIN1, CELF1, CR1, FERMT2, MS4A6A, PICALM, PTK2B, SORL1, and SPI1.

Fig. 2. Conditional Manhattan plots of the conditional –log10 (FDR) values.

a FDR Q value for SNP association with LOAD conditional with SNP association for MDD. Plot is made for the results from the full genome. b FDR Q value for SNP association with MDD association conditional with SNP association for LOAD. Plot is made for results from the full genome. c FDR Q value for SNP association with LOAD association conditional with SNP association for MDD. Plot is made for the results, excluding SNPs in the APOE-associated region. d FDR Q value for SNP association with MDD association conditional with SNP association for LOAD. Plot is made for the results, excluding SNPs in the APOE-associated region. e conjunction conditional FDR Q value for SNP association with LOAD conditional with SNP association for MDD. Plot is made for the results, including SNPs in the APOE-associated region. f Conjunction conditional FDR Q value for SNP association with MDD conditional with SNP association for LOAD. Plot is made for the results, excluding the APOE-associated region. For panels a–d, genome-wide significant line (red) is drawn at –log10(5 × 10−8), suggestive line (blue) is drawn at −log10(1 × 10−5); for panels e and f, genome-wide significant line (red) is drawn at –log10(0.05), suggestive line (blue) is drawn at –log10(0.1).

Table 1.

Genes reaching statistical significance (FDR ≤ 0.05) for association with LOAD conditional on association with MDD.

| SNP | Chr. | Positiona | Nearest gene | minor allele | MAF | Conditional FDR Q(LOAD|MDD) | LOAD Beta | LOAD Beta SE | LOAD P-value | MDD OR | MDD OR SE | MDD P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs35677603 | 11 | 47,268,310 | ACP2 | T | 0.31 | 1.58E−03 | −0.078 | 0.016 | 4.05E−07 | 0.985 | 0.009 | 8.59E−02 |

| rs3017432 | 21 | 28,147,728 | ADAMTS1 | T | 0.59 | 2.98E−03 | −0.074 | 0.015 | 1.05E−06 | 0.982 | 0.008 | 2.84E−02 |

| rs11823949 | 11 | 47,723,512 | AGBL2 | A | 0.35 | 1.98E−05 | −0.097 | 0.017 | 4.40E−09 | 0.974 | 0.009 | 3.45E−03 |

| rs35589443 | 2 | 127,847,736 | BIN1 | A | 0.03 | 1.43E−03 | −0.265 | 0.052 | 3.65E−07 | 1.047 | 0.027 | 9.53E−02 |

| rs12419692 | 11 | 47,624,714 | C1QTNF4 | A | 0.35 | 2.81E−05 | −0.087 | 0.015 | 7.21E−09 | 0.977 | 0.008 | 5.11E−03 |

| rs1317149 | 11 | 47,486,885 | CELF1 | T | 0.36 | 2.17E−05 | −0.089 | 0.015 | 3.45E−09 | 0.980 | 0.008 | 1.43E−02 |

| rs11576522 | 1 | 207,789,269 | CR1 | A | 0.63 | 2.85E−04 | 0.079 | 0.015 | 6.56E−08 | 1.017 | 0.009 | 5.87E−02 |

| rs11039138 | 11 | 47,249,223 | DDB2 | A | 0.37 | 9.00E−03 | 0.070 | 0.015 | 2.45E−06 | 1.015 | 0.008 | 7.91E−02 |

| rs76184771 | 19 | 18,567,189 | ELL | A | 0.13 | 2.03E−02 | −0.091 | 0.021 | 1.29E−05 | 1.030 | 0.011 | 9.58E−03 |

| rs75010292 | 2 | 55,172,536 | EML6 | A | 0.11 | 2.63E−02 | −0.098 | 0.023 | 1.72E−05 | 0.967 | 0.013 | 7.70E−03 |

| rs17125924 | 14 | 53,391,680 | FERMT2 | A | 0.08 | 2.58E−03 | −0.122 | 0.025 | 6.62E−07 | 1.026 | 0.014 | 5.79E−02 |

| rs4742958 | 9 | 108,411,944 | FKTN | T | 0.14 | 4.44E−02 | −0.128 | 0.030 | 1.56E−05 | 0.967 | 0.016 | 3.21E−02 |

| rs7130758 | 11 | 47,749,960 | FNBP4 | T | 0.36 | 3.27E−05 | −0.088 | 0.015 | 1.01E−08 | 0.978 | 0.009 | 8.73E−03 |

| rs11021857 | 11 | 11,472,193 | GALNT18 | A | 0.07 | 4.92E−02 | 0.122 | 0.030 | 3.68E−05 | 1.049 | 0.017 | 4.60E−03 |

| rs9270208 | 6 | 32,556,402 | HLA-DRB1 | T | 0.68 | 4.29E−02 | −0.077 | 0.018 | 1.49E−05 | 1.016 | 0.009 | 8.02E−02 |

| rs2385088 | 19 | 18,545,540 | ISYNA1 | A | 0.34 | 3.80E−02 | −0.066 | 0.015 | 1.26E−05 | 1.016 | 0.008 | 6.29E−02 |

| rs3859570 | 19 | 18,510,925 | LRRC25 | T | 0.41 | 1.26E−02 | −0.069 | 0.016 | 7.84E−06 | 1.023 | 0.009 | 9.53E−03 |

| rs67871383 | 11 | 47,335,838 | MADD | T | 0.32 | 3.53E−04 | 0.082 | 0.015 | 8.28E−08 | 1.017 | 0.009 | 4.22E−02 |

| rs2047007 | 1 | 40,427,975 | MFSD2A | T | 0.23 | 4.07E−02 | 0.071 | 0.017 | 2.83E−05 | 1.027 | 0.009 | 3.42E−03 |

| rs1125357b | 11 | 59,885,493 | MS4A2 | A | 0.42 | 8.87E−09 | 0.107 | 0.015 | 3.09E−13 | 0.984 | 0.009 | 7.20E−02 |

| rs1026254b | 11 | 60,030,457 | MS4A4A | T | 0.60 | 2.84E−10 | −0.116 | 0.015 | 2.42E−15 | 1.014 | 0.008 | 8.87E−02 |

| rs1582763b | 11 | 60,021,948 | MS4A4E | A | 0.36 | 1.40E−10 | −0.123 | 0.015 | 1.19E−16 | 1.016 | 0.009 | 9.38E−02 |

| rs624663b | 11 | 59,945,065 | MS4A6A | T | 0.56 | 1.33E−08 | 0.104 | 0.014 | 6.34E−13 | 0.984 | 0.008 | 4.91E−02 |

| rs10838738 | 11 | 47,663,049 | MTCH2 | A | 0.35 | 2.56E−05 | 0.087 | 0.015 | 5.99E−09 | 1.025 | 0.008 | 2.82E−03 |

| rs61781278 | 1 | 40,376,741 | MYCL | A | 0.19 | 4.30E−02 | 0.076 | 0.018 | 1.76E−05 | 1.022 | 0.010 | 2.47E−02 |

| rs11605348 | 11 | 47,606,483 | NDUFS3 | A | 0.35 | 3.47E−06 | −0.097 | 0.016 | 4.25E−10 | 0.978 | 0.009 | 8.36E−03 |

| rs7105282 | 11 | 47,805,614 | NUP160 | A | 0.36 | 4.54E−05 | −0.091 | 0.016 | 1.63E−08 | 0.974 | 0.009 | 3.15E−03 |

| rs541458b | 11 | 85,788,351 | PICALM | T | 0.68 | 1.01E−08 | 0.112 | 0.015 | 3.69E−13 | 0.984 | 0.010 | 8.07E−02 |

| rs60075622 | 11 | 47,449,101 | PSMC3 | T | 0.33 | 7.86E−06 | 0.092 | 0.015 | 1.30E−09 | 1.023 | 0.008 | 6.24E−03 |

| rs755951 | 8 | 27,226,790 | PTK2B | A | 0.39 | 1.72E−04 | −0.082 | 0.015 | 3.79E−08 | 1.015 | 0.008 | 6.82E−02 |

| rs7106956 | 11 | 47,458,765 | RAPSN | T | 0.33 | 8.34E−06 | 0.092 | 0.015 | 1.28E−09 | 1.023 | 0.008 | 6.10E−03 |

| rs755554 | 11 | 47,432,034 | SLC39A13 | C | 0.67 | 4.90E−06 | 0.095 | 0.015 | 6.29E−10 | 1.024 | 0.009 | 4.71E−03 |

| rs3781832 | 11 | 121,436,270 | SORL1 | T | 0.10 | 2.89E−02 | −0.098 | 0.022 | 1.09E−05 | 0.972 | 0.013 | 2.53E−02 |

| rs67472071 | 11 | 47,391,745 | SPI1 | A | 0.33 | 1.05E−06 | −0.098 | 0.015 | 1.14E−10 | 0.980 | 0.008 | 1.96E−02 |

| rs7258465 | 19 | 18,533,642 | SSBP4 | T | 0.34 | 3.58E−02 | −0.066 | 0.015 | 1.17E−05 | 1.017 | 0.008 | 4.36E−02 |

| rs7011101 | 8 | 71,501,474 | TRAM1 | A | 0.10 | 1.91E−02 | −0.105 | 0.023 | 5.67E−06 | 1.022 | 0.013 | 9.91E−02 |

| rs4929858 | 11 | 49,070,655 | TRIM64C | A | 0.63 | 2.80E−02 | 0.065 | 0.015 | 1.85E−05 | 1.036 | 0.008 | 1.85E−05 |

| rs61781270 | 1 | 40,349,428 | TRIT1 | A | 0.20 | 2.32E−02 | 0.077 | 0.017 | 7.11E−06 | 1.017 | 0.009 | 7.17E−02 |

| rs66555393 | 8 | 71,628,753 | XKR9 | A | 0.10 | 3.02E−02 | 0.106 | 0.024 | 9.54E−06 | 0.977 | 0.014 | 9.31E−02 |

| rs17376517 | 3 | 44,765,221 | ZNF502 | T | 0.05 | 4.63E−02 | −0.141 | 0.033 | 1.65E−05 | 0.969 | 0.018 | 7.22E−02 |

SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism, MAF minor allele frequency, LOAD late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, MDD major depressive disorder, FDR false discovery rate.

aBuild 37, assembly hg19.

bSNP that were highly significant (FDR Q ≤ 5 × 10−8) in the Q(LOAD|MDD) analysis excluding the APOE and were used for the eQTL analysis (Fig 4b).

The conditional association analysis in the reverse direction, Q(MDD|LOAD), exclusive of APOE region did not identify any SNP with FDR Q ≤ 0.05 (Fig. 2d). The strongest associated SNPs did not overlap with previously known GWAS LOAD loci (Table 2). Mapping genes based on proximity to the SNPs with the strongest conditional association for Q(MDD|LOAD), identified TRMT61A, FOLH1, CKB and PTPRJ and PTPN1.

Table 2.

Genes reaching statistical significance (FDR ≤ 0.05) for association with MDD conditional on association with LOAD.

| SNP | Chr | Positiona | Nearest gene | Minor allele | MAF | Conditional FDR Q(MDD|LOAD) | LOAD Beta | LOAD Beta SE | LOAD P-value | MDD OR | MDD OR SE | MDD P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs35591392 | 14 | 75,157,713 | AREL1 | T | 0.53 | 2.82E–02 | −0.047 | 0.014 | 8.83E−04 | 1.031 | 0.008 | 9.03E−05 |

| rs78563874 | 11 | 85,609,073 | CCDC83 | T | 0.24 | 2.76E–02 | 0.064 | 0.017 | 1.46E−04 | 0.964 | 0.009 | 9.09E−05 |

| rs57105978 | 5 | 26,843,262 | CDH9 | T | 0.03 | 2.02E–02 | 0.109 | 0.036 | 2.61E−03 | 0.930 | 0.019 | 1.20E−04 |

| rs2071408 | 14 | 103,987,078 | CKB | A | 0.37 | 1.44E–02 | 0.049 | 0.015 | 1.12E−03 | 0.961 | 0.009 | 3.09E−06 |

| rs7508819 | 20 | 49,205,320 | FAM65C | T | 0.58 | 1.94E–02 | 0.047 | 0.015 | 1.34E−03 | 1.031 | 0.008 | 1.79E−04 |

| rs202675 | 11 | 49,228,613 | FOLH1 | C | 0.28 | 1.79E–02 | −0.054 | 0.016 | 7.43E−04 | 0.968 | 0.009 | 1.50E−04 |

| rs74018295 | 15 | 57,870,174 | GCOM1 | T | 0.09 | 1.90E–02 | −0.077 | 0.026 | 3.13E−03 | 0.946 | 0.015 | 1.74E−04 |

| rs111666866 | 6 | 32,491,925 | HLA-DRB5 | T | 0.73 | 4.85E–02 | 0.060 | 0.018 | 8.22E−04 | 0.966 | 0.010 | 6.14E−04 |

| rs4900582 | 14 | 104,058,014 | KLC1 | A | 0.64 | 2.48E–02 | 0.052 | 0.016 | 8.84E−04 | 0.969 | 0.009 | 2.68E−04 |

| rs8106047 | 19 | 18,505,741 | LRRC25 | A | 0.16 | 4.31E–02 | 0.068 | 0.023 | 2.82E−03 | 0.941 | 0.014 | 1.30E−05 |

| rs2894221 | 6 | 31,461,771 | MICB | A | 0.36 | 3.79E–02 | −0.047 | 0.015 | 1.75E−03 | 0.968 | 0.008 | 7.42E−05 |

| rs6664244 | 1 | 40,374,386 | MYCL | T | 0.36 | 2.47E–02 | −0.057 | 0.015 | 1.32E−04 | 0.971 | 0.008 | 2.67E−04 |

| rs7103992 | 11 | 48,510,777 | OR4A47 | A | 0.65 | 2.84E–02 | −0.045 | 0.015 | 2.26E−03 | 0.969 | 0.008 | 8.98E−05 |

| rs10838830 | 11 | 48,233,932 | OR4B1 | A | 0.35 | 2.42E–02 | −0.044 | 0.015 | 3.06E−03 | 0.971 | 0.008 | 2.54E−04 |

| rs4312096 | 11 | 48,411,653 | OR4C5 | C | 0.65 | 1.93E–02 | −0.045 | 0.015 | 2.66E−03 | 0.969 | 0.008 | 1.79E−04 |

| rs3009872 | 1 | 66,411,400 | PDE4B | T | 0.43 | 3.87E–02 | 0.044 | 0.014 | 2.05E−03 | 1.028 | 0.008 | 4.68E−04 |

| rs1265099 | 6 | 31,105,413 | PSORS1C1 | A | 0.42 | 3.75E–02 | 0.048 | 0.015 | 1.07E−03 | 1.036 | 0.008 | 8.88E−06 |

| rs6063534 | 20 | 49,189,168 | PTPN1 | T | 0.51 | 1.80E–02 | 0.043 | 0.014 | 2.33E−03 | 1.031 | 0.008 | 1.36E−04 |

| rs12790666 | 11 | 47,983,477 | PTPRJ | A | 0.52 | 1.79E–02 | −0.045 | 0.014 | 1.71E−03 | 0.970 | 0.008 | 1.42E−04 |

| rs12668707 | 7 | 4,414,425 | SDK1 | C | 0.21 | 4.36E–02 | −0.051 | 0.017 | 2.98E−03 | 1.034 | 0.010 | 5.38E−04 |

| rs111653412 | 6 | 3,370,053 | SLC22A23 | T | 0.02 | 2.38E–02 | 0.191 | 0.065 | 3.15E−03 | 0.863 | 0.040 | 2.47E−04 |

| rs10157030 | 1 | 246,184,138 | SMYD3 | T | 0.28 | 2.23E–02 | 0.056 | 0.016 | 5.73E−04 | 1.034 | 0.009 | 2.24E−04 |

| rs6122859 | 20 | 48,610,609 | SNAI1 | A | 0.63 | 3.99E–02 | −0.047 | 0.015 | 2.12E−03 | 0.971 | 0.008 | 4.86E−04 |

| rs7785189 | 7 | 12,257,527 | TMEM106B | T | 0.41 | 3.31E–02 | −0.045 | 0.014 | 1.53E−03 | 1.032 | 0.008 | 7.77E−05 |

| rs4268511 | 11 | 49,046,510 | TRIM49B | A | 0.64 | 1.81E–02 | 0.056 | 0.015 | 2.08E–04 | 1.032 | 0.008 | 1.32E−04 |

| rs7949585 | 11 | 49,077,746 | TRIM64C | T | 0.60 | 2.00E–02 | −0.051 | 0.015 | 6.11E–04 | 0.970 | 0.008 | 1.90E−04 |

| rs911552 | 14 | 103,999,508 | TRMT61A | A | 0.37 | 8.94E–03 | −0.051 | 0.015 | 5.98E–04 | 1.042 | 0.009 | 1.73E–06 |

SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism, MAF minor allele frequency, LOAD late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, MDD major depressive disorder, FDR false discovery rate.

aBuild 37, assembly hg19.

The analyses were repeated for the data that included the APOE region. The conditional association analysis including the APOE region in which LOAD is conditional on association with MDD, Q(LOAD|MDD) showed an extremely strong signal, with FDR Q values ≤ 10−120 for the APOE region on chromosome 19 that was prominent on the Manhattan plot (Fig. 2a). The highly significant (FDR Q ≤ 5 × 10–8) cluster of SNPs on chromosome 11 also remained evident on the plot that included the APOE region. In the reverse condition Q(MDD|LOAD) analysis no SNPs were identified (FDR Q ≤ 1 × 10−5), however, with a relaxed FDR Q ≤ 0.05 (−log10(Q) = 1.3) numerous associated SNPs were found (Fig. 2b). Overall, the analysis of Q(LOAD|MDD) ≤ 0.05 including APOE region identified 458 SNPs representing 40 genes (Supplementary Table S1), where the corresponding analysis of the Q(MDD|LOAD) direction found 545 SNPs representing 27 genes (Supplementary Table S2).

Manhattan plots were also constructed for the conjunction conditional FDR (ccFDR) for the analysis that included the APOE region (Fig. 2e) and for an analysis that excluded the APOE region (Fig. 2f). The strongest association signals for the ccFDR showed marginal statistical significance for SNPs rs4929858 (FDR Q = 0.06) and rs3103780 (FDR Q = 0.07) that are proximal to the genes TRIM49B and MYCL, respectively.

Mapping of genes to pathways and function

Eight out of the nine genes identified through the Q(LOAD|MDD) conditional analysis (FDR Q ≤ 0.05) were also found in LOAD-GWAS. These genes are involved in two major biological pathways and functional classes, immune response and regulation of endocytosis, that were previously implicated in LOAD by pathway analyses of GWAS data sets55. Specifically, CR1, MS4A6A, SPI1, and CELF1 are relevant in immune response, and BIN1, PICALM, SORL1, and PTK2B in regulation of endocytosis.

Next, gene set enrichment was performed for the conditional FDRs in both directions, Q(LOAD|MDD) and Q(MDD|LOAD) using all SNPs. In this analysis, the SNP to gene mapping was limited to 500 kb upstream and downstream of the gene, and the candidate gene sets included canonical pathways, GO biological processes, and GO molecular function. The pathway gene set analysis using the LOAD conditional on MDD results showed the strongest statistical confidence (enrichment FDR < 0.05) for several biological pathways, including calcium channel activity, oxidoreductase activity acting on NLOADH or NLOADPH, receptor-mediated endocytosis, and phospholipid binding (Supplementary Table S3), following by hematopoietic cell lineage pathway with enrichment FDR = 0.04. The pathway mapping results for the receptor-mediated endocytosis were based on strong associations with 12 genes, from PICALM and SORL1 that demonstrated the strongest effects, to DMN1, IGF2R, and SFTPD with weaker effects.

The significant pathways (FDR Q ≤ 0.05) identified using the results of the MDD conditional with LOAD represent a broad set of regulatory pathways, including leukocyte transendothelial migration, adherens junction, and purine metabolism (Supplementary Table S4). Notably, neurological system processes were identified as FDR significant (P ≤ 0.05).

Two genes showed association trends in the ccFDR analysis. One of which, TRIM49B, is a member of the TRIM family proteins which has a role in the innate immunity56, providing further evidence for the involvement of the immune system in LOAD.

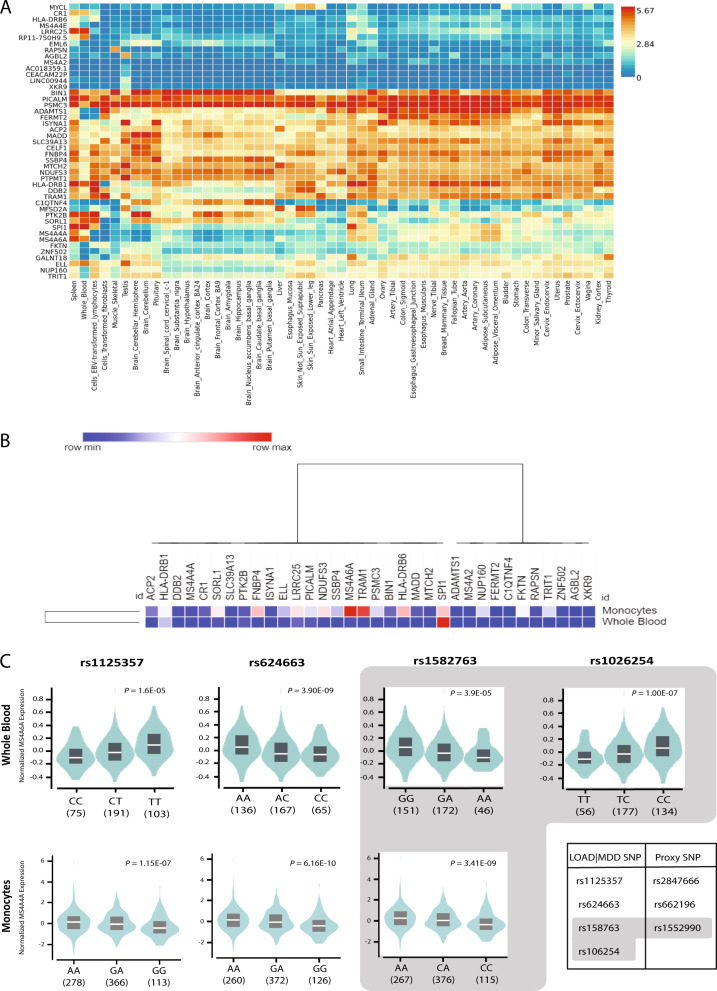

Gene expression analysis in brain

The tissue-specific gene expression for the 62 genes mapped by proximity to the SNPs identified in conditional association for Q(LOAD|MDD) was evaluated in 53 GTEx tissues (Fig. 3a). Fifty-three out of the total 62 genes were mapped to unique Entrez GeneID numbers, and are displayed in the heatmap. The heatmap was ordered by both gene and tissue clustering and denoted 13 brain-specific tissues. The BIN1, PICALM, and PSMC2 genes showed high (5.7) levels of expression in the 13 brain tissues relative to all other genes. MS4A4A, MS4A6A, and SPI1 showed a consistent, low expression level (~1.4) in the 13 brain tissues. MTCH2, SSBP4, and PTPMT1 showed a consistent, moderate expression level (4.2) in all 13 brain tissues (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3. Gene expression and eQTL analysis for genes associated with LOAD conditional on association with MDD.

a Heatmap plot of tissue-specific gene expression data in 53 GTEx tissue types for the 53 genes identified by proximity mapping for SNP association with LOAD, conditional with SNP association with MDD. There are 13 brain-specific tissues highlighted in the heatmap, which was ordered by both gene and tissue clustering. b Heatmap plot of expression levels of 53 genes in whole blood from the GTEx portal and in monocyte data from the Cardiogenics study. c Violin plots for eQTL analysis results in whole blood (upper panel) and in monocytes (lower panel) for SNPs identified as significant (FDR Q ≤ 5 × 10−8) for the association with LOAD conditional with association for MDD (Supplementary Table S5).

eQTL analysis in myeloid lineage

We evaluated the set of 53 genes for expression levels in whole blood from the GTEx portal and for expression levels in monocyte data from the Cardiogenics study53. Only 34 genes had expression data in both dataset resources. We found six genes, including MS4A6A and SPI1, with high levels of expression relative to other genes in whole blood and in monocytes (Fig. 3b). The level of SPI1 expression was higher than other genes in the set for the two tissues. The level of expression of MS4A6A was uniquely higher in monocytes than in whole blood (Fig. 3b).

Next, we performed an eQTL analysis for the five highly significant SNPs (FDR Q ≤ 5 × 10−8) on chromosome 11 (Table 2—marked in*; Supplementary Table S5), and found significant associations between the four SNPs clustered at the MS4A locus and mRNA levels of MS4A6A gene in whole blood (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Table S5). These four SNPs were not available in the monocytes expression data set; therefore, we conducted the eQTL analysis using proxy SNPs (D’ = 1, R2 > 0.9, Supplementary Table S5), and identified associations for all proxies with MS4A4A expression in monocytes (P < 5.4 × 10−7, Fig. 3c; Supplementary Table S5). SNP rs541458, proximal to PICALM, showed no significant eQTL signals in whole blood or in monocytes. SNP rs67472071 in the vicinity of SPI1 was the next significantly associated with LOAD conditional on MDD (FDR Q = 1 × 10−6). We extended the eQTL analyses and found associations between this SNP and the expression of the regional MYBPC3 and C1QTNF4 genes in whole blood, and between its proxy and MYBPC3 expression in monocytes (Supplementary Table S5).

Discussion

This study represents the first step toward deciphering the genetic heterogeneity of NPS in LOAD, and in particular the comorbidity of depression and LOAD. The conditional FDR (cFDR) approach we undertook in this study was to identify genetic variants and genes that are associated with LOAD conditional on an association with MDD and vice versa. The cFDR approach showed clear precedent in a study that investigated overlap in variants associated with LOAD and plasma levels of c-reactive protein (CRP), low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride. This previous study found polygenic overlap between LOAD and systemic inflammation measured by CRP and plasma lipids28. Moreover, by conditioning the LOAD association on inflammation and lipids phenotypes, they identified novel loci that were not reported in large LOAD case–control studies, and provided new insights into the involvement of pathways related to systemic inflammation, plasma lipids, and LOAD28. Similarly, another recent study examined the polygenic overlap between cognitive impairment and plasma CRP and lipids. They found an enrichment for SNPs associated with cognitive impairment conditional on plasma CRP and lipids, and significant associations for the APOE extended locus36. Shared genetic etiology for LOAD using the cFDR method was also investigated for Type 2 diabetes (T2D)37. In this study, multiple known and novel associated SNPs were identified by conditioning LOAD association on T2D and by the reverse direction, and mitochondrial dysfunction was highlighted as a common pathway37. The approach has been also utilized more broadly to examine genetic pleiotropy between multiple diverse diseases and phenotypes including schizophrenia and cognitive traits29, bipolar disorder27, multiple sclerosis26, cardiovascular disease risk factors25, and educational attainment30. Additional diseases and phenotypes to which the approach has been applied include Parkinson’s disease and autoimmune diseases31, blood lipids, immune-related diseases32 and more33–35. Collectively, using multiple disorders with overlapping phenotypes in genetic association studies allows the identification of shared genetic variants, genes, and pathways, which in turn elucidate common pathobiology and molecular mechanisms across disorders. Furthermore, conditioning genetic associations on multiple phenotypes is crucial to the discovery of novel loci that otherwise would not be identified via conventional case–control design.

In this study, we demonstrated shared genetic etiologies between LOAD and MDD. We observed a moderate enrichment for SNPs associated with LOAD across increasingly stringent levels of significance with MDD GWAS association, as well as in the reverse direction. Mendelian randomization analysis supported a potential causal relationship between the significant LOAD SNPs with MDD; this relationship was not a consequence of horizontal pleiotropy. In addition, we identified numerous associated SNPs and the biological interpretation of the corresponding genes pinpointed the immune response and regulation of endocytosis as common pathways. In contrast, Gibson et al. previously assessed overlapping polygenic architecture for LOAD and MDD and found no evidence for pleiotropy between these disorders38. These divergent outcomes may be explained by the different methodology used to investigate shared genetic between LOAD and MDD; while we applied a cFDR framework to detect genetic pleiotropy, the previous publication used LD score regression and polygenic risk score analysis. Alternatively, the different MDD cohorts from different countries may have been recruited using distinctive case diagnostic criteria, that may be anticipated given the arbitrary threshold criteria applied to clinical diagnosis of depression.

The LOAD genetic association analysis conditional on MDD Q(LOAD|MDD) showed an enrichment of SNPs on chromosome 11 with strong level of significance (Table 1). These SNPs are mapped predominantly in two major clusters on chromosome 11 that include genes previously implicated in LOAD–GWAS16,20. The first cluster features the CELF1 and SPI1 genes; while CELF1 was the most proximate gene to the LOAD-SNP at this locus, SPI1 was recently suggested as a stronger candidate causal gene for LOAD based on functional lines of evidence57. SPI1 encodes PU.1, a transcription factor that is critical for myeloid cell development and function. A recent study reported an association between a SNP in the SPI1 gene, rs1057233, and LOAD age of onset57. In addition, they performed an eQTL analysis and found that this SNP is associated with SPI1 expression in monocytes and macrophages, suggesting that the encoded PU.1 may be a master regulator for the expression of multiple LOAD genes in myeloid cells57. Last, overexpression and downregulation of PU.1 in mouse microglial cells affected phagocytic activity and the expression of mouse orthologs of several LOAD risk genes. Based on these observations, we analyzed the linkage disequilibrium region of the SPI1 locus. The SNP rs67472071 proximate to SPI1 showed a conditional association for LOAD [Q(LOAD|MDD, FDR = 1.05 × 10−6)]. rs67472071 is located 15,297 base pairs from rs1057233 and is a proxy (R2 = 0.95 and D’ = 1) for this reported functional LOAD SNP rs105723357. The second cluster of LOAD conditional MDD-associated SNPs encompasses the membrane-spanning 4-domains subfamily A (MS4A) genes region that encodes proteins with strong expression in the hematopoietic system. A new study integrated LOAD–GWAS with myeloid epigenomic and transcriptomic data sets to define candidate LOAD-risk enhancers in myeloid cells and their linked target causal genes58. By fine mapping of a candidate myeloid enhancer linked to the MS4A locus, they identified candidate functional SNP rs636317-T in the MS4A locus that affected the expression of MS4A6A, and validated it experimentally in human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived microglia58. Consistent with this finding, our eQTL analysis showed that the cluster of SNPs at the MS4A locus are associated with the expression of MS4A6A in whole blood. Notable, in monocytes we showed that these SNPs were eQTLs for the adjacent MS4A4A. To further support the functional relevance of our finding, we examined the high LD region of the MS4A genes cluster, and found that two of the conditional LOAD-associated SNPs in this region, rs1582763 (proximal to MS4A4E) and rs1026254 (MS4A4A) located 2,798 and 11,307 base pairs away from the functional candidate SNP-rs636317, respectively, are proxies for this reported functional candidate SNP (R2 = 0.85 and D’ = 1, R2 = 1 and D’ = 1, respectively). Thus, the integrated data implies biological significance for the LOAD and MDD pleiotropic variants on chromosome 11 related to expression regulation in myeloid cells such as microglia.

Genetic studies implicated several genes on chromosome 11, including the MS4A cluster, SPI1, and CELF1, in both LOAD and MDD (GWAS summary statistics in Table 1). As discussed above, we identified LOAD and MDD pleiotropic variants proximal to these genes. The broader pleiotropic nature of these genes has not been studied extensively. A comprehensive literature search showed that these genes are also involved in non-neurological diseases (Supplementary Table S6). Interestingly, all of these neurological and non-neurological diseases are related, to varying extents, to the immune system. We interpret that the relationships of these genes to the various diseases may be exerted via their roles in immune response.

Our results warrant further in-depth investigations in several areas: (1) Confidence in the genetic association results is increased by the conditional association of two independent phenotypes, nevertheless future studies using replication cohorts will provide additional support to the results. (2) The conditional FDR framework identified associations of variants with the phenotypes. To advance our understanding of the causality, in this study we identified overlaps with eQTLs and suggested biological roles of the associated variants in regulation of gene expression. However, causality for the specific biological pathways would require validation studied using gene editing experiments in model systems. (3) Mapping of the associated SNPs to genes was inferred by proximity; other more distal relationships of the variants with genetic enhancers, for example, are important and ought to be evaluated experimentally using methods, such as Hi-C, to determine topographical associated domains (TAD). (4) The conditional FDR framework utilizes GWAS summary statistics from well-replicated consortium studies. Imputation of SNPs performed in these studies is based on 1000 Genomes reference panels, as is the pruning of SNPs by LD in the conditional FDR approach. Several studies have pointed to the limitations of using LD measures based on the 1000 genomes reference panel for genetic analysis using summary statistics, including conditional analysis, gene-based testing, fine mapping, and polygenic risk prediction59–61. As larger reference panels (e.g. Haplotype Reference Consortium62) and updated GWAS summary statistics based on these panels become available, the conditional analysis should also be updated.

In this study, we focused on LOAD and MDD to exemplify the concept of pleiotropy between two disorders that shared NPS. The results of this study provide a proof of concept for future work extending the evaluation of shared genetic etiology between LOAD and additional neuropsychiatric conditions that present comorbid NPS similar to those that manifest in LOAD. Moreover, further investigations are warranted to determine whether our observations are specific to LOAD and MDD, or can be generalized to other complex neuropsychiatric disorders with shared NPS.

In conclusion, the outcomes of this study have several important implications to LOAD genetic architecture, including the demonstration of genetic pleiotropy effects between LOAD and MDD, identification of new LOAD loci, and validation of LOAD pathways. Furthermore, our data propose a genetic interpretation of the heterogeneity of depression in LOAD. These findings are important for the development of actionable targets for novel therapies to treat depression preceding dementia, in an effort to delay or ultimately prevent the onset of LOAD.

Supplementary information

Supplement Figure legends and Table titles

Figure S1. Manhattan plots of the GWAS results for LOAD and MDD.

Figure S2. Q-Q plots of the GWAS results for LOAD and MDD.

Supplemental Table S1. Summary statistics for analysis of LOAD conditional on MDD.

Supplemental Table S2. Summary statistics for analysis of MDD conditional on LOAD.

Supplemental Table S3. Pathway analysis for LOAD conditional on MDD.

Supplemental Table S4. Pathway analysis for MDD conditional on LOAD.

Supplemental Table S5. eQTL analysis of the top significant LOAD|MDD associated SNPs in whole blood and monocytes.

Supplemental Table S6. Diseases involved the top significant LOAD|MDD proximal genes.

Acknowledgements

We thank the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project (IGAP) for providing summary results data for these analyses. The investigators within IGAP contributed to the design and implementation of IGAP and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. IGAP was made possible by the generous participation of the control subjects, the patients, and their families. The i–Select chips was funded by the French National Foundation on Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. ELOADI was supported by the LABEX (laboratory of excellence program investment for the future) DISTALZ grant, Inserm, Institut Pasteur de Lille, Université de Lille 2 and the Lille University Hospital. GERLOAD/PERLOADES was supported by the Medical Research Council (Grant n° 503480), Alzheimer’s Research UK (Grant n° 503176), the Welcome Trust (Grant n° 082604/2/07/Z), and German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF): Competence Network Dementia (CND) grant n° 01GI0102, 01GI0711, and 01GI0420. CHARGE was partly supported by the NIH/NIA grant R01 AG033193 and the NIA AG081220 and AGES contract N01–AG–12100, the NHLBI grant R01 HL105756, the Icelandic Heart Association, and the Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University. ADGC was supported by the NIH/NIA grants: U01 AG032984, U24 AG021886, U01 AG016976, and the Alzheimer’s Association grant ADGC–10–196728. We thank the Cardiogenics funded by the European Union FP6 program (European Project reference LSHM-CT-2006-037593) project for providing expression data from monocytes. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health, and by NCI, NHGRI, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, and NINDS. The data used for the analyses described in this paper were obtained from the GTEx Portal on 07/01/2019. We also thank Mr. Young Yun for his assistance on the graphical design of the figures in this paper. This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Aging (NIH/NIA) [R01 AG057522 to O.C.-F.].

Data availability

LOAD GWAS summary statistics: https://www.niagads.org/igap-rv-summary-stats-kunkle-p-value-data

MDD GWAS summary statistics: https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/results-and-downLOADs/mdd/

Code availability

We have used the software cited in this paper with default parameters or minor changes, nonetheless, code for these analyses is available upon request.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-020-0769-y).

References

- 1.Lyketsos CG. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: overview and measurement challenges. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2015;2:155–156. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2015.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyketsos CG, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao QF, et al. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect Disord. 2016;190:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallikainen I, et al. The progression of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease during a five-year follow-up: Kuopio ALSOVA study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61:1367–1376. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson RS, et al. Depressive symptoms, cognitive decline, and risk of AD in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59:364–370. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gatz JL, Tyas SL, St John P, Montgomery P. Do depressive symptoms predict Alzheimer’s disease and dementia? J. Gerontol. 2005;60:744–747. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.6.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saczynski JS, et al. Depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: the Framingham Heart Study. Neurology. 2010;75:35–41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e62138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devanand DP, et al. Depressed mood and the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in the elderly living in the community. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1996;53:175–182. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830020093011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger AK, Fratiglioni L, Forsell Y, Winblad B, Backman L. The occurrence of depressive symptoms in the preclinical phase of AD: a population-based study. Neurology. 1999;53:1998–2002. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vermeulen, T. et al. Cognitive deficits in older adults with psychotic depression: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry10.1016/j.jagp.2019.07.011 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Jorm AF. History of depression as a risk factor for dementia: an updated review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2001;35:776–781. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, John V, Loewenstein D. Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63:530–538. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ni H, et al. The GWAS risk genes for depression may be actively involved in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64:1149–1161. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitzlerova E, et al. Interactions among polymorphisms of susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease or depressive disorder. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018;24:2599–2619. doi: 10.12659/MSM.907202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arlt S, et al. Genetic risk factors for depression in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2013;10:72–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert J-C, et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1452–1458. doi: 10.1038/ng.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naj AC, et al. Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:436–441. doi: 10.1038/ng.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harold D, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1088–1093. doi: 10.1038/ng.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hollingworth, P. et al. Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet.43, 429–435 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Jansen IE, Savage JE, Watanabe K, Bryois J, Williams DM, Steinberg S, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathwaysinfluencing Alzheimer's disease risk. Nat Genet. 2019;51:404–413. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0311-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marioni RE, Harris SE, Zhang Q, McRae AF, Hagenaars SP, Hill WD, et al. GWAS on family history of Alzheimer's disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:99. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0150-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunkle BW, et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Abeta, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:414–430. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0358-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CONVERGE Consortium. Sparse whole-genome sequencing identifies two loci for major depressive disorder. Nature523, 588–591 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Hyde CL, et al. Identification of 15 genetic loci associated with risk of major depression in individuals of European descent. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1031–1036. doi: 10.1038/ng.3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andreassen OA, et al. Improved detection of common variants associated with schizophrenia by leveraging pleiotropy with cardiovascular-disease risk factors. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andreassen OA, et al. Genetic pleiotropy between multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia but not bipolar disorder: differential involvement of immune-related gene loci. Mol. Psychiatry. 2015;20:207–214. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andreassen OA, et al. Improved detection of common variants associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder using pleiotropy-informed conditional false discovery rate. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desikan RS, et al. Polygenic overlap between C-reactive protein, plasma lipids, and Alzheimer disease. Circulation. 2015;131:2061–2069. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smeland, O. B. et al. Identification of genetic loci jointly influencing schizophrenia risk and the cognitive traits of verbal-numerical reasoning, reaction time, and general cognitive function. JAMAPsychiatry10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1986 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Le Hellard S, et al. Identification of gene loci that overlap between schizophrenia and educational attainment. Schizophr. Bull. 2017;43:654–664. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witoelar A, et al. Genome-wide pleiotropy between Parkinson disease and autoimmune diseases. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:780–792. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andreassen OA, et al. Abundant genetic overlap between blood lipids and immune-mediated diseases indicates shared molecular genetic mechanisms. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0123057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andreassen OA, et al. Identifying common genetic variants in blood pressure due to polygenic pleiotropy with associated phenotypes. Hypertension. 2014;63:819–826. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu JZ, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related disease regions identifies nine new risk loci for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:670–675. doi: 10.1038/ng.2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andreassen OA, et al. Shared common variants in prostate cancer and blood lipids. Int J. Epidemiol. 2014;43:1205–1214. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lutz MW, et al. Analysis of pleiotropic genetic effects on cognitive impairment, systemic inflammation, and plasma lipids in the Health and Retirement Study. Neurobiol. Aging. 2019;80:173–186. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang XF, et al. Linking Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes: novel shared susceptibility genes detected by cFDR approach. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017;380:262–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibson J, et al. Assessing the presence of shared genetic architecture between Alzheimer’s disease and major depressive disorder using genome-wide association data. Transl. Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1094. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wray NR, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:668–681. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0090-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat. Med. 1990;9:811–818. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.North TL, et al. Using genetic instruments to estimate interactions in Mendelian randomization studies. Epidemiology. 2019;30:e33–e35. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pierce BL, Burgess S. Efficient design for Mendelian randomization studies: subsample and 2-sample instrumental variable estimators. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013;178:1177–1184. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hemani, G. et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. eLife7, 10.7554/eLife.34408 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Walker VM, et al. Using the MR-Base platform to investigate risk factors and drug targets for thousands of phenotypes. Wellcome Open Res. 2019;4:113. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15334.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J. Epidemiol. 2015;44:512–525. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kent WJ, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chelala C, Khan A, Lemoine NR. SNPnexus: a web database for functional annotation of newly discovered and public domain single nucleotide polymorphisms. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:655–661. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dayem Ullah AZ, Lemoine NR, Chelala C. A practical guide for the functional annotation of genetic variations using SNPnexus. Brief. Bioinform. 2013;14:437–447. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbt004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang K, Cui S, Chang S, Zhang L, Wang J. i-GSEA4GWAS: a web server for identification of pathways/gene sets associated with traits by applying an improved gene set enrichment analysis to genome-wide association study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W90–W95. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watanabe K, Taskesen E, van Bochoven A, Posthuma D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.GTEx Consortium. Human genomics. The genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science348, 648–660 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.GTEx Consortium. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature550, 204–213 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Garnier S, et al. Genome-wide haplotype analysis of cis expression quantitative trait loci in monocytes. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Machiela MJ, Chanock SJ. LDlink: a web-based application for exploring population-specific haplotype structure and linking correlated alleles of possible functional variants. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3555–3557. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pimenova AA, Raj T, Goate AM. Untangling genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;83:300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ozato K, Shin DM, Chang TH, Morse HC., III. TRIM family proteins and their emerging roles in innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:849–860. doi: 10.1038/nri2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang KL, et al. A common haplotype lowers PU.1 expression in myeloid cells and delays onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:1052–1061. doi: 10.1038/nn.4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Novikova, G. et al. Integration of Alzheimer’s disease genetics and myeloid genomics reveals novel disease risk mechanisms. Preprint at 10.1101/694281 (2019).

- 59.Pasaniuc B, Price AL. Dissecting the genetics of complex traits using summary association statistics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017;18:117–127. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deng Y, Pan W. Improved use of small reference panels for conditional and joint analysis with GWAS summary statistics. Genetics. 2018;209:401–408. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.300813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Benner C, et al. Prospects of fine-mapping trait-associated genomic regions by using summary statistics from genome-wide association studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;101:539–551. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McCarthy S, et al. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1279–1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement Figure legends and Table titles

Figure S1. Manhattan plots of the GWAS results for LOAD and MDD.

Figure S2. Q-Q plots of the GWAS results for LOAD and MDD.

Supplemental Table S1. Summary statistics for analysis of LOAD conditional on MDD.

Supplemental Table S2. Summary statistics for analysis of MDD conditional on LOAD.

Supplemental Table S3. Pathway analysis for LOAD conditional on MDD.

Supplemental Table S4. Pathway analysis for MDD conditional on LOAD.

Supplemental Table S5. eQTL analysis of the top significant LOAD|MDD associated SNPs in whole blood and monocytes.

Supplemental Table S6. Diseases involved the top significant LOAD|MDD proximal genes.

Data Availability Statement

LOAD GWAS summary statistics: https://www.niagads.org/igap-rv-summary-stats-kunkle-p-value-data

MDD GWAS summary statistics: https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/results-and-downLOADs/mdd/

We have used the software cited in this paper with default parameters or minor changes, nonetheless, code for these analyses is available upon request.