Abstract

Propionibacterium freudenreichii is a beneficial bacterium widely used in food as a probiotic and as a cheese-ripening starter. In these different applications, it is produced, dried, and stored before being used. Both freeze-drying and spray-drying were considered for this purpose. Freeze-drying is a discontinuous process that is energy-consuming but that allows high cell survival. Spray-drying is a continuous process that is more energy-efficient but that can lead to massive bacterial death related to heat, osmotic, and oxidative stresses. We have shown that P. freudenreichii cultivated in hyperconcentrated rich media can be spray-dried with limited bacterial death. However, the general stress tolerance conferred by this hyperosmotic constraint remained a black box. In this study, we modulated P. freudenreichii growth conditions and monitored both osmoprotectant accumulation and stress tolerance acquisition. Changing the ratio between the carbohydrates provided and non-protein nitrogen during growth under osmotic constraint modulated osmoprotectant accumulation. This, in turn, was correlated with P. freudenreichii tolerance towards different stresses, on the one hand, and towards freeze-drying and spray-drying, on the other. Surprisingly, trehalose accumulation correlated with spray-drying survival and glycine betaine accumulation with freeze-drying. This first report showing the ability to modulate the trehalose/GB ratio in osmoprotectants accumulated by a probiotic bacterium opens new perspectives for the optimization of probiotics production.

Keywords: Osmoadaptation, Spray-drying, Propionibacteria, Viability, Stress, Cross-protection

Introduction

Propionibacterium freudenreichii is a generally-recognized-as-safe (GRAS), food-grade, beneficial bacterium with QPS status (EFSA experts 2008). It is used as a multi-purpose starter in the dairy and probiotic industry (Thierry et al. 2011). Its technological applications include Swiss-cheese manufacturing and production of antimicrobial molecules and of nutritional molecules (Rabah et al. 2017). Its obligatory fermentative metabolism leads to the production of the beneficial short-chain fatty acids, acetate, and propionate, as final products, concomitantly with the release of vitamins B9 (folate) and B12 (cobalamin) and of the bifidogenic compounds, DNA (1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphtoic acid) and ACNQ (2-amino-3-carboxy-1,4-naphthoquinone) (Rabah et al. 2017). This led P. freudenreichii to be described as a nutraceutical producer (Hugenholtz et al. 2002). Consumption of selected strains of P. freudenreichii modulates the gut microbiota in the context of colitis as well as in healthy conditions (D. Bouglé et al. 1999; Hojo et al. 2002; Seki et al. 2004; Mitsuyama et al. 2007). This microbiota modulation, in favor of symbiont bifidobacteria and at the expense of pathobiont Bacteroides, depends on the release of the bifidogenic small molecules, DHNA and ACNQ, by propionibacteria (Isawa et al. 2002). P. freudenreichii modulates the mucosal immune response. It was shown to induce production of anti-inflammatory cytokines in immune (Foligne et al. 2010) and epithelial (Rabah et al. 2018) human cells, although the intensity of this induction varies with the strain studied (Foligné et al. 2013). Accordingly, consumption of P. freudenreichii protected animals from inflammatory intestinal disease induced by TNBS (2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid) (Foligne et al. 2010; Plé et al. 2015, 2016), by DSS (Dextran Sodium Sulfate) (Okada et al. 2006b), by NSAID (Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) (Okada et al. 2006a), and by 5-FU (5-fluorouracil) (Cordeiro et al. 2018). Pilot studies also reported a healing effect in the context of ulcerative colitis in humans (Mitsuyama et al. 2007; Okada et al. 2006b). The release of propionibacterial metabolites in contact with intestinal epithelial cells was further shown to favor apoptotic depletion of cancer cells in vitro (Jan et al. 2002; Lan et al. 2007; Cousin et al. 2016) and in animals (Lan et al. 2008), which may enhance the efficacy of available treatments aimed at preventing or treating digestive cancers (Cousin et al. 2016). To trigger such beneficial effects in the digestive tract, it is crucial for propionibacteria to be consumed alive, which closely depends on the drying technology used.

We have recently shown that although normal laboratory cultures of P. freudenreichii experience massive cell death upon spray-drying, growth in hyperconcentrated sweet whey dramatically enhances its survival during this stressful process. Sweet whey constitutes a very rich and complex growth medium that was used in a four- to five-time concentrated hypertonic form in this study. Growth of P. freudenreichii in such medium triggered complex and diverse modifications within propionibacteria including changes in morphology; overexpression of stress proteins including ClpB, SodM, EF-Tu, and Hsp20; and accumulation of storage compounds including glycogen and polyphosphate (Huang et al. 2016c). During osmoadaptation, P. freudenreichii is able to accumulate trehalose, glycine betaine, and glutamate (Gaucher et al. 2019). Trehalose accumulation has already been reported to protect bacteria during freeze-drying (Termont et al. 2006) and glycine betaine accumulation can have a positive or negative impact on drying depending on the bacterial species (Saarela et al. 2005; Sheehan et al. 2006; Bergenholtz et al. 2012). However, tolerances conferred by each osmoprotectants are not well known. Owing to the great complexity of the hyperconcentrated sweet whey growth and drying medium, the mechanisms triggered that lead to general stress tolerance remained a black box. In particular, the nature and the amount of the different osmoprotectants accumulated were poorly addressed. Indeed, different osmoprotectants may be accumulated, with different impacts on tolerance acquisition.

In this study, we modulated P. freudenreichii growth conditions by changing concentrations of available carbohydrates (CH) and non-protein nitrogen (NPN). We monitored osmoprotectant accumulation and stress tolerance acquisition. Changing the ratio between CH and NPN during growth under osmotic constraint modulated the ratio between glycine betaine (GB) and trehalose. This, in turn, affected P. freudenreichii tolerance towards different stresses, towards freeze-drying, and towards spray-drying. This is, to our knowledge, the first report showing the ability to modulate the trehalose/GB ratio in osmoprotectants accumulated by a probiotic bacterium, in order to enhance drying efficacy. It opens new perspectives for the optimization of freeze-drying and spray-drying processes.

Materials and methods

Growth media and P. freudenreichii growth

Propionibacterium freudenreichii CIRM-BIA 129 (equivalent ITG P20) was provided, stored, and maintained by the CIRM-BIA Biological Resource Center (Centre International de Ressources Microbiennes-Bactéries d’Intérêt Alimentaire, INRA, Rennes, France). P. freudenreichii is routinely cultivated in yeast extract lactate (YEL) medium (Malik et al. 1968). P. freudenreichii CIRM-BIA 129 was grown in different media: laboratory medium—YEL medium, YEL medium with 0.9 M NaCl (YEL+NaCl), YEL medium with 34 g L−1 of lactose (YEL+lactose), and YEL medium with 34 g L−1 of lactose and 0.9 M NaCl (YEL+lactose+NaCl); and in dairy-type medium—sweet whey (SW), sweet whey with 0.7 M NaCl (SW+NaCl), milk ultrafiltrate (MU), and milk ultrafiltrate with 0.7 M NaCl (MU+NaCl). NPN was determined as previously described (Gripon et al. 1975) and total nitrogen (TN) was determined using the Ogg 1960). Osmolarity and growth medium composition are reported in Table 1. Bacterial populations were monitored by optical density (OD) at 650 nm. Salt concentrations are the highest concentrations that enable P. freudenreichii growth in the different media.

Table 1.

Composition and osmotic pressures of the different culture media

| YEL | YEL+NaCl (0.9 M) | YEL+L | YEL+L+NaCl (0.9 M) | MU | MU+NaCl (0.7 M) | SW | SW+NaCl (0.7 M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharides (lactose) (g L−1) | 0 | 0 | 34 | 34 | 48 | 48 | 33.4 | 33.4 |

| Nitrogen total (g L−1) | 14.6 | 14.6 | 14.6 | 14.6 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 4.2 |

| Non-protein nitrogen (NPN) (g L−1) | 14.2 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 1.6 |

| Lactose/NPN | 0 | 0 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 32 | 32 | 167 | 20.9 |

| Osmotic pressure (osmol) | 0.308 | 2.028 | 0.406 | 2.175 | 0.259 | 1.996 | 0.192 | 1.903 |

YEL: yeast extract lactate. L: lactose. MU: milk ultrafiltrate. SW: sweet whey

Identification and quantification of osmoprotectants accumulated by P. freudenreichii CIRM-BIA 129

Extraction of accumulated osmoprotectants

P. freudenreichii CIRM-BIA 129 was grown in the different media. During the exponential phase (OD = 0.8), cells were harvested by centrifugation (8000g, 10 min, 30 °C). Osmoprotectants were then extracted as previously described (Gaucher et al. 2019). Cells were washed twice in a NaCl solution with the same osmolality as the culture medium. Cells were then re-suspended in 2 mL of distilled water, and 8 mL of ethanol absolute were then added. The suspension was homogenized and centrifuged (8000g, 10 min, 30 °C) in order to remove cell fragments. The supernatant extract was evaporated for 7 h with a rotary evaporator (Hei-VAP value Digital, Heidolph). Dried extracts were then solubilized in deuterium oxide (Sigma-Aldrich, USA).

Nuclear magnetic resonance analyses

Osmoprotectants were then identified and quantified by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) as previously described for other bacteria. All 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 298 K on a Bruker Avance 500 spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm TCI triple-resonance cryoprobe (PRISM Core Facility, Rennes). 1H spectra were acquired with a 6-kHz spectral width, 32 K data points, and a total repetition time of 6.73 s. 13C spectra were acquired using a proton power-gated decoupling sequence with a 30° flip angle, a 30-kHz spectral width, 64 K data points, and a total repetition time of 3.08 s. The data were processed with Topspin software (Bruker Biospin). Before applying the Fourier transform, free induction decays of 1H spectra were treated with an exponential broadening of 0.3 Hz.

Samples were solubilized in D2O (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). 3-(Trimethylsilyl)propionic-2,2,3,3-d4 acid sodium salt (TSP-d4) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) served as an internal reference for 1H and 13C chemical shifts. The relative concentration of trehalose, glutamate, and glycine betaine in the samples was determined by the integration of the peaks areas of their 1H signals relative to the internal standard TMSP.

Stress challenges

Heat, oxidative, bile salt, and acid challenges were applied to cultures at the beginning of the stationary phase (when maximal OD was reached). The heat challenge was performed by placing 2 mL (in a 15-mL Falcon tube) of P. freudenreichii culture in a water bath for 10 min at 60 °C, corresponding to the spray-drying temperature (Leverrier et al. 2004). The oxidative challenge was applied by adding 1.25 mM of hydrogen peroxide (Labogros, France) to 2 mL of P. freudenreichii culture for 1 h at 30 °C (Serata et al. 2016). The acid challenge was applied by re-suspending P. freudenreichii in culture medium adjusted to pH 2.0 by using HCl at 30 °C followed by a 1-h incubation (Jan et al. 2000). The bile salt challenge was performed by adding 1 g L−1 of a bile salt mixture (an equimolar mixture of cholate and desoxycholate; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO, USA) to the culture for 1 h at 37 °C (Leverrier et al. 2003). CFU counting was performed after the challenge. In order to calculate the survival percentage, a CFU counting was made on untreated culture left for the same length of time at 30 °C (for the heat, oxidative, and acid challenges) or 37 °C (for the bile salt challenge) as a control.

Spray-drying and powder storage

Spray-drying was performed on a laboratory-scale spray-dryer (Mobile Minor™, GEA Niro, Denmark). P. freudenreichii was cultivated in the different YEL media. At the beginning of the stationary phase, cells were harvested by centrifugation (8000g, 20 min, 30 °C) and re-suspended in a maltodextrin solution (DE = 6–8) (Roquette, France). In the bacterial solution obtained, maltodextrin concentration was 20% of the dry matter, whereas the bacterial concentration was 4% of the dry matter. These different suspensions (∼ 2 L) of P. freudenreichii were agitated for 10 min prior to delivery to the dryer by a peristaltic pump (520S, Watson-Marlow, France). A two-fluid nozzle with a diameter of 0.8 mm was used for atomization. The inlet air temperature was fixed at 160 °C. The temperature outlet air was controlled at 60 ± 2 °C, by adjusting the feed rate. The bacterial viabilities were estimated by numeration on YEL agar plates incubated at 30 °C before and after spray-drying, as previously described (Huang et al. 2016a). The powders were collected and sealed in sterilized polystyrene bottles (Gosselin, France); stored at a controlled temperature of 4, 20, or 37 °C; and kept away from light. The samples were stored for analyses for 112 days (approximately 4 months). One gram of powder was solubilized in 9 g of sterile water and bacterial viability was tested by numeration on YEL agar plates incubated at 30 °C.

Freeze-drying

P. freudenreichii strains were grown in the YEL, YEL+NaCl, YEL+lactose, and YEL+lactose+NaCl media. At the beginning of the stationary phase, cultures were harvested (8000g, 10 min, 30 °C). Pellets were then homogenized in a maltodextrin solution (DE = 6–8) (Roquette, France) with a final concentration of 10% (w/w). The bacterial solutions were then freeze-dried (2253-04, Serail, France). The bacterial viabilities were estimated by numeration on YEL agar plates incubated at 30 °C before and after freeze-drying.

Statistical analysis

Each analysis was done in 3 biological replicates. Hence, the results presented in this study are averages of three independent replicates or experiments. All the results are presented as a mean value with standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc analyses for multiple comparison. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism Software (Prism 7 for Windows).

Results

P. freudenreichii growth parameters depend on carbon sources and on salt concentration

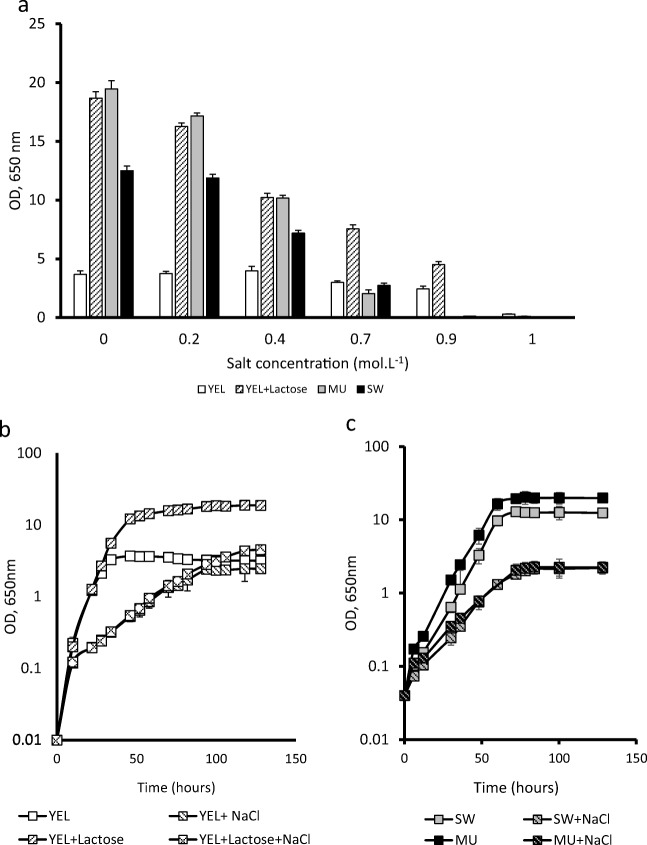

The addition of lactose (34 g L−1) to the rich YEL medium increased the final population of propionibacteria in agreement with P. freudenreichii ability to use both lactate and lactose, as shown in Fig. 1 a. MU (milk ultrafiltrate) and SW (sweet whey) both allowed growth of P. freudenreichii up to populations above those allowed by YEL. These media contain lactose. The presence of NaCl inhibited P. freudenreichii growth in all media. However, only the rich YEL medium sustained growth of P. freudenreichii up to 0.9 M NaCl, in agreement with the presence of osmoprotectants. The dairy culture media, MU (milk ultrafiltrate) and SW (sweet whey), failed to allow growth of P. freudenreichii in the presence of such high salt concentrations (Fig. 1a). The addition of salt (NaCl 0.9 M), to the rich YEL medium containing lactose, and NaCl 0.7 M to MU and to SW, decreased both parameters, i.e., growth rates and final populations, compared to a non-salty medium (Fig. 1b and c). In contrast, the addition of salt (NaCl 0.9 M) to YEL without lactose decreased the growth rate but the final population was maintained, compared to the YEL control. The addition of lactose to the YEL and to the YEL medium containing NaCl had no impact on the P. freudenreichii growth rate but increased final populations, in agreement with its role as a fermentation substrate. Accordingly, the pH decreased down to values close to 5 in all media containing lactose, while it remained close to 6.5 in YEL without lactose.

Fig. 1.

P freudenreichii growth in media supplemented or not with NaCl. a Final optical densities were measured after 130 h of growth in YEL-type media (YEL, YEL+NaCl YEL+lactose, and YEL+lactose+NaCl) and in dairy-type media (SW, SW+NaCl, MU and MU+NaCl) in different salt concentrations. b, cP. freudenreichii CIRM-BIA 129 growth was then monitored in these media in the presence of the highest NaCl concentration that would allow growth. YEL: yeast extract lactate. MU: milk ultrafiltrate. SW: sweet whey

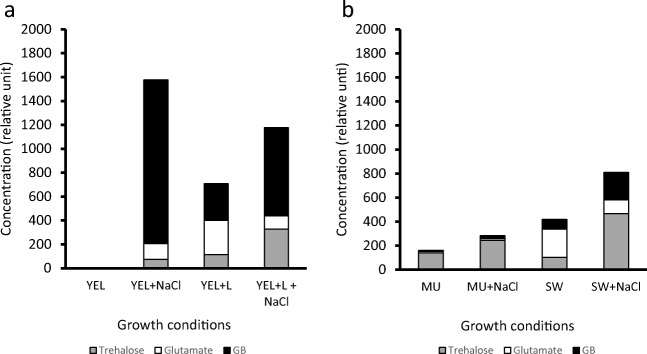

Osmoprotectants accumulation in P. freudenreichii is medium-dependent

Salt addition improved the total amount of osmoprotectants accumulated by P. freudenreichii, regardless of the culture medium (Fig. 2a and b). The presence of lactose had a similar impact: in YEL containing lactose and in YEL containing lactose and NaCl, the total amount of osmoprotectants accumulated was higher than that in YEL and in YEL containing NaCl, respectively. This is in agreement with the additional 0.1 osmol of osmotic pressure due to 34 g L−1 of lactose and with the acidification of the growth medium. As a negative control, the YEL medium, with an osmolality of 0.308 osmol, causes no osmotic stress and, consequently, no osmoprotectant accumulation inside bacteria. In the presence of salt (YEL containing NaCl), P. freudenreichii mainly accumulated glycine betaine (1370 relative units (RU)) and low amounts of glutamate (132 RU) and trehalose (74 RU). In the presence of lactose (YEL containing lactose and NaCl), P. freudenreichii accumulated higher proportions of trehalose (328 RU) and lower proportions of glycine betaine (739 RU). In MU and in SW, which are both rich in lactose, the addition of salt led P. freudenreichii to mainly accumulate trehalose (244 RU and 467 RU, respectively), as well as small amounts of glycine betaine and of glutamate (14 RU and 26 RU, respectively, for MU+NaCl and 228 RU, and 114 RU, respectively, for SW+NaCl).

Fig. 2.

P freudenreichii osmoprotectants accumulation is medium-dependent. P. freudenreichii CIRM-BIA 129 was cultivated in YEL-type media (a) and dairy-type media (b) with or without NaCl. Cytoplasmic extracts were made, as described in the “Materials and methods” section. Intracellular osmoprotectants were then identified and quantified by NMR analysis. Osmoprotectants accumulations are expressed as relative units. YEL: yeast extract lactate. L: lactose. MU: milk ultrafiltrate. SW: sweet whey

In conclusion, the three growth media that contain lactose (YEL containing lactose, MU, and SW) triggered osmoprotectant accumulation even in the absence of salt. Salt triggered GB accumulation in YEL, and this accumulation was reverted by lactose addition, which leads to trehalose accumulation. In YEL containing NaCl, GB is the main compound accumulated, whereas in MU containing NaCl and SW containing NaCl, trehalose is the main compound accumulated.

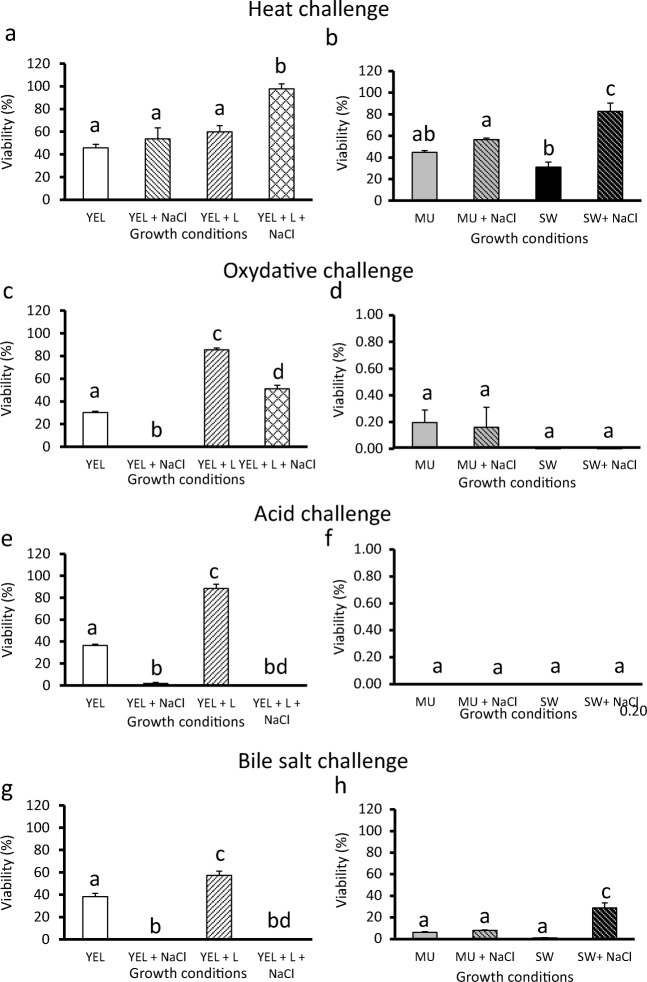

Multiple stress tolerance of P. freudenreichii is medium-dependent

P. freudenreichii stress tolerance was monitored by subjecting bacteria to heat, oxidative, acid, and bile salt challenges. P. freudenreichii viability was determined by numeration before and after stress challenges. We selected a series of challenges relevant for both technological and digestive constraints. The presence of NaCl in YEL medium had no impact on P. freudenreichii heat resistance at 60 °C (Fig. 3(A)), but had a significant positive effect in the YEL containing lactose and NaCl, SW containing NaCl, and MU containing NaCl media (97.9%, 82.7%, and 56.6%, respectively), compared to the non-salty media (60.0%, 31.0%, and 44.8%, respectively) (Fig. 3(A, B)). However, the presence of salt in the four media (YEL containing NaCl, YEL containing lactose and NaCl, SW containing NaCl, and MU containing NaCl) had a significant negative effect or no impact on P. freudenreichii survival to oxidative, acid, and bile salt (Fig. 3(C–H)). These results reveal a cross-protection between osmoadaptation and heat stress, but not for the other stresses. The presence of lactose (YEL containing Lactose and YEL containing lactose and NaCl) had a significant positive impact for the four different lethal challenges.

Fig. 3.

Cross-protections conferred to P. freudenreichii are medium-dependent. P. freudenreichii CIRM-BIA 129 was cultivated until the beginning of the stationary phase in YEL-type media (A, C, E, G) and dairy-type media (B, D, F, H), with and without NaCl. Cultures were then subjected to heat (A and B, 60 °C for 10 min), oxidative (C and D, 1.25 mM H2O2 for 1 h), acid challenges (E and F, pH = 2 for 1 h), or bile salts (G and H, 1 g L−1 for 1 h) challenges, as described in the “Materials and methods” section. P. freudenreichii viability was determined by CFU counting in treated and control samples. Results are expressed as a percentage of survival. Error bars represent the standard deviation for triplicate experiments. Significant differences are reported with different letters above the columns (p > 0.05). YEL: yeast extract lactate. L: lactose. MU: milk ultrafiltrate. SW: sweet whey

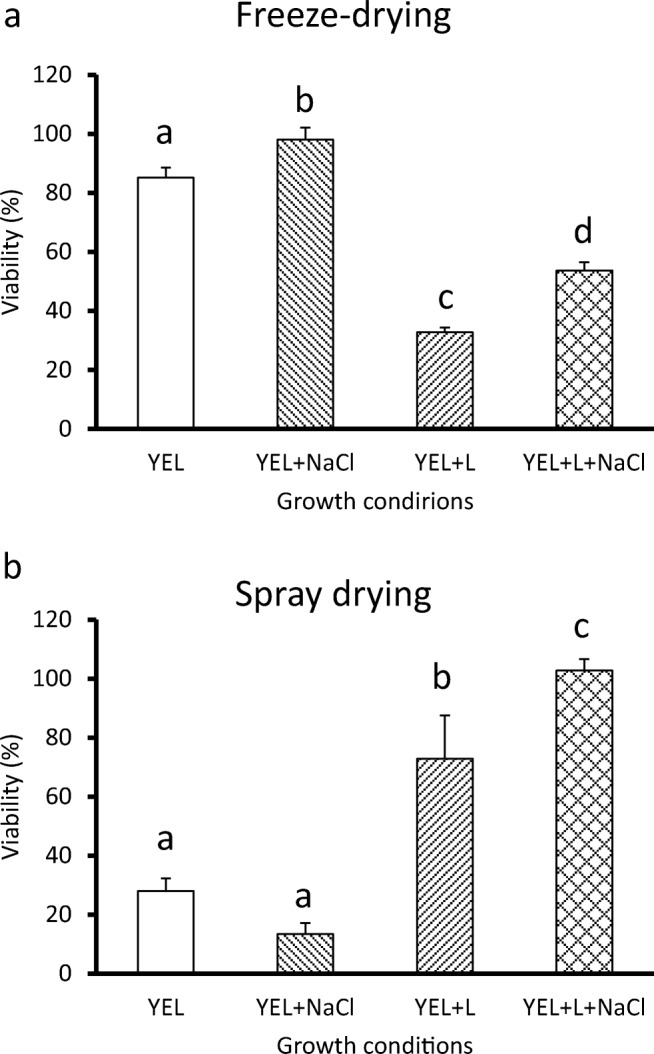

P. freudenreichii viability after drying

Different P. freudenreichii cultures, with or without the addition of salt, were subjected to freeze-drying or spray-drying in order to evaluate tolerance towards industrial drying processes. The presence of salt in YEL containing NaCl, and in YEL containing lactose and NaCl, had a significant positive impact on P. freudenreichii viability during freeze-drying (98.0% and 53.7%, respectively) compared to YEL and YEL containing lactose (85.2% and 32.8%, respectively) (Fig. 4(A)). The addition of lactose had a significant negative impact on P. freudenreichii viability during freeze-drying.

Fig. 4.

P. freudenreichii adaptation modulates P. freudenreichii viability during freeze-drying and spray-drying. P. freudenreichii CIRM-BIA 129 was cultivated until the beginning of the stationary phase in YEL medium, in the presence or absence of NaCl and of lactose. P. freudenreichii were harvested, and then suspended in a maltodextrin solution (20%). The suspension was freeze-dried (A) and spray-dried (B), as described in the “Materials and methods” section. Results are expressed as a percentage of survival. Error bars represent the standard deviation for triplicate experiments. Significant differences are reported with different letters above the columns (p > 0.05). YEL: yeast extract lactate. L: lactose

Concerning the spray-drying process, a similar significant positive effect of NaCl was observed for bacteria grown in YEL containing lactose and NaCl compared to YEL containing lactose (102% and 73%, respectively, Fig. 4(B)). In contrast, bacteria grown in YEL containing NaCl exhibited a significantly lower viability, compared to bacteria grown in YEL (13% and 28%, respectively, Fig. 4(B)).

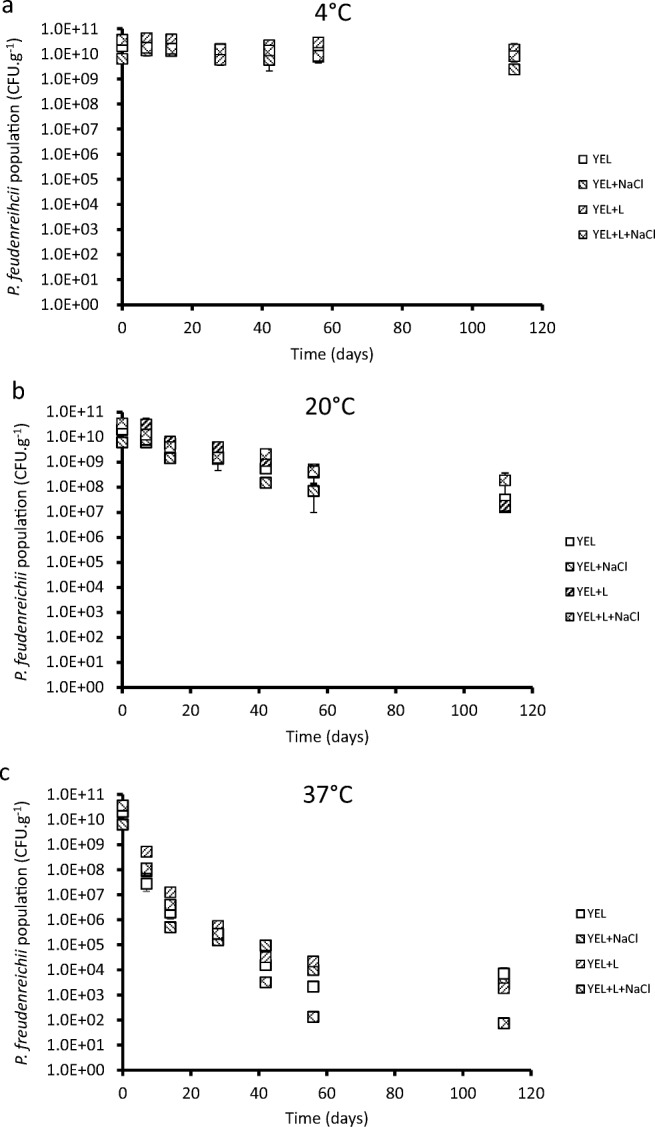

P. freudenreichii viability after spray-drying and powder storage

The viability P. freudenreichii within spray-dried powders depends on growth conditions and on storage temperature. During storage at 4 °C, bacterial viability was stable over time (Fig. 5a). At 20 °C, the viability decreased. However, P. freudenreichii grown in YEL containing lactose and NaCl seemed to maintain a better viability over time, in comparison with the other growth conditions (Fig. 5b). During storage at 37 °C, P. freudenreichii viability decreased significantly (p < 0.05 at time 112 days) faster than during storage at 20 °C (Fig. 5b, c). At 37 °C, powders resulting from cultures in YEL medium containing lactose and NaCl exhibited a lower stability over time than the other cultures.

Fig. 5.

Storage temperature and P. freudenreichii adaptation modulates its viability during powder storage. The different powders were stored at 4 °C (a), 20 °C (b), and 37 °C (c) for 115 days. P. freudenreichii populations in spray-dried powders were quantified by CFU counting (as described in the “Material and methods” section) during storage. YEL: yeast extract lactate. L: lactose

Discussion

The growth medium composition fine-tunes P. freudenreichii adaptation and osmoprotectants accumulation

This study revealed that P. freudenreichii is able to adapt to various concentrations of salt, and that different culture media support this adaptation. P. freudenreichii grew in the presence of 0.4 M NaCl, regardless of the medium. Growth was further observed up to 0.9 M NaCl in YEL medium and final populations were further enhanced by the addition of lactose. This indicates that, compared to milk ultrafiltrate (MU), YEL provides more potent osmoprotectants. It contains yeast extract and tryptone, which are sources of non-protein nitrogen (NPN) such as amino acids, peptides, glycine betaine, and soluble vitamins (Frings et al. 1993; Maria-Rosario et al. 1995; Robert et al. 2000). This large amount of NPN that provided potent osmoprotectants led to the efficient osmoadaptation of P. freudenreichii and a better tolerance of salt than MU and SW media, which contain less NPN. For all culture media, the salt concentration chosen was the highest that would allow P. freudenreichii to grow. However, in all salty growth media, P. freudenreichii exhibited slower growth compared to non-salty medium.

Previous studies clearly evidence accumulation of osmoprotectants as a result of osmotic stress, triggering osmoadaptation (Kets et al. 1996; Cardoso et al. 2007; Dalmasso et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2016c). The accumulated osmoprotectants were analyzed by NMR as described by Behrends et al. (2011), Pleitner et al. (2012), Vaidya et al. (2018), and Weinisch et al. (2019). During osmoadaptation, P. freudenreichii is able to accumulate glycine betaine, trehalose, and glutamate, as already reported (Huang et al. 2016c; Gaucher et al. 2019). Glycine betaine is an osmoprotectant which can be accumulated by numerous bacteria such as P. freudenreichii, Lactococcus lactis, and L. plantarum (Glaasker et al. 1996; Romeo et al. 2003; Huang et al. 2016c). Accumulation of trehalose is a key constituent of stress response in P. freudenreichii (Cardoso et al. 2007; Dalmasso et al. 2012). More generally, this disaccharide is accumulated by different species in many stressful conditions such as acid, cold, osmotic, and oxidative stress (Cardoso et al. 2004, 2007; Thierry et al. 2011; Huang et al. 2016c). Glutamate accumulation in hyperosmotic conditions is well known and has been reported for L. plantarum (Kets et al. 1996; Glaasker et al. 1996). It constitutes the primary response to osmotic upshift and its transient accumulation is followed by its replacement with osmoprotectants such as trehalose in many types of cells (Csonka 1989).

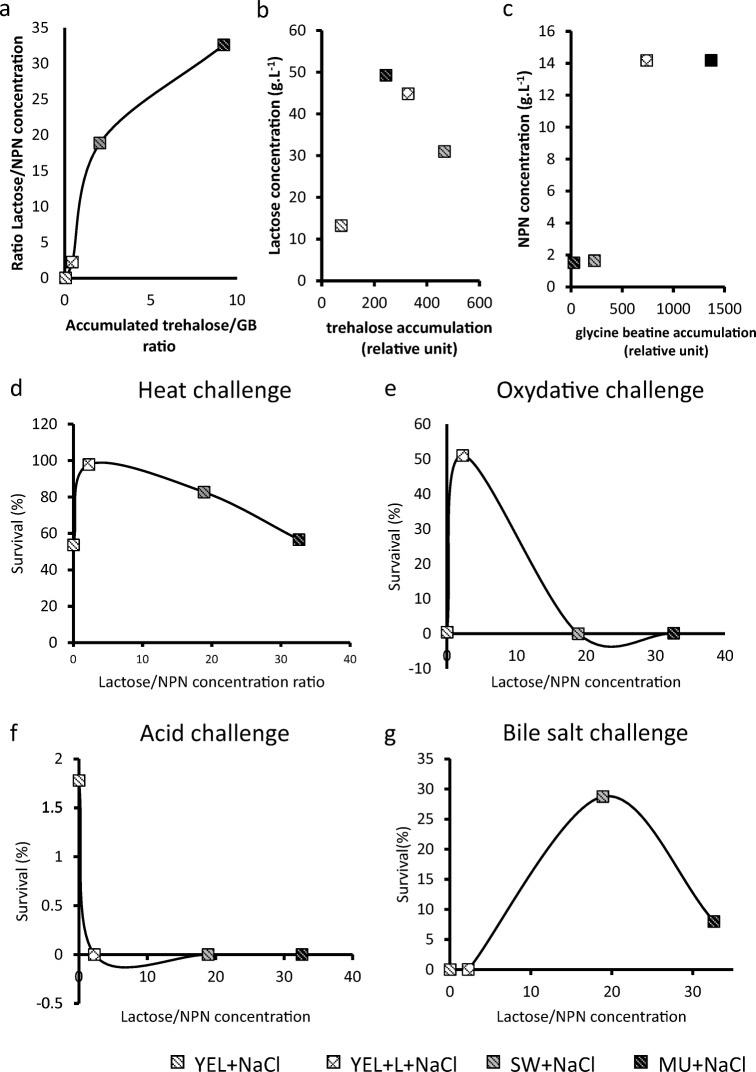

The YEL containing NaCl, which contains only lactate as a carbon source as well as large amounts of NPN, allowed the accumulation of high intracellular concentrations of GB. Other bacteria, including Brevibacterium, Corynebacterium, and Enterococcus faecalis, accumulate glycine betaine under hyperosmotic constraint in the presence of yeast extract (59, 66). The addition of lactose in YEL containing NaCl improved trehalose accumulation at the expense of GB accumulation. The same trend was observed in the dairy media. In MU, GB concentration is too low, whereas lactose is abundant (Table 1), leading to the accumulation of trehalose in hyperosmotic conditions. SW has a lower lactose/NPN ratio than MU (18.9 and 32.6, respectively), and P. freudenreichii accordingly accumulated osmoprotectants with a lower trehalose/glycine betaine ratio in SW containing NaCl than in MU containing NaCl (18.9 and 32.6, respectively). These data suggested a correlation between osmoprotectant accumulation and growth medium composition. We thus plotted the trehalose/GB ratio as a function of the lactose/NPN ratio (Fig. 6(A)), using values calculated from Table 1 and Fig. 2. This confirms such a correlation. In contrast, Fig. 6 (B) and (C) do not suggest any correlation between the lactose and intracellular trehalose provided per se or the NPN and intercellular GB provided per se. There is a correlation between the intracellular trehalose/GB ratio accumulated by P. freudenreichii and the lactose/NPN ratio of the growth medium composition (Fig. 6(A)). The higher the lactose/NPN concentration ratio is, the higher the trehalose/NPN ratio will be. Modulating the nitrogen and carbon composition of the growth medium thus made it possible to regulate the amount and composition of intercellular osmoprotectants in P. freudenreichii.

Fig. 6.

Fine-tuning the lactose/NPN ratio modulates physiological parameters including OP and stress tolerance. Data from the “Results” section were used to establish a correlation between the lactose/NPN ratio and the physiological parameters. The lactose/NPN ratio of growth media was plotted as a function of trehalose/NPN (A), the trehalose accumulation as a function of lactose concentration in growth media (B), and the GB accumulation as a function of NPN concentration in growth media. The lactose/NPN ratio was also plotted as a function of heat tolerance (D), of oxidative tolerance (E), of acid tolerance (F), and of bile salt tolerance (G). This suggests that the lactose/NPN ratio is correlated with the trehalose/GB ratio and that an optimal lactose/NPN ratio exists for each stress challenge

Growth medium composition determines viability during lethal challenges

Accumulation of osmoprotectants may confer cross-protection towards various stress (Sheehan et al. 2006; Huang et al. 2016c, 2018). P. freudenreichii-osmoadapted cultures exhibited enhanced viability upon heat challenges, as already described (Huang et al. 2016c), regardless of the growth medium. This confirms that a cross-protection exists towards heat stress. Escherichia coli and Pantoea agglomerans also exhibited higher thermotolerance following GB accumulation favored by osmoadaptation (Teixido et al. 2005; Pleitner et al. 2012). In contrast, in our study, osmoadaptation decreased P. freudenreichii tolerance towards oxidative, acid, and bile salt challenges. Pichereau et al. (1999) reported a decreased bile salt tolerance in Enterococcus faecalis as a result of GB accumulation. In our study, the addition of lactose to YEL-type medium triggered high trehalose accumulation and increased P. freudenreichii tolerance towards heat, oxidative, acid, and bile salt challenges. Trehalose accumulation accordingly leads to enhanced tolerance of L.s lactis towards acid and bile salt challenges (Termont et al. 2006; Carvalho et al. 2011).

Huang et al. reported that P. freudenreichii osmoadaptation in hyperconcentrated SW, which contains high amounts of lactose, triggered increased tolerance towards heat, acid, and bile salt challenges. Hyperconcentrated SW imposed osmoadaptation to P. freudenreichii, without variation of the lactose/NPN ratio (Huang et al. 2018). This enhanced tolerance towards different challenges could thus be explained by trehalose accumulation during osmoadaptation and by the matrix protection of the hyperconcentrated SW.

We then plotted the survival rates upon the different stress challenges (from Fig. 3) as a function of the lactose/NPN ratio (from Table 1). For each challenge, the resulting curve (Fig. 6(D–G)) suggests that an optimal lactose/NPN ratio corresponds to an optimal survival rate. In these experiments, a ratio close to 2.3 correlated with the highest tolerance to heat and oxidative challenges (Fig. 6(B, C)), while a ratio close to 20 correlated with the highest tolerance to bile salt challenges (Fig. 6(D)). Acid tolerance of P. freudenreichii occurred when the accumulation of GB was the highest (Fig. 6(E)).

Regulating P. freudenreichii osmoadaptation makes it possible to increase its survival during drying and storage

Different P. freudenreichii YEL cultures, with or without NaCl and with or without lactose, exhibited various survival rates upon drying. Concerning freeze-drying, osmoadaptation in YEL containing NaCl led to the best viability after freeze-drying. Such a protection seems to be correlated with the high accumulation of glycine betaine. Accumulation of GB can either increase Lactobacillus salivarius tolerance or decrease Lactobacillus coryniformis tolerance towards freeze-drying (Sheehan et al. 2006; Bergenholtz et al. 2012). Concerning spray-drying, the best tolerance was observed for P. freudenreichii grown in YEL containing lactose and NaCl. Its osmoadaptation in medium containing lactose, leading to more trehalose accumulation, allowed an enhanced adaptation towards spray-drying. This is in accordance with the enhanced tolerance towards heat and oxidative challenges (stresses encountered during spray-drying), which was observed in these cultures. Different osmoadaptations thus have different impacts on P. freudenreichii tolerance towards both drying processes. In contrast, GB accumulation in L. salivarius improved its resistance to freeze-drying and to spray-drying (Sheehan et al. 2006).

P. freudenreichii grown in YEL containing lactose and NaCl experienced a high viability loss during storage at high temperatures (Fig. 5c). P. freudenreichii adaptation can be used to obtain better viability during a particular process, but one culture condition cannot provide protection from all the technological stresses. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing that, in addition to triggering osmoadaptation, it is possible, in propionibacteria, to fine tune the trehalose/GB ratio and thus to modulate stress tolerance. Furthermore, this is the first report showing that fine-tuning trehalose accumulation and trehalose/GB ratio drastically increases survival upon spray-drying, a process known to induce massive cell death.

Propionibacteria adaptation can be used to optimize viability during specific industrial processes. Growth medium composition, like carbon sources, nitrogen sources, and the ratio thereof, can be controlled to optimize bacterial adaptation. However, an adaptation can improve bacterial viability during a technological stress but not during all the production and digestion processes.

Acknowledgments

F. Gaucher is the recipient of a joint doctoral fellowship from Bioprox and from the ANRT (Agence Nationale Recherche Technologie). Authors thank Emy Molet and Ermin Thal for the technical assistance.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Behrends V, Bundy JG, Williams HD. Differences in strategies to combat osmotic stress in Burkholderia cenocepacia elucidated by NMR-based metabolic profiling. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2011;52:619–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergenholtz ÅS, Wessman P, Wuttke A, Håkansson S. A case study on stress preconditioning of a Lactobacillus strain prior to freeze-drying. Cryobiology. 2012;64:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouglé D, Roland N, Lebeurrier F. Effect of propionibacteria supplementation on fecal bifidobacteria and segmental colonic transit time in healthy human subjects. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:144–148. doi: 10.1080/00365529950172998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso FS, Gaspar P, Hugenholtz J, Ramos A, Santos H. Enhancement of trehalose production in dairy propionibacteria through manipulation of environmental conditions. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;91:195–204. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00387-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso FS, Castro RF, Borges N, Santos H. Biochemical and genetic characterization of the pathways for trehalose metabolism in Propionibacterium freudenreichii, and their role in stress response. Microbiology. 2007;153:270–280. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AL, Cardoso FS, Bohn A, Neves AR, Santos H. Engineering trehalose synthesis in Lactococcus lactis for improved stress tolerance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:4189–4199. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02922-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro BF, Oliveira ER, da Silva SH, Savassi BM, Acurcio LB, Lemos L, Alves J d L, Carvalho Assis H, Vieira AT, AMC F, Ferreira E, Le Loir Y, Jan G, Goulart LR, Azevedo V, Carvalho RD d O, do Carmo FLR (2018) Whey protein isolate-supplemented beverage, fermented by Lactobacillus casei BL23 and Propionibacterium freudenreichii 138, in the prevention of mucositis in mice. Front Microbiol 9. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cousin FJ, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Théret N, Brenner C, Jouan E, Le Moigne-Muller G, Dimanche-Boitrel M-T, Jan G (2016) The probiotic Propionibacterium freudenreichii as a new adjuvant for TRAIL-based therapy in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 7. 10.18632/oncotarget.6881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Csonka LN. Physiological and genetic responses of bacteria to osmotic stress. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:121–147. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.53.1.121-147.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmasso M, Aubert J, Even S, Falentin H, Maillard M-B, Parayre S, Loux V, Tanskanen J, Thierry A. Accumulation of intracellular glycogen and trehalose by Propionibacterium freudenreichii under conditions mimicking cheese ripening in the cold. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:6357–6364. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00561-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA experts Scientific opinion of the panel on biological hazards on a request from EFSA on the maintenance of the QPS list of microorganisms intentionally added to food or feed. EFSA J. 2008;923:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ogg C L. Determination of Nitrogen by the Micro-Kjeldahl Method. Journal of AOAC INTERNATIONAL. 1960;43(3):689–693. doi: 10.1093/jaoac/43.3.689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foligne B, Deutsch S-M, Breton J, Cousin FJ, Dewulf J, Samson M, Pot B, Jan G. Promising immunomodulatory effects of selected strains of dairy propionibacteria as evidenced in vitro and in vivo. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:8259–8264. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01976-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foligné B, Breton J, Mater D, Jan G. Tracking the microbiome functionality: focus on Propionibacterium species. Gut. 2013;62:1227–1228. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frings E, Kunte HJ, Galinski EA. Compatible solutes in representatives of the genera Brevibacterium and Corynebacterium : occurrence of tetrahydropyrimidines and glutamine. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;109:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06138.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaucher Floriane, Bonnassie Sylvie, Rabah Houem, Leverrier Pauline, Pottier Sandrine, Jardin Julien, Briard-Bion Valérie, Marchand Pierre, Jeantet Romain, Blanc Philippe, Jan Gwénaël. Benefits and drawbacks of osmotic adjustment in Propionibacterium freudenreichii. Journal of Proteomics. 2019;204:103400. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2019.103400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaasker E, Konings WN, Poolman B. Osmotic regulation of intracellular solute pools in Lactobacillus plantarum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:575–582. doi: 10.1128/JB.178.3.575-582.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gripon JC, Desmazeaud MJ, Le Bars D, Bergere JL. Etude du rôle des micro-organismes et des enzymes au cours de la maturation des fromages. Lait. 1975;55:502–5016. doi: 10.1051/lait:197554828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hojo K, Yoda N, Tsuchita H, Ohtsu T, Seki K, Taketomo N, Murayama T, Iino H. Effect of ingested culture of Propionibacterium freudenreichii ET-3 on fecal microflora and stool frequency in healthy females. Biosci Microflora. 2002;21:115–120. doi: 10.12938/bifidus1996.21.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Cauty C, Dolivet A, Le Loir Y, Chen XD, Schuck P, Jan G, Jeantet R. Double use of highly concentrated sweet whey to improve the biomass production and viability of spray-dried probiotic bacteria. J Funct Foods. 2016;23:453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2016.02.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Rabah H, Jardin J, Briard-Bion V, Parayre S, Maillard M-B, Le Loir Y, Chen XD, Schuck P, Jeantet R, Jan G. Hyperconcentrated sweet whey, a new culture medium that enhances Propionibacterium freudenreichii stress tolerance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:4641–4651. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00748-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Gaucher F, Cauty C, Jardin J, Le Loir Y, Jeantet R, Chen XD, Jan G (2018) Growth in hyper-concentrated sweet whey triggers multi stress tolerance and spray drying survival in Lactobacillus casei BL23: from the molecular basis to new perspectives for sustainable probiotic production. Front Microbiol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hugenholtz J, Hunik J, Santos H, Smid E. Nutraceutical production by propionibacteria. Lait. 2002;82:103–112. doi: 10.1051/lait:2001009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Isawa K, Hojo K, Yoda N, Kamiyama T, Makino S, Saito M, Sugano H, Mizoguchi C, Kurama S, Shibasaki M, Endo N, Sato Y. Isolation and identification of a new bifidogenic growth stimulator produced by Propionibacterium freudenreichii ET-3. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2002;66:679–681. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan G, Rouault A, Maubois J-L. Acid stress susceptibility and acid adaptation of Propionibacterium freudenreichii subsp. shermanii. Lait. 2000;80:325–336. doi: 10.1051/lait:2000128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jan G, Belzacq A-S, Haouzi D, Rouault A, Métivier D, Kroemer G, Brenner C. Propionibacteria induce apoptosis of colorectal carcinoma cells via short-chain fatty acids acting on mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:179–188. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kets E, Teunissen P, de Bont J. Effect of compatible solutes on survival of lactic acid bacteria subjected to drying. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:259–261. doi: 10.1128/AEM.62.1.259-261.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan A, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Lemaire C, Brenner C, Jan G. Acidic extracellular pH shifts colorectal cancer cell death from apoptosis to necrosis upon exposure to propionate and acetate, major end-products of the human probiotic propionibacteria. Apoptosis. 2007;12:573–591. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-0010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan A, Bruneau A, Bensaada M, Philippe C, Bellaud P, Rabot S, Jan G. Increased induction of apoptosis by Propionibacterium freudenreichii TL133 in colonic mucosal crypts of human microbiota-associated rats treated with 1,2-dimethylhydrazine. Br J Nutr. 2008;100:1251–1259. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508978284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverrier P, Dimova D, Pichereau V, Auffray Y, Boyaval P, Jan G. Susceptibility and adaptive response to bile salts in Propionibacterium freudenreichii: physiological and proteomic analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:3809–3818. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.7.3809-3818.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverrier P, Vissers JPC, Rouault A, Boyaval P, Jan G. Mass spectrometry proteomic analysis of stress adaptation reveals both common and distinct response pathways in Propionibacterium freudenreichii. Arch Microbiol. 2004;181:215–230. doi: 10.1007/s00203-003-0646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik AC, Reinbold GW, Vedamuthu ER. An evaluation of the taxonomy of Propionibacterium. Can J Microbiol. 1968;14:1185–1191. doi: 10.1139/m68-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maria-Rosario A, Davidson I, Debra M, Verheul A, Abee T, Booth IR. The role of peptide metabolism in the growth of Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 23074 at high osmolarity. Microbiology. 1995;141:41–49. doi: 10.1099/00221287-141-1-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuyama K, Masuda J, Yamasaki H, Kuwaki K, Kitazaki S, Koga H, Uchida M, Sata M. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with milk whey culture with Propionibacterium freudenreichii. J Intest Microbiol. 2007;21:143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Hokari R, Kato S, Mataki N, Okudaira K, Takebayashi K. 1.4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid (DHNA) shows anti-inflammatory effect on NSAID-induced colitis in IL-10-knockout mice through suppression of inflammatory cell infiltration and increased number of genus Bifidobacterium. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:A313. [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Tsuzuki Y, Miyazaki J, Hokari R, Komoto S. Propionibacterium freudenreichii component 1.4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid (DHNA) attenuates dextran sodium sulphate induced colitis by modulation of bacterial flora and lymphocyte homing. Gut. 2006;55:681–688. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.070490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichereau V, Bourot S, Flahaut S, Blanco C, Auffray Y, Bernard T. The osmoprotectant glycine betaine inhibits salt-induced cross-tolerance towards lethal treatment in Enterococcus faecalis. Microbiology. 1999;145:427–435. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-2-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plé C, Richoux R, Jardin J, Nurdin M, Briard-Bion V, Parayre S, Ferreira S, Pot B, Bouguen G, Deutsch S-M, Falentin H, Foligné B, Jan G. Single-strain starter experimental cheese reveals anti-inflammatory effect of Propionibacterium freudenreichii CIRM BIA 129 in TNBS-colitis model. J Funct Foods. 2015;18:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plé C, Breton J, Richoux R, Nurdin M, Deutsch S-M, Falentin H, Hervé C, Chuat V, Lemée R, Maguin E, Jan G, Van de Guchte M, Foligné B. Combining selected immunomodulatory Propionibacterium freudenreichii and Lactobacillus delbrueckii strains: reverse engineering development of an anti-inflammatory cheese. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016;60:935–948. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleitner A, Zhai Y, Winter R, Ruan L, McMullen LM, Gänzle MG. Compatible solutes contribute to heat resistance and ribosome stability in Escherichia coli AW1.7. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824:1351–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabah H, Rosa do Carmo F, Jan G. Dairy propionibacteria: versatile probiotics. Microorganisms. 2017;5:24. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms5020024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabah H, Ménard O, Gaucher F, do Carmo FLR, Dupont D, Jan G. Cheese matrix protects the immunomodulatory surface protein SlpB of Propionibacterium freudenreichii during in vitro digestion. Food Res Int. 2018;106:712–721. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert H, Le Marrec C, Blanco C, Jebbar M. Glycine betaine, carnitine, and choline enhance salinity tolerance and prevent the accumulation of sodium to a level inhibiting growth of Tetragenococcus halophila. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:509–517. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.2.509-517.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo Y, Obis D, Bouvier J, Guillot A, Fourçans A, Bouvier I, Gutierrez C, Mistou M-Y. Osmoregulation in Lactococcus lactis: BusR, a transcriptional repressor of the glycine betaine uptake system BusA. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:1135–1147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarela M, Virkajarvi I, Alakomi H-L, Mattila-Sandholm T, Vaari A, Suomalainen T, Matto J. Influence of fermentation time, cryoprotectant and neutralization of cell concentrate on freeze-drying survival, storage stability, and acid and bile exposure of Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis cells produced without milk-based ingredients. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;99:1330–1339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki K, Nakao H, Umino H, Isshiki H, Yoda N, Tachihara R. Effects of fermented milk whey containing novel bifidogenic growth stimulator produced by Propionibacterium on fecal bacteria, putrefactive metabolite, defecation frequency and fecal properties in senile volunteers needed serious nursing-care taking enteral nutrition by tube feedin. J Intest Microbiol. 2004;18:107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Serata M, Kiwaki M, Iino T. Functional analysis of a novel hydrogen peroxide resistance gene in Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota. Microbiology. 2016;162:1885–1894. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan VM, Sleator RD, Fitzgerald GF, Hill C. Heterologous expression of BetL, a betaine uptake system, enhances the stress tolerance of Lactobacillus salivarius UCC118. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2170–2177. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.3.2170-2177.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixido N, Canamas TP, Usall J, Torres R, Magan N, Vinas I. Accumulation of the compatible solutes, glycine-betaine and ectoine, in osmotic stress adaptation and heat shock cross-protection in the biocontrol agent Pantoea agglomerans CPA-2. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2005;41:248–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Termont S, Vandenbroucke K, Iserentant D, Neirynck S, Steidler L, Remaut E, Rottiers P. Intracellular accumulation of trehalose protects Lactococcus lactis from freeze-drying damage and bile toxicity and increases gastric acid resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7694–7700. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01388-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierry A, Deutsch S-M, Falentin H, Dalmasso M, Cousin FJ, Jan G. New insights into physiology and metabolism of Propionibacterium freudenreichii. Int J Food Microbiol. 2011;149:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya S, Dev K, Sourirajan A. Distinct osmoadaptation strategies in the strict halophilic and halotolerant bacteria isolated from lunsu salt water body of north west himalayas. Curr Microbiol. 2018;75:888–895. doi: 10.1007/s00284-018-1462-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinisch L, Kirchner I, Grimm M, Kühner S, Pierik AJ, Rosselló-Móra R, Filker S. Glycine betaine and ectoine are the major compatible solutes used by four different halophilic heterotrophic ciliates. Microb Ecol. 2019;77:317–331. doi: 10.1007/s00248-018-1230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]