Abstract

DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system is important for maintaining DNA replication fidelity and genome stability by repairing erroneous deletions, insertions and mis-incorporation of bases. With the aim of deciphering the role of the MMR system in genome stability and recombination in rice, we investigated the function of OsMSH6 gene, an import component of the MMR system. To achieve this goal, homeologous recombination and endogenous microsatellite stability were evaluated by using rice mutants carrying a Tos17 insertion into the OsMSH6 gene. Totally 60 microsatellites were analyzed and 15 distributed on chromosome 3, 6, 8, and 10 showed instability in three OsMSH6 mutants, D6011, NF7784 and NF9010, compared with the wild type MSH6WT (the control). The disruption of OsMSH6 gene is associated with modest increases in homeologous recombination, ranging from 2.0% to 32.5% on chromosome 1, 3, 9, and 10 in the BCF2 populations of the mutant ND6011 and NF9010. Our results suggest that the OsMSH6 plays an important role in ensuring genome stability and genetic recombination, providing the first evidence for the MSH6 gene in maintaining microsatellite stability and restricting homeologous recombination in plants.

Keywords: DNA mismatch repair, homeologous recombination, microsatellite stability, OsMSH6, rice (Oryza sativa)

Introduction

Living cells respond to DNA damaging agents by modulating gene expression and arresting the cell cycle to ensure efficient DNA repair during their entire life. For maintaining the genetic stability and integrity, several DNA damage repair systems have been formed in the process of evolution (Schröpfer et al., 2014; Spampinato, 2017), one of which is mismatch repair (MMR). The MMR system is a major DNA repair pathway with ability to recognize and repair erroneous insertions, deletions and mis-incorporation of bases during DNA replication, genetic recombination and repair of some forms of DNA damage (Iyer et al., 2006; Jriecny, 2006; Spampanito et al., 2009). Plant MMR system consists of MutL and MutS mismatch repair homolog proteins, without MutH which is exclusively found in prokaryotes (Modrich, 1991; Fukui, 2010; Singh et al., 2010). As the most important monomers in MMR system, MSH2 and MLH1 form heterodimers with other MMR proteins, such as MutSα (MSH2-MSH6), MutSβ (MSH2-MSH3), MutSγ (MSH2-MSH7), MutLα (MLH1-PMS1), and MutLγ (MLH1-MLH3) (Ade et al., 1999; Culligan and Hays, 2000; Higgins et al., 2004; Li, 2008). MutSα is predominantly involved in the correction of short insertion/deletion loops (IDLs) and base-base mismatches, while MutSβ is preferentially required to remove the large IDLs (2-12 nucleotides), and plant specific MutSγ mainly recognizes single base mismatches (Culligan and Hays, 2000; Gomez and Spampinato, 2013).

Microsatellites, also called simple sequence repeats (SSRs), are simple tandem repeats of 1–6 bp DNA motifs and have been considered as a general source for polymorphic DNA markers widely used for multiple purposes in plants (Tautz, 1989; Varshney et al., 2005; Kalia et al., 2011). They are often subject to frequent unequal crossing over by misaligned pairing of repeats (Lovett, 2004) and inherently unstable as a consequence of a high level of DNA polymerase slippage on repetitive DNA during the replication process (Sia et al., 1997, 2001; Tran et al., 1997; Schlötterer, 2000). Such regions in genome are intrinsically unstable, causing size variation in the repeat sequences, contractions or expansions of the number of repeat units (Nag et al., 2004). As a type of molecular marker with several advantages, such as strong discriminatory power, co-dominant inheritance, and greater reproducibility (Varshney et al., 2005), SSR is suitable for monitoring genome instability. Microsatellite instability (MSI) is also considered as a consequence of MMR deficiency and has emerged as an important predictor of sensitivity for multiple human tumor types (Baretti and Le, 2018). As expected, studies have indicated that plant MMR deficiency also displayed MSI, such as deficiency of MSH2 (Leonard et al., 2003; Hoffman et al., 2004) and PMS1 (Alou et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2012).

Genetic recombination involves the genetic information exchange between highly similar DNA sequences, which can create both novel alleles and new combinations of alleles (Puchta and Hohn, 1996). Such novel variations can be useful both for plant adaptation to environment and variety improvement. Studies in yeast and mammalian have shown that the MMR system is involved in limiting recombination between diverged sequences by recognizing mismatches and interfering with the formation and/or extension of heteroduplex intermediates, triggering either helicase-driven unwinding or immediate resolution of the heteroduplex intermediates (Chen and Jinks-Robertson, 1999; Kolas and Cohen, 2004), a function that has been termed as anti-recombination (Surtees et al., 2004). The anti-recombination role of MMR genes are relatively well studied in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. The loss of AtMSH2 and AtPMS1 activities led to increases in homeologous recombination between sequences of varying divergence (Li et al., 2006, 2009). AtMSH2 was reported to be involved in the suppression of somatic recombination between divergent direct repeats and between homologs from different ecotypes (Emmanuel et al., 2006) and its mutation induced a significant increase in intrachromosomal recombination between highly diverged sequences in germinal tissues (Lafleuriel et al., 2007). Studies on anti-recombination function of MMR genes in other plants have been relatively limited, only reported in tomato and moss Physcomitrella patens (Trouiller et al., 2006; Tam et al., 2011).

Rice is an important food crop. Its MMR genes have been annotated in Rice Annotation Project Database (RAPD)1 and 12 MMR genes have been identified in rice genome using similarity searches and conserved domain analysis (Singh et al., 2010), one of which is OsMSH6 (LOC_Os09g24220), a homolog to AtMSH6 (At4g02070) in the MMR system of A. thaliana. However, no information is available for the MSH6 gene function in maintaining genome stability in plants including A. thaliana. With the aim of deciphering its role in genetic stability and recombination, we have demonstrated that OsMSH6 plays an important role in ensuring genome stability by recognizing mismatches arising spontaneously in rice (Cui et al., 2017). Herein, we reported the effects of OsMSH6 disruption on microsatellite stability and homeologous recombination in rice.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

By a BLAST search against flanking sequences in Rice Tos17 Insertion Mutant Database2, insertion mutant seeds of OsMSH6 (LOC_Os09g24220) gene were introduced from National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences, Japan. Three homozygous insertion mutants derived from Nipponbare, NF9010, NF7784 and ND6011 with the Tos17 insertion position at 1st exon, 8th exon and 3′-UTR respectively, were obtained at T3 generation after molecular analyses (Li et al., 2012). The wild type, MSH6WT without Tos17 insertion derived from the segregating generation, was used as the control to eliminate the mutations in mutants caused by the somaclonal variation during the tissue culture. Three BCF2 populations, obtained by crosses and backcrosses of MSH6WT, ND6011 or NF9010 with Zaoxian B (ZXB, an indica variety) respectively, were used for homeologous recombination assay.

DNA Extraction and Mutant Identification

Genomic DNA was extracted from leaves according to a modified CTAB method described by Murray and Thompson (1980) and adjusted to a final concentration of 25 ng/μL after quantification using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometry (Thermo Scientific, United States). The DNA quality was further confirmed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis at 90 V for 30 min.

The mutants were characterized by triple-primer PCR (polymerase chain reaction) (Figure 1). Reaction system (20 μL) contained ∼50 ng template DNA and 0.4 μM of each primer in 2 × Taq Master Mix (TOYOBO, Japan). The PCR program used included a hot start of 5 min at 94°C followed by 30 cycles of 45 s denaturation at 94°C, 45 s at 60°C (ND6011 for 58°C) annealing, 1 min polymerization at 72°C, and concluded by 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were detected by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. Forward primer (FP) and reverse primer (RP) (Supplementary Table 1) at upstream and downstream of the Tos17 insertion position were designed using the NCBI software3. Tos17 insertion position primer (TP) (Supplementary Table 1), a specific sequence primer located at the conjunction of rice genome with the inserted Tos17, was adopted from the Gramene data resource4.

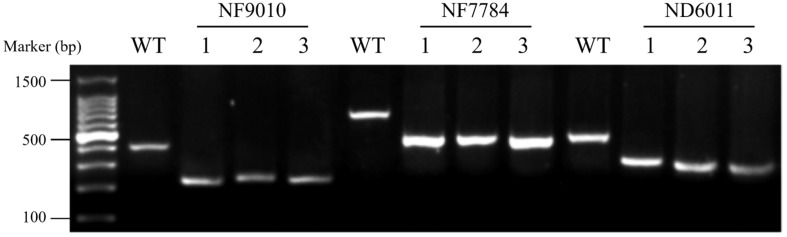

FIGURE 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of triple-primer PCR products amplified from insertion mutants. WT: MSH6WT. 1 to 3: three independent plants from the insertion mutants of NF9010, NF7784, and ND6011, respectively. Product size: NF9010FP/NF9010RP (424 bp), TP/NF9010RP (249 bp), NF7784FP/NF7784RP (765 bp), TP/NF7784RP (524 bp), ND6011FP/ND6011RP (530 bp), TP/NF9010RP (342 bp).

RNA Extraction and Transcriptional Expression Assay

Total mRNA was extracted according to the method described by Jiang et al. (2019a; 2019b). Seedlings were cultured in 1 × Murashige and Skoog liquid medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) at 30°C under long day conditions (16 h/8 h light/dark). Total RNAs were extracted from leaf tissues of 10-day-old (10d), 15-day-old (15d) and 20-day-old (20d) seedlings at midday using the RNeasy Plant RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). cDNAs were synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using the oligo(dT18) primer and GoScriptTM Reverse Transcription System Kit (Promega, United States).

The sequences and the position of primers used for reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) were shown in Figure 2A and Supplementary Table 1. The RT-PCR system was performed using ∼25 ng template cDNA from 20-day-old plants, 0.5 μM of each primer, 10 μL 2 × Taq Master Mix (TOYOBO, Japan), and adding ddH2O to 20 μL. The PCR program used included a hot start of 5 min at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of 45 s denaturation at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C annealing, 1 min polymerization at 72°C, and concluded by 10 min at 72°C. The rice ACTIN gene (OsACTIN, LOC_Os03g50885) was used as control and the RT-PCR products were detected by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

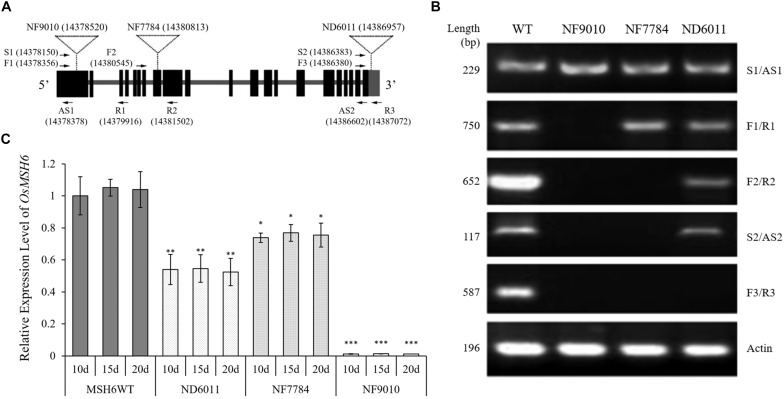

FIGURE 2.

Identification of Tos17 insertion mutants of OsMSH6 gene. (A) Schematic diagram of OsMSH6 with the positions of the inserted Tos17 and primers (the number in brackets represents location of Tos17 insertion and primers on chromosome 9 in DNA Database IRGSP-1.0). (B) Reverse transcription analysis of OsMSH6 in OsMSH6 mutants (NF9010, NF7784 and ND6011) and MSH6WT. (C) Expression levels of OsMSH6 in 10-day-old (10d), 15-day-old (15d), and 20-day-old (20d) were analyzed with six biological replicates. The expression level was first normalized to the internal control gene OsACTIN and reported relative to the expression level of OsMSH6 in 10d MSHWT (assigned a value of 1). Error bars represent standard error. ∗, ∗∗, and ∗∗∗ represent significance between the materials and 10d MSHWT at P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively.

The primer pair F1/R1 (Figure 2A and Supplementary Table 1) was used for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) to detect the transcriptional expression level of OsMSH6 by using a SYBR Green GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (Promega, United States). The OsACTIN gene was used as an internal control and relative expression levels were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). All measurements were completed using six biological replicates, and statistical analyses were conducted using the Student’s t-test.

Microsatellite Analysis

Four independent lines of each mutant in T6 generation were randomly selected for collection of leaf tissues. Leaf sample from eight plants in each line of mutants, as well as the control, were collected and mixed to extract DNA for SSR amplification by PCR. PCR reactions were carried out in a 15 μL volume containing ∼50 ng DNA and 0.4 μM of each primer in 2 × Taq Master Mix (TOYOBO, Japan). The PCR program used included a hot start of 5 min at 94°C followed by 30 cycles of 1 min denaturation at 94°C, 1 min at suitable temperature annealing, 1 min polymerization at 72°C, and concluded by 10 min at 72°C. Sixty microsatellites distributed on chromosomes 1, 3 6, 8, 9, and 10 were randomly selected and analyzed for stability. Sequences of the various primers used in present study were showed in Supplementary Table 2. The PCR products were then separated by 8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Figure 3) and visualized by silver-staining according to Liu et al. (2007).

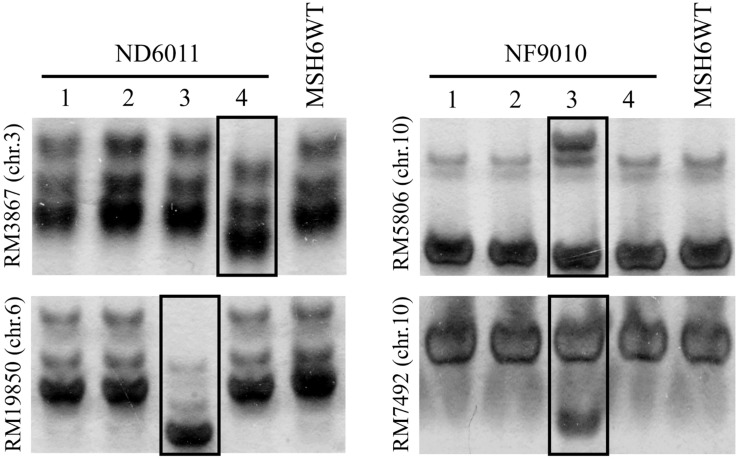

FIGURE 3.

Examples of genomic stability in OsMSH6 mutants and MSH6WT. 1 to 4: four independent lines. The varied microsatellite is marked in the box.

Homeologous Recombination Assay

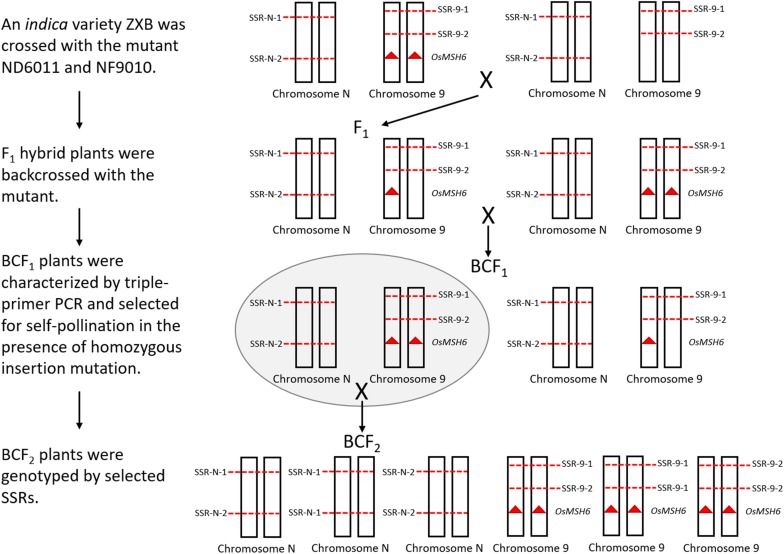

Sixty-eight SSRs distributed on chromosome 1, 3, 9, and 10 were screened to detect polymorphism between ZXB and each mutant or the control. Ten polymorphic SSRs relatively evenly distributed on each chromosome mentioned above were selected to mapping for three BCF2 populations (Figure 4). An indica variety ZXB was crossed with the mutants ND6011 and NF9010. F1 hybrid plants were backcrossed with the mutants. BCF1 plants were characterized by triple-primer PCR and selected for self-pollination in the presence of homozygous insertion mutation. Meanwhile, a BCF2 segregating population was also constructed with the wild type (MSH6WT) background as the control. For each BCF2 population (ND6011/ZXB, NF9010/ZXB and MSH6WT/ZXB), 200 plants were genotyped using the polymorphic SSRs (Supplementary Table 3). MAPMAKER version 3.0 was used to estimate recombination fractions using a threshold LOD score of 3.0 for detecting linkage. Map distances were calculated using the Kosambi mapping function. Results from different populations (the wild type control and mutant populations) were compared for significant differences using the t-test.

FIGURE 4.

A whole schematic figure explaining how the segregating population was obtained. The mutants with Tos 17 inserted OsMSH6 gene mutation (red triangle) is on the left side in the top row. Chromosome 9 represents the OsMSH6 gene located chromosome, and Chromosome N represents other chromosomes (1, 3, and 10). SSR-N represents an SSR marker located on Chromosome N, and SSR-9 represents an SSR marker located on Chromosome 9. On the right side in the top row is an indica variety ZXB without Tos 17 inserted OsMSH6 gene mutation.

Results

Molecular Identification of Homozygous Insertion Mutants

Three Tos17 insertion mutants, NF9010, NF7784, and ND6011 were characterized by triple-primer PCR and RT-PCR. The Tos17 insertions in OsMSH6 gene were confirmed as homozygous state using triple-primer PCR method (Figure 1). In both NF9010 and NF7784 mutant seedlings, partial OsMSH6 mRNA transcripts were detected with primer sets in upstream region of the insertion site (Figure 2B). However, it was not detectable with primer sets in the downstream region or across the insertion site, indicating that NF9010 and NF7784 lacked full length functional mRNA. Transcripts were detectable with primer sets in the upstream, internal and downstream fragments of coding region in ND6011 mutant, but no transcript was detected with the primer set across the insertion site, suggesting that mutant ND6011 lacked a fragment in 3′ untranslated region (Figure 2B).

We further detected OsMSH6 expression levels in seedlings at different growth time by qRT-PCR (Figure 2C). The results revealed significant difference of OsMSH6 expression levels between the OsMSH6 mutant and MSH6WT, while no difference among different growth time (10d, 15d, and 20d) was observed in each mutant or control (Figure 2C).

Microsatellite Instability in the OsMSH6 Mutants

Sixty mapped SSR primer pairs (Supplementary Table 2) were used to investigate possible microsatellite instability in three mutant lines. Out of sixty microsatellites totally analyzed, 15 (25%) SSRs were polymorphic between OsMSH6 mutant and MSH6WT (Table 1), with nine, six and two in NF9010, ND6011, and NF7784, respectively. The polymorphic forms included not only the increasing number of bands, but also the displacement of the main band position (Figure 3). The polymorphism suggested that SSR variations were induced by the OsMSH6 mutation.

TABLE 1.

The microsatellites displayed variations in OsMSH6 mutants.

| Microsatellites | Chromosome | Repeat motif | Variation | Mutants |

| RM2334 | 3 | (AT)25 | Contraction | ND6011, NF9010 |

| RM15362 | 3 | (TC)12 | Contraction | ND6011 |

| RM3867 | 3 | (GA)30 | Contraction | ND6011, NF9010 |

| RM19850 | 6 | (CT)15 | Contraction | ND6011 |

| RM8271 | 8 | (AG)32 | Contraction | NF9010 |

| RM6027 | 8 | (CCG)8 | Contraction | NF9010 |

| RM25701 | 10 | (CT)13 | Contraction | NF7784 |

| RM7492 | 10 | (TATC)7 | Contraction | NF9010 |

| RM25271 | 10 | (TC)17 | Contraction | NF9010 |

| RM3291 | 3 | (CT)14 | Expansion | NF7784 |

| RM6676 | 3 | (TAA)8 | Expansion | NF9010 |

| RM3724 | 6 | (GA)16 | Expansion | ND6011 |

| RM7311 | 6 | (CAAT)6 | Expansion | ND6011 |

| RM5806 | 10 | (AGG)9 | Expansion | NF9010 |

| RM271 | 10 | (GA)15 | Expansion | NF9010 |

We further analyzed the location, repeat motifs and direction of microsatellite variation (Table 1). No polymorphic microsatellite was found on chromosome 1 and 9, while five, three, two, and five polymorphic SSRs were found on chromosome 3, 6, 8, and 10, respectively. Theses varied microsatellites included 10 di-nucleotide-repeats, three tri-nucleotide repeats and two tetra-nucleotide-repeats, accounting for 26.3% (10/38), 16.7% (3/18), and 50.0% (2/4), respectively. Totally we analyzed 29 types of repeat motifs and found ten (34.5%) displayed variations in repeat length, including five di-nucleotide-repeat motifs (GA, CT, AG, TC, and AT), three tri-nucleotide-repeat motifs (CCG, TAA, and AGG) and two tetra-nucleotide-repeat motifs (TATC and CAAT). Among these fifteen varied microsatellites, nine (60%) showed contraction variations and six (40%) showed expansions. On average, the original length of repeats showing contraction and expansion was 37.8 and 27.5 bp, respectively.

Effects on Homeologous Recombination

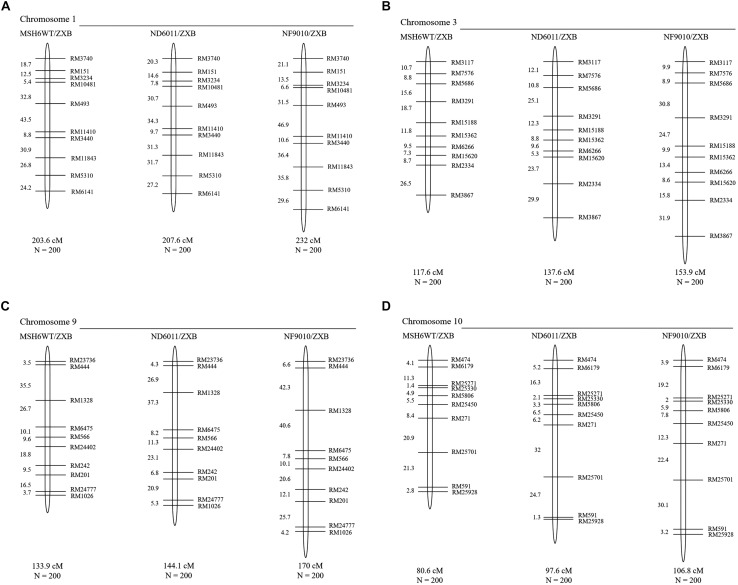

The total map length of four chromosomes was about 535.7 cM in the control (MSH6MT/ZXB) population, with 203.6 cM, 117.6 cM, 133.9 cM and 80.6 cM for chromosome 1, 3, 9, and 10, respectively (Figure 5). When compared to the control population, homeologous recombination was found to be increased in two BCF2 populations with the mutant background (Figure 5 and Table 2). In ND6011/ZXB population, the total map length was increased by 51.2 cM (9.6%), but it was not significant. However, a significant increase (77.6 cM, 13.2%) was observed in total map length for NF9010/ZXB population. These results indicated that OsMSH6 plays an important role in restricting homeologous recombination.

FIGURE 5.

Genetic linkage maps of MSH6WT/ZXB, ND6011/ZXB and NF9010/ZXB based on recombination in BCF2 progeny. Genetic distances are in Kosambi map units, with total genetic length (cM) and the total number of individuals (N) in each BCF2 mapping population represented below the chromosome. (A–D) Represent the genetic linkage maps of chromosome 1, 3, 9 and 10, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Homeologous recombination in BCF2 populations derived from ZXB (a variety of indica rice) crossed and backcrossed with Msh6WT (control), ND6011, NF9010.

| Chromosome | Marker interval (cM) | MSH6WT/ZXB (control) | ND6011/ZXB | NF9010/ZXB |

| 1 | RM3740 - RM151 | 18.7 | 20.3 | 21.1 |

| RM151 – RM3234 | 12.5 | 14.6 | 13.5 | |

| RM3234 – RM10481 | 5.4 | 7.8 | 6.6 | |

| RM10481 – RM493 | 32.8 | 30.7 | 31.5 | |

| RM493 – RM11410 | 43.5 | 34.3 | 46.9 | |

| RM11410 – RM3440 | 8.8 | 9.7 | 10.6 | |

| RM3440 – RM11843 | 30.9 | 31.3 | 36.4 | |

| RM11843 – RM5310 | 26.8 | 31.7 | 35.8 | |

| RM5310 – RM6141 | 24.2 | 27.2 | 29.6 | |

| Total map length (cM) | 203.6 | 207.6 | 232 | |

| % Change from control | 1.96 (P = 0.376) | 13.95** (P = 0.008) | ||

| 3 | RM3117 – RM7576 | 10.7 | 12.1 | 9.9 |

| RM7576 – RM5686 | 8.8 | 10.8 | 8.9 | |

| RM5686 – RM3291 | 15.6 | 25.1 | 30.8 | |

| RM3291 – RM15188 | 18.7 | 12.3 | 24.7 | |

| RM15188 – RM15362 | 11.8 | 8.8 | 9.9 | |

| RM15362 – RM6266 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 13.4 | |

| RM6266 – RM15620 | 7.3 | 5.3 | 8.6 | |

| RM15620 – RM2334 | 8.7 | 23.7 | 15.8 | |

| RM2334 – RM3867 | 26.5 | 29.9 | 31.9 | |

| Total map length (cM) | 117.6 | 137.6 | 153.9 | |

| % Change from control | 17.01 (P = 0.169) | 30.87* (P = 0.025) | ||

| 9 | RM23736 – RM444 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 6.6 |

| RM444 – RM1328 | 35.5 | 26.9 | 42.3 | |

| RM1328 – RM6475 | 26.7 | 37.3 | 40.6 | |

| RM6475 —- RM566 | 10.1 | 8.2 | 7.8 | |

| RM566 – RM24402 | 9.6 | 11.3 | 10.1 | |

| RM24402 – RM242 | 18.8 | 23.1 | 20.6 | |

| RM242 – RM201 | 9.5 | 6.8 | 12.1 | |

| RM201 – RM24777 | 16.5 | 20.9 | 25.7 | |

| RM24777 – RM1026 | 3.7 | 5.3 | 4.2 | |

| Total map length (cM) | 133.9 | 144.1 | 170 | |

| % Change from control | 7.62 (P = 0.272) | 26.96* (P = 0.022) | ||

| 10 | RM474 – RM6179 | 4.1 | 5.2 | 3.9 |

| RM6179 – RM25271 | 11.3 | 16.3 | 19.2 | |

| RM25271 – RM25330 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 2 | |

| RM25330 – RM5806 | 4.9 | 3.3 | 5.9 | |

| RM5806 – RM25450 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 7.8 | |

| RM25450 – RM271 | 8.4 | 6.2 | 12.3 | |

| RM271 – RM25701 | 20.9 | 32 | 22.4 | |

| RM25701 – RM591 | 21.3 | 24.7 | 30.1 | |

| RM591 – RM25928 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 3.2 | |

| Total map length (cM) | 80.6 | 97.6 | 106.8 | |

| % Change from control | 21.09 (P = 0.106) | 32.51* (P = 0.015) | ||

Level of statistical significance *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. P-values given are for one-tailed test.

The increase rates varied with the chromosome. In ND6011/ZXB population, the map length of chromosome 1, 3, 9, and 10 was increased by 1.96% (4.0 cM, P = 0.376), 17.01% (20.0 cM, P = 0.169), 7.62% (10.2 cM, P = 0.272) and 21.09% (17.0 cM, P = 0.106), respectively, though not significant for all chromosomes. While in NF9010/ZXB population, the increase rate was 13.95% (28.4 cM, P = 0.008), 30.87% (36.3 cM, P = 0.025), 26.96% (36.1 cM, P = 0.022), and 32.51% (28.0 cM, P = 0.015) for chromosome 1, 3, 9, and 10, respectively (Table 2). All chromosomes showed a same tendency of increase rates in the two populations with the mutant background: the largest increase rate on chromosome 10 followed in order by chromosome 3, chromosome 9 and chromosome 1.

Compared to the control, different marker intervals did not show consistent changes in two BCF2 populations with the mutant background. Totally 36 marker intervals were assessed. Generally, the NF9010/ZXB BCF2 population showed more increased marker intervals (31) in map distances than the ND6011/ZXB BCF2 population (25). Twenty-six marker intervals were only consistently observed in the two populations, 23 showing increases and 3 showing decreases in map length. For the remaining 10 marker intervals, no particular trend was apparent with one population recording increases while another showing decreases in map distances (Figure 5 and Table 2).

Discussion

As MSH6, an important part of the MMR system, can repair a variety of deletions, insertions and mis-incorporation created during DNA synthesis (Iyer et al., 2006; Li, 2008; Spampanito et al., 2009), it would be expected that the inactivation of OsMSH6 could impact the genome stability and increased recombination rates in rice. Indeed, we observed the MSI in the genome and increased recombination rates on four chromosomes under OsMSH6 mutation background.

DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency can cause dissociation of the nascent strand and the template during replication, and high mutation rate in microsatellites by failing to correct replication errors (Schlötterer, 2000; Li et al., 2002; Hawk et al., 2005). It has been reported that microsatellite instability can be used as a hallmark of MMR gene deficiency (Sia et al., 1997). DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency results in a strong mutator phenotype and high-frequency microsatellite instability (MSI-H) in Homo sapiens and other species (Imai and Yamamoto, 2008). In plants, MSI has often been related to MMR deficiency. For example, deficiency of MSH2 and PMS1 may cause high MSI (Leonard et al., 2003; Alou et al., 2004; Hoffman et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2012). Our result is similar to these reports mentioned above. We examined 60 microsatellites and found fifteen polymorphic SSRs between OsMSH6 mutants and MSH6WT (Table 1), which revealed that OsMSH6 mutations induced microsatellite instability. Thus, it demonstrated that the OsMSH6 is an MMR gene that plays an important role in maintaining SSR stability. The result also further proves the conclusion in our previous research that the OsMSH6 is important in ensuring genome stability by recognizing and repairing mismatches that arise spontaneously in rice by specific-locus amplified fragment (SLAF) sequencing (Cui et al., 2017). Among the polymorphic microsatellites observed in this research, the number of contractions SSR was a little higher than the expansion (Table 1), but the difference was not significant. So, it seemed no obvious preference to contraction or expansion of SSR variations induced by OsMSH6 mutation in rice.

In present research, we found that disruption of rice MMR gene OsMSH6 by Tos 17 insertion was associated with modest but significant increase rate in homeologous recombination (Figure 5 and Table 2). This result was consistent with the effects of other MMR genes reported in different plants, such as MSH2 in Physcomitrella patens (Trouiller et al., 2006), Arabidopsis (Emmanuel et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006, 2009; Lafleuriel et al., 2007) and tomato (Tam et al., 2011), MSH7 in tomato (Tam et al., 2011), MLH1 and PMS1 in Arabidopsis (Dion et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009). It was proved that the MMR gene MSH6 has an important anti-recombination role in yeast (Nicholson et al., 2000) and mice (Barreraoro et al., 2008). However, its possible role in homeologous recombination has not been investigated in plants. Here our data in manner of map distance showed the anti-recombination activity of MSH6 gene in rice. Disruption of OsMSH6 resulted in significantly increased recombination rates (9.6 and 13.2% greater than controls for two mutants) (Table 2). Modest increases in recombination rates observed in our study suggest that the OsMSH6 is a minor suppressor of homeologous recombination.

The increased rate in homeologous recombination observed in our study, ranging from 2.0 to 32.5% for different chromosomes compared to the control (Table 2), was similar to that reported in tomato (Tam et al., 2011). However, it was much lower than reported in Arabidopsis thaliana (Dion et al., 2007; Lafleuriel et al., 2007; Li et al., 2006, 2009). Different magnitudes of increase in homeologous recombination in our research could be caused by several factors.

One is that we investigated a different MMR gene. The MSH2 is a key subunit in MMR and the constant component of the heterodimers formed with MutS proteins such as MSH3, MSH6, and MSH7 (Harfe and Jinks-Robertson, 2000; Wu et al., 2003). Therefore, the MSH2 is essential for all kinds of mismatch recognition complexes to function and its deficiency would be expected to cause bigger effects on recombination rates compared to MSH3, MSH6, or MSH7. Indeed, it has been reported that MSH2 showed higher anti-recombination activity than MSH3, MSH6, and MLH1 in yeast (Chambers et al., 1996; Nicholson et al., 2000) or PMS1 (Selva et al., 1995; Datta et al., 1996) and bigger effects were also observed on recombination rates for MSH2 inactivation, resulting in recombination rate increases by 3-fold (Lafleuriel et al., 2007) or 2 to 7-fold (Li et al., 2006) in A. thaliana. In this study we found its disruption caused recombination rate increase by 2.0 to 32.5% for different chromosomes in rice, which is much lower than that by MSH2 inactivation as mentioned above in A. thaliana. The differences in suppression or expression level of MMR genes may also cause different magnitudes of increase in recombination rates. For example, reduced MSH2 gene expression in tomato via RNAi-induced silencing or dominant negative regulating only showed a modest increase, ranging from 3.8 to 29.2%, lower than that caused by MSH2 inactivation in A. thaliana (Tam et al., 2011). We used two mutants NF9010 and ND6011 for homeologous recombination essay. No functional OsMSH6 mRNA was detected (Figure 2) and significant increases in recombination rates (Figure 5) were observed for the mutant NF9010, while reduced OsMSH6 expression level and less increases in recombination rate were detected for the mutant ND6011. It also suggests that magnitudes of increase in homeologous recombination are related with the disruption or decreasing expression level of MMR gene.

Another important factor is the DNA divergence degree that may cause different magnitudes of recombination increase. Since DNA homology guides meiotic chromosome pairing, the efficiency of homologous can be dramatically reduced by sequence divergence between chromosomes in plants (Bozza and Pawlowski, 2008). MMR proteins inhibit recombination between highly diverged DNA sequences, which requires a less stringent requirement for DNA strand complementarity and higher tolerance for mismatches when recombination intermediates form during recombinational strand exchange/strand transfer (Worth et al., 1994). Trouiller et al. (2006) reported that 3% divergence between recombination substrates leads to a reduction of about 20% in the frequency of gene targeting in wild type moss while no reduction was observed in an MSH2 mutant. Li et al. (2006) showed that the loss of AtMSH2 activity leads to a 2 to 9-fold increase in the frequency of intrachromosomal recombination with constructs containing 0.5, 2, 4, or 9% divergence between the recombination substrates. Lafleuriel et al. (2007) reported MSH2 mutation caused a three-fold increase in intrachromosomal recombination between highly diverged sequences (13%) in germinal tissues. Based on the reports mentioned above, the increase in recombination frequency by AtMSH2 mutation was smaller at low levels of divergence, but it became higher with more linear at higher levels of DNA divergence in A. thaliana. We checked the average SNP number per Kb on chromosome 1, 3, 9, and 10 between Nippobare (a japonica variety) and Kalasath (an indica variety) using SNPseek5. The SNP density on chromosome 1, 3, 9, and 10 was about 10.7, 11.3, 11.7, and 12.5/Kb, respectively. Compared with the sequence divergences listed in reports mentioned above, the divergences were lower as displayed in SNP density on four chromosomes involved in our research. Furthermore, we observed the smallest increase in chromosome 1 (1.96 and 13.95) and the largest increase in chromosome 10 (21.09 and 32.51) in two populations with the mutant background, which fit in well with the divergences of the two chromosomes. Thus, smaller increase rates in recombination could be caused by the lower degree of sequence divergences.

Understanding of recombination mechanisms would greatly facilitate variety improvement by transfers of genetic material from related species (Li et al., 2007; Martinez-Perez and Moore, 2008; Qi et al., 2007; Wijnker and de Jong, 2008). Because of depleted genetic diversity in many crop plants, wide crossing has been considered as an important strategy for crop genetic improvement (Tanksley and McCouch, 1997). In Asian cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.), genetic differentiation between indica and japonica subspecies appears to be a major source of genetic diversity. The intersubspecific indica-japonica hybridization has been proposed as an important strategy for rice breeding and indica-japonica hybrids demonstrate strong heterosis with great promise for breeding of super rice (Lin et al., 2016; Ouyang, 2016). However, the indica-japonica hybridization is hindered by reproductive isolation (Ouyang and Zhang, 2013). Our results suggest that the OsMSH6 mutation can increase homeologous recombination, thus to promote exchanges of genetic material between indica and japonica subspecies, as well as the introgression of beneficial genes from distantly related species. Therefore, the OsMSH6 mutant is significant to such rice breeding programs.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

HC designed the research work. MJ, YS, XW, and HS performed the experiments. MJ and YS analyzed the data together with HC. MJ drafted the manuscript. HC improved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Qingyao Shu, College of Agriculture and Biotechnology, Zhejiang University, for providing original seeds of mutants, and Dr. Yunchao Zheng, College of Agriculture and Biotechnology, Zhejiang University, for helping SNP density analysis.

Funding. The study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0102103) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11175154).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.00220/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ade J., Belzile F., Philippe H., Doutriaux M. P. (1999). Four mismatch repair paralogues coexist in Arabidopsis thaliana: AtMSH2, AtMSH3, AtMSH6-1 and AtMSH6-2. Mol. Genet. Genomics 262 239–249. 10.1007/pl00008640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alou A. H., Azaiez A., Jean M., Belzile F. J. (2004). Involvement of Arabidopsis thaliana atpms1 gene in somatic repeat instability. Plant Mol. Biol. 56 339–349. 10.1007/s11103-004-3472-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baretti M., Le D. T. (2018). DNA mismatch repair in cancer. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 189 45–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreraoro J., Liu T. Y., Gorden E., Kucherlapati R., Shao C., Tischfield J. A. (2008). Role of the mismatch repair gene, MSH6, in suppressing genome instability and radiation-induced mutations. Mutat. Res-Fund. Mol. M 642 74–79. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozza C. G., Pawlowski W. P. (2008). The cytogenetics of homologous chromosome pairing in meiosis in plants. Cytogenet. Genome. Res. 120:313. 10.1159/000121080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers S. R., Hunterk N., Louis E. J., Borts R. H. (1996). The mismatch repair system reduces meiotic homeologous recombination and stimulates recombination-dependent chromosome loss. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16 6110–6120. 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Jinks-Robertson S. (1999). The role of the mismatch repair machinery in regulating mitotic and meiotic recombination between diverged sequences in yeast. Genetics 151 1299–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H., Wu Q., Zhu B. (2017). Specific-locus amplified fragment sequencing reveals spontaneous single-nucleotide mutations in rice OsMsh6 mutants. BioMed. Res. Int. 3:4816973. 10.1155/2017/4816973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culligan K. M., Hays J. B. (2000). Arabidopsis MutS homologs-AtMSH2, AtMSH3, AtMSH6, and a novel AtMSH7-form three distinct protein heterodimers with different specificities for mismatched DNA. Plant Cell 12 991–1002. 10.1105/tpc.12.6.991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta A., Adjiri A., New L., Crouse G. F., Jinks-Robertson S. J. (1996). Mitotic crossovers between diverged sequences are regulated by mismatch repair proteins in Saccaromyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16 1085–1093. 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion E., Li L., Jean M., Belzile F. (2007). An Arabidopsis MLH1 mutant exhibits reproductive defects and reveals a dual role for this gene in mitotic recombination. Plant J. 51 431–440. 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2007.03145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel E., Yehuda E., Melamed-Bessudo C., Avivi-Ragolsky N., Levy A. A. (2006). The role of AtMSH2 in homologous recombination in Arabidopsis thaliana. EMBO Rep. 7 100–105. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui K. (2010). DNA mismatch repair in eukaryotes and bacteria. J. Nucleic Acids 2010:900. 10.4061/2010/260512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez R. L., Spampinato C. P. (2013). Mismatch recognition function of Arabidopsis thaliana MutSγ. DNA Repair 12 257–264. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe B. D., Jinks-Robertson S. (2000). DNA mismatch repair and genetic instability. Annu. Rev. Genet. 34 359–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawk J. D., Stefanovic L., Boyer J. C., Petes T. D., Farber R. A. (2005). Variation in efficiency of DNA mismatch repair at different sites in the yeast genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 8639–8643. 10.1073/pnas.0503415102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. D., Armstrong S. J., Christopher F., Franklin H., Jones G. H. (2004). The Arabidopsis MutS homolog AtMSH4 functions at an early step in recombination: evidence for two classes of recombination in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 18 557–2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman P. D., Leonard J. M., Lindberg G. E., Bollmann S. R., Hays J. B. (2004). Rapid accumulation of mutations during seed-to-seed propagation Arabidopsis of mismatch-repair-defective. Genes Dev. 18 2676–2685. 10.1101/gad.1217204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K., Yamamoto H. (2008). Carcinogenesis and microsatellite instability: the interrelationship between genetics and epigenetics. Carcinogenesis 29:673. 10.1093/carcin/bgm228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer R. R., Pluciennik A., Burdett V., Modrich P. L. (2006). DNA mismatch repair: functions and mechanisms. Chem. Rev. 106 302–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M., Jiang J., Li S., Li M., Tan Y. Y., Song S. Y., et al. (2019a). Glutamate alleviates cadmium toxicity in rice via suppressing cadmium uptake and translocation. J. Hazard. Mater. 384:121319. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M., Liu Y. H., Li R. Q., Zheng Y. C., Fu H. W., Tan Y. Y., et al. (2019b). A suppressor mutation partially reverts the xantha trait via lowered methylation in the promoter of genomes uncoupled 4 in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 10:1003. 10.3389/fpls.2019.01003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jriecny J. (2006). The multifaceted mismatch-repair system. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7 335–346. 10.1038/nrm1907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia R. K., Rai M. K., Kalia S., Singh R., Dhawan A. K. (2011). Microsatellite markers: an overview of the recent progress in plants. Euphytica 177 309–334. 10.1007/s10681-010-0286-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolas N. K., Cohen P. E. (2004). Novel and diverse function of the DNA mismatch repair family in mammalian meiosis and recombination. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 107 216–231. 10.1159/000080600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafleuriel J., Degroote F., Depeiges A., Picard G. (2007). Impact of the loss of AtMSH2 on double-strand break-induced recombination between highly diverged homeologous sequences in Arabidopsis thaliana germinal tissues. Plant Mol. Biol. 63 833–846. 10.1007/s11103-006-9128-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard J. M., Bollmann S. R., Hays J. B. (2003). Reduction of stability of Arabidopsis genomic and transgenic DNA-repeat sequences (microsatellites) by inactivation of AtMSH2 mismatch-repair function. Plant Physiol. 133 328–338. 10.1104/pp.103.023952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. M. (2008). Mechanisms and functions of DNA mismatch repair. Cell Res. 18 85–98. 10.1038/cr.2007.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Hisa A. P., Schnable P. S. (2007). Recent advances in plant recombination. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10 131–135. 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Dion E., Richard G., Domingue O., Jean M., Belzile F. J. (2009). The Arabidopsis DNA mismatch repair gene PMS1 restricts somatic recombination between homeologous sequences. Plant Mol. Biol. 69 675–684. 10.1007/s11103-008-9447-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Jean M., Belzile F. (2006). The impact of sequence divergence and DNA mismatch repair on homeologous recombination in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 45 908–916. 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2006.02657.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. Q., Fu H. W., Cui H. R., Zhang H. L., Shu Q. Y. (2012). Identification of homozygous mutant lines of genes involved in DNA damage repair in rice. J. Nucl. Agric. Sci. 26 409–415. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. C., Korol A. B., Fahima T., Beiles A., Nevo E. (2002). Microsatellites: genomic distribution, putative functions and mutational mechanisms: a review. Mol. Ecol. 11 2453–2465. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2002.01643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. R., Song X. W., Wu M. G., Cheng S. H. (2016). Breeding technology innovation of indica-japonica super hybrid rice and varietal breeding. Sci. Agric. Sin. 49 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q. L., Xu X. H., Ren X. L., Fu H. W., Wu D. X., Shu Q. Y. (2007). Generation and characterization of low phytic acid germplasm in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 114 803–814. 10.1007/s00122-006-0478-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta c (t)) method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett S. T. (2004). Encoded errors: mutations and rearrangements mediated by misalignment at repetitive DNA sequences. Mol. Microbiol. 52 1243–1253. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04076.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Perez E., Moore G. (2008). To check or not to check? The application of meiotic studies to plant breeding. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11 222–227. 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrich P. (1991). Mechanisms and biological effects of mismatch repair. Annu. Rev. Genet. 25:229 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.001305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T., Skoog F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant 15 473–496. [Google Scholar]

- Murray M. G., Thompson W. F. (1980). Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8 4321–4326. 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag D. K., Suri M., Stenson E. K. (2004). Both CAG repeats and inverted DNA repeats stimulate spontaneous unequal sister-chromatid exchange in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 5677–5684. 10.1093/nar/gkh901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson A., Hendrix M., Jinks-Robertson S., Crouse G. F. (2000). Regulation of mitotic homeologous recombination in yeast. Functions of mismatch repair and nucleotide excision repair genes. Genetics 154 133–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Y. D. (2016). Progress of indica-japonica hybrid sterility and wide-compatibility in rice. Chin. Sci. Bull. 61 3833–3841. 10.1073/pnas.0804761105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Y. D., Zhang Q. F. (2013). Understanding reproductive isolation based on the rice model. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64 111–135. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchta H., Hohn B. (1996). From centiMorgans to basepairs: homologous recombination in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1 340–348. 10.1016/s1360-1385(96)82595-0 10751634 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L., Friebe B., Zhang P., Gill B. S. (2007). Homoeologous recombination, chromosome engineering and crop improvement. Chromosome Res. 15 3–19. 10.1007/s10577-006-1108-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlötterer C. (2000). Evolutionary dynamics of microsatellite DNA. Chromosoma 109 365–371. 10.1007/s004120000089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröpfer S., Knoll A., Trapp O., Puchta H. (2014). DNA repair and recombination in plants. Springer 2 51–93. 10.1007/978-1-4614-7570-5_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selva E. M., New L., Crouse G. F., Lahue R. S. (1995). Mismatch correction acts as a barrier to homeologous recombination in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Genetics 139:1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia E. A., Dominska M., Stefanovic L., Petes T. D. (2001). Isolation and characterization of point mutations in mismatch repair genes that destabilize microsatellites in yeast. Mol. Cell Biol. 21:8157. 10.1128/mcb.21.23.8157-8167.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia E. A., Kokoska R. J., Dominska M., Greenwell P., Petes T. D. (1997). Microsatellite instability in yeast: dependence on repeat unit size and DNA mismatch repair genes. Mol. Cell Biol. 17:2851. 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. K., Roy S., Choudhury S. R., Sengupta D. N. (2010). DNA repair and recombination in higher plants: insights from comparative genomics of Arabidopsis and rice. BMC Genomics 11:443. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spampanito C. P., Gomez R. L., Galles C., Lario L. D. (2009). From bacteria to plants: a compendium of mismatch repair essays. Mutat. Res. 682 110–128. 10.1016/j.mrrev.2009.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spampinato C. P. (2017). Protecting DNA from errors and damage: an overview of DNA repair mechanisms in plants compared to mammals. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 74 1–17. 10.1007/s00018-016-2436-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surtees J. A., Argueso J. L., Alani E. (2004). Mismatch repair proteins: key regulators of genetic recombination. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 107 146–159. 10.1159/000080593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam S. M., Hays J. B., Chetelat R. T. (2011). Effects of suppressing the DNA mismatch repair system on homeologous recombination in tomato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 123 1445–1458. 10.1007/s00122-011-1679-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanksley S. D., McCouch S. R. (1997). Seed banks and molecular maps: unlocking genetic potential from the wild. Science 277 1063–1066. 10.1126/science.277.5329.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D. (1989). Hypervaria bility of simple sequences as a general source for polymorphic DNA markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 17 6463–6471. 10.1093/nar/17.16.6463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran H. T., Keen J. D., Kricker M., Resnick M. A., Gordenin D. A. (1997). Hypermutability of homonucleotide runs in mismatch repair and DNA polymerase proofreading yeast mutants. Mol. Cell Biol. 17 2859–2865. 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouiller B., Schaefer D. G., Charlot F., Nogue F. (2006). MSH2 is essential for the preservation of genome integrity and prevents homeologous recombination in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Nucl. Acids Res. 34 232–242. 10.1093/nar/gkj423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney R. K., Graner A., Sorrells M. E. (2005). Genic microsatellite markers in plants: features and applications. Trends Biotechnol. 23 48–55. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnker E., de Jong H. (2008). Managing meiotic recombination in plant breeding. Trends Plant Sci. 13 640–646. 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worth L. J., Clark S., Radman M., Modrich P. (1994). Mismatch repair proteins MutS and MutL inhibit RecA-catalyzed strand transfer between diverged DNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91 3238–3241. 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S. Y., Culligan K., Lamers M., Hays J. B. (2003). Dissimilar mispairrecognition spectra of Arabidopsis DNA-mismatch-repair proteins MSH2∗MSH6 (MutSα) and MSH2∗MSH7 (MutSγ). Nucl. Acids Res. 31 6027–6034. 10.1093/nar/gkg780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Li M., Chen L., Wu G., Li H. (2012). Rapid generation of rice mutants via the dominant negative suppression of the mismatch repair protein OsPMS1. Theor. Appl. Genet. 125 975–986. 10.1007/s00122-012-1888-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.