Abstract

Glioma is the most common tumor of the central nervous system; variation in susceptibility and prognosis worldwide suggests that there are molecular and genetic differences among individuals. The H19 gene plays a dual role in carcinogenesis. In this study, associations between H19 polymorphisms and susceptibility as well as prognosis in glioma were evaluated. In total, 605 patients with glioma and 1,300 cancer-free subjects were enrolled in the study. Individuals with the rs3741219 A>G allele were less likely to develop glioma (relative risk [RR] = 0.54, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 0.45–0.63, p < 0.001), whereas rs217727 G>A and rs2839698 G>A genotypes were not associated with glioma risk. The associations between H19 polymorphisms and prognosis were assessed, including overall survival and progression-free survival. Three focused H19 polymorphisms did not show a significant effect on survival. Further analysis based on false-positive report probability validated these significant results. In the haplotype analysis, individuals with the Grs217727Ars2839698Grs3741219 haplotype were less likely to develop glioma (odds ratio [OR] = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.23–0.46, p = 0.02). Overall, carriers of the rs3741219 AG or GG genotype of H19 have a decreased susceptibility to glioma, but polymorphisms in this gene are not related to prognosis.

Keywords: H19, single nucleotide polymorphisms, glioma, susceptibility, prognosis

Introduction

Glioma, which arises from glial or precursor cells, is one of the most common and highly fatal brain tumors.1,2 According to the biological and clinical characteristics, glioma is classified into four World Health Organization (WHO) grades (I–IV).3 Despite substantial advances in multimodal treatments, including surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, the overall survival (OS) of patients with glioma remains poor,4 and it varies by race or ethnicity.5 The risk factors of glioma include allergies/atopic disease, genetic factors, and ionizing radiation, among others.6,7

Glioma is a typical example of disease, for which molecular and genetic diagnoses affect patient treatment.8 Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) play crucial roles in glioma occurrence and development, including tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, and migration.9,10 Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) contribute to altering the binding of transcription factors, RNA splicers, and gene promoters, thereby regulating gene function.11

H19, a paternally inherited gene located on chromosome 11p15.5, is tightly linked to the insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) gene.12 The imprinted gene H19 does not encode any protein, but it encodes a capped, spliced, polyadenylated, and oncofetal 2.7-kb RNA that is downregulated postnatally.11 Genome-wide association studies have identified inherited risk factors as a feature of brain cancer genetics, and they have indicated that SNPs are usually present in patients with glioma.13 The effect of H19 on carcinogenesis is controversial. Jiang et al.10 found that H19 promotes the invasion and tumorigenicity of glioblastoma cells and could be a therapeutic target for glioblastoma. Three SNPs (rs4930101, rs11042170, and rs27359703) in H19 remarkably increase colorectal cancer susceptibility.14 The rs2071095 in H19 is linked to the risk of breast cancer.15 The rs2839698 might predict the risk and prognosis of hepatocellular cancer.16 In addition, the rs3024270 GG genotype might increase neuroblastoma risk in female Chinese children.17 In contrast, the rs2839698 TC genotype of H19 significantly decreases the risk of bladder cancer.11 Another six-center case-control study stated that none of three SNPs (rs2839698 G>A, rs3024270 C>G, rs217727 G>A) was relevant to the neuroblastoma susceptibility.18

However, the association between H19 SNPs and glioma has not been examined to date. Hence, this hypothesis-driven case-control study aimed to investigate the associations between three SNPs (rs217727 G>A, rs2839698 G>A, and rs3741219 A>G) in H19 and glioma susceptibility and prognosis.

Results

Characteristics of Study Subjects

All 605 patients with glioma (270 females and 335 males) included in this study were of Han Chinese ethnicity. The survival time for patients ranged from 2 to 44 months, with a median survival time of 11 months. In addition, the clinical characteristics included sex, age, WHO grade, history of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy (Table S1). Patients were divided into two groups according to WHO grade: 382 patients (63.1%) with grades I–II, and 223 patients (36.9%) with grades III–IV. A total of 416 patients (68.8%) underwent gross total resection (GTR), and 189 patients (31.2%) underwent subtotal resection (STR) or near-total resection (NTR). Except for 60 patients, all subjects received radiotherapy. Among these patients, 162 patients (26.8%) underwent conformal radiotherapy and 383 patients (63.3%) underwent gamma knife therapy. In total, 250 patients (41.3%) received chemotherapy (124 patients received platinum-based agents, 52 patients received temozolomide, and 74 patients received nimustine), and 355 patients did not receive any chemotherapy. The age and sex distributions in the case and control groups were balanced (p = 0.688 and p = 0.534). Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference in the average age between the case (40.71 ± 18.28 years) and control groups (41.68 ± 13.54 years) (p = 0.195).

Association between H19 Polymorphisms and Glioma Susceptibility

Table 1 presents the genotypes and allele frequencies of H19 in the two groups and their associations with glioma susceptibility, adjusted for sex and age. The genotype frequency distributions of the three polymorphisms conformed to the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) (rs217727, p = 0.80; rs2839698, p = 0.06; rs3741219, p = 0.096).

Table 1.

Genotype Frequencies of H19 Polymorphisms in Cases and Controls

| Model | Genotype | Control (n, %) | Case (n, %) | ORa (95% CI) | p Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs217727 HWE: p = 0.80 | |||||

| Co-dominant | GG | 557 (42.8) | 254 (42.0) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Heterozygote | GA | 591 (45.5) | 278 (45.9) | 1.03 (0.84–1.27) | 0.77 |

| Homozygote | AA | 152 (11.7) | 73 (12.1) | 1.05 (0.77–1.44) | 0.75 |

| Dominant | GG | 557 (42.8) | 254 (42.0) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| GA+AA | 743 (57.2) | 351 (58.0) | 1.04 (0.85–1.26) | 0.72 | |

| Recessive | GG+GA | 1,148 (88.3) | 532 (87.9) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| AA | 152 (11.7) | 73 (12.1) | 1.04 (0.77–1.40) | 0.81 | |

| Overdominant | GG+AA | 709 (54.5) | 327 (54.1) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| GA | 591 (45.5) | 278 (45.9) | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | 0.84 | |

| Allele | G | 1,705 (65.6) | 786 (65.0) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| A | 895 (34.4) | 424 (35.0) | 1.03 (0.89–1.19) | 0.71 | |

| rs2839698 HWE: p = 0.06 | |||||

| Co-dominant | GG | 675 (51.9) | 311 (51.3) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Heterozygote | GA | 504 (38.8) | 240 (39.7) | 1.03 (0.84–1.27) | 0.75 |

| Homozygote | AA | 121 (9.3) | 54 (9.0) | 0.97 (0.68–1.37) | 0.86 |

| Dominant | GG | 675 (51.9) | 311 (51.3) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| GA+AA | 625 (48.1) | 294 (48.7) | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | 0.83 | |

| Recessive | GG+GA | 1,179 (90.7) | 551 (91.0) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| AA | 121 (9.3) | 54 (9.0) | 0.96 (0.68–1.34) | 0.79 | |

| Overdominant | GG+AA | 796 (61.2) | 365 (60.3) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| GA | 504 (38.8) | 240 (39.7) | 1.04 (0.85–1.27) | 0.71 | |

| Allele | G | 1,854 (71.3) | 862 (71.2) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| A | 746 (28.7) | 348 (28.8) | 1.00 (0.86–1.17) | 0.97 | |

| rs3741219 HWE: p = 0.096 | |||||

| Co-dominant | AA | 651 (50.1) | 439 (72.56) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Heterozygote | GA | 520 (40.0) | 107 (17.69) | 0.31 (0.24–0.39) | <0.0001* |

| Homozygote | GG | 129 (9.9) | 59 (9.75) | 0.68 (0.49–0.94) | 0.02* |

| Dominant | AA | 651 (50.1) | 439 (72.56) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| GA+GG | 649 (49.9) | 166 (27.44) | 0.38 (0.31–0.47) | <0.0001* | |

| Recessive | AA+GA | 1,171 (90.1) | 546 (90.25) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| GG | 129 (9.9) | 59 (9.75) | 0.98 (0.71–1.36) | 0.91 | |

| Overdominant | AA+GG | 780 (60.0) | 498 (82.31) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| GA | 520 (40.0) | 107 (17.69) | 0.32 (0.25–0.41) | <0.0001* | |

| Allele | A | 1,822 (70.1) | 985 (81.40) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| G | 778 (29.9) | 225 (18.60) | 0.54 (0.45–0.63) | <0.0001* | |

*p ≤ 0.05 indicates statistical significance. OR = 1 (reference compared with other genotypes). HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted for age and sex.

We applied six genetic models to investigate the association between H19 polymorphisms and glioma risk. All of the inheritance models indicated that rs217727 and rs2839698 were not associated with glioma susceptibility (Table 1). However, all inheritance models revealed that rs3741219 A>G was significantly associated with a decreased risk of glioma, except for the recessive model (heterozygote: GA versus AA, odds ratio [OR] = 0.31, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 0.24–0.39, p < 0.001; homozygote: GG versus AA, OR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.49–0.94, p = 0.02; dominant: GA+GG versus AA, OR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.31–0.47, p < 0.001; overdominant: GA versus AA+GG, OR = 0.32, 95% CI = 0.25–0.41, p < 0.001; allele: A versus G, OR = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.45–0.63, p < 0.001).

Associations between H19 Gene Polymorphisms and Clinical Characteristics

We further analyzed the associations between clinical features in patients with glioma and H19 polymorphisms, stratified by age, sex, tumor sites, and WHO grade (Table 2). This analysis revealed that the GA/AA and AA genotypes of H19 rs217727 in patients aged ≥40 years were less frequent than the GG genotype in patients aged <40 years (GA+AA versus GG: OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.50–0.96, p = 0.03; AA versus GG: OR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.47–0.94, p = 0.02). For rs2839698 and rs3741219, no significant association between polymorphisms and clinical characteristics was observed.

Table 2.

Associations between H19 Gene Polymorphisms and Clinical Characteristics of Glioma Patients

| Characteristics | Genotype Distributions |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | Aa | aa | Aa + aa | |

| rs217727 | ||||

| Age | ||||

| <40/≥40 | 99/155 | 136/142 | 32/41 | 168/183 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref. | 0.67 (0.47–0.94) | 0.82 (0.48–1.39) | 0.70 (0.50–0.96) |

| p valuea | 0.021* | 0.456 | 0.03* | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male/female | 138/116 | 155/123 | 42/31 | 197/154 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref. | 0.94 (0.67–1.33) | 0.88 (0.52–1.48) | 0.93(0.67–1.29) |

| p valuea | 0.741 | 0.628 | 0.661 | |

| WHO grade | ||||

| I+II/III+IV | 155/99 | 184/94 | 43/30 | 227/124 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref. | 0.80 (0.56–1.14) | 1.09 (0.64–1.85) | 0.86 (0.61–1.19) |

| p valuea | 0.216 | 0.744 | 0.359 | |

| rs2839698 | ||||

| Age | ||||

| <40/≥40 | 130/181 | 118/122 | 18/36 | 136/158 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref. | 0.75 (0.53–1.05) | 1.44 (0.80–2.71) | 0.84 (0.61–1.16) |

| p valuea | 0.091 | 0.237 | 0.285 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male/female | 171/140 | 134/106 | 31/23 | 165/129 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref. | 0.96 (0.68–1.35) | 0.90 (0.50–1.61) | 0.95 (0.69–1.31) |

| p valuea | 0.816 | 0.726 | 0.751 | |

| WHO grade | ||||

| I+II/III+IV | 202/109 | 152/88 | 28/26 | 180/114 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref. | 1.07 (0.75–1.52) | 1.71 (0.95–3.07) | 1.17 (0.84–1.63) |

| p valuea | 0.715 | 0.070 | 0.358 | |

| rs3741219 | ||||

| Age | ||||

| <40/≥40 | 197/242 | 46/61 | 24/35 | 70/96 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref. | 1.08 (0.71–1.66) | 1.19 (0.69–2.08) | 1.12 (0.78–1.60) |

| p valuea | 0.725 | 0.543 | 0.550 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male/female | 237/202 | 60/47 | 38/21 | 98/68 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref. | 0.92 (0.60–1.40) | 0.65 (0.36–1.13) | 0.81(0.57–1.17) |

| p valuea | 0.697 | 0.133 | 0.265 | |

| WHO grade | ||||

| I+II/III+IV | 281/158 | 62/45 | 39/20 | 101/65 |

| OR (95% CI) | Ref. | 1.29 (0.84–1.98) | 0.91 (0.51–1.60) | 1.44 (0.79–1.65) |

| p valuea | 0.245 | 0.753 | 0.472 | |

A, wild allele; a, variant allele. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref., reference; WHO, World Health Organization. *p ≤ 0.05.

Univariate logistic regression analysis for the distributions of genotype frequencies. p ≤ 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

False-Positive Report Probability (FPRP) Results

We preset 0.2 as the FPRP threshold. As shown in Table S2, at the prior probability of 0.01, all of the significant findings for the H19 rs3741219 A>G polymorphism (GA versus AA, GG versus AA, GA+GG versus AA, GA versus AA+GG) remained noteworthy. Moreover, the association with the H19 rs3741219 allele variation (A>G) was also noteworthy, with a statistical power of 0.709 and a FPRP value of 0.001.

Haplotype Analysis

As shown in Table 3, we conducted a haplotype analysis to evaluate the joint action of three H19 SNPs. The Grs217727Ars2839698Grs3741219 haplotype was associated with a reduced risk of glioma, compared with the wild-type haplotype G rs217727Grs2839698Ars3741219 (OR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.23–0.46, p = 0.02).

Table 3.

The Haplotype Analysis of Three H19 Gene Polymorphisms (rs217727 G>A, rs2839698 G>A, and rs3741219 A>G)

| Haplotypes | Case (%) | Control (%) | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grs217727Grs2839698Ars3741219 | 189 (31.3) | 463 (35.58) | Ref. | |

| Ars217727Ars2839698Ars3741219 | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.00) | NA | NA |

| Ars217727Ars2839698Grs3741219 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.00) | NA | NA |

| Ars217727Grs2839698Ars3741219 | 178 (29.5) | 445 (34.22) | 0.98 (0.77–1.25) | 0.87 |

| Ars217727Grs2839698Grs3741219 | 30 (5) | 2 (0.16) | NA | NA |

| Grs217727Ars2839698Ars3741219 | 122 (20.2) | 2 (0.18) | NA | NA |

| Grs217727Ars2839698Grs3741219 | 49 (8.1) | 369 (28.42) | 0.33 (0.23–0.46) | <0.0001* |

| Grs217727Grs2839698Grs3741219 | 33 (5.4) | 19 (1.44) | NA | NA |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref., reference; NA, not applicable. *p ≤ 0.05.

Association of H19 Polymorphisms with Glioma Prognosis

We investigated the association between the three SNPs as well as other potential factors and glioma prognosis by univariate Cox analyses. The subgroup analysis was stratified by age, sex, surgery, WHO grade, and history of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. By univariate Cox analyses, no significant association was observed between three H19 polymorphisms and glioma prognosis (OS and progression-free survival [PFS]). However, three factors, including age, chemotherapy, and surgery, were identified as independent prognostic factors of glioma (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Analysis of H19 Gene Polymorphisms and Clinical Features in Glioma Patient Overall Survival

| Characteristics | Patients (n) | Events (n) | Rate (%) | Univariate Analysis |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p Valuea | ||||

| Age | |||||

| <40 years | 267 | 229 | 85.77 | Ref. | Ref. |

| ≥40 years | 338 | 310 | 91.72 | 1.20 (1.01–1.42) | 0.039* |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 335 | 297 | 88.66 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Female | 270 | 242 | 89.63 | 1.08 (0.91–1.28) | 0.355 |

| WHO grade | |||||

| I–II | 382 | 336 | 87.96 | Ref. | Ref. |

| III–IV | 223 | 206 | 92.38 | 1.18 (0.98–1.40) | 0.063 |

| Surgery | |||||

| STR and NTR | 189 | 186 | 98.41 | Ref. | Ref. |

| GTR | 416 | 353 | 84.86 | 0.59 (0.49–0.71) | <0.001* |

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| No | 355 | 333 | 93.80 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Platinum | 124 | 112 | 90.32 | 0.84 (0.68–1.04) | 0.116 |

| Temozolomide | 52 | 30 | 57.69 | 0.32 (0.22–0.48) | <0.001* |

| Nimustine | 74 | 64 | 86.49 | 0.645 (0.49–0.85) | 0.001* |

| Radiotherapy | |||||

| No | 60 | 49 | 81.67 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Conformal Radiotherapy |

162 | 133 | 82.10 | 1.08 (0.77–1.50) | 0.622 |

| Gamma knife | 383 | 357 | 93.21 | 1.17 (0.86–1.58) | 0.303 |

| rs217727 | |||||

| GG | 254 | 226 | 88.98 | Ref. | Ref. |

| GA | 278 | 249 | 89.57 | 1.09 (0.83–1.44) | 0.527 |

| AA | 73 | 64 | 87.67 | 1.14 (0.86–1.50) | 0.357 |

| rs2839698 | |||||

| GG | 311 | 281 | 90.35 | Ref. | Ref. |

| GA | 240 | 211 | 87.92 | 1.00 (0.73–1.36) | 0.974 |

| AA | 54 | 47 | 87.04 | 0.97 (0.71–1.34) | 0.869 |

| rs3741219 | |||||

| AA | 439 | 391 | 89.07 | Ref. | Ref. |

| GA | 107 | 94 | 87.85 | 1.05 (0.84–1.31) | 0.693 |

| GG | 59 | 54 | 91.53 | 1.09 (0.82–1.45) | 0.564 |

OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; STR, subtotal resection; NTR, near-total resection; GTR, gross total resection; Ref., reference. *p ≤ 0.05.

Cox’s proportional hazard regression analysis for univariate analysis. p ≤ 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Table 5.

Analysis of H19 Gene Polymorphisms and Clinical Features in Glioma Patient Progression-Free Survival

| Characteristics | Patients (n) | Events (n) | Rate (%) | Univariate Analysis |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p Valuea | ||||

| Age | |||||

| <40 years | 267 | 239 | 89.51 | Ref. | Ref. |

| ≥40 years | 338 | 324 | 95.86 | 1.19 (1.00–1.40) | 0.047* |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 335 | 310 | 92.54 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Female | 270 | 253 | 93.70 | 1.1 (0.93–1.30) | 0.263 |

| WHO grade | |||||

| I–II | 382 | 353 | 92.41 | Ref. | Ref. |

| III–IV | 223 | 210 | 94.17 | 1.15 (0.97–1.36) | 0.116 |

| Surgery | |||||

| STR and NTR | 189 | 183 | 96.83 | Ref. | Ref. |

| GTR | 416 | 380 | 91.35 | 0.58 (0.48–0.69) | <0.001* |

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| No | 355 | 351 | 98.87 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Platinum | 124 | 116 | 93.55 | 0.99 (0.80–1.22) | 0.916 |

| Temozolomide | 52 | 32 | 61.54 | 0.35 (0.24–0.50) | <0.001* |

| Nimustine | 74 | 64 | 86.49 | 0.73 (0.56–0.96) | 0.022* |

| Radiotherapy | |||||

| No | 60 | 55 | 91.67 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Conformal radiotherapy | 162 | 137 | 84.57 | 1.13 (0.83–1.56) | 0.436 |

| Gamma knife | 383 | 371 | 96.87 | 1.21 (0.91–1.60) | 0.199 |

| rs217727 | |||||

| GG | 254 | 234 | 92.13 | Ref. | Ref. |

| GA | 278 | 261 | 93.88 | 1.00 (0.76–1.30) | 0.973 |

| AA | 73 | 68 | 93.15 | 1.11 (0.85–1.46) | 0.429 |

| rs2839698 | |||||

| GG | 311 | 294 | 94.53 | Ref. | Ref. |

| GA | 240 | 219 | 91.25 | 1.04 (0.77–1.40) | 0.797 |

| AA | 54 | 50 | 92.59 | 0.98 (0.72–1.34) | 0.906 |

| rs3741219 | |||||

| AA | 439 | 408 | 92.94 | Ref. | Ref. |

| GA | 107 | 101 | 94.39 | 1.01 (0.81–1.25) | 0.940 |

| GG | 59 | 54 | 91.53 | 1.08 (0.81–1.44) | 0.595 |

PFS, progression-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; STR, subtotal resection; NTR, near-total resection; GTR, gross total resection; Ref., reference. *p ≤ 0.05.

Cox’s proportional hazard regression analysis for univariate analysis. p ≤ 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

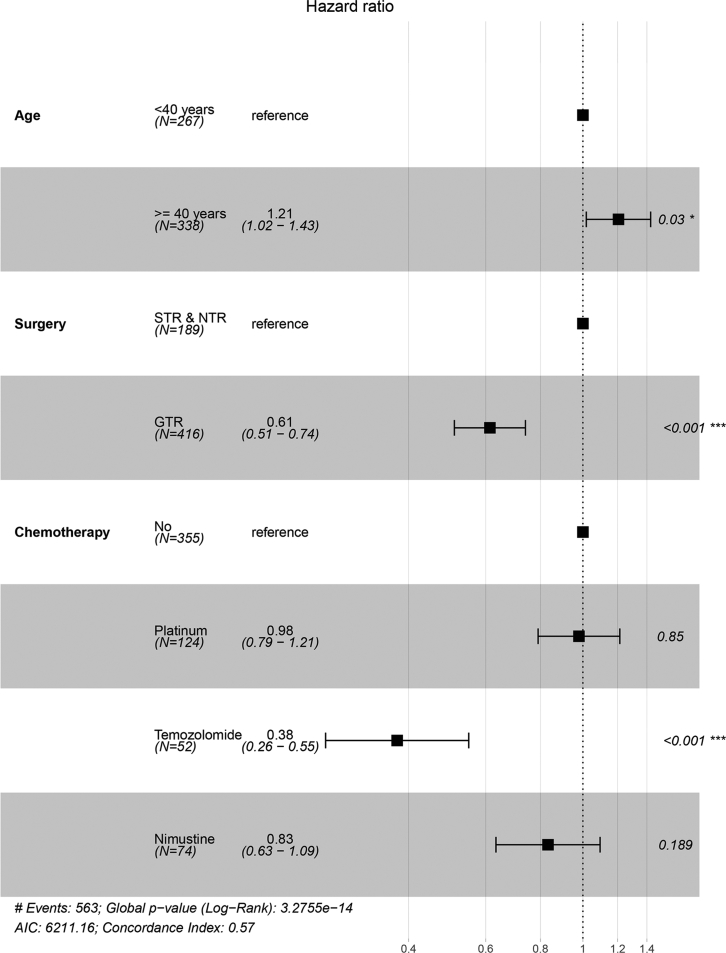

Furthermore, we performed a multivariate Cox analysis of the three factors identified above. As presented in Figures 1 and 2, patients with glioma aged ≥40 years showed worse OS and PFS (OS: hazard ratio [HR] = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.02–1.44, p = 0.029; PFS: HR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.02–1.43, p = 0.03) compared with those of younger patients. In addition, compared with patients who underwent STR or NTR, those who underwent GTR showed better OS and PFS (OS: HR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.51–0.75, p < 0.001; PFS: HR = 0.61, 95% CI = 0.51–0.74, p < 0.001). Furthermore, there was a sizeable difference in prognosis depending on various chemotherapy regimens. Compared with patients who received no chemotherapy as a reference, patients treated with temozolomide or nimustine presented improved OS (temozolomide: HR = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.24–0.52, p < 0.001; nimustine: HR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.56–0.97, p = 0.030). As for PFS, patients who received temozolomide treatment had a longer PFS (HR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.26–0.55, p < 0.001), whereas patients who received platinum or nimustine-based treatment did not show significantly better therapeutic effects.

Figure 1.

Forest Plots of Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis for Overall Survival

STR, subtotal resection; NTR, near-total resection; GTR, gross total resection.

Figure 2.

Forest Plots of Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis for Progression-Free Survival

STR, subtotal resection; NTR, near-total resection; GTR, gross total resection.

In the Kaplan-Meier and log-rank analyses (Figure 3), the three H19 variants showed no association with glioma prognosis (OS: rs217727, p = 0.52; rs2839698, p = 0.99; rs3741219, p = 0.80; PFS: rs217727, p = 0.41; rs2839698, p = 0.88; rs3741219, p = 0.85).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier Analysis of OS and PFS in Three Polymorphisms of the H19 Gene

(A–F) OS of rs217727 (A); OS of rs2839698 (B); OS of rs3741219 (C); PFS of rs217727 (D); PFS of rs2839698 (E); and PFS of rs3741219 (F). OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Discussion

Although the function of H19 has been investigated in the past few years, its exact role in carcinogenesis is controversial. An association between H19 polymorphisms and glioma occurrence or prognosis has never been reported. In our analysis, the role of H19 polymorphisms in the regulation of glioma carcinogenesis was found to be complex. The initiation and development of glioma are influenced by both genetic and external factors. In this hospital-based study, the rs3741219 allele variation of H19 was associated with a decreased risk of glioma occurrence. In addition, the mutant Grs217727Ars2839698Grs3741219 haplotype of H19 could substantially reduce the risk of glioma, mirroring that the rs3741219 A>G variant might play a beneficial role in glioma prevention.

The H19 gene, which encodes a 2.3-kb lncRNA, is essential in embryonic development. Additionally, its expression is generally decreased after birth, with expression restricted to the cardiac and skeletal muscles. H19 is an imprinted gene comprising five exons. Genomic imprinting is a gamete-specific inherited modification that determines allele-specific expression in somatic cells. In addition, loss of imprinting (LOI) in the gene might result in the development of some tumors, but not ubiquitously.19 However, Uyeno et al.12 suggested that LOI of IGF2 but not H19 is related to glioma development. Another study has indicated that c-Myc combines with the conserved E boxes near the imprinted control region of H19, inducing histone acetylation and transcriptional initiation, and increasing the expression of H19.20 Structure determines function, and SNPs can affect promoter activity, mRNA stability, and translation efficiency, all of which, in turn, influence gene expression.21 In addition, the mechanisms of the H19 gene in cancer include sustaining proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, enabling replicative immortality, inducing angiogenesis, activating invasion and metastasis, genomic instability and mutation, and tumor-promoting inflammation, deregulating cellular energetics, and avoiding immune destruction.22 The precise mechanisms deserve further investigation.

The rs217727 polymorphism is located in exon 5 of the H19 gene. rs217727 is related to a significantly increased risk of non-small-cell lung cancer,23 urothelial cell carcinoma,24 bladder cancer,25 breast cancer,26 oral squamous cell carcinoma,27 osteosarcoma,28 and gastric cancer.21 In contrast, another study has suggested that rs217727 polymorphism is related to a low risk of breast cancer.28 It has also been reported that rs217727 C>T shows no association with the occurrence of breast cancer,29 lung cancer,30 and bladder cancer.31 These results provide no consensus on the promoting or protective effect of rs217727 on cancer susceptibility. However, we found that the frequencies of GA+AA and AA genotypes of H19 rs217727 in patients aged ≥40 years were lower than those of the GG genotype in patients aged <40 years, indicating that rs217727 might play various roles in the development of glioma depending on age.

In the present study, both H19 rs217727 and rs2839698 showed no significant association with glioma susceptibility. Previous studies have reported that H19 rs2839698 is not associated with the risk of developing non-small-cell lung cancer,23 oral squamous cell carcinoma,27 and breast cancer.32 Another study revealed that heterozygotes of H19 rs2839698 are more susceptible to hepatocellular carcinoma33 and breast cancer.26 rs2839698 is located within the 3′ untranslated region of the H19 gene. A study in the Netherlands indicated that the rs2839698 polymorphism is associated with a decreased risk of bladder cancer,31 which might be explained by variation in the exon. Exonic regions are related to the conserved secondary structure of the transcript or its binding affinity with interacting elements.

In our analysis, H19 rs3741219 was associated with a reduced risk of glioma. The rs3741219 A/G polymorphism is located within the first exon of H19. Mutant alleles or structural variations in genes are presumed to be important, whereas variants that drive cancers are not unique. Divergent variants in the same gene could produce tumors with different characteristics.8 The specific region of H19 that harbors rs3741219 encodes an antisense transcript named the H19 opposite tumor suppressor (HOTS),34 which is antisense to the H19 transcript and is conserved in primates. The overexpression of HOTS, which is localized within the nucleus and nucleolus, could inhibit the growth of some tumors. The H19 locus could encode a tumor suppressor protein.35 However, there is no evidence for the coexpression of HOTS and H19 in vivo. This complexity of inheritance and translation may partially explain the differences between associations of H19 SNPs with distinct types of cancers.35

Furthermore, according to Cox regression analysis, age, surgery type, and chemotherapy were independent prognostic risk factors for glioma. However, our data indicated that these three H19 gene polymorphisms were not associated with glioma prognosis. A previous study has reported that rs2839698 is related to a poor prognosis in hepatocellular cancer.16 However, post-operative patients with gastric adenocarcinoma harboring the H19 rs2839698 GA genotype had an improved prognosis. Further studies of the association between H19 gene polymorphisms and cancer prognosis are necessary to verify the results.

Using lncRNASNP2 (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/lncRNASNP/), we found that the H19 rs217727 G>A SNP may affect microRNA (miRNA)-lncRNA interactions, resulting in gains and losses of miRNA target sites, forming hsa-miR-4804-5p and hsa-miR-8071, and destroying hsa-miR-3960 and hsa-miR-8071 binding sites on H19. The rs3741219 A>G polymorphism causes the gain of miRNA target sites (including hsa-miR-3187-5p, hsa-miR-1285-3p, hsa-miR-6860, and hsa-miR-612), as well as miRNA target losses (including hsa-miR-4486, hsa-miR-24-1-5p, and hsa-miR-566). A similar genotype-phenotype association was also observed for rs3741219 A>G. This indicated that the H19 rs3741219 A>G SNP creates hsa-miR-1539, hsa-miR-3193, and hsa-miR-146b-3p and damages hsa-miR-1914-5p, hsa-miR-6811-3p, and hsa-miR-6514-3p miRNA binding sites. The specific mechanisms underlying these effects require further investigations.

This study investigated the effect of H19 gene polymorphisms on susceptibility and prognosis of glioma. However, additional studies are needed to verify these results and to address several limitations of our study. The effect of environmental factors on glioma risk might be underestimated, owing to a lack of exposure information. In addition, heterogeneity among individuals in various factors is inevitable. All participants were from northwestern China and were of Han ethnicity, resulting in selection bias. Despite these limitations, our study included the largest sample of patients with glioma to date. Additionally, to our knowledge, this is the first study focused on the association of H19 gene polymorphisms with glioma susceptibility and prognosis.

Taken together, the present data suggest that rs2839698 G>A in the H19 gene is associated with a decreased glioma risk. Additionally, patients carrying the Grs217727Ars2839698Grs3741219 haplotype were less prone to develop glioma. Our results mirror the complexity of H19 functions in glioma initiation and development.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

In total, 1,905 participants of Han Chinese ethnicity (605 patients with glioma and 1,300 controls) were consecutively enrolled in the Department of Neurosurgery at Tangdu Hospital, The Second Affiliated Hospital of The Fourth Military Medical University (Xi’an, China), from September 2010 to May 2014. All patients were pathologically diagnosed with glioma. Furthermore, the patients were not treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery. Healthy controls, without a history of malignancies and underlying disease, were recruited among participants who underwent routine examinations in the same period and were matched with the glioma cases in terms of sex and age. The basic characteristics of the participants, including age, sex, ethnicity, WHO grade, surgery, chemotherapy strategy, and radiotherapy, were collected from medical records or self-administered questionnaires. Furthermore, a monthly follow-up was conducted by telephone and outpatient interviews. All patients provided written informed consent before participation. With respect to prognosis, the outcome indicators of death and disease progression were considered to explore the association between H19 polymorphisms and OS as well as PFS. Patients with glioma included in this study were followed up for 44 months. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University in Zhejiang Province (Hangzhou, China).

SNP Selection and Genotyping

The NCBI dbSNP database and the online tool software SNPinfo were used to select candidate SNPs. Three widely researched SNPs (rs217727 G>A, rs2839698 G>A, and rs3741219 A>G) in the H19 gene were investigated. Peripheral blood was drawn from the participants and stored at −80°C in EDTA tubes for DNA extraction and genotyping. Genomic DNA was extracted using a universal genomic DNA extraction kit (Takara, Kyoto, Japan).36 DNA concentrations were measured by spectrophotometry (DU530 UV/VIS spectrophotometer, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Sequenom MassARRAY assay design 3.0 (Sequenom, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for designing the multiplexed SNP MassEXTEND assay. Genotyping of H19 polymorphisms was performed using the Sequenom MassARRAY RS1000. Sequenom Typer 4.0 was used for data analysis. Investigators were blind to the case-control group information for samples. All participants were genotyped successfully. The primers for the three SNPs are listed in Table S3.

Haplotype Analysis

A haplotype analysis was conducted using SHEsis (http://analysis.bio-x.cn/SHEsisMain.htm).37 There is a lowest frequency threshold for haplotype analysis: any number in (0, 1) could be accepted. Haplotypes with a frequency less than this number will not be considered in analysis, and the default value is usually 0.03. Haplotypes with frequencies of less than 0.03 were not analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

R software (version 3.5.1) was used for statistical analyses, as described in our previous studies.36,38, 39, 40 HWE was assessed by the goodness-of-fit χ2 test. A χ2 test or t test were used to compare the distributions of genotype frequencies between the case and control groups. A logistic regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between SNPs and glioma risk. ORs and their 95% CIs were calculated. To assess prognostic effects, univariate and multivariate Cox analyses were conducted, and HRs with 95% CIs were calculated. Stratified analyses were also conducted by age, sex, surgery, WHO grade, and history of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Moreover, the FPRP analysis was performed to verify the significant results.41,42 All statistical tests used were two-sided, with a significance threshold of p <0.05.

Author Contributions

All authors read, critically reviewed, and approved the final manuscript. Z.D. and J.L. designed the research; Y.D., Y.Z., and J.Y. collected the data; L.Z. and S.Y. performed the statistical analysis; Y.W. and P.X. provided methodological support/advice; L.L., N.L, and D.Z. conducted the experiments; and Y.D. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of our study team for their wholehearted cooperation and the study participants for their wonderful contribution.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2020.02.003.

Contributor Information

Jun Lyu, Email: lyujun2019@163.com.

Zhijun Dai, Email: dzj0911@126.com.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Ostrom Q.T., Gittleman H., Fulop J., Liu M., Blanda R., Kromer C., Wolinsky Y., Kruchko C., Barnholtz-Sloan J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2008–2012. Neuro-oncol. 2015;17(Suppl 4):iv1–iv62. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amirian E.S., Armstrong G.N., Zhou R., Lau C.C., Claus E.B., Barnholtz-Sloan J.S., Il’yasova D., Schildkraut J., Ali-Osman F., Sadetzki S. The Glioma International Case-Control Study: a report from the Genetic Epidemiology of Glioma International Consortium. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016;183:85–91. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louis D.N., Perry A., Reifenberger G., von Deimling A., Figarella-Branger D., Cavenee W.K., Ohgaki H., Wiestler O.D., Kleihues P., Ellison D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molinaro A.M., Taylor J.W., Wiencke J.K., Wrensch M.R. Genetic and molecular epidemiology of adult diffuse glioma. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019;15:405–417. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0220-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostrom Q.T., Cote D.J., Ascha M., Kruchko C., Barnholtz-Sloan J.S. Adult glioma incidence and survival by race or ethnicity in the United States from 2000 to 2014. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1254–1262. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauchet L., Ostrom Q.T. Epidemiology and molecular epidemiology. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2019;30:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiedmann M.K.H., Brunborg C., Di Ieva A., Lindemann K., Johannesen T.B., Vatten L., Helseth E., Zwart J.A. The impact of body mass index and height on the risk for glioblastoma and other glioma subgroups: a large prospective cohort study. Neuro-oncol. 2017;19:976–985. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeWeerdt S. The genomics of brain cancer. Nature. 2018;561:S54–S55. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-06711-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiang K.M., Zhang X.Q., Leung G.K. Long non-coding RNAs: the key players in glioma pathogenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2015;7:1406–1424. doi: 10.3390/cancers7030843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang X., Yan Y., Hu M., Chen X., Wang Y., Dai Y., Wu D., Wang Y., Zhuang Z., Xia H. Increased level of H19 long noncoding RNA promotes invasion, angiogenesis, and stemness of glioblastoma cells. J. Neurosurg. 2016;124:129–136. doi: 10.3171/2014.12.JNS1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brannan C.I., Dees E.C., Ingram R.S., Tilghman S.M. The product of the H19 gene may function as an RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990;10:28–36. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uyeno S., Aoki Y., Nata M., Sagisaka K., Kayama T., Yoshimoto T., Ono T. IGF2 but not H19 shows loss of imprinting in human glioma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5356–5359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonsson P., Lin A.L., Young R.J., DiStefano N.M., Hyman D.M., Li B.T., Berger M.F., Zehir A., Ladanyi M., Solit D.B. Genomic correlates of disease progression and treatment response in prospectively characterized gliomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:5537–5547. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin W., Wang X., Wang Y., Li Y., Chen Q., Hu X., Wu Z., Zhao P., Li S., Zhao H. Functional polymorphisms of the lncRNA H19 promoter region contribute to the cancer risk and clinical outcomes in advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:215. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-0895-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui P., Zhao Y., Chu X., He N., Zheng H., Han J., Song F., Chen K. SNP rs2071095 in LincRNA H19 is associated with breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018;171:161–171. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4814-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang M.L., Huang Z., Wang Q., Chen H.H., Ma S.N., Wu R., Cai W.S. The association of polymorphisms in lncRNA-H19 with hepatocellular cancer risk and prognosis. Biosci. Rep. 2018;38 doi: 10.1042/BSR20171652. BSR20171652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu C., Yang T., Pan J., Zhang J., Yang J., He J., Zou Y. Associations between H19 polymorphisms and neuroblastoma risk in Chinese children. Biosci. Rep. 2019;39 doi: 10.1042/BSR20181582. BSR20181582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y., Zhuo Z.J., Zhou H., Liu J., Zhang J., Cheng J., Zhou H., Li S., Li M., He J. H19 gene polymorphisms and neuroblastoma susceptibility in Chinese children: a six-center case-control study. J. Cancer. 2019;10:6358–6363. doi: 10.7150/jca.37564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monk D., Mackay D.J.G., Eggermann T., Maher E.R., Riccio A. Genomic imprinting disorders: lessons on how genome, epigenome and environment interact. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019;20:235–248. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barsyte-Lovejoy D., Lau S.K., Boutros P.C., Khosravi F., Jurisica I., Andrulis I.L., Tsao M.S., Penn L.Z. The c-Myc oncogene directly induces the H19 noncoding RNA by allele-specific binding to potentiate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5330–5337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang C., Tang R., Ma X., Wang Y., Luo D., Xu Z., Zhu Y., Yang L. Tag SNPs in long non-coding RNA H19 contribute to susceptibility to gastric cancer in the Chinese Han population. Oncotarget. 2015;6:15311–15320. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lecerf C., Le Bourhis X., Adriaenssens E. The long non-coding RNA H19: an active player with multiple facets to sustain the hallmarks of cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019;76:4673–4687. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03240-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang G., Liu Q., Cui K., Ma A., Zhang H. Association between H19 polymorphisms and NSCLC risk in a Chinese Population. J. BUON. 2019;24:913–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang P.J., Hsieh M.J., Hung T.W., Wang S.S., Chen S.C., Lee M.C., Yang S.F., Chou Y.E. Effects of long noncoding RNA H19 polymorphisms on urothelial cell carcinoma development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:1322. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16081322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z., Niu Y. Association between lncRNA H19 (rs217727, rs2735971 and rs3024270) polymorphisms and the risk of bladder cancer in Chinese population. Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 2019;71:161–167. doi: 10.23736/S0393-2249.18.03004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safari M.R., Mohammad Rezaei F., Dehghan A., Noroozi R., Taheri M., Ghafouri-Fard S. Genomic variants within the long non-coding RNA H19 confer risk of breast cancer in Iranian population. Gene. 2019;701:121–124. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2019.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo Q.Y., Wang H., Wang Y. lncRNA H19 polymorphisms associated with the risk of OSCC in Chinese population. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017;21:3770–3774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He T.D., Xu D., Sui T., Zhu J.K., Wei Z.X., Wang Y.M. Association between H19 polymorphisms and osteosarcoma risk. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017;21:3775–3780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdollahzadeh S., Ghorbian S. Association of the study between LncRNA-H19 gene polymorphisms with the risk of breast cancer. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2019;33:e22826. doi: 10.1002/jcla.22826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin Z., Cui Z., Li H., Li J., Zhou B. Polymorphisms in the H19 gene and the risk of lung cancer among female never smokers in Shenyang, China. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:893. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4795-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verhaegh G.W., Verkleij L., Vermeulen S.H., den Heijer M., Witjes J.A., Kiemeney L.A. Polymorphisms in the H19 gene and the risk of bladder cancer. Eur. Urol. 2008;54:1118–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin Y., Fu F., Chen Y., Qiu W., Lin S., Yang P., Huang M., Wang C. Genetic variants in long noncoding RNA H19 contribute to the risk of breast cancer in a southeast China Han population. OncoTargets Ther. 2017;10:4369–4378. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S127962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu E.R., Chou Y.E., Liu Y.F., Hsueh K.C., Lee H.L., Yang S.F., Su S.C. Association of lncRNA H19 gene polymorphisms with the occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes (Basel) 2019;10:506. doi: 10.3390/genes10070506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matouk I., Raveh E., Ohana P., Lail R.A., Gershtain E., Gilon M., De Groot N., Czerniak A., Hochberg A. The increasing complexity of the oncofetal H19 gene locus: functional dissection and therapeutic intervention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:4298–4316. doi: 10.3390/ijms14024298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Onyango P., Feinberg A.P. A nucleolar protein, H19 opposite tumor suppressor (HOTS), is a tumor growth inhibitor encoded by a human imprinted H19 antisense transcript. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:16759–16764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110904108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou L., Dong S., Deng Y., Yang P., Zheng Y., Yao L., Zhang M., Yang S., Wu Y., Zhai Z. GOLGA7 rs11337, a polymorphism at the microRNA binding site, is associated with glioma prognosis. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2019;18:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi Y.Y., He L. SHEsis, a powerful software platform for analyses of linkage disequilibrium, haplotype construction, and genetic association at polymorphism loci. Cell Res. 2005;15:97–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yao L., Zhou L., Deng Y., Zheng Y., Yang P., Wang M., Dong S., Hao Q., Xu P., Li N. Association between genetic polymorphisms in TYMS and glioma risk in Chinese patients: a case-control study. OncoTargets Ther. 2019;12:8241–8247. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S221204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu Y., Zhou L., Deng Y., Li N., Yang P., Dong S., Yang S., Zheng Y., Yao L., Zhang M. The polymorphisms (rs3213801 and rs5744533) of DNA polymerase kappa gene are not related with glioma risk and prognosis: A case-control study. Cancer Med. 2019;8:7446–7453. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deng Y., Zhou L., Li N., Wang M., Yao L., Dong S., Zhang M., Yang P., Hao Q., Wu Y. Impact of four lncRNA polymorphisms (rs2151280, rs7763881, rs1136410, and rs3787016) on glioma risk and prognosis: a case-control study. Mol. Carcinog. 2019;58:2218–2229. doi: 10.1002/mc.23110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He J., Wang M.Y., Qiu L.X., Zhu M.L., Shi T.Y., Zhou X.Y., Sun M.H., Yang Y.J., Wang J.C., Jin L. Genetic variations of mTORC1 genes and risk of gastric cancer in an Eastern Chinese population. Mol. Carcinog. 2013;52(Suppl 1):E70–E79. doi: 10.1002/mc.22013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He J., Zou Y., Liu X., Zhu J., Zhang J., Zhang R., Yang T., Xia H. Association of common genetic variants in pre-microRNAs and neuroblastoma susceptibility: a two-center study in Chinese children. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2018;11:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.