Abstract

Background

Regional differences in acceptance and utilization of MISST by spine surgeons may have an impact on clinical decision-making and the surgical treatment of common degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine. The purpose of this study was to analyze the acceptance and utilization of various minimally invasive spinal surgery techniques (MISST) by spinal surgeons the world over.

Methods

The authors solicited responses to an online survey sent to spine surgeons by email, and chat groups in social media networks including Facebook, WeChat, WhatsApp, and Linkedin. Surgeons were asked the following questions: (I) Do you think minimally invasive spinal surgery is considered mainstream in your area and practice setting? (II) Do you perform minimally invasive spinal surgery? (III) What type of MIS spinal surgery do you perform? (IV) If you are performing endoscopic spinal decompression surgeries, which approach do you prefer? The responses were cross-tabulated by surgeons’ demographic data, and their practice area using the following five global regions: Africa & Middle East, Asia, Europe, North America, and South America. Pearson Chi-Square measures, Kappa statistics, and linear regression analysis of agreement or disagreement were performed by analyzing the distribution of variances using statistical package SPSS Version 25.0.

Results

A total of 586 surgeons accessed the survey. Analyzing the responses of 292 submitted surveys regional differences in opinion amongst spine surgeons showed that the highest percentage of surgeons in Asia (72.8%) and South America (70.2%) thought that MISST was accepted into mainstream spinal surgery in their practice area (P=0.04) versus North America (62.8%), Europe (52.8%), and Africa & Middle East region (50%). The percentage of spine surgeons employing MISST was much higher per region than the rate of surgeons who thought it was mainstream: Asia (96.7%), Europe (88.9%), South America (88.9%), and Africa & Middle East (87.5%). Surgeons in North America reported the lowest rate of MISST implementation globally (P<0.000). Spinal endoscopy (59.9%) is currently the most commonly employed MISST globally followed by mini-open approaches (55.1%), and tubular retractor systems (41.8%). The most preferred endoscopic approach to the spine is the transforaminal technique (56.2%) followed by interlaminar (41.8%), full endoscopic (35.3%), and over the top MISST (13.7%).

Conclusions

The rate of implementation of MISST into day-to-day clinical practice reported by spine surgeons was universally higher than the perceived acceptance rates of MISST into the mainstream by their peers in their practice area. The survey suggests that endoscopic spinal surgery is now the most commonly performed MISST.

Keywords: Lumbar minimally invasive spinal surgery, regional variations

Introduction

The authors of this publication were interested in better understanding regional differences in acceptance and utilization of various minimally invasive spinal surgery techniques (MISST) and how these differences could factor into the clinical decision-making process on a local level when it comes to the choice of surgical treatment of common degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine. While MISST has developed some significant traction among spine surgeons (1-22) in an attempt to lower complication rates of open lumbar spine surgery and among patients (23-26), who are now actively seeking out surgeons and MISST centers (27,28) to receive treatments that are less disruptive to their lives, significant disagreement exists among the stakeholders of this public discussion as to the best choice and effectiveness of the various MISSTs with respect best clinical indications, outcomes and value proposition.

The obvious is embraced and hardly disputed by nearly everyone: MISST at least on the surface has the appearance of fewer postoperative complications, shorter interval for return to work and social reintegration (29). Evidence has emerged to corroborate these ideas from a clinical equivalency point of view stating that MISST outcomes are no worse and at a minimum similar to open surgery (30-51). Initially, however, MISST may be associated with higher direct cost due to additional capital and disposable expenses but may result in an overall lower societal burden in the long run (52). Lower expenditure for un-intended aftercare associated with decompensated cardiopulmonary medical comorbidities or diabetes mellitus often seen following open lumbar spinal surgery (52-58) alongside with less time to postoperative narcotic independence and overall reduced utilization of painkillers has been reported to drive the cost reductions (59). The latter problem is of significance in lieu of the opiate abuse epidemic in the United States (60-62).

Less approach-related access trauma and reduced surgical pain in combination with a recent push by payers to transition simple lumbar decompression surgeries into a more cost-effective outpatient setting have led to a substantial increase of lumbar MISST surgeries (54-58). In comparison to traditional open approaches, application of MISSTs has been shown to be associated with higher patient acceptance (50,52-54) due to fewer anesthesia-related problems (postoperative nausea) (53), and lower exposure to the risk of hospitalization including surgical site complications, medication errors, and hospital-acquired infections. In comparison, MISSTs afford the ability to perform the spinal surgery in an ambulatory surgery center, often under local anesthesia and sedation, with an overall reduced burden and cost to the patient (54-58).

While these overarching goals are universally agreed upon, individual implementation from surgeon to surgeon, institution to institution, or country to country may substantially vary as the application of MISST is carried out in a different demographic, and economic context locally. Also, different competing health care policy agendas may have a supportive or conflictive impact on MISST implementation in various countries. The purpose of this study was to better understand these regional consensus variations by analyzing the current state of acceptance and utilization of MISST by spinal surgeons the world over. It was intended to further future opinion-based research on common yet controversial clinical questions in spinal surgery.

Methods

The authors solicited responses to an online survey via email, and chat groups in social networks including Facebook, WeChat, WhatsApp, and Linkedin. The survey was available online and distributed via a link distributed via these social network media. Upon clicking on the link, the prospective surgeon respondent was taken to the typeform website at www.typeform.com where the survey opened automatically. The survey could be answered on the computer, laptop, and any hand-held devices such as an iPad, or a cellular smartphone. The typeform services were chosen because of its ease of use across multiple user-interface platforms. Survey accessibility on the personal smartphone by the surgeon was considered a significant advantage to facilitate recruitment of respondents, ease of use, and respondents retention and improve survey completion.

The survey consisted of five questions. The first four questions were aimed at clinically relevant information, whereas the fifth question requested demographic information of the respondent including his/her age, country of residence, and practice setting. Instead of user queries with a Likert scale, the survey was constructed of either simple “YES” or “NO” questions, or simple multiple-choice questions some of which with multiple possible answers to facilitate ease of use and to maximize respondent retention once on the web site and survey completion. Surgeons were asked the following five questions:

Do you think minimally invasive spinal surgery is considered mainstream in your area and practice setting?

Do you perform minimally invasive spinal surgery?

What type of MIS spinal surgery do you perform?

If you are performing endoscopic spinal decompression surgeries, which approach do you prefer?

-

Tell us a little about yourself:

What is your gender?

What is your age?

What’s your country of residence?

How many peers/colleagues does your organization have?

The survey ran from October 26 to November 14, 2018. The authors were blinded as to the identity of the responding surgeon at all times. Individual personal identifiers were not recorded. The typeform.com survey created a time-stamp upon initiation of the study and once the completed questionnaire was submitted. Also, a unique network identifier (ID without IP address) was recorded for each responding surgeon. Upon completion of the survey, the responses were downloaded in an Excel file format and imported into IBM SPSS (version 25) statistical software package for further data analysis.

Various statistical cross tabulation methods and statistical measures of association were computed for two-way tables. Descriptive statistic measures were used to calculate the mean, range, and standard deviation as well as percentages. Additional crosstabulation methods were used to assess for any statistically significant association between the different surgeon responses using Pearson Chi-Square and Fisher’s Exact Test. Expected cell counts, continuity corrections, and likelihood ratios were calculated for some analyses. Kappa statistics were performed to test for statistical significance of agreement between the individual responses. As another method to assess for agreement or disagreement between the entered responses, linear regression analysis was performed to determine whether the variances in surgeons’ opinions were normally distributed (agreement) or showed asymmetric distribution (disagreement). The authors also used linear regression analysis in an attempt to measure the presumed consistency of the submitted responses in lieu of unknown sample size required to have sufficient power for clinically meaningful statistical analysis. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. A confidence interval of 95% was considered for all statistical tests.

The responses from spine surgeons to the four clinical questions were analyzed as categorical variables using their country of residence as the data key variable. This allowed plotting percentage differences in opinions amongst spine surgeons from different countries by region using the SPSS “Pie of counts on a map” function. To facilitate statistical analysis, responding surgeons were categorized according to their country of residence into of five global regions of the world: North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa & Middle East. Their percentage breakdown of surgeon responses to the four clinical opinion questions was plotted as pie charts on the world map for the five global regions using the surgeon’s country of residence as the key data variable in the analysis.

Results

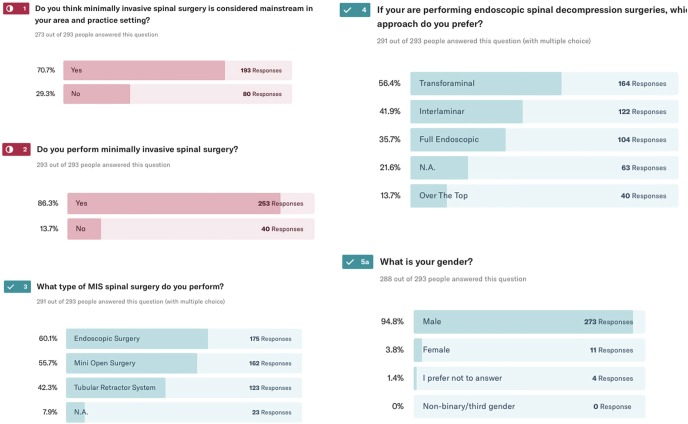

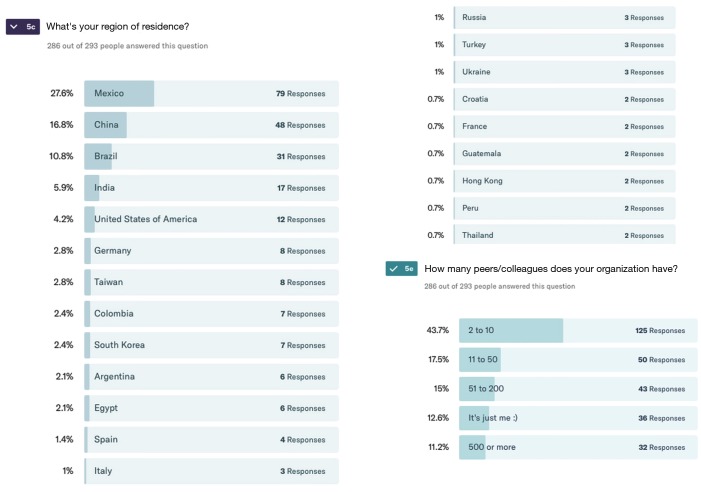

The online survey was access by 586 surgeons of which 293 submitted a survey recording 292 submissions as valid responses. The survey site had 741 total visits. The completion rate was 50.5% and the average time to complete the survey was 03 minutes and 37 seconds. Thirty surgeons completed the survey on a PC or laptop with 54 total and 41 unique visits with a completion rate of 73.2% and average time to complete 03 minutes and 50 seconds. The majority of surgeons [262] responded to the survey using their smartphones during 681 total and 535 unique visits with a completion rate of 49% taking an average time of 03 minutes and 37 seconds to complete. Only one surgeon used a tablet to complete the survey. The vast majority of responding surgeons were male (94.8%) versus female surgeons accounting for 3.8% of respondents (Figure 1). Four surgeons preferred not to indicate their gender (1.4%). The age group crosstabulation by region showed that most responding spinal surgeons were between the age of 34 and 45 years of age in Asia (52.2%), Africa & Middle East (50.0%), North America (36.2%), and South America (33.3%). The majority of responding surgeons in Europe was between the ages of 44 and 55 (38.9%). In descending order (Figure 2), most responding surgeons were from Mexico (27.6%), China (16.8%), Brazil (10.8%), India (5.9%), United States (4.2%), Germany (2.8%), Taiwan (2.8%), Colombia (2.4%), South Korea (2.4%), Argentina (2.1%), Egypt (2.1%), Spain (1.4%), Italy (1%), and other regions (16.8%).

Figure 1.

Responses to questions one through five of the regional variations questionnaire on acceptance, and utilization of minimally invasive spinal surgery techniques among spine surgeons.

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution of responses by region of residence, and the number of peers of responding spine surgeons.

A regional breakdown of responding surgeons (Table 1) showed the majority of them were residing in North America (32.2%) and Asia (31.5%), followed by South America (18.5%), and Europe (12.3%). Concerning their practice setting, 42.8% reported that they worked in groups of 2–10 peers, followed by 17.4% of surgeons indicating they were part of an organization employing 11–50 peers (Table 2). Kappa analysis of agreement and linear regression analysis of showed consistent asymmetric distribution of variances suggesting consistency in the responses as the survey submissions increased over the three-week data acquisition time.

Table 1. Spine surgeon respondent's by region.

| Region | Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa & Middle East | 16 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Asia | 92 | 31.5 | 31.5 | 37.0 |

| Europe | 36 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 49.3 |

| North America | 94 | 32.2 | 32.2 | 81.5 |

| South America | 54 | 18.5 | 18.5 | 100.0 |

| Total | 292 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Table 2. How many peers/colleagues does your organization have?

| Number of peers | Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No answer | 7 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| 11 to 50 | 50 | 17.1 | 17.1 | 19.5 |

| 2 to 10 | 125 | 42.8 | 42.8 | 62.3 |

| 500 or more | 32 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 73.3 |

| 51 to 200 | 42 | 14.4 | 14.4 | 87.7 |

| It’s just me:) | 36 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 100.0 |

| Total | 292 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

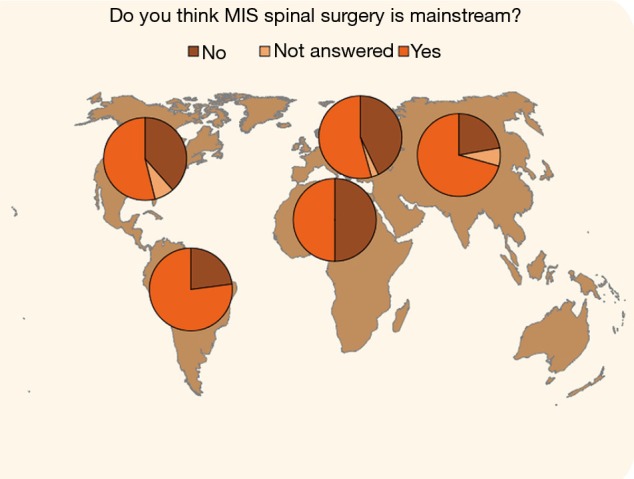

The majority (70.7%) of responding surgeons (273/293) thought that MISST had become mainstream in their practice area (Question 1; Figure 1). A higher percentage (86.3%) of responding surgeons (293/293) admitted to employing MISST in their practice (Question 2; Figure 1). Allowing multiple choice answers, the majority of the 291 responding surgeons indicated that spinal endoscopy (60.1%) is their most commonly employed MISST followed by mini-open approaches (55.7%), and tubular retractor systems (42.3%). Of the surgeons performing endoscopic spinal surgery, responses to another multiple-choice question (Question 4, Figure 1) indicated that the transforaminal approach was the most commonly employed MISST (56.4%) followed by the interlaminar approach (41.9%), full-endoscopic technique (35.7%; combined transforaminal & interlaminar approach), and over the top method (13.7%; unilateral approach bilateral decompression).

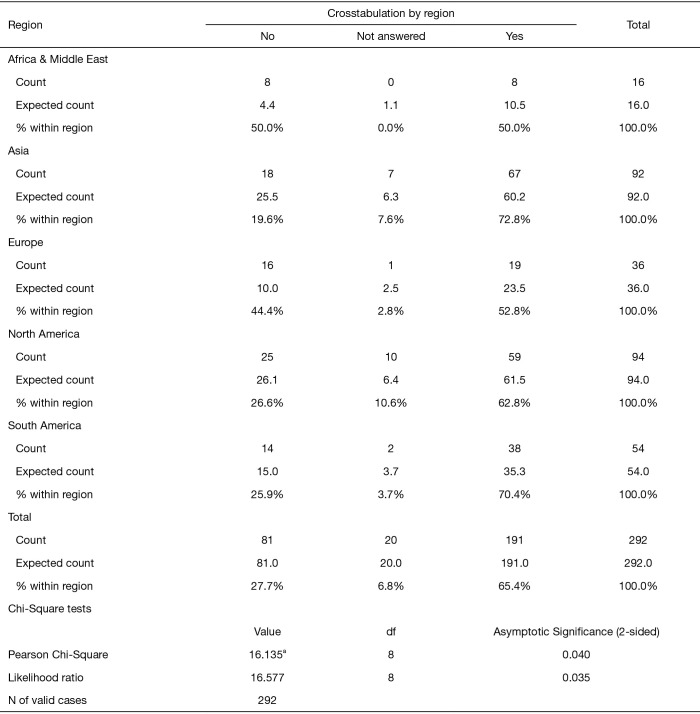

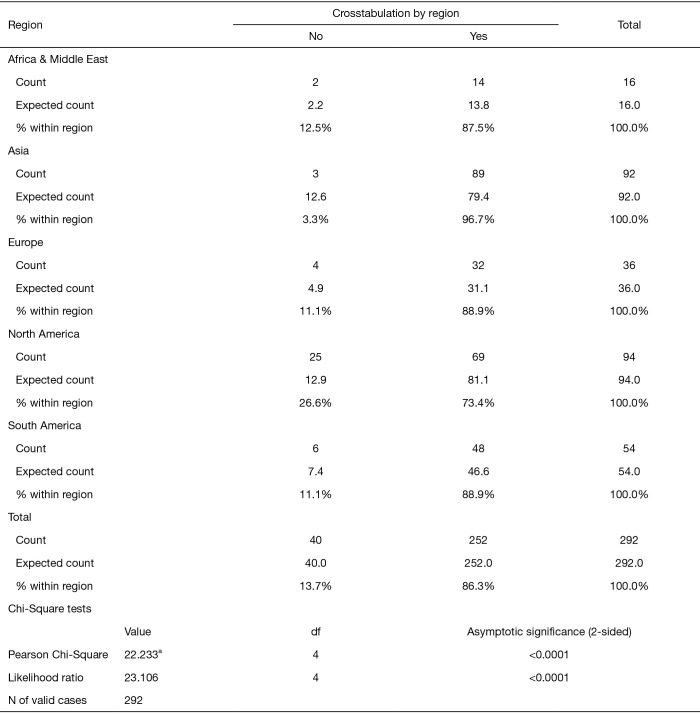

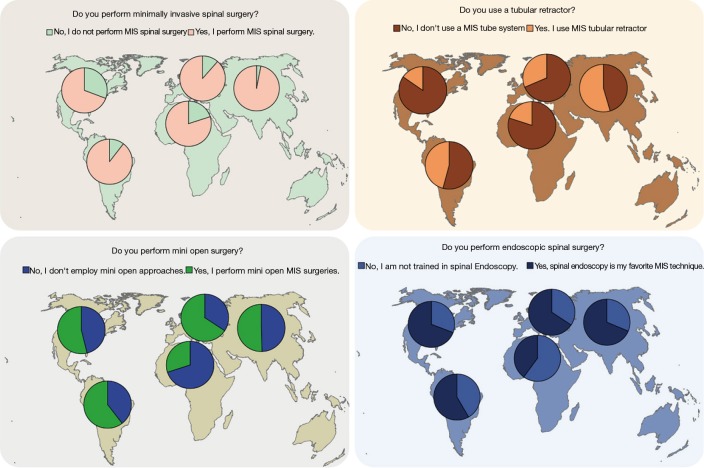

Analyzing regional differences in opinion amongst spine surgeons showed that highest percentage of surgeons in Asia (72.8%) and South America (70.2%) thought that MISST was accepted into mainstream spinal surgery in their practice setting and area (Figures 3,4; P=0.04). The acceptance numbers were lower for surgeons from North America (62.8%), and nearly equal for surgeons from Europe (52.8%) and Africa & the Middle East region (50%). The percentage of spine surgeons employing MISST was much higher per region than the rate of surgeons who thought it was mainstream in their area (Figures 5,6): Asia (96.7%), Europe (88.9%), South America (88.9%), and Africa & Middle East (87.5%). Surgeons in North America reported the lowest MISST employment in their practice globally (P<0.000).

Figure 3.

Do you think minimally invasive spinal surgery is considered mainstream in your area and practice setting? a, 4 cells (26.7%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is 1.10.

Figure 4.

Pie charts on map distribution of regional variations on MISST acceptance showing statistically significant differences (P=0.04) with surgeons in Asia (72.8%) and South America (70.2%) showing the highest percentage, followed by surgeons from North America (62.8%), and nearly equal for numbers of surgeons from Europe (52.8%) and Africa & the Middle East region (50%). MISST, minimally invasive spinal surgery techniques.

Figure 5.

Do you perform minimally invasive spinal surgery? a, 2 cells (20.0%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is 2.19.

Figure 6.

Pie charts on map distribution of regional variations on the percentage of surgeons performing MISST (top left panel). The percentage of MISST spine surgeons employing it was much higher per region at a statistically significant level (P<0.000) than the rate of surgeons who thought it was mainstream in their area: Asia (96.7%), Europe (88.9%), South America (88.9%), and Africa & Middle East (87.5%; P<0.000). Usage of the tubular retractor (top right panel) was the least commonly employed MISST (41.8%). Mini-open approaches (left bottom panel) were the second most widely applied MISST (55.1%), and endoscopic surgery (right bottom panel) is currently reported as the most commonly employed MISST globally. MISST, minimally invasive spinal surgery techniques.

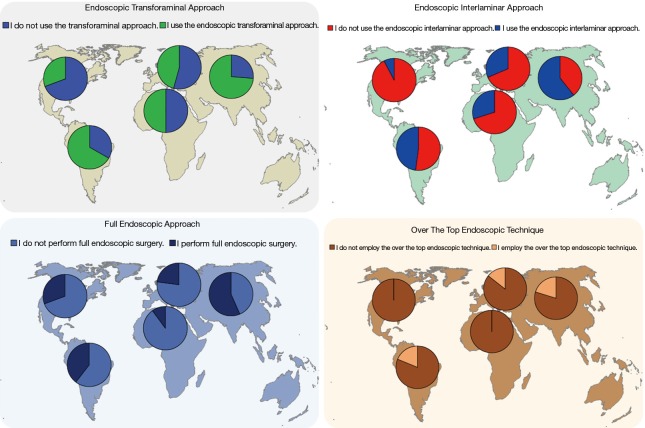

Multiple choice questioning (Table 3) revealed that spinal endoscopy (59.9%) is currently the most commonly employed MISST globally (Figure 6) followed by mini-open approaches (55.1%), and tubular retractor systems (41.8%). The most preferred approach (Table 4; Figure 7) when employing endoscopic MISST was reported to be the transforaminal approach (56.2%) followed by interlaminar approach (41.8%), full endoscopic (35.3%), and over the top MISST (13.7%). Various preferred combinations of endoscopic MISSTs were reported and are listed in Table 5. Further crosstabulation by region showed that full endoscopic combination approaches were reported to be performed most frequently by surgeons in Asia (63.1%), and South America (41%), and Europe (30.6%). Surgeons from Africa & Middle East (25.1%) and North America (16%) reported to the lowest employment of combination endoscopic MISST approaches (P<0.000).

Table 3. Frequency table of minimally invasive surgery techniques used by spine surgeon respondents.

| Type of MISST | Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tubular retractor system | ||||

| No, I don’t use a MIS tube system | 170 | 58.2 | 58.2 | 58.2 |

| Yes, I use MIS tubular retractor | 122 | 41.8 | 41.8 | 100.0 |

| Total | 292 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Mini open surgery | ||||

| No, I don't employ mini open approaches | 131 | 44.9 | 44.9 | 44.9 |

| Yes, I perform mini open MIS surgeries | 161 | 55.1 | 55.1 | 100.0 |

| Total | 292 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Endoscopic surgery | ||||

| No, I am not trained in spinal endoscopy | 117 | 40.1 | 40.1 | 40.1 |

| Yes, spinal endoscopy is my favorite MIS technique | 175 | 59.9 | 59.9 | 100.0 |

| Total | 292 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

MISST, minimally invasive spinal surgery techniques.

Table 4. Frequency table of endoscopic techniques employed by responding spine surgeons.

| Type of endoscopic technique | Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transforaminal | ||||

| Missing response | 128 | 43.8 | 43.8 | 43.8 |

| Transforaminal | 164 | 56.2 | 56.2 | 100.0 |

| Total | 292 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Interlaminar | ||||

| Missing response | 170 | 58.2 | 58.2 | 58.2 |

| Interlaminar | 122 | 41.8 | 41.8 | 100.0 |

| Total | 292 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Full endoscopic | ||||

| Missing response | 189 | 64.7 | 64.7 | 64.7 |

| Full endoscopic | 103 | 35.3 | 35.3 | 100.0 |

| Total | 292 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Over the top | ||||

| Missing response | 252 | 86.3 | 86.3 | 86.3 |

| Over the top | 40 | 13.7 | 13.7 | 100.0 |

| Total | 292 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

Figure 7.

Pie charts on map distribution of regional variations on percentage of surgeons performing various endoscopic approaches: top left panel—transforaminal approach (56.2%), top right panel—interlaminar approach (41.8%), left bottom panel—full endoscopic (35.3%), and bottom right panel—over the top endoscope (13.7%). Regional variations analysis showed transforaminal over interlaminar approach being preferred in North America. In contracts, the interlaminar approach being preferred in Asia, and equally being utilized in South America with the transforaminal approach.

Table 5. Number of spine surgeons performing combination endoscopic approaches.

| Type of combination approaches | Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using single endoscopic technique or not performing spinal endoscopy | 182 | 62.3 | 62.3 | 62.3 |

| All 4 techniques | 23 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 70.2 |

| Full endoscopic & over the top | 2 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 70.9 |

| Interlaminar & full endoscopic | 5 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 72.6 |

| Interlaminar & full endoscopic & over the top | 2 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 73.3 |

| Interlaminar & over the top | 4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 74.7 |

| Transforaminal & full endoscopic | 7 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 77.1 |

| Transforaminal & interlaminar | 25 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 85.6 |

| Transforaminal & interlaminar & full endoscopic | 39 | 13.4 | 13.4 | 99.0 |

| Transforaminal & interlaminar & over the top | 2 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 99.7 |

| Transforaminal & over the top | 1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 100.0 |

| Total | 292 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Discussion

Findings of this opinion survey of spine surgeons around the world confirmed the authors’ stipulation that significant regional variations in local acceptance of MISST into mainstream spinal surgery were reported by the 292 respondents who completed and submitted the online questionnaire. Responses were blinded and the investigators of this study had no way of researching causes for these regional variations in the preferred utilization of MISST. Linear regression monitoring of the change in response rates to the four clinical questions over the three-week period and kappa analysis of agreement in the 292 survey submissions showed a relatively stable distribution of asymmetric variances suggesting that similar percentage response rates could have been reasonably expected with a broader global polling sample. Understanding the incoming data in real time was essential to the authors since surgeons from some countries (Mexico, China, and Brazil) were somewhat overrepresented in the survey making up for 55.2% of all respondents. Besides, the effect size of agreements or disagreements was not known when launching the survey. Hence, it was unclear at the outset of the online data acquisition when sufficient statistical sample size would have been achieved to close the survey. As corroborated by the low P values calculated for most Chi-square crosstabulations to be significantly less than 0.05 using the 95% confidence interval, the authors of this study are confident that results presented herein are in fact representative of current opinions regarding MISST amongst spine surgeon the world over.

To our surprise, this team of authors learned that the percentage of surgeons performing MISST was consistently higher throughout the five regions than that of surgeons who thought that MISSTs has become accepted locally into mainstream spinal surgery (Figures 3,4). The acceptance-to-performance lag gap was the highest for surgeons reporting from Africa & Middle East (37.50%), followed by surgeons responding from Europe (36.10%) and Asia (23.90%), and South America (18.50%). Surgeons from North America reported the smallest gap between perceived public perception of MISST acceptance by their peers into mainstream spinal surgery and the percentage of surgeons employing MISST (10.6%). Reasons for these regional variations in universally lower MISST acceptance and higher performance rates could be multiple. Future studies could focus on investigating the impact of formalized surgeon training programs, support by national and international societies by endorsing MISSTs in their formal clinical treatment guidelines, local regulations and laws, the local medical payer infrastructure, cultural factors, and conceivably many others. This survey provides no further inside, and any additional conclusions other than the ones provided would be unsubstantiated. However, it seems clear that there is a “silent majority” amongst the spine surgeons polled that employ MISST in spite of lower public perception of acceptability voiced by their local peers.

Another unexpected finding of this study was the high preference for spinal endoscopy reported by participating spine surgeons. From the contemporary MISST literature, the authors of this study would have expected that tubular retractor systems would have been reported as the most preferred MISST (63-69). While the lag of the published literature behind new trends in spine surgery is not surprising in itself, this survey does suggest though that a paradigm shift in the integration of various MISST into day-to-day spine surgery practice is taking place. With the early advances in MISST focusing on lowering the burden associated with open lumbar spinal surgery by merely limiting the size of the incision (mini-open approach) (70-72), or minimizing the tissue disruption (tubular retractor) (68,69), spinal endoscopy seems to be embraced by a much larger percentage of spine surgeons—particularly by younger surgeons between the ages of 34 and 45—than this team of authors expected as this conceptually different type of platform for surgery in the lumbar spine has not been fully embraced by the prominent national and international societies and has only found support in smaller spine surgery subspecialty organization.

A higher level of complexity of endoscopic spine surgery was reported by spine surgeons between the ages of 34 and 45 and residing in Asia and South America. The most common of reported endoscopic combination approaches were transforaminal, interlaminar and full endoscopic techniques. A significant percentage of the same group of surgeons also reported the use of the over-the-top technique. Possible explanations for the higher use of more complex lumbar spinal endoscopic surgery techniques requiring a higher level of training and skill are better-formalized training programs, clinical treatment guidelines of professional societies and the impact of well-published and charismatic opinion leaders in South America and Asia.

Conclusions

This online survey reached 586 spine surgeons around the world in just three weeks suggesting that making a questionnaire accessible on a hand-held device facilitates data acquisition. Crosstabulation analysis of the 292 completed and submitted surveys revealed significant variations in reported regional consensus of surgeons and their acceptance rates of MISST in the area of their practice setting. In contrast, the rate of employment of MISST in day-to-day clinical practice reported by spine surgeons was universally higher than the perceived acceptance rates of MISST into mainstream by their peers in their practice area. The survey suggest that endoscopic spinal surgery is now the most commonly performed MISST. More complex endoscopic spinal surgeries requiring high level training and skill are predominantly performed in South America and Asia.

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this editorial represent those of the authors and no other entity or organization.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Jorge Felipe Ramírez León is shareholder & President of Board of Directors Ortomac, Colombia, consultant Elliquence, USA. The senior author designed and trademarked his inside-out YESS™ technique and receives royalties from the sale of his inventions. Indirect conflicts of interest (honoraria, consultancies to sponsoring organizations are donated to IITS.org, a 501c 3 organization).

References

- 1.Hartman C, Hemphill C, Godzik J, et al. Analysis of cost and 30 day outcomes in single level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) and less invasive, standalone lateral transpsoas interbody fusion (LIF). World Neurosurg 2019;122:e1037-40. 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.10.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youn MS, Shin JK, Goh TS, et al. Endoscopic posterior decompression under local anesthesia for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. J Neurosurg Spine 2018;29:661-6. 10.3171/2018.5.SPINE171337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryu DS, Ahn SS, Kim KH, et al. Does minimally invasive fusion technique influence surgical outcomes in isthmic spondylolisthesis? Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 2019;28:33-40. 10.1080/13645706.2018.1457542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godzik J, Walker CT, Theodore N, et al. Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Interbody Fusion With Robotically Assisted Bilateral Pedicle Screw Fixation: 2-Dimensional Operative Video. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2019;16:E86-7. 10.1093/ons/opy288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minamide A, Simpson AK, Okada M, et al. Microendoscopic Decompression for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis With Degenerative Spondylolisthesis: The Influence of Spondylolisthesis Stage (Disc Height and Static and Dynamic Translation) on Clinical Outcomes. Clin Spine Surg 2019;32:E20-6. 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elmekaty M, Kotani Y, Mehy EE, et al. Clinical and Radiological Comparison between Three Different Minimally InvasiveSurgical Fusion Techniques for Single-Level Lumbar Isthmic and Degenerative Spondylolisthesis: Minimally Invasive Surgical Posterolateral Fusion versus Minimally Invasive Surgical Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion versus Midline Lumbar Fusion. Asian Spine J 2018;12:870-9. 10.31616/asj.2018.12.5.870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mueller K, Zhao D, Johnson O, et al. The Difference in Surgical Site Infection Rates Between Open and Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery for Degenerative Lumbar Pathology: A Retrospective Single Center Experience of 1442 Cases. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2019;16:750-5. 10.1093/ons/opy221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park P, Fu KM, Mummaneni PV, et al. International Spine Study Group The impact of age on surgical goals for spinopelvic alignment in minimally invasive surgery for adult spinal deformity. J Neurosurg Spine 2018;29:560-4. 10.3171/2018.4.SPINE171153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menger R, Hefner MI, Savardekar AR, et al. Minimally invasive spine surgery in the pediatric and adolescent population: A case series. Surg Neurol Int 2018;9:116. 10.4103/sni.sni_417_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khechen B, Haws BE, Patel DV, et al. Comparison of Postoperative Outcomes between Primary MIS TLIF and MIS TLIF as a Revision Procedure to Primary Decompression. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komatsu J, Muta T, Nagura N, et al. Tubular surgery with the assistance of endoscopic surgery via a paramedian or midline approach for lumbar spinal canal stenosis at the L4/5 level. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2018;26:2309499018782546. 10.1177/2309499018782546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fanous AA, Liounakos JI, Wang MY. Minimally Invasive Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2018;29:461-6. 10.1016/j.nec.2018.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anand N, Kong C. Can Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion Create Lordosis from a Posterior Approach? Neurosurg Clin N Am 2018;29:453-9. 10.1016/j.nec.2018.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choy W, Miller CA, Chan AK, et al. Evolution of the Minimally Invasive Spinal Deformity Surgery Algorithm: An Evidence-Based Approach to Surgical Strategies for Deformity Correction. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2018;29:399-406. 10.1016/j.nec.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maugeri R, Basile L, Gulì C, et al. Percutaneous Pedicle-Lengthening Osteotomy in Minimal Invasive Spinal Surgery to Treat Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A Single-Center Preliminary Experience. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg 2018;79:365-71. 10.1055/s-0038-1641148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulkarni AG, Kantharajanna SB, Dhruv AN. The Use of Tubular Retractors for Translaminar Discectomy for Cranially and Caudally Extruded Discs. Indian J Orthop 2018;52:328-33. 10.4103/ortho.IJOrtho_364_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamburrelli FC, Meluzio MC, Burrofato A, et al. Minimally invasive surgery procedure in isthmic spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J 2018;27:237-43. 10.1007/s00586-018-5627-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park Y, Seok SO, Lee SB, Ha JW. Minimally Invasive Lumbar Spinal Fusion Is More Effective Than Open Fusion: A Meta-Analysis. Yonsei Med J 2018;59:524-38. 10.3349/ymj.2018.59.4.524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verla T, Winnegan L, Mayer R, et al. Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Versus Direct Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion: Effect on Return to Work, Narcotic Use, and Quality of life. World Neurosurg 2018;116:e321-8. 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pimenta L, Tohmeh A, Jones D, et al. Rational decision making in a wide scenario of different minimally invasive lumbar interbody fusion approaches and devices. J Spine Surg 2018;4:142-55. 10.21037/jss.2018.03.09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kono Y, Gen H, Sakuma Y, et al. Comparison of Clinical and Radiologic Results of Mini-Open Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion and Extreme Lateral Interbody Fusion Indirect Decompression for Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis. Asian Spine J 2018;12:356-64. 10.4184/asj.2018.12.2.356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mancuso CA, Duculan R, Cammisa FP, et al. Fulfillment of patients' expectations of lumbar and cervical spine surgery. Spine J 2016;16:1167-74. 10.1016/j.spinee.2016.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mancuso CA, Duculan R, Cammisa FP, et al. Proportion of Expectations Fulfilled: A New Method to Report Patient-centered Outcomes of Spine Surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:963-70. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabibian BE, Kuhn EN, Davis MC, et al. Patient Expectations and Preferences in the Spinal Surgery Clinic. World Neurosurg 2017;106:595-601. 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stambough JL. Matching patient and physician expectations in spine surgery leads to improved outcomes. Spine J 2001;1:234. 10.1016/S1529-9430(01)00088-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehrotra A, Sloss EM, Hussey PS, et al. Evaluation of a center of excellence program for spine surgery. Med Care 2013;51:748-57. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829b091d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karami KJ, Buckenmeyer LE, Kiapour AM, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of the pedicle screw insertion depth effect on screw stability under cyclic loading and subsequent pullout. J Spinal Disord Tech 2015;28:E133-9. 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McClelland S, 3rd, Goldstein JA. Minimally Invasive versus Open Spine Surgery: What Does the Best Evidence Tell Us? J Neurosci Rural Pract 2017;8:194-8. 10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_472_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein CL, Macwan K, Sundararajan K, et al. Perioperative outcomes and adverse events of minimally invasive versus open posterior lumbar fusion: meta-analysis and systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine 2016;24:416-27. 10.3171/2015.2.SPINE14973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldstein CL, Macwan K, Sundararajan K, et al. Comparative outcomes of minimally invasive surgery for posterior lumbar fusion: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:1727-37. 10.1007/s11999-014-3465-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zahrawi F. Microlumbar discectomy. Is it safe as an outpatient procedure? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:1070-4. 10.1097/00007632-199405000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bookwalter JW, 3rd, Busch MD, Nicely D. Ambulatory surgery is safe and effective in radicular disc disease. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:526-30. 10.1097/00007632-199403000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fokter SK, Yerby SA. Patient-based outcomes for the operative treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Eur Spine J 2006;15:1661-9. 10.1007/s00586-005-0033-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeung AT, Gore SR. In-vivo Endoscopic Visualization of Patho-anatomy in Symptomatic Degenerative Conditions of the Lumbar Spine II: Intradiscal, Foraminal, and Central Canal Decompression. Surg Technol Int 2011;21:299-319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeung AT, Yeung CA. In-vivo endoscopic visualization of patho-anatomy in painful degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine. Surg Technol Int 2006;15:243-56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeung AT. The Evolution and Advancement of Endoscopic Foraminal Surgery: One Surgeon's Experience Incorporating Adjunctive Techologies. SAS J 2007;1:108-17. 10.1016/S1935-9810(07)70055-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeung A, Roberts A, Zhu L, et al. Treatment of Soft Tissue and Bony Spinal Stenosis by a Visualized Endoscopic Transforaminal Technique Under Local Anesthesia. Neurospine 2019;16:52-62. 10.14245/ns.1938038.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gollogly S, Yeung AT. Endoscopic Spine Surgery: Navigating the Learning Curve. J Spine 2018;S7:010.

- 39.Yeung AT, Roberts A, Shin P, et al. Suggestions for a Practical and Progressive Approach to Endoscopic Spine Surgery Training and Privileges. J Spine 2018;7:414 10.4172/2165-7939.1000414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeung AT. Lessons Learned from 27 Years’ Experience and Focus Operating on Symptomatic Conditions of the Spine under Local Anesthesia: The Role and Future of Endoscopic Spine Surgery as a “Disruptive Technique” for Evidenced Based Medicine. J Spine 2018;7:413 10.4172/2165-7939.1000413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeung AT. Robotics in the MIS Spine Surgery Arena: A New Role to Advance the Adoption of Endoscopic Surgery as the Least Invasive Spine Surgery Procedure. J Spine 2017;6:374 10.4172/2165-7939.1000374 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeung AT. Delivery of Spine Care Under Health Care Reform in the United States. J Spine 2017;6:372 10.4172/2165-7939.1000372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeung AT. Moving Away from Fusion by Treating the Pain Generator: The Secrets of an Endoscopic Master. J Spine 2015;4:e121 10.4172/2165-7939.1000e121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yeung AT. The evolution of percutaneous spinal endoscopy and discectomy: state of the art. Mt Sinai J Med 2000;67:327-32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeung A, Kotheeranurak V. Transforaminal Endoscopic Decompression of the Lumbar Spine for Stable Isthmic Spondylolisthesis as the Least Invasive Surgical Treatment Using the YESS Surgery Technique. Int J Spine Surg 2018;12:408-14. 10.14444/5048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeung AT. In-vivo Endoscopic Visualization of Pain Generators in the Lumbar Spine. J Spine 2017;6:385 10.4172/2165-7939.1000385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yeung AT, Yeung CA, Salari N, et al. Lessons Learned Using Local Anesthesia for Minimally Invasive Endoscopic Spine Surgery. J Spine 2017;6:377 10.4172/2165-7939.1000377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeung A, Yeung CA. Endoscopic Identification and Treating the Pain Generators in the Lumbar Spine that Escape Detection by Traditional Imaging Studies. J Spine 2017;6:369. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yeung AT. Transforaminal Endoscopic Decompression for Painful Degenerative Conditions of The Lumbar Spine: A review of One Surgeon’s Experience with Over 10,000 Cases Since 1991. J Spine Neurosurg 2017;6:3. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yeung AT. Intradiscal Therapy and Transforaminal Endoscopic Decompression: Opportunities and Challenges for the Future. J Neurol Disord 2016;4:303 10.4172/2329-6895.1000303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Asch HL, Lewis PJ, Moreland DB, et al. Prospective multiple outcomes study of outpatient lumbar microdiscectomy: should 75 to 80% success rates be the norm? J Neurosurg 2002;96:34-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hersht M, Massicotte EM, Bernstein M. Patient satisfaction with outpatient lumbar microsurgical discectomy: a qualitative study. Can J Surg 2007;50:445-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pendharkar AV, Shahin MN, Ho AL, et al. Outpatient spine surgery: defining the outcomes, value, and barriers to implementation. Neurosurg Focus 2018;44:E11. 10.3171/2018.2.FOCUS17790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su AW, Habermann EB, Thomsen KM, et al. Risk Factors for 30-Day Unplanned Readmission and Major Perioperative Complications After Spine Fusion Surgery in Adults: A Review of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:1523-34. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim BD, Smith TR, Lim S, et al. Predictors of unplanned readmission in patients undergoing lumbar decompression: multi-institutional analysis of 7016 patients. J Neurosurg Spine 2014;20:606-16. 10.3171/2014.3.SPINE13699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Modhia U, Takemoto S, Braid-Forbes MJ, et al. Readmission rates after decompression surgery in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis among Medicare beneficiaries. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:591-6. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31828628f5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kocher KE, Nallamothu BK, Birkmeyer JD, et al. Emergency department visits after surgery are common for Medicare patients, suggesting opportunities to improve care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1600-7. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zolot J. A Worsening Opioid Epidemic Prompts Action. Am J Nurs 2017;117:15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheatle MD. Facing the challenge of pain management and opioid misuse, abuse and opioid-related fatalities. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2016;9:751-4. 10.1586/17512433.2016.1160776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hupp JR. The Surgeon’s Roles in Stemming the Prescription Opioid Abuse Epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;74:1291-3. 10.1016/j.joms.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kee JR, Smith RG, Barnes CL. Recognizing and Reducing the Risk of Opioid Misuse in Orthopaedic Practice. J Surg Orthop Adv. Winter 2016;25:238-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clark AJ, Safaee MM, Khan NR, et al. Tubular microdiscectomy: techniques, complication avoidance, and review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus 2017;43:E7. 10.3171/2017.5.FOCUS17202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee DY, Jung TG, Lee SH. Single-level instrumented mini-open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in elderly patients. J Neurosurg Spine 2008;9:137-44. 10.3171/SPI/2008/9/8/137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eck JC, Hodges S, Humphreys SC. Minimally invasive lumbar spinal fusion. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2007;15:321-9. 10.5435/00124635-200706000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Holly LT, Schwender JD, Rouben DP, et al. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: indications, technique, and complications. Neurosurg Focus 2006;20:E6. 10.3171/foc.2006.20.3.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schwender JD, Holly LT, Rouben DP, et al. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF): technical feasibility and initial results. J Spinal Disord Tech 2005;18 Suppl:S1-6. 10.1097/01.bsd.0000132291.50455.d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Overdevest GM, Peul WC, Brand R, et al. Leiden-The Hague Spine Intervention Prognostic Study Group Tubular discectomy versus conventional microdiscectomy for the treatment of lumbar disc herniation: long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017;88:1008-16. 10.1136/jnnp-2016-315306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Soriano-Sánchez JA, Quillo-Olvera J, Soriano-Solis S, et al. Microscopy-assisted interspinous tubular approach for lumbar spinal stenosis. J Spine Surg 2017;3:64-70. 10.21037/jss.2017.02.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim KT, Lee SH, Suk KS, et al. The quantitative analysis of tissue injury markers after mini-open lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:712-6. 10.1097/01.brs.0000202533.05906.ea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mummaneni PV, Rodts GE., Jr The mini-open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Neurosurgery 2005;57:256-61; discussion 256-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rodríguez-Vela J, Lobo-Escolar A, Joven-Aliaga E, et al. Perioperative and short-term advantages of mini-open approach for lumbar spinal fusion. Eur Spine J 2009;18:1194-201. 10.1007/s00586-009-1010-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dhall SS, Wang MY, Mummaneni PV. Clinical and radiographic comparison of mini-open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in 42 patients with long-term follow-up. J Neurosurg Spine 2008;9:560-5. 10.3171/SPI.2008.9.08142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]