Abstract

Quinoa protein has been paid more and more attention because of its nutritional properties and beneficial effects. With the development of bioinformatics, bioactive peptide database and computer‐assisted simulation provide an efficient and time‐saving method for the theoretical estimation of potential bioactivities of protein. Therefore, the potential of quinoa protein sequences for releasing bioactive peptides was evaluated using the BIOPEP database, which revealed that quinoa protein, especially globulin, is a potential source of peptides with dipeptidyl peptidase‐IV (DPP‐IV) and angiotensin‐I‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activities. Three plant proteases, namely papain, ficin, and stem bromelain, were employed for the in silico proteolysis of quinoa protein. Furthermore, four tripeptides (MAF, NMF, HPF, and MCG) were screened as novel promising bioactive peptides by PeptideRanker. The bioactivities of selected peptides were confirmed using chemical synthesis and in vitro assay. The present work suggests that quinoa protein can serve as a good source of bioactive peptides, and in silico approach can provide theoretical assistance for investigation and production of functional peptides.

Keywords: ACE inhibitors, bioactive peptides, DPP‐IV inhibitors, in silico approach, quinoa protein

Quinoa protein, especially globulin, is a potential source of bioactive peptides. In silico analysis makes a contribution to the exploration of novel bioactive peptide.

![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there is an increasing interest in food protein‐derived peptides for their diverse physiological activities such as antioxidant, angiotensin‐I‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory, and dipeptidyl peptidase‐IV (DPP‐IV) inhibitory activities. Many studies have been focused on the use of food protein as raw materials for the production of bioactive peptides (Ghribi et al., 2015; Nongonierma, Lalmahomed, Paolella, & FitzGerald, 2017; Uraipong & Zhao, 2018; Venuste et al., 2013). Among researches that have been made, the digestion of protein is the limiting factor in the release of bioactive peptides, with the most common and effective method to be enzymatic hydrolysis. The conventional method in the discovery of novel bioactive peptides includes not only enzymolysis in vitro or in vivo, but also a complex series of subsequent steps, that is, separation, purification, and identification of peptides with given bioactivity. With the development of bioinformatics, in silico analysis has been greatly used to investigate the bioactive features of protein and peptides, which is more economical and time‐saving than conventional method. BIOPEP database, providing collection of sequences (proteins, bioactive peptides, allergenic proteins, and sensory peptides), can be used to predict biological activities about a protein sequence, and to estimate the release of bioactive peptides by proteolysis simulation using certain proteases (Minkiewicz, Dziuba, Iwaniak, Dziuba, & Darewicz, 2008). This in silico tools has been successfully applied in the investigation of bioactive peptides from different sources, including animal products, plant products, and seafood products, such as bovine meat proteins (Minkiewicz, Dziuba, & Michalska, 2011), porcine myofibrillar proteins (Kęska & Stadnik, 2016), yak milk casein (Lin et al., 2018), cereal storage proteins (Cavazos & de Mejia, 2013), oilseed proteins (Han, Maycock, Murray, & Boesch, 2019), giant grouper roe proteins (Panjaitan, Gomez, & Chang, 2018), and portuguese oyster proteins (Gomez, Peralta, Tejano, & Chang, 2019). In addition, online tool PeptideRanker has the function of predicting the potential bioactive index of peptides, and ToxinPred has been developed to predict the toxicity of peptides.

Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) is an ancient crop and has been recognized as a potent food candidate due to its exceptional nutritive value. There is now much interest in quinoa protein for its good balance of amino acids, gluten‐free property, and high digestibility (Filho et al., 2017; Graf et al., 2015). In addition to the nutritional value, quinoa protein has been documented to exert some beneficial effects as a source of bioactive peptides, like ACE inhibition (Aluko & Monu, 2003), antioxidant (Aluko & Monu, 2003; Nongonierma, Maux, Dubrulle, Barre, & FitzGerald, 2015), DPP‐IV inhibition (Nongonierma et al., 2015), antidiabetic (Vilcacundo, Martínez‐Villaluenga, & Hernández‐Ledesma, 2017), and colon cancer cell viability inhibitory effect (Vilcacundo, Miralles, Carrillo, & Hernández‐Ledesma, 2018).

However, the potential of quinoa protein to release biological peptides has not been studied systematically. The aim of the present work was to study the potential use of quinoa protein as the precursor of bioactive peptides based on in silico analysis, and to assess the potential of some enzymes to release bioactive peptides by enzymatic hydrolysis simulation. Furthermore, this in silico analysis was used for the exploration of novel bioactive peptides derived from quinoa protein.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Protein sequences and enzymes

Five sequences of quinoa seed storage proteins were selected for the in silico analysis: 2S albumin‐like (XP_021758596), 11S seed storage globulin (AAS67036), 11S globulin seed storage protein 2‐like (XP_021770184), 13S globulin seed storage protein 1‐like (XP_021752233), and 13S globulin seed storage protein 2‐like (XP_021752668). Besides, soybean proteins, glycinin (P04347), β‐conglycinin α′ (P11827), and β‐conglycinin α (P0DO16), were taken as comparison sequences to assay the potential biological activity of different proteins. All sequence information was retrieved from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Quinoa and soybean protein sequences used for in silico analysis in this study

| Source | Protein | Accession (NCBI) | Length | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quinoa | 2S albumin‐like | XP_021758596 | 142 | 2S |

| 11S seed storage globulin | AAS67036 | 480 | 11S‐1 | |

| 11S globulin seed storage protein 2‐like | XP_021770184 | 474 | 11S‐2 | |

| 13S globulin seed storage protein 1‐like | XP_021752233 | 463 | 13S‐1 | |

| 13S globulin seed storage protein 2‐like | XP_021752668 | 542 | 13S‐2 | |

| Soybean | Glycinin | P04347 | 516 | – |

| β‐conglycinin α′ | P11827 | 621 | – | |

| β‐conglycinin α | P0DO16 | 605 | – |

In this study, three plant proteases were used for in silico proteolysis: papain (EC 3.4.22.2), ficin (EC 3.4.22.3), and stem bromelain (EC 3.4.22.32). Meanwhile, pepsin (pH > 2.0, EC 3.4.23.1), trypsin (EC 3.4.21.4), and chymotrypsin (EC 3.4.21.1) were employed to evaluate the stability of the peptides against gastrointestinal digestion.

2.2. Evaluation of quinoa proteins as a precursor of bioactive peptides via the BIOPEP database

Profiles for quinoa proteins as the precursor of bioactive peptides is available in the BIOPEP (http://www.uwm.edu.pl/biochemia/index.php/pl/biopep) using the “Profiles of potential biological activity” tool, shown as the type and location of bioactive fragment in a protein sequence. Meanwhile, the frequency of the occurrence of peptides with given activity (A) in a protein was taken as the evaluation parameter and calculated based on the equation:

| (1) |

where a is the number of peptides with given activity in the protein sequence, and N is the number of amino acid residues in the protein. The total frequency of occurrence of all bioactive peptides (∑A) in the protein was also calculated.

2.3. In silico proteolysis and virtual screening

The proteolysis simulation provided by BIOPEP was adopted. Papain, ficin, and stem bromelain were independently applied to the protein sequences to release peptides. The frequency of release of peptides with given bioactivity by selected enzymes (A E) and the relative frequency of release of peptides with given activity by selected enzymes (W) were calculated according to the equations:

| (2) |

where d is the number of peptides with given activity released from the protein sequence by selected enzyme, and N is the number of amino acid residues in the protein.

| (3) |

Then, the peptides with three amino acids were submitted to PeptideRanker (http://distilldeep.ucd.ie/PeptideRanker/) for the calculation of theoretical bioactivity of peptides, and the results were presented as score values from 0 (poorest bioactivity) to 1 (best bioactivity). Peptides with relatively high PeptideRanker score and no previously described bioactivity based on the information recorded in BIOPEP database were evaluated for their stability against the gastrointestinal digestion using BIOPEP simulation, and their toxicity using ToxinPred (http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/toxinpred/multi_submit.php). The solubility of the peptide was evaluated by the online Innovagen server, available at http://www.innovagen.com/proteomics-tools.

2.4. Peptide synthesis

Screened peptides were synthesized by the Sangon Biotech Company for the evaluation of in vitro DPP‐IV and ACE inhibitory activities. The purity of the peptide was 99% verified by HPLC.

2.5. Assay of DPP‐IV inhibitory activity

The DPP‐IV inhibition assay was determined using DPP‐IV inhibitor screening assay kit (KA1311, Abnova). Briefly, peptide samples (10 μl), dispersed in assay buffer (20 mM Tris‐HCl containing 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at various concentrations, were mixed with assay buffer and DPP‐IV in a 96‐well plate. Then, substrate solution (Gly‐Pro‐Aminomethylcoumarin) was added to initiate the reactions. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and the fluorescence was measured using a plate reader (Synergy MX, Bio Tek) at an excitation wavelength of 350 nm and an emission wavelength of 450 nm. The concentration of the DPP‐IV inhibitor required to inhibit 50% of DPP‐IV activity under the above assay conditions was defined as the IC50, which was the mean value from three independent replicate assays.

2.6. Assay of ACE inhibitory activity

The ACE inhibition assay was carried out with the ACE inhibitory assay kit (ACE kit‐WST). Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a plate reader (SpectraMax plus, Molecular devices), and the IC50 value reported for each sample was the mean value from three independent replicate assays.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All tests for peptides bioactivities were conducted with three replicates, and their data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviations. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 16.0. Differences between the means were tested using one‐way ANOVA with Duncan's test. Mean values were considered significantly different at p < .01.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

3.1. The potential of quinoa seed storage protein as a precursor of bioactive peptides

Globulin and albumin were found to be dominant in quinoa seed protein (Brinegar, Sine, & Nwokocha, 1996; Prakash & Pal, 1998). To investigate the potential of quinoa protein as precursors of bioactive peptides, a total of five quinoa protein sequences with a range of 142–542 amino acids (Table 1 and Appendix S1) were selected and assessed by “Profiles of potential biological activity” of BIOPEP, and three soybean protein sequences as comparison. Soybean is an important crop in many countries for its high‐quality protein and kinds of biological activities. Glycinin and β‐conglycinin have been regarded as the good precursors of bioactive peptides (Han et al., 2019; Singha, Vij, & Hati, 2014).

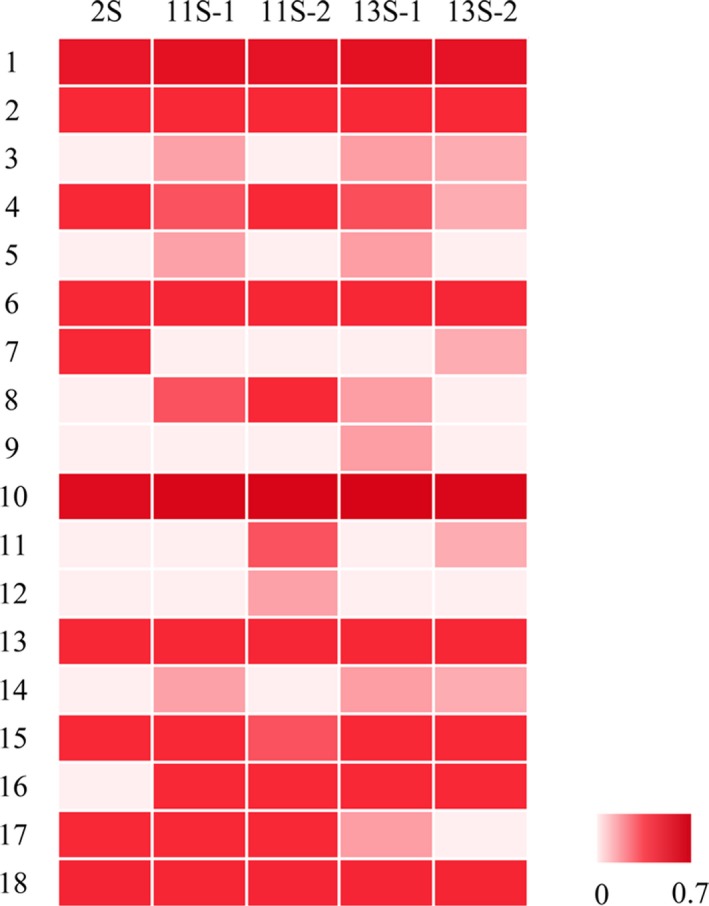

Based on the present limited information in BIOPEP database (as of 11 June 2019, 3,792 peptides functioned in 51 bioactivities have been collected in BIOPEP), fragments with 18 known biological activities were found in quinoa proteins (Figure 1). Among them, fragments with ACE inhibition, activating ubiquitin‐mediated proteolysis, antiamnestic, antioxidative, DPP‐IV inhibition, renin inhibition, inhibiting calmodulin‐dependent phosphodiesterase (CaMPDE), and stimulating glucose uptake activities existed in all analyzed quinoa protein sequences.

Figure 1.

The frequency of the occurrence of peptides with given activity in quinoa protein performed by BIOPEP. (1. ACE inhibitor; 2. Peptide activating ubiquitin‐mediated proteolysis; 3. α‐glucosidase inhibitor; 4. Antiamnestic peptide; 5. Anticancer peptide; 6. Antioxidative peptide; 7. Calcium‐binding peptide; 8. Antithrombotic peptide; 9. Bacterial permease ligand; 10. DPP‐IV inhibitor; 11. Embryotoxic; 12. Hydroxy methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitor; 13. Renin inhibitor; 14. Immunomodulating peptide; 15. CaMPDE inhibitor; 16. Neuropeptide; 17. Peptide regulating the stomach mucosal membrane activity; 18. Glucose uptake stimulating peptide.)

As for the total frequency of bioactive peptides occurrence, 11S‐2 (∑A = 1.2508) had the highest value of seven analyzed proteins, followed by 11S‐1 (∑A = 1.2480) and 13S‐1 (∑A = 1.2443). These three quinoa proteins showed higher total frequency of bioactive peptides occurrence than soybean proteins (Table 2). Quinoa albumin 2S had the weakest potential to act as precursor of bioactive peptides, with the least bioactivities and lowest occurrence frequency of bioactive peptides (∑A = 1.0139). Globulin is the principal precursor of bioactive peptides in quinoa seed.

Table 2.

The frequency of occurrence of peptides with a given activity (A) in selected protein sequences

| Source | Protein | Number of activities | ∑A | A 1 | A 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (DPP‐IV inhibitor) | (ACE inhibitor) | ||||

| Quinoa | 2S | 9 | 1.0139 | 0.5211 | 0.3451 |

| 11S‐1 | 14 | 1.2480 | 0.6354 | 0.4208 | |

| 11S‐2 | 13 | 1.2508 | 0.6540 | 0.3945 | |

| 13S‐1 | 15 | 1.2443 | 0.6609 | 0.4168 | |

| 13S‐2 | 13 | 1.2082 | 0.6181 | 0.3930 | |

| Soybean | Glycinin | 13 | 1.1628 | 0.6182 | 0.3876 |

| β‐conglycinin α′ | 15 | 1.1949 | 0.5781 | 0.3833 | |

| β‐conglycinin α | 15 | 1.2100 | 0.5752 | 0.3934 |

DPP‐IV (A (DPP‐IV inhibitor) = 0.5211–0.6609) and ACE inhibitor (A (ACE inhibitor) = 0.3451–0.4208) were the major part of bioactive fragments in all selected protein sequences and were taken as the research focus in this paper. DPP‐IV is a ubiquitous protease associated with the degradation of incretin and regulation of blood glucose levels, and drug based on the inhibition of its activity is one of the most recent treatments for type 2 diabetes mellitus (Juillerat‐Jeanneret, 2014). Food protein‐derived DPP‐IV inhibitors have been intensively studied over the last few decades (Lacroix & Li‐Chan, 2012). ACE plays a significant role in blood pressure regulation by promoting the production of the active hypertensive hormone and inactivation of vasodilator peptide, making it one of the promising physiological targets for antihypertensive drugs (Miralles, Amigo, & Recio, 2018; Udenigwe & Mohan, 2014). Various dietary proteins have been employed for the generation of ACE inhibitory hydrolysates, including animal products, marine organisms, and plants (Lee & Hur, 2017).

The highest release frequency of DPP‐IV and ACE inhibitor was found in quinoa 13S‐1 and 11S‐1, respectively. Quinoa globulin 11S‐1, 11S‐2, and 13S‐1 exerted higher release frequency for DPP‐IV and ACE inhibitory peptides than analyzed soybean proteins. Frequency parameters of 13S‐2 were slightly lower than the highest value in soybean proteins. Our study demonstrated that globulin in quinoa seed presented a high potential as a precursor for the production of various biologically active peptides, especially DPP‐IV and ACE inhibitors.

3.2. In silico proteolysis of quinoa proteins

Bioactive peptides encrypted within the natural food protein are supposed to be released by enzymolysis to exert their biological function. A number of food processing enzymes were previously used for the generation of bioactive peptides from a variety of natural sources (Fu, Wu, Zhu, & Xiao, 2016; Lin, Zhang, Han, Meng, et al., 2018). In our study, three commercial plant proteases papain, ficin, and stem bromelain were applied, respectively, to the selected quinoa protein sequences by “Enzyme(s) action” of BIOPEP (Appendix S2). Hydrolysates with the degree of hydrolysis (DH) between 31.2925% and 52.1298% were obtained by in silico proteolysis (Table 3). Among the three enzymes, stem bromelain gave the highest DHs for five quinoa proteins, while the release of bioactive peptides is not proportional to the DH of hydrolysate.

Table 3.

The parameters describing the predicted efficiency of release of bioactive fragments from quinoa protein by in silico enzymolysis

| Protein | Enzymes | DHt (%) | DPP‐IV inhibitor | ACE inhibitor | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A E | W | A E | W | |||

| 2S | Papain | 35.3741 | 0.0541 | 0.1082 | 0.0270 | 0.0833 |

| Ficin | 31.2925 | 0.0270 | 0.0540 | 0.0135 | 0.0416 | |

| Stem bromelain | 35.3741 | 0.0541 | 0.1082 | 0.0203 | 0.0626 | |

| 11S‐1 | Papain | 43.6105 | 0.0850 | 0.1386 | 0.0506 | 0.1244 |

| Ficin | 44.0162 | 0.0668 | 0.1089 | 0.0364 | 0.0895 | |

| Stem bromelain | 52.1298 | 0.0972 | 0.1585 | 0.0425 | 0.1044 | |

| 11S‐2 | Papain | 39.0593 | 0.0735 | 0.1177 | 0.0408 | 0.1087 |

| Ficin | 44.1718 | 0.0735 | 0.1177 | 0.0510 | 0.1358 | |

| Stem bromelain | 50.3067 | 0.0633 | 0.1014 | 0.0408 | 0.1087 | |

| 13S‐1 | Papain | 42.0168 | 0.1027 | 0.1622 | 0.0566 | 0.1429 |

| Ficin | 40.7563 | 0.0566 | 0.0894 | 0.0398 | 0.1005 | |

| Stem bromelain | 51.6807 | 0.0692 | 0.1093 | 0.0482 | 0.1217 | |

| 13S‐2 | Papain | 40.0359 | 0.0663 | 0.1121 | 0.0376 | 0.0999 |

| Ficin | 46.6786 | 0.0591 | 0.0999 | 0.0358 | 0.0951 | |

| Stem bromelain | 52.0646 | 0.0573 | 0.0969 | 0.0323 | 0.0858 | |

The evaluation parameters (A E and W) of DPP‐IV and ACE inhibitory peptides generated in this study were shown in Table 3. The release frequency (A E) of DPP‐IV inhibitory peptides was higher than that of ACE inhibitory peptides generated from the same sequence by the same enzyme, and the similar results were seen in the relative release frequency (W) of peptides except 11S‐2 and 13S‐1 treated by ficin and stem bromelain.

Different enzymes have different potential to release bioactive peptides from proteins, which attribute to their specific cleavage sites (Gomez et al., 2019). For example, Fu et al. (2016) performed in silico proteolysis of bovine collagen by twenty‐seven different enzymes and found that papain was the most effective protease to release ACE inhibitory peptides theoretically. In our study, papain‐treated quinoa proteins (except 11S‐1) exerted relatively higher release frequency index of DPP‐IV inhibitors than the other two enzymes. Similarly, papain has relative strong potential as an enzyme releasing ACE inhibitory peptides from quinoa proteins (except 11S‐2). This might be because papain shared most of the cutting sites with two other enzymes, except for those from the N‐terminus (Appendix S3).

The sequences of identified DPP‐IV and ACE inhibitory peptides predicted to be released from quinoa proteins by in silico enzymolysis were presented in Table 4. These bioactive peptides are made up of relatively few amino acids; exactly, most of them are dipeptides, except for IVR, IVY, AQL, VTR, and NKL. Actually, there were still plenty of peptides with no previously described bioactivity released from in silico enzymolysis of quinoa proteins. As for the bioactivity of the unknown peptides, further study is required.

Table 4.

BIOPEP analysis of bioactive peptides predicted to be released from quinoa protein based on in silico enzymolysis with papain, ficin, and stem bromelain

| DPP‐IV inhibitors | ACE inhibitors | |

|---|---|---|

| Papain | 171 a : | 96: |

| VV (1)b, SP (1), KP (1), NP (2), QP (1), HL (2), AL (11), SL (4), VR (2), PL (3), WI (1), YT (1), AD (2), AE (4), AF (5), AG (19), AH (1), AT (1), AY (1), DP (1), EG (3), EH (1), ES (1), ET (1), HR (2), HT (1), IH (1), IL (3), IR (2), KF (2), KG (1), KR (1), KT (4), MR (4), NF (1), NG (5), NL (1), NR (1), PF (1), PG (1), QD (1), QF (4), QG (17), QH (3), QI (1), QL (17), QN (1), QT (6), QV (1), QW (1), SF (4), VF (4), VL (3), VT (3), YL (3), YR (1) | IR (2), IY (1), VF (4), PR (1), YL (3), AY (1), IVR (1), PL (3), AF (5), KR (1), IF (1), AG (19), HL (2), KG (1), HG (1), QG (17), SG (6), EG (3), NG (5), PG (1), VR (2), NF (1), SF (4), KF (2), AR (3), KP (1), IE (1), AH (1), IL (3) | |

| Ficin | 132: | 83: |

| EK (1), AL (2), VR (4), PL (5), WR (1), AG (9), EG (4), EH (1), ES (6), EY (1), IH (1), IL (4), IR (3), MG (1), MK (2), MR (3), NF (1), NG (8), NH (1), NL (4), NR (1), NY (1), PF (3), PG (2), PH (1), PK (2), PS (8), QG (4), QH (2), QL (8), QS (4), QY (1), TG (1), TK (4), TL (1), TR (4), TS (4), VF (7), VG (1), VH (1), VK (1), VL (4), VS (4), VY (1) | IR (3), IY (2), VF (7), VY (1), PR (4), IVR (1), PL (5), IVY (1), VK (1), IF (2), VG (1), AG (9), MG (1), QG (4), TG (1), EG (4), NG (8), PG (2), VR (4), QK (6), NY (1), NF (1), NK (1), AR (2), EY (1), EK (1), PH (1), AQL (2), VTR (1), DY (1), IL (4) | |

| Stem bromelain | 149: | 84: |

| MA (2), KA (2), PA (2), HA (1), IA (2), WV (1), HL (2), PL (6), WR (1), YT (2), EG (4), ES (6), ET (2), EV (5), HR (3), HS (2), HT (1), HV (3), IL (5), IR (9), KF (2), KG (1), KR (2), KS (2), KT (4), MR (5), MV (1), NA (5), NF (1), NG (8), NL (3), NR (1), NV (2), PF (2), PG (3), PS (9), PT (1), QA (2), QG (6), QL (8), QS (5), QT (1), QV (2), YF (1), YL (3), YR (2), YS (2), YV (4) | IR (9), PR (4), YL (3), PL (6), IA (2), KR (2), IF (1), IG (2), HL (2), KG (1), DA (3), HG (1), QG (6), EG (4), EA (6), NG (8), PG (3), NKL (1), NF (1), KF (2), KA (2), EV (5), PT (1), YV (4), IL (5) |

The numbers in bold indicate the total number of sequences with given activity released from quinoa proteins by in silico enzymolysis.

The numbers in the parentheses indicate the repetitions of the bioactive sequences.

3.3. Virtual screening of novel bioactive peptides

Herein, tripeptides released from in silico enzymolysis of quinoa proteins were further analyzed for the discovery of novel bioactive peptides with specific effect. Analysis of PeptideRanker predicted the theoretical bioactivity of peptides with the score values from 0.0222 to 0.9816 (Appendix S4). The top five peptides with high score were WCY, MAF, NMF, HPF, and MCG. Among them, WCY has been found in oat protein as an ACE inhibitory peptide (Bleakley, Hayes, O’ Shea, Gallagher, & Lafarga, 2017). However, the other four peptides, with no previously described bioactivity based on BIOPEP database and literatures, were subjected to in silico prediction of toxicity, solubility, and stability against the gastrointestinal digestion.

As shown in Table 5, the prediction has been given that all the selected peptides are nontoxic, and expected to be poorly soluble in water due to their high hydrophobic residues. To exert physiology effect, it is necessary that peptides survive gastrointestinal digestion. However, these four peptides exerted undesired low stability in simulative gastrointestinal digestion. As Udenigwe and Fogliano (2017) reported, encapsulation techniques need to be developed in the preparation of bioactive peptides in order to protect peptides from undesired degradation. It is also notable that two peptides were partly hydrolyzed, accompanying with the new generation of dipeptides PF and CG. PF is a DPP‐IV inhibitor documented in BIOPEP database, and CG has high theoretical bioactivity (0.9319) predicted by PeptideRanker. It indicated that these peptides could act as not only bioactive substance but also promising precursor.

Table 5.

Predicted results of PeptideRanker score, toxicity, solubility, and stability against the gastrointestinal digestion of selected peptides

| Peptide | Protein | Location | PeptideRanker score | Toxicity | Solubility | Simulated Digestion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAF | 13S‐1 | f (1–3) | 0.9676 | Non‐Toxin | Poor | M‐A‐F |

| NMF | 11S‐2 | f (342–344) | 0.9624 | Non‐Toxin | Poor | N‐M‐F |

| HPF | 11S‐2 | f (97–99) | 0.9502 | Non‐Toxin | Poor | H‐PF |

| MCG | 2S | f (128–130) | 0.9502 | Non‐Toxin | Poor | M‐CG |

3.4. In vitro assessment of biological activity

In order to verify the bioactive effect of selected peptides, four chemically synthesized peptides were subjected to in vitro assessment of DPP‐IV and ACE inhibition activity. The assay results showed that all the peptides exhibited the positive ability in inhibiting DPP‐IV and ACE activity (Table 6). HPF exerted strongest DPP‐IV inhibition activity with IC50 value of 13.69 μg/ml, followed by MCG (45.95 μg/ml). MCG was the most potent ACE inhibitor with IC50 value of 6.48 μg/ml, followed by HPF (40.08 μg/ml). The inhibitory activity on DPP‐IV and ACE of MAF and NMF was comparatively lower despite the higher PeptideRanker score, which indicated that they may play a role in other biological functions.

Table 6.

IC50 values (μg/ml) of chemically synthesized peptides in DPP‐IV and ACE inhibitory activities

| Peptide | DPP‐IV inhibition | ACE inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| MAF | 124.35 ± 1.75a | 55.93 ± 1.09b |

| NMF | 52.26 ± 0.83b | 62.34 ± 1.21a |

| HPF | 13.69 ± 0.76d | 40.08 ± 0.59c |

| MCG | 45.95 ± 0.91c | 6.48 ± 0.12d |

Mean values followed by different letters in a column are significantly different (p < .01).

Nongonierma et al. (2015) reported that quinoa protein hydrolysate produced by papain has in vitro DPP‐IV inhibitory effect, while the peptide sequences have not been identified. Peptide IQAEGGLT, released from quinoa protein by pepsin‐pancreatin sequential digestion, has been reported to exert DPP‐IV inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 267.81 μM (Vilcacundo et al., 2017). Compared with the bioactive peptides released by in silico proteolysis in this study, it is confirmed that the outcomes of in silico proteolysis and experimental enzymolysis were not an exact match (Nongonierma & FitzGerald, 2017; Tu, Cheng, Lu, & Du, 2018). In silico approach provides an alternative strategy for the investigation of novel bioactive peptides, but also has its limitations. Previous results showed that the products of enzymatic hydrolysis changed with the degree of hydrolysis, which was affected by kinds of factors, such as protein structural features, enzymatic activity, temperature, pH, hydrolysis time, and enzyme–substrate ratios (Fu et al., 2016; Han et al., 2019; Tu et al., 2018). However, the enzymolysis by in silico tools was rather idealistic, the digestion happened in every specific cutting site of enzymes, and it was carried out completely. Besides, in silico analysis was based on the current knowledge in BIOPEP database. The database is constantly updated, and the analysis results might be changed with new data.

4. CONCLUSION

Based on the selected protein sequences, our study revealed that the quinoa proteins contain various biological active peptides, especially DPP‐IV and ACE inhibitors. In silico proteolysis showed that papain has relative strong potential as an enzyme releasing DPP‐IV and ACE inhibitory peptides, although it exerts lower DH than stem bromelain. Furthermore, four novel bioactive tripeptides were selected by virtual screening and their bioactivities were confirmed using chemical synthesis and in vitro assay. In spite of some limitations in this in silico analysis, there is enough evidence to conclude that the quinoa protein is a promising precursor for production of bioactive peptides, and in silico proteolysis may serve the productive practice of the preparation of bioactive peptides.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

There was no human or animal testing in this study.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Hebei Provincial Key Research and Development Plan (Introduction and Quality Evaluation of Quinoa Germplasm, 19227527D‐01), the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (Minor Grain Nutrition and Function) of CAAS, and the International Science and Technology Cooperation Programme of China (KY20142023).

Guo H, Richel A, Hao Y, et al. Novel dipeptidyl peptidase‐IV and angiotensin‐I‐converting enzyme inhibitory peptides released from quinoa protein by in silico proteolysis. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8:1415–1422. 10.1002/fsn3.1423

Contributor Information

Xiushi Yang, Email: yangxiushi@caas.cn.

Guixing Ren, Email: renguixing@caas.cn.

REFERENCES

- Aluko, R. E. , & Monu, E. (2003). Functional and bioactive properties of quinoa seed protein hydrolysates. Journal of Food Science, 68(4), 1254–1258. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb09635.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley, S. , Hayes, M. , O’ Shea, N. , Gallagher, E. , & Lafarga, T. (2017). Predicted release and analysis of novel ACE‐I, renin, and DPP‐IV inhibitory peptides from common oat (Avena sativa) protein hydrolysates using in silico analysis. Foods, 6(12), 108 10.3390/foods6120108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinegar, C. , Sine, B. , & Nwokocha, L. (1996). High‐cysteine 2S seed storage proteins from quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 44(7), 1621–1623. 10.1021/jf950830+ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos, A. , & de Mejia, E. G. (2013). Identification of bioactive peptides from cereal storage proteins and their potential role in prevention of chronic diseases. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 12(4), 364–380. 10.1111/1541-4337.12017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filho, A. M. M. , Pirozi, M. R. , Borges, J. T. D. S. , Pinheiro Sant'Ana, H. M. , Chaves, J. B. P. , & Coimbra, J. S. D. R. (2017). Quinoa: Nutritional, functional, and antinutritional aspects. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 57, 1618–1630. 10.1080/10408398.2014.1001811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y. , Wu, W. , Zhu, M. P. , & Xiao, Z. G. (2016). In silico assessment of the potential of patatin as a precursor of bioactive peptides. Journal of Food Biochemistry, 40, 366–370. 10.1111/jfbc.12213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y. , Young, J. F. , Lokke, M. M. , Lametsch, R. , Aluko, R. E. , & Therkildsen, M. (2016). Revalorisation of bovine collagen as a potential precursor of angiotensin I‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides based on in silico and in vitro protein digestions. Journal of Functional Foods, 24, 196–206. 10.1016/j.jff.2016.03.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghribi, A. M. , Sila, A. , Przybylski, R. , Nedjar‐Arroume, N. , Makhlouf, I. , Blecker, C. , … Besbes, S. (2015). Purification and identification of novel antioxidant peptides from enzymatic hydrolysate of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) protein concentrate. Journal of Functional Foods, 12, 516–525. 10.1016/j.jff.2014.12.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, H. L. R. , Peralta, J. P. , Tejano, L. A. , & Chang, Y. W. (2019). In silico and in vitro assessment of portuguese oyster (Crassostrea angulata) proteins as precursor of bioactive peptides. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20, 5191 10.3390/ijms20205191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf, B. L. , Rojas‐Silva, P. , Rojo, L. E. , Delatorre‐Herrera, J. , Baldeón, M. E. , & Raskin, I. (2015). Innovations in health value and functional food development of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 14(4), 431–445. 10.1111/1541-4337.12135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, R. X. , Maycock, J. , Murray, B. S. , & Boesch, C. (2019). Identification of angiotensin converting enzyme and dipeptidyl peptidase‐IV inhibitory peptides derived from oilseed proteins using two integrated bioinformatic approaches. Food Research International, 115, 283–291. 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juillerat‐Jeanneret, L. (2014). Dipeptidyl peptidase IV and its inhibitors: Therapeutics for Type 2 diabetes and what else? Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 57(6), 2197–2212. 10.1021/jm400658e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kęska, P. , & Stadnik, J. (2016). Porcine myofibrillar proteins as potential precursors of bioactive peptides – An in silico study. Food and Function, 7, 2878–2885. 10.1039/C5FO01631B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, I. M. E. , & Li‐Chan, E. C. Y. (2012). Evaluation of the potential of dietary proteins as precursors of dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP) ‐ IV inhibitors by an in silico approach. Journal of Functional Foods, 4(2), 403–422. 10.1016/j.jff.2012.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. Y. , & Hur, S. J. (2017). Antihypertensive peptides from animal products, marine organisms, and plants. Food Chemistry, 228, 506–517. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K. , Zhang, L. W. , Han, X. , Meng, Z. X. , Zhang, J. M. , Wu, Y. F. , & Cheng, D. Y. (2018). Quantitative structure‐activity relationship modeling coupled with molecular docking analysis in screening of angiotensin I‐converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from Qula casein hydrolysates obtained by two‐enzyme combination hydrolysis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 66, 3221–3228. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K. , Zhang, L. W. , Han, X. , Xin, L. , Meng, Z. X. , Gong, P. M. , & Cheng, D. Y. (2018). Yak milk casein as potential precursor of angiotensin I‐converting enzyme inhibitory peptides based on in silico proteolysis. Food Chemistry, 254, 340–347. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.02.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkiewicz, P. , Dziuba, J. , Iwaniak, A. , Dziuba, M. , & Darewicz, M. (2008). BIOPEP database and other programs for processing bioactive peptide sequences. Journal of AOAC International, 91, 965–980. 10.1134/S1061934808070216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkiewicz, P. , Dziuba, J. , & Michalska, J. (2011). Bovine meat proteins as potential precursors of biologically active peptides – A computational study based on the BIOPEP database. Food Science and Technology International, 17(1), 39–45. 10.1177/1082013210368461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miralles, B. , Amigo, L. , & Recio, I. (2018). Critical review and perspectives on food derived antihypertensive peptides. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 66, 9384–9390. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nongonierma, A. B. , & FitzGerald, R. J. (2017). Strategies for the discovery and identification of food protein‐derived biologically active peptides. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 69, 289e305 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nongonierma, A. B. , Lalmahomed, M. , Paolella, S. , & FitzGerald, R. J. (2017). Milk protein isolate (MPI) as a source of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP‐IV) inhibitory peptides. Food Chemistry, 231, 202–211. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.03.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nongonierma, A. B. , Maux, S. L. , Dubrulle, C. , Barre, C. , & FitzGerald, R. J. (2015). Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) protein hydrolysates with in vitro dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP‐IV) inhibitory and antioxidant properties. Journal of Cereal Science, 65, 112–118. 10.1016/j.jcs.2015.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panjaitan, F. C. A. , Gomez, H. Y. R. , & Chang, Y. W. (2018). In silico analysis of bioactive peptides released from giant grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus) roe proteins identified by proteomics approach. Molecules, 23, 2910 10.3390/molecules23112910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, D. , & Pal, M. (1998). Chenopodium: Seed protein, fractionation and amino acid composition. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 49(4), 271–275. 10.3109/09637489809089398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singha, B. P. , Vij, S. , & Hati, S. (2014). Functional significance of bioactive peptides derived from soybean. Peptides, 54, 171–179. 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu, M. L. , Cheng, S. Z. , Lu, W. H. , & Du, M. (2018). Advancement and prospects of bioinformatics analysis for studying bioactive peptides from food‐derived protein: Sequence, structure, and functions. Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 105, 7–17. 10.1016/j.trac.2018.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Udenigwe, C. C. , & Fogliano, V. (2017). Food matrix interaction and bioavailability of bioactive peptides: Two faces of the same coin? Journal of Functional Foods, 35, 9–12. 10.1016/j.jff.2017.05.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Udenigwe, C. C. , & Mohan, A. (2014). Mechanisms of food protein‐derived antihypertensive peptides other than ACE inhibition. Journal of Functional Foods, 8C, 45–52. 10.1016/j.jff.2014.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uraipong, C. , & Zhao, J. (2018). In vitro digestion of rice bran proteins produces peptides with potent inhibitory effects on α‐glucosidase and angiotensin I converting enzyme. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 98, 758–766. 10.1002/jsfa.8523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venuste, M. , Zhang, X. M. , Shoemaker, C. F. , Karangwa, E. , Abbas, S. , & Kamdem, P. E. (2013). Influence of enzymatic hydrolysis and enzyme type on the nutritional and antioxidant properties of pumpkin meal hydrolysates. Food and Function, 4, 811–820. 10.1039/c3fo30347k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcacundo, R. , Martínez‐Villaluenga, C. , & Hernández‐Ledesma, B. (2017). Release of dipeptidyl peptidase IV, α‐amylase and α‐glucosidase inhibitory peptides from quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) during in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Journal of Functional Foods, 35, 531–539. 10.1016/j.jff.2017.06.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcacundo, R. , Miralles, B. , Carrillo, W. , & Hernández‐Ledesma, B. (2018). In vitro chemopreventive properties of peptides released from quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) protein under simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Food Research International, 105, 403–411. 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials