Abstract

Replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) simulation is a popular enhanced sampling method that is widely used for exploring the atomic mechanism of protein conformational change. However, the requirement of huge computational resources for REMD, especially with the explicit solvent model, largely limits its application. In this study, the availability and efficiency of a variant of velocity-scaling REMD (vsREMD) was assessed with adenylate kinase as an example. Although vsREMD achieved results consistent with those from conventional REMD and experimental studies, the number of replicas required for vsREMD (30) was much less than that for conventional REMD (80) to achieve a similar acceptance rate (∼0.2), demonstrating high efficiency of vsREMD to characterize the protein conformational change and associated free-energy profile. Thus, vsREMD is a highly efficient approach for studying the large-scale conformational change of protein systems.

Significance

Replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) simulation is one of the most popular enhanced sampling methods to explore protein conformation space and associated free-energy landscape. However, conventional REMD with an explicit solvent model requires huge computational resources, immensely limiting its application. To improve sampling efficiency, a variant of velocity-scaling REMD (vsREMD) was suggested and tested on adenylate kinase in this study. With many fewer replicas in comparison with conventional REMD, vsREMD achieved consistent results with conventional REMD, demonstrating the high reliability of vsREMD.

Introduction

Not only appropriate structural conformation but also dynamic properties are important for proteins to perform their biological function (1,2). Although the number of experimentally determined structures of proteins and their complexes with ligands is rapidly increased in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (3), it is still a great challenge to obtain dynamic properties of proteins and associated free-energy landscapes by experimental protocol. Especially, only a few transient structures along the protein conformational change pathway have been successfully resolved with special experimental techniques (4, 5, 6, 7, 8). For example, adenylate kinase (AdK), a monomeric phosphotransferase enzyme that catalyzes the phosphoryl transfer reaction (ATP-Mg2+ + AMP ↔ ADP-Mg2+ + ADP), undergoes a large-scale conformational change from open (9) to closed (10) to facilitate its substrate hydrolysis (11,12). Most experimental structures of AdK are in open states without inhibitors or in closed states with inhibitors, e.g., AP5A (Fig. 1; (13)), indicating the high flexibility of the AdK structure (4, 5, 6,14). However, important intermediate conformations of AdK that link different functional states are rather scarce in the PDB. Thus, we are still far away from fully understanding the detailed mechanism of the conformational change of AdK, especially at the atomic level.

Figure 1.

(A) Open and closed structures of AdK. Open (PDB: 4AKE) and closed (PDB: 1AKE) structures of the E. coli AdK are shown in cartoon. The stable and conserved CORE domains of two structures are shown in green. The LID domains of the closed and open forms are colored in red and orange, respectively. The NMP domains of the closed and open forms are colored in blue and cyan, respectively. (B) The structure of AdK inhibitor AP5A is shown in cartoon. (C) The structure of Mg2+•AP5A is shown in cartoon. To see this figure in color, go online.

In addition to the experimental methods, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have been widely used to investigate the atomic mechanism of protein conformational change. For example, conventional MD (cMD) simulations have been performed to address the dynamic mechanism of AdK and possible influence of substrates (15, 16, 17, 18). However, due to the simulation timescale and its inherent low-efficient sampling, cMD is very difficult to obtain the complete conformational change process (19). Thus, enhanced sampling methods have been developed to improve the sampling efficiency of cMD, including metadynamics (20) and umbrella sampling (21). Progress has been achieved by employing such enhanced sampling methods for AdK (14,20,22, 23, 24, 25, 26). For example, Parrinello et al. (20) elucidated the thermodynamics and structural properties underlying the AdK functional conformation transitions with a metadynamics-based approach. Zacharias et al. (21) used umbrella sampling to calculate the free-energy landscapes along the opening of LID (ATP binding domain of residues 118−167) and NMP (AMP binding domain of residues 30−67) in the apo- and substrate-bound states, revealing a strong dependence of AdK’s conformational ensembles on substrate type and binding mode. However, it is quite challenging to select a proper reaction coordinate a priori for free-energy profile calculation in metadynamics and umbrella sampling simulations (27,28).

In comparison to the above-mentioned methods, another popular and widely used enhanced method that does not require knowledge of an a priori reaction coordinate is replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) simulation, which utilizes a series of replicas under a range of temperatures (29,30). In REMD, protein conformations (replicas) are exchanged at different temperatures according to the Metropolis exchange criterion. To achieve a proper exchange ratio, REMD requires a small temperature interval (ΔT), which greatly increases the number of replicas, especially in the simulation under an explicit solvent model. Because the number of replicas required in conventional REMD scales as f1/2 (31,32), where f is the number of the degrees of freedom of the whole simulation system, in a biomolecule simulation system, the number of solvent atoms is much larger than that of the solute. Thus, reducing the degrees of freedom of solvent atoms should be able to decrease the replicas required for REMD simulation. Indeed, Liu et al. (33) developed a method, namely replica exchange with solute tempering (REST), in which only the solute biomolecule was effectively heated up, whereas the solvent remained cold in higher-temperature replicas. Significant reduction in the required number of replicas in the REST was observed (33). However, REST was not much more efficient in larger systems (34). Later, the same group developed a new version of REST2, which greatly improved its sampling efficiency (35). Using the implicit solvent model instead of explicit solvent is another promising approach. Okur et al. (36) developed a hybrid implicit/explicit solvent model based on a replica exchange technique to decrease the number of replicas, in which the conformational sampling utilized the explicit solvent, whereas the exchange moves based on the implicit solvent model. However, it raised an issue that there is no one-to-one relation between the solvation energies calculated with the explicit and implicit solvent models. Quite a number of simulation studies have revealed the weakness of implicit solvation models in structural modeling and folding thermodynamics evaluation (37, 38, 39, 40, 41). To reduce the effect of the implicit solvent model in REMD, we previously developed a, to our knowledge, novel velocity-scaling optimized hybrid explicit/implicit solvent REMD approach (hREMD), in which we compensated for the difference in energies resulting from the two solvent models by rescaling the velocities accordingly. The hREMD method is reliable and efficient for studying protein folding and conformational transition (42, 43, 44). However, the reliability of hREMD is, in principle, inevitably affected by the used implicit solvation model. For example, Beauchamp found that the use of implicit solvation may lead to poor accuracy in some cases (40,45, 46, 47), and similar conclusions were obtained by Alexey et al. (48).

To fully avoid the flaws originating from the implicit solvent model, a variant of velocity-scaling REMD (vsREMD) was suggested. The criteria for an exchange attempt in vsREMD uses the explicit protein-solvent interaction potential (Ppw), which is different from hREMD that used the implicit protein-solvent interaction potential (Pis). Thus, vsREMD is performed solely under the explicit solvent model with the sum of the intraprotein interaction (Ppp) and protein-solvent interaction (Ppw) as the criterion for the exchange attempt to reduce the replica number. Once the exchange attempt completes, velocity rescaling is used to compensate for the lost solvent-solvent interaction (Pww) in the exchange. Application of vsREMD on AdK revealed highly consistent results with that of both conventional REMD and experimental data. Moreover, in achieving a similar acceptance rate, the number of replicas used in vsREMD is only 30, whereas that in conventional REMD is 80, demonstrating the high efficacy of vsREMD.

Methods

vsREMD

Temperature REMD (29,30,49) exchanges two adjacent replicas at temperatures T1 and T2 with probability ω:

| (1) |

where E is the energy of the simulation system and β = 1/kBT. The resulting random walk in temperature space allows a replica to escape from local minima, achieving a significant enhancement of conformation sampling (29).

In REMD simulation, the E of the system with N particles is the sum of the potential energy Epot(x), which depends on the coordinates x, and the kinetic energy Ekin(v), which depends on the velocity v:

| (2) |

| (3) |

Because scaling all velocities by a factor of r changes the kinetic energy by

| (4) |

it follows that a rescaling of velocities with

| (5) |

leads to , and, therefore, ΔEkin = 0. Therefore, the probability for an exchange is given solely by the difference of potential energies,

| (6) |

In the velocity-scaling optimized hREMD method proposed in our previous study (42), the potential energy of the system is divided into three terms as

| (7) |

where Pww is the solvent-solvent interaction. On the other hand, the kinetic energy can be written as

| (8) |

with KP being the kinetic energy term resulting from protein atoms and Kw being the one resulting from water atoms.

The system evolves between exchange attempts with the potential energy function given by Eq. 7 that is similar to conventional REMD simulation. However, on exchange attempts, an implicit solvent term Pis is applied, which is an approximation for PPw + Pww. The difference between the two potential energy terms used in simulations (PPP + PPw + Pww for explicit model) and exchange attempts (Q = Ppp + Pis for implicit model) is given by

| (9) |

With this notion, we can rewrite the potential energy as

| (10) |

Therefore, exchange attempts between neighbor replicas are accepted with probability ω(1 ↔ 2) = min(1,exp(D)) with

| (11) |

where and are the kinetic energies of the system at temperature T1 before and after exchange, respectively; and are the kinetic energies of the system at temperature T2 before and after exchange, respectively; ΔQ = Q(2) − Q(1); and ΔH = H(2) − H(1). The hREMD method uses Eqs. 12 and 13 below to uniformly rescale the velocities of all particles,

| (12) |

| (13) |

where v(1) and are the velocities of replica 1 before and after exchange, respectively, and v(2) and are the velocities of replica 2 before and after exchange, respectively. Rescaling the velocities in Eqs. 12 and 13 leads to

| (14) |

Hence, when Eq. 14 is plugged into Eq. 11, exchange attempts are accepted with probability

| (15) |

As discussed above, the reliability of hREMD is, in principle, inevitably affected by the used implicit solvation model. To avoid the drawback, we suggested in this study a new, to our knowledge, approach, namely vsREMD, that replaces the implicit solvent term (Pis) by the explicit protein-solvent interaction potential (PPw) in Q; thus,

| (16) |

With this replacement, the exchange attempts in the current vsREMD are accepted with the probability

| (17) |

In addition, consistent with previous hREMD, we compensate for the difference in energies resulting from MD simulations and exchange attempts by rescaling the velocities accordingly and therefore ensure convergence to the correct ensemble.

Simulation on AdK with vsREMD

The temperature range in vsREMD for this study is from 283 to 450 K with 30 replicas to obtain an average acceptance probability of ∼20% between neighboring replicas at an interval of 1000 steps (Table S1). For each replica, the overall simulation time lasted for 100 ns. All simulations were carried out with a modified version of GROMACS 4.6.5 (50) to allow performing vsREMD. The closed conformation of AdK (PDB: 1AKE) (10) was used as an initial structure for our simulations. Three different simulation systems were built, including the apo AdK, AdK bound with AP5A, and AdK bound with both Mg2+ and AP5A. All crystal water molecules were deleted. The general Amber force field (51) and AM1-BCC charges were applied to AP5A by using the tleap module and the antechamber module. Then, the program amb2gmx.pl (52) was used to convert the force field parameters of AP5A from AMBER format to GROMACS format. The RSFF2 force field (53,54) was adopted to generate the force field parameters of proteins. Each protein or complex (AdK bound with AP5A or AdK bound with Mg2+ and AP5A) was solvated in a cubic box of TIP3P water molecules, keeping the boundary of the box at least 10.0 Å away from any solute atom. An appropriate number of counterions were added to neutralize each system.

For removing contacts formed by the preparation of system, each system was minimized using the steepest descent algorithm. MD simulation was then run for 5 ns to heat the system from 0 to 300 K by fixing the solute with a harmonic restraint of force constant of 1000 kcal mol−1 nm−2, followed by another 5-ns MD simulation with the protein Cα atoms and small molecule restrained. The LINCS algorithm (55) is applied to constrain the bonds connecting hydrogen atoms, and the time step was set to 2.0 fs. Periodic boundary conditions were applied. Particle mesh Ewald (56) was applied to treat the long-range electrostatic interactions, and the nonbonded cutoff of 12 Å was used. The v-scale algorithms (57) was adopted to control the temperature of the system.

Simulation on AdK with conventional REMD

To validate the performance of vsREMD, a conventional explicit solvent REMD simulation for the apo AdK was performed with the same initial structures and parameters as that of vsREMD. To reach a similar exchange acceptance ratio as vsREMD, the same temperature range (283–450 K) was separated by a total of 80 replicas (Table S1).

Results and Discussion

Consistent results between vsREMD and conventional REMD

For assessing the efficiency and reliability of vsREMD, the temperature histories of one replica in apo AdK were monitored and the results revealed that the replica of vsREMD is ergodic for every temperature (Fig. 2). Similar results were observed for the conventional REMD (Fig. S1). Because the acceptance ratio between neighboring replicas is an important criterion for gauging the sampling efficiency of REMD (58), we calculated the mean acceptance probability of vsREMD and conventional REMD to be 20.6% and 19.0%, respectively. Although both ratios were satisfactory, vsREMD utilized only 30 replicas, whereas conventional REMD required 80 replicas, demonstrating that vsREMD was more efficient than conventional REMD.

Figure 2.

Temperature history of one replica in the vsREMD simulation of the apo AdK.

The root mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the heavy atoms of the apo AdK referred to its closed conformation was plotted for a single replica of both vsREMD and conventional REMD. Both methods showed similar low and high RMSD values, suggesting that both methods could efficiently capture the large-scale conformation change in geometric space (Fig. S2, A and B). The representative structures at low and high RMSD values were extracted from structures within 1.0 Å < RMSD < 1.5 Å and 6.0 Å < RMSD < 7.0 Å, respectively, which could be superposed very well with the experimental determined closed and open conformations (Fig. S3, A and B). Thus, the conformational transition of AdK could be effectively sampled by both methods, as the RMSD experienced many times of low-to-high (1.0–6.0 Å) or high-to-low (6.0–1.0 Å) values.

For comparing the thermodynamic parameters, one-dimensional free-energy profiles as the function of RMSD in reference to its closed conformation were calculated with error bars estimated by bootstrapping error analysis (59). Similar profiles in Fig. 3 A demonstrated that the open state of apo AdK (RMSD > 6.5 Å) is more energetically favorable than the closed state (RMSD < 1.5 Å), consistent with the experimental observation in the crystal structures. To further monitor the convergence of vsREMD, the free-energy profiles calculated from different simulation times were calculated. Only a slight difference among the free-energy profiles calculated from 90-, 95-, and 100-ns trajectories was observed, suggesting vsREMD had converged in the 100-ns simulations (Fig. S4). In addition, the predicted energy barrier (ΔG, 1.20 kcal/mol) by vsREMD was in good agreement with that by conventional REMD (1.32 kcal/mol) (Fig. 3 A). To further investigate the conformational transition pathway of apo AdK, clustering analysis was performed with the program kclust (60) on the snapshots extracted from the two simulations. As shown in Fig. 3 B, the represented conformation of the transition states obtained from both vsREMD (1.5 Å < RMSD < 2.0 Å) and conventional REMD (1.5 Å < RMSD < 2.0 Å) were very similar to each other. Therefore, in comparison to the conventional REMD, the vsREMD could also be able to accurately sample the conformational transition pathway and predict the associated thermodynamic parameters.

Figure 3.

(A) The one-dimensional free-energy profiles as the function of heavy atom RMSD with respect to the closed structure of AdK for the conformational transitions of apo AdK from closed to open states by using conventional (colored by black line) and vsREMD (red line) methods. The error bars were calculated by bootstrapping error analysis. (B) The superimposed image represents transition structures obtained from conventional (green) and vsREMD (red) methods. To see this figure in color, go online.

AdK consists of three domains (Fig. 1 A): the LID, NMP, and CORE domain (residues 1–29, 68–117, and 161–214). By superposing the represented transition structures and the open conformation to the closed conformation (Fig. S5), we found that only the LID domain in the transition state moved significantly toward the open conformation, whereas the CORE and NMP domains almost remained in the closed conformation, suggesting that the LID should transit to open firstly during AdK undergoes its conformational change from the closed to open, being highly consistent with other simulations (14,21) and experiment observations (6).

To make a direct assessment of conformation space sampled by vsREMD, free-energy landscapes as a function of the mass centered distance between the LID and CORE domains and that of the NMP and CORE domains, which have been widely used in other simulations (61), were calculated based on the trajectories from vsREMD and conventional REMD. As a whole, the free-energy profile obtained from vsREMD was very similar to that of the conventional REMD (Fig. 4, A and B), suggesting the consistent conformation space was sampled by the two methods. Checking carefully, the conformation space sampled by vsREMD was a bit larger than that obtained by conventional REMD, which was consistent with the lower energy barrier calculated from vsREMD (Fig. 3), indicating that vsREMD might be more efficient than conventional REMD in sampling a large conformation space. To check the conformation space sampled by the conventional REMD, the simulation time was extended to 150 ns, and very similar results were obtained (Fig. S6). Impressively, 14 experimental intermediate structures that have been used to predict the conformational change pathway (62,63) were located along the transition pathway calculated from vsREMD and conventional REMD, which was also consistent with the result by another simulation method called dynamic importance sampling MD simulation (61), again demonstrating the reliability of vsREMD. Additionally, another model system of alanine dipeptide (ACE-ALA-NME) in the explicit solvent was performed for 100 ns with vsREMD (eight replicas) and conventional REMD (16 replicas). For this small system, the PMFs of ϕ and ψ dihedral angles for vsREMD were identical to those obtained from conventional REMD (Fig. S7), further validating the accuracy of vsREMD.

Figure 4.

Free-energy landscape as a function of the mass-centered distance between the LID and CORE domains and the distance between the NMP and CORE domains of AdK at 300 K from vsREMD (A) and conventional REMD (B). The locations of 14 experimental intermediate structures of AdK are marked by PDB code. To see this figure in color, go online.

Structural flexibility of the LID domain in the apo AdK

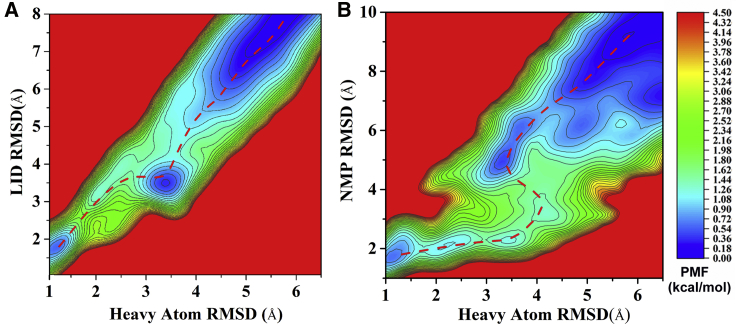

As shown in Fig. 3, no large energy barrier was found when AdK underwent a large-scale conformation change (RMSD value from 8.0 to ∼4.0 Å). In this wide and shallow free-energy well, the LID domain could easily move from the open state to the partially closed state, whereas the NMP domain keep relatively steady around its open state (Fig. S8). These structural characteristics were in good agreement with the experimentally observed, partially closed conformation of apo AdK reported by Henzler-Wildman et al. (6). Thus, we focused our further analysis on the motion of LID in the transition process. As shown in Fig. 5 A, the free-energy profile of LID displayed a diagonal shape, suggesting that the conformation transition of the LID domain takes place in a similar way to that of AdK. In contrast, the free-energy profile of NMP exhibited an S-like shape (Fig. 5 B), suggesting that the transition of the NMP domain followed the movement of the LID domain. Thus, the conformational change of apo AdK was more likely a step-by-step transition initiated by the LID domain, which was consistent with other simulation results (14,25).

Figure 5.

Two-dimensional free-energy landscape as a function of the LID (A) or NMP (B) RMSD and the heavy-atom RMSD in reference to the initial closed structure at 300 K from vsREMD. To see this figure in color, go online.

To evaluate the timescale of the conformational change in apo AdK, the Kramers theory (64) was applied to calculate the time of conformational change of the LID opening and closing. The conformational relaxation time (t) is given by Eq. 18

| (18) |

where ωmin and ωmax are frequencies that characterize the curvature of the free-energy profile at the unfolded well and (inverted) barrier top, respectively; Dmax is the diffusion constant at the barrier top; ΔG∗ is the free-energy barrier; kB is the Boltzmann’s constant; and T is the absolute temperature. It has been reported that the approximation of ωmin ≈ ωmax and Dmax ≈ Dmin are reasonable for the estimation of the mean folding time for small proteins (64, 65, 66). Accordingly, Eq. 18 could be rewritten as Eq. 19.

| (19) |

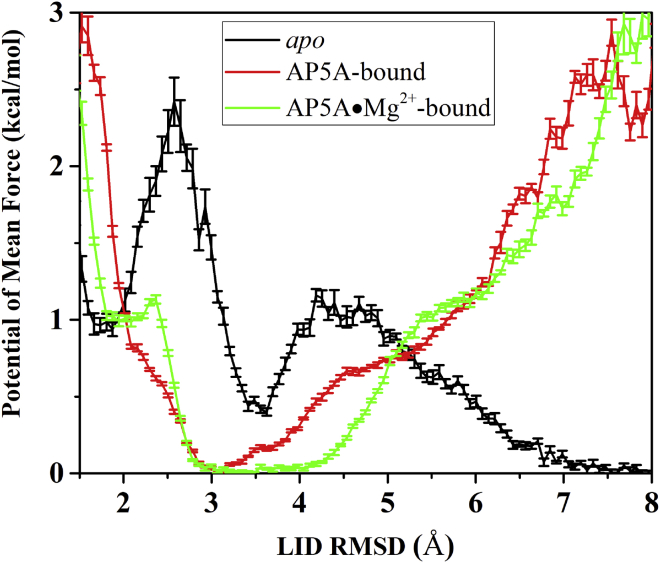

The energy barrier ΔG∗ measured from one-dimensional free-energy profile for LID opening and closing was 1.45 and 2.00 kcal/mol, respectively (Fig. 6), and the ωmin also measured from Fig. 6 for LID opening and closing was 0.059 and 0.049, respectively. The Dmin of the LID opening and closing was 2.83 and 3.00, respectively (data from our previous study (25), the detailed protocols for calculating this parameter were included in the section Computational Methods in the Supporting Materials and Methods). Accordingly, the time was calculated to be ∼28.68 μs for LID opening and 117.66 μs for LID closing, respectively, which has good correlation with the experimental data (6) and was also consistent with our previous simulation results (25), implying the high reliability of vsREMD in studying the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of large-scale protein conformational changes.

Figure 6.

The one-dimensional free-energy profiles as the function of LID RMSD respective to the closed structure of AdK for the conformational transitions of apo AdK (colored in black), AdK bound with AP5A (red), and AdK bound with Mg2+⋅AP5A (green). To see this figure in color, go online.

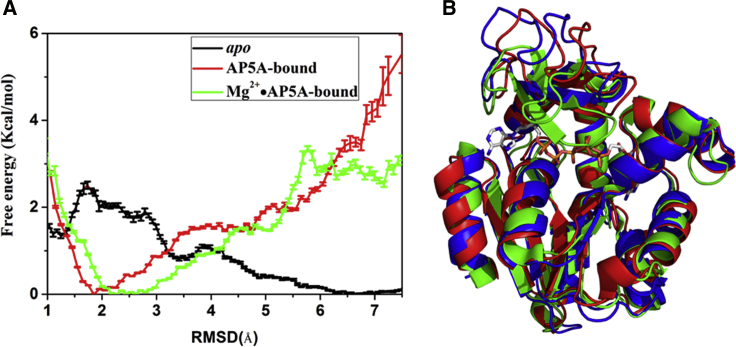

Ligand-induced biasing to the closed state of AdK

As shown in Fig. 7, the binding of AP5A or Mg2+⋅AP5A significantly destabilized the open state, even though it stabilized the closed state. The comparison of the free-energy landscape of apo AdK to that of AP5A- or Mg2+⋅AP5A-bound states revealed intersections at RMSD around 3.2 or 4.2 Å (Fig. 7 A), respectively. These intersection positions could be considered as where the ligand binding process occurred according to the Marcus theory of electron transfer. Thus, the binding of the ligand should occur concurrently with the conformational change, suggesting that the conformational transition of AdK might follow the “population-shift” model: apo AdK could adopt various conformations, and the ligand selectively binds to some active conformations and induces the equilibrium shifted toward the final ligand-bound conformation, being in good agreement with previous simulation results (14,24).

Figure 7.

(A) The one-dimensional free-energy profiles as the function of RMSD respective to the closed structure of AdK for the conformational transitions of apo (black line), AP5A-bound (red line), and Mg2+⋅AP5P -bound (green) by vsREMD. (B) The image represents stable structures of AP5A-bound (red) AdK, Mg2+⋅AP5A-bound (blue) AdK, and the crystal-closed structure (green). To see this figure in color, go online.

Mg2+ accelerated the opening of the LID domain

To evaluate the effect of Mg2+ on the conformation transition of AdK, the most stable conformations in AP5A- or Mg2+⋅AP5A-bound states were extracted and superimposed to the closed conformation. As shown in Fig. 7 B, although the represented conformations were very similar to each other, there were still minor changes in the LID domain, suggesting that the LID could sample large conformational space even in the ligand-bound state, being consistent with the recently Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiment (8). By comparing the stable conformations in AP5A- and Mg2+⋅AP5A-bound states, the LID in the Mg2+⋅AP5A-bound state was more open than that in the AP5A-bound state, suggesting that Mg2+ could accelerate the opening of the LID domain, being consistent with the NMR result by Kern et al. (12). By comparing one-dimensional free-energy profiles as the function of LID RMSD in reference to the closed conformation for both AP5A- and Mg2+⋅AP5A-bound states, we found that a wide and shallow free-energy well was present in the range of LID RMSD values from 2.5 to ∼4.8 Å without any observable energy barrier (Fig. 6), consistenting with the experimentally observed flexibility of LID in the ligand-bound AdK system. The free-energy barrier for the opening of LID in the binding of Mg2+⋅AP5A was even smaller than that in the AP5A-bound states (Fig. 6), indicating that Mg2+ could accelerate the opening of the LID.

To evaluate the effect of Mg2+ on the binding ability of AP5A, the interactions between AP5A and AdK were calculated for both the AP5A-bound and Mg2+⋅AP5A-bound states. As shown in Fig. 8, the change of electrostatic interaction was much larger than that of the van der Waals (vdW) interaction, indicating the crucial role of the electrostatic interaction induced by the Mg2+ in the binding of AP5A and the conformational change of AdK. Interestingly, the total interaction (including electrostatic and vdW interactions) was stronger in the AP5A-bound system than that in the Mg2+⋅AP5A system, especially in the closed state (RMSD values from 1.0 to 3.0 Å), suggesting that the Mg2+ could weaken the binding of AP5A to AdK. By clustering the conformations within the RMSD values from 1.0 to 3.0 Å, the representative conformation of the Mg2+⋅AP5A-bound system revealed that the electrostatic potential of the LID and CORE domains near the binding site were rather positive, suggesting that the two domains are difficult to keep close in the apo state (Fig. S9), although the binding of the negatively charged ligand AP5A could reduce or eliminate the electrostatic repulsion between the two domains, making the two domains possibly bind with each other. As shown in Fig. 8, the electrostatic interactions predominated the total binding interactions. While in the Mg2+⋅AP5A-bound state, the electrostatic interaction between AP5A and the LID domain could be decreased by Mg2+ because it takes the same positive charge as the LID domain. That may be an important reason for the accelerated opening of LID by adding Mg2+, which was observed in experiments (12).

Figure 8.

The total, electrostatic and vdW interaction energies between AP5A and AdK in the conformational transitions of AdK in the AP5A-bound (solid line) and Mg2+⋅AP5A-bound state (dotted line). The total, electrostatic, and vdW interactions were colored in black, red, and green, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

Conclusions

In this study, a variant of velocity-scaled REMD that used the sum of intraprotein interaction (Ppp) and protein-solvent interaction (Ppw) as the criterion for the exchange attempt was assessed. To demonstrate the reliability and efficiency of vsREMD, the application on AdK in the apo, AP5A-, and Mg2+⋅ AP5A-bound states were performed, and the simulation results were compared to that obtained from the conventional REMD and experimental data. In the apo AdK system, a very similar conformational transition pathway and energy barrier were obtained from vsREMD and conventional REMD, but the number of replicas in vsREMD (30) is significantly reduced even with a similar average acceptance ratio in comparison to conventional REMD (80), demonstrating the high reliability and efficiency of vsREMD. Impressively, for the intrinsically flexible AdK, the experimentally determined intermediate structures could be captured along the conformational transition pathway predicated by the vsREMD. In addition, vsREMD simulation results suggested that the binding of AP5P biased AdK to a closed state and Mg2+ could accelerate the opening of the LID domain. In conclusion, vsREMD should be reliable and efficient in probing the large-scale conformational change pathway and associated free-energy landscape of protein. The high efficacy of the current vsREMD could be attributed to the significantly decreased freedom of solvent by using the sum of Ppp and Ppw for the exchange attempt, leading to significantly reduced replicas. Similarly, the hREMD used the sum of PPP and Pis for exchange attempt, which could also significantly reduce the required replicas. The mean acceptance rates for hREMD attempts based on snapshots from the vsREMD was ∼0.32, which was higher than that (0.2) in the current vsREMD, suggesting even lower replicas were required for the hREMD. Nonetheless, the current vsREMD avoids the requirement of implicit solvent model for the hREMD.

Author Contributions

J.W. and W.Z. designed the research. J.W. and C.P. performed the research. J.W., Y.Y., Z.C., Z.X., T.C., Q.S., and J.S. analyzed data. J.W., C.P., and W.Z. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (grant 2016YFA0502301), National Science & Technology Major Project “Key New Drug Creation and Manufacturing Program” (grant 2018ZX09711002), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81573350, 81872797, and 21403283). The simulations were partially run at TianHe 1 supercomputer in Tianjing and TianHe 2 supercomputer in Guangzhou and supported by the Special Program for Applied Research on Super Computation of the National Natural Science Foundation of China-Guangdong Joint Fund (the second phase) under grant no. U1501501.

Editor: Alemayehu Gorfe.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.01.001.

Contributor Information

Jinan Wang, Email: jawang@simm.ac.cn.

Weiliang Zhu, Email: wlzhu@simm.ac.cn.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Bakan A., Bahar I. The intrinsic dynamics of enzymes plays a dominant role in determining the structural changes induced upon inhibitor binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:14349–14354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904214106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammes G.G. Multiple conformational changes in enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry. 2002;41:8221–8228. doi: 10.1021/bi0260839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman H.M. The protein data bank: a historical perspective. Acta Crystallogr. A. 2008;64:88–95. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307035623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adén J., Wolf-Watz M. NMR identification of transient complexes critical to adenylate kinase catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14003–14012. doi: 10.1021/ja075055g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanson J.A., Duderstadt K., Yang H. Illuminating the mechanistic roles of enzyme conformational dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:18055–18060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708600104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henzler-Wildman K.A., Thai V., Kern D. Intrinsic motions along an enzymatic reaction trajectory. Nature. 2007;450:838–844. doi: 10.1038/nature06410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korzhnev D.M., Religa T.L., Kay L.E. A transient and low-populated protein-folding intermediate at atomic resolution. Science. 2010;329:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.1191723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelz B., Žoldák G., Rief M. Subnanometre enzyme mechanics probed by single-molecule force spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10848. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller C.W., Schlauderer G.J., Schulz G.E. Adenylate kinase motions during catalysis: an energetic counterweight balancing substrate binding. Structure. 1996;4:147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Müller C.W., Schulz G.E. Structure of the complex between adenylate kinase from Escherichia coli and the inhibitor Ap5A refined at 1.9 A resolution. A model for a catalytic transition state. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;224:159–177. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90582-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knowles J.R. Enzyme-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer reactions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1980;49:877–919. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.004305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerns S.J., Agafonov R.V., Kern D. The energy landscape of adenylate kinase during catalysis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:124–131. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinstein J., Vetter I.R., Goody R.S. Fluorescence and NMR investigations on the ligand binding properties of adenylate kinases. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7440–7450. doi: 10.1021/bi00484a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arora K., Brooks C.L., III Large-scale allosteric conformational transitions of adenylate kinase appear to involve a population-shift mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:18496–18501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706443104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lou H., Cukier R.I. Molecular dynamics of apo-adenylate kinase: a principal component analysis. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:12796–12808. doi: 10.1021/jp061976m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pontiggia F., Zen A., Micheletti C. Small- and large-scale conformational changes of adenylate kinase: a molecular dynamics study of the subdomain motion and mechanics. Biophys. J. 2008;95:5901–5912. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.135467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brokaw J.B., Chu J.W. On the roles of substrate binding and hinge unfolding in conformational changes of adenylate kinase. Biophys. J. 2010;99:3420–3429. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song H.D., Zhu F. Conformational dynamics of a ligand-free adenylate kinase. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang L., Liu C.W., Gao Y.Q. From thermodynamics to kinetics: enhanced sampling of rare events. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:947–955. doi: 10.1021/ar500267n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Formoso E., Limongelli V., Parrinello M. Energetics and structural characterization of the large-scale functional motion of adenylate kinase. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8425. doi: 10.1038/srep08425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeller F., Zacharias M. Substrate binding specifically modulates domain arrangements in adenylate kinase. Biophys. J. 2015;109:1978–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsunaga Y., Fujisaki H., Kidera A. Minimum free energy path of ligand-induced transition in adenylate kinase. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potoyan D.A., Zhuravlev P.I., Papoian G.A. Computing free energy of a large-scale allosteric transition in adenylate kinase using all atom explicit solvent simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:1709–1715. doi: 10.1021/jp209980b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J., Shao Q., Zhu W. Exploring transition pathway and free-energy profile of large-scale protein conformational change by combining normal mode analysis and umbrella sampling molecular dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014;118:134–143. doi: 10.1021/jp4105129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shao Q. Enhanced conformational sampling technique provides an energy landscape view of large-scale protein conformational transitions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016;18:29170–29182. doi: 10.1039/c6cp05634b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen J., Wang J., Zhu W. Zinc ion-induced conformational changes in new Delphi metallo-β-lactamase 1 probed by molecular dynamics simulations and umbrella sampling. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:3067–3075. doi: 10.1039/c6cp08105c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan A.C., Weinreich T.M., Shaw D.E. Assessing the accuracy of two enhanced sampling methods using EGFR kinase transition pathways: the influence of collective variable choice. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014;10:2860–2865. doi: 10.1021/ct500223p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsunaga Y., Komuro Y., Sugita Y. Dimensionality of collective variables for describing conformational changes of a multi-domain protein. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016;7:1446–1451. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansmann U.H.E. Parallel tempering algorithm for conformational studies of biological molecules. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997;281:140–150. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugita Y., Okamoto Y. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999;314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terakawa T., Kameda T., Takada S. On easy implementation of a variant of the replica exchange with solute tempering in GROMACS. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:1228–1234. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukunishi H., Watanabe O., Takada S. On the Hamiltonian replica exchange method for efficient sampling of biomolecular systems: application to protein structure prediction. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;116:9058–9067. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu P., Kim B., Berne B.J. Replica exchange with solute tempering: a method for sampling biological systems in explicit water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:13749–13754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506346102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang X., Hagen M., Berne B.J. Replica exchange with solute tempering: efficiency in large scale systems. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:5405–5410. doi: 10.1021/jp068826w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L., Friesner R.A., Berne B.J. Replica exchange with solute scaling: a more efficient version of replica exchange with solute tempering (REST2) J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:9431–9438. doi: 10.1021/jp204407d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okur A., Wickstrom L., Simmerling C. Improved efficiency of replica exchange simulations through use of a hybrid explicit/implicit solvation model. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2006;2:420–433. doi: 10.1021/ct050196z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onufriev A.V., Izadi S. Water models for biomolecular simulations. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018;8:e1347. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Onufriev A.V., Case D.A. Generalized born implicit solvent models for biomolecules. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2019;48:275–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-052118-115325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anandakrishnan R., Izadi S., Onufriev A.V. Why computed protein folding landscapes are sensitive to the water model. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019;15:625–636. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shao Q., Zhu W. How well can implicit solvent simulations explore folding pathways? A quantitative analysis of α-helix bundle proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017;13:6177–6190. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roe D.R., Okur A., Simmerling C. Secondary structure bias in generalized Born solvent models: comparison of conformational ensembles and free energy of solvent polarization from explicit and implicit solvation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:1846–1857. doi: 10.1021/jp066831u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang P.H., Best R.B., Blumberger J. A microscopic model for gas diffusion dynamics in a [NiFe]-hydrogenase. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:7708–7719. doi: 10.1039/c0cp02098b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu Y., Wang J., Zhu W. Increasing the sampling efficiency of protein conformational transition using velocity-scaling optimized hybrid explicit/implicit solvent REMD simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;142:125105. doi: 10.1063/1.4916118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu Y., Wang J., Zhu W. Structural insights into HIV-1 protease flap opening processes and key intermediates. RSC Adv. 2017;7:45121–45128. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beauchamp K.A., Lin Y.S., Pande V.S. Are protein force fields getting better? A systematic benchmark on 524 diverse NMR measurements. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:1409–1414. doi: 10.1021/ct2007814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kleinjung J., Fraternali F. Design and application of implicit solvent models in biomolecular simulations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2014;25:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nguyen H., Maier J., Simmerling C. Folding simulations for proteins with diverse topologies are accessible in days with a physics-based force field and implicit solvent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13959–13962. doi: 10.1021/ja5032776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anandakrishnan R., Drozdetski A., Onufriev A.V. Speed of conformational change: comparing explicit and implicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 2015;108:1153–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geyer C.J., Thompson E.A. Annealing Markov chain Monte Carlo with applications to ancestral inference. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;90:909–920. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abraham M.J., Murtola T., Lindahl E. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1–2:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J., Wolf R.M., Case D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mobley D.L., Chodera J.D., Dill K.A. On the use of orientational restraints and symmetry corrections in alchemical free energy calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;125:084902. doi: 10.1063/1.2221683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou C.Y., Jiang F., Wu Y.D. Folding thermodynamics and mechanism of five trp-cage variants from replica-exchange MD simulations with RSFF2 force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:5473–5480. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou C.Y., Jiang F., Wu Y.D. Residue-specific force field based on protein coil library. RSFF2: modification of AMBER ff99SB. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:1035–1047. doi: 10.1021/jp5064676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hess B., Bekker H., Fraaije J.G.E.M. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N⋅ log (N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:014101. doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen T.H., Minh D.D. Intermediate thermodynamic states contribute equally to free energy convergence: a demonstration with replica exchange. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016;12:2154–2161. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Efron B., Tibshirani R.J. Chapman and Hall/CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 1998. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feig M., Karanicolas J., Brooks C.L., III MMTSB tool set: enhanced sampling and multiscale modeling methods for applications in structural biology. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2004;22:377–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beckstein O., Denning E.J., Woolf T.B. Zipping and unzipping of adenylate kinase: atomistic insights into the ensemble of open<-->closed transitions. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;394:160–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diederichs K., Schulz G.E. The refined structure of the complex between adenylate kinase from beef heart mitochondrial matrix and its substrate AMP at 1.85 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;217:541–549. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90756-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schlauderer G.J., Proba K., Schulz G.E. Structure of a mutant adenylate kinase ligated with an ATP-analogue showing domain closure over ATP. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;256:223–227. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kubelka J., Hofrichter J., Eaton W.A. The protein folding ‘speed limit’. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Socci N.D., Onuchic J.N., Wolynes P.G. Diffusive dynamics of the reaction coordinate for protein folding funnels. J. Chem. Phys. 1996;104:5860–5868. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang L., Shao Q., Gao Y.Q. Thermodynamics and folding pathways of trpzip2: an accelerated molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:803–808. doi: 10.1021/jp803160f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.