Abstract

Background:

Lorcaserin, a high-affinity 5-HT2C receptor agonist approved for treating obesity, decreased self-administration of oxycodone and cue-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in preclinical studies. The current investigation is the first clinical trial to evaluate the ability of lorcaserin to alter the reinforcing and subjective effects of oxycodone.

Methods:

In this 7-week inpatient trial, 12 non-treatment-seeking volunteers (11 males) with moderate-to-severe opioid use disorder were detoxified from opioids. In a randomized cross-over fashion, participants were first stabilized on lorcaserin (10 mg BID) or placebo (0 mg BID). Participants underwent a two-week testing period during which the reinforcing and subjective effects of intranasal oxycodone were examined in verbal choice, cue-exposure, and progressive-ratio choice sessions. The two testing weeks were identical with the exception that during the first week, active oxycodone (10 mg) was available during verbal choice (self-administration) sessions, and during the second week placebo oxycodone was available. Subsequently, participants were stabilized on the other medication condition (placebo or lorcaserin) and underwent the same testing procedures again.

Results:

Lorcaserin did not alter oxycodone self-administration. However, lorcaserin had a trend to increase “wanting heroin” when oxycodone was available, and to accentuate oxycodone-induced miosis.

Conclusion:

Under the current experimental conditions, lorcaserin at a dose of 10 mg BID did not reliably decrease the abuse liability of oxycodone, even though the study was sufficiently powered (≥80%) to detect clinically meaningful differences in the main outcome variables between the placebo and active lorcaserin condition. Future research could explore a wider dose range of lorcaserin and oxycodone.

Keywords: Lorcaserin, oxycodone, self-administration, subjective effects, opioid use disorder

1. Introduction

The U.S. is in the midst of an evolving epidemic of opioid use disorder (OUD) and its related morbidity and mortality. In 2016, approximately 11.8 million people misused opioids, including 11.5 million misusing pain relievers and 948,000 using heroin (Ahrnsbrak et al., 2017). Opioids are currently the main driver of drug overdose deaths – opioids were involved in 47,600 overdose deaths in 2017 (68% of all fatal drug overdoses; Center for Disease Control, 2018). Multiple strategies are needed to address the nation’s current opioid crisis and improve the effectiveness of medication-assisted treatments (MAT) for OUD (Volkow, 2018).

Different medication approaches are available and have been used successfully – within a suitably supportive therapeutic environment – for treating OUD. These include long-acting μ-opioid agonists (methadone), partial agonists (buprenorphine; Johnson, 1992; Johnson et al., 2000; Ling and Wesson, 2003), and antagonists (naltrexone; Comer et al., 2006; DeFulio et al., 2012; Everly et al., 2011; Krupitsky et al., 2011, 2013, 2012). However, despite the clear clinical utility of these medications, approximately 40–50% or more of the patients who initiate treatment with them relapse and/or drop out of treatment within 6 months (DeFulio et al., 2012; Krupitsky et al., 2012; Soyka et al., 2008). Cue reactivity towards drug-related stimuli has been identified as an important predictor of relapse in abstinent heroin dependent patients following treatment (Marissen et al., 2006), and in methadone- or buprenorphine-maintained patients (Fatseas et al., 2011). Thus, strategies that effectively reduce cue reactivity along with opioid use may be particularly promising novel options for the treatment of OUD.

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) neurotransmission is involved in drug reward and cue reactivity by conferring modulatory control over the limbic-corticostriatal circuitry (see Cunningham and Anastasio, 2014 for review). Primarily supported by the cocaine literature, 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors seem to play a central role in mediating the influence of 5-HT on substance use and on traits, such as impulsivity, which contribute to the development of substance use disorders and relapse to drug use in humans. Of note, 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors oppose each other in their modulation of the abuse-related effects of cocaine – activation of 5-HT2A receptors stimulates and of 5-HT2C receptors inhibits the activity of dopamine systems (Howell and Cunningham, 2014). Mounting evidence from preclinical studies indicates that 5-HT2A receptor antagonists effectively reduce cue-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior, whereas 5-HT2C receptor agonists appear to be effective in reducing both intravenous self-administration of cocaine and nicotine, and cue-induced reinstatement of drug-associated responding (Cousins et al., 2014; Fletcher, 2002; Fletcher et al., 2012; Murnane et al., 2013; Nic Dhonnchadha et al., 2009; Pockros et al., 2011; Schenk et al., 2016).

Lorcaserin, a high-affinity 5-HT2C receptor agonist, was approved by the FDA in 2012 for treating obesity. Lorcaserin shows modest selectivity over 5-HT2A receptors and substantial selectivity over 5-HT2B receptors (Thomsen et al., 2008), is generally well tolerated (Nigro et al., 2013), and has low abuse potential among recreational polydrug users (Shram et al., 2011). In studies of rodents and nonhuman primates, lorcaserin decreased cue-reactivity and self-administration of nicotine (Briggs et al., 2016; Cousins et al., 2014; Higgins et al., 2012; Levin et al., 2011; Zeeb et al., 2015), ethanol (Rezvani et al., 2014), and stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine (Collins et al., 2015; Gerak et al., 2016; Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016). Importantly, these effects occurred at doses that did not overtly alter other ongoing behaviors. In humans, lorcaserin dose-dependently increased smoking cessation and prevented the weight gain that is typically associated with smoking cessation (Shanahan et al., 2016).

Less is known about the role of 5-HT2C receptor modulation of the reward-related behavioral effects of opioids. Lorcaserin at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg decreased opioid-induced behavioral sensitization – i.e., heroin-induced increase in distance traveled and decrease in immobility – and naloxone-precipitated opioid withdrawal symptoms in mice (Wu et al., 2015). Furthermore, a recent study showed that lorcaserin at a dose of 1 mg/kg significantly reduced oxycodone intake in rats (Neelakantan et al., 2017). At a dose of 1 mg/kg, lorcaserin also suppressed cue reactivity 24 h after the last oxycodone self-administration session, and doses of 0.5 and 1 mg/kg suppressed cue reactivity after extinction from oxycodone self-administration; that is, lorcaserin reduced cue-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. These results indicate that lorcaserin may be therapeutically useful for promoting abstinence and preventing relapse in OUD. However, the effects of lorcaserin in humans on behaviors associated with OUD are unknown. Therefore, the current investigation sought to test whether lorcaserin has clinical utility as a non-opioid treatment for OUD.

Applying a cross-over design, we evaluated the ability of lorcaserin (10mg BID) versus placebo (PBO) to affect oxycodone self-administration and positive subjective effects, as well as opioid craving and physiological responses to drug cues in opioid-dependent volunteers. We hypothesized that lorcaserin would be superior to placebo in decreasing indicators of the abuse potential of oxycodone.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant recruitment and selection

Non-treatment seeking, physically healthy adults with moderate-to-severe OUD who were physically dependent on opioids were recruited using print and online advertisements in the New York City (NYC) area. After pre-screening via telephone to verify basic eligibility, potential study volunteers were invited for in-person screening visits to the New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI). In-person screening included comprehensive physical and psychiatric examinations, electrocardiogram, clinical laboratory tests (complete blood count, blood chemistry, urinalysis), naloxone challenge (observable symptoms of withdrawal after an intramuscular injection of 0.2 – 0.8 mg of naloxone to verify physiological dependence on opioids), and clinical interviews. Urine toxicology for drugs of abuse and alcohol breathalyzer tests were performed at every screening visit. Main exclusion criteria were substance use disorders other than opioids, nicotine or caffeine; psychiatric or medical conditions that might have interfered with the ability to provide informed consent or with study participation; pregnancy or lactation; sensitivity, allergy, or contraindication to opioids, lorcaserin or similar medications; and use of an investigational drug within the past 30 days.

2.2. Study Design

After signing informed consent, eligible volunteers were admitted to our secure inpatient unit for the duration of the 7-week trial. Participants were compensated $25/day with a $25/day bonus for completion of the study. During Week 1, participants were detoxified from opioids and emergent withdrawal symptoms were treated with supplemental medications (clonidine, clonazepam, compazine, ketorolac tromethamine, ondansetron, ibuprofen or acetaminophen, trazodone, and zolpidem) until withdrawal symptoms dissipated, based on physician judgment using Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS) scores as a guide. These medications were discontinued before participants received study drug, except for oral doses of trazodone or zolpidem which were available on request at bedtime throughout the current study. Participants who were cigarette smokers were escorted outside for smoking breaks at fixed intervals. During testing weeks smoking breaks were only available in the afternoon, after all laboratory sessions had been completed. Nicotine patches (14 mg of nicotine delivered over 24 hours) were available on request. If a participant requested a patch, patches had to be worn every day to avoid fluctuations in nicotine levels.

The study was designed as a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover medication trial. During the first study phase, in Week 2 after the detoxification period, participants were block-randomized to either the active (10 mg BID) or PBO (0 mg BID) lorcaserin condition, with a block size of two. We used the FDA-approved 10-mg, immediate-release formulation of lorcaserin twice daily, based on the safety and tolerability observed in previous studies for weight management (Greenway et al., 2016 for review) and smoking cessation (Shanahan et al., 2016).

During a 4 or 5-day stabilization period (Week 2) oral lorcaserin or PBO lorcaserin was administered under double-blind conditions. Participants and study staff conducting laboratory sessions were blind to the lorcaserin condition; the study medical monitor was not blinded for safety purposes. During Weeks 3 and 4, participants underwent laboratory testing sessions. During the second stabilization period (Week 5), participants were switched to the other lorcaserin condition [PBO lorcaserin (0 mg) or active lorcaserin (10 mg) BID], and subsequently underwent the same testing sessions again during testing Weeks 6–7, which were identical to Weeks 3–4. For safety reasons, participants’ vital signs were monitored throughout all laboratory sessions, in addition to weekly or as needed blood chemistries, weekly electrocardiograms, daily urine drug toxicology, and daily adverse events (AE) assessments.

At the conclusion of the study, participants were given an exit interview. Those who were interested in treatment for their drug use at the end of the study were offered referrals to studies at our Substance Treatment and Research Service or other treatment providers. Participants returned weekly for their study payments and safety monitoring for several weeks after study completion. At each of these weekly visits, participants’ interest in treatment and drug use patterns were assessed (via self-report and urine drug toxicology). Within 1 week after discharge, assessments were made of AEs using the Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Events (SAFTEE; Levine and Schooler, 1986), pregnancy (using a urine pregnancy test), general health (complete blood count, blood chemistry, urinalysis, blood pressure, heart rate, body weight, EKG), and suicide risk (Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale; Posner et al., 2011).

2.3. Experimental Sessions

During testing Weeks 3–4 and 6–7, laboratory sessions took place Monday through Friday, and participants completed different types of sessions (see Table 1 for a representative depiction of the test week study design).

Table 1.

Study Design – Testing Weeks (Weeks 3–4 and Weeks 6–7)

| First Week (Oxycodone Available) | Second Week (Placebo Available) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 |

| Sample Oxy 10mg & $10 | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Sample Oxy 10mg & $10 | Sample Placebo & $10 | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Sample Oxy 10mg & $10 |

| Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | ||

| Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Cue Reactivity | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Cue Reactivity |

| Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | ||

| Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | PR Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | Verbal Choice | PR Choice |

Oxy: Oxycodone; PR: Progressive Ratio Procedure

2.3.1. Sample Session (Day 1):

On Monday mornings, participants received $10 and an experimenter-administered sample dose of intranasal (IN) active oxycodone (10 mg, weeks 3 and 6) or PBO oxycodone (0 mg, weeks 4 and 7). We chose a fixed sequence of oxycodone and placebo to mimic the clinical setting in which, typically, opioid use is ceased after a period of active use, oftentimes followed by relapse to opioid use.

2.3.2. Verbal Choice Sessions (Days 1–4):

Participants had the choice to receive the sampled oxycodone dose IN or money each hour for the 4 hours following the sample dose (Day 1) and also on Tuesdays through Thursdays (Days 2–4; every hour for 5 hours beginning at 10 am). A simple verbal choice procedure was used whereby participants indicated verbally to research staff whether they would like to receive drug or money.

2.3.3. Drug Exposure (Sample) Session (Day 5):

On Friday mornings, participants received another experimenter administration of $10 and 10 mg oxycodone (the oxycodone dose on Day 5 was always active).

2.3.4. Cue Exposure Session (Day 5):

Following the Friday sample session, participants completed a cue exposure session during which they were presented with a neutral cue (water bottle) followed by a drug cue. Participants were instructed to look at, hold and sniff the water bottle, and take a drink of the water. Subsequently, participants were presented with paraphernalia associated with intranasal drug use (drug cue). They were asked to watch while a research nurse pulled out a wallet which contained a glycine packet filled with lactose powder and a straw, opened the packet and allowed the content to settle in the middle of the paper, took out the straw and cut it. The nurse would then instruct the participant to hold the straw and the powder packet for 30–60 seconds. Neutral cues always preceded drug cues to prevent carry-over effects from the active condition (drug cue) to the control condition (neutral cue). The cue exposure procedure was used to determine whether the study medication would affect reactivity to drug-related cues (Preller et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2012; Zijlstra et al., 2009).

2.3.5. Progressive Ratio Choice Session (Day 5):

After the cue exposure session on Fridays, participants were given the opportunity to self-administer drug and/or money using a progressive ratio (PR) choice procedure. This self-administration task included 10 trials during each of which participants could choose between 1/10th of the dose of oxycodone they had sampled in the morning (1 mg) or 1/10th of the money they had sampled ($1). In order to earn the chosen dose or money, participants had to respond via finger presses on a computer mouse. The progressive-ratio value increased independently each time drug or money was selected, starting with 25 responses in the first trial, followed by 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1,600, 3,200, 6,400, and 12,800. Participants received whatever fraction of the money and/or the oxycodone dose they had earned after they completed the task or stopped responding, respectively.

2.4. Physiological Parameters, Subjective Effects and Performance Tasks

Participants were monitored throughout all laboratory sessions, and subjective, performance, and physiological effects were measured using various scales and tasks. Subjective, performance, and physiological effects measured during the choice sessions on Days 1–4 as well as during the PR choice session on Day 5 were not statistically analyzed as the frequency of drug choices differed between participants and different participants self-administered different amounts of drug, respectively.

Pupil diameter (miosis) was measured under ambient light conditions as a physiological indicator of μ-agonist effects. Other physiological measures included heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, arterial oxygen saturation, end tidal CO2, and respiration (breaths per minute). In addition, body weight was measured at admission, and once per week. During the cue exposure session, galvanic skin response (GSR), skin temperature, and heart rate were assessed immediately before and after neutral and drug cue presentation as indicators of autonomic arousal (Mendes, 2009).

Subjective effects were measured using the Drug Effects Questionnaire (DEQ; Foltin and Fischman, 1991), the SOWS (Handelsman et al., 1987), and Visual Analog Scales (VAS) assessing mood as well as craving (for alcohol, cocaine, heroin, and tobacco; Comer et al., 1999). In addition, participants’ cognitive performance was assessed using the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST; McLeod et al., 1982) and the Divided Attention Task (DAT; Miller et al., 1988).

2.5. Drugs

Active lorcaserin (Belviq®) tablets (10 mg) were purchased from Eisai Inc. and blinded through over-encapsulation by the NYSPI investigational pharmacy. Each dose consisted of one capsule of active drug with lactose filler or lactose-only placebo and was administered to participants twice daily on the inpatient unit at 8 am and 8 pm.

Active oxycodone powder was obtained from KVK-Tech Inc. PBO oxycodone doses consisted of lactose monohydrate powder, purchased from Letco Medical. All IN doses were insufflated through a plastic straw within 5–10 seconds. A relatively low dose of oxycodone (10 mg IN) was administered at each single dosing opportunity in order to avoid possible over-intoxication if participants chose to self-administer drug on each of the 5 daily choice opportunities on Days 2–4 (and 4 choice opportunities on Day 1). All study drug blinding and packaging was performed by the NYSPI pharmacy.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

The primary statistical analyses were comparisons of acute drug effects on Day 1 after the first dose of PBO or active oxycodone in the PBO and active lorcaserin condition. The primary measures were: 1) drug-taking behavior measured by average percentage of drug choices during Choice Sessions and PR breakpoint values generated during PR Choice Sessions; 2) positive subjective responses measured by visual analogue scales during sample sessions; and 3) withdrawal measured by the SOWS questionnaire. A-priori power analyses were conducted using nQuery Advisor®, Statistical Solutions. A total sample size of 12 completers was deemed to provide ≥80% power to detect a 26% difference in average percentage of drug choices, a 500-point difference in progressive ratio breakpoint values, a 20-mm difference in positive subjective effects, e.g. “Liking” on a 100-mm VAS scale, and a 10.6-point difference in withdrawal, e.g. SOWS sum score (Comer et al., 2002, 2005).

Primary measures were analyzed using repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with planned contrasts with medication condition (PBO lorcaserin vs active lorcaserin) as the first factor. In case the assumption of sphericity was violated, P values were adjusted using the Huynh–Feldt correction. The time course data for average percentage of drug choices across the 4 Choice days were analyzed within each arm of the study and treated as repeated measures. Differences in choice as a function of self-administered dose (PBO oxycodone vs active oxycodone) were evaluated under each medication condition (PBO lorcaserin vs active lorcaserin). To control the false discovery rate due to the multiple comparisons, we used the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure with the critical value for a false discovery rate of 0.25. Accordingly, P values < 0.01 were used to indicate statistical significance, and values between .01 and .05 to indicate theoretical trends. All data analyses were performed using SuperANOVA (Gagnon et al., 1990).

2.7. IRB Approval

The NYSPI Institutional Review Board approved this study.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

A total of 18 volunteers were enrolled in the study. Three participants dropped voluntarily: two of those no longer wanted to be on the inpatient unit and one complained of withdrawal symptoms. Another three participants were discontinued by the investigators: two of those were non-compliant with the inpatient unit policies and one exhibited possible delusions and mild paranoia. While the latter may have been related to pre-existing paranoia not detected during screening, it cannot be ruled out that the study medication exacerbated the symptoms. Of the twelve completers, eleven were male; five were Caucasian, three were African American, two identified as Hispanic/Latino, and two were multiracial. The completers were on average 43.8 years of age (SEM = 2.7), had 11.3 years of education (SEM = 5.1), and had used heroin for an average of 17.4 years (SEM = 3.2) with a use of between two and ten bags per day in the past 30 days before enrollment in the study (average amount of $/day spent on heroin: 55.8, SEM = 6.0). All completers reported that they had used heroin daily in the last 30 days prior to study start. Three reported using prescription opioids between 1x/month to daily in addition to heroin. Other substances used included stimulants (n = 6; 1x/month to 2x/week), sedatives (n = 3; 2x/year to 2x/month), marijuana (n = 5; 4x/year to daily), and alcohol (n = 6; 1x/month to 3x/week). Ten completers were daily tobacco smokers (1–30 cigarettes/day).

3.2. Reinforcing Effects

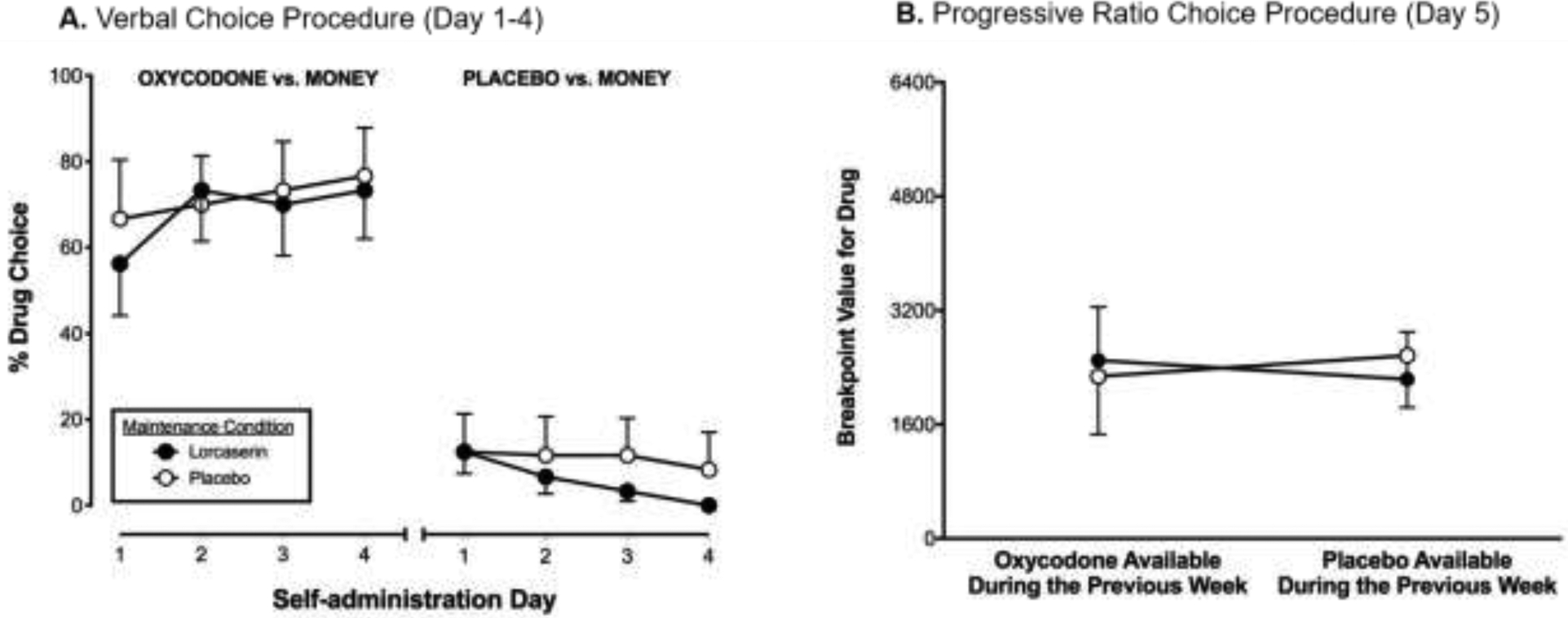

During the verbal choice self-administration procedure (Days 1–4), oxycodone was self-administered significantly more often than placebo (PBO Oxycodone vs Active Oxycodone: F(1,10) = 42.9, p<0.0001). However, the percentage of oxycodone choices did not differ as a function of lorcaserin condition (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Panel A: Drug (oxycodone or placebo) versus money ($10) self-administration in the active lorcaserin (10 mg BID; closed circles) versus the placebo lorcaserin (0 mg BID; open circles) condition assessed using a verbal choice procedure during Days 1–4. Panel B: Oxycodone (10 mg) self-administration using a progressive-ratio procedure (Day 5) in the active lorcaserin (10 mg BID; closed circles) versus the placebo lorcaserin (0 mg BID; open circles) condition following 4 days of access to placebo oxycodone or active oxycodone.

Under the PR schedule of reinforcement (oxycodone vs money available) on Day 5, robust drug breakpoints (>1600 responses) were observed under all conditions tested. The reinforcing effects of oxycodone did not vary as a function of the availability of oxycodone on the preceding 4 days, or as a function of lorcaserin condition (Figure 1B).

3.3. Subjective Effects

The subjective effects of oxycodone were measured before (−30 min pre-dose baseline) and after (5, 15, 30, and 45 minutes post-dose) the experimenter-administered dose of oxycodone or placebo on Day 1. No bad effects were reported for oxycodone or placebo, and lorcaserin did not alter this response. Placebo was liked less than oxycodone [PBO Oxycodone versus Active Oxycodone: F(1,10) = 8.3, p≤0.01], whereas oxycodone produced more good effects than placebo [F(1,10) = 9.4, p≤0.01], and participants reported a stronger drug effect after oxycodone compared to placebo [F(1,10) = 12.7, p<0.001] as well as a greater desire to take oxycodone again [F(1,10) = 15.9, p<0.001; DEQ ratings Table 2].

Table 2.

Subjective drug effects (DEQ and VAS), opiate withdrawal symptoms (SOWS), cognitive performance (DSST), divided attention (DAT), and physiological parameters after administration of active oxycodone (10 mg) or placebo oxycodone (0 mg) in the active lorcaserin (10 mg BID) versus the placebo lorcaserin (0 mg BID) condition. Values represent the mean effect after administration of the first (sample) dose of oxycodone or placebo (measured 5, 15, 30, and 45 minutes post-dose) on Day 1.

| Placebo Lorcaserin | Active Lorcaserin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Oxycodone (Mean, SEM) | Placebo (Mean, SEM) | Oxycodone (Mean, SEM) | Placebo (Mean, SEM) | Lorcaserin Dose (p-value) | Oxycodone Dose (p-value) | Lorcaserin x Oxycodone (p-value) | |

| DEQ | ||||||||

| Bad | 0.04 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | |

| Good | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.27 | 0.01* | 0.72 | |

| Like | −0.2 (0.3) | −1.8 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.3) | −1.8 (0.3) | 0.34 | 0.01* | 0.34 | |

| Strong | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.30 | 0.00* | 0.93 | |

| Take again | 1.1 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.43 | 0.00* | 0.28 | |

| VAS - Mood | ||||||||

| Alert | 33.4 (4.2) | 31.1 (5.1) | 39.0 (4.7) | 23.3 (4.2) | 0.85 | 0.15 | 0.22 | |

| Anxious | 26.1 (4.5) | 16.9 (3.6) | 34.0 (5.5) | 30.1 (5.0) | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.65 | |

| Bad Effect | 3.3 (1.8) | 1.0 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.1) | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.26 | |

| Depressed | 19.5 (4.7) | 9.7 (3.4) | 7.6 (2.1) | 8.5 (2.4) | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.38 | |

| Energetic | 14.2 (3.3) | 9.9 (3.2) | 18.5 (3.2) | 9.8 (3.0) | 0.44 | 0.18 | 0.68 | |

| Good Effect | 6.4 (1.6) | 0.8 (0.2) | 6.4 (1.8) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.97 | 0.03° | 0.97 | |

| Gooseflesh | 18.3 (4.6) | 6.4 (1.9) | 14.5 (4.1) | 17.8 (4.8) | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.18 | |

| High | 3.9 (1.1) | 0.7 (0.2) | 5.0 (1.5) | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.70 | 0.07 | 0.59 | |

| High Quality | 9.4 (2.7) | 5.0 (2.1) | 5.5 (1.6) | 2.5 (1.2) | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.73 | |

| I Would Pay ($) | 1.4 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.2) | 0.69 | 0.04° | 0.61 | |

| Irritable | 25.4 (4.4) | 24.2 (4.9) | 21.8 (4.7) | 21.3 (4.2) | 0.21 | 0.86 | 0.93 | |

| Like | 8.4 (2.2) | 2.8 (1.3) | 8.2 (2.0) | 2.5 (1.2) | 0.87 | 0.02° | 0.98 | |

| Mellow | 24.6 (3.7) | 17.8 (3.4) | 16.5 (3.2) | 10.9 (2.8) | 0.20 | 0.02° | 0.81 | |

| Muscle Pain | 11.4 (3.6) | 13.1 (3.5) | 17.8 (4.3) | 21.1 (4.2) | 0.17 | 0.76 | 0.87 | |

| Nauseated | 4.6 (1.8) | 1.4 (0.5) | 8.5 (3.5) | 6.8 (2.8) | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.33 | |

| Potent | 7.0 (2.1) | 2.8 (1.3) | 4.7 (1.6) | 2.7 (1.2) | 0.45 | 0.04° | 0.47 | |

| Restless | 4.9 (1.8) | 1.1 (0.4) | 4.1 (1.2) | 1.3 (0.4) | 0.80 | 0.04° | 0.65 | |

| Sedated | 4.9 (1.8) | 1.1 (0.4) | 3.7 (1.2) | 4.7 (1.8) | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.18 | |

| Sleepy | 16.3 (4.0) | 18.6 (4.1) | 5.6 (1.9) | 14.4 (3.5) | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.35 | |

| Social | 20.1 (3.3) | 12.2 (3.1) | 17.0 (2.6) | 12.2 (2.9) | 0.68 | 0.07 | 0.68 | |

| Stimulated | 9.2 (2.7) | 7.8 (3.1) | 5.1 (1.3) | 6.1 (2.6) | 0.43 | 0.96 | 0.61 | |

| Talkative | 20.1 (3.7) | 14.4 (3.6) | 13.5 (2.4) | 9.2 (2.6) | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.82 | |

| VAS - Craving | ||||||||

| Want Alcohol | 14.9 (3.7) | 11.2 (3.6) | 9.1 (2.6) | 13.8 (3.9) | 0.33 | 0.86 | 0.10 | |

| Want Cocaine | 4.8 (1.7) | 5.2 (1.9) | 4.1 (1.5) | 4.6 (1.4) | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.99 | |

| Want Heroin | 61.7 (5.2) | 73.7 (4.8) | 78.3 (4.5) | 70.5 (4.8) | 0.37 | 0.70 | 0.05° | |

| Want Tobacco | 53.5 (5.7) | 49.0 (5.9) | 47.5 (5.8) | 48.5 (5.6) | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.10 | |

| SOWS | ||||||||

| Sum | 10.8 (3.3) | 6.8 (1.9) | 12.7 (4.3) | 9.8 (3.5) | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.77 | |

| DAT | ||||||||

| # False Alarms | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | |

| # Hits | 19.1 (0.2) | 18.8 (0.2) | 19.2 (0.1) | 18.7 (0.2) | 1.00 | 0.05° | 0.42 | |

| # Misses | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.67 | 0.09 | 0.29 | |

| Maximum Speed | 4.8 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.6) | 4.4 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.5) | 0.66 | 0.32 | 0.90 | |

| Mean Hit Latency | 74.6 (7.0) | 76.4 (6.0) | 70.1 (5.6) | 76.9 (5.0) | 0.73 | 0.47 | 0.68 | |

| Tracking Distance | 5378.6 (2912.0) | 3571.0 (3071.3) | 5993.9 (2550.6) | 3650.7 (3335.3) | 0.91 | 0.49 | 0.93 | |

| DSST | ||||||||

| Total Attempted | 62.2 (3.5) | 65.8 (4.7) | 53.8 (3.6) | 57.6 (3.9) | 0.04° | 0.35 | 0.98 | |

| Total Correct | 57.4 (4.1) | 61.8 (5.0) | 51.6 (3.3) | 55.0 (3.7) | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.90 | |

| Physiological Parameters | ||||||||

| Heart Rate (beats/min) | 86.2 (0.8) | 87.1 (0.8) | 85.1 (0.9) | 83.5 (0.8) | 0.35 | 0.78 | 0.43 | |

| Pupil Diameter (mm) | 4.1 (0.1) | 4.3 (0.1) | 3.7 (0.1) | 4.3 (0.1) | 0.25 | 0.00* | 0.03° | |

| Arterial Oxygen Saturation (% SpO2) | 98.2 (0.1) | 98.1 (0.1) | 98.3 (0.1) | 98.2 (0.1) | 0.63 | 0.64 | 1.00 | |

| Diastolic Pressure | 82.0 (0.9) | 82.6 (0.8) | 76.2 (1.0) | 77.6 (1.1) | 0.00* | 0.58 | 0.79 | |

| Systolic Pressure | 131.52 (1.5) | 130.6 (1.3) | 121.9 (1.4) | 125.7 (1.2) | 0.01* | 0.50 | 0.18 | |

p<0.05,

p<0.01

Divided Attention Task; DEQ: Drug Effects Questionnaire; DSST: Digit Symbol Substitution Test; SOWS: Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale; VAS: Visual Analogue Scales

The main effect of lorcaserin was not significant for any of the DEQ ratings nor was there a lorcaserin x oxycodone dose interaction (DEQ ratings Table 2). With regard to VAS ratings, oxycodone had a trend to produce small increases in ratings of Good Effect [PBO Oxycodone versus Active Oxycodone: F(1,10) = 5.9, p<0.05], Liking [F(1,10) = 7.8, p<0.05], Mellow [F(1,10) = 8.1, p<0.05], Potent [F(1,10) = 5.2, p<0.05], and Restless [F(1,10) = 5.7, p<0.05], and participants indicated that they would pay more for it than placebo [F(1,10) = 5.6, p<0.05; VAS-Mood ratings Table 2]. These effects were unaltered by lorcaserin. In addition, withdrawal symptoms measured with the SOWS did not differ significantly between study conditions (Table 2).

3.4. Craving

VAS ratings of wanting alcohol and cocaine were generally low whereas wanting tobacco was rated as medium to high (Table 2). Wanting heroin was rated consistently high, and lorcaserin had a trend to increase VAS ratings of wanting heroin when oxycodone was available [interaction of lorcaserin condition x test drug (PBO Oxycodone vs Active Oxycodone): F(1,8) = 4.9, p≤0.05; Table 2].

3.5. Response to Drug Cues

Assessment of autonomic arousal during the cue exposure session revealed that peak heart rate values had a trend to being lower in the lorcaserin condition (M = 135.7, SEM = 5.7) compared to the placebo condition (M = 152.5, SEM = 4.8; PBO Lorcaserin vs Active Lorcaserin: F(1,10) = 4.7, p<0.05). This effect was not altered by type of cue (Neutral Cue vs Drug Cue) or by oxycodone availability in the days prior to the session. Neither peak nor trough GSR and skin temperature were significantly altered by any of the study conditions.

3.6. Adverse Events, Physiological and Cognitive Effects

AEs assessed with the SAFTEE were minimal, both in the PBO and the active lorcaserin condition (see Table 3 for details on AEs). Participants’ body weights increased by 2 kg from baseline (measured at admission: M = 88.2 kg, SEM = 4.4) to Week 3 (first testing week) independent of the condition participants were first randomized to (placebo condition: M = 90.2 kg, SEM = 4.4, Baseline vs PBO Lorcaserin: p<0.05; lorcaserin condition: M = 90.5 kg, SEM = 4.2, Baseline vs Active Lorcaserin: p<0.01) and remained stable thereafter.

Table 3.

Adverse events assessed with the Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Events (SAFTEE)

| Adverse Effects | Placebo Lorcaserin | Active Lorcaserin |

|---|---|---|

| n subjects (%) | n subjects (%) | |

| Backache | 2 (17) | 1 (8) |

| Bloody Mucus | 1 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Chills | 2 (17) | 3 (25) |

| Congestion | 1 (8) | 1 (8) |

| Constipation | 1 (8) | 2 (17) |

| Diarrhea | 3 (25) | 4 (33) |

| Fatigue | 3 (25) | 3 (25) |

| Fever | 1 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Foot Pain | 1 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Gas | 1 (8) | 1 (8) |

| GI Upset | 0 (0) | 3 (25) |

| Headache | 4 (33) | 4 (33) |

| Hot Flashes | 2 (17) | 1 (8) |

| Insomnia | 3 (25) | 3 (25) |

| Muscle Aches | 2 (17) | 3 (25) |

| Neck Pain | 1 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 8 (67) | 4 (33) |

| Runny Nose | 2 (17) | 2 (17) |

| Sneezing | 2 (17) | 1 (8) |

| Sore Throat | 1 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Tooth Pain | 2 (17) | 1 (8) |

| Tremor | 1 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Watering Eyes | 0 (0) | 1 (8) |

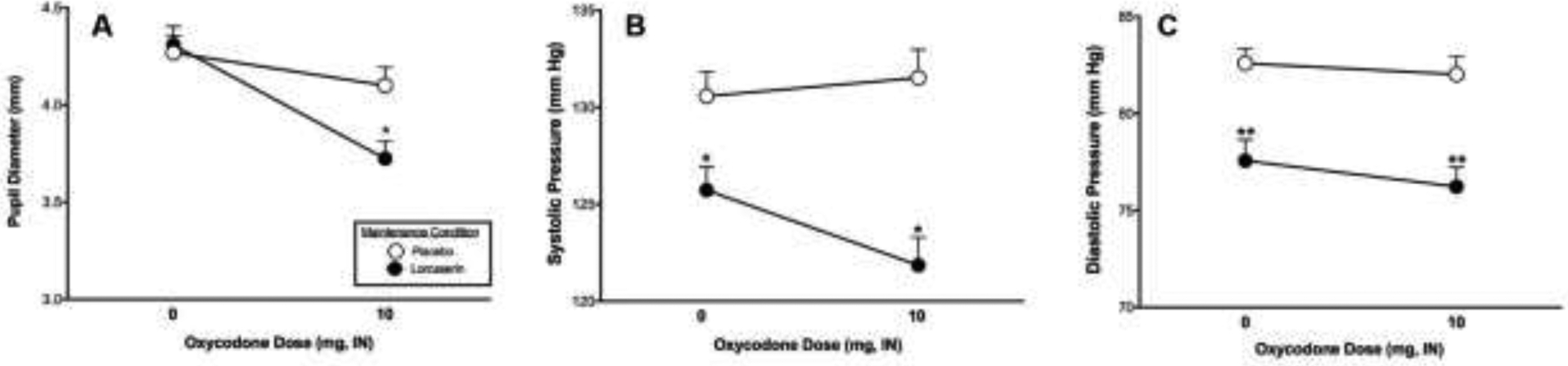

Physiological effects reported below refer to means across the session on Day 1 (measured 5, 15, 30, and 45 minutes post-dose). We chose to use means across the session to reduce variability due to measurement artifacts (e.g., due to movement). Oxycodone significantly decreased pupil diameter [PBO Oxycodone vs Active Oxycodone: F(1,10) = 14.0, p<0.01], and lorcaserin had a trend to accentuate that effect [interaction of lorcaserin condition x test drug (PBO Oxycodone vs Active Oxycodone): F(1,8) = 6.1, p <0.05; Figure 2A]. In addition, lorcaserin significantly reduced systolic pressure [PBO Lorcaserin vs Active Lorcaserin: F(1,10) = 12.1, p<0.01; Figure 2B] and diastolic pressure [F(1) = 24.1, p<0.001; Figure 2C]. While the effect on systolic pressure appears more distinct when oxycodone was available, there was no significant interaction between lorcaserin and oxycodone. Lorcaserin had no effect on heart rate, respiratory rate, O2 saturation, or end tidal CO2 (see Table 2 for detailed results on physiological effects).

Figure 2.

Mean pupil diameter (panel A), mean systolic pressure (panel B) and mean diastolic pressure (panel C) after administration of placebo oxycodone (0 mg) or active oxycodone (10 mg) on the sample session days (Day 1) in the active lorcaserin (10 mg BID; closed circles) versus the placebo lorcaserin (0 mg BID; open circles) condition. PBO lorcaserin vs active lorcaserin: *p<0.01, **p<0.001

On the cognitive performance tasks, participants had a trend to make fewer attempts on the DSST in the active lorcaserin condition compared to placebo [F(1,10) = 4.3, p<0.05] but the total number of correct responses was unaffected (Table 2). Lorcaserin did not affect performance on the divided attention task (DAT) but participants had a trend of more “hits” in the active oxycodone condition compared to placebo [F(1,10) = 4.1, p≤0.05, Table 2].

4. Discussion

The current study was designed to evaluate the ability of lorcaserin to alter the abuse liability of oxycodone as measured by subjective and reinforcing effects. Under our experimental conditions, oxycodone increased participants’ ratings of good drug effects and drug liking (DEQ and VAS) and was self-administered significantly more than placebo. While lorcaserin was well tolerated, with minimal side effects and no medically significant AEs among completers, it slightly slowed DSST performance. In our study, lorcaserin had no effect on participants’ body weight which is likely due to the fact that participants were receiving regular meals, which is not always the case for them when they are not in the hospital. However, we did not detect any reliable decreases following stabilization on 10mg lorcaserin BID in oxycodone self-administration or positive subjective effects, despite having adequate statistical power (≥80%) to detect clinically meaningful differences in the main outcome variables (percentage of drug choices and progressive ratio breakpoint values, positive subjective responses, and withdrawal) between the PBO and active lorcaserin condition. Of note, our cue reactivity assay was not sensitive as type of cue (neutral cue vs drug cue) did not have an effect on physiological response. Therefore, it was not possible to determine if the study medication decreased reactivity to the opioid-related cue.

Our findings are inconsistent with the preclinical literature showing decreases in oxycodone self-administration (Neelakantan et al., 2017), and reductions in self-administration of other abused substances including cocaine, alcohol, and nicotine (Briggs et al., 2016; Collins et al., 2015; Cousins et al., 2014; Gerak et al., 2016; Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016; Higgins et al., 2012; Levin et al., 2011; Rezvani et al., 2014; Zeeb et al., 2015). Studies in rodents have shown that lorcaserin decreases opioid self-administration only at doses well above those used clinically for the treatment of obesity (Neelakantan et al., 2017; Panlilio et al., 2017); however, these high doses of lorcaserin also decreased food self-administration in rats (Panlilio et al., 2017; Neelakantan et al., 2017 did not test the effects of lorcaserin on food self-administration). Studies in non-human primates show mixed results concerning the effects of lorcaserin on drug- versus food-maintained responding. Lorcaserin dose-dependently decreased cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys, but the same doses also decreased food-maintained responding (Banks and Negus, 2017). While one study showed that lorcaserin maintenance dose-dependently decreased the reinforcing effects of heroin but not food (Kohut and Bergman, 2018), another study reported that lorcaserin significantly increased heroin choice by rhesus monkeys trained in a drug versus food choice procedure (Townsend et al., under review). The different findings on expression of behavioral selectivity in these studies might have been influenced by experimental variables independent of the candidate medication, such as heroin dose available during self-administration sessions. Kohut and Bergman (2018) found that 1 mg/kg/day lorcaserin reduced responding maintained by low unit doses of heroin (0.32–3.2 μg/kg) but not higher doses; similarly, Townsend et al. (under review) found a non-significant trend for 0.32 mg/kg/hour lorcaserin to decrease self-administration of 10 μg/kg heroin. However, in their study lorcaserin failed to promote behavioral reallocation away from heroin and towards the food reinforcer at any heroin dose, suggesting that the behavioral selectivity of lorcaserin is not sufficient to provide effective decreases in opioid reinforcement.

This is the first human laboratory study examining the effects of lorcaserin on oxycodone self-administration and subjective responses. However, similar to our findings with lorcaserin in combination with oxycodone, a recent study in humans found that a single 10 mg dose of lorcaserin had no effect on cocaine versus money choice but it enhanced some positive subjective effects of cocaine (Pirtle et al., 2019). The authors argue that lorcaserin administered at a relatively low dose may have modestly increased accumbal dopaminergic tone, augmenting the positive subjective effects of low-dose cocaine.

Besides a trend to accentuate oxycodone-induced miosis, the physiological effect that was most robustly altered by lorcaserin in the current study was a reduction in systolic and diastolic pressure. While statistically significant, this reduction was not of clinical concern. Similar effects on blood pressure have been reported in patients using lorcaserin for weight management, with no effect on heart rate (Chan et al., 2013). Given that our participants did not have high blood pressure at study enrolment, another possible explanation for this effect is that it represents a dysregulation of the norepinephrine (NE) system. Our participants were detoxified from opioids before they were stabilized on lorcaserin, and it has been shown that rapid opioid detoxification is associated with increases in plasma catecholamines (epinephrine and NE). In addition, peak increases in plasma NE correlates with an increase in sympathetic activity (McDonald et al., 1999). On the other hand, there is evidence that 5-HT2c receptor activation decreases NE release (Done and Sharp, 1992; Millan et al., 1998), which may have caused the reduction in blood pressure under lorcaserin maintenance we observed in our study. While “autonomic instability” due to serotonin syndrome is listed as a possible side effect of lorcaserin, serotonin syndrome is extremely rare and is probably not responsible for the mild pressor effects of lorcaserin observed in our study.

The current well-controlled experimental design was intended to capture various phenomena related to the abuse liability of opioids including cue reactivity and responding to drug after periods of brief abstinence. As a necessary consequence of our choice of design, the subjective effects that were observed were small. Namely, we were only able to obtain group means on the effects of the first sample dose of oxycodone. Because all subsequent doses were self-administered, the amount of drug given was variable (i.e., some participants did not choose to take oxycodone on some of the choice opportunities). Nevertheless, the overall pattern of effects suggests that a lorcaserin dose of 10 mg BID is not effective in altering oxycodone-induced positive subjective effects. In contrast to the small subjective responses observed in the present study, the reinforcing effects of oxycodone were robust and lorcaserin had no effect on this endpoint.

It must be noted that we used the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate, which is less sensitive than the Bonferroni procedure. While methods such as the Bonferroni correction control well the chance of a Type I error, they are likely to lead to Type II errors. In addition, 11 of the 12 subjects completing the study were male, which prevented an examination of sex-related differences. However, preclinical studies indicate that the pharmacokinetic properties of lorcaserin are independent of sex (Higgins et al., 2019; Shram et al., 2011). Another limitation of the present study design was the use of only a single active dose of lorcaserin and a single active dose of oxycodone. Previous studies in non-human primates suggest that lorcaserin – even if given at very high doses – may not be effective in suppressing self-administration of higher opioid doses (e.g., Kohut and Bergman, 2018; Townsend et al., under review). Nonetheless, given that this is the first study in humans, future research could explore a wider dose range of both lorcaserin and oxycodone in order to obtain a more complete picture of its utility as a treatment for OUD.

Highlights.

Lorcaserin did not alter oxycodone self-administration

Lorcaserin had a trend to increase “wanting heroin” when oxycodone was available

Lorcaserin had a trend to accentuate oxycodone-induced miosis

Lorcaserin at a dose of 10 mg BID did not decrease the abuse liability of oxycodone

Role of funding source

Research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under the Award Number U54 DA037842-01. The manuscript content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors declare there are no competing financial interests or potential conflicts of interest in relation to the research described.

References

- Ahrnsbrak R, Bose J, Hedden S, Lipari R, Park-Lee E, 2017. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Negus SS, 2017. Repeated 7-Day Treatment with the 5-HT2C Agonist Lorcaserin or the 5-HT2A Antagonist Pimavanserin Alone or in Combination Fails to Reduce Cocaine vs Food Choice in Male Rhesus Monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 1082–1092. 10.1038/npp.2016.259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs SA, Hall BJ, Wells C, Slade S, Jaskowski P, Morrison M, Rezvani AH, Rose JE, Levin ED, 2016. Dextromethorphan interactions with histaminergic and serotonergic treatments to reduce nicotine self-administration in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 142, 1–7. 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control, 2018. Drug Overdose Deaths [WWW Document]. URL https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html (accessed 3.7.19). [Google Scholar]

- Chan EW, He Y, Chui CSL, Wong AYS, Lau WCY, Wong ICK, 2013. Efficacy and safety of lorcaserin in obese adults: a meta-analysis of 1-year randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and narrative review on short-term RCTs. Obes. Rev 14, 383–392. 10.1111/obr.12015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Gerak LR, Javors MA, France CP, 2015. Lorcaserin Reduces the Discriminative Stimulus and Reinforcing Effects of Cocaine in Rhesus Monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 356, 85–95. 10.1124/jpet.115.228833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer S, Collins E, Kleber H, Nuwayser E, Kerrigan J, Fischman M, 2002. Depot naltrexone: long-lasting antagonism of the effects of heroin in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 159, 351–360. 10.1007/s002130100909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Collins ED, MacArthur RB, Fischman MW, 1999. Comparison of intravenous and intranasal heroin self-administration by morphine-maintained humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 143, 327–338. 10.1007/s002130050956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Sullivan MA, Yu E, Rothenberg JL, Kleber HD, Kampman K, Dackis C, O’Brien CP, 2006. Injectable, Sustained-Release Naltrexone for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63, 210 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Walker EA, Collins ED, 2005. Buprenorphine/naloxone reduces the reinforcing and subjective effects of heroin in heroin-dependent volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 181, 664–675. 10.1007/s00213-005-0023-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins V, Rose JE, Levin ED, 2014. IV nicotine self-administration in rats using a consummatory operant licking response: Sensitivity to serotonergic, glutaminergic and histaminergic drugs. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 54, 200–205. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KA, Anastasio NC, 2014. Serotonin at the nexus of impulsivity and cue reactivity in cocaine addiction. Neuropharmacology 76, 460–478. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFulio A, Everly JJ, Leoutsakos J-MS, Umbricht A, Fingerhood M, Bigelow GE, Silverman K, 2012. Employment-based reinforcement of adherence to an FDA approved extended release formulation of naltrexone in opioid-dependent adults: A randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 120, 48–54. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Done CJG, Sharp T, 1992. Evidence that 5-HT2 receptor activation decreases noradrenaline release in rat hippocampus in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol 107, 240–245. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14493.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everly JJ, DeFulio A, Koffarnus MN, Leoutsakos J-MS, Donlin WD, Aklin WM, Umbricht A, Fingerhood M, Bigelow GE, Silverman K, 2011. Employment-based reinforcement of adherence to depot naltrexone in unemployed opioid-dependent adults: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction 106, 1309–1318. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03400.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatseas M, Denis C, Massida Z, Verger M, Franques-Rénéric P, Auriacombe M, 2011. Cue-Induced Reactivity, Cortisol Response and Substance Use Outcome in Treated Heroin Dependent Individuals. Biol. Psychiatry 70, 720–727. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher P, 2002. Differential Effects of the 5-HT2A Receptor Antagonist M100,907 and the 5-HT2C Receptor Antagonist SB242,084 on Cocaine-induced Locomotor Activity, Cocaine Self-administration and Cocaine-induced Reinstatement of Responding. Neuropsychopharmacology. 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00342-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Rizos Z, Noble K, Soko AD, Silenieks LB, Lê AD, Higgins GA, 2012. Effects of the 5-HT2C receptor agonist Ro60–0175 and the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist M100907 on nicotine self-administration and reinstatement. Neuropharmacology 62, 2288–2298. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Fischman MW, 1991. Methods for the assessment of abuse liability of psychomotor stimulants and anorectic agents in humans. Addiction 86, 1633–1640. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01758.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon J, Roth J, Carroll M, Haycock K, Plamondon J, Feldman D, Simpson J, 1990. Superanova accessible general linear modeling. Yale J Biolo Med 63, 191–2. [Google Scholar]

- Gerak LR, Collins GT, France CP, 2016. Effects of Lorcaserin on Cocaine and Methamphetamine Self-Administration and Reinstatement of Responding Previously Maintained by Cocaine in Rhesus Monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 359, 383–391. 10.1124/jpet.116.236307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenway FL, Shanahan W, Fain R, Ma T, Rubino D, 2016. Safety and tolerability review of lorcaserin in clinical trials. Clin. Obes 6, 285–295. 10.1111/cob.12159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handelsman L, Cochrane KJ, Aronson MJ, Ness R, Rubinstein KJ, Kanof PD, 1987. Two New Rating Scales for Opiate Withdrawal. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 13, 293–308. 10.3109/00952998709001515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey-Lewis C, Li Z, Higgins GA, Fletcher PJ, 2016. The 5-HT 2C receptor agonist lorcaserin reduces cocaine self-administration, reinstatement of cocaine-seeking and cocaine induced locomotor activity. Neuropharmacology 101, 237–245. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Fletcher PJ, Shanahan WR, 2019. Lorcaserin: a review of its preclinical and clinical pharmacology and therapeutic potential. Pharmacol. Ther 107417 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Silenieks LB, Roßmann A, Rizos Z, Noble K, Soko AD, Fletcher PJ, 2012. The 5-HT2C Receptor Agonist Lorcaserin Reduces Nicotine Self-Administration, Discrimination, and Reinstatement: Relationship to Feeding Behavior and Impulse Control. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 1177–1191. 10.1038/npp.2011.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Cunningham KA, 2014. Serotonin 5-HT2 Receptor Interactions with Dopamine Function: Implications for Therapeutics in Cocaine Use Disorder. Pharmacol. Rev 67, 176–197. 10.1124/pr.114.009514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RE, 1992. A Controlled Trial of Buprenorphine Treatment for Opioid Dependence. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc 267, 2750 10.1001/jama.1992.03480200058024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RE, Chutuape MA, Strain EC, Walsh SL, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, 2000. A Comparison of Levomethadyl Acetate, Buprenorphine, and Methadone for Opioid Dependence. N. Engl. J. Med 343, 1290–1297. 10.1056/NEJM200011023431802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohut SJ, Bergman J, 2018. Lorcaserin decreases the reinforcing effects of heroin, but not food, in rhesus monkeys. Eur. J. Pharmacol 840, 28–32. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.09.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL, 2011. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 377, 1506–1513. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60358-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupitsky E, Zvartau E, Blokhina E, Verbitskaya E, Tsoy M, Wahlgren V, Burakov A, Masalov D, Romanova TN, Palatkin V, Tyurina A, Yaroslavtseva T, Sinha R, Kosten TR, 2013. Naltrexone with or without guanfacine for preventing relapse to opiate addiction in St.-Petersburg, Russia. Drug Alcohol Depend 132, 674–680. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupitsky E, Zvartau E, Blokhina E, Verbitskaya E, Wahlgren V, Tsoy-Podosenin M, Bushara N, Burakov A, Masalov D, Romanova T, Tyurina A, Palatkin V, Slavina T, Pecoraro A, Woody GE, 2012. Randomized Trial of Long-Acting Sustained-Release Naltrexone Implant vs Oral Naltrexone or Placebo for Preventing Relapse to Opioid Dependence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 69, 973 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.1a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Johnson JE, Slade S, Wells C, Cauley M, Petro A, Rose JE, 2011. Lorcaserin, a 5-HT2C Agonist, Decreases Nicotine Self-Administration in Female Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 338, 890–896. 10.1124/jpet.111.183525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine J, Schooler N, 1986. SAFTEE: a technique for the systematic assessment of side effects in clinical trials. Psychopharmacol. Bull 22, 343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling W, Wesson D, 2003. Clinical efficacy of buprenorphine: comparisons to methadone and placebo. Drug Alcohol Depend. 70, S49–S57. 10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00059-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marissen MAE, Franken IHA, Waters AJ, Blanken P, van den Brink W, Hendriks VM, 2006. Attentional bias predicts heroin relapse following treatment. Addiction 101, 1306–1312. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01498.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald T, Hoffman W, Berkowitz R, Cunningham F, Cooke B, 1999. Heart rate variability and plasma catecholamines in patients during opioid detoxification. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol 11, 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod DR, Griffiths RR, Bigelow GE, Yingling J, 1982. An automated version of the digit symbol substitution test (DSST). Behav. Res. Methods Instrum 14, 463–466. 10.3758/BF03203313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes WB, 2009. Assessing autonomic nervous system activity, in: Harmon-Jones E, Beer J (Eds.), Methods in Social Neuroscience. Guilford Press, New York, pp. 118–147. [Google Scholar]

- Millan M., Dekeyne A, Gobert A, 1998. Serotonin (5-HT)2C receptors tonically inhibit dopamine (DA) and noradrenaline (NA), but not 5-HT, release in the frontal cortex in vivo. Neuropharmacology 37, 953–955. 10.1016/S0028-3908(98)00078-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TP, Taylor JL, Tinklenberg JR, 1988. A Comparison of Assessment Techniques Measuring the Effects of Methylphenidate, Secobarbital, Diazepam and Diphenhydramine in Abstinent Alcoholics. Neuropsychobiology 19, 90–96. 10.1159/000118441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnane KS, Winschel J, Schmidt KT, Stewart LM, Rose SJ, Cheng K, Rice KC, Howell LL, 2013. Serotonin 2A Receptors Differentially Contribute to Abuse-Related Effects of Cocaine and Cocaine-Induced Nigrostriatal and Mesolimbic Dopamine Overflow in Nonhuman Primates. J. Neurosci 33, 13367–13374. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1437-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelakantan H, Holliday ED, Fox RG, Stutz SJ, Comer SD, Haney M, Anastasio NC, Moeller FG, Cunningham KA, 2017. Lorcaserin Suppresses Oxycodone Self-Administration and Relapse Vulnerability in Rats. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 8, 1065–1073. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nic Dhonnchadha BÁ, Fox RG, Stutz SJ, Rice KC, Cunningham KA, 2009. Blockade of the serotonin 5-ht2a receptor suppresses cue-evoked reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in a rat self-administration model. Behav. Neurosci 123, 382–396. 10.1037/a0014592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro SC, Luon D, Baker WL, 2013. Lorcaserin: a novel serotonin 2C agonist for the treatment of obesity. Curr. Med. Res. Opin 29, 839–848. 10.1185/03007995.2013.794776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Secci ME, Schindler CW, Bradberry CW, 2017. Choice between delayed food and immediate opioids in rats: treatment effects and individual differences. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 234, 3361–3373. 10.1007/s00213-017-4726-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirtle JL, Hickman MD, Boinpelly VC, Surineni K, Thakur HK, Grasing KW, 2019. The serotonin-2C agonist Lorcaserin delays intravenous choice and modifies the subjective and cardiovascular effects of cocaine: A randomized, controlled human laboratory study. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 180, 52–59. 10.1016/j.pbb.2019.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockros LA, Pentkowski NS, Swinford SE, Neisewander JL, 2011. Blockade of 5-HT2A receptors in the medial prefrontal cortex attenuates reinstatement of cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 213, 307–320. 10.1007/s00213-010-2071-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, Mann JJ, 2011. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial Validity and Internal Consistency Findings From Three Multisite Studies With Adolescents and Adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 168, 1266–1277. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preller KH, Wagner M, Sulzbach C, Hoenig K, Neubauer J, Franke PE, Petrovsky N, Frommann I, Rehme AK, Quednow BB, 2013. Sustained incentive value of heroin-related cues in short- and long-term abstinent heroin users. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 23, 1270–1279. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani AH, Cauley MC, Levin ED, 2014. Lorcaserin, a selective 5-HT 2C receptor agonist, decreases alcohol intake in female alcohol preferring rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 125, 8–14. 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S, Foote J, Aronsen D, Bukholt N, Highgate Q, Van de Wetering R, Webster J, 2016. Serotonin antagonists fail to alter MDMA self-administration in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 148, 38–45. 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan WR, Rose JE, Glicklich A, Stubbe S, Sanchez-Kam M, 2016. Lorcaserin for Smoking Cessation and Associated Weight Gain: A Randomized 12-Week Clinical Trial. Nicotine Tob. Res. ntw301 10.1093/ntr/ntw301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shram MJ, Schoedel KA, Bartlett C, Shazer RL, Anderson CM, Sellers EM, 2011. Evaluation of the Abuse Potential of Lorcaserin, a Serotonin 2C (5-HT2C) Receptor Agonist, in Recreational Polydrug Users. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 89, 683–692. 10.1038/clpt.2011.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyka M, Zingg C, Koller G, Kuefner H, 2008. Retention rate and substance use in methadone and buprenorphine maintenance therapy and predictors of outcome: results from a randomized study. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol 11 10.1017/S146114570700836X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen WJ, Grottick AJ, Menzaghi F, Reyes-Saldana H, Espitia S, Yuskin D, Whelan K, Martin M, Morgan M, Chen W, Al-Shamma H, Smith B, Chalmers D, Behan D, 2008. Lorcaserin, a Novel Selective Human 5-Hydroxytryptamine2C Agonist: in Vitro and in Vivo Pharmacological Characterization. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 325, 577–587. 10.1124/jpet.107.133348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend EA, Negus SS, Poklisa JL, Banks ML, under review Lorcaserin maintenance fails to attenuate heroin vs. food choice in rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, 2018. Medications for opioid use disorder: bridging the gap in care. Lancet 391, 285–287. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32893-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Pang G, Zhang Y-M, Li G, Xu S, Dong L, Stackman RW, Zhang G, 2015. Activation of serotonin 5-HT2C receptor suppresses behavioral sensitization and naloxone-precipitated withdrawal symptoms in heroin-treated mice. Neurosci. Lett 607, 23–28. 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeb FD, Higgins GA, Fletcher PJ, 2015. The Serotonin 2C Receptor Agonist Lorcaserin Attenuates Intracranial Self-Stimulation and Blocks the Reward-Enhancing Effects of Nicotine. ACS Chem. Neurosci 6, 1231–1240. 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Fan C, Du J, Jiang H, Chen H, Sun H, 2012. Cue-induced craving and physiological reactions in recently and long-abstinent heroin-dependent patients. Addict. Behav 37, 393–398. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zijlstra F, Veltman DJ, Booij J, van den Brink W, Franken IHA, 2009. Neurobiological substrates of cue-elicited craving and anhedonia in recently abstinent opioid-dependent males. Drug Alcohol Depend. 99, 183–192. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]