Abstract

Background

Research collaborations between non-Indigenous and Indigenous researchers primarily have been led by non-Indigenous researchers with privileged locations in university settings. Recognition of the importance of data sovereignty and control to enable Indigenous self-determination requires building data management and analysis capacities among Indigenous research partners. The Canadian Alliance for Healthy Hearts and Minds First Nations (CAHHM-FN) cohort study, a collaboration of 8 First Nations and researchers at 8 universities, convened a 3-day data management and analysis workshop.

Methods

Before the workshop, participating communities were asked to develop research questions of interest regarding data collected as part of CAHHM-FN and forward them to the coordinating team. An agenda was created, circulated, and modified on the basis of community feedback to plan the workshop. The CAHHM coordinating team, an Indigenous researcher, and a non-Indigenous biostatistician planned the workshop to strike balance among Indigenous protocols for engagement, theory concerning Indigenous approaches to statistical analysis, and applied data analysis training.

Results

Fifty participants and coordinating team members convened for the 3-day workshop (22 Indigenous and 28 non-Indigenous people from communities, professors, trainees, and staff). Topics included statistical literacy, hands-on data analysis, data security, and topics in Indigenous health research. Workshop evaluations indicated a high level of satisfaction and enthusiasm to hold similar future workshops.

Conclusions

The Indigenous data workshop was designed to increase capacity for data management and analysis by Indigenous community partners and develop new capacity for non-Indigenous partners and trainees. It achieved this, with enthusiasm from Indigenous community members to conduct future workshops.

Résumé

Contexte

Les activités de recherche collaboratives entre chercheurs non autochtones et chercheurs autochtones sont principalement menées par des chercheurs non autochtones jouissant de ressources universitaires. Il y a lieu de développer les capacités des partenaires de recherche autochtones en matière de gestion et d’analyse des données afin que soit reconnue l’importance de la souveraineté et du contrôle des données et permettre l’autodétermination des peuples autochtones. Un atelier de trois jours sur la gestion et l’analyse des données a été donc été organisé dans le cadre de l’étude de cohorte CAHHM-FN (Canadian Alliance for Healthy Hearts and Minds First Nations), fruit d’une collaboration entre huit communautés des Premières Nations et des chercheurs de huit universités.

Méthode

Avant l’atelier, on a demandé aux communautés participantes de préparer des questions de recherche d’intérêt au sujet des données recueillies dans le cadre de l’étude CAHHM-FN et d’en faire part à l’équipe de coordination de l’atelier. Un programme a été établi, diffusé et modifié en fonction des commentaires des communautés. L’équipe de coordination de l’étude CAHHM-FN, un chercheur autochtone et un biostatisticien non autochtone ont ensuite préparé un programme pour l’atelier de formation en visant à trouver un juste équilibre entre les protocoles autochtones de mobilisation, la théorie relative aux approches autochtones de l’analyse statistique et l’analyse de données appliquée.

Résultats

Cinquante participants et les membres de l’équipe de coordination se sont réunis pour l’atelier de trois jours (soit 22 Autochtones et 28 non-Autochtones membres des communautés, professeurs, stagiaires et employés de soutien). Les thèmes abordés comprenaient la littératie statistique, l’analyse de données pratique, la sécurité des données ainsi que certains sujets de recherche en santé des Autochtones. Les résultats des évaluations de l’atelier montrent que les participants étaient très satisfaits de leur expérience et enthousiastes à l’égard de futurs ateliers du même genre.

Conclusions

L’atelier sur les données autochtones avait pour objectifs d’améliorer les capacités des partenaires des communautés autochtones en matière de gestion et d’analyse de données et de former des partenaires et des stagiaires non autochtones. Ces objectifs ont été atteints, et les membres des communautés autochtones se sont montrés enthousiastes à l’égard de futurs ateliers.

The importance of fair data practices and data sovereignty is paramount for First Nations people in Canada.1, 2, 3 In some colonized states, a significant amount of academic research done by non-Indigenous peoples has caused harm to First Nations communities.4 Data collected on Indigenous peoples are commonly presented in a manner that emphasizes Indigenous peoples’ “difference, disparity, disadvantage, dysfunction, and deprivation” in relation to the non-Indigenous colonizer.3 These sorts of descriptions create narratives that serve to propagate negative stereotypes regarding Indigenous communities, and define—in the colonizer’s terms—who an Indigenous person is, who they should be, and who they cannot be in the dominant society.3

The 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples voiced this priority, describing “self-determination”—the right for Indigenous peoples to “freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development” as an essential right for Indigenous sovereignty.2 Self-determination includes the ability to collect data and pursue research questions that meet the needs of the Indigenous communities themselves, rather than the desires, ambitions, and liberal-thinking non-Indigenous researchers. Such racist and arrogant prejudice toward Indigenous peoples is perpetuated when their access to research data about themselves is restricted.5 Improved access to research methodologies, which allow Indigenous peoples and communities themselves to take control of their own research, is crucial to advance this effort.

The First Nations Information Governance Centre, a Canadian organization focused on First Nations data collection and sovereignty, reinforces the importance of self-determination and describes the importance of research done “by First Nations people, for First Nations people” to improve the lives of First Nations communities.6 As a framework to push toward First Nations data sovereignty, the First Nations Information Governance Centre recommends following the principles of Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP). Essentially, the OCAP principles assert that First Nations communities have the right to possess their own data as a community and that protocols must be in place to ensure that communities have sovereignty over their own information.1 If the research is being done by non-Indigenous researchers, capacity-building and creating strong and trusting relationships between researchers and First Nations communities are also extremely important.

The Canadian Alliance for Healthy Hearts and Minds First Nations (CAHHM-FN) cohort, which includes 8 First Nations from across the country, seeks to understand the burden of chronic disease risk factors and subclinical disease among a cross-section of First Nations adults living in reserve communities in Canada.7 CAHHM-FN has embraced the OCAP principles.1 CAHHM-FN was conducted between December 2013 and March 2018, and after data cleaning at the central coordinating site, datasets were ready for transfer back to communities, or if communities were not confident the data could be held securely in their community, they would be stewarded securely at the coordinating institution. As a step toward self-determination in research8 to help build capacity in data management, storage, security, and analysis among First Nations community members and their non-Indigenous allies in research, we convened a 3-day data management and analysis workshop planned and led by Indigenous and non-Indigenous health researchers with expertise in biostatistics and epidemiology.

Methods

Planning for the workshop began in 2018 when the CAHHM central coordinating office was preparing to transfer each of 8 community datasets back to the community from where the data were collected. Community representatives in the National First Nations Working Group (NFNWG) of CAHHM-FN raised several questions regarding data access, security, and identification of the most appropriate person in their community to access data for analyses. Further, the community-based Indigenous research associates who had collected the data expressed a strong interest in asking questions of the data and analyzing their own community data but were unsure of how to begin the process. Examples of the type of questions community members were interested in included understanding the impact of diabetes on future need for dialysis and using the food frequency questionnaire data to understand eating patterns. The NFNWG discussed holding a Data Management and Analysis workshop, and there was unanimous interest in doing so; the group then initiated a search for funding. The cost for flights, accommodations, and meals to bring 50 people together was estimated to be CAD $40,000. We did not seek research ethics board approval because this is a descriptive article regarding workshop planning and evaluation.9

Program planning and development of the final agenda

The NFNWG suggested that in addition to experienced statistical experts at the CAHHM coordinating centre, that an Indigenous facilitator with expertise in health research, biostatistics, and Indigenous methodologies be engaged to help with the planning stage and the workshop. We drafted an agenda and modified it after 3 planning teleconference calls. The main modifications included less emphasis on unidirectional classroom teaching and increased “hands-on” analysis of actual CAHHM-FN data, addition of co-facilitators, addition of student involvement, and introduction of cultural components, including an opening prayer and visit to the local Six Nations community for a traditional meal and entertainment. The final agenda is shown in Supplementary Appendix S1.

We created a practice data set from the entire cohort for the training sessions for 2 reasons: First, so that each community would be working with the same dataset during the hands-on training, and second because community participants preferred to work with real data rather than simulated (artificially created) data. To preserve anonymity, the data from the entire cohort were collapsed into a single dataset (ie, ignoring the community they belonged to), and 3 randomly selected hypothetical communities of 125 participants each were created. The communities were arbitrarily named “A,” “B,” and “C.” This would permit participants to “play” with real data at the workshop with “communities” of size similar to their actual cohorts, but not permit any meaningful interpretation of the results because they did not pertain to any specific First Nations community.

A number of statistical software packages were pilot tested before the workshop by the biostatistician and student facilitators, and 2 open source options included Epi-info (https://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/index.html) and JASP.10 We decided to use JASP because it was open source, easy to use, and had excellent data visualization options. We provided each community with a laptop during the hands-on training, preloaded with JASP and the training dataset.

During the workshop, we provided each participant with a glossary of commonly used statistical terms, which we reviewed in detail to ensure participants all had a baseline understanding of key concepts (Supplementary Appendix S2). We also broke up the monotony of defining terms with interactive lectures that showcased ongoing Indigenous research connected in one way or to the CAHHM-FN study. This included presentations on Indigenous Biobanking, the Silent Genomes Project,11 Cardiovascular Health in First Nations, and Data Security in local community settings. In addition, a traditional Haudenosaunee Diet Research Project led by Six Nations was an example of an indigenous-led intervention involving Six Nation’s CAHHM-FN participants and provided the background for a visit by the workshop participants to Six Nations to have a traditional Haudenosaunee meal and entertainment experience.

Content of statistical modules

There were 2 statistical training modules. The first one focused on the principles for descriptive analyses and included such essential underlying statistical concepts as embracing variation and the role of sampling and chance in understanding the uncertainties in quantitative information. This module incorporated how “statistical descriptive analyses” are essentially “getting to know us,” the theme for the workshop. The second module focused on “understanding relationships” and “statistical inferential analyses” principles such as ruling out the role of chance and understanding the sources of variation that may explain observed relationships. In addition, we provided each participant with a glossary of commonly used statistical terms (Supplementary Appendix S2).

Coordinating centre support staff

Four biostatisticians, 1 information and communications technology personnel, and 5 McMaster University students served as the support personnel for the community groups working on the dataset. Because the support personnel were all non-Indigenous, they attended a 3-hour sensitivity training session in advance of the workshop using content with demonstrated impact among health professionals. The content areas focused on terminology, a historical overview of colonialism, current inequities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, OCAP principles, ethical considerations, and the blending of Indigenous and Western worldviews/approaches to scientific discovery. This session included a lecture-based and interactive component (eg, gallery walks, discussions, self-directed research time, question/answer session). One CAHHM staff member and a PhD student, both non-Indigenous, facilitated the session. Instruction was rooted in examples and practical hands-on training over theoretical foundations. At the end of each session module, the facilitator led an informal roundtable discussion with the group of student participants and the students openly reflected on the material covered, their thoughts on the learnings, the positives and negatives about how the material was delivered, and what specifics can be improved for future training sessions. In addition, a health research methodology graduate student provided a 2-hour JASP training session for all support staff and student facilitators. Here, the students learned how to use the key features of the software and became familiar with data analysis procedures so that they could support the community representatives during the actual workshop.

Workshop evaluation

During the workshop, we sought verbal feedback from participants. At the conclusion of the 3-day workshop, we invited verbal feedback in the wrap-up discussion and requested participants to complete an anonymous formal evaluation (Supplementary Appendix S3 shows the evaluation form).

Fundraising

We obtained funding contributions from multiple sources, including researchers in Indigenous health, universities, research institutes, foundations, and industry partners. We planned further cost-sharing with another Indigenous research study,11 which involved bringing all of the same CAHHM-FN communities together.

Results

The participants in the workshop were highly engaged in both the theoretical and hands-on components (Table 1). The facilitators worked to ensure that topics basic to statistical literacy, such as probability, statistical testing, sampling strategies, and possible sources of bias, were fun and interactive including the use of slides, flip-charts, and hands-on activities (eg, use of M&M candies to demonstrate the Central Limit Theorem).

Table 1.

Participants in the Indigenous Data Management and Analysis Workshop

| Indigenous participants | Non-Indigenous participants | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAHHM communities | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| Others (keynote speakers, Silent Genomes team, graduate students, research assistant) | 10 | 4 | 14 |

| Local community researchers | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Central study staff/investigators | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Student facilitators | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Total | 23 | 27 | 50 |

CAHHM, Canadian Alliance for Healthy Hearts and Minds.

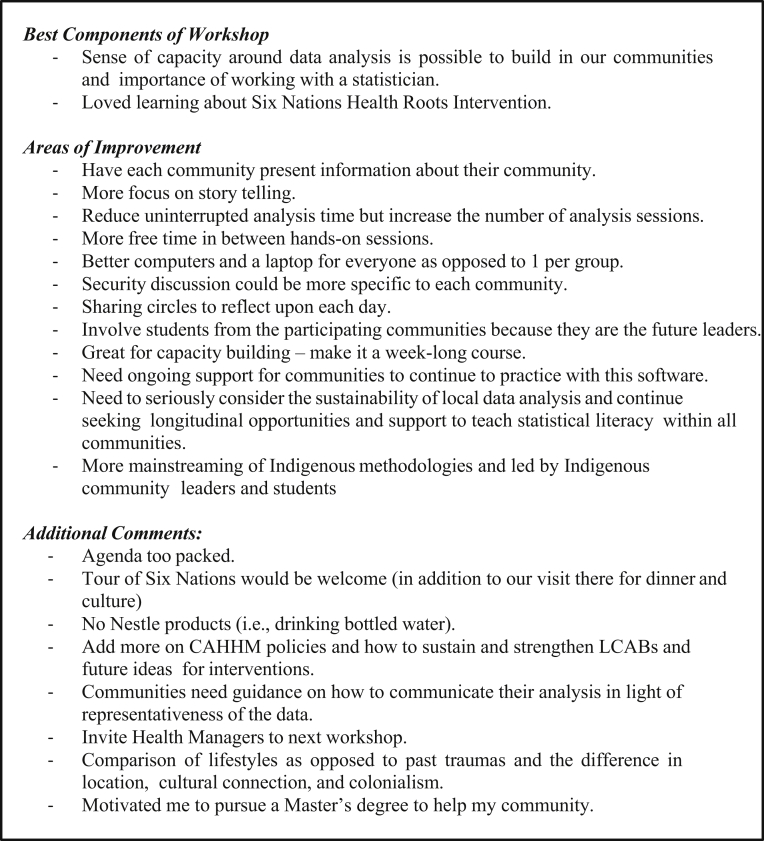

Seventy-seven percent of respondents (20/26) indicated the statistical literacy section was of large or very large value. At the same time, critical written feedback collected in the evaluations identified areas for future improvement, such as “Statistical language and concepts were too technical; and introduction of concepts such as logistic regression and odds ratios was too much detail for the introductory workshop and may be better suited for more advanced training” (Boxed Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Key feedback.

For the “hands-on” training, each community team of Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers sat together to work. Each team received a “variable guide” explaining how the variable was coded. A student facilitator worked with each community team. The goal for each team was to “fill in the blanks” using a template from a manuscript under preparation, with descriptive statistics missing (eg, proportions, means) (Supplementary Appendix S4). Biostatisticians from the coordinating centre, supported by student facilitators, guided the teams with input from the workshop co-facilitators.

Evaluations of this component indicated a high level of satisfaction with the hands-on applications and data analysis, with 69% of participants reporting that the “hands-on” component of the workshop was of large or very large value (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results from quantitative evaluation

| Category | Percentage of responders reporting workshop of large or very large value (N = 26 respondents) |

|---|---|

| Overall Workshop Satisfaction | 85% |

| Statistical Literacy | 77% |

| Formulating a “Research Question” | 77% |

| Hands-on Workshop | 69% |

| Instructional Lectures | |

| CAHHM-FN Results Review | 77% |

| Healthy Roots | 81% |

| Security of Data | 77% |

| BioBanking in First Nations | 65% |

| Silent Genomes | 65% |

| Air Pollution Proposal | 62% |

| Indigenous Cardiovascular Research | 65% |

| Decision-Making Processes on New Proposals CAHHM-FN | 38% |

CAHHM-FN, Canadian Alliance for Healthy Hearts and Minds First Nations.

In addition to the theoretical and hands-on components of the workshop, researchers working in Indigenous health and an information security expert delivered “keynote lectures.” These lectures were well received by the group, with more than two-thirds of participants rating these of large or very large value (Table 2).

Through formal and informal feedback channels, participants suggested that we could improve future workshops by (1) giving more free time to participants to interact with each other as the agenda was thought to be too packed, with lots of sitting and too few breaks; (2) incorporating sharing circles at the end of each day to share key learning concepts and perceptions of the workshops by participants;12 (3) increasing emphasis on story telling within science;13,14 (4) maintaining the discussion of data analysis and statistics beyond the workshop through regular teleconference calls; and (5) providing statistical support as needed (Fig. 1).

Participants were uniformly positive regarding the interaction with the student facilitators who guided participants in use of the JASP statistical program. One participant wrote “Learning how to navigate on the computer laptop helped me to become more knowledgeable with observing data. I felt more confident when my screen had matched the teacher’s screen. I was very impressed with the student helper’s knowledge of technology and data management to assist me.”

Some participants brought to our attention that the foods provided at the break included certain manufacturers that infringed on territory rights of a First Nation in southern Ontario, and they recommended plastic water bottles not be purchased from this company. In general, use of more environmentally friendly plates and cutlery were recommended. The attendees universally agreed that a summary video would be a useful method of sharing their workshop experience to help raise awareness in their communities and in academic institutions, and they also expressed strong or very strong interest for future workshops.

Discussion

The responses from participants regarding the Indigenous Data Management and Analysis Workshop were positive, and the workshop was deemed to be a success, as measured by participants’ enthusiasm and engagement. More than 75% of participants thought that the workshop was of large value, and 77% thought they improved their own statistical literacy and ability to formulate a research question. There was unanimous recognition by workshop attendees of the importance of statistical rigor in their scholarship. (See summary video of workshop Video 1

; view video online).

; view video online).

Indigenous data sovereignty was built into the mission of the CAHHM-FN cohort, and this workshop reinforced the governance framework of the CAHHM-FN. The model includes First Nations data ownership, control, access, and possession—as recommended by the OCAP principles—and promotes Indigenous self-determination and autonomy in research through building data-analysis capacities with members of the partner communities. Participants were keen to develop their own statistical skills and move from being “data collectors” to “data stewards and users,” with the goal of using this information to help shape community policies and priority planning as well as to plan future Indigenous-led research studies and interventions. We did not identify a similar Indigenous Data Management and Analysis Workshop in the published literature. However, we identified a National Institutes of Health initiative in the United States that supports Native investigators by sponsoring health research and interventions in tribal settings, and includes a National Institutes of Health–funded Native Investigator Development Program, which trains junior Native scholars in rigorous research methods so they can successfully compete for independent research funding.15,16 In addition, the SING summer workshop in the United States, Canada, and New Zealand is an annual 1-week intensive workshop designed to build Indigenous capacity and scientific literacy by training undergraduate and graduate students, postdoctoral, and community fellows in the basics of genomics, bioinformatics, and Indigenous and decolonial bioethics.17

The pairing of non-Indigenous students and project team members with Indigenous community members was a step toward a greater mutual understanding of each other’s lived experiences, skills, and knowledge frameworks. All non-Indigenous participants underwent cultural safety training to prevent the potential discord and disconnect that can occur in a colonial teaching environment.18 The student facilitators reported that the training modules they completed in preparation for the workshop enhanced their learning experiences and contributed positively to their confidence in serving lead roles during the "All About Us" workshop. Students also conveyed that the real-world examples and supplementary readings/resources helped to strengthen their understanding of the Indigenous perspectives. In future workshops, we will aim to engage Indigenous undergraduate and graduate students to serve as community facilitators where possible. In addition, we will integrate more Indigenous methodology, such as learning through storytelling within science, use of sharing circles, and connection with Elders and Knowledge Keepers, for context and interpretation of the quantitative data in future workshops.19

Funding challenges are always present. We had not built this workshop into our original grant application and our funds were, therefore, exhausted. To hold this first workshop, we relied on contributions from researchers through their peer-reviewed funds, associates with Research Chairs and Mentorship Networks, McMaster University Faculty of Health Sciences and the President’s office, the Silent Genomes project funded through Genome Canada, the Six Nations Health Foundation, and an in-kind donation from the Six Nations Health Services. In addition, we received an unrestricted funding donation from a pharmaceutical company, although in our postworkshop discussion, workshop participants recommended formally adopting continuing medical education guidelines for private industry funding for future workshops20 and avoiding industry partnerships that had clear conflicts with First Nations people’s values.

We encourage researchers who are planning large collaborative projects with Indigenous communities to embed similar data management and analysis workshops into their funding proposals from the outset. To do this well, sponsors of Indigenous research should expect the costs of conducting research to be substantially higher than the costs of conducting similar research among non-Indigenous groups where United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNRIP) and OCAP do not come into play.

Furthermore, we learned through this experience in planning of an Indigenous-led or Indigenous focused meeting, organizers should think in line with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to avoid using service providers who have infringed upon territory rights of First Nations people who promote a respect for the land and sustainability.

Conclusions

The “All About Us” Indigenous Data Management and Analysis Workshop was highly valued by participants as a step toward Indigenous data sovereignty and capacity building in research. We encourage funders and other researchers to develop similar models of capacity building in this area of health research studies with the understanding that there is no “one size fits all” approach.

Writing Group

Sonia Anand, Shrikant I. Bangdiwala, Heather Castleden, Albertha Darlene Davis,* Dipika Desai, Russell de Souza, Sujane Kandasamy, Diana Lewis,* and Anand Sergeant.

*Identifies as Indigenous.

The full list of Canadian Alliance for Healthy Hearts and Minds First Nations Cohort Research Team (CAHHM-FN) Communities and Researchers is available at https://cahhm.mcmaster.ca/?page_id=6113.

Funding Sources

Acknowledgement and funders of the workshop:

Six Nations Health Foundation

McMaster University, Faculty of Health Sciences

McMaster University, President’s Office

McMaster University, Department Medicine

Canadian Institutes for Health Research (Sonia Anand Foundation Grant; Gita Wahi Network Environments for Indigenous Health Research)

Silent Genomes Project

Bayer Pharmaceuticals

Disclosures

There are no conflicts of interest reported by the writing group.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement: This article has adhered to the ethical principles of workshop planning and evaluation.

Corresponding author: Dr Sonia S. Anand, Population Health Research Institute, a Joint Institute of McMaster University and Hamilton Health Sciences, 237 Barton St East, Hamilton, Ontario L8L 2X2, Canada. E-mail: anands@mcmaster.ca.

See page 287 for disclosure information.

To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit CJC Open at https://www.cjcopen.ca and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjco.2019.09.002.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Appendix S1, S2 and S3

The “All About Us” Video includes highlights from the workshop showing the hands-on learning, student facilitators, oral presentations, and a visit to Six Nations community for a traditional meal and arts evening. Available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1--JutXY9eHyfiiwwEkhca_HnnLyvI3Mz/view?usp=drivesdk.

References

- 1.First Nations Information Governance Centre The First Nations Principles of OCAP 2019. http://fnigc.ca/ocapr.html Available at: Accessed March 15, 2018.

- 2.United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. A/RES/61/295. New York, NY: UN General Assembly, 2007.

- 3.Walter M., Suina M. Indigenous data, Indigenous methodologies and Indigenous data sovereignty. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2019;22:233–243. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perbal L. Vol. 27. 2013. The ‘Warrior Gene' and the Mãori People: the responsibility of the geneticists bioethics; pp. 382–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith L.T. Zed Books Ltd; London, UK: 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. [Google Scholar]

- 6.First Nations Information Governance Centre About FNIGC 2019. http://fnigc.ca/about-fnigc/frequently-asked-questions.html Available at: Accessed June 1, 2019.

- 7.Anand S.S., Abonyi S., Arbour L. Canadian Alliance for Healthy Hearts and Minds: First Nations Cohort Study Rationale and Design. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2018;12:55–64. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2018.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walter M. Left Coast Press; Walnut Creek, CA: 2013. Indigenous Statistics: A Quantitative Research Methodology. [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Leeuw S., Cameron E.S., Greenwood M.L. Participatory and community-based research, Indigenous geographies, and the spaces of friendship: a critical engagement. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien. 2012;56:180–194. [Google Scholar]

- 10.JASP Team. JASP (Version 0.9) [Computer Software]. 2018. Available at: https://jasp-stats.org. Accessed June 1, 2019.

- 11.Arbour L, Caron N, Reading J, Wasserman W, Regier D. Silent genomes. Reducing health care disparities and improving diagnostic success for children with genetic diseases from Indigenous populations. Available at: https://www.uvic.ca/medsci/assets/docs/arbour/Silent%20Genomes%20for%20webpage.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- 12.Hart M.A. Sharing circles: utilizing traditional practice methods for teaching, helping and supporting. In: O'Meara S., West D.A., editors. From Our Eyes: Learning From Indigenous Peoples. Garamond Press; Toronto: 1996. pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernández-Llamazares Á., Cabeza M. Rediscovering the potential of Indigenous storytelling for conservation practice. Conservation Letters. 2018;11 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sium A., Ritskes E. Speaking truth to power: Indigenous storytelling as an act of living resistance. Decolonization: indigeneity, education & society. 2013;2(1):I–X. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jernigan V.B.B., Peercy M., Branam D. Beyond health equity: achieving wellness within American Indian and Alaska Native communities. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(S3):S376–S379. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manson S.M., Goins R.T., Buchwald D.S. The Native Investigator Development Program: Increasing the Presence of American Indian and Alaska Native Scientists in Aging-Related Research. J Appl Gerontol. 2006;25(1_suppl) 105S-30S. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Indigenous STS Summer Internship for Indigenous Peoples in Genomics Canada (SING Canada) Alberta: Indigenous STS (Science, Technology, and Society); 2019. http://indigenoussts.com/sing-canada/ Available at: Accessed September 5, 2019.

- 18.Baba L. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health; Prince George, BC: 2013. Cultural Safety in First Nations, Inuit and Métis Public Health: Environmental Scan of Cultural Competency and Safety in Education, Training and Health Services. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyett S., Marjerrison S., Gabel C. Improving health research among indigenous peoples in Canada. CMAJ. 2018;190:E616–E621. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.171538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis D.A. CME and the pharmaceutical industry: two worlds, three views, four steps. CMAJ. 2004;171:149–150. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Appendix S1, S2 and S3

The “All About Us” Video includes highlights from the workshop showing the hands-on learning, student facilitators, oral presentations, and a visit to Six Nations community for a traditional meal and arts evening. Available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1--JutXY9eHyfiiwwEkhca_HnnLyvI3Mz/view?usp=drivesdk.