Abstract

Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) belong to a large family comprising 22 FGF polypeptides that are widely expressed in tissues. Most of the FGFs can be secreted and involved in the regulation of skeletal muscle function and structure. However, the role of fasting on FGF expression pattern in skeletal muscles remains unknown. In this study, we combined bioinformatics analysis and in vivo studies to explore the effect of 24-h fasting on the expression of Fgfs in slow-twitch soleus and fast-twitch tibialis anterior (TA) muscle from male and female C57BL/6 mice. We found that fasting significantly affected the expression of many Fgfs in mouse skeletal muscle. Furthermore, skeletal muscle fibre type and sex also influenced Fgf expression and response to fasting. We observed that in both male and female mice fasting reduced Fgf6 and Fgf11 in the TA muscle rather than the soleus. Moreover, fasting reduced Fgf8 expression in the soleus and TA muscles in female mice rather than in male mice. Fasting also increased Fgf21 expression in female soleus muscle and female and male plasma. Fasting reduced Fgf2 and Fgf18 expression levels without fibre-type and sex-dependent effects in mice. We further found that fasting decreased the expression of an FGF activation marker gene—Flrt2 in the TA muscle but not in the soleus muscle in both male and female mice. This study revealed the expression profile of Fgfs in different skeletal muscle fibre types and different sexes and provides clues to the interaction between the skeletal muscle and other organs, which deserves future investigations.

Keywords: Fasting, Fibroblast growth factor, Skeletal muscle, Fibre type, Sex, Mice

Introduction

Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) are a large family of polypeptide growth factors that are widely expressed in organisms ranging from nematodes to humans [1]. FGFs regulate complex biological functions in vivo and in vitro, including embryogenesis, mitogenesis, cellular migration and differentiation, angiogenesis, wound healing, skeleton growth, energy homeostasis, metabolism, and adipogenesis [2].

In human, the FGF family contains 22 FGF proteins, four FGF receptors (FGFR1-4) [2], and one receptor (FGFR5) lacking an intracellular kinase domain [3]. There is no human FGF15 gene; the gene orthologous to mouse FGF15 is FGF19 [4]. FGFs are classified into three major groups [5]: Canonical FGFs (FGF1-FGF10, FGF16-FGF18, FGF20 and FGF22) can be secreted from cells. Intracrine FGFs (FGF11-FGF14) are not secreted but participate in intracellular processes independent of FGFRs [6]. Hormone-like FGFs (FGF15/19, FGF21 and FGF23) have systemic effects [1, 7].

Studies show that fasting has several healthy benefits [8], such as increasing longevity, alleviating obesity and other non-infectious diseases [9], and anti-tumour [10]. However, fasting can also lead to muscle wasting and cause life-threatening problems [11]. These effects are closely related to the physiological response of the skeletal muscle to fasting. The skeletal muscle is not only a motor organ, but also a metabolic organ, which stores most of the body’s energy and regulates systemic metabolism. During fasting or energy deficits, the skeletal muscles would adjust energy demands and preserve energy homeostasis [12]. Ours and other studies found that growth factors coordinate metabolic reprogramming in muscle during fasting [13].

FGFs have long been implicated in skeletal muscle structure and function [14]. Several FGFs have been proved to function as myokines, such as FGF2 [15] and FgF21 [15, 16]. A myokine is a protein or peptide that it is derived and secreted from the skeletal muscle and performs biological functions in an endocrine or paracrine manner [17]. FGFs were initially associated with myogenesis [18]. FGFs, FGFRs and their co-receptor (heparin or heparan sulfate) are expressed in a time- and space-dependent manner during all stages of skeletal development [19]. FGF15/19 was found to ameliorate skeletal muscle atrophy [20]. Studies reported that Fgf21 expressed by muscle controls muscle mass [16] and increases insulin sensitivity [21].

The skeletal muscles of mammals are composed of multiple muscle fibre types, including oxidative slow-twitch (type I), mixed oxidative-glycolytic fast-twitch (type IIa) and glycolytic fast-twitch (type IIb) myofibres, which differ in their metabolic properties [22]. The soleus muscle has a higher proportion of type I muscle fibres than that of many other muscles [23], and the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle has significantly more type IIb fibres [24]. Studies report that fasting influences FGF expression in the skeletal muscle. It was observed that fasting and metabolic disorders induced FGF21 release from muscles [16], whereas the muscle Fgf6 mRNA levels were not significantly affected by animal feeding status [25]. In addition, biological sexes have different responses to muscle health, largely due to the significant variety of general muscle fibre type, satellite cell activation and proliferation, anabolic and catabolic factors, and hormonal interactions between males and females [26]. Our previous study found that Fgf15 expression is higher in the skeletal muscle of female mice than that of male mice. Fasting reduces Fgf15 expression in female muscles but had no effect on male muscles [27].

However, the mechanisms by which fasting influences the expression pattern of skeletal muscle FGFs is still unknown. In this study, we investigated the expression of all the 22 Fgfs in slow-twitch soleus and fast-twitch tibialis anterior (TA) muscle, to explore the influence of muscle fibre types and sexes on Fgf expression during fasting in female and male mice.

Materials and methods

Animals

This study and all the procedures using animals were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Female and male C57BL/6 mice (20–22 g), obtained from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China), were used in this study. Mice were housed in environmentally controlled conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle at a temperature of 22 ± 3 °C and humidity of 55 ± 5%. Mice were provided free access to food and water for 7 days before the experiment.

Animal fasting procedure

After being housed for 7 days, female and male C57BL/6 mice were randomly allocated either to a fed group (Fed) or a fasted group (Fast) with six mice in each group. The fasted mice were placed in new cages without providing any food in the cage at 9 A.M. After fasting for 24 h [16, 28, 29], the Fed and Fast mice were anaesthetised with isoflurane, blood samples were collected via the abdominal vein and the indicated skeletal muscles from different anatomical positions were quickly removed and frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction and further experiments.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR

Total RNA was isolated from ~ 50 mg muscles or a whole piece of the soleus muscle by homogenisation in Trizol Isolation Reagent (Invitrogen, USA), and then purified with Direct-zol RNA Kits (cat. no. R2052, ZYMO search, USA) as previously described [27, 30]. Reverse transcription was performed using 1 μg of total RNA with a reverse transcription reaction mix that contained Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA) and Oligo-dT17 as primers. Specific mRNA content was determined using AceQ qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (cat. no. Q111-03, Vazyme, Biotech) on a CFX-96 Real-time PCR System (Bio-Rad, USA) with gene-specific primer pairs (Table 1). The total reaction volume was 10 μl. The results were quantified after normalisation with TATA-box binding protein (Tbp) [31, 32].

Table 1.

Primers used for real-time PCR

| Pairs | Genes | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mouse Fgf1 5′ | CCCTGACCGAGAGGTTCAAC |

| Mouse Fgf1 3′ | GTCCCTTGTCCCATCCACG | |

| 2 | Mouse Fgf2 5′ | GCGACCCACACGTCAAACTA |

| Mouse Fgf2 3′ | TCCCTTGATAGACACAACTCCTC | |

| 3 | Mouse Fgf3 5′ | TACAACGCAGAGTGTGAGTTTG |

| Mouse Fgf3 3′ | CACCGACACGTACCAAGGTC | |

| 4 | Mouse Fgf4 5′ | TACCCCGGTATGTTCATGGC |

| Mouse Fgf4 3′ | TTACCTTCATGGTAGGCGACA | |

| 5 | Mouse Fgf5 5′ | AAGTAGCGCGACGTTTTCTTC |

| Mouse Fgf5 3′ | CTGGAAACTGCTATGTTCCGAG | |

| 6 | Mouse Fgf6 5′ | CAGGCTCTCGTCTTCTTAGGC |

| Mouse Fgf6 3′ | AATAGCCGCTTTCCCAATTCA | |

| 7 | Mouse Fgf7 5′ | CTCTACAGATCATGCTTCCACC |

| Mouse Fgf7 3′ | ACAGAACAGTCTTCTCACCCT | |

| 8 | Mouse Fgf8 5′ | AGAGCCTGGTGACGGATCA |

| Mouse Fgf8 3′ | CTTCCAAAAGTATCGGTCTCCAC | |

| 9 | Mouse Fgf9 5′ | ATGGCTCCCTTAGGTGAAGTT |

| Mouse Fgf9 3′ | TCCGCCTGAGAATCCCCTTT | |

| 10 | Mouse Fgf10 5′ | TTTGGTGTCTTCGTTCCCTGT |

| Mouse Fgf10 3′ | TAGCTCCGCACATGCCTTC | |

| 11 | Mouse Fgf11 5′ | TAGCCTGATCCGACAGAAGC |

| Mouse Fgf11 3′ | GGCAGAACAGTTTGGTGACG | |

| 12 | Mouse Fgf12 5′ | CAGGCCGTGCATGGTTTCTA |

| Mouse Fgf12 3′ | TCGTGTAGTGATGGTTCTCTGT | |

| 13 | Mouse Fgf13 5′ | CTCATCCGGCAAAAGAGACAA |

| Mouse Fgf13 3′ | TTGGAGCCAAAGAGTTTGACC | |

| 14 | Mouse Fgf14 5′ | CCCCAGCTCAAGGGCATAG |

| Mouse Fgf14 3′ | TGATGGGTAGAGGTAACCTTCTC | |

| 15 | Mouse Fgf15 5′ | ATGGCGAGAAAGTGGAACGG |

| Mouse Fgf15 3′ | CTGACACAGACTGGGATTGCT | |

| 16 | Mouse Fgf16 5′ | GTGTTTTCCGGGAACAGTTTGA |

| Mouse Fgf16 3′ | GGTGAGCCGTCTTTATTCAGG | |

| 17 | Mouse Fgf17 5′ | GGCAGAGAGCGAGAAGTACAT |

| Mouse Fgf17 3′ | CGGTGAACACGCAGTCTTTG | |

| 18 | Mouse Fgf18 5′ | CCTGCACTTGCCTGTGTTTAC |

| Mouse Fgf18 3′ | TGCTTCCGACTCACATCATCT | |

| 19 | Mouse Fgf20 5′ | GGTGGGGTCGCACTTCTTG |

| Mouse Fgf20 3′ | GATACCGAAGAGACTGTGATCCT | |

| 20 | Mouse Fgf21 5′ | CTGCTGGGGGTCTACCAAG |

| Mouse Fgf21 3′ | CTGCGCCTACCACTGTTCC | |

| 21 | Mouse Fgf22 5′ | CCAGGACAGTATAGTGGAGATCC |

| Mouse Fgf22 3′ | AGTAGACCCGCGACCCATAG | |

| 22 | Mouse Fgf23 5′ | ATGCTAGGGACCTGCCTTAGA |

| Mouse Fgf23 3′ | AGCCAAGCAATGGGGAAGTG | |

| 23 | Mouse Flrt2 5′ | ATGGGCCTACAGACTACAAAGT |

| Mouse Flrt2 3′ | CAGCGGCATACACTAGGGC | |

| 24 | Mouse Flrt3 5′ | CCTCATCGGGACTAAAATTGGG |

| Mouse Flrt3 3′ | GCAAGTTCTTCAAATCGGAAGGA | |

| 25 | Mouse Tbp 5′ | ACCCTTCACCAATGACTCCTATG |

| Mouse Tbp 3′ | ATGATGACTGCAGCAAATCGC |

Measurement of FGFs in mice plasma

Plasma concentrations of FGF15, FGF21, FGF23, and FLRT2 were quantified using the ELISA kits (cat.no. CSB-EL522052MO, CUSABIO; cat.no.ab212160, Abcam; cat.no.ab213863, Abcam; cat.no. JL38212, Shanghai Jianglai Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, respectively.

GEO data acquisition and FGF expression analysis

We first performed human tissue-specific FGF expression analysis in non-diseased tissues using Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) expression dataset (https://gtexportal.org/home/multiGeneQueryPage), which is a comprehensive public resource to study tissue-specific gene expression and regulation. For each gene, expression values were normalised across samples using an inverse normal transform. Next, we explored Fgf expression in the skeletal muscle in mice using the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. The GEO is a public functional genomics data repository that provides a multimodal data repository and retrieval system for microarray and next-generation sequencing gene expression profiles. This study queried and downloaded the relevant studies from the GEO website (The Gene Expression Omnibus, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/) [33]. We identified a suitable dataset comparing expression in the skeletal muscles of fed and fasting mice, which is an RNA sequencing dataset (accession number GSE107787). In this dataset study, male C57BL/6 mice at 8 weeks of age were randomly divided into an ad libitum fed group (n = 18) or a 24-h fasted group (n = 18). For complete experimental details, please refer to a previous publication [29].

Statistical analysis

Differences between the groups were tested using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA. Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, USA). Data are presented as means ± S.E.M. The significance level was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Bioinformatic analysis found FGFs expressed differently and could be influenced diversely by fasting

We compared expression levels of human FGFs in the skeletal muscle with that in other tissues. Bioinformatic results from GTEx dataset show that FGFs were expressed divergently in different tissues. Different FGFs demonstrated distinctive expression in the human skeletal muscle, of which FGF13, FGF11, FGF6, FGF2 and FGF7 had the top five expression levels (Fig. 1a). Next, fasting-induced expressions of Fgfs in the skeletal muscle of male mice were analysed using a dataset from NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). In this dataset, mice were fasted for 24 h and the gastrocnemius skeletal muscles were taken for RNA sequencing experiment (accession numbers GSE107787) [29]. According to the analysis of the dataset results, the top five Fgf genes with the highest expression levels in mice gastrocnemius were Fgf13, Fgf1, Fgf6, Fgf11 and Fgf7. Meanwhile, in the case of canonical FGFs, fasting induced Fgf20 and Fgf22 expression by 13.2- and 2.5-fold and reduced Fgf2, Fgf5, Fgf6, Fgf7, Fgf9, Fgf10 and Fgf18 expression by 2.1-, 8.5-, 6.0-, 2.1-, 1.4-, 1.6- and 4.6-fold, respectively. Regarding intracellular FGFs, fasting reduced Fgf11, Fgf13 expression by 2.5- and 1.5-fold. The expression of an endocrine FGF—Fgf23—was reduced by 6.4-fold (Fig. 1b). However, data on Fgf15 was not obtained from the RNA sequencing results.

Fig. 1.

Bioinformatics analysis demonstrates that fasting influences FGF expression in skeletal muscles. a Human FGF expression levels in skeletal muscles compared with those in other tissues. Left: The expression of FGFs in various tissues. Right: Heatmap of FGF expression in skeletal muscles. b Expression of Fgfs in muscle from 24-h fasted mice. Left: Heatmap of basal expression of Fgfs in skeletal muscles. Right: Expression of Fgfs in gastrocnemius muscle. Data represent means ± S.E.M, n = 18; biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test

Differential expression of Fgfs in male and female mice according to fibre type of the skeletal muscle

Our previous study showed that slow-twitch soleus and fast-twitch TA have different myokine expressions [27]. In this study, we found that the muscle fibre types also influenced expressions of Fgfs. The results showed that in male C57BL/6 mice, expressions of canonical Fgf1–Fgf7, Fgf9, Fgf10, Fgf16, Fgf17 and Fgf20 in the soleus muscle were 5.3-, 3.0-, 34.4-, 37.8-, 23.4-, 3.7-, 8.0-, 10.3-, 36.3-, 38.0-, 41.9- and 112.4-fold higher compared with those in the TA muscle, respectively. Intracellular Fgf12 and Fgf13 expressed in the soleus muscle were 2.8- and 29.8-fold higher than those in the TA muscle, while Fgf11 in the TA muscle was 21.2-fold higher than that in the soleus muscle. Expressions of endocrine Fgf15, Fgf21 and Fgf23 in the soleus muscle were 59.0-, 65.1- and 39.7-fold higher than those of the TA muscle (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Fgf expression levels in different muscle fibre types of male and female C57BL/6 mice. a Basal Fgf expression level in male mice. Left: Heatmap of basal Fgf expression in the TA and soleus muscles. Right: Comparison of Fgf expression levels between the soleus and TA muscles. b Basal Fgf expression level in female mice. Left: Heatmap of basal Fgf expression in the TA and soleus muscles. Right: Comparison of Fgf expression levels between the soleus and TA muscles. Data represent means ± S.E.M, n = 6; biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test

In female C57BL/6 mice, canonical Fgf1-Fgf7, Fgf9, Fgf10, Fgf16, Fgf17 and Fgf20 had 2.2-, 2.6-, 4.9-, 8.2-, 5.2-, 3.3-, 2.9-, 3.7-, 6.3-, 6.8-, 9.4- and 6.6-fold higher expression in the soleus than those in the TA muscle, respectively, which is consistent with male mice. Fgf8 and Fgf11 in the TA muscle were 2.1- and 43.5-fold higher than those in the soleus muscle. Intracellular Fgf12 was expressed in the soleus muscle as 2.1-fold as much as that in the TA muscle, while Fgf11 in the TA muscle was 43.5-fold higher than that in the soleus muscle. Expressions of endocrine Fgf15, Fgf21 and Fgf23 in the soleus muscle were 6.5-, 4.8- and 6.0-fold higher than those in the TA muscle, respectively (Fig. 2b).

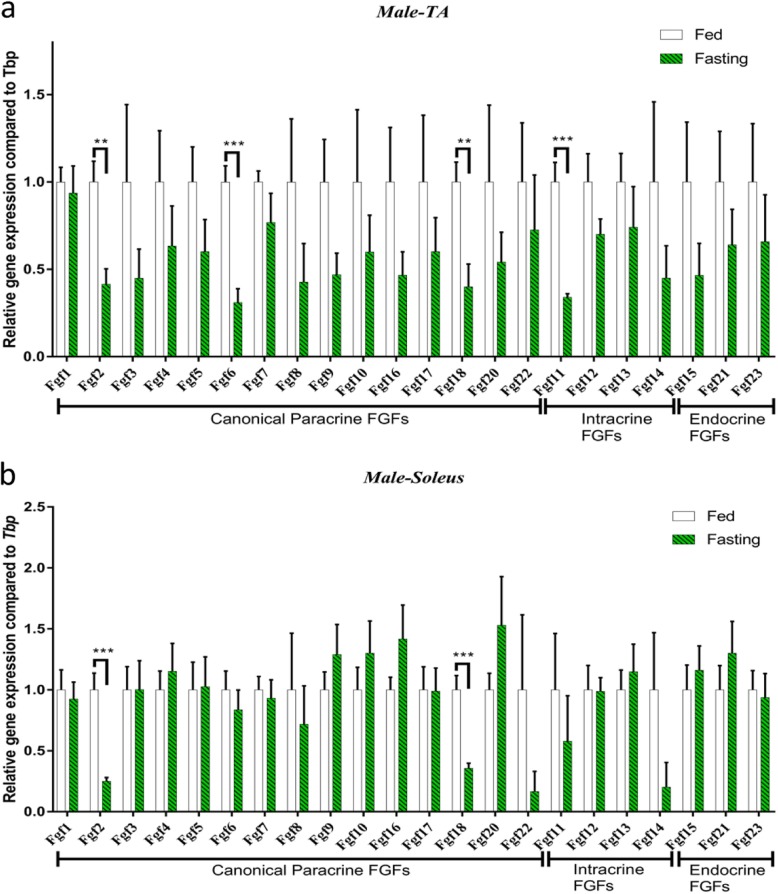

Fgf expression in the TA and soleus muscles during fasting in male C57BL/6 mice

In this study, we analysed all expression levels of Fgfs in the TA and soleus muscles of fasting male C57BL/6 mice. Our study showed that fasting influenced the Fgf expression of the TA and soleus. In fast-twitch TA muscle, fasting reduced canonical Fgf2, Fgf6 and Fgf18 expression by 2.4-, 3.2- and 2.5-fold, respectively. Intracellular Fgf11 was reduced by 2.9-fold during fasting (Fig. 3a). On the contrary, in slow-twitch soleus muscle, 24-h fasting induced the expression of Fgf2 and Fgf18 by 4.0- and 2.8-fold, respectively (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Fasting-stimulated Fgf expression pattern changes were different in the TA and soleus muscles in male C57BL/6 mice. aFgf expression in the TA muscle. bFgf expression in the soleus muscle. Data represent means ± S.E.M, n = 6; biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test

Fgf expression in the TA and soleus muscles during fasting in female C57BL/6 mice

In this study, the effects of fasting on the pattern of Fgf expression were different in female C57BL/6 mice compared with those in male mice. In fast-twitch TA muscle, as for canonical FGFs, 24-h fasting reduced Fgf2, Fgf6, Fgf8, Fgf18 and Fgf20 by 3.4-, 2.3-, 4.4-, 3.4- and 2.3-fold, respectively. Intracellular Fgf11, Fgf12 and Fgf14 were reduced by 4.2-, 1.5- and 4.2-fold, respectively. Endocrine Fgf15 and Fgf23 were reduced by 2.0- and 1.6-fold (Fig. 4a). In slow-twitch soleus muscle, 24-h fasting reduced the expression of Fgf2, Fgf8 and Fgf18 by 5.0-, 3.8- and 4.9-fold, respectively, while endocrine Fgf21 was 1.9-fold higher than that of fed soleus muscle (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Fasting-stimulated Fgf expression pattern changes were different in the TA and soleus muscles in female C57BL/6 mice. aFgf expression in the TA muscle. bFgf expression in the soleus muscle. Data represent means ± S.E.M, n = 6; biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test

Differential expression of Fgfs in the soleus and TA muscles according to the sex of mice

The expression of Fgfs in the soleus muscle was similar in male and female mice (Fig. 5a), while they were dramatically different in the TA muscle (Fig. 5b). Moreover, most of the Fgf expressions were higher in female TA muscle compared with those of male TA muscle, including canonical Fgf1, Fgf3–Fgf5, Fgf7–Fgf10, Fgf16, Fgf17 and Fgf20; intracellular Fgf12 and Fgf13; and endocrine Fgf15, Fgf21 and Fgf23.

Fig. 5.

Expression of Fgfs in skeletal muscles were divergent in male and female C57BL/6 mice. a Comparison of Fgf expression levels in the TA muscle. b Comparison of Fgf expression levels in the soleus muscle. Data represent means ± S.E.M, n = 6; biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test

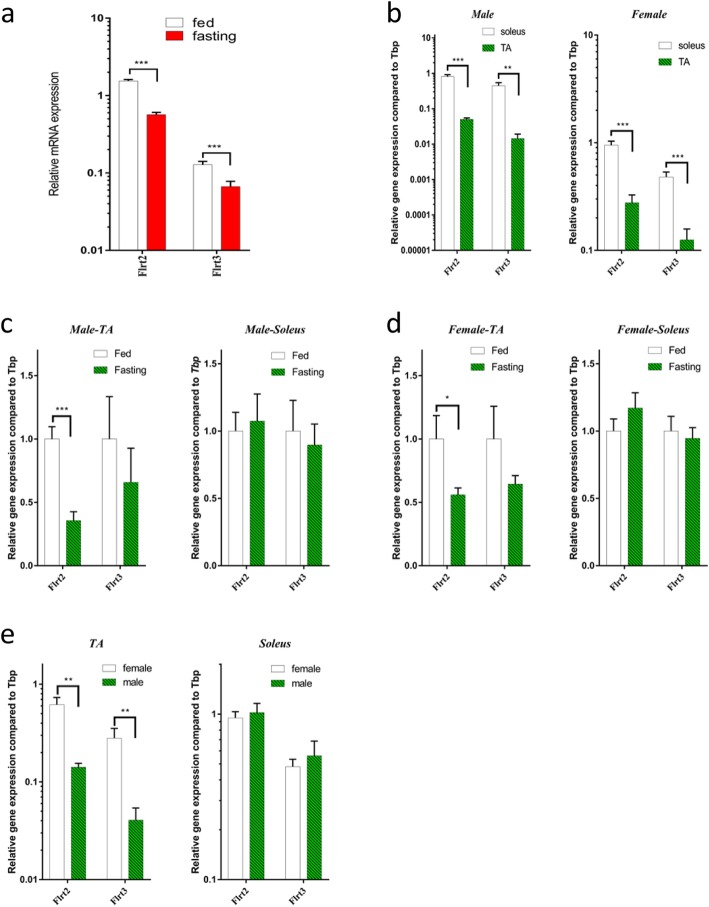

Differential expression of Flrts in the soleus and TA muscles of male and female mice

Fibronectin-leucine-rich transmembrane proteins (FLRTs) are markers of FGF activity [34, 35]. Fasting reduced Flrt2 and Flrt3 expression by 2.8- and 1.7-fold in mice gastrocnemius skeletal muscle (Fig. 6a). In male C57BL/6 mice, Flrt2 and Flrt3 in the soleus muscle were 16.1- and 30.8-fold higher than those of the TA muscle, and so is in female mice, Flrt2 and Flrt3 in the soleus muscle were 3.4- and 3.8-fold higher than those of the TA muscle (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, in male C57BL/6 mice, fasting reduced Flrt2 expression in the TA muscle, while fasting did not affect Flrt2 expression in the soleus muscle (Fig. 6c). Female C57BL/6 mice showed similar changes, fasting also reduced Flrt2 expression by 1.8-fold in the TA muscle and had no effect on the soleus muscle (Fig. 6d). In addition, in the TA muscle, basal Flrt2 and Flrt3 express more in female mice than in male C57BL/6 mice, while there is no difference in the soleus muscle (Fig. 6e).

Fig. 6.

Fasting-stimulated Flrt expression pattern in C57BL/6 mice. a Expression of Flrts in gastrocnemius muscle from 24-h fasted mice. b Basal Flrt expression levels in different muscle fibre types of male (light) and female (right) C57BL/6 mice. c Fasting-stimulated Flrt expression in the TA muscle of male (light) and female (right) C57BL/6 mice. d Fasting-stimulated Flrt expression in the soleus muscle of male (light) and female (right) C57BL/6 mice. e Fasting-stimulated Flrt expression in the TA (light) and soleus (right) muscles of male and female C57BL/6 mice. Data represent means ± S.E.M, n = 6; biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test

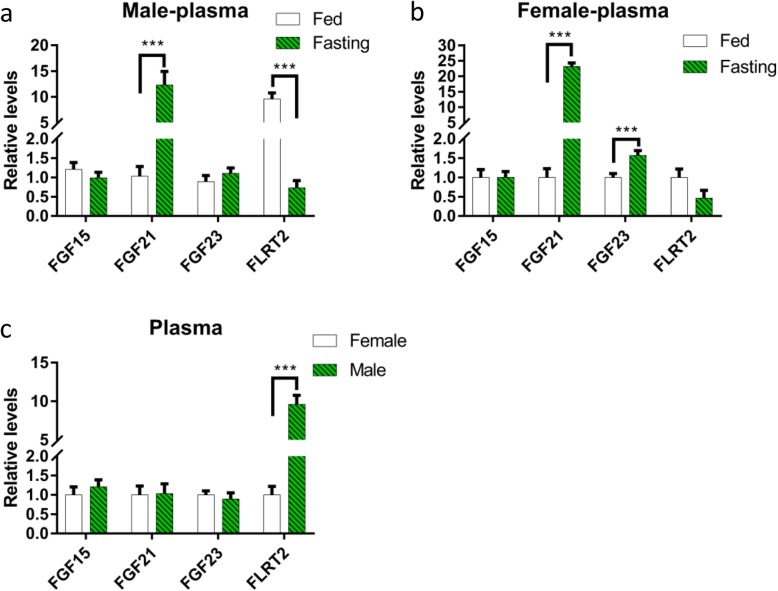

Endocrine FGF15, FGF21 and FGF23 levels in mice plasma

Endocrine FGFs have systemic effects via blood circulation, and plasma endocrine FGF concentration may alter according to condition changes or diseases. In several situations, they can act as biomarkers for some diseases [6]. Fasting significantly increased FGF21 circulating level in both male and female mice by 11.9- and 23.2-fold, respectively. FGF23 increased by 1.6-fold in female mice only. As for FLRTs, we measured FLRT2 and found it decreased by 13.1-fold in respond to fasting in male mice, but slightly decreased in female mice with no significant difference (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Expression of endocrine FGFs and FLRT2 in plasma. a Comparison of FGF15, FGF21, FGF23 and FLRT2 expression levels in response to fasting in male mice plasma. b Comparison of FGF15, FGF21, FGF23 and FLRT2 expression levels in response to fasting in female mice plasma. c Comparison of FGF15, FGF21, FGF23 and FLRT2 expression levels in female and male mice plasma. Data represent means ± S.E.M, n = 6; biological replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test

Discussion

Fasting and fed conditions divergently influence skeletal muscle structure and metabolism [36]. In this study, we found that fasting influenced expressions of Fgfs in mouse skeletal muscle. Furthermore, sex and skeletal muscle fibre type also influenced Fgf expression and the response to fasting.

The 15 canonical FGFs (FGF1–FGF10, FGF16–FGF18, FGF20 and FGF22) act predominantly in an autocrine and paracrine fashion and bind to FGFRs in a complex with heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) [37]. In this study, we found that fasting reduced Fgf2 and Fgf18 expression levels in both fibre types and sexes in mice. This result is consistent with a previous study that revealed that in fish, fgf2 mRNA level increased by 2.5-fold at both 4 and 12 days after refeeding compared to that in fasting conditions [38]. FGF2 released from skeletal muscle cells plays important roles in myogenesis and muscle development [39]. FGF2 contributes to muscle compensatory growth induced by refeeding [38]. Extracts from slow-twitch muscles contained higher levels of FGF2 than those from fast-twitch muscles [40]. This is in line with our results, that in both male and female mice, the expression levels of all Fgfs were higher or comparable in slow-twitch soleus muscle compared with those in fast-twitch TA muscle. What’s more, fasting reduced Fgf6 expression in the TA muscle rather than the soleus in both the male and female. Fasting reduced Fgf8 expression in female rather than male mice in both the TA and soleus muscles. Thus far, effects of fasting on the expression levels of other canonical Fgfs, except Fgf2, in the skeletal muscle have not been reported.

The intracellular FGFs (FGF11–FGF14) are non-secretory forms that bind and modulate voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs) [41]. Fgf13 is highly expressed in muscle and inhibits C2C12 cell proliferation and differentiation [42]. In our study, we found that fasting decreased Fgf13 expression in gastrocnemius skeletal muscle. In addition, it is of interest that Fgf11 is expressed more in the TA than in the soleus, which differs from any other Fgfs. And fasting reduced Fgf11 expression in both the male and female TA muscle rather than the soleus. Fasting reduced Fgf12 and Fgf14 expression levels in female soleus muscle other than TA. However, there have no reports related to the effects of fasting on intracellular FGF expression so far.

The three endocrine FGFs (FGF15/19, FGF21 and FGF23) act as hormones and lack affinity for HSPG binding, which enables their diffusion from the site of production into the circulation. Endocrine FGFs are expressed in various tissues and organs. They play roles in cell growth, differentiation, bile acid, glucose and lipid metabolism, as well as in the control of vitamin D and phosphate levels, thereby maintaining whole-body homeostasis [43, 44]. Secretory forms of FGFs directly and indirectly control the differentiation of fast- and slow-twitch muscle lineages, respectively [45]. The three endocrine FGF mRNA expressions are higher in the soleus than those in the TA in both sexes, and as for TA, they are higher in female than those in male. Oestrogen can increase hepatic production of FGF21, suggesting that sex influences gene expression [46]. In this study, we found that fasting reduced Fgf15 mRNA level in female TA muscle, while had no notably influence on the protein level in plasma. FGF15/19 induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy and blocked muscle atrophy [20]. FGF15/19 is mainly secreted from the small intestine in response to feed [47]. FGF21 has been reported negatively to regulate muscle mass and contribute towards skeletal muscle atrophy [16]. In this study, we found that fasting increased Fgf21 mRNA expression level in female soleus muscle and increased FGF21 level in plasma in both female and male mice. Emerging evidence has shown that fasting increases hepatic Fgf21 mRNA expression and plasma FGF21 level in mice [47]. FGF21 plays a role in fasting-induced muscle atrophy and weakness. However, a report suggested that fasting significantly decreased plasma FGF21 in obese subjects [48]. Circadian regulation has a stronger impact on plasma FGF21 than that of fasting within a 72-h period [49]. We also found that fasting decreased Fgf23 mRNA expression in gastrocnemius skeletal muscle in male mice, but increased FGF23 protein expression in female mice plasma. FGF23 is a bone-derived factor [50] and plays a role in metabolic diseases [51]. FGF23 induces cellular senescence in human skeletal muscle mesenchymal stem cells [52]. A study indicated that the expression of FGF23 is higher in females than in males [53], while we found no significant difference in the protein expression between two sexes.

Regarding the FGFR activation marker gene, we found that Flrts express more in the soleus than those in the TA, and fasting decreased the expression of Flrts in the TA muscle in two sexes, while in the soleus, the expression of Flrts was not significantly affected. As for FLRT2 in plasma, fasting reduced its concentration in male mice. What’s more, Flrt expression was sex-differentiated. There were more Flrts in female than in male mice TA muscle, while no sexual differences in the soleus muscle. However, in plasma, there is more FLRT2 protein expression in male mice. Thus, our study shows that the effect of fasting on FGF activity is closely related to the fibre type of skeletal muscle.

However, the lack of the data on FGF protein expressions in muscle is a limitation of this study. Our future work will focus on the related mechanisms and implications of individual FGFs on the function and structure of the skeletal muscle.

Perspectives and significance

This study provides a new insight into the effects of fasting on FGF expression in skeletal muscles. In addition, our study uncovers the expression profiles of FGFs in different muscle fibre types and sexes. The knowledge of the biological characteristics of FGF mRNA expression is critical for the research on skeletal muscle. This may also help to identify new biomarker in skeletal muscles and novel therapeutics targeting on fasting related health benefits.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the mice who have contributed to scientific research.

Abbreviations

- FGFs

Fibroblast growth factors

- FLRT

Fibronectin-leucine-rich transmembrane

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GTEx

Genotype-Tissue Expression

- HSPGs

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans

- TA

Tibialis anterior

- VGSCs

Voltage-gated sodium channels

Authors’ contributions

DGH, YXY, CCB and QGF contributed to the study conception and design. JWH, WNQ, YL, CX, HBY and WJH contributed to the acquisition of data. JWH and YXY contributed to the analysis of data. JWH, YXY and DGH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the following foundations: Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS-I2M 2016-I2M-3-007 and 2017-I2M-1-010), National Major Science and Technology Projects of China (2018ZX09711001-012, 2018ZX09711001-003-005 and 2017YFG0112900) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81470159 and 81770847).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All mouse procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiu-ying Yang, Email: lucia@imm.ac.cn.

Guan-hua Du, Email: dugh@imm.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Fon TK, Bookout AL, Ding X, et al. Research resource: comprehensive expression atlas of the fibroblast growth factor system in adult mouse. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(10):2050–2064. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuzon CT, Rigueur D, Merrill AE. Nuclear fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling in skeletal development and disease. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2019;17:138–146. doi: 10.1007/s11914-019-00512-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babina IS, Turner NC. Advances and challenges in targeting FGFR signalling in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(5):318–332. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somm E, Jornayvaz FR. Fibroblast growth factor 15/19: from basic functions to therapeutic perspectives. Endocr Rev. 2018;39(6):960–989. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuo I, Kimura-Yoshida C. Extracellular modulation of fibroblast growth factor signaling through heparan sulfate proteoglycans in mammalian development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23(4):399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itoh N, Ohta H, Konishi M. Endocrine FGFs: evolution, physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacotherapy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2015;6:154. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2015.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Degirolamo C, Sabba C, Moschetta A. Therapeutic potential of the endocrine fibroblast growth factors FGF19, FGF21 and FGF23. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(1):51–69. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Cabo R, Mattson MP. effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging, and disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2541–2551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1905136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zouhal H, Saeidi A, Salhi A, et al. Exercise training and fasting: current insights. Open Access J Sports Med. 2020;11:1–28. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S224919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nencioni A, Caffa I, Cortellino S, Longo VD. Fasting and cancer: molecular mechanisms and clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(11):707–719. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0061-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen S, Nathan JA, Goldberg AL. Muscle wasting in disease: molecular mechanisms and promising therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14(1):58–74. doi: 10.1038/nrd4467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cantó C, Jiang LQ, Deshmukh AS, et al. Interdependence of AMPK and SIRT1 for metabolic adaptation to fasting and exercise in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2010;11(3):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang X, Brobst D, Chan WS, et al. Muscle-generated BDNF is a sexually dimorphic myokine that controls metabolic flexibility. Sci Signal. 2019;12(594). 10.1126/scisignal.aau1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Groves JA, Hammond CL, Hughes SM. Fgf8 drives myogenic progression of a novel lateral fast muscle fibre population in zebrafish. Development. 2005;132(19):4211–4222. doi: 10.1242/dev.01958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stranska Z, Svacina S. Myokines - muscle tissue hormones. Vnitr Lek. 2015;61(4):365–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oost LJ, Kustermann M, Armani A, Blaauw B, Romanello V. Fibroblast growth factor 21 controls mitophagy and muscle mass. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle. 2019;10(3):630–642. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitham M, Febbraio MA. The ever-expanding myokinome: discovery challenges and therapeutic implications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:719–729. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim RW, Hauschka SD. A rapid decrease in epidermal growth factor-binding capacity accompanies the terminal differentiation of mouse myoblasts in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 1984;98:739–747. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.2.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ornitz DM, Marie PJ. Fibroblast growth factor signaling in skeletal development and disease. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1463–1486. doi: 10.1101/gad.266551.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benoit B, Meugnier E, Castelli M, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 19 regulates skeletal muscle mass and ameliorates muscle wasting in mice. Nat. Med. 2017;23:990–996. doi: 10.1038/nm.4363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee P, Linderman JD, Smith S, et al. Irisin and FGF21 are cold-induced endocrine activators of brown fat function in humans. Cell Metab. 2014;19:302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flück M, Hoppeler H. Molecular basis of skeletal muscle plasticity--from gene to form and function. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;146:159–216. doi: 10.1007/s10254-002-0004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gollnick PD, Sjodin B, Karlsson J, Jansson E, Saltin B. Human soleus muscle: a comparison of fiber composition and enzyme activities with other leg muscles. Pflugers Arch. 1974;348:247–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00587415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tasić D, Dimov D, Gligorijević J, Veličković L, Katić K, Krstić M, Dimov I. Muscle fibre types and fibre morphometry in the tibialis posterior and anterior of the rat: a comparative study. Med Biol. 2003;10:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terova G, Bernardini G, Binelli G, Gornati R, Saroglia M. cDNA encoding sequences for myostatin and FGF6 in sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax, L.) and the effect of fasting and refeeding on their abundance levels. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2006;30(4):304–319. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosa-Caldwell ME, Greene NP. Muscle metabolism and atrophy: let’s talk about sex. Biol Sex Differ. 2019;10(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s13293-019-0257-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia WH, Wang NQ, Lin Y, Chen X, Hou BY, Qiang GF, Chan CB, Yang XY, Du GH. Effect of skeletal muscle phenotype and gender on fasting-induced myokine expression in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;514:407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.04.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hakvoort TB, Moerland PD, Frijters R, et al. Interorgan coordination of the murine adaptive response to fasting. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(18):16332–16343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.216986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinouchi K, Magnan C, Ceglia N, et al. Fasting imparts a switch to alternative daily pathways in liver and muscle. Cell Rep. 2018;25:3299–3314.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang XY, MCL T, Hu X, Jia WH, Du GH, Chan CB. Interaction of CREB and PGC-1alpha induces fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 5 expression in C2C12 myotubes. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018;50:1574–1584. doi: 10.1159/000494655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radonić A, Thulke S, Mackay IM, Landt O, Siegert W, Nitsche A. Guideline to reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313(4):856–862. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qiang G, Kong HW, Fang D, McCann M, Yang X, Du G, Blüher M, Zhu J, Liew CW. The obesity-induced transcriptional regulator TRIP-Br2 mediates visceral fat endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced inflammation. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11378. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets--update. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:D991–D995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Böttcher RT, Pollet N, Delius H, Niehrs C. The transmembrane protein XFLRT3 forms a complex with FGF receptors and promotes FGF signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:38–44. doi: 10.1038/ncb1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haines BP, Wheldon LM, Summerbell D, et al. Regulated expression of FLRT genes implies a functional role in the regulation of FGF signalling during mouse development. Dev Biol. 2006;297(1):14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aird TP, Davies RW, Carson BP. Effects of fasted vs fed-state exercise on performance and post-exercise metabolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2018;28(5):1476–1493. doi: 10.1111/sms.13054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beenken A, Mohammadi M. The FGF family: biology, pathophysiology and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:235–253. doi: 10.1038/nrd2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chauvigne F, Gabillard JC, Weil C, Rescan PY. Effect of refeeding on IGFI, IGFII, IGF receptors, FGF2, FGF6, and myostatin mRNA expression in rainbow trout myotomal muscle. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2003;132:209–215. doi: 10.1016/s0016-6480(03)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi JS, Yoon HI, Lee KS, Choi YC, Yang SH, Kim IS, Cho YW. Exosomes from differentiating human skeletal muscle cells trigger myogenesis of stem cells and provide biochemical cues for skeletal muscle regeneration. J Control Release. 2016;222:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson JE, Liu L, Kardami E. Distinctive patterns of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) distribution in degenerating and regenerating areas of dystrophic (mdx) striated muscles. Dev Biol. 1991;147(1):96–109. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(05)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei EQ, Barnett AS, Pitt GS, et al. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors in the heart: a potential locus for cardiac arrhythmias. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2011;21(7):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu H, Shi X, Wu G, et al. FGF13 regulates proliferation and differentiation of skeletal muscle by down-regulating Spry1. Cell Prolif. 2015;48(5):550–560. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernandes-Freitas I, Owen BM. Metabolic roles of endocrine fibroblast growth factors. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;5, 25:30. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo Y, Ye S, Li X, et al. Emerging structure-function paradigm of endocrine FGFs in metabolic diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019;40(2):142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin J, Lee R, Ono Y, et al. Spatiotemporal coordination of FGF and Shh signaling underlies the specification of myoblasts in the zebrafish embryo. Dev Cell. 2018;46(6):735–750.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim JH, Meyers MS, Khuder SS, et al. Tissue-selective estrogen complexes with bazedoxifene prevent metabolic dysfunction in female mice. Mol Metab. 2014;3(2):177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guan D, Zhao L, Chen D, Yu B, Yu J. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor 15/19 and 21 on metabolism: in the fed or fasted state. J Transl Med. 2016;14:63. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0821-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nygaard EB, Orskov C, Almdal TP, Vestergaard H, Andersen B. Fasting decreases plasma FGF21 in obese subjects and the expression of FGF21 receptors in adipose tissue in both lean and obese subjects. J. Endocrinol. 2018;239:73–80. doi: 10.1530/JOE-18-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andersen B, Beck-Nielsen H, Hojlund K. Plasma FGF21 displays a circadian rhythm during a 72-h fast in healthy female volunteers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;75(4):514–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quarles LD. Skeletal secretion of FGF-23 regulates phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(5):276–286. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bonnet N. Bone-derived factors: a new gateway to regulate glycemia. Calcif Tissue Int. 2017;100(2):174–183. doi: 10.1007/s00223-016-0210-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sato C, Iso Y, Mizukami T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 induces cellular senescence in human mesenchymal stem cells from skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;470(3):657–662. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ben-Aharon I, Levi M, Margel D, et al. Premature ovarian aging in BRCA carriers: a prototype of systemic precocious aging. Oncotarget. 2018;9(22):15931–15941. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.