Abstract

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to provide updated pooled effect sizes of evidence-based psychotherapies and medications for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and to investigate potential moderators of outcomes. Seventy-nine randomized controlled trials (RCT) including 11,002 participants with a diagnosis of GAD were included in a meta-analysis that tested the efficacy of psychotherapies or medications for GAD. Psychotherapy showed a medium to large effect size (g = 0.76) and medication showed a small effect size (g = 0.38) on GAD outcomes. Psychotherapy also showed a medium effect on depression outcomes (g = 0.64) as did medications (g = 0.59). Younger age was associated with a larger effect size for psychotherapy (p < 0.05). There was evidence of publication bias in psychotherapy studies. This analysis found a medium to large effect for empirically supported psychotherapy interventions on GAD outcomes and a small effect for medications on GAD outcomes. Both groups showed a medium effect on depression outcomes. Because medication studies had more placebo control conditions than inactive conditions compared to psychotherapy studies, effect sizes between the domains should not be compared directly. Patient age should be further investigated as a potential moderator in psychotherapy outcomes in GAD.

Keywords: GAD, meta-analysis: randomized controlled trial, generalized anxiety disorder, medication, therapy

Introduction

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is characterized by worry about a number of events or activities that is excessive and difficult to control (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). GAD is relatively common, with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 4.3% in the general population (Kessler, Petukhova, Sampson, Zaslavsky, & Wittchen, 2012), and associated with marked impairment in role functioning and social life to a degree equivalent to major depression (Kessler, DuPont, Berglund, & Wittchen, 1999), as well as impairments in psychosocial functioning, role functioning, work productivity, and health-related quality of life (Revicki et al., 2012). GAD is also associated with increased health care utilization and medical costs. Marciniak et al. (2005) found that the total lifetime medical cost for individuals with any anxiety disorder was US$6475, and that a diagnosis of GAD was associated with an additional US$2138 total cost. Furthermore, there is evidence that GAD is associated with utilizing emergency departments as much as twice as often as patients with another Axis I diagnosis (Jones, Ames, Jeffries, Scarinci, & Brantley, 2001). Given the high cost and adverse outcomes associated with GAD, an updated critical comparison of the numerous available treatments is necessary.

Evidence-based psychotherapies have shown large effect sizes on GAD outcomes (Hedges’ g = 0.80; Cuijpers, Cristea, Karyotaki, Reijnders, & Huibers, 2016). Research has also supported the utility of pharmacological interventions for GAD. Specifically, a meta-analysis of 21 placebo-controlled studies yielded a small effect size (d = 0.39; Hidalgo, Tupler, & Davidson, 2007). Since these dates, new randomized controlled trials (RCT) are available for both psychotherapies and pharmacological interventions. Thus, there is a need to update the pooled effect sizes to reflect the addition of these trials to better understand the effects of these interventions on GAD.

Moreover, there are several candidates for moderators of GAD treatment outcomes. For example, there is some evidence that older age might lead to worse GAD treatment outcomes (Gonçalves & Byrne, 2012; Gould, Coulson, & Howard, 2012; Hendriks, Oude Voshaar, Keijsers, Hoogduin, & Van Balkom, 2008; Pinquart & Duberstein, 2007; Wetherell et al., 2013). Next, the prognostic effect of comorbid disorders on GAD outcomes is unclear, with some evidence that comorbidity is indicative of worse prognosis (Bruce et al., 2005) and some evidence that comorbidity in GAD is associated with larger treatment gains (Newman, Przeworski, Fisher, & Borkovec, 2010). A recent systematic review investigated a large number of potential treatment moderators of treatment for anxiety disorders and found little evidence for demographic variables, baseline symptom severity, or comorbidity as moderators (Schneider, Arch, & Wolitzky-Taylor, 2015). However, this study was not specific to GAD, only included 24 studies that compared at least two active treatments, and did not employ meta-analytic techniques.

The present investigation employed a meta-analytic approach to compare the effect of evidence-based psychotherapies and pharmacotherapy to control conditions. Both primary GAD outcomes and secondary depression outcomes were compared, and follow-up data were examined when available. We also explored a number of plausible moderators, including demographic variables (e.g. age, percent female), clinical variables (e.g. pretreatment severity, percent comorbid), and study variables (e.g. control type). Based on the extant literature, we hypothesized that psychotherapy would show a large effect size compared to waitlist and pill placebo conditions and a small effect size compared to treatment as usual or psychological control conditions (Cuijpers et al., 2016). We also hypothesized that medication would show a small effect size compared to controls (Hidalgo et al., 2007).

Method

Study selection

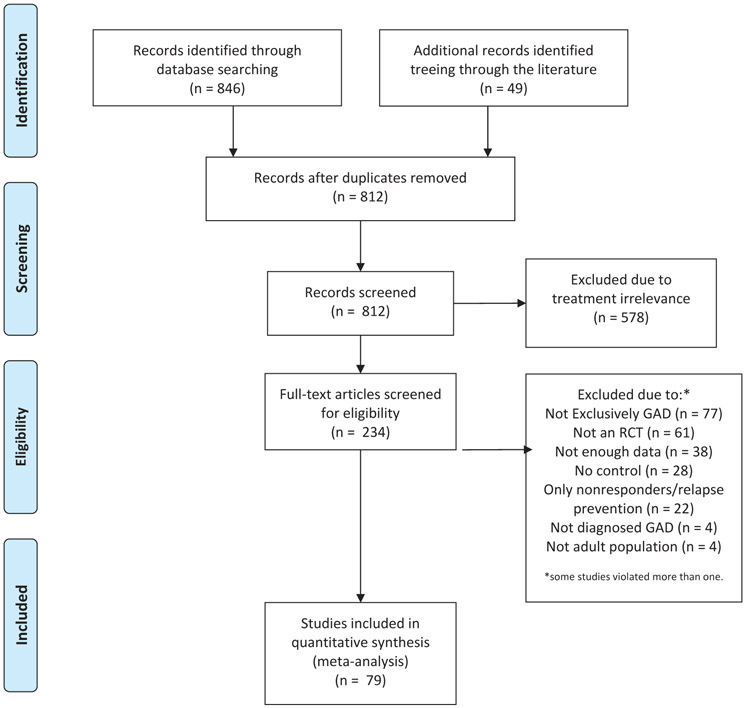

We selected RCT of both psychological and pharmacological treatment for GAD using a comprehensive search strategy. We searched the following databases: PsycINFO, PubMed, EBSCO, Web of Science, and Cochrane database of systematic reviews. We searched for articles on psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for GAD from up until June 2017. The searches included the following terms: “cognitive behavioral, ” “cognitive behavioral therapy,” “acceptance and commitment therapy,” “worry exposure,” “psychotherapy,” “pharmacotherapy,” “pharmacology,” “SSRIs,” OR “benzodiazepines,” in addition to “clinical trial” or “trial” alone; and in combination with “generalized anxiety disorder,” or “GAD.” These words were searched as key words, title, abstract, and Medical Subject Headings. We also examined citation maps and used the “cited by” search tools. These findings were cross-referenced with references from reviews. We included articles found in two existing meta-analyses examining CBT for GAD (Cuijpers et al., 2016) and pharmacotherapy for GAD (Hidalgo et al., 2007). Lastly, we asked colleagues from the United States of America and the Netherlands to identify any RCT for GAD that we had left out. These initial search strategies produced 846 potential articles. Examination of the abstracts identified 79 articles that met all inclusion criteria. The study selection process is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of inclusion of studies.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) participants who met full DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR, or DSM-5 criteria for GAD; (b) empirically supported psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, acceptance-based behavior therapy, applied relaxation, worry exposure, etc.; or empirically supported pharmacotherapy, including SSRIs, benzodiazepines, and other anxiolytics; (c) included a waitlist, treatment as usual, or pill placebo or psychological placebo control condition; and (d) studies that used validated measures of generalized anxiety. Studies meeting the following exclusion criteria were not selected for the current meta-analysis: (a) single case studies; (b) treatment conditions based on augmentation of psychological treatment; (c) studies of relapse prevention; (d) studies only treating patients who showed a response to the treatment; (e) studies with insufficient data unless study authors were able to provide such data; (f) studies with redundant data; and (g) studies on children. Studies were also imported from the extant meta-analyses (Cuijpers et al., 2016; Hidalgo et al., 2007). Of the 234 studies screened, 155 were excluded. Seventy-seven did not report on a GAD group specifically and four did not diagnose GAD according to the DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR, or DSM-V. Sixty-one were not RCT. Thirty-eight had missing data; we attempted to contact the authors of these studies but were unable to either receive a response or obtain the relevant data. Twenty-eight studies did not provide a sufficient control condition. Twenty-two studies recruited nonresponders to treatment or relapse prevention. Four studies were excluded for a child population. In total, 79 studies with 11,002 participants met the final inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. Study characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| Authors | Year | N1 | Primary measure(s) | Secondary measure (s) |

Primary outcome2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaka et al. | 2014 | 291 | HAM-A | Duloxetine > PP | |

| Aliyev et al. | 2008 | 74 | HAM-A | Depakine-chrono > PP | |

| Allgulander et al. | 2001 | 268 | HAM-A | Venlafaxine (37.5 mg) > PP | |

| 260 | Venlafaxine (75 mg) > PP | ||||

| 261 | Venlafaxine (150 mg) > PP | ||||

| Allgulander et al. | 2004 | 370 | HAM-A | MADRS | Sertraline > PP |

| Bakhsani et al. | 2007 | 13 | BAI, HAM-A | Diazepam + tricyclic antidepressant > PP | |

| 13 | |||||

| CBT > PP | |||||

| Ball et al. | 2015 | 226 | HAM-A | Duloxetine > PP | |

| Barlow et al. | 1992 | 23 | HAM-A, STAI-T | BDI, HAM-D | CT > WL |

| 20 | Relaxation > WL | ||||

| 21 | CT + relaxation > WL | ||||

| Bidzan et al. | 2012 | 254 | HAM-A | Vortioxetine > PP | |

| Bonne et al. | 2003 | 44 | HAM-A, STAI-T | BDI, HAM-D | Homeopathic > PP |

| Borkovec et al. | 1987 | 30 | HAM-A, STAI-T | HAM-D | CT > Psych PL |

| Borkovec et al. | 1993 | 36 | HAM-A, PSWQ, STAI-T | BDI, HAM-D | AR > Psych PL |

| 38 | CBT > Psych PL | ||||

| Bowman et al. | 1997 | 35 | HAM-A, STAI-T | Self-examination therapy > WL | |

| Brawman-Mintzer et al. | 2006 | 326 | HAM-A | MADRS | Sertraline > PP |

| Brenes et al. | 2015 | 118 | HAM-A, PSWQ | BDI | Telephone CBT > Psych PL |

| Butler et al. | 1991 | 37 | BAI, HAM-A, STAI-T | BDI | BT > WL |

| 38 | CBT > WL | ||||

| Connor et al. | 2002 | 35 | HAM-A | Kava kava < PP | |

| Dahlin et al. | 2016 | 85 | BAI, PSWQ | MADRS, PHQ-9 | Internet acceptance BT > WL |

| Darcis et al. | 1995 | 110 | HAM-A | Hydroxyzine > PP | |

| Davidson et al. | 1999 | 191 | HAM-A | Buspirone > PP | |

| 185 | Venlafaxine (75 mg) > PP | ||||

| 185 | Venlafaxine(150 mg) > PP | ||||

| Davidson et al. | 2004 | 307 | HAM-A | HAM-D | Escitalopram > PP |

| Davidson et al. | 2008 | 70 | HAM-A | Duloxetine > PP | |

| Dugas et al. | 2003 | 52 | BAI, PSWQ | BDI | Group CBT > WL |

| Dugas et al. | 2010 | 42 | PSWQ, STAI-T | BDI-II | AR > WL |

| 43 | CBT > WL | ||||

| Durham et al. | 1994 | 30 | BAI, HAM-A, STAI-T | BDI | Analytic therapy high contact < Psych PL |

| 31 | |||||

| 31 | Analytic therapy low contact < Psych PL | ||||

| 36 | |||||

| CT high contact > Psych PL | |||||

| CT low contact > Psych PL | |||||

| Feltner et al. | 2003 | 130 | HAM-A | HAM-D | Lorazepam > PP |

| 135 | Pregbalin (150 mg) > PP | ||||

| 127 | Pregbalin (600 mg) > PP | ||||

| Gelenberg et al. | 2000 | 238 | HAM-A | Venlafaxine > PP | |

| Gommoll et al. | 2015 | 444 | HAM-A | HAM-D | Vilazodone (20 mg) > PP |

| 444 | Vilazodone (40 mg) > PP | ||||

| Hackett et al. | 2003 | 186 | HAM-A | Diazepam > PP | |

| 288 | Venlafaxine (75 mg) > PP | ||||

| 276 | Venlafaxine (150 mg) > PP | ||||

| Hartford et al. | 2007 | 323 | HAM-A | Duloxetine > PP | |

| 325 | Venlafaxine > PP | ||||

| Hoge et al. | 2013 | 89 | BAI, HAM-A | MBSR > Psych PL | |

| Hoyer et al. | 2009 | 57 | HAM-A, PSWQ, STAI-T | BDI, HAM-D | AR > WL |

| 58 | Worry exposure > WL | ||||

| Johnston et al. | 2011 | 85 | PSWQ | PHQ-9 | Clinician-guided iCBT > WL |

| 88 | Coach-guided iCBT > WL | ||||

| Jones et al. | 2016 | 41 | PSWQ-A | PHQ-9 | iCBT > WL |

| Kasper et al. | 2009 | 249 | HAM-A | HAM-D | Pregbalin > PP |

| 253 | Venlafaxine > PP | ||||

| Koszycki et al. | 2010 | 22 | BAI, HAM-A, PSWQ | BDI | CBT > Psych PL |

| Lader et al. | 1998 | 163 | HAM-A | MADRS | Buspirone > PP |

| 162 | Hydroxyzine > PP | ||||

| Ladoucer et al. | 2000 | 26 | BAI, PSWQ | BDI | CBT > WL |

| Leichsenring et al. | 2009 | 57 | BAI, HAM-A, PSWQ, STAI-T | BDI | CBT > Psych PL |

| Lenze et al. | 2009 | 177 | HAM-A, PSWQ | HAM-D | Escitalopram > PP |

| Levy Berg et al. | 2009 | 61 | BAI | Affect-Focused Psychotherapy > TAU | |

| Linden et al. | 2005 | 72 | HAM-A, STAI-T | CBT Group A > Psych PL | |

| 72 | CBT Group B > Psych PL | ||||

| Llorca et al. | 2002 | 196 | HAM-A | Hydroxyzine > PP | |

| Mahableshwarkar et al. | 2014 | 303 | HAM-A | Duloxetine > PP | |

| 308 | Vortioxetine (2.5 mg) > PP | ||||

| 302 | Vortioxetine (5 mg) > PP | ||||

| 308 | Vortioxetine (10 mg) > PP | ||||

| Mohlman et al. a | 2003 | 15 | STAI-T | BDI | Enhanced CBT > WL |

| Mohlman et al. b | 2003 | 21 | BAI | BDI | Standard CBT > WL |

| Moller et al. | 2001 | 207 | HAM-A | HAM-D | Alprazolam > PP |

| 205 | Opipramol > PP | ||||

| Montgomery et al. | 2006 | 266 | HAM-A | HAM-D | Pregbalin > PP |

| Pande et al. | 2003 | 126 | HAM-A | HAM-D | Lorazepam > PP |

| 132 | Pregbalin (150 mg) > PP | ||||

| 132 | Pregbalin (600 mg) > PP | ||||

| Park et al. | 2014 | 94 | HAM-A, PSWQ, STAI-T | BDI | Gamisoyo-San (Individual) > PP |

| 95 | Gamisoyo-San (Multi-Compound) > PP | ||||

| Paxling et al. | 2011 | 82 | BAI, PSWQ, STAI-T | BDI, MADRS | iCBT > WL |

| Pollack et al. | 2001 | 324 | HAM-A | Paroxetine > PP | |

| Pollack et al. a | 2008 | 425 | HAM-A | Tiagbine (4 mg) > PP | |

| 420 | Tiagbine (8 mg) > PP | ||||

| 421 | Tiagbine (12 mg) > PP | ||||

| Pollack et al. b | 2008 | 441 | HAM-A | Tiagbine > PP | |

| Pollack et al. c | 2008 | 438 | HAM-A | Tiagbine > PP | |

| Power et al. | 1990 | 21 | HAM-A | CBT > PP | |

| 21 | Diazepam > PP | ||||

| Power et al. | 1990 | 40 | HAM-A | CBT > PP | |

| 40 | Diazepam > PP | ||||

| Rezvan et al. | 2008 | 24 | PSWQ | CBT > WL | |

| 24 | CBT + IPT > WL | ||||

| Rickels et al. | 2000 | 182 | HAM-A | Venlafaxine (75 mg) > PP | |

| 177 | Venlafaxine (150 mg) > PP | ||||

| 182 | Venlafaxine (225 mg) > PP | ||||

| Rickels et al. | 2003 | 368 | HAM-A | Paroxetine (20 mg) > PP | |

| 377 | Paroxetine (40 mg) > PP | ||||

| Rickels et al. | 2005 | 173 | HAM-A | HAM-D | Alprazolam > PP |

| 174 | Pregbalin (300 mg) > PP | ||||

| 172 | Pregbalin (450 mg) > PP | ||||

| 170 | Pregbalin (600 mg) > PP | ||||

| Robinson et al. | 2010 | 95 | PSWQ | PHQ-9 | Clinician-guided iCBT > WL |

| 98 | Technician-guided iCBT > WL | ||||

| Roemer et al. | 2008 | 31 | PSWQ | BDI | ACT > WL |

| Rothschild et al. | 2012 | 289 | HAM-A | Vortioxetine < PP | |

| Sarris et al. | 2013 | 58 | BAI, HAM-A | Kava kava > PP | |

| Stanley et al. | 1996 | 31 | HAM-A, PSWQ, STAI-T | HAM-D | CBT < Psych PL |

| Stanley et al. a | 2003 | 64 | HAM-A, PSWQ, STAI-T | BDI, HAM-D | CBT > Psych PL |

| Stanley et al. b | 2003 | 9 | BAI, PSWQ | BDI | CBT > TAU |

| Stanley et al. | 2009 | 134 | HAM-A, PSWQ | BDI-II | CBT > TAU |

| Stein et al. | 2008 | 121 | HAM-A | Agomelatine > PP | |

| Stein et al. | 2014 | 233 | HAM-A | Agomelatine > PP | |

| 234 | Escitalopram > PP | ||||

| Stein et al. | 2017 | 270 | HAM-A | Agomelatine (10 mg) > PP | |

| 278 | Agomelatine (25 mg) > PP | ||||

| Titov et al. | 2009 | 35 | PSWQ | PHQ-9 | iCBT > WL |

| Titov et al. | 2010 | 34 | PSWQ | iCBT > WL | |

| Van der Heiden et al. | 2012 | 56 | PSWQ, STAI-T | BDI-II | Intolerance of uncertainty therapy > WL |

| 57 | |||||

| Metacognitive therapy > WL | |||||

| Wetherell et al. | 2003 | 39 | BAI, HAM-A, PSWQ | BDI, HAM-D | CBT > WL |

| 36 | CBT > Psych PL | ||||

| Wetherell et al. | 2009 | 31 | HAM-A, PSWQ | BDI-II | Modular psychotherapy > TAU |

| White et al. | 1992 | 42 | STAI-T | BDI | BT > WL |

| 37 | CBT > WL | ||||

| 42 | CT > WL | ||||

| 21 | Subconscious retraining > WL | ||||

| Wu et al. | 2011 | 210 | HAM-A | Duloxetine > PP | |

| Zinbarg et al. | 2007 | 18 | BAI, PSWQ | CBT > WL |

Abbreviations: ACT: acceptance and commitment therapy; AR: applied relaxation; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961); BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996); BT: behavior therapy; CBT: cognitive behavior therapy; CT: cognitive therapy; HAM-A: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAM-D: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton, 1960); iCBT: internet cognitive behavior therapy; IPT: interpersonal therapy; MADRS: Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (Montgomery & Asberg, 1979); MBSR: mindfulness-based stress reduction; PP: pill placebo; PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire—9 (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001); PSWQ: Penn State Worry Questionnaire; PSWQ-A: Penn State Worry Questionnaire—Abbreviated; Psych PL: psychological placebo; STAI-T: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—Trait; TAU: treatment as usual; WL: waitlist.

Software

Analyses were completed with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3.3070 (CMA; Biostat, 2014).

Procedure

The primary outcome was reduction of GAD symptoms. The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A; Hamilton, 1959), Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990) and Penn State Worry Questionnaire—Abbreviated version (PSWQ-A; Hopko et al., 2003), Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988), and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—Trait (STAI-T; Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1970) captured generalized anxiety outcome in all studies. Outcome data from the above measures were combined from each study using every measure available. The secondary outcome of this analysis was depression symptoms. Studies with multiple primary or secondary outcome measures had outcomes combined in the respective domain. Combined measures were given equal weight. Table 2 provides a complete list of included outcome measures.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcome measures.

| Outcome | Measure |

|---|---|

| Primary | Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale | |

| Penn State Worry Questionnaire | |

| Penn State Worry Questionnaire—Abbreviated | |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—Trait | |

| Secondary | Beck Depression Inventory |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II | |

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale | |

| Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale | |

| Patient Health Questionnaire—9 |

Data on the following variables were also collected: treatment protocol (e.g. CBT, sertraline), treatment dose (i.e. number of sessions and/or medication dosage), year of publication, study quality (allocation sequence, concealment of allocation to conditions, blind assessors, dealing with incomplete outcome data), treatment quality (use of a treatment manual, therapist training, check of treatment integrity), flexible versus fixed dosage, mean age, percent female of total sample, percent comorbidity, and follow-up length (if applicable). Dependent variables were classified as either primary (measures of generalized anxiety) or secondary (measures of depression).

Control conditions were categorized as pill placebo (n = 43), waitlist (WL; n = 22), psychological placebo (n = 10), or treatment as usual (TAU; n = 5), with one study (Wetherell, Gatz, & Craske, 2003) including both a WL and psychological placebo group. Psychological control conditions that were categorized as psychological placebo included supportive therapy, affect-focused body psychotherapy, clinician-supported therapy, nondirective therapy, nondirective supportive therapy, spiritually based intervention, stress management education, discussion group, minimal contact (providing assessments/brief support), and short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy. Control conditions that study authors termed TAU were considered TAU for the analysis. Control conditions in which participants did not receive any treatment for GAD symptoms for a specified amount of time were considered WL.

Quantitative data analysis

The effect size for each study was computed using Hedges’ g (Rosenthal, 1991) in CMA. Hedges’ g allows for correction for small sample sizes (Hedges & Olkin, 1985). When the necessary data were available, Hedges’ g was calculated using means and standard deviations. If means and standard deviations were not reported, we contacted the authors to obtain these data. In cases that these values were not obtainable, Hedges’ g was calculated using available data (least squares means, standard errors). If there were not sufficient data to calculate Hedges’ g and authors could not be reached, the data were not included in the final analyses. These controlled effect sizes may be interpreted conservatively with Cohen’s convention of small (0.2), medium (0.5), and large (0.8) effect sizes (Cohen, 1988). When there were multiple outcomes per domain, they were combined according to Borenstein, Hedges, and Rothstein (2007).

The I2 statistic was used to measure heterogeneity. The I2 statistic describes the percentage of variation due to heterogeneity, with 0% indicating no observed heterogeneity, 25% low, 50% moderate, and 75% high heterogeneity (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, 2003). In addition, a test for significance of heterogeneity and the Q value are reported. Because we expected considerable heterogeneity due to patient and treatment variability, we used the random effects model in all analyses. For categorical moderators, we reported p-values and between-group heterogeneity (Q) as recommended by Hedges and Olkin (1985) and for continuous variables we used metaregression analyses, which is indicated by a slope and a p-value.

Study quality ratings

The quality of the studies that were included was rated using four items from the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (Higgins & Green, 2011): (1) adequately random sequence generation for group assignment, (2) concealment of allocation to conditions, (3) blind assessors, and (4) dealing with incomplete outcome data.

Results

Characteristics and quality of included trials

Seventy-nine RCT including 11,002 participants met criteria for inclusion. Of the 79 included studies, 30 had low bias for sequence generation, 22 qualified for low bias for allocation concealment, 66 qualified for low bias for blind assessors, and 39 qualified for low bias for incomplete outcome data. Six studies met 0 study quality criteria, 27 studies met one criterion, 21 studies met two criteria, 10 studies met three criteria, and 15 studies met all four criteria.

Heterogeneity

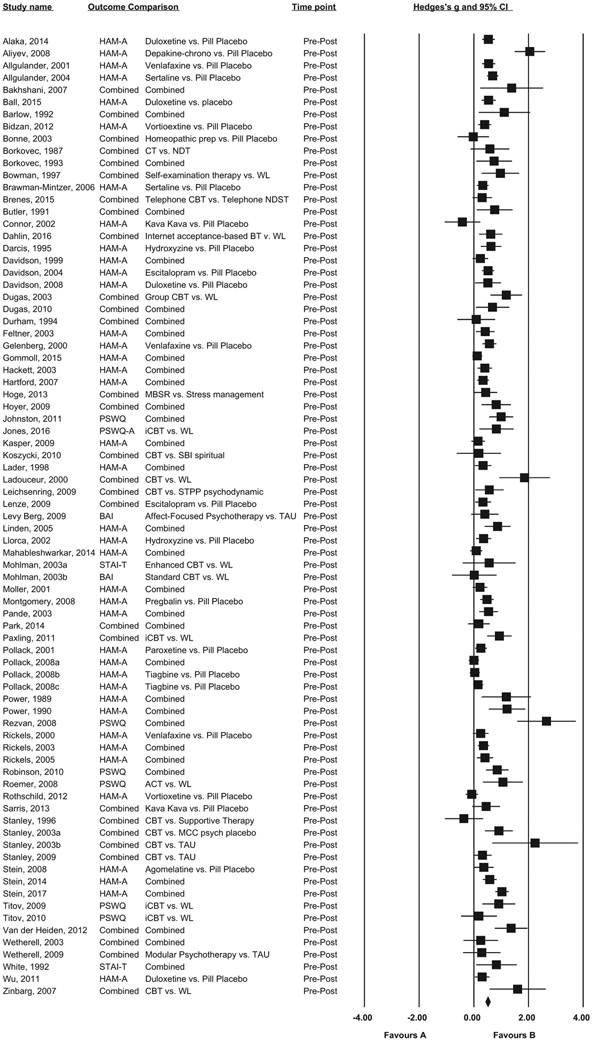

A heterogeneity analysis was conducted to test the assumption that the effect sizes were from a homogeneous sample (Hedges & Olkin, 1985). An analysis of all primary outcomes on pretreatment to posttreatment time points revealed significant moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 72.56, p < 0.001). This was also true when psychotherapy (I2 = 54.90, Q = 84.25, p < 0.001) and medication studies (I2 = 54.26, Q = 163.72, p < 0.001) were considered separately. Therefore, random effects analyses were most appropriate and moderator analyses were justified. Studies and their effect sizes are presented in a forest plot (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect sizes of treatments for GAD in adults compared with control conditions: Hedges' g.

Outliers were defined as studies whose effect size 95% confidence interval (CI) did not overlap with the 95% CI of the pooled effect size of its psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy domain. When outliers were excluded, heterogeneity decreased in psychotherapy (I2 = 37.84, p = 0.01) and pharmacotherapy (I2 = 40.14, p < 0.01) domains. Excluding outliers did not significantly change primary outcomes for either psychotherapy or medication domains, and therefore results excluding outliers are not reported. The following analyses were conducted on all studies including outliers.

Efficacy on primary and secondary outcomes

Efficacy of psychotherapy versus control conditions on primary outcome measures

This analysis included 39 comparisons. Consistent with prediction, evidence-based psychotherapies outperformed control conditions on primary outcome measures at posttreatment with a medium to large effect size (g = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.61–0.91, p < 0.001). At follow-ups, 12 comparisons showed that evidence-based psychotherapies outperformed control conditions on primary outcome measures at follow-ups with a small effect size (g = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.00–0.53, p = 0.05).

Within psychotherapy comparisons, pill placebo-controlled studies had the highest effect size (n = 3, g = 1.44, 95% CI: 0.94–1.94, p < 0.001), followed by WL controls (n = 22, g = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.73–1.08, p < 0.001), psychological placebo (n = 10, g = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.25–0.69, p < 0.001), and TAU (n = 5, g = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.05–0.71, p < 0.05; in Wetherell et al., 2003, the psychological placebo and waitlist control group comparisons were each included in this analysis).

Efficacy of psychotherapy versus control conditions on secondary outcome measures

This analysis included 29 comparisons. Evidence-based psychotherapies outperformed control conditions on secondary outcome measures at posttreatment with a medium effect size (g = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.49–0.79, p < 0.001). At follow-ups, 8 comparisons showed that evidence-based psychotherapies outperformed control conditions on secondary outcome measures at follow-ups with a small effect size (g = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.06–0.49, p = 0.01).

Efficacy of pharmacotherapy versus control conditions on primary outcome measures

This analysis included 43 comparisons. Consistent with prediction, pharmacotherapy outperformed control conditions on primary outcome measures at posttreatment with a small effect size (g = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.30–0.47, p < 0.001). There were no pharmacotherapy studies with data on follow-up measures of the primary outcome available. All included medication comparisons used pill placebos as a control.

Efficacy of pharmacotherapy versus control conditions on secondary outcome measures

This analysis included 11 comparisons. Pharmacotherapy outperformed control conditions on secondary outcome measures at posttreatment with a medium effect size (g = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.21–0.97, p < 0.01). There were no pharmacotherapy studies with follow-up data of depression measures available.

Moderators

Moderator analyses were conducted on psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy separately. Although outliers had minor effect on pooled effect size estimates, they were removed from moderator analyses due to their substantial leverage and influence on regression results.

Mean age of the sample was a significant moderator of psychotherapy outcomes. A lower mean age predicted a larger treatment effect size in psychotherapy (β = −0.013, p < 0.05). This difference was also demonstrated when comparing psychotherapeutic outcomes for adult and elderly populations categorically (Q = 5.16, df = 1, p < 0.05), with studies involving non-elderly adult participants showing a larger effect size (g = 0.87) than studies involving older adult participants (g = 0.47). Mean age was not associated with outcome in medication studies (p > 0.05).

There was no significant relationship between effect size and treatment dose (number of sessions or medication dosage), treatment quality, year of publication, fixed versus flexible dose, percent comorbidity, percent female, or pretreatment severity (all p > 0.10).

Publication bias: “the file drawer problem”

Because nonsignificant studies tend not to be published, there may be a discrepancy in results between the studies that are retrievable and all studies that have been conducted. Unavailable negative results may lead to overestimate the true effect size. Rosenthal and colleagues have termed this phenomenon “the file drawer problem” (Rosenthal, 1991).

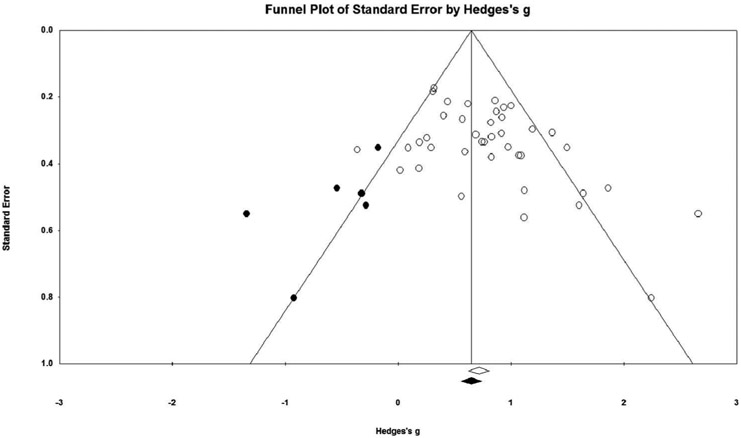

Because pooled effect sizes in pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy domains differed substantially, publication bias was examined separately in each. A funnel plot revealed asymmetry in psychotherapy studies (Egger’s intercept = 1.93, p < 0.01; Figure 3), and the Duval and Tweedie (2000) trim and fill procedure imputed 5 studies for an adjusted effect size estimate of 0.66. A funnel plot in pharmacotherapy studies did not reveal asymmetry according to Egger’s intercept and a trim and fill procedure did not impute any studies or adjust the effect size estimate.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot for psychotherapy studies with imputed studies and adjusted effect size.

Discussion

Main findings

The current study provides an updated meta-analysis including 79 studies that showed similar effect sizes to previous meta-analyses. The overall effect size of evidence-based psychotherapy for GAD on primary GAD outcomes (g = 0.76, n = 39) was comparable to the previous meta-analysis on psychotherapy (g = 0.80, n = 31; Cuijpers et al., 2016). Additionally, the effect size for medication for GAD (g = 0.38, n = 43) was comparable to a previous meta-analysis for medication (d = 0.39, n = 21; Hidalgo et al., 2007).

While it may seem possible to draw the conclusion that psychotherapy has a larger effect on GAD symptoms than pharmacotherapy, this is not supported for more than one reason. First, the two treatment modalities use different control types. In the current study, all pharmacotherapy trials used a pill placebo as a comparison, while psychotherapy studies often had a waitlist control. Although in this analysis the three pill placebo controlled psychotherapy studies had a higher effect size than waitlist controlled studies, this is likely a fluke and underpowered, as a larger meta-analysis of CBT for anxiety disorders showed that effects were large for waitlist conditions and small to medium for pill placebo comparisons (n = 144 trials; Cuijpers et al., 2016). If a pill placebo is a much more stringent control condition than WL, this would have contributed to this apparent difference in effect size. Next, psychotherapy studies showed evidence of publication bias. Finally, a network meta-analysis including head-to-head treatment comparisons in addition to treatments versus control conditions would provide a more comprehensive dataset for comparing treatments.

Most moderators did not show evidence of influence. This corroborates previous conclusions (Schneider et al., 2015). However, younger age of the study sample was associated with higher effect size in psychotherapy studies.

Implications

Some evidence suggests that patients strongly prefer psychological treatment to medication, with one meta-analytic review showing a three-fold preference (McHugh, Whitton, Peckham, Welge, & Otto, 2013). Because the efficacy appears to be at least comparable, increased access to psychological treatment is necessary to provide sufficient treatment to individuals with GAD.

Next, moderator analyses showed that mean age of the sample was a significant moderator in the psychotherapy studies, such that younger mean age of the sample was associated with more symptom improvement in psychotherapy. This difference was also evident when comparing adult populations and elderly populations categorically. Although this is not direct evidence that younger age was the cause of receptiveness to psychotherapy, this is consistent with findings from a number of investigators that treatments for anxiety disorders are not as effective for older people relative to younger people (Gonçalves & Byrne, 2012; Gould et al., 2012; Hendriks et al., 2008; Pinquart & Duberstein, 2007; Wetherell et al., 2013).

Limitations

Notably, although psychotherapy yielded larger effect sizes than medication, this metaanalysis suggests that control type may contribute to this apparent difference. Publication bias in psychotherapy studies might also contribute to the difference in psychotherapy and medication effect sizes. Therefore, this meta-analysis indicates that although controlled psychotherapy studies may have larger effect sizes than medication studies for GAD, the methodologies in these studies are not equivalent enough to draw firm conclusions. Studies that compare medication and psychotherapy side-by-side would be more informative to this end. Lastly, given the relatively small number of studies incorporating follow-up measures of GAD symptoms (12 total included), as well as the variability of follow-up times (2 weeks to 3 years), more evidence is necessary to draw conclusions about psychotherapy and medication long-term outcomes following treatment.

Summary

This meta-analysis drew from 79 RCT with 11,002 participants to examine effects of psychotherapy and pharmacological treatments for GAD. Both types of interventions significantly improved both primary GAD outcomes and secondary depression outcomes. The mean effect size for psychotherapy was g = 0.76 and for pharmacotherapy was g = 0.38. However, control type (placebo v. TAU and WL) and publication bias cast doubt on the validity of the comparison of the effect sizes. Age moderated the primary GAD outcomes in psychotherapy, with younger age predicting better treatment response.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

N refers to the total number of participants included in each primary comparison (single treatment group + single placebo), respectively, from pretreatment to posttreatment.

Direction of comparison refers to the group with the superior primary outcome at posttreatment.

References

* Studies included in the meta-analysis are denoted with an asterisk.

- *.Alaka KJ, Noble W, Montejo A, Dueñas H, Munshi A, Strawn JR, … Ball S (2014). Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in the treatment of older adult patients with generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(9), 978–986. doi: 10.1002/gps.4088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Aliyev NA, & Aliyev ZN (2008). Valproate (depakine-chrono) in the acute treatment of outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder without psychiatric comorbidity: Randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. European Psychiatry : the Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 23(2), 109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Allgulander C, Dahl AA, Austin C, Morris PL, Sogaard JA, Fayyad R, … Clary CM (2004). Efficacy of sertraline in a 12-week trial for generalized anxiety disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(9), 1642–1649. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Allgulander C, Hackett D, & Salinas E (2001). Venlafaxine extended release (ER) in the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder: Twenty-four-week placebo-controlled dose-ranging study. The British Journal of Psychiatry : the Journal of Mental Science, 179(1), 15–22. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- *.Bakhshani N, Lashkaripour K, & Sadjadi S (2007). Effectiveness of short term cognitive behavior therapy in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. International Journal of Medical Sciences. Retrieved from http://www.docsdrive.com/pdfs/ansinet/jms/2007/1076-1081.pdf [Google Scholar]

- *.Ball SG, Lipsius S, & Escobar R (2015). Validation of the geriatric anxiety inventory in a duloxetine clinical trial for elderly adults with generalized anxiety disorder. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(9), 1533–1539. doi: 10.1017/S1041610215000381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Barlow DH, Rapee RM, & Brown TA (1992). Behavioral treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy, 23(4), 551–570. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80221-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, & Steer RA (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: The Beck Anxiety Inventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1(56), 893–897. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80221-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory: Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, & Erbaugh J (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Bidzan L, Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobsen P, Yan M, & Sheehan DV (2012). Vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) in generalized anxiety disorder: Results of an 8-week, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. European Neuropsychopharmacology : the Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 22(12), 847–857. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biostat GD (2014). Comprehensive meta-analysis (version 3.3070 - November 21, 2014). Engelwood, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- *.Bonne O, Shemer Y, Gorali Y, Katz M, & Shalev AY (2003). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of classical homeopathy in generalized anxiety disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64(3), 282–287. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v64n0309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, & Rothstein H (2007). Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, England: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- *.Borkovec TD, Mathews AM, Chambers A, Ebrahimi S, Lytle R, & Nelson R (1987). The effects of relaxation training with cognitive or nondirective therapy and the role of relaxation-induced anxiety in the treatment of generalized anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(6), 883–888. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.55.6.883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Borkovec TD, & Costello E (1993). Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 611–619. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.4.611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Bowman D, Scogin F, Floyd M, Patton E, & Gist L (1997). Efficacy of self-examination therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 44 (3), 267–273. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.44.3.267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brawman-Mintzer O, Knapp RG, Rynn M, Carter RE, & Rickels K (2006). Sertraline treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(6), 874–881. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brenes GA, Danhauer SC, Lyles MF, Hogan PE, & Miller ME (2015). Telephone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy and telephone-delivered nondirective supportive therapy for rural older adults with generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry (Chicago, Ill.), 72(10), 1012–1020. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce SE, Yonkers KA, Otto MW, Eisen JL, Weisberg RB, Pagano M, … Keller MB (2005). Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on recovery and recurrence in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder: A 12-year prospective study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(6), 1179–1187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Butler G, Fennell M, Robson P, & Gelder M (1991). Comparison of behavior therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 167–175. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- *.Connor KM, & Davidson JRT (2002). A placebo-controlled study of kava kava in generalized anxiety disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 17(4), 185–188. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200207000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Cristea IA, Karyotaki E, Reijnders M, & Huibers MJ (2016). How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta-analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 15(3), 245–258. doi: 10.1002/wps.20346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Dahlin M, Andersson G, Magnusson K, Johansson T, Sjögren J, Håkansson A, … Carlbring P (2016). Internet-delivered acceptance-based behaviour therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Darcis T, Ferreri M, Natens J, Burtin B, & Deram P (1995). A multicentre double-blind placebo-controlled study investigating the anxiolytic efficacy of hydroxyzine in patients with generalized anxiety. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 10(3), 181–187. doi: 10.1002/hup.470100303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Davidson JR, DuPont RL, Hedges D, & Haskins JT (1999). Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of venlafaxine extended release and buspirone in outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60(8), 528–535. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v60n0805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Davidson JR, Bose A, Korotzer A, & Zheng H (2004). Escitalopram in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: Double-blind, placebo controlled, flexible-dose study. Depression and Anxiety, 19(4), 234–240. doi: 10.1002/da.10146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Davidson JR, Wittchen HU, Llorca PM, Erickson J, Detke M, Ball SG, & Russell JM (2008). Duloxetine treatment for relapse prevention in adults with generalized anxiety disorder: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial. European Neuropsychopharmacology : the Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 18(9), 673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Dugas MJ, Ladouceur R, Léger E, Freeston MH, Langolis F, Provencher MD, & Boisvert JM (2003). Group cognitive-behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: Treatment outcome and long-term follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(4), 821–825. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Dugas MJ, Brillon P, Savard P, Turcotte J, Gaudet A, Ladouceur R, … Gervais NJ (2010). A randomized clinical trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and applied relaxation for adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy, 41(1), 46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Durham RC, Murphy T, Allan T, Richard K, Treliving LR, & Fenton GW (1994). Cognitive therapy, analytic psychotherapy and anxiety management training for generalised anxiety disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 165(3), 315–323. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.3.315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, & Tweedie R (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Feltner DE, Crockatt JG, Dubovsky SJ, Cohn CK, Shrivastava RK, Targum SD, … Pande AC (2003). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose, multicenter study of pregabalin in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 23(3), 240–249. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000084032.22282.ff [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Gelenberg AJ, Lydiard RB, Rudolph RL, Aguiar L, Haskins JT, & Salinas E (2000). Efficacy of venlafaxine extended-release capsules in nondepressed outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder: A 6-month randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 283(23), 3082–3088. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.23.3082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Gommoll C, Durgam S, Mathews M, Forero G, Nunez R, Tang X, & Thase ME (2015). A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose phase III study of vilazodone in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 32(6), 451–459. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.23.3082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves DC, & Byrne GJ (2012). Interventions for generalized anxiety disorder in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(1),1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RL, Coulson MC, & Howard RJ (2012). Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in older people: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(2), 218–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03824.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hackett D, Haudiquet V, & Salinas E (2003). A method for controlling for a high placebo response rate in a comparison of venlafaxine XR and diazepam in the short-term treatment of patients with generalised anxiety disorder. British European Psychiatry, 18(4), 182–187. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(03)00046-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M (1959). The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 32(1), 50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 23, 56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartford J, Kornstein S, Liebowitz M, Pigott T, Russell J, Detke M, & Erickson J (2007). Duloxetine as an snri treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: results from a placebo and active-controlled trial. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 22(3), 167–174. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32807fb1b2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, & Olkin I (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando FL: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks GJ, Oude Voshaar RC, Keijsers GPJ, Hoogduin CAL, & Van Balkom AJLM (2008). Cognitive-behavioural therapy for late-life anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 117(6), 403–411. doi: 10.11n/j.1600-0447.2008.01190.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo RB, Tupler LA, & Davidson JRT (2007). An effect-size analysis of pharmacologic treatments for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 21(8), 864–872. doi: 10.1177/0269881107076996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, & Green S (editors). (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]). The Cochrane Collaboration. Retrieved from www.handbook.cochrane.org [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, & Altman DG (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal, 327(7414), 557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hoge EA, Bui E, Marques L, Metcalf CA, Morris LK, Robinaugh DJ, … Simon NM (2013). Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: Effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(8), 786–792. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopko DR, Stanley MA, Reas DL, Wetherell JL, Beck JG, Novy DM, & Averill PM (2003). Assessing worry in older adults: Confirmatory factor analysis of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire and psychometric properties of an abbreviated model. Psychological Assessment, 15(2), 173–183. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.2.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hoyer J, Beesdo K, Gloster AT, Runge J, Höfler M, & Becker ES (2009). Worry exposure versus applied relaxation in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78(2), 106–115. doi: 10.1159/000201936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Johnston L, Titov N, Andrews G, Spence J, & Dear BF (2011). A RCT of a transdiagnostic internet-delivered treatment for three anxiety disorders: Examination of support roles and disorder-specific outcomes. PloS one, 6(11), e28079. doi: 10.137/journal.pone.0028079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GN, Ames SC, Jeffries SK, Scarinci IC, & Brantley PJ (2001). Utilization of medical services and quality of life among low-income patients with generalized anxiety disorder attending primary care clinics. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 31 (2), 183–198. doi: 10.2190/2X44-CR14-YHJC-9EQ3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Jones SL, Hadjistavropoulos HD, & Soucy JN (2016). A randomized controlled trial of guided internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for older adults with generalized anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 37, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anxdis.2015.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kasper S, Herman B, Nivoli G, Van Ameringen M, Petralia A, Mandel FS,… Bandelow B (2009). Efficacy of pregabalin and venlafaxine-XR in generalized anxiety disorder: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled 8-week trial. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 24 (2), 87–96. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32831d7980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, DuPont RL, Berglund P, & Wittchen HU (1999). Impairment in pure and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and major depression at 12 months in two national surveys. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(12), 1915–1923. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.12.1915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Wittchen H-U (2012). Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(3), 169–184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Koszycki D, Raab K, Aldosary F, & Bradwejn J (2010). A multifaith spiritually based intervention for generalized anxiety disorder: A pilot randomized trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(4), 430–441. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2001). The phq-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lader M, & Scotto JC (1998). A multicentre double-blind comparison of hydroxyzine, buspirone and placebo in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Psychopharmacology, 139(4), 402–406. doi: 10.1007/s0021300507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ladouceur R, Dugas MJ, Freeston MH, Léger E, Gagnon F, & Thibodeau N (2000). Efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: Evaluation in a controlled clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(6), 957–964. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Leichsenring F, Salzer S, Jaeger U, Kächele H, Kreische R, Leweke F, … Sc E (2009). Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy in generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized, controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(8), 875–881. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lenze EJ, Rollman BL, Shear MK, Dew MA, Pollock BG, Ciliberti C, … Andreescu C (2009). Escitalopram for older adults with generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 301(3), 295–303. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Levy Berg A, Sandell R, & Sandahl C (2009). Affect-focused body psychotherapy in patients with generalized anxiety disorder: Evaluation of an integrative method. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 19(1), 67–85. doi: 10.1037/a0015324 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Linden M, Zubraegel D, Baer T, Franke U, & Schlattmann P (2005). Efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapy in generalized anxiety disorders. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 74(1), 36–42. doi: 10.1159/000082025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Llorca PM, Spadone C, Sol O, Danniau A, Bougerol T, Corruble E, … Servant D (2002). Efficacy and safety of hydroxyzine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A 3-month double-blind study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 63(11), 1020–1027. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v63n1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobsen PL, Chen Y, & Simon JS (2014). A randomised, doubleblind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced study of the efficacy and tolerability of vortioxetine in the acute treatment of adults with generalised anxiety disorder. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 68(1), 49–59. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak MD, Lage MJ, Dunayevich E, Russell JM, Bowman L, Landbloom RP, & Levine LR (2005). The cost of treating anxiety: The medical and demographic correlates that impact total medical costs. Depression and Anxiety, 21(4), 178–184. doi: 10.1002/da.20074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, Welge JA, & Otto MW (2013). Patient preference for psychological vs. pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(6), 595–602. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, & Borkovec TD (1990). Development and validation of the Penn State Worry questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(6), 487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Möller HJ, Volz HP, Reimann IW, & Stoll KD (2001). Opipramol for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A placebo-controlled trial including an alprazolam-treated group. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 21(1), 59–65. doi: 10.1097/00004714200102000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Mohlman J, Gorenstein EE, Kleber M, de Jesus M, Gorman JM, & Papp LA (2003). Standard and enhanced cognitive-behavior therapy for late-life generalized anxiety disorder: Two pilot investigations. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(1), 24–32. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200301000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Montgomery SA, Tobias K, Zornberg GL, Kasper S, & Pande AC (2006). Efficacy and safety of pregabalin in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A 6-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of pregabalin and venlafaxine. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(5), 771–782. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, & Åsberg M (1979). A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry, 134, 382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Przeworski A, Fisher AJ, & Borkovec TD (2010). Diagnostic comorbidity in adults with generalized anxiety disorder: Impact of comorbidity on psychotherapy outcome and impact of psychotherapy on comorbid diagnoses. Behavior Therapy, 41(1), 59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Pande AC, Crockatt JG, Feltner DE, Janney CA, Smith WT, Weisler R, … Liu-Dumaw M (2003). Pregabalin in generalized anxiety disorder: A placebo-controlled trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(3), 533–540. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Park DM, Kim SH, Park YC, Kang WC, Lee SR, & Jung IC (2014). The comparative clinical study of efficacy of Gamisoyo-San (Jiaweixiaoyaosan) on generalized anxiety disorder according to differently manufactured preparations: Multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 158, 11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Paxling B, Almlöv J, Dahlin M, Carlbring P, Breitholtz E, Eriksson T, & Andersson G (2011). Guided internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 40(3),159–173. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.576699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, & Duberstein PR (2007). Treatment of anxiety disorders in older adults with anxiety disorder: A meta-analytic comparison of behavioral and pharmacological interventions. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(8), 639–651. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31806841c8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Pollack MH, Zaninelli R, Goddard A, McCafferty JP, Bellew KM, Burnham DB, & Iyengar MK (2001). Paroxetine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: Results of a placebo-controlled, flexible-dosage trial. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62 (5), 350–357. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v62n0508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Pollack MH, Tiller J, Xie F, & Trivedi MH (2008). Tiagabine in adult patients with generalized anxiety disorder: Results from 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group studies. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 28(3), 308–316. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318172b45f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Power KG, Simpson RJ, Swanson V, Wallace LA, Feistner ATC, & Sharp D (1990). A controlled comparison of cognitive-behaviour therapy, diazepam, and placebo, alone and in combination, for the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 4 (4), 267–292. doi: 10.1016/0887-6185(90)90026-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Power KG, Simpson RJ, Swanson V, & Wallace LA (1990). A controlled comparison of pharmacological and psychological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in primary care. The British Journal of General Practice : the Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 40(336), 289–294. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2081065 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revicki DA, Travers K, Wyrwich KW, Svedsater H, Locklear J, Mattera MS, … Montgomery S (2012). Humanistic and economic burden of generalized anxiety disorder in North America and Europe. Journal of Affective Disorders, 140(2), 103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rezvan S, Baghban I, Bahrami F, & Abedi M (2008). A comparison of cognitive-behavior therapy with interpersonal and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 21(4), 309–321. doi: 10.1080/09515070802602096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rickels K, Pollack MH, Sheehan DV, & Haskins JT (2000). Efficacy of extended-release venlafaxine in nondepressed outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder. American Journal Of Psychiatry, 157(6), 968–974. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rickels K, Zaninelli R, McCafferty J, Bellew K, Iyengar M, & Sheehan D (2003). Paroxetine treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(4), 749–756. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rickels K, Pollack MH, Feltner DE, Lydiard RB, Zimbroff DL, Bielski RJ, … Pande AC (2005). Pregabalin for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A 4-week, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pregabalin and alprazolam. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(9), 1022–1030. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Robinson E, Titov N, Andrews G, McIntyre K, Schwencke G, & Solley K (2010). Internet treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistance. PloS one, 5(6), e10942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.001942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Roemer L, Orsillo SM, & Salters-Pedneault K (2008). Efficacy of an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: Evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(6), 1083–1089. doi: 10.1037/a0012720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R (1991). Meta-analytic procedures for social research. London, UK: Sage PublicationsSage. [Google Scholar]

- *.Rothschild AJ, Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobsen P, Yan M, & Sheehan DV (2012). Vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) 5 mg in generalized anxiety disorder: Results of an 8-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in the United States. European Neuropsychopharmacology : the Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 22(12), 858–866. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Sarris J, Stough C, Bousman CA, Wahid ZT, Murray G, Teschke R, … Schweitzer I (2013). Kava in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 33(5), 643–648. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318291be67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RL, Arch JJ, & Wolitzky-Taylor KB (2015). The state of personalized treatment for anxiety disorders: A systematic review of treatment moderators. Clinical Psychology Review, 38, 39–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, & Lushene RE (1970). The state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, Calif: Consulting Psychologists Press Inc; Retrieved from https://ubir.buffalo.edu/xmlui/handle/10477/2895 [Google Scholar]

- *.Stanley MA, Beck JG, & Glassco JD (1996). Treatment of generalized anxiety in older adults: A preliminary comparison of cognitive-behavioral and supportive approaches. Behavior Therapy, 27(4), 565–581. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(96)80044-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Stanley MA, Hopko DR, Diefenbach GJ, Bourland SL, Rodriguez H, & Wagener P (2003). Cognitive-behavior therapy for late-life generalized anxiety disorder in primary care: Preliminary findings. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry : Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(1), 92–96. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200301000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Stanley MA, Beck JG, Novy DM, Averill PM, Swann AC, Diefenbach GJ, & Hopko DR (2003). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of late-life generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(2), 309–319. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Stanley MA, Wilson NL, Novy DM, Rhoades HM, Wagener PD, Greisinger AJ,… Kunik ME (2009). Cognitive behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder among older adults in primary care: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 301(14), 1460–1467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Stein DJ, Ahokas AA, & de Bodinat C (2008). Efficacy of agomelatine in generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 28(5), 561–566. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318184ff5b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Stein DJ, Ahokas A, Márquez MS, Höschl C, & Olivier V (2014). Original research agomelatine in generalized anxiety disorder: An active comparator and placebo-controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(4), 362–368. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Stein DJ, Ahokas A, Jarema M, Avedisova AS, Vavrusova L, Chaban O, … de Bodinat C(2017). Efficacy and safety of agomelatine (10 or 25 mg/day) in non-depressed out-patients with generalized anxiety disorder: A 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 27(5), 526–537. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Titov N, Andrews G, Robinson E, Schwencke G, Johnston L, Solley K, & Choi I(2009). Clinician-assisted Internet-based treatment is effective for generalized anxiety disorder: Randomized controlled trial. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43(10), 905–912. doi: 10.1080/00048670903179269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Titov N, Andrews G, Johnston L, Robinson E, & Spence J (2010). Transdiagnostic Internet treatment for anxiety disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(9), 890–899. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.van der Heiden C, Muris P, & van der Molen HT (2012). Randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness of metacognitive therapy and intolerance-of-uncertainty therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(2), 100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Wetherell JL, Gatz M, & Craske MG (2003). Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 31–40. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Wetherell JL, Ayers CR, Sorrell JT, Thorp SR, Nuevo R, Belding W, … Unützer J (2009). Modular psychotherapy for anxiety in older primary care patients. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(6), 483–492. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181a31fb5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell JL, Petkus AJ, Thorp SR, Stein MB, Chavira DA, Campbell-Sills L, … Roy-Byrne P (2013). Age differences in treatment response to a collaborative care intervention for anxiety disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 203(1), 65–72. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.118547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.White J, Keenan M, & Brooks N (1992). Stress control: A controlled comparative investigation of large group therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 20(2), 97–113. doi: 10.1017/S014134730001689X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Wu WY, Wang G, Ball SG, Desaiah D, & Ang QQ (2011). Duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of patients with generalized anxiety disorder in China. Chinese Medical Journal, 124(20), 3260–3268. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2011.20.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Zinbarg RE, Lee JE, & Yoon KL (2007). Dyadic predictors of outcome in a cognitive-behavioral program for patients with generalized anxiety disorder in committed relationships: A “spoonful of sugar” and a dose of non-hostile criticism may help. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(4), 699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]