Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: chronic critical illness, intensive care, persistent critical illness, process of care, quality indicator

Objectives:

To identify actionable processes of care, quality indicators, or performance measures and their evidence base relevant to patients with persistent or chronic critical illness and their family members including themes relating to patient/family experience.

Data Sources:

Two authors independently searched electronic, systemic review, and trial registration databases (inception to November 2016).

Study Selection:

We included studies with an ICU length of stay of greater than or equal to 7 days as an inclusion criterion and reported actionable processes of care; quality improvement indicators, measures, or tools; or patient/family experience. We excluded case series/reports of less than 10 patients.

Data Extraction:

Paired authors independently extracted data and performed risk of bias assessment.

Data Synthesis:

We screened 13,130 references identifying 114 primary studies and 102 relevant reviews. Primary studies reported data on 24,252 participants; median (interquartile range) sample size of 70 (32–182). We identified 42 distinct actionable processes of care, the most commonly investigated related to categories of 1) weaning methods (21 studies; 27 reviews); 2) rehabilitation, mobilization, and physiotherapy (20 studies; 40 reviews); and 3) provision of information, prognosis, and family communication (14 studies; 11 reviews). Processes with limited evidence were generally more patient-centered categories such as communication, promotion of sleep, symptom management, or family support. Of the 21 randomized controlled trials, only two were considered at low risk of bias across all six domains, whereas just two cohort studies and one qualitative study were considered of high quality.

Conclusions:

We identified 42 distinct actionable processes of care relevant to patients with persistent or chronic critical illness and their families, with most frequently studied processes relating to weaning, rehabilitation/mobilization, and family communication. Qualitative studies highlighted the need to address psychologic needs and distressing symptoms as well as enabling patient communication. Our findings are informative for clinicians and decision-makers when planning high-quality patient and family-focused care.

Within ICUs in developed countries, 5–10% of critically ill adults transition from acute critical illness to a state of persistent and in some cases chronic critical illness (1–4). Persistent critical illness is characterized by some degree of clinical instability associated with persistent low-intensity inflammation and organ failure (5) that may not be directly attributable to the original reason for ICU admission (6). Patients with chronic critical illness continue to require prolonged ICU stays and, in most cases, a prolonged need for mechanical ventilation (7–9). Incidence rates are increasing, costs to the healthcare budget are estimated to be $25 billion annually in the United States alone (10), and hospital mortality remains high for these patients (11). With an uncertain disease trajectory, extreme symptom load and profound physical, neuropsychologic, and cognitive deficits, patient burden is substantial (8, 12). Family members also experience significant emotional and physical caregiving and financial burden (13, 14).

Patients with persistent or chronic critical illness require adaption of their clinical management plan and overall goals of care to a focus on rehabilitation, symptom relief, discharge planning, and in some cases, ventilation discontinuation, or end-of-life care (15). Realization of these goals requires development and implementation of strategies focused on actionable processes of care (i.e., those processes over which clinicians and decision-makers have direct control and are able to take action on) that will improve patient and family experience and clinical outcomes (5, 16). However, strategies such as weaning and mobilization protocols, which can be considered actionable processes of care, infrequently include guidance specific to patients with persistent or chronic critical illness (17). Daily checklists, which reinforce delivery of actionable processes of care, are focused entirely on acutely ill patients and thus may not include items likely to be considered important to patients experiencing long ICU stays, such as communication aids, family meetings, and symptom management (18).

Therefore, to inform the development of quality improvement tools for patients with persistent or chronic critical illness and family, we sought to identify actionable processes of care, performance measures, and quality indicators including reports of patient and family experience specific to the management of persistent and chronic critical illness described in the current evidence base.

METHODS

We conducted this review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses Protocol (PRISMA-P) guidelines (19) and completed a PRISMA-P checklist. We registered the protocol on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: 42016052715 and previously published our protocol (20).

Study Identification

Using an iteratively developed search strategy (supplementary material, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A4) informed by an experienced information specialist, we searched (March 1980 to November 2016): MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, PROSPERO, and the Joanna Briggs Institute. We searched major guideline sites (e.g., Canadian Medical Association Infobase, National Guideline Clearinghouse) for clinical practice guidelines and policy documents, websites of relevant professional societies for practice recommendations relevant to our population of interest, and examined reference lists of relevant studies/reviews. We searched http://apps.who.int/trialsearch website for unpublished and ongoing trials.

Inclusion Criteria

Eligible studies had to report on actionable or modifiable processes of care, performance indicators, quality improvement measures or tools, or patient/family experience specific to adults described as persistent critical illness, chronic critical illness, prolonged mechanical ventilation or a study population admitted to a specialized weaning facility, long-term acute care hospital (LTACH), or respiratory high dependency unit. Due to recognized variability in definitions (21), we included only those studies using an ICU length of stay of greater than or equal to 7 days as a study inclusion criterion to reflect the consensus definition used by Medicare and Medicaid in the United States (22). Studies were eligible regardless of study design with the exception of case series/reports of less than 10 patients. We included observational cohorts that reported on presence of conditions such as polyneuropathy, hypothyroidism, or depression as we considered the need to assess for such conditions would comprise an initial step of an actionable care process. We excluded animal-only studies, opinion pieces (e.g., editorials, letters) and for practical reasons, non-English language studies.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to develop a list of evidence-based actionable processes of care to be considered by clinicians and decision-makers for delivery of quality care in daily practice for patients experiencing persistent or chronic critical illness and their family members. Secondary objectives were to identify quality improvement tools, quality indicators, or performance measures relevant to our population of interest; qualitatively derived themes related to patient and family experience.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two authors (L.R., L.I.) independently screened abstracts for eligibility. When necessary, a third reviewer (L.A. or B.C.) arbitrated consensus. Two authors independently extracted data using a standardized form; a third author (L.R.) checked all extraction for accuracy. We extracted data on country, care venue type and characteristics, patient characteristics, descriptions of actionable care processes or study interventions dependent on study design, and descriptions of quality indicators and performance measures. We extracted quantitative and qualitative study results including qualitative themes related to patient and family experience. Two investigators (L.R., L.I.) independently reviewed the extracted actionable care processes/interventions to develop a list of categories and independently assigned primary studies to categories. The study team then reviewed and confirmed agreement. We reviewed relevant narrative and systematic reviews and determined actionable processes of care described in these reviews.

Study Quality Assessment

For randomized and quasi-randomized studies, two investigators independently assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (23). The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network checklists (24) were used for cohort and case-control studies. We used a modified 2014 Critical Appraisal Skills Programme quality assessment tool for qualitative studies (25) and, as this tool does not consider the more conceptual or theoretical aspects of qualitative studies, we also assessed additional criteria outlined by Popay et al (26).

Data Analysis

We summarized study and patient participant characteristics reported as categorical variables using counts and proportions and continuous variables as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). We calculated counts and proportions of categories of actionable processes identified in primary studies and relevant reviews. Due to a priori anticipated heterogeneity in study design, processes of care, interventions, quality indicators, and measures, we did not perform meta-analyses, subgroup or sensitivity analyses, or examine publication bias. For qualitative studies, we generated a table of author reported themes, and subthemes and undertook content analysis of these themes (27, 28) to quantify common categories and themes within these categories leading to identification of additional actionable processes of care. We categorized data using the conceptual framework of structure, process, and outcomes developed by Donabedian (29).

RESULTS

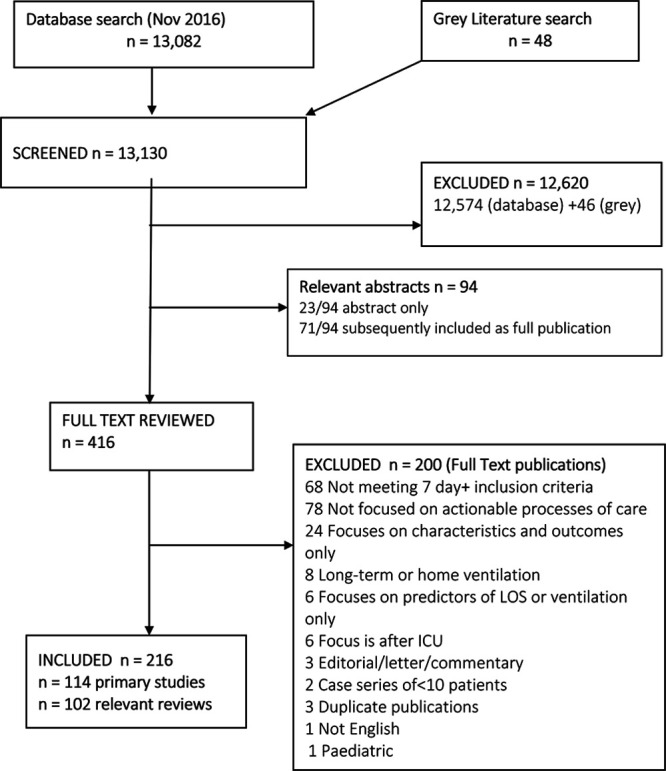

We screened 13,130 references, excluded 12,820 and included 114 primary studies, 102 reviews, and 94 abstracts (71 subsequently published as full manuscripts). Search results are presented using a PRISMA study flow diagram (30) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Citation screening and study selection: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses flow diagram. LOS = length of stay.

Study and Participant Characteristics

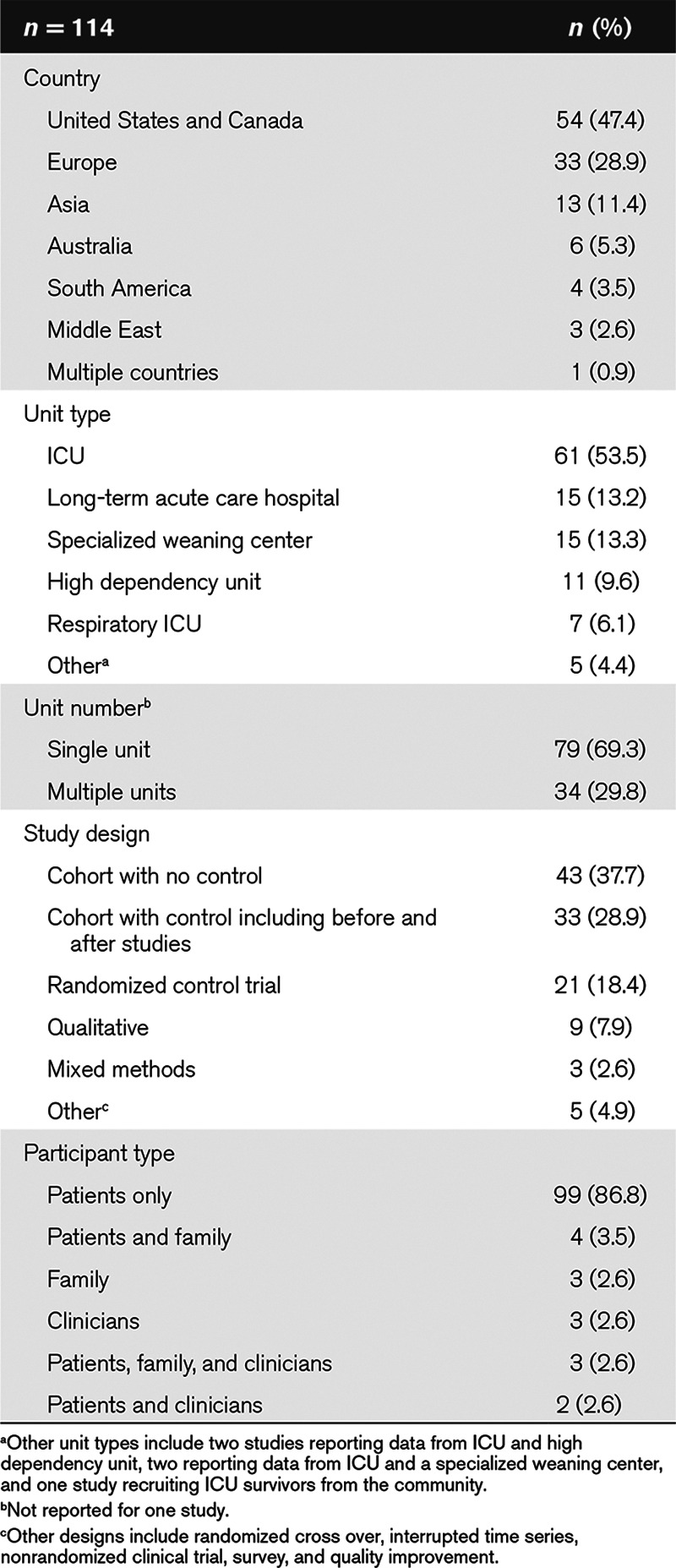

The 114 primary studies (for bibliography, see Supplementary Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A4) reported data on 24,251 participants with a median (IQR) sample size of 70 (32–182). Most studies were from North America (48%), were conducted in ICUs (54%) as opposed to other care environments such as LTACHs or specialized weaning centers, were single-center studies (70%), and used a cohort design without a comparator group (37%) (Table 1). We identified nine qualitative or mixed methods studies reporting themes relating to patient and family experience.

TABLE 1.

Study Characteristics

Of the 99 studies including only patient participants, the reported mean (sd) age ranged from 40 (31) to 79 (32) years, with a median (IQR) of 60% (53–68%) male participants, and a median (IQR) of 75% (57–100%) admitted to the participating unit for medical reasons. Of the 42 studies reporting Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (33) scores at admission, mean (sd) scores ranged from 12 (4) to 27 (7). (Supplementary Table 1 [Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A4] provides unit characteristics/descriptors of individual studies).

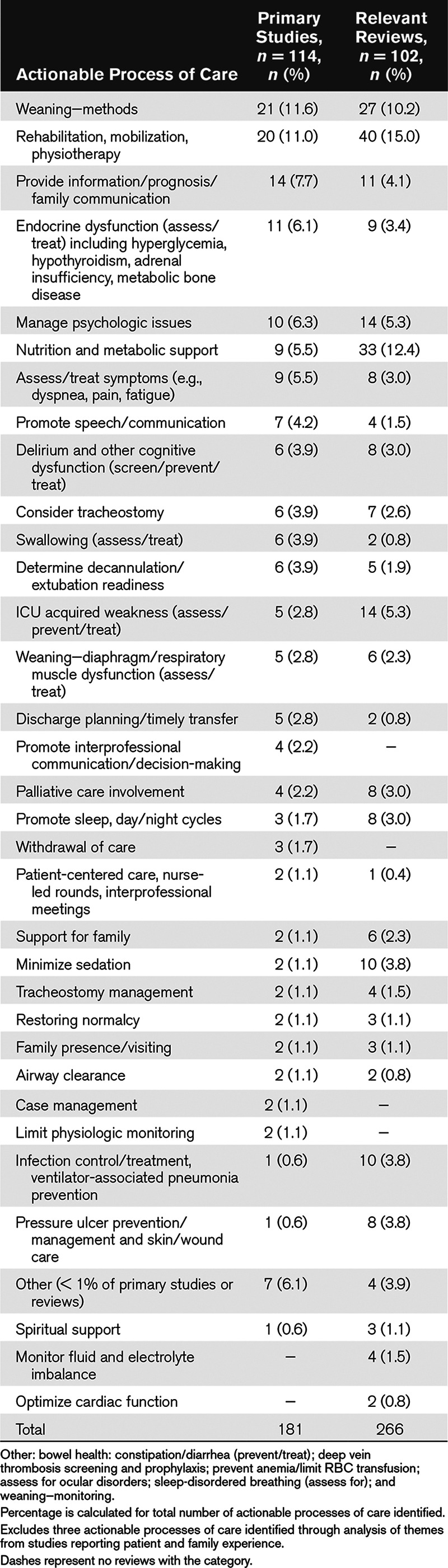

Actionable Processes of Care

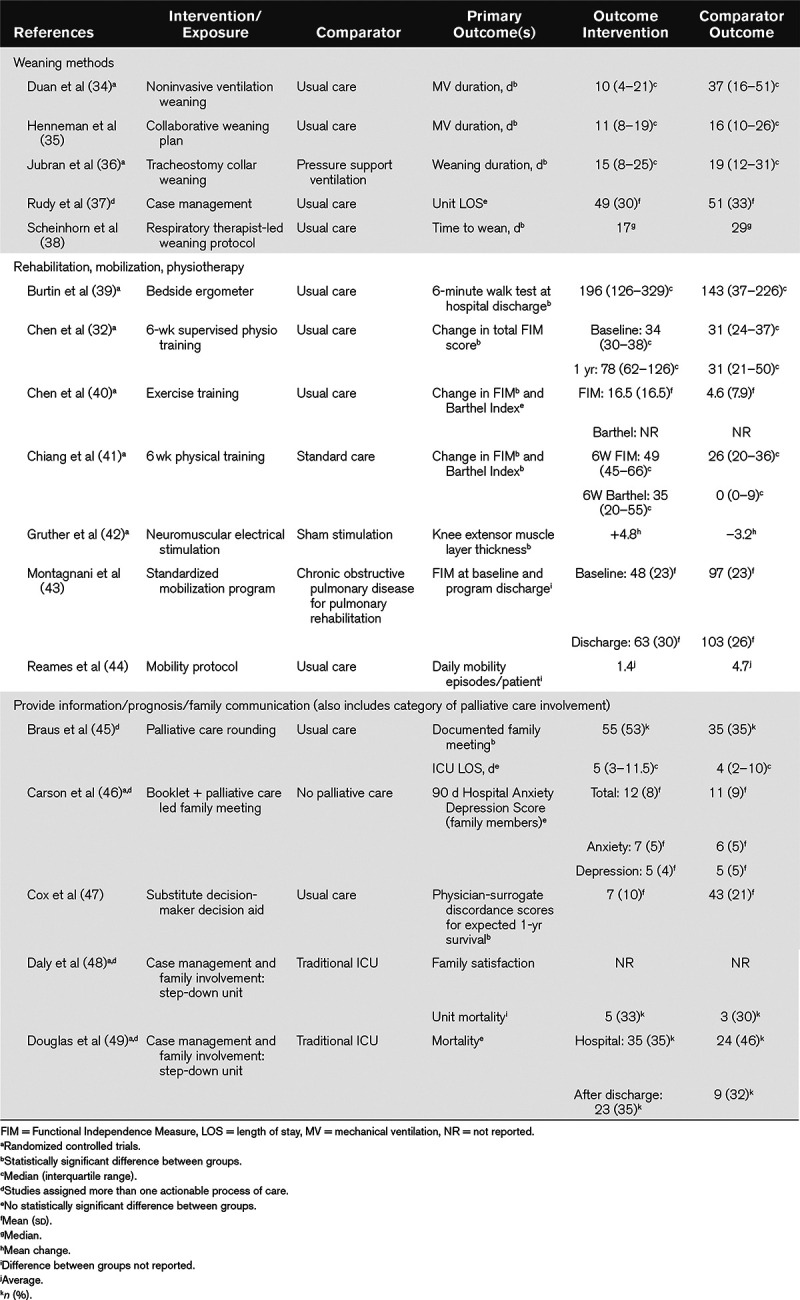

We identified 42 distinct categories of actionable processes of care of relevance to the delivery of care for patients with persistent or chronic critical illness. These comprised 37 from the 114 primary studies, including three identified although content analysis of patient and family experience. Five additional categories were reported in narrative reviews only (Table 2; and Supplementary Table 2 [Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A4] for actionable process categories and description of processes from individual studies). Most commonly occurring categories from studies using quantitative methods were: 1) weaning methods; 2) rehabilitation, mobilization, and physiotherapy strategies; and 3) providing information, prognosis, and family communication. Within these three categories, interventions demonstrated to have a positive effect on patient or family outcomes included individualized weaning plans, and respiratory therapist-led weaning protocols including a protocol of tracheostomy collar weaning; exercise training and neuromuscular electrical stimulation; and use of a decision aid for substitute decision-makers (Table 3). Other categories reflected clinical features of chronic critical illness including deranged neuroendocrine function, altered brain function and neuropsychiatric disorders, malnutrition, skin breakdown, and increased vulnerability to infection (49). (See Supplementary Table 3 [Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A4] for the intervention or exposure, primary outcomes and main findings for other categories from studies with a control group; Supplementary Table 4 [Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A4] the 56 studies without a comparator group).

TABLE 2.

Actionable Processes of Care

TABLE 3.

Primary Results for Studies With a Comparator Group Grouped According to Actionable Process Category

Actionable Processes of Care Arising From Patient and Family Experience

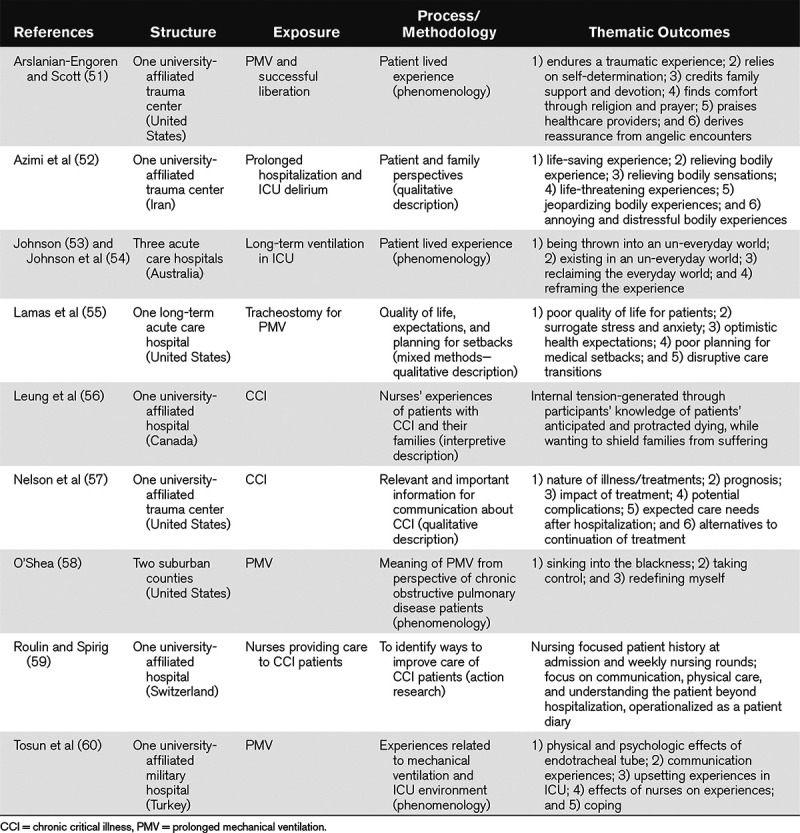

Using content analysis, from the nine qualitative studies (Table 4) reporting themes relating to patient and family experience, we found 14 actionable processes of care categories. The most common categories were addressing: 1) psychologic needs; 2) promoting interprofessional communication/decision-making; 3) enabling patient communication; and 4) symptom management. Three themes not found in quantitative studies for clinicians and decision-makers to consider as actionable processes were: 1) promoting patient coping skills through enabling of hope and optimism as well as regain of control; 2) addressing reduced quality of life; and 3) care planning that includes strategies as to how to address unanticipated reversal in clinical recovery. Categories that converged across studies and reviews of interventions and those from qualitative exploration of patient and family experience related to improving communication with family, enabling patient communication, and management of psychologic and symptom distress.

TABLE 4.

Themes From Qualitative Studies

Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

Of the 21 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including three secondary analyses of data relating to long-stay ICU patients from primary trials and the one nonrandomized intervention study, two RCTs were considered low risk across all domains (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A5; legend, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A4). We considered 14 (63%) to be at low risk of bias for sequence generation, six (27%) as unclear and two (9%) as at high risk of bias. Eleven studies (50%) were considered at low risk of bias due to allocation concealment, nine (41%) unclear and two (9%) at high risk. Blinding of personnel or participants was only feasible in six trials (27%), one trial (5%) was considered unclear risk; 11 trials (50%) blinded outcome assessors, three (14%) did not blind, the remainder were assessed as at unclear risk of bias. All but one trial were considered at low risk of incomplete outcomes, 10 (45%) at low risk of selective reporting, and 17 (77%) free from other sources of bias.

Of the 33 cohort studies with controls, two (6%) were considered to be of high quality, 15 (45%) of acceptable quality, and 16 (48%) of unacceptable quality. Thirteen (39%) were considered to have clear evidence of an association between exposure and outcome, 17 (52%) were considered to have unclear evidence, and three (9%) no evidence of an association between exposure and outcome (Supplementary Table 5, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A4). We did not perform quality assessment of the 43 studies without a control group. All nine qualitative studies were assessed as having a logical fit between aims and methods, seven (78%) reported appropriate recruitment methods and presented clear and detailed statements of findings, six (67%) described audio-recording and transcription processes as well as inter-rater discussion. Only two studies (22%) considered disconfirming findings or demonstrated reflexive concern. Four studies (44%) demonstrated interpretation of findings at a conceptual and theoretical level (Supplementary Table 6, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A4).

DISCUSSION

This systematic review identified 42 distinct categories of actionable processes of care for clinicians and decision-makers to consider when providing care to patients experiencing persistent or chronic critical illness and their family members. The most common categories were: 1) weaning—methods; 2) rehabilitation, mobilization, and physiotherapy; and 3) provision of information, prognosis, and family communication. Categories that converged across study designs types related to improving family communication, enabling patients to communicate, and management of psychologic and symptom distress. We did not identify any quality indicators, measures, or tools to evaluate quality of care or patient/family member experience of care. Only two (61, 62) RCTs were considered at low risk of bias, whereas only two (63, 64) cohort studies and one qualitative study (58) were considered of high quality.

Based on the numbers of studies within categories in the existing evidence base, implementation of processes of care that focus on weaning, rehabilitation/mobilization, and information sharing/family communication should be considered by clinicians and decision-makers as processes to optimize to enable provision of high-quality care. Likewise, those that converged across study designs should be prioritized; particularly provision of timely, frequent and empathetic communication with families, and alleviation of symptom burden.

Most patients with persistent or chronic critical illness will experience prolonged weaning from ventilation. Weaning protocols are effective for reducing ventilation duration in the broader ICU patient population (65). In this review, we found some evidence of effectiveness for patients with prolonged need for mechanical ventilation. Studies in this review reporting on patient and family experience highlight the need to address the distressing symptoms and psychologic impact of weaning failure, which should be considered when designing interventions to facilitate weaning in this patient population. Similarly, most if not all persistently or chronically critically ill patients will require physical rehabilitation strategies, due to profound weakness and muscle atrophy associated with myopathy, neuropathy, and alterations in body composition (5), benefits of which are likely best achieved when commenced early (66).

When comparing our results to the number of studies reporting efficacious or effective actionable processes of care during acute critical illness (11), the 21 RCTs identified in our systematic review highlights the paucity of high-level evidence for patients with persistent or chronic critical illness. Although reasons for the current lack of an evidence-base are likely multifactorial, the common strategy of single-center research identified in our review limits the number of potential study participants. It can also lead to a lengthy recruitment period, such as in a landmark trial of tracheostomy collar weaning at a LTACH, which took 10 years to accrue 316 participants (36). Of concern is the relatively limited evidence within each category, particularly in patient-centered categories such as communication, promotion of sleep and day/night routines, psychologic and social functioning, symptom management, or family support. Furthermore, studies did not reflect person-centered care approaches and the lack of qualitative observational inquiry limits understanding of the influence of the organizational context on care processes and outcomes.

We identified 42 distinct categories of actionable processes of care, which is indicative of the extent of the needs of these patients and their families, and arises from the range of clinical features of persistent or chronic critical illness. However, this presents challenges for clinicians and decision-makers in terms of which processes to prioritize. Furthermore, published studies designed by researchers may not reflect priorities of care of greatest importance from a patient/family member perspective. The lack of quality indicators, measures, or tools to evaluate quality of care or patient/family member experience, developed specifically for patients with persistent or chronic critical illness, may contribute to poor patient/family experience and adverse outcomes. Such strategies are needed to embed actionable processes into routine clinical practice. Rounding or daily goal checklists are strategies shown to improve adherence to evidence-based practices enabling a systematic approach to care yet individualizing set goals (18, 67). Tools are needed that address those actionable processes of care most relevant to the needs of patients with persistent critical illness and their families. Subsequent phases of our research program aim to address these gaps.

Informed by experience based co-design methods (68), a rigorous quality improvement method that involves lived experience, expertise, and knowledge of those using and providing a service (69), we will conduct interviews with survivors of persistent or chronic critical illness, family members, and clinicians to establish important actionable processes of care from their perspectives. We will develop a short touch-point video using patient and family interview data to inform clinician interviews. To inform development of quality improvement tools including a daily goals checklist, we will gain consensus as to the most important actionable processes of care, using a two-round Delphi process (70) and modified nominal group technique involving clinicians, ICU survivors, and family (71).

This is the first systematic review of actionable care processes for patients with persistent or chronic critical illness to our knowledge. We used rigorous methods including two authors independent citation screening, data extraction, and coding as well as validated tools to assess risk of bias and evidence quality. There are also limitations. First, due to disparate study interventions, designs, and small numbers of studies with a control group evaluating a similar intervention, we were unable to perform meta-analyses or appraise the certainty of evidence, that is, apply the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation approach (72) or assess publication bias. Additionally, by limiting studies to those that used greater than or equal to 7 days as an inclusion criterion, it is possible we excluded some studies of potential relevance. However, given our inclusion of 216 studies, it is unlikely we missed other categories of actionable processes of care. Last, our exclusion of non-English language studies could limit generalizability.

CONCLUSIONS

In this systematic review, we identified 42 distinct actionable processes of care relevant to patients with persistent or chronic critical illness and their families. Most frequently studied processes related to weaning, rehabilitation/mobilization, and communication with family. Reports of patient and family experience highlighted the need to address psychologic needs and distressing symptoms as well as enabling patient communication. Clinicians and decision-makers should consider our findings to plan high-quality patient and family-focused care. However, we did not identify relevant quality indicators, measures, or tools to evaluate or facilitate high quality of care or patient/family member experience of care highlighting the pressing need for such tools and metrics. Our findings also highlight the need for a stronger evidence base for those actionable processes of care deemed most important to improve outcomes and experience of persistent or chronically critically ill patients and their family.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Becky Skidmore, MLS (Independent Information Specialist), for assisting us with the search design and executing the search strategies, downloading results, removing duplicates, performing the gray literature search, and documenting the search strategies and methods. We thank Heather MacDonald, MLIS (MacOdrum Library, Carleton University), for peer review of the MEDLINE search strategy. We thank Shelley Gershman for her assistance with coordinating data extraction.

PatiEnt Reported Family Oriented perfoRmance Measures (PERFORM) study investigators: Andre Amaral, Shannon Carson, Christopher Cox, Brian H. Cuthbertson, Vagia Campbell, Eddy Fan, Jack Iwashyna, Vincent Lo, Lorrie Hamilton, Tracey Sharon, and Deepak Varma.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was conducted at the University of Toronto and King’s College London.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccejournal).

This review was funded by the Michael Garron Hospital Community Research Fund and the Ontario Respiratory Care Society.

The views expressed are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health.

Dr. Rose’s institution received funding from Michael Garron Hospital Community Research Fund and the Ontario Respiratory Care Society. Dr. Connolly holds a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Post-Doctoral Fellowship and is supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’s NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Systematic Review Registration—Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 42016052715.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Andre Amaral, Shannon Carson, Christopher Cox, Brian H. Cuthbertson, Vagia Campbell, Eddy Fan, Jack Iwashyna, Vincent Lo, Lorrie Hamilton, Tracey Sharon, and Deepak Varma

REFERENCES

- 1.Carson SS. Outcomes of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Curr Opin Crit Care 200612405–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwashyna TJ, Hodgson CL, Pilcher D, et al. Timing of onset and burden of persistent critical illness in Australia and New Zealand: A retrospective, population-based, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 20164566–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lone NI, Walsh TS. Prolonged mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients: Epidemiology, outcomes and modelling the potential cost consequences of establishing a regional weaning unit. Crit Care 201115R102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Critical Care Services Ontario. Long-Term Mechanical Ventilation: Toolkit for Adult Acute Care Providers. Toronto, ON, Canada: Critical Care Services Ontario; 2013. Available at: https://www.criticalcareontario.ca/EN/Toolbox/Toolkits/Long-Term%20Mechanical%20Ventilation%20Toolkit%20for%20Adult%20Acute%20Care%20Providers.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loss SH, Nunes DSL, Franzosi OS, et al. Chronic critical illness: Are we saving patients or creating victims? Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 20172987–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwashyna TJ, Hodgson CL, Pilcher D, et al. Towards defining persistent critical illness and other varieties of chronic critical illness. Crit Care Resusc 201517215–218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn JM, Benson NM, Appleby D, et al. Long-term acute care hospital utilization after critical illness. JAMA 20103032253–2259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carson SS, Kahn JM, Hough CL, et al. ; ProVent Investigators A multicenter mortality prediction model for patients receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 2012401171–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson JE, Cox CE, Hope AA, et al. Chronic critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010182446–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn JM, Le T, Angus DC, et al. ; ProVent Study Group Investigators The epidemiology of chronic critical illness in the United States*. Crit Care Med 201543282–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn JM, Davis BS, Le TQ, et al. Variation in mortality rates after admission to long-term acute care hospitals for ventilator weaning. J Crit Care 2018466–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maguire JM, Carson SS. Strategies to combat chronic critical illness. Curr Opin Crit Care 201319480–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrinec AB, Mazanec PM, Burant CJ, et al. Coping strategies and posttraumatic stress symptoms in post-ICU family decision makers. Crit Care Med 2015431205–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Nelson JE, Hanson LC, et al. How surrogate decision-makers for patients with chronic critical illness perceive and carry out their role. Crit Care Med 201846699–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose L, Fowler RA, Goldstein R, et al. ; CANuVENT Group Patient transitions relevant to individuals requiring ongoing ventilatory assistance: A Delphi study. Can Respir J 201421287–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amaral A, Rubenfeld G. Hall J, Schmidt G, Kress J. Measuring quality. In: Principles of Critical Care 2015Fourth EditionColumbus, OH: McGraw-Hill; 7–15 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose L, Fowler RA, Fan E, et al. ; CANuVENT group Prolonged mechanical ventilation in Canadian intensive care units: A national survey. J Crit Care 20153025–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centofanti JE, Duan EH, Hoad NC, et al. Use of a daily goals checklist for morning ICU rounds: A mixed-methods study. Crit Care Med 2014421797–1803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. ; PRISMA-P Group Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015350g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rose L, Istanboulian L, Allum L, et al. ; PERFORM study investigators Patient- and family-centered performance measures focused on actionable processes of care for persistent and chronic critical illness: Protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev 2017684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose L, McGinlay M, Amin R, et al. Variation in definition of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Respir Care 2017621324–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kandilov A; Chronically Critically Ill Population Payment Recommendations (CCIP-PR) 2014Available at: http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/ChronicallyCriticallyIllPopulation-Report.pdf

- 23.Higgins J, Green SE; Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0: The Cochrane Collaboration 2011

- 24.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN): Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) checklists. 2015. Available at: www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/checklists.html. Accessed June 1, 2016.

- 25.CASP: 10 Questions to Help You Make Sense of Qualitative Research. 2014. Available at: http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2016.

- 26.Popay J, Rogers A, Williams G. Rationale and standards for the systematic review of qualitative literature in health services research. Qual Health Res 19988341–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology 2013Third EditionLos Angeles, CA: SAGE [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 200424105–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q 200583691–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. ; PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Plos Med 20096e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saritas TB, Bozkurt B, Simsek B, et al. Ocular surface disorders in intensive care unit patients. ScientificWorldJournal 20132013182038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen S, Su CL, Wu YT, et al. Physical training is beneficial to functional status and survival in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. J Formos Med Assoc 2011110572–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clini EM, Crisafulli E, Antoni FD, et al. Functional recovery following physical training in tracheotomized and chronically ventilated patients. Respir Care 201156306–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duan J, Guo S, Han X, et al. Dual-mode weaning strategy for difficult-weaning tracheotomy patients: A feasibility study. Anesth Analg 2012115597–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henneman E, Dracup K, Ganz T, et al. Using a collaborative weaning plan to decrease duration of mechanical ventilation and length of stay in the intensive care unit for patients receiving long-term ventilation. Am J Crit Care 200211132–140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jubran A, Grant BJ, Duffner LA, et al. Effect of pressure support vs unassisted breathing through a tracheostomy collar on weaning duration in patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: A randomized trial. JAMA 2013309671–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rudy EB, Daly BJ, Douglas S, et al. Patient outcomes for the chronically critically ill: Special care unit versus intensive care unit. Nurs Res 199544324–331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheinhorn DJ, Chao DC, Stearn-Hassenpflug M, et al. Outcomes in post-ICU mechanical ventilation: A therapist-implemented weaning protocol. Chest 2001119236–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burtin C, Clerckx B, Robbeets C, et al. Early exercise in critically ill patients enhances short-term functional recovery. Crit Care Med 2009372499–2505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen YH, Lin HL, Hsiao HF, et al. Effects of exercise training on pulmonary mechanics and functional status in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Respir Care 201257727–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiang LL, Wang LY, Wu CP, et al. Effects of physical training on functional status in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Phys Ther 2006861271–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gruther W, Kainberger F, Fialka-Moser V, et al. Effects of neuromuscular electrical stimulation on muscle layer thickness of knee extensor muscles in intensive care unit patients: A pilot study. J Rehabil Med 201042593–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Montagnani G, Vagheggini G, Vlad EP, et al. Use of the functional independence measure in people for whom weaning from mechanical ventilation is difficult. Phys Ther 2011911109–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reames CD, Price DM, King EA, et al. Mobilizing patients along the continuum of critical care. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 20163510–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braus N, Campbell TC, Kwekkeboom KL, et al. Prospective study of a proactive palliative care rounding intervention in a medical ICU. Intensive Care Med 20164254–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carson SS, Cox CE, Wallenstein S, et al. Effect of palliative care-led meetings for families of patients with chronic critical illness: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 201631651–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cox CE, Lewis CL, Hanson LC, et al. Development and pilot testing of a decision aid for surrogates of patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 2012402327–2334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daly BJ, Rudy EB, Thompson KS, et al. Development of a special care unit for chronically critically ill patients. Heart Lung 19912045–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Douglas S, Daly BJ, Rudy EB, et al. Survival experience of chronically critically ill patients. Nurs Res 19964573–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marchioni A, Fantini R, Antenora F, et al. Chronic critical illness: The price of survival. Eur J Clin Invest 2015451341–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arslanian-Engoren C, Scott LD. The lived experience of survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation: A phenomenological study. Heart Lung 200332328–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Azimi AV, Ebadi A, Ahmadi F, et al. Delirium in prolonged hospitalized patients in the intensive care unit. Trauma Mon 201520e17874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnson P. Reclaiming the everyday world: How long-term ventilated patients in critical care seek to gain aspects of power and control over their environment. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 200420190–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson P, St John W, Moyle W. Long-term mechanical ventilation in a critical care unit: existing in an everyday world. J Adv Nurs 200653551–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lamas DJ, Owens RL, Nace RN, et al. Opening the door: The experience of chronic critical illness in a long-term acute care hospital. Crit Care Med 201745e357–e362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leung D, Blastorah M, Nusdorfer L, et al. Nursing patients with chronic critical illness and their families: A qualitative study. Nurs Crit Care 201722229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nelson JE, Kinjo K, Meier DE, et al. When critical illness becomes chronic: Informational needs of patients and families. J Crit Care 20052079–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O’Shea FM. Prolonged ventilator dependence: Perspective of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patient. Clin Nurs Res 200716231–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roulin MJ, Spirig R. Developing a care program to better know the chronically critically ill. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 200622355–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tosun N, Yava A, Unver V, et al. Experience of patients on prolonged mechanical ventilation: A phenomenological study. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences 200929648–658 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mesotten D, Wouters PJ, Peeters RP, et al. Regulation of the somatotropic axis by intensive insulin therapy during protracted critical illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004893105–3113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wei X, Day AG, Ouellette-Kuntz H, et al. The association between nutritional adequacy and long-term outcomes in critically ill patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: A multicenter cohort study. Crit Care Med 2015431569–1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garnacho-Montero J, Amaya-Villar R, García-Garmendía JL, et al. Effect of critical illness polyneuropathy on the withdrawal from mechanical ventilation and the length of stay in septic patients. Crit Care Med 200533349–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ibrahim EH, Iregui M, Prentice D, et al. Deep vein thrombosis during prolonged mechanical ventilation despite prophylaxis. Crit Care Med 200230771–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blackwood B, Burns K, Cardwell C, et al. Protocolized versus nonprotocolized weaning for reducing the duration of mechanical ventilation in critically ill adult patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 201411CD006904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Girard TD, Alhazzani W, Kress JP, et al. ATS/CHEST Ad Hoc Committee on Liberation from Mechanical Ventilation in Adults: An Official American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline: Liberation from mechanical ventilation in critically ill adults. Rehabilitation protocols, ventilator liberation protocols, and cuff leak tests. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017195120–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Byrnes MC, Schuerer DJ, Schallom ME, et al. Implementation of a mandatory checklist of protocols and objectives improves compliance with a wide range of evidence-based intensive care unit practices. Crit Care Med 2009372775–2781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.The King’s Fund: Experience-Based Co-Design Toolkit. 2013. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/ebcd. Accessed March 26, 2019.

- 69.Blackwell RW, Lowton K, Robert G, et al. Using experience-based codesign with older patients, their families and staff to improve palliative care experiences in the emergency department: A reflective critique on the process and outcomes. Int J Nurs Stud 20176883–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs 2000321008–1015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Van de Ven A, Delbecq A. The nominal group as a research instrument for exploratory health studies. Am J Public Health 197262337–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 201164383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.