Objectives:

For children and their families, PICU admission can be one of the most stressful and traumatic experiences in their lives. Children admitted to the PICU and their parents experience sequelae following admission including psychologic symptoms and lower health-related quality of life. The impact of a PICU admission on school attendance and performance may influence these sequelae. The purpose of our study was to examine how community supports from pediatricians and schools influence school success after critical illness.

Design:

Parents were recruited during their child’s admission to the PICU. Three months after discharge, parents completed follow-up questionnaires via telephone.

Setting:

PICU in an urban academic children's hospital.

Subjects:

Thirty-three parents were enrolled in the study, and 21 (64%) completed phone follow-up.

Measurements and Main Results:

Forty-three percent of children missed 7 or more days of school while admitted to the PICU. Sixty-seven percent of parents reported that their pediatrician did not ask about missed school, and 29% felt their child’s grades worsened since admission. Twenty percent of respondents felt that their child’s school did not provide adequate services to help their child catch up.

Conclusions:

There are missed opportunities for care coordination and educational support after critical illness. The transition back to school is challenging for some children, as reported by parents who described inadequate support from the school after PICU hospitalization and a subsequent decline in their child’s school performance. Additional studies are needed to develop proactive community supports to improve the transition back to school for a child after critical illness.

Keywords: discharge, family, follow-up, pediatric intensive care unit, school, support

Although mortality related to pediatric critical illness has decreased, morbidity among PICU survivors has increased (1). Therefore, there is an urgent need to understand and reduce the long-term morbidity of these survivors and optimize their functioning after discharge. Studies show that admission to the PICU may have a significant impact on both the neuropsychologic functioning of children and their health-related quality of life (HRQOL). For example, children who survive critical illness experience increased emotional difficulties, perform worse on tests of intelligence, executive function, and memory, and are perceived by their teachers as having more educational problems than children without a history of critical illness (2–4). When compared with healthy children, critically ill children have lower HRQOL (5–7) and experience a significant decrease in HRQOL after PICU admission (3). PICU survivors are also at increased risk of psychologic sequelae including behavioral changes, fatigue disorders, sleep disturbances (4, 8), and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSDs) (4, 9). Higher levels of parental distress, longer PICU stays, and emergency admissions are associated with increased likelihood of PTSD among PICU survivors (8). Despite this growing body of evidence, there is no standard of care for follow-up of children after discharge from the PICU. Although other critical care environments, such as the neonatal ICU, have implemented standardized follow-up programs to address sequelae of critical illness and ensure a smooth transition following discharge, there is often a lack of such support for children who are discharged from the PICU. The development of evidence-based programs for PICU follow-up is needed to decrease postdischarge complications and to improve child and family resiliency after PICU admission.

Several factors may influence postdischarge outcomes following PICU admission, including underlying health status and comorbidities, admission diagnoses, and length of stay (LOS) (3, 10–13). However, there may be other factors which are modifiable post-discharge. Such factors could therefore be addressed by care in a PICU follow-up program in order to further improve outcomes for children even after they have been discharged. One potential mediator of long-term outcomes for PICU survivors is the role of missed school. Because school shapes a child’s social, cognitive, language, behavioral, and physical development, school absences and difficulties with school reintegration may account, in part, for the negative sequelae associated with critical illness. In addition, there are high rates of neurodevelopmental disabilities among children admitted to the PICU (14), which may further increase the risk for poor outcomes with missed school. However, there have been few studies of the impact of PICU admission on school attendance and performance. The objective of this pilot study was to explore the extent to which PICU admission disrupts school attendance and school performance and to describe the supports and barriers children and their families experience with regard to school reintegration.

METHODS AND RESULTS

Enrollment occurred between January 2014 and March 2014 at an urban academic children’s hospital. Approval from the institutional review board was obtained for this study. Parents were approached to participate in this study during their child’s admission to the PICU. Inclusion criteria included parent of a child less than 18 years old admitted to the PICU, currently enrolled in 1st–12th grade, and had previously completed 1 year of school (kindergarten or higher grade) prior to PICU admission. Exclusion criteria included parents of children who were nonverbal at baseline or if the parents’ primary language was not English. Children were also excluded if the treating physician believed the research approach may have interfered with their treatment, or if the child was unlikely to survive to discharge. Eligible parents present at the bedside were approached for enrollment during the targeted enrollment period, which determined the study size. Phone follow-up was completed 3 months later and the primary outcomes assessed were missed days school, supports/services received after discharge, and families’ experience with school reintegration. The electronic medical record was reviewed for potential associated factors, including demographics, LOS, mechanical ventilation, vasopressor use, and surgical intervention. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture electronic data capture tools. Fisher exact and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to determine correlation between variables with significance set at alpha less than or equal to 0.05.

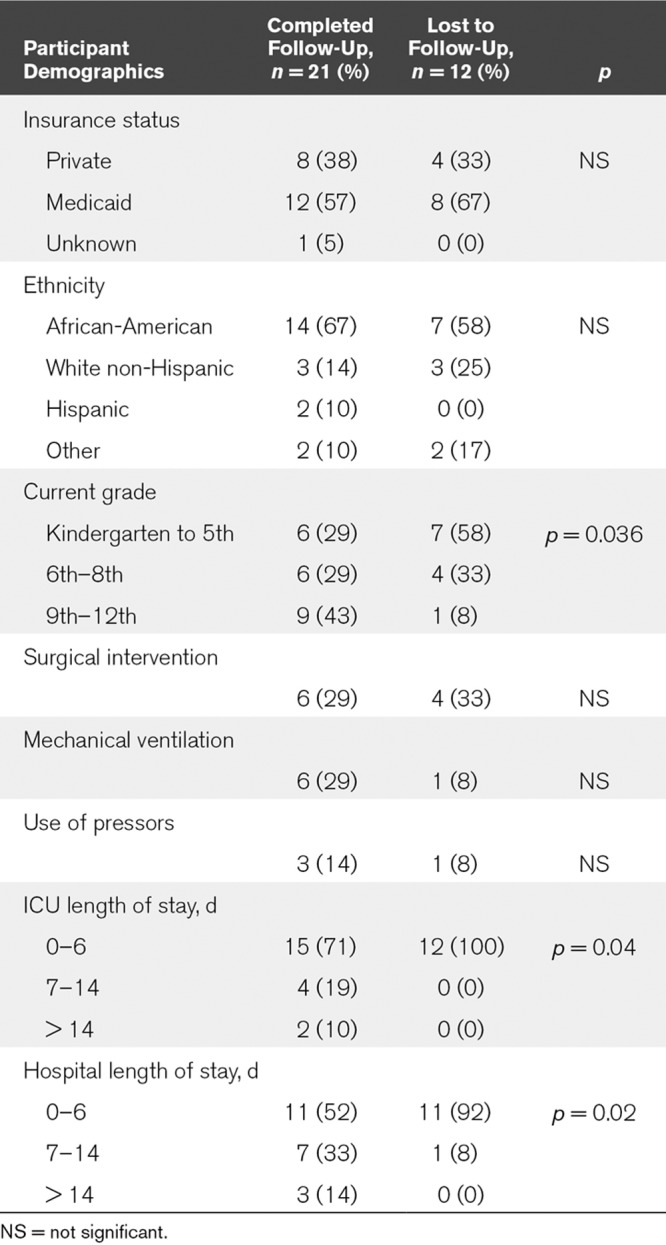

Thirty-three parents consented to participate in the study, providing information for 33 children. Twenty-one parents (64%) completed 3-month phone follow-up (Table 1); 12 were unable to be reached or declined the phone interview. The mean age of enrolled children was 11.8 years with a range of 6–17 years. Among those who completed follow-up, 67% of children were African-American, 14% were Non-Hispanic White, 10% were Hispanic, and 10% self-identified as another race. Twenty-nine percent of children required mechanical ventilation during their admission, 29% required surgical intervention, and 14% required the use of vasopressors. Participants who were lost to follow-up were significantly more likely to be younger and have shorter LOS.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Participants

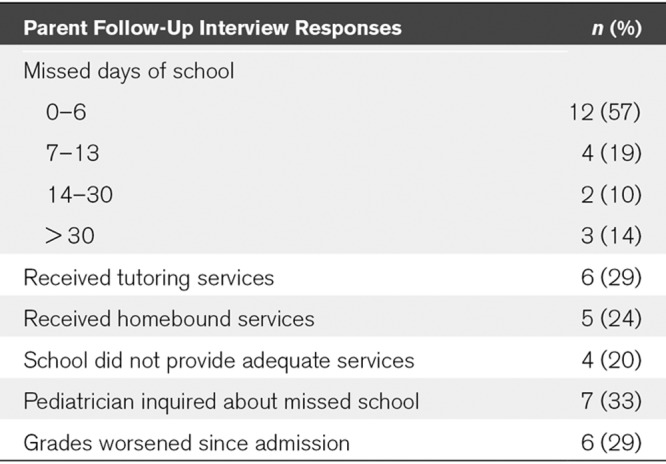

At follow-up, 43% of children missed 7 or more days of school while admitted to the PICU (Table 2). Overall, 76% of students did not receive homebound services, and 71% did not receive any tutoring supports. Among those who missed 7 or more days of school, 56% did not receive homebound services. Twenty-nine percent of parents reported that they believed their child’s grades worsened since his/her admission to the PICU, and 67% of those children had not received any homebound services or tutoring supports. Twenty percent of parents reported that they felt their child’s school did not provide adequate services to help their child catch up with missed school work. There was not any statistically significant difference in likelihood of receiving tutoring/homebound services between children with public versus private insurance. Parents identified the following factors as causing difficulty for their child in completing missed work: physical health (38%), concentration (24%), understanding (14%), needing more time (38%), and needing tutoring (29%). Sixty-seven percent of parents reported their pediatrician did not ask about the child’s missed school and/or return to school following PICU admission.

TABLE 2.

Impact of PICU Hospitalization on School Performance: Met and Unmet Needs; n = 21 (%)

DISCUSSION

This pilot project focused on exploring the impact of PICU admission on school experiences for children and parents experiencing critical illness. In our study cohort, we found that nearly half of children missed 7 or more days for critical illness. In the local school district of this hospital community, children must miss 10 school days to qualify for homebound school services (Office of Diverse Learner Supports and Services, Chicago Public Schools). In accordance with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) policy statement, “Home, Hospital, and Other Non-School Based Instruction for Children and Adolescents Who Are Medically Unable to Attend School” (15), because any school absence is disruptive to the educational process, a request for non–school-based instruction should be considered in a timely manner. However, over half of children in our project who reported missing 7 or more days of school during their admission did not receive such services. These findings raise concern that the present systems of educational support for critically ill children are inadequate, and medical and educational systems must work cooperatively to address this need. Our study found that the majority of parents reported that their pediatrician did not discuss the child’s return to school. The AAP’s recent policy statement, “The Link Between School Attendance and Good Health,” recommends that pediatricians should routinely ask about school absences at both preventive and sick visits and support parents in addressing barriers to school attendance (16). Our findings identify there are currently missed opportunities for the patient-centered medical home model to support the school reintegration process.

To determine how to best support children with critical illness, we may look to existing models and lessons learned from pediatric oncology patients. Support models for children with cancer returning to school have described a number of different approaches during school reintegration (17–19). In a qualitative study, teachers, parents, and children with cancer consistently reported a comprehensive school-based reintegration program was beneficial in facilitating school reentry. The intervention included interim educational services during hospitalization, identification of a liaison between the hospital and school, psychoeducation for the child and parents prior to school reentry, presentations for school personnel and peers about the child’s illness, and periodic follow-up with all involved parties to address any problems that arose (17). Another study described a similar school reintegration model which used a school-hospital liaison team that coordinated communication among all parties, provided counseling support to the child, their family, school personnel, and peers, and facilitated ongoing follow-up (19). Because of the acuity and severity of critical illness, potential deterioration from baseline for both previously healthy and previously chronically ill children may have a different, and likely greater, magnitude and resultant impact than prolonged hospitalization after noncritical illness. In addition, the psychologic sequelae of PICU admission may influence children and parents’ ability to reintegrate into school after discharge. Therefore, these type of supports may be especially impactful among PICU survivors.

We recognize that there may potentially be significant logistical and financial barriers which would limit the feasibility of such a program for all children who have been admitted to the PICU. Therefore it may be most effective to target efforts to the patient populations which are most likely to require support during the transition from PICU (or hospital) to home, such as those with prolonged hospitalizations and significant morbidity following critical illness. In our pilot study, we found that parents whose child had a LOS of 7 days or longer universally completed telephone follow-up at three months, whereas only half of those with a shorter stay completed telephone follow-up. Perhaps those families with a longer LOS are more likely to need and seek support after their child’s discharge and therefore were open to participating in our project about PICU follow-up needs. We note that discussion of school reintegration may be difficult in the primary care setting due to time constraints, as PICU survivors often have high level of medical care complexity, and at times there is inconsistent communication between inpatient providers and ambulatory providers. This presents an opportunity for inpatient and ambulatory healthcare providers to provide comprehensive, coordinated care (e.g., monitoring for medical complications, neurocognitive or neuropsychologic evaluations, need for individualized education plan development) in a multidisciplinary setting such as PICU follow-up clinic. That venue could bring together experts in critical care, neurodevelopment, psychology, physiatry, and general pediatrics in order to coordinate complex care for these medically vulnerable children and their families.

Limitations of our pilot study include sample size, reliance on parent report of outcomes, and selection bias. Missing data were not imputed for patients who were lost to follow-up. Parent report may also provide a biased representation of how a child is functioning at school. Our enrollment was limited to recruitment of a convenience sample during a 3-month period, which may have produced a seasonal bias associated with children admitted during this period in the winter. However, we would not anticipate winter school absenteeism to differ substantially from fall or spring absenteeism. Although these factors may limit generalizability to other populations of children admitted to the PICU, we note that this study provides preliminary evidence that substantial opportunities for improving school outcomes and reintegration exist in the current system.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, there is a robust body of evidence that critically ill children experience significant disruptions in functioning after discharge. This impact on functioning is likely multifactorial in origin, including medical complications, missed school, and psychologic stressors. Despite the existence of standard follow-up programs for neonate survivors of critical care, supports are currently inadequate for older children who experience a critical illness. Improved communication and coordination between multidisciplinary healthcare providers (intensivists, subspecialists, and primary care provider) proximal to a child’s discharge from the PICU, with attention to the need to proactively address transition and reintegration to school, may benefit children who experience critical illness. Future research is needed to assess the necessary components of such models, determine which patients are most likely to benefit from such supports, and to further explore the other aspects of community reintegration that are challenging for families following their discharge from the PICU.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the parents who participated in our pilot project in spite of the tremendous demands of their child’s critical illness. We also wish to acknowledge Kristen Wroblewski, MS, for statistical analysis consultation as well as Chris Mattson, MD and Karla Garcia-DiGioia, MD for their efforts in patient recruitment and data collection.

Footnotes

This work was performed at the University of Chicago.

Drs. Msall’s and Sobotka’s efforts were supported in part by grant funding from Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and Related Disorders Training Program T73 MC11047 Acharya (University of Chicago-Illinois) and Sobotka (University of Chicago) July 1, 2016, to June 30, 2021. Source: Health Resources and Services Administration/U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Research Electronic Data Capture project at the University of Chicago is hosted and managed by the Center for Research Informatics and funded by the Biological Sciences Division and by the Institute for Translational Medicine, Clinical and Translational Science Award grant number UL1 TR000430 from the National Institutes of Health. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Funai T, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network Pediatric intensive care outcomes: Development of new morbidities during pediatric critical care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 201415821–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Als LC, Nadel S, Cooper M, et al. Neuropsychologic function three to six months following admission to the PICU with meningoencephalitis, sepsis, and other disorders: A prospective study of school-aged children. Crit Care Med 2013411094–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polic B, Mestrovic J, Markic J, et al. Long-term quality of life of patients treated in paediatric intensive care unit. Eur J Pediatr 201317285–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Als LC, Picouto MD, Hau SM, et al. Mental and physical well-being following admission to pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 201516e141–e149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knoester H, Bronner MB, Bos AP, et al. Quality of life in children three and nine months after discharge from a paediatric intensive care unit: A prospective cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colville GA, Pierce CM. Children’s self-reported quality of life after intensive care treatment. Pediatr Crit Care Med 201314e85–e92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebrahim S, Singh S, Hutchison JS, et al. Adaptive behavior, functional outcomes, and quality of life outcomes of children requiring urgent ICU admission. Pediatr Crit Care Med 20131410–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rennick JE, Rashotte J. Psychological outcomes in children following pediatric intensive care unit hospitalization: A systematic review of the research. J Child Health Care 200913128–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rees G, Gledhill J, Garralda ME, et al. Psychiatric outcome following paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admission: A cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2004301607–1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mestrovic J, Kardum G, Sustic A, et al. Neurodevelopmental disabilities and quality of life after intensive care treatment. J Paediatr Child Health 200743673–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrison AL, Gillis J, O’Connell AJ, et al. Quality of life of survivors of pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 200231–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiser DH, Tilford JM, Roberson PK. Relationship of illness severity and length of stay to functional outcomes in the pediatric intensive care unit: A multi-institutional study. Crit Care Med 2000281173–1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newburger JW, Wypij D, Bellinger DC, et al. Length of stay after infant heart surgery is related to cognitive outcome at age 8 years. J Pediatr 200314367–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sobotka SA, Peters S, Pinto NP. Neurodevelopmental disorders in the PICU population. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 201857913–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on School Health. Home, hospital, and other non-school-based instruction for children and adolescents who are medically unable to attend school. Pediatrics 20001061154–1155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allison MA, Attisha E. The link between school attendance and good health. Pediatrics. 2019;143:e20183648. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz ER, Varni JW, Rubenstein CL, et al. Teacher, parent, and child evaluative ratings of a school reintegration intervention for children with newly diagnosed cancer. Child Health Care 19922169–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prevatt FF, Heffer RW, Lowe PA. A review of school reintegration programs for children with cancer. J School Psychol 200038447–467 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Worchel-Prevatt FF, Heffer RW, Prevatt BC, et al. A school reentry program for chronically ill children. J School Psychol 199836261–279 [Google Scholar]