Abstract

Objective:

This article provides a systematic review of cross-sectional research examining associations between exposure to alcohol marketing and alcohol use behaviors among adolescents and young adults.

Method:

Literature searches of eight electronic databases were carried out in February 2017. Searches were not limited by date, language, country, or peer-review status. After abstract and full-text screening for eligibility and study quality, 38 studies that examined the relationship between alcohol marketing and alcohol use behaviors were selected for inclusion.

Results:

Across alcohol use outcomes, various types of marketing exposure, and different media sources, our findings suggest that cross-sectional evidence indicating a positive relationship between alcohol marketing exposure and alcohol use behaviors among adolescents and young adults was greater than negative or null evidence. In other words, cross-sectional evidence supported that alcohol marketing exposure was associated with young peoples’ alcohol use behaviors. In general, relationships for alcohol promotion (e.g., alcohol-sponsored events) and owning alcohol-related merchandise exposures were more consistently positive than for other advertising exposures. These positive associations were observed across the past four decades, in countries across continents, and with small and large samples.

Conclusions:

Despite issues of measurement and construct clarity within this body of literature, this review suggests that exposure to alcohol industry marketing may be important for understanding and reducing young peoples’ alcohol use behavior. Future policies aimed at regulating alcohol marketing to a greater extent may have important short- and long-term public health implications for reducing underage or problematic alcohol use among youth.

This article provides a systematic review of cross-sectional research examining associations between exposure to alcohol marketing and alcohol use behaviors among adolescents and young adults. Understanding if and how exposure to marketing influences young people is an important issue for researchers, public health advocates, and practitioners. Concerns have been raised about youth, in particular, because of their potential vulnerability to marketing influences (Bonnie & O’Connell, 2004), extensive consumption of media and exposure to alcohol marketing (Jernigan et al., 2005; King et al., 2017; Ross et al., 2014b), and heightened risk of engaging in heavy drinking (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017). Because alcohol marketing has the potential to reach large audiences, even small effects on behavior may have substantial effects at the population level.

Compared with most other products, there are key differences in the ways in which alcohol can be advertised and marketed as a result of statutory and self-imposed regulations, with self-regulation often used to avoid governmental regulation (Babor, 2010). In the United States, for example, voluntary codes specify that alcohol advertising should be restricted to media where 71.6% of the expected audience is of legal drinking age (≥21 years), should not depict excessive drinking or acceptance of drunken behavior, and should not claim or represent that alcohol consumption is related to success or status (Beer Institute, 2018; Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, 2011; Wine Institute, 2011). Public health advocates, however, have criticized industry codes because there is no independent oversight, monitoring, or enforcement. In particular, concern has been expressed that these codes may be ineffective at limiting young people’s exposure to alcohol marketing and may be aimed more at placating policy makers than at protecting public health (Babor, 2010; Casswell & Maxwell, 2005; Noel & Babor, 2017; Noel et al., 2017; Pierce et al., 2019).

Whether young people are deliberately targeted by alcohol advertisers or not, adolescents and young adults are regularly exposed to alcohol advertising (Jernigan et al., 2005; King et al., 2017; Ross et al., 2014b). Although exposure to advertising may influence alcohol consumption directly, theoretical conceptualizations such as the marketing receptivity model and message interpretation process model posit that effects of exposure may be mediated through cognitive and affective responses (Austin, 2007; McClure et al., 2013a). Importantly, then, studies suggest that young people are not only exposed to alcohol advertising but also attend to it and often find it appealing and attractive (Austin et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2005).

Although cross-sectional studies of alcohol marketing cannot establish causal or time-ordered relations between marketing exposures and alcohol use, they are nonetheless important. Cross-sectional studies represent a substantial proportion of the research on alcohol marketing, in part because they are relatively easy to conduct, are less expensive than longitudinal studies, and avoid ethical issues that arise in experimental studies. Despite their shortcomings, cross-sectional studies can provide important information. Of note, they can establish whether associations between alcohol marketing exposures and alcohol use exist and whether these associations are substantive enough to deserve further study using more rigorous research designs. In addition, cross-sectional studies can identify potentially important mechanisms that may mediate or moderate marketing influences. They thus can play an important role in theory development, increase our understanding of how marketing influences might work, and identify potential targets for intervention.

In this article, we provide a systematic review of the cross-sectional research on alcohol marketing and alcohol use behaviors among adolescents and young adults. Although there have been previous literature reviews on alcohol advertising among youth (e.g., Berey et al., 2017; Grube, 2004; Russell et al., 2016), most have been narrative reviews, and none have undertaken a systematic consideration of the extensive cross-sectional literature. As part of the larger consensus project investigating alcohol marketing and alcohol use, we address differences across forms of media, types of exposures, and alcohol use outcomes, and whether the evidence of associations is robust across studies. We also critically consider the quality of the research and provide directions for future studies focusing on strengthening the measurement and conceptualization of both exposure to marketing and alcohol use outcomes. Last, we discuss the implications of the findings for policy and prevention or intervention.

Method

Literature search strategy

The project coordination team searched eight electronic databases for the concepts of “alcohol” and “marketing” up to February 14, 2017 (see supplement introduction, Sargent et al., 2020). Databases included Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 1992–February 14, 2017); MEDLINE via Ovid (1946–February 14, 2017); Embase via Elsevier (1947–February 14, 2017); Web of Science and CINAHL (nursing/allied health) via EBSCO (1900–February 14, 2017); PsycINFO via EBSCO (1806–February 14, 2017); Communication & Mass Media Complete via EBSCO (1918–February 14, 2017); and Econlit via Proquest (1969–February 14, 2017). Literature searches of databases were not limited by date, language, country, or peer-review status. Some of these databases indexed grey literature (e.g., books/monographs, conference papers, and other nonperiodical sources).

The search of key concepts by the project coordination team yielded 27,351 results. After de-duplication and two rounds of title and abstract screening, 409 titles remained potentially eligible for our cross-sectional review. The project coordination team provided us with full texts of these articles, which we screened according to our inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were evaluated for inclusion based on language, study design, sample age, exposure measure, and outcome measure. First, only studies in English were included. The study design was limited to cross-sectional studies that controlled for at least some known confounders. For the purpose of parsimony, control variables were grouped into individual (e.g., age or gender), interpersonal (e.g., parental perceptions), and environmental (e.g., alcohol outlet density) level controls (Table 1). We excluded studies that used simple descriptive or bivariate analyses. For the sample, we included only research that focused on individuals 25 years old or younger. Studies that included a broader age range were included only if subgroup analyses considered participants within the age range of interest. Studies that examined any exposure to industry alcohol advertising were included, other than exposure through earned media (e.g., watching others use alcohol on social media). Studies that assessed only general measures of time using media (e.g., hours of television watched) were excluded. Last, for outcome measures, only studies that examined alcohol use behaviors or problems were included (e.g., heavy episodic drinking [HED], alcohol dependence).

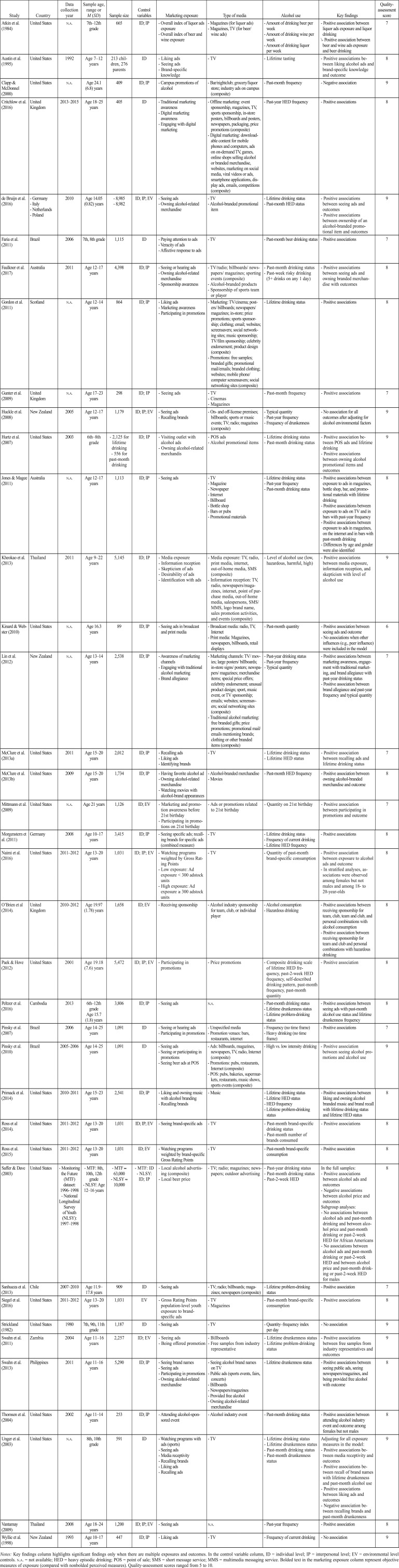

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the systematic review

| Study | Country | Data collection year | Sample age, range or M (SD) | Sample size | Control variables | Marketing exposure | Type of media | Alcohol use | Key findings | Quality-assessment score |

| Atkin et al. (1984) | United States | n.a. | 7th–12th grade | 665 | ID; IP | - Overall index of liquor ads exposure | - Magazines (for liquor ads) | - Amount of drinking beer per week | - Positive association between liquor ads exposure and liquor drinking | 7 |

| - Overall index of beer and wine exposure | - Magazines, TV (for beer/wine ads) | - Amount of drinking wine per week | \- Positive association between beer and wine ads exposure and beer drinking | |||||||

| - Amount of drinking liquor per week | ||||||||||

| Austin et al. (1995) | United States | 1992 | Age 7–12 years | 213 children, 276 parents | ID | - Liking ads | - TV | - Lifetime tasting | - Positive associations between liking alcohol ads and brand-specific knowledge and outcome | 8 |

| - Seeing ads | ||||||||||

| - Brand-specific knowledge | ||||||||||

| Clapp & McDonnel (2000) | United States | n.a. | Age 24.1 (6.8) years | 409 | ID; IP | - Campus promotions of alcohol | - Bar/nightclub; grocery/liquor store; industry ads on campus (composite) | - Past-month frequency | - Negative association | 9 |

| Critchlow et al. (2016) | United Kingdom | 2013–2015 | Age 18–25 years | 405 | ID | - Traditional marketing awareness | - Offline marketing: event sponsorship, magazines, TV, sports sponsorship, in-store posters, billboards and posters, newspapers, packaging, price promotions (composite) | - Past-year HED frequency | - Positive associations | 8 |

| - Digital marketing awareness | - Digital marketing: downloadable content for mobile phones and computers, ads on on-demand TV, games, online shops selling alcohol or branded merchandise, websites, marketing on social media, viral videos or ads, smartphone applications, display ads, emails, competitions (composite) | |||||||||

| - Engaging with digital marketing | ||||||||||

| de Bruijn et al. (2016) | - Germany | 2010 | Age 14.05 (0.82) years | - 8,985 | ID; IP; EV | - Seeing ads | - TV | - Lifetime drinking status | - Positive associations between seeing ads and outcomes | 9 |

| - Italy | - 8,982 | - Owning alcohol-related merchandise | - Alcohol-branded promotional item | - Past-month HED status | - Positive associations between ownership of an alcohol-branded promotional item and outcomes | |||||

| - Netherlands | ||||||||||

| - Poland | ||||||||||

| Faria et al. (2011) | Brazil | 2006 | 7th, 8th grade | 1,115 | ID | - Paying attention to ads | - TV | - Past-month beer drinking status | - Positive associations | 7 |

| - Veracity of ads | ||||||||||

| - Affective response to ads | ||||||||||

| Faulkner et al. (2017) | Australia | 2011 | Age 12–17 years | 4,398 | ID; IP | - Seeing or hearing ads | - TV/radio; billboards/ newspapers/ magazines; sporting events (composite) | - Past-month drinking status | - Positive associations between seeing ads and owning branded merchandise with outcomes | 8 |

| - Owning alcohol-related merchandise | - Alcohol-branded products | - Past-week risky drinking (5+ drinks on any 1 day) | ||||||||

| - Sponsorship awareness | - Sponsorship of sports team or player | |||||||||

| Gordon et al. (2011) | Scotland | n.a. | Age 12–14 years | 864 | ID; IP | - Liking ads | - Marketing: TV/cinema; posters/billboards; newspapers/ magazines; in-store; price promotions; sports sponsorship; clothing; email; websites; screensavers; social networking sites; music sponsorship; TV/film sponsorship; celebrity endorsement; product design (composite) | - Lifetime drinking status | - Positive associations | 8 |

| - Marketing awareness | - Promotions: free samples; branded gifts; promotional mail/emails; branded clothing; websites; mobile phone/computer screensavers; social networking sites (composite) | |||||||||

| - Participating in promotions | ||||||||||

| Gunter et al. (2009) | United Kingdom | n.a. | Age 17–23 years | 298 | ID; IP | - Seeing ads | - TV | - Past-month frequency | - Positive associations | 7 |

| - Cinemas | ||||||||||

| - Magazines | ||||||||||

| Huckle et al. (2008) | New Zealand | 2005 | Age 12–17 years | 1,179 | ID; IP; EV | - Seeing ads | - On- and off-license premises; billboards; sports or music events; TV; radio; magazines (composite) | - Typical quantity | - No association for all outcomes after adjusting for alcohol environmental factors | 9 |

| - Recalling brands | - Past-year frequency | |||||||||

| - Frequency of drunkenness | ||||||||||

| Hurtz et al. (2007) | United States | 2003 | 6th–8th grade | - 2,125 for lifetime drinking | ID; IP | - Visiting outlet with alcohol ads | - POS ads | - Lifetime drinking status | - Positive association between POS ads and lifetime drinking | 9 |

| - 556 for past-month drinking | - Owning alcohol-related merchandis | - Alcohol promotional items | - Past-month drinking status | - Positive associations between owning alcohol promotional items and outcomes | ||||||

| Jones & Magee (2011) | Australia | n.a. | Age 12–17 years | 1,113 | ID; IP | - Seeing ads | - TV | - Lifetime drinking status | - Positive associations between exposure to ads in magazines, bottle shop, bar, and promotional materials with lifetime drinking | 8 |

| - Magazine | - Past-year frequency | - Positive associations between exposure to ads on TV and in bars with past-year frequency | ||||||||

| - Newspaper | - Past-month drinking status | - Positive associations between exposure to ads in magazines, on the internet and in bars with past-month drinking | ||||||||

| - Internet | - Differences by age and gender were also identified | |||||||||

| - Billboard | ||||||||||

| - Bottle shop | ||||||||||

| - Bars or pubs | ||||||||||

| - Promotional materials | ||||||||||

| Kheokao et al. (2013) | Thailand | 2011 | Age 9–22 years | 5,145 | ID; IP | - Media exposure | - Media exposure: TV, radio, print media, internet, out-of-home media, SMS (composite) | - Level of alcohol use (low, hazardous, harmful, high) | - Positive associations between media exposure, information reception, and skepticism with level of alcohol use | 9 |

| - Information reception | - Information reception: TV, radio, newspapers/magazines, internet, point of purchase media, out-of-home media, salespersons, SMS/MMS, logo brand name, sales promotion activities, and events (composite) | |||||||||

| - Skepticism of ads | ||||||||||

| - Desirability of ads | ||||||||||

| - Identification with ads | ||||||||||

| Kinard & Webster (2010) | United States | n.a. | Age 16.3 years | 89 | ID; IP | - Seeing ads in broadcast and print media | - Broadcast media: radio, TV, Internet | - Past-month quantity | - Positive association between seeing ads and outcome | 6 |

| - Print media: Magazines, newspapers, billboards, retail displays | - No associations when other influences (e.g., peer influence) were included in the model | |||||||||

| Lin et al. (2012) | New Zealand | n.a. | Age 13–14 years | 2,538 | ID; IP | - Awareness of marketing channels | - Marketing channels: TV/ movies; large posters/ billboards; in-store signs/ posters; newspapers/ magazines; merchandise items; special price offers; celebrity endorsement; unusual product design; sport, music event, or TV sponsorship; emails; websites; screensavers; social networking sites (composite) | - Past-year drinking status | - Positive associations between marketing awareness, engagement with traditional marketing, and brand allegiance with past-year drinking status | 7 |

| - Engaging with traditional alcohol marketing | - Traditional alcohol marketing: free branded gifts; price promotions; promotional mail/emails mentioning brands; clothing or other branded items (composite) | - Past-year frequency | - Positive association between brand allegiance and past-year frequency and typical quantity | |||||||

| - Brand allegiance | - Typical quantity | |||||||||

| McClure et al. (2013a) | United States | 2011 | Age 15–20 years | 2,012 | ID; IP | - Recalling ads | - TV | - Lifetime drinking status | - Positive association between recalling ads and lifetime drinking status | 7 |

| - Liking ads | - Lifetime HED status | |||||||||

| - Identifying brands | ||||||||||

| McClure et al. (2013b) | United States | 2009 | Age 15–20 years | 1,734 | ID; IP | - Having favorite alcohol ad | - Alcohol-branded merchandise | - Past-month HED frequency | - Positive association between owning alcohol-branded merchandise and outcome | 8 |

| - Owning alcohol-related merchandise | - Movies | |||||||||

| - Watching movies with alcohol-brand appearances | ||||||||||

| Mittmann et al. (2009) | United States | n.a. | Age 21 years | 1,126 | ID; EV | - Marketing and promotion awareness before 21st birthday | - Ads or promotions related to 21st birthday | - Quantity on 21st birthday | - Positive association between participating in promotions and outcome | 7 |

| - Participating in promotions on 21st birthday | ||||||||||

| Morgenstern et al. (2011) | Germany | 2008 | Age 10–17 years | 3,415 | ID; IP | - Seeing specific ads; recalling brands for specific ads (combined measure) | - TV | - Lifetime drinking status | - Positive associations | 8 |

| - Frequency of current drinking | ||||||||||

| - Lifetime HED frequency | ||||||||||

| Naimi et al. (2016) | United States | 2011–2012 | Age 13–20 years | 1,031 | ID; IP; EV | - Watching programs weighted by Gross Rating Points | - TV | - Quantity of past-month brand-specific consumption | - Positive association between exposure to alcohol ads and outcome | 8 |

| - Low exposure: Ad exposure < 300 adstock units | - In stratified analyses, associations were observed among females but not males and among 18- to 20-year-olds | |||||||||

| - High exposure: Ad exposure ≥ 300 adstock units | ||||||||||

| O’Brien et al (2014). | United Kingdom | 2010–2012 | Age 19.97 (1.78) years | 1,658 | ID; EV | - Receiving sponsorship | - Alcohol industry sponsorship for team, club, or individual player | - Alcohol consumption | - Positive associations between receiving sponsorship for team, club, team and club, and personal combinations with alcohol consumption | 8 |

| - Hazardous drinking | - Positive association between receiving sponsorship for team and club and personal combinations with hazardous drinking | |||||||||

| Paek & Hove (2012) | United States | 2001 | Age 19.18 (7.6) years | 5,472 | ID; IP; EV | - Participating in promotions | - Price promotions | - Composite drinking scale of lifetime HED frequency, past-2-week HED frequency, self-described drinking pattern, past-month frequency, past-month quantity | - Positive association | 8 |

| Peltzer et al. (2016) | Cambodia | 2013 | 6th–12th grade Age 15.7 (1.8) years | 3,806 | ID; IP | - Seeing ads | n.a. | - Past-month drinking status | - Positive associations between seeing ads with past-month alcohol use status and lifetime drunkenness frequency | 8 |

| - Lifetime drunkenness status | ||||||||||

| - Lifetime problem-drinking status | ||||||||||

| Pinsky et al. (2007) | Brazil | 2006 | Age 14–25 years | 1,091 | ID | - Seeing or hearing ads | - Unspecified media | - Frequency (no time frame) | - Positive associations | 7 |

| - Participating in promotions | - Promotion venues: bars, restaurants, internet | - Heavy drinking (no time frame) | ||||||||

| Pinsky et al. (2010) | Brazil | 2005–2006 | Age 14–25 years | 1,091 | ID | - Seeing ads | - Ads: billboards, magazines, newspapers, TV, radio, Internet (composite) | - High vs. low intensity drinking | - Positive association between seeing alcohol promotions and alcohol use | 9 |

| - Seeing or participating in promotions | - Promotions: pubs, restaurants, Internet (composite) | |||||||||

| - Seeing beer ads at POS | - POS: pubs, bakeries, supermarkets, restaurants, music shows, sports events (composite) | |||||||||

| Primack et al. (2014) | United States | 2010–2011 | Age 15–23 years | 2,541 | ID; IP | - Liking and owning music with alcohol branding | - Music | - Lifetime drinking status | - Positive associations between liking and owning alcohol branded music and brand recall with lifetime drinking status and lifetime HED status | 8 |

| - Recalling brands | - Lifetime HED status | |||||||||

| - HED frequency | ||||||||||

| - Lifetime problem-drinking status | ||||||||||

| Ross et al (2014). | United States | 2011–2012 | Age 13–20 years | 1,031 | ID; IP; EV | - Seeing brand-specific ads | - TV | - Past-month brand-specific drinking status | - Positive associations | 8 |

| - Past-month number of brands consumed | ||||||||||

| Ross et al (2014). | United States | 2011–2012 | Age 13–20 years | 1,031 | ID; EV | - Watching programs weighted by brand-specific Gross Rating Points | - TV | - Past-month brand-specific consumption | - Positive associations | 8 |

| Saffer & Dave (2003) | United States | - Monitoring the Future (MTF) dataset: 1996–1998 | - MTF: 8th, 10th, 12th grade | - MTF ≈ 63,000 | - MTF: ID | - Local alcohol advertising (composite) | - TV; radio; magazines; newspapers; outdoor advertising | - Past-year drinking status | In the full samples: | 8 |

| - National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY): 1997–1998 | - NLSY: Age 12–16 years | - NLSY ≈ 10,000 | - NLSY: ID; IP | - Local beer price | - Past-month drinking status | - Positive associations between alcohol ads and outcomes | ||||

| - Past-2-week HED | - Negative associations between alcohol price and outcomes | |||||||||

| Subgroup analyses: | ||||||||||

| - No associations between alcohol ads and past-month drinking and between alcohol price and past-month drinking or past-2-week HED for African Americans | ||||||||||

| - No associations between alcohol ads and past-month drinking or past-2-week HED and between alcohol price and past-month drinking or past-2-week HED for males | ||||||||||

| Sanhueza et al. (2013) | Chile | 2007–2010 | Age 11.9–17.8 years | 909 | ID | - Seeing ads | - TV; radio; billboards; magazines; newspapers (composite) | - Lifetime problem-drinking status | - Positive association | 7 |

| Siegel et al. (2016) | United States | 2011–2012 | Age 13–20 years | 1,031 | EV | - Gross Rating Points population-level youth exposure to brandspecific ads | - TV | - Past-month brand-specific consumption | - Positive associations | 8 |

| - Magazines | ||||||||||

| Strickland (1982) | United States | 1980 | 7th, 9th, 11th grade | 1,187 | ID | - Seeing ads | - TV | - Quantity–frequency index per day | - No association | 9 |

| Swahn et al. (2011) | Zambia | 2004 | Age 11–16 years | 2,257 | ID; EV | - Seeing ads | - Billboards | - Lifetime drunkenness status | - Positive associations between free samples from industry representatives and outcomes | 9 |

| - Being offered promotion | - Free samples from industry representative | - Lifetime problem-drinking status | ||||||||

| Swahn et al. (2013) | Philippines | 2011 | Age 11–16 years | 5,290 | ID; IP | - Seeing brand names | - Seeing alcohol brand names on TV | - Lifetime drunkenness status | - Positive associations between seeing public ads, seeing newspapers/magazines, and being provided free alcohol with outcome | 8 |

| - Seeing ads | - Public ads (sports events, fairs, concerts) | |||||||||

| - Participating in promotions | - Billboards | |||||||||

| - Owning alcohol-related merchandise | - Newspapers/magazines | |||||||||

| - Provided free alcohol | ||||||||||

| - Owning alcohol-related merchandise | ||||||||||

| Thomsen et al. (2004) | United States | 2002 | Age 11–14 years | 253 | ID; IP | - Attending alcohol-sponsored event | - Alcohol industry event | - Past-month drinking status | - Positive association between attending alcohol industry event and outcome among females but not males | 8 |

| Unger et al. (2003) | United States | n.a. | 8th, 10th grade | 591 | ID | - Watching programs with ads (sports) | - TV | - Lifetime drinking status | Adjusting for all exposure measures in the model: | 9 |

| - Seeing ads | - Lifetime drunkenness status | - Positive associations between media receptivity and outcomes | ||||||||

| - Media receptivity | - Past-month drinking status | - Positive associations between recall of brand names with lifetime drunkenness and past-month alcohol use | ||||||||

| - Recalling brands | - Past-month drunkenness status | - Positive associations between liking ads and outcomes | ||||||||

| - Negative association between recalling brands and past-month drunkenness | ||||||||||

| - Liking ads | ||||||||||

| - Recalling ads | ||||||||||

| Vantamay (2009) | Thailand | 2008 | Age 18–24 years | 1,200 | ID; IP; EV | - Seeing ads | n.a. | - Past-year frequency | - Positive association | 8 |

| Wyllie et al. (1998) | New Zealand | 1993 | Age 10–17 years | 447 | ID; IP | - Liking ads | - TV | - Frequency of current drinking | - No association | 9 |

Notes: Key findings column highlights significant findings only when there are multiple exposures and outcomes. In the control variable column, ID = individual level; IP = interpersonal level; EV = environmental level controls. n.a. = not available; HED = heavy episodic drinking; POS = point of sale; SMS = short message service; MMS = multimedia messaging service. Bolded text in the marketing exposure column represent objective measures of exposure (compared with nonbolded perceived measures). Quality-assessment scores ranged from 5 to 10.

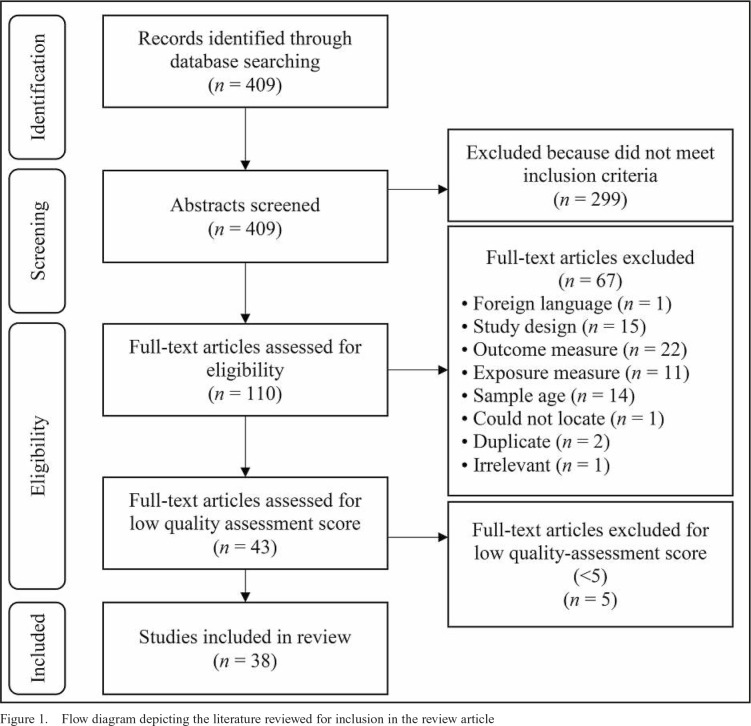

Using these inclusion criteria, titles and abstracts of the 409 studies were first screened for inclusion independently by two or three of the researchers (LJF, SLK, JWG, AB, and EK) using Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016). Disagreements were resolved through discussion. A total of 110 articles were selected through the initial screening for a full-text review. Full-text review of these articles resulted in 43 studies that met all the eligibility criteria.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Extracted data included study authors, publication year, data-collection year, country, participants’ age, sample size, definition and operationalization of the outcome measures, definition and operationalization of alcohol marketing exposure measures, covariates included in the analyses, and key findings related to the associations among exposure and outcome measures in the fully adjusted models. We used a combination of criteria from the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies and the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale to assess the quality of the articles (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.; Wells et al., 2000). Studies were scored on a scale of 0–10, with higher scores indicating greater quality. Five studies with quality scores below 5 were excluded, leaving 38 studies in the review (Figure 1). The average quality-assessment score of included studies was 8.00 (SD = 0.77; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram depicting the literature reviewed for inclusion in the review article

Analytic strategy

All 110 full-text articles were examined independently by two reviewers (LJF, SLK, or JGW) who extracted data from each study and assessed the study quality. Reviewed articles were discussed and discrepancies in extracted data and quality-assessment scoring were resolved by consensus among reviewers. Using extracted data, results of eligible studies were stratified and organized by alcohol use outcome and marketing exposure type. We conducted the review in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Moher et al., 2010).

To summarize findings, several data reduction techniques were used. First, findings were grouped by alcohol use outcomes to include lifetime, past-year, past-month or current, and heavy or problematic alcohol use categories. The heavy or problematic alcohol use outcome category included findings from a range of referenced time frames (e.g., past-2-week HED or past-month HED). Further, two studies that assessed very unique alcohol use outcomes—number of 21st birthday drinks consumed (Mittmann et al., 2009) and a composite measure of many different alcohol use behaviors (Paek & Hove, 2012)—are not discussed in the text. Second, given the range of and diversity in the assessed types of alcohol marketing exposures used, we collapsed types of marketing exposures into three categories: (a) alcohol advertising (e.g., seeing ads or marketing awareness, Gordon et al., 2011; Strickland, 1982), (b) alcohol promotion (e.g., receiving sponsorship or attending alcohol-sponsored events, Strickland, 1982; Thomsen et al., 2004), and (c) ownership of alcohol-related merchandise (de Bruijn et al., 2016; McClure et al., 2013a). This categorization allowed us to draw conclusions about the role of different marketing exposure types on various alcohol use outcomes. Last, we summarized findings across the types of media examined (e.g., television, billboards, etc.). Given the limited number of studies that conducted subgroup analyses (e.g., Jones & Magee, 2011; Naimi et al., 2016; Saffer & Dave, 2003), we reviewed main or whole sample findings because there was too little information to draw reliable conclusions on the relationship between marketing exposure and alcohol use outcomes among subgroups.

Results

Table 1 provides information about and a brief summary of key findings for each of the 38 included studies. Most research was conducted in the United States (47%) or Europe (16%). Data were collected from 1980 to 2015, and samples ranged from 89 to ∼63,000 participants. Of the studies in the review, 11 used objective measures of alcohol marketing exposure (e.g., ad stock; Naimi et al., 2016) compared with 27 studies that relied only on perceived exposures (e.g., recalling ads; McClure et al., 2013b).

Lifetime alcohol use

In total, 10 studies from 8 countries (Australia, Brazil, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Scotland, United States) assessed 32 different associations between marketing exposures and lifetime drinking outcomes. These studies covered many different types of media and used different measures to assess exposure to alcohol marketing.

Alcohol advertising.

Positive associations were found across different media types including advertising on television, in magazines and newspapers, in mixed media types, in music, at bottle shops and the point of sale, and in bars and pubs (Austin & Nach-Ferguson, 1995; de Bruijn et al., 2016; Gordon et al., 2011; Hurtz et al., 2007; Jones & Magee, 2011; McClure et al., 2013a; Morgenstern et al., 2011; Pinsky et al., 2007; Primack et al., 2014; Unger et al., 2003). A few of these studies (Austin & Nach-Ferguson, 1995; Jones & Magee, 2011; McClure et al., 2013a; Unger et al., 2003) identified positive associations for advertising for some types of media but not others. For example, an Australia-based study found positive associations between lifetime drinking and exposure to alcohol advertising in magazines, in bottle shops or at the point of sale, and in bars and pubs but not with exposure to alcohol advertising on television or billboards (Jones & Magee, 2011).

Other studies identified positive associations between exposure to alcohol advertising and lifetime alcohol use when using some but not all types of exposure measures. For example, a study conducted in the United States found positive associations between lifetime alcohol use and exposure to alcohol advertising when considering media receptivity or liking alcohol advertising but not when considering seeing alcohol advertising as an exposure measure (Unger et al., 2003). Across these associations, 21 positive relationships compared with 11 null association relationships were observed, suggesting moderate evidence for the association between alcohol advertising exposures across media types and lifetime alcohol use outcomes among young people. No unexpected direction associations were observed for these outcomes.

Alcohol promotion and owning alcohol-related merchandise.

Results related to associations between lifetime alcohol use and alcohol promotion or owning alcohol-related merchandise were more consistent. Across all six studies assessing these relationships, positive associations were observed for alcohol promotion (Gordon et al., 2011; Jones & Magee, 2011; Pinsky et al., 2007) and self-reported ownership of alcohol-related merchandise (de Bruijn et al., 2016; Hurtz et al., 2007; Primack et al., 2014). For example, in a study conducted in Scotland, positive associations were found between participating in alcohol promotions and lifetime alcohol use among 12- to 14-year-old participants (Gordon et al., 2011). No null or unexpected direction findings were observed for this outcome suggesting strong evidence for the association of these marketing exposures with young peoples’ lifetime alcohol use behaviors.

Past-year alcohol use

We identified five studies from four countries (Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, United States) that assessed 19 different associations between alcohol marketing exposures and past-year alcohol use outcomes. These studies assessed different types of media and used a range of exposure measures.

Alcohol advertising.

Positive associations were found across television, bar or pub, and mixed media advertising types (Jones & Magee, 2011; Lin et al., 2012; Saffer & Dave, 2003; Vantamay, 2009). For example, a study in New Zealand found a positive association between brand allegiance and past-year frequency and typical-quantity alcohol use (Lin et al., 2012). However, many of these articles also found null associations for other media types or when using different measures of exposure. For example, this same study found no associations between alcohol advertising and past-year frequency or quantity when assessing marketing awareness or engagement with traditional marketing (Lin et al., 2012). Across the five studies, the assessed associations of similar positive relationships (n = 9) compared with null associations (n = 10) suggest inconclusive evidence for the relationship between alcohol advertising across media types and past-year alcohol use outcomes among young people. No unexpected direction associations were observed for these outcomes.

Alcohol promotion and owning alcohol-related merchandise.

None of the studies included in our review examined the relationship between ownership of alcohol-related merchandise and past-year alcohol use. The only study examining alcohol promotion found a null association. Specifically, this single study from Australia found no association between seeing promotional materials and past-year alcohol use frequency (Jones & Magee, 2011).

Past-month and current alcohol use

The majority of studies included in this review assessed past-month or current alcohol use outcomes. In total, 21 studies from seven countries (Australia, Brazil, Cambodia, Germany, New Zealand, United Kingdom, United States) assessed 52 associations between alcohol marketing exposures and past-month or current alcohol use outcomes.

Alcohol advertising.

In studies that assessed young peoples’ exposure to alcohol advertising, positive relationships were found across media types including television, magazines and newspapers, movie, mixed media, bar and pub, internet, and brand allegiance (Atkin et al., 1984; Faria et al., 2011; Faulkner et al., 2017; Gunter et al., 2009; Jones & Magee, 2011; Kinard & Webster, 2010; Lin et al., 2012; Morgenstern et al., 2011; Naimi et al., 2016; Peltzer et al., 2016; Ross et al., 2014a, 2015; Saffer & Dave, 2003; Siegel et al., 2016; Unger et al., 2003). For example, a British study reported positive associations between seeing alcohol advertising on television, in movies, and in magazines with past-month drinking frequency (Gunter et al., 2009). Similarly, two American studies found positive associations between seeing alcohol advertising on television, assessed using ad stock data, and past-month brand-specific consumption frequency (Ross et al., 2015) and quantity (Naimi et al., 2016). As with other alcohol use outcomes, many of the studies also found null associations for other media types or when using different measures of exposure. Across the assessed associations, observed positive relationships (n = 31) were more numerous than null associations (n = 20). Taken together, moderate evidence for the relationships between alcohol advertising exposures and past-month and current alcohol use among young people was observed.

Alcohol promotion and owning alcohol-related merchandise.

Four studies assessed associations between past-month or current alcohol use and exposure to alcohol promotion (Clapp & McDonnell, 2000; Faulkner et al., 2017; Jones & Magee, 2011; O’Brien et al., 2014). Whereas one of these studies reported positive associations between alcohol promotion and past-month alcohol use (O’Brien et al., 2014), two others observed null findings (Faulkner et al., 2017; Jones & Magee, 2011). For example, a British study found that receiving alcohol industry sponsorship for a team or club was positively associated with young people’s current alcohol consumption (O’Brien et al., 2014). In contrast, a recent study in Australia found no association between sponsorship awareness and past-month drinking status among 12- to 17-year-old adolescents (Faulkner et al., 2017). One study found a negative relationship between perceived alcohol promotion on campus and past-month alcohol use frequency among college students (Clapp & McDonnell, 2000). The limited evidence from different countries using different measures makes it difficult to summarize findings about associations between alcohol promotion and past-month alcohol use. Focusing on owning alcohol-related merchandise, the two studies that assessed this marketing exposure found positive associations between owning alcohol-related merchandise and past-month alcohol status, using samples in the United States and Australia (Faulkner et al., 2017; Hurtz et al., 2007).

Heavy or problematic alcohol use

Sixty-one different associations between alcohol marketing exposures and heavy or problematic alcohol use outcomes were reported in 18 studies included in our review. Samples from 14 countries (Australia, Brazil, Cambodia, Chile, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, New Zealand, Philippines, Thailand, United Kingdom, United States, Zambia) and many different types of media and measures of exposures were assessed.

Alcohol advertising.

Of the studies that assessed alcohol advertising, positive associations were found across television, magazines and newspapers, music, and mixed media (Critchlow et al., 2016; de Bruijn et al., 2016; Faulkner et al., 2017; Kheokao et al., 2013; Morgenstern et al., 2011; Peltzer et al., 2016; Pinsky et al., 2007; Primack et al., 2014; Saffer & Dave, 2003; Sanhueza et al., 2013; Swahn et al., 2013; Unger et al., 2003). For example, a study of adolescents in four European countries (i.e., Germany, Italy, Netherlands, and Poland) found a positive association between self-reported exposure to alcohol advertising on television and past-month HED status (de Bruijn et al., 2016). However, null associations were also reported considering these types of media or using different measures of exposures (Huckle et al., 2008; Kheokao et al., 2013; McClure et al., 2013a, 2013b; Peltzer et al., 2016; Pinsky et al., 2010; Swahn et al., 2011; Swahn et al., 2013; Unger et al., 2003). For example, a study conducted in Thailand found positive associations between high levels of alcohol use with media exposure, information reception, and skepticism but no association with desirability of or identification with alcohol advertising (Kheokao et al., 2013). Further, one study found a negative relationship between television advertising exposure and heavy or problematic alcohol use outcomes (Unger et al., 2003). Across the assessed associations, observed positive relationships (n = 32) were only slightly more common compared with the null associations (n = 28), suggesting mixed evidence for the relationship between alcohol marketing and heavy drinking or problematic alcohol use outcomes in cross-sectional research.

Alcohol promotion and owning alcohol-related merchandise.

Positive associations for alcohol promotion (O’Brien et al., 2014; Pinsky et al., 2007, 2010; Swahn et al., 2011, 2013) and ownership of alcohol-related merchandise (de Bruijn et al., 2016; Faulkner et al., 2017; McClure et al., 2013a; Primack et al., 2014) were also observed. In a study in Zambia, having been offered free samples of alcohol from an industry representative was associated with lifetime drunkenness or problem-drinking status (Swahn et al., 2011). In an American study, a positive association between owning alcohol-branded merchandise and past-month frequency of HED was reported (McClure et al., 2013a). Only one study reported a null association between alcohol promotion (i.e., sponsorship awareness) and past-week risky drinking (Faulkner et al., 2017). Two studies—one in the Philippines (Swahn et al., 2013) and one in United States (Primack et al., 2014)—reported null associations between owning alcohol-related merchandise and heavy or problematic alcohol use outcomes. Taken together, considerable evidence for the association between alcohol promotion or owning alcohol-related merchandise and heavy or problematic alcohol use outcomes among young people was observed.

Discussion

The goal of this systematic review was to summarize cross-sectional research investigating the relationship between alcohol marketing exposures and alcohol use behaviors among young people. Across alcohol use outcomes, marketing exposure types, and different media sources, our findings suggest that, overall, the cross-sectional research provides more evidence for a positive relationship between alcohol marketing exposure and alcohol use behavior among adolescents and young adults than negative or null evidence. In other words, the cross-sectional evidence supports that alcohol marketing exposure may be associated with young peoples’ alcohol use behaviors. In general, relationships for alcohol promotion and owning alcohol-related merchandise exposures were found to be more consistently related to alcohol consumption than for other marketing exposures. These positive associations were observed across the past four decades, in countries across continents, and with small and large samples.

Methodological issues have made it challenging to review, evaluate, and summarize findings. First, there was substantial variability in the types of alcohol outcomes, marketing exposure measures, and media sources assessed. Thus, summarizing across these diverse constructs made it difficult to draw firm conclusions about specific associations. Also, across the studies, there was often poor or inconsistent measurement of study constructs. Alcohol outcome measures, for example, varied substantially and were sometimes ambiguous, making it difficult to compare across the different studies. Media types were often inadequately described, arbitrarily grouped together, or inconsistently assessed.

Further, the issues surrounding measurement of marketing exposures were substantial. Some studies combined different exposure types (e.g., hours of media use, liking advertisements, owning of branded items) into a single measure, also making it difficult to interpret results and compare across studies. When these indicators are combined into summative measures, it may cloud the true nature of the relationship between marketing and alcohol use. For example, the marketing receptivity model (McClure et al., 2013a) suggests that some measures of exposure may be more proximal to behaviors than others. From this perspective, exposure to advertising per se is less closely associated with alcohol consumption than is recall of specific advertisements or ownership of branded items. Further, seeing advertisements on television may be experienced differently by youth than seeing advertisements on billboards or at the point of sale. Similarly, although some studies assessed exposure to media types individually (Jones & Magee, 2011), others combined these media types (Gordon et al., 2011). Although this approach may help us understand the potential cumulative relationship between marketing exposure and behavior, it makes it difficult to inform intervention or policy aimed at addressing specific media exposures or types. Last, this literature was limited by the potential systematic bias in studies that rely on young peoples’ recall of media content (e.g., those predisposed to drink may attend more closely to marketing).

Moving forward, researchers need to more carefully conceptualize and operationalize marketing exposure. Greater uniformity will help the literature become substantially more robust and conclusive. Further, future research should continue to carefully document the nature of industry alcohol marketing in both traditional and new media. Detailing the nature and source of messages that circulate through social media or internet platforms is essential and will help support effective policy development (Biglan et al., 2019). See Noel et al. (2020) in this issue for a review of exposure to digital alcohol marketing and alcohol use.

Findings from this review may have important policy and prevention implications. Current voluntary codes for the alcohol industry (e.g., Beer Institute, 2018) that are designed to limit underage youth’s exposure to marketing may be insufficient (Babor, 2010). It may be important to adjust these industry standards or assign external agencies to assess compliance with them. Indeed, research suggests young people are frequently exposed to alcohol advertising (e.g., Jernigan et al., 2005). Evidence from this review supports these concerns as it highlights the wealth of research that demonstrates positive associations between diverse marketing exposures across media types and alcohol use behaviors among vulnerable populations. Results of this review also highlight the need to eliminate or reduce youth exposure to alcohol promotion, such as free sampling or owning alcohol-related merchandise. Future policies aimed at regulating alcohol marketing to a greater extent may have important short- and long-term public health implications for reducing underage or problematic alcohol use among young people. Further, prevention interventions to reduce potential effects of exposure to alcohol marketing on young peoples’ alcohol use and problems may be important. For example, media campaigns or other interventions can be tailored to reduce effects of such exposures.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, notwithstanding the observed correlations of advertising exposure with alcohol use behaviors, cross-sectional survey studies are limited by the correlational nature of the data. It is possible to determine only that there is a relationship between media exposure and alcohol use behaviors but not the directionality of these relationships or whether they are spurious and the result of common predisposing factors that influence both choice of media and alcohol use. Experimental and longitudinal work is needed to better demonstrate potential causal relationships and mechanisms. Second, although our search strategy was expansive, it may be possible that additional studies were not included in this review, particularly unpublished research. Publication bias is a potential issue that needs to be considered, as a bias toward publishing studies showing a positive association between alcohol marketing and alcohol use may result in overestimated size and consistency of these associations (Nelson, 2011). That our systematic review found a range of effect sizes, including null findings, somewhat mitigates this concern. Third, given the range of study outcomes, exposures, and media types, it was not possible to calculate and determine overall effect sizes across the various studies (e.g., meta-analysis). Last, we used a quality-assessment system to ensure that only high-quality studies were included to make more robust conclusions, therefore limiting included studies.

Conclusion

The current systematic review study of cross-sectional research found support for the claim that, in general, exposure to alcohol marketing is associated with diverse alcohol use behaviors among adolescents and young adults. Although these positive associations were observed, the cross-sectional literature is plagued with challenges related to construct clarity and measurement. Nonetheless, evidence from this review may have important research and policy implications for researchers, stakeholders, practitioners, and public health advocates.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Joel W. Grube has been supported within the past 3 years by funding from the alcohol industry to evaluate industry-sponsored programs to reduce alcohol sales to minors and other alcohol-related harms. No other conflicts of interest exist for the other authors.

Footnotes

This research was supported by grants P60-AA006282, T32-AA014125, and R01 AA021347 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or NIH.

References

- Atkin C., Hocking J., Block M. Teenage drinking: Does advertising make a difference? Journal of Communication. 1984;34:157–167. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1984.tb02167.x. [Google Scholar]

- Austin E. W. The message interpretation process model. In: Arnett J. J., editor. Encyclopedia of children, adolescents, and the media (pp. 535–536) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Austin E. W., Chen M.-J., Grube J. W. How does alcohol advertising influence underage drinking? The role of desirability, identification and skepticism. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.017. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin E. W., Nach-Ferguson B. Sources and influences of young school-aged children’s general and brand-specific knowledge about alcohol. Health Communication. 1995;7:1–20. doi:10.1207/s15327027hc0701_1. [Google Scholar]

- Babor T., Caetano R., Casswell S., Edwards G., Giesbrecht N., Graham K., Rossow I. Alcohol: No ordinary commodity: Research and public policy. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Beer Institute. Advertising/marketing code and buying guidelines. 2018. Retrieved from https://www.beerinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/BEER-6735-2018-Beer-Ad-Code-Update-Brochure-for-web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Berey B. L., Loparco C., Leeman R. F., Grube J. W. The myriad influences of alcohol advertising on adolescent drinking. Current Addiction Reports. 2017;4:172–183. doi: 10.1007/s40429-017-0146-y. doi:10.1007/s40429-017-0146-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A., Van Ryzin M., Westling E. A public health framework for the regulation of marketing. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2019;40:66–75. doi: 10.1057/s41271-018-0154-8. doi:10.1057/s41271-018-0154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie R. J., O’Connell M. E., editors. Reducing underage drinking: A collective responsibility. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casswell S., Maxwell A. Regulation of alcohol marketing: A global view. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2005;26:343–358. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200040. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. J., Grube J. W., Bersamin M., Waiters E., Keefe D. B. Alcohol advertising: What makes it attractive to youth? Journal of Health Communication. 2005;10:553–565. doi: 10.1080/10810730500228904. doi:10.1080/10810730500228904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp J. D., McDonnell A. L. The relationship of perceptions of alcohol promotion and peer drinking norms to alcohol problems reported by college students. Journal of College Student Development. 2000;41:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Critchlow N., Moodie C., Bauld L., Bonner A., Hastings G. Awareness of, and participation with, digital alcohol marketing, and the association with frequency of high episodic drinking among young adults. Drugs: Education, Prevention, & Policy. 2016;23:328–336. doi:10.3109/09687637.2015.1119247. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruijn A., Engels R., Anderson P., Bujalski M., Gosselt J., Schreckenberg D., de Leeuw R. Exposure to online alcohol marketing and adolescents’ drinking: A cross-sectional study in four European countries. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2016;51:615–621. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agw020. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agw020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distilled Spirits Council of the United States . Media “buying” guidelines: Demographic data/advertisement placement guidelines. 2011. Retrieved from https://www.distilledspirits.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Enhanced-Expanded_Buying_Guidelines_Updated_5-26-11_to_reflect_new_demographic_standard.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Faria R., Vendrame A., Silva R., Pinsky I. Propaganda de álcool e associação ao consumo de cerveja por adolescentes [Association between alcohol advertising and beer drinking among adolescents] Revista de Saúde Pública. 2011;45:441–447. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102011005000017. doi:10.1590/S0034-89102011005000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner A., Azar D., White V. ‘Unintended’ audiences of alcohol advertising: Exposure and drinking behaviors among Australian adolescents. Journal of Substance Use. 2017;22:108–112. doi:10.3109/14659891.2016.1143047. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R., Harris F., Mackintosh A. M., Moodie C. Assessing the cumulative impact of alcohol marketing on young people’s drinking: Cross-sectional data findings. Addiction Research and Theory. 2011;19:66–75. doi:10.3109/16066351003597142. [Google Scholar]

- Grube J. W. Alcohol in the media: Drinking portrayals, alcohol advertising, and alcohol consumption among youth. In: Bonnie R., O’Connell M. E., editors. Reducing underage drinking: A collective responsibility, background papers [CD-ROM]. Committee on Developing a Strategy to Reduce and Prevent Underage Drinking. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter B., Hansen A., Touri M. Alcohol advertising and young people’s drinking. Young Consumers. 2009;10:4–16. doi:10.1108/17473610910940756. [Google Scholar]

- Huckle T., Huakau J., Sweetsur P., Huisman O., Casswell S. Density of alcohol outlets and teenage drinking: Living in an alcogenic environment is associated with higher consumption in a metropolitan setting. Addiction. 2008;103:1614–1621. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02318.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtz S. Q., Henriksen L., Wang Y., Feighery E. C., Fortmann S. P. The relationship between exposure to alcohol advertising in stores, owning alcohol promotional items, and adolescent alcohol use. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2007;42:143–149. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl119. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agl119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H., Ostroff J., Ross C. Alcohol advertising and youth: A measured approach. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2005;26:312–325. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200038. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S. C., Magee C. A. Exposure to alcohol advertising and alcohol consumption among Australian adolescents. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2011;46:630–637. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr080. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agr080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheokao J. K., Kirkgulthorn T., Yingrengreung S., Singhprapai P. Effects of school, family and alcohol marketing communication on alcohol use and intentions to drink among Thai students. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2013;44:718–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinard B. R., Webster C. The effects of advertising, social influences, and self-efficacy on adolescent tobacco use and alcohol consumption. Journal of Consumer Affairs. 2010;44:24–43. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2010.01156.x. [Google Scholar]

- King C., III, Siegel M., Ross C. S., Jernigan D. H. Alcohol advertising in magazines and underage readership: Are underage youth disproportionately exposed? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017;41:1775–1782. doi: 10.1111/acer.13477. doi:10.1111/acer.13477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin E. I., Caswell S., You R. Q., Huckle T. Engagement with alcohol marketing and early brand allegiance in relation to early years of drinking. Addiction Research and Theory. 2012;20:329–338. doi:10.3109/16066359.2011.632699. [Google Scholar]

- McClure A. C., Stoolmiller M., Tanski S. E., Engels R. C. M. E., Sargent J. D. Alcohol marketing receptivity, marketing-specific cognitions, and underage binge drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013a;37(Supplement 1):E404–E413. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01932.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure A. C., Tanski S. E., Jackson K. M., Sargent J. D. TV and internet alcohol marketing and underage alcohol use [Abstract] Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013b;37:13A. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittmann A., Lewis M. A., Neighbors C., Buckingham K. G., Jensen M. M. Environmental influences on 21st birthday drinking [Abstract] Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:246A. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery. 2010;8:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern M., Isensee B., Sargent J. D., Hanewinkel R. Exposure to alcohol advertising and teen drinking. Preventive Medicine. 2011;52:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.020. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi T. S., Ross C. S., Siegel M. B., DeJong W., Jernigan D. H. Amount of televised alcohol advertising exposure and the quantity of alcohol consumed by youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;77:723–729. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.723. doi:10.15288/jsad.2016.77.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J. P. Alcohol marketing, adolescent drinking and publication bias in longitudinal studies: A critical survey using meta analysis. Journal of Economic Surveys. 2011;25:191–232. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6419.2010.00627.x. [Google Scholar]

- Noel J. K., Babor T. F. Does industry self-regulation protect young people from exposure to alcohol marketing? A review of compliance and complaint studies. Addiction. 2017;112(Supplement 1):51–56. doi: 10.1111/add.13432. doi:10.1111/add.13432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel J. K., Babor T. F., Robaina K. Industry self-regulation of alcohol marketing: A systematic review of content and exposure research. Addiction. 2017;112(Supplement 1):28–50. doi: 10.1111/add.13410. doi:10.1111/add.13410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel J. K., Sammartino C. J., Rosenthal S. R. Exposure to digital alcohol marketing and alcohol use: A systematic review. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs, Supplement. 2020;19:57–67. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2020.s19.57. doi:10.15288/jsads.2020.s19.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien K. S., Ferris J., Greenlees I., Jowett S., Rhind D., Cook P. A., Kypri K. Alcohol industry sponsorship and hazardous drinking in UK university students who play sport. Addiction. 2014;109:1647–1654. doi: 10.1111/add.12604. doi:10.1111/add.12604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. doi:10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paek H.-J., Hove T. Determinants of underage college student drinking: Implications for four major alcohol reduction strategies. Journal of Health Communication. 2012;17:659–676. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.635765. doi:10.1080/10810730.2011.635765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K., Pengpid S., Tepirou C. Associations of alcohol use with mental health and alcohol exposure among school-going students in Cambodia. Nagoya Journal of Medical Science. 2016;78:415–422. doi: 10.18999/nagjms.78.4.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce H., Stafford J., Pettigrew S., Kameron C., Keric D., Pratt I. S. Regulation of alcohol marketing in Australia: A critical review of the Alcohol Beverages Advertising Code Scheme’s new Placement Rules. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2019;38:16–24. doi: 10.1111/dar.12872. doi:10.1111/dar.12872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky I., El Jundi S. A. R. J., Sanches M., Zaleski M. J. B., Laranjeira R. R., Caetano R. Exposure of adolescents and young adults to alcohol advertising in Brazil. Journal of Public Affairs. 2010;10:50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky I., Sanches M., Zaleski M., Laranjeira R., Caetano R. Exposure to alcohol advertising among youngsters in Brazil: Results from the 2006 Brazilian national alcohol survey [Abstract] Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:245A. [Google Scholar]

- Primack B. A., McClure A. C., Li Z., Sargent J. D. Receptivity to and recall of alcohol brand appearances in U.S. popular music and alcohol-related behaviors. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:1737–1744. doi: 10.1111/acer.12408. doi:10.1111/acer.12408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. S., Maple E., Siegel M., DeJong W., Naimi T. S., Ostroff J., Jernigan D. H. The relationship between brand-specific alcohol advertising on television and brand-specific consumption among underage youth. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014a;38:2234–2242. doi: 10.1111/acer.12488. doi:10.1111/acer.12488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. S., Maple E., Siegel M., DeJong W., Naimi T. S., Padon A. A., Jernigan D. H. The relationship between population-level exposure to alcohol advertising on television and brand-specific consumption among underage youth in the US. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2015;50:358–364. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv016. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agv016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. S., Ostroff J., Jernigan D. H. Evidence of underage targeting of alcohol advertising on television in the United States: Lessons from the Lockyer v. Reynolds decisions. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2014b;35:105–118. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2013.52. doi:10.1057/jphp.2013.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell C. A., Russell D. W., Grube J. W. Substance use and media. In: Sher K. J., editor. The Oxford handbook of substance use and substance use disorders (Vol. 1, pp. 625–649) New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Saffer H., Dave D. Alcohol advertising and alcohol consumption by adolescents. NBER Working Paper No. 9676. 2003 doi: 10.1002/hec.1091. https://www.nber.org/papers/w9676 Retrieved from . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanhueza G. E., Delva J., Bares C. B., Grogan-Kaylor A. Alcohol consumption among Chilean adolescents: Examining individual, peer, parenting and environmental factors. International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research. 2013;2:89–97. doi: 10.7895/ijadr.v2i1.71. doi:10.7895/ijadr.v2i1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent J. D., Cukier S., Babor T. F. Alcohol marketing and youth drinking: Is there a causal relationship, and why does it matter? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2020;(Supplement 19):5–12. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2020.s19.5. doi:10.15288/jsads.2020.s19.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M., Ross C. S., Albers A. B., DeJong W., King C., III, Naimi T. S., Jernigan D. H. The relationship between exposure to brand-specific alcohol advertising and brand-specific consumption among underage drinkers—United States, 2011-2012. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2016;42:4–14. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1085542. doi:10.3109/00952990.2015.1085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland D. E. Alcohol advertising: Orientations and influence. International Journal of Advertising. 1982;1:307–319. doi:10.1080/02650487.1982.11104863. [Google Scholar]

- Swahn M. H., Ali B., Palmier J. B., Sikazwe G., Mayeya J. Alcohol marketing, drunkenness, and problem drinking among Zambian youth: Findings from the 2004 Global School-Based Student Health Survey. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/497827. Article ID 497827. doi:10.1155/2011/497827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn M. H., Palmier J. B., Benegas-Segarra A., Sinson F. A. Alcohol marketing and drunkenness among students in the Philippines: Findings from the nationally representative Global School-based Student Health Survey. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1159. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen S. R., Rekve D., Lindsay G. B. Using “Bud World Party” attendance to predict adolescent alcohol use and beliefs about drinking. Journal of Drug Education. 2004;34:179–195. doi: 10.2190/YUPA-YTTQ-J0NH-YFHK. doi:10.2190/YUPA-YTTQ-J0NH-YFHK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.) Study quality assessment tools: Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. Retrieved from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Report to Congress on the prevention and reduction of underage drinking. 2017. Retrieved from https://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/sites/default/files/imce/users/u1743/stop_act_rtc_2017.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Unger J. B., Schuster D., Zogg J., Dent C. W., Stacy A. W. Alcohol advertising exposure and adolescent alcohol use: A comparison of exposure measures. Addiction Research and Theory. 2003;11:177–193. doi:10.1080/1606635031000123292. [Google Scholar]

- Vantamay S. Alcohol consumption among university students: Applying a social ecological approach for multi-level preventions. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2009;40:354–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells G. A., Shea B., O’Connell D., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M., Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000. Retrieved from http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/nosgen.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wine Institute. Code of advertising standards. 2011. Retrieved from https://www.wineinstitute.org/initiatives/issuesandpolicy/adcode/details. [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie A., Zhang J. F., Casswell S. Responses to televised alcohol advertisements associated with drinking behaviour of 10–17-year-olds. Addiction. 1998;93:361–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9333615.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9333615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]