Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study is to inform public health efforts to reduce alcohol-related harm by describing the alcohol marketing landscape. We review the size, structure, and strategies of both the U.S. national and global alcohol industries and their principal marketing activities and expenditures and provide a summary of public health responses.

Method:

Primary data were obtained from advertising and alcohol industry market research firms and were supplemented by searches of peer-reviewed literature, business press, and online databases on global business and trade.

Results:

Worldwide, alcohol sales totaled more than $1.5 trillion in 2017. Control of alcoholic beverage production and marketing is concentrated globally in the hands of a small number of firms. The oligopoly structure of the producing industry helps to generate high profits per dollar invested relative to other industries, which in turn fund marketing expenditures that function as barriers to entry by other firms. Advertising expenditures are high and advertising is widespread. Stakeholder marketing and corporate social responsibility campaigns assist in maintaining a policy environment conducive to extensive alcohol marketing activity. The most common regulatory response has been alcohol industry self-regulation; statutory public health responses have made little progress in recent years and have lagged behind industry innovation in digital and social marketing.

Conclusions:

Alcohol marketing is widespread globally and a structural element of the alcoholic beverage industry. Given the level of alcohol-related harm worldwide, global and regional recommendations and best practices should be used to guide policy makers in effective regulation of alcohol marketing.

In 2017, according to the market research provider Euromonitor, global retail sales of alcohol were estimated to be worth more than $1.5 trillion (Euromonitor International, 2018). The promotion of alcohol, its availability through retail and on-premise purchase, and its pricing create “alcohol environments” that are strongly associated with health consequences (Babor et al., 2010). Given the importance of these environments in shaping patterns and volume of alcohol consumption, those who stand to profit from alcohol consumption, particularly the largest producers and distributors of alcoholic beverages, play a significant role in shaping the alcohol consumption environment (Jernigan, 2009). Yet there is a strong public health interest in those environments as well: Alcohol use causes 3.3 million deaths per year worldwide, is the seventh leading cause of global death and disability, and is a component cause of more than 200 disease and injury conditions (World Health Organization, 2014). It is the leading cause of death for persons age 15–49 years worldwide (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2016) and is a carcinogen for which there is no safe level of consumption (Connor, 2017).

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that excessive alcohol use—defined as binge drinking (five or more drinks within 2 hours for men, four or more for women), underage drinking, and drinking during pregnancy—cost the economy $249 billion in 2010, or an estimated $2.05 per drink (Sacks et al., 2015). Although alcohol dependence is a significant addictive disorder affecting approximately 3.5% of the adult population ages 18 years and older in the United States, nearly eight times as many people—27.4% of the population—reported binge drinking in the past month (Esser et al., 2014).

Given the widespread nature of excessive alcohol use and alcohol problems, population-level interventions that influence the environments within which individuals make their choices about drinking are crucial to the prevention of these problems (Babor et al., 2010). The most effective and cost-effective interventions, according to the World Health Organization (2017), are increasing the price of alcohol as well as reducing and restricting both the physical availability and the marketing of alcohol.

Particularly with regard to the latter, because of the sheer size of the alcohol industry, and its role in shaping alcohol environments, it is crucial that the public health field understand the industry’s organization and monitor its principal marketing strategies. Because of the importance of marketing to global and national alcohol brands (Jernigan, 2000a), alcohol producers are the most active players in shaping marketing environments. Campaigns generally emanate from them and are then transmitted through their brand distributors. This article will begin by reviewing the size, structure, and marketing strategies of the global producers and the key players in the U.S. market, using the United States as a country case study to illustrate how general industry trends and practices play out in practice. Marketing campaigns originate with and emanate from the alcohol brand owners in each national market (Jernigan, 2000a), and so the primary focus in terms of marketing activities will be on the activities of those brand owners. Description of key marketing strategies will be followed by a description, in the U.S. market, of the roles played by wholesalers and craft brewers. We conclude with a discussion of public health responses both in the United States and globally.

This article will work from an inclusive definition of marketing published in a recent technical report from the Pan American Health Organization:

[Marketing] refers to any commercial communication or other action, including advertising, promotion, and sponsorship, that is designed to increase—or have the effect or likely effect of increasing—the recognition, appeal and/or consumption of alcoholic beverages and of particular new or existing alcohol brands or products. This includes the design of alcohol products, brand stretching (using an established brand for a new product in another product category), cobranding (collaboration between different brands with the same advertising goals), depiction of alcohol products and brands in entertainment media, corporate social responsibility activities undertaken by the alcohol industry, and the sale or supply of alcoholic beverages in educational and health settings (Pan American Health Organization, 2017, p. 6).

Method

The most reliable sources for data on alcohol industry marketing activities are market and advertising research firms that serve the alcohol industry. These data are available by purchase or subscription. This article relies primarily on data purchased or subscribed from Impact Databank, Beer Marketer’s Insights, Advertising Age’s AdAge Datacenter, Euromonitor, and The Nielsen Company (2019 © The Nielsen Company, NewYork, NY, data from 2013–2017 used under license, all rights reserved). These are supplemented in various sections by data available via the worldwide web on alcohol production and trade, business publications describing industry trends and strategy, government publications, and reference to reviews as well as single studies of alcohol marketing activities in the peer-reviewed literature.

Results

Global structure of the industry

In at least 34 countries, some kind of alcohol monopoly exists; however, most of these combine monopoly control at one or more levels (production, distribution, and retail) with some system of licensing private entities for the remainder of the trade (World Health Organization, 2014). Where private industry exists, as it does in most of the world, it often comprises three levels: producers, wholesalers, and retailers. In the United States, at the repeal of National Prohibition, to prevent vertical integration of the industry these levels were required to remain separate from each other in what has come to be known as the “three-tier system.”

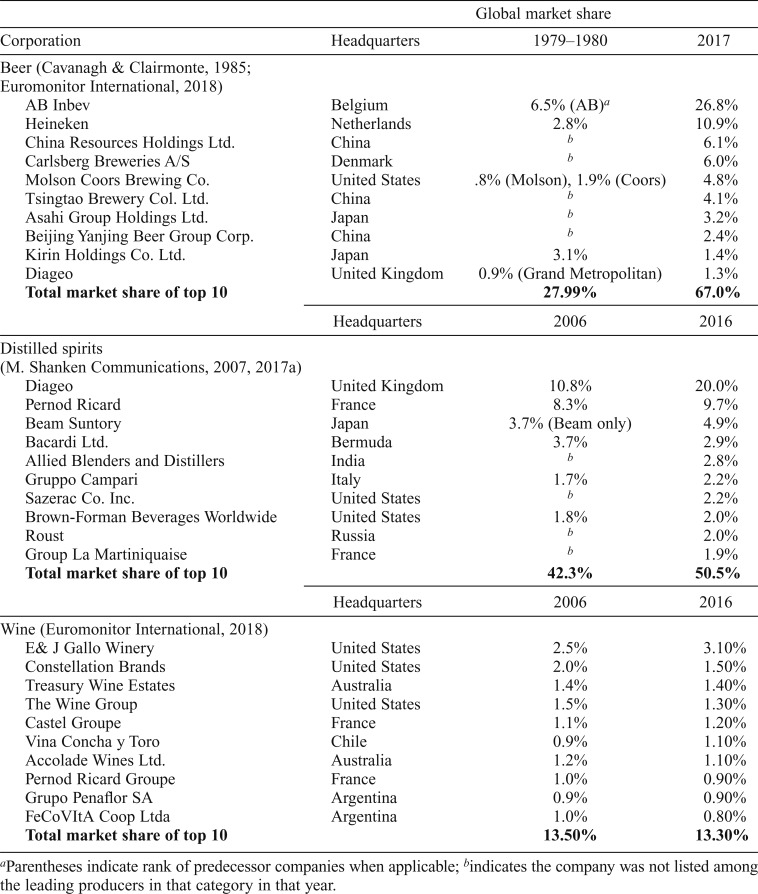

Globally, the largest and most dominant companies are the alcohol producers. Table 1 shows the 10 largest producers in the world in the categories of beer, distilled spirits, and wine by volume. Anheuser-Busch InBev (AB Inbev), a Belgian conglomerate run by Brazilians, took over the largest American beer company in 2008 and absorbed the second largest brewer in the U.S. market, MillerCoors, as part of its takeover of SABMiller in 2016. A single company now brews and markets more than a quarter of the world’s commercial beer.

Table 1.

Share of global market volume of the 10 leading multinational producers of alcoholic beverages, by category

| Global market share |

|||

| Corporation | Headquarters | 1979–1980 | 2017 |

| Beer (Cavanagh & Clairmonte, 1985; Euromonitor International, 2018) | |||

| AB Inbev | Belgium | 6.5% (AB)a | 26.8% |

| Heineken | Netherlands | 2.8% | 10.9% |

| China Resources Holdings Ltd. | China | b | 6.1% |

| Carlsberg Breweries A/S | Denmark | b | 6.0% |

| Molson Coors Brewing Co. | United States | .8% (Molson), 1.9% (Coors) | 4.8% |

| Tsingtao Brewery Col. Ltd. | China | b | 4.1% |

| Asahi Group Holdings Ltd. | Japan | b | 3.2% |

| Beijing Yanjing Beer Group Corp. | China | b | 2.4% |

| Kirin Holdings Co. Ltd. | Japan | 3.1% | 1.4% |

| Diageo | United Kingdom | 0.9% (Grand Metropolitan) | 1.3% |

| Total market share of top 10 | 27.99% | 67.0% | |

| Headquarters | 2006 | 2016 | |

| Distilled spirits (M. Shanken Communications, 2007, 2017a) | |||

| Diageo | United Kingdom | 10.8% | 20.0% |

| Pernod Ricard | France | 8.3% | 9.7% |

| Beam Suntory | Japan | 3.7% (Beam only) | 4.9% |

| Bacardi Ltd. | Bermuda | 3.7% | 2.9% |

| Allied Blenders and Distillers | India | b | 2.8% |

| Gruppo Campari | Italy | 1.7% | 2.2% |

| Sazerac Co. Inc. | United States | b | 2.2% |

| Brown-Forman Beverages Worldwide | United States | 1.8% | 2.0% |

| Roust | Russia | b | 2.0% |

| Group La Martiniquaise | France | b | 1.9% |

| Total market share of top 10 | 42.3% | 50.5% |

| Headquarters | 2006 | 2016 | |

| Wine (Euromonitor International, 2018) | |||

| E& J Gallo Winery | United States | 2.5% | 3.10% |

| Constellation Brands | United States | 2.0% | 1.50% |

| Treasury Wine Estates | Australia | 1.4% | 1.40% |

| The Wine Group | United States | 1.5% | 1.30% |

| Castel Groupe | France | 1.1% | 1.20% |

| Vina Concha y Toro | Chile | 0.9% | 1.10% |

| Accolade Wines Ltd. | Australia | 1.2% | 1.10% |

| Pernod Ricard Groupe | France | 1.0% | 0.90% |

| Grupo Penaflor SA | Argentina | 0.9% | 0.90% |

| FeCoVItA Coop Ltda | Argentina | 1.0% | 0.80% |

| Total market share of top 10 | 13.50% | 13.30% |

Parentheses indicate rank of predecessor companies when applicable;

indicates the company was not listed among the leading producers in that category in that year.

What is particularly dramatic in the case of beer is the rapid pace of consolidation in the global industry, going from the top-10 companies selling more than a quarter of the world’s beer in 1980 to two thirds of global beer in 2017 (Cavanagh & Clairmonte, 1985; Euromonitor International, 2018). Beer most closely adheres to what has been called the “marketing-driven commodity chain” in which two elements—the recipe and the marketing—are the most important links of the global production and marketing chain. Everything in between (procurement of raw materials, manufacturing, importing, and distribution) can be and is done by other companies, including rival brewers and distributors. It is the marketing that makes global beer brands distinctive: Even when done in collaboration with local marketers, this marketing remains under the control and direction of the global brand owners (Jernigan, 2000a).

Distilled spirits production is less concentrated. However, the presence of Diageo, the world’s largest distilled spirits producer, in both the beer and distilled spirits top-10 lists is testament to that company’s size and global reach in the alcohol industry as a whole. In distilled spirits alone, its share of the global market is double that of its nearest competitor.

Wine is the least concentrated of the three industry segments in terms of global ownership and reach. Within wineproducing countries, wine ownership is more concentrated than it is globally, but because wine has been historically and is still more of an artisanal than an industrial product (as opposed to beer and distilled spirits), wine production tends to be located in countries with a hospitable climate and a tradition of wine making.

Headquarters of corporations are not an accurate guide to the degree of globalization. Looking at exports by country, for instance, although China and Japan each house two of the world’s leading brewers, neither country is among the top-10 exporters of beer—that honor belongs almost entirely to European countries. European countries and the United States account for just over half of global beer exports, although Mexico is the leading beer exporter, with 26% of the world’s beer exports in 2017 (Workman, 2018a). France, Italy, and Spain—the traditional wine-producing countries—account for nearly half of wine exports, with the majority of wine-producing companies selling most of their wine domestically (Workman, 2018c). Among distilled spirits producers, the dominant exporters are Diageo, Pernod Ricard, and U.S.-based Constellation Brands and Brown Forman (Workman, 2018b).

Implications for marketing.

This concentration of market power in the global alcoholic beverage industry is important to any discussion of marketing because marketing expenditures play a reinforcing role in keeping a small number of companies dominant. The largest global companies are oligopolies and sometimes near-monopolies when it comes to national markets, again particularly in the case of beer. Oligopoly market shares mean oligopoly profits, and these companies are among the world’s more profitable large companies per dollar invested. Revenues of the nine largest companies by volume for which data were available totaled $141.2 billion (Euromonitor International, 2018). If these companies together were a country, they would be larger than the gross domestic product of all but 54 of the world’s nations.

According to tables published by NYU Stern, as of January 2019, alcoholic beverages were the eighth most profitable sector (measured by the ratio of net income to sales) of 94 global industries assessed—less profitable than tobacco (number 3) but significantly more profitable for instance than soft drinks (number 40) (Damodaran, 2019). Net earnings before income taxes in 2018 at AB InBev, the world’s largest alcohol company by volume, were $17.8 billion, or 31% of total revenues (AB InBev, 2019)—slightly less than tobacco giant Altria, at 37% (Altria Group, Inc., 2019) but more than Coca-Cola at 26% (The Coca-Cola Company, 2019).

This high level of profitability provides the financial support for a wide range of marketing activities around the world. High marketing spending creates a significant barrier to entry for new firms and products, which in turn helps to support the oligopoly structure and profits of the industry. The most visible form of marketing is advertising, particularly in the “measured media” of television, radio, and print. Globally, the U.S. publication Advertising Age tracks the world’s largest advertisers. Beer giant AB InBev is the ninth largest advertiser in the world, with global spending estimated at $6.2 billion in 2017. Also in the world’s top-100 advertisers are Suntory Holdings (number 25, Beam Suntory, $3.3 billion in 2017), Diageo (number 40, $2.5 billion in 2017), Heineken (number 42 $2.4 billion in 2017), Pernod Ricard (number 53, $2.0 billion in 2017), and Molson Coors (number 88, $1.3 billion in 2017). In contrast, Coca-Cola is number 17, spending $4 billion globally in 2017 (Advertising Age, 2019).

None of the global tobacco companies make it into Advertising Age’s top-100 spenders, most likely because of limitations on tobacco advertising in measured media in the wake of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (World Health Organization, 2005). This leaves alcohol companies among the dominant players in traditional advertising worldwide. Their brands, imagery, and slogans are ubiquitous on broadcast, in sports stadia, on billboards, and in print outlets, except in jurisdictions where these activities are restricted by law or regulation. This dominance is particularly evident in smaller countries. In 12 of the 94 countries for which Advertising Age reports the 10 highest spending advertisers, alcohol companies are among those 10, with AB InBev, Diageo, and Heineken frequently listed. As has previously been reported, Diageo has been increasing spending, on both advertising and acquisitions, in India (Esser & Jernigan, 2015), and all three companies have been actively advertising and marketing in sub-Saharan Africa (Jernigan & Babor, 2015).

As predicted by public health observers two decades ago, this active marketing presence in less-resourced countries reflects a global strategy to pursue growth and dominance in newer markets (Jernigan, 2000b, 2001). In those markets, alcohol companies have drawn on campaigns and tactics tested in the wealthier countries. Their advertising combines global themes with local cultural icons and festivals. In poor countries, smaller packages and sweepstakes make globalized leisure goods appear more affordable. In Latin America, their advertisements bedeck sidewalks and stadia, t-shirts and transit systems (Pan American Health Organization, 2016). In sub-Saharan Africa, their billboards can consume the entire sides or floors of buildings, becoming the dominant commercial imagery in the landscape, and they went beyond product placement to create a movie character who then starred in a full-length feature as a global action hero (de Bruijn, 2011; Jernigan & Obot, 2006).

In addition to traditional media, the global alcohol giants have the funds to support advertising and promotion of their products in digital and social media, and various “below-the-line” activities such as sponsorships, on-premise promotions, product placements, and stakeholder marketing. These will be described in further detail below.

Alcohol marketing in the United States

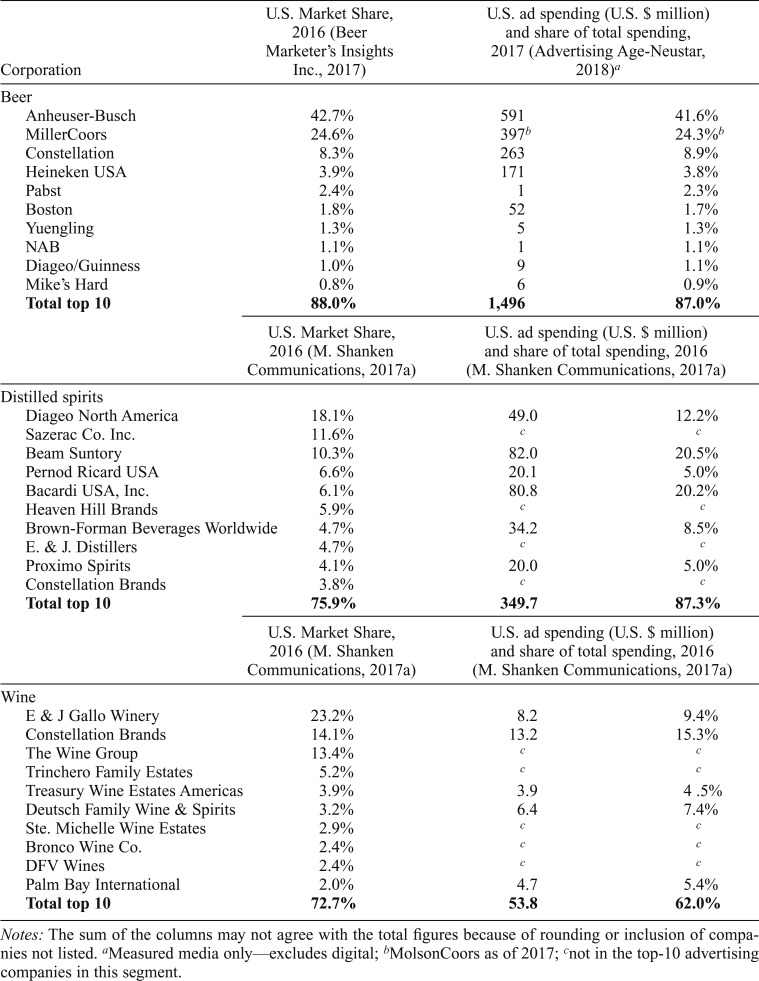

The United States offers a case study in regular marketing activity by the major producers. Focusing on a single market facilitates a closer look at the activities of particular companies and brands. Ownership in the United States is even more concentrated, extending across all three sectors. As shown in Table 2, the top-10 producing companies in each sector sell more than two thirds of the alcohol produced by that sector. In fact, the top-two beer companies (which merged in October 2016), the leading three wine companies, and the largest five distilled spirits companies sell more than half of the alcohol in their sector.

Table 2.

Share of U.S. market volume and advertising spending of the 10 leading producers of alcoholic beverages, by category

| Corporation | U.S. Market Share, 2016 (Beer Marketer’s Insights Inc., 2017) | U.S. ad spending (U.S. $ million) and share of total spending, 2017 (Advertising Age-Neustar, 2018)a | |

| Beer | |||

| Anheuser-Busch | 42.7% | 591 | 41.6% |

| MillerCoors | 24.6% | 397b | 24.3%b |

| Constellation | 8.3% | 263 | 8.9% |

| Heineken USA | 3.9% | 171 | 3.8% |

| Pabst | 2.4% | 1 | 2.3% |

| Boston | 1.8% | 52 | 1.7% |

| Yuengling | 1.3% | 5 | 1.3% |

| NAB | 1.1% | 1 | 1.1% |

| Diageo/Guinness | 1.0% | 9 | 1.1% |

| Mike’s Hard | 0.8% | 6 | 0.9% |

| Total top 10 | 88.0% | 1,496 | 87.0% |

| U.S. Market Share, 2016 (M. Shanken Communications, 2017a) | U.S. ad spending (U.S. $ million) and share of total spending, 2016 (M. Shanken Communications, 2017a) | ||

| Distilled spirits | |||

| Diageo North America | 18.1% | 49.0 | 12.2% |

| Sazerac Co. Inc. | 11.6% | c | c |

| Beam Suntory | 10.3% | 82.0 | 20.5% |

| Pernod Ricard USA | 6.6% | 20.1 | 5.0% |

| Bacardi USA, Inc. | 6.1% | 80.8 | 20.2% |

| Heaven Hill Brands | 5.9% | c | c |

| Brown-Forman Beverages Worldwide | 4.7% | 34.2 | 8.5% |

| E. & J. Distillers | 4.7% | c | c |

| Proximo Spirits | 4.1% | 20.0 | 5.0% |

| Constellation Brands | 3.8% | c | c |

| Total top 10 | 75.9% | 349.7 | 87.3% |

| U.S. Market Share, 2016 (M. Shanken Communications, 2017a) | U.S. ad spending (U.S. $ million) and share of total spending, 2016 (M. Shanken Communications, 2017a) | ||

| Wine | |||

| E & J Gallo Winery | 23.2% | 8.2 | 9.4% |

| Constellation Brands | 14.1% | 13.2 | 15.3% |

| The Wine Group | 13.4% | c | c |

| Trinchero Family Estates | 5.2% | c | c |

| Treasury Wine Estates Americas | 3.9% | 3.9 | 4.5% |

| Deutsch Family Wine & Spirits | 3.2% | 6.4 | 7.4% |

| Ste. Michelle Wine Estates | 2.9% | c | c |

| Bronco Wine Co. | 2.4% | c | c |

| DFV Wines | 2.4% | c | c |

| Palm Bay International | 2.0% | 4.7 | 5.4% |

| Total top 10 | 72.7% | 53.8 | 62.0% |

Notes: The sum of the columns may not agree with the total figures because of rounding or inclusion of companies not listed.

Measured media only—excludes digital;

MolsonCoors as of 2017;

not in the top-10 advertising companies in this segment.

Implications for marketing.

This high level of concentration once again facilitates both oligopoly profits and economies of scale when it comes to advertising, giving the largest players an advantage. As Jain (1994) pointed out two decades ago, the sheer size of these companies means that their cost for advertising per drink sold is actually substantially lower than that of their competitors. This is most evident for beer, the most concentrated segment. The largest players dominate both sales and the measured media advertising environment, with (as shown in Table 2) the 10 leading beer producers selling approximately seven out of eight beers and accounting for seven out of every eight dollars spent on beer advertising in broadcast, print, and outdoor media. In distilled spirits, the 10 largest companies sell three-quarters of the liquor and again are responsible for approximately seven out of every eight dollars spent on advertising. The 10 leading wine producers are responsible for nearly three quarters of the wine sold in the United States, and account for three out of five dollars spent on wine advertising.

The most thorough accounting of alcohol companies’ marketing activity came from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission in 2014. Covering the year 2011, and based on subpoenaed information from 14 companies representing 79% of the volume of alcohol sold in the U.S. alcohol market, this report estimated total marketing expenditures in that year for these 14 companies at $3.45 billion. Of this, traditional media (television, radio, and print) accounted for 32% of spending; point-of-sale promotions (paid for by the major companies) 29%, promotional allowances to wholesalers and retailers nearly 5%, outdoor and transit almost 7%, digital and internet (nascent at that time) 8%, and entertainment and sports sponsorships 18%, with miscellaneous other activities (including spring-break promotions and in-cinema advertising and product placements) accounting for the rest (Federal Trade Commission, 2014).

Beer companies spend the most on advertising, by far, and the 2011 Federal Trade Commission figures cannot capture the huge investment they currently make in digital and social media. For the nation’s 200 largest advertisers, Advertising Age provides estimates broader than the traditional “measured media” (print, radio, and television), encompassing digital activities as well (these estimates were only available for the United States and not for global spending). The contrast between measured media spending and overall spending as estimated by Advertising Age gives a sense of the magnitude of other marketing activities, including digital: Anheuser-Busch was estimated to have spent $947 million on other marketing in 2017 in addition to the $595 million it spent in measured media, and Molson Coors spent $456 million above its measured media expenditures of $429 million (Advertising Age-Neustar, 2018). Furthermore, Advertising Age also estimates that, for all advertisers, digital spending has likely eclipsed other forms of spending; however, Advertising Age does not make any breakdown of these overall estimates available, so it is not possible to report further on this spending (Advertising Age-Neustar, 2018).

These dollars enable the major companies to use a wide range of marketing strategies, including target marketing focused on special populations such as women, racial and ethnic minorities, young adults, older adults, adherents of particular sports, and so on. Because of extensive legal protections for advertising as a form of speech in the United States, there are relatively few restrictions in law regarding what alcohol producers can do, and content analysis of print advertising has found few violations of these admittedly weak legal restrictions (Smith et al., 2014).

These general marketing activities form the backdrop for more specific strategies, discussed in greater detail below.

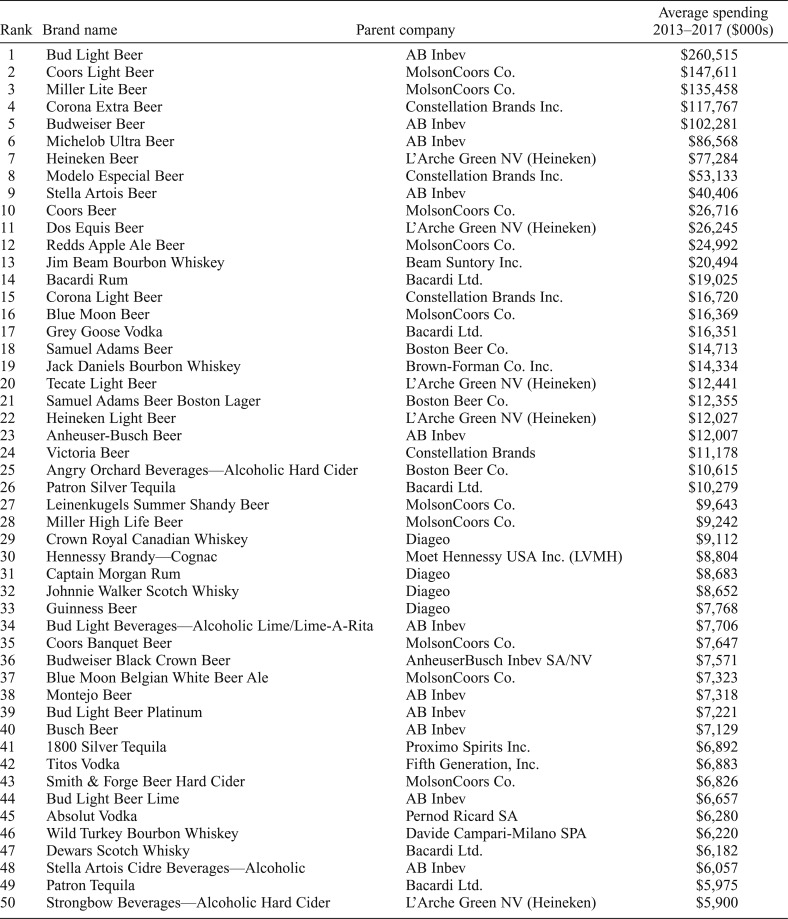

Branding

Alcohol marketing is branded. Branding—developing an identity for each brand and integrating that identity with the lifestyles and interests of target audiences (Aaker, 2014)—is a hallmark of modern marketing, and alcohol is no exception. Using available date from Nielsen, which include estimates for internet but not all digital marketing, Table 3 shows the average annual advertising expenditures for the 50 largest-spending alcohol brands in the United States between 2013 and 2017. It should be noted that these figures are “rate-sheet” numbers estimated by Nielsen from typical rates; actual spending is likely to vary based on negotiations each brand owner typically undertakes with media providers. Thirty-five of these brands come from just 5 companies, and the 12 top spenders are all beers.

Table 3.

Average annual spending for the 50 largest-spending alcohol brands in the United States, 2013–2017 (2019 © The Nielsen Company, New York, NY, data from 2013–2017 used under license, all rights reserved)

| Rank | Brand name | Parent company | Average spending 2013–2017 ($000s) |

| 1 | Bud Light Beer | AB Inbev | $260,515 |

| 2 | Coors Light Beer | MolsonCoors Co. | $147,611 |

| 3 | Miller Lite Beer | MolsonCoors Co. | $135,458 |

| 4 | Corona Extra Beer | Constellation Brands Inc. | $117,767 |

| 5 | Budweiser Beer | AB Inbev | $102,281 |

| 6 | Michelob Ultra Beer | AB Inbev | $86,568 |

| 7 | Heineken Beer | L’Arche Green NV (Heineken) | $77,284 |

| 8 | Modelo Especial Beer | Constellation Brands Inc. | $53,133 |

| 9 | Stella Artois Beer | AB Inbev | $40,406 |

| 10 | Coors Beer | MolsonCoors Co. | $26,716 |

| 11 | Dos Equis Beer | L’Arche Green NV (Heineken) | $26,245 |

| 12 | Redds Apple Ale Beer | MolsonCoors Co. | $24,992 |

| 13 | Jim Beam Bourbon Whiskey | Beam Suntory Inc. | $20,494 |

| 14 | Bacardi Rum | Bacardi Ltd. | $19,025 |

| 15 | Corona Light Beer | Constellation Brands Inc. | $16,720 |

| 16 | Blue Moon Beer | MolsonCoors Co. | $16,369 |

| 17 | Grey Goose Vodka | Bacardi Ltd. | $16,351 |

| 18 | Samuel Adams Beer | Boston Beer Co. | $14,713 |

| 19 | Jack Daniels Bourbon Whiskey | Brown-Forman Co. Inc. | $14,334 |

| 20 | Tecate Light Beer | L’Arche Green NV (Heineken) | $12,441 |

| 21 | Samuel Adams Beer Boston Lager | Boston Beer Co. | $12,355 |

| 22 | Heineken Light Beer | L’Arche Green NV (Heineken) | $12,027 |

| 23 | Anheuser-Busch Beer | AB Inbev | $12,007 |

| 24 | Victoria Beer | Constellation Brands | $11,178 |

| 25 | Angry Orchard Beverages—Alcoholic Hard Cider | Boston Beer Co. | $10,615 |

| 26 | Patron Silver Tequila | Bacardi Ltd. | $10,279 |

| 27 | Leinenkugels Summer Shandy Beer | MolsonCoors Co. | $9,643 |

| 28 | Miller High Life Beer | MolsonCoors Co. | $9,242 |

| 29 | Crown Royal Canadian Whiskey | Diageo | $9,112 |

| 30 | Hennessy Brandy—Cognac | Moet Hennessy USA Inc. (LVMH) | $8,804 |

| 31 | Captain Morgan Rum | Diageo | $8,683 |

| 32 | Johnnie Walker Scotch Whisky | Diageo | $8,652 |

| 33 | Guinness Beer | Diageo | $7,768 |

| 34 | Bud Light Beverages—Alcoholic Lime/Lime-A-Rita | AB Inbev | $7,706 |

| 35 | Coors Banquet Beer | MolsonCoors Co. | $7,647 |

| 36 | Budweiser Black Crown Beer | AnheuserBusch Inbev SA/NV | $7,571 |

| 37 | Blue Moon Belgian White Beer Ale | MolsonCoors Co. | $7,323 |

| 38 | Montejo Beer | AB Inbev | $7,318 |

| 39 | Bud Light Beer Platinum | AB Inbev | $7,221 |

| 40 | Busch Beer | AB Inbev | $7,129 |

| 41 | 1800 Silver Tequila | Proximo Spirits Inc. | $6,892 |

| 42 | Titos Vodka | Fifth Generation, Inc. | $6,883 |

| 43 | Smith & Forge Beer Hard Cider | MolsonCoors Co. | $6,826 |

| 44 | Bud Light Beer Lime | AB Inbev | $6,657 |

| 45 | Absolut Vodka | Pernod Ricard SA | $6,280 |

| 46 | Wild Turkey Bourbon Whiskey | Davide Campari-Milano SPA | $6,220 |

| 47 | Dewars Scotch Whisky | Bacardi Ltd. | $6,182 |

| 48 | Stella Artois Cidre Beverages—Alcoholic | AB Inbev | $6,057 |

| 49 | Patron Tequila | Bacardi Ltd. | $5,975 |

| 50 | Strongbow Beverages—Alcoholic Hard Cider | L’Arche Green NV (Heineken) | $5,900 |

Implications for marketing.

This amount of spending makes the leading brands ubiquitous in the U.S. landscape. It is virtually impossible to shield vulnerable populations from this level of marketing activity. Although there has been little public health research on the impact of this marketing on adults, cross-sectional studies have found significant relationships between youth exposure to alcohol advertising for specific brands and youth consumption of those brands (Ross et al., 2014a, 2014b, 2015).

Product design

Product design is an essential part of marketing, and the alcohol industry is characterized by innovation and experimentation, with hundreds of new products tested each year. One example of the implications of product design for public health is the class of products known as “super-sized alcopops.” These beverages are successors to the “alcopops,” sweet, fruit-flavored drinks that themselves drew public health criticism (Mosher, 2012) and were documented to be associated with risky drinking and related harms among youth who consumed them (Albers et al., 2015). They also share some characteristics (and parent companies and brand names) with premixed alcoholic energy drinks, another problematic product from a public health perspective (Roemer & Stockwell, 2017; Weldy, 2010).

The newest wave of super-sized alcopops contains the equivalent of roughly 5.5 standard drinks (23.5 oz. of 14% alcohol by volume). They appear to be a single serving, and young people tend to underestimate both their alcohol content and their effects (Rossheim et al., 2018). Consuming one can could easily bring young people to the legal limit within 2 hours, and consuming two cans in that same time frame could put them at risk of alcohol poisoning (Rossheim & Thombs, 2018). As a recent report on alcohol-impaired driving from the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (2018) pointed out, the alcohol content of almost all types of beverages has steadily increased in recent years, posing greater risks for driving while impaired.

Product placement and sponsorship

Product placement in entertainment and sports television and in films is an area of active alcohol marketing where spending is difficult to track. Some placements result from artistic decisions, others from payments from marketers, and it is difficult to distinguish between the two. What is clear is that the frequency of alcohol placements in films has increased in recent years, with the rise in the United States occurring primarily in films rated G or PG—that is, those considered suitable for adolescent viewing (Bergamini et al., 2013).

According to sponsorship monitor IEG, sports is the area in which alcohol companies spend most (74%) of their sponsorship dollars in the United States (IEG Sponsorship Report, 2017). AB InBev is the largest spender, laying out an estimated $360 million–$365 million in 2015 on sponsorship agreements with, among others, the National Football League, Major League Baseball, United States Soccer Federation, Stewart-Haas Racing, National Basketball Association, and Madison Square Garden (IEG Sponsorship Report, 2017). College sports, previously off limits to alcohol advertisers, have seen a significant increase in alcohol company sponsorship as well: As of mid-2017, AB InBev had marketing agreements in place at close to 60 schools, and MillerCoors had partnered with 40 (Smith & Lefton, 2017).

Stakeholder marketing and corporate social responsibility

“Stakeholder marketing” and corporate social responsibility activities are other arenas of significant alcohol marketing activity. Stakeholder marketing has been defined as “activities and processes within a system of social institutions that facilitate and maintain value through exchange relationships with multiple stakeholders” (Hult et al., 2011, p. 44). In practice, this often includes lobbying, campaign contributions, and other activities designed to influence policy makers and, as Jahiel (2008) has pointed out, maintain a policy environment conducive to increasing corporate sales and profits. Some of the activity in this arena may be tracked, through databases of political contributions maintained by nongovernmental organizations. According to opensecrets. org, annual federal lobbying expenditures by beer, wine, and distilled spirits companies approached $32 million in 2017, and there were 303 lobbyists employed by those industries—more than one for every two members of the U.S. Congress (Center for Responsive Politics, 2018). According to the National Institute on Money in Politics (2018), beer, wine, and distilled spirits interests also spent an additional $11.8 million on state-level lobbying in 2017.

Both the major alcohol companies themselves and surrogate organizations, known as “social aspects organizations” (SAO; Anderson, 2004), conduct corporate social responsibility campaigns. In the United States, the Distilled Spirits Council recently erased this distinction when it named the same person head both of the Council, an industry trade organization, and of the leading distilled spirits SAO in the United States, the Foundation for Alcohol Responsibility (formerly known as the Century Council) (Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, 2018). Globally, internal company documents described the rationale for the first major global SAO of the current era, the International Center for Alcohol Policies: “[This is] the latest initiative in managing worldwide issues, and assisting our sales and marketing group in an increasingly competitive marketplace” (Firestone, 1997, p. 6).

Recent years have seen increasing expenditure on corporate social responsibility activities from industry leader AB InBev, which launched its “Global Smart Drinking Goals” in 2015. The program consists of multi-year projects in six cities around the world (including Columbus, OH), social norms campaigns in which the company committed to invest $1 billion over 10 years, re-making its product portfolio so that by 2025 20% of its beer volume would be in no- or low-alcohol (3.5% alcohol by volume or less) products, and placing voluntary “guidance labels” to provide consumer education about beer on all its products by 2025. The company also committed to funding a “global thought leadership and program coordination made up of independent academic, public health and/or policy institutions” that would oversee the monitoring and evaluation of its Global Smart Drinking Goals project (AB InBev, 2015). However, there is no public accounting available regarding how these funds are actually being spent, and there are as yet no peer-reviewed evaluations of the project.

Peer-reviewed evaluations of other corporate social responsibility activities have found very few to be supported by scientific evidence (Babor et al., 2018; Robaina et al., 2018). They are most commonly done in wealthy countries by the largest companies. Many of the activities studied had branding or other marketing potential (Babor et al., 2018; Pantani et al., 2017), and some had the potential for doing harm to public health (Babor et al., 2018). Esser et al. (2016) reviewed 266 global initiatives taken by alcohol companies to reduce alcohol-impaired driving and found that 0.8% (n = 2) were consistent with public health evidence of effectiveness. The most recent systematic review of this literature covered 21 studies and concluded that there was no robust evidence that corporate social responsibility initiatives from the alcohol industry were effective in reducing harmful use of alcohol (Mialon & McCambridge, 2018).

Marketing in the United States and the second tier: Wholesalers

Although marketing campaigns emanate primarily from the brand owners, wholesalers play a key role in the U.S. system in bringing those brands to the retail sector. Both producers and wholesalers may collaborate with retailers on special events in bars and restaurants (on-premises), but the themes and strategies of these events will be set by or in close communication with the brand owners. Following the repeal of National Prohibition in the United States, the federal government gave states considerable leeway in designing the three-tier system within their borders. Some states permit “self-distribution,” in which brewers may own their own distribution arm; however, they are still not supposed to supply anything of value from the production to the distribution arm without due compensation. The three-tier system has become even more diverse in recent years. Most significantly, in 2011 and with substantial support from Costco, a large retailer that also covers wholesaling functions for other products, voters in the state of Washington approved a ballot initiative abolishing the state’s liquor monopoly as well as the three-tier system in that state.

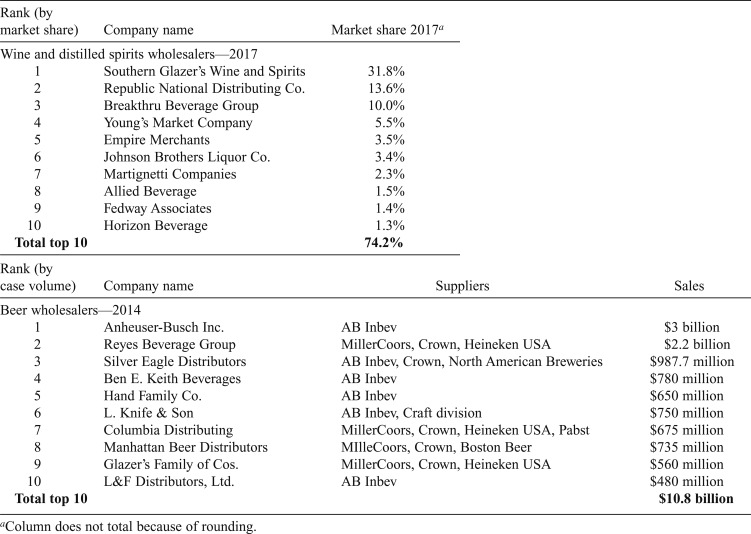

Elsewhere in the country, although the three-tier system was designed in part to maintain competition in the industry and reduce the likelihood of vertical integration, recent decades have seen unprecedented consolidation in the second tier as well. This has come in part as a result of consolidation of ownership among the producers. Because producers generally negotiate exclusive relationships with wholesalers, when producers combine this can force greater concentration among wholesalers as well. Thus, at this point wine and distilled spirits wholesaling is dominated by a small number of companies: The three largest wholesalers account for more than half of sales revenue in this tier and cover among them 47 of the 50 states. As shown in Table 4, the 10 largest wine and distilled spirits wholesalers account for nearly three-quarters of revenues from this tier (M. Shanken Communications, 2017a).

Table 4.

Leading wine, distilled spirits, and beer wholesalers, United States (M. Shanken Communications, 2017a; Katz Americas, 2016)

| Rank (by market share) | Company name | Market share 2017a |

| Wine and distilled spirits wholesalers—2017 | ||

| 1 | Southern Glazer’s Wine and Spirits | 31.8% |

| 2 | Republic National Distributing Co. | 13.6% |

| 3 | Breakthru Beverage Group | 10.0% |

| 4 | Young’s Market Company | 5.5% |

| 5 | Empire Merchants | 3.5% |

| 6 | Johnson Brothers Liquor Co. | 3.4% |

| 7 | Martignetti Companies | 2.3% |

| 8 | Allied Beverage | 1.5% |

| 9 | Fedway Associates | 1.4% |

| 10 | Horizon Beverage | 1.3% |

| Total top 10 | 74.2% | |

| Rank (by case volume) | Company name | Suppliers | Sales |

| Beer wholesalers—2014 | |||

| 1 | Anheuser-Busch Inc. | AB Inbev | $3 billion |

| 2 | Reyes Beverage Group | MillerCoors, Crown, Heineken USA | $2.2 billion |

| 3 | Silver Eagle Distributors | AB Inbev, Crown, North American Breweries | $987.7 million |

| 4 | Ben E. Keith Beverages | AB Inbev | $780 million |

| 5 | Hand Family Co. | AB Inbev | $650 million |

| 6 | L. Knife & Son | AB Inbev, Craft division | $750 million |

| 7 | Columbia Distributing | MillerCoors, Crown, Heineken USA, Pabst | $675 million |

| 8 | Manhattan Beer Distributors | MIlleCoors, Crown, Boston Beer | $735 million |

| 9 | Glazer’s Family of Cos. | MillerCoors, Crown, Heineken USA | $560 million |

| 10 | L&F Distributors, Ltd. | AB Inbev | $480 million |

| Total top 10 | $10.8 billion | ||

Column does not total because of rounding.

Although there are approximately 3,000 beer wholesaling companies in the United States, according to the National Beer Wholesalers Association (2019), the dominance of a few companies is in evidence even among the 10 companies in Table 4, where the largest has revenues six times as large as the number 10 company. In the United States, beer wholesaling has been described as essentially a duopoly (Bennett, 2016), with every local market divided between a wholesaler carrying AB InBev products and one carrying products from MolsonCoors. Exemplifying the weakening of the three-tier system, AB InBev has taken advantage of state-level variations in self-distribution restrictions to consolidate control, with an eventual goal of direct responsibility for between 10% and 12% of its beer distribution nationwide. Specifically, as of 2018 the company directly owned 28 distributors (although in keeping with the three-tier system limitations, they keep these distributors as separate entities) across 10 states. Acquisitions like these have helped to make AB InBev the largest beer distributor in the United States, with estimated sales of $3 billion in 2014. This consolidation has helped the 10 largest beer wholesalers dominate the market: As Table 4 shows, in 2014 those 10 companies sold more than $10 billion worth of beer (Katz Americas, 2014).

Implications for marketing.

These developments in the second tier have had particular implications for stakeholder marketing. When beer wholesaling in particular was more dispersed, the wholesaling tier tended to have a significant local businessperson from nearly every Congressional district. These local businesses became key “water carriers” for the interests of the industry as a whole, because they could speak as constituents and representatives of local communities. Although there have always been issues where producers and wholesalers disagreed (Mosher & Jernigan, 1989), consolidation of control of the wholesale tier by the producers has exacerbated these divisions, opening up greater possibilities for collaboration between wholesalers and public health interests. The passage in 2008 of the Sober Truth on Preventing (STOP) Underage Drinking Act (P.L. 109-422), which authorized for the first time federal funding to monitor in an ongoing way youth exposure to alcohol marketing, resulted from this collaboration. For their efforts, the beer wholesalers gained a preamble in that act that affirmed the federal government’s commitment to the three-tier system.

Marketing in the United States: The significance of “craft” brewing

Self-distribution is the hallmark of “craft” brewing. In 1915, 4 years before the start of Prohibition, there were 1,345 breweries in the United States (Stack, 2003); in 1934, 1 year after repeal, there were 933 breweries in operation, and by 1983, this number had dwindled to 43 (Swaminathan, 1998). In 2017, according to the National Beer Wholesalers Association (2019), there were 5,648 breweries reporting to the federal government in the United States. This proliferation of small breweries would seem to argue against the trend toward concentration described above. However, the decline from 933 to 43 over nearly 50 years is likely to be repeated in the coming years. The dramatic growth in consumption of craft beers—now comprising approximately 11% of the beer market—has slowed in recent years (Beer Marketer’s Insights Inc., 2017), and a crowded market place is making for in creased competition (Dubey & Mani, 2018). Signs of consolidation are already evident: The 50 largest craft brewers account for 90% of craft brewing sales (Dubey & Mani, 2018). In addition, according to industry sources, five of the fastest growing craft beer brands in 2017 were no longer small independent brewers but had been acquired by one of the major alcohol marketers (Beer Marketer’s Insights Inc., 2017).

Implications for marketing.

The rise of the craft brewing industry again has particular implications for stakeholder marketing. The image of craft brewing as predominantly a small and independent activity, an icon of American entrepreneurship and small business, persists and played a key role in one of the most significant gains for the U.S. alcohol industry in recent years, namely the roughly 18% tax cut the industry received as part of the package of tax cuts passed by the U.S. Congress in 2017 (Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017). The alcohol tax cuts amounted to approximately $4.2 billion over 2 years, or approximately 20% of previously anticipated federal alcohol tax revenues. Although the cuts were originally introduced in Congress as part of the “Craft Beverage Modernization and Tax Reform Act,” they were structured in such a way that the greatest benefits will go the largest producers (Craft Beverage Modernization and Tax Reform Act of 2017; Looney, 2018). Yet the most visible advocacy for the cuts came from the craft brewers, and the cut originated in legislation proposed by Democrat Ron Wyden of Oregon, whose state is home to a significant craft brewing industry.

Discussion

The alcohol marketing landscape is vast and complex. It is increasingly dominated by smaller numbers of companies globally at the producer level and, in the United States, at both the producer and the wholesaler levels. Oligopoly status permits significant profit taking which is then used at least in part to maintain the oligopolies, not only through mergers and acquisitions but also by erecting significant barriers to entry for new firms as a result of the high marketing spending of the market leaders. Significant spending on stakeholder marketing also likely contributes to maintaining policy environments that are permissive of alcohol marketing activities.

Public health policy responses to alcohol marketing are lacking in much of the world. According to data collected by the World Health Organization (2014), the most common means of regulating alcohol marketing is alcohol industry self-regulation. A systematic review of published studies of the effectiveness of industry self-regulation in restricting content and exposure that may put high-risk populations such as young people at risk concluded that the self-regulatory regimes were likely not meeting their goals of protecting vulnerable groups, due at least in part to conflicts of interest and procedural weaknesses that compromise the effectiveness of compliance monitoring and complaint resolution (Noel & Babor, 2017).

Beyond reliance on alcohol industry self-regulation, policy options available to national governments depend on the constitutional context. The simplest measure to implement is a complete ban. Although such bans exist in some countries, partial bans are more common. These may include bans on specific kinds of content, restrictions on the times or places that advertising and marketing materials may appear, limits on which beverages are permitted to be marketed in certain venues (most commonly applied to the strongest beverages in terms of alcohol content), medium- or channel-specific bans (e.g., banning alcohol advertising on national television or radio), location-specific bans (e.g., no alcohol marketing on public transport), and event-specific bans (e.g., no advertising or marketing of alcohol at college or university sporting events; World Health Organization, 2014).

The World Health Organization’s (2010) Global Strategy to Reduce Harmful Use of Alcohol specifically recommends establishing regulatory or co-regulatory frameworks, preferably based in statute, to regulate both content and volume of alcohol marketing. However, the most common response to a recent inquiry by the World Health Organization into what progress member states had made in implementing this aspect of the global strategy from 2010 to 2015 was no progress. More countries (47) reported progress of some kind than decreased progress (11), but 80 countries had made no headway in the first 5 years of the global strategy (Jernigan & Trangenstein, 2017). When asked about progress in implementing statutory regulations that address new marketing techniques such as social and digital media, just 19 countries reported taking any new actions since 2010 (Jernigan & Trangenstein, 2017).

The Pan American Health Organization sponsored a series of meetings and technical reports to provide guidance to member states of that region in the regulation of alcohol marketing. Specifically, its technical advisory group made the following recommendations: pass a legally binding ban on all alcohol marketing as the only means of eliminating the risk of vulnerable groups being exposed to alcohol marketing; apply the same regulations on marketing activities across all alcoholic beverages; develop regulatory capacity to implement, monitor, and enforce alcohol marketing restrictions as an essential public health function; subject cross-border marketing to the same restrictions as marketing originating domestically; consider the participation of civil society not affiliated with the alcohol industry in developing, supporting, and monitoring effective regulatory measures for alcohol marketing; and ensure that multilateral and bilateral international agreements protect the ability of states to regulate alcohol marketing (Pan American Health Organization, 2017).

Implementation of these recommendations at both national and global levels could significantly alter the global landscape of alcohol marketing. At the same time, national and regional approaches to alcohol marketing will encounter difficulty in addressing what is increasingly a global phenomenon, particularly in digital and social media. For this reason alone, it is worth exploring a “Framework Convention on Alcohol Control” that could, as its counterpart in tobacco has done, obligate countries to a minimum of activities to control and address alcohol marketing, take a clear stance regarding stakeholder marketing, and put into place global agreements regarding marketing across borders and on global digital and social platforms.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 AA021347. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Aaker D. Aaker on branding. New York, NY: Morgan James Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Advertising Age. AdAge Datacenter: World’s largest advertisers 2018. 2019. Retrieved from https://adage.com/datacenter/datapopup.php?article_id=315771. [Google Scholar]

- Advertising Age-Neustar. 200 Leading national advertisers 2018 fact pack. 2018, June 24. Retrieved from http://adage.com/d/resources/resources/whitepaper/200-leading-national-advertisers-2018-fact-pack?utm_source=AA1&utm_medium=AA&utm_campaign=AAprint. [Google Scholar]

- Albers A. B., Siegel M., Ramirez R. L., Ross C., DeJong W., Jernigan D. H. Flavored alcoholic beverage use, risky drinking behaviors, and adverse outcomes among underage drinkers: Results from the ABRAND Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105:810–815. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302349. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altria Group, Inc. Annual report. 2019. Retrieved from http://www.altria.com/AnnualReport/2018/44/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P. The beverage alcohol industry’s social aspects organizations: A public health warning. Addiction. 2004;99:1376–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00866.x. discussion 1380–1381. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anheuser-Busch InBev. Anheuser-Busch InBev launches global smart drinking goals: Consumers are encouraged to make smart drinking choices at all times. CSR Wire. 2015, December 9 Retrieved from http://www.csrwire.com/press_releases/38539-Anheuser-Busch-InBev-Launches-Global-Smart-Drinking-Goals-Consumers-are-Encouragedto-Make-Smart-Drinking-Choices-at-All-Times. [Google Scholar]

- Anheuser-Busch InBev. AB InBev annual report 2018. 2019. Retrieved from https://www.ab-inbev.com/content/dam/universaltemplate/ab-inbev/investors/reports-and-filings/annual-and-hy-reports/2019/2_3_European_financials_Final%20English_v2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Babor T., Caetano R., Casswell S., Edwards G., Giesbrecht N., Graham K., Rossow I. Alcohol: No ordinary commodity: Research and public policy. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Babor T. F., Robaina K., Brown K., Noel J., Cremonte M., Pantani D., Pinsky I. Is the alcohol industry doing well by ‘doing good’? Findings from a content analysis of the alcohol industry’s actions to reduce harmful drinking. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e024325. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024325. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer Marketer’s Insights. 2017 Beer industry update. 2017 Retrieved from https://www.beerinsights.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=35&Itemid=14.

- Bennett S. Wholesale wars: The battle for the future of beer distribution. BeerAdvocate. 2016 Retrieved from https://www.beeradvocate.com/articles/13526/wholesale-wars-the-battle-for-the-futureof-beer-distribution/ [Google Scholar]

- Bergamini E., Demidenko E., Sargent J. D. Trends in tobacco and alcohol brand placements in popular US movies, 1996 through 2009. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167:634–639. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.393. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh J., Clairmonte F. Alcoholic beverages: Dimensions of corporate power. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Responsive Politics. Beer, wine & liquor. 2018. Retrieved from http://www.opensecrets.org/industries/indus.php?cycle=2018&ind=N02. [Google Scholar]

- Craft Beverage Modernization and Tax Reform Act of. S. 236, 115th Cong. (2017) 2017 [Google Scholar]

- The Coca-Cola Company. United States Securities and Exchange Commission, Form 10-K, The Coca-Cola Company. 2019. Retrieved from https://www.coca-colacompany.com/content/dam/journey/us/en/private/fileassets/pdf/2019/annual-shareholders-meeting/2018-Annual-Reporton-Form-10-K.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Connor J. Alcohol consumption as a cause of cancer. Addiction. 2017;112:222–228. doi: 10.1111/add.13477. doi:10.1111/add.13477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran A. Margins by sector (US) 2019. Retrieved from http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/∼adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/margin.html. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruijn A. Alcohol marketing practices in Africa: Findings from The Gambia, Ghana, Nigeria and Uganda. 2011. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/109914/9789290231844.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Distilled Spirits Council of the United States. Industry veteran Chris Swonger named CEO of Distilled Spirits Council and Responsibility.org. 2018, October 17. Retrieved from https://www.distilledspirits.org/news/industry-veteran-chris-swonger-named-ceo-of-distilled-spirits-counciland-responsibility-org/ [Google Scholar]

- Dubey A., Mani R. Can craft beer continue to tap into growth? Strategy & Business. 2018, January 24 Retrieved from https://www.strategy-business.com/article/Can-Craft-Beer-Continue-toTap-into-Growth?gko=3ef47. [Google Scholar]

- Esser M. B., Bao J., Jernigan D. H., Hyder A. A. Evaluation of the evidence base for the alcohol industry’s actions to reduce drink driving globally. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106:707–713. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.303026. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.303026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser M. B., Hedden S. L., Kanny D., Brewer R. D., Gfroerer J. C., Naimi T. S. Prevalence of alcohol dependence among US adult drinkers, 2009-2011. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2014;11:E206. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser M. B., Jernigan D. H. Multinational alcohol market development and public health: Diageo in India. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105:2220–2227. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302831. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euromonitor International. Alcoholic Beverages—World. 2018. Retrieved from Passport, June 14, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Trade Commission. Self-regulation in the alcohol industry: Report of the Federal Trade Commission. 2014. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/self-regulation-alcohol-industryreport-federal-trade-commission/140320alcoholreport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Firestone M. Philip Morris CEO issues book. “Beer operations” chapter. 1997 Retrieved from https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=jjwn0010.

- Hult G. T. M., Mena J. A., Ferrell O. C., Ferrell L. Stakeholder marketing: A definition and conceptual framework. AMS Review. 2011;1:44–65. [Google Scholar]

- IEG Sponsorship Report. Where beer companies spend money. 2017, March 20. Retrieved from http://www.sponsorship.com/iegsr/2017/03/20/Where-Beer-Companies-Spend-Money.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) GBD Compare Data Visualization. 2016. Retrieved from http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare. [Google Scholar]

- Jahiel R. I. Corporation-induced diseases, upstream epidemiologic surveillance, and urban health. Journal of Urban Health. 2008;85:517–531. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9283-x. doi:10.1007/s11524-008-9283-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S. C. Global competitiveness in the beer industry: A case study. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D., Trangenstein P. Global developments in alcohol policies: Progress in implementation of the WHO global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol since 2010. 2017. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/fadab/msb_adab_gas_progress_report.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H. Applying commodity chain analysis to changing modes of alcohol supply in a developing country. Addiction. 2000a;95(Supplement 4):S465–S475. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.95.12s4.2.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H. Implications of structural changes in the global alcohol supply. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2000b;27:163–187. doi:10.1177/009145090002700107. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H. Cultural vessels: Alcohol and the evolution of the marketing-driven commodity chain. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2001;62:349–350. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H. The global alcohol industry: An overview. Addiction. 2009;104(Supplement 1):6–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02430.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H. Global alcohol producers, science, and policy: The case of the International Center for Alcohol Policies. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:80–89. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300269. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H., Babor T. F. The concentration of the global alcohol industry and its penetration in the African region. Addiction. 2015;110:551–560. doi: 10.1111/add.12468. doi:10.1111/add.12468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H., Obot I. Thirsting for the African market. African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies. 2006;5:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Katz Americas. LIST: Top 30 US Beer Distributors. 2014. Retrieved from http://www.katzamericas.com/blog/beer/list-top-30-us-beer-distributors/ [Google Scholar]

- Looney A. Who benefits from the “craft beverage” tax cuts? Mostly foreign and industrial producers. 2018, January 3. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/who-benefits-from-the-craft-beverage-taxcuts-mostly-foreign-and-industrial-producers/ [Google Scholar]

- Mialon M., McCambridge J. Alcohol industry corporate social responsibility initiatives and harmful drinking: A systematic review. European Journal of Public Health. 2018;28:664–673. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky065. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher J. F. Joe Camel in a bottle: Diageo, the Smirnoff brand, and the transformation of the youth alcohol market. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:56–63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300387. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher J. F., Jernigan D. H. New directions in alcohol policy. Annual Review of Public Health. 1989;10:245–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.10.050189.001333. doi:10.1146/annurev.pu.10.050189.001333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- M. Shanken Communications. The global drinks market: Impact databank review and forecast. New York, NY: Author; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- M. Shanken Communications. The U.S. Spirits Market: Shanken’s Impact Databank Review and Forecast. 2017 edition. New York, NY: Author; 2017a. [Google Scholar]

- M. Shanken Communications. The U.S. Wine Market: Shanken’s Impact Databank Review and Forecast. 2017 edition. New York, NY: Author; 2017b. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. Getting to zero alcohol-impaired driving fatalities: A comprehensive approach to a persistent problem. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Beer Wholesalers Association. Industry data: Industry fast facts. 2019. Retrieved from https://www.nbwa.org/resources/industry-fast-facts. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Money in Politics. State-level lobbyist spending by beer, wine & liquor spenders in 2017. 2018. Retrieved from https://www.followthemoney.org/show-me?dt=3&lby-f-fc=2&lby-f-cci=57&lby-y=2017#[{1|gro=lby-y. [Google Scholar]

- Noel J. K., Babor T. F. Does industry self-regulation protect young persons from exposure to alcohol marketing? A review of compliance and complaint studies. Addiction. 2017;112(Supplement 1):51–56. doi: 10.1111/add.13432. doi:10.1111/add.13432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. PAHO meeting on alcohol marketing regulation: Final report. 2016. Retrieved from http://iris.paho.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/28424/PAHONMH16001_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y&ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Technical note: Background on alcohol marketing regulation and monitoring for the protection of public health. 2017. Retrieved from http://iris.paho.org/xmlui/handle/123456789/33972. [Google Scholar]

- Pantani D., Peltzer R., Cremonte M., Robaina K., Babor T., Pinsky I. The marketing potential of corporate social responsibility activities: The case of the alcohol industry in Latin America and the Caribbean. Addiction. 2017;112(Supplement 1):74–80. doi: 10.1111/add.13616. doi:10.1111/add.13616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robaina K., Brown K., Babor T. F., Noel J. Alcohol industry actions to reduce harmful drinking in Europe: Public health or public relations? Public Health Panorama. 2018;4:341–349. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer A., Stockwell T. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks and risk of injury: A systematic review. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017;78:175–183. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.175. doi:10.15288/jsad.2017.78.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. S., Maple E., Siegel M., DeJong W., Naimi T. S., Ostroff J., Jernigan D. H. The relationship between brand-specific alcohol advertising on television and brand-specific consumption among underage youth. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014a;38:2234–2242. doi: 10.1111/acer.12488. doi:10.1111/acer.12488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. S., Maple E., Siegel M., DeJong W., Naimi T. S., Padon A. A., Jernigan D. H. The relationship between population-level exposure to alcohol advertising on television and brand-specific consumption among underage youth in the US. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2015;50:358–364. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv016. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agv016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. S., Ostroff J., Siegel M. B., DeJong W., Naimi T. S., Jernigan D. H. Youth alcohol brand consumption and exposure to brand advertising in magazines. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014b;75:615–622. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.615. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossheim M. E., Thombs D. L. Estimated blood alcohol concentrations achieved by consuming supersized alcopops. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44:317–320. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1334210. doi:10.1080/00952 990.2017.1334210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossheim M. E., Thombs D. L., Krall J. R., Jernigan D. H. College students’ underestimation of blood alcohol concentration from hypothetical consumption of supersized alcopops: Results from a cluster-randomized classroom study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2018;42:1271–1280. doi: 10.1111/acer.13764. doi:10.1111/acer.13764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks J. J., Gonzales K. R., Bouchery E. E., Tomedi L. E., Brewer R. D. 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;49:e73–e79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. C., Cukier S., Jernigan D. H. Regulating alcohol advertising: Content analysis of the adequacy of federal and self-regulation of magazine advertisements, 2008-2010. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:1901–1911. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301483. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M., Lefton T. Colleges chug beer dollars. Sports Business Journal. 2017July 31 Retrieved from https://www.sportsbusinessdaily.com/Journal/Issues/2017/07/31/Colleges/Beer.aspx.

- Sober Truth on Preventing Underage Drinking Act of. 2008. Pub. L. No. 109-422, 120 Stat. 2890 (2008)

- Stack M. H. A concise history of America’s brewing industry. 2003. Retrieved from https://eh.net/encyclopedia/a-concise-history-of-americas-brewing-industry/ [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan A. Entry into new market segments in mature industries: Endogenous and exogenous segmentation in the U.S. brewing industry. Strategic Management Journal. 1998;19:389–404. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199804)19:4<389::AID-SMJ973>3.0.CO;2-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of. 2017. Pub. L. 115-97, 131 Stat. 2054 (2017)

- Washington Liquor State Licensing. Washington Liquor State Licensing, Initiative 1183 (2011) 2011. Retrieved from https://ballotpedia.org/Washington_Liquor_State_Licensing,_Initiative_1183_(2011) [Google Scholar]

- Weldy D. L. Risks of alcoholic energy drinks for youth. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2010;23:555–558. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.04.090261. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2010.04.090261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman D. Beer exports by country. 2018a. Retrieved from http://www.worldstopexports.com/beer-exports-by-country/ [Google Scholar]

- Workman D. Major export companies: Alcoholic beverages. 2018b. Retrieved from http://www.worldstopexports.com/major-export-companies-alcoholic-beverages/ [Google Scholar]

- Workman D. Wine exports by country. 2018c. Retrieved from http://www.worldstopexports.com/wine-exports-country/ [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Framework convention on tobacco control. 2005. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/tobacco/framework/WHO_FCTC_english.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/alcstratenglishfinal.pdf?ua=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. 2014. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/msb_gsr_2014_1.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Technical Annex (Version dated 12 April 2017) Updated Appendix 3 of the WHO Global NCD Action Plan 2013-2020. 2017. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/ncds/governance/technical_annex.pdf. [Google Scholar]