Abstract

Objective:

Evidence increasingly suggests that alcohol marketing plays a significant role in facilitating underage drinking. This article presents a review of empirical studies and relevant theoretical models proposing plausible psychological mechanisms or processes responsible for associations between alcohol-related marketing and youth drinking.

Method:

We review key psychological processes pertaining to cognitive mechanisms and social cognitive models that operate at the individual or intrapersonal level (attitude formation, expectancies) and the social or interpersonal level (personal identity, social identity, social norms). We use dominant psychological and media theories to support our statements of putative causal inferences, including the Message Interpretation Processing Model, Prototype Willingness Model, and Reinforcing Spirals Model.

Results:

Based on the evidence, we propose an integrated conceptual model that depicts relevant psychological processes as they work together in a complex chain of influence, and we highlight those constructs that have received the greatest support in the literature.

Conclusions:

The evidence to date suggests that perceptions of others’ behaviors and attitudes in relation to alcohol (social norms) may be a more potent driver of youth drinking than evaluations of drinking outcomes (expectancies). Considerably more research—especially experimental research—is needed to understand the extent to which theoretically relevant psychological processes have unique effects on adolescent and young adult drinking behavior, with the ultimate goal of identifying modifiable intervention targets to produce reductions in the initiation and maintenance of underage alcohol use.

Consumption of alcohol by underage individuals is a serious public health concern. Underage drinkers consume large quantities per drinking episode (Schulenberg et al., 2017) and experience high rates of alcohol-related negative consequences (e.g., car accidents; unintentional injuries; Hingson et al., 2000; McGue et al., 2001). Moreover, alcohol consumption has acute and prolonged neurobiological effects specific to the adolescent brain (Clark et al., 2008; Squeglia et al., 2009). The economic impact of underage drinking is considerable, with estimates placing the cost as high as $62 billion annually in the United States alone (Miller et al., 2006).

Researchers and policy-makers have long suspected that alcohol marketing plays a role in facilitating underage drinking. Despite alcohol marketing and advertising ostensibly being aimed exclusively at adults (International Alliance for Responsible Drinking, 2011; Jernigan, 2013), youth are, nevertheless, exposed at very high rates (Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth, 2012; International Alliance for Responsible Drinking, 2014). Most television advertising regulation related to alcohol is voluntary and frequently violated (Noel et al., 2017a; Russell et al., 2016); this is especially true for ads with thematic content that is appealing to youth (e.g., sociability, romance, individuality; Noel et al., 2017b). Recent years have witnessed an explosion of new (digital) media marketing. Although youth-oriented television alcohol advertising has declined over time (White et al., 2017), alcohol content on digital media has increased (Jernigan et al., 2017b; Winpenny et al., 2014). The alcohol industry is aware of the effectiveness of both digital and traditional marketing strategies and regularly integrates the two. For example, in 2012, “liking” the Corona Lite Facebook page provided access to a smartphone app, allowing the viewer to upload a photo to appear on a billboard in Times Square (Fitzsimmons, 2010). Advertised content on digital media marketing platforms is poorly regulated (Barry et al., 2015; Erevik et al., 2018; Jernigan & Rushman, 2014) and age restrictions are easily circumvented (Madden et al., 2013). Commensurate with their heavy social media use (Critchlow et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2012; Pew Research Center, 2018) and the ubiquity of alcohol references in digital media, it is unsurprising that youth report high exposure to new media alcohol content.

There is reason to believe that marketing and advertising are particularly influential in encouraging the drinking-related attitudes of adolescents and young or “emerging” adults (i.e., ages 18–25 years). Their attitudes and preferences are less firmly entrenched, making youth more susceptible to influence by external factors (Glasman & Albarracín, 2006). Youth also are highly susceptible to the socializing influences of peers and prevailing generational norms (Krosnick & Alwin, 1989). They are preoccupied with personal image and identity (Giles & Maltby, 2004; Kroger, 2000) and respond favorably to ads appealing to lifestyle, popular culture, and self-concept (McClure et al., 2013). Moreover, the influences encountered during this period are believed to have a lifelong impact, producing core attitudinal orientations that are unlikely to change with age (Etchegaray et al., 2019; Osborne et al., 2011).

Prior literature, including systematic reviews, as well as the other articles in this special issue offer considerable evidence of a robust association between alcohol marketing and exposure to alcohol content in the media and alcohol use by adolescents and young adults (Anderson et al., 2009; Chung et al., 2010; Grube & Wallack, 1994; Koordeman et al., 2012; McClure et al., 2016; Ross et al., 2014; Smith & Foxcroft, 2009). Until recently studies focused on traditional forms of marketing such as film, television, print, radio, and promotional activities, but there is a recent shift to alcohol-related digital and social media content, with support for associations between alcohol references on social media sites and subsequent alcohol use and problems (Alhabash et al., 2018; Barry et al., 2016; Boyle et al., 2016; Gordon et al., 2010; Moreno & Whitehill, 2014). A recent meta-analysis found moderate effect sizes between alcohol-related social media viewing and engagement (e.g., posting, liking, commenting) and alcohol use and problems, with the association between drinking and marketing stronger via digital and social media than via traditional media (Curtis et al., 2018).

Much of the support for an association between alcohol-related marketing/media and youth drinking is based on rigorous prospective cohort studies that adjust for potential interpersonal-level (parent, peer influence) and individual-level (sociodemographics, sensation seeking) confounders. These studies lend credence to the argument that marketing exposure is a causal factor associated with increases in drinking behavior. Firm conclusions about causality require rigorous, tightly controlled experiments; however, these often are impracticable when studying underage drinking. The application of strict epidemiological criteria—such as the Bradford Hill criteria (Hill, 1965) of strength of association, consistency, temporality, and plausibility—to observational behavioral studies can assist in understanding the strength of the evidence base for alcohol marketing as a causal agent.

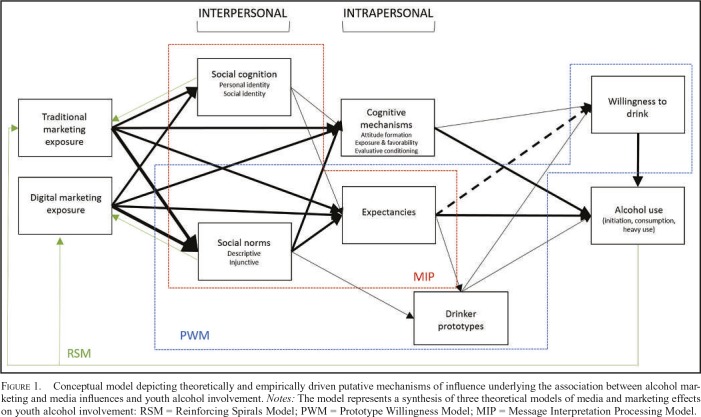

This article presents a review of empirical studies and relevant theoretical models proposing plausible psychological mechanisms or processes responsible for proposed causal associations between alcohol-related marketing and media and youth drinking. The purpose of this article is not to make the case for a causal connection between marketing and media exposure and youth drinking per se but, rather, to consider the extent to which a key Bradford Hill criterion—psychological plausibility—is supported by the evidence and proposed theoretical mechanisms. Figure 1 provides a conceptual model depicting a number of psychological mechanisms posited in previous research to facilitate underage alcohol use as a result of alcohol advertising and media exposure. The model represents a synthesis of three theoretical models of media and marketing effects on alcohol involvement, some of which share proposed mechanisms of influence, as well as additional factors not specific to any of these models. These theoretical models—which include the Message Interpretation Processing Model (Austin, 2007), Prototype Willingness Model (Gerrard et al., 2008), and Reinforcing Spirals Model (Slater, 2007)—posit directionality among component processes, in particular the association from interpersonal processes (e.g., social identity, social norms) to intrapersonal processes (e.g., expectancies) to behavioral willingness and ultimately drinking behavior, and our synthesized model draws from these conceptualizations.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model depicting theoretically and empirically driven putative mechanisms of influence underlying the association between alcohol marketing and media influences and youth alcohol involvement. Notes: The model represents a synthesis of three theoretical models of media and marketing effects on youth alcohol involvement: RSM = Reinforcing Spirals Model; PWM = Prototype Willingness Model; MIP = Message Interpretation Processing Model.

To our knowledge, this article presents the first attempt to combine models of alcohol marketing and media effects into a coherent—if complex—unifying framework. Of course, the model depicted in Figure 1 is merely conceptual and is not considered a formal theory. Its primary purpose is to illustrate the complex chain of influence exerted by various factors that current theories have proposed to explain the effects of alcohol advertising on consumption of alcohol by youth.

We initially review the literature for each of the psychological processes that have received some degree of support from the literature—in some cases, demonstrating prospective associations that are independent of sociodemographics and potentially confounding variables such as peer alcohol use, impulsivity, and sensation seeking. We first describe interpersonal mechanisms, which are most proximal to drinking behavior, followed by a discussion of more distal intrapersonal mechanisms. We then explain how these mechanisms fit together within the framework of several well-supported theoretical models of health risk behavior, and last, we revisit our proposed conceptual model, which serves to integrate content across all mechanisms and theories we considered.

Intrapersonal Mechanisms

Attitude formation

Attitudes are evaluations concerning an object or person (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993), represented as associations in memory between a given object and a summary evaluation of it (Fazio, 1995; Jones et al., 2010; Stacy, 1997). Attitudes theoretically determine behavioral dispositions toward objects, such that objects associated with favorable attitudes will be approached or sought after, whereas objects associated with unfavorable attitudes will be avoided. Arguably, the primary goal of advertising is to encourage consumption (i.e., purchases) by promoting favorable attitudes toward advertised products.

Exposure and favorability.

At the most basic level, the marketing of any product is about exposure—placing the brand in view of consumers. This “exposure approach” is grounded in the psychological construct of familiarity and the notion that increased familiarity is associated with more favorable evaluations (Zajonc, 1968; Zajonc & Markus, 1982). Considerable evidence supports the idea that more frequent advertising is associated with increased brand familiarity and more favorable evaluations (D’Souza & Rao, 1995; Ha et al., 2011; Rindfleisch & Inman, 1998), which, in theory, translates into stronger sales. The effectiveness of this approach is suggested by the finding that young peoples’ favorite alcohol brands are those with the largest advertising expenditures (Tanski et al., 2011).

From a public health perspective, effects of exposure to alcohol advertising in the underage segment are important mainly for their potential to affect primary demand, or preferences, for alcoholic beverages as a product class (Saffer, 1995). For this to occur on a large scale, evaluative associations must generalize beyond a particular brand. Considerable research suggests that effects of exposure on increased liking can generalize from the exposed stimulus to others that are conceptually related (Gordon & Holyoak, 1983; Manza et al., 1998; Monahan et al., 2000; Rhodes et al., 2001). For example, in one study, exposure to strangers’ faces increased liking for averaged composites of those faces, even though the composites themselves had not been seen previously (Rhodes et al., 2001). By extension, frequent exposure to advertisements for various beer brands is likely to produce more favorable evaluations of beer as a general product class, beyond any specific brand.

Moreover, the relationship between familiarity and favorability appears to depend on additional factors. For example, consumers are more likely to choose options they believe others will approve of, because such choices are associated with easy rationales or justifications (Bettman et al., 1991). Rindfleisch and Inman (1998) tested the hypothesis that consumers prefer better-known brands because purchasing those brands reflects compliance with social norms (i.e., social desirability). Participants led to believe that the most familiar brand was also the one most people prefer were more likely to choose that brand over a less familiar brand. In contrast, participants simply exposed to a particular brand more often were no more likely to prefer it over a less-frequently presented brand.

Misattribution of attitudes.

The association between familiarity and liking also can be influenced by the mindset evoked by a given exposure. According to the Situated Inference Model of priming (Loersch & Payne, 2011, 2014, 2016), incidental exposure to external stimuli (i.e., priming) makes certain thoughts and feelings more accessible in memory, and people often fail to recognize the (external) source of those thoughts and feelings. That is, people mistakenly attribute mental content made accessible by external stimuli to their own internal thought processes. This can explain why most people believe that they are not influenced by advertising—people tend to attribute their preferences to their own, internally generated, reasoning rather than to persuasive external appeals (Dempsey & Mitchell, 2010). When this happens, people tend to rely on those thoughts and feelings to answer implicit questions aroused by product exposure, such as what one wants (i.e., a purchase intention) or even what kind of person one should be.

Alcohol advertisements routinely suggest these kinds of implicit questions to underage consumers. For example, Bud Light recently used the tag line, “Up for Whatever,” in its marketing and advertising. When combined with actors portraying a lifestyle of leisure and spontaneity, this campaign arguably arouses questions in consumers concerning their own identities (i.e., “Am I the kind of person who is ‘up for whatever’?”). When subsequently presented with an opportunity to choose a beverage, a young person is likely to select Bud Light to the extent that it has been associated with an identity she finds appealing (i.e., being spontaneous). Given that Bud Light is also among the most heavily promoted brands in the world (Tadena, 2014), this appeal to young people’s inherent motivation to define themselves (Kroger, 2000) may serve as a powerful persuasive appeal. In such a scenario, the consumer is likely to select an advertised product to the extent that it provides an answer to an implicit question that she is not aware deliberately arose from an external source.

Evaluative conditioning.

A close cousin to the exposure approach is one in which a product is presented alongside some object, event, or person for which consumers have an existing positive attitude. This practice is used in numerous ways, ranging from simple co-occurrence (e.g., ensuring that a new product is placed next to one that consumers already favor) to corporate sponsorship of events (e.g., concerts) to celebrity endorsements. Psychologically, this practice takes advantage of basic evaluative conditioning—the phenomenon whereby favorability of one object is determined by its apparent affiliation with another object (De Houwer et al., 2001; Jones et al., 2010).

Alcohol advertisers routinely leverage evaluative conditioning to encourage positive evaluations of their products. For example, when actors in alcohol ads express obvious positive emotion, the audience need not infer that the people in the ads are happy because of the alcohol they are consuming; the mere co-occurrence of happy people with alcohol is sufficient for evaluative conditioning to occur. Experimental research has demonstrated how evaluative conditioning can work to shape drinking-related attitudes (Baeyens et al., 2001; Houben et al., 2010) and that exposure to alcohol ads can automatically activate evaluations related to alcohol, which then mediate the association between ad exposure and willingness to drink (Goodall & Slater, 2010).

Expectancies

The extent to which individuals expect alcohol to produce effects they value (e.g., relieving stress, making social gatherings more fun) is strongly associated with their alcohol involvement (Goldman et al., 1991, 1999; Janssen et al., 2018b; Schell et al., 2005). Even those with no personal drinking experience hold alcohol-related expectancies that are transmitted through indirect learning experiences, with media exposure being one example (Smit et al., 2018). Media portrayals present drinking in a favorable light, associating alcohol use with relaxation and with social, sexual, and financial success; the hazards of drinking are rarely shown (Stern & Morr, 2013). Television advertising features content appealing to youth, with ads portraying camaraderie, romantic connection, and social positioning (Padon et al., 2018). Moreover, some alcohol brands are marketed as youth-oriented, portrayed with positive images and emotions specifically designed to appeal to young audiences (Borzekowski et al., 2015). By fostering more favorable beliefs about drinking and reducing its perceived harms, marketing-and media-related alcohol content can facilitate alcohol use (Wills et al., 2009).

However, the literature supporting alcohol expectancies as a channel for exposure to influence drinking has produced mixed findings. There is cross-sectional (De Graaf, 2013; Elmore et al., 2017; Ho et al., 2014; Morgenstern et al., 2011) and longitudinal (Collins et al., 2017; Dal Cin et al., 2009; Osberg et al., 2012) evidence supporting an effect of advertising and media alcohol portrayals on outcome expectancies, even among alcohol-naïve youth (Morgenstern et al., 2011). Other research, however, has failed to detect associations of alcohol marketing exposure with null findings for both positive (De Graaf, 2013; Janssen et al., 2018a; Martino et al., 2006; Wills et al., 2009) and negative alcohol expectancies (Janssen et al., 2018a; Kulick & Rosenberg, 2001; Osberg et al., 2012). Findings are mixed even within the same study; for example, adolescents reported more negative expectancies and fewer positive expectancies about the effects of alcohol after viewing television programs portraying alcohol with negative consequences, but the same was not true for positively portrayed content (De Graaf, 2013).

Findings of studies examining proximal change in expectancies using laboratory paradigms (Stautz et al., 2016) or ecological momentary assessment designs also are mixed. Among college students, exposure to positive movie portrayals of the effects of distilled spirits (compared with exposure to a neutral movie) yielded more positive but also more negative alcohol expectancies (Kulick & Rosenberg, 2001). In contrast, adolescents’ positive expectancies were unchanged after viewing a beer commercial compared with a neutral (soft-drink) commercial or a beer commercial combined with anti-drinking messages (Lipsitz et al., 1993). In vivo exposure to alcohol advertising in middle school students failed to produce a relative change in either positive or negative expectancies at the time of ad exposure (Collins et al., 2016), although a reduction in negative expectancies was evident when the adolescent reported liking the ad (Collins et al., 2017). Together, these ecological momentary assessment and experimental protocol findings raise doubts that acute ad exposure produces more favorable alcohol expectancies (Martino et al., 2016), although repeated exposure may strengthen pro-alcohol beliefs (Collins et al., 2017).

Formal tests of mediation of exposure effects by intrapersonal mechanisms are rare, have been limited to tests of alcohol expectancies, and demonstrate mixed findings. Studies with adolescents (Dal Cin et al., 2009) and college freshmen (Osberg et al., 2012) have shown that exposure to alcohol content in films influences consumption through positive and negative expectancies, with negative expectancies also serving as a mediator for alcohol-related consequences (Osberg et al., 2012). However, this effect was not replicated when considering drinking initiation as an outcome (Janssen et al., 2018a). One study found that positive expectancies mediated the association between advertising exposure and adolescents’ intention to drink (Fleming et al., 2004). One other study detected significant mediation for intention to drink (for underage youth) and drinking (for of-age youth) by positive expectancies but only when attention to alcohol advertising was considered (Jang & Frederick, 2012). Finally, a study examined associations between exposure and adolescent heavy drinking across the full spectrum of marketing involvement (having a favorite alcohol ad, movie alcohol brand exposure, ownership of alcohol-branded merchandise), and failed to detect mediation by expectancies (McClure et al., 2013). Taken together, although a vast literature indicates a robust association between expectancies about alcohol’s effects and drinking behavior, there is only weak support for expectancies as a plausible mechanism for the influence of alcohol marketing/media and youth drinking.

In sum, a number of intrapersonal psychological processes plausibly link youth drinking to alcohol advertising and marketing exposure. A major goal of advertising is to get products into the minds of consumers, in the hope that doing so will translate into product sales. The most straightforward mechanism for translating advertisements and marketing into sales is simple exposure—the more consumers are exposed to a brand or product class, the more likely they are to like it (D’Souza & Rao, 1995; Rindfleisch & Inman, 1998) and to choose it in situations in which implicit questions arise (e.g., What do I want?) (Loersch & Payne, 2011). An additional strategy for influencing preferences is to affiliate products with objects or constructs people already value. Although some research shows that positive responses to alcohol ads can produce positive automatically activated attitudes toward drinking (Goodall & Slater, 2010), little work has demonstrated a causal link between evaluative conditioning from advertisements and actual consumption of alcohol (but see Houben et al., 2010). Last, numerous studies have tested the idea that exposure to alcohol in media produces positive alcohol outcome expectancies, but findings to date have been equivocal. At present there is little reason to believe that alcohol advertising and marketing play a significant role in young people’s alcohol expectancies.

Interpersonal Mechanisms

Adolescence is characterized by a preoccupation with personal and social identity (Giles & Maltby, 2004; Kroger, 2000), making social-cognitive mechanisms highly relevant to understanding marketing effects among young people. Adolescents and young adults are very concerned with determining who they are and how they fit in with their peers (Finkenauer et al., 2002). Marketers and advertisers craft persuasive appeals likely designed to engage the psychological processes underlying these natural tendencies.

Personal identity

The self-concept can be considered the association in memory of “the self” with one or more attributes (Greenwald et al., 2002), including personality traits, values, and preferences. The incorporation of attitudes into the self concept can be understood through the construct of cognitive consistency. Psychological theory boasts a long tradition of cognitive consistency models (Abelson et al., 1968; Festinger, 1957; Heider, 1958; Osgood & Tannenbaum, 1955), which generally posit that people are motivated to ensure that their behaviors are consistent with their beliefs.

A central goal of alcohol marketing approaches is the cultivation of a so-called “drinker identity,” in which alcohol use is incorporated into the self-concept (Casswell, 2004; McCreanor et al., 2005). Research suggests that incorporation of a drinker identity plays a role in explaining effects of alcohol marketing exposure on youth drinking. In their study of marketing exposure and drinking among more than 1,700 U.S. adolescents and emerging adults, McClure and colleagues (2013) found that strength of drinker identity mediated the association between alcohol marketing exposure and heavy drinking, even when accounting for the influence of outcome expectancies and social norms.

The idea that formation of a drinker identity can causally explain the effects of alcohol marketing on youth drinking gains plausibility when examined through the lens of Self Categorization Theory (Turner & Reynolds, 2010, 2011). Self-Categorization Theory describes the processes by which people form social categories and their memberships in them; it can be used to understand two common marketing and advertising practices. First, marketers strive to instill identification with a behavior or lifestyle, such as that associated with drinking. This form of identity is not specific to any brand but, rather, reflects use of a type of commodity. Within Self-Categorization Theory, this level of self-categorization is considered part of personal identity, in which the individual identifies aspects of herself that align her with some individuals (e.g., people who drink) and distinguish her from others (e.g., people who don’t) (Turner et al., 2006).

Social identity

At the more specific level of brand identification, Self-Categorization Theory also can be used to understand the allure of so-called brand communities, comprising consumers who share a preference for a given brand (McAlexander et al., 2002). One of the best-known and well-orchestrated brand communities is the Harley Owners Group (HOG), established in 1983 by the Harley-Davidson motorcycle company. The HOG is a key aspect of Harley-Davidson’s marketing efforts, promoting not only the company’s products but also a lifestyle associated with motorcycling. Sales of HOG-branded merchandise and organization of events for members help to ensure a strong feeling of group cohesion among HOG members.

The practice of cultivating brand communities such as the HOG takes advantage of a broader level of self-categorization associated with social identity. The need to belong to and feel valued by social groups is among the most powerful motivating forces in human life (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). According to Social Identity Theory (Tajfel &Turner, 1979), people naturally view themselves and others as members of social categories. Moreover, social categories are inherently evaluative in nature, in that people strive to view the groups to which they belong (i.e., in-groups) positively, relative to other groups (i.e., out-groups). Brand communities are social categories united by loyalty to particular brands; but group membership also implies similarity among members in numerous other domains, such as lifestyle choices and personality, providing a deeper level of meaning to group membership.

Some beer advertising campaigns have taken advantage of social identity principles by affiliating brands with a particular lifestyle or social group. For example, ads for Michelob Ultra attempt to align the brand with fitness and athletics— the brand’s current slogan is, “Brewed for Those who Go the Extra Mile”—and its ads routinely feature people drinking Michelob Ultra after exercising or competing in sports. This campaign appears geared toward resolving a kind of dissonance that might be experienced by those who not only value fitness but also want to drink beer and, in so doing, allows those individuals to maintain both a drinker identity and a fitness identity.

Clearly, fostering brand communities is in companies’ best interest for building and maintaining a loyal customer base (Algesheimer et al., 2005). It is in alcoholic beverage manufacturers’ interest to stimulate brand community membership among adolescents (e.g., through ownership of branded merchandise), because doing so ensures that preferences are in place when these consumers become of age to purchase alcohol. One way in which alcoholic beverage manufacturers have a presence in the lives of underage consumers is by affiliating themselves with U.S. universities, where the majority of students are 18–20 years old. Historically, manufacturers have used a number of indirect means to associate themselves with universities, including advertising during college sports broadcasts (Jernigan & Ross, 2010) and sponsoring campus facilities (e.g., Anheuser-Busch Natural Resources Building, University of Missouri; Coors Events Center, University of Colorado).

Recently, beer companies have taken a more direct approach, explicitly affiliating their brands with universities through licensing agreements that permit corporations to use trademarked university symbols and logos in marketing campaigns. Bartholow, Loersch, and their colleagues have investigated the consequences of this practice for the perceptions and attitudes of underage student drinkers. In their initial studies, Loersch and Bartholow (2011) randomly assigned underage university students to conditions in which they viewed either typical cans of Bud Light beer, or so-called Bud Light “fan cans,” which display the colors of the students’ university (Peltz, 2009). Across three experiments, Loersch and Bartholow found that, compared with participants exposed to typical Bud Light cans, participants exposed to fan cans were more likely to associate beer drinking with safety and to believe that drinking and partying were less risky. This result is consistent with research indicating that cues signaling in-group affiliation elicit feelings of trust and safety (Brewer, 2008; Voci, 2006). Given that students tend to identify strongly with their universities (Burke & Reitzes, 1981; Reitzes, 1981), this apparent transfer of safety-related feelings to a product that arguably poses considerable risk in this population (Perkins, 2002), although unsettling, is not surprising.

More recently, Bartholow and colleagues (2018) tested the extent to which directly pairing beer logos with trademarked university symbols enhances the incentive salience of the brands for underage students. As predicted on the basis of both communication theory (Du Plessis, 2005) and Incentive Sensitization Theory (Robinson & Berridge, 1993, 2000), beer logos paired with symbols representing students’ universities (i.e., their in-group) elicited larger brain responses than beer logos paired with other universities’ symbols. This phenomenon was demonstrated using both artificially contrived pairings of beer logos with university symbols, and in a more naturalistic setting in which a beer brand was advertised during a basketball game involving students’ own university.

Social norms

Indirect experiences such as modeling by parents, peers, and media representations constitute a primary source of learning for youth. These social influences are crucial to the development of normative beliefs concerning the acceptability and prevalence of drinking, including the extent to which underage drinking is accepted, or even encouraged, by those in one’s environment. Perhaps the most widely accepted psychological model for the formation and consequences of social norms is Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977). According to this perspective, youth acquire their behavior through observation of social role models with whom they identify.

Ecological models highlight the powerful influence of social norms on adolescent and young adult substance use behaviors (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986; Hawkins et al., 1992). Normative beliefs about the prevalence of drinking (descriptive norms) and approval of alcohol use (injunctive norms) are among the strongest risk factors for alcohol use (D’Amico & McCarthy, 2006; Kelly et al., 2012; McAlaney et al., 2015). An emerging literature suggests that marketing and media alcohol portrayals play a powerful role in shaping drinking-related norms among youth. To date, the preponderance of work on peer and friend norms has focused on exposure to alcohol in films (Sargent et al., 2003), finding strong prospective associations between alcohol exposure and estimates of both close friend drinking (Gibbons et al., 2010; Wills et al., 2009) and alcohol use among peers (“kids your age”) (Dal Cin et al., 2009).

Formal tests of mediation support both descriptive and injunctive social norms as an important mechanism underlying the association between exposure to alcohol content and alcohol use. Associations are observed across a range of stages of alcohol involvement, age groups, controls, and study designs and include exposure to alcohol content in social media (Nesi et al., 2017; Yang & Zhao, 2018), popular music (Slater & Henry, 2013), and films (Dal Cin et al., 2009; Janssen et al., 2018a; Osberg et al., 2012; Wills et al., 2009). For example, Janssen and colleagues (2018a) showed that alcohol exposure in movies predicted changes in how adolescents perceive alcohol use among their peers, which was a partial mechanism underlying the effect of movie alcohol exposure on subsequent drinking initiation. Likewise, Osberg and colleagues (2012) found both descriptive peer norms and injunctive friend norms for drinking to mediate the association between exposure to films that glorified college drinking and typical weekly drinking and drinking consequences. Consistent with the broader literature, stronger effects were observed for friend (vs. peer) norms, suggesting that movie alcohol exposure exerts its influence via perceptions of alcohol use among friends but not peers more generally (Dal Cin et al., 2009).

A major source of social influence is direct advertising from alcohol manufacturers, which often includes product placement in the entertainment media. Youth view messages in the mass media as entertainment, without the skepticism reserved for advertising messages (Dal Cin et al., 2009). In the quest to develop identity, youth may be particularly susceptible to prominent media figures who serve as influential “super peers” (Brown et al., 2005; Distefan et al., 2004; Elmore et al., 2017). These models provide information on norms and contexts for alcohol use and serve to socialize youth attitudes about the prevalence and acceptability of underage drinking (Anderson et al., 2009; Elmore et al., 2017; Sargent et al., 2006). In addition, social media sites provide “virtual” peers, expanding the individual’s social network and providing information about drinking norms beyond one’s real-world peers (Scull et al., 2010). Portrayals of drinking in marketing and the media increase its perceived normativeness in the broader culture, thereby contributing to overestimation of peer alcohol use and approval of use.

The power of social norms can also explain the effectiveness of the so-called “viral marketing” phenomenon in digital media (Jernigan & Rushman, 2014; Jernigan et al., 2017a). Viral marketing leverages peer-to-peer transmissions in which viewers become active agents in product promotion (Alhabash et al., 2015). Users interact with social media sites through liking, sharing, retweeting, following, posting comments, or posting branded commercial messages and photos of products (either commercial or user generated). When users share content generated by alcohol manufacturers with their friends, they serve not only to redistribute commercial messages to potential customers (Jernigan & Rushman, 2014; Winpenny et al., 2014) but also to communicate and strengthen alcohol-related norms, which then drive subsequent drinking behavior.

Unlike traditional mass media, social media includes both industry-generated and user-generated content. The latter involves both user-generated branding, in which individuals promote their own sense of brand meaning (Arnhold, 2010; Griffiths & Casswell, 2010; Nicholls, 2012), and user-created alcohol content, in which individuals promote alcohol consumption independent of brand influence (Moreno et al., 2012; Morgan et al., 2010; Ridout et al., 2012). These activities often blend seamlessly with industry-generated content, making them difficult to distinguish (Brodmerkel & Carah, 2013). When the message source is peers and friends rather than the alcohol industry, pro-alcohol messages are seen as more authentic. Moreover, the large public audience typical of digital media produces a multiplier effect, increasing advertising effectiveness (Lyons et al., 2014; McCreanor et al., 2008). These factors make viral marketing extremely powerful yet less controllable than traditional marketing. Consumers are encouraged to engage with digital marketing, for example, by uploading photos of themselves drinking (Atkinson et al., 2014; Nicholls, 2012). Given that social media platforms lack adequate mechanisms for barring underage visitors, viral marketing has the potential to assimilate youth culture, even among alcohol-naive youth.

Experimental manipulations of exposure to alcohol-related content on fabricated social network profiles yield inflated perceptions of descriptive peer drinking norms. In a seminal study that manipulated descriptive norms for peer drinking through Facebook profiles, more favorable images of drinkers, positive attitudes toward use, and greater willingness to use were reported after viewing pages portraying alcohol consumption (vs. no consumption; Litt & Stock, 2011). A related study documented higher estimates of college student drinking subsequent to viewing a Facebook user profile containing alcohol-related photos and comments (Fournier et al., 2013). In addition, a recent study examined in vivo exposure to alcohol advertising using innovative ecological momentary assessment methods and found that alcohol use was perceived as more normative among both same-grade students and teenagers in general during times of exposure, which was predominately through outdoor and television advertisements (Collins et al., 2016; Martino et al., 2016, 2018). Moreover, these ad-induced changes in normative beliefs decayed at a slower rate than average time to re-exposure (Martino et al., 2018).

The evidence gathered from observational and experimental studies described above demonstrates that alcohol-related marketing and media content clearly has powerful effects on (mis)perceptions of peer alcohol use, supporting the plausibility of the idea that exposure to such content alters youth behavior through well-known psychological processes. Given that psychological theories such as Social Learning Theory posit within-person mechanisms, event-based correlational studies and tightly controlled experimental studies such as those reviewed above as well as rigorous evaluation of mechanisms within prospective studies are crucial for making inferences about within-person mechanisms of influence and, ultimately, for building a case for the psychological plausibility of social norms as a mechanism through which exposure to alcohol content can increase risk for underage drinking.

Theoretical Models

Message Interpretation Processing Model

The Message Interpretation Processing Model (Austin, 2007; Austin & Meili, 1994) holds that the way individuals interpret advertising content is as important as the exposure itself in explaining its effectiveness (Grube & Wallack, 1994). According to the Message Interpretation Processing Model, young people evaluate media messages using a combination of logic (i.e., whether the information conveyed in the message squares with their understanding of reality) and affective reactions. If persuasive messages are judged to be illogical, they will be rejected and have little influence over behavior. However, if not rejected, messages with some degree of similarity (i.e., messages that reflect the individual’s normative personal experience) are said to elicit varying degrees of identification. To the extent that advertisements portray alcohol use—and alcohol users—in a positive light (Grube, 1993, 2004), identification with alcohol portrayals can lead to the development of positive expectancies and, ultimately, alcohol use (McClure et al., 2013). Interpretation of alcohol-related media messages appears to influence normative perceptions as well. High school students who rated such messages as accurately portraying teens’ lives estimated greater alcohol use among kids their age, and perceptions that alcohol-related media messages portray teens similar to themselves were associated with greater estimates of the social acceptability of alcohol-using peers (Elmore et al., 2017).

An important construct related to message interpretation is marketing receptivity, or the extent to which an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by persuasive appeals (Pierce et al., 1998). Initially operationalized for tobacco marketing (Pierce et al., 1998), this concept has been applied to alcohol marketing research (Henriksen et al., 2008; McClure et al., 2013; Unger et al., 2003). In a seminal model proposed by McClure and colleagues, marketing receptivity is portrayed as a sequence of steps, each representing greater involvement with and influence from marketing (McClure et al., 2013). Initial steps (“low receptivity”) are characterized by brand awareness and recognition, intermediate steps (“moderate receptivity”) are associated with endorsement of favored ads or marketing campaigns, and final steps (“high receptivity”) are evident through owning and/or displaying alcohol-branded merchandise such as clothing. These continuous stages of marketing receptivity are sequentially and reciprocally linked to the progression of alcohol use spanning initiation through heavy drinking, with greater engagement in marketing corresponding to heavier stages of drinking (McClure et al., 2013; Tanski et al., 2015). Moreover, this model supports marketing-specific cognitions (drinker identity, favorite alcohol brand), but not alcohol-specific cognitions (expectancies, social norms), as mediators of the association between alcohol marketing and drinking. Earlier work by McClure and colleagues demonstrated that ownership of alcohol-branded merchandise, a marker of advertising receptivity that reflects both exposure and positive affective reaction to the message, was in fact associated with drinking initiation (McClure et al., 2006) and heavy drinking (McClure et al., 2006, 2009) to a greater extent than more passive exposure such as movie alcohol brand content (McClure et al., 2006). These studies controlled for a broad range of potential confounders shown to be associated with both alcohol-branded merchandise ownership and alcohol involvement, including personality factors such as sensation seeking, social influences such as peer drinking and involvement in extracurricular activities, perceived alcohol availability in the home, parenting style, and parental drinking, suggesting it is not simply an aspect of the child or his/her environment that accounts for the relationship between receptivity to marketing and youth drinking. Clearly, additional research on this topic is warranted.

Prototype Willingness Model

The cognitive mechanisms reviewed above include alcohol-related attitudes and formation of alcohol-related expectancies. Two additional cognitive mechanisms proposed to underlie the effect of exposure to alcohol content on youth alcohol use are drinker prototypes and behavioral willingness, both of which are described in the Prototype Willingness Model. This model focuses on the cognitions that mediate the effects of environmental and social factors on risk-taking behaviors, with more favorable images of the typical person their age (prototype) increasing willingness to engage in a risky behavior. Favorable norms lead to more favorable perceptions of a risk-taker’s image and greater willingness and intentions to perform a risky behavior (Dal Cin et al., 2009; Gerrard et al., 2008). Perceived drinking norms have been shown to be associated with greater willingness to engage in alcohol use (Blanton et al., 1997; Gibbons et al., 1995, 2010; Janssen et al., 2018a; Litt & Stock, 2011; Pomery et al., 2005), more favorable drinker prototypes (Blanton et al., 1997; Litt & Stock, 2011; Martino et al., 2016), and lower perceived vulnerability to the consequences of drinking (Gerrard et al., 2008). Injunctive (as opposed to descriptive) norms may be particularly predictive of drinker prototypes, because the qualities associated with the typical drinker may include tacit measures of perceived social approval, such as popularity or coolness (Elmore et al., 2017).

Reinforcing Spirals Model

The models reviewed thus far assume a unidirectional influence of marketing and media on cognitions and behavior. Slater (2007) proposed the Reinforcing Spirals Model, which posits that media selectivity and effects are dynamic, bidirectional, mutually influential processes. That is, exposure to alcohol content may encourage youth to engage in alcohol use, which then could increase their propensity to seek out media that positively portray and encourage alcohol use. Pro-alcohol media content essentially reinforces the adolescent’s emerging social identity as a drinker, leading them to continue their alcohol involvement and seek out additional alcohol content. Bidirectional, prospective (1year) associations between alcohol-related media content and adolescent drinking have been observed, although the pathway from media exposure to alcohol use is stronger than the converse (Tucker et al., 2013). Associations between exposure to alcohol content and peer norms may be the result of selection (youth who affiliate with peers favoring drinking may seek out media with alcohol content) as well as socialization (viewing alcohol content may make youth more vulnerable to social influence) (Gibbons et al., 2010).

However, a recent study found that viewing alcohol content in films was associated with changes in perceived (descriptive and injunctive) norms but failed to find evidence for the converse, suggesting that youth are not necessarily seeking out alcohol content as a function of associating with friends and peers with alcohol-permissive beliefs (Janssen et al., 2018a). Future work using multivariate modeling of multiwave data within the Reinforcing Spirals Model framework could provide important information about temporality and ultimately contribute to a basis for causality in the alcohol marketing–youth drinking link.

Conclusions

The purpose of this review was to consider the psychological plausibility of several mechanisms that have been proposed to support a causal effect of alcohol advertising on youth drinking. Psychological plausibility is but one criterion posited by formal systems of evaluation to be important for establishing causal relations among constructs. Thus, it was not the intention of this article to provide any kind of definitive resolution to the question of whether alcohol advertising and marketing cause underage drinking. Because our article is theory driven rather than a formal systematic review of the literature reporting associations among psychological risk factors, alcohol marketing exposure, and youth drinking, this report is somewhat limited in scope. Nevertheless, some broad conclusions are warranted on the basis of the research reviewed here.

It bears repeating that it is the intention of advertising and marketing to instill positive evaluations of advertised products, thereby encouraging intentions to purchase and ultimately consume or use those products (Wood, 2009). Advertisers and marketers routinely leverage evidence generated in basic psychological research (e.g., on attitude formation and consumer behavior) to design campaigns intended to achieve those ends. Thus, it should come as no surprise that young people’s alcohol-related attitudes and behaviors are influenced by exposure to alcohol advertising and media content.

The evidence reviewed here leads us to conclude that exposure to alcohol advertising and media content influences a host of psychological processes, some operating at the individual or intrapersonal level (familiarity, attitude formation, evaluative conditioning, expectancies) and others at the social or interpersonal level (individual and group identification, social norms), and that changes in these processes affect the likelihood that adolescents will initiate and maintain alcohol involvement. Moreover, in some cases there is evidence for a reciprocal relationship, such that alcohol involvement influences preferences for or likelihood of exposure to alcohol-related media content. These factors work together in a complex chain of influence, as depicted in the conceptual model shown in Figure 1. The figure depicts associations for which at least some empirical evidence exists in the published literature, with stronger evidence represented in bolded paths and lack of evidence (either the result of null findings or because these associations have yet to be tested in the literature) shown in lighter arrows. Note, too, that this model is not meant to be comprehensive; there likely are additional associations among various elements that are not depicted here (e.g., reciprocal effects between social identification and social norms, between expectancies and other cognitive mechanisms).

Individual psychological theories predict effects of marketing exposure on specific outcomes depicted in the model (e.g., increasing personal and social identification with drinking, forming positive expectancies regarding alcohol’s effects), and numerous empirical observations support links between those outcomes and drinking-related behaviors. Broader, integrated models posit connections among specific mediating variables; these are represented in our model by colored outlines and pathways. The extant literature provides the most consistent support for social norms as a mediator. In contrast, support for expectancies as a mediator is less robust. That is, perceptions of others’ behaviors and attitudes in relation to alcohol may be a more potent driver of drinking behavior than are individual personal evaluations of drinking outcomes. This conclusion is consistent with observations that advertisements communicate more about who you are, or who you could be, if you consume a specific brand of alcohol than about what might result if you drink alcohol (Martino et al., 2016).

It is important to recognize that the literature reviewed above is focused on Western cultures, predominately studies from the United States and northern Europe. There is a gap in the field with regard to the association between exposure to alcohol marketing and youth drinking, and the applicability of the conceptual model, for non-Western cultures and low and middle income countries, many of whom have recently been targeted by alcohol corporations as emerging alcohol markets (Jernigan & Babor, 2015; Jiang et al., 2017). Themes that appeal to underage youth such as camaraderie and celebrity models are evident in alcohol marketing in Southeast Asia (Lee et al., 2012) and Africa (Jernigan & Babor, 2015). Non-Western youth are exposed to alcohol-related advertising through the mass media and international sponsorship of sports events (Jernigan, 2010; Jernigan & Babor, 2015; Pinsky et al., 2017; World Health Organization, 2006) and through social media (Kaewpramkusol et al., 2019). Little empirical research has examined the association between alcohol-related marketing and youth drinking in non-Western countries, although two recent longitudinal studies conducted with Thai adolescents have shown greater alcohol initiation following exposure to alcohol media (TV, films, magazine/newspaper, billboard, and Internet) (Chang et al., 2016) and television alcohol advertisements (Chen et al., 2017).

For the most part, the pathways in the conceptual model have not been tested in non-Western cultures. Qualitative work has supported the roles of brand familiarity and favorability (Kaewpramkusol et al., 2019; Pinsky et al., 2017) and personal identity (Dumbili & Williams, 2017) in the marketing–alcohol link. Interestingly, although the Western studies reviewed above showed tenuous support for alcohol expectancies as a pathway, there does seem to be support for expectancies as a pathway in non-Western cultures. A study of Thai adolescents showed that time spent watching television was associated with a subsequent increase in positive alcohol expectancies, especially relaxation and tension reduction, and a decrease in negative alcohol expectancies, presumably as a result of greater exposure to televised alcohol ads (Chen et al., 2017). Young people in Nigeria associated recreational drinking with Western media images portraying alcohol with themes of successes and wealth more so than local media images, which contained negative alcohol portrayals (Dumbili & Henderson, 2017). It is possible that Western alcohol marketing and media exposure are more influential in developing countries without a history of alcohol advertising and integrated marketing. Indeed, holding a more Western cultural orientation increases the likelihood of drinking in adolescents and this association is mediated through the expectancies about the effects of alcohol (Shell et al., 2010). At the same time, the phenomenon of viral marketing may be less prominent in cultures with lower tolerance for free speech and freedom to express views, including on social media. We encourage future research on global alcohol marketing to attend to both common and culturally-specific influences underlying alcohol marketing influences on youth drinking.

Recommending policy changes to the alcohol industry is unlikely to be successful in the current environment, which emphasizes self-regulation. However, as evidence accumulates regarding the association between alcohol marketing and underage drinking, it is possible to reach scientific consensus about whether that relationship is causal. A statement of causality could be the basis for a more muscular approach to government oversight. In the meantime, it is crucial that researchers continue to identify modifiable targets of intervention. Reducing misperceptions of alcohol use and approval of use among important social role models may serve to reduce drinking behavior directly as well as indirectly by virtue of modifying ones’ cognitions related to interpretation of media and marketing messages. Careful consideration of how alcohol exposure is operationalized (marketing vs. entertainment media, traditional vs. digital media, industry sponsored vs. user generated, in vivo vs. cumulative exposure, simple dosage effects vs. stages of personal involvement) is crucial for future research, as is precision regarding the outcomes under investigation (intention, initiation, consumption, heavy use, problems). Last, considerably more research is needed to understand the extent to which theoretically relevant psychological processes identified in the literature have unique effects on youth drinking outcomes (Dal Cin et al., 2009; Janssen et al., 2018a; McClure et al., 2013; Osberg et al., 2012; Wills et al., 2009).

Footnotes

This research was supported by Grants R01AA021347, R01AA025451, and K02AA13938 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Both authors contributed equally to preparation of this article.

References

- Abelson R. P., Aronson E., McGuire W. J., Newcomb T. M., Rosenberg M. J., Tannenbaum P. H. Theories of cognitive consistency: A sourcebook. Chicago, IL: Rand-McNally; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Algesheimer R., Dholakia U. M., Herrmann A. The social influence of brand community: Evidence from European car clubs. Journal of Marketing. 2005;69:19–34. doi:10.1509/jmkg.69.3.19.66363. [Google Scholar]

- Alhabash S., McAlister A. R., Quilliam E. T., Richards J. I., Lou C. Alcohol’s getting a bit more social: When alcohol marketing messages on Facebook increase young adults’ intentions to imbibe. Mass Communication & Society. 2015;18:350–375. doi:10.1080/1520543 6.2014.945651. [Google Scholar]

- Alhabash S., VanDam C., Tan P.-N., Smith S. W., Viken G., Kanver D., Figueira L. 140 characters of intoxication: Exploring the prevalence of alcohol-related tweets and predicting their virality. SAGE Open. 2018;8:1–15. doi:10.1177/2158244018803137. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P., de Bruijn A., Angus K., Gordon R., Hastings G. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2009;44:229–243. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn115. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnhold U. User generated branding: Integrating user generated content into brand management. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer; 2010. doi:10.1007/978-3-8349-8857-7. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson A. M., Ross K. M., Begley E., Sumnall H. Constructing alcohol identities: The role of social network sites (SNS) in young peoples’ drinking cultures. Alcohol Insight. 2014;119 Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7e4b/268430c69cf819ad91012197ccf61de89942.pdf?_ga=2.126015620.827902723.15621789411180956199.1562178941. [Google Scholar]

- Austin E. W. Encyclopedia of children, adolescents, and the media. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. The message interpretation process model; pp. 535–536. [Google Scholar]

- Austin E. W., Meili H. K. Effects of interpretations of televised alcohol portrayals on children’s alcohol beliefs. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 1994;38:417–435. doi:10.1080/08838159409364276. [Google Scholar]

- Baeyens F., Eelen P., Crombez G., De Houwer J. On the role of beliefs in observational flavor conditioning. Current Psychology. 2001;20:183–203. doi:10.1007/s12144-001-1026-z. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Barry A. E., Bates A. M., Olusanya O., Vinal C. E., Martin E., Peoples J. E., Montano J. R. Alcohol marketing on Twitter and Instagram: Evidence of directly advertising to youth/adolescents. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2016;51:487–492. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv128. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agv128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry A. E., Johnson E., Rabre A., Darville G., Donovan K. M., Efunbumi O. Underage access to online alcohol marketing content: A You Tube case study. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2015;50:89–94. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu078. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agu078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholow B. D., Loersch C., Ito T. A., Levsen M. P., Volpert-Esmond H. I., Fleming K. A., Carter B. K. University-affiliated alcohol marketing enhances the incentive salience of alcohol cues. Psychological Science. 2018;29:83–94. doi: 10.1177/0956797617731367. doi:10.1177/0956797617731367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R. F., Leary M. R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettman J. R., Johnson E. J., Payne J. W. Consumer decision making. In: Robertson T. S., Kassarjian H. H., editors. Handbook of consumer behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1991. pp. 50–84. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton H., Gibbons F. X., Gerrard M., Conger K. J., Smith G. E. Role of family and peers in the development of prototypes associated with substance use. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:271–288. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.11.3.271. [Google Scholar]

- Borzekowski D. L. G., Ross C. S., Jernigan D. H., DeJong W., Siegel M. Patterns of media use and alcohol brand consumption among underage drinking youth in the United States. Journal of Health Communication. 2015;20:314–320. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.965370. doi:10.1080/10810730.2014.965370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle S. C., LaBrie J. W., Froidevaux N. M., Witkovic Y. D. Different digital paths to the keg? How exposure to peers’ alcohol-related social media content influences drinking among male and female first-year college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;57:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.01.011. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer M. B. Social identity and close relationships. In: Forgas J. P., Fitness J., editors. Social relationships: Cognitive, affective, and motivational processes. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2008. pp. 167–184. [Google Scholar]

- Brodmerkel S., Carah N. Alcohol brands on Facebook: The challenges of regulating brands on social media. Journal of Public Affairs. 2013;13:272–281. doi:10.1002/pa.1466. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. The American Psychologist. 1979;34:844–850. doi:10.1037/0003066X.34.10.844. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:723–742. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723. [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. D., Halpern C. T., L’Engle K. L. Mass media as a sexual super peer for early maturing girls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.003. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke P. J., Reitzes D. C. The link between identity and role performance. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1981;44:83–92. doi:10.2307/3033704. [Google Scholar]

- Casswell S. Alcohol brands in young peoples’ everyday lives: New developments in marketing. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2004;39:471–476. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh101. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agh101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth. Youth exposure to alcohol advertising on television, 2001-2009. Baltimore, MD: Author; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chang F. C., Miao N. F., Lee C. M., Chen P. H., Chiu C. H., Lee S. C. The association of media exposure and media literacy with adolescent alcohol and tobacco use. Journal of Health Psychology. 2016;21:513–525. doi: 10.1177/1359105314530451. doi:10.1177/1359105314530451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. Y., Huang H. Y., Tseng F. Y., Chiu Y. C., Chen W. J. Media alcohol advertising with drinking behaviors among young adolescents in Taiwan. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017;177:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.041. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung P. J., Garfield C. F., Elliott M. N., Ostroff J., Ross C., Jernigan D. H., Schuster M. A. Association between adolescent viewership and alcohol advertising on cable television. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:555–562. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.146423. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.146423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D. B., Thatcher D. L., Tapert S. F. Alcohol, psychological dysregulation, and adolescent brain development. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:375–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00601.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. L., Martino S. C., Kovalchik S. A., Becker K. M., Shadel W. G., D’Amico E. J. Alcohol advertising exposure among middle school–age youth: An assessment across all media and venues. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;77:384–392. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.384. doi:10.15288/jsad.2016.77.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. L., Martino S. C., Kovalchik S. A., D’Amico E. J., Shadel W. G., Becker K. M., Tolpadi A. Exposure to alcohol advertising and adolescents’ drinking beliefs: Role of message interpretation. Health Psychology. 2017;36:890–897. doi: 10.1037/hea0000521. doi:10.1037/hea0000521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchlow N., Moodie C., Bauld L., Bonner A., Hastings G. Awareness of, and participation with, digital alcohol marketing, and the association with frequency of high episodic drinking among young adults. Drugs: Education, Prevention, & Policy. 2016;23:328–336. doi:10.3 109/09687637.2015.1119247. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis B. L., Lookatch S. J., Ramo D. E., McKay J. R., Feinn R. S., Kranzler H. R. Meta-analysis of the association of alcohol-related social media use with alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems in adolescents and young adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2018;42:978–986. doi: 10.1111/acer.13642. doi:10.1111/acer.13642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S., Worth K. A., Gerrard M., Stoolmiller M., Sargent J. D., Wills T. A., Gibbons F. X. Watching and drinking: Expectancies, prototypes, and friends’ alcohol use mediate the effect of exposure to alcohol use in movies on adolescent drinking. Health Psychology. 2009;28:473–483. doi: 10.1037/a0014777. doi:10.1037/a0014777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico E. J., McCarthy D. M. Escalation and initiation of younger adolescents’ substance use: The impact of perceived peer use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.010. doi:10.1016/j. jadohealth.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Graaf A. Alcohol makes others dislike you: Reducing the positivity of teens’ beliefs and attitudes toward alcohol use. Health Communication. 2013;28:435–442. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.691454. doi:10.1080/10410236.2012.691454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer J., Thomas S., Baeyens F. Associative learning of likes and dislikes: A review of 25 years of research on human evaluative conditioning. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:853–869. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.853. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey M. A., Mitchell A. A. The influence of implicit attitudes on choice when consumers are confronted with conflicting attribute information. Journal of Consumer Research. 2010;37:614–625. doi:10.1086/653947. [Google Scholar]

- Distefan J. M., Pierce J. P., Gilpin E. A. Do favorite movie stars influence adolescent smoking initiation? American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1239–1244. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1239. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.7.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza G., Rao R. C. Can repeating an advertisement more frequently than the competition affect brand preference in a mature market? Journal of Marketing. 1995;59:32–42. doi:10.1177/002224299505900203. [Google Scholar]

- Dumbili E. W., Henderson L. Mediating alcohol use in Eastern Nigeria: A qualitative study exploring the role of popular media in young people’s recreational drinking. Health Education Research. 2017;32:279–291. doi: 10.1093/her/cyx043. doi:10.1093/her/cyx043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumbili E. W., Williams C. Awareness of alcohol advertisements and perceived influence on alcohol consumption: A qualitative study of Nigerian university students. Addiction Research and Theory. 2017;25:74–82. doi:10.1080/16066359.2016.1202930. [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis E. The advertised mind: Groundbreaking insights into how our brains respond to advertising. London, England: Millward-Brown; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly A. H., Chaiken S. The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Elmore K. C., Scull T. M., Kupersmidt J. B. Media as a “super peer”: How adolescents interpret media messages predicts their perception of alcohol and tobacco use norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2017;46:376–387. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0609-9. doi:10.1007/s10964-016-0609-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erevik E. K., Pallesen S., Andreassen C. S., Vedaa Ø., Torsheim T. Who is watching user-generated alcohol posts on social media? Addictive Behaviors. 2018;78:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.023. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchegaray N., Scherman A., Valenzuela S. Testing the hypothesis of “impressionable years” with willingness to self-censor in Chile. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. 2019;31:331–348. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edy012. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio R. H. Attitudes as object-evaluation associations: Determinants, consequences, and correlates of attitude accessibility. In: Petty R. E., Krosnick J. A., editors. Ohio State University series on attitudes and persuasion, Vol. 4: Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 247–282) Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Finkenauer C., Engels R., Meeus W., Oosterwegel A. Self and identity in early adolescence. In: Brinthaupt T. M., Lipka R. P., editors. Understanding early adolescent self and identity: Applications and interventions (pp. 25–56) Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming K., Thorson E., Atkin C. K. Alcohol advertising exposure and perceptions: Links with alcohol expectancies and intentions to drink or drinking in underaged youth and young adults. Journal of Health Communication. 2004;9:3–29. doi: 10.1080/10810730490271665. doi:10.1080/10810730490271665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier A. K., Hall E., Ricke P., Storey B. Alcohol and the social network: Online social networking sites and college students’ perceived drinking norms. Psychology of Popular Media Culture. 2013;2:86–95. doi:10.1037/a0032097. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M., Gibbons F. X., Houlihan A. E., Stock M. L., Pomery E. A. A dual-process approach to health risk decision making: The prototype willingness model. Developmental Review. 2008;28:29–61. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2007.10.001. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons F. X., Helweg-Larsen M., Gerrard M. Prevalence estimates and adolescent risk behavior: Cross-cultural differences in social influence. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1995;80:107–121. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.80.1.107. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.80.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons F. X., Pomery E. A., Gerrard M., Sargent J. D., Weng C. Y., Wills T. A., Yeh H.-C. Media as social influence: Racial differences in the effects of peers and media on adolescent alcohol cognitions and consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:649–659. doi: 10.1037/a0020768. doi:10.1037/a0020768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles D. C., Maltby J. The role of media figures in adolescent development: Relations between autonomy, attachment, and interest in celebrities. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36:813–822. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00154-5. [Google Scholar]

- Glasman L. R., Albarracín D. Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:778–822. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.778. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M. S., Brown S. A., Christiansen B. A., Smith G. T. Alcoholism and memory: Broadening the scope of alcohol-expectancy research. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:137–146. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.137. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M. S., Del Boca F. K., Darkes J. Alcohol expectancy theory: The application of cognitive neuroscience. In: Leonard K. E., Blane H. T., editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism (2nd ed., pp. 164–202) New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall C. E., Slater M. D. Automatically-activated attitudes as mechanisms for message effects: The case of alcohol advertisements. Communication Research. 2010;37:620–643. doi: 10.1177/0093650210374011. doi:10.1177/0093650210374011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon P. C., Holyoak K. J. Implicit learning and generalization of the “mere exposure” effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;45:492–500. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.3.492. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R., MacKintosh A. M., Moodie C. The impact of alcohol marketing on youth drinking behaviour: A two-stage cohort study. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2010;45:470–480. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq047. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agq047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald A. G., Banaji M. R., Rudman L. A., Farnham S. D., Nosek B. A., Mellott D. S. A unified theory of implicit attitudes, stereotypes, self-esteem, and self-concept. Psychological Review. 2002;109:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.1.3. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.109.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths R., Casswell S. Intoxigenic digital spaces? Youth, social networking sites and alcohol marketing. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2010;29:525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00178.x. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube J. W. Alcohol portrayals and alcohol advertising on television: Content and effects on children and adolescents. Alcohol Health & Research World. 1993;17:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Grube J. W. Alcohol in the media: Drinking portrayals, alcohol advertising, and alcohol consumption among youth. In: Bonnie R. J., O’Connell M. E., editors. Reducing underage drinking: A collective responsibility. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube J. W., Wallack L. Television beer advertising and drinking knowledge, beliefs, and intentions among schoolchildren. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:254–259. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.254. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.2.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha H. Y., John J., Janda S., Muthaly S. The effects of advertising spending on brand loyalty in services. European Journal of Marketing. 2011;45:673–691. doi:10.1108/03090561111111389. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins J. D., Catalano R. F., Miller J. Y. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heider F. The psychology of intergroup relations. New York, NY: Wiley; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L., Feighery E. C., Schleicher N. C., Fortmann S. P. Receptivity to alcohol marketing predicts initiation of alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.005. doi:10.1016/j. jadohealth.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A. B. The environment and disease: Association or causation? Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1965;58:295–300. doi: 10.1177/003591576505800503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R. W., Heeren T., Jamanka A., Howland J. Age of drinking onset and unintentional injury involvement after drinking. JAMA. 2000;284:1527–1533. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1527. doi:10.1001/jama.284.12.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S. S., Poorisat T., Neo R. L., Detenber B. H. Examining how presumed media influence affects social norms and adolescents’ attitudes and drinking behavior intentions in rural Thailand. Journal of Health Communication. 2014;19:282–302. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.811329. doi:10.1080/10810730.2013.811329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houben K., Schoenmakers T. M., Wiers R. W. I didn’t feel like drinking but I don’t know why: The effects of evaluative conditioning on alcohol-related attitudes, craving and behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:1161–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.012. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Alliance for Responsible Drinking. Guiding principles: Self-regulation of marketing communications for beverage alcohol. 2011. Retrieved from http://www.iard.org/resources/guiding-principles-selfregulation-marketing-communications-beverage-alcohol/ [Google Scholar]

- International Alliance for Responsible Drinking. Digital guiding principles: Self-regulation of marketing communications for beverage alcohol. 2014. Retrieved from http://www.iard.org/resources/digital-guidingprinciples-self-regulation-of-marketing-communications-for-beveragealcohol/ [Google Scholar]

- Jang W. Y., Frederick E. The influence of alcohol advertising? Effects of interpersonal communication and alcohol expectancies as partial mediators on drinking among college students. International Journal of Health, Wellness & Society. 2012;2:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen T., Cox M. J., Merrill J. E., Barnett N. P., Sargent J. D., Jackson K. M. Peer norms and susceptibility mediate the effect of movie alcohol exposure on alcohol initiation in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2018a;32:442–455. doi: 10.1037/adb0000338. doi:10.1037/adb0000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen T., Treloar Padovano H., Merrill J. E., Jackson K. M. Developmental relations between alcohol expectancies and social norms in predicting alcohol onset. Developmental Psychology. 2018b;54:281–292. doi: 10.1037/dev0000430. doi:10.1037/dev0000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H. The extent of global alcohol marketing and its impact on youth. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2010;37:57–89. doi:10.1177/009145091003700104. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H. Youth exposure to alcohol advertising on television--25 markets, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62:877–880. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6244a3.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]