Abstract

Background

Healthcare professionals frequently advise people to improve their health by stopping smoking. Such advice may be brief, or part of more intensive interventions.

Objectives

The aims of this review were to assess the effectiveness of advice from physicians in promoting smoking cessation; to compare minimal interventions by physicians with more intensive interventions; to assess the effectiveness of various aids to advice in promoting smoking cessation, and to determine the effect of anti‐smoking advice on disease‐specific and all‐cause mortality.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group trials register in January 2013 for trials of interventions involving physicians. We also searched Latin American databases through BVS (Virtual Library in Health) in February 2013.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials of smoking cessation advice from a medical practitioner in which abstinence was assessed at least six months after advice was first provided.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data in duplicate on the setting in which advice was given, type of advice given (minimal or intensive), and whether aids to advice were used, the outcome measures, method of randomisation and completeness of follow‐up.

The main outcome measure was abstinence from smoking after at least six months follow‐up. We also considered the effect of advice on mortality where long‐term follow‐up data were available. We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence in each trial, and biochemically validated rates where available. People lost to follow‐up were counted as smokers. Effects were expressed as relative risks. Where possible, we performed meta‐analysis using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model.

Main results

We identified 42 trials, conducted between 1972 and 2012, including over 31,000 smokers. In some trials, participants were at risk of specified diseases (chest disease, diabetes, ischaemic heart disease), but most were from unselected populations. The most common setting for delivery of advice was primary care. Other settings included hospital wards and outpatient clinics, and industrial clinics.

Pooled data from 17 trials of brief advice versus no advice (or usual care) detected a significant increase in the rate of quitting (relative risk (RR) 1.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.42 to 1.94). Amongst 11 trials where the intervention was judged to be more intensive the estimated effect was higher (RR 1.84, 95% CI 1.60 to 2.13) but there was no statistical difference between the intensive and minimal subgroups. Direct comparison of intensive versus minimal advice showed a small advantage of intensive advice (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.56). Direct comparison also suggested a small benefit of follow‐up visits. Only one study determined the effect of smoking advice on mortality. This study found no statistically significant differences in death rates at 20 years follow‐up.

Authors' conclusions

Simple advice has a small effect on cessation rates. Assuming an unassisted quit rate of 2 to 3%, a brief advice intervention can increase quitting by a further 1 to 3%. Additional components appear to have only a small effect, though there is a small additional benefit of more intensive interventions compared to very brief interventions.

Plain language summary

Does advice from doctors encourage people who smoke to quit

Advice from doctors helps people who smoke to quit. Even when doctors provide brief simple advice about quitting smoking this increases the likelihood that someone who smokes will successfully quit and remain a nonsmoker 12 months later. More intensive advice may result in slightly higher rates of quitting. Providing follow‐up support after offering the advice may increase the quit rates slightly.

Background

The role of healthcare professionals in smoking cessation has been the subject of considerable debate (Chapman 1993). During the late 1980s there was evidence from some randomised trials to suggest that advice from motivated physicians to their smoking patients could be effective in facilitating smoking cessation (Kottke 1988). However, concern was expressed about the low detection rate of smokers by many physicians and the small proportion of smokers who routinely receive advice from their physicians to quit (Dickinson 1989).

From a public health perspective, even if the effectiveness of facilitating smoking cessation by physicians is small, provided large numbers of physicians offer advice the net effect on reducing smoking rates could still be substantial (Chapman 1993). Since that time, there have been numerous attempts to encourage physicians to routinely identify all people who smoke and to provide smoking cessation advice (Fiore 1996; Fiore 2008; Raw 1998; Taylor 1994; West 2000).

The first systematic review on this topic was published over two decades ago (Kottke 1988). Since then a number of further studies have examined the effectiveness of medical practitioners in facilitating smoking cessation. Much of this research has occurred amidst a culture in which medical practitioners are playing an increasing role in health education and health promotion, and have an increasing array of options to assist people who want to quit. Doctors now have access to pharmacotherapies that have been shown to increase the chances of success for people making quit attempts, including nicotine replacement therapy (Stead 2012), bupropion (Hughes 2007) and varenicline (Cahill 2012). In some healthcare settings they can also refer people to more intensive behavioural counselling and support, either face‐to‐face (Lancaster 2005a; Stead 2005) or via telephone quitline services (Stead 2006). Specific theory‐based interventions have also been tested, based on approaches including the Transtheoretical Model (Velicer 2000; Cahill 2010), and motivational interviewing (Rollnick 1997; Lai 2010).

Objectives

The primary objective of the review was to determine the effectiveness of advice from medical practitioners in promoting smoking cessation. A secondary objective (added in 1996) was to determine the effectiveness of advice from medical practitioners on reducing smoking‐related mortality and morbidity. Our a priori hypotheses were:

advice from a medical practitioner to stop smoking is more effective than not giving advice.

the effectiveness of advice from a medical practitioner is greater if the advice is more intensive and includes follow‐up.

the supplementation of advice with aids such as self help manuals is more effective than advice alone.

motivational advice is more effective than simple advice (added in 2001 update).

The review does not address the incremental effects of adding nicotine replacement therapy or other pharmacotherapies to advice, as these interventions are addressed in separate Cochrane reviews (Cahill 2012; Hughes 2007; Stead 2012). From 2008 it does not address the incremental effect of demonstrating the pathophysiological effect of smoking (e.g. spirometry, expired carbon monoxide), which is covered by a separate Cochrane review (Bize 2012).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials. Trials where allocation to treatment was by a quasi‐randomised method were also included, but appropriate sensitivity analysis was used to determine whether their inclusion altered the results. Studies which used historical controls were excluded.

Types of participants

Participants could be smokers of either gender recruited in any setting, the only exception being trials which only recruited pregnant women. These were excluded since they are reviewed elsewhere (Lumley 2009).

Types of interventions

We included trials if they compared physician advice to stop smoking versus no advice (or usual care), or compared differing levels of physician advice to stop smoking. We defined advice as verbal instructions from the physician with a 'stop smoking' message irrespective of whether or not information was provided about the harmful effects of smoking. We excluded studies in which participants were randomised to receive advice versus advice plus some form of nicotine replacement therapy, since these were primarily comparisons of the effectiveness of NRT rather than advice. We excluded studies where advice to stop smoking was included as part of multifactorial lifestyle counselling (e.g. including dietary and exercise advice).

Therapists were physicians, or physicians supported by another healthcare worker. Trials which randomised therapists rather than smokers were included except where the therapists were randomised to receive an educational intervention in smoking cessation advice, since this is the subject of another Cochrane review (Carson 2012).

We defined trials where advice was provided (with or without a leaflet) during a single consultation lasting less than 20 minutes plus up to one follow‐up visit as minimal intervention. We defined a trial as intensive when the intervention involved a greater time commitment at the initial consultation, the use of additional materials other than a leaflet, or more than one follow‐up visit. We considered adjunctive aids to advice as additional strategies other than simple leaflets (e.g. demonstration of expired carbon monoxide or pulmonary function tests, self help manuals).

Types of outcome measures

The principal outcome used in the review was smoking cessation rather than reduction in withdrawal symptoms, or reduction in amount of cigarettes smoked. Thus we excluded trials that did not provide data on smoking cessation rates. In each study we used the strictest available criteria to define abstinence . That is, we used rates of sustained cessation rather than point prevalence abstinence where possible. Where biochemical validation was used, we classified only those people meeting the biochemical criteria for cessation as abstainers; and where participants were lost to follow‐up, they were regarded as continuing smokers. We required a minimum follow‐up of at least six months for inclusion, and used the longest follow‐up reported. A secondary outcome was the effect of smoking advice on subsequent mortality and morbidity.

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified trials from the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group specialised register. This has been developed from electronic searching of MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) together with handsearching of specialist journals, conference proceedings and reference lists of previous trials and overviews in smoking cessation. We used the following MeSH terms to identify reports of potentially relevant trials in the register: 'physician‐patient‐relations' or 'physicians' or 'family‐practice' or 'physician's‐role'. We also checked records with the terms 'general practice' or 'general practitioner' or 'GP' or 'physician*' in the title, abstract or any keyword field. At the time of the search in January 2013 the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), issue 12, 2013; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20130104; EMBASE (via OVID) to week 201252; PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20121231. See the Tobacco Addiction Group Module in The Cochrane Library for full search strategies and list of other resources searched, and Appendix 1 for the full search strategy used to identify reports of trials relevant to the topic.For this update we also searched in Latin American databases through BVS (Virtual Library in Health) which covered six databases (Lilacs, Biblioteca Cochrane, Wholis, Leyes, Scielo, Inbiomed) (Appendix 2). The most recent search of this was in February 2013.

Data collection and analysis

Data extraction:

In all versions of this review two people independently extracted data from the published reports. For this update, NP & DB reviewed potentially relevant reports and extracted data. Any disagreements were resolved by referral to a third author. For each trial, we documented the following aspects:

country of origin.

study population (including whether studies randomised only selected, motivated volunteers or all smokers, unselected by motivation to quit).

eligibility criteria.

nature of the intervention (including the nature, frequency and duration of advice, use of aids, and training of therapist).

details of study design (including method of allocation, blinding, study structure).

outcome measures.

validation of smoking status.

In trials where details of the methodology were unclear or where results were not expressed in a form that allowed extraction of the necessary key data, we wrote to the individual investigators to provide the required information. In trials where participants were lost to follow‐up they were regarded as being continuing smokers. Reports that only appeared in non‐English language journals were examined with the assistance of a translator.

Quality assessment:

For this update we assessed the methodological quality of the studies included in the review on three items covering two domains (Cochrane Handbook). We assessed the quality of sequence generation and allocation concealment as markers for the risk of selection bias, and we assessed the level and reporting of incomplete outcome data as a measure of attrition bias. JH‐B completed the Risk of Bias tables for studies already included in the review, and agreed bias assessments with LS.

Data Analysis:

We expressed results as the relative risk (intervention:control) of abstinence from smoking at a given point in time, or for mortality and/or morbidity, together with the 95% confidence intervals for the estimates. Early versions of this review used the odds ratio. but most clinicians find the relative risk more straightforward to interpret than the odds ratio.

We estimated pooled treatment effects using the Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect method. We now use the I² statistic to investigate statistical heterogeneity, given by the formula [(Q ‐ df)/Q] x 100, where Q is the Chi² statistic and df is its degrees of freedom (Higgins 2003). This describes the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than to sampling error (chance). A value greater than 50% may be considered substantial heterogeneity.

Studies that used cluster randomisation (with the physician or practice as the unit of allocation) were included in the meta‐analyses using the patient‐level data, but we assessed the effect on the results of excluding them. Where reported, we have recorded the statistical methods used in studies to investigate or compensate for clustering.

Results

Description of studies

We include 42 trials, published between 1972 and 2012 and including more than 31,000 participants. Twenty‐six trials with 22,000 participants contributed to the primary comparison between advice and a no‐advice or usual care control.

Seventeen studies compared a minimal advice intervention with a control intervention in which advice was not routinely offered. Eleven studies compared an intervention that we classified as intensive with a control. Fourteen studies (thirteen of which did not have a non‐advice control group) compared an intensive with a minimal intervention, and one study compared two intensive interventions (Gilbert 1992). One study compared an intervention based on the 4As model (Ask, Advise, Assist, Arrange follow‐up), delivered in two different styles (Williams 2002). Two studies compared advice to computer‐tailored letters (Meyer 2008; Meyer 2012). Some studies tested variations in interventions and contributed to more than one comparison. These are described and the meta‐analyses to which they contribute are identified in the Table 'Characteristics of included studies'.

The definition of what constituted 'advice' varied considerably. In one study (Slama 1995) participants were asked whether they smoked, and were given a leaflet if they wanted to stop. The control group were not asked about their smoking status until follow‐up. In all other studies the advice included a verbal 'stop smoking' message. This verbal advice was supplemented by provision of some sort of printed 'stop smoking' material (27 studies), or additional advice from a support health worker or referral to a cessation clinic or both. Four studies described the physician intervention as behavioural counselling with a stop‐smoking aim. Butler 1999 compared motivational consulting (based on information from theoretical models) with simple advice. In two studies the smoker was encourage to make a signed contract to quit (BTS 1990a; BTS 1990b). Higashi 1995 provided an incentive (a telephone card) to those who successfully quit. Three studies included an intervention which involved a demonstration of the participant's pulmonary function (Li 1984; Richmond 1986; Segnan 1991), or expired air carbon monoxide (Jamrozik 1984). Severson 1997, using a cluster design, compared information and a letter alone to advice from a paediatrician to mothers of babies attending well‐baby clinics with a view to reducing exposure of the children to passive smoke. Unrod 2007 used a computer‐generated tailored report to assist with cessation, and Meyer 2008 compared brief advice to computer‐generated tailored letters and to no intervention. Meyer 2012 compared brief advice, tailored letters and the combination of both. It only contributed to the direct comparison of advice and tailored letters

In the analysis we aggregated groups allocated to brief advice alone with those allocated to brief advice plus brief printed material. We did this with the view that advice plus provision of printed material is a practical approach in the primary care setting. In the two studies which directly compared the additional benefit of offering printed material none was observed (Jamrozik 1984; Russell 1979). Studies which provided a smoking cessation 'manual' were classified as offering an intensive intervention, but there is only weak evidence that self‐help materials have a small benefit when combined with face‐to‐face support (Lancaster 2005b). The intensive intervention subgroup also included studies that offered additional visits.

As required by the inclusion criteria, all trials assessed smoking status at least six months after the start of the intervention. Thirty‐one of the 42 studies (74%) had a longer follow‐up period, typically one year, the longest being three years. Since the interventions generally did not require a quit date to be set, the definitions of cessation used are less strict than are typically found in trials of pharmacotherapies. About half the studies defined the cessation outcome as the point prevalence of abstinence at the longest follow up, and the other half reported sustained abstinence, which typically required abstinence at an intermediate follow‐up point as well. Validation of all self‐reported cessation by biochemical analysis of body fluids or measurement of expired carbon monoxide was reported in 11 studies (26%) (Ardron 1988; BTS 1990a; BTS 1990b; Gilbert 1992; Hilberink 2005; Li 1984; Marshall 1985; Segnan 1991; Slama 1990; Vetter 1990; Williams 2002), but only three of these contributed to the primary analysis. Validation in a sample of quitters was reported in four studies (Lang 2000; Russell 1979; Russell 1983; Unrod 2007). Haug 1994 used biochemical validation at 12 months but not at 18 month follow‐up, and Richmond 1986 used biochemical validation or confirmation by a relative/friend. Fagerström 1984 adjusted rates based on the deception rate found in a subsample where validation was performed. No biochemical validation was used in the remaining 24 studies (57%).

Risk of bias in included studies

Sequence generation & allocation concealment (selection bias)

Nine trials were cluster‐randomised, with practices, physicians or clinics allocated to deliver a single condition (Haug 1994; Hilberink 2005; Janz 1987; Lang 2000; Meyer 2012; Morgan 1996; Unrod 2007; Severson 1997; Wilson 1990). In a further eight trials allocation to treatment was by day or week of attendance, so physicians delivered different interventions at different times (Burt 1974; Jamrozik 1984; Meyer 2008; Nebot 1989; Page 1986; Richmond 1986; Russell 1979, Russell 1983). All these studies are at potential risk of selection bias because individual smokers were likely to have been recruited by people who were not blind to treatment condition. We judged that the risk of bias was low when a systematic procedure for recruitment was described (usually involving screening questionnaires given to all participants before contact with the doctor), and there were no important differences in baseline characteristics. We judged risk to be high where differences in baseline characteristics and number recruited suggested selection bias (Hilberink 2005; Meyer 2012; Richmond 1986; Unrod 2007), or where the doctors themselves decided who to enrol (Haug 1994). Meyer 2008 was judged to be at high risk because each practice provided each of the three treatment conditions for a week, in the same order with a gap between recruitment periods; frequent attenders were therefore more likely to be assigned to the earlier conditions. Two studies were judged to be at low risk (Lang 2000; Wilson 1990). In this group of 17 studies, 13 were judged to be at high risk for one or both of the items related to selection bias.

Some studies reported post‐randomisation drop‐outs of clinics or physicians. We note in the Characteristics of included studies table where authors had allowed for or ruled out an effect of clustering, and we used sensitivity analyses to test the contribution of the cluster‐randomised trials to the meta‐analysis.

Of the remaining 25 studies using individual randomisation, two used methods which prevented allocation concealment by using elements of the medical record (Demers 1990) or birth date (Fagerström 1984), and were judged to be at high risk for both sequence generation and allocation concealment. Slama 1995 and Porter 1972 were judged to be at high risk of bias due to lack of allocation concealment. Most of the others did not give sufficient information about methods of sequence generation or allocation concealment to be judged as being at low risk.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Four studies (McDowell 1985; Meyer 2012; Richmond 1986; Slama 1995) were judged to be at high risk of attrition bias because it was unclear how many randomised participants had been lost to follow‐up or how they had been treated in the analyses, or because the loss to follow‐up was very different between groups.

Effects of interventions

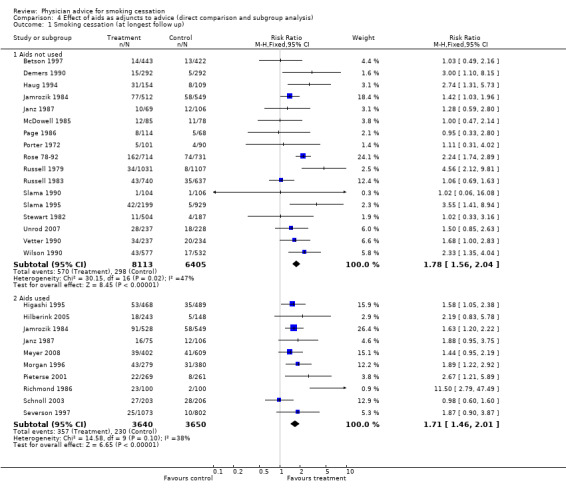

Advice versus no advice

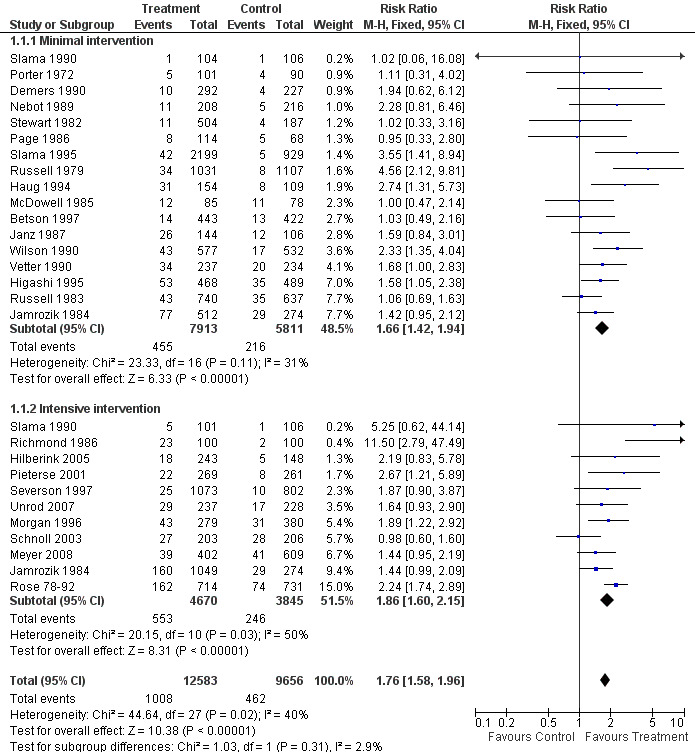

When all 17 trials of brief advice (as part of a minimal intervention) versus no advice (or usual care) were pooled, the results demonstrated a statistically significant increase in quit rates; relative risk (RR) 1.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.42 to 1.94 (Figure 1, Analysis 1.1.1). Heterogeneity was low (I² = 31%). When trials compared a more intensive intervention to a no‐advice control, the point estimate was a little larger, with moderate heterogeneity between the trials (11 trials, RR 1.86, 95% CI 1.60 to 2.15, I² = 50%, Figure 1, Analysis 1.1.2). Although the estimate for the more intensive subgroup was higher, the confidence intervals overlapped and the division of the trials into two groups based on this classification of intensity did not explain any of the overall heterogeneity (I² = 39% across the 28 trials). The estimated effect combining both groups was RR 1.76 (95% CI 1.58 to 1.96). We classified a more intensive intervention as a longer consultation, additional visits, or a self‐help manual. There is only weak evidence that self‐help materials have a small additional benefit when combined with face‐to‐face support (Lancaster 2005b), and the absence of a difference between the subgroups may in part reflect the difficulty in categorising intensity. From this indirect comparison there was insufficient evidence to establish a significant difference in the effectiveness of physician advice according to the intensity of the intervention.

1.

Effect of advice versus control (subgroups by intensity), Outcome: Smoking cessation at longest follow up

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Effect of advice versus control (subgroups by intensity), Outcome 1 Smoking cessation (at longest follow up).

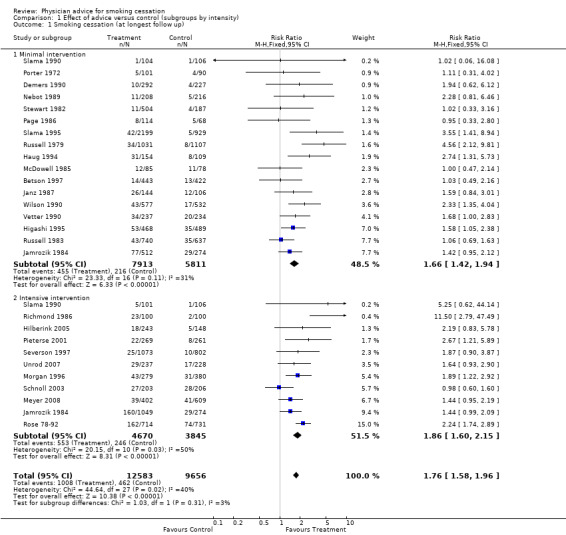

More intensive versus minimal advice

The direct comparison between intensive and minimal advice in 15 trials (Analysis 2.1) suggested overall that there was a small but significant advantage of more intensive advice (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.56), with little evidence of heterogeneity (I² = 32%). In the subgroup of 10 trials in populations of smokers not selected as having smoking‐related disease, the increased effect of the more intensive intervention was small and the confidence interval only narrowly excluded 1 (RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.43). No individual trials in this subgroup showed a significant benefit and there was no evidence of heterogeneity (I² = 0%). Statistical significance was lost if the trial that used cluster randomisation (Lang 2000) was removed. Amongst five trials in people with, or at high risk of, smoking‐related diseases the pooled estimate was larger, with little sign of heterogeneity, (RR 1.65, 95% CI 1.35 to 2.03, I² = 21%) and three of the trials showed significant effects. Since the confidence intervals overlapped this does not however provide strong evidence for a differential effect in these two populations.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Effect of intensive advice versus minimal advice, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation (at longest follow up).

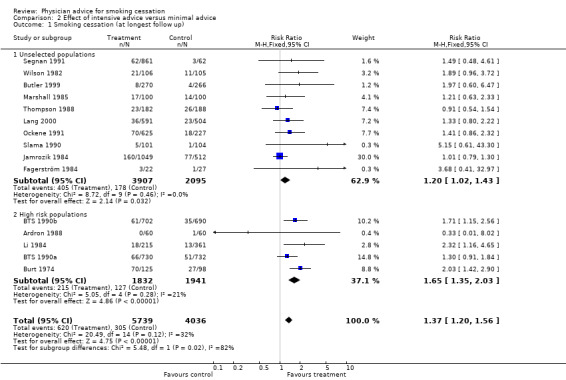

Number of follow‐up visits

The direct comparison of the addition of further follow‐up to a minimal intervention showed a barely significant increase in quitting in the pooled analysis, although none of the five studies individually detected significant differences (RR 1.52, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.14, Analysis 3.1). This analysis did not include one study of the effect of follow‐up visits (Gilbert 1992), because the control group received more than minimal advice, including two visits to the doctor. In this study, there was no significant difference in biochemically validated cessation rates between the two‐visit group and a group offered a further four follow‐up visits.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Effect of number of advice sessions (direct comparison and subgroup analysis), Outcome 1 Smoking cessation (at longest follow up).

Indirect comparison between subgroups of studies suggested that an intervention including follow‐up visits had a slightly larger estimated effect compared to no advice than an intervention delivered at a single visit . The RR for cessation when follow‐up was provided was 2.27 (six studies, 95% CI 1.87 to 2.75, I² = 30%, Analysis 3.1.2), compared to 1.55 (18 studies, 95% CI 1.35 to 1.79, I² = 35%, Analysis 3.1.4) when it was not.

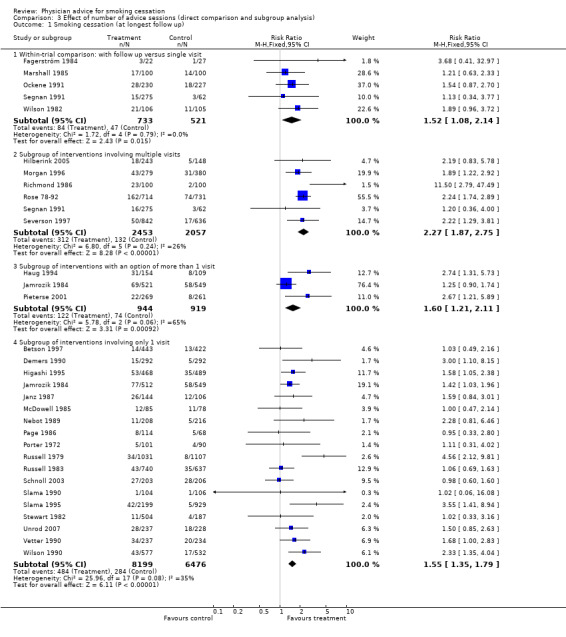

Use of additional aids

Indirect comparison between 10 studies in which the intervention incorporated additional aids such as demonstration of expired carbon monoxide levels or pulmonary function tests or provision of self‐help manuals and 17 where such aids were not used did not show important differences between subgroups (Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Effect of aids as adjuncts to advice (direct comparison and subgroup analysis), Outcome 1 Smoking cessation (at longest follow up).

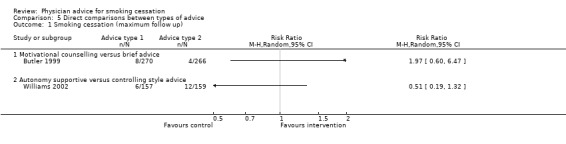

Comparisons between different types of advice

In a single trial of motivational counselling (approximately 10 minutes) compared to brief advice (2 minutes) a significant benefit was not detected, but the point estimate favoured the motivational approach and confidence intervals were wide (Butler 1999, RR 1.97, 95% CI 0.6 to 6.7, Analysis 5.1). Quit rates were low in both groups, but motivational advice appeared to increase the likelihood of making a quit attempt. This study also contributes to the comparison between intensive and minimal advice. Williams 2002, comparing brief advice using an autonomy‐supporting style to advice given in a controlling style, did not detect a significant difference. Quit rates were high in both groups and the point estimate favoured a controlling style (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.32, Analysis 5.1). Both interventions took about 10 minutes and this trial does not contribute to the intensive versus minimal comparison.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Direct comparisons between types of advice, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation (maximum follow up).

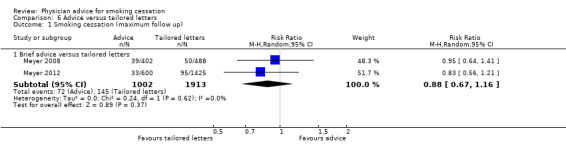

Comparison between advice and tailored letters

Two studies by the same research group compared brief advice to computer‐generated tailored letters (Meyer 2008; Meyer 2012). The pooled estimate favoured the tailored letter condition but confidence intervals included 1 (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.67 to 1.16). Meyer 2012 also tested a combination of advice and letters which was found to be more effective than either intervention alone, in both crude analyses and adjusting for baseline imbalance and missing data.

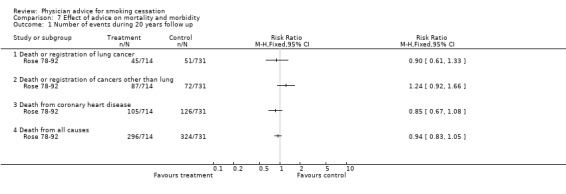

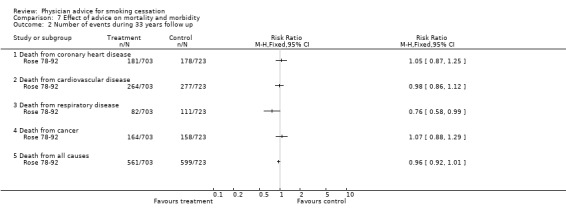

Effect of advice on mortality

Only one study (Rose 78‐92) has reported the health outcomes of anti‐smoking advice as a randomised single factor intervention. At 20‐year follow‐up, in the intervention compared to the control group, total mortality was 7% lower, fatal coronary disease was 13% lower and lung cancer (death plus registrations) was 11% lower. These differences were not statistically significant, reflecting low power and the diluting effects of incomplete compliance with the cessation advice in the intervention group, and a progressive reduction in smoking by men in the control group. After 33 years of follow‐up differences in rates for most causes of death were not significant but there was a significantly smaller number of deaths from respiratory conditions. The age‐adjusted hazard ratio was 0.72 (95% CI 0.54 to 0.96).

Sensitivity analyses

The results of the main meta‐analyses were not sensitive to exclusion of trials rated at high risk of bias on any single item, or to exclusion of all trials rated at high risk of bias for any item.

Discussion

The results of this review, first published in 1996 and updated in 2013 with one new study that did not contribute to the primary analyses, continue to confirm that brief advice from physicians is effective in promoting smoking cessation. Based on the results of a meta‐analysis incorporating 28 trials and over 20,000 participants, a brief advice intervention is likely to increase the quit rate by 1 to 3 percentage points. The quit rate in the control groups in the included studies was very variable, ranging from 1% to 14% across the trials in the primary comparison. However the relative effect of the intervention was much less variable, because trials with low control group quit rates generally had low rates with intervention, and vice versa. The general absence of substantial heterogeneity between trials when relative risks are compared makes for reliable estimates of relative effect. However it is more difficult to estimate the absolute effect on quitting, and the number needed to treat. Absolute quit rates will be influenced by motivation of the participants who are recruited or treated, the period of follow‐up, the way in which abstinence is defined, and whether biochemical confirmation of self‐reported abstinence is required. Many of the trials in this review were conducted in the 1970s and 1980s, and did not use the gold standard methods for assessing smoking abstinence that would now be recommended (West 2005). Only a minority of trials used biochemical measures to confirm self reports of abstinence, and although 12‐month follow‐up was common, many trials assessed smoking status at a single follow‐up point. This will tend to lead to higher quit rates overall than in trials with biochemical validation and requiring repeated abstinence at or between multiple assessments, but there is not strong evidence that it will lead to bias in the estimates of relative effect. There were too few trials in the primary analysis to test the effect size when including only trials with complete biochemical validation. We did not find that the control group quit rates were any less variable amongst studies with a longer period of follow‐up and with abstinence sustained at more than one assessment.

If an unassisted quit rate of 2% at 12 months in a population of primary care attenders is assumed, we can use the confidence intervals for the minimal intervention subgroup, 1.42 to 1.94, to estimate a number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) of 50 ‐ 120. If the background rate of quitting was expected to be 3%, then the same effect size estimate would translate to an NNTB of 35‐80. Using the pooled estimate from combining both intensity subgroups in the primary comparison would raise the lower confidence interval and reduce the upper estimate of the NNTBs.

Although the methodological quality of the trials was mixed, with a number using unclear or unsatisfactory methods of treatment allocation, our sensitivity analyses did not suggest that including these trials has led to any overestimate of treatment effects. Although we noted heterogeneity in some subgroups, overall the trials showed consistent relative effects. As noted above, the lack of biochemically validated cessation was the other possible methodological limitation.

Based on subgroup analyses there is little evidence about components that are important as part of an intervention, although direct comparison in a small number of trials suggest that providing a follow‐up appointment may increase the effect. Indirect comparisons indicate that various aids tested do not appear to enhance the effectiveness of physician advice. However, caution is required in interpreting such indirect comparisons since they do not take account of any inherent systematic biases in the different populations from which the study samples are drawn. Direct comparison of differing intensities of physician advice suggest a probable benefit from the more intensive interventions compared to a briefer intervention, although subgroup analyses suggest that this might be small or non‐existent in unselected smokers, but larger when provided to smokers in high risk groups. The effect of intensified advice in a population with established disease is however based on a small number of trials. If the marginal benefit of a more intensive advice‐based intervention is based on the pooled estimate combining unselected and high risk population subgroups (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.56), and assuming that the minimal intervention alone could achieve a quit rate of 3.5%, an NNTB of 50 ‐ 140 would be estimated for the effect of providing more support. There was insufficient evidence to draw any conclusion about the effect of motivational as opposed to simple advice (Butler 1999), or between different advice‐giving styles (Williams 2002). Two recent studies compared physician advice to mailed computer‐generated letters, using baseline data to tailor advice based on the transtheoretical model (Velicer 2000).

If these results are to translate into a public health benefit, the important issue will be the proportion of physicians who actually offer advice. Although 80% of the general population visit a physician annually, reports of the proportion who receive any form of smoking cessation advice vary considerably. While many of those who are not offered smoking cessation advice will quit unaided, every smoker who does not receive advice represents a 'missed opportunity'. Provision of lifestyle advice within the medical consultation is now promoted as a matter of routine, but advice on smoking may still not be offered systematically (Denny 2003; McLeod 2000). Not all primary care physicians agree that advice should be given at every consultation (McEwen 2001), and some practitioners still consciously choose not to raise smoking cessation as an issue in order to preserve a positive doctor‐patient relationship (Coleman 2000), although some research indicates that satisfaction may be increased by provision of advice (Solberg 2001). Two recent studies (Meyer 2008; Meyer 2012) compared physician advice to computer‐generated letters that were tailored to stage of change. The pooled estimate did not show a significant difference between the interventions. Although this type of approach could help practitioners to eliminate barriers against giving smoking cessation advice due to lack of time, financial resources or skills, the confidence intervals were too wide to be sure that effects were equivalent.

Several strategies have been shown convincingly to enhance the effectiveness of advice from a medical practitioner, including provision of pharmacotherapy. Effective pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation include nicotine replacement therapy (Stead 2012) bupropion or nortriptyline (Hughes 2007) and varenicline or cytisine (Cahill 2012). Use of these forms of therapy increases quit rates 1.5‐ to 2.5‐fold, and is a potentially valuable adjunct to any advice provided. Both individual and group‐based counselling are also effective at increasing cessation rates amongst smokers prepared to accept more intensive intervention (Lancaster 2005a; Stead 2005). Telephone counselling can also be effective (Stead 2006). National clinical practice guidelines generally advise the use of a brief intervention in which asking about tobacco use is followed by advice to quit, and an assessment of the smoker's willingness to make a quit attempt. Those willing to make a quit attempt can then be offered specific assistance and follow‐up (Fiore 2008; Miller 2001; NHC 2002; West 2000).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results of this review indicate the potential benefit from brief simple advice given by physicians to their smoking patients. The challenge as to whether or not this benefit will be realised depends on the extent to which physicians are prepared to systematically identify their smoking patients and offer them advice as a matter of routine. Providing follow‐up, if possible, is likely to produce additional benefit. However, the marginal benefits of more intensive interventions, including use of aids, are small, and cannot be justified as a routine intervention in unselected smokers. They may, however, be of benefit for individual, motivated smokers.

Implications for research.

Further studies of interventions offered by physicians during routine clinical care are unlikely to yield new information about the role of advice. Work is now required to develop strategies to increase the frequency with which smokers are identified and offered advice and support.

Feedback

Intention to treat analyses

Summary

I wonder whether the studies included were based on intention to treat analysis? If they were not, I believe that a selection of more motivated subjects has taken place even in studies where unselected populations were invited. Smokers who are not motivated to quit, do not take the same interest in such on offer. Intention to treat principles should be applied if the size of the effect should apply to whole practice populations.

Reply

In extracting data from the studies, the denominators were derived from the number of participants stated to be randomised to each condition, and participants lost to follow‐up were assumed to be continuing smokers, an intention to treat analysis. Where unselected participants were recruited, the results should therefore reflect whole practice smoker populations. However, the exact way in which participants were recruited differed between trials. In some studies where the intention was to recruit unselected participants, it may be that those recruited were not typical of the practice populations.

Contributors

Ann Dorrit Guassora (commenter); Lindsay Stead (author)

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 March 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Updated and additional authors added, no change to conclusions |

| 27 March 2013 | New search has been performed | Searches updated including new searches of Latin American databases. One new included study. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1996 Review first published: Issue 2, 1996

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 February 2008 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Updated for issue 2, 2008. Three new included studies added, new author added, and metric changed from odds ratios to risk ratios. |

| 12 July 2004 | New search has been performed | Updated for issue 4, 2004. Five additional studies added, and statistical methods for meta‐analysis changed from Peto to Mantel‐Haenszel. There were no major changes to the conclusions of the review. |

Notes

Chris Silagy was first author at the time of his death in 2001. The authors for citation were changed when the review was updated in 2004.

Acknowledgements

Chris Silagy initiated the review and was first author until his death in 2001. Sarah Ketteridge developed the initial version of this review and was a co‐author of the review until 1999. Ruth Ashenden provided technical support in the preparation of the initial version of this review. Gillian Bergson was a co‐author for the 2008 update of this review. Dr Chris Hyde, Iain Chalmers and Helen Handoll have all provided constructive comments on previous versions of the review which have been taken account of in the updates. Martin Shipley provided 33‐year follow‐up data on the Whitehall study (Rose 78‐92) via Iain Chalmers. Rafael Perera gave statistical and translation support for the 2008 update. Gillian Bergson extracted data from trials for the 2008 update, and contributed to revisions of the text.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Register search Strategy (2013 update, via Cochrane Register of Studies)

#1 Physician's Role:MH,EMT,KW #2 Physician‐Patient Relations:MH,EMT,KW #3 Family Practice:MH,EMT,KW #4 physicians*:MH,EMT,KW #5 general practice:TI,AB,EMT,KW #6 GP:TI,AB,EMT,KW #7 physician*:TI, AB,EMT,KW #8 general practitioner:TI,AB,EMT,KW #9 general practice:TI,AB,EMT,KW #10 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9

Appendix 2. Latin American database search via BVS

Covering Lilacs, Biblioteca Cochrane, Wholis, Leyes, Scielo, Inbiomed

Cese del Uso de Tabaco

Visita a Consultorio Médico

Relaciones Médico‐Paciente

Rol del Médico

Cese del Tabaquismo

Ensayo Clínico

"Cese del Uso de Tabaco" OR "Cese del Tabaquismo" AND "Ensayo Clínico" OR "Ensayo Clínico Controlado" OR "Ensayo Clínico Controlado randomisado"

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Effect of advice versus control (subgroups by intensity).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation (at longest follow up) | 26 | 22239 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.76 [1.58, 1.96] |

| 1.1 Minimal intervention | 17 | 13724 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.66 [1.42, 1.94] |

| 1.2 Intensive intervention | 11 | 8515 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.86 [1.60, 2.15] |

Comparison 2. Effect of intensive advice versus minimal advice.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation (at longest follow up) | 15 | 9775 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [1.20, 1.56] |

| 1.1 Unselected populations | 10 | 6002 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.20 [1.02, 1.43] |

| 1.2 High risk populations | 5 | 3773 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.65 [1.35, 2.03] |

Comparison 3. Effect of number of advice sessions (direct comparison and subgroup analysis).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation (at longest follow up) | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Within‐trial comparison: with follow up versus single visit | 5 | 1254 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.52 [1.08, 2.14] |

| 1.2 Subgroup of interventions involving multiple visits | 6 | 4510 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.27 [1.87, 2.75] |

| 1.3 Subgroup of interventions with an option of more than 1 visit | 3 | 1863 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.60 [1.21, 2.11] |

| 1.4 Subgroup of interventions involving only 1 visit | 18 | 14675 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.55 [1.35, 1.79] |

Comparison 4. Effect of aids as adjuncts to advice (direct comparison and subgroup analysis).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation (at longest follow up) | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Aids not used | 17 | 14518 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.78 [1.56, 2.04] |

| 1.2 Aids used | 10 | 7290 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.71 [1.46, 2.01] |

Comparison 5. Direct comparisons between types of advice.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation (maximum follow up) | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Motivational counselling versus brief advice | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Autonomy supportive versus controlling style advice | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 6. Advice versus tailored letters.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation (maximum follow up) | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Brief advice versus tailored letters | 2 | 2915 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.67, 1.16] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Advice versus tailored letters, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation (maximum follow up).

Comparison 7. Effect of advice on mortality and morbidity.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of events during 20 years follow up | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Death or registration of lung cancer | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Death or registration of cancers other than lung | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Death from coronary heart disease | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Death from all causes | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Number of events during 33 years follow up | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Death from coronary heart disease | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Death from cardiovascular disease | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Death from respiratory disease | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.4 Death from cancer | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.5 Death from all causes | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Effect of advice on mortality and morbidity, Outcome 1 Number of events during 20 years follow up.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Effect of advice on mortality and morbidity, Outcome 2 Number of events during 33 years follow up.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ardron 1988.

| Methods | Setting: Adult diabetic outpatient clinic in Liverpool, UK. Recruitment: volunteers who responded 'yes' to the question 'Do you want to give up smoking?' (selected by motivation). | |

| Participants | 60 clinically stable diabetic patients < 40 yrs, smoking > 5 cpd, motivated to stop. Therapists: medical registrar supported by health visitor. | |

| Interventions | 1. Routine advice (5 mins talk) 2. Intensive advice (longer talk, leaflet, and visit from heath visitor at home within two wks involving family, giving further advice and written materials). Intervention level: intensive (2) vs minimal (1). Aids used: none. Follow‐up visits: 1. | |

| Outcomes | Point prevalence at 6m. Validation: expired CO and urinary cotinine. | |

| Notes | Contributes data to intensive vs minimal comparison only. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomised"; details not provided. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants completed the study. |

Betson 1997.

| Methods | Setting: government outpatient clinic, Hong Kong. Recruitment: older smokers, unselected. | |

| Participants | 865 smokers, aged > 65, 92% male, 49% smoking > 10 cpd | |

| Interventions | 1. No intervention. 2. Written materials (Chinese translation of American Cancer Society booklet). 3. Physician advice (1min, based on 4As). 4. Physician advice and booklet. Intervention level: minimal (3 & 4). Aids used: none; follow‐up visits: none. | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 1 yr (sustained from 3m). Validation: poor response to request for urine specimen so data based on self report. | |

| Notes | Groups 3 & 4 compared to 1 & 2 for minimal advice vs control; full paper provided by Professor Lam. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "table of random numbers" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Every doctor was given a set of sealed envelopes with serial numbers."; unclear if envelopes were opaque |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 64% of participants provided data at 1 yr, breakdown by group not specified; participants with missing data were considered smoking. |

BTS 1990a.

| Methods | Setting: hospital or chest clinic in UK. Recruitment: volunteers selected by motivation. | |

| Participants | New patients with smoking‐related disease but not pregnant, terminally or psychiatrically ill. 1462 patients, smoking at least 1cpd, mean: 17cpd. Therapists: physicians. | |

| Interventions | 1. Advice. 2. Advice + signed agreement to stop, health visitor support, letters from physician. Intervention level: intensive vs minimal. Aids used: yes; Follow‐up visits: from health visitor, not doctor. | |

| Outcomes | Sustained at 12m (& 6m). Validation: expired CO. | |

| Notes | Contributes data to intensive vs minimal comparison only. (Two studies are reported in the same paper). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Patients were allocated at random." Method of sequence generation not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Patients were randomised using "a sequence of sealed envelopes." Unclear if envelopes were opaque. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Similar numbers lost in both groups (control 138/732; intervention 144/730); participants with missing data were considered smoking. |

BTS 1990b.

| Methods | Setting: hospital or chest clinic in UK. Recruitment: Volunteers selected by motivation. | |

| Participants | New patients with smoking‐related disease but not pregnant, terminally or psychiatrically ill. 1392 patients, smoke at least 1cpd, mean 17cpd. Therapists: physicians. | |

| Interventions | 1. Advice. 2. Advice plus signed agreement. 3. Advice plus letters of support. 4. Advice plus letters plus signed agreement. Intervention level: intensive vs minimal. Aids used: yes. Follow‐up visits: none. | |

| Outcomes | Sustained at 12 m (& 6m). Validation: expired CO. | |

| Notes | The use of supportive letters was classified as intensive, so 3 & 4 compared to 1 & 2 in the intensive vs minimal comparison; (two studies are reported in the same paper). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Patients were allocated at random."; method of sequence generation was not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Patients were randomised using "a sequence of sealed envelopes."; it is unclear whether envelopes were opaque. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Similar numbers lost across all 4 groups. 1) 72/343; 2) 80/347; 3) 90/351; 4) 86/351); participants with missing data were considered smoking. |

Burt 1974.

| Methods | Setting : hospital cardiac unit and cardiac outpatient clinic in Scotland Recruitment: consecutive survivors of acute myocardial infarction identified as smokers (unselected) | |

| Participants | 210 survivors of acute myocardial infarction Ages not stated; pipe and cigarette smokers Number of cpd not stated Therapists: hospital consultants, reinforced by junior medical and nursing staff | |

| Interventions | 1. Repeated emphatic advice to quit as an inpatient with follow up in a special clinic 2. Normal inpatient care followed by discharge to care of the family doctor Intervention level: intensive vs minimal Aids used: none. Follow‐up visits: yes, number not stated | |

| Outcomes | PP abstinence at 12m. Validation: none. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "Selection between the study and control groups was random, being determined by the day of admission." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not specified. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants "were followed up for one year or longer." |

Butler 1999.

| Methods | Setting: general practices (registrars), UK. Recruitment: All smokers attending for consultation (except those with terminal illness) (unselected). | |

| Participants | 536 smokers (70% female) at various stages of change. | |

| Interventions | 1. Standardised brief advice (estimated time 2 minutes). 2. Structured motivational counselling (mean length 10 mins) (based on stage of readiness to change). | |

| Outcomes | PP at 6m (self‐reported abstinence in the previous month). Validation: none | |

| Notes | Contributes data to intensive vs minimal comparison only. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sealed "numbered envelopes were filed in a study pack and clinicians were instructed to open them in order." Unclear if envelopes were opaque. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Similar number lost to follow‐up in both groups (brief advice: 54/266, motivational counselling: 64/270). Subjects missing data at follow‐up considered smokers. |

Demers 1990.

| Methods | Setting: family practices in southeast Michigan, USA. Recruitment: patients attending the practices in a defined intake period identified as smokers by questionnaire (unselected). | |

| Participants | 519 adult smokers; Mean cpd 22. Therapists : Family practitioners. | |

| Interventions | 1. 3 ‐ 5 min smoking cessation counselling and written materials plus routine care. 2. Routine care. Intervention level: minimal Aids used: none. Follow‐up visits: no. | |

| Outcomes | Sustained at 12m (& 6m). Validation: none. | |

| Notes | Sustained replaced PP abstinence from 2008. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "based on the last digit of their medical chart." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | By receptionist based on medical record number. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Similar percentages lost to follow‐up at 12m (38% intervention, 41% control). Participants missing data counted as smokers in final analysis. |

Fagerström 1984.

| Methods | Setting: Swedish general practices and industrial clinics. Recruitment: Smokers who were considered motivated to stop, accepted advice and agreed to follow‐up (selected). | |

| Participants | 145 adult smokers (49 in relevant arms), mean cpd: 19. Therapists: 10 Swedish GPs, 3 Swedish industrial physicians. | |

| Interventions | 1. Short follow‐up (advice plus 1 appointment). 2. Long follow‐up ( advice plus 2 appointments, phone call + letter). 3. Short follow‐up plus nicotine gum (not used in review). 4. Long follow‐up plus nicotine gum (not used in review). Intervention level: Intensive vs minimal. Aids used: yes. Follow‐up: 1 vs 2 visits. | |

| Outcomes | Sustained abstinence at 1, 6 and 12m. Validation: Results adjusted for 15% deception rate detected by expired CO measured in a random subset of claimed non‐smokers. | |

| Notes | Contributes data to intensive vs minimal comparison only. Adjusted rates used in analysis. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "Birthdate served as basis for randomisation". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Recruited by physicians and assigned by date of birth. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | "Results are based on the 145 patients who attended at least one follow‐up activity." Number of enrolled participants who did not attend any follow‐up activities not specified. |

Gilbert 1992.

| Methods | Setting: 41 family practices in Ontario, Canada. Recruitment: Patients volunteering for a smoking cessation programme in physician's office (selected). | |

| Participants | 647 smokers, mean cpd 22. Therapists: Family practitioners who had attended 4‐hr training session. | |

| Interventions | 1. Brief advice, self‐help booklet and 1 follow‐up visit including use of nicotine gum. 2. As group 1, plus 3 further follow‐up visits. | |

| Outcomes | Sustained at 12m (& 3m). Validation: salivary cotinine. | |

| Notes | Not included in any meta‐analysis table since the control group received more than a minimal intervention. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "computerized randomization program that balanced the number per group within each physician practice across each block of six patients". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The receptionist passed a sequence of numbered envelopes to the physician, containing the treatment randomization." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 98.4% participants followed up at one year. Participants missing data counted as smokers. |

Haug 1994.

| Methods | Setting: 187 general practices in Norway, Recruitment: opportunistically by the general practitioners (unselected), | |

| Participants | Reports separate trials in pregnant and non‐pregnant women: 274 non‐pregnant women age 18‐34: Smoking > 4 cpd, mean 13. Therapists: GPs. | |

| Interventions | 1. Advice + leaflet + invitation to attend 4 follow‐up visits. 2. Normal care controls. Intervention level: minimal. Aids used: none. Follow‐up visits: Offered. | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 18m. Validation: none (serum thiocyanate at 12m only). | |

| Notes | Cluster‐randomised, but 187 GPs so cluster size small. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomly allocating GPs into subgroups," method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | GPs recruited patients after they knew their group. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Drop‐outs not reported by group. Only completers included in analysis. |

Higashi 1995.

| Methods | Country: Japan. Recruitment: Primary Care (unclear whether selected). | |

| Participants | 957 adult smokers. | |

| Interventions | 1. Brief advice plus leaflet, encouragement card at 1m and telephone card at 6m. 2. No intervention. Intervention level: minimal. Aids used: yes. Follow‐up: no. | |

| Outcomes | PP abstinence at 12m. Validation: none. | |

| Notes | Information derived from English abstract. Full publication in Japanese and not translated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Number lost to follow‐up not specified. |

Hilberink 2005.

| Methods | Setting: 43 general practices in the Netherlands. Recruitment: Patients with COPD identified from medical records in participating practices (?unselected). | |

| Participants | 392 patients with COPD (244 intervention, 148 control due to drop‐out of large control group practices), cpd not stated. Intervention had more patients in preparation (25.8% vs 17.6%) or contemplation stage (32.0% vs 28.4%) P = 0.059. | |

| Interventions | 1. Intensive advice ‐ Initial session to identify preparers and contemplators, further 3 visits and up to 3 follow‐up phone calls from nurse, plus booklet and video. Use of NRT recommended. 2. No intervention (usual care). Intervention level: Intensive. Aids used: yes. Follow‐up visits: yes (for motivated patients). | |

| Outcomes | PP abstinence at 12m (reported in Hilberink 2011; 6m outcomes in original paper). Validation: urine cotinine 50 ng/mL at 12m. | |

| Notes | Multi‐level analysis did not alter results. Twelve‐month outcome replaces 6m results from 2013. Third arm involving advice about bupropion not included in analysis. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Cluster‐randomised by practice, method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Patients identified from medical records. Difference in baseline stage of change between conditions suggests selection bias. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Similar drop‐out and losses to follow‐up in both groups. 3/25 control practices and 2/23 intervention practices dropped out. Participants who dropped out considered to be smokers. |

Jamrozik 1984.

| Methods | Setting: general practices in Oxfordshire, UK. Recruitment: Identified smokers attending the practices during recruitment period (unselected). | |

| Participants | 2110 adult smokers, cpd not stated. Therapists: General practitioners who had in earlier studies indicated an interest in participating in smoking research. | |

| Interventions | 1. Normal care control group. 2. Brief advice to quit plus smoking cessation pamphlet. 3. Advice plus pamphlet plus a demonstration of the patient's level of exhaled CO (by research supervisor). 4. Advice plus pamphlet plus provision of a card offering follow‐up from health visitor. Intervention level: Minimal (groups 1 and 2), Intensive (groups 3 and 4). Aids used: Yes (groups 3 and 4). Follow‐up visits: Offered in group 4. | |

| Outcomes | PP abstinence at 12m. Validation: a sample of self‐reported quitters selected for urinary cotinine validation (up to 40% deception rate). Results not adjusted, and no evidence that deception rates differed in treatment and control groups. | |

| Notes | 2 compared to 1 for effects of minimal intervention, 3 & 4 compared to 1 for effects of intensive intervention. To avoid double counting group 1 when minimal and intensive pooled together, the control group is divided between the two categories. 3 & 4 compared to 2 for intensive vs minimal intervention, 4 compared to 1 for effects of intervention with offer of follow‐up | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Intervention condition determined by day of attendance |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Patients were screened by non‐blind study staff and smokers filled in a questionnaire before and after their appointment. "Each doctor was provided with a small desktop card reminding him of the 'treatment' to be given to smokers seen on that day". Risk not judged to be high. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "A one year questionnaire was returned by 72% of the smokers and the response rate did not vary appreciably among the four groups....Non‐responders assumed not to have stopped smoking." |

Janz 1987.

| Methods | Setting: Outpatient medical clinic at midwestern US teaching hospital/ Recruitment: Consecutive attenders identified as smoking over 5 cpd and giving consent to participation (unselected). | |

| Participants | 250 adult smokers, mean cpd 24. Therapists : Intervention physicians and nurses given brief tutorial. Control physicians not informed of study. | |

| Interventions | 1. Normal care. 2. Brief advice from physician and brief consultation from nurse. 3. As 2 plus self‐help manual. Intervention level: Minimal. Aids used: group 3. Follow‐up visits: no. | |

| Outcomes | PP abstinence at 6m. Validation : none. | |

| Notes | Numbers quit estimated from graphs with unclear denominators ‐ original data sought but not obtainable. 2 & 3 compared to 1 for minimal advice vs no advice (Classifying 3 as intensive does not alter meta‐analysis findings). 3 vs 1 in advice plus aids subgroup, 2 vs 1 in advice without aids. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "Each clinic site was divided into half‐day clinic units with each unit assigned to either experimental or control status." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Procedure for systematically identifying and recruiting patients described, no important differences in baseline characteristics. Risk not judged to be high. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 15.6% lost to follow‐up at 6m, "drop‐out rates did not vary significantly across study groups." Unclear if those lost to follow‐up counted as smokers. |

Lang 2000.

| Methods | Setting: Workplace Recruitment: smokers at annual check up (unselected) | |

| Participants | 1095 smokers (excludes losses to follow up due to company reorganization) 17% F, av cpd 14, >64% smoked >10 cpd | |

| Interventions | 1. Minimal advice; 5‐10 min from occupational physician. 2. Intensive intervention; contract with quit date, phone call 7 days post quit date, follow‐up visit | |

| Outcomes | Sustained abstinence (>= 6m) at 12m, assessed at annual check up. Validation: CO for a subsample. Unclear whether results reclassified | |

| Notes | Contributes data to intensive vs minimal comparison only. 28 physicians participated. Reported statistical analysis with physician as unit. Difference in 12m PP quit significant, not significant using sustained measure. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Cluster‐randomised by occupational physician, method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Before randomisation, each... physician sent the scientific committee a list of their working units...then, one unit per physician was randomly selected among his or her units.." Comment: Participant selection centralised. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 2 physicians declined to participate after being allocated to minimal intervention. Participants lost to follow‐up for work‐related reasons excluded from analysis, all other participants lost to follow‐up counted as smokers. |

Li 1984.

| Methods | Setting: Worksite (naval shipyard) in the USA. Recruitment: Smokers identified at worksite screening (unselected). | |

| Participants | 871 asbestos‐exposed smokers; mean cpd: 24‐26. Therapists: Occupational physicians. | |

| Interventions | 1. Minimal warning, results of pulmonary function tests, leaflet. 2. As group 1 plus behavioural counselling. Intervention level: Minimal (1), Intensive (2). Aids used: yes. Follow‐up visits: no. | |

| Outcomes | Sustained abstinence at 11m. Validation: expired CO. | |

| Notes | Contributes data to intensive vs minimal comparison only. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Randomly assigned," method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 292/871 participants lost to follow‐up, breakdown by group not provided (loss due in part to change in follow‐up procedure early in study). |

Marshall 1985.

| Methods | Setting: Six general practices on the Isle of Wight , UK. Recruitment: Patients responding to a postcard from the GP (selected). | |

| Participants | 200 adult smokers, mean cpd 22. 21% had a smoking‐related disease. Therapists: 11 general practitioners with no specific training. | |

| Interventions | 1. Advice plus nicotine gum. 2. As 1 plus offer of 4 follow‐up visits over 3m. Intervention level: Intensive (2) vs Minimal (1). Aids used: yes. Follow up: 4 in group 2. | |

| Outcomes | Sustained at 12m (from 6m). Validation: CO. | |

| Notes | Contributes data to intensive vs minimal comparison only. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Participants were assigned randomly to the two groups on receipt of their postcard. The only constraint placed on allocation was that married couples were assigned to the same group." Comment: randomisation done centrally by study investigator. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 7 participants lost to follow‐up, all in minimal intervention group. Participants lost to follow‐up counted as smokers. |

McDowell 1985.

| Methods | Setting: Family practices in Canada. Recruitment: Volunteers for smoking cessation programme (selected). | |

| Participants | 366 adult cigarette smokers in 9 group family practices (153 relevant to review); mean cpd 25. Therapists: 56 family physicians. | |

| Interventions | 1. Brief physician advice. 2. Health education in groups for 8 wks (not used in review). 3. Cognitive behaviour modification in 8 group sessions (not used in review). 4. Control: self‐monitoring of smoking. Intervention level: Minimal. Aids used: none. Follow‐up visits: no. | |

| Outcomes | PP abstinence at 12m. Validation: none performed, although subjects threatened with salivary thiocyanate measurement. | |

| Notes | In this review only groups 1 (intervention) and 4 (control) are considered. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Randomly assigned," method not stated. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not stated. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Differential drop‐out rates between groups. Participants missing outcome data at 6m excluded from final results (30). 6m data used for participants missing data at 12m who had provided at 6m (20 smokers). |

Meyer 2008.

| Methods | Setting: 34 general practices from a German region. Recruitment: smoking patients attending practices during 3 study wks (unselected). | |

| Participants | 1499 patients (1011 in relevant conditions) aged 18‐70 who reported daily cigarette smoking; 48% F, mean cpd 16. | |

| Interventions | 1. Control group (assessment only ‐ 22‐sided questionnaire administered in waiting room). 2. Computer‐generated tailored letters ‐ received 3 personalised letters tailored to the patient's stage of change and selected self‐help manuals (not included in meta‐analysis). 3. Brief advice from trained physician and selected self‐help manuals. Intervention level: Intensive. Aids used: yes. Follow‐up visits: no. | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 24m (sustained for 6m). Validation: none. | |

| Notes | 3 versus 1 contributes data to intensive versus control. Physicians trained between 2nd and 3rd study wks to avoid contamination of first two conditions. A stricter outcome reporting 6m abstinence at 12, 18 & 24m was also given. This gave a higher estimated effect with CIs that excluded 1. Advice compared to tailored letters in analysis 6.1, pooled with comparable arms in Meyer 2012. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "quasi‐randomisation based on the time of practice attendance." Fixed sequence of assessment‐only, tailored letters, advice. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | "Patients attending the practice frequently had a lower probability of inclusion in the later study groups." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Additional analysis using different assumptions about losses to follow‐up did not substantially alter any results. ITT analysis treating participants lost to follow‐up as smokers provided. |

Meyer 2012.

| Methods | Setting: 151 practices from a North‐German region. Recruitment: smoking patients attending practices. |

|

| Participants | 3215 patients (113 excluded) age 18+ years who reported any tobacco smoking within the last six months; 44% F, cpd not stated. | |

| Interventions | 1. Brief Advice: The physician intervention was designed to last 10 minutes and incorporated elements of “health behavior change counseling”. Stage of change‐specific self‐help manuals. 2. Tailored letters: individually tailored computer‐generated letters. Manuals as for 1. 3. Combination: both interventions. Intervention level: Intensive (but does not contribute to analysis). Aids: Self‐help manuals. |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12m, self‐reported as prolonged for previous 6m. 7‐day PP ('not even a puff') also reported. Validation: none. |

|

| Notes | Does not contribute to primary analysis since since no control comparable to other studies. Studies comparing intensive versus minimal intervention had physician participation in both activites. In this study the physician only gave smoking cessation advice in the consultation. The tailored letters did not require physician action. Advice compared to tailored letters in analysis 6.1, pooled with equivalent comparison from Meyer 2008. Patients who revisited the practice within the study period could receive up to 2 follow‐up interventions. 21.4% of those followed up received 1 follow‐up intervention, 10.6% received 2. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Cluster‐randomised. Practices randomly assigned prior to recruitment. More practices had to be contacted to recruit 50 in the brief advice (75 contacted) and combined (77 contacted) than the tailored letters group (65 contacted). No significant differences between practice characteristics. Authors note "randomisation was seriously undermined by obviously different mechanisms of patient selection for each study condition". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Practices not blind to condition when patients recruited. Fewer patients recruited in practices assigned to Brief Advice and Combination conditions. More practices in Combination group recruited no patients (23.5%) than Brief Advice (18%) or Tailored (14%). |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Uneven rate of drop‐out (30% Brief Advice group, 21% Tailored letters group, 29% Combination). Analysis 6.1 uses denominators from Table 2 which excludes ineligible participants recruited in error. "The analyses based on datasets including multiple imputed outcomes for patients lost to follow‐up revealed the same pattern of results found in the crude analyses." |

Morgan 1996.

| Methods | Setting: outpatient medical practices, USA. Recruitment: Practices volunteered, patients unselected by motivation. | |

| Participants | 659 smokers aged 50 ‐ 74. Therapists: Physicians with 45 ‐ 60 mins training. | |

| Interventions | 1. Physician advice, stage‐based, tailored self‐help guide. Follow‐up letter from physician and call from project staff. Smokers in contemplation given prescription and free 1 wk supply of gum. 2. Usual care (delayed intervention). Intervention level: intensive. Aids used: yes. Follow‐up visits: yes (phone call). | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 6m (assume PP). Validation: none. | |